Key Points

Question

Does 2 units of ABO-compatible, high-titer convalescent plasma, administered to critically ill patients with COVID-19, improve organ support–free days up to day 21 (a composite end point of in-hospital mortality and the duration of intensive care unit–based respiratory or cardiovascular support)?

Findings

This international bayesian randomized clinical trial that included 2011 participants treated with 2 units of high-titer convalescent plasma, compared with no convalescent plasma, resulted in a posterior probability of futility of 99.4% for the primary outcome of organ support–free days up to day 21.

Meaning

Among critically ill adults with confirmed COVID-19, treatment with convalescent plasma had a low likelihood of providing improvement in organ support–free days.

Abstract

Importance

The evidence for benefit of convalescent plasma for critically ill patients with COVID-19 is inconclusive.

Objective

To determine whether convalescent plasma would improve outcomes for critically ill adults with COVID-19.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The ongoing Randomized, Embedded, Multifactorial, Adaptive Platform Trial for Community-Acquired Pneumonia (REMAP-CAP) enrolled and randomized 4763 adults with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 between March 9, 2020, and January 18, 2021, within at least 1 domain; 2011 critically ill adults were randomized to open-label interventions in the immunoglobulin domain at 129 sites in 4 countries. Follow-up ended on April 19, 2021.

Interventions

The immunoglobulin domain randomized participants to receive 2 units of high-titer, ABO-compatible convalescent plasma (total volume of 550 mL ± 150 mL) within 48 hours of randomization (n = 1084) or no convalescent plasma (n = 916).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary ordinal end point was organ support–free days (days alive and free of intensive care unit–based organ support) up to day 21 (range, −1 to 21 days; patients who died were assigned –1 day). The primary analysis was an adjusted bayesian cumulative logistic model. Superiority was defined as the posterior probability of an odds ratio (OR) greater than 1 (threshold for trial conclusion of superiority >99%). Futility was defined as the posterior probability of an OR less than 1.2 (threshold for trial conclusion of futility >95%). An OR greater than 1 represented improved survival, more organ support–free days, or both. The prespecified secondary outcomes included in-hospital survival; 28-day survival; 90-day survival; respiratory support–free days; cardiovascular support–free days; progression to invasive mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal mechanical oxygenation, or death; intensive care unit length of stay; hospital length of stay; World Health Organization ordinal scale score at day 14; venous thromboembolic events at 90 days; and serious adverse events.

Results

Among the 2011 participants who were randomized (median age, 61 [IQR, 52 to 70] years and 645/1998 [32.3%] women), 1990 (99%) completed the trial. The convalescent plasma intervention was stopped after the prespecified criterion for futility was met. The median number of organ support–free days was 0 (IQR, –1 to 16) in the convalescent plasma group and 3 (IQR, –1 to 16) in the no convalescent plasma group. The in-hospital mortality rate was 37.3% (401/1075) for the convalescent plasma group and 38.4% (347/904) for the no convalescent plasma group and the median number of days alive and free of organ support was 14 (IQR, 3 to 18) and 14 (IQR, 7 to 18), respectively. The median-adjusted OR was 0.97 (95% credible interval, 0.83 to 1.15) and the posterior probability of futility (OR <1.2) was 99.4% for the convalescent plasma group compared with the no convalescent plasma group. The treatment effects were consistent across the primary outcome and the 11 secondary outcomes. Serious adverse events were reported in 3.0% (32/1075) of participants in the convalescent plasma group and in 1.3% (12/905) of participants in the no convalescent plasma group.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among critically ill adults with confirmed COVID-19, treatment with 2 units of high-titer, ABO-compatible convalescent plasma had a low likelihood of providing improvement in the number of organ support–free days.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02735707

This study compares the effect of convalescent plasma vs no convalescent plasma on the outcome of organ support–free days in the hospital among critically ill adults with COVID-19 who had been randomized to the immunoglobulin domain in the ongoing REMAP-CAP trial.

Introduction

COVID-19 is an acute illness caused by SARS-CoV-2.1 Among the many treatments studied,2 only 2 immunomodulatory drugs, glucocorticoids and IL-6 receptor antagonists,3,4 have been shown to reduce mortality in hospitalized adults with COVID-19; and critically ill patients have shown greater benefit with glucocorticoids.5 Convalescent plasma (blood product containing SARS-CoV-2–specific antibodies) is a biologically plausible antiviral treatment with immunomodulatory properties6,7,8,9 that may offer greater benefit to critically ill patients with COVID-19, in whom multiorgan dysfunction could be driven by the higher prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in blood, also known as RNAemia, and by progressive host response.10,11 However, use of convalescent plasma for patients with COVID-19 has either been outside clinical trials, with more than 500 000 patients estimated to have received this treatment in the US by March 2021,12 or in randomized clinical trials that have not focused on critically ill patients with COVID-19, often without improving clinical outcomes, including in the recently published Randomized Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial.13,14,15

Therefore, trial investigators conducted an international, multicenter randomized clinical trial to address this uncertainty in the evidence and to determine whether use of convalescent plasma compared with no convalescent plasma improves outcomes in critically ill patients with COVID-19 within the Randomized, Embedded, Multifactorial, Adaptive Platform Trial for Community-Acquired Pneumonia (REMAP-CAP).

Methods

Trial Design

This trial was conducted within an international, multicenter, open-label adaptive platform designed to determine the best treatment strategies for patients with severe pneumonia in both settings during the pandemic and outside the pandemic. This trial’s design and results regarding glucocorticoids, anticoagulants, antivirals, and IL-6 receptor antagonists for treatment of COVID-19 have been reported previously.3,4,16,17,18

Patients were assessed for eligibility and randomized to different interventions across several domains. The ongoing trial is overseen by an international trial steering committee blinded to the treatment allocation and by an independent data and safety monitoring board (Supplement 1). This trial has been funded through multiple sources, approved by relevant regional research ethics committees, and conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The immunoglobulin domain evaluating convalescent plasma enrolled participants at trial sites in Australia, Canada, the UK, and the US. Informed consent, in accordance with local regulations, was obtained from all patients or their surrogates. Details of the trial design have been reported previously16 and appear in the trial protocol and statistical analysis plan in Supplement 1.

To account for the observed ethnic disparities in outcomes during the pandemic, this trial collected self-reported race and ethnicity data from either the participants or their surrogates via fixed categories appropriate to their region.

Participants

Patients aged 18 years or older with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection admitted to the hospital and classified as moderately or severely ill were eligible for enrollment in the COVID-19 immunoglobulin domain, which are equivalent to the World Health Organization case definitions of severely or critically ill, respectively.19 The outcomes for critically ill participants (defined as patients admitted to an intensive care unit [ICU]) and receiving respiratory (invasive or noninvasive mechanical ventilation, including high-flow nasal cannula with a flow rate ≥30 L per minute and fractional inspired oxygen concentration ≥40%) or cardiovascular (infusion of vasopressor or inotropes) organ support are reported in this article.3,4,16,17,18

Trial exclusion criteria included presumption that death was imminent with lack of commitment to full support or participation in this trial within the prior 90 days. Immunoglobulin domain–specific exclusion criteria included: known hypersensitivity to convalescent plasma; objection to receiving plasma products; previous history of transfusion-related acute lung injury; and more than 48 hours had elapsed since ICU admission or 14 days since hospital admission. Further details regarding eligibility appear in Supplement 1 (immunoglobulin domain–specific appendices) and in Supplement 2 (eMethods).

Treatment Allocation

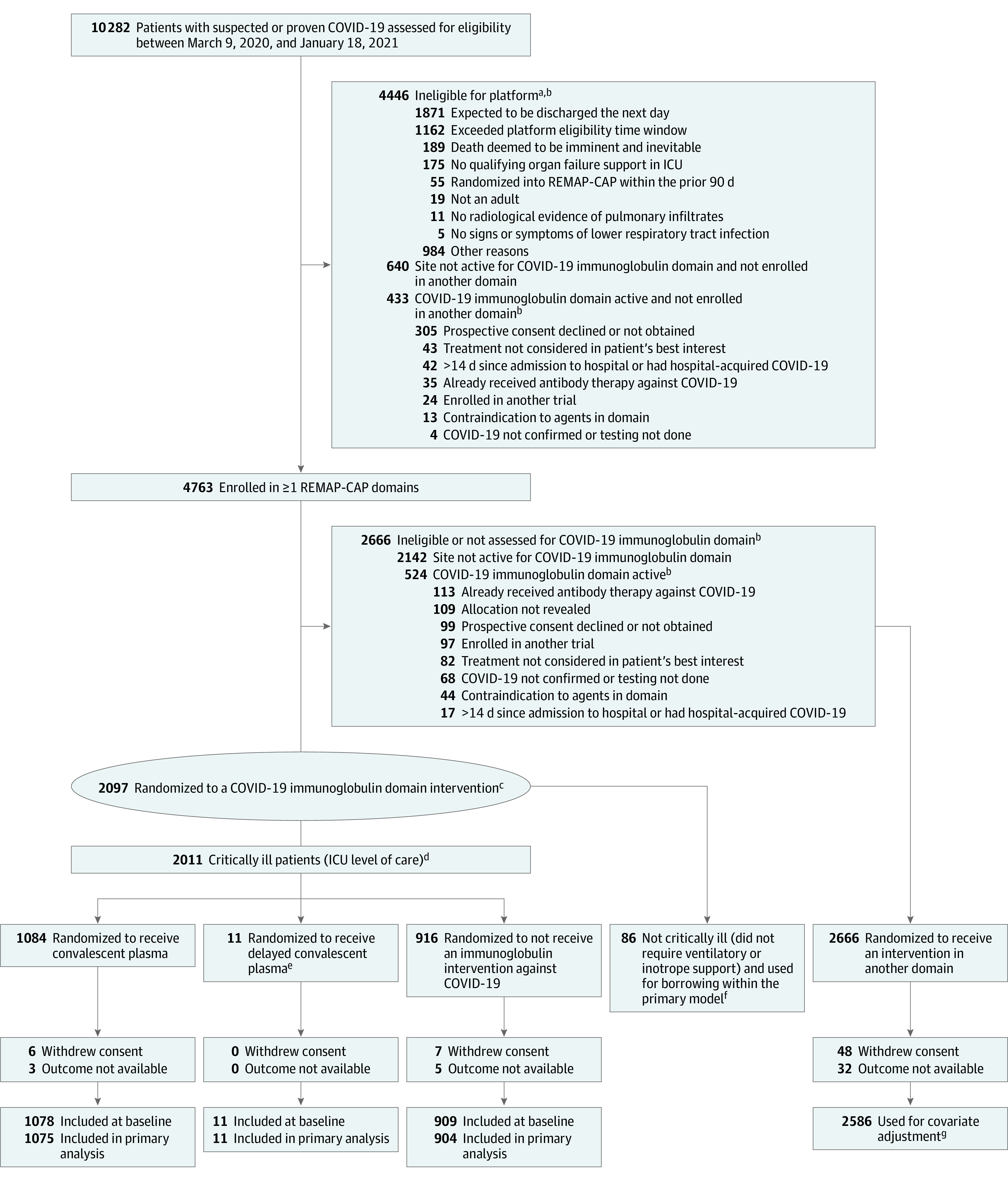

The COVID-19 immunoglobulin domain contained 3 interventions: convalescent plasma at randomization, delayed convalescent plasma (given if clinical deterioration and only available at 1 site in the US), and no convalescent plasma. Participants were randomized via a centralized computer program to each intervention (available locally) starting with balanced assignment (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Screening, Randomization, and Follow-up of Participants in the REMAP-CAP COVID-19 Immunoglobulin Domain Randomized Clinical Trial.

aSee Supplement 1 for additional information about the platform trial.

bPatients could have met more than 1 ineligibility criterion. A domain refers to a common therapeutic area (eg, antiviral therapy) within which several interventions or intervention dosing strategies could be randomly assigned.16

cRequired to have high-flow nasal cannula oxygenation, invasive or noninvasive mechanical ventilation, or vasopressor or inotropic infusion.

dRandomization started with balanced assignment and then adapted with preferential assignment to those interventions that appeared most favorable until predefined statistical triggers of superiority or futility were met.

eAdditional information about delayed convalescent plasma appears in Supplement 2 (eTables 1 and 5 and eFigure 1).

fThe results for patients who were not critically ill were partially pooled with critically ill patients in the primary analysis, which provides a more precise estimate of the treatment effect of convalescent plasma.

gThe primary analysis of alternative interventions within the immunoglobulin domain is estimated from a model that adjusts for patient factors and for assignment to other interventions.

Procedures

The trial used an open-label design and convalescent plasma was supplied by each site’s transfusion laboratory; clinical teams at each site were provided instructions for convalescent plasma administration. This was an open-label study because it was considered unethical to expose patients in the standard of care group, who may have severe lung injury and hypoxia, to receive a potentially harmful extra volume of fluid (with either nonconvalescent fresh frozen plasma or saline) as part of a usual care placebo intervention. Details of donor selection, plasma manufacture, testing of convalescent plasma in each country, and convalescent plasma administration appear in Supplement 2 (eMethods).

Other aspects of care were provided per each site’s standard of care. In addition to assignments in the immunoglobulin domain, participants could be randomized to additional interventions within other domains, depending on the domains active at the particular treatment site, patient eligibility, and consent (Supplement 1). Randomization to the corticosteroid domain for COVID-19 closed on June 17, 2020.16 Thereafter, glucocorticoids were allowed as the recommended standard of care.

Although clinical staff were aware of their individual patient’s intervention assignment, neither they nor the international trial steering committee were provided any information about aggregate patient outcomes. Data were collected prospectively at the bedside by local research teams.

Interventions

Participants were randomized to receive high-titer, ABO-compatible convalescent plasma (total volume approximately 550 mL ± 150 mL) within 48 hours of randomization or no convalescent plasma. All convalescent plasma used in the trial was tested for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and met a minimum titer criterion prior to administration. The details of the method of testing and minimum titer criterion for convalescent plasma in each country appear in Supplement 2 (eMethods).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was respiratory and cardiovascular organ support–free days up to day 21. The definitions of respiratory and cardiovascular organ support were the same as in the inclusion criteria. In this composite ordinal outcome, all deaths within the hospital, up to day 90, are assigned the worst outcome (–1 day). Among survivors, respiratory and cardiovascular organ support–free days were calculated up to day 21, such that a higher number represents faster recovery. The best outcome would be 21 organ support–free days.

The prespecified secondary outcomes included in-hospital survival; 28-day survival; 90-day survival; respiratory support–free days; cardiovascular support–free days; progression to invasive mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal mechanical oxygenation, or death; ICU length of stay; hospital length of stay; World Health Organization ordinal scale score at day 14; venous thromboembolic events at 90 days; and serious adverse events (eMethods in Supplement 2).

Trial Power and Sample Size

This trial used a bayesian design with no maximum sample size. Regular adaptive analyses were conducted and randomization continued, potentially with response-adaptive randomization (with preferential assignment to those interventions that appear most favorable) until a predefined statistical trigger of superiority or futility was met. Response-adaptive randomization was used in the immunoglobulin domain starting on November 23, 2020.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis plan for the COVID-19 immunoglobulin domain was written while investigators were blinded to treatment allocation and posted online before data lock and the analyses (Supplement 1). The primary analysis was generated from a bayesian cumulative logistic model, which calculated posterior probability distributions of organ support–free days up to day 21 (primary outcome) based on evidence accumulated in the trial and assumed prior knowledge in the form of a prior distribution. Prior distributions for the treatment effects in the moderate and severe states of illness were nested in a hierarchical prior distribution centered on an overall intervention effect estimated with a neutral prior assuming no treatment effect (standard normal prior on the log odds ratio [OR]). The primary model adjusted for location (site nested within country), age (categorized into 6 groups), sex, and period (2-week epochs). The model contained treatment effects for each intervention within each domain.

The primary analysis was conducted on all randomized patients as of January 18, 2021, and not just those randomized within the immunoglobulin domain. This approach allowed maximal incorporation of all information, providing the most robust estimation of the coefficients of all included covariates. Not all patients were eligible for all domains nor for all interventions within each domain (depending on site participation, baseline entry criteria, and patient or surrogate preference).

Because the primary model included information about assignment to interventions within domains whose evaluation is ongoing, the analysis was run by the statistical analysis committee unblinded to the treatment allocation, which conducts all protocol-specified trial adaptive analyses and reports the results to the data and safety monitoring board (Supplement 1).

The cumulative log odds for the primary end point were modeled such that a parameter greater than 0 reflects an increase in the cumulative odds for the organ support–free days outcome, which implies benefit. The model assumed proportional effects across the ordinal organ support–free days scale. There was no imputation of missing primary (or secondary) end point values.

The posterior distribution of the ORs is summarized by allowing calculation of ORs with 95% credible intervals (CrIs) and the probability that convalescent plasma was superior or futile compared with no convalescent plasma. An OR greater than 1 represents improved survival, more organ support–free days, or both. The predefined statistical triggers for trial conclusion and disclosure were superior results (if >99% posterior probability, the OR was >1 compared with no convalescent plasma) and futile results (if >95% posterior probability, the OR was <1.2 compared with no convalescent plasma). The predefined statistical trigger of an OR of less than 1.2 for futility was a pragmatic choice during a global pandemic as a balance between demonstrating an important clinical improvement and the need to declare futility to allow other more promising interventions to be assessed.

The sensitivity and secondary analyses were performed by blinded investigators. The analysis population was restricted to only critically ill patients with COVID-19 enrolled in the domains that had stopped and were unblinded at the time of analysis with no adjustment for assignment in other ongoing domains. Safety analyses (serious adverse events and venous thromboembolism at 90 days) were restricted to data from patients enrolled in the immunoglobulin domain.

Additional sensitivity analyses of organ support–free days and in-hospital mortality were restricted to data from patients enrolled in the immunoglobulin domain with no adjustment for assignment in any other domains. The following sensitivity analyses were conducted: (1) organ support–free days and in-hospital mortality without site and time adjustments; (2) organ support–free days and in-hospital mortality estimated with additional interactions between unblinded domains and interventions; and (3) organ support–free days and in-hospital mortality estimated with patients that were treated according to the protocol.

No formal hypothesis tests were performed on the secondary outcomes and the summaries of the posterior distributions were provided for descriptive purposes only. Secondary dichotomous outcomes were analyzed with bayesian logistic regression models. The secondary time-to-event outcomes (mortality and length of stay) were analyzed using a piecewise, exponential bayesian model to estimate hazard ratios.

The 6 prespecified subgroups were binary categories for presence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies at baseline; detectable virus at baseline in an upper respiratory sample; need for mechanical ventilation; immunosuppressed state; time from hospitalization to enrollment in recipients (categorized as <3 days, 3-7 days, and >7 days); and antibody titer of the convalescent plasma transfused. Further details of all analyses are provided in Supplement 3 and Supplement 4. The prespecified analyses are listed in the statistical analysis plan (Supplement 1). Data management and summaries were created using R version 3.6.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) and the primary analysis was computed using R version 4.0.0 and the rstan package version 2.21.1. Additional data management and analyses were performed in SQL 2016 (Microsoft), SPSS version 26 (IBM), and Stata version 14.2 (StataCorp).

Results

At a scheduled adaptive analysis, the statistical trigger for futility in critically ill participants with COVID-19 was met (posterior probability of futility of 96.4%; OR, 0.95 [95% CrI, 0.73-1.23]). Assignment to this domain closed on January 11, 2021, for critically ill participants (randomization continued for participants who were not critically ill). After announcement of the preliminary RECOVERY trial results on January 15, 2021, the international trial steering committee halted recruitment of all patients within the domain.20

Participants

Between March 9, 2020, and January 18, 2021, of 10 282 screened patients, 4763 who were hospitalized with COVID-19 were enrolled in this trial and were randomized within at least 1 therapeutic domain (Figure 1). Patients were recruited to the immunoglobulin domain from May 5, 2020, at 129 sites in Australia (n = 4), Canada (n = 9), the UK (n = 115), and the US (n = 1). Among the 2097 participants enrolled in the domain, 2011 were critically ill (median age, 61 years [IQR, 52-70 years] and 645/1998 [32.3%] women) and were randomly assigned to convalescent plasma at randomization (n = 1084), convalescent plasma if clinical deterioration (n = 11), or no convalescent plasma (n = 916). Follow-up of participants ended on April 19, 2021, and 1990 (99%) completed the trial. Further information about hospitalized participants with COVID-19 who were not critically ill and participants in the convalescent plasma if clinical deterioration group appear in the eMethods and eFigure 1 in Supplement 2.

Thirteen participants subsequently withdrew consent and 8 participants had missing data for the primary outcome. The baseline characteristics of the participants randomized to convalescent plasma were similar across intervention groups and typical of patients requiring care in the ICU for COVID-19 (Table and eTables 1-2 in Supplement 2). All but 3 participants were receiving respiratory support at the time of randomization, including high-flow nasal oxygen (22%) and noninvasive (45%) and invasive (33%) mechanical ventilation. These 3 patients were receiving cardiovascular support (inotropes or vasopressors) only.

Table. Participant Characteristics at Baseline.

| Characteristic | Convalescent plasma (n = 1078)a | No convalescent plasma (n = 909)a |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 61 (52-69) | 61 (52-70) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 727 (67.4) | 618 (68.0) |

| Female | 351 (32.6) | 291 (32.0) |

| Race and ethnicity, No./total (%)b | ||

| Asian | 144/976 (14.8) | 133/832 (16.0) |

| Black | 51/976 (5.2) | 38/832 (4.6) |

| >1 race | 16/976 (1.6) | 8/832 (1.0) |

| White | 731/976 (74.9) | 619/832 (74.4) |

| Other | 34/976 (3.5) | 34/832 (4.1) |

| Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score, median (IQR)c | (n = 1044); 13.0 (8.0-19.0) | (n = 888); 12.0 (8.0-19.0) |

| Preexisting conditions, No./total (%) | ||

| Diabetes | 339/1078 (31.4) | 268/907 (29.5) |

| Respiratory disease | 245/1078 (22.7) | 216/907 (23.8) |

| Kidney diseased | 107/1000 (10.7) | 83/837 (9.9) |

| Severe cardiovascular diseasee | 96/1053 (9.1) | 67/890 (7.5) |

| Immunosuppressive disease or therapyf | 67/1066 (6.3) | 60/907 (6.6) |

| SARS-CoV-2, No./total (%) | ||

| RNA detected at randomization via a respiratory sample (wild-type or Alpha variant)g | 676/845 (80.0) | 489/599 (81.6) |

| Negative for antibody at baseline | 271/874 (31.0) | 149/558 (26.7) |

| Time to enrollment, median (IQR), hh | ||

| From hospital admissioni | 42.7 (23.6-78.6) | 41.7 (22.5-84.3) |

| From ICU admission | 17.7 (10.2-23.5) | 17.2 (10.6-23.2) |

| Use and type of acute respiratory supportj | ||

| Noninvasive mechanical ventilation | 493 (45.7) | 407 (44.8) |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 356 (33.0) | 289 (31.8) |

| High-flow nasal cannula | 225 (20.9) | 211 (23.2) |

| None or supplemental oxygen only | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) |

| Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) |

| Use of vasopressor supportj | 207 (19.2) | 175 (19.3) |

| Country of enrollment, No./total (%) | ||

| UK | 1023/1078 (94.9) | 868/909 (95.5) |

| Canada | 39/1078 (3.6) | 35/909 (3.9) |

| USk | 12/1078 (1.1) | 0/1078 |

| Australia | 4/1078 (0.4) | 6/909 (0.7) |

| COVID-19 therapy use, No./total (%)l | ||

| Glucocorticoids | 1014/1078 (94.1) | 845/909 (93.0) |

| Remdesivir | 491/1078 (45.5) | 398/909 (43.8) |

| Immunomodulators (tocilizumab or sarilumab) | 425/1078 (39.4) | 348/909 (38.3) |

No. (%) unless otherwise indicated; percentages may not sum to 100 because of rounding. Additional information appears in eTable 1 in Supplement 2.

Self-reported via fixed categories. Data collection was not approved in Asia, Canada, and continental Europe. “Other” includes “other ethnic group” and those who declined to respond or were not asked by registration personnel.

Measures the severity of illness based on age, medical history, and physiological variables. Scores range from 0 to 71; higher numbers represent greater risk of death. The median score of 12 is typical for patients with COVID-19 admitted to intensive care units (ICUs).

Determined from the most recent stable serum creatinine level prior to this hospital admission, except in patients who were receiving dialysis. Abnormal kidney function was defined as a creatinine level of 130 μmol/L or greater (≥1.5 mg/dL) for males or 100 μmol/L or greater (≥1.1 mg/dL) for females not previously receiving dialysis.

Defined as New York Heart Association class IV.

Recent chemotherapy, radiation, high-dose or long-term steroid treatment, or presence of immunosuppressive disease (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test was positive between 24 hours before and after randomization. PCR test conducted either within the same hospital admission or prior to admission.

The time to receipt of convalescent plasma from enrollment and randomization was a median of 5.7 hours (IQR, 3.5-17.8 hours) in 1013 patients.

Includes time in the emergency department.

Required to have high-flow nasal cannula oxygenation, invasive or noninvasive mechanical ventilation, or vasopressor or inotropic infusion.

Unable to randomize participants to the no convalescent plasma group due to the Emergency Use Authorization program of the US Food and Drug Administration.

Received within 48 hours of randomization.

Interventions and Co-interventions

In the convalescent plasma group, 85.6% (920/1075) received convalescent plasma per the trial protocol (additional details appear in Supplement 2) and 94.5% (1016/1075) received some convalescent plasma. In the no convalescent plasma group, 0.6% (5/905) received convalescent plasma.

Most patients were enrolled after the announcement of the dexamethasone results from the RECOVERY trial,21 therefore, 94% (1859/1987) of participants were treated with glucocorticoids (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Remdesivir use, as part of routine care, was recorded in 45% of participants. Most participants were enrolled before the announcement of the results regarding IL-6 receptor antagonists from this trial (eTables 1 and 3 in Supplement 2).4

Primary Outcome

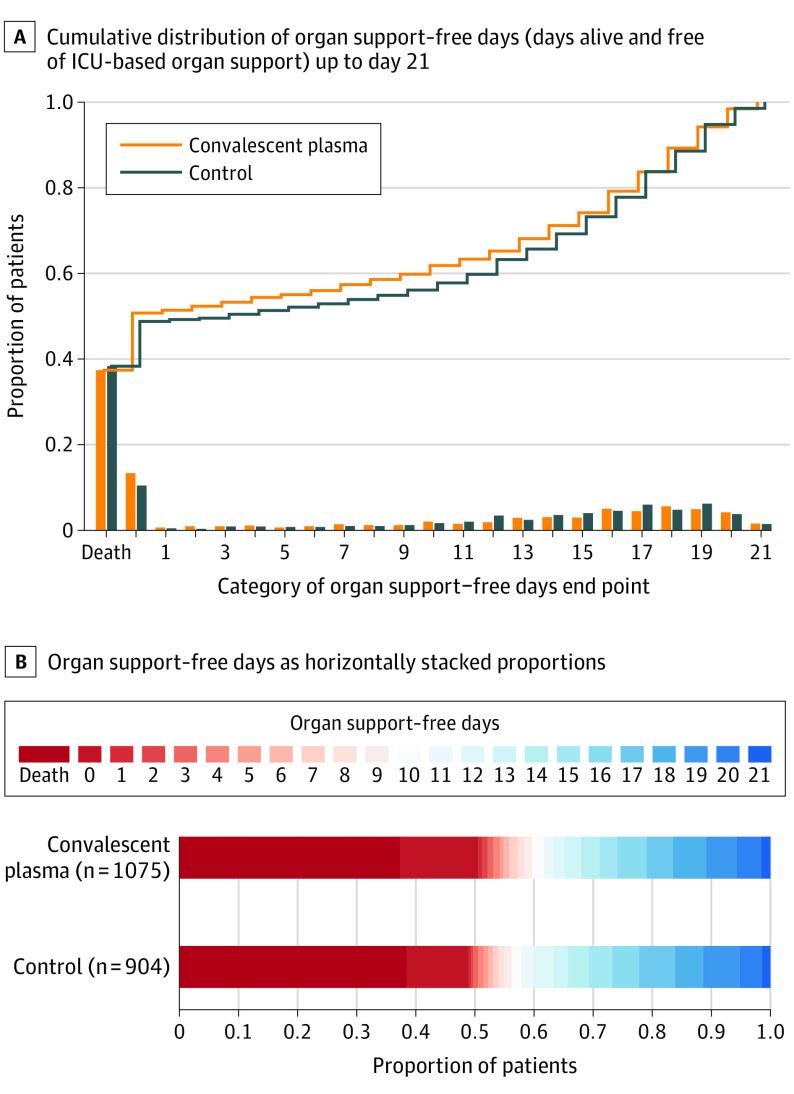

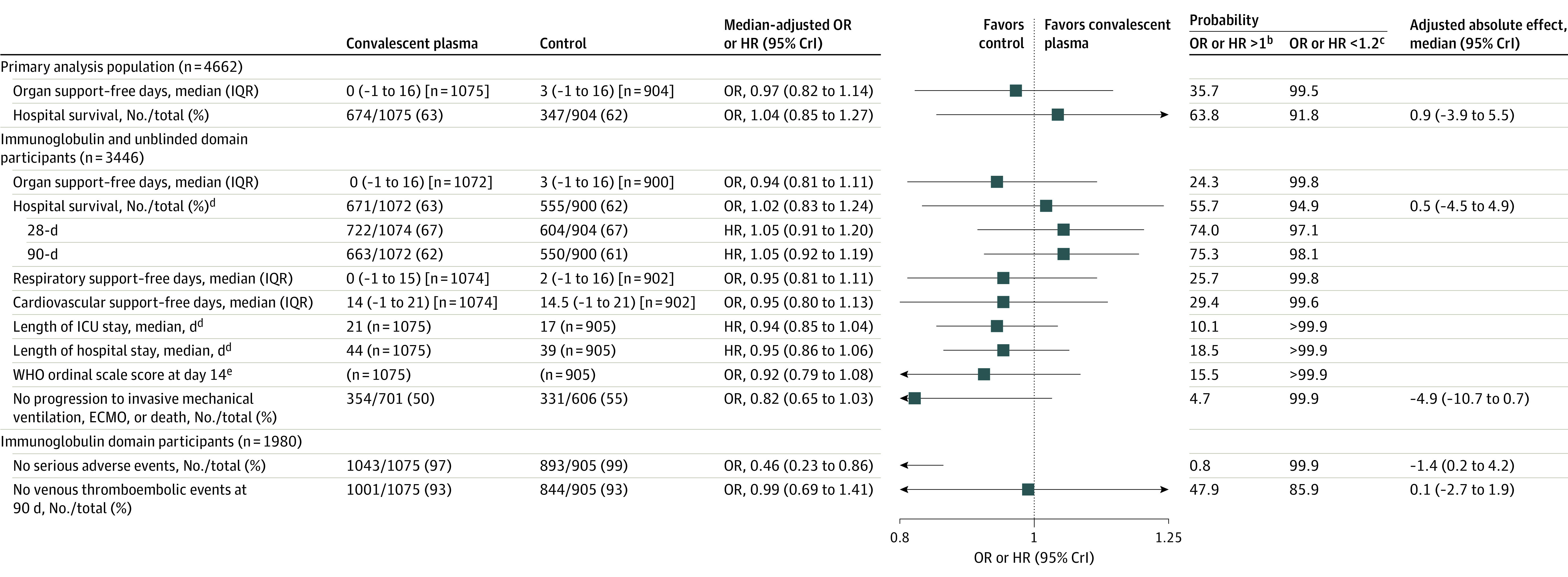

The median number of organ support–free days was 0 (IQR, −1 to 16) in the convalescent plasma group and 3 (IQR, −1 to 16) in the no convalescent plasma group (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Relative to no convalescent plasma, the median-adjusted OR from the primary model was 0.97 (95% CrI, 0.83 to 1.15), yielding a posterior probability of futility of 99.4%. Organ support–free days was a composite ordinal outcome of in-hospital mortality (rate of 37.3% [401/1075] for convalescent plasma group and 38.4% [347/904] for no convalescent plasma group) and days alive and free of organ support (median of 14 days [IQR, 3 to 18 days] for the convalescent plasma group and median of 14 days [IQR, 7 to 18 days] for the no convalescent plasma group). Compared with the no convalescent plasma group, the median-adjusted OR for in-hospital survival was 1.04 (95% CrI, 0.85 to 1.27) for the convalescent plasma group, yielding a posterior probability of futility of 91.8%. Potential interactions between convalescent plasma and other interventions were evaluated and reported in Supplement 2 (eTables 3-4). There were no clinically meaningful interactions.

Figure 2. Primary Outcome of Organ Support–Free Days Up to Day 21.

A, The ordinal scale includes death (in-hospital death, the worst possible outcome) and a score of 0 to 21 (the numbers of days alive without organ support) by trial group as the cumulative proportion (y-axis) for each trial group by day (x-axis), with death listed first. The curves that rise more slowly are more favorable. The difference in the height of the 2 curves at any point represents the difference in the cumulative probability of having a value for days without organ support of less than or equal to that point on the x-axis. B, The color red represents worse values and blue represents better values, the deepest red is death and deepest blue is 21 days. From the primary analysis using a bayesian cumulative logistic model, the median-adjusted odds ratio was 0.97 (95% credible interval, 0.83-1.15) for the convalescent plasma group compared with the no convalescent plasma group, yielding a probability of superiority of 37.8% over the no convalescent plasma group and a probability of futility of 99.4%.

Figure 3. Primary and Secondary Outcomesa.

Additional data are available in Supplement 2 (eTables 5-6). CrI indicates credible interval; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; HR, hazard ratio; ICU, intensive care unit; OR, odds ratio; WHO, World Health Organization.

aData for the secondary analyses excluded participants who had been randomized within another domain within the moderate stratum and then randomized to the immunoglobulin domain in the severe stratum (excluded 7 participants). A maximum of 1980 participants were included within the secondary analyses.

bAn OR or HR greater than 1 equates to the threshold for superiority to control for the primary outcome.

cAn OR or HR less than 1.2 equates to the threshold for futility for the primary outcome. No formal hypothesis tests were performed on the secondary outcomes and summaries of the posterior distributions were provided for descriptive purposes only.

dAnalyzed as time-to-event outcomes. The 28-day and 90-day survival outcomes are summarized as the proportion alive at days 28 and 90. The lengths of ICU stay and hospital stay are summarized by the median time to ICU and hospital discharge.

eBased on the data collected, a modified version of the original WHO scale was used, combining outcome scores of 0 to 2 into a single category (0 = uninfected, 1 = ambulatory with no limitation of activities, and 2 = ambulatory with limitation of activities). For the convalescent plasma group, the median WHO score was 6 (required intubation and mechanical ventilation) and the IQR range was 3 (hospitalized but did not require oxygen therapy) to 7 (required ventilation plus additional organ support with vasopressors, kidney replacement therapy, or ECMO). For the no convalescent plasma group, the median WHO score was 5 (required noninvasive mechanical ventilation or high-flow oxygen) and the IQR was the combined 0-2 score (uninfected or ambulatory) to 7 (required ventilation plus additional organ support with vasopressors, kidney replacement therapy, or ECMO).

The prespecified secondary analyses of the primary outcome using only data from participants in the immunoglobulin domain were consistent with the primary analysis (eTable 5 in Supplement 2).

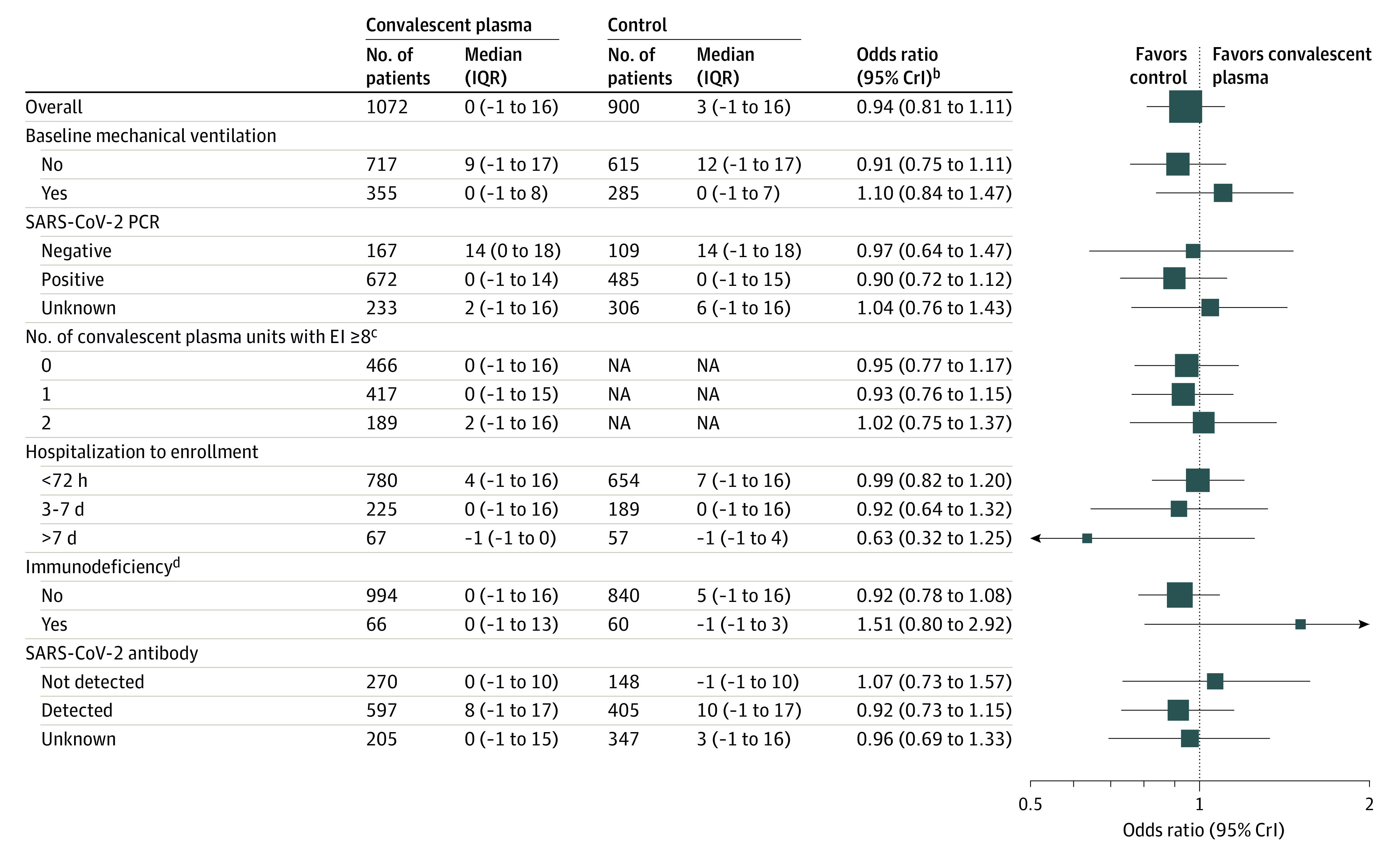

In the prespecified subgroup analyses, based on participant characteristics at baseline, the estimated treatment effect of convalescent plasma did not meaningfully vary by (1) SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction status, (2) detectable anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibody at baseline, (3) mechanical ventilation at baseline, and (4) antibody titer in plasma product (Figure 4). In the small number of participants (n = 126) with immunodeficiency at baseline, convalescent plasma demonstrated potential benefit (posterior probability of superiority of 89.8%). In the subgroup of participants randomized more than 7 days into their hospitalizations (n = 126), convalescent plasma may be harmful (posterior probability of harm of 90.3%; OR <1.0).

Figure 4. Prespecified Subgroup Analyses for the Primary Outcome of Organ Support–Free Daysa.

CrI indicates credible interval; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

aExcluded participants who had been randomized within another domain within the moderate stratum and then randomized to the immunoglobulin domain in the severe stratum (excluded 7 participants). A maximum of 1980 participants were included within the subgroup analyses and there were known outcomes for organ support–free days for 1972 of these participants.

bAn odds ratio greater than 1 equates to the threshold for superiority vs control for the primary outcome. An odds ratio less than 1.2 equates to the threshold of futility for the primary outcome.

cFor the number of units administered with SARS-CoV-2 antibody titers of 8 or greater (measured via the Euroimmun assay), the number of participants analyzed equals the total number in the no convalescent plasma (control) group (n = 900) plus the number in the intervention group who received 0, 1, or 2 units of convalescent plasma.

dDefined as receiving an immunosuppressive treatment or having an immunosuppressive disease (the full definition appears in the eMethods in Supplement 2).

Secondary Outcomes

The secondary outcomes are presented in Figure 3 and Supplement 2 (eTable 6). The full model results of all outcome analyses appear in Supplement 3 and Supplement 4. Compared with no convalescent plasma, convalescent plasma had treatment effects consistent with the primary outcome for the prespecified secondary outcomes.

Adverse Events

Of 1980 participants who experienced adverse events, 44 (2.2%) had at least 1 serious adverse event; 32/1075 (3.0%) in the convalescent plasma group and 12/905 (1.3%) in the no convalescent plasma group (eTable 7 in Supplement 2). Only 1 event was considered to be possibly or probably related to convalescent plasma.

Sensitivity Analyses

The sensitivity analyses were consistent with the primary analysis (eTable 8 in Supplement 2).

Discussion

In critically ill adults with confirmed COVID-19, treatment with 2 units of high-titer, ABO-compatible convalescent plasma had a low likelihood of providing a meaningful improvement in organ support–free days, compared with no convalescent plasma, with a probability of futility of 99.4%. The observed treatment effects were consistent across the secondary outcomes and in all the sensitivity analyses.

This results of this trial are consistent with the lack of benefit of convalescent plasma for patients hospitalized with moderate or severe COVID-19 reported in the RECOVERY trial,13 and with the meta-analyses within the systematic review by Piechotta et al.14

Among the predefined subgroups, there was no evidence for a meaningful difference in the treatment effect with convalescent plasma compared with no convalescent plasma, with the exception of the small number of participants with immunodeficiency at baseline. In this trial, 75% of participants received advanced respiratory support, which often occurs between 7 days and 10 days after symptom onset, and by which stage in the disease many patients who are immunocompetent will have developed endogenous antibody responses.22 This could explain the overall results, including the effect observed in the prespecified immunodeficiency subgroup (Figure 4). These findings also warrant further investigation of the hypotheses that benefit with convalescent plasma may be different early on in the illness,22,23 and perhaps in patients with an impaired immune system who are unable to mount effective immune responses, including antibody responses.23,24

The prespecified anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibody and SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction status subgroups were used to evaluate the hypotheses that the antibody-negative population and respiratory polymerase chain reaction–positive population may derive benefit from convalescent plasma therapy. Overall, participants negative for anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibody had a higher mortality compared with participants positive for the antibody. The viral loads in respiratory samples were high,25 which is consistent with greater prevalence of viral RNAemia in critically ill patients with COVID-19.10 However, no differences in treatment effect were observed within these 2 subgroups, even when the RECOVERY data were taken into consideration (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2). The potential reported benefit in participants negative for the antibody and who were treated with monoclonal antibody therapy, suggests a higher dose of convalescent plasma may be needed to improve outcomes.26

The strengths of this trial include a design that assessed the effect of administration of high-titer convalescent plasma in critically ill adults on patient-centered outcomes, with the majority of participants (72.7%) randomized within 3 days of hospitalization. In this trial, at least 1 unit of convalescent plasma was administered with SARS-CoV-2 antibody titers of 8 or greater (measured via the Euroimmun assay) in 56.6% of participants and antibody titers of 6 or greater in 99% of participants for whom data were available (eTable 9 in Supplement 2), which represents higher antibody titers than the Emergency Use Authorization recommendation (≥3.5) by the US Food and Drug Administration.27

Limitations

This trial has several limitations. First, it used an open-label design; however, clinician and patient awareness of trial assignment likely had minimal effect on ascertaining the primary outcome.

Second, 85.6% of participants received convalescent plasma in the intervention group per protocol and 0.6% of patients in the no convalescent plasma (control) group received convalescent plasma; however, this is unlikely to have biased the results toward the null because the per-protocol analyses were similar to the primary analysis.

Third, although most participants received very high–titer convalescent plasma, which has a linear relationship to viral neutralization, the treatment properties of viral neutralization were not measured prior to convalescent plasma administration.

Fourth, the trial has only been able to test the potential effectiveness of convalescent plasma in critically ill patients and it remains possible that convalescent plasma or other high-titer, antibody-based therapy (alone or in combination with antiviral chemotherapy) may have a therapeutic effect earlier in the disease process or in some patient subgroups.

Fifth, the trial did not collect data on time since symptom onset and only collected data on time from hospitalization.

Sixth, the trial was unable to recruit participants in the US to the no convalescent plasma group due to the Expanded Use Authorization by the US Food and Drug Administration, which also led to low levels of recruitment in that country.

Conclusions

Among critically ill adults with confirmed COVID-19, treatment with 2 units of high-titer, ABO-compatible convalescent plasma had a low likelihood of providing improvement in the number of organ support–free days.

Section Editor: Christopher Seymour, MD, Associate Editor, JAMA (christopher.seymour@jamanetwork.org).

Trial protocol and statistical analysis plan

eMethods

eFigure 1. Unadjusted analysis of organ support free days by intervention and stratified by state

eFigure 2. Meta-analysis of in-hospital or 28-day survival stratified by SARS-CoV-2 antibody response

eTable 1. Participant characteristics at baseline

eTable 2. Participant characteristics at baseline in the immunosuppressed sub-group

eTable 3. Randomization into other unblinded domains

eTable 4. Interactions with other domains

eTable 5. Primary and secondary analyses of primary outcomes

eTable 6. Secondary outcomes

eTable 7. Serious adverse events

eTable 8. Sensitivity analyses to primary outcomes

eTable 9. Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing of convalescent plasma provided to the REMAP-CAP trial in Australia, Canada, United Kingdom and United States

eReferences

eAppendix. REMAP-CAP investigators and committees

Statistical analysis committee primary outcome analysis report

ITSC secondary analysis report

REMAP-CAP Collaborators

Data sharing agreement

References

- 1.Gupta A, Madhavan MV, Sehgal K, et al. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(7):1017-1032. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0968-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rochwerg B, Agarwal A, Siemieniuk RA, et al. A living WHO guideline on drugs for COVID-19. BMJ. 2020;370:m3379. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angus DC, Derde L, Al-Beidh F, et al. ; Writing Committee for the REMAP-CAP Investigators . Effect of hydrocortisone on mortality and organ support in patients with severe COVID-19: the REMAP-CAP COVID-19 corticosteroid domain randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324(13):1317-1329. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon AC, Mouncey PR, Al-Beidh F, et al. ; REMAP-CAP Investigators . Interleukin-6 receptor antagonists in critically ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(16):1491-1502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2100433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sterne JAC, Murthy S, Diaz JV, et al. ; WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group . Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324(13):1330-1341. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloch EM, Shoham S, Casadevall A, et al. Deployment of convalescent plasma for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(6):2757-2765. doi: 10.1172/JCI138745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luke TC, Kilbane EM, Jackson JL, Hoffman SL. Meta-analysis: convalescent blood products for Spanish influenza pneumonia: a future H5N1 treatment? Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(8):599-609. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-8-200610170-00139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mair-Jenkins J, Saavedra-Campos M, Baillie JK, et al. ; Convalescent Plasma Study Group . The effectiveness of convalescent plasma and hyperimmune immunoglobulin for the treatment of severe acute respiratory infections of viral etiology: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2015;211(1):80-90. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casadevall A, Pirofski L-A. The convalescent sera option for containing COVID-19. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(4):1545-1548. doi: 10.1172/JCI138003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gutmann C, Takov K, Burnap SA, et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia and proteomic trajectories inform prognostication in COVID-19 patients admitted to intensive care. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):3406. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23494-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bermejo-Martin JF, González-Rivera M, Almansa R, et al. Viral RNA load in plasma is associated with critical illness and a dysregulated host response in COVID-19. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):691. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03398-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamel H. We stand ready … blood collection organizations and the COVID-19 pandemic. Transfusion. 2021;61(5):1345-1349. doi: 10.1111/trf.16400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.RECOVERY Collaborative Group . Convalescent plasma in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a randomised controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10289):2049-2059. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00897-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piechotta V, Iannizzi C, Chai KL, et al. Convalescent plasma or hyperimmune immunoglobulin for people with COVID-19: a living systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;5(5):CD013600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janiaud P, Axfors C, Schmitt AM, et al. Association of convalescent plasma treatment with clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2021;325(12):1185-1195. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.2747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Angus DC, Berry S, Lewis RJ, et al. The REMAP-CAP (Randomized, Embedded, Multifactorial, Adaptive Platform for Community-Acquired Pneumonia) study: rationale and design. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(7):879-891. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-192SD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.REMAP-CAP Investigators, ACTIV-4a Investigators, ATTACC Investigators, et al. Therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin in critically ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(9):777-789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ATTACC Investigators, ACTIV-4a Investigators, REMAP-CAP Investigators, et al. Therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin in noncritically ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(9):790-802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization . COVID-19 clinical management: living guidance. Accessed September 25, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-clinical-2021-1

- 20.RECOVERY trial . RECOVERY trial closes recruitment to convalescent plasma treatment for patients hospitalised with COVID-19. Accessed June 15, 2021. https://www.recoverytrial.net/news/statement-from-the-recovery-trial-chief-investigators-15-january-2021-recovery-trial-closes-recruitment-to-convalescent-plasma-treatment-for-patients-hospitalised-with-covid-19

- 21.RECOVERY Collaborative Group . Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):693-704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Libster R, Pérez Marc G, Wappner D, et al. ; Fundación INFANT–COVID-19 Group . Early high-titer plasma therapy to prevent severe Covid-19 in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(7):610-618. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2033700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laing AG, Lorenc A, Del Molino Del Barrio I, et al. A dynamic COVID-19 immune signature includes associations with poor prognosis. Nat Med. 2020;26(10):1623-1635. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1038-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathew D, Giles JR, Baxter AE, et al. ; UPenn COVID Processing Unit . Deep immune profiling of COVID-19 patients reveals distinct immunotypes with therapeutic implications. Science. 2020;369(6508):eabc8511. doi: 10.1126/science.abc8511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ratcliff J, Nguyen D, Fish M, et al. Virological characterization of critically ill patients with COVID-19 in the United Kingdom: interactions of viral load, antibody status, and B.1.1.7 infection. J Infect Dis. 2021;224(4):595-605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seow J, Graham C, Merrick B, et al. Longitudinal observation and decline of neutralizing antibody responses in the three months following SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(12):1598-1607. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-00813-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.US Food and Drug Administration . Convalescent plasma Emergency Use Authorization letter. Published March 9, 2021. Accessed June 15, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/141477/download

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol and statistical analysis plan

eMethods

eFigure 1. Unadjusted analysis of organ support free days by intervention and stratified by state

eFigure 2. Meta-analysis of in-hospital or 28-day survival stratified by SARS-CoV-2 antibody response

eTable 1. Participant characteristics at baseline

eTable 2. Participant characteristics at baseline in the immunosuppressed sub-group

eTable 3. Randomization into other unblinded domains

eTable 4. Interactions with other domains

eTable 5. Primary and secondary analyses of primary outcomes

eTable 6. Secondary outcomes

eTable 7. Serious adverse events

eTable 8. Sensitivity analyses to primary outcomes

eTable 9. Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing of convalescent plasma provided to the REMAP-CAP trial in Australia, Canada, United Kingdom and United States

eReferences

eAppendix. REMAP-CAP investigators and committees

Statistical analysis committee primary outcome analysis report

ITSC secondary analysis report

REMAP-CAP Collaborators

Data sharing agreement