The rice 2-oxoglutarate/Fe(II)-dependent dioxygenase HIS1 and related enzymes show broad substrate specificity and mediate metabolism of the growth regulator trinexapac-ethyl and herbicides.

Abstract

The rice (Oryza sativa) 2-oxoglutarate (2OG)/Fe(II)-dependent dioxygenase HIS1 mediates the catalytic inactivation of five distinct β-triketone herbicides (bTHs). By assessing the effects of plant growth regulators on HIS1 enzyme function, we found that HIS1 mediates the hydroxylation of trinexapac-ethyl (TE) in the presence of Fe2+ and 2OG. TE blocks gibberellin biosynthesis, and we observed that its addition to culture medium induced growth retardation of rice seedlings in a concentration-dependent manner. Similar treatment with hydroxylated TE revealed that hydroxylation greatly attenuated the inhibitory effect of TE on plant growth. Forced expression of HIS1 in a rice his1 mutant also reduced its sensitivity to TE compared with that of the nontransformant. These results indicate that HIS1 metabolizes TE and thereby markedly reduces its ability to slow plant growth. Furthermore, analysis of five rice HIS1-like (HSL) proteins revealed that OsHSL2 and OsHSL4 also metabolize TE in vitro. HSLs from wheat (Triticum aestivum) and barley (Hordeum vulgare) also showed such activity. In contrast, OsHSL1, which shares the highest amino acid sequence identity with HIS1 and metabolizes the bTH tefuryltrione, did not manifest TE-metabolizing activity. Site-directed mutagenesis of OsHSL1 informed by structural models showed that substitution of three amino acids with the corresponding residues of HIS1 conferred TE-metabolizing activity similar to that of HIS1. Our results thus reveal a catalytic promiscuity of HIS1 and its related enzymes that support xenobiotic metabolism in plants.

Introduction

Modern agriculture essentially depends on the many types of chemicals that are now applied for the control of crop diseases, insect pests, weeds, and plant growth and development. Weed control by herbicides relies on intrinsic or artificially introduced enzymes in the crop which are able to mediate metabolic inactivation of the applied chemicals (Kraehmer et al., 2014a, 2014b).

We previously described the isolation and characterization of a rice herbicide resistance gene, HIS1, that encodes an Fe(II)- and 2-oxoglutarate (2OG)-dependent dioxygenase (2OGD; Maeda et al., 2019). Biochemical analysis and plant transformation tests revealed that HIS1 catalyzes the hydroxylation of five β-triketone herbicides (bTHs): benzobicyclon (BBC), tefuryltrione (2-{2-Chloro-4-mesyl-3-[(RS)-tetrahydro-2-furylmethoxymethyl]benzoyl}cyclohexane-1,3-dione; TFT), sulcotrione, mesotrione, and tembotrione. These bTHs target 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase, which is structurally unrelated to 2OGD enzymes but mechanistically grouped with α-keto acid-dependent oxygenases and members of the 2OGD superfamily (He and Moran, 2009). We also uncovered wide conservation of genes that encode HIS1-like (HSL) proteins in other major crops including wheat (Triticum aestivum), corn (Zea mays), barley (Hordeum vulgare), and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor). A search of the genome database for rice (Oryza sativa L. cv Nipponbare) revealed five predicted HSLs in addition to HIS1. We further found that rice OsHSL1 metabolizes TFT and that forced expression of OsHSL1 conferred TFT resistance in rice and Arabidopsis (Maeda et al., 2019), whereas other HSLs did not manifest metabolic activity for bTHs. The comprehensive conservation of HSL genes among major crops is suggestive of common and important functions; however, the natural substrates of the encoded enzymes remain uncharacterized.

All the predicted HSL proteins possess conserved signature motifs of 2OGD enzymes in their amino acid sequences (Hegg and Que, 1997; Wilmouth et al., 2002; Kawai et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2021). 2OGD enzymes rely on 2OG as a cosubstrate and convert it to succinate. Several compounds that mimic 2OG or succinate and impede the enzyme reaction have been developed as gibberellin biosynthesis inhibitors (Brown et al., 1997; Rademacher, 2000, 2016; Ervin and Koski, 2001; McCarty et al., 2004). Some of these compounds are applied as growth retardants for turfgrass management (Rademacher, 2000, 2016; Baldwin et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2016). On the other hand, the target enzymes of these growth retardants have not been specified because of their potentially broad spectrum of action. We initially conjectured that these compounds might also affect HSL enzymes, and we began to test general 2OGD inhibitors—such as daminozide, prohexadione (PR), and trinexapac-ethyl (TE)—for potential inhibitory effects on HIS1 activity in vitro. During this testing, we found that the rice enzyme HIS1 metabolizes TE and we confirmed that the metabolite produced by HIS1 is a hydroxylated form of TE (TE-OH). We further observed that forced expression of HIS1 reduces the TE sensitivity of rice. OsHSL1, the closest paralog of HIS1, was found not to possess TE-hydroxylating activity, whereas OsHSL2 and OsHSL4, both of which are less similar to HIS1 than is OsHSL1, did manifest HSL TE-metabolizing activity. Mutation analysis based on a comparison of the amino acid sequences of HIS1 and OsHSL proteins revealed that the substitution of three amino acids of OsHSL1 with the corresponding residues of HIS1 conferred TE-metabolizing activity. In addition, HSL proteins of wheat and barley were shown to possess TE-metabolizing activity in vitro. These findings have thus revealed two specific characteristics of HIS1 and HSL enzymes: (1) their catalytic activities do not necessarily reflect amino acid sequence similarity and (2) their substrates include a broad-spectrum 2OGD inhibitor.

Results

PR partially inhibits the bTH-metabolizing activity of HIS1 in vitro

We previously showed that HSL genes are highly conserved among poaceous species, suggestive of common and important roles of HSL gene products in major crops (Maeda et al., 2019). However, the natural substrate (or substrates) of HIS1 and HSL proteins remains poorly understood. To determine conditions that allow accumulation of the natural substrate of HIS1 in plants, we explored the potential inhibitory effects of three general 2OGD inhibitors—daminozide, PR, and TE—on HIS1 activity in vitro (Figure 1A). For these assays, we used BBC hydrolysate (BBC-OH; Figure 1A) as a substrate of HIS1, as described previously (Maeda et al., 2019).

Figure 1.

Analysis of the effects of plant growth regulators on enzyme activity of HIS1 and OsHSL1 in vitro. A, Structures of chemical compounds used in the study. B, HPLC analysis of reaction mixtures after assay of HIS1 activity with BBC-OH as substrate in the absence or presence of PR (50 µM). Peak positions for BBC-OH, the BBC-OH metabolite (hydroxylated form), and PR are indicated. mAU, milli-absorbance unit. C, HPLC analysis of reaction mixtures after assay of OsHSL1 activity with TFT as a substrate in the absence or presence of PR (50 µM). Peak positions for TFT, the TFT metabolite, and PR are indicated.

We found that PR partially inhibited the BBC-OH hydroxylation activity of recombinant HIS1 in vitro (Figure 1B), whereas daminozide showed no effect on the enzyme activity (data not shown). Given that the amino acid sequence of OsHSL1 is 87% identical to that of HIS1, we next examined the effect of PR in an OsHSL1 enzyme assay with TFT (Figure 1A) as the substrate. PR also partially inhibited the TFT hydroxylation activity of OsHSL1 (Figure 1C). The median inhibitory concentration (IC50) for the effect of PR on HIS1 activity was relatively high at ∼50 µM (Supplemental Figure S1A), and its efficacy was likely not sufficient for suppression of HIS1 and OsHSL1 catalysis in plants. Lineweaver–Burk plot analysis indicated that the mode of PR inhibition of HIS1 activity is likely competition with the cosubstrate, 2OG (Supplemental Figure S1B).

HIS1 metabolizes TE in vitro

We next tested the effect of TE on HIS1 catalysis with BBC-OH as substrate. Unexpectedly, we found that TE is recognized as a substrate by HIS1 (Figure 2A). In the reaction catalyzed by HIS1 in the presence of both Fe2+ and 2OG, TE was converted to two metabolites represented by a dominant peak (Metabolite 1) and a smaller peak (Metabolite 2) in the high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) profile. This conversion did not occur in the absence of either Fe2+ or 2OG (Supplemental Figure S2A), indicating that it was attributable to the function of HIS1 as a 2OGD.

Figure 2.

Hydroxylation of TE by HIS1 in vitro. A, LC profile of TE and its HIS1-generated metabolites prior to ESI–MS analysis. The red trace indicates the profile of the reaction mixture after incubation of recombinant HIS1 with TE in the presence of Fe2+ and 2OG. As a negative control, recombinant GFP was tested and profiled under equivalent conditions (black trace). B, MS analysis and predicted structure of TE Metabolite 1 generated by HIS1 catalysis. Data from LC–ESI–MS analysis (upper) and MS/MS analysis (lower) in the positive mode are shown for purified Metabolite 1 as in (A). The predicted structure of the compound based on these results and NMR data (Supplemental Table S1) is also shown. The blue shading indicates the hydroxylated position. Predicted cleavage positions for Metabolite 1 in the MS/MS analysis are indicated by red dotted lines. C, Similar analysis for purified Metabolite 2 of TE generated as in (A). The predicted structure of the compound is shown, with the blue shading indicating the C=C position.

We isolated these two TE metabolites and analyzed their structures. Analysis by liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization–mass spectrometry (LC–ESI–MS) revealed that Metabolite 1 (mass charge ratio [m/z] = 269.10160; Figure 2B) has a mass that is greater than that of the parent molecule (m/z = 253.11144; Supplemental Figure S2B) by 16. In contrast, the mass of Metabolite 2 (m/z = 251.09056) was found to be smaller than that of the parent molecule (Figure 2C). Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis of the isolated Metabolite 1 (hereafter referred to as TE-OH) revealed that it possesses a hydroxyl group at the p-position (Supplemental Table S1). We therefore identified TE Metabolite 1 as ethyl 4-(cyclopropanecarbonyl)-1-hydroxy-3,5-dioxocyclohexane-1-carboxylate (Figure 2B). We predicted Metabolite 2 to be a cyclohexene derivative (Figure 2C) on the basis of the ESI–MS and tandem MS (MS/MS) data.

In vivo effects of TE and TE-OH in rice

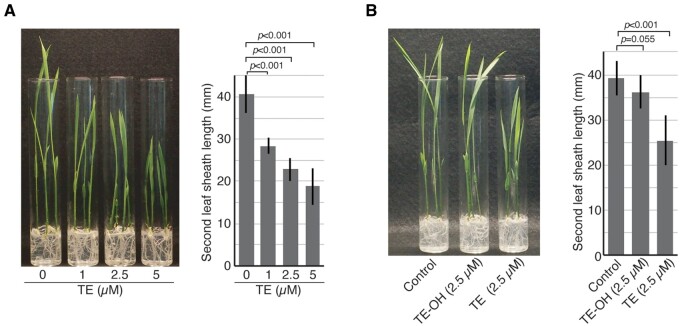

To examine the physiological effects of exogenously applied TE on the growth of rice seedlings, we performed a growth test for rice with or without TE treatment. We evaluated elongation of the second leaf sheath of seedlings as a measure of gibberellin action. Treatment of Nipponbare with TE resulted in a smaller second leaf sheath length compared with that of untreated seedlings, with this effect of TE being concentration-dependent (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Effects of TE and TE-OH on the growth of rice seedlings. Seeds of rice cultivar Nipponbare were germinated and cultured on solid medium for 7 d in the absence or presence of the indicated concentrations of TE (A) or of TE or TE-OH (B). Representative seedlings as well as quantitative data for the length of the second leaf sheath are shown. The quantitative results are mean ± sd values for 11–14 independent biological replicates. The P-values were determined with Student’s t test.

Given that HIS1 was shown to catalyze the hydroxylation of TE in vitro (Figure 2), we next examined whether such hydroxylation might abolish the toxicity of TE by testing the effect of TE-OH on the growth of rice seedlings. TE was converted to TE-OH by the HIS1 enzyme reaction, and the effects of TE-OH and TE on seedling growth were then compared. TE-OH had a much weaker inhibitory effect on internode elongation in Nipponbare seedlings compared with TE (Figure 3B), indicating that hydroxylation of TE by HIS1 greatly diminishes its inhibitory effect on plant growth.

We next tested the TE sensitivity of rice strains that overexpress HIS1 under the control of the 35S promoter of cauliflower mosaic virus (Maeda et al., 2019). Forced expression of HIS1 rendered Yamadawara, which is a his1/his1 mutant homozygote, partially tolerant to TE. The second leaf sheath of the HIS1-overexpressing seedlings was thus longer than that of the parental strain after TE treatment (Figure 4; Supplemental Table S2). The transformant line #6 appeared to be more resistant to TE than was transformant line #5. Given that we previously showed that the HIS1 expression level in line #6 is about twice that in line #5 (Maeda et al., 2019), the TE insensitivity phenotype of the transformant lines appeared to reflect the level of HIS1 expression.

Figure 4.

Effect of HIS1 overexpression on TE sensitivity in a his1 rice mutant line. A, Seeds of Yamadawara (his1 mutant) or its transformant lines #5 and #6 that express HIS1 under the control of the 35S promoter of cauliflower mosaic virus were germinated and cultured on solid medium for 7 d in the absence or presence of 1 µM TE. B, Length of the second leaf sheath for seedlings as in (A). Data are means ± sd for three or four independent biological replicates (see Supplemental Table S2). The P-values were determined with Student’s t test.

We examined TE metabolism in the tested rice lines by LC–ESI–MS and found that TE was essentially undetectable in Yamadawara or transformant lines #5 or #6 after TE treatment (Table 1). In contrast, the amount of a compound with the same molecular mass as TE-OH was increased in the roots and culture medium of both transgenic lines. The accumulation of a metabolite corresponding to trinexapac, a well-characterized major metabolite of TE in plants (Hiemstra and de Koh, 2003), was also apparent in plant tissue and culture medium for parental and transgenic lines, with the extent of such accumulation in culture medium being lower for the transgenic lines than for the parental line.

Table 1.

TE metabolism in plants

| Yamadawara | Detected TE (mg/kg fresh weight or µg/mL) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stem and leaf | Root | Medium | |

| Nontransgenic | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.00 |

| HIS1 transgenic #5 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.005 |

| HIS1 transgenic #6 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Yamadawara | Detected TE-OH (mg/kg fresh weight or µg/mL) | ||

| Stem and leaf | Root | Medium | |

| Nontransgenic | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| HIS1 transgenic #5 | <0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.02 |

| HIS1 transgenic #6 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.01 |

| Yamadawara | Detected trinexapac (mg/kg fresh weight or µg/mL) | ||

| Stem and leaf | Root | Medium | |

| Nontransgenic | 0.78 ± 0.05 | 0.96 ± 0.17 | 0.70 ± 0.02 |

| HIS1 transgenic #5 | 0.70 ± 0.05 | 1.09 ± 0.10 | 0.48 ± 0.02 |

| HIS1 transgenic #6 | 0.65 ± 0.02 | 1.11 ± 0.13 | 0.44 ± 0.02 |

Transgenic or nontransgenic Yamadawara rice seeds were sown on MS medium. After 3 d, the germinated seedlings were transferred to test tubes containing MS medium, cultured for 3 d, and then transferred to new tubes containing 3.6 μM TE in 0.2× MS basal liquid medium for growth for an additional 4 d before harvest. Culture for the entire period was performed at 27°C with 16 h of light (40 μmol m−2 s−1) per day. Root and leaf (including stem) extracts of the harvested plants, as well as the medium, were analyzed by LC–ESI–MS for quantitation of TE, TE-OH, and trinexapac. Analyte content is expressed as milligrams per kilogram of fresh weight for plant tissue samples or as micograms per milliliter for medium. Data are means ± sd for three independent trials, each performed with three seeds of each genotype.

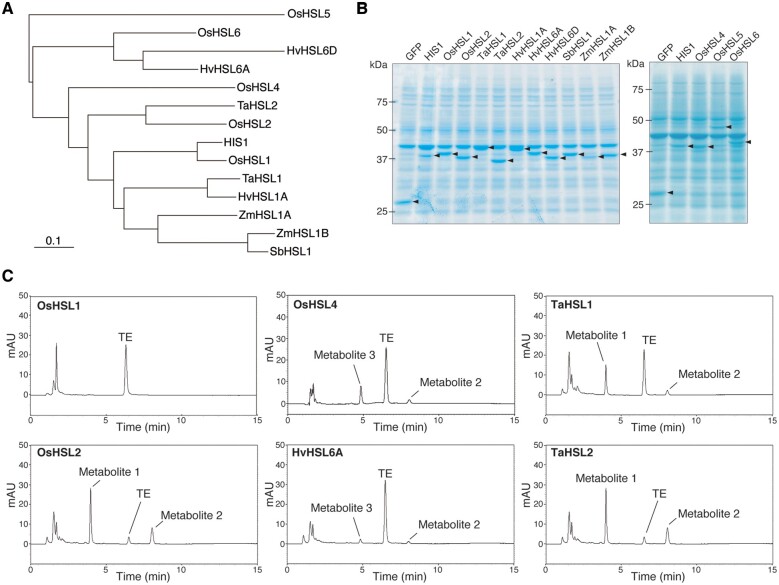

OsHSL2, OsHSL4, and other HSL proteins possess TE-metabolizing activity in vitro

We previously showed that HIS1 and OsHSL1 share 87% amino acid sequence identity and that HIS1 catalyzes the hydroxylation of multiple bTHs, including BBC-OH and TFT, whereas OsHSL1 catalyzes the hydroxylation only of TFT (Maeda et al., 2019). We next performed the TE hydroxylation assay with OsHSL1 and other HSL proteins including OsHSL2, OsHSL4, OsHSL5, and OsHSL6 (rice); TaHSL1 and TaHSL2 (wheat); HvHSL1A, HvHSL6A, and HvHSL6D (barley); SbHSL1 (sorghum); and ZmHSL1A and ZmHSL1B (corn) (Figure 5, A and B). We found that OsHSL1 did not manifest TE conversion activity (Figure 5C). Further examination of the effect of TE on OsHSL1 function revealed that it slightly inhibited OsHSL1 activity with a relatively high IC50 of ∼125 µM for TFT conversion (Supplemental Figure S3). The inhibitory effect was too weak for determination of the mode of inhibition, but TE did not appear to compete with the substrate, TFT (Supplemental Figure S3). On the other hand, the two rice enzymes OsHSL2 and OsHSL4, the two wheat enzymes TaHSL1 and TaHSL2, and the barley enzyme HvHSL6A all showed TE hydroxylation activity in vitro (Figure 5C and Table 2), whereas the other HSL proteins tested did not show such activity (Supplemental Figure S4). The TE metabolites detected with an elution time similar to that of Metabolite 1 in the reactions with OsHSL2, TaHSL1, or TaHSL2 were analyzed by ESI–MS and MS/MS, with the results indicating that these compounds are indeed Metabolite 1 (Supplemental Figure S5). Likewise, the peaks detected with an elution time similar to that of Metabolite 2 in the reactions with OsHSL2, OsHSL4, TaHSL1, TaHSL2, or HvHSL6A were confirmed to be Metabolite 2 (Supplemental Figure S6). Additional TE metabolites with similar elution times were generated in the reactions with OsHSL4 and HvHSL6A (Figure 5C). ESI–MS and MS/MS indicated that these metabolites (designated Metabolite 3) both corresponded to a form of TE hydroxylated at position C2 (Supplemental Figures S7 and S8). The observed activity for TE metabolism of these various HSL proteins did not appear to reflect the phylogenetic relations among the proteins (Figure 5A), suggesting that overall similarity in amino acid sequence does not necessarily correspond to that in catalytic function in TE metabolism.

Figure 5.

TE-metabolizing activity of various HSL proteins in vitro. A, Phylogenetic tree for HIS1 and HSL proteins analyzed in this study. Prefixes Os, Ta, Hv, Sb, and Zm indicate O. sativa, T. aestivum, H. vulgare, S. bicolor, and Z. mays, respectively. Scale bar indicates 0.1 amino acid changes per alignment position. B, Coomassie brilliant blue-stained gel after sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) of HIS1, HSL proteins, and GFP (control) produced in a cell-free translation system. Arrowheads indicate the specific recombinant proteins. Sizes (kDa) of molecular mass markers are indicated on the left. C, HPLC profiles of the reaction mixtures after incubation of recombinant OsHSL1, OsHSL2, OsHSL4, HvHSL6A, TaHSL1, or TaHSL2 with TE in the presence of Fe2+ and 2OG. Each experiment was performed at least twice to confirm reproducibility.

Table 2.

Metabolic activities of HIS1 and various HSL proteins for TE, BBC-OH, and TFT

| Protein | Activity (U/µg) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| TE | BBC-OH | TFT | |

| HIS1 | 174.14 ± 1.25 | 50.45 ± 1.28a | 159.16 ± 3.29a |

| OsHSL1 | <0.1 | 4.57 ± 0.49a | 133.01 ± 8.3a |

| OsHSL2 | 72.84 ± 0.73 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| OsHSL4 | 17.55 ± 0.30 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| OsHSL5 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| OsHSL6 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| TaHSL1 | 0.92 ± 0.14 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| TaHSL2 | 3.81 ± 0.70 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

The specific activity of recombinant HIS1 and HSL proteins for each compound was determined from the estimated amount of protein in the translation reaction mixture as previously described (Maeda et al., 2019). One unit (U) of enzyme activity is defined as the conversion of 1 μmol of substrate per minute at 30°C under the assay conditions specified in “Materials and methods.” Specific activity was calculated as units per microgram of protein. Data are means ± sd for three separate reactions performed with the same preparation of protein. aData are from a previous study (Maeda et al., 2019).

Amino acid substitutions in OsHSL1 confer TE-metabolizing activity

To shed light on the differences in substrate specificity among the three closely related enzymes HIS1, OsHSL1, and OsHSL2, we generated 3D structural models of these proteins with the crystal structure of Arabidopsis thaliana jasmonate-induced oxygenase 2 (JOX2; Zhang et al., 2021) as a template and then carried out mutation analysis for OsHSL1. The structural models suggested the presence of a double-stranded β-helix, a typical structural signature for 2OGDs (Hegg and Que, 1997; Wilmouth et al., 2002; Kawai et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2021), in all three rice proteins (Figure 6A). On the basis of these models and sequence alignment, differences in amino acid residues were narrowed down to suggest potential substrate contact sites (Figure 6). We focused on the putative substrate-recognition pocket of OsHSL1—in particular, on the three residues Phe140, Leu204, and Phe298—for mutation analysis (Figure 6B). Mutant OsHSL1 enzymes were synthesized in a cell-free system and assayed for their ability to metabolize TE in vitro. Single amino acid substitutions based on the HIS1 sequence—OsHSL1_F140H, OsHSL1_L204F, and OsHSL1_F298L—had essentially no effect on the catalytic activity of OsHSL1 with TE as substrate (Supplemental Figure S9). In contrast, the double mutants OsHSL1_F140H/L204F, OsHSL1_F140H/F298L, and OsHSL1_L204F/F298L showed substantial TE-metabolizing activity (Table 3; Supplemental Figure S9). Furthermore, the combination of all three mutations (OsHSL1_F140H/L204F/F298L) increased TE-metabolizing activity to 66.01 U/µg, which is similar to that of OsHSL2 (72.84 U/µg; Tables 2 and 3; Supplemental Figure S9).

Figure 6.

3D structure models of HIS1 and HSL proteins. A, Structure models for HIS1, OsHSL1, OsHSL2, and the mutant OsHSL1_F140H/L204F/F298L (OsHSL1_3MT) were built and molecular docking simulations with TE were performed as described in “Materials and methods.” The overall structure models are shown as ribbon representations with HIS1 in yellow, OsHSL1 and OsHSL1_3MT in green, and OsHSL2 in blue. The two magnified images shown to the right of each overall structure represent the putative substrate pocket and predicted location of bound TE in the pocket (left and right, respectively). Three important residues in the region of the putative substrate pocket are labeled and shown as sphere representations. The Fe atom (red sphere) was manually modeled at the triads of His226/Asp228/His283 for HIS1, His225/Asp227/His282 for OsHSL1, and His227/Asp229/His285 for OsHSL2 with the use of JOX2 (Zhang et al., 2021) as a reference. The triad residues and the TE molecule are shown as stick models. B, Alignment of the predicted amino acid sequences of HIS1 (GenBank accession no. BCK50777), OsHSL1 (BCK50778), and OsHSL2 (LC505696) from O. sativa. The alignment was performed with the CLUSTALW algorithm. Blue lines and green arrows indicate predicted α-helix and β-sheet secondary structures, respectively. Red circles indicate the positions of amino acid substitutions in OsHSL1.

Table 3.

TE-metabolizing activity of OsHSL1 mutant proteins

| Protein | Activity (U/µg) |

|---|---|

| OsHSL1_F140H/L204F | 1.26 ± 0.18 |

| OsHSL1_F140H/F298L | 1.54 ± 0.17 |

| OsHSL1_L204F/F298L | 1.25 ± 0.15 |

| OsHSL1_F140H/L204F/F298L | 66.01 ± 3.98 |

Specific activity was calculated as units per microgram of protein. Data are means ± sd for three separate reactions performed with the same preparation of protein.

On the basis of our structural models, including that for OsHSL1_F140H/L204F/F298L, we performed molecular docking simulations with the substrate TE (Figure 6A). Estimated change in Gibbs free energy values for the four conformations shown in Figure 6A ranges from −6.0 to −7.6 kcal/mol. The predicted TE configuration nearby the Fe atom in HIS1 appeared reasonable. In contrast, the TE configuration for OsHSL1 was predicted to be too distant from the Fe atom for a substrate (Supplemental Figure S10). However, the TE configuration for OsHSL1_F140H/L204F/F298L was predicted to be similar to that for HIS1. These predictions thus showed good agreement with the results of the enzyme activity assays. On the other hand, the docking model for OsHSL2-TE suggested a different TE configuration from that for HIS1-TE (Figure 6A).

Discussion

This study originated from tests of the effects of three general 2OGD inhibitors—daminozide, PR, and TE—on HIS1 enzyme activity. All three of these compounds act as late-stage gibberellin biosynthetic inhibitors (Rademacher, 2000, 2016). We found that PR partially inhibited the activities of both HIS1 and OsHSL1 in vitro. TE also had a relatively weak inhibitory effect on OsHSL1 activity. These compounds were designed as 2OG- or succinate-mimicking agents and therefore could affect multiple 2OGD enzymes (Rademacher, 2000, 2016). Our results now indicate that these general 2OGD inhibitors indeed affect some members of the HSL family of enzymes in plants. Our biochemical analysis suggests that the mode of inhibitory action of these compounds is likely competition with 2OG rather than with herbicide substrates. However, their inhibitory effects on HIS1 or OsHSL1 activity appear to be insufficient to result in a substantial disturbance of cellular metabolism mediated by these enzymes.

On the other hand, we unexpectedly found that HIS1 metabolizes TE in vitro. This work demonstrates a TE-metabolizing enzyme in plants. In agricultural practice, TE is applied worldwide as an antilodging agent for cereals (Rademacher and Bucci, 2002; Rademacher, 2016) and a chemical ripener for sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum; van Heerden, 2014). It is also used for turf management (Fagerness et al., 2002; McCann and Huang, 2007). Our finding that HIS1 metabolizes TE may contribute to further studies on the plant species-specific metabolism of TE.

We confirmed that the metabolism of TE by HIS1 is dependent on Fe2+ and 2OG, showing that the reaction occurs by the typical mode of 2OGD action (Wilmouth et al., 2002). Furthermore, NMR and MS analyses revealed that HIS1 catalyzes the hydroxylation of TE, resulting in the formation of ethyl 4-(cyclopropanecarbonyl)-1-hydroxy-3,5-dioxocyclohexane-1-carboxylate (TE-OH, Metabolite 1) as the primary product.

We prepared TE-OH by HIS1-mediated conversion of TE in vitro and administered the TE-OH aqueous solution in seedling growth tests. The exogenously applied TE-OH had a much weaker inhibitory effect on rice seedling growth compared with TE. However, the ability of seedlings to take up TE-OH is presently unknown. On the other hand, our results with HIS1-overexpressing rice lines indicated that the conversion of TE to TE-OH by HIS1 attenuates the inhibitory effect of TE on seedling growth, suggesting that this conversion partially protects plants from the inhibitory effect of TE on the gibberellin biosynthetic pathway. We tested two HIS1-overexpressing transgenic lines, #5 and #6. We previously showed that the expression level of HIS1 in line #6 is about twice that in line #5 on the same his1/his1 genetic background of Yamadawara and that these HIS1 expression levels are reflected by herbicide tolerance levels (Maeda et al., 2019). Similarly, we here found that the growth of line #6 was less affected by TE treatment than line #5.

Analysis of TE metabolism in the HIS1-overexpressing rice lines revealed substantial accumulation of TE-OH in the culture medium. Herbicide metabolites generated by the human cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme CYP1A1 expressed in rice were previously found to be released into culture medium from roots (Kawahigashi et al., 2003). Our results thus also indicate that the TE metabolite TE-OH is released from roots. We also detected accumulation of trinexapac, a major TE metabolite in crops (Hiemstra and de Koh, 2003), in plant tissues, with the extent of this accumulation in stem and leaf tissue of the HIS1-overexpressing lines appearing to be slightly reduced compared with that in the nontransgenic line. Given that trinexapac is thought to be largely responsible for the action of TE as a plant growth regulator, its reduced accumulation may explain the increased TE tolerance of the HIS1 transgenic lines. It is possible that the conversion of TE to trinexapac occurs efficiently before HIS1 can convert TE to TE-OH in plants. Although we have not examined the potential metabolism of trinexapac by HIS1 in vitro, the data from our in vivo analysis suggest that trinexapac is not likely a substrate of HIS1. The intrinsic activity responsible for the conversion of TE to trinexapac in plants may thus be predominant and promote TE consumption, thereby reducing the chance for the transformation of TE to TE-OH by HIS1.

CYP enzymes play pivotal roles in drug metabolism in humans (Anzenbacher and Anzenbacherová, 2001). In particular, CYP3A4 is the most abundant CYP in the liver and metabolizes drugs administered orally with a broad substrate specificity (Brown et al., 2008; Lokwani et al., 2020). CYPs have also been found to play a role in xenobiotic metabolism in plants (Werck-Reichhart et al., 2000; Siminszky, 2006; Iwakami et al., 2014; Saika et al., 2014). However, CYPs also play important roles in secondary metabolism in plants and appear to have broad substrate specificity (Mizutani and Ohta, 2010; Nelson and Werck-Reichhart, 2011). The potential catalytic promiscuity of plant CYPs is likely controlled by the formation of metabolons with other related enzymes in specific metabolic pathways such as flavone biosynthesis (Nakayama et al., 2019). In addition to CYP enzymes, 2OGD proteins also form a large enzyme superfamily in plants (Farrow and Facchini, 2014; Kawai et al., 2014). In the rice genome sequence database, 334 CYP and 114 2OGD genes have been annotated (Kawai et al., 2014). As an example of the broad substrate specificity of 2OGD enzymes, we previously showed that rice HIS1 hydroxylates at least five different bTHs and abolishes their herbicidal function (Maeda et al., 2019). The HIS1 gene is therefore a resource as a multiple herbicide resistance genes for the breeding of rice and other crops. We have now revealed that HIS1 also hydroxylates the plant growth regulator TE and thereby attenuates its biological activity. This single enzyme is thus now known to metabolize a total of six different compounds.

With regard to TE metabolism in rice, we further showed that the enzymes OsHSL2 and OsHSL4 also possess TE-metabolizing activity. However, these two HSL proteins have no bTH-inactivating activity. We also found that two wheat HSL proteins, TaHSL1 and TaHSL2, and the barley HSL protein HvHSL6A mediate TE metabolism in vitro. In the case of OsHSL4 and HvHSL6A, the TE conversion products included a derivative (Metabolite 3) that also appeared to be a hydroxylated form of TE and was not seen with other HSL proteins, suggesting that the catalytic mechanism of these enzymes might differ from that of HIS1. In addition, we unexpectedly found that OsHSL1 does not recognize TE as a substrate, with TE actually acting as a weak inhibitor of OsHSL1 activity. These results revealed that it is not possible to predict the catalytic functions of HSL enzymes on the basis of only sequence similarity. We found that the TE metabolite designated Metabolite 2 appeared not only in the HIS1 reaction but also in other HSL enzyme reactions and that its appearance was associated with the generation of Metabolites 1 or 3. However, the production of Metabolite 2 in the HIS1 reaction did not show the same time dependence as did that of Metabolite 1 (TE-OH), suggesting that the generation of Metabolite 2 is not likely attributable to the function of HIS1 or other HSL enzymes and might instead be due to conversion of Metabolite 1 or 3 by the activity of an unknown enzyme derived from the wheat germ extract used for protein synthesis.

Given that the amino acid sequences of HIS1 and OsHSL1 share the highest identity (87%) among all known HSL proteins, the small differences in structure between HIS1 and OsHSL1 must determine whether TE serves as a substrate or an inhibitor. 3D structure models of HIS1 and OsHSL1 reveal differences in the putative substrate-binding pockets of these proteins (Maeda et al., 2019). In this study, we included OsHSL2, which shows TE-metabolizing activity and generates Metabolite 1, in the construction of structure models. On the other hand, OsHSL4, which generates TE Metabolite 3, was not included in this analysis. On the basis of these structural models, we designed a series of mutant OsHSL1 proteins in which specific amino acids were replaced by the corresponding residues of HIS1, and we then tested the ability of these mutants to metabolize TE in vitro. Among the three residues examined, the most notable was Phe140 of OsHSL1, given that both HIS1 and OsHSL2 have His at this position. We, therefore, expected that the OsHSL1_F140H mutant might have acquired TE-metabolizing activity. However, none of the single mutants examined (F140H, L204F, and F298L) manifested such activity. Both double mutants containing F140H did acquire the ability to metabolize TE, and the triple mutant showed a level of activity similar to that of HIS1. The effect of the F298L mutation was unexpected because OsHSL2 also has Phe at the corresponding position. Our results thus suggest that minor structural changes induced by amino acid substitutions in the putative substrate pocket of OsHSL1 lead to marked changes in protein function. Molecular docking simulations further suggested that: (1) TE configurations in HIS1 and OsHSL2 are reasonably close to the Fe atom, the catalytic center of the 2OGD enzymes, but are in different orientations; (2) the TE configuration in OsHSL1 is not close enough to the catalytic center; and (3) the TE configuration in OsHSL1_F140H/L204F/F298L is similar to that in HIS1. The docking models thus support the biochemical data. The different orientations of the TE configurations in the models of HIS1 and OsHSL2 suggest that the manner of substrate recognition differs between the two enzymes, possibly accounting for why OsHSL2, unlike HIS1, does not possess herbicide-metabolizing activity.

Small changes to the amino acid sequence of CYPs have been found to affect substrate specificity. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms of specific CYPs have become important indicators of drug dosage appropriate for administration to individual patients. Such polymorphisms thus result in differences in drug turnover within the body and thereby influence drug efficacy (Honda et al., 2011; Ahmad et al., 2018). Our results now indicate that small sequence differences can have a substantial effect on the catalytic function of 2OGD proteins.

In conclusion, the results of this study have revealed that 2OGD proteins, like CYPs, may play an important role in xenobiotic metabolism in plants as a result of their catalytic promiscuity.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Daminozide [4-(2,2-dimethylhydrazinyl)-4-oxobutanoic acid] was obtained from Tokyo Chemical Industry (Tokyo, Japan). PR (3,5-dioxo-4-propionylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid), TE [ethyl-(3-oxido-4-cyclopropionyl-5-oxo) oxo-3-cyclohexenecarboxylate], and trinexapac [4-[cyclopropyl(hydroxy)methylidene]-3,5-dioxocyclohexane-1-carboxylic acid] were from Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical (Osaka, Japan). The plant growth regulator Primo Maxx, which contains 11.2% (w/v) TE as an active ingredient, was obtained from Syngenta Japan. 3-(2-Chloro-4-mesylbenzoyl)-bicyclo[3.2.1]octane-2,4-dione (BBC-OH) was obtained from SDS Biotech (Tokyo, Japan). TFT was also obtained from Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical.

Cell-free protein synthesis

HIS1 and OsHSL1 proteins were prepared as described previously (Maeda et al., 2019). For preparation of other HSL proteins, the nucleotide sequences of cDNAs including the protein-coding regions were optimized for cell-free protein expression in a wheat germ system and were then obtained as synthetic DNA molecules from Eurofins Genomics. These cDNAs included those for OsHSL2 (GenBank accession no. LC505696), OsHSL4 (LC589269), OsHSL5 (LC589270), OsHSL6 (LC589271), TaHSL1 (LC505700), TaHSL2 (LC505701), HvHSL1A (LC505697), HvHSL6A (LC505698), HvHSL6D (LC505699), SbHSL1 (LC505704), ZmHSL1A (LC505702), and ZmHSL1B (LC505703). Each cDNA was digested with the restriction enzymes SpeI and SalI, and the excised DNA fragment, including the open reading frame, was cloned into the corresponding sites of the pYT08 expression vector (Nozawa et al., 2011). Messenger RNAs for synthesis of each enzyme protein were prepared by in vitro transcription from the pYT08-based vectors, and the proteins were synthesized with the use of a wheat-germ cell-free system as described previously (Maeda et al., 2019).

Assay of enzyme activity

Each substrate was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide to prepare a stock solution. The activity of HIS1, OsHSL1, OsHSL2, OsHSL4, OsHSL5, OsHSL6, TaHSL1, TaHSL2, HvHSL1A, HvHSL6A, HvHSL6D, SbHSL1, ZmHSL1A, or ZmHSL1B was determined by monitoring the decrease in the amount of substrate by reversed-phase HPLC with a LaChrome Elite system (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). All solutions were incubated at 30°C for 5 min prior to mixing for the enzyme reaction. The translation mixture containing each enzyme was mixed with the substrate (final concentration of 0.3 mM), FeCl2 (0.1 mM), 2OG (0.6 mM), and HEPES-KOH (100 mM, pH 7.0). The reaction mixture (final volume of 25 µL) was then incubated at 30°C for 60 min, after which the reaction was stopped by the addition of an equal volume of methanol (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) followed by incubation on ice for 15 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 20,000g for 15 min at 4°C, and the resultant supernatant was transferred to a new 1.5-mL plastic tube and dried under vacuum. The residue was dissolved in HPLC buffer, passed through a Cosmonice Filter (W) (pore size of 0.45 μm, diameter of 4 mm; Nacalai Tesque), and injected into a Pro C18 column (length of 150 mm with an i.d. of 4.6 mm; YMC, Kyoto, Japan), which was then subjected to elution at a flow rate of 1 mL/min at 40°C with an equal mixture of 1% (v/v) acetic acid and acetonitrile. Elution was monitored by measurement of A284. As a negative control, the enzyme reaction was performed with a translation mixture for green fluorescent protein (GFP), which did not show catalytic activity toward the tested substrates. The substrate peak for the negative control reaction was considered as the total amount of substrate, and the decrease in the amount of substrate was estimated from the peak area measured for each recombinant enzyme assay. Peak area was calculated with the use of EZChrom Elite version 3.1.5aJ software (Scientific Software, Chicago, IL, USA).

Isolation of TE metabolites

The 200-mL reaction mixture for preparation of TE metabolites contained 20 mL of the translation mixture for HIS1 protein, TE (final concentration of 0.8 mM), FeCl2 (0.1 mM), ascorbate (1.2 mM), 2OG (0.9 mM), and HEPES-KOH (100 mM, pH 7.0). The reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 12 h, after which the reaction was stopped by the addition of an equal volume of methanol (Nacalai Tesque) followed by incubation at 4°C for 16 h. The mixture was then centrifuged at 20,000g for 30 min at 4°C, the resulting supernatant was mixed with deionized water in order to reduce the methanol concentration to 0.3% (v/v), and the resultant solution was subjected to column purification.

A reversed-phase octa decyl silyl (ODS) column, Mega BE-C18 (5 g, 20 mL; Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), was conditioned with 100 mL of 100% methanol and equilibrated with 50 mL of deionized water. For removal of impurities, the prepared sample was applied to the column in 50-mL batches, after which the column was washed with 20 mL of 10% (v/v) methanol and then subjected to elution with 30 mL of 50% (v/v) methanol. After confirmation that the recovered eluate contained the TE metabolites by HPLC analysis, it was transferred to a 500-mL eggplant flask, and methanol was removed with the use of a rotary vacuum evaporator in a 45°C water bath. After the addition of 100 mL of a 1:1 (vol/vol) mixture of acetonitrile and H2O, the sample was freeze-dried, and the resultant residue was dissolved in 50 mL of acetonitrile-H2O (1:1, vol/vol), transferred to a 100-mL round-bottom flask, and subjected to rotary vacuum evaporation in order to remove the acetonitrile. The resultant concentrated aqueous solution was mixed with 10 mL of 50-mM phosphoric acid, and all of the mixture was applied to a DSC-C18 (5 g/20 mL) column that had been conditioned consecutively with 20 mL of acetonitrile and 20 mL of 5 0mM phosphoric acid. The flow-through fraction was discarded, the column was washed with 20 mL of a mixture of acetonitrile and 50 mM phosphoric acid (3:7, vol/vol), and the TE metabolites were eluted with 20 mL of a 4:6 (vol/vol) mixture of acetonitrile and 50-mM phosphoric acid. The eluate was recovered in a 100-mL round-bottom flask and subsequently transferred to a 200-mL separating funnel containing 100 mL of ethyl acetate, to which was then added 5 g of NaCl and 10 mL of 50 mM phosphoric acid. The mixture was subjected to extraction by shaking for 5 min at room temperature, the resulting aqueous layer was discarded, and the organic layer was recovered with 30 mL of ethyl acetate and applied to a sodium sulfate column for dehydration. The dehydrated solution was recovered in a 300-mL round-bottom flask, and ethyl acetate was removed with a rotary vacuum evaporator in a water bath (<30°C) to obtain the final dried sample.

LC–ESI–MS

ESI–MS spectra were obtained with a Xevo G2-XS QTof MS system (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). The LC analysis shown in Figure 2A was performed with a Capcell Pak ADME column (150 mm, with an i.d. of 4.6 mm; Shiseido, Tokyo, Japan) and a mixture of acetonitrile and 0.1% (v/v) acetic acid (4:6, vol/vol) at 40°C. Elution was monitored at a wavelength of 286 nm. For ESI–MS, the mode of ionization was API-ES (positive) and the signal mode was MSE (50–1,000 m/z). Fragmentor voltage was tested with a gradient range of 20–40 V in order to detect molecular ions and fragment ions.

NMR analysis

1H-NMR spectra (in CDCl3) and 13C-NMR spectra (in CDCl3) were measured with a Bruker Ascend 400 instrument at 400 and 101 MHz, respectively.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis for HIS1 and 13 HIS1-related sequences was performed with the use of the function “build” of ETE3 version 3.0.0b32 (Huerta-Cepas et al., 2016), as implemented on GenomeNet (https://www.genome.jp/tools/ete). Alignment was performed with MAFFT version 6.861b with the default options (Katoh and Standley, 2013). The tree was constructed with FastTree version 2.1.8 according to default parameters (Price et al., 2009).

Plant growth assay

TE sensitivity was examined in test tubes (diameter, 2.5 cm; height, 15 cm) containing 10 mL of MS solid medium including TE (Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical). Rice (O. sativa cv Nipponbare) seeds were dehusked and surface-sterilized by two treatments with 4% (w/v) sodium hypochlorite for 20 min followed by three or four washes with sterilized water. The seeds were immersed in sterilized water for 2 d at 30°C, and germinated seeds were then embedded in MS solid medium composed of 0.5× MS salts, B5 vitamins, 3% (w/v) sucrose, and 0.4% (w/v) gellan gum (Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical) and containing TE and were cultured at 27°C for 7 d with 16 h of light (40 μmol m−2 s−1) daily. Growth inhibition rate was calculated based on the average length of the second leaf sheath.

Transgenic rice lines that overexpress HIS1 under the control of the 35S promoter of cauliflower mosaic virus were described previously (Maeda et al., 2019). Seeds of homozygous T3 transgenic or nontransgenic rice were dehusked, surface-sterilized, and embedded in MS solid medium containing TE (Primo Maxx). TE sensitivity was tested in test tubes (diameter, 2.5 cm; height, 15 cm) during culture at 27°C for 7 d with 16 h of light (1,300 μmol m−2 s−1) daily.

Plasmid construction for expression of mutant OsHSL1 proteins

Mutations that result in amino acid substitutions in OsHSL1 were introduced into the cDNA sequence by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis as previously described (Kanno et al., 2005). The plasmid AK241948/pFLC1, which encodes OsHSL1, was obtained from the Genebank Project of National Agriculture Research Organization (https://www.naro.affrc.go.jp/english/laboratory/ngrc/genebank_project/index.html) for use as a template. Oligonucleotide primers for the site-directed mutagenesis are listed in Supplemental Table S3. DNA fragments containing each mutated open reading frame were amplified from the pFLC1-derived plasmids by PCR with the primers HSL1-SpeF and HSL-SalR (Supplemental Table S3). The amplified fragments were digested with SpeI and SalI before cloning into the corresponding sites of pYT08, resulting in the generation of pYT08_OsHSL1_F140H, pYT08_OsHSL1_L204F, and pYT08_OsHSL1_F298L. Plasmids for the expression of OsHSL1 derivatives containing two or three amino acid substitutions were constructed as follows: pYT08_OsHSL1_F140H/L204F and pYT08_OsHSL1_F140H/F298L were prepared by site-directed mutagenesis from pYT08_OsHSL1_F140H; pYT08_OsHSL1_L204F/F298L was prepared from pYT08_OsHSL1_L204F; and pYT08_OsHSL1_F140H/L204F/F298L was prepared from pYT08_OsHSL1_F140H/L204F. Each constructed plasmid was used as a template for in vitro transcription, and the resultant mRNAs were used for cell-free protein synthesis.

Protein homology model building

Homology models for HIS1, OsHSL1, OsHSL2, and OsHSL1_F140H/L204F/F298L were generated with the use of Swiss-model (https://swissmodel.expasy.org) and with the crystal structure of JOX2 (PDB ID: 6LSV; Zhang et al., 2021) as a template. The amino acid sequence identities of HIS1, OsHSL1, OsHSL2, and the OsHSL1 mutant relative to 6LSV are 32.5% (over a coverage of 99%), 33.7% (over a coverage of 99%), 37.9% (over a coverage of 77%), and 33.1% (over a coverage of 99%), respectively. Images were generated with the use of PyMOL version 2.1.1 (Schrodinger, New York, NY, USA). Molecular docking simulations were performed with the use of the SwissDock server program (http://www.swissdock.ch) and with the generated homology models. For each docking simulation, the 20 Å × 20 Å × 20 Å region defined by the calculated position of the Fe atom as its center was searched for a binding site for TE. One of the top 10 results for each docking is shown in Figure 6A.

Accession numbers

Sequence data for this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers: LC505696 (OsHSL2), LC589269 (OsHSL4), LC589270 (OsHSL5), LC589271 (OsHSL6), LC505700 (TaHSL1), LC505701 (TaHSL2), LC505697 (HvHSL1A), LC505698 (HvHSL6A), LC505699 (HvHSL6D), LC505704 (SbHSL1), LC505702 (ZmHSL1A), and LC505703 (ZmHSL1B).

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. PR inhibits HIS1 enzyme activity in vitro.

Supplemental Figure S2. Dependence of TE metabolism by HIS1 on 2OG and Fe2 as well as MS analysis of TE.

Supplemental Figure S3. TE weakly inhibits OsHSL1 enzyme activity in vitro.

Supplemental Figure S4. In vitro TE conversion assay for various HSL proteins.

Supplemental Figure S5. MS analysis and predicted structures of TE metabolites generated by OsHSL2, TaHSL1, and TaHSL2 proteins.

Supplemental Figure S6. MS analysis of Metabolite 2 generated by HSL proteins.

Supplemental Figure S7. MS analysis of a TE metabolite generated by OsHSL4.

Supplemental Figure S8. MS analysis of a TE metabolite generated by HvHSL6A.

Supplemental Figure S9. TE conversion by OsHSL1 mutant proteins in vitro.

Supplemental Figure S10. Molecular docking simulation for HIS1 and OsHSL1.

Supplemental Table S1. NMR data for Metabolite 1 of TE.

Supplemental Table S2. Effect of HIS1 overexpression on TE sensitivity of seedling growth in a his1 rice mutant.

Supplemental Table S3. Oligonucleotide primers used in the study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S.O. and S.T. of Saitama University for their assistance with plasmid construction and plant analysis.

Funding

This work was funded in part by Research Program on Development of Innovative Technology, Bio-oriented Technology Research Advancement Institution, and National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (grant number 29009B).

Conflict of interest statement. The authors have no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

Y.To. conceived the project and together with N.T. and A.Y. designed all research; N.T., A.Y., N.S., S.H., M.S., M.O., M.K., and Y.Ta. performed the experiments; S.Y., M.O., and Y.To. analyzed the data; and Y.To. wrote the article with contributions from all other authors.

The authors responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plphys/pages/general-instructions) is: Yuzuru Tozawa (tozawa@mail.saitama-u.ac.jp).

References

- Ahmad T, Valentovic MA, Rankin GO (2018) Effects of cytochrome P450 single nucleotide polymorphisms on methadone metabolism and pharmacodynamics. Biochem Pharmacol 153: 196–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anzenbacher P, Anzenbacherová E (2001) Cytochromes P450 and metabolism of xenobiotics. Cell Mol Life Sci 58: 737–747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin CM, Liu H, McCarty LB, Bauerle WL, Toler JE (2006) Effects of trinexapac-ethyl on the salinity tolerance of two Bermuda grass cultivars. HortScience 41: 808–814 [Google Scholar]

- Brown CM, Reisfeld B, Mayeno AN (2008) Cytochromes P450: a structure-based summary of biotransformations using representative substrates. Drug Metab Rev 40: 1–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RGS, Kawaide H, Yang YY, Rademacher W, Kamiya Y (1997) Daminozide and prohexadione have similar modes of action as inhibitors of the late stages of gibberellin metabolism. Physiol Plant 101: 309–313 [Google Scholar]

- Ervin EH, Koski AJ (2001) Kentucky bluegrass growth responses to Trinexapac-Ethyl, traffic, and nitrogen. Crop Sci 41: 1871–1877 [Google Scholar]

- Fagerness MJ, Yelverton FH, Livingston DP, Rufty TW (2002) Temperature and trinexapac-ethyl effects on Bermuda grass growth, dormancy, and freezing tolerance. Crop Sci 42: 853–857 [Google Scholar]

- Farrow SC, Facchini PJ (2014) Functional diversity of 2-oxoglutarate/Fe(II)-dependent dioxygenases in plant metabolism. Frontier Plant Sci 5: 524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He P, Moran GR (2009) We two alone will sing: the two-substrate α-keto acid-dependent oxygenases. Curr Opin Chem Biol 13: 443–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegg EL, Que L (1997) The 2-His-1-carboxylate facial triad—an emerging structural motif in mononuclear non-heme iron(II) enzymes. Eur J Biochem 250: 625–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiemstra M, de Koh A (2003) Determination of trinexapac in wheat by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J Agric Food Chem 51: 5855–5860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda M, Muroi Y, Tamaki Y, Saigusa D, Suzuki N, Tomioka Y, Matsubara Y, Oda A, Hirasawa N, Hiratsuka M (2011) Functional characterization of CYP2B6 allelic variants in demethylation of antimalarial artemether. Drug Metab Dispos 39: 1860–1865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta-Cepas J, Serra F, Bork P (2016) ETE 3: reconstruction, analysis, and visualization of phylogenomic data. Mol Biol Evol 33: 1635–1638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwakami S, Endo M, Saika H, Okuno J, Nakamura N, Yokoyama M, Watanabe H, Toki S, Uchino A, Inamura T (2014) Cytochrome P450 CYP81A12 and CYP81A21 are associated with resistance to two acetolactate synthase inhibitors in Echinochloa phyllopogon. Plant Physiol 165: 618–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno T, Komatsu A, Kasai K, Dubouzet JG, Sakurai M, Ikejiri-Kanno Y, Wakasa K, Tozawa Y (2005) Structure-based in vitro engineering of the anthranilate synthase, a metabolic key enzyme in the plant Trp biosynthetic pathway. Plant Physiol 138: 2260–2268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Standley DM (2013) MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol 30: 772–780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahigashi H, Hirose S, Ohkawa H, Ohkawa Y (2003) Transgenic rice plants expressing human CYP1A1 exude herbicide metabolites from their roots. Plant Sci 165: 373–381 [Google Scholar]

- Kawai Y, Ono E, Mizutani M (2014) Evolution and diversity of the 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase superfamily in plants. Plant J 78: 328–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraehmer H, Laber B, Rosinger C, Schulz A (2014a) Herbicides as weed control agents: state of the art: I. Weed control research and safener technology: the path to modern agriculture. Plant Physiol 166: 1119–1131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraehmer H, van Almsick A, Beffa R, Dietrich F, Eckes P, Hacker E, Hain R, Strek HJ, Stuebler H, Willms L (2014b) Herbicides as weed control agents: state of the art: II. Recent achievements. Plant Physiol 166: 1132–1148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokwani DK, Sarkate AP, Karnik KS, Nikalje APG, Seijas JA (2020) Structure-based site of metabolism (SOM) prediction of ligand for CYP3A4 enzyme: comparison of Glide XP and Induced Fit Docking (IFD). Molecules 25: E1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda H, Murata K, Sakuma N, Takei S, Yamazaki A, Karim MR, Kawata M, Hirose S, Kawagishi-Kobayashi M, Taniguchi Y, et al. (2019) A rice gene that confers broad-spectrum resistance to β-triketone herbicides. Science 365: 393–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann SE, Huang B (2007) Effects of trinexapac-ethyl foliar application on creeping bentgrass responses to combined drought and heat stress. Crop Sci 47: 2121–2128 [Google Scholar]

- McCarty LB, Weinbrecht JS, Toler JE, Miller GL (2004) St. Augustine grass response to plant growth retardants. Crop Sci 44: 1323–1329 [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani M, Ohta D (2010) Diversification of P450 genes during land plant evolution. Annu Rev Plant Biol 61: 291–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama T, Takahashi S, Waki T (2019) Formation of flavonoid metabolons: functional significance of protein-protein interactions and impact on flavonoid chemodiversity. Front Plant Sci 10: 821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson D, Werck-Reichhart D (2011) A P450-centric view of plant evolution. Plant J 66: 194–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozawa A, Fujimoto R, Matsuoka H, Tsuboi T, Tozawa Y (2011) Cell-free synthesis, reconstitution, and characterization of a mitochondrial dicarboxylate-tricarboxylate carrier of Plasmodium falciparum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 414: 612–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP (2009) FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol Biol Evol 26: 1641–1650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rademacher W (2000) Growth retardants: effects on gibberellin biosynthesis and other metabolic pathways. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 51: 501–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rademacher W (2016) Chemical regulators of gibberellin status and their application in plant production. Annu Plant Rev 49: 359–403 [Google Scholar]

- Rademacher W, Bucci T (2002) New plant growth regulators: high risk investment? HortTechnology 12: 64–67 [Google Scholar]

- Saika H, Horita J, Taguchi-Shiobara F, Nonaka S, Nishizawa-Yokoi A, Iwakami S, Hori K, Matsumoto T, Tanaka T, Itoh T, et al. (2014) A novel rice cytochrome P450 gene, CYP72A31, confers tolerance to acetolactate synthase-inhibiting herbicides in rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 166: 1232–1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siminszky B (2006) Plant cytochrome P450-mediated herbicide metabolism. Phytochem Rev 5: 445–458 [Google Scholar]

- van Heerden PDR (2014) Evaluation of trinexapac-ethyl (Moddus) as a new chemical ripener for the South African sugarcane industry. Sugar Tech 16: 295–299 [Google Scholar]

- Werck-Reichhart D, Hehn A, Didierjean L (2000) Cytochromes P450 for engineering herbicide tolerance. Trends Plant Sci 5: 116–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmouth RC, Turnbull JJ, Welford RW, Clifton IJ, Prescott AG, Schofield CJ (2002) Structure and mechanism of anthocyanidin synthase from Arabidopsis thaliana. Structure 10: 93–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Krishnan S, Merewitz E, Xu J, Huang B (2016) Gibberellin-regulation and genetic variations in leaf elongation for tall fescue in association with differential gene expression controlling cell expansion. Sci Rep 6: 30258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Wang D, Elberse J, Qi L, Shi W, Peng YL, Schuurink RC, Van den Ackerveken G, Liu J (2021) Structure-guided analysis of Arabidopsis JASMONATE-INDUCED OXYGENASE (JOX) 2 reveals key residues for recognition of jasmonic acid substrate by plant JOXs. Mol Plant 14: 820–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.