Abstract

Context

Tangwang Mingmu granule (TWMM), a traditional Chinese medicine, has been widely used in the treatment of diabetic retinopathy (DR), the most common microvascular complication in diabetes mellitus.

Objective

To establish a method to select target compounds from herbs for a pharmacokinetic study using network pharmacology, which could be applied in clinical settings.

Materials and methods

First, UPLC/Q Exactive Q-Orbitrap and GCMS 2010 were used to determine the non-volatile and volatile ingredients of TWMM. Based on the identified compounds, network pharmacology was used to screen the key compounds and targets of TWMM in the treatment of DR. Based on the compound-target-pathway network and identification of components emigrant into blood, the potential compound markers in vivo were chosen. Then, Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats were administrated of TWMM at a 9.6 g/kg dose to investigating pharmacokinetic parameters using the UPLC-QQQ-MS.

Results

Ninety and forty-five compounds were identified by UPLC-MS and GC-MS, respectively. Based on the network pharmacology, nine compounds with a degree value above 15 were screened and implied that these compounds are the most active in DR treatment. Moreover, criteria of degree value greater than 7 were applied, and PTGS2, NOS2, AKT1, ESR1, TNF, and MAPK14 were inferred as the core targets in treating DR. After identification of components absorbed into blood, luteolin and formononetin were selected and used to investigate the pharmacokinetic parameters of TWMM after its oral administration.

Conclusions

The reported strategy provides a method that combines ingredient profiling, network pharmacology, and pharmacokinetics to determine luteolin and formononetin as the pharmacokinetic markers of TWMM. This strategy provides a clinically relevant methodology that allows for the screening of pharmacokinetic markers in Chinese medicines.

Keywords: Chemical profiling, marker, herb medicine, luteolin, formononetin

Introduction

Pharmacokinetic research plays a critical role in assessing drug clinical dosing parameters, side effects, and treatment mechanisms in vivo (Ding et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2020). To understand the pharmacokinetic parameters of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of a drug product, the high-content-ingredients that emigrate into the circulatory system are generally selected as target compounds in a pharmacokinetic study (Jiang et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2020). In certain instances, the activity of the high content ingredients does not match the clinical application of the herbal medicine, resulting in difficulties in obtaining pharmacokinetic indicators to guide clinical use. Occasionally, broad action(s) of detected compounds, such as immune-stimulatory and antioxidative activities are reported without provision of any proof to support their specific clinical contribution in the herb or prescription medicine for the management of diseases such as DR (Yuan et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2019). For example, the clinical symptoms of chronic nephritis have been reported to be alleviated by shenyanyihao oral solution. Ten high-content compounds including stachyBine, danshensu, chlorogenic acid, protocatechuic acid, plantamajoside, aesculetin, isoquercitrin, ferulic acid, baicalin, and baicalein were selected for a pharmacokinetic study which resulted in little clinical relevance (Jiang et al. 2020). Similarly, Liu et al. (2020) reported that Chaihu-Shugan-San could be used to treat depression. In this study, nine high content ingredients were selected as markers and determined in plasma samples. However, most of these compounds were not interrelated to the treatment of depression. Thus, establishing a method that can determine clinically relevant compounds in pharmacokinetic studies of complex drugs is warranted.

Network pharmacology analyzes the network of the biological system and selects specific signal nodes to design multi-target drug molecules based on the theory of systems biology. It can demonstrate compound-target-pathway networks, which can be used to explore the mechanism of various compounds in treating multi-target diseases from a perspective of systems biology and biological network balance (Yang et al. 2019). In addition, this comprehensive analysis can be applied in the screening of active ingredients and therapeutic targets as well as in determining the compound mechanism of action (Pan et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2020). Zhang et al. (2021) reported that Shuang-Huang-Lian water extract (SHL) considerably improves the symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection. In their study, baicalin, sweroside, chlorogenic acid, forsythoside A, and phillyrin were selected as the potential active compounds through network pharmacology. Consequently, H1N1-infected mice were administered these five compounds to verify their therapeutic effects. They found that these five compounds had the same therapeutical effects as SHL, causing the release of cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, and ultimately contributing to an increased survival rate. Therefore, network pharmacology is capable of identifying active ingredients responsible for pharmacological activity in mixed medicines.

DR is one of the most serious complications of diabetes mellitus, eventually leading to vision loss and even blindness if not managed (Sabanayagam et al. 2019). Since visual sense involves all aspects of our daily lives, the deterioration of vision is likely to seriously affect the quality of life in these patients. However, the pathogenesis of DR is not clear, and current symptomatic therapy of the disease is ineffective (Whitehead et al. 2018; Nawaz et al. 2019). Furthermore, the available drugs for the treatment of DR are deficient and unilateral (Stitt et al. 2016). The commonly used treatment for DR, an intraocular injection containing anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), neither works in early DR nor restrains the development of DR (Dulull et al. 2019). In addition, multiple intraocular injections raise the risk of serious intraocular infection. Other treatments such as fundus laser photocoagulation involve the risk of destroying the normal function of the retina (Shalchi et al. 2020; Mones et al. 2021). Currently, all the available treatment options for DR may result in poor treatment compliance and disease prognosis (Fajnkuchen et al. 2020). Therefore, novel orally administered therapy is an urgent need in attempting to manage DR.

Herbal medicine has certain advantages in the treatment of chronic diseases with complex mechanisms (Li and Weng 2017). TWMM, an herbal product derived from Mimenghuafang, has been applied clinically for 20 years as a decoction (Song et al. 2015). It contains seven herbs, i.e., Astragalus propinquus Schischkin (Leguminosae), Coptis chinensis Franch. (Ranunculaceae), Buddleja officinalis Maxim. (Scrophulariaceae), Cinnamomum cassia (L.) J.Presl (Lauraceae), Prunus mume (Siebold) Siebold & Zucc. (Rosaceae), Ligustrum lucidum W.T.Aiton (Oleaceae) and Leonurus japonicus Houtt (Lamiaceae). Clinical applications show that TWMM can significantly improve the vision of patients with DR, alleviate clinical symptoms such as asthenopia, and improve the state of blood vessels in the fundus (Chen et al. 2017). TWMM has been shown to possess a curative effect in the management of DR. The retinal protective effects of TWMM in diabetic rats was postulated to result from the upregulation of SOCS3 expression, inhibition of the JAK/STAT signalling pathway, and further inhibition of VEGF expression (Chen et al. 2017). Furthermore, TWMM was shown to restore the ratio of VEGFR-1/VEGFR-2, thus maintaining the normal activities of endothelial cells and inhibiting the abnormal proliferation of capillaries in the retina (Song et al. 2015).

In this study, identification of active compounds that are responsible for pharmacological activity in medicinal mixtures and network pharmacology was applied before embarking on a pharmacokinetic study. TWMM was studied as a model and the observed results provide a theoretical foundation for the clinical application of TWMM. Furthermore, markers that were screened by the established method were successfully applied in the pharmacokinetic study and possessed similar clinical indications of the herbal mixture. Overall, this study revealed the pharmacological properties of drugs in a clinically relevant manner and provided a reference for the pharmacokinetic study of multi-component drug mixtures.

Materials and methods

Materials and reagents

The TWMM was provided by Beijing HanDian Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Chlorogenic acid, linarin, luteolin, jaspolyside, tolbutamide, stachydrine, magnoflorine, calycosin-7-O-β-d-glucoside, stepharanine, jatrorrhizine, epiberberine, columbamine, ononin, berberine, palmatine, berberrubine, calycosin, formononetin, 2α-hydroxyoleanic acid, hydroxytyrosol, salidroside, luteolin-7-O-glucoside, verbascoside, specnuezhenide, oleuropein, physcion, oleonuezhenide, astragaloside IV, astragaloside II, isoastragaloside II, astragaloside I, luteolin, formononetin, and tolbutamide (purity ≥ 98%) were purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd and Sichuan Weikeqi Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd. Acetonitrile and formic acid both in HPLC grade were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ, USA). Ultrapure water was prepared using a Milli-Q water purification system (Millipore, Bredford, MA, USA). Other reagents were all analytical grade.

Preparation of standard and sample solutions

Preparation for qualitative analysis

Ten mg of each standard was dissolved in 10 mL of methanol solution. Next, an equal volume of stock solution was mixed in a 10 mL volumetric flask to acquire a mixed standard solution with a certain concentration. Samples of TWMM (20 mg) were added to 10 mL of 70% methanol for UPLC-MS and n-hexane for GC-MS analyses, respectively. The samples were exposed to ultrasound extraction for 15 min and centrifuged at 15,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, followed by subsequent collection of the supernatants. All the solutions were stored at −20 °C before the experiment.

Preparation for pharmacokinetic analysis

Analytical standards (10 mg) of oleuropein, chlorogenic acid, formononetin, verbascoside, linarin, luteolin, jaspolyside, specnuezhenide, and tolbutamide (internal standard, IS) were dissolved in a 10 mL volumetric flask with methanol. An appropriate volume of solution containing oleuropein, chlorogenic acid, formononetin, verbascoside, linarin, luteolin, jaspolyside, and specnuezhenide solution was diluted to obtain a stock solution. Subsequently, the mixture was serially diluted to prepare the reference working solutions and then tolbutamide was added to achieve an IS concentration of 5 μg/mL.

Analytical conditions

UPLC-MS conditions for identification of non-volatile components of TWMM

The identification of non-volatile components was determined using a UPLC/Q Exactive Q-Orbitrap system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Chromatographic separation was performed on a 1.8 µm HSS T3 analytical column (100 mm × 2.1 i.d.). The mobile phase was composed of 0.1% (v/v) acetic acid in water (A) and acetonitrile (B) under the following gradient conditions: 0–30 min, 8–20% B; 30–35 min, 20–25% B; 35–45 min, 25–80% B; 45–45.5 min, 80–8% B; 45.5–49 min, 8–8% B. The flow rate was set at 0.4 mL/min and the temperatures of the autosampler and analytical column were maintained at 35 °C and 4 °C, respectively. In addition, the HESI of the Q-Orbitrap mass spectrometer was set to both negative and positive ionisation modes. The ion source parameters were as follows: spray voltage, +2.9 kV/–2.8 kV; auxiliary gas rate, 10 L/h; sheath gas rate, 35 L/h; auxiliary gas temperature, 400 °C; capillary temperature, 350 °C; normalised collision energy, 10/20/40 V, and mass range, 150–1500 m/z.

GC-MS conditions for identification of volatile components of TWMM

The profiling of volatile components of TWMM was performed on a Shimadzu GCMS 2010 solution (Shimadzu, Japan). Separation was conducted on a DB-17 column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm). The oven temperature program setting is shown in Table 1. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.4 mL/min. The ion source and interface temperatures were set at 230 °C and 250 °C, respectively.

Table 1.

The oven temperature program of GCMS–QP 2010.

| Temperature (°C) | Duration (min) | Flow rate (°C/min) |

|---|---|---|

| 40–40 | 3 | 0 |

| 40–106 | 11 | 6 |

| 106–142.6 | 12.2 | 3 |

| 142.6–142.6 | 1 | 0 |

| 142.6–180 | 6.2 | 6 |

| 180–200 | 5 | 4 |

| 200–235 | 17.5 | 2 |

Network pharmacology

All targets of all compounds constituting TWMM were screened by using the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database (TCMSP, http://lsp.nwu.edu.cn/tcmspsearch.php), which provided the chemical compounds and their related target proteins. Related targets of DR were predicted and screened using the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD, http://ctdbase.org/), Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man database (OMIM, https://omim.org/), and DrugBank Database (DBD, https://www.drugbank.ca/). The intersection targets were imported into Venny 2.1.0 software (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html). The protein-protein interaction network (PPI) of intersection targets was created using the STRING Database platform (http://string-db.org/, ver. 11.0) with medium confidence (0.4) to remove the isolated target proteins. Furthermore, the drug-disease crossover genes were annotated and visualised using the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software (ver. 2019, Redwood City, CA, USA). Lastly, the compound-target-pathway network was established using the Cytoscape interaction network visualisation software (http://cytoscape.org/, ver. 3.5.2).

UHPLC-MS/MS conditions for pharmacokinetics

Chromatographic separation was performed using an ACQUITY UPLC H-Class system equipped with a 1.8 μm HSS T3 analytical column (100 mm × 2.1 i.d., Waters Corporation, Milford, USA). The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% (v/v) aqueous formic acid (A) and acetonitrile (B) under the following gradient conditions: 0–2 min, 8–13% B; 2–7 min, 13–50% B; 7–9 min, 50–95% B; 9–11 min, 95–95% B; 11–12.5 min, 95–8% B; 12.5–15 min, 8–8% B. The flow rate was set at 0.3 mL/min and the column and autosampler temperatures were maintained at 35 °C and 15 °C, respectively. ESI source was set to negative ionisation mode while the analysis was performed using multiple reaction monitorin. Ion spray voltage (3000 V), capillary temperature (450 °C), and the source parameters of the nine compounds are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mass spectra properties of 8 compounds and tolbutamide (IS).

| Compound | Parention (m/z) | Daughterion (m/z) | CV (V) | CE (V) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oleuropein | 539.22 | 138.97 | 2 | 28 |

| Chlorogenic acid | 353.13 | 190.99 | 2 | 20 |

| Formononetin | 267.11 | 251.97 | 74 | 20 |

| Verbascoside | 623.24 | 160.94 | 2 | 40 |

| Linarin | 591.21 | 283.03 | 94 | 18 |

| Luteolin | 285.08 | 132.95 | 2 | 32 |

| Jaspolyside | 403.16 | 223.04 | 2 | 12 |

| Specnuezhenide | 685.27 | 523.16 | 82 | 20 |

| Tolbutamide | 269.14 | 169.93 | 74 | 20 |

Data analysis

The data obtained from the UPLC/Q-Orbitrap MS was imported into Xcalibur 4.0 software for analysis. Furthermore, the constituents acquired using GCMS-QP 2010 were profiled by comparison using the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) database. The pharmacokinetic data were processed through MassLynx 4.1, and DAS 2.0 software was used to calculate the pharmacokinetic parameters according to the compartment model.

Method validation for pharmacokinetics

Method specificity was assessed by comparing the chromatograms of blank plasma, blank plasma spiked with oleuropein, chlorogenic acid, formononetin, verbascoside, linarin, luteolin, jaspolyside, specnuezhenide, and IS, and plasma after oral administration of TWMM. The calibration curves were assessed at eight concentration levels using the correlation coefficient (r). The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) could fulfil the analytical requirements and achieved reliable accuracy and precision with a signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) ≥ 10. To determine intra- and inter-day precision and accuracy, six replicate quality control (QC) samples at three concentrations were prepared. Inter- and intra-day precision was evaluated by determining relative standard deviation (RSD) values, while accuracy was expressed in terms of the relative error (RE). The extraction recoveries were determined using three concentration levels and calculated by comparing the peak area of extracted samples with post-extracted spiked samples. Subsequently, matrix effects were assessed using the peak area of post-extracted spiked samples contrasted with QC samples at the three concentration levels. The stability test of QC samples at the three concentration levels was as follows: storage at 25 °C for 4 h, storage in an autosampler for 12 h, freeze-thaw cycle for three times, and storage at −80 °C for 7 d.

Pharmacokinetic study

Six male SD rats (average weight: 220 ± 10 g) were acquired from Beijing Vital-River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. All rats were acclimatized to an environmentally controlled laboratory for a week. Following this period, the rats were exposed to fasting conditions for 12 h but were allowed free access to water before the experiment. The rats were orally administered TWMM at a dose of 9.6 g/kg. Blood samples (300 µL) were collected into heparinized centrifuge tubes from the fossa orbitalis at pre-dose and 0.03, 0.08, 0.17, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, and 36 h intervals. The samples were immediately centrifuged at 6000 g for 10 min at 4 °C and the supernatants were transferred to clean centrifuge tubes.

Each 100 µL plasma sample was mixed with 20 µL of methanol, 20 µL of IS (5 µg/mL), and 600 µL acetonitrile. The mixtures were centrifuged at 15,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C after being vortexed for 3 min. The obtained supernatants were transferred to clean 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes, followed by evaporation under a milt nitrogen stream. Next, the obtained residues were individually redissolved in 100 µL of methanol and centrifuged at 15,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C after vortexed for 3 min. Lastly, 10 µL of individual supernatant was injected for analysis.

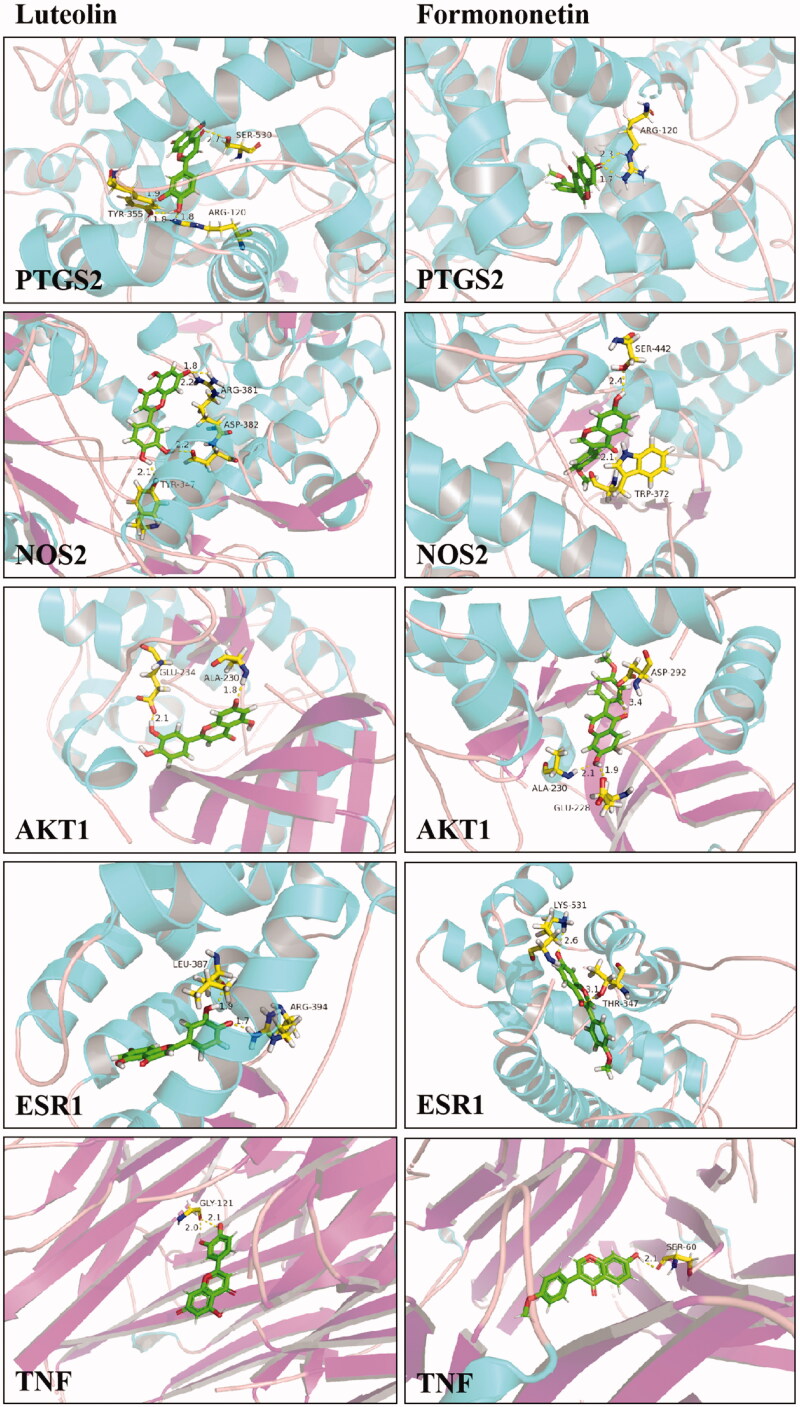

Molecular docking

The 3D structures of luteolin and formononetin were obtained from the ZINC database (http://zinc.docking.org/). The conformation of the top 5 proteins screened by network pharmacology was collected from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) database: PTGS2 (PDB ID: 5IKR), NOS2 (PDB ID: 4NOS), AKT1 (PDB ID: 3CQW), ESR1 (PDB ID: 1XP9), and TNF (PDB ID: 2AZ5). The CDOCKER program of Discovery Studio 2019 was applied to investigating molecular docking parameters after molecule and protein preparing procedures. Then, PyMol 2.4.0 was used to visualize and verified the result of molecular docking.

Assay of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS)

The generation of ROS was detected using dichloro-dihydro-fluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA, reactive oxygen species assay kit, Solarbio, Beijing) as per manufacturer instructions. In this study, we seeded HUVEC cells in a 96-well plate at 7 × 103 per well. The cells were treated with luteolin (20, 10, 5 µM) or formononetin (40, 20, 10 µM) for 2 h followed by 30 mM high glucose (HG) for 24 h and incubated for 20 minutes with DCFH-DA (10 mM) at 37 °C. DCF fluorescence was assessed at F488/525 nm by using a bioassay multi-detection fluorescent plate reader (Tecan Spark, Switzerland).

Luciferase reporter assay

DH5a competent cells (1 × 106) were seeded into 6-well plates. When cell confluence reached about 70%, cells were co-transfected with pGL4.37, pGL4.75 following the manufacturer’s instructions (Lipofectamine RNAiMAX, Invitrogen, USA). Luciferase assays were performed with the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Luminescent signals were quantified by a luminometer (Glomax, Promega, Madison, WI, USA), and each value from the firefly luciferase construct was normalized by Renilla luciferase assay.

Results and discussion

To determine pharmacokinetic markers, we comprehensively performed chemical profiling and then applied network pharmacology to screen key compounds and targets for the treatment of DR using TWMM.

Qualitative analysis

UPLC-Q-Orbitrap-based screening and identification

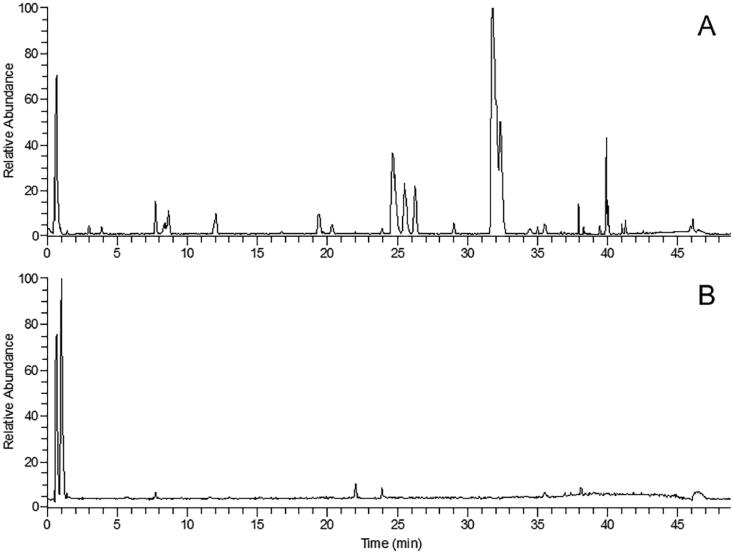

The extract of TWMM was analyzed using UPLC Q-Orbitrap MS/MS. The total ion current (TIC) chromatograms obtained in both positive and negative modes are shown in Figure 1. The 90 components can be divided into 8 classes: 27 flavonoids, 17 iridoids, 16 alkaloids, 10 triterpenoids, 9 phenols, 9 organic acids, 1 phenylethanol, and 1 anthraquinone. Twenty-six components were identified by matching retention times, quasi-molecular ions, and MS/MS fragments with the standards. The other 64 components were identified by comparing their retention times and MS/MS fragments with those reported in the literature and databases. As shown in Tables 3 and 4, a total of 38 compounds were identified in positive ion mode and 52 compounds in negative ion mode. As an example of the identification process, compound no. 23 with detected ions at m/z 321.0996 and 292.0969 could be identified as berberine by comparison with the standard. The fragment at m/z 321.0996 was generated by the loss of CH3, and m/z 292.0969 was obtained by further loss of HCO.

Figure 1.

The TIC chromatogram of UPLC-MS in both positive mode (A) and negative mode (B) for TWMM.

Table 3.

Compounds in TWMM detected by LC/MS in positive ion mode.

| No. | RT (min) |

Formula | [M + H]+ (m/z) |

Identification | Mass error (ppm) |

MS2 fragments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1* | 0.64 | C7H14O2N | 144.1019 | Stachydrine | 0.588 | 144.1020,102.5555,98.0973,84.0814,72.0814,58.0660 |

| 2 | 0.68 | C6H12O2N | 130.0862 | L (-)-pipecolinic acid | –0.424 | 84.0814,67.0550,56.0503 |

| 3* | 8.62 | C20H24O4N | 342.1697 | Magnoflorine | 0.454 | 342.1701,297.1123,282.0889,265.0861,255.1029, 237.0910,219.0806 |

| 4 | 11.92 | C14H22O5N3 | 312.1569 | Leonurine | 4.686 | 312.1569,181.0495,132.1133,114.1029,97.0765,72.0815 |

| 5 | 15.50 | C21H26O4N | 356.1859 | Tetrahydropalmatine | 0.773 | 356.1859,339.1075,204.1021,165.0914,151.0751 |

| 6 | 16.43 | C15H13O4 | 257.0806 | Liquiritigenin | –0.916 | 147.0440,137.0234,119.0494 |

| 7 | 16.80 | C21H19O11 | 447.0921 | Astragalin | –0.196 | 285.0758,253.0492,137.0235,91.0576 |

| 8* | 16.80 | C22H23O10 | 447.1302 | Calycosin-7-O-β-D-glucoside | 3.638 | 285.0758,270.0524,253.0492,225.0559,137.0235,91.0576 |

| 9 | 16.94 | C20H20O5N | 354.1334 | Protopine | –0.591 | 354.1334,339.1098,324.0861,310.1075 |

| 10 | 18.69 | C19H18O4N | 324.1230 | Stepharanine isomer | –0.045 | 324.1230,308.0879,294.0760,280.0950,266.0808 |

| 11 | 18.86 | C28H35O15 | 611.1995 | Hesperidin | 4.014 | 355.0691,239.0948,129.0551 |

| 12 | 19.10 | C19H18O4N | 324.1236 | Stepharanine isomer | 1.652 | 324.1236,308.0895,294.0761,280.0962,266.0808 |

| 13* | 19.78 | C19H18O4N | 324.1229 | Stepharanine | –0.353 | 324.1229,308.0916,294.0762,280.0969,266.0806 |

| 14 | 19.89 | C15H11O6 | 287.0549 | Kaempferol | –0.503 | 287.0549,153.0182,84.9604 |

| 15 | 21.23 | C19H18O4N | 324.1226 | Stepharanine isomer | –1.279 | 324.1223,308.0914,294.0761,280.0964,266.0792 |

| 16 | 24.63 | C19H14O4N | 320.0918 | Coptisine | 0.205 | 320.0918,318.0763,292.0968,277.0735,262.0863,249.0792 |

| 17 | 25.45 | C22H28O4N | 370.2014 | Corydaline | 0.176 | 370.2014,206.1178,165.0548 |

| 18* | 25.48 | C20H20O4N | 338.1385 | Jatrorrhizine | –1.019 | 338.1383,323.1143,308.0917,294.1123,279.0882 |

| 19* | 25.65 | C20H18O4N | 336.1231 | Epiberberine | 0.135 | 336.1231,320.0918,308.0914,294.1123,279.0893 |

| 20* | 26.26 | C20H20O4N | 338.1385 | Columbamine | –0.487 | 338.1385,323.1143,308.0916,294.1124,279.0887 |

| 21* | 28.45 | C22H23O9 | 431.1335 | Ononin | –0.368 | 269.0809,254.0572,253.0503,237.0552,213.0910 |

| 22 | 29.68 | C21H20O4N | 350.1389 | Dehydrocavidine | 0.472 | 350.1389,335.1131,334.1075,306.1124 |

| 23 | 30.50 | C15H11O4 | 255.0653 | Daidzein | 0.489 | 255.0653,237.0546,227.0707 |

| 24* | 31.82 | C20H18O4N | 336.1232 | Berbine | 0.403 | 336.1232,320.0918,306.0760,292.0969,278.0814 |

| 25* | 32.33 | C21H22O4N | 352.1542 | Palmatine | 0.924 | 352.1547,336.1232,322.1075,308.1283,294.1129 |

| 26* | 32.40 | C19H16O4N | 322.1072 | Berberrubine | –0.573 | 294.1126,278.0811,102.9706,84.9604,74.9316 |

| 27* | 34.40 | C16H13O5 | 285.0750 | Calycosin | –0.246 | 285.0757,270.0522,253.0496,225.0546, 214.0621,197.0599,137.0234 |

| 28 | 35.22 | C22H24O4N | 366.1699 | Dehydrocorydaline | –0.259 | 366.1699,350.1387,336.1228 |

| 29 | 35.52 | C21H20O4N | 350.1389 | Dehydrocavidine isomer | 0.587 | 350.1389,334.1076,306.1125 |

| 30 | 35.59 | C28H33O14 | 593.1863 | Linarin | –0.307 | 447.1289,285.0760,129.0548,85.0290 |

| 31 | 38.04 | C15H11O5 | 271.0602 | Baicalein | 0.185 | 271.0602,208.9540,146.9613,69.0706 |

| 32 | 38.61 | C16H13O6 | 301.0709 | Chrysoriol | 0.749 | 286.0471,258.0525,229.0499,213.0543 |

| 33* | 39.39 | C16H13O4 | 269.0810 | Formononetin | 0.463 | 269.0810,254.0569,237.0547,226.0625,213.0911, 197.0599,137.0235,118.0416,107.0496 |

| 34 | 39.51 | C16H29O2 | 253.2160 | Hexadecadienoic acid | –0.816 | 109.1015,95.0861 |

| 35 | 40.76 | C21H23O8 | 403.1406 | Nobiletin | 4.678 | 403.1406,388.1141,373.0919,327.0851 |

| 36 | 41.43 | C30H47O3 | 455.3535 | 3-oxo-olean-12-en-28-oic acid/3-keto-oleanolic acid | 3.246 | 455.3535,437.3405,229.1949,201.1633,191.1785,1 89.1638,159.1168,133.1013,109.1016,95.0861 |

| 37* | 44.37 | C30H47O4 | 471.3473 | 2α-hydroxyoleanic acid | 0.856 | 471.3473,425.3422,235.1693,189.1639 |

| 38 | 45.42 | C30H49O3 | 457.3671 | Ursolic acid/oleanolic acid | –1.141 | 411.3626,203.1795,201.1645,189.1642,175.1489, 161.1327,149.1324,147.1172,135.1171,121.1014 |

*Compounds identified by comparison with reference standards.

Table 4.

Compounds in TWMM detected by LC/MS in negative ion mode.

| No. | RT (min) |

Formula | [M − H]− (m/z) |

Identification | Mass error (ppm) |

MS2 fragments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 39 | 0.89 | C4H5O5 | 133.0131 | Malic acid | –0.374 | 133.0131,71.0125 |

| 40 | 1.94 | C8H7O4 | 167.0343 | Vanillic acid | 2.483 | 123.0440,81.0330 |

| 41 | 2.29 | C16H23O10 | 375.1302 | Loganic acid or isomer | 4.336 | 113.0233,101.0233,85.0283,71.0125,59.0126,343.1819,304.3728, 280.5988,186.9071 |

| 42* | 2.46 | C8H9O3 | 153.0550 | Hydroxytyrosol | 2.478 | 126.9022,123.0440,122.0362,108.0204,96.9588,95.0492 |

| 43 | 2.70 | C16H23O10 | 375.1302 | Loganic acid or isomer | 1.627 | 151.0749,113.0229,101.0232,85.0279,71.0125,59.0126 |

| 44 | 2.87 | C16H17O9 | 353.0887 | Neochlorogenic acid | 5.640 | 191.0554,179.0342,173.0451,161.0233,155.0337, 135.0440,133.0282 |

| 45* | 2.94 | C14H19O7 | 299.1139 | Salidroside | 4.582 | 113.0232,101.0232,89.0231,162.8383, 126.8801,119.0491,71.0125,59.0125 |

| 46 | 3.38 | C21H27O13 | 487.1470 | Cistanoside F | 4.891 | 245.0459,203.0345,179.0342,161.0234,135.0440,113.0231 |

| 47 | 3.56 | C10H13O5 | 213.0764 | Nuzhenal A or isomer | 3.051 | 215.0094,171.0195,144.0080,122.8930,61.9870,59.0125 |

| 48 | 3.76 | C7H5O3 | 137.0241 | Protocatechualdehyde | 5.324 | 137.0240,119.0112,93.0333,136.0155,108.0204,66.0366, 61.9870 |

| 49 | 5.27 | C16H17O9 | 353.0887 | Chlorogenic acid | 5.640 | 191.0554,179.0342,161.0233,135.0436,127.0389,102.9473, 85.0282 |

| 50 | 5.72 | C17H19O9 | 367.1036 | 3-O-Feruloylquinic acid | 3.382 | 193.0500,134.0362 |

| 51 | 6.06 | C16H17O9 | 353.0887 | Cryptochlorogenic acid | 5.640 | 191.0555,179.0342,173.0448,161.0237,155.0339, 135.0440,111.0440,93.0332 |

| 52 | 6.17 | C9H7O4 | 179.0343 | Caffeic acid | 2.317 | 143.8641,141.8670,135.0441,134.0361, 107.0489,103.9190,99.9245,90.9232 |

| 53 | 9.12 | C16H23O10 | 375.1302 | Loganic acid or isomer | 1.627 | 85.0282,59.0123 |

| 54 | 10.36 | C9H7O3 | 163.0393 | Coumaric acid | 2.020 | 119.0491,108.9363,93.0333 |

| 55 | 15.38 | C21H19O12 | 463.0899 | Isoquercetin | 5.976 | 463.0899,301.0351,300.0275 |

| 56 | 15.75 | C35H45O20 | 785.2507 | Echinacoside | 1.019 | 785.2507,179.0344,161.0235,623.6187,398.2031,244.7829 |

| 57 | 16.65 | C25H31O14 | 555.1724 | 10-Hydroxyoleuropein/ligustalosideA | 2.824 | 223.0593,151.0391,101.0229,89.0230,538.7717,431.5094, 367.6147,330.2907,274.4666,59.0124 |

| 58 | 18.33 | C25H29O15 | 569.1519 | Oleuropeinic acid | 3.169 | 363.1089,331.0827,221.0084,209.0451, 177.0184,151.0391,133.0286,123.0440,195.0293 |

| 59 | 19.02 | C27H29O16 | 609.1462 | Rutin | 2.017 | 609.1462,301.0349,300.0276,394.4090, 343.0453,302.0385,178.9981 |

| 60 | 19.53 | C21H19O12 | 463.0887 | Hyperoside | 3.450 | 300.0277,271.0255,255.0313,178.9990,151.0028 |

| 61 | 19.57 | C31H41O18 | 701.2300 | Neonuzhenide | 1.767 | 539.1758,469.1359,135.0440,101.0230, 701.2300,437.1450,315.1085 |

| 62* | 19.94 | C21H19O11 | 447.0939 | Luteolin-7-O-glucoside | 3.830 | 447.0939,285.0405,327.0508,286.0441,284.0328 |

| 63 | 20.28 | C34H43O19 | 755.2415 | Forsythoside B | 1.224 | 593.2094,179.0337,161.0233 |

| 64* | 21.99 | C29H35O15 | 623.1981 | Verbascoside | 1.626 | 623.1981,461.1670,315.1082,179.0338, 161.0236,135.0441,113.0232 |

| 65 | 23.26 | C25H29O14 | 553.1572 | Ligustrosidic acid | 3.648 | 347.1141,329.1022,315.0883,235.0255, 209.0450,195.0293,177.0186,151.0392,101.0230 |

| 66* | 23.94 | C31H41O17 | 685.2358 | Specnuezhenide | 2.881 | 523.1809,453.1404,421.1508,299.1136, 223.0606,181.0498,179.0555,121.0283,89.0231 |

| 67 | 24.07 | C27H29O14 | 577.1570 | Apigenin-7-O-rutinoside | 3.115 | 577.1570,269.0457,516.5734,383.2473,311.0563, 270.0490,171.9616 |

| 68 | 24.69 | C21H19O10 | 431.0985 | Apigenin-7-O-glucoside | 2.939 | 431.0985,269.0445,268.0378,311.0562,197.8080,160.8412 |

| 69* | 29.45 | C25H31O13 | 539.1780 | Oleuropein | 3.863 | 345.0996,327.0869,307.0824,275.0928, 223.0607,191.0342,153.0544, 149.0234,139.0389,119.0377 |

| 70 | 34.01 | C27H35O14 | 583.2039 | [M-H + HCOOH]-ligulucidumosideA | 3.031 | 403.1255,223.0605,151.0390,123.0441, 101.0233,351.1075,319.0839,179.0547 |

| 71* | 34.49 | C16H11O5 | 283.0617 | Physcion | 5.653 | 240.0419,268.0377,239.0345,211.0395,184.0522,148.0156 |

| 72 | 34.66 | C31H39O15 | 651.2278 | Martynoside | –0.870 | 475.1821,193.0499,175.0393,160.0155 |

| 73 | 34.86 | C25H31O12 | 523.1827 | Ligustroside | 3.244 | 291.0876,259.0979,223.0607,171.0294,139.0394,101.0232, 89.0229 |

| 74 | 35.10 | C15H9O6 | 285.0408 | Luteoline | 4.931 | 285.0408,175.0393,151.0026,133.0280,107.0126,268.0375, 162.8384 |

| 75 | 35.68 | C33H43O18 | 727.2466 | Acetylnicotiflorine | 3.038 | 495.1502,341.1252,299.1148,281.1036,223.0607,121.0280, 89.0229,611.7267,463.1580 |

| 76 | 36.36 | C25H27O12 | 519.1516 | 6′-O-trans-Cinnamoyl-8-epikingisidicacidor isomer | 3.655 | 189.0554,183.0653,165.0550,161.0559, 147.0441,121.0647,69.0332,59.0125 |

| 77* | 36.90 | C48H63O27 | 1071.3563 | Oleonuezhenide | 1.118 | 523.1824,453.1409,299.1137,223.0608, |

| 78 | 37.14 | C30H25O13 | 593.1309 | Tiliroside | 3.191 | 593.1309,447.0937,285.0403 |

| 79 | 37.34 | C48H63O27 | 1071.3567 | Oleonuezhenide or isomer | 1.463 | 523.1823,453.1409,421.1511,299.1137,223.0610 |

| 80 | 38.12 | C15H9O5 | 269.0459 | Apigenin | 5.390 | 269.0459,201.0550,183.0446,151.0027,149.0234, 117.0333,107.0125 |

| 81* | 39.33 | C42H69O16 | 829.4594 | Astragaloside IV | 1.613 | 829.4594,783.4568 |

| 82 | 39.70 | C10H13O5 | 213.0764 | Nuzhenal A or isomer | 3.051 | 215.0093,122.8930,171.0191,144.0081,61.9871 |

| 83* | 39.87 | C44H71O17 | 871.4654 | Astragaloside II | –3.657 | 871.4654,825.4614 |

| 84 | 40.14 | C48H77O18 | 941.5126 | Soyasaponin I | 2.324 | 941.5126,705.7660,116.9273 |

| 85* | 40.48 | C44H71O17 | 871.4692 | Isoastragaloside II | 0.692 | 871.4692,825.4577 |

| 86* | 41.48 | C46H73O18 | 913.4818 | Astragaloside I | 2.921 | 913.4818,867.4780 |

| 87 | 41.79 | C46H73O18 | 913.4813 | IsoastragalosideI | 2.319 | 913.4813,867.4747 |

| 88 | 41.92 | C30H47O5 | 487.3441 | Tormentic acid | 4.635 | 487.3441,488.3474,470.3380,469.3336,425.3817, 394.9604,324.6631,274.6215,113.2870 |

| 89 | 44.28 | C39H53O7 | 633.3798 | 3-O-cis-p-Coumaroyltormentic acid/3-O-trans-p-Coumaroyltormentic acid | 1.862 | 633.3798,145.0280,580.6879,461.3018, 365.2326,162.8382,116.9270 |

| 90 | 46.08 | C39H53O6 | 617.3853 | 3β-O-trans-p-Coumaroylmaslinicacidor isomer/3β-O-cis-p-Coumaroylmaslinicacidor isomer | 1.886 | 617.3848,145.0286,412.5469,315.0490,303.2346,241.0108 |

*Compounds identified by comparison with reference standards.

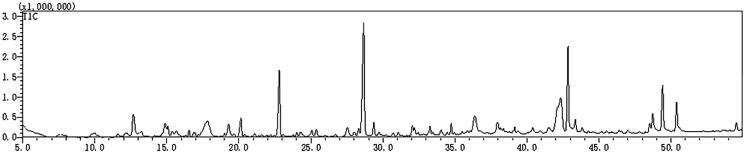

GC-MS/MS-based screening and identification

The volatile components of TWMM were detected by GC-MS 2010, and 45 compounds were identified using the NIST database. The GC-MS chromatogram of TIC traces is depicted in Figure 2 and the compounds identified from TWMM are listed in Table 5. Peak area normalization was applied to determine the relative content of each compound.

Figure 2.

The TIC chromatogram of GC-MS for TWMM.

Table 5.

Compounds in TWMM detected by GC/MS.

| No. | RT (min) | Formula | Molecular weight (m/z) | Identification | SI | Retention index | Ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 91 | 9.77 | C6H8O3 | 128.126 | Glycidyl acrylate | 85 | 865 | 0.24 |

| 92 | 11.57 | C3H6O2 | 74.078 | Acetol | 91 | 698 | 0.41 |

| 93 | 12.17 | C9H17NO7 | 251.234 | Muramic acid | 76 | 2221 | 0.52 |

| 94 | 12.68 | C5H6O2 | 98.100 | Furfuryl alcohol | 80 | 885 | 2.78 |

| 95 | 13.22 | C7H14O2 | 130.185 | Methyl 2-ethylbutanoate | 81 | 820 | 1.01 |

| 96 | 14.88 | C2H6O2 | 62.068 | Ethylene glycol | 89 | 705 | 1.50 |

| 97 | 15.06 | C6H8O4 | 144.125 | 2,4-Dihydroxy-2,5-dimethyl-3(2H)-furan-3-one | 88 | 1173 | 0.82 |

| 98 | 15.36 | C5H6O2 | 98.100 | 1,2-Cyclooctanedione | 93 | 942 | 0.62 |

| 99 | 15.66 | C6H16O2Si | 148.275 | Diethoxydimethylsilane | 75 | 679 | 0.49 |

| 100 | 16.54 | C6H6O2 | 110.111 | 5-Methyl furfural | 96 | 920 | 0.47 |

| 101 | 16.85 | C5H4O3 | 112.083 | Citraconic anhydride | 90 | 1068 | 0.31 |

| 102 | 16.96 | C4H6O2 | 86.090 | Gamma-Butyrolactone | 83 | 825 | 0.18 |

| 103 | 17.84 | C3H8O3 | 92.094 | Glycerol | 80 | 967 | 1.68 |

| 104 | 19.30 | C6H8O3 | 128.126 | 4-Hydroxy-2,5-dimethylfuran-3(2H)-one | 84 | 1022 | 1.48 |

| 105 | 20.14 | C6H6O3 | 126.110 | Maltol | 84 | 1063 | 1.60 |

| 106 | 22.81 | C6H8O4 | 144.125 | 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl | 87 | 1269 | 5.21 |

| 107 | 23.76 | C5H10O | 86.132 | Cyclopentanol | 85 | 788 | 0.19 |

| 108 | 24.03 | C6H6O4 | 142.109 | 3,5-Dihydroxy-2-methylpyran-4-one | 88 | 1193 | 0.34 |

| 109 | 25.07 | C7H12O3 | 144.168 | Ethyl 2-methylacetoacetate | 80 | 956 | 0.58 |

| 110 | 25.38 | C8H8O | 120.148 | Coumaran | 92 | 1036 | 0.74 |

| 111 | 28.31 | C5H10O4 | 134.130 | 1,2,3-Propanetriol,1-acetate | 88 | 1091 | 0.66 |

| 112 | 28.67 | C6H6O3 | 126.110 | 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural | 90 | 1163 | 10.67 |

| 113 | 29.36 | C9H10O2 | 150.174 | 1-(4-Hydroxy-3-methylphenyl) ethanone | 89 | 1363 | 0.98 |

| 114 | 32.19 | C8H10O3 | 154.163 | Syringol | 87 | 1279 | 0.53 |

| 115 | 32.44 | C6H12O5 | 164.156 | 1,4-Anhydro-D-sorbitol | 82 | 1530 | 0.34 |

| 116 | 33.28 | C9H8O2 | 148.159 | Cinnamic acid | 94 | 1357 | 0.70 |

| 117 | 33.48 | C14H22O | 206.324 | 3,5-Di-tert-Butylphenol | 88 | 1555 | 0.25 |

| 118 | 34.45 | C6H9NO3 | 143.141 | Methyl DL-pyroglutamate | 87 | 1091 | 0.25 |

| 119 | 34.75 | C8H10O2 | 138.160 | 4-Hydroxyphenyl ethanol | 94 | 1356 | 0.78 |

| 120 | 34.97 | C13H28O | 200.361 | 1-Hexoxy-5-methylhexane | 85 | 1325 | 0.25 |

| 121 | 35.87 | C6H6N2O | 122.125 | Nicotinamide | 94 | 1197 | 0.50 |

| 122 | 36.38 | C4H9NO5 | 151.118 | 2-(Hydroxymethyl)-2-nitropropan-1,3-diol | 78 | 1444 | 1.80 |

| 123 | 37.97 | C6H10O5 | 162.141 | Levoglucosan | 89 | 1404 | 1.49 |

| 124 | 38.18 | C8H8O4 | 168.147 | 3-Hydroxy-4-methoxybenzoic acid | 83 | 1560 | 0.64 |

| 125 | 39.14 | C12H20O7 | 276.283 | Triethyl citrate | 88 | 1808 | 0.47 |

| 126 | 40.41 | C7H14O6 | 194.180 | Methyl-β-D-glucopyranoside | 80 | 1714 | 0.81 |

| 127 | 42.16 | C11H22O2 | 186.291 | 3-Methyldecanoic acid | 69 | 1407 | 3.24 |

| 128 | 42.34 | C7H14O6 | 194.182 | Methyl α-D-mannofuranoside | 78 | 1667 | 5.56 |

| 129 | 42.85 | C38H68O8 | 652.942 | l-Ascorbyl dipalmitate | 91 | 4765 | 6.59 |

| 130 | 43.36 | C12H15NO3 | 221.252 | Methyl N-acetyl-L-phenylalaninate | 82 | 1794 | 1.25 |

| 131 | 48.53 | C18H36O2 | 284.477 | Stearic acid | 88 | 2167 | 0.73 |

| 132 | 48.73 | C18H34O2 | 282.461 | Oleic acid | 89 | 2175 | 1.88 |

| 133 | 48.73 | C18H34O2 | 282.461 | Elaidic Acid | 89 | 2175 | 1.02 |

| 134 | 49.42 | C18H32O2 | 280.445 | Linoleic acid | 93 | 2183 | 3.73 |

| 135 | 50.39 | C18H30O2 | 278.430 | α-Linolenic acid | 95 | 2191 | 2.16 |

Network analysis

Screening of active ingredients and targets

The 135 identified components were used as the foundation of network pharmacology. To acquire the formula-disease-related genes, the identified compounds were added to the TCMSP database to screen active ingredients and related targets. Following this, a total of 68 compounds and 287 targets were retrieved. Further, 646 genes related to DR were acquired from the CTD, OMIM, and DrugBank databases. Subsequently, after the intersection, 57 shared targets were obtained.

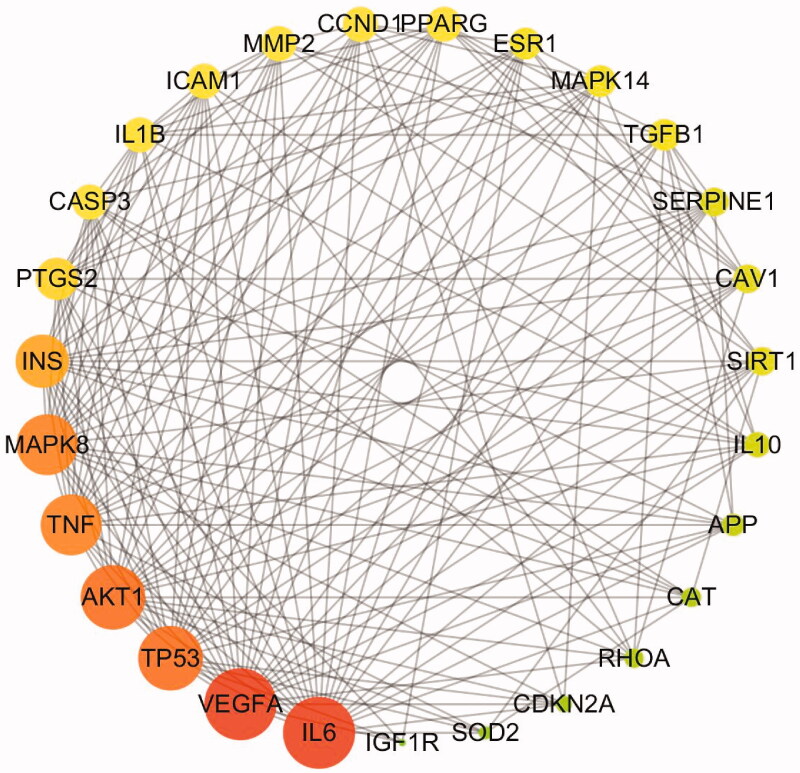

Obtaining key targets

The STRING database was used to form the intersection gene targets into a complex protein-protein network. The core gene targets are shown in Figure 3. The minimum confidence was set at 0.4 and Cytoscape 3.5.4 was used for further screening using the following node criteria: betweenness centrality ≥ 0.04, closeness centrality ≥ 0.6, and degree ≥ 27. Consequently, a total of 27 proteins were acquired as key candidate targets of DR. The 27 key targets are shown in Figure 4 and are listed in Table 6.

Figure 3.

The PPI network of 57 intersection gene targets (colour indicates query proteins and first shell of interactors; filled nodes indicate some 3D structure is known or predicted; line thickness indicates the strength of data support).

Figure 4.

The 27 predicted key targets of TWMM in the therapy of DR (point size represents the degree value; colour from red to green represents the correlation from high to low).

Table 6.

The core targets of TWMM in treating diabetic retinopathy.

| Gene official symbol |

UniProtKB | Gene official symbol |

UniProtKB | Gene official symbol |

UniProtKB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL6 | P05231 | IL1B | P01584 | CAV1 | Q03135 |

| VEGFA | P15692 | ICAM1 | P05362 | SIRT1 | Q96EB6 |

| TP53 | P04637 | MMP2 | P08253 | IL10 | P22301 |

| AKT1 | P31749 | CCND1 | P24385 | APP | P05067 |

| TNF | P01375 | PPARG | P37231 | CAT | P04040 |

| MAPK8 | P45983 | ESR1 | P03372 | RHOA | P61586 |

| INS | P01308 | MAPK14 | Q16539 | CDKN2A | P42771 |

| PTGS2 | P35354 | TGFB1 | P01137 | SOD2 | P04179 |

| CASP3 | P42574 | SERPINE1 | P05121 | IGF1R | P08069 |

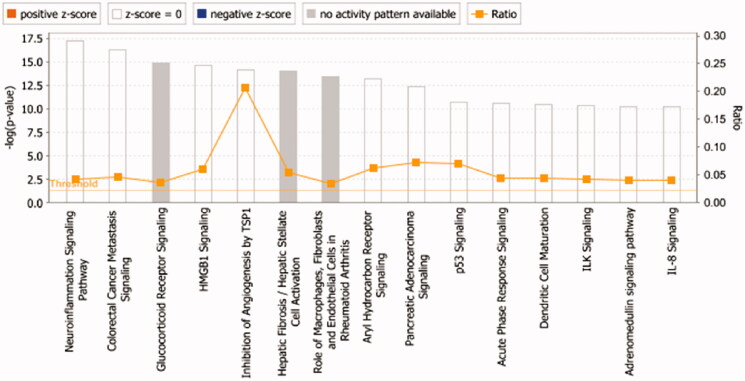

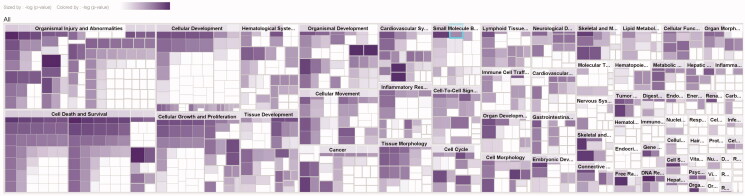

Core analysis and map of diseases & functions

The 27 key targets are analyzed by the "Core Analysis" function in IPA. As shown in Figure 5, the top ten signalling pathways associated with TWMM and DR are listed: (1) Neuroinflammation Signalling Pathway; (2) Coloractal Cancer Metastasis Signalling; (3) Glucocorticoid Receptor Signalling; (4) HMGB1 Signalling; (5) Inhibition of Angiogenesis by TSP1; (6) Hepatic Fibrosis/Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation; (7) Role of Macrophages, Fibroblasts and Endothelial Cells in Rheumatoid Arthritis; (8) Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Signalling; (9) Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Signalling (pancreatic cancer signalling); (10) P53 Signalling. Due to the large number of pathways involved, the disease pathways were screened based on the number of targets involved and their correlation with DR, among which the neuroinflammatory pathway, the inhibitory effect of TSP1 on angiogenesis, and the glucocorticoid receptor signalling pathway were of high relevance.

Figure 5.

The core analysis of early DR treated with TWMM (–Log p-value represents the pathway correlation; ratio represents the ratio of the number of molecules to the total number of molecules in the pathway).

A total of 72 functional entries related to DR were obtained by predicting the diseases and functions map of 27 core targets by IPA, namely organismal injury and abnormalities, cell death and survival, cellular development, cellular growth and proliferation, hematological system development, tissue development, organismal development, cellular movement, etc. As shown in Figure 6, it can be seen that the treatment of early DR by TWMM may be closely related to the apoptosis and proliferation of cells, the neogenesis of tissues and the process of the hematological system.

Figure 6.

The map of diseases & functions (darker colour indicates smaller p-value).

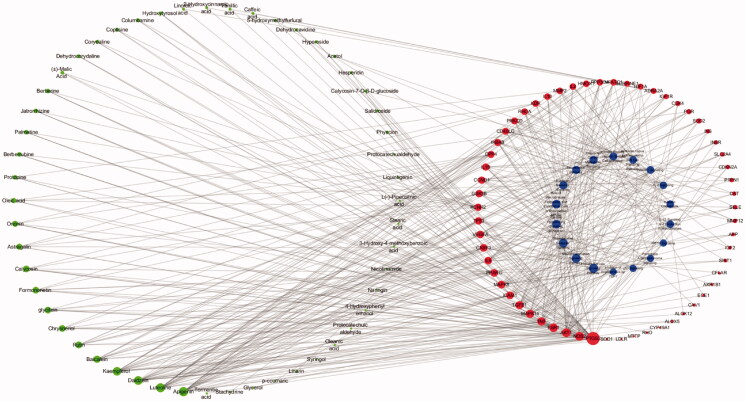

Construction of a compound-target-pathway network

As shown in Figure 7, a holistic compound-target-pathway network was framed by merging three networks to clarify the factors related to DR. The network is composed of 141 nodes and 477 edges. In the network analysis, the degree and betweenness centrality were selected to be the criteria indicators. The greater the value, the more critical the targets are. After sorting by degree and betweenness centrality, apigenin (degree: 22, betweenness centrality: 8.05E-02), luteolin (degree: 21, betweenness centrality: 5.99E-02), daidzein (degree: 19, betweenness centrality: 9.24E-02), kaempferol (degree: 18, betweenness centrality: 6.57E-02), baicalein (degree: 10, betweenness centrality: 2.81E-02), rutin (degree: 8, betweenness centrality: 2.35E-02), chrysoeriol (degree:7, betweenness centrality: 6.84E-03), glycitein (degree: 7, betweenness centrality: 8.52E-03) and formononetin (degree: 7, betweenness centrality: 1.27E-02) possess greater value of degree and betweenness. was suggested to play an important role in the activity of TWMM during the treatment of DR. Moreover, the top 6 targets sorted by degree value were PTGS2, NOS2, AKT1, ESR1, TNF, and MAPK14, which were inferred to be the most active targets. Based on the network and IPA analyses, the hepatic fibrosis signalling pathway, neuroinflammation signalling pathway, and glucocorticoid receptor signalling pathway were predicted as primary pathways involved in therapy.

Figure 7.

The compound-target-pathway network of TWMM in the treatment of DR (the left circle represents compounds; the outer circle of the right side represents the gene targets; the inner circle of the right side represents related pathways; point size from big to small represents the correlation from high to low).

Luteolin has been reported to inhibit proliferation and angiogenesis in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), human retinal microvascular endothelial cells (HRMECs), and retinal vascular endothelial rhesus (RF/6A) cells induced by VEGF (Bagli et al. 2004; Zhou et al. 2016). In addition, it was found to inhibit the advanced glycation end product (AGE)-forming of sorbitol and DPPH radical scavenging in rat lens (Hwang et al. 2019). Formononetin was reported to possess hypolipidemic, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant activity, which can improve the clinical symptoms of DR. In addition, formononetin was shown to attenuate inflammatory responses by inhibiting the expression of interleukin (IL)-1β and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (IcaM-1) at both protein and gene levels (Yang et al. 2005). Furthermore, treatment using formononetin for 16 weeks could ameliorate the clinical symptoms of hyperglycaemia and insulin resistance in diabetic animals. Moreover, oxidative stress burden was reduced by increased SIRT1 expression after oral administration of formononetin (Oza and Kulkarni 2019). Apigenin was reported to possess substantial anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity via activation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 and haem oxygenase-1 (Li et al. 2020), while kaempferol was shown to reduce inflammatory and fibrogenic responses in NRK-52E cells induced by high glucose (Luo et al. 2021). The present results indicate that TWMM has multiple activities that can improve retinal microvascular function in DR.

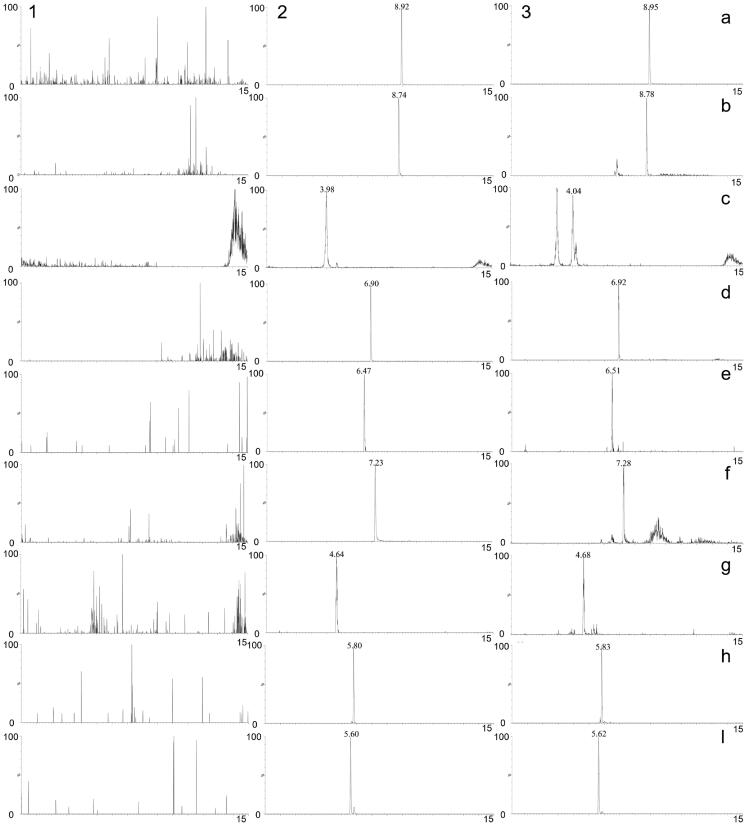

Bioanalytical method validation

The chromatograms of blank plasma, blank plasma spiked with the eight compounds and IS, and plasma after oral administration of TWMM are shown in Figure 8. The resultant chromatograms show that no significant peak interfered with the analysis.

Figure 8.

MRM chromatograms of tolbutamide (a), formononetin (b), chlorogenic acid (c), linarin (d), oleuropein (e), luteolin (f), jaspolyside (g), specnuezhenide (h) and verbascoside (i). (1) Blank plasma, (2) blank plasma spiked with the analytes and IS, (3) plasma sample after oral administration of TWMM.

The calibration curves of eight compounds were assessed by linear regression analysis with a weight factor of 1/x2. As shown in Table 7, all analytes had good linearity over the investigated range, and the correlation coefficient (r) of all calibration curves was greater than 0.9906.

Table 7.

Calibration curves, correlation coefficients, linear ranges and LLOQ of 8 compounds.

| Compounds | Calibration curve | r | Linear range (ng/mL) |

LLOQ (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oleuropein | y = 0.094x–0.021 | 0.9934 | 0.25–100 | 0.2 |

| Chlorogenic acid | y = 0.064x–0.057 | 0.9906 | 0.5–200 | 0.3 |

| Formononetin | y = 0.709x–0.180 | 0.9988 | 0.5–200 | 0.3 |

| Verbascoside | y = 0.086x–0.092 | 0.9987 | 1–400 | 1.0 |

| Linarin | y = 0.177x–0.058 | 0.9990 | 0.5–200 | 0.2 |

| Luteolin | y = 1.031x–0.334 | 0.9971 | 0.5–200 | 0.2 |

| Jaspolyside | y = 0.044x–0.024 | 0.9915 | 0.5–200 | 0.2 |

| Specnuezhenide | y = 0.079x–0.038 | 0.9932 | 0.5–200 | 0.2 |

The intra- and inter-day precision and accuracy at each investigated concentration level are shown in Table 8. The intra- and inter-day accuracy (RE) ranged between −13.3% and 13.3%, while the precision (RSD%) was less than 13.5%. The above results corroborate the accuracy and precision of the method.

Table 8.

Precision and accuracy of 8 compounds in rat plasma (n = 6).

| Compounds | Spiked concentration (ng/mL) |

Intra-day |

Inter-day |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured (ng/mL) |

RE (%) |

RSD (%) |

Measured (ng/mL) |

RE (%) |

RSD (%) |

||

| Oleuropein | 0.5 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | –13.3 | 11.9 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | –4.4 | 13.5 |

| 5 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | –3.0 | 5.2 | 5.1 ± 0.4 | 2.6 | 7.9 | |

| 100 | 100.8 ± 7.0 | 0.8 | 6.9 | 108.9 ± 10.1 | 8.9 | 9.3 | |

| Chlorogenic acid | 1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 13.3 | 4.6 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 12.8 | 5.9 |

| 10 | 9.0 ± 0.5 | –10.0 | 5.3 | 9.4 ± 0.6 | –6.1 | 6.0 | |

| 200 | 193.2 ± 6.5 | –3.4 | 3.4 | 209.6 ± 15.7 | 4.8 | 7.5 | |

| Formononetin | 1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 11.7 | 8.8 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 9.4 | 8.6 |

| 10 | 10.3 ± 0.3 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 10.3 ± 0.4 | 3.2 | 4.1 | |

| 200 | 224.4 ± 6.5 | 12.2 | 2.9 | 221.8 ± 11.2 | 10.9 | 5.0 | |

| Verbascoside | 2 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 1.7 | 6.0 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 2.2 | 7.4 |

| 20 | 21.2 ± 1.3 | 5.8 | 6.2 | 21.6 ± 1.4 | 8.1 | 6.6 | |

| 400 | 424.0 ± 22.5 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 419.5 ± 16.4 | 4.9 | 3.9 | |

| Linarin | 1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 3.3 | 10.0 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 6.1 | 10.3 |

| 10 | 10.2 ± 0.4 | 1.7 | 3.8 | 10.4 ± 0.3 | 3.8 | 3.2 | |

| 200 | 213.1 ± 4.1 | 6.5 | 1.9 | 217.3 ± 12.1 | 8.7 | 5.5 | |

| Luteolin | 1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 11.7 | 8.8 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 9.4 | 8.6 |

| 10 | 10.0 ± 0.3 | –0.5 | 3.0 | 10.3 ± 0.5 | 3.0 | 4.8 | |

| 200 | 221.7 ± 7.1 | 10.8 | 3.2 | 221.0 ± 8.9 | 10.5 | 4.0 | |

| Jaspolyside | 1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 5.0 | 11.7 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 2.8 | 11.0 |

| 10 | 9.7 ± 1.0 | –2.8 | 10.6 | 9.6 ± 0.8 | –4.2 | 8.6 | |

| 200 | 200.3 ± 17.6 | 0.1 | 8.8 | 209.5 ± 16.5 | 4.8 | 7.9 | |

| Specnuezhenide | 1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 6.7 | 10.2 |

| 10 | 10.3 ± 0.5 | 3.0 | 4.8 | 10.3 ± 0.5 | 3.1 | 5.2 | |

| 200 | 213.7 ± 7.6 | 6.9 | 3.6 | 215.0 ± 9.2 | 7.5 | 4.3 | |

The extraction recoveries and matrix effects of QC samples are summarized in Table 9. The extraction recoveries of the eight analytes were between 85.5% and 113.3%, with RSD values less than 12.9%. The matrix effects of these analytes were within the acceptable range of 83.2–117.5%, with RSD values less than 15.4%. These results demonstrate that the obtained extraction recoveries and matrix effects were acceptable at different concentrations.

Table 9.

Extraction recoveries and matrix effects of 8 compounds (n = 6).

| Compounds | Spiked concentration (ng/mL) |

Extraction recovery (%) |

RSD (%) |

Matrix effect (%) |

RSD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oleuropein | 0.5 | 95.8 ± 12.3 | 12.9 | 108.2 ± 13.1 | 12.1 |

| 5 | 89.5 ± 6.0 | 6.7 | 89.6 ± 5.0 | 5.6 | |

| 100 | 98.4 ± 1.8 | 1.8 | 94.5 ± 2.3 | 2.5 | |

| Chlorogenic acid | 1 | 86.7 ± 9.9 | 11.4 | 109.6 ± 9.9 | 9.0 |

| 10 | 89.6 ± 9.5 | 10.6 | 93.4 ± 5.7 | 6.1 | |

| 200 | 113.3 ± 7.9 | 7.0 | 108.5 ± 7.9 | 7.3 | |

| Formononetin | 1 | 97.2 ± 7.3 | 7.5 | 113.6 ± 4.9 | 4.3 |

| 10 | 89.6 ± 2.0 | 2.3 | 86.6 ± 2.6 | 3.1 | |

| 200 | 90.1 ± 1.3 | 1.5 | 90.1 ± 0.5 | 0.6 | |

| Verbascoside | 2 | 85.5 ± 6.2 | 7.3 | 117.5 ± 8.3 | 7.1 |

| 20 | 94.1 ± 3.0 | 3.2 | 100.2 ± 4.9 | 4.9 | |

| 400 | 102.5 ± 3.4 | 3.4 | 95.4 ± 3.5 | 3.6 | |

| Linarin | 1 | 101.8 ± 12.8 | 12.6 | 116.6 ± 11.2 | 9.6 |

| 10 | 88.0 ± 4.3 | 4.9 | 86.8 ± 3.0 | 3.5 | |

| 200 | 96.1 ± 0.5 | 0.6 | 100.2 ± 0.7 | 0.6 | |

| Luteolin | 1 | 101.5 ± 11.3 | 11.1 | 108.3 ± 7.8 | 7.2 |

| 10 | 90.8 ± 7.2 | 7.9 | 95.7 ± 2.3 | 2.4 | |

| 200 | 91.1 ± 3.4 | 3.8 | 90.7 ± 4.5 | 5.0 | |

| Jaspolyside | 1 | 101.1 ± 12.2 | 12.1 | 94.1 ± 14.5 | 15.4 |

| 10 | 97.2 ± 3.8 | 3.9 | 83.2 ± 8.5 | 10.2 | |

| 200 | 95.9 ± 1.6 | 1.6 | 91.1 ± 2.0 | 2.2 | |

| Specnuezhenide | 1 | 100.5 ± 4.6 | 4.6 | 117.0 ± 10.6 | 9.1 |

| 10 | 88.2 ± 2.8 | 3.1 | 88.1 ± 2.4 | 2.7 | |

| 200 | 95.3 ± 1.8 | 1.9 | 93.5 ± 0.8 | 0.9 |

The stability tests were carried out under three freeze-thaw cycles, at 25 °C for 4 h, in an autosampler for 12 h, and at −80 °C for 7 d. The result shown in Table 10 demonstrates that the three analytes were stable under the investigated conditions.

Table 10.

Stability of 8 compounds in rat plasma (n = 3).

| Compounds | Concentration (ng/mL) |

Room temperature (4 h, 25 °C) |

Three freeze/ thaw cycles |

Autosampler (12 h, 4 °C) |

Long term (7 day, –80 °C) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured (ng/mL) |

RSD (%) |

Measured (ng/mL) |

RSD (%) |

Measured (ng/mL) |

RSD (%) |

Measured (ng/mL) |

RSD (%) |

||

| Oleuropein | 0.5 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 10.8 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 10.8 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 13.3 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 5 | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 12.0 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | 3.0 | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 5.9 | |

| 100 | 108.6 ± 7.8 | 7.2 | 103.6 ± 9.3 | 9.0 | 93.4 ± 8.6 | 9.2 | 113.9 ± 9.9 | 8.7 | |

| Chlorogenic acid | 1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 4.9 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 5.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 6.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 5.6 |

| 10 | 9.2 ± 0.6 | 6.6 | 9.8 ± 0.8 | 7.6 | 9.1 ± 1.1 | 12.1 | 10.3 ± 0.5 | 4.8 | |

| 200 | 187.6 ± 4.2 | 2.3 | 212.6 ± 19.4 | 9.1 | 200.0 ± 14.0 | 7.0 | 214.4 ± 10.5 | 4.9 | |

| Formononetin | 1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 10.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 10.0 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 4.9 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 5.4 |

| 10 | 11.8 ± 0.2 | 1.3 | 10.1 ± 1.0 | 0.6 | 10.1 ± 0.2 | 1.5 | 10.2 ± 0.2 | 2.0 | |

| 200 | 220.6 ± 3.5 | 1.6 | 206.3 ± 21.0 | 10.2 | 222.6 ± 3.6 | 1.6 | 216.0 ± 4.3 | 2.0 | |

| Verbascoside | 2 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 2.6 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 2.8 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 8.2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 7.9 |

| 20 | 19.6 ± 1.0 | 5.3 | 21.8 ± 1.9 | 8.9 | 23.8 ± 1.8 | 7.7 | 21.3 ± 1.8 | 8.5 | |

| 400 | 427.6 ± 13.8 | 3.2 | 416.4 ± 17.6 | 4.2 | 402.4 ± 19.1 | 4.7 | 430.0 ± 6.2 | 1.4 | |

| Linarin | 1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 11.2 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 9.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 5.4 |

| 10 | 11.9 ± 0.1 | 0.8 | 11.6 ± 0.5 | 4.1 | 10.2 ± 0.6 | 5.4 | 10.2 ± 0.4 | 3.5 | |

| 200 | 223.3 ± 5.0 | 2.2 | 219.4 ± 13.8 | 6.3 | 208.5 ± 2.0 | 1.0 | 221.0 ± 11.2 | 5.1 | |

| Luteolin | 1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 4.9 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 9.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 5.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 11.2 |

| 10 | 11.3 ± 0.3 | 2.2 | 11.4 ± 0.8 | 7.3 | 10.0 ± 0.2 | 1.5 | 10.4 ± 0.6 | 6.2 | |

| 200 | 217.9 ± 11.7 | 5.4 | 218.0 ± 9.9 | 4.5 | 205.6 ± 0.9 | 0.4 | 221.9 ± 6.8 | 3.1 | |

| Jaspolyside | 1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 4.9 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 9.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 10.0 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 11.2 |

| 10 | 11.1 ± 0.8 | 7.2 | 10.4 ± 0.4 | 2.9 | 11.0 ± 0.1 | 1.1 | 10.1 ± 0.2 | 1.7 | |

| 200 | 227.5 ± 9.8 | 4.3 | 206.0 ± 15.7 | 7.6 | 210.8 ± 2.6 | 1.2 | 216.0 ± 16.1 | 7.5 | |

| Specnuezhenide | 1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 10.0 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 11.9 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 5.4 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 5.4 |

| 10 | 10.7 ± 0.2 | 1.7 | 11.5 ± 0.6 | 5.3 | 9.8 ± 0.6 | 6.2 | 10.3 ± 0.6 | 6.1 | |

| 200 | 212.7 ± 8.4 | 4.0 | 219.0 ± 8.4 | 3.8 | 198.2 ± 2.6 | 1.3 | 225.6 ± 9.0 | 4.0 | |

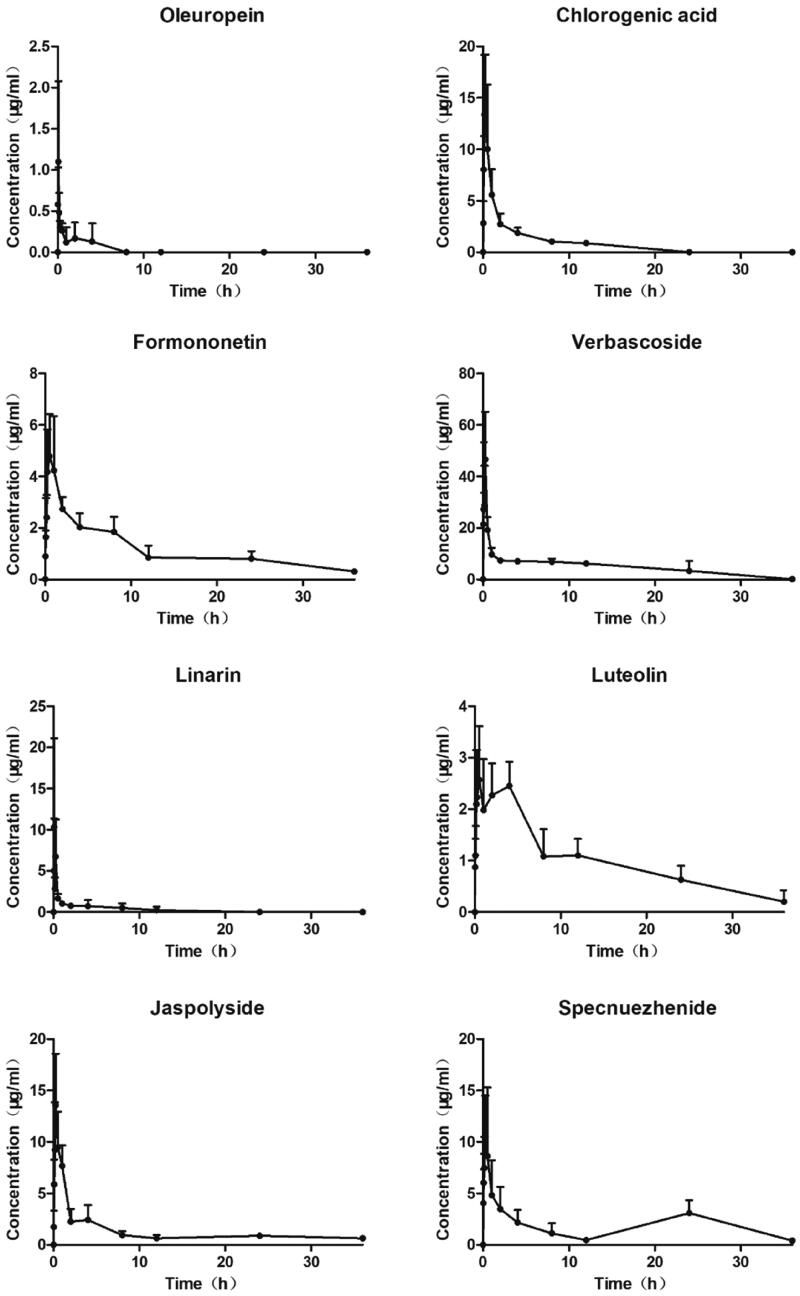

Application of the bioanalytical method

The plasma concentration-time curve after oral administration of TWMM is illustrated in Figure 9, and the determined pharmacokinetic parameters are shown in Table 11. According to DAS analysis, the Tmax values of chlorogenic acid, formononetin, verbascoside, linarin, jaspolyside, and specnuezhenide were within 1 h, which suggests that these six compounds attained maximum plasma concentration rapidly. The t1/2 values show rapid elimination of oleuropein, chlorogenic acid, verbascoside, and linarin. The areas under the concentration-time curve (AUC0–∞) of oleuropein, chlorogenic acid, formononetin, verbascoside, linarin, luteolin, jaspolyside, and specnuezhenide were 1.03 ± 0.75, 33.95 ± 4.55, 45.96 ± 7.89, 174.81 ± 40.83, 12.04 ± 4.72, 43.98 ± 4.19, 53.37 ± 32.17, and 57.19 ± 30.25 mg/mL/min, respectively.

Figure 9.

Plasma concentration–time curves of 8 compounds after oral administration of TWMM (n = 6, mean ± SD).

Table 11.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of 8 compounds after oral administration of TWMM (n = 6).

| Compounds |

Tmax (h) |

Cmax (ng/mL) |

t1/2 (h) |

AUC (0–36) (h·ng/mL) |

AUC (0–∞) (h·ng/mL) |

MRT (0–36) (h) |

MRT (0–∞) (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oleuropein | 1.37 ± 1.60 | 0.90 ± 0.82 | 3.36 ± 0.00 | 1.03 ± 0.75 | 1.03 ± 0.75 | 1.53 ± 1.25 | 1.54 ± 1.25 |

| Chlorogenic acid | 0.39 ± 0.32 | 16.13 ± 4.17 | 2.71 ± 0.11 | 33.95 ± 4.55 | 33.95 ± 4.55 | 4.97 ± 0.71 | 4.97 ± 0.71 |

| Formononetin | 0.46 ± 0.29 | 6.17 ± 1.65 | 11.70 ± 2.09 | 40.78 ± 8.51 | 45.96 ± 7.89 | 10.69 ± 1.17 | 15.73 ± 1.90 |

| Verbascoside | 0.25 ± 0.14 | 45.47 ± 21.16 | 2.08 ± 0.38 | 174.81 ± 40.83 | 174.81 ± 40.83 | 8.90 ± 3.44 | 8.91 ± 3.44 |

| Linarin | 0.16 ± 0.10 | 12.78 ± 8.82 | 2.81 ± 0.21 | 12.04 ± 4.72 | 12.04 ± 4.72 | 4.26 ± 2.67 | 4.26 ± 2.68 |

| Luteolin | 1.71 ± 1.79 | 3.27 ± 0.78 | 11.14 ± 10.20 | 38.46 ± 7.61 | 43.98 ± 4.19 | 11.36 ± 1.23 | 18.20 ± 9.14 |

| Jaspolyside | 0.38 ± 0.31 | 14.25 ± 3.67 | 29.15 ± 12.65 | 46.59 ± 9.58 | 53.37 ± 32.17 | 11.42 ± 1.29 | 15.62 ± 10.83 |

| Specnuezhenide | 0.46 ± 0.29 | 13.33 ± 4.61 | 20.27 ± 25.00 | 48.62 ± 19.41 | 57.19 ± 30.25 | 11.02 ± 5.63 | 19.29 ± 16.60 |

Validation of bioactivity

The result of network pharmacology and identification of compounds in vivo revealed the potential ingredients and targets in the DR treatment of TWMM. To verified the bioactivity, the validated promoter or inhibitor binding sites of 5 targets were selected for docking with luteolin and formononetin. Then, PyMOL was used to verify and visualize the key hydrogen bonds of docking analysis (Figure 10). The -CDOCKER interaction energy ≤ −20 and hydrogen bonds indicated the good binding activity between two compounds and receptors. Furthermore, we used an assay of intracellular ROS and a luciferase reporter assay to verify the pharmacological activity of luteolin and formononetin. The results showed that luteolin and formononetin could alleviate the symptom of DR. More detail was added in Supplementary Materials.

Figure 10.

The 3D interaction diagrams of luteolin and formononetin.

Application of network pharmacology in the pharmacokinetic study

Network pharmacology can be applied to screen compounds that have a high contribution in treating diseases, unveiling the target compounds to obtain better clinical adaptability that is similar to that of the parent herb or formulation. After systematic qualitative and network pharmacology analyses, apigenin, luteolin, daidzein, kaempferol, baicalein, rutin, chrysoeriol, glycitein, and formononetin were selected as potential target compounds based on degree and betweenness centrality. Furthermore, based on the qualitative analysis of plasma samples after oral administration of TWMM, luteolin and formononetin were found to immigrate into the blood. Therefore, luteolin and formononetin were selected as detectable in vivo markers having a high probability in the treatment of DR.

Network pharmacology can identify pharmacokinetic target compounds with high efficiency and accuracy. However, the pharmacokinetic parameters of the same compound in different herbs or prescriptions are not consistent. Wang et al. (2017) showed that the pharmacokinetic parameters of luteolin, in general, had a higher Tmax and lower t1/2 than those of the extract. In addition, luteolin has been reported to have Tmax and t1/2 values ranging between 0.50–2.83 h and 3.63–12.10 h in different herbal extracts and prescriptions, respectively (Guan et al. 2014; Cheruvu et al. 2018; Jia et al. 2020). Owing to the different Tmax and t1/2 values from the various herbs and prescriptions, the influence on target compounds is diverse. Network pharmacology is adept at analyzing compound mixtures and presenting degrees to which each compound can be selected as a target molecule for pharmacokinetic studies of any herbal mixture.

Network pharmacology can also identify pharmacokinetic target compounds in herbs or prescriptions based on their clinical application. The different pathological conditions also influence the ADME of drugs, resulting in different therapeutic outcomes. On comparing the absorption rate of formononetin and luteolin in diabetic and healthy rats, Wei et al. (2017) observed that the absorption rate in the diabetic rats was lower than in the healthy ones, and the metabolism of formononetin in the former was more rapid, whereas that of luteolin was slower (Liu et al. 2021). Furthermore, ADME of the same compounds in vivo was greatly affected by the external environment. Therefore, these results prompt us to carry out a pharmacokinetic study using a DR mouse model in the future.

Conclusions

Using network pharmacology, we focussed on the qualitative components of TWMM obtained using UPLC-MS and GC-MS to screen the key molecules that share the same targets with DR. Luteolin and formononetin were determined as the target compounds in explaining the pharmacokinetic properties of TWMM. This study provides a suitable combination strategy to unveil pharmacokinetic markers based on clinical application with high efficiency and clinical focus.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [81903915] and the National Major Scientific and Technological Special Project for “Significant New Drugs Development”, China [2019ZX09201005-002-007].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bagli E, Stefaniotou M, Morbidelli L, Ziche M, Psillas K, Murphy C, Fotsis T.. 2004. Luteolin inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenesis; inhibition of endothelial cell survival and proliferation by targeting phosphatidylinositol 3'-kinase activity. Cancer Res. 64(21):7936–7946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Lv H, Gan J, Ren J, Liu J.. 2017. Tang Wang Ming Mu granule attenuates diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetes rats. Front Physiol. 8:1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheruvu HS, Yadav NK, Valicherla GR, Arya RK, Hussain Z, Sharma C, Arya KR, Singh RK, Datta D, Gayen JR. 2018. LC-MS/MS method for the simultaneous quantification of luteolin, wedelolactone and apigenin in mice plasma using hansen solubility parameters for liquid-liquid extraction: Application to pharmacokinetics of Eclipta alba chloroform fraction. J Chromatogr B. 1081:76–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding M, Ma W, Wang X, Chen S, Zou S, Wei J, Yang Y, Li J, Yang X, Wang H, et al. . 2019. A network pharmacology integrated pharmacokinetics strategy for uncovering pharmacological mechanism of compounds absorbed into the blood of Dan-Lou tablet on coronary heart disease. J Ethnopharmacol. 242:112055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulull N, Kwa F, Osman N, Rai U, Shaikh B, Thrimawithana TR.. 2019. Recent advances in the management of diabetic retinopathy. Drug Discov Today. 24(8):1499–1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fajnkuchen F, Delyfer MN, Conrath J, Baillif S, Mrejen S, Srour M, Bellamy JP, Dupas B, Lecleire-Collet A, Meillon C, et al. . 2020. Expectations and fears of patients with diabetes and macular edema treated by intravitreal injections. Acta Diabetol. 57(9):1081–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan H, Qian D, Ren H, Zhang W, Nie H, Shang E, Duan J.. 2014. Interactions of pharmacokinetic profile of different parts from Ginkgo biloba extract in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 155(1):758–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SH, Kim HY, Quispe YNG, Wang Z, Zuo G, Lim SS.. 2019. Aldose reductase, protein glycation inhibitory and antioxidant of Peruvian medicinal plants: the case of Tanacetum parthenium L. and its constituents. Molecules. 24(10):2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Q, Huang X, Yao G, Ma W, Shen J, Chang Y, Ouyang H, He J.. 2020. Pharmacokinetic study of thirteen ingredients after the oral administration of Flos Chrysanthemi extract in rats by UPLC-MS/MS. Biomed Res Int. 2020:8420409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Liang G, Ren Y, Xu T, Song Y, Jin W.. 2020. An UPLC-MS/MS method for simultaneous quantification of the components of Shenyanyihao oral solution in rat plasma. Biomed Res Int. 2020:4769267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li FS, Weng JK.. 2017. Demystifying traditional herbal medicine with modern approaches. Nat Plants. 3:17109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Bukhari SNA, Khan T, Chitti R, Bevoor DB, Hiremath AR, SreeHarsha N, Singh Y, Gubbiyappa KS.. 2020. Apigenin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticle attenuates diabetic nephropathy induced by streptozotocin nicotinamide through Nrf2/HO-1/NF-κB signalling pathway. Int J Nanomedicine. 15:9115–9124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Liu HL, Qiu F, Yang XW, Zhao HY, Bian BL, Wang L.. 2019. Pharmacokinetics of the Yougui pill in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis model rats and its pharmacological activity in vitro. DDDT. 13:2357–2370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Chen X, Ge Y, Wang H, Phosat C, Li J, Mao HP, Gao XM, Chang YX.. 2020. Network pharmacology strategy for revealing the pharmacological mechanism of pharmacokinetic target components of San-Ye-Tang-Zhi-Qing formula for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Ethnopharmacol. 260:113044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Wang W, Chen Y, Yan H, Wu D, Xu J, Shi S, Shen X, Huang X.. 2020. Simultaneous quantification of nine components in the plasma of depressed rats after oral administration of Chaihu-Shugan-San by ultra-performance liquid chromatography/quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometry and its application to pharmacokinetic studies. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 186:113310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Wu X, Si Z, Kong D, Yang D, Zhou F, Wang Z.. 2021. Simultaneous determination of nine constituents by validated UFLC-MS/MS in the plasma of cough variant asthma rats and its application to pharmacokinetic study after oral administration of Huanglong cough oral liquid. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 193:113726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W, Chen X, Ye L, Chen X, Jia W, Zhao Y, Samorodov AV, Zhang Y, Hu X, Zhuang F, et al. . 2021. Kaempferol attenuates streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy by downregulating TRAF6 expression: the role of TRAF6 in diabetic nephropathy. J Ethnopharmacol. 268:113553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mones J, Srivastava SK, Jaffe GJ, Tadayoni R, Albini TA, Kaiser PK, Holz FG, Korobelnik JF, Kim IK, Pruente C, et al. . 2021. Risk of inflammation, retinal vasculitis, and retinal occlusion-related events with brolucizumab: post hoc review of HAWK and HARRIER Ophthalmology. 128(7):1050–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz IM, Rezzola S, Cancarini A, Russo A, Costagliola C, Semeraro F, Presta M.. 2019. Human vitreous in proliferative diabetic retinopathy: characterization and translational implications. Prog Retin Eye Res. 72:100756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oza MJ, Kulkarni YA.. 2019. Formononetin attenuates kidney damage in type 2 diabetic rats. Life Sci. 219:109–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan B, Fang S, Zhang J, Pan Y, Liu H, Wang Y, Li M, Liu L.. 2020. Chinese herbal compounds against SARS-CoV-2: puerarin and quercetin impair the binding of viral S-protein to ACE2 receptor. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 18:3518–3527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabanayagam C, Banu R, Chee ML, Lee R, Wang YX, Tan G, Jonas JB, Lamoureux EL, Cheng CY, Klein BEK, et al. . 2019. Incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy: a systematic review. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 7(2):140–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalchi Z, Mahroo O, Bunce C, Mitry D.. 2020. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for macular oedema secondary to branch retinal vein occlusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 7:CD009510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song CY, Chen MX, Guo P, Liu GR, Liu Y, Lian ZL.. 2015. Preventive and therapeutic effects and mechanism of Tangwang Mingmu granule on rats with diabetic retinopathy. Chinese J Info TCM. 22:62–66. Chinese [Google Scholar]

- Song CY, Chen MX, Ma WB, Guo P, Liu Y, Lian ZL.. 2015. Effects of different extracts of Tangwang Mingmu granule on hypoxia-induced gene expressions in vascular endothelial cells. Chinese J Info TCM. 22:45–49. Chinese [Google Scholar]

- Stitt AW, Curtis TM, Chen M, Medina RJ, McKay GJ, Jenkins A, Gardiner TA, Lyons TJ, Hammes HP, Simo R, et al. . 2016. The progress in understanding and treatment of diabetic retinopathy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 51:156–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Xiao J, Hou H, Li P, Yuan Z, Xu H, Liu R, Li Q, Bi K.. 2017. Development of an ultra-fast liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method for simultaneous determination of seven flavonoids in rat plasma: application to a comparative pharmacokinetic investigation of Ginkgo biloba extract and single pure ginkgo flavonoids after oral administration. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 1060:173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei BB, Chen ZX, Liu MY, Wei MJ.. 2017. Development of a UPLC-MS/MS method for simultaneous determination of six flavonoids in rat plasma after administration of maydis stigma extract and its application to a comparative pharmacokinetic study in normal and diabetic rats. Molecules. 22:1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead M, Wickremasinghe S, Osborne A, Van Wijngaarden P, Martin KR.. 2018. Diabetic retinopathy: a complex pathophysiology requiring novel therapeutic strategies. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 18(12):1257–1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Froio RM, Sciuto TE, Dvorak AM, Alon R, Luscinskas FW.. 2005. ICAM-1 regulates neutrophil adhesion and transcellular migration of TNF-alpha-activated vascular endothelium under flow. Blood. 106(2):584–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Wang YF, Byrne R, Schneider G, Yang SY.. 2019. Concepts of artificial intelligence for computer-assisted drug discovery. Chem Rev. 119(18):10520–10594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan TT, Xu HT, Zhao L, Lv L, He YJ, Zhang ND, Qin LP, Han T, Zhang QY.. 2015. Pharmacokinetic and tissue distribution profile of curculigoside after oral and intravenously injection administration in rats by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Fitoterapia. 101:64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang FX, Li ZT, Yang X, Xie ZN, Chen MH, Yao ZH, Chen JX, Yao XS, Dai Y.. 2021. Discovery of anti-flu substances and mechanism of Shuang-Huang-Lian water extract based on serum pharmaco-chemistry and network pharmacology. J Ethnopharmacol. 268:113660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Liu J, Li R, Zhao R, Zhang M, Wei S, Ran D, Jin W, Wu C.. 2020. A network pharmacology approach to investigate the anticancer mechanism and potential active ingredients of Rheum palmatum L. against lung cancer via induction of apoptosis. Front Pharmacol. 11:528308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Zhang T, Lu B, Yu Z, Mei X, Abulizi P, Ji L.. 2016. Lonicerae Japonicae Flos attenuates diabetic retinopathy by inhibiting retinal angiogenesis. J Ethnopharmacol. 189:117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.