Abstract

The radionuclide 213Bi can be applied for targeted α therapy (TAT), a type of nuclear medicine that harnesses α particles to eradicate cancer cells. To use this radionuclide for this application, a bifunctional chelator (BFC) is needed to attach it to a biological targeting vector that can deliver it selectively to cancer cells. Here, we investigated six macrocyclic ligands as potential BFCs, fully characterizing the Bi3+ complexes by NMR spectroscopy, mass spectrometry, and elemental analysis. Solid-state structures of three complexes revealed distorted coordination geometries about the Bi3+ center arising from the stereochemically active 6s2 lone pair. The kinetic properties of the Bi3+ complexes were assessed by challenging them with a 1000-fold excess of the chelating agent diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA). The most kinetically inert complexes contained the most basic pendent donors. Density functional theory (DFT) and quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAIM) calculations were employed to investigate this trend, suggesting that the kinetic inertness is not correlated with the extent of the 6s2 lone pair stereochemical activity, but with the extent of covalency between pendent donors. Lastly, radiolabeling studies of 213Bi (30–210 kBq) with three of the most promising ligands showed rapid formation of the radiolabeled complexes at room temperature within 8 min for ligand concentrations as low as 10−7 M, corresponding to radiochemical yields of > 80% thereby demonstrating the promise of this ligand class for use in 213Bi TAT.

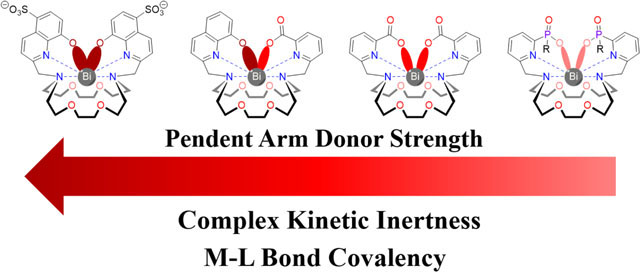

Graphical Abstract

A series of 18-membered macrocyclic ligands is investigated for Bi3+ chelation. These ligands show promising affinity for this main group ion and are demonstrated to effectively radiolabel its therapeutic radioisotope, 213Bi.

Introduction

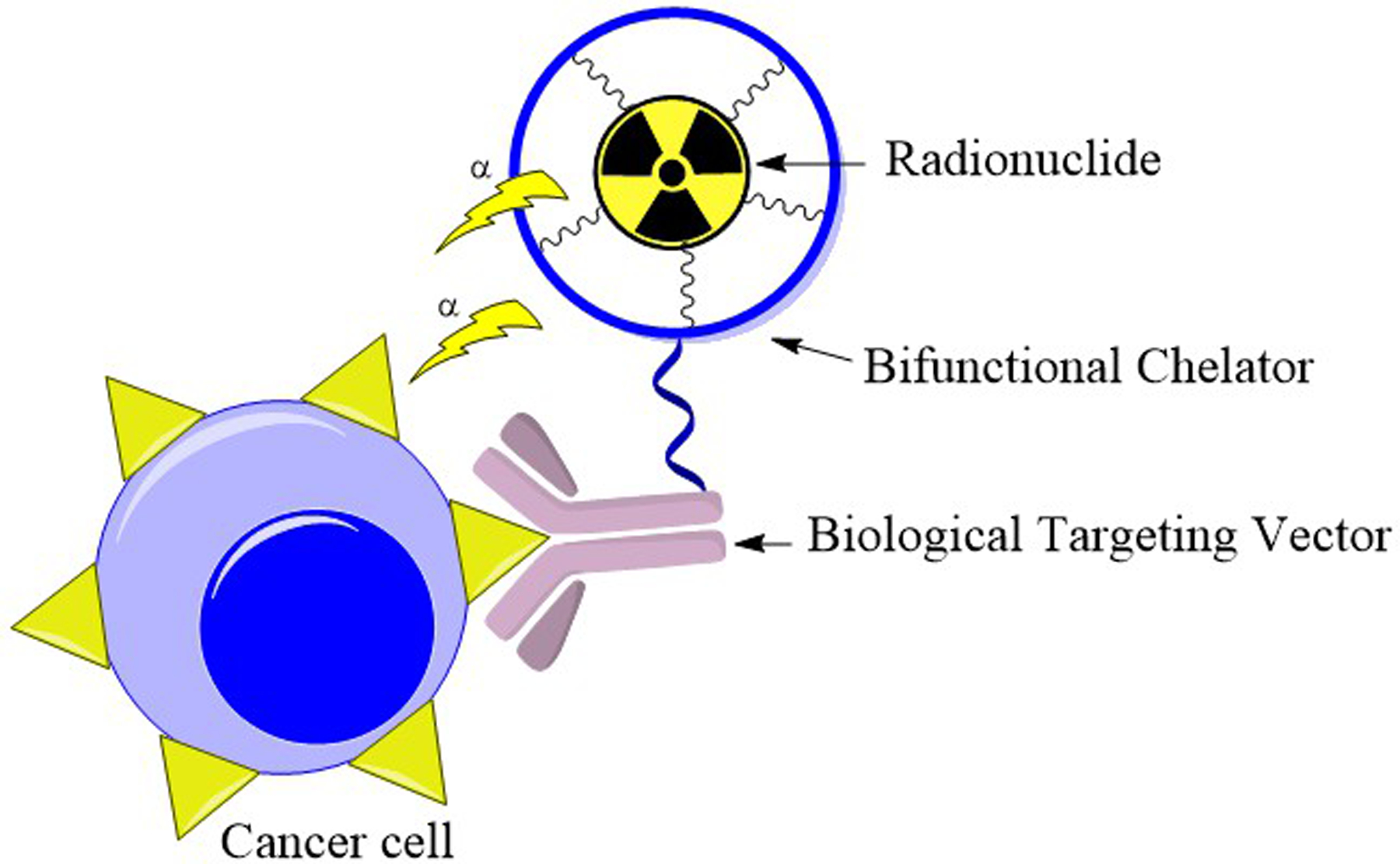

Targeted α therapy (TAT) is a promising approach for the treatment of cancer that employs an α-emitting radionuclide to deliver highly localized internal radiation to malignant cells.1–4 The high linear energy transfer and short penetration range in biological tissue of α particles make them well suited for internal radiotherapy because it ensures that the radiation is confined to a minimal area, thus limiting off-target damage.5 Directing these radionuclides to malignant tissue, however, requires attachment to an appropriate biological targeting agent, such as an antibody or peptide, that can selectively bind receptors overexpressed in cancer cells (Figure 1). A key component of these radiopharmaceutical agents is the bifunctional chelator (BFC) that covalently links the α-emitting radionuclide to the targeting vector.6 An effective BFC for radiopharmaceutical applications will form a thermodynamically stable and kinetically inert complex with the radiometal of interest within biological environments. In the context of TAT, finding a suitable BFC is hindered by the difficulty in forming stable complexes with appropriate α-emitters, which are generally isotopes of large metal ions near the bottom of the periodic table.7 The small charge density of these large α-emitters weakens the M–L interactions that stabilize their resulting coordination complexes, requiring ligand design separate from conventional methods for smaller metal ions and limiting progress towards the utilization of TAT.

Figure 1.

Schematic of TAT, demonstrating the role of the BFC in bridging the radiometal to the biological targeting vector.

The first and currently only FDA-approved α-emitting therapeutic agent, Xofigo®, is widely employed for the management of bone metastases within castration-resistant prostate cancer patients. This drug, administered as the uncomplexed salt [223Ra]RaCl2,8,9 capitalizes on the bone-mimetic properties of the free Ra2+ ion to localize to bone metastases.10 Although there has been some limited success in developing chelating agents for Ra2+ that would enable its use for treating other cancer types,11–15 the majority of TAT constructs under preclinical investigation are focused on other radionuclides. Among the most promising candidates for this application are 225Ac and its daughter 213Bi. For example, clinical studies on a prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA)-targeting 225Ac construct showed it to eliminate nearly all metastatic lesions in castration-resistant prostate cancer patients.16 Despite the promising therapeutic properties of this radionuclide, there remain some concerns regarding the ability to produce it on a large enough scale with sufficiently high radionuclidic purity to sustain clinical applications.17 The use of the daughter of 225Ac, 213Bi, may be advantageous in these regards as this radionuclide can conveniently be isolated from 225Ac/213Bi generators with high purity.18–21 Furthermore, the shorter half-life of 213Bi (t1/2 = 45.6 min) may be favorable for some applications that involve a fast-clearing biological targeting vector and is also beneficial with respect to minimizing the redistribution of toxic daughter nuclides due to the alpha recoil effect. These promising features of 213Bi have led to several clinical trials using this radionuclide for cancer treatment.22–26

To date, there have been numerous efforts to develop an ideal BFC for 213Bi,27–47 with varying degrees of success. Two widespread ligand design strategies for 213Bi chelation focus on derivatives of the macrocyclic ligand 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclodecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTA) and the analogue of diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) with a rigidified backbone (CHX-DTPA) (Chart 1).24,26,28,48,49 These types of ligands form 213Bi complexes with good in vivo stability and high molar activities. However, macrocyclic ligands based on DOTA typically require elevated temperatures for efficient radiolabeling.50 Furthermore, acyclic chelators, like DTPA and CHX-DTPA, tend to form less inert complexes in vivo. It should be noted, however, that CHX-DTPA shows much greater inertness compared to DTPA, a feature that has facilitated its use for in vivo studies.22,26,48,51–55

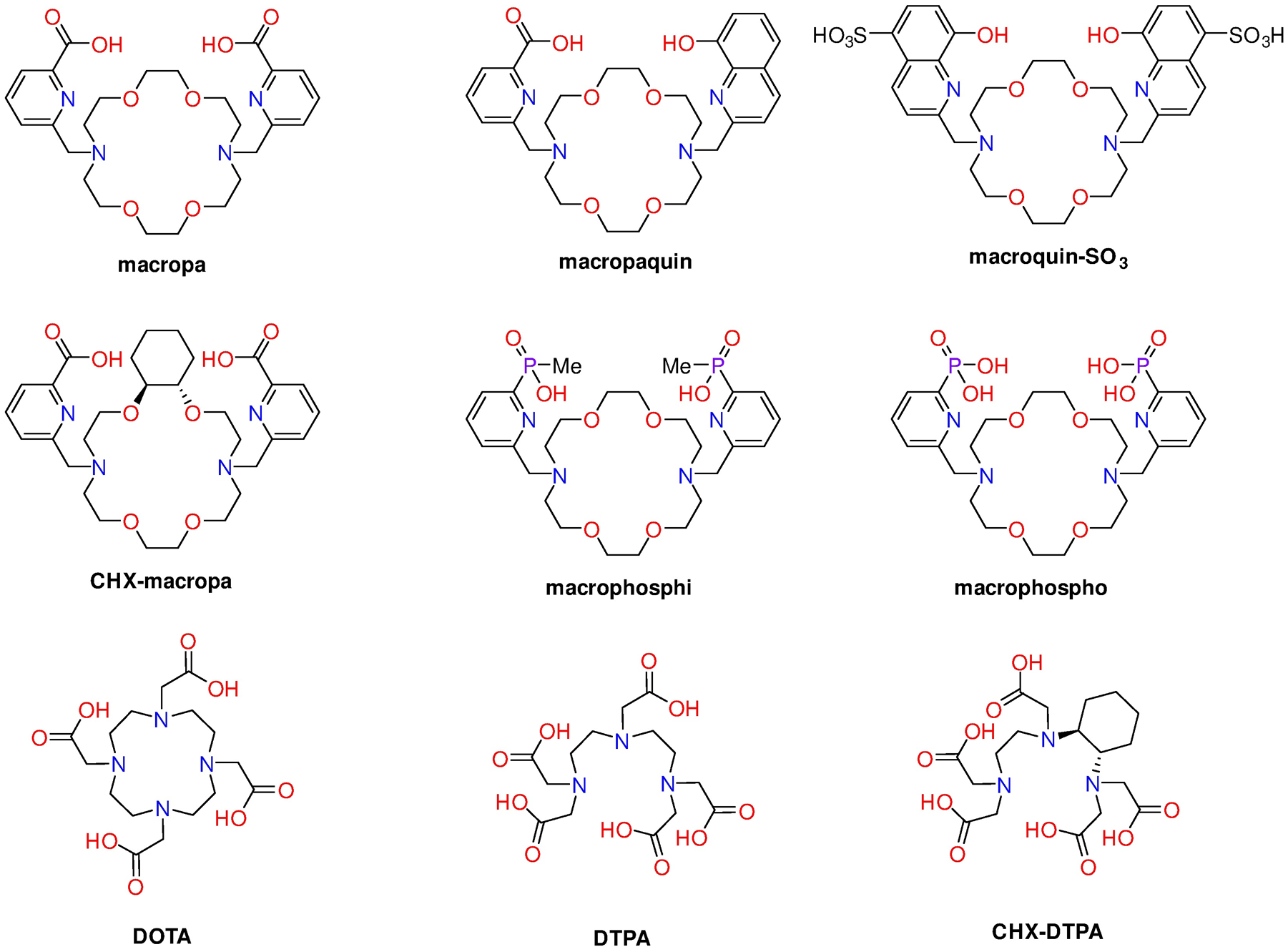

Chart 1.

Ligands discussed in this work.

A common feature of both DOTA and CHX-DTPA, as well as the many other chelators that have been explored for 213Bi, is their thermodynamic preference for small over large metal ions. Residing far down in the periodic table, Bi3+ has an ionic radius (0.96–0.99 Å for coordination number of six)56,57 that is significantly larger than those of other +3 radiometals that have been chelated with these ligands. As such, we reasoned that investigating chelators with a reverse size-selectivity, a preference for large over small ions, would be a promising direction for the development of new BFCs for this radionuclide. In this context, ligands containing the 18-membered diaza-18-crown-6 macrocycle display this reverse size-selective property for metal ions.58–66 Previously we have shown that macropa (Chart 1) forms remarkably stable complexes with large medicinally relevant radiometals like 132/135La, 223Ra, and 225Ac.11,67,68 We have further shown that altering the pendent donor arms and macrocyclic core rigidity changes the resulting selectivity for different metal ions.59,60,69 Based on the reverse size-selectivity properties and tunability of this system, we sought to explore this class of ligands (Chart 1) for chelating Bi3+ for potential applications in TAT.

Results and Discussion.

Ligand synthesis and characterization.

The ligands investigated, macropa, CHX-macropa, macropaquin, macroquin-SO3, macrophosphi, and macrophospho (Chart 1), feature varied macrocycle rigidity and pendent donor basicity, enabling us to investigate the roles of these variables on Bi3+ coordination. All of these ligands, except for macrophospho, have been previously reported and were synthesized following established procedures.58,59,69 Macrophospho, which bears two pyridyl-2-phosphonic acid pendent arms, was synthesized following an approach that was used to obtain macrophosphi (Scheme 1).69

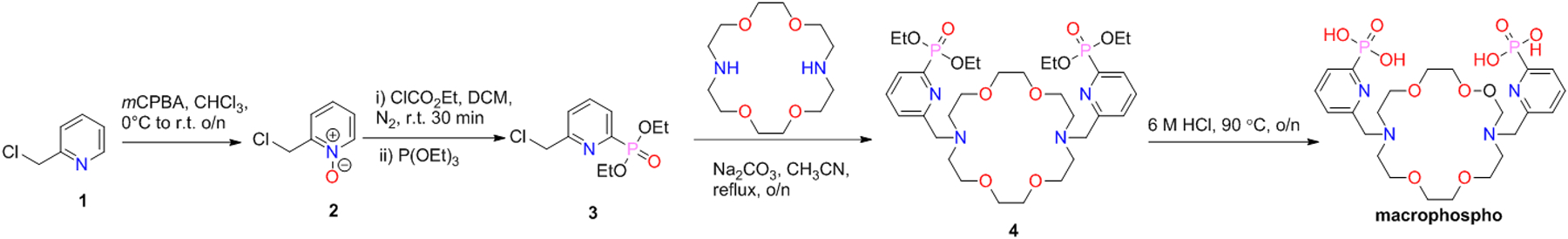

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of macrophospho

The synthesis of the pendent donor arm intermediate 3 commenced from 2-(chloromethyl)pyridine-1-oxide (2), which could be prepared on a multigram scale in high yield by treating 2-chloromethylpyridine with meta-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (mCPBA).70 Subsequently, the resulting pyridine-N-oxide 2 was activated towards an Arbuzov-type reaction71,72 with ethyl chloroformate, and then treated in the same pot with triethyl phosphite to install the phosphonate ethyl ester. Compound 3 was isolated in 50–60% yield after sequential purification by both vacuum distillation and flash column chromatography. The alkylation of diaza-18-crown-6 with 3 in acetonitrile at reflux proceeded smoothly, resulting in the formation of 4 as a yellow oil. Compound 4, which was carried forward in the synthesis without additional purification, was hydrolyzed with 6 M HCl to remove the ethyl ester groups. The resulting product was purified by reverse-phase preparative high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and then repeatedly dissolved in 6 M HCl and concentrated to dryness under vacuum to afford macrophospho as the hydrochloride salt. This ligand was fully characterized by 1H, 13C{1H}, and 31P{1H} NMR spectroscopy, analytical HPLC, high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), and elemental analysis (Figures S1–S6).

The protonation constants for macrophospho were determined via potentiometric titration, and are collected in Table 1, along with those for other diaza-18-crown-6-based ligands. The four most basic protonation constants of macrophospho most likely correspond to the tertiary amine nitrogens and one phosphonate oxygen on each pendent arm. We assign the two most basic protonation constants (log K 8.68 and 7.82) to tertiary amine nitrogens based on comparison to the analogous protonation constants for ligands such as macropa and macrophosphi, which also range from 7–8 (Table 1). A sixth protonation constant, which would belong to the last oxygen atom group, was too acidic to be measured via our potentiometric titration setup. The protonation constants of the phosphonates are lower than those of the other pendent donors, consistent with the higher acidity of this functional group. In particular, the comparison between macrophosphi and macrophospo show the that the most acidic protonation constant of the latter ligand is almost half a log unit lower. The greater acidity of phosphonates compared to phosphinates has been previously found in other ligand systems.73

Table 1.

Protonation Constants for Investigated Ligands Determined via pH Potentiometry (25 °C and I = 0.1 M KCl)

Bi3+ Complex Synthesis and Characterization.

To evaluate the Bi3+ coordination chemistry of these ligands, we synthesized the complexes by adding Bi(NO3)3·5H2O to an aqueous solution of the ligand. After 30 min of stirring at room temperature, the pH of the resulting white suspension was adjusted from ≈1.5 to 4 with 2 M KOH, and then heated at 90 °C overnight. The Bi3+ complexes were isolated from this reaction mixture after filtration through a 0.20 μm nylon membrane and purification by reverse-phase HPLC. Notably, the mobile phase of this purification step employed 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), highlighting the high stabilities of the complexes under acidic conditions. All six Bi3+ complexes were characterized by multinuclear NMR spectroscopy, HRMS, and elemental analysis (Figures S7–S41). HRMS for all complexes revealed the presence of the characteristic m/z molecular ion peak for the [M]+ species, and elemental analysis was consistent with the overall empirical formulae of these structures. Quantitative 1H and 19F NMR spectroscopy was used as a further verification of the average number of TFA molecules per complex. Elemental analysis and quantitative NMR methods revealed non-integer quantities of TFA molecules for some of the ligands, reflecting them to be potentially isolated as a mixture of different protonation states. The mass of TFA present in these samples was taken into consideration for subsequent studies that required precise molecular weights of these ligands.

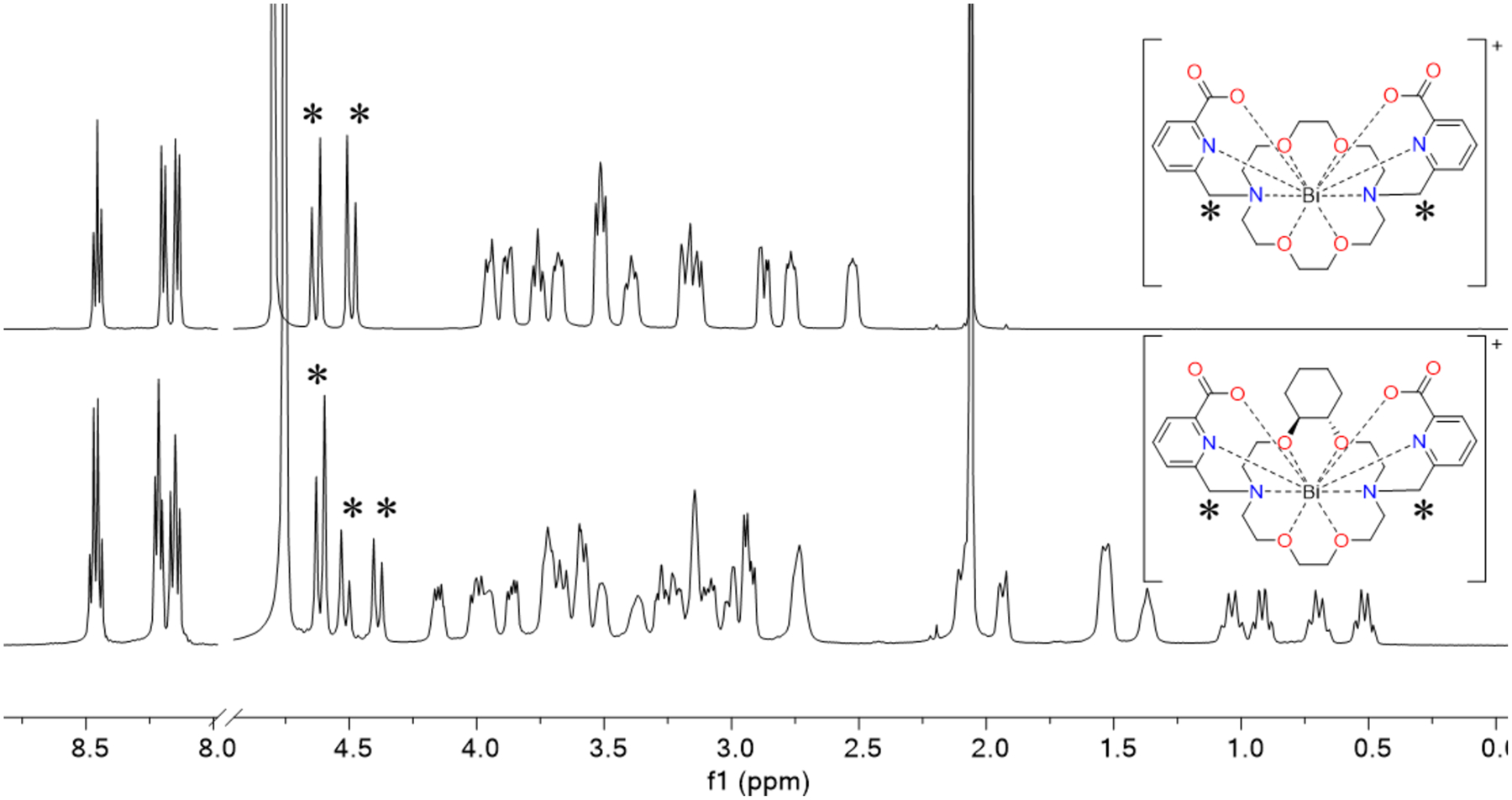

The 1H and 13C{1H} NMR spectra of the complexes were acquired in D2O or DMSO-d6 to characterize their solution properties. Coordination to the Bi3+ ion is confirmed by the presence of diastereotopic splitting of the methylene protons on the pendent arms and protons on the macrocyclic core. For [Bi(macropa)]+, [Bi(macrophospho)]+, [Bi(macrophosphi)]+, and [Bi(macroquin-SO3)]−, these NMR spectra indicate that the complexes attain C2 symmetry in solution, as reflected by the chemical equivalencies of the pendent donor groups. By contrast, [Bi(CHX-macropa)]+ and [Bi(macropaquin)]+ reveal asymmetric NMR spectra with discrete aromatic resonances corresponding to chemically distinct pendent donor groups (Figure 2). Distinct resonances are also observed for their associated methylenic linker protons. The lack of symmetry of these complexes suggests that the solution-state structure of all complexes involves conformations with both pendent arms on the same side of the macrocycle, similar to the solid-state structures for the Ln3+ and Ba2+ complexes.59,67 Such a conformation has C2 symmetry only when the pendent arms are identical, whereas different pendent arms results in a complex bearing C1 symmetry, consistent with the NMR data.

Figure 2.

1H NMR spectra (500 MHz, 298 K, D2O) of [Bi(macropa)]+ (top) and [Bi(CHX-macropa)]+ (bottom), demonstrating C2 or C1 symmetry, respectively. The diagnostic aliphatic resonances marked by asterisks for each corresponds to the similarly marked methylene arm linker protons.

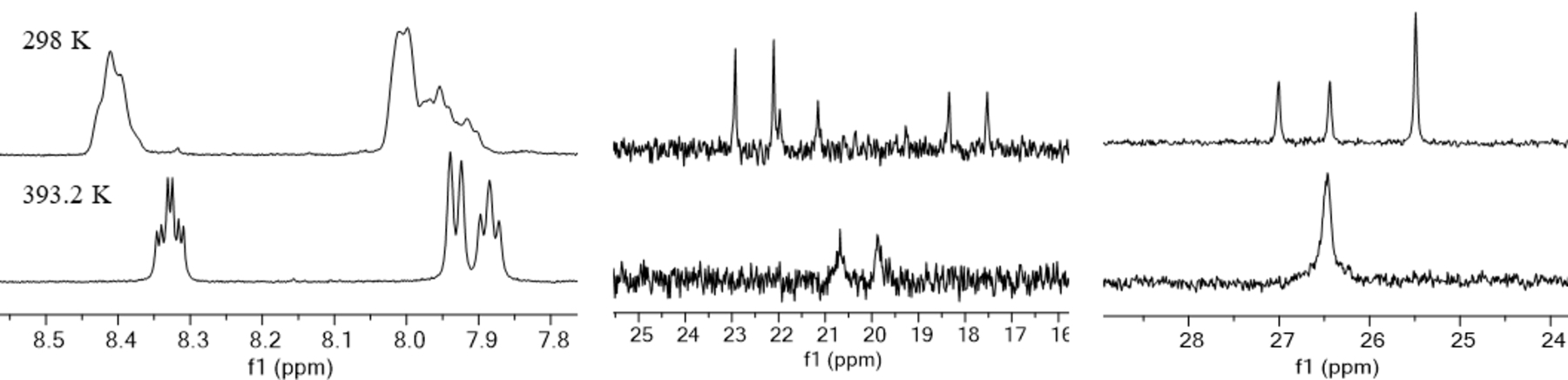

Additionally, the NMR spectra of [Bi(macrophosphi)]+ at room temperature show two species. The room temperature 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of this complex displayed three resonances in a 1:1:2 ratio (Figure 3). Upon heating this solution to 120 °C in DMSO-d6, the peaks coalesce to a single resonance at 26.47 ppm. This 1:1:2 ratio shows three separate environments for four phosphorus atoms, consistent with the presence of a symmetric and asymmetric diastereomer of the complex with different pendent arm conformations. At elevated temperature, the interconversion of the diastereomers is rapid, resulting in coalescence of the peaks in the NMR spectra. Similarly, the 13C{1H} NMR spectrum of this complex displays three doublets for the phosphinate methyl group at room temperature that coalesce into a single doublet upon heating to 120 °C, and the aromatic region of 1H NMR spectrum also converges to a clean single-set of resonances at this temperature. These data corroborate our prior observations on the La3+ complex of this ligand.69 Upon metal coordination, the phosphorus atoms become chiral, and thus two diastereomeric forms of the complex are possible. At higher temperatures, racemization occurs at a fast rate, giving rise to an averaged NMR spectrum.

Figure 3.

1H (left, 500 MHz), 13C{1H} (middle, 126 MHz), and 31P{1H} (right, 202 MHz) NMR spectra of [Bi(macrophosphi)]+ in DMSO-d6 at 298 K (top) and 393.2 K (bottom).

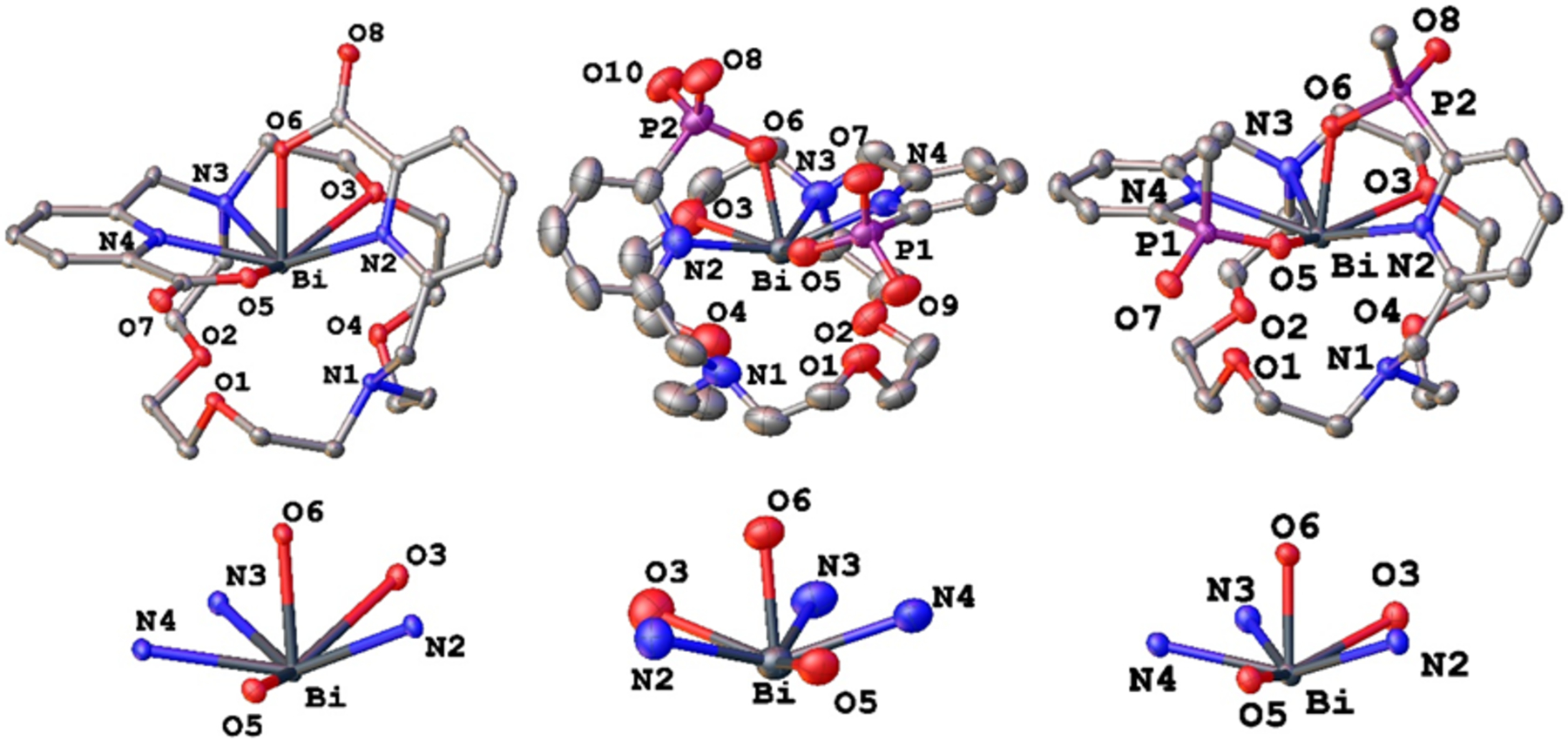

The solid state structures of [Bi(macropa)]+, [Bi(macrophospho)]+, and [Bi(macrophosphi)]+ were determined by X-ray diffraction (Figure 4). In contrast to their symmetric NMR spectra, these structures reveal an anisotropic coordination environment about the Bi3+ center. This difference between solid- and solution-state structures is most likely a consequence of stereochemical non-rigidity of the complex, which leads to time-averaged NMR spectra. The crystal structure of [Bi(macrophosphi)]+ exhibits disorder about the methyl group and oxygen atom of one of the pendent phosphinate donors, reflecting the different diastereomers that were observed by NMR spectroscopy. Interatomic distances between the Bi3+ atom and ligand donor atoms are given in Table 2. In contrast to previously reported Lu3+, La3+, and Ba2+ crystal structures of ligands of this type, the Bi3+ center does not equally interact with all donors of the macrocycle. Two of the Bi–macrocycle donor interactions (Bi–N3 and Bi–O3) are significantly shorter than those between the other 4 donor atoms (N1, O2, O4). Across the three complexes, the Bi–N3 distances span values of 2.668, 2.666, and 2.659 Å, and the Bi–O3 separations are 2.7541, 2.740, and 2.669 Å for [Bi(macropa)]+, [Bi(macrophospho)]+, and [Bi(macrophosphi)]+, respectively. The other macrocycle donor atom–Bi distances for all three complexes are greater than 2.85 Å, suggesting that only weak interactions are present. By contrast, the Bi–pendent donor atom distances are substantially shorter. The pyridyl nitrogen–Bi (Bi–N2 and Bi–N4) distances are less than 2.57 Å in all three complexes, potentially reflecting a much stronger interaction than those with the nitrogen atoms of the macrocycle. Furthermore, the Bi–O (Bi–O5 and Bi–O6) distances within all three complexes are between 2.2 and 2.3 Å, signifying a particularly strong interaction. For comparison, the Bi–O distances for the carboxylate donors within [Bi(DTPA)]2− and [Bi(DOTA)]− are longer at the 2.3–2.5 Å range.74,75 Although a definitive coordination number is difficult to obtain, we propose that these structures can be best described as six-coordinate with the Bi centers displaying distorted pentagonal pyramidal geometries. Thus, the coordination environment consists of the two short Bi–macrocycle interactions, between N3 and O3, and the four Bi–pendent donor atom interactions. The pentagonal pyramidal geometry would originate from the presence of the 6s2 stereochemically active lone pair, which following VSEPR theory considerations, would be predicted to occupy the axial position of an ideal pentagonal bipyramid. Because a well-known impact of the stereochemically active lone pair is to shorten interatomic distances on the side opposite to it,76 it is informative to compare the Bi–O6 and Bi–O5 separations within the three complexes. The distances between Bi and O6, the donor atom that occupies the axial position of the pentagonal pyramid, are 2.2316, 2.212, and 2.216 Å for [Bi(macropa)]+, [Bi(macrophospho)]+, and [Bi(macrophosphi)]+, respectively, whereas the Bi–O5 distances are somewhat longer at 2.2577, 2.232. and 2.254 Å. These data therefore support our proposed pentagonal pyramidal geometry and the directionality of the stereochemically active 6s2 lone pair.

Figure 4.

X-ray crystal structures of [Bi(macropa)](NO3)·dioxane (top left), [Bi(macrophospho)](TFA)·H2O (top middle), and [Bi(macrophosphi)](TFA)·H2O (top right) complexes. Ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level. Hydrogen atoms, counteranions, and solvent molecules are excluded for clarity. The six donor atoms that comprise the pentagonal pyramidal coordination sphere of the Bi3+ are shown below each structure.

Table 2.

Interatomic Distances (Å) Involving Bia

| Bond | [Bi(macropa)]+ | [Bi(macrophospho)]+ | [Bi(macrophosphi)]+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bi–O1 | 2.987(2) | 2.960(3) | 2.909(2) |

| Bi–O2 | 2.895(2) | 2.934(4) | 2.868(2) |

| Bi–O3 | 2.7541(17) | 2.740(4) | 2.669(2) |

| Bi–O4 | 3.048(2) | 3.259(4) | 3.257(3) |

| Bi–O5 | 2.2577(16) | 2.232(3) | 2.254(2) |

| Bi–O6 | 2.2316(17) | 2.212(3) | 2.216(2) |

| Bi–N1 | 2.930(3) | 2.992(5) | 3.014(4) |

| Bi–N2 | 2.4419(19) | 2.538(4) | 2.566(3) |

| Bi–N3 | 2.688(2) | 2.666(4) | 2.659(3) |

| Bi–N4 | 2.413(2) | 2.434(4) | 2.442(3) |

Atoms are labeled as shown in Figure 4. The values in the parentheses are one standard deviation of the last significant figure(s).

The SHAPE program77 was further used to validate our assignment of the coordination polyhedra of the Bi3+ center for these three complexes (Table S2). Among the various ideal six-coordinate polyhedra, two geometries better matched to the experimental coordination geometries from substantially smaller continuous shape measures (CSMs). These CSMs, a quantitative measure of the match of an experimental coordination geometry to an idealized polyhedron, range from 1–4 for the Johnson pentagonal pyramid and the pentagonal pyramid. The CSMs for all other ideal polyhedra are significantly larger, on the order of 20–30, indicating that they describe the experimental geometries much more poorly. Notably, [Bi(macropa)]+, [Bi(macrophospho)]+, and [Bi(macrophosphi)]+ have immediate coordination spheres that match the Johnson pentagonal pyramid slightly better than the pentagonal pyramid. The difference between these two geometries is the ratio of the distance of the axial vertex to the equatorial plane to the distance between two equatorial vertices, with the Johnson pentagonal pyramid having a smaller ratio. This closer match to the Johnson pentagonal pyramid is most likely due to a combination of the O6–Bi–Lequatorial angles being less than 90° as well as the aforementioned shortened Bi–O6 bond length. Both such effects, the shortened axial bond length and contracted bond angles, support our proposal that the stereochemically active lone pair resides opposite to the axial oxygen atom.

Evaluation of the Kinetic Properties of Bi3+ Complexes.

To effectively use BFCs in nuclear medicine, they need to form kinetically inert complexes. To probe the kinetic inertness of each of the six Bi3+ complexes, we challenged them with a 1000-fold excess of the high-affinity chelator DTPA in an aqueous solution buffered at pH 7.4 with 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS). Based on the large thermodynamic affinity and significant excess of DTPA, these conditions should favor transchelation of the Bi3+ ion from our macrocyclic ligands to DTPA. The kinetics of this process were monitored by UV-visible spectroscopy (Figures S42–S47), allowing for the pseudo first-order half-life of this transchelation to be obtained. After spectral changes were no longer observed, the solution was analyzed by HPLC, revealing the presence of either only free ligand or the starting complex.

The half-lives measured under these conditions are collected in Table 3. Apparent from these data, the rate of transchelation varies significantly depending on the macrocyclic ligand. The most labile complexes are [Bi(macrophospho)]+ and [Bi(macrophosphi)]+, with dissociation half-lives of <10 and 1 min, respectively. The picolinate-bearing complexes [Bi(CHX-macropa)]+ and [Bi(macropa)]+ exhibit similar kinetic lability; both ligands possess half-lives near 40 min. The introduction of an 8-hydroxyquinolinate arm in the [Bi(macropaquin)]+ complex increased the half-life to 14 h, marking a significant enhancement of kinetic inertness. Remarkably, [Bi(macroquin-SO3)]−, which contains two 8-hydroxyquinolinate-based pendent arms, does not show any spectral changes over a 21-d time period, demonstrating excellent kinetic inertness.

Table 3.

Half-Lives of Bi3+ Complexes in the Presence of 1000× Excess DTPA at pH 7.4.

| Complex | Half-life |

|---|---|

| [Bi(macrophosphi)]+ | < 1 min |

| [Bi(macrophopho)]+ | 8.9 ± 1.7 min |

| [Bi(CHX-macropa)]+ | 40.4 ± 4.3 min |

| [Bi(macropa)]+ | 46.6 ± 0.9 min |

| [Bi(macropaquin)]+ | 14.3 ± 1.4 h |

| [Bi(macroquin-SO3)]− | > 21 d |

In comparing [Bi(CHX-macropa)]+ and [Bi(macropa)]+, which exhibit nearly identical decomplexation half-lives, the rigidity of the macrocycle does not significantly influence the complex inertness towards the DTPA challenges. By contrast, more significant inertness manifests with increasing pendent donor basicity. Macrophospho and macrophosphi, which possess the least basic pendent arms (oxygen donor pKa values of < 2), form the most labile complexes with Bi3+, whereas the ligands with the significantly more basic quinolinate donors, macropaquin and macroquin-SO3 (oxygen donor pKa values of 9–10), demonstrate the highest levels of kinetic inertness. Macropa and CHX-macropa, bearing carboxylate oxygen donors (pKa values of 2–3), show intermediate levels of kinetic inertness. The efficacy of macropaquin and macroquin-SO3 for stabilizing Bi3+ in this DTPA challenge contrasts our observations with other large labile metal ions. For example, macroquin-SO3 was previously found to be the poorest candidate for retaining Ba2+ under similar challenge conditions, whereas macropa was the most effective.59 Furthermore, the La3+ complex of macropa is kinetically inert for over 20 d when treated with DTPA under similar conditions.67 Considering that Bi3+ and La3+ have similar ionic radii, the relative lability of the [Bi(macropa)]+ complex is surprising and points to additional factors that are required to stabilize this main group ion.

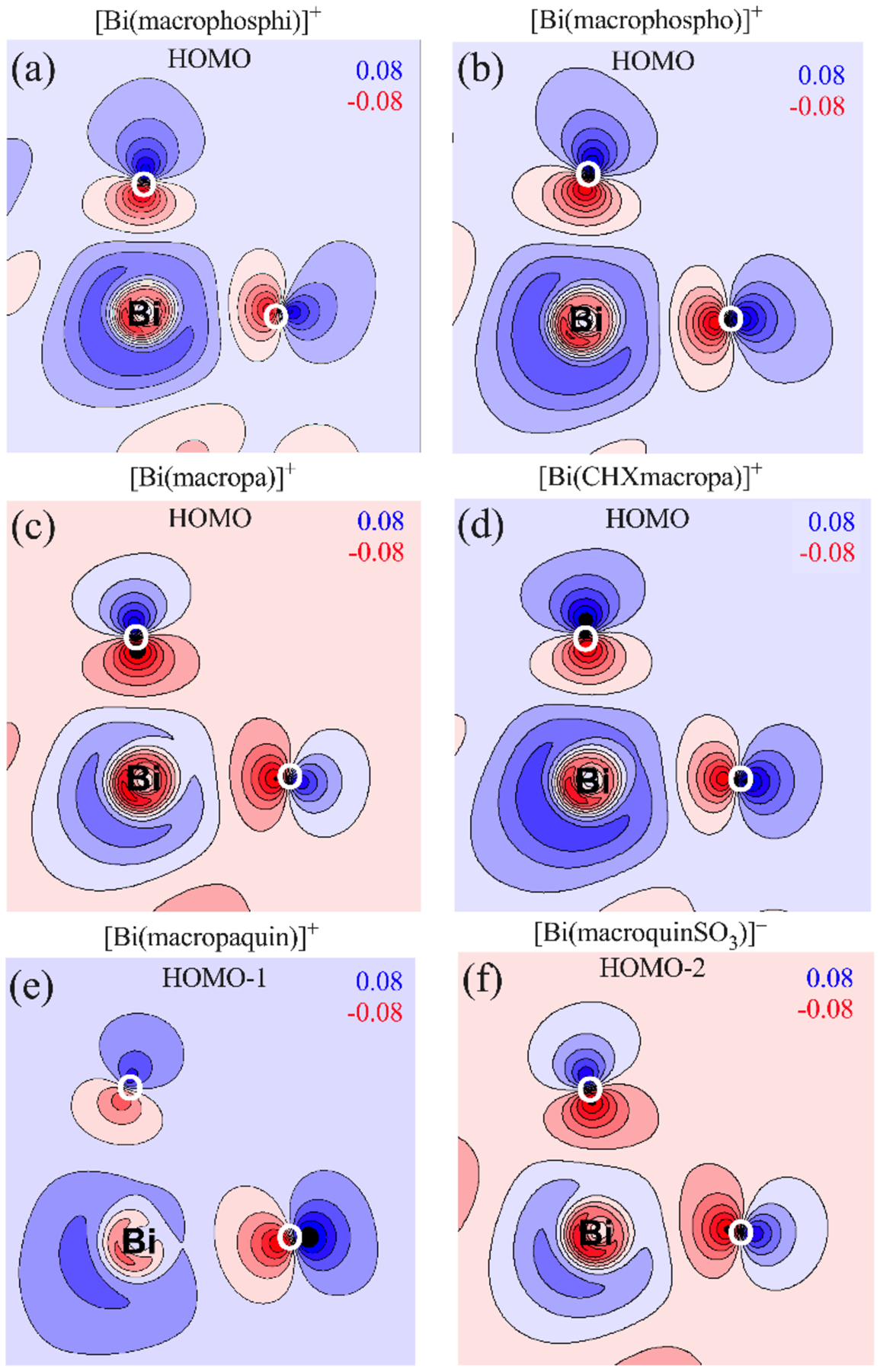

Computational Studies.

The origin of the differing kinetic properties of these complexes was investigated using density functional theory (DFT) calculations at the TPSSh level of theory.78 The Bi3+ atom was treated with the large core relativistic effective core potential (ECP60MDF)79 and related basis set, and the ligand atoms were described using the triple zeta valence potential (TZVP) basis set.80 We selected this computational approach based on previous studies that have demonstrated that this functional and effective core potential combination yield good results for Bi3+ complexes.39,46 Upon optimization, all six geometries converged to local minima with significant structural distortions about the central Bi3+ ion due to the presence of the stereochemically active lone pair. Notably, the DFT-optimized structures of [Bi(macropa)]+, [Bi(macrophospho)]+, and [Bi(macrophosphi)]+ compare favorably to those determined experimentally by X-ray crystallography with root-mean square differences (RMSDs) between these structures of 0.144, 0.218, and 0.233 Å, respectively. As discussed above, the Bi3+ complex of macropa is significantly less inert than those of macropaquin and macroquin-SO3, which is in contrast to that of the highly inert La3+ complex of macropa. We hypothesized that the stereochemical activity of the 6s2 lone pair in the Bi3+ complexes, a feature that is not present within the La3+ complex, may affect their relative kinetic labilities. The degree of stereochemical activity of the Bi3+ lone pair is a result of mixing between the 6s and 6p orbitals, which perturbs the spherical distribution of the 6s shell.81 The degree of 6p mixing was analyzed using a Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) analysis, which has proven useful for calculations dealing with stereochemical activity of the lone pair in Bi3+ and Pb2+ complexes.46,63,76,82–84 Each complex contains 1–2% 6p character, which agrees well with previous calculations on similar complexes (Table 4).46,84 Contour plots of the electron density of the molecular orbitals (MOs) containing significant (15–20%) Bi 6s2 contribution show that the lone pair extends away from the Bi3+ nucleus and towards the macrocyclic core (Figure 5). Contrary to our hypothesis, however, there is not a distinctive trend between the degree of 6p contribution and the kinetic lability of the Bi3+ complex (Table 3). This result suggests that the stereochemical activity of the lone pair is not the sole source of the differing kinetic labilities of these macrocyclic chelators with Bi.

Table 4.

NBO Analysis of the Bi3+ Lone Pair for [Bi(L)]+/− Complexes

| Complex | |

|---|---|

| [Bi(macrophosphi)]+ | s(98.79%) p(1.20%) |

| [Bi(macrophospho)]+ | s(98.74%) p(1.26%) |

| [Bi(CHX-macropa)]+ | s(98.14%) p(1.85%) |

| [Bi(macropa)]+ | s(98.10%) p(1.89%) |

| [Bi(macropaquin)]+ | s(98.05%) p(1.95%) |

| [Bi(macroquin-SO3)]− | s(98.19%) p(1.80%) |

Figure 5.

Contour plots of the electron density (e− Å−3) for the MOs containing significant Bi 6s2 contribution on the plane defined by the Bi3+ ion and the oxygen donor atoms of the pendent arms. (A) [Bi(macrophosphi)]+ HOMO, (B) [Bi(macrophospho)]+ HOMO, (C) [Bi(macropa)]+ HOMO, (D) [Bi(CHX-macropa)]+ HOMO, (E) [Bi(macropaquin)]+ HOMO–1, (F) [Bi(macroquin-SO3)]− HOMO–2. Values indicate maximum (blue) and minimum (red) electron density isovalues.

To further investigate the origin of the differing complex kinetic properties, we employed Bader’s quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAIM) analysis.85 This technique probes the topology of the electron density of complexes and has been used with great success to understand bonding in metal complexes.86,87 Within the QTAIM framework, the electron density, ρ(r), is divided into partitions represented by zero-flux surfaces, with the bond path between two atoms defined by the line of local maximum density. The intersection of the bond path and the zero-flux surface is defined as the bond critical point (BCP). Properties at the BCP, such as the electron density ρ(r), Laplacian of the electron density ∇2ρ(r), Lagrangian kinetic energy G(r), potential energy V(r), total energy density H(r), and delocalization index δ, describe the nature of the chemical interaction between two atoms. In the case of heavy elements, such as Bi, the ∇2ρ(r) may not properly describe the nature of metal-ligand bonding interactions.88,89 To avoid this issue, the energy density parameters V(r), G(r), and H(r), the ratio of potential and kinetic energies |V|/G, and the normalized total energy density H/ρ are commonly used to interpret the nature of bonding interactions in heavy metal complexes.90–95

Complete QTAIM results are compiled in Tables 5 and S3–S8. In agreement with our X-ray crystallographic and NBO analysis, the interactions of the Bi3+ center with the crown ether oxygen (O1–O4) and amine nitrogen (N1 and N3) atoms of the diaza-18-crown-6 core are almost purely ionic nature, as evidenced by the values of H(r) ≥ 0 and |V|/G < 1 (Table S3–S8). The interatomic interactions between the Bi center and the donor atoms of the pendent arms (O5, O6, N2, and N4) are more covalent, with values of H(r) < 0 and |V|/G > 1. The degree of covalency in these bonds can be analyzed by comparing the magnitude of the normalized energy density (H/ρ). Increased covalent character is reflected by more negative values of this parameter.91,92,96,97 As seen in Table 5, the covalency of the Bi–O and Bi–N bonds increases with the ligand basicity and agrees well with the trend in experimental kinetic properties of the chelators. A similar trend is observed for δ, which is an integral property that can be considered as a measure of covalent bond order.81,98

Table 5.

Selected QTAIM Metrics for Bi–Donor Interactions with the Ligand Pendent Arms in [Bi(L)]+/− Complexes. The Corresponding Units are ρ (e− Å−3), H/ρ (kJ/mol per e−), |V|/G (unitless), and δ (unitless)

| Complex | ρ(r) | H/ρ | |V|/G | δ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bi–O6a | Bi–O5 | Bi–O6 | Bi–O5 | Bi–O6 | Bi–O5 | Bi–O6 | Bi–O5 | |

| [Bi(macrophosphi)]+ | 0.0790 | 0.0816 | −481.7647 | −500.7658 | 1.1599 | 1.1648 | 0.9476 | 0.9708 |

| [Bi(macrophospho)]+ | 0.0718 | 0.0881 | −432.9824 | −540.2123 | 1.1495 | 1.1707 | 0.8771 | 0.9977 |

| [Bi(CHX-macropa)]+ | 0.0786 | 0.0776 | −502.2058 | −498.0826 | 1.1729 | 1.1724 | 0.9626 | 0.9523 |

| [Bi(macropa)]+ | 0.0778 | 0.0792 | −498.4372 | −506.3900 | 1.1724 | 1.1737 | 0.9526 | 0.9690 |

| [Bi(macropaquin)]+ | 0.0790 | 0.0797 | −503.1691 | −524.1951 | 1.1726 | 1.1820 | 0.9715 | 0.9831 |

| [Bi(macroquinSO3)]− | 0.0872 | 0.0872 | −579.2422 | −579.2698 | 1.2008 | 1.2008 | 1.0345 | 1.0345 |

| Complex | ρ(r) | H/ρ | |V|/G | δ | ||||

| Bi–N2 | Bi–N4 | Bi–N2 | Bi–N4 | Bi–N2 | Bi–N4 | Bi–N2 | Bi–N4 | |

| [Bi(macrophosphi)]+ | 0.0507 | 0.0416 | −350.5292 | −261.7623 | 1.1785 | 1.1398 | 0.6846 | 0.6054 |

| [Bi(macrophospho)]+ | 0.0476 | 0.0444 | −321.6876 | −291.0008 | 1.1654 | 1.1527 | 0.6499 | 0.6323 |

| [Bi(CHX-macropa)]+ | 0.0155 | 0.0322 | 234.3138 | −206.1312 | 0.8699 | 1.1323 | 0.2722 | 0.4715 |

| [Bi(macropa)]+ | 0.0566 | 0.0512 | −401.4145 | −353.3262 | 1.1957 | 1.1766 | 0.7238 | 0.6839 |

| [Bi(macropaquin)]+ | 0.0152 | 0.0263 | 301.8964 | −86.6741 | 0.8457 | 1.0523 | 0.2916 | 0.4341 |

| [Bi(macroquinSO3)]− | 0.0581 | 0.0581 | −407.7068 | −407.6882 | 1.2066 | 1.2066 | 0.7213 | 0.7213 |

Atom numbering scheme is shown in Figure S48.

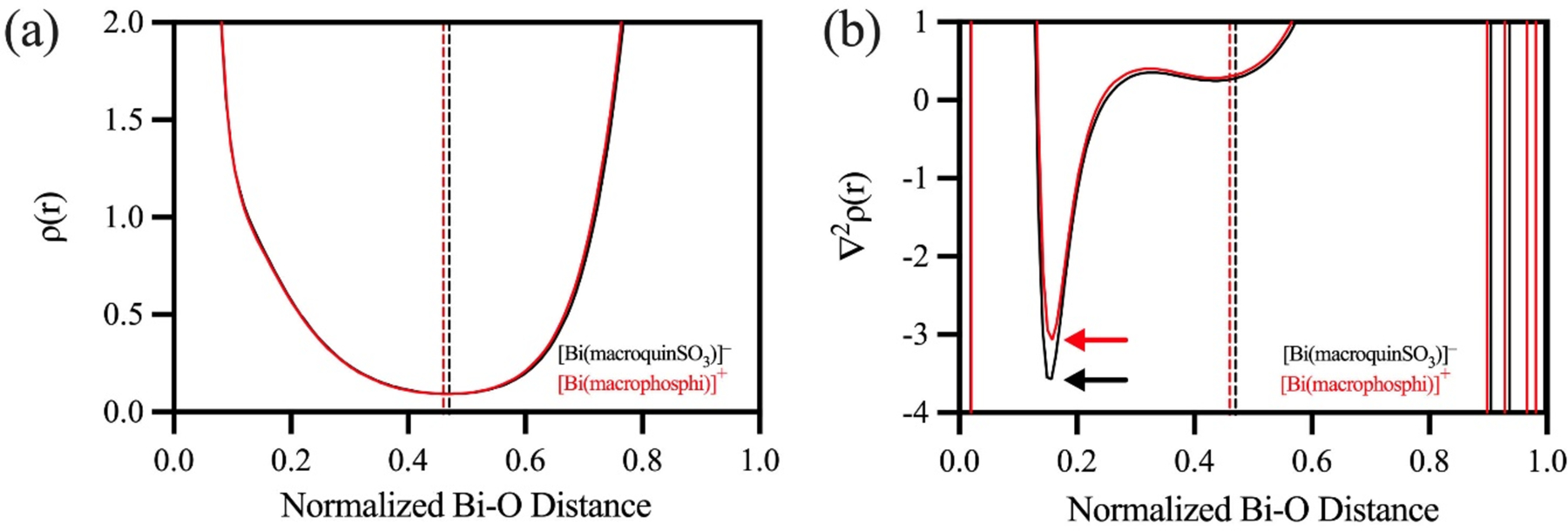

A recent study has shown that topological analysis of QTAIM parameters along the length of the bond path, rather than just at the BCP, provides useful information into the nature of the bonding interactions in complexes containing heavy main-group elements.99 As such, we evaluated ρ and ∇2ρ(r) across the entire length of the Bi–O bonds in [Bi(macrophosphi)]+ and [Bi(macroquin-SO3)]−. To account for differing interatomic distances and facilitate comparison of the complexes, the interatomic distances were normalized to one-unit length. The plot of ρ(r) reveals a clear minimum between the atoms, indicating the location of the BCP for the Bi–O interaction (Figure 6a). For both complexes, the BCP is shifted away from the midpoint of the bond path and towards the oxygen atom, which highlights the different electronegativities of the elements and the polarized nature of this interaction. The BCP is less shifted from the midpoint of the Bi and O atoms for [Bi(macroquin-SO3)]− compared to [Bi(macrophosphi)]+, which suggests that the distribution of ρ(r) across the bond is slightly more symmetric and the interaction is more covalent in nature. This result agrees with the analysis of the energy density parameters at the BCP (Table 5). In the plot of ∇2ρ(r), the single local minimum along the bond path is located near the oxygen atom (Figure 6b), a feature that is observed in other systems with interactions between second-period elements and third- and fourth-period elements.99–104 It has been shown that the decrease in the magnitude of this local minimum can be attributed to a decrease in bond order.99 As expected, the local minimum for [Bi(macroquin-SO3)]− is considerably more negative than for [Bi(macroposphi)]+, suggesting that the interaction between Bi and the O donor atoms of the quinoline pendent arms is more covalent in nature than those of the picolinate donors. Taken together, these results suggest that the enhanced kinetic inertness of [Bi(macroquin-SO3)]− compared to the other chelators described here may stem from the increased covalency between the metal center and the donor atoms of the pendent arms.

Figure 6.

Evaluation of (a) ρ and (b) ∇2ρ along the normalized Bi–O bond paths of [Bi(macrophosphi)]+ and [Bi(macroquin-SO3)]−. Dashed vertical lines represent the location of the BCP.

Radiolabeling Studies.

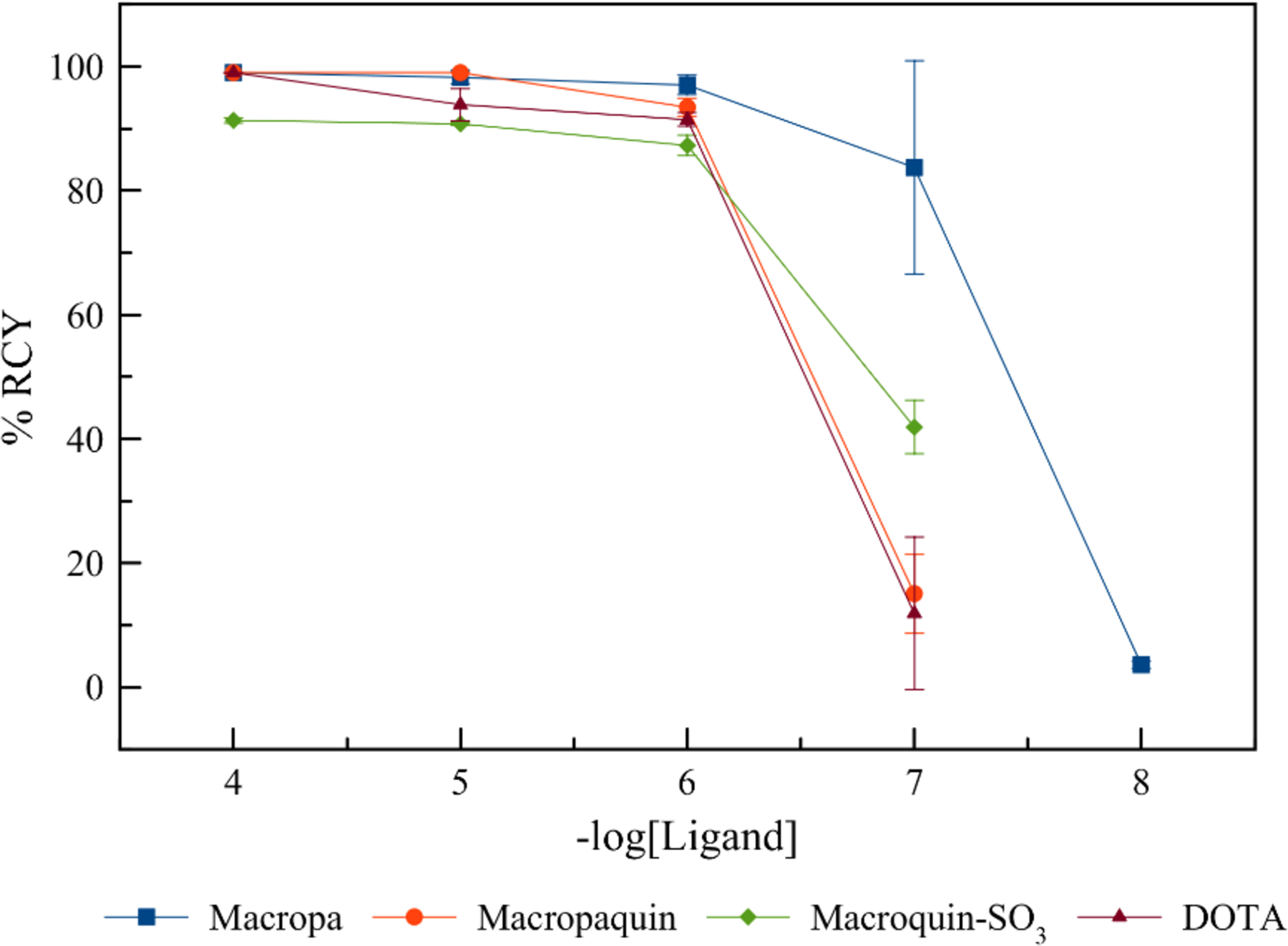

As a final validation on the value of these chelators for 213Bi TAT, we carried out radiolabeling studies using macropa, macropaquin, and macroquin-SO3, which formed comparatively more inert Bi3+ complexes than the other ligands. These ligands, in concentrations ranging from 10−7 to 10−4 M, were mixed with [213Bi]BiI4−/[213Bi]BiI52− (30 kBq–210 kBq), freshly eluted from a 225Ac/213Bi generator, in pH 5.5 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) buffer. As radiolabeling progressed at room temperature for 18-membered macrocycles or 95 °C for DOTA, aliquots were removed and analyzed by radio-TLC to assess the radiochemical yields (RCYs) after 8 min for 18-membered macrocycles or 5.5 min for DOTA. The resulting concentration-dependent RCYs for each ligand are collected in Table 6 and Figure 7. Notably, despite the radiolabeling reactions being performed at room temperature for the 18-membered macrocycles, the RCYs obtained are greater than those for DOTA, which required heating at 95 °C for all concentrations. At the highest ligand concentration (10−4 M), macropa, macropaquin, and DOTA quantitatively radiolabel 213Bi, whereas macroquin-SO3 achieved a 91% RCY under these conditions. For all four ligands, RCYs of approximately 90% are maintained upon decreasing the ligand concentration by two order of magnitude to 10−6 M. At ligand concentrations of 10−7 M, significant differences in the RCYs are observed across the four chelators. DOTA and macropaquin perform the poorest at this concentration, reaching RCYs of approximately 12 and 15%, respectively. Macroquin-SO3 achieves a moderate 40% RCY at this concentration, whereas macropa maintains a RCY of approximately 80%, affirming its superior radiolabeling capabilities. Notably, all three of these macrocyclic ligands outperform DOTA, indicating that they may be more favorable for use in 213Bi TAT.

Table 6.

Average RCYs (%) of [213Bi]Bi-Complexes at 95 °C for DOTA after 5.5 min and Room Temperature for other Ligands after 8 min

| Ligand Concentration | macropa | macropaquin | macroquin-SO3 | DOTA (95 °C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10−4 M | >99 | >99 | 91 ± 1 | >99 |

| 10−5 M | 98 ± 1 | >99 | 91 ± 1 | 94 ± 3 |

| 10−6 M | 97 ± 2 | 93 ± 2 | 87 ± 2 | 91 ± 1 |

| 10−7 M | 84 ± 17 | 15 ± 6 | 42 ± 4 | 12 ± 12 |

| 10−8M | 4 ± 1 |

Figure 7.

RCYs for each ligand vs. concentration. Concentration-dependent radiolabeling studies were performed by the addition of [213Bi]BiI4−/[213Bi]BiI52− (30 kBq–210 kBq) to a solution containing ligands in MES buffer (0.5 M, pH 5.5–6). All radiolabeling studies were carried out within 5 min post-elution of the 225Ac/213Bi generator. Macropa, macropaquin, and macroquin-SO3 were incubated at room temperature for 8 min, whereas DOTA was incubated at 95 °C for 5.5 min.

A comparison of the radiolabeling properties of these ligands can also be discerned from the decay-corrected molar activities (Table 7). At the lowest ligand concentrations required to achieve > 80% RCY, molar activities of 8.69, 1.49, and 1.82 MBq/nmol were obtained for the radiolabeled complexes of macropa, macropaquin, and macroquin-SO3, respectively. These values are significantly larger than the molar activity of 0.284 MBq/mol that was achieved with DOTA under elevated temperatures. In particular, the 30-fold greater molar activity of macropa in comparison to DOTA, which was accomplished at room temperature, highlights the effective 213Bi-radiolabeling properties of these 18-membered macrocycles.

Table 7.

Molar Activities (MBq/nmol) of [213Bi]Bi-Complexes at the Lowest Ligand Concentrations Required to Attain > 80% RCY

| Ligand | Molar Activity (MBq/nmol) |

|---|---|

| macropa | 8.69 |

| macropaquin | 1.49 |

| macroquin-SO3 | 1.82 |

| DOTA | 0.284 |

Conclusions

In conclusion, a set of six macrocyclic ligands were evaluated for their potential as Bi3+ chelators in TAT. These ligands, all containing the 18-membered diaza-18-crown-6 macrocyclic core, differed based on their pendent donors, as well as macrocycle rigidity. The evaluation of the kinetic properties of the Bi3+ complexes revealed that macrocycle rigidity had little influence on their inertness, in contrast to pendent donor basicity, which played a large role. Specifically, more basic donors, like the quinolinate groups found in macroquin-SO3, gave rise to more kinetically inert complexes, whereas the least basic phosphinate and phosphonate groups yielded labile complexes. To understand the origins of this effect, the complexes were fully characterized by solid-state and solution methods. Although the solid-state X-ray crystal structures showed profound structural distortion arising from the stereochemically active 6s2 lone pair of the Bi3+ ion, NMR studies indicate that an averaged symmetric complex is obtained in solution. Furthermore, DFT calculations verified that the extent of the stereochemical activity of this lone pair, as measured by the corresponding %p character, had little ramifications on the overall inertness of the complexes. By contrast, these computational studies predicted that an increase in covalency contributed to the enhanced inertness of the macroquin-SO3 complex over those of the other ligands. Despite the excellent kinetic inertness of the [Bi(macroquin-SO3)]− complex, radiolabeling of this ligand with 213Bi was relatively inefficient compared to macropa. Given the short half-life of 213Bi, the faster radiolabeling and higher molar activities afforded by macropa may be more favorable for applications in TAT.

In summary, this study has shown that the diaza-18-crown-6 scaffold is highly promising for use in Bi3+ chelation, displaying several advantages, such as vast tunability and rapid complex formation, over the conventional cyclen-based chelators. The tunability of this class of ligands via changing the basicity of the pendent donor groups can be valuable for accessing new highly promising BFCs for 213Bi TAT. Future work will assess the suitability of the ligands in this study for this application.

Supplementary Material

Funding Sources

This research was supported by funding from the College of Arts and Sciences at Cornell University, by the National Institute for Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01 EB029259, and by the Research Corporation for Science Advancement in the form of a Cottrell Scholar Award to J. J. Wilson. J. J. Woods thanks the American Heart Association for a predoctoral fellowship (20PRE35120390). This research also made use of the NMR Facility at Cornell University, which is supported, in part, by the United States National Science Foundation under Award CHE-1531632. We gratefully acknowledge the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada for a CREATE IsoSiM at TRIUMF research stipend (L. Wharton), financial support via NSERC Discovery Grants (V. Radchenko), and support via a Master’s Canada Graduate Scholarship (V. Brown). TRIUMF receives federal funding via a contribution agreement with the National Research Council of Canada.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c01269.

Experimental procedures, characterization data, computational details, radiolabeling data (PDF), xyz coordinates of DFT-optimized structures (.zip)

Accession Codes

CCDC 2079740-2079742 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033.

REFERENCES

- (1).Kim Y-SS; Brechbiel MW An Overview of Targeted Alpha Therapy. Tumor Biol. 2012, 33, 573–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Dekempeneer Y; Keyaerts M; Krasniqi A; Puttemans J; Muyldermans S; Lahoutte T; D’huyvetter M; Devoogdt N Targeted Alpha Therapy Using Short-Lived Alpha-Particles and the Promise of Nanobodies as Targeting Vehicle. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther 2016, 16, 1035–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Couturier O; Supiot S; Degraef-Mougin M; Faivre-Chauvet A; Carlier T; Chatal J-F; Davodeau F; Cherel M Cancer Radioimmunotherapy with Alpha-Emitting Nuclides. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2005, 32, 601–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Brechbiel MW Targeted α-Therapy: Past, Present, Future? Dalton Trans. 2007, 4918–4928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Mulford DA; Scheinberg DA; Jurcic JG The Promise of Targeted α-Particle Therapy. J. Nucl. Med 2005, 46, 199S–204S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Price EW; Orvig C Matching Chelators to Radiometals for Radiopharmaceuticals. Chem. Soc. Rev 2014, 43, 260–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Kostelnik TI; Orvig C Radioactive Main Group and Rare Earth Metals for Imaging and Therapy. Chem. Rev 2019, 119, 902–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Harrison MR; Wong TZ; Armstrong AJ; George DJ Radium-223 Chloride: A Potential New Treatment for Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Patients with Metastatic Bone Disease. Cancer Manag. Res 2013, 5, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Pandit-Taskar N; Larson SM; Carrasquillo JA Bone-Seeking Radiopharmaceuticals for Treatment of Osseous Metastases, Part 1: α Therapy with 223Ra-Dichloride. J. Nucl. Med 2014, 55, 268–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Coleman R Treatment of Metastatic Bone Disease and the Emerging Role of Radium-223. Semin. Nucl. Med 2016, 46, 99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Abou DS; Thiele NA; Gutsche NT; Villmer A; Zhang H; Woods JJ; Baidoo KE; Escorcia FE; Wilson JJ; Thorek DLJ Towards the Stable Chelation of Radium for Biomedical Applications with an 18-Membered Macrocyclic Ligand. Chem. Sci 2021, 12, 3733–3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Matyskin AV; Hansson NL; Brown PL; Ekberg C Barium and Radium Complexation with Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid in Aqueous Alkaline Sodium Chloride Media. J. Solution Chem 2017, 46, 1951–1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Chiarizia R; Horwitz EP; Dietz ML; Cheng YD Radium Separation through Complexation by Aqueous Crown Ethers and Extraction by Dinonylnaphthalenesulfonic Acid. React. Funct. Polym 1998, 38, 249–257. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Henriksen G; Hoff P; Larsen RH Evaluation of Potential Chelating Agents for Radium. Appl. Radiat. Isot 2002, 56, 667–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Chen X; Ji M; Fisher DR; Wai CM Ionizable Calixarene-Crown Ethers with High Selectivity for Radium over Light Alkaline Earth Metal Ions. Inorg. Chem 1999, 38, 5449–5452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Kratochwil C; Bruchertseifer F; Giesel FL; Weis M; Verburg FA; Mottaghy F; Kopka K; Apostolidis C; Haberkorn U; Morgenstern A 225Ac-PSMA-617 for PSMA-Targeted α-Radiation Therapy of Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. J. Nucl. Med 2016, 57, 1941–1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Morgenstern A; Apostolidis C; Bruchertseifer F Supply and Clinical Application of Actinium-225 and Bismuth-213. Semin. Nucl. Med 2020, 50, 119–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Guseva LI; Dogadkin NN A Generator System for Production of Medical Alpha-Radionuclides Ac-225 and Bi-213. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem 2010, 285, 667–673. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Morgenstern A; Bruchertseifer F; Apostolidis C Bismuth-213 and Actinium-225 – Generator Performance and Evolving Therapeutic Applications of Two Generator-Derived Alpha-Emitting Radioisotopes. Curr. Radiopharm 2012, 5, 221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Bond AH; Rogers RD Bismuth Coordination Chemistry: A Brief Retrospective Spanning Crystallography to Clinical Potential. J. Coord. Chem 2021, 74, 129–151. [Google Scholar]

- (21).McDevitt MR; Finn RD; Sgouros G; Ma D; Scheinberg DA An 225Ac/213Bi Generator System for Therapeutic Clinical Applications : Construction and Operation. Appl. Radiat. Isot 1999, 50, 895–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Jurcic JG; Larson SM; Sgouros G; McDevitt MR; Finn RD; Divgi CR; Ballangrud ÅM; Hamacher KA; Ma D; Humm JL; Brechbiel MW; Molinet R; Scheinberg DA Targeted α Particle Immunotherapy for Myeloid Leukemia. Blood 2002, 100, 1233–1239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Kneifel S; Cordier D; Good S; Ionescu MCS; Ghaffari A; Hofer S; Kretzschmar M; Tolnay M; Apostolidis C; Waser B; Arnold M; Mueller-Brand J; Maecke HR; Reubi JC; Merlo A Local Targeting of Malignant Gliomas by the Diffusible Peptidic Vector 1,4,7,10-Tetraazacyclododecane-1-Glutaric Acid-4,7,10-Triacetic Acid-Substance P. Clin. Cancer Res 2006, 12, 3843–3850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Cordier D; Forrer F; Bruchertseifer F; Morgenstern A; Apostolidis C; Good S; Müller-Brand J; Mäcke H; Reubi JC; Merlo A Targeted Alpha-Radionuclide Therapy of Functionally Critically Located Gliomas with 213Bi-DOTA-[Thi8,Met(O2)11]- Substance P: A Pilot Trial. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2010, 37, 1335–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Raja C; Graham P; Abbas Rizvi SM; Song E; Goldsmith H; Thompson J; Bosserhoff A; Morgenstern A; Apostolidis C; Kearsley J; Reisfeld R; Allen BJ Interim Analysis of Toxicity and Response in Phase 1 Trial of Systemic Targeted Alpha Therapy for Metastatic Melanoma. Cancer Biol. Ther 2007, 6, 846–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Rosenblat TL; McDevitt MR; Mulford DA; Pandit-Taskar N; Divgi CR; Panageas KS; Heaney ML; Chanel S; Morgenstern A; Sgouros G; Larson SM; Scheinberg DA; Jurcic JG Sequential Cytarabine and α-Particle Immunotherapy with Bismuth-213-Lintuzumab (HuM195) for Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res 2010, 16, 5303–5311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Egorova BV; Matazova EV; Mitrofanov AA; Aleshin GY; Trigub AL; Zubenko AD; Fedorova OA; Fedorov YV; Kalmykov SN Novel Pyridine-Containing Azacrownethers for the Chelation of Therapeutic Bismuth Radioisotopes: Complexation Study, Radiolabeling, Serum Stability and Biodistribution. Nucl. Med. Biol 2018, 60, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Wilson JJ; Ferrier M; Radchenko V; Maassen JR; Engle JW; Batista ER; Martin RL; Nortier FM; Fassbender ME; John KD; Birnbaum ER Evaluation of Nitrogen-Rich Macrocyclic Ligands for the Chelation of Therapeutic Bismuth Radioisotopes. Nucl. Med. Biol 2015, 42, 428–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Šimeček J; Hermann P; Seidl C; Bruchertseifer F; Morgenstern A; Wester H-J; Notni J Efficient Formation of Inert Bi-213 Chelates by Tetraphosphorus Acid Analogues of DOTA: Towards Improved Alpha-Therapeutics. EJNMMI Res. 2018, 8, 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Briand GG; Burford N Bismuth Compounds and Preparations with Biological or Medicinal Relevance. Chem. Rev 1999, 99, 2601–2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Hassfjell S; Brechbiel MW The Development of the α-Particle Emitting Radionuclides 212Bi and 213Bi, and Their Decay Chain Related Radionuclides, for Therapeutic Applications. Chem. Rev 2001, 101, 2019–2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Stavila V; Davidovich RL; Gulea A; Whitmire KH Bismuth(III) Complexes with Aminopolycarboxylate and Polyaminopolycarboxylate Ligands: Chemistry and Structure. Coord. Chem. Rev 2006, 250, 2782–2810. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Sinenko IL; Kalmykova TP; Likhosherstova DV; Egorova BV; Zubenko AD; Vasiliev AN; Ermolaev SV; Lapshina EV; Ostapenko VS; Fedorova OA; Kalmykov SN 213Bi Production and Complexation with New Picolinate Containing Ligands. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem 2019, 321, 531–540. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Matazova EV; Egorova BV; Konopkina EA; Aleshin GY; Zubenko AD; Mitrofanov AA; Karpov KV; Fedorova OA; Fedorov YV; Kalmykov SN Benzoazacrown Compound: A Highly Effective Chelator for Therapeutic Bismuth Radioisotopes. MedChemComm 2019, 10, 1641–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Lange JL; Davey PRWJ; Ma MT; White JM; Morgenstern A; Bruchertseifer F; Blower PJ; Paterson BM An Octadentate Bis(Semicarbazone) Macrocycle: A Potential Chelator for Lead and Bismuth Radiopharmaceuticals. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 14962–14974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Dadwal M; Kang CS; Song HA; Sun X; Dai A; Baidoo KE; Brechbiel MW; Chong H-S Synthesis and Evaluation of a Bifunctional Chelate for Development of Bi(III)-Labeled Radioimmunoconjugates. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2011, 21, 7513–7515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Chong H-S; Lim S; Baidoo KE; Milenic DE; Ma X; Jia F; Song HA; Brechbiel MW; Lewis MR Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of a Novel Decadentate Ligand DEPA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2008, 18, 5792–5795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Chong H-S; Song HA; Birch N; Le T; Lim S; Ma X Efficient Synthesis and Evaluation of Bimodal Ligand NETA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2008, 18, 3436–3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Lima LMP; Beyler M; Delgado R; Platas-Iglesias C; Tripier R Investigating the Complexation of the Pb2+/Bi3+ Pair with Dipicolinate Cyclen Ligands. Inorg. Chem 2015, 54, 7045–7057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Thiabaud G; Radchenko V; Wilson JJ; John KD; Birnbaum ER; Sessler JL Rapid Insertion of Bismuth Radioactive Isotopes into Texaphyrin in Aqueous Media. J. Porphyrins Phthalocyanines 2017, 21, 882–886. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Lima LMP; Beyler M; Oukhatar F; Le Saec P; Faivre-Chauvet A; Platas-Iglesias C; Delgado R; Tripier R H2Me-Do2pa: An Attractive Chelator with Fast, Stable and Inert natBi3+ and 213Bi3+ Complexation for Potential α-Radioimmunotherapy Applications. Chem. Commun 2014, 50, 12371–12374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Brechbiel MW; Gansow OA; Pippin CG; Rogers RD; Planalp RP Preparation of the Novel Chelating Agent N-(2-Aminoethyl)-trans-1,2-Diaminocyclohexane-N,N′,N″-Pentaacetic Acid (H5CyDTPA), a Preorganized Analogue of Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic Acid (H5DTPA), and the Structure of BiIII(CyDTPA)2− and BiIII(H2DTPA) Complexes. Inorg. Chem 1996, 35, 6343–6348. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Kozak RW; Waldmann TA; Atcher RW; Gansow OA Radionuclide-Conjugated Monoclonal Antibodies: A Synthesis of Immunology, Inorganic Chemistry and Nuclear Science. Trends Biotechnol. 1986, 4, 259–264. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Chong H-S; Milenic DE; Garmestani K; Brady ED; Arora H; Pfiester C; Brechbiel MW In vitro and in vivo Evaluation of Novel Ligands for Radioimmunotherapy. Nucl. Med. Biol 2006, 33, 459–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Hassfjell S; Kongshaug KO; Romming C Synthesis, Crystal Structure and Chemical Stability of Bismuth(III) Complexed with 1,4,7,10-Tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-Tetramethylene Phosphonic Acid (H8DOTMP). Dalton Trans. 2003, 1433–1437. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Pujales-Paradela R; Rodríguez-Rodríguez A; Gayoso-Padula A; Brandariz I; Valencia L; Esteban-Gómez D; Platas-Iglesias C On the Consequences of the Stereochemical Activity of the Bi(III) 6s2 Lone Pair in Cyclen-Based Complexes. the [Bi(DO3A)] Case. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 13830–13842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Bruchertseifer F; Comba P; Martin B; Morgenstern A; Notni J; Starke M; Wadepohl H First-Generation Bispidine Chelators for 213BiIII Radiopharmaceutical Applications. ChemMedChem 2020, 15, 1591–1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Milenic DE; Roselli M; Mirzadeh S; Pippin CG; Gansow OA; Colcher D; Brechbiel MW; Schlom J In vivo Evaluation of Bismuth-Labeled Monoclonal Antibody Comparing DTPA-Derived Bifunctional Chelates. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm 2001, 16, 133–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Montavon G; Le Du A; Champion J; Rabung T; Morgenstern A DTPA Complexation of Bismuth in Human Blood Serum. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 8615–8623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Chan HS; de Blois E; Konijnenberg MW; Morgenstern A; Bruchertseifer F; Norenberg JP; Verzijlbergen FJ; de Jong M; Breeman WAP Optimizing Labelling Conditions of 213Bi-DOTATATE for Preclinical Applications of Peptide Receptor Targeted Alpha Therapy. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem 2016, 1, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Fazel J; Rötzer S; Seidl C; Feuerecker B; Autenrieth M; Weirich G; Bruchertseifer F; Morgenstern A; Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R Fractionated Intravesical Radioimmunotherapy with 213Bi-Anti-EGFR-MAb Is Effective without Toxic Side-Effects in a Nude Mouse Model of Advanced Human Bladder Carcinoma. Cancer Biol. Ther 2015, 16, 1526–1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Teiluf K; Seidl C; Blechert B; Gaertner FC; Gilbertz K-P; Fernandez V; Bassermann F; Endell J; Boxhammer R; Leclair S; Vallon M; Aichler M; Feuchtinger A; Bruchertseifer F; Morgenstern A; Essler M α-Radioimmunotherapy with 213Bi-Anti-CD38 Immunoconjugates Is Effective in a Mouse Model of Human Multiple Myeloma. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 4692–4703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Fichou N; Gouard S; Maurel C; Barbet J; Ferrer L; Morgenstern A; Bruchertseifer F; Faivre-Chauvet A; Bigot-Corbel E; Davodeau F; Gaschet J; Chérel M Single-Dose Anti-CD138 Radioimmunotherapy: Bismuth-213 Is More Efficient than Lutetium-177 for Treatment of Multiple Myeloma in a Preclinical Model. Front. Med 2015, 2, 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R; Schuhmacher C; Becker K-F; Nikula TK; Seidl C; Becker I; Miederer M; Apostolidis C; Adam C; Huber R; Kremmer E; Fischer K; Schwaiger M Highly Specific Tumor Binding of a 213Bi-Labeled Monoclonal Antibody against Mutant E-Cadherin Suggests Its Usefulness for Locoregional α-Radioimmunotherapy of Diffuse-Type Gastric Cancer. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 2804–2808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Friesen C; Glatting G; Koop B; Schwarz K; Morgenstern A; Apostolidis C; Debatin K-M; Reske SN Breaking Chemoresistance and Radioresistance with [213Bi]Anti- CD45 Antibodies in Leukemia Cells. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 1950–1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Shannon RD Revised Effective Ionic Radii and Systematic Studies of Interatomic Distances in Halides and Chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Adv 1976, 32, 751–767. [Google Scholar]

- (57).Näslund J; Persson I; Sandström M Solvation of the Bismuth(III) Ion by Water, Dimethyl Sulfoxide, N,N’-Dimethylpropyleneurea, and N,N-Dimethylthioformamide. An EXAFS, Large-Angle X-Ray Scattering, and Crystallographic Structural Study. Inorg. Chem 2000, 39, 4012–4021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Roca-Sabio A; Mato-Iglesias M; Esteban-Gómez D; Tóth É; De Bias A; Platas-Iglesias C; Rodríguez-Blas T Macrocyclic Receptor Exhibiting Unprecedented Selectivity for Light Lanthanides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 3331–3341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Thiele NA; MacMillan SN; Wilson JJ Rapid Dissolution of BaSO4 by Macropa, an 18-Membered Macrocycle with High Affinity for Ba2+. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 17071–17078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Thiele NA; Woods JJ; Wilson JJ Implementing f-Block Metal Ions in Medicine: Tuning the Size Selectivity of Expanded Macrocycles. Inorg. Chem 2019, 58, 10483–10500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Carreira-Barral I; Rodríguez-Rodríguez A; Regueiro-Figueroa M; Esteban-Gómez D; Platas-Iglesias C; de Blas A; Rodríguez-Blas T A Merged Experimental and Theoretical Conformational Study on Alkaline-Earth Complexes with Lariat Ethers Derived from 4,13-Diaza-18-Crown-6. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2011, 370, 270–278. [Google Scholar]

- (62).Jensen MP; Chiarizia R; Shkrob IA; Ulicki JS; Spindler BD; Murphy DJ; Hossain M; Roca-Sabio A; Platas-Iglesias C; de Blas A; Rodríguez-Blas T Aqueous Complexes for Efficient Size-Based Separation of Americium from Curium. Inorg. Chem 2014, 53, 6003–6012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Ferreirós-Martínez R; Esteban-Gómez D; Tóth É; de Blas A; Platas-Iglesias C; Rodríguez-Blas T Macrocyclic Receptor Showing Extremely High Sr(II)/Ca(II) and Pb(II)/Ca(II) Selectivities with Potential Application in Chelation Treatment of Metal Intoxication. Inorg. Chem 2011, 50, 3772–3784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Chang CA; Rowland ME Metal Complex Formation with 1,10- Diaza-4,7,13,16-Tetraoxacyclooctadecane-N,N’ -Diacetic Acid. An Approach to Potential Lanthanide Ion Selective Reagents. Inorg. Chem 1983, 22, 3866–3869. [Google Scholar]

- (65).Brücher E; Györi B; Emri J; Solymosi P; Sztanyik LB; Varga L 1,10-Diaza-4,7,13,16-Tetraoxacyclooctadecane-1,10-Bis(Malonate), a Ligand with High Sr2+/Ca2+ and Pb2+/Zn2+ Selectivities in Aqueous Solution. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 1993, 574–575. [Google Scholar]

- (66).Peters JA; Djanashvili K; Geraldes CFGC; Platas-Iglesias C The Chemical Consequences of the Gradual Decrease of the Ionic Radius along the Ln-Series. Coord. Chem. Rev 2020, 406, 213146. [Google Scholar]

- (67).Thiele NA; Brown V; Kelly JM; Amor-Coarasa A; Jermilova U; MacMillan SN; Nikolopoulou A; Ponnala S; Ramogida CF; Robertson AKH; Rodríguez-Rodríguez C; Schaffer P; Williams C Jr.; Babich JW; Radchenko V; Wilson JJ An Eighteen-Membered Macrocyclic Ligand for Actinium-225 Targeted Alpha Therapy. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2017, 56, 14712–14717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Aluicio-Sarduy E; Thiele NA; Martin KE; Vaughn BA; Devaraj J; Olson AP; Barnhart TE; Wilson JJ; Boros E; Engle JW Establishing Radiolanthanum Chemistry for Targeted Nuclear Medicine Applications. Chem. - Eur. J 2020, 26, 1238–1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Thiele NA; Fiszbein DJ; Woods JJ; Wilson JJ Tuning the Separation of Light Lanthanides Using a Reverse-Size Selective Aqueous Complexant. Inorg. Chem 2020, 59, 16522–16530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Polášek M; Šedinová M; Kotek J; Vander Elst L; Muller RN; Hermann P; Lukeš I Pyridine-N-Oxide Analogues of DOTA and Their Gadolinium(III) Complexes Endowed with a Fast Water Exchange on the Square-Antiprismatic Isomer. Inorg. Chem 2009, 48, 455–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Lee S-J; Kim H-S; Yang H-W; Yoo B-W; Yoon CM Synthesis of Diethyl Pyridin-2-ylphosphonates and Quinolin-2-ylphosphonates by Deoxygenative Phosphorylation of the Corresponding N-Oxides. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc 2014, 35, 2155–2158. [Google Scholar]

- (72).Salaam J; Tabti L; Bahamyirou S; Lecointre A; Hernandez Alba O; Jeannin O; Camerel F; Cianférani S; Bentouhami E; Nonat AM; Charbonnière LJ Formation of Mono- and Polynuclear Luminescent Lanthanide Complexes Based on the Coordination of Preorganized Phosphonated Pyridines. Inorg. Chem 2018, 57, 6095–6106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Hlinová V; Jaroš A; David T; Císařová I; Kotek J; Kubíček V; Hermann P Complexes of Phosphonate and Phosphinate Derivatives of Dipicolylamine. New J. Chem 2018, 42, 7713–7722. [Google Scholar]

- (74).Summers SP; Abboud KA; Farrah SR; Palenik GJ Syntheses and Structures of Bismuth(III) Complexes with Nitrilotriacetic Acid, Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid, and Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic Acid. Inorg. Chem 1994, 33, 88–92. [Google Scholar]

- (75).Csajbók É; Baranyai Z; Bányai I; Brücher E; Király R; Müller-Fahrnow A; Platzek J; Radüchel B; Schäfer M Equilibrium, 1H and 13C NMR Spectroscopy, and X-Ray Diffraction Studies on the Complexes Bi(DOTA)− and Bi(DO3A-Bu). Inorg. Chem 2003, 42, 2342–2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Shimoni-Livny L; Glusker JP; Bock CW Lone Pair Functionality in Divalent Lead Compounds. Inorg. Chem 1998, 37, 1853–1867. [Google Scholar]

- (77).Llunell M; Casanova D; Cirera J; Alemany P; Alvarez S SHAPE 2.1 University of Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- (78).Tao J; Perdew JP; Staroverov VN; Scuseria GE Climbing the Density Functional Ladder: Nonempirical Meta–Generalized Gradient Approximation Designed for Molecules and Solids. Phys. Rev. Lett 2003, 91, 146401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Metz B; Stoll H; Dolg M Small-Core Multiconfiguration-Dirac-Hartree-Fock-Adjusted Pseudopotentials for Post-d Main Group Elements: Application to PbH and PbO. J. Chem. Phys 2000, 113, 2563–2569. [Google Scholar]

- (80).Schäfer A; Huber C; Ahlrichs R Fully Optimized Contracted Gaussian Basis Sets of Triple Zeta Valence Quality for Atoms Li to Kr. J. Chem. Phys 1994, 100, 5829–5835. [Google Scholar]

- (81).Matito E; Solà M The Role of Electronic Delocalization in Transition Metal Complexes from the Electron Localization Function and the Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules Viewpoints. Coord. Chem. Rev 2009, 253, 647–665. [Google Scholar]

- (82).Esteban-Gómez D; Platas-Iglesias C; Enríquez-Pérez T; Avecilla F; de Blas A; Rodríguez-Blas T Lone-Pair Activity in Lead(II) Complexes with Unsymmetrical Lariat Ethers. Inorg. Chem 2006, 45, 5407–5416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (83).Ferreirós-Martínez R; Esteban-Gómez D; de Blas A; Platas-Iglesias C; Rodríguez-Blas T Eight-Coordinate Zn(II), Cd(II), and Pb(II) Complexes Based on a 1,7-Diaza-12-Crown-4 Platform Endowed with a Remarkable Selectivity over Ca(II). Inorg. Chem 2009, 48, 11821–11831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Baumann W; Schulz A; Villinger A A Blue Homoleptic Bismuth–Nitrogen Cation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2008, 47, 9530–9532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).Bader RFW A Quantum Theory of Molecular Structure and Its Applications. Chem. Rev 1991, 91, 893–928. [Google Scholar]

- (86).Varadwaj PR; Marques HM The Physical Chemistry of Coordinated Aqua-, Ammine-, and Mixed-Ligand Co2+ Complexes: DFT Studies on the Structure, Energetics, and Topological Properties of the Electron Density. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2010, 12, 2126–2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (87).Varadwaj PR; Marques HM The Physical Chemistry of [M(H2O)4(NO3)2] (M = Mn2+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, Zn2+) Complexes: Computational Studies of Their Structure, Energetics and the Topolog. Theor. Chem. Acc 2010, 127, 711–725. [Google Scholar]

- (88).Chauvin R; Lepetit C; Silvi B; Alikhani E Applications of Topological Methods in Molecular Chemistry; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- (89).Mountain ARE; Kaltsoyannis N Do QTAIM Metrics Correlate with the Strength of Heavy Element-Ligand Bonds? Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 13477–13486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (90).Dan D; Celis-Barros C; White FD; Sperling JM; Albrecht-Schmitt TE Origin of Selectivity of a Triazinyl Ligand for Americium(III) over Neodymium(III). Chem. - Eur. J 2019, 25, 3248–3252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (91).White FD; Gaiser AN; Warzecha EJ; Sperling JM; Celis-Barros C; Salpage SR; Zhou Y; Dilbeck T; Bretton AJ; Meeker DS; Hanson KG; Albrecht-Schmitt TE Examination of Structure and Bonding in 10-Coordinate Europium and Americium Terpyridyl Complexes. Inorg. Chem 2018, 57, 12969–12975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (92).Windorff CJ; Celis-Barros C; Sperling JM; McKinnon NC; Albrecht-Schmitt TE Probing a Variation of the Inverse-Trans-Influence in Americium and Lanthanide Tribromide Tris(Tricyclohexylphosphine Oxide) Complexes. Chem. Sci 2020, 11, 2770–2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (93).Arnold PL; Prescimone A; Farnaby JH; Mansell SM; Parsons S; Kaltsoyannis N Characterizing Pressure-Induced Uranium C-H Agostic Bonds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2015, 54, 6735–6739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (94).Mansell SM; Kaltsoyannis N; Arnold PL Small Molecule Activation by Uranium Tris(Aryloxides): Experimental and Computational Studies of Binding of N2, Coupling of CO, and Deoxygenation Insertion of CO2 under Ambient Conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 9036–9051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (95).Tassell MJ; Kaltsoyannis N Covalency in AnCp4 (An = Th-Cm): A Comparison of Molecular Orbital, Natural Population and Atoms-in-Molecules Analyses. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 6719–6725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (96).Warzecha E; Celis-Barros C; Dilbeck T; Hanson K; Albrecht-Schmitt TE High-Pressure Studies of Cesium Uranyl Chloride. Inorg. Chem 2019, 58, 228–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (97).Chemey AT; Celis-Barros C; Huang K; Sperling JM; Windorff CJ; Baumbach RE; Graf DE; Páez-Hernández D; Ruf M; Hobart DE; Albrecht-Schmitt TE Electronic, Magnetic, and Theoretical Characterization of (NH4)4UF8, a Simple Molecular Uranium(IV) Fluoride. Inorg. Chem 2019, 58, 637–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (98).Macchi P; Sironi A Chemical Bonding in Transition Metal Carbonyl Clusters: Complementary Analysis of Theoretical and Experimental Electron Densities. Coord. Chem. Rev 2003, 238–239, 383–412. [Google Scholar]

- (99).Lindquist-Kleissler B; Wenger JS; Johnstone TC Analysis of Oxygen-Pnictogen Bonding with Full Bond Path Topological Analysis of the Electron Density. Inorg. Chem 2021, 60, 1846–1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (100).Scherer W; Sirsch P; Grosche M; Spiegler M; Mason SA; Gardiner MG Agostic Deformations Based on Electron Delocalization in the Alkyllithium-Complex [{2-(Me3Si)2CLiC5H4N}2. Chem. Commun 2001, 2072–2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (101).Scherer W; Sirsch P; Shorokhov D; McGrady GS; Mason SA; Gardiner MG Valence-Shell Charge Concentrations and Electron Delocalization in Alkyllithium Complexes: Negative Hyperconjugation and Agostic Bonding. Chem. - Eur. J 2002, 8, 2324–2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (102).Tafipolsky M; Scherer W; Öfele K; Artus G; Pedersen B; Herrmann WA; McGrady GS; Herrmann A, W.; Sean McGrady G Electron Delocalization in Acyclic and N-Heterocyclic Carbenes and Their Complexes: A Combined Experimental and Theoretical Charge-Density Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 5865–5880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (103).Ott H; Däschlein C; Leusser D; Schildbach D; Seibel T; Stalke D; Strohmann C Structure/Reactivity Studies on an α-Lithiated Benzylsilane: Chemical Interpretation of Experimental Charge Density. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 11901–11911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (104).Espinosa Ferao A; García Alcaraz A; Zaragoza Noguera S; Streubel R Terminal Phosphinidene Complex Adducts with Neutral and Anionic O-Donors and Halides and the Search for a Differentiating Bonding Descriptor. Inorg. Chem 2020, 59, 12829–12841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.