Abstract

Background and Aim

To evaluate the onset of symptomatic response with vedolizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis in Japan.

Methods

Patients were randomized to receive vedolizumab 300 mg or placebo at Weeks 0, 2, and 6. Mayo subscores were analyzed in patients with baseline stool frequency (SF) ≥1 and rectal bleeding (RB) ≥1. In patients with baseline SF ≥2 and RB ≥1, the proportion who achieved SF ≤1 and RB = 0 was determined.

Results

Patients were randomized to vedolizumab (n = 164) or placebo (n = 82). Decrease from baseline in mean SF subscore was greater with vedolizumab versus placebo from Week 2 (−6.6%; 95% confidence interval [CI], −16.2, 3.0), with a greater difference in anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α-naive patients (vedolizumab vs. placebo, −13.2%; 95% CI, −29.7, 3.3). Mean percentage decrease from baseline RB subscore was numerically greater with vedolizumab versus placebo from Week 6 in anti-TNFα-naive patients (−10.7%; 95% CI, −33.0, 11.5). More patients in the anti-TNFα-naive subgroup achieved SF ≤1 and RB = 0 with vedolizumab versus placebo at Week 2 (14.8%; 95% CI, 2.5, 27.0) and Week 6 (20.3%; 95% CI, 4.4, 36.2). Patients with SF ≤1 and RB = 0 at Week 2 had higher clinical response, clinical remission, and mucosal healing rates at Week 10 than those without.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that vedolizumab induces a rapid symptomatic response, particularly in anti-TNFα-naive patients, and suggest that early symptomatic improvement predicts treatment response at Week 10 (NCT02039505).

Keywords: Ulcerative colitis, Vedolizumab, Early symptomatic improvement

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by mucosal ulceration of the colon and clinical symptoms that impact patient's quality of life [1, 2]. Symptoms include increases in stool frequency (SF) [3] and rectal bleeding (RB), the latter reported by >90% of patients with active disease [1]. SF and RB are regularly used to measure patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in both clinical trials and practice [4].

Since publication of the US Food and Drug Administration PRO guidance in 2006, inclusion of patient-centered measures (e.g., symptomatic improvements) as clinical trial endpoints has been advocated [5, 6, 7]. A Steering Committee of 28 inflammatory bowel disease specialists recommended a therapeutic target for UC of both clinical and PRO remission including resolution of RB and normalization of bowel habit [7]. A 2-item PRO (SF ≤1 or ≤2 and RB = 0), with endoscopy as a co-primary endpoint, was proposed as an appropriate interim outcome measure for UC clinical trials [6].

Vedolizumab, a humanized, gut-selective immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody binding to α4β7 integrin, is approved in Japan for moderate-to-severe UC [8] and Crohn's disease [9]. Approval for UC was supported by a randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 study in 292 Japanese patients [8, 10]. In this study, the primary induction-phase endpoint of clinical response at Week 10 was numerically higher with vedolizumab versus placebo (39.6 vs. 32.9%). A greater difference was observed in anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α-naive (53.2 vs. 36.6%) but not in anti-TNFα-exposed (27.1 vs. 29.3%) patients [10]. All secondary induction-phase endpoints of clinical remission and mucosal healing were numerically higher at Week 10 with vedolizumab than with placebo [10].

Although these efficacy endpoints at Weeks 6 and 10 have been utilized for induction phases of clinical studies [10, 11] and Week 6 response is considered a predictor of later steroid-free clinical remission [12, 13], earlier symptomatic improvement at Week 2 is an important indicator of treatment effect from both patient and physician perspectives [14, 15]. In a recent post hoc analysis of GEMINI 1, vedolizumab significantly improved patient-reported symptoms of UC and Crohn's disease compared with placebo as early as Week 2, continuing through the first 6 weeks, particularly when given as first-line biologic therapy [16].

Clinical practice has evolved toward early use of disease-modifying therapies such as biologics in treating inflammatory bowel disease to facilitate mucosal healing and avoid disease progression and complications [17]. However, patients often consider early symptom relief and lack of side effects the most important factors during UC medication selection [18].

This post hoc analysis of a randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial evaluated the onset of symptomatic response in Japanese patients with UC, particularly anti-TNFα-naive patients. We also analyzed whether symptomatic response at Week 2 predicted efficacy outcomes (e.g., clinical response at Week 10), which have not been previously assessed.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This was a post hoc exploratory analysis of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group phase 3 study investigating efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of vedolizumab induction and maintenance treatment in Japanese patients with moderate-to-severe UC (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02039505 study). Data from the induction phase were analyzed. Detailed study methodology is reported elsewhere [10]; online suppl. Figure 1 (for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000512235) shows the study design. Eligible patients were aged 15–80 years with total or left-sided UC (based on Japanese Diagnostic Criteria for UC, 2012 revision) diagnosed ≥6 months before the start of study drug administration. Patients had moderate-to-severe UC, defined as full Mayo score 6–12 with baseline endoscopic subscore ≥2. In the induction phase, patients were randomized 2:1 to 300 mg intravenous infusions of vedolizumab or placebo at Weeks 0, 2, and 6. Dynamic randomization was performed with the following stratification factors: prior anti-TNFα exposure (yes/no), concomitant immunomodulator use (yes/no), concomitant corticosteroid use (yes/no), and study site.

Patient-Reported Outcomes

Patients recorded SF and RB in diaries. Mayo score was used to assess the severity of symptoms from diary entries and clinical response, clinical remission, and mucosal healing. Patients with SF subscore ≥1 and those with RB subscore ≥1 at baseline were used to analyze individual subscores. Percentage changes from baseline were calculated at Weeks 2, 6, and 10 for overall analysis population (i.e., regardless of anti-TNFα exposure), anti-TNFα-naive patients, anti-TNFα-exposed patients, and those with baseline full Mayo score 6–8 or 9–12. Proportion with SF subscore ≥2 and RB subscore ≥1 at baseline who achieved SF subscore ≤1 (i.e., ≤1–2 stools above normal) and RB subscore = 0 (i.e., elimination of bleeding) were determined at Weeks 2, 6, and 10. Clinical response was defined as decrease in full Mayo score of ≥3 points and ≥30% from baseline and decrease of ≥1 in RB subscore from baseline or absolute RB subscore ≤1 [19]. Clinical remission was defined as full Mayo score ≤2 and no subscore >1 [19]. Mucosal healing was defined as endoscopic subscore ≤1. Rates of clinical response, clinical remission, and mucosal healing were stratified by SF ≤ 1 and RB = 0 (yes/no) at Week 2 and determined for Week 10.

Statistical Analyses

The induction-phase full analysis set, defined as randomized patients who received at least 1 dose of study drug during the induction phase, is the focus of these analyses. No statistical comparisons were made between treatment groups for baseline characteristics in accordance with recommendation in “CONSORT 2010 Explanation and Elaboration” [20].

The difference in adjusted percentage change from baseline between vedolizumab and placebo in Mayo SF and RB subscores was determined using an analysis of covariance model with treatment (and prior anti-TNF use for the overall population) as a factor and baseline score as a covariate. Univariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify predictors of SF ≤ 1 and RB = 0 subscores at Week 2; p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. A multivariate analysis was performed by fitting baseline variables from the univariate analyses with p < 0.05 using stepwise backward regression. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient Baseline Characteristics

A total of 164 patients were randomized to receive vedolizumab and 82 to receive placebo (Table 1) [10]. Anti-TNFα-exposed patients constituted 52% (n = 85) of the vedolizumab group and 50% (n = 41) of the placebo group.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics of patients who entered the induction phase

| Vedolizumab (n = 164) | Placebo (n = 82) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr, mean (SD) | 42.3 (14.4) | 44.0 (16.0) |

| Male, n (%) | 99 (60.4) | 55 (67.1) |

| Duration of UC, yr, mean (SD) | 7.2 (6.2) | 8.6 (8.0) |

| Anti-TNFα-naive patients | 79 (48.2) | 41 (50.0) |

| Anti-TNFα-exposed patients | 85 (51.8) | 41 (50.0) |

| SF score, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 3 (1.8) | 0 |

| 1 | 14 (8.5) | 10 (12.2) |

| 2 | 45 (27.4) | 26 (31.7) |

| 3 | 102 (62.2) | 46 (56.1) |

| SF score, mean (SD) | 2.5 (0.65) | 2.4 (0.70) |

| Anti-TNFα-naive patients | 2.4 (0.74) | 2.3 (0.75) |

| Anti-TNFα-exposed patients | 2.7 (0.51) | 2.6 (0.63) |

| RB score, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 27 (16.5) | 16 (19.5) |

| 1 | 63 (38.4) | 30 (36.6) |

| 2 | 53 (32.3) | 29 (35.4) |

| 3 | 21 (12.8) | 7 (8.5) |

| RB score, mean (SD) | 1.7 (0.72) | 1.7 (0.67) |

| Anti-TNFα-naive patients | 1.7 (0.70) | 1.8 (0.62) |

| Anti-TNFα-exposed patients | 1.7 (0.75) | 1.6 (0.70) |

| Full Mayo score = 6–8, n (%) | 88 (53.7) | 47 (57.3) |

| Anti-TNFα-naive patients† | 49/88 (55.7) | 25/47 (53.2) |

| Anti-TNFα-exposed patients† | 39/88 (44.3) | 22/47 (46.8) |

| Full Mayo score = 9–12, n (%) | 76 (46.3) | 35 (42.7) |

| Anti-TNFα-naive patients† | 30/76 (39.5) | 16/35 (45.7) |

| Anti-TNFα-exposed patients† | 46/76 (60.5) | 19/35 (54.3) |

| Mayo endoscopic subscore = 2, n (%) | 110 (67.1) | 54 (65.9) |

| Anti-TNFα-exposed patients† | 47/85 (55.3) | 27/41 (65.9) |

| Mayo endoscopic subscore = 3, n (%) | 54 (32.9) | 28 (34.1) |

| Anti-TNFα-exposed patients‡ | 38/85 (44.7) | 14/41 (34.1) |

| Concomitant medication for UC, n (%) | ||

| 5-aminosalicylic acid | 145 (88.4) | 75 (91.5) |

| Oral corticosteroids only | 31 (18.9) | 11 (13.4) |

| Immunomodulators only | 59 (36.0) | 29 (35.4) |

| Oral corticosteroids and immunomodulators | 21 (12.8) | 14 (17.1) |

| No oral corticosteroids or immunomodulators | 53 (32.3) | 28 (34.1) |

| Prior failure of anti-TNFα, n (%) | 84 (51.2) | 41 (50.0) |

| Inadequate response† | 50/84 (59.5) | 22/41 (53.7) |

| Loss of response* | 32/84 (38.1) | 18/41 (43.9) |

| Intolerance* | 2/84 (2.4) | 1/41 (2.4) |

| Prior failure of corticosteroid therapy, n (%) | 109 (66.5) | 57 (69.5) |

| Prior failure of immunomodulator therapy, n (%) | 99 (60.4) | 52 (63.4) |

| Extraintestinal manifestations, n (%) | 53 (32.3) | 16 (19.5) |

| C-reactive protein level <3 mg/L, n (%) | 76 (46.3) | 50 (61.0) |

| Anti-TNFα-exposed patients‡ | 33/85 (38.8) | 25/41 (61.0) |

| C-reactive protein level ≥3 mg/L, n (%) | 88 (53.7) | 32 (39.0) |

| Anti-TNFα-exposed patients‡ | 52/85 (61.2) | 16/41 (39.0) |

RB, rectal bleeding; SD, standard deviation; SF, stool frequency; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha; UC, ulcerative colitis. † Number of patients in each subgroup used as denominator. ‡ Number of anti-TNFα-exposed patients used as denominator.

A descriptive summary of baseline characteristics showed that the 2 groups were generally similar, with a few exceptions (Table 1). Differences in full Mayo scores were not observed between vedolizumab and placebo groups for all patients; however, differences were observed in the anti-TNFα-exposed subgroup. In this subgroup, the proportion of patients with Mayo endoscopic subscore = 2 was lower in the vedolizumab group versus placebo group (55.3 vs. 65.9%), whereas proportion of patients with Mayo endoscopic subscore = 3 was higher with vedolizumab versus placebo (44.7 vs. 34.1%). A lower proportion of the overall study population had C-reactive protein level <3 mg/L with vedolizumab versus placebo (46.3 vs. 61.0%); this difference was more pronounced in the anti-TNFα-exposed subgroup (38.8 vs. 61.0%).

SF Subscores

At baseline, 161 (98.2%) vedolizumab-treated patients and 82 (100%) placebo recipients had SF subscores ≥1 and were analyzed at each visit. In this overall population, numerically greater percentage decreases from baseline in SF subscore occurred with vedolizumab than placebo as early as Week 2, persisting at Weeks 6 and 10 (Fig. 1a). Differences were greatest in anti-TNFα-naive patients (vedolizumab, n = 77; placebo, n = 41); this was seen at all time points with maximum numerical difference (vedolizumab minus placebo) of −18.7% (95% confidence interval [CI] −36.4, −0.9) at Week 6 (Fig. 1b). In anti-TNFα-exposed patients (vedolizumab, n = 84; placebo, n = 41), no notable differences in change from baseline in SF subscore were observed at any visit (Fig. 1c). Change from baseline between treatment groups was greater in those with baseline full Mayo score 6–8 than 9–12 (Fig. 1d, e). Online suppl. Figure 2 summarizes absolute SF subscores over time for vedolizumab versus placebo.

Fig. 1.

Percentage change from baseline in Mayo SF subscore by visit (patients with SF subscore ≥1 at baseline) in overall population (a), anti-TNFα-naive patients (b), anti-TNFα-exposed patients (c), baseline full Mayo score 6–8 (d), and baseline full Mayo score 9–12 (e). CI, confidence interval; PBO, placebo; SD, standard deviation; SF, stool frequency; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha; VDZ, vedolizumab.

RB Subscores

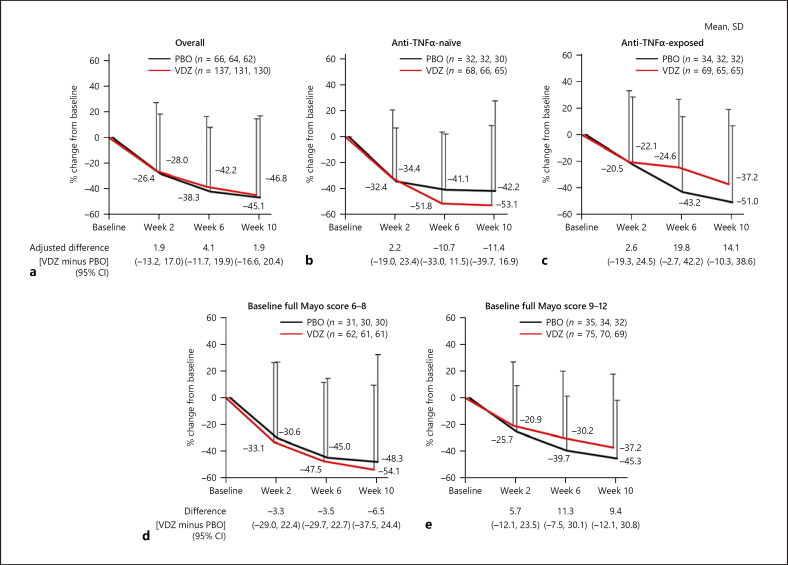

At baseline, 137 (83.5%) vedolizumab-treated and 66 (80.5%) placebo patients had RB subscore ≥1 and were analyzed at each visit. In this overall population, no notable differences in values for percentage change from baseline in Mayo RB subscores were observed between vedolizumab and placebo groups at all visits (Fig. 2a). In anti-TNFα-naive patients, numerically greater percentage decreases from baseline in RB subscore occurred with vedolizumab (n = 68) versus placebo (n = 32) at Weeks 6 and 10 (Fig. 2b). Conversely, the decrease in baseline RB scores in anti-TNFα-exposed patients receiving placebo (n = 34) was numerically greater than that in those receiving vedolizumab (n = 69) at Weeks 6 and 10 (Fig. 2c). No significant difference was seen in change from baseline in disease severity (full Mayo score 6–8 and 9–12) between the treatment groups (Fig. 2d, e). Online suppl. Figure 3 summarizes actual RB subscores over time for vedolizumab versus placebo.

Fig. 2.

Percentage change from baseline in Mayo RB subscore by visit (patients with RB subscore ≥1 at baseline) in overall population (a), anti-TNFα-naive patients (b), anti-TNFα-exposed patients (c), baseline full Mayo score 6–8 (d), and baseline full Mayo score 9–12 (e). CI, confidence interval; PBO, placebo; RB, rectal bleeding; SD, standard deviation; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha; VDZ, vedolizumab.

Composite SF and RB Subscores

In patients with SF subscore ≥2 and RB subscore ≥1 at baseline, a numerically higher proportion of patients in the vedolizumab group achieved the composite subscores of SF subscore ≤1 and RB subscore = 0 versus placebo at all time points (Fig. 3a). The proportion of anti-TNFα-naive patients who achieved composite SF subscore ≤1 and RB subscore = 0 was numerically higher in the vedolizumab group versus placebo at all time points: Week 2 (14.8%; 95% CI, 2.5, 27.0) and Week 6 (20.3%; 95% CI, 4.4, 36.2) (Fig. 3b). Conversely, the proportion of anti-TNFα-exposed patients with composite SF subscore ≤1 and RB subscore = 0 was numerically lower in the vedolizumab group versus placebo for all time points (−5.1%; 95% CI, −16.5, 6.3 at Week 2; −13.4%; 95% CI, −29.5, 2.7 at Week 6; and −7.3%; 95% CI −24.5, 9.9 at Week 10; Fig. 3c). The proportion of patients who achieved composite SF subscore ≤1 and RB subscore = 0 was numerically higher with vedolizumab versus placebo at all time points in patients with baseline full Mayo score 6–8 (Fig. 3d) and numerically higher with vedolizumab group versus placebo at Weeks 2 and 6 in those with baseline full Mayo score 9–12, although the proportion was lower than those with 6–8 (Fig. 3e).

Fig. 3.

Proportion of patients (with Mayo SF subscore ≥2 and RB subscore ≥1 at baseline) who achieved Mayo SF subscore ≤1 and RB subscore = 0, by visit in overall population (a), anti-TNFα-naive patients (b), anti-TNFα-exposed patients (c), baseline full Mayo score 6–8 (d), and baseline full Mayo score 9–12 (e). CI, confidence interval; PBO, placebo; RB, rectal bleeding; SF, stool frequency; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha; VDZ, vedolizumab.

Clinical Response, Clinical Remission, and Mucosal Healing at Week 10 (Stratified by Stool Frequency Subscore ≤1 and Rectal Bleeding Subscore = 0 at Week 2)

In patients who received vedolizumab, those with (vs. without) SF subscore ≤1 and RB subscore = 0 at Week 2 had numerically higher clinical response rates at Week 10 in the overall population, anti-TNFα-naive patients, and anti-TNFα-exposed patients (Table 2). This trend was also observed for clinical remission and mucosal healing rates at Week 10 in all groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical response, clinical remission, and mucosal healing at Week 10, according to SF subscore ≤1 and RB subscore = 0 at Week 2 in patients treated with vedolizumab

| SF subscore ≤1 and RB subscore = 0 at Week 2 | Clinical response at Week 10 | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % (95% CI) | |

| a Clinical response | ||

| Overall | ||

| Yes (n = 23) | 19 | 82.6 (61.2–95.1) |

| No (n = 139) | 46 | 33.1 (25.4–41.6) |

| Anti-TNFα-naive patients | ||

| Yes (n = 17) | 15 | 88.2 (63.6–98.5) |

| No (n = 60) | 27 | 45.0 (32.1–58.4) |

| Anti-TNFα-exposed patients | ||

| Yes (n = 6) | 4 | 66.7 (22.3–95.7) |

| No (n = 79) | 19 | 24.1 (15.1–35.0) |

| SF subscore ≤1 and RB subscore = 0 at week 2 | Clinical remission at Week 10 | |

| n | % (95% CI) | |

| b Clinical remission | ||

| Overall | ||

| Yes (n = 23) | 15 | 65.2 (42.7–83.6) |

| No (n = 139) | 15 | 10.8 (6.2–17.2) |

| Anti-TNFα-naive patients | ||

| Yes (n = 17) | 11 | 64.7 (38.3–85.8) |

| No (n = 60) | 11 | 18.3 (9.5–30.4) |

| Anti-TNFα-exposed patients | ||

| Yes (n = 6) | 4 | 66.7 (22.3–95.7) |

| No (n = 79) | 4 | 5.1 (1.4–12.5) |

| SF subscore ≤1 and RB subscore = 0 at Week 2 | Mucosal healing at Week 10 | |

| n | % (95% CI) | |

| c Mucosal healing | ||

| Overall | ||

| Yes (n = 23) | 20 | 87.0 (66.4–97.2) |

| No (n = 139) | 40 | 28.8 (21.4–37.1) |

| Anti-TNFα-naive patients | ||

| Yes (n = 17) | 15 | 88.2 (63.6–98.5) |

| No (n = 60) | 23 | 38.3 (26.1–51.8) |

| Anti-TNFα-exposed patients | ||

| Yes (n = 6) | 5 | 83.3 (35.9–99.6) |

| No (n = 79) | 17 | 21.5 (13.1–32.2) |

CI, confidence interval; RB, rectal bleeding; SF, stool frequency; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

Predictors of Symptom Response to Vedolizumab

Univariate analyses of predictors of UC outcome identified disease severity; previous anti-TNFα exposure; anti-TNFα failure; baseline partial and full Mayo scores, albumin, and SF subscore as significant variables (p ≤ 0.05) for achieving the composite of RB subscore = 0 and SF subscore ≤1 (Table 3). In multivariate analyses, baseline full Mayo score and previous anti-TNFα exposure remained significant (p ≤ 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Predictors of Mayo SF subscore ≤1 and RB subscore = 0 at Week 2 in patients treated with vedolizumab

| p value | Odds ratio | |||

| point estimate | 95% CI | |||

| lower | upper | |||

| Univariate analysis Age | 0.1927 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.01 |

| Sex (female vs. male) | 0.3801 | 1.49 | 0.61 | 3.61 |

| Smoker (current/ex-smoker vs. never smoked) | 0.9734 | 0.99 | 0.41 | 2.38 |

| UC duration | 0.9796 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 1.07 |

| UC duration (≥2 vs. <2 yr) | 0.4690 | 1.61 | 0.44 | 5.80 |

| UC duration (≥5 vs. <5 yr) | 0.2549 | 1.74 | 0.67 | 4.49 |

| Extraintestinal manifestations (no vs. yes) | 0.5066 | 1.40 | 0.52 | 3.79 |

| Disease severity based on full Mayo score (<10 vs. >10) | 0.0500 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 1.00 |

| Previous anti-TNFα exposure (no vs. yes) | 0.0091 | 3.73 | 1.39 | 10.03 |

| Anti-TNFα failure (no vs. yes) | 0.0108 | 3.62 | 1.35 | 9.74 |

| Corticosteroids (no vs. yes) | 0.7131 | 0.84 | 0.33 | 2.13 |

| Immunomodulator (no vs. yes) | 0.5846 | 1.28 | 0.53 | 3.12 |

| Baseline partial Mayo clinic score | <0.0001 | 0.38 | 0.24 | 0.60 |

| Baseline full Mayo score | <0.0001 | 0.44 | 0.29 | 0.65 |

| Baseline albumin, g/dL | 0.0032 | 9.33 | 2.11 | 41.18 |

| BMI | 0.3525 | 1.06 | 0.94 | 1.20 |

| Baseline endoscopy (moderate vs. severe) | 0.2560 | 1.84 | 0.64 | 5.26 |

| Baseline SF 1 versus 0 | 0.9613 | <0.01 | <0.01 | >9,999.99 |

| Baseline SF 2 versus 0 | 0.9678 | <0.01 | <0.01 | >9,999.99 |

| Baseline SF 3 versus 0 | 0.9934 | <0.01 | <0.01 | >9,999.99 |

| Baseline RB 1 versus 0 | 0.3758 | 0.60 | 0.19 | 1.87 |

| Baseline RB 2 versus 0 | 0.2387 | 0.48 | 0.14 | 1.62 |

| Baseline RB 3 versus 0 | 0.9381 | <0.01 | <0.01 | >9,999.99 |

| Baseline SF (non-severe vs. severe) | <0.0001 | 8.31 | 2.90 | 23.88 |

| Baseline RB (non-severe vs. severe) | 0.9596 | >9,999.99 | <0.01 | >9,999.99 |

| Disease localization (total colitis vs. left-sided colitis) | 0.3447 | 0.65 | 0.27 | 1.58 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||||

| Previous anti-TNFα exposure (no vs. yes) | 0.0252 | 3.32 | 1.16 | 9.50 |

| Baseline full Mayo score | 0.0001 | 0.44 | 0.29 | 0.67 |

Due to overlap between some predictors, previous anti-TNFα exposure, baseline full Mayo score, and baseline albumin were included in the multivariate analysis model. CI, confidence interval; RB, rectal bleeding; SF, stool frequency; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Discussion

In this post hoc analysis of a phase 3 study of vedolizumab in Japanese patients with UC, vedolizumab treatment resulted in symptomatic improvement, as shown by numerically greater decreases in SF subscore versus placebo as early as Week 2 and in RB subscore as soon as Week 6 in anti-TNFα-naive patients. Vedolizumab treatment also resulted in symptomatic response, as shown by increased proportion of patients with composite SF subscore ≤1 and RB subscore = 0 from Week 2 versus placebo, particularly in anti-TNFα-naive patients at Weeks 2 and 6.

The proportion of anti-TNFα-naive patients with composite SF subscore ≤1 and RB subscore = 0 in the vedolizumab and placebo groups was 22.1 and 7.3%, respectively, at Week 2, and 37.3 and 17.1%, respectively, at Week 6. These results are similar to those reported in the GEMINI 1 post hoc analysis of 22.3 and 6.6%, respectively, at Week 2, and 31.5 and 13.2%, respectively, at Week 6 [16]. Contrary to the GEMINI 1 post hoc analysis, however, the proportion of anti-TNFα-exposed patients with composite SF subscore ≤1 and RB subscore = 0 in the present study was numerically higher in the placebo group than in the vedolizumab group. The reason for this has not been identified, but it may be due to differences in baseline disease activity between anti-TNFα-exposed patients in the vedolizumab and placebo groups. For example, a higher proportion of anti-TNFα-exposed patients in the placebo group had a Mayo endoscopic subscore of 2 compared with the vedolizumab group (65.9 vs. 55.3%) and more anti-TNFα-exposed patients in the placebo group had levels of C-reactive protein of <3 mg/L compared with the vedolizumab group (61.0 vs. 38.8%, respectively). As previously stated [10], patients who received placebo in the anti-TNFα-exposed subgroup may have had less severe baseline disease activity compared with those in the vedolizumab group, thus showing a more favorable, spontaneous symptomatic improvement. However, although results suggest that both RB and SF are considered predictive factors of disease activity in patients with less severe symptoms [21], it may take longer to achieve an RB subscore = 0 than SF subscore ≤1.

In addition to subgroup analysis with prior use of anti-TNFα, we also conducted subgroup analysis with baseline full Mayo score, because this score was identified as a predictive factor of symptomatic improvement in both this study and the post hoc analysis of GEMINI 1 [16]. A numerically higher proportion of patients in both treatment arms achieved a composite SF subscore ≤1 and RB subscore = 0 in the subgroup with baseline full Mayo score 6–8 than in that with baseline full Mayo score 9–12. In both subgroups, the proportion of patients who achieved composite SF subscore ≤1 and RB subscore = 0 was numerically higher in the vedolizumab group versus the placebo group at all time points, with the exception of patients with baseline full Mayo score 9–12 at Week 10. In GEMINI 1, patients with baseline Mayo score <9 showed greater clinical response rate at Week 6 than those with baseline full Mayo score ≥9 [11]. These results may suggest the difficulty in treating severe disease with vedolizumab and taking more time to respond to treatment. However, careful consideration may be needed to interpret our results. Status of prior use of anti-TNFα may affect these results, since the proportion of anti-TNFα-naive patients was greater in the subgroup with baseline full Mayo score 6–8 than in those with 9–12.

Patients with (vs. without) SF subscore ≤1 and RB subscore = 0 at Week 2 had a higher clinical response, clinical remission, and mucosal healing rates at Week 10, for all patient groups. In patients with SF subscore ≤1 and RB subscore = 0 at Week 2, both clinical response rate and mucosal healing rate were highest in anti-TNFα-naive patients at Week 10 (both 88.2%). Our results suggest that early symptomatic improvement (SF subscore ≤1 and RB subscore = 0 at Week 2) predicts treatment response at Week 10. Furthermore, even among patients who did not achieve early symptomatic improvement, a proportion achieved clinical response, clinical remission, and mucosal healing at Week 10, suggesting that administration of vedolizumab beyond Week 2 helps patients achieve these long-term outcomes.

Multivariate analysis showed that baseline full Mayo score and previous anti-TNFα-exposure were significant predictors of symptomatic improvement (SF subscore ≤1 and RB subscore = 0) at Week 2. In the GEMINI 1 post hoc analysis, baseline full Mayo score was also identified as a predictive factor of symptomatic improvement [16], supporting the validity of our results.

A limitation of this post hoc analysis is that the sample size was small, as it was calculated based on estimated clinical response rates of the vedolizumab and placebo groups at Week 10. Prospective studies that are powered to investigate individual symptom scores are warranted to confirm the findings of this analysis.

The trend for early symptomatic response with vedolizumab in Japanese patients with UC in the present post hoc analysis is consistent with that observed in the recent post hoc analysis of GEMINI 1 [16]. This observation suggests that a similar trend may be observed in other Asian populations such as Chinese and Koreans, and thus, the results of the present post hoc analysis may be meaningful for the clinical application of vedolizumab in Asia. Our results also indicate that gut-selective lymphocyte-trafficking agents such as vedolizumab can induce rapid symptomatic response, which in turn may improve patient satisfaction with therapy [18] in some patients, particularly in anti-TNFα-naive patients with UC [16]. The rapid symptomatic response observed with vedolizumab in the present study is similar to that observed with infliximab in patients with moderate-to-severe UC in an analysis of phase 3 trial data [22].

Although it is recommended that the full standard 3-dose induction course of vedolizumab be completed before a final decision on clinical benefit is assessed at Week 14 for patients who show a modest initial improvement, notably for anti-TNF exposed patients [8, 9, 10], alternative treatment might be considered for those who do not show marked response at Week 2 because of lower probability of clinical response, remission, and further mucosal healing. Implications on the positioning of vedolizumab in treatment algorithms and guidelines will require additional experience and evidence.

Data Sharing Statement

Takeda makes patient-level, de-identified data sets and associated documents available after applicable marketing approvals and commercial availability have been received, an opportunity for the primary publication of the research has been allowed, and other criteria have been met as set forth in Takeda's Data Sharing Policy (see https://www.takedaclinicaltrials.com/ for details). To obtain access, researchers must submit a legitimate academic research proposal for adjudication by an independent review panel, who will review the scientific merit of the research and the requestor's qualifications and conflict of interest that can result in potential bias. Once approved, qualified researchers who sign a data sharing agreement are provided access to these data in a secure research environment.

Statement of Ethics

Before patients were recruited to the phase 3 study, the study protocol was reviewed and approved by an institutional review board of each study site [10]. This study was conducted in compliance with all Institutional Review Board regulations and in accordance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent. For patients aged <20 years, written informed consent was additionally obtained from their parents or legal guardians.

Institutional Review Board for the following study sites provided approval of the study protocol: Sapporo-Kosei General Hospital; Sapporo Higashi Tokushukai Hospital; Kunimoto Hospital; Hirosaki National Hospital; Sendai Medical Center; Tokyo Yamate Medical Center; Kitasato University Kitasato Institute Hospital; NTT Medical Center Tokyo; Kitasato University East Hospital; Yokohama City University Medical Center; Ofuna Chuo Hospital; Matsuda Hospital; Ieda Hospital; Yokoyama Memorial Hospital; Miyata lin; Kyoto Medical Center; Senri Hospital; Infusion Clinic; Murano Clinic; Fukuyama Medical Center; JA Hiroshima General Hospital; Tokuyama Central Hospital; Ehime Prefectural Central Hospital; Fukuoka University Chikushi Hospital; Fukuoka University Hospital; Saiseikai Fukuoka General Hospital; Kitakyushu Municipal Medical Center; Saga University Hospital; Saga-Ken Medical Center Koseikan; Nagasaki University Hospital; Oita Red Cross Hospital; Nanpuh Hospital; Sameshima Hospital; Nippon Koukan Hospital; Tokyo Teishin Hospital; Tohoku University Hospital; Hamamatsu Minami Hospital; Takagi Clinic; Toho University Medical Center, Sakura Hospital; Yamanashi Prefectural Central Hospital; Hyogo College of Medicine Hospital; Kumamoto Red Cross Hospital; Sapporo Hokuyu Hospital; E. Iwashita Gastrointestinal Rectocolonic Clinic; Chikamori Hospital; Shunkaikai Inoue Hospital; Osaka City University Hospital; Oji General Hospital; Akashi Medical Center; Jichi Medical University Hospital; Keio University Hospital; Terada Hospital; Gokeikai Osaka Kaisei Hospital; Moriguchi Keijinkai Hospital; Kasai Shoikai Hospital; Tokyo Medical And Dental University, Medical Hospital; Teine Keijinkai Clinic; Fukui Prefectural Hospital; Shinbeppu Hospital; Sapporo City General Hospital; Fujisawa City Hospital; Tokai Memorial Hospital; Komatsu Municipal Hospital; Kinki Central Hospital; Hakodate Central General Hospital; Kure Medical Center and Chugoku Cancer Center; Kobe Century Memorial Hospital; Bell Land General Hospital; Kagawa Rosai Hospital; Kagawa Prefectural Central Hospital; Himeji Central Hospital; Kurume General Hospital; The Kansai Electric Power Co., Inc., Hospital; Nagoya University Hospital; Sagamihara Kyodo Hospital; Kawasaki Municipal Hospital; Hiroshima City Hiroshima Citizens Hospital; Wakayama Medical University Hospital; Hakodate Goryoukaku Hospital; Osaka Hospital; Okayama University Hospital; Shiga University of Medical Sciences Hospital; Kyushu Rosai Hospital; Osaka City General Hospital; Kitasato University Hospital; Matsushima Clinic; Sapporo Tokushukai Hospital; Fukuoka Tokushukai Medical Center; Yokohama City University Hospital; Kumagaya General Hospital; JA Shizuoka Kohseiren Enshu Hospital; Yokkaichi Hazu Medical Center; Chibana Clinic; The Jikei University Kashiwa Hospital; Chiba University Hospital; Kagoshima Kouseiren Hospital; Kumamoto General Hospital; Takasaki General Medical Center; Tokito Clinic; and Ashikaga Red Cross Hospital.

Conflict of Interest Statement

M.N. has received honoraria from Kissei Pharma (Kissei), Takeda Pharmaceutical (Takeda), Kyorin Pharmaceutical (Kyorin), Mochida Pharmaceutical (Mochida), AbbVie GK (AbbVie), Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma (Mitsubishi Tanabe), Nippon Kayaku, Asahi Kasei Medical (Asahi Kasei), Zeria Pharmaceutical (Zeria), Astellas Pharma (Astellas), Nichi-Iko Pharmaceutical, and Janssen Pharmaceutical (Janssen). K.W. has received honoraria and research funding from AbbVie, Mitsubishi Tanabe, EA Pharma (EA), Takeda, Kyorin, Mochida, and Janssen, and research funding from Astellas, JIMRO, Zeria, Otsuka Pharmaceutical (Otsuka), and Asahi Kasei. S.M. has received honoraria and research funding from Janssen and Takeda; honoraria from Mitsubishi Tanabe and Mochida; and research funding from Pfizer Japan (Pfizer). H.O. has received honoraria from Takeda and research funding from Mitsubishi Tanabe, Mochida, Pfizer, and AbbVie. T.K. has received honoraria and research funding from Mitsubishi Tanabe, Miyarisan Pharmaceutical (Miyarisan), and Takeda; honoraria from Astellas and AstraZeneca; and research funding from EN Otsuka, Ezaki Glico, Otsuka, AbbVie, Mochida, Kyorin, Daiichi Sankyo, Nippon Kayaku, Yakult, Zeria, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Ono Pharmaceutical, EA, Eisai, JIMRO, Chugai Pharmaceutical (Chugai), and UCB Japan (UCB). T.M. has received honoraria and research funding from EA, Ajinomoto Seiyaku (Ajinomoto), AbbVie, Eisai, Kyorin, Zeria, Takeda, Mitsubishi Tanabe, and Mochida; research funding from Miyarisan, Otsuka, Asahi Kasei, Astellas, AstraZeneca, MSD, JIMRO, Taiho Pharmaceutical (Taiho), Daiichi Sankyo, Nippon Kayaku, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, UCB, and Chugai. Y.S. has received honoraria and research funding from Mitsubishi Tanabe, AbbVie, EA, and Mochida; honoraria from Janssen, Zeria, and Kyorin; and research funding from JIMRO, Kissei, and Nippon Kayaku. P.P., L.U., S.S., M.S., T.H., and J.F. are employees of Takeda. T.H. has received honoraria and research funding from AbbVie, JIMRO, and Zeria; honoraria from Takeda, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Aspen Japan, Ferring, Gilead Sciences, Kissei, Mochida, Nippon Kayaku, Janssen, and Pfizer; and research funding from EA and Otsuka. M.W. has received honoraria and research funding from Mitsubishi Tanabe, Takeda, EA, Zeria, and Gilead Sciences; honoraria from Ajinomoto, Janssen, Celltrion Healthcare, and Pfizer; and research funding from Nippon Kayaku, Mochida, Kissei, Miyarisan, Asahi Kasei, JIMRO, Kyorin, AbbVie, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Kaken Pharmaceutical, Alfresa Pharma, Ayumi Pharmaceutical, Astellas, MSD, Daiichi Sankyo, Taiho, Toray Industries, Chugai, and Fujirebio.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Takeda was involved in the design of the study and contributed to the development and approval of the report; however, the final decision to submit the report was made by the authors.

Author Contributions

M.N.: data acquisition, interpretation, and drafting manuscript; K.W., S.M., H.O., T.K., T.M., Y.S., T.H., and M.W.: study design, interpretation, and manuscript writing; P.P. and L.U.: interpretation and drafting manuscript; S.S.: data analysis, interpretation, and drafting manuscript; J.F.: conception and manuscript writing; and M.S. and T.H.: study design, interpretation, and manuscript writing.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the patients who participated in the trial and their families and the staff at study sites in Japan who supported this study. The authors are also grateful to the following colleagues at Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.: Akira Nishimura, Yutaka Aritomi, and Kazunori Oda for study protocol development; Takahiro Araki for collection and assembly of the data; Mitsuhiro Mori and Yuya Mori for patient enrollment; and Masataka Igeta and Kenkichi Sugiura for reviewing the study protocol/CSR review/SAP development and for statistical analysis. Medical writing support was provided by Nicholas Crabb, MSc, of FireKite, an Ashfield company, part of UDG Healthcare plc, during the development of the manuscript, which was funded by Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., in compliance with Good Publication Practice 3 Ethical Guidelines (Battisti WP, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:461–4).

References

- 1.Colombel JF, Keir ME, Scherl A, Zhao R, de Hertogh G, Faubion WA, et al. Discrepancies between patient-reported outcomes, and endoscopic and histological appearance in UC. Gut. 2017 Dec;66((12)):2063–8. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yarlas A, D'Haens G, Willian MK, Teynor M. Health-related quality of life and work-related outcomes for patients with mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis and remission status following short-term and long-term treatment with multimatrix mesalamine: a prospective, open-label study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018 Jan 18;24((2)):450–63. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izx041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stange EF, Travis SPL, Vermeire S, Reinisch W, Geboes K, Barakauskiene A, et al. European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis: definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis. 2008 Mar;2((1)):1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Jong MJ, Huibregtse R, Masclee AAM, Jonkers DMAE, Pierik MJ. Patient-reported outcome measures for use in clinical trials and clinical practice in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16((5)):648–63.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williet N, Sandborn WJ, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Patient-reported outcomes as primary end points in clinical trials of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014 Aug;12((8)):1246–56.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jairath V, Khanna R, Zou GY, Stitt L, Mosli M, Vandervoort MK, et al. Development of interim patient-reported outcome measures for the assessment of ulcerative colitis disease activity in clinical trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015 Nov;42((10)):1200–10. doi: 10.1111/apt.13408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands BE, Reinisch W, Bemelman W, Bryant RV, et al. Selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (STRIDE): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015 Sep;110((9)):1324–38. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.PMDA Entyvio for intravenous infusion 300 mg. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeda Entyvio® (vedolizumab) approved in Japan for the treatment of patients with moderately to severely active Crohn's Disease. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Motoya S, Watanabe K, Ogata H, Kanai T, Matsui T, Suzuki Y, et al. Vedolizumab in Japanese patients with ulcerative colitis: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. PLoS One. 2019;14((2)):e0212989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, Hanauer S, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 22;369((8)):699–710. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amiot A, Grimaud JC, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Filippi J, Pariente B, Roblin X, et al. Effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab induction therapy for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Nov;14((11)):1593–e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amiot A, Serrero M, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Filippi J, Pariente B, Roblin X, et al. One-year effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective multicentre cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017 Aug;46((3)):310–21. doi: 10.1111/apt.14167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orchard TR, van der Geest SA, Travis SP. Randomised clinical trial: early assessment after 2 weeks of high-dose mesalazine for moderately active ulcerative colitis: new light on a familiar question. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 May;33((9)):1028–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Probert CS, Dignass AU, Lindgren S, Oudkerk Pool M, Marteau P. Combined oral and rectal mesalazine for the treatment of mild-to-moderately active ulcerative colitis: rapid symptom resolution and improvements in quality of life. J Crohns Colitis. 2014 Mar;8((3)):200–7. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feagan BG, Lasch K, Lissoos T, Cao C, Wojtowicz AM, Khalid JM, et al. Rapid response to vedolizumab therapy in biologic-naive patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 May 29;17((1)):130–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Danese S, Fiorino G, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Early intervention in Crohn's disease: towards disease modification trials. Gut. 2017 Dec;66((12)):2179–87. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gray JR, Leung E, Scales J. Treatment of ulcerative colitis from the patient's perspective: a survey of preferences and satisfaction with therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009 May 15;29((10)):1114–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.03972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D'Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Geboes K, Hanauer SB, Irvine EJ, et al. A review of activity indices and efficacy end points for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007 Feb;132((2)):763–86. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gøtzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010 Mar 23;340:c869. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Jong MJ, Roosen D, Degens JHRJ, van den Heuvel TRA, Romberg-Camps M, Hameeteman W, et al. Development and validation of a patient-reported score to screen for mucosal inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2018 Nov 24;13((5)):555–63. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh S, Proudfoot JA, Dulai PS, Xu R, Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, et al. Efficacy and speed of induction of remission of infliximab vs golimumab for patients with ulcerative colitis, based on data from clinical trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 May 17;18((2)):30529–4. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data