Key Points

Question

How is the presence of symptoms associated with SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels in children vs adults in the community?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 555 children and adults with SARS-CoV-2 confirmed by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction, symptomatic individuals had higher SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels (as indicated by lower mean cycle threshold values) compared with asymptomatic individuals. No significant differences in RNA levels were found between asymptomatic children and asymptomatic adults or between symptomatic children and symptomatic adults.

Meaning

Regardless of age, in this community-based study, SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels were higher in symptomatic individuals.

This cross-sectional study characterizes the symptoms of pediatric COVID-19 in the community and analyzes the association of symptoms and SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels, as approximated by cycle threshold values, in children and adults.

Abstract

Importance

The association between COVID-19 symptoms and SARS-CoV-2 viral levels in children living in the community is not well understood.

Objective

To characterize symptoms of pediatric COVID-19 in the community and analyze the association between symptoms and SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels, as approximated by cycle threshold (Ct) values, in children and adults.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study used a respiratory virus surveillance platform in persons of all ages to detect community COVID-19 cases from March 23 to November 9, 2020. A population-based convenience sample of children younger than 18 years and adults in King County, Washington, who enrolled online for home self-collection of upper respiratory samples for SARS-CoV-2 testing were included.

Exposures

Detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from participant-collected samples.

Main Outcomes and Measures

RT-PCR–confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, with Ct values stratified by age and symptoms.

Results

Among 555 SARS-CoV-2–positive participants (mean [SD] age, 33.7 [20.1] years; 320 were female [57.7%]), 47 of 123 children (38.2%) were asymptomatic compared with 31 of 432 adults (7.2%). When symptomatic, fewer symptoms were reported in children compared with adults (mean [SD], 1.6 [2.0] vs 4.5 [3.1]). Symptomatic individuals had lower Ct values (which corresponded to higher viral RNA levels) than asymptomatic individuals (adjusted estimate for children, −3.0; 95% CI, −5.5 to −0.6; P = .02; adjusted estimate for adults, −2.9; 95% CI, −5.2 to −0.6; P = .01). The difference in mean Ct values was neither statistically significant between symptomatic children and symptomatic adults (adjusted estimate, −0.7; 95% CI, −2.2 to 0.9; P = .41) nor between asymptomatic children and asymptomatic adults (adjusted estimate, −0.6; 95% CI, −4.0 to 2.8; P = .74).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this community-based cross-sectional study, SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels, as determined by Ct values, were significantly higher in symptomatic individuals than in asymptomatic individuals and no significant age-related differences were found. Further research is needed to understand the role of SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels and viral transmission.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 has resulted in substantial morbidity and mortality worldwide. Early public health interventions, including the closure of schools, were implemented to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2. However, the role of children in community SARS-CoV-2 transmission remains poorly understood as most children with SARS-CoV-2 infection are asymptomatic1 or experience mild disease.2,3 There have been few community-based studies of pediatric COVID-19 cases, and thus there are limited data on the role of children in the transmission of COVID-19.4

One potential driver of SARS-CoV-2 transmissibility is respiratory tract viral load, approximated by quantification of viral RNA levels via reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) cycle threshold (Ct) values. Studies have shown a strong association between lower Ct values (higher RNA levels) and successful isolation of SARS-CoV-2 in culture.5,6,7 Early case reports showed that asymptomatic individuals had levels of detectable SARS-CoV-2 RNA comparable with symptomatic individuals,8,9,10 and this observation has been supported by a growing body of evidence from larger community-based studies in predominantly adult populations.11,12,13,14 Studies examining SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels in children, which have generally involved small sample sizes and relied on sampling associated with presentation at medical care facilities or community-based contact tracing, have shown conflicting results15,16,17,18 and comparison of community-derived pediatric and adult data has been limited.19

In this study, using data from a novel countywide respiratory virus surveillance platform, we described the association between SARS-CoV-2 Ct values and symptoms in SARS-CoV-2–positive children in King County, Washington. We also compared these findings between children and adults with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Methods

Study Platform and Setting

This is a cross-sectional population-based analysis of data collected as part of the Seattle Coronavirus Assessment Network (SCAN). SCAN launched on March 23, 2020, to evaluate the feasibility of testing individuals both with and without COVID-19–like illness via unsupervised home self-collected nasal swabs for detection of SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory pathogens.20 The network was originally established in November 2018 as the Seattle Flu Study (SFS),21 which focused on the community transmission of influenza and other respiratory viruses. SCAN was limited to residents of King County, Washington. We split the county into 16 groupings, defined roughly by the 16 public use microdata areas defined by the US Census Bureau. The proportion of individuals relative to the county population in each grouping dictated the proportion of daily test kits allotted to each public use microdata area. Individuals of all ages, whether they had any COVID-19 symptoms or not, were eligible to enroll on the study website.20 The website and study materials were translated into 11 non-English languages and translation services were available. This study was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.29 All patients who enrolled online provided written informed consent.

Data and Sample Collection

After signing an electronic consent form, all participants, or parents or guardians for participants younger than 18 years, completed an electronic questionnaire to collect data on sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, exposures, and health-related behaviors. Race and ethnicity were self-classified by participants using provided standard race and ethnic categories.22 Race and ethnicity data were collected to examine disparities between racial/ethnic groups in study participation as well as in outcomes, such as SARS-CoV-2 positivity. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap Electronic Data Capture version 10.9.2 (Vanderbilt University) hosted at the University of Washington.23,24 Within 24 hours of enrollment, sample collection kits were delivered using a private courier for contactless receipt at the participants’ homes. Samples were self-collected by participants 13 years and older via unsupervised middle turbinate (MTB) or anterior nares (AN) swabs.25 Parents or guardians performed swab collection for children younger than 13 years. Swab collection instructions were included with the swab kit (eFigure 1 in the Supplement) and were available on the study website.26,27 Swab samples were returned to the laboratory within 48 hours via private courier.

This study included participants who enrolled in SCAN from March 23 to November 9, 2020, and who collected at home a nasal swab that tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR. Repeated samples from individuals were excluded from analysis. Children were defined as participants younger than 18 years. For privacy, all adults older than 85 years were classified as aged 85 years. Symptomatic participants reported at least 1 symptom (ie, runny or stuffy nose, fever, headache, cough, fatigue, sore throat, muscle or body aches, chills, sweats, loss of smell or taste, diarrhea, eye pain, nausea or vomiting, trouble breathing, ear pain or discharge, or rash) within 7 days prior to study enrollment. Asymptomatic participants were those who reported no symptoms in this time frame. Per guidelines from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention at the time of the study, close contact was defined as an encounter in the past 2 weeks in which the individual spent at least 10 minutes within 6 feet of a person who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Laboratory Analyses

From March 23 to July 23, 2020, MTB swabs (Copan) were returned in 3-mL tubes of BD universal viral transport media (Becton, Dickinson and Company) or viral transport media (Brainbits) at room temperature, and aliquoted and stored at 4° C prior to testing. After July 23, 2020, AN swabs (US Cotton #3) were used by participants and returned in empty transport tubes. AN swabs were rehydrated and eluted in 1 mL of either phosphate-buffered saline or Tris-EDTA buffer. All samples were processed, including rehydration, within 48 hours of collection. Stability studies have shown consistent SARS-CoV-2 Ct values at 4° C and 40° C for both AN and MTB swabs up to 3 days28 and 9 days,21 respectively. Laboratory testing was performed at the Brotman Baty Institute for Precision Medicine, Seattle, Washington, and the Northwest Genomics Center, Seattle, Washington. Total nucleic acids were extracted (before October 18, 2020, MagNA Pure 96, Roche; on or after October 18, 2020, KingFisher, Thermo Fisher) and tested for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 and the human marker ribonuclease P (RNase P) using a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–compliant laboratory developed test. RNase P Ct values were used as an extraction and sample collection control. The laboratory developed test consisted of 2 unique multiplexed assays run in duplicate for a total of 4 RT-PCR reactions; each multiplex reaction included a target for SARS-CoV-2 and RNase P. One assay targeted Orf1b with FAM fluor (Life Technologies 4332079 assay #APGZJKF) and was multiplexed with an RNase P probe set with VIC or HEX fluor (Life Technologies A30064 or Integrated DNA Technologies) on a QuantStudio 6 (Applied Biosystems), and the other targeted the S gene (Life Technologies 4332079 assay #APXGVC4) and was also multiplexed with RNase P-VIC or RNase P-HEX assay. Standard curves demonstrated a linear association with mean Ct values and logarithm of SARS-CoV-2 RNA copy numbers for each primer set and from each collection method (MTB vs AN) (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). At least 3 replicates for RNase P had to be detected for a valid test result. For a positive result, 3 or more SARS-CoV-2 targets must have had a Ct value of less than 40. Most samples were also tested for the presence of 24 respiratory pathogens by TaqMan RT-PCR on the OpenArray platform (Thermo Fisher).

Statistical Analyses

Mean SARS-CoV-2 Ct values were obtained using the 2 Ct values for the Orf1b gene primer. Results were not affected by the primer used (eFigure 3 in the Supplement) but we excluded analysis by S gene because of better Orf1b sensitivity and reproducibility. Analysis by RNase P Ct values did not show evidence of confounding by age or symptom status (eFigure 4 in the Supplement). We generated descriptive statistics for all variables. Proportions of missing data were reported. Data analyses were performed using R version 4.0.5 (The R Foundation). Statistical comparisons between groups were determined using χ2 tests, Welch t test, and multiple linear regression. Two-tailed tests were used for all comparisons and statistical significance was defined as P < .05. AN swabs were used in the later portion of the study when rates of positivity in children, many of whom were asymptomatic, increased. Therefore, because swab type is a confounder of the association between age and SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels, we used multiple linear regression to adjust individual Ct values to the average swab type in the study. This ensured that our figures would show an unconfounded comparison of ages and symptom status, while preserving the mean Ct value across the sample. Although 2 different nucleic acid extraction platforms were used, multiple linear regression analysis showed that the extraction platform used did not have statistically significant or clinically meaningful associations with our results.

Results

From March 23 to November 9, 2020, 37 067 samples were tested for SARS-CoV-2 via SCAN. Overall, 673 samples (1.8%) had positive results (493 of 31 664 [1.6%] of adult samples and 180 of 5356 [3.4%] of child samples; 47 positive samples did not have age data). Of these positive samples, 180 samples (26.7%) were from children younger than 18 years and 493 (73.3%) were from adults. We excluded 118 samples: 42 that represented repeated positive testing in SCAN and 76 that were missing clinical information.

Of the 555 participants with SARS-CoV-2–positive results, 123 (22.2%) were children and 432 (77.8%) were adults (Table 1), ranging in age from 73 days to 85 years. The mean (SD) age was 33.7 (20.1) years: 7.5 (5.3) years for children and 41.2 (16.0) years for adults. Among 123 SARS-CoV-2–positive children in this study, 50 (40.7%) were younger than 5 years, 45 (36.6%) were aged 5 to 11 years, and 28 (22.8%) were aged 12 to 17 years. Of the total positive sample, 320 (57.7%) were female. Of 123 SARS-CoV-2–positive children, 64 (52.0%) were female, 55 (44.7%) were White, and 30 (24.4%) were Hispanic or Latino. The most common underlying conditions among SARS-CoV-2–positive children included seasonal allergies (9 [7.3%]) and asthma (5 [4.1%]), but most children reported no previous underlying medical conditions (106 [86.2%]). Compared with the mean King County household size of 2.4 people,30 people of all ages with SARS-CoV-2–positive results reported larger mean (SD) household sizes (3.8 [1.6]). Most children (91 [74.0%]) resided in households of 4 or more people. Most children (98 [79.7%]) had at least 1 known SARS-CoV-2–positive contact, and most contacts (84 [68.3%]) were in the same household. In contrast, only 179 of 432 SARS-CoV-2–positive adults (41.4%) reported any known positive contact.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2–Positive Children and Adults in Seattle Coronavirus Assessment Network (SCAN) From March 23 to November 9, 2020.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample | Children | Adults | |

| Total, No. | 555 | 123 | 432 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 320 (57.7) | 64 (52.0) | 256 (59.3) |

| Male | 235 (42.2) | 59 (48.0) | 176 (40.7) |

| Race/ethnicitya | |||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1 (0.2) |

| Asian | 75 (13.5) | 13 (10.6) | 62 (14.4) |

| Black or African American | 35 (6.3) | 10 (8.1) | 25 (5.8) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 11 (2.0) | 2 (1.6) | 9 (2.1) |

| White | 283 (51.0) | 55 (44.7) | 228 (52.8) |

| Otherb | 76 (13.7) | 17 (13.8) | 59 (13.7) |

| Multiple races | 42 (7.6) | 19 (15.4) | 23 (5.3) |

| Not reported | 32 (5.8) | 7 (5.7) | 25 (5.8) |

| Hispanic or Latino ethnicity | |||

| Yes | 118 (21.3) | 30 (24.4) | 88 (20.4) |

| No | 414 (74.6) | 89 (72.4) | 325 (75.2) |

| Not reported | 23 (4.1) | 4 (3.3) | 19 (4.4) |

| Age, y | |||

| 0-4 | 50 (9.0) | 50 (40.7) | NA |

| 5-11 | 45 (8.1) | 45 (36.6) | NA |

| 12-17 | 28 (5.0) | 28 (22.8) | NA |

| 18-49 | 305 (55.0) | NA | 305 (70.6) |

| 50-64 | 93 (16.7) | NA | 93 (21.5) |

| 65-85c | 34 (6.1) | NA | 34 (7.9) |

| Mean (SD) | 33.7 (20.1) | 7.5 (5.3) | 41.2 (16) |

| Comorbidity | |||

| None | 394 (71.0) | 106 (86.2) | 288 (66.7) |

| Allergy | 77 (13.8) | 9 (7.3) | 68 (15.7) |

| Asthma | 41 (7.4) | 5 (4.1) | 36 (8.3) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 9 (1.6) | 0 | 9 (2.1) |

| Cancer | 2 (0.4) | 0 | 2 (0.5) |

| Chronic lung disease, not asthma | 3 (0.5) | 0 | 3 (0.7) |

| Diabetes | 24 (4.3) | 0 | 24 (5.6) |

| Hypertension | 42 (7.5) | 1 (0.8) | 41 (9.5) |

| Unknown/not reported | 16 (2.9) | 2 (1.6) | 14 (3.2) |

| Household size (including participant) | |||

| 1 | 36 (6.5) | 0 | 33 (7.6) |

| 2 | 116 (20.9) | 21 (17.1) | 95 (22.0) |

| 3 | 83 (15.0) | 11 (8.9) | 72 (16.7) |

| 4 | 123 (22.0) | 38 (30.9) | 88 (20.4) |

| 5 | 95 (17.1) | 30 (24.4) | 65 (15.0) |

| ≥6d | 102 (18.4) | 23 (18.7) | 79 (18.3) |

| Mean (SD) | 3.8 (1.6) | 4.1 (1.4) | 3.7 (1.6) |

| SARS-CoV-2–positive close contactse | |||

| None | 69 (12.4) | 10 (8.1) | 59 (13.7) |

| Any positive contact | 277 (49.9) | 98 (79.7) | 179 (41.4) |

| Household | 225 (40.5) | 84 (68.3) | 141 (32.6) |

| Friend | 45 (8.1) | 14 (11.4) | 31 (7.2) |

| Coworker | 16 (2.9) | 0 | 16 (3.7) |

| Unsure/not reported | 209 (37.7) | 15 (12.2) | 194 (44.9) |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Race/ethnicity categories were treated as mutually exclusive groups; multiple races was defined as 2 or more of the above groups.

This included unlisted races not specified by participant.

For privacy, all adults older than 85 years were classified as aged 85 years.

For the purpose of analysis, we assumed a household size of 6 for individuals who reported 6 or more household members.

Close contact was defined as an encounter in the past 2 weeks in which the individual spent at least 10 minutes within 6 feet of a person who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

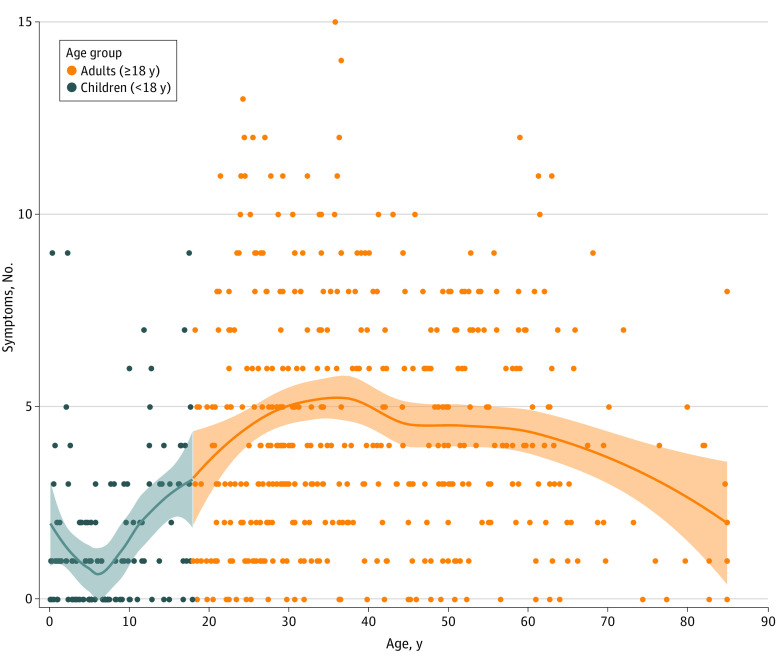

Fewer children were symptomatic compared with adults (76 of 123 children [61.8%] vs 401 of 432 adults [92.8%]; P < .001) (Table 2). When symptomatic, fewer symptoms were reported in children compared with adults (mean [SD], 1.6 [2.0] vs 4.5 [3.1]) (Figure 1). Symptomatic children reported a mean (SD) of 3.8 (3.8) days of symptoms compared with 4.9 (4.1) days in symptomatic adults. The most common signs or symptoms reported in children were runny or stuffy nose, fever, headache, and cough, while adults most frequently reported headache, cough, and fatigue (eFigure 5 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Reported Signs and Symptoms and Duration in SARS-CoV-2–Positive Children and Adults at Enrollment.

| Sign or symptoma | No (%) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children | Adults (n = 432) | Children aged ≤4 y vs children aged 5-17 y | All children vs adults | ||

| Aged ≤4 y (n = 50) | Aged 5-17 y (n = 73) | ||||

| No symptoms | 23 (46.0) | 24 (32.9) | 31 (7.2) | .20 | <.001 |

| Any symptom | 27 (54.0) | 49 (67.1) | 401 (92.8) | ||

| Runny or stuffy nose | 14 (28.0) | 22 (30.1) | 192 (47.9) | .97 | .004 |

| Fever | 11 (22.0) | 15 (20.5) | 161 (40.1) | >.99 | .001 |

| Headache | 5 (10.0) | 19 (26.0) | 247 (57.2) | .05 | <.001 |

| Cough | 12 (24.0) | 12 (16.4) | 235 (58.6) | .42 | <.001 |

| Fatigue | 5 (10.0) | 14 (19.2) | 213 (53.1) | .26 | <.001 |

| Sore throat | 4 (8.0) | 14 (19.2) | 169 (42.1) | .14 | <.001 |

| Muscle or body aches | 3 (6.0) | 10 (13.7) | 197 (49.1) | .29 | <.001 |

| Chills | 2 (4.0) | 8 (11.0) | 130 (32.4) | .29 | <.001 |

| Sweats | 2 (4.0) | 4 (5.5) | 96 (23.9) | >.99 | <.001 |

| Loss of smell or taste | 0 | 6 (8.2) | 81 (20.2) | .10 | <.001 |

| Diarrhea | 4 (8.0) | 2 (2.7) | 70 (17.5) | .37 | .002 |

| Eye pain | 2 (4.0) | 3 (4.1) | 46 (11.5) | >.99 | .04 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 0 | 4 (5.5) | 49 (12.2) | .24 | .01 |

| Trouble breathing | 1 (2.0) | 0 | 47 (11.7) | .85 | <.001 |

| Ear pain or discharge | 0 | 1 (1.4) | 23 (5.7) | >.99 | .06 |

| Rash | 0 | 0 | 3 (7.5) | NA | .80 |

| No. of symptoms, mean (SD) | 1.3 (2.0) | 1.8 (2.0) | 4.5 (3.1) | .15 | <.001 |

| Symptom duration, mean (SD), db | 4.1 (5.3) | 3.6 (2.6) | 4.9 (4.1) | .28 | .03 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Signs and symptoms reported at enrollment.

Number of days between participant-reported date of symptom onset and swab collection date. Symptom duration was limited to 10 or fewer days. Date of symptom onset was not reported by 392 participants (327 adults and 65 children).

Figure 1. Number of COVID-19 Signs and Symptoms Reported by Participants at Enrollment by Age.

The total number of signs and symptoms at enrollment are shown by age group with individual locally estimated scatterplot smoothing regression lines plotted for each age group. Data points represent SARS-CoV-2–positive individuals. Shaded areas represent 95% CIs.

Asymptomatic children were younger than symptomatic children (mean [SD] age, 6.2 [4.5] years compared with 8.3 [5.7] years; P < .001). Although there were differences in percentage symptomatic and symptoms reported between children younger than 5 years and children aged 5 to 17 years, these differences were not statistically significant. No comorbidities were reported for asymptomatic children. A higher proportion of asymptomatic children than symptomatic children reported any SARS-CoV-2–positive contact (41 of 47 [87.2%] vs 57 of 76 [75.0%]), most of whom were household contacts (36 of 47 [76.6%] vs 48 of 76 [63.2%]).

Of the 555 SARS-CoV-2–positive swabs, 487 were tested for 24 respiratory pathogens by RT-PCR. Only 3 of 108 children (2.8%) tested for other respiratory pathogens had another virus detected by RT-PCR. Rhinovirus was detected in 2 children and adenovirus in 1 child. Ten of 379 adults (2.6%) tested by respiratory pathogen RT-PCR had another virus identified, with rhinovirus predominantly detected (7 of 10); adenovirus (1 of 10), enterovirus (1 of 10), and influenza virus (1 of 10) were also detected.

MTB swabs were used by 176 participants (18 children and 158 adults) and AN swabs were used by 379 participants (105 children and 274 adults). Multiple linear regression of mean SARS-CoV-2 Ct value by age group and swab type showed that MTB swabs were associated with a 4.0-point higher mean Ct value compared with AN swabs (P < .001) (eFigure 6 in the Supplement).

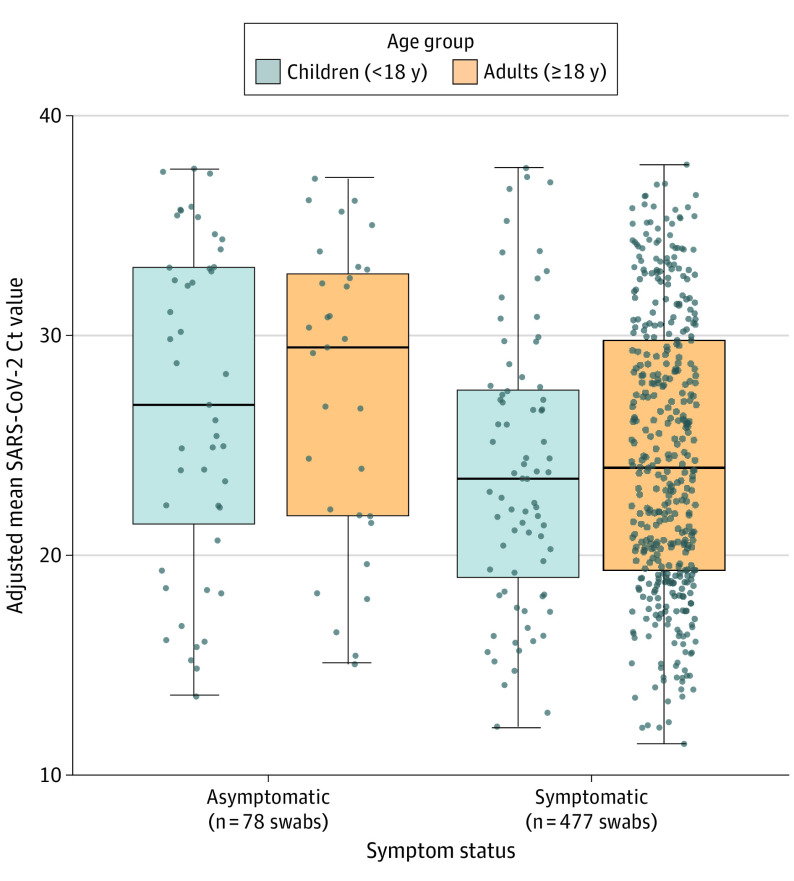

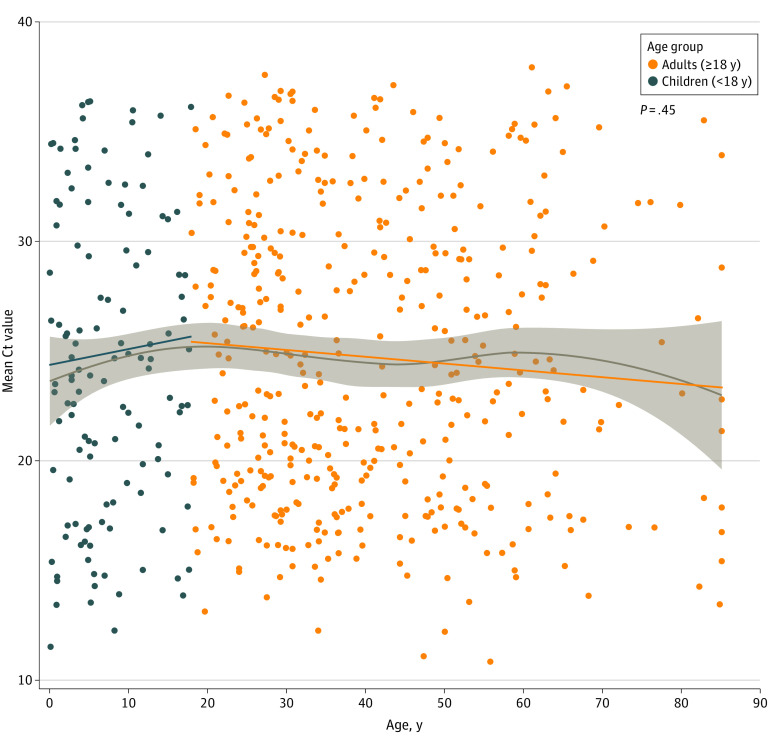

Mean SARS-CoV-2 Ct values between children and adults were not significantly different (adjusted estimate for difference in mean Ct values, 0.3; 95% CI, −1.1 to 1.6; P = .67) after adjusting for swab type (Figure 2). Subgroup analyses showed that symptomatic individuals had consistently lower Ct values than asymptomatic individuals, regardless of age, after adjusting for swab type (adjusted estimate for children, −3.0; 95% CI, −5.5 to −0.6; P = .02; adjusted estimate for adults, −2.9; 95% CI, −5.2 to −0.6; P = .01) (eTable in the Supplement). The difference in mean Ct value between symptomatic children and adults was not significant (adjusted estimate, −0.7; 95% CI, −2.2 to 0.9; P = .41). Among 399 symptomatic individuals who reported a symptom onset date, the difference in mean Ct values between symptomatic children and symptomatic adults remained not significant after adjusting for swab type and for the number of days between symptom onset and swab collection (adjusted estimate, 0.5; 95% CI, −1.0 to 2.0; P = .50). The difference in mean Ct value between asymptomatic children and adults was also not significant (adjusted estimate, −0.6; 95% CI, −4.0 to 2.8; P = .74). No evidence of interaction by age and symptom status was found. Mean SARS-CoV-2 Ct values (as a continuous variable) did not vary significantly across age, even when adjusted for swab type (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Adjusted Mean SARS-CoV-2 Orf1b Cycle Threshold (Ct) Values by Age Group, Grouped by Symptom Status.

Boxes range from the first to third quartiles. Midlines represent median values. Error bars represent the minimum and maximum values. Individual points represent SARS-CoV-2–positive individuals. There were 47 asymptomatic children, 31 asymptomatic adults, 76 symptomatic children, and 401 symptomatic adults. Ct values are adjusted for swab type.

Figure 3. Mean SARS-CoV-2 Orf1b Cycle Threshold (Ct) Values by Age.

The scatterplot depicts Ct values adjusted by swab type. The gray line represents the locally estimated scatterplot smoothing curve using unadjusted Ct values. Linear regression lines per age group (orange indicates adults; blue indicates children) are adjusted by swab type. Data points represent SARS-CoV-2–positive individuals. Shaded areas represent 95% CIs.

There was a nonsignificant association of lower mean Ct values with an increase in the number of symptoms reported (eFigure 7 in the Supplement). Longer time since symptom onset to date of swab collection was associated with higher Ct values. There was not a significant difference between children and adults in this association (eFigure 8 in the Supplement).

Discussion

This countywide community-based study of SARS-CoV-2 infection in King County, Washington, showed that symptomatic individuals had lower Ct values than those who were asymptomatic. Ct values did not differ significantly between asymptomatic children vs asymptomatic adults or in symptomatic children vs symptomatic adults. This study was unique in that participant-driven community-wide surveillance was instituted in a large metropolitan area using methods without direct participant contact and directed at persons who were not actively seeking medical care or follow-up.

Overall, children with documented SARS-CoV-2 infection in our study were younger, with 40% younger than 5 years, than in other community-based studies.17,18,19 A variety of signs and symptoms were reported by SARS-CoV-2–positive children or their caregivers, with runny nose documented in nearly half of the children, followed by fever, headache, and cough. The predominance of rhinorrhea contrasts with other studies, which have shown fever and cough to be more common symptoms.17,31,32 The variation in symptoms and lack of predictive value of specific symptoms have been suggested as reasons for failure of symptom-based testing when screening children for COVID-19.33

This study was not designed to measure the prevalence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. The high proportion of asymptomatic infection we observed in children is within the upper limit of the asymptomatic ranges of 40% to 45% estimated in other studies.34,35 The high proportion of asymptomatic infection we observed in children might be attributed to household enrollment of children following interest in study participation from adults with symptoms. The true frequency of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection might be closer to 16% to 22%, as suggested by other pediatric studies.16,32,35,36

Because we only assessed symptoms at one point before specimen collection, it is possible that we misclassified some participants who were presymptomatic (who would be expected to have low Ct values) as asymptomatic. Regardless, we were able to show a significant difference in Ct values between symptomatic and asymptomatic groups. Our findings of higher SARS-CoV-2 Ct values in asymptomatic children corroborate results from a small study of asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic SARS-CoV-2–positive children in South Korea16 and a large study of asymptomatic and symptomatic SARS-CoV-2–positive children from 9 US pediatric hospital testing programs.15 Two large community-based studies found similar SARS-CoV-2 Ct values in symptomatic and asymptomatic children.17,18 In these studies, children were tested as part of contact tracing, and both asymptomatic and symptomatic children might have had similarly low Ct values because of recent exposures to infected individuals. In contrast to early studies, which suggested that symptomatic children might have lower Ct values than symptomatic adults,37,38 we did not find a significant difference in SARS-CoV-2 Ct values between symptomatic children and symptomatic adults. As these prior studies included participants who sought medical attention, they likely involved more acutely ill children who might have had higher SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels corresponding to lower Ct values. For both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals, SARS-CoV-2 Ct values did not vary by age when compared as a continuous or categorical variable (ie, children and adults), corroborating studies that examined viral loads and age.1,19,39,40 However, the comparison of SARS-CoV-2 Ct values between children and adults depends on the proportion of symptomatic vs asymptomatic individuals in each group and might differ in other settings.

The mechanisms of how SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels might influence transmission have yet to be fully delineated. One large retrospective cohort study suggested that children and adolescents were more likely to transmit SARS-CoV-2 in households.41 In contrast, multiple studies of household infections have suggested that children are not the key drivers of SARS-CoV-2 transmission.18,42,43,44 It could be that lack of symptoms is associated with decreased viral transmission; studies have found lower relative risks of SARS-CoV-2 transmission from asymptomatic infected household members35,41,45 and close contacts.46 Another explanation is that asymptomatic infected individuals have lower levels of transmissible SARS-CoV-2 owing to their ability to rapidly clear the virus.47,48 In regards to disease acquisition, most transmission studies suggest that children might be less susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection.41,44,45,49 In contrast, a household seroprevalence study suggests that children are at equal risk as adults for SARS-CoV-2 infection.50,51 Current epidemiologic tracing methods might not be detecting asymptomatic infections or infections associated with brief windows of viral detection. Transmission studies have focused on household transmission and even those studies might have been confounded by school and daycare closures, which precluded evaluation of transmission within school or daycare settings. In the King County, Washington, region, public schools were closed for in-person learning during the study period. This may have decreased the number of SARS-CoV-2–positive children and our data may be reflective of secondary SARS-CoV-2 infections transmitted primarily from adult household members. As a result, studies completed thus far might not have fully identified the potential transmission risks by children. To confirm whether there are age-dependent factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 transmissibility, more epidemiological studies are needed.

Limitations

Our study had limitations. First, enrollment in the study relied on individuals to self-request home-collection kits. Individuals needed to be familiar with the study and to have had access to a device with internet capabilities. Therefore, while our study aimed to sample from across various demographic categories (eg, age, race/ethnicity, residence, and household income), our study findings might not be representative of the county population as a whole or completely generalize to other US counties. Second, demographic and illness-related information were self-reported and therefore subject to response bias. Although the study accepted both asymptomatic and symptomatic individuals, individual self-reporting of symptoms might have been biased by participant-perceived eligibility criteria. Third, the exact duration of symptoms prior to obtaining a swab were self-reported and not independently verified. Fourth, the number of children enrolled increased in the later part of the study when we switched to using AN swabs because of supply chain disruptions. Because AN swabs had higher yield of viral RNA compared with MTB swabs, likely because of increased comfort and ease of swabbing, we adjusted for the different types of swabs in our analysis. Fifth, this study relied on Ct values from semiquantitative RT-PCRs as proxies for viral RNA levels; more studies using quantitative RT-PCRs to generate direct viral RNA levels are needed. Sixth, the cross-sectional design of this study in addition to brief delays between symptom reporting and swab collection might have led to misclassification of asymptomatic and presymptomatic individuals at the time of sample collection. Characteristics, including Ct values, might differ between these 2 groups.

Conclusions

In this community-based cross-sectional study, SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels, as determined by RT-PCR Cts, were significantly higher in symptomatic individuals than in asymptomatic individuals. There were no significant differences in RNA levels in asymptomatic children vs asymptomatic adults or in symptomatic children vs symptomatic adults. Further research is needed to understand the role of SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels in transmission among children and adults.

eTable 1. Statistical results table of adjusted and unadjusted differences in mean SARS-CoV-2 Orf1b Ct values by various subgroup comparisons

eFigure 1. Standard curves for SARS-CoV-2 by collection/swab type and for Orf1b versus S gene primers

eFigure 2. Comparison of mean SARS-CoV-2 Ct values by primer

eFigure 3. Adjusted mean RNase P Ct value by age and symptom status

eFigure 4. Heatmap of reported number and types of COVID-19 signs and symptoms reported by participants at enrollment stratified by age group

eFigure 5. Mean SARS-CoV-2 Orf1b Ct values by swab type

eFigure 6. Mean SARS-CoV-2 Orf1b Ct value by number of reported signs and symptoms at enrollment and age groups

eFigure 7. Unadjusted mean SARS-CoV-2 Orf1b Ct values by duration of signs and symptoms and age group

References

- 1.He J, Guo Y, Mao R, Zhang J. Proportion of asymptomatic coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2021;93(2):820-830. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among children in China. Pediatrics. 2020;145(6):e20200702. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ludvigsson JF. Systematic review of COVID-19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109(6):1088-1095. doi: 10.1111/apa.15270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shane AL, Sato AI, Kao C, et al. A pediatric infectious diseases perspective of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in children. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2020;9(5):596-608. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piaa099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wölfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581(7809):465-469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bullard J, Dust K, Funk D, et al. Predicting infectious severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 from diagnostic samples. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(10):2663-2666. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.L’Huillier AG, Torriani G, Pigny F, Kaiser L, Eckerle I. Culture-competent SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharynx of symptomatic neonates, children, and adolescents. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(10):2494-2497. doi: 10.3201/eid2610.202403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singanayagam A, Patel M, Charlett A, et al. Duration of infectiousness and correlation with RT-PCR cycle threshold values in cases of COVID-19, England, January to May 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(32). doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.32.2001483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arons MM, Hatfield KM, Reddy SC, et al. ; Public Health–Seattle and King County and CDC COVID-19 Investigation Team . Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections and transmission in a skilled nursing facility. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22):2081-2090. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(12):1177-1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lavezzo E, Franchin E, Ciavarella C, et al. ; Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team; Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team . Suppression of a SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in the Italian municipality of Vo’. Nature. 2020;584(7821):425-429. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2488-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee S, Kim T, Lee E, et al. Clinical course and molecular viral shedding among asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection in a community treatment center in the Republic of Korea. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(11):1447-1452. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cereda D, Tirani M, Rovida F, et al. The early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy. arXiv. Preprint posted online March 2020. https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2020arXiv200309320C

- 14.Salvatore PP, Dawson P, Wadhwa A, et al. Epidemiological correlates of PCR cycle threshold values in the detection of SARS-CoV-2. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;ciaa1469. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kociolek LK, Muller WJ, Yee R, et al. Comparison of upper respiratory viral load distributions in asymptomatic and symptomatic children diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection in pediatric hospital testing programs. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;59(1):e02593-20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02593-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han MS, Seong MW, Kim N, et al. Viral RNA load in mildly symptomatic and asymptomatic children with COVID-19, Seoul, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(10):2497-2499. doi: 10.3201/eid2610.202449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hurst JH, Heston SM, Chambers HN, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infections among children in the Biospecimens from Respiratory Virus-Exposed Kids (BRAVE Kids) study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;ciaa1693. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maltezou HC, Magaziotou I, Dedoukou X, et al. ; Greek Study Group on SARS-CoV-2 Infections in Children . Children and adolescents with SARS-CoV-2 infection: epidemiology, clinical course and viral loads. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(12):e388-e392. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madera S, Crawford E, Langelier C, et al. Nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 viral loads in young children do not differ significantly from those in older children and adults. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):3044. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81934-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greater Seattle Coronavirus Assessment Network Study . Helping researchers and public health leaders track the spread of coronavirus. Accessed December 22, 2020. http://www.scanpublichealth.org

- 21.Chu HY, Englund JA, Starita LM, et al. ; Seattle Flu Study Investigators . Early detection of COVID-19 through a citywide pandemic surveillance platform. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(2):185-187. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2008646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. Office of Management and Budget. Accessed May 26, 2021. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/omb/fedreg_1997standards

- 23.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. ; REDCap Consortium . The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCulloch DJ, Kim AE, Wilcox NC, et al. Comparison of unsupervised home self-collected midnasal swabs with clinician-collected nasopharyngeal swabs for detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e2016382. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.16382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim AE, Brandstetter E, Wilcox N, et al. Evaluating specimen quality and results from a community-wide, home-based respiratory surveillance study. J Clin Microbiol. 2021;59(5):e02934-20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02934-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greater Seattle Coronavirus Assessment Network . How to use a SCAN kit. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://scanpublichealth.org/how-to-use-a-scan-kit

- 28.Padgett LR, Kennington LA, Ahls CL, et al. Polyester nasal swabs collected in a dry tube are a robust and inexpensive, minimal self-collection kit for SARS-CoV-2 testing. PLoS One. 2021;16(4):e0245423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573-577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Census Bureau . American community survey 1-year estimates. Accessed May 1, 2021. http://censusreporter.org/profiles/05000US53033-king-county-wa/

- 32.CDC COVID-19 Response Team . Coronavirus disease 2019 in children—United States, February 12-April 2, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(14):422-426. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6914e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Assaker R, Colas AE, Julien-Marsollier F, et al. Presenting symptoms of COVID-19 in children: a meta-analysis of published studies. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125(3):e330-e332. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poline J, Gaschignard J, Leblanc C, et al. Systematic SARS-CoV-2 screening at hospital admission in children: a French prospective multicenter study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;ciaa1044. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oran DP, Topol EJ. Prevalence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(5):362-367. doi: 10.7326/M20-3012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Byambasuren O, Cardona M, Bell K, Clark J, McLaws M-L, Glasziou P. Estimating the extent of asymptomatic COVID-19 and its potential for community transmission: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMMI. 2020;5(4):223-234. doi: 10.3138/jammi-2020-0030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoang A, Chorath K, Moreira A, et al. COVID-19 in 7780 pediatric patients: a systematic review. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;24:100433. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heald-Sargent T, Muller WJ, Zheng X, Rippe J, Patel AB, Kociolek LK. Age-related differences in nasopharyngeal severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) levels in patients with mild to moderate coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(9):902-903. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yonker LM, Neilan AM, Bartsch Y, et al. Pediatric severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): clinical presentation, infectivity, and immune responses. J Pediatr. 2020;227:45-52.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.08.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baggio S, L’Huillier AG, Yerly S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in the upper respiratory tract of children and adults with early acute COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;ciaa1157. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones TC, Mühlemann B, Veith T, et al. An analysis of SARS-CoV-2 viral load by patient age. medRxiv. Preprint posted online June 9, 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.06.08.20125484 [DOI]

- 42.Li F, Li Y-Y, Liu M-J, et al. Household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and risk factors for susceptibility and infectivity in Wuhan: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(5):617-628. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30981-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li X, Xu W, Dozier M, He Y, Kirolos A, Theodoratou E; Usher Network for COVID-19 Evidence Reviews (UNCOVER) . The role of children in transmission of SARS-CoV-2: a rapid review. J Glob Health. 2020;10(1):011101. doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.011101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee B, Raszka WV Jr. COVID-19 transmission and children: the child is not to blame. Pediatrics. 2020;146(2):e2020004879. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-004879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu Y, Bloxham CJ, Hulme KD, et al. A meta-analysis on the role of children in SARS-CoV-2 in household transmission clusters. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;ciaa1825. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Madewell ZJ, Yang Y, Longini IM Jr, Halloran ME, Dean NE. Household transmission of SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2031756. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.31756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sayampanathan AA, Heng CS, Pin PH, Pang J, Leong TY, Lee VJ. Infectivity of asymptomatic versus symptomatic COVID-19. Lancet. 2021;397(10269):93-94. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32651-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kissler SM, Fauver JR, Mack C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral dynamics in acute infections. medRxiv. Preprint posted online December 1, 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.10.21.20217042 [DOI]

- 49.Cevik M, Tate M, Lloyd O, Maraolo AE, Schafers J, Ho A. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV viral load dynamics, duration of viral shedding, and infectiousness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Microbe. 2021;2(1):e13-e22. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30172-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Viner RM, Mytton OT, Bonell C, et al. Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection among children and adolescents compared with adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(2):143-156. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.4573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brotons P, Launes C, Buetas E, et al. Susceptibility to Sars-COV-2 infection among children and adults: a seroprevalence study of family households in the Barcelona Metropolitan Region, Spain. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;ciaa1721. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lewis NM, Chu VT, Ye D, et al. Household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;ciaa1166. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Statistical results table of adjusted and unadjusted differences in mean SARS-CoV-2 Orf1b Ct values by various subgroup comparisons

eFigure 1. Standard curves for SARS-CoV-2 by collection/swab type and for Orf1b versus S gene primers

eFigure 2. Comparison of mean SARS-CoV-2 Ct values by primer

eFigure 3. Adjusted mean RNase P Ct value by age and symptom status

eFigure 4. Heatmap of reported number and types of COVID-19 signs and symptoms reported by participants at enrollment stratified by age group

eFigure 5. Mean SARS-CoV-2 Orf1b Ct values by swab type

eFigure 6. Mean SARS-CoV-2 Orf1b Ct value by number of reported signs and symptoms at enrollment and age groups

eFigure 7. Unadjusted mean SARS-CoV-2 Orf1b Ct values by duration of signs and symptoms and age group