Dear Sir,

The use of WALANT (wide awake local anaesthesia no tourniquet) has gained recent popularity, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, for upper and lower limb surgery.1 It avoids the need for an anaesthetist, reducing costs and issues with tourniquet pain.2 However, WALANT is not entirely free of problems. Injecting local anaesthetic directly into and around the site of surgery causes local swelling and distorts tissue planes. Although adrenaline produces a relatively bloodless field, excessive post-op bleeding can be a problem once the adrenaline wears off and any fibrin deposition related to this may result in increased stiffness in both the short and long term.3

The predecessor to WALANT was the regional block and knowing how to administer one was always considered part of a hand surgeons’ armamentarium. However, in the UK today, ‘blocks’ are usually administered by an anaesthetist, under ultrasound guidance.4 This was not always the case, and the senior author remembers a time when surgeons would routinely administer regional blocks themselves, safely, quickly and often more effectively than those now administered by anaesthetists.

We have speculated on the reasons for the greater speed and efficacy of surgeon-administered blocks in our unit compared with those administered by our anaesthetic colleagues. We wonder whether this is related to a better appreciation of the anatomy of the brachial plexus and/or sciatic nerves derived from direct experience of seeing these structures during surgery. Alternatively, it might be the result of our reliance on nerve stimulators (rather than ultrasound), and the positive feedback that is obtained from using this device during the block procedure.

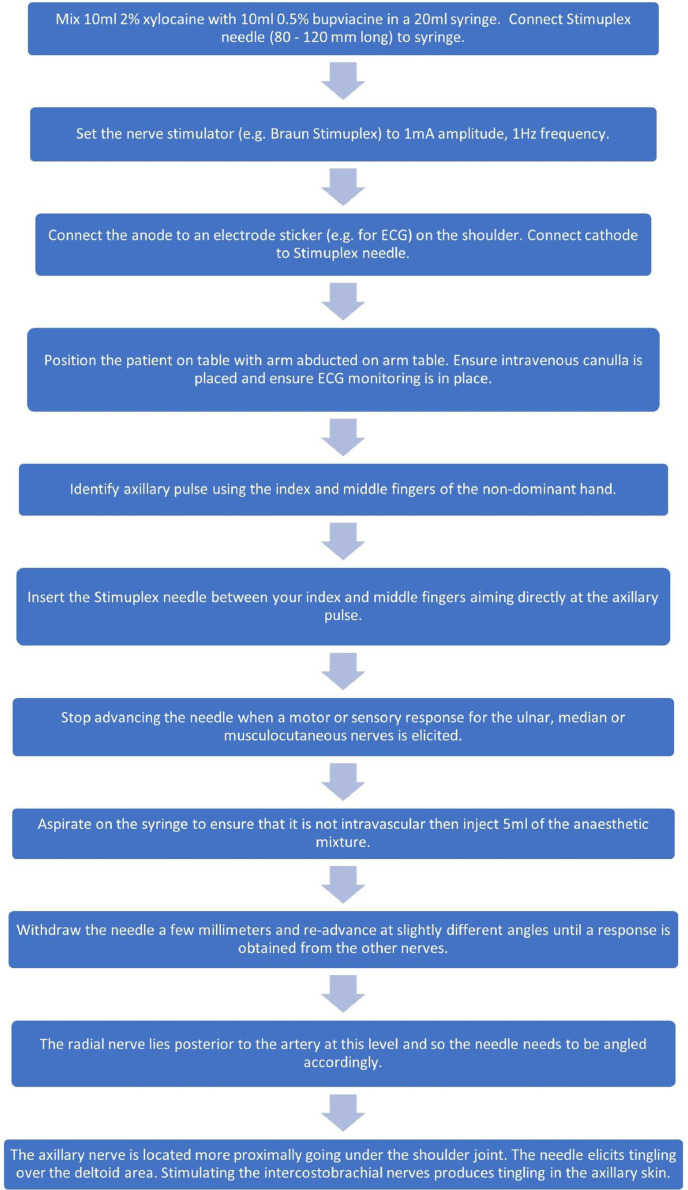

Using a nerve stimulator, the patient confirms whether the intended nerve territory has been blocked (Table 1 ) which enhances the efficacy of the procedure. Moreover, injection of local anaesthetic immediately adjacent to the specific nerves ensures that anaesthesia is induced very quickly (typically within a few seconds), avoiding the need to wait for the block to ‘cook’. Equally, there is no need to wait 30 minutes for the vasoconstrictive effect of the adrenaline with WALANT because a tourniquet can be used.5 Using our block technique (Figure 1 ), tourniquet pain is not an issue because we are able to block both the axillary (deltoid area) and intercostobrachial nerves (inner arm). Therefore, the area to be treated can be prepped and surgery can begin almost immediately after administration of the regional block, resulting in further time-saving.

Table 1.

Anatomical landmarks, motor (muscle contraction) and sensory (paraesthesia) responses when administering regional blocks using a nerve stimulator.

| Landmark | Motor response | Sensory response | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ulnar nerve | Anterior (inferior) to axillary artery | Finger flexion | Little and ring fingers, medial forearm/ arm |

| Median nerve | Anterior (middle) to axillary artery | Wrist flexion | Thumb, index and middle fingers |

| Musculocutaneous nerve | Anterior (superior) to axillary artery | Elbow flexion | Lateral forearm |

| Radial nerve | Posterior (distal) to axillary artery | Wrist and elbow extension | Dorsum of hand, forearm and arm |

| Axillary nerve | Posterior (proximal) to axillary artery | Deltoid contraction | Lateral arm |

| Sciatic nerve | Midline posterior thigh | Plantar flexion | Posterior lower leg |

Figure 1.

Guide to safe administration of an infraclavicular axillary block using a nerve stimulator.

WALANT and regional blocks both have definite roles in extremity surgery. Gauging the correct tension of a tendon transfer is definitely easier to do under WALANT. However, for most of the other procedures we do, the blocks we administer are quick, effective and often less painful than the alternatives. We would do well to remember how to do them.

Ethical approval

N/A.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Funding

None.

References

- 1.Hobday D., Welman T., O'Neill N., Pahal G.S. A protocol for wide awake local anaesthetic no tourniquet (WALANT) hand surgery in the context of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Surgeon. 2020;18(6):e67–e71. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2020.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lalonde D.H. Latest advances in wide awake hand surgery. Global advances in wide awake hand surgery, an issue of hand clinics, E-Book, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Kulkarni M., Harris S.B., Elliot D. The significance of extensor tendon tethering and dorsal joint capsule tightening after injury to the hand. J Hand Surg Eur. 2006;31(1):52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marhofer P., Harrop-Griffiths W., Kettner S.C., Kirchmair L. Fifteen years of ultrasound guidance in regional anaesthesia: part 1. Br J Anaesth. 2010;104(5):538–546. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lalonde D., Bell M., Benoit P., Sparkes G., Denkler K., Chang P. A multicenter prospective study of 3,110 consecutive cases of elective epinephrine use in the fingers and hand: the Dalhousie Project clinical phase. J Hand Surg Am. 2005;30(5):1061–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]