Abstract

The frequency of cooking at home has not been assessed globally. Data from the Gallup World Poll in 2018/2019 wave (N = 145,417) were collected in 142 countries using telephone and face to face interviews. We describe differences in frequency of ‘scratch’ cooking lunch and dinner across the globe by gender. Poisson regression was used to assess predictors of cooking frequency. Associations between disparities in cooking frequency (at the country level) between men and women with perceptions of subjective well-being were assessed using linear regression. Across the globe, cooking frequency varied considerably; dinner was cooked more frequently than lunch; and, women (median frequency 5 meals/week) cooked both meals more frequently than men (median frequency 0 meals/week). At the country level, greater gender disparities in cooking frequency are associated with lower Positive Experience Index scores (−0.021, p = 0.009). Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the frequency with which men and women cook meals varied considerably between nations; and, women cooked more frequently than men worldwide. The pandemic, and related ‘stay at home’ directives have dramatically reshaped the world, and it will be important to monitor changes in the ways and frequency with which people around the world cook and eat; and, how those changes relate to dietary patterns and health outcomes on a national, regional and global level.

Keywords: Cooking frequency, Gallup world poll, Survey, Gender, Disparities

1. Introduction

The dual burdens of poor diet quality and high rates of diet related diseases such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension are among the largest public health challenges currently facing the world today (Swinburn, Sacks, & Hall, 2011). In addition, in many countries (both high- and low -income), food insecurity and malnutrition also remain serious public health challenges (Headey, 2013; Jones, 2017). In response, the field of public health has begun to focus on cooking at home, as a potentially important health behavior that has been associated with better diet quality (Mills, Susanna, et al., 2017b; Wolfson & Bleich, 2015; Wolfson, Leung, & Richardson, 2020), improved food security (Engler-Stringer, 2011), and better health outcomes (Zong, Eisenberg, Hu, & Sun, 2016). As the food system changes and becomes more globally connected and “Westernized” (Popkin, 2017), it is important to understand differences in cooking frequency in countries across the globe. However, to date, no survey has measured cooking frequency using a single measure of ‘scratch’ cooking with whole ingredients allowing for direct comparisons across national boundaries.

The public health focus on cooking comes as social distancing in response to COVID-19 requires people to cook most, if not all, meals at home, at least for the short term. Prior to the pandemic, national surveys reported decreased time spent cooking than in the past (Smith, Ng, & Popkin, 2013), declining cooking skills and confidence (Lang & Caraher, 2001), and perceptions that in many places cooking practices have shifted over time as people rely more on processed and “away from home” foods that do not require cooking (Engler-Stringer, 2010; McGowan et al., 2015). Cooking at home is seen as a solution to high consumption of fast food and ultra-processed foods that dominate the “Western” diet which have been shown to be strongly associated with poor diet quality, obesity, and other diet related diseases (Popkin, 2015). In developing countries, a “nutrition transition” is taking place in which many ultra-processed Western foods are becoming increasingly available, bringing with them associated diet-related health problems (Malik, Willett, & Hu, 2013; Popkin, Adair, & Ng, 2012). The way in which this transition will change cooking practices and cultural expectations around food and cooking is not known, though existing evidence indicates that changes will occur (Popkin, 2015; Popkin et al., 2012).

Historically, cooking meals at home has been the responsibility of women, and largely remains so today (Bowen, Brenton, & Elliott, 2019; Shapiro, 2004; Trubek, 2017). However, due to other societal changes (e.g. urbanization, women entering the workforce, changing gender roles re: work and household tasks), the division of household labor, including cooking meals, is shifting in some places (Bowers, 2000). For example, in the US, while women still cook more than men, men spend more time cooking now than before (Taillie, 2018). Pre-pandemic cooking frequency around the world, and the degree to which cooking frequency differs by gender and how it is associated with other socio-demographic factors are investigated in this paper. Using a newly created survey instrument, the “Cooking Frequency Questionnaire” (CFQ), which includes a definition of what kind of cooking should be “counted” (thereby focusing on “scratch cooking” and addressing a limitation of other cooking measures, as cooking is perceived very differently across multiple studies) (Wolfson, Bleich, Clegg Smith, & Frattaroli, 2016a; Wolfson, Smith, Frattaroli, & Bleich, 2016b), we compare cooking frequency in 142 countries around the world prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. In addition, we investigate how disparities in cooking frequency (at the country level) between men and women are associated with perceptions of subjective well-being. We hypothesized that women would cook more than men, particularly in less developed countries, and that greater disparities in cooking frequency (by women vs men) would be associated with lower subjective well-being. We consider this an important baseline measure of global frequencies of cooking pre-Covid-19 pandemic by gender as cooking behavior and work life and gender roles will likely be impacted by the pandemic.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data

Data come from The Gallup World Poll (GWP) (Gallup, 2019). The GWP began in 2005 and has fielded a cross-sectional survey every year in more than 140 countries around the world. More information about the GWP are available elsewhere (Gallup, 2019). Briefly, in World Poll countries, the GWP surveys residents using probability-based sampling methods. The samples are representative of the civilian, non-institutionalized national population, aged 15 and older in the vast majority of countries. Exceptions to national coverage include unsafe areas, very remote locations and low human-density areas. Typically, the sample size is approximately 1000 adults in most countries, while in the most populous ones, such as China, India and Russia, Gallup uses sample sizes of at least 2000. The sampling of respondents and countries represents more than 99% of the global population on any given year. Interviews are conducted in person, by trained interviewers in each country by face-to-face interviews or telephone interviews. Questions are read aloud to participants in their native language (the survey is translated into 144 different languages) and responses are recorded by the interviewers.

For the present analysis, we use data from the 2018 wave of data collection to take advantage of a novel set of questions about cooking frequency in the CFQ (See Appendix A) that was added to the GWP that year. The analytic sample included all 142 countries, and all adults with complete information for the cooking frequency, subjective well-being, and demographic variables. Exclusion criteria for sampling regions in specific countries included security concerns, sparsely populated areas, and lack of transportation-a complete list is detailed in the Supplemental Materials (Appendix B). The final analytic sample included 145,417 individuals from 142 countries.

2.2. Measures

Cooking frequency was based on two questions from the CFQ asking about individual (rather than household) frequency of cooking lunch and dinner. The text of the question was, “Thinking about the past 7 days, on how many of those days did YOU, personally, cook [lunch or dinner] at your home?” Prior to asking these questions, we defined what we meant by cooking by having the interviewer read the following to the participant: “By 'cooking at home’ I mean a meal prepared AT HOME from ingredients such as vegetables, meats, grains, or other ingredients. Please do not think about pre-made foods or leftovers that you reheat.” Responses could range from 0 to 7 and were recorded separately for lunch and dinner.

We measured subjective well-being based on the Life Evaluation, and Positive and Negative Experience Indices. These questions are based on validated measures(Gallup, 2019), are fielded in all waves of the GWP, and have been used previously to compare subjective well-being across countries (Frongillo, Nguyen, Smith, & Coleman-Jensen, 2017; Jones, 2017; Steptoe, Deaton, & Stone, 2015). In short, life evaluation measures how people think about their life, and the positive and negative experience indices measure how people experience daily life.

Specifically, Life Evaluation is based on the question “Please imagine a ladder, with steps numbered from 0 at the bottom to 10 at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time?“.

The Positive and Negative Experience Indices are measures of respondents' experienced daily life the day before the survey and each include five questions (described in detail elsewhere) (Gallup Inc and Gallup, 2018). Positive and Negative Index scores are calculated at the individual record level. For each individual the following procedure applies: Each five items for positive/negative experiences are scored as a “1 (Yes)” and all other answers (including don't know and refused) are scored as a “0.” The final positive/negative index are the mean of each set of items (five items for the positive index and five items for the negative index), multiplied by 100, creating a final score ranging from 0 to 100. The Cronbach's alpha of life evaluation, positive experience index, and negative experience index are high between 0.80 and 0.91 aggregated at country level (Gallup, 2019).

Individual level covariates included gender (men, women), age (≤20 years, 21–40 years, 41–60 years, 61–80 years, ≥81 years), education (elementary, secondary, tertiary), household income (poorest 20%, second 20%, middle 20%, fourth 20%, richest 20% (calculated by GWP staff based on self-reported income)), religiosity (secular/non-religious, Christian, Islamic, Hindu, Buddhist, Jewish), marital status (single/never been married, married, separated, divorced, widowed, domestic partner (e.g. living with a partner)), employment status (employed, employed for self, part-time and doesn't want full-time, part-time but wants full-time, unemployed, out of the work force), access to food (not enough money for food, enough money for food), health problems (yes, no), living environment (rural or on a farm, small town or village, large city, suburb or a large city), and region (European Union (EU) members, Non-EU European, Commonwealth of independent states, Australia-New Zealand, Southeast Asia, South Asia, East Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, Northern America, Middle East/North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa). The United Kingdom was treated as an EU member as that was its status at the time of data collection.

We created a country level measure of disparity between men and women in cooking frequency for lunch/dinner combined. To do so, we summed the frequency of cooking lunch and dinner for each individual, then calculated the national average of cooking frequency for women and subtracted the national average of cooking for men in each country. For example, in Denmark, Women: 7.85 times/week; Men: 6.16 times/week. So, the disparity for Denmark is 7.85–6.16 = 1.69). We then calculated the mean score and standard deviation across all countries (n = 142 countries), and calculated the Z score (x - mean score/standard deviation), which we define as the value for the gender disparity score in cooking frequency. The larger the value of the gender disparity score, the wider the gap in cooking frequency between men and women.

Country level covariates, to account for factors that might also influence Life Evaluation and Positive/Negative Experience indices, included the log Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita, Healthy life expectancy at birth, and measures of generosity, perception of corruption, freedom to make life choices, and social support (Gallup, 2019). Generosity is based on taking the residual of regressing the national average of GWP responses to the question “Have you donated money to a charity in the past month?” on GDP per capita (Gallup, 2019). Perception of corruption is the average of binary answers to two GWP questions: “Is corruption widespread throughout the government or not?” and “Is corruption widespread within businesses or not?” Where data for government corruption are missing, the perception of business corruption is used as the overall corruption-perception measure (Gallup, 2019). Freedom to make life choices is the national average of binary responses to the GWP question “Are you satisfied or dissatisfied with your freedom to choose what you do with your life?” (Steptoe et al., 2015) Finally, social support is the national average of the binary responses (either 0 or 1) to the question “If you were in trouble, do you have relatives or friends you can count on to help you whenever you need them, or not?” (Gallup, 2019).

2.3. Analysis

First, we conducted descriptive analyses of demographic factors associated with frequency of cooking lunch and dinner overall and in each region (the EU members, Non-EU European, Commonwealth of Independent States, Australia-New Zealand, Southeast Asia, South Asia, East Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, Northern America, Middle East and North Africa, and Sub-Saharan Africa). Next, we describe unadjusted frequency of cooking lunch, dinner, and lunch/dinner combined in each country, overall and stratified by gender. We then performed a linear regression analysis to examine the relationship between cooking frequency and individual- and country-level covariates. Finally, we describe gender disparities in cooking frequency in each country and performed regression analysis of country-level cooking disparities to examine whether gender disparity in cooking frequency at country level is associated with national subjective well-being. All analyses were conducted in 2019 and 2020 using SPSS, version 26. For all analyses, data were weighted by individual-level sampling weights provided by GWP to ensure nationally representative samples in each country.

3. Results

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the study sample overall and by median frequency of cooking lunch and dinner over the prior week. Overall, the sample included 145,417 individuals whose median frequency of cooking lunch was 2 times/week and median frequency of cooking dinner was 2 times/week (the range for both was 0–7 meals). Across all demographic categories, people cooked dinner more frequently than lunch. However, these overall estimates mask important differences across different regions in the world (for more detail see the Supplemental Materials Tables S1 and S2). Despite differences in how frequently each meal was cooked, across all regions dinner was cooked more frequently than lunch, and women cooked both meals more frequently than men.

Table 1.

Global characteristics by frequency of cooking lunch and dinner over the past 7 days, prior to Covid-19 ‘stay at home orders’.

| Overall |

Lunch |

Dinner |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Median [IQR] | Median [IQR] | |

| Total | 145417 (100%) | 2 [0, 7] | 2 [0, 7] |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 71458 (49%) | 0 [0, 3] | 0 [0, 3] |

| Female | 73960 (51%) | 4 [1, 7] | 5 [2, 7] |

| Age | |||

| Under 20 | 21682 (15%) | 0 [0, 3] | 1 [0, 4] |

| 21–40 | 61164 (42%) | 2 [0, 6] | 3 [0, 7] |

| 41–60 | 40173 (28%) | 2 [0, 7] | 3 [0, 7] |

| 61–80 | 19756 (14%) | 3 [0, 7] | 3 [0, 7] |

| Over 81 | 2637 (2%) | 3 [0, 7] | 2 [0, 7] |

| Education | |||

| Elementary | 54296 (38%) | 2 [0, 7] | 3 [0, 7] |

| Secondary | 70604 (49%) | 2 [0, 6] | 2 [0, 6] |

| Tertiary | 19519 (13%) | 2 [0, 5] | 2 [0, 5] |

| Marital Status | |||

| Single/Never been married | 46332 (32%) | 1 [0, 4] | 1 [0, 4] |

| Married | 74209 (51%) | 2 [0, 7] | 3 [0, 7] |

| Separated | 2815 (2%) | 3 [0, 7] | 4 [0, 7] |

| Divorced | 4466 (3%) | 3 [0, 7] | 4 [1, 7] |

| Widowed | 8010 (6%) | 5 [0, 7] | 5 [0, 7] |

| Domestic partner | 9210 (6%) | 3 [0, 7] | 3 [0, 7] |

| Children | |||

| Yes | 80391 (55%) | 2 [0, 7] | 2 [0, 7] |

| No | 64735 (45%) | 2 [0, 7] | 3 [0, 7] |

| Income | |||

| Poorest20% | 28335 (20%) | 2 [0, 7] | 3 [0, 7] |

| Second20% | 28564 (20%) | 2 [0, 7] | 2 [0, 7] |

| Middle20% | 28602 (20%) | 2 [0, 7] | 3 [0, 7] |

| Fourth20% | 28651 (20%) | 2 [0, 6] | 2 [0, 7] |

| Richest20% | 28654 (20%) | 2 [0, 5] | 2 [0, 6] |

| Employment Status | |||

| Employer | 39129 (27%) | 1 [0, 4] | 2 [0, 5] |

| Employed for self | 18836 (13%) | 1 [0, 6] | 2 [0, 7] |

| Part-time not want full-time | 11104 (8%) | 3 [0, 7] | 3 [0, 7] |

| Unemployed | 9704 (7%) | 2 [0, 7] | 2 [0, 7] |

| Part-time want full-time | 13399 (9%) | 2 [0, 6] | 3 [0, 7] |

| Out of work force | 53246 (37%) | 3 [0, 7] | 3 [0, 7] |

| Access to Food | |||

| No | 53573 (37%) | 2 [0, 7] | 3 [0, 7] |

| Yes | 90779 (62%) | 2 [0, 6] | 2 [0, 6] |

| Health Problems | |||

| Yes | 37289 (26%) | 3 [0, 7] | 3 [0, 7] |

| No | 107387 (74%) | 2 [0, 6] | 2 [0, 7] |

| Living Environment | |||

| A rural area or on a farm | 40641 (28%) | 2 [0, 7] | 3 [0, 7] |

| A small town or village | 46119 (32%) | 2 [0, 7] | 3 [0, 7] |

| A large city | 41990 (29%) | 2 [0, 6] | 2 [0, 6] |

| A suburb of a large city | 16295 (11%) | 2 [0, 5] | 3 [0, 6] |

| Religion | |||

| Christian | 71453 (49%) | 3 [0, 7] | 3 [0, 7] |

| Islam | 39009 (27%) | 1 [0, 5] | 1 [0, 6] |

| Hinduism | 4234 (3%) | 1 [0, 7] | 2 [0, 7] |

| Buddhism | 6666 (5%) | 2 [0, 7] | 3 [0, 7] |

| Judaism | 834 (1%) | 1 [0, 3] | 2 [0, 4] |

| Secular/Non-religious | 10863 (8%) | 2 [0, 5] | 3 [0, 6] |

| Region | |||

| European Unione (EU) | 27779 (19%) | 2 [0, 6] | 3 [0, 6] |

| Non-EU European | 8900 (6%) | 2 [0, 7] | 2 [0, 7] |

| Commonwealth of Independent States | 12748 (9%) | 2 [0, 7] | 3 [0, 7] |

| Australia-New Zealand | 1996 (1%) | 2 [0, 5] | 4 [1, 6] |

| Southeast Asia | 8905 (6%) | 2 [0, 7] | 3 [0, 7] |

| South Asia | 8049 (6%) | 0 [0, 7] | 1 [0, 7] |

| East Asia | 7600 (5%) | 2 [0, 7] | 3 [0, 7] |

| Latina America and the Caribbean | 18366 (13%) | 3 [0, 7] | 2 [0, 7] |

| Northern America | 2005 (1%) | 3 [0, 5] | 3 [1, 5] |

| Middle East and North Africa | 15470 (11%) | 0 [0, 4] | 0 [0, 4] |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 33598 (23%) | 2 [0, 5] | 2 [0, 7] |

Note: Median cooking frequency per week (0–7).

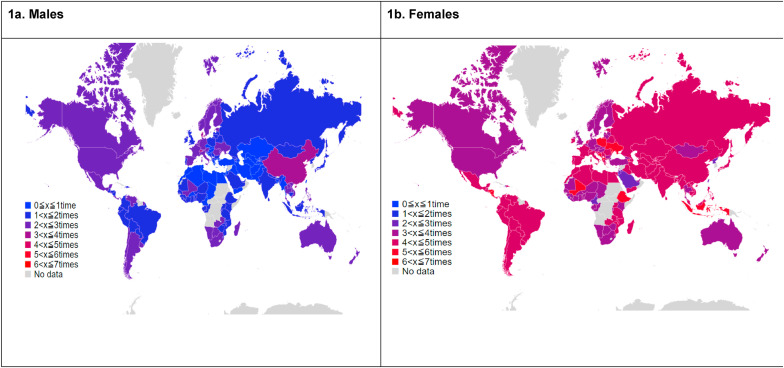

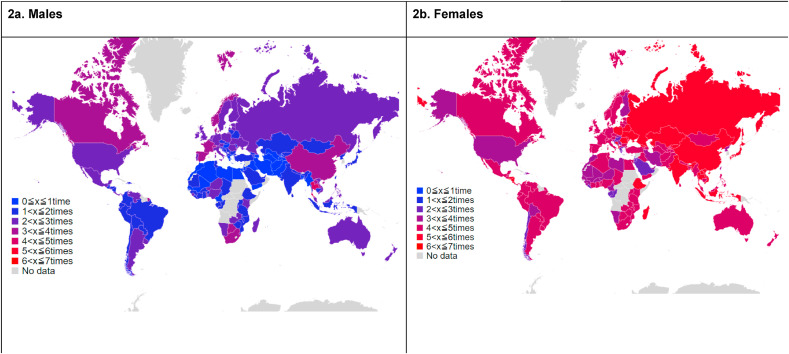

Fig. 1 shows the frequency (median times/week) of cooking lunch in countries around the world stratified by gender. In the majority of countries across the world men cook lunch very infrequently, with the highest frequency in China (4 times/week). Women cook lunch more frequently with little variation in frequently across regions. Fig. 2 displays the frequency of cooking dinner (median times/week) in countries around the world stratified by gender. Again, women cook dinner more frequently than men in all countries, but there is more variation in frequency of cooking dinner among both men and women across the globe. Additional maps showing frequency of cooking lunch/dinner combined, and overall frequency of cooking lunch, dinner, and lunch/dinner combined are available in Supplemental Materials Figures S1 and S2 and data underlying the maps is available in Supplemental Materials Table S3

Fig. 1.

Frequency of cooking lunch over the past week (7 days) around the world, by gender.

Note: Cooking frequency is the median times per week (0–7).

Fig. 2.

Frequency of cooking dinner over the past week (7 days) around the world, by gender.

Note: Cooking frequency is the median times per week (0–7).

Table 2 presents the results from poisson regression analyses regressing frequency of cooking lunch and dinner combined (0–14 times/week) on individual- and country-level covariates. Adjusted for all covariates, compared to males, females cooked lunch/dinner 0.902 more times/week (p < 0.001). The magnitude of the effect for gender was ≥3 times greater than the magnitude of effect for all other variables included in the model. Compared to individuals <20 years old, age was also associated with more frequent cooking (p < 0.001 for all age groups). Individuals with higher education cooked less frequently than those with an elementary level education (p < 0.001). Higher income, having enough money for food, and living in a non-rural area were associated with less frequent cooking at home (p values < 0.001) whereas having children in the home, having health problems and being either married, separated, divorced, widowed or having a domestic partner (compared to being single or never married) were associated with more frequent cooking at home (p values < 0.001). Supplemental Materials Tables S4a and S4b show the poisson model results for cooking lunch and dinner separately.

Table 2.

Associations between demographic and societal variables and cooking frequency of lunch and dinner over the past 7 days.

| β | 95% Wald CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | reference | – | – |

| Female | 0.902 | [0.897, 0.908] | <0.001 |

| Age | |||

| Under 20 | reference | – | – |

| 21–40 | 0.289 | [0.280, 0.298] | <0.001 |

| 41–60 | 0.291 | [0.282, 0.301] | <0.001 |

| 61–80 | 0.235 | [0.224, 0.247] | <0.001 |

| Over 81 | 0.172 | [0.153, 0.191] | <0.001 |

| Education | |||

| Elementary | reference | – | – |

| Secondary | −0.017 | [-0.023, −0.012] | <0.001 |

| Tertiary | −0.079 | [-0.088, −0.071] | <0.001 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Single/Never been married | reference | – | – |

| Married | 0.234 | [0.227, 0.241] | <0.001 |

| Separated | 0.241 | [0.225, 0.257] | <0.001 |

| Divorced | 0.301 | [0.287, 0.314] | <0.001 |

| Widowed | 0.205 | [0.194, 0.217] | <0.001 |

| Domestic partner | 0.183 | [0.172, 0.193] | <0.001 |

| Children | |||

| Yes | reference | – | – |

| No | 0.066 | [0.061, 0.072] | <0.001 |

| Income | |||

| Poorest20% | reference | – | – |

| Second20% | −0.012 | [-0.019, −0.005] | 0.001 |

| Middle20% | −0.010 | [-0.017, −0.003] | 0.008 |

| Fourth20% | −0.004 | [-0.011, 0.003] | 0.296 |

| Richest20% | 0.013 | [0.005, 0.020] | 0.002 |

| Employment Status | |||

| Employer | reference | – | – |

| Employed for self | 0.096 | [0.087, 0.105] | <0.001 |

| Part-time not want full-time | 0.206 | [0.197, 0.216] | <0.001 |

| Unemployed | 0.236 | [0.225, 0.246] | <0.001 |

| Part-time want full-time | 0.217 | [0.208, 0.226] | <0.001 |

| Out of work force | 0.247 | [0.241, 0.254] | <0.001 |

| Access to food | |||

| Not enough money for food | reference | – | – |

| Yes, enough money for food | −0.052 | [-0.057, −0.047] | <0.001 |

| Health Problems | |||

| Yes | reference | – | – |

| No | 0.018 | [0.012, 0.023] | <0.001 |

| Living Environment | |||

| A rural area or on a farm | reference | – | – |

| A small town or village | −0.012 | [-0.018, −0.006] | <0.001 |

| A large city | −0.048 | [-0.054, −0.042] | <0.001 |

| A suburb of a large city | −0.043 | [-0.051, −0.034] | <0.001 |

| Religion | |||

| Secular/Non-religious | reference | – | – |

| Christian | −0.035 | [-0.044, −0.026] | <0.001 |

| Islam | −0.167 | [-0.178, −0.156] | <0.001 |

| Hinduism | −0.018 | [-0.037, 0.001] | 0.063 |

| Buddhism | −0.062 | [-0.077, −0.047] | <0.001 |

| Judaism | −0.205 | [-0.241, −0.170] | <0.001 |

| Region | |||

| European Union (EU) Members | reference | – | – |

| Non-EU European Countries | 0.022 | [0.012, 0.032] | <0.001 |

| Commonwealth of Independent States | 0.016 | [0.007, 0.026] | 0.001 |

| Australia-New Zealand | −0.004 | [-0.031, 0.023] | 0.748 |

| Southeast Asia | 0.065 | [0.053, 0.077] | <0.001 |

| South Asia | −0.111 | [-0.126, −0.096] | <0.001 |

| East Asia | −0.218 | [-0.234, −0.201] | <0.001 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 0.042 | [0.034, 0.051] | <0.001 |

| Northern America | 0.053 | [0.034, 0.072] | <0.001 |

| Middle East and North Africa | −0.177 | [-0.189, −0.165] | <0.001 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | −0.055 | [-0.063, −0.046] | <0.001 |

| Life Evaluation | −9.730E-5 | [0, 7.622E-5] | 0.272 |

| Positive Index | 0.001 | [0.001, 0.001] | <0.001 |

| Negative Index | −1.351E-5 | [-9.641E-5, 6.939E-5] | 0.749 |

Note: Estimates calculated from Poisson model using survey weights provided by GWP and adjusted for all of the variables included in the table.

Raw scores for disparities in cooking frequency (lunch/dinner combined) based on gender (women-men) are shown for individual countries, organized by region and ranked from greatest to lowest disparity, in Supplemental Table S5. In the EU member countries, the greatest gender disparities were found in Poland (6.3) and the Czech Republic (6.2), whereas the lowest disparities were found in Denmark (1.7) and Sweden (2.1). There were large differences across countries in other regions of the world as well. For example, in Latin America and the Caribbean, the largest disparities between women vs men cooking at home were found in Honduras (7.8) and Guatemala (7.6) and the lowest in Chile (3.3) and Haiti (0.9). In Southeast Asia, Myanmar had the highest gender disparity of home cooking (7.5) and Thailand the lowest (1.5).

The results of the country level analysis of how gender disparities in cooking frequency are associated with subjective well-being are displayed in Table 3 . Greater gender disparity in cooking frequency is associated with lower Positive Experience Index scores (β = −0.021, p = 0.009). The gender disparities in cooking frequency were not associated with either Life Evaluation or Negative Experience Index.

Table 3.

Country level regression results for the relationship between disparities in cooking frequency based on gender and subjective well-being.

| Subjective well-being (N = 123) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Life Evaluation |

Positive experience |

Negative experience |

|

| (range:0–10) |

(range:0–100) |

(range:0–100) |

|

| Β (SE) | Β (SE) | Β (SE) | |

| Gender disparity in cooking frequency (mean:0, SD:1) | 0.006 (0.057) | −0.021** (0.008) | 0.002 (0.07) |

| Log GDP per capita | 0.278** (0.102) | −0.003 (0.014) | −0.007 (0.012) |

| Healthy life expectancy at birth | 0.030 (0.016) | −0.001 (0.002) | 5.851E-5 (0.002) |

| Generosity | 0.117 (0.411) | 0.089 (0.056) | −0.035 (0.048) |

| Perception of corruption | −0.995 (0.377) | 0.024 (0.052) | 0.027 (0.044) |

| Freedom to make life choices | 1.563** (0.569) | 0.512** (0.078) | −0.064 (0.067) |

| Social support | 2.384 (0.807) | 0.235 (0.110) | −0.398** (0.095) |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.702** | 0.450** | 0.397** |

Note: Life evaluation is perceptions of where respondents stand now. Positive and Negative experience are measures of respondents' experienced well-being on the day before the survey. High score explains high experiencing positive and negative for each measure. Gender disparity is the mean difference in cooking frequency between women and men. The measure of healthy life expectancy at birth is constructed based on data from the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Health Observatory data repository. Generosity is the residual of regressing the national average of GWP responses to the question “Have you donated money to a charity in the past month?” on GDP per capita. Perceptions of corruption are the average of binary answers to two GWP questions: “Is corruption widespread throughout the government or not?” and “Is corruption widespread within businesses or not?” Where data for government corruption are missing, the perception of business corruption is used as the overall corruption-perception measure. Freedom to make life choices is the national average of binary responses to the GWP question “Are you satisfied or dissatisfied with your freedom to choose what you do with your life?” Social support is the national average of the binary responses (either 0 or 1) to the GWP question “If you were in trouble, do you have relatives or friends you can count on to help you whenever you need them, or not?”

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study on a global scale to examine the frequency of cooking lunch and dinner across the world using a common measure of cooking frequency (that includes a definition of what type of cooking is of interest), using data from nationally representative samples in 142 countries. These estimates are an important pre-COVID-19 pandemic, baseline measure by which future changes to scratch cooking practices can be compared and tracked over time, nationally and internationally.

Consistent with prior research, the present study highlights the extent to which cooking meals at home remains a highly gendered task(Bowen et al., 2019; Shapiro, 2004; Taillie, 2018; Trubek, 2017). Across the globe, in every country included in the study, women cooked both lunch and dinner more frequently than men, though the disparity does vary considerably between and within regions of the world. At the individual level, higher cooking frequency (of both lunch and dinner combined) is associated with greater age, marital status, presence of children in the home, employment status, and higher Positive Experience Index scores. Factors associated with less frequent cooking include higher education, higher income, and living in a more urban environment. Though these socio-demographic characteristics were statistically significantly associated with differences in cooking frequency, perhaps due to large sample sizes, the association was greater for gender by a factor of ≥3. The finding related to education is particularly interesting as prior evidence suggests that higher education has a complex relationship with home cooking frequency and confidence (McGowan et al., 2016; Mills, Brown, Wrieden, White, & Adams, 2017a; Virudachalam, Long, Harhay, Polsky, & Feudtner, 2013, pp. 1–9; Wolfson & Bleich, 2015; Wolfson et al., 2020). It is possible that in many contexts, higher education is associated with better economic circumstances which allows for more disposable income and, therefore, the ability to eat from away from home sources (i.e. restaurants) more frequently and not cook all meals at home. In light of the profound changes to daily life brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, the ever-changing global food system and continually evolving economic circumstances and social norms, the present findings paint a detailed and nuanced picture of differences in cooking frequency around the world, and between men and women, that will be an important baseline metric against which future changes can be measured.

Taken together, the finding that, at the individual level, more frequent cooking is associated with higher Positive Experience Index, but that at an aggregate level, higher disparities in cooking between men and women are associated with lower Positive Experience is notable. It is also notable that Negative Experience score and Life Satisfaction were not associated with cooking frequency at the individual level, or with gender disparities in cooking frequency when aggregated at the country level. Possible reasons for this could be explored in future research. That cooking more is associated with a higher Positive Experience score is consistent with prior literature indicating that many people cook because they enjoy it and find it relaxing, and that cooking is a way of connecting with people, showing love and caring, and is a way of expressing cultural identity and building close relationships (Mills, Susanna, et al., 2017b; Mills, S et al., 2017c; Wolfson, Bleich, Clegg Smith, & Frattaroli, 2016a). That greater disparities between men and women results in lower Positive Experience Index scores (aggregated at the country level) may speak to the fact that women cook more frequently because cooking is their responsibility due to division of household labor or societal norms. When cooking is viewed as a burden or chore, people are less likely to enjoy it which may, in part, explain this finding (Bowen et al., 2019).

Within regions, the variation in the disparities in frequency of cooking lunch and dinner between men and women varies widely. Explanations for such differences may highlight the importance of supportive policies that encourage and enable gender equity in household tasks, as well as different gender roles and societal norms. For example, in the EU, countries with the least disparity in cooking frequency between men and women (Denmark, Sweden, and Finland) have robust policies that support family leave for new parents (both men and women), and other supportive social policies that may encourage gender equity in household tasks such as cooking (Nandi et al., 2018). There is variation in cooking frequency, and gender disparities in cooking frequency within other regions as well, including Non-EU European countries, Southeast Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, the Middle East and North Africa, and in Sub-Saharan Africa, perhaps due to societal factors including differing food environments, social norms, and social policies. With COVID-19 and related lockdowns and social distancing measures having shifted patterns and practices of cooking at home(Di Renzo et al., 2020; Flanagan et al., 2020; Shupler et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020), it remains to be seen whether these gender differences in cooking frequency persist at similar levels post-pandemic. How patterns in cooking frequency and factors that influence cooking behavior shift over time, and what the implications of such changes may be for physical and mental health, are rich areas for future research. The CFQ could be incorporated into future nutrition trials to assess the relevance of cooking frequency on diet and health outcomes.

An important strength of this study is the use of a single measure of cooking frequency that provided a definition of how the respondent should define what it means to “cook”. In other national surveys, cooking frequency is asked about without further qualification (Wolfson & Bleich, 2015). This is potentially problematic because what it means to cook is open to wide interpretation and evidence shows that people do, indeed, interpret cooking to mean different things, which influences the way they respond to surveys about cooking behavior (Wolfson, Bleich, et al., 2016a; Wolfson, Smith, et al., 2016b). Relatedly, it should be noted that our estimates of cooking frequency are lower than other surveys. For example, the mean frequency of cooking dinner in the US in the present survey is 3 times/week. By comparison, in the US and the UK, recent estimates of cooking frequency show that over 50% of adults cook ≥5 times/week (Mills, S., et al., 2017c; Wolfson & Bleich, 2015). Because we explicitly asked participants to consider only meals prepared from scratch, using whole or minimally processed ingredients, we have a more specific measure of cooking meals than previously available. It was also important to provide a definition given the scale and scope of the GWP. Across the world and across rural and urban, developed and less developed nations, understanding of what it means to cook, and cooking practices, varies considerably. However, this more specific definition of cooking means that we can only comment on the frequency of (and gender disparities in) scratch cooking across the globe. It could be that if a more expansive definition of cooking was used, the gender disparities would have been smaller if men engaged in non-scratch cooking or food assembly more frequently.

Another strength of this study is that we asked about frequency of cooking both lunch and dinner, and then aggregated the two for main analyses. We did this because whether lunch or dinner is the main meal of the day differs across the globe. Many national surveys (e.g. the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in the US) only ask about frequency of cooking dinner. An additional strength worth noting is that we measure individual, rather than household cooking frequency allowing us to identify the characteristics of the person doing the scratch cooking in the household. While a household measure can also yield important information, by focusing on individual cooking frequency we can explore differences in who is doing the cooking, which is a novel contribution to the literature.

4.1. Limitations

These results should be considered in light of several limitations. First, we created new measures of cooking frequency which have not been validated or fielded in prior studies. However, pilot and field testing of these questions in the GWP showed that they were understood as intended by the study participants. Second, the GWP is fielded in more than 140 countries across the world and in a great diversity of environments. Even though we provided a definition of what we meant by cooking, that definition was not exhaustive. Cooking is a complex behavior that is practiced differently around the world and may have been interpreted differently in different contexts thus introducing measurement error and reducing the validity of our findings. However, similarities to national level estimates of cooking frequency (our estimates were similar, but slightly lower as would be expected given the more detailed definition of cooking) in countries where such estimates exist mitigates this concern to some extent. Third, we do not have any information about what food was being cooked or eaten so we cannot assess differences in cooking practices beyond frequency. Finally, the GWP is a cross-sectional survey and we cannot make any causal inferences as to the relationship between disparities in cooking frequency and subjective well-being, or the causes of differences in cooking frequency or disparities in cooking frequency across the world.

5. Conclusions

This study assessed frequency of cooking “from scratch” worldwide prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Across the globe, the frequency with which men and women cook meals varies considerably, with women cooking much more frequently than men. As the food system and social norms continue to evolve, it will be important to monitor concurrent changes to the way people around the world cook, and how those changes are related to diet and diet related health outcomes at national, regional, and global levels.

Author contributions

DE, JM and JAW conceptualized the study and led the drafting of the survey questions. YI and CH conducted the analyses, JAW, JM, YI, CH, and DE contributed to the interpretation of the results, JAW wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Funding

No specific funding was received for this study. However, JAW was supported by the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive And Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (Award #K01DK119166). In addition, YI was a paid advisor to CookPad, a Japan based company which funded the cooking frequency module in the Gallup World Poll in 2018 upon which the present analyses are based. In addition, DE is a paid scientific advisor to CookPad; however, this consultancy began after this survey and study were planned and initiated. CookPad did have input on the development of the cooking frequency questionnaire but did not have any role in the analyses presented here. The authors were solely responsible for the study design, analysis, interpretation and writing of this article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained by Gallup, INC (Protocol #2019-08-02).

Declaration of competing interest

JAW, KJ, and JM have no conflicts of interest to report. YI and DE are paid consultants to CookPad, a Japan based company, which sponsored the cooking frequency questionnaire in the Gallup World Poll. While CookPad did have input in the design of the Cooking Frequency Questionnaire, they did not have any role in the collection of data, the study design this paper, the analysis or interpretation of data, the writing of the report or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the efforts of the Gallup World Poll in collecting the data used for this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105117.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Bowen S., Brenton J., Elliott S. Oxford University Press; 2019. Pressure cooker: Why home cooking won't solve our problems and what we can do about it. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers D. Cooking trends echo changing roles of women. Food Review: Magazine of Food Econom. 2000;23 [Google Scholar]

- Di Renzo L., Gualtieri P., Pivari F., Soldati L., Attinà A., Cinelli G., et al. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: An Italian survey. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2020;18 doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02399-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler-Stringer R. Food, cooking skills, and health: A literature review. Canadian Journal of Dietetic Practice and Research. 2010;71:141–145. doi: 10.3148/71.3.2010.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler-Stringer R. Food selection and preparation practices in a group of young low-income women in Montreal. Appetite. 2011;56:118–121. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan E.W., Beyl R.A., Fearnbach S.N., Altazan A.D., Martin C.K., Redman L.M. The impact of COVID‐19 stay‐at‐home orders on health behaviors in adults. Obesity. 2020 doi: 10.1002/oby.23066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frongillo E.A., Nguyen H.T., Smith M.D., Coleman-Jensen A. Food insecurity is associated with subjective well-being among individuals from 138 countries in the 2014 Gallup world Poll. Journal of Nutrition. 2017;147:680–687. doi: 10.3945/jn.116.243642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallup Inc . In: 2018 global emotions report. Gallup I., editor. Vol. 2020. Gallup Inc; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup I. Gallup world Poll methodology. Vol. 2019. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Headey D.D. 2013. The global landscape of poverty, food insecurity, and malnutrition and implications for agricultural development strategies. [Google Scholar]

- Jones A.D. Food insecurity and mental health status: A global analysis of 149 countries. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2017;53:264–273. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang T., Caraher M. Is there a culinary skills transition? Data and debate from the UK about changes in cooking culture. J. Home Econom Instit. Australia. 2001;8:2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Malik V.S., Willett W.C., Hu F.B. Global obesity: Trends, risk factors and policy implications. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2013;9:13–27. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2012.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan L., Caraher M., Raats M., Lavelle F., Hollywood L., McDowell D., et al. Domestic cooking and food skills: A review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2015;57(11) doi: 10.1080/10408398.2015.1072495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan L., Pot G.K., Stephen A.M., Lavelle F., Spence M., Raats M., et al. The influence of socio-demographic, psychological and knowledge-related variables alongside perceived cooking and food skills abilities in the prediction of diet quality in adults: A nationally representative cross-sectional study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2016;13:111. doi: 10.1186/s12966-016-0440-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills S., Brown H., Wrieden W., White M., Adams J. Frequency of eating home cooked meals and potential benefits for diet and health: Cross-sectional analysis of a population-based cohort study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2017;14:109. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0567-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills S., White M., Brown H., Wrieden W., Kwasnicka D., Halligan J., et al. Health and social determinants and outcomes of home cooking: A systematic review of observational studies. Appetite. 2017;111:116–134. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills S., White M., Wrieden W., Brown H., Stead M., Adams J. Home food preparation practices, experiences and perceptions: A qualitative interview study with photo-elicitation. PloS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi A., Jahagirdar D., Dimitris M.C., Labrecque J.A., Strumpf E.C., Kaufman J.S., et al. The impact of parental and medical leave policies on socioeconomic and health outcomes in OECD countries: A systematic review of the empirical literature. The Milbank Quarterly. 2018;96:434–471. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkin B.M. Nutrition transition and the global diabetes epidemic. Current Diabetes Reports. 2015;15:64. doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0631-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkin B.M. Relationship between shifts in food system dynamics and acceleration of the global nutrition transition. Nutrition Reviews. 2017;75:73–82. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuw064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkin B.M., Adair L.S., Ng S.W. Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutrition Reviews. 2012;70:3–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00456.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro L. Viking; New York: 2004. Something from the oven: Reinventing dinner in 1950s America. [Google Scholar]

- Shupler M., Mwitari J., Gohole A., Anderson De Cuevas R., Puzzolo E., Cukic I., et al. COVID-19 lockdown in a Kenyan informal settlement: Impacts on household energy and food security. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith L.P., Ng S.W., Popkin B.M. Trends in US home food preparation and consumption: Analysis of national nutrition surveys and time use studies from 1965-1966 to 2007-2008. Nutrition Journal. 2013;12:45. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A., Deaton A., Stone A.A. Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. Lancet. 2015;385:640–648. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61489-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinburn B.A., Sacks G., Hall K.D. The global obesity pandemic: Shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011;378 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60813-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taillie L.S. Who's cooking? Trends in US home food preparation by gender, education, and race/ethnicity from 2003 to 2016. Nutrition Journal. 2018;17:41. doi: 10.1186/s12937-018-0347-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trubek A.B. Vol. 66. Univ of California Press; 2017. (Making modern meals: How Americans cook today). [Google Scholar]

- Virudachalam S., Long J.A., Harhay M.O., Polsky D.E., Feudtner C. Public Health Nutr, FirstView; 2013. Prevalence and patterns of cooking dinner at home in the USA: National health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 2007–2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson J.A., Bleich S.N. Is cooking at home associated with better diet quality or weight-loss intention? Public Health Nutrition. 2015;18:1397–1406. doi: 10.1017/S1368980014001943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson J.A., Bleich S.N., Clegg Smith K., Frattaroli S. What does cooking mean to you?: Perceptions of cooking and factors related to cooking behavior. Appetite. 2016;97:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson J.A., Leung C.W., Richardson C.R. More frequent cooking at home is associated with higher Healthy Eating Index-2015 score. Public Health Nutrition. 2020;23:2384–2394. doi: 10.1017/S1368980019003549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson J.A., Smith K.C., Frattaroli S., Bleich S.N. Public perceptions of cooking and the implications for cooking behaviour in the USA. Public Health Nutrition. 2016;19:1606–1615. doi: 10.1017/S1368980015003778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Zhao A., Ke Y., Huo S., Ma Y., Zhang Y., et al. Dietary behaviors in the post-lockdown period and its effects on dietary diversity: The second stage of a nutrition survey in a longitudinal Chinese study in the COVID-19 era. Nutrients. 2020;12:3269. doi: 10.3390/nu12113269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong G., Eisenberg D.M., Hu F.B., Sun Q. Consumption of meals prepared at home and risk of type 2 diabetes: An analysis of two prospective cohort studies. PLoS Medicine. 2016;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.