Abstract

Cross-hypersensitivity to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is a relatively common, non-allergic, adverse drug event triggered by two or more chemically unrelated NSAIDs. Current evidence point to COX-1 inhibition as one of the main factors in its etiopathogenesis. Evidence also suggests that the risk is dose-dependent. Therefore it could be speculated that individuals with impaired NSAID biodisposition might be at increased risk of developing cross-hypersensitivity to NSAIDs. We analyzed common functional gene variants for CYP2C8, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19 in a large cohort composed of 499 patients with cross-hypersensitivity to NSAIDs and 624 healthy individuals who tolerated NSAIDs. Patients were analyzed as a whole group and subdivided in three groups according to the main enzymes involved in the metabolism of the culprit drugs as follows: CYP2C9, aceclofenac, indomethacin, naproxen, piroxicam, meloxicam, lornoxicam, and celecoxib; CYP2C8 plus CYP2C9, ibuprofen and diclofenac; CYP2C19 plus CYP2C9, metamizole. Genotype calls ranged from 94 to 99%. No statistically significant differences between patients and controls were identified in this study, either for allele frequencies, diplotypes, or inferred phenotypes. After patient stratification according to the enzymes involved in the metabolism of the culprit drugs, or according to the clinical presentation of the hypersensitivity reaction, we identified weak significant associations of a lower frequency (as compared to that of control subjects) of CYP2C8*3/*3 genotypes in patients receiving NSAIDs that are predominantly CYP2C9 substrates, and in patients with NSAIDs-exacerbated cutaneous disease. However, these associations lost significance after False Discovery Rate correction for multiple comparisons. Taking together these findings and the statistical power of this cohort, we conclude that there is no evidence of a major implication of the major functional CYP2C polymorphisms analyzed in this study and the risk of developing cross-hypersensitivity to NSAIDs. This argues against the hypothesis of a dose-dependent COX-1 inhibition as the main underlying mechanism for this adverse drug event and suggests that pre-emptive genotyping aiming at drug selection should have a low practical utility for cross-hypersensitivity to NSAIDs.

Keywords: CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, NSAID, polymorphisms, hypersensitivity

Introduction

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the most common drugs used to relieve pain and to decrease inflammation and fever. NSAIDs are among the most used drugs in the world, and they comprise a wide range of chemically unrelated compounds. It is estimated that over 30 million people worldwide use these medications daily, not only as prescription drugs but also over-the-counter (OTC) (Singh, 2000). As a general rule, prescription NSAIDs are effective to relieve chronic musculoskeletal pain and inflammation, and OTC NSAIDs, normally at lower doses, are effective to relieve acute or minor aches and pains. These drugs are quite safe, but despite being available OTC in many countries, they could bring about adverse drug reactions (ADRs).

ADRs have been reported in approximately 1.5% of the patients with at least one NSAIDs prescribed and around 23.3% of the adverse drug reactions to NSAIDs are due to hypersensitivity reactions (Blumenthal et al., 2016, 2017). One specific type of ADRs, hypersensitivity drug reactions (HDRs) can be divided into two main groups: on one side those which are initiated by specific immunological mechanisms (also described as drug allergy), the response is induced by a single drug, and patients are classified as selective drug responders. These reactions can be IgE-mediated, designated as immediate drug allergy, or T cell-mediated, designated as delayed drug allergy. On the other side, HDRs whose mechanisms are nonimmunological (also described as nonallergic hypersensitivity), the reaction is induced by two or more chemically unrelated drugs, and patients are classified as cross-intolerant or cross-hypersensitivity subjects (Johansson et al., 2004; Szczeklik et al., 2009; Doña et al., 2011).

According to their clinical presentation, cross-hypersensitivity reactions could be classified as NSAIDs-exacerbated respiratory disease (NERD), NSAIDs-exacerbated cutaneous disease (NECD), and NSAID-induced urticaria/angioedema (NIUA) (Kowalski et al., 2013). These non-immunological reactions are believed to be originated via inhibition of cyclooxygenase 1 (COX-1) enzyme and the release of histamine and sulphidopeptide leukotrienes (Kowalski et al., 2007; Doña et al., 2018; Bakhriansyah et al., 2019; Li and Laidlaw, 2019; Mastalerz et al., 2019). In this context, it is important to bear in mind that NSAIDs antagonize inflammation by interfering with the function of cyclooxygenases, and therefore their association with nonallergic hypersensitivity might be related to disequilibrium in the arachidonic acid degradation pathways, that is, interference with the formation of prostaglandins and thromboxanes, thus resulting in the shunting of arachidonic acid metabolism towards the 5-lipoxygenase pathway, and the consequent increase in the release of cysteinyl leukotrienes (Sánchez-Borges, 2010; Caimmi et al., 2012).

Interindividual variability in drug metabolism is likely to be involved in HDRs (Agúndez et al., 2015a, Agúndez et al., 2018; García-Martín et al., 2015; Ariza et al., 2016; Sánchez-Gómez et al., 2016; Plaza-Serón et al., 2018). A substantial part of such interindividual variability is associated with polymorphisms in genes coding drug-metabolizing enzymes. NSAIDs are extensively metabolized by Cytochrome P450 2C enzymes (CYP2C) and CYP2C gene variants are strongly related to the pharmacokinetics, pharmacological effects, and adverse drug reactions for many NSAIDs (Agúndez JA. et al., 2009; Agúndez et al., 2009 J.; Agúndez et al., 2011; Szczeklik et al., 2009; Martínez et al., 2014; Macías et al., 2020; Theken et al., 2020). Impaired CYP2C metabolism brings about decreased clearance, increased drug exposure, and therefore, increased COX-inhibition. Since cross-hypersensitivity induced by NSAIDs is believed to be related to COX-inhibition, it is conceivable that individuals with genetic alterations leading to impairment in NSAID metabolism would be more prone to developing cross-hypersensitivity induced by these drugs. However, no studies have been conducted to test such a hypothesis. We analyzed such putative association in a large study group with enough sample size to support or discard a major association between common CYP2C functional gene variants and the risk of developing cross-hypersensitivity with NSAIDs metabolized by these enzymes.

Methods

Participants

A total cohort of 1.123 participants was analyzed in this study, all were Spanish individuals with South European Ancestry. Ancestry was self-reported. Four hundred and ninety-nine patients who developed hypersensitivity to acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) and one or more chemically different NSAIDs mainly metabolized by CYP2C enzymes were included in the study. Their mean age was 42 (SD = 17.46) years. Also, six hundred and twenty-four healthy individuals with an average age of 21 (SD = 2.32) years participated as control subjects. All control individuals tolerated NSAIDs that are CYP2C substrates. Patients and controls were recruited between 2007 and 2020 from the Allergy Services of the following hospitals in Spain: Badajoz University Hospital, Málaga University Hospital, Madrid Cruz Roja Hospital, Barcelona Clinic Hospital, Madrid Infanta Leonor Hospital, Alcorcón University Hospital, and Elche University Hospital. Control individuals were selected among the staff and students assessed through anamnesis, clinical history and/or self-reported tolerance to COX-1 inhibitors. Inclusion criteria for the patients were as follows: Diagnosis of cross-hypersensitivity (Pérez-Alzate et al., 2017; Blanca-López et al., 2018, Blanca-López et al., 2019) by clinical history and a positive drug provocation test, for one or more of the following NSAIDs: ibuprofen, diclofenac, aceclofenac, indomethacin, naproxen, piroxicam, meloxicam, lornoxicam, celecoxib, and metamizole. ASA-positivity was included as a requisite in the diagnosis because in cross-reactive (non-allergic) hypersensitivity patients react to all strong COX-1 inhibitors, including ASA, whereas allergic hypersensitivity patients tolerate ASA (Kowalski et al., 2013; Pérez-Alzate et al., 2017; Angeletti et al., 2020); besides, CYP2C9 plays a role in ASA metabolism (Thiessen, 1983; Hutt et al., 1986; Bigler et al., 2001; Palikhe et al., 2011; Gómez-Tabales et al., 2020). Patients who presented with hypersensitivity triggered by other NSAIDs whose metabolism is not mainly catalyzed by CYP2C enzymes (including clonixinate, dexketoprofen, ketorolac, etofenamate, ketoprofen, piketoprofen, propifenazone, phenylbutazone, aminophenazone, acetaminophen, etoricoxib and oxyphenbutazone) were excluded from the study. The study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committees of each participating hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants involved in the study.

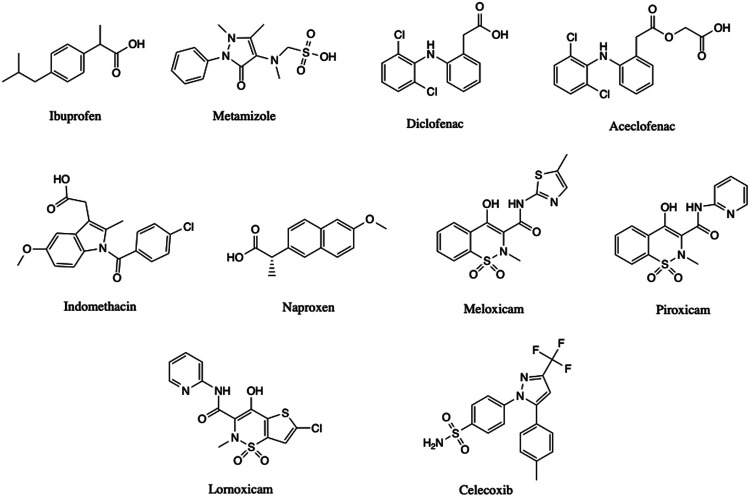

The main NSAIDs (Figure 1) that triggered the hypersensitivity reaction are shown in Table 1. The clinical presentations stratified according to the culprit drugs involved are summarized in Table 2.

FIGURE 1.

Drug structures.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the individuals and drug involved in NSAID-induced cross-hypersensitivity in this study.

| Total N | Men N (%) | Women N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | 624 (55.57) | 225 (51.84) | 399 (57.91) |

| Patients | 499 (44.43) | 209 (48.16) | 290 (42.09) |

| Culprit drug | Total N (%) | Men N (%) | Women N (%) |

| Ibuprofen | 353 (45.43) | 145 (45.03) | 208 (45.71) |

| Metamizole | 246 (31.66) | 104 (32.30) | 142 (31.21) |

| Diclofenac | 108 (13.90) | 45 (13.98) | 63 (13.85) |

| Naproxen | 36 (4.63) | 15 (4.66) | 21 (4.62) |

| Aceclofenac | 12 (1.54) | 5 (1.55) | 7 (1.54) |

| Piroxicam | 11 (1.42) | 3 (0.93) | 8 (1.76) |

| Indomethacin | 5 (0.64) | 3 (0.93) | 2 (0.44) |

| Meloxicam | 3 (0.39) | 1 (0.31) | 2 (0.44) |

| Lornoxicam | 2 (0.26) | 0 | 2 (0.44) |

| Celecoxib | 1 (0.13) | 1 (0.31) | 0 |

| Totala | 777 (100) | 322 (100) | 455 (100) |

The total number exceeds the number of patients because many of them presented cross hypersensitivity to two or more drugs.

TABLE 2.

Gender and clinical presentation of NSAID-induced cross-hypersensitivity in this study.

| Gender | NECD N (%) | NERD N (%) | Mixed pattern N (%) | Anaphylaxis N (%) | NIUA N (%) | Unknown N (%) | Total N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 144 (42.48) | 22 (37.93) | 22 (36.67) | 17 (50.00) | 1 (50.00) | 3 (50.00) | 209 |

| Women | 195 (57.52) | 36 (62.07) | 38 (63.33) | 17 (50.00) | 1 (50.00) | 3 (50.00) | 290 |

| Culprit drug | NECD N (%) | NERD N (%) | Mixed pattern N (%) | Anaphylaxis N (%) | NIUA N (%) | Unknown N (%) | Total N (%) |

| Ibuprofen | 254 (46.95) | 36 (42.35) | 42 (48.28) | 19 (34.55) | 2 (66.67) | 2 (33.33) | 355 |

| Metamizole | 165 (30.50) | 33 (38.82) | 23 (26.44) | 22 (40.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (16.67) | 244 |

| Diclofenac | 73 (13.49) | 8 (9.41) | 15 (17.24) | 9 (16.36) | 1 (33.33) | 2 (33.33) | 108 |

| Aceclofenac | 11 (2.03) | 1 (1.18) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 12 |

| Indomethacin | 2 (0.37) | 2 (2.35) | 1 (1.15) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 5 |

| Naproxen | 24 (4.44) | 4 (4.71) | 3 (3.45) | 5 (9.09) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 36 |

| Meloxicam | 2 (0.37) | 1 (1.18) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 3 |

| Piroxicam | 9 (1.66) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.15) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (16.67) | 11 |

| Lornoxicam | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (2.30) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 2 |

| Celecoxib | 1 (0.18) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 |

| Totala | 541 (100) | 85 (100) | 87 (100) | 55 (100) | 3 (100) | 6 (100) |

The total number exceeds the number of patients because many of them presented cross hypersensitivity to two or more drugs.

Genotyping Study

Genomic DNA was obtained and purified by following standard procedures and then genotypic analyses were performed using a real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). The target SNVs were selected according to their functional effect or clinical implications, as well as the signature allele frequencies in the population studied. The analyses focused on the signature SNVs for Tier 1 variant alleles according to the PharmVar database (https://www.pharmvar.org/). For CYP2C9, Tier 1 alleles are CYP2C9*2, *3, *5, *6, *8, and *11 (Pratt et al., 2019). Among these, the alleles CYP2C9*5, *6, *8, and *11 were not included in the analyses because their signature SNVs had extremely low frequencies (ranging from 0.00002 to 0.003) in European individuals according to public databases (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org). Therefore, we analyzed CYP2C9*2 (rs1799853) and CYP2C9*3 (rs1057910). Regarding CYP2C19, Tier 1 alleles are the CYP2C19 alleles *2 (rs12769205), *3 (rs4986893) and *17 (rs12248560) (Botton et al., 2020; Pratt et al., 2018). CYP2C19*3 allele was excluded from the study because its signature SNV has a very low allele frequency (equal to 0.0003) in European individuals (Botton et al., 2020). Although no Tier 1 variants have been defined for CYP2C8, we used the same criteria as reported elsewhere (Pratt et al., 2018, Pratt et al., 2019), based on their reported clinical relevance, CYP2C8-associated medications, and their frequency. We selected the variant alleles CYP2C8*3 (rs11572080) and *4 (rs1058930). CYP2C8*2 (rs11572103) was not included because its signature SNV has a very low frequency among Europeans (0.003). All SNVs were tested by using TaqMan Assays (Life Sciences, Alcobendas, Madrid, Spain) pre-designed to detect the above-mentioned SNVs. Details of the TaqMan probes and minor allele frequencies in the study population are shown in Table 3. Assignment of predicted phenotype based on genotype was carried out as described elsewhere for CYP2C9 (Theken et al., 2020), and CYP2C19 (Lima et al., 2020). For CYP2C8, predicted phenotype was carried out assuming that both, CYP2C8*3 and CYP2C8*4 alleles, lead to decreased metabolic activity (Bahadur et al., 2002).

TABLE 3.

SNVs analyzed in this study.

| Allele | dbSNP | Chromosomal location | Minor allele frequency (control subjects) | Statistical power (one tailed/two tailed; OR = 1.5, α = 0.0083) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2C8*3 | rs11572080 C/T | 10:96827030 | 0.1615 | 89.02/83.74 |

| CYP2C8*4 | rs1058930 G/C | 10:96818119 | 0.0611 | 50.65/41.03a (1) |

| CYP2C9*2 | rs1799853 C/T | 10:96702047 | 0.1558 | 88.09/82.53 |

| CYP2C9*3 | rs1057910 A/C | 10:96741053 | 0.0701 | 56.73/47.07a (2) |

| CYP2C19*2 | rs12769205 A/G | 10:96535124 | 0.1424 | 85.52/79.26 |

| CYP2C19*17 | rs12248560 C/T | 10:96521657 | 0.2104 | 94.27/90.88 |

The statistical power (one tailed/two tailed, OR = 1.8, α = 0.0083) is: (1) 88.85%/83.54%; (2) 92.59%/88.54%.

Statistical Analyses

The R package SNPassoc (González et al., 2014) was used to calculate allele and genotypic frequencies, to determine the Hardy-Weinberg’s equilibrium (HWE) using the exact test as described elsewhere (Wigginton et al., 2005) and to analyze differences between groups (González et al., 2007).

The comparison of the frequencies of each SNV between traits was performed by using binary logistic regression, assuming different genetic models. To evaluate the genotype risks we applied a traditional logistic regression establishing the most frequent level (*1/*1) as the baseline. The model also includes sex as a predictor and offers two different adjusted p-values from the likelihood ratio test (LRT). The specific p-value measures the significance of the risk of a particular level with respect to the *1/*1 diplotype while the global p-value measures whether the inclusion of all diplotypes different to *1/*1 as a predictor brings about significant additional information about the trait.

When assessing allele risks, the additive model (each copy of the minor allele modifies the risk in an additive form) was used. The analysis was carried out generating a numeric feature with value 0 for the baseline (wild type), 1 for heterozygous for defect alleles, and 2 for homozygous. The additive model was also applied to measure the risk of inferred phenotypes. For CYP2C8 and CYP2C9 the baseline level is RM, while for CYP2C19 we have established NM as baseline level, IM as intermediate high risk level, PM as higher risk level, RM as intermediate low risk level and UR as lower risk level.

The p-values (Tables 4, 5) were adjusted by gender and were obtained by likelihood ratio test (LRT), comparing the likelihood of the nested model that only includes gender as predictor, with the least restrictive model that includes gender and alleles or inferred genotype as predictor.

TABLE 4.

Alleles, genotypes and inferred phenotypes observed in overall patients and healthy controls.

| Alleles | Patients (No) | Patients (%) | Controls (No) | Controls (%) | OR (adjusted): Wald | Intergroup comparison values. p-value (adjusted): LRT global |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2C8*3 C/C | 350 | 71.87% | 434 | 71.15% | 0.9 (0.71–1.14) | 0.372 |

| CYP2C8*3 C/T | 130 | 26.69% | 155 | 25.41% | ||

| CYP2C8*3 T/T | 7 | 1.44% | 21 | 3.44% | ||

| Total | 487 | 610 | ||||

| CYP2C8*4 G/G | 433 | 89.83% | 520 | 88.29% | 0.85 (0.59–1.22) | 0.378 |

| CYP2C8*4 C/G | 47 | 9.75% | 66 | 11.21% | ||

| CYP2C8*4 C/C | 2 | 0.41% | 3 | 0.51% | ||

| Total | 482 | 589 | ||||

| CYP2C9*2 C/C | 365 | 73.89% | 441 | 71.94% | 0.88 (0.7–1.12) | 0.293 |

| CYP2C9*2 C/T | 120 | 24.29% | 153 | 24.96% | ||

| CYP2C9*2 T/T | 9 | 1.82% | 19 | 3.10% | ||

| Total | 494 | 613 | ||||

| CYP2C9*3 A/A | 410 | 87.23% | 513 | 86.66% | 0.96 (0.69–1.34) | 0.812 |

| CYP2C9*3 A/C | 57 | 12.13% | 75 | 12.67% | ||

| CYP2C9*3 C/C | 3 | 0.64% | 4 | 0.68% | ||

| Total | 470 | 592 | ||||

| CYP2C19*2 A/A | 367 | 73.84% | 449 | 72.65% | 1.00 (0.78–1.28) | 0.995 |

| CYP2C19*2 A/G | 119 | 23.94% | 162 | 26.21% | ||

| CYP2C19*2 G/G | 11 | 2.21% | 7 | 1.13% | ||

| Total | 497 | 618 | ||||

| CYP2C19*17 C/C | 312 | 65.00% | 376 | 62.77% | 0.93 (0.75–1.14) | 0.483 |

| CYP2C19*17 C/T | 146 | 30.42% | 194 | 32.39% | ||

| CYP2C19*17 T/T | 22 | 4.58% | 29 | 4.84% | ||

| TOTAL | 480 | 599 |

| Genotypes | Patients (No) | Patients (%) | Controls (No) | Controls (%) | OR (adjusted) | Intergroup comparison values. p-value (adjusted): LRT global |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2C8*1/*1 | 304 | 64.27% | 351 | 60.52% | — | 0.152 |

| CYP2C8*1/*3 | 115 | 24.31% | 140 | 24.14% | 0.95 (0.71–1.27) | |

| CYP2C8*1/*4 | 34 | 7.19% | 55 | 9.48% | 0.71 (0.45–1.12) | |

| CYP2C8*3/*3 | 7 | 1.48% | 21 | 3.62% | 0.37 (0.15–0.88) | |

| CYP2C8*3/*4 | 11 | 2.33% | 10 | 1.72% | 1.27 (0.53–3.05) | |

| CYP2C8*4/*4 | 2 | 0.42% | 3 | 0.52% | 0.72 (0.12–4.35) | |

| Total | 473 | 580 | ||||

| CYP2C9*1/*1 | 301 | 64.45% | 354 | 60.10% | — | 0.550 |

| CYP2C9*1/*2 | 100 | 21.41% | 137 | 23.26% | 0.85 (0.63–1.15) | |

| CYP2C9*1/*3 | 47 | 10.06% | 62 | 10.53% | 0.92 (0.6–1.36) | |

| CYP2C9*2/*2 | 8 | 1.71% | 19 | 3.23% | 0.5 (0.21–1.15) | |

| CYP2C9*2/*3 | 8 | 1.71% | 13 | 2.21% | 0.73 (0.3–1.79) | |

| CYP2C9*3/*3 | 3 | 0.64% | 4 | 0.68% | 0.81 (0.18–3.68) | |

| Total | 467 | 589 | ||||

| CYP2C19*1/*1 | 211 | 44.05% | 248 | 41.61% | — | 0.463 |

| CYP2C19*1/*2 | 92 | 19.21% | 120 | 20.13% | 0.89 (0.64–1.24) | |

| CYP2C19*1/*17 | 118 | 24.63% | 155 | 26.01% | 0.9 (0.66–1.21) | |

| CYP2C19*2/*2 | 11 | 2.30% | 6 | 1.01% | 2.3 (0.83–6.34) | |

| CYP2C19*2/*17 | 26 | 5.43% | 40 | 6.71% | 0.77 (0.45–1.31) | |

| CYP2C19*17/*17 | 21 | 4.38% | 27 | 4.53% | 0.89 (0.49–1.63) | |

| Total | 479 | 596 | ||||

| Inferred Phenotypes | Patients (No) | Patients (%) | Controls (No) | Controls (%) | OR (adjusted) | Intergroup comparison values. p-value (adjusted): LRT global |

| CYP2C8 RM | 304 | 64.27% | 351 | 60.52% | 0.85 (0.69–1.05) | 0.126 |

| CYP2C8 IM | 149 | 31.50% | 195 | 33.62% | ||

| CYP2C8 PM | 20 | 4.23% | 34 | 5.86% | ||

| Total | 473 | 580 | ||||

| CYP2C9 RM | 301 | 64.45% | 354 | 60.10% | 0.85 (0.67–1.06) | 0.144 |

| CYP2C9 IM | 155 | 33.19% | 218 | 37.01% | ||

| CYP2C9 PM | 11 | 2.36% | 17 | 2.89% | ||

| Total | 467 | 589 | ||||

| CYP2C19 UR | 21 | 4.38% | 27 | 4.53% | 1.03 (0.9–1.19) | 0.664 |

| CYP2C19 RM | 118 | 24.63% | 155 | 26.01% | ||

| CYP2C19 NM | 211 | 44.05% | 248 | 41.61% | ||

| CYP2C19 IM | 118 | 24.63% | 160 | 26.85% | ||

| CYP2C19 PM | 11 | 2.30% | 6 | 1.01% | ||

| Total | 479 | 596 |

IM, intermediate metabolizer; LTR, likelihood ratio test; NM, normal metabolizer; No, number; OR, odds ratio; PM, poor metabolizer; RM, rapid metabolizer; UR = ultrarapid metabolizer.

TABLE 5.

Alleles, genotypes and inferred phenotypes observed in the three subgroups of patients.

| Alleles | Patients group 1 (No) | Patients (%) | OR (adjusted) | Intergroup comparison values. p-value (adjusted): LRT global | Patients group 2 (No) | Patients (%) | OR (adjusted) | Intergroup comparison values. p-value (adjusted): LRT global | Patients group 3 (No) | Patients (%) | OR (adjusted) | Intergroup comparison values. p-value (adjusted): LRT global |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2C8*3 C/C | 48 | 71.64% | 0.86 (0.52–1.42) | 0.546 | 277 | 72.32% | 0.89 (0.69–1.14) | 0.353 | 171 | 71.55% | 0.9 (0.67–1.21) | 0.488 |

| CYP2C8*3 C/T | 19 | 28.36% | 100 | 26.11% | 65 | 27.20% | ||||||

| CYP2C8*3 T/T | 0 | 0.00% | 6 | 1.57% | 3 | 1.26% | ||||||

| Total | 67 | 383 | 239 | |||||||||

| CYP2C8*4 G/G | 61 | 89.71% | 0.82 (0.37–1.81) | 0.616 | 341 | 89.50% | 0.89 (0.6–1.31) | 0.550 | 215 | 90.72% | 0.76 (0.47–1.23) | 0.259 |

| CYP2C8*4 C/G | 7 | 10.29% | 38 | 9.97% | 21 | 8.86% | ||||||

| CYP2C8*4 C/C | 0 | 0.00% | 2 | 0.52% | 1 | 0.42% | ||||||

| Total | 68 | 381 | 237 | |||||||||

| CYP2C9*2 C/C | 47 | 70.15% | 0.95 (0.58–1.56) | 0.845 | 288 | 73.85% | 0.88 (0.69–1.14) | 0.332 | 179 | 73.97% | 0.90 (0.68–1.21) | 0.496 |

| CYP2C9*2 C/T | 20 | 29.85% | 95 | 24.36% | 57 | 23.55% | ||||||

| CYP2C9*2 T/T | 0 | 0.00% | 7 | 1.79% | 6 | 2.48% | ||||||

| Total | 67 | 390 | 242 | |||||||||

| CYP2C9*3 A/A | 54 | 83.08% | 1.24 (0.65–2.38) | 0.526 | 322 | 87.03% | 0.97 (0.68–1.39) | 0.875 | 199 | 86.90% | 0.98 (0.64–1.5) | 0.925 |

| CYP2C9*3 A/C | 11 | 16.92% | 46 | 12.43% | 29 | 12.66% | ||||||

| CYP2C9*3 C/C | 0 | 0.00% | 2 | 0.54% | 1 | 0.44% | ||||||

| Total | 65 | 370 | 229 | |||||||||

| CYP2C19*2 A/A | 47 | 70.15% | 1.2 (0.73–1.99) | 0.479 | 293 | 74.74% | 0.96 (0.74–1.25) | 0.783 | 181 | 73.88% | 1.01 (0.74–1.37) | 0.952 |

| CYP2C19*2 A/G | 18 | 26.87% | 90 | 22.96% | 58 | 23.67% | ||||||

| CYP2C19*2 G/G | 2 | 2.99% | 9 | 2.30% | 6 | 2.45% | ||||||

| Total | 67 | 392 | 245 | |||||||||

| CYP2C19*17 C/C | 40 | 59.70% | 1.12 (0.73–1.7) | 0.610 | 254 | 67.20% | 0.87 (0.69–1.09) | 0.216 | 152 | 64.41% | 0.93 (0.71–1.21) | 0.585 |

| CYP2C19*17 C/T | 23 | 34.33% | 107 | 28.31% | 74 | 31.36% | ||||||

| CYP2C19*17 T/T | 4 | 5.97% | 17 | 4.50% | 10 | 4.24% | ||||||

| 67 | 378 | 236 | ||||||||||

| Genotypes | Patients Group 1 (No) | Patients (%) | OR (adjusted) | Intergroup comparison values. p-value (adjusted): LRT global | Patients Group 2 (No) | Patients (%) | OR (adjusted) | Intergroup comparison values. p-value (adjusted): LRT global | Patients Group 3 (No) | Patients (%) | OR (adjusted) | Intergroup comparison values. p-value (adjusted): LRT global |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2C8*1/*1 | 45 | 67.16% | — | 0.043 | 240 | 64.34% | — | 0.277 | 148 | 64.63% | — | 0.372 |

| CYP2C8*1/*3 | 15 | 22.39% | 0.84 (0.45–1.56) | 89 | 23.86% | 0.93 (0.68–1.27) | 56 | 24.45% | 1.00 (0.69–1.43) | |||

| CYP2C8*1/*4 | 3 | 4.48% | 0.42 (0.13–1.39) | 27 | 7.24% | 0.71 (0.44–1.17) | 18 | 7.86% | 0.75 (0.42–1.32) | |||

| CYP2C8*3/*3 | 0 (0-inf) | 6 | 1.61% | 0.4 (0.16–1.01) | 3 | 1.31% | 0.32 (0.09–1.1) | |||||

| CYP2C8*3/*4 | 4 | 5.97% | 3.01 (0.9–10.03) | 9 | 2.41% | 1.32 (0.53–3.3) | 3 | 1.31% | 0.69 (0.19–2.54) | |||

| CYP2C8*4/*4 | 0 (0-inf) | 2 | 0.54% | 0.92 (0.15–5.59) | 1 | 0.44% | 0.75 (0.08–7.35) | |||||

| Total | 67 | 373 | 232 | |||||||||

| CYP2C9*1/*1 | 35 | 54.69% | — | 0.261 | 236 | 64.13% | — | 0.528 | 147 | 65.33% | — | 0.843 |

| CYP2C9*1/*2 | 18 | 28.13% | 1.33 (0.73–2.43) | 80 | 21.74% | 0.87 (0.63–1.2) | 43 | 19.11% | 0.82 (0.56–1.21) | |||

| CYP2C9*1/*3 | 9 | 14.06% | 1.5 (0.68–3.27) | 39 | 10.60% | 0.96 (0.62–1.48) | 24 | 10.67% | 0.91 (0.55–1.53) | |||

| CYP2C9*2/*2 | 0 | 0.00% | 0 (0-inf) | 6 | 1.63% | 0.47 (0.19–1.2) | 4 | 1.78% | 0.63 (0.23–1.73) | |||

| CYP2C9*2/*3 | 2 | 3.13% | 1.59 (0.34–7.32) | 5 | 1.36% | 0.59 (0.21–1.69) | 7 | 3.11% | 1.13 (0.42–3.04) | |||

| CYP2C9*3/*3 | 0 | 0.00% | 0 (0-inf) | 2 | 0.54% | 0.71 (0.13–3.92) | 0 | 0.00% | 0.57 (0.06–5.15) | |||

| Total | 64 | 368 | 229 | |||||||||

| CYP2C19*1/*1 | 24 | 36.36% | — | 0.808 | 178 | 47.21% | — | 0.217 | 99 | 41.95% | — | 0.378 |

| CYP2C19*1/*2 | 14 | 21.21% | 1.19 (0.59–2.39) | 69 | 18.30% | 0.8 (0.56–1.13) | 49 | 20.76% | 1.02 (0.68–1.53) | |||

| CYP2C19*1/*17 | 19 | 28.79% | 1.26 (0.67–2.38) | 85 | 22.55% | 0.77 (0.55–1.07) | 63 | 26.69% | 1.01 (0.69–1.47) | |||

| CYP2C19*2/*2 | 2 | 3.03% | 3.71 (0.7–19.57) | 9 | 2.39% | 2.22 (0.77–6.36) | 6 | 2.54% | 2.61 (0.82–8.32) | |||

| CYP2C19*2/*17 | 4 | 6.06% | 1.03 (0.34–3.14) | 20 | 5.31% | 0.7 (0.4–1.24) | 9 | 3.81% | 0.58 (0.27–1.22) | |||

| CYP2C19*17/*17 | 3 | 4.55% | 1.08 (0.3–3.85) | 16 | 4.24% | 0.81 (0.42–1.56) | 10 | 4.24% | 0.9 (0.42–1.93) | |||

| Total | 66 | 377 | 236 | |||||||||

| Inferred Phenotypes | Patients Group 1 (No) | Patients (%) | OR (adjusted) | Intergroup comparison values. p-value (adjusted): LRT global | Patients Group 2 (No) | Patients (%) | OR (adjusted) | Intergroup comparison values. p-value (adjusted): LRT global | Patients Group 3 (No) | Patients (%) | OR (adjusted) | Intergroup comparison values. p-value (adjusted): LRT global |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2C8 RM | 45 | 67.16% | 0.82 (0.53–1.27) | 0.372 | 241 | 64.44% | 0.86 (0.69–1.07) | 0.177 | 148 | 64.63% | 0.82 (0.63–1.07) | 0.144 |

| CYP2C8 IM | 18 | 26.87% | 116 | 31.02% | 74 | 32.31% | ||||||

| CYP2C8 PM | 4 | 5.97% | 17 | 4.55% | 7 | 3.06% | ||||||

| Total | 67 | 373 | 232 | |||||||||

| CYP2C9 RM | 35 | 54.69% | 1.2 (0.76–1.9) | 0.429 | 236 | 64.84% | 0.84 (0.66–1.08) | 0.167 | 147 | 65.33% | 0.88 (0.66–1.17) | 0.372 |

| CYP2C9 IM | 27 | 42.19% | 123 | 33.79% | 72 | 32.00% | ||||||

| CYP2C9 PM | 2 | 3.13% | 5 | 1.37% | 6 | 2.67% | ||||||

| Total | 64 | 368 | 229 | |||||||||

| CYP2C19 UR | 3 | 4.55% | 1.03 (0.77–1.38} | 0.843 | 16 | 4.24% | 1.05 (0.9–1.22) | 0.517 | 10 | 4.24% | 1.02 (0.85–1.21) | 0.857 |

| CYP2C19 RM | 19 | 28.79% | 85 | 22.55% | 63 | 26.69% | ||||||

| CYP2C19 NM | 24 | 36.36% | 178 | 47.21% | 99 | 41.95% | ||||||

| CYP2C19 IM | 18 | 27.27% | 89 | 23.61% | 58 | 24.58% | ||||||

| CYP2C19 PM | 2 | 3.03% | 9 | 2.39% | 6 | 2.54% | ||||||

| Total | 66 | 377 | 236 |

IM, intermediate metabolizer; LTR, likelihood ratio test; NM, normal metabolizer; No, number; OR, odds ratio; PM, poor metabolizer; RM, rapid metabolizer; UR = ultrarapid metabolizer.

The results were considered statistically significant when p-values were equal or under 0.05. Also, the odds ratio (OR) of Wald Test associated was estimated with a 95% confidence interval (CI). False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction was used for multiple comparison adjustments (Benjamini et al., 2001).

The statistical power for the sample size of this study was calculated to analyze the minor allele frequency (MAF) with a genetic model with an odds ratio value = 1.5 determined from the allele frequencies observed in healthy subjects in previous studies carried out in Spaniards (García-Martín et al., 2001, García-Martín et al., 2004, García-Martín et al., 2015; Alonso-Navarro et al., 2006; Blanco et al., 2008; Ladero et al., 2012; Martínez et al., 2014). The Bonferroni correction was used to make an adjustment for multiple comparisons: the significance level of 0.05 was reduced (α = 0.0083) according to the number of comparisons made (6 in this study). The statistical power for all cases and each SNV analyzed is detailed in Table 3. For most SNVs the statistical power was high enough to detect an OR = 1.5 with a bilateral power higher than 80%. For two SNVs (rs1058930 and rs1057910), because of the low MAF observed in this study, the statistical power was not sufficient to detect an OR = 1.5, but it was sufficient to detect an OR = 1.8 (Table 3).

Results

The most common drugs involved for cross-reactive hypersensitivity induced by NSAIDs were ibuprofen, metamizole and diclofenac (Table 1), and the most frequent clinical presentation was NECD (Table 2). Since many patients experienced cross-reactive hypersensitivity with more than one drug, the sum of the patients in each subgroup in these Tables exceeds the total number of patients. The clinical presentation was strongly related to the drug involved. NECD was particularly related to ibuprofen, whereas anaphylaxis was mainly related to metamizole (Table 2).

To determine the influence of genetic polymorphisms in the risk of developing cross-reactive hypersensitivity, genotypes, diplotypes, and inferred phenotypes were compared in overall patients and healthy controls (Table 4). Genotype calls were very high for all SNVs as follows: CYP2C8*3: 97.6% patients and 97.8% controls; CYP2C8*4: 96.6% patients and 94.4% controls; CYP2C9*2: 99.0% patients and 98.2% controls; CYP2C9*3: 94.2% patients and 94.9% controls; CYP2C19*2: 99.6% patients and 99.0% controls; and CYP2C19*17: 96.2% patients and 96.0% controls. All SNVs were at Hardy-Weinberg’s equilibrium in patients and control individuals and the allele frequencies correspond with those previously described in Spaniards (Martínez et al., 2001; García-Martín et al., 2006; Blanco et al., 2008; Martínez et al., 2014; García-Martín et al., 2015), as well as those reported in public databases (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org). For individuals who were successfully genotyped for all relevant SNVs in each gene, inferred phenotypes were calculated from diplotypes as described under Methods. The percentage of individuals with inferred phenotypes were as follows: CYP2C8: 95.0% patients and 92.9% controls; CYP2C9: 93.2% patients and 94.4% controls; and CYP2C19: 95.8% patients and 95.5% controls. No statistically significant differences either in allele frequencies, genotypes, or inferred phenotypes were observed when comparing patients with control individuals (Table 4), thus suggesting that CYP2C-related impaired NSAID metabolism is not strongly related to the risk of developing cross-hypersensitivity to NSAIDs.

Since the role of CYP2C enzymes in the metabolism of NSAIDs vary depending on the substrate, patients were divided into three subgroups according to the main enzymes involved in the metabolism of the culprit drugs: group 1: drugs mainly metabolized by CYP2C9 (aceclofenac, indomethacin, naproxen, piroxicam, meloxicam, lornoxicam, and celecoxib); group 2: drugs mainly metabolized by CYP2C8 and CYP2C9 (ibuprofen and diclofenac); and group 3: drugs mainly metabolized by CYP2C19 and CYP2C9 (metamizole) (Leemann et al., 1993; Bonnabry et al., 1996; Miners et al., 1996; Türck et al., 1996; Hamman et al., 1997; Chesné et al., 1998; FDA (Food and Drug Administration), 1998; Skjodt and Davies, 1998; Bort et al., 1999; Davies and Skjodt, 1999; Davies et al., 2000; Henrotin et al., 2001; Tang et al., 2001; Martínez et al., 2005; Perini et al., 2005; Tornio et al., 2007; Chang et al., 2008; Agúndez JA. et al., 2009; Byrav et al., 2009; Neunzig et al., 2012; Abdalla et al., 2014; Martínez et al., 2014; Lucas, 2016; ). Table 5 shows the genotyping and inferred phenotype results. Again, no statistically significant differences were observed between any of the patient’s subgroups and control individuals.

The only statistically significant difference observed was in the subgroup of patients with cross-hypersensitivity to drugs that are predominantly CYP2C9 substrates although the significance was weak and it was related to the CYP2C8 genotypes (Table 5). This difference (p = 0.043) is attributable to a lower frequency of carriers of CYP2C8*3/*3 among patients as compared to control individuals. However, such a difference was not statistically significant after FDR correction (p = 0.129). When patients were stratified according to the clinical presentation (Supplementary Tables S1–S4), the only statistically significant difference was related to a low frequency of NECD patients homozygous for the CYP2C8*3 allele, as compared to healthy individuals (p = 0.029). However, the statistical significance disappeared after FDR correction (p = 0.174).

Discussion

The role of COX-1 inhibition in the etiopathogenesis of cross-hypersensitivity to NSAIDs has been the object of controversy for years (Kowalski et al., 2007; Doña et al., 2018; Mastalerz et al., 2019). Supporting this hypothesis, it has been shown that COX-2 inhibitors are well tolerated among patients with cross-hypersensitivity to NSAIDs (Morales et al., 2014; Bakhriansyah et al., 2019) and that patients with PTGS1 gene variants related to a decreased activity (Agúndez et al., 2014; Agúndez et al., 2015b; Lucena et al., 2019) are at increased risk of developing cross-hypersensitivity to NSAIDs (García-Martín et al., 2021). Interestingly, preliminary evidence suggests that cross-hypersensitivity to NSAIDs is dose-dependent (Palmer, 2005; Kong et al., 2007; Kowalski et al., 2013; Blumenthal et al., 2017) and, therefore, it could be speculated that individuals with impaired NSAID clearance (and therefore increased drug exposure) might have increased risk of developing cross-hypersensitivity. This hypothesis, however, was not investigated in detail. Preliminary studies have shown the lack of association of Aspirin Induced Asthma and CYP2C19 genotypes (Kooti et al., 2020), which is not surprising since CYP2C19 is not relevant in aspirin metabolism. This aside, no studies have been conducted to assess the putative role of impaired NSAID metabolism in the risk of developing cross-hypersensitivity to NSAIDs.

Strengths in this study include a large sample of patients with cross-reactive hypersensitivity induced to NSAID (n = 499). This sample size allows a good statistical power. A limitation of this study is that plasma levels of the NSAIDs and metabolites could not be obtained because the serum of patients during the acute phase was not available. Therefore, the putative association between genotypes and plasma levels could not be ascertained. Nevertheless, it is widely accepted that the genetic variants analyzed in this study are strongly related to pharmacokinetic changes, and several clinical practice guidelines on CYP2C enzymes (all based on the potential of gene variants to induce pharmacokinetic changes in drugs known to be CYP2C substrates) have been published (Johnson et al., 2011, Johnson et al., 2017; Caudle et al., 2014; Hicks et al., 2017; Moriyama et al., 2017; Karnes et al., 2020; Lima et al., 2020; Theken et al., 2020; Westergaard et al., 2020). Another limitation is that treatment regimen was not specifically recorded, although usually the hypersensitivity reaction occurs after a single standard dose of the corresponding NSAID.

The results of this study do not support a major association between common CYP2C gene variants leading to altered NSAID metabolism and the risk of developing cross-hypersensitivity to NSAIDs. These findings are unexpected if the hypothesis of a putative dose-dependent COX-1 inhibition as a major factor in the development of cross-hypersensitivity is correct. However, the high sample size and the statistical power obtained in this study rule out a major association. It cannot be ruled out putative associations with very rare detrimental allelic variants that have not been analyzed here because of the extremely low frequencies, however, the lack of association with common detrimental alleles observed in this study makes it very unlikely that such putative associations with rare alleles might exist.

It is to be noted that all cases involved ASA, and that therefore, our conclusions are valid only for patients with cross-hypersensitivity involving ASA. CYP2C enzymes play a minor role in ASA metabolism (Agúndez et al., 2009). However, CYP2C9 plays a major role in the metabolism of salicylic acid to gentisic acid (Gómez-Tabales et al., 2020). Also, CYP2C9 is involved in the production of NADPH-dependent hydrogen peroxide in the presence of salicylic acid. Therefore, although the role of CYP2C9 in ASA biodisposition might be quantitatively small, a role in adverse reactions due to ASA cannot be ruled out.

The findings obtained in this study argue against the hypothesis of a dose-dependent (in this case a drug exposure-dependent) COX-1 inhibition as a relevant mechanism in cross-hypersensitivity to NSAIDs and, therefore, will add to the controversy of the mechanisms underlying the development of cross-hypersensitivity to NSAIDs. The main clinical implication of our findings is that we found no evidence supporting the utility of pre-emptive CYP2C genotyping aiming at drug selection for patients with a previous history of cross-hypersensitivity to NSAIDs. However, the findings obtained in this study do not rule out the potential of pharmacogenetics testing combined with phenotyping factors and testing for other genes involved in NSAID pharmacodynamics and/or genes involved in the development and the clinical presentation of the hypersensitivity reactions, such as genes related to the arachidonic acid pathway, as well as those related to inflammation mediators, and oxidative stress.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Prof. James McCue for his assistance in language editing.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Badajoz University Hospital, Málaga University Hospital, Madrid Cruz Roja Hospital, Barcelona Clinic Hospital, Madrid Infanta Leonor Hospital, Alcorcón University Hospital, and Elche University Hospital. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

Author contribution statement: All authors have made substantial contributions as follows: Study design: EG-M and JA. Manuscript Drafting: YM, EG-M and JA. Genotyping analyses: YM, EG-M, and JA. Statistical analyses MM, YM, and JA. Patient recruitment and clinical evaluation: JG-M, CC, RJ-E, JC-G, MT, NB-L, GC, MB, JL, JB, AR, and JF. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This work was partly supported by Grants PI15/00303, PI18/00540, and RETICS ARADyAL RD16/0006/0004 from Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain, and IB16170, IB20134 and GR18145 from Junta de Extremadura, Spain. Financed in part with FEDER funds from the European Union.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2021.648262/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abdalla S. O., Elouzi A. A., Saad S. E., Alem M. D. E. O., Nagaah T. A. (2014). Study on the Relationship between Genetic Polymorphisms of Cytochrome CYP2C19 and Metabolic Bioactivation of Dipyrone. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 6 (6), 992–999. [Google Scholar]

- Agúndez J. A., García-Martín E., Martínez C. (2009a). Genetically Based Impairment in CYP2C8- and CYP2C9-dependent NSAID Metabolism as a Risk Factor for Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Is a Combination of Pharmacogenomics and Metabolomics Required to Improve Personalized Medicine?. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 5 (6), 607–620. 10.1517/17425250902970998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agúndez J., Martínez C., Pérez-Sala D., Carballo M., Torres M., García-Martín E. (2009b). Pharmacogenomics in Aspirin Intolerance. Curr. Drug Metab. 10 (9), 998–1008. 10.2174/138920009790711814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agúndez J. A., Lucena M. I., Martínez C., Andrade R. J., Blanca M., Ayuso P., et al. (2011). Assessment of Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug-Induced Hepatotoxicity. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 7 (7), 817–828. 10.1517/17425255.2011.574613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agúndez J. A., Gonzalez-Alvarez D. L., Vega-Rodriguez M. A., Botello E., Garcia-Martin E. (2014). Gene Variants and Haplotypes Modifying Transcription Factor Binding Sites in the Human Cyclooxygenase 1 and 2 (PTGS1 and PTGS2) Genes. Curr. Drug Metab. 15 (2), 182–195. 10.2174/138920021502140327180336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agúndez J. A., Mayorga C., García-Martin E. (2015a). Drug Metabolism and Hypersensitivity Reactions to Drugs. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 15 (4), 277–284. 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agúndez J. A., Blanca M., Cornejo-García J. A., García-Martín E. (2015b). Pharmacogenomics of Cyclooxygenases. Pharmacogenomics 16 (5), 501–522. 10.2217/pgs.15.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agúndez J. A. G., Gómez-Tabales J., Ruano F., García-Martin E. (2018). The Potential Role of Pharmacogenomics and Biotransformation in Hypersensitivity Reactions to Paracetamol. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 18 (4), 302–309. 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Navarro H., Martínez C., García-Martín E., Benito-León J., García-Ferrer I., Vázquez-Torres P., et al. (2006). CYP2C19 Polymorphism and Risk for Essential Tremor. Eur. Neurol. 56 (2), 119–123. 10.1159/000095702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angeletti F., Meier F., Zöller N., Meissner M., Kaufmann R., Valesky E. M. (2020). Hypersensitivity Reactions to Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) - A Retrospective Study. J. Dtsch Dermatol. Ges. 18 (12), 1405–1414. 10.1111/ddg.14292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariza A., García-Martín E., Salas M., Montañez M. I., Mayorga C., Blanca-Lopez N., et al. (2016). Pyrazolones Metabolites Are Relevant for Identifying Selective Anaphylaxis to Metamizole. Sci. Rep. 6 (1), 23845. 10.1038/srep23845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahadur N., Leathart J. B., Mutch E., Steimel-Crespi D., Dunn S. A., Gilissen R., et al. (2002). CYP2C8 Polymorphisms in Caucasians and Their Relationship with Paclitaxel 6alpha-Hydroxylase Activity in Human Liver Microsomes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 64 (11), 1579–1589. 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01354-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhriansyah M., Meyboom R. H. B., Souverein P. C., de Boer A., Klungel O. H. (2019). Cyclo-oxygenase Selectivity and Chemical Groups of Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs and the Frequency of Reporting Hypersensitivity Reactions: a Case/noncase Study in VigiBase. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 33 (5), 589–600. 10.1111/fcp.12463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y., Drai D., Elmer G., Kafkafi N., Golani I. (2001). Controlling the False Discovery Rate in Behavior Genetics Research. Behav. Brain Res. 125 (1–2), 279–284. 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00297-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigler J., Whitton J., Lampe J. W., Fosdick L., Bostick R. M., Potter J. D. (2001). CYP2C9 and UGT1A6 Genotypes Modulate the Protective Effect of Aspirin on colon Adenoma Risk. Cancer Res. 61 (9), 3566–3569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanca-López N., Haroun-Diaz E., Ruano F. J., Pérez-Alzate D., Somoza M. L., Vázquez de la Torre Gaspar M., et al. (2018). Acetyl Salicylic Acid challenge in Children with Hypersensitivity Reactions to Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs Differentiates between Cross-Intolerant and Selective Responders. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 6 (4), 1226–1235. 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.08.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanca-López N., Soriano V., Garcia-Martin E., Canto G., Blanca M. (2019). NSAID-induced Reactions: Classification, Prevalence, Impact, and Management Strategies. J. Asthma Allergy 12, 217–233. 10.2147/JAA.S164806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco G., Martínez C., Ladero J. M., Garcia-Martin E., Taxonera C., Gamito F. G., et al. (2008). Interaction of CYP2C8 and CYP2C9 Genotypes Modifies the Risk for Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs-Related Acute Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Pharmacogenet Genom. 18 (1), 37–43. 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282f305a9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal K. G., Lai K. H., Wickner P. G., Goss F. R., Seger D. L., Slight S. P., et al. (2016). Reported Incidence of Hypersensitivity Reactions to Non-Steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs in the Electronic Health Record. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 137 (2), AB196. 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.772 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal K. G., Lai K. H., Huang M., Wallace Z. S., Wickner P. G., Zhou L. (2017). Adverse and Hypersensitivity Reactions to Prescription Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Agents in a Large Health Care System. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 5 (3), 737–e3. 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnabry P., Leemann T., Dayer P. (1996). Role of Human Liver Microsomal CYP2C9 in the Biotransformation of Lornoxicam. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 49 (4), 305–308. 10.1007/BF00226332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bort R., Macé K., Boobis A., Gómez-Lechón M. J., Pfeifer A., Castell J. (1999). Hepatic Metabolism of Diclofenac: Role of Human CYP in the Minor Oxidative Pathways. Biochem. Pharmacol. 58 (5), 787–796. 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00167-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botton M. R., Whirl‐Carrillo M., Del Tredici A. L., Sangkuhl K., Cavallari L. H., Agúndez J. A. G., et al. (2020). PharmVar GeneFocus: CYP2C19. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 109, 352–366. 10.1002/cpt.1973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrav P. D. S., Medhi B., Prakash A., Patyar S., Wadhwa S. (2009). Lornoxicam: a Newer NSAID. Indian J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 20 (1), 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Caimmi S., Caimmi D., Bousquet P. J., Demoly P. (2012). How Can We Better Classify NSAID Hypersensitivity Reactions?-Vvalidation from a Large Database. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 159 (3), 306–312. 10.1159/000337660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudle K. E., Rettie A. E., Whirl-Carrillo M., Smith L. H., Mintzer S., Lee M. T., et al. (2014). Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guidelines for CYP2C9 and HLA-B Genotypes and Phenytoin Dosing. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 96 (5), 542–548. 10.1038/clpt.2014.159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S. Y., Li W., Traeger S. C., Wang B., Cui D., Zhang H., et al. (2008). Confirmation that Cytochrome P450 2C8 (CYP2C8) Plays a Minor Role in (S)-(+)- and (R)-(-)-ibuprofen Hydroxylation In Vitro . Drug Metab. Dispos. 36 (12), 2513–2522. 10.1124/dmd.108.022970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesné C., Guyomard C., Guillouzo A., Schmid J., Ludwig E., Sauter T. (1998). Metabolism of Meloxicam in Human Liver Involves Cytochromes P4502C9 and 3A4. Xenobiotica 28 (1), 1–13. 10.1080/004982598239704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies N. M., Skjodt N. M. (1999). Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Meloxicam. A Cyclo-Oxygenase-2 Preferential Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 36 (2), 115–126. 10.2165/00003088-199936020-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies N. M., McLachlan A. J., Day R. O., Williams K. M. (2000). Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Celecoxib: a Selective Cyclo-Oxygenase-2 Inhibitor. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 38 (3), 225–242. 10.2165/00003088-200038030-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doña I., Barrionuevo E., Salas M., Laguna J. J., Agúndez J., García-Martín E., et al. (2018). NSAIDs-hypersensitivity Often Induces a Blended Reaction Pattern Involving Multiple Organs. Sci. Rep. 8 (1), 16710. 10.1038/s41598-018-34668-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doña I., Blanca-López N., Cornejo-García J. A., Torres M. J., Laguna J. J., Fernández J., et al. (2011). Characteristics of Subjects Experiencing Hypersensitivity to Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs: Patterns of Response. Clin. Exp. Allergy 41 (1), 86–95. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03651.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA (Food and Drug Administration) (1998). Celebrex (Celecoxib). Clinical Pharmacology and Biopharmaceutics Review. New Drug Application number: 20-998. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/98/20998.cfm (Accessed August 15, 2021).

- García-Martín E., García-Menaya J. M., Esguevillas G., Cornejo-García J. A., Doña I. (2021). Deep sequencing of prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase (PTGE) genes reveals genetic susceptibility for cross-reactive hypersensitivity to NSAID. Br. J. Pharmacol. 178 (5), 1218–1233. 10.1111/bph.15366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Martín E., Martínez C., Ladero J. M., Gamito F. J., Agúndez J. A. (2001). High Frequency of Mutations Related to Impaired CYP2C9 Metabolism in a Caucasian Population. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 57 (1), 47–49. 10.1007/s002280100264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Martín E., Martínez C., Tabarés B., Frías J., Agúndez J. A. (2004). Interindividual Variability in Ibuprofen Pharmacokinetics Is Related to Interaction of Cytochrome P450 2C8 and 2C9 Amino Acid Polymorphisms. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 76 (2), 119–127. 10.1016/j.clpt.2004.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Martín E., Martínez C., Ladero J. M., Agúndez J. A. (2006). Interethnic and Intraethnic Variability of CYP2C8 and CYP2C9 Polymorphisms in Healthy Individuals. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 10 (1), 29–40. 10.1007/BF03256440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Martín E., Esguevillas G., Blanca-López N., García-Menaya J., Blanca M., Amo G., et al. (2015). Genetic Determinants of Metamizole Metabolism Modify the Risk of Developing Anaphylaxis. Pharmacogenet Genom. 25 (9), 462–464. 10.1097/FPC.0000000000000157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Martín E., García-Menaya J. M., Esguevillas G., Cornejo-García J. A., Doña I., Jurado-Escobar R., Torres MJ., Blanca-López N., Canto G., Blanca M., Laguna JJ., Bartra J., Rosado A., Fernández J., Cordobćs C., Agúndez JAG.Deep sequencing of prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase (PTGE) genes reveals genetic susceptibility for cross-reactive hypersensitivity to NSAID. Br J Pharmacol. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021178 (5), 1218–1233. 10.1111/bph.15366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Tabales J., García-Martín E., Agúndez J. A. G., Gutierrez-Merino C. (2020). Modulation of CYP2C9 Activity and Hydrogen Peroxide Production by Cytochrome B5. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 15571. 10.1038/s41598-020-72284-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González J. R., Armengol L., Solé X., Guinó E., Mercader J. M., Estivill X., et al. (2007). SNPassoc: an R Package to Perform Whole Genome Association Studies. Bioinformatics 23 (5), 644–645. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González J. R., Armengol L., Guinó E., Solé X., Moreno V. (2014). SNPassoc: SNPs-Based Whole Genome Association Studies. Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/package=SNPassoc (Accessed August 15, 2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hamman M. A., Thompson G. A., Hall S. D. (1997). Regioselective and Stereoselective Metabolism of Ibuprofen by Human Cytochrome P450 2C. Biochem. Pharmacol. 54 (1), 33–41. 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00143-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrotin Y., de Leval X., Mathy-Hartet M., Mouithys-Mickalad A., Deby-Dupont G., Dogné J. M., et al. (2001). In Vitro effects of Aceclofenac and its Metabolites on the Production by Chondrocytes of Inflammatory Mediators. Inflamm. Res. 50 (8), 391–399. 10.1007/PL00000261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks J. K., Sangkuhl K., Swen J. J., Ellingrod V. L., Müller D. J., Shimoda K., et al. (2017). Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline (CPIC) for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 Genotypes and Dosing of Tricyclic Antidepressants: 2016 Update. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 102 (1), 37–44. 10.1002/cpt.597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutt A. J., Caldwell J., Smith R. L. (1986). The Metabolism of Aspirin in Man: a Population Study. Xenobiotica 16 (3), 239–249. 10.3109/00498258609043527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson S. G., Bieber T., Dahl R., Friedmann P. S., Lanier B. Q., Lockey R. F., et al. (2004). Revised Nomenclature for Allergy for Global Use: Report of the Nomenclature Review Committee of the World Allergy Organization. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 113 (5), 832–836. 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.12.591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. A., Gong L., Whirl-Carrillo M., Gage B. F., Scott S. A., Stein C. M., et al. (2011). Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guidelines for CYP2C9 and VKORC1 Genotypes and Warfarin Dosing. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 90 (4), 625–629. 10.1038/clpt.2011.185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. A., Caudle K. E., Gong L., Whirl-Carrillo M., Stein C. M., Scott S. A., et al. (2017). Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for Pharmacogenetics-Guided Warfarin Dosing: 2017 Update. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 102 (3), 397–404. 10.1002/cpt.668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnes J. H., Rettie A. E., Somogyi A. A., Huddart R., Fohner A. E., Formea C. M., et al. (2020). Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for CYP2C9 and HLA‐B Genotypes and Phenytoin Dosing: 2020 Update. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 109, 302–309. 10.1002/cpt.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J. S., Teuber S. S., Gershwin M. E. (2007). Aspirin and Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug Hypersensitivity. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 32 (1), 97–110. 10.1007/BF02686086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooti W., Abdi M., Malik Y. S., Nouri B., Jalili A., Rezaee M. A., et al. (2020). Association of CYP2C19 and HSP70 Genes Polymorphism with Aspirin- Exacerbated Respiratory Disease in a Kurd Population. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 20 (2), 256–262. 10.2174/1872214812666190527104329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski M. L., Borowiec M., Kurowski M., Pawliczak R. (2007). Alternative Splicing of Cyclooxygenase-1 Gene: Altered Expression in Leucocytes from Patients with Bronchial Asthma and Association with Aspirin-Induced 15-HETE Release. Allergy 62 (6), 628–634. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01366.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski M. L., Asero R., Bavbek S., Blanca M., Blanca-Lopez N., Bochenek G., et al. (2013). Classification and Practical Approach to the Diagnosis and Management of Hypersensitivity to Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs. Allergy 68 (10), 1219–1232. 10.1111/all.12260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladero J. M., Agúndez J. A., Martínez C., Amo G., Ayuso P., García-Martín E. (2012). Analysis of the Functional Polymorphism in the Cytochrome P450 CYP2C8 Gene Rs11572080 with Regard to Colorectal Cancer Risk. Front. Genet. 3, 278. 10.3389/fgene.2012.00278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leemann T., Transon C., Dayer P. (1993). Cytochrome P450TB (CYP2C): a Major Monooxygenase Catalyzing Diclofenac 4'-hydroxylation in Human Liver. Life Sci. 52 (1), 29–34. 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90285-b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Laidlaw T. (2019). Cross-reactivity and Tolerability of Celecoxib in Adult Patients with NSAID hypersensitivityThe Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 7 (8), 2891 In practice. 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.04.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima J. J., Thomas C. D., Barbarino J., Desta Z., Van Driest S. L., El Rouby N., et al. (2020). Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for CYP2C19 and Proton Pump Inhibitor Dosing. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 109, 1417–1423. 10.1002/cpt.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas S. (2016). The Pharmacology of Indomethacin. Headache 56 (2), 436–446. 10.1111/head.12769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucena M. I., García-Martín E., Daly A. K., Blanca M., Andrade R. J., Agúndez J. A. G. (2019). Next-Generation Sequencing of PTGS Genes Reveals an Increased Frequency of Non-synonymous Variants Among Patients with NSAID-Induced Liver Injury. Front. Genet. 10, 134. 10.3389/fgene.2019.00134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macías Y., Gómez Tabales J., García-Martín E., Agúndez J. A. G. (2020). An Update on the Pharmacogenomics of NSAID Metabolism and the Risk of Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 16 (4), 319–332. 10.1080/17425255.2020.1744563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez C., García-Martín E., Ladero J. M., Sastre J., Garcia-Gamito F., Diaz-Rubio M., et al. (2001). Association of CYP2C9 Genotypes Leading to High Enzyme Activity and Colorectal Cancer Risk. Carcinogenesis 22 (8), 1323–1326. 10.1093/carcin/22.8.1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez C., García-Martín E., Blanco G., Gamito F. J., Ladero J. M., Agúndez J. A. (2005). The Effect of the Cytochrome P450 CYP2C8 Polymorphism on the Disposition of (R)-ibuprofen Enantiomer in Healthy Subjects. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 59 (1), 62–69. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02183.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez C., Andreu I., Amo G., Miranda M. A., Esguevillas G., Torres M. J., et al. (2014). Gender and Functional CYP2C and NAT2 Polymorphisms Determine the Metabolic Profile of Metamizole. Biochem. Pharmacol. 92(3), 457–466. 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastalerz L., Tyrak K. E., Ignacak M., Konduracka E., Mejza F., Ćmiel A., et al. (2019). Prostaglandin E2 Decrease in Induced Sputum of Hypersensitive Asthmatics during Oral challenge with Aspirin. Allergy 74 (5), 922–932. 10.1111/all.13671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miners J. O., Coulter S., Tukey R. H., Veronese M. E., Birkett D. J. (1996). Cytochromes P450, 1A2, and 2C9 Are Responsible for the Human Hepatic O-Demethylation of R- and S-Naproxen. Biochem. Pharmacol. 51 (8), 1003–1008. 10.1016/0006-2952(96)85085-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales D. R., Lipworth B. J., Guthrie B., Jackson C., Donnan P. T., Santiago V. H. (2014). Safety Risks for Patients with Aspirin-Exacerbated Respiratory Disease after Acute Exposure to Selective Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs and COX-2 Inhibitors: Meta-Analysis of Controlled Clinical Trials. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 134 (1), 40–45. 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.10.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriyama B., Obeng A. O., Barbarino J., Penzak S. R., Henning S. A., Scott S. A., et al. (2017). Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guidelines for CYP2C19 and Voriconazole Therapy. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 102 (1), 45–51. 10.1002/cpt.583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neunzig I., Göhring A., Drăgan C. A., Zapp J., Peters F. T., Maurer H. H., et al. (2012). Production and NMR Analysis of the Human Ibuprofen Metabolite 3-hydroxyibuprofen. J. Biotechnol. 157 (3), 417–420. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palikhe N. S., Kim S. H., Nam Y. H., Ye Y. M., Park H. S. (2011). Polymorphisms of Aspirin-Metabolizing Enzymes CYP2C9, NAT2 and UGT1A6 in Aspirin-Intolerant Urticaria. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 3 (4), 273–276. 10.4168/aair.2011.3.4.273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer G. M. (2005). A Teenager with Severe Asthma Exacerbation Following Ibuprofen. Anaesth. Intensive Care 33 (2), 261–265. 10.1177/0310057X0503300218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Alzate D., Cornejo-García J., Pérez-Sánchez N., Andreu I., García-Moral A., Agúndez J., et al. (2017). Immediate Reactions to More Than 1 NSAID Must Not Be Considered Cross-Hypersensitivity unless Tolerance to ASA Is Verified. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 27 (1), 32–39. 10.18176/jiaci.0080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perini J. A., Vianna-Jorge R., Brogliato A. R., Suarez-Kurtz G. (2005). Influence of CYP2C9 Genotypes on the Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Piroxicam. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 78 (4), 362–369. 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaza-Serón M. D. C., García-Martín E., Agúndez J. A., Ayuso P. (2018). Hypersensitivity Reactions to Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs: an Update on Pharmacogenetics Studies. Pharmacogenomics 19 (13), 1069–1086. 10.2217/pgs-2018-0079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt V. M., Del Tredici A. L., Hachad H., Ji Y., Kalman L. V., Scott S. A., et al. (2018). Recommendations for Clinical CYP2C19 Genotyping Allele Selection: a Report of the Association for Molecular Pathology. J. Mol. Diagn. 20 (3), 269–276. 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2018.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt V. M., Cavallari L. H., Del Tredici A. L., Hachad H., Ji Y., Moyer A. M., et al. (2019). Recommendations for Clinical CYP2C9 Genotyping Allele Selection: a Joint Recommendation of the Association for Molecular Pathology and College of American Pathologists. J. Mol. Diagn. 21 (5), 746–755. 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2019.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Borges M. (2010). NSAID Hypersensitivity (Respiratory, Cutaneous, and Generalized Anaphylactic Symptoms). Med. Clin. North. Am. 94 (4), 853. 10.1016/j.mcna.2010.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Gómez F. J., Díez-Dacal B., García-Martín E., Agúndez J. A., Pajares M. A., Pérez-Sala D. (2016). Detoxifying Enzymes at the Cross-Roads of Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Drug Hypersensitivity: Role of Glutathione Transferase P1-1 and Aldose Reductase. Front. Pharmacol. 7, 237. 10.3389/fphar.2016.00237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh G. (2000). Gastrointestinal Complications of Prescription and Over-the-counter Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs: a View from the ARAMIS Database. Arthritis, Rheumatism, and Aging Medical Information System. Am. J. Ther. 7 (2), 115–121. 10.1097/00045391-200007020-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skjodt N. M., Davies N. M. (1998). Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Lornoxicam. A Short Half-Life Oxicam. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 34 (6), 421–428. 10.2165/00003088-199834060-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczeklik A., Niżankowska-Mogilnicka E., Sanak M. (2009). “Hypersensitivity to Aspirin and Non-Steroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs,” in Middelton’s Allergy, Principles and Practice. Editors Adkinson N. F., Bochner B. S., Busse W. W., Holgate S. T., Lemanske R. F., Simons F. E. R.. 7th ed (Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; ), 1227–1243. 10.1016/b978-0-323-05659-5.00069-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C., Shou M., Rushmore T. H., Mei Q., Sandhu P., Woolf E. J., et al. (2001). In-vitro Metabolism of Celecoxib, a Cyclooxygenase-2 Inhibitor, by Allelic Variant Forms of Human Liver Microsomal Cytochrome P450 2C9: Correlation with CYP2C9 Genotype and In-Vivo Pharmacokinetics. Pharmacogenetics 11 (3), 223–235. 10.1097/00008571-200104000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theken K. N., Lee C. R., Gong L., Caudle K. E., Formea C. M., Gaedigk A., et al. (2020). Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline (CPIC) for CYP2C9 and Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 108 (2), 191–200. 10.1002/cpt.1830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiessen J. J. (1983). Aspirin: Plasma Concentration and Effects. Thromb. Res. Suppl. 4, 105–111. 10.1016/0049-3848(83)90365-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornio A., Niemi M., Neuvonen P. J., Backman J. T. (2007). Stereoselective Interaction between the CYP2C8 Inhibitor Gemfibrozil and Racemic Ibuprofen. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 63 (5), 463–469. 10.1007/s00228-007-0273-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Türck D., Roth W., Busch U. (1996). A Review of the Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Meloxicam. Br. J. Rheumatol. 35 (Suppl. 1), 13–16. 10.1093/rheumatology/35.suppl_1.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westergaard N., Søgaard Nielsen R., Jørgensen S., Vermehren C. (2020). Drug Use in Denmark for Drugs Having Pharmacogenomics (PGx) Based Dosing Guidelines from CPIC or DPWG for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 Drug-Gene Pairs: Perspectives for Introducing PGx Test to Polypharmacy Patients. J. Pers Med. 10 (1), 3. 10.3390/jpm10010003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigginton J. E., Cutler D. J., Abecasis G. R. (2005). A Note on Exact Tests of Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 76 (5), 887–893. 10.1086/429864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.