Abstract

Regulatory compliance is challenging for multinational clinical trials. Conflicts between country requirements impedes research and slows the approval of medicines, leading the pharmaceutical industry to devote significant resources to this area. Many academic centers and nonprofits cannot support industry-level investment and are vulnerable to noncompliance. To address an insufficiency in public access to this information, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases developed ClinRegs—a public access database of clinical research regulations. This report describes ClinRegs’ features, maintenance, and usage. From September 2019 through August 2020, ClinRegs had 68 504 users, 60% from outside the United States, demonstrating the demand for accessible, reliable, country-specific regulatory information. Tools such as ClinRegs can help increase regulatory compliance and free up resources for research. We encourage our partner agencies and biomedical research industries to promote greater regulatory knowledge sharing and harmonization for the betterment of clinical research and improved public health.

Keywords: clinical research regulations, clinical trial ethics, global clinical trials, public access, clinical research quality

Increasingly, regulations hinder research, raise costs, and slow the availability of medicines. The ClinRegs database provides free access to trustworthy information on country regulatory and ethics requirements. ClinRegs usage reflects the global demand for this vital information.

Among the myriad complexities in conducting safe and ethical global human research, one of the most challenging is compliance with a multitude of national and international regulations, requirements, and standards. Since the 1960s, there has been a continuous expansion of pharmaceutical and academic clinical research; in the past 20 years alone (2000–2019), there has been a more than 10-fold increase in worldwide clinical trials [1]. Furthermore, international and country-specific requirements and regulations for research, review, and licensure of new medicines continue to evolve. While many of these changes have strengthened protections for study participants and elevated research quality, they also have frequently created conflicts with existing regulations and resulted in increased bureaucracy, which has often impeded research, driven up trial costs, and slowed the availability of vital medicines in countries where they are most needed [2–5]. Recognizing these challenges, in 1990, the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) was formed to promote greater technical and regulatory conformity for clinical research, through the development of guidelines and requirements for pharmaceutical product registration. The ICH has achieved meaningful outcomes and is vitally important to continue, yet most countries and other authorities (eg, political, continental unions, intergovernmental organizations) still have unique requirements and standards that researchers and sponsors must address. Additionally, changing science and technology (as well as legal, ethical, cultural, and political considerations) drive continuous regulatory revision. As such, maintaining up-to-date awareness and understanding of applicable regulations and guidance demands constant surveillance of multiple regulatory sources, and expertise on the part of sponsors and investigators. Because compliance failures can delay or stop trials, the pharmaceutical industry devotes significant resources, sometimes as much as 15% of operational staff, to this area [6–10]. In contrast, except for the largest academic medical research centers and nonprofits, most cannot support industry-level investment and are therefore vulnerable to noncompliance.

To save funded research projects time and resources and help facilitate regulatory compliance, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) developed ClinRegs, a centralized and publicly accessible database of clinical research regulatory and ethics requirements for a set of NIAID priority countries. This report addresses what is included in ClinRegs, how the information is kept up to date, its value to users, and implications for global clinical research.

The objectives of ClinRegs are as follows:

To increase awareness and understanding of clinical research regulatory and ethics requirements for a set of NIAID priority countries

To provide a trustworthy, “one stop,” easy to use, secure, public access resource

To establish broad-based sustained usage, saving users time and resources

To maintain the site efficiently and sustainably

PURPOSE OF ClinRegs

ClinRegs exists to provide an easily accessible, reliable information source for regulatory and ethics requirements. The database currently covers 21 NIAID priority countries.

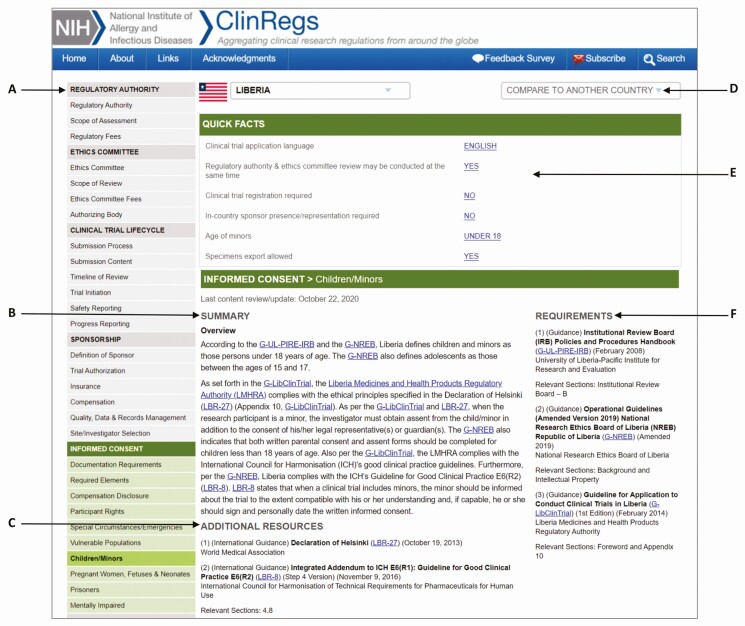

As shown in Figure 1, each country page has the following features:

Figure 1.

ClinRegs country page. A screenshot of a representative country page from ClinRegs showing the following: A, Topic areas navigable via sidebar table of contents (37 total); B, Narrative summary of requirements for each topic; C, Additional Resources listing displaying names, dates, and links to supplementary information relevant to the topic; D, Option to compare to another country in the ClinRegs database; E, Quick Facts with links to requirements details; F, Requirements listing displaying names, dates, and links to regulatory sources.

Thirty-seven topic areas easily navigable by a sidebar table of contents

Requirements listing of names, dates, and links to regulatory sources

Narrative summary of requirements for each topic

Additional resources with supplementary information relevant to a topic

Option to compare with another country in the ClinRegs database

Quick Facts with links to requirements details

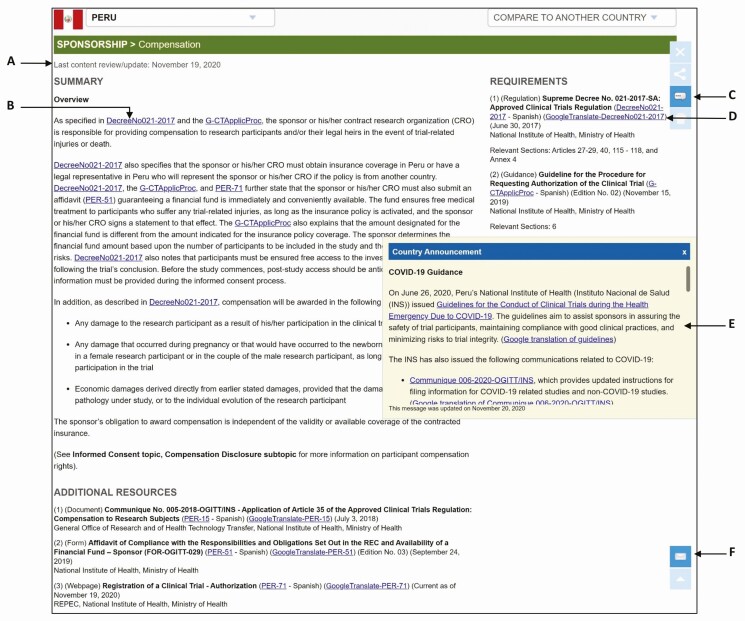

Each ClinRegs country page also has the following features to support user trust in the reliability of ClinRegs information (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Close-up of ClinRegs country page. A, Date of last content review/update for each topic; B, Source attribution with direct links in the summary content; C, User comment on topic content directly from country page/topic; D, Links to Google translation of non-English documents; E, On-page notification of recent regulatory changes; F, Self-subscription for country update notifications by e-mail.

Date of last content review/update for each topic

Source attribution with direct links to sources

Ability for users to comment on topic content directly from country page/topic

Links to Google translation of non-English documents

On-page notification of recent regulatory changes

Self-subscription for country update notifications by e-mail

KEEPING ClinRegs UP TO DATE

The trustworthiness of ClinRegs hinges on the accuracy and timely upkeep of its content. As such, the highest priority (and resource allocation) is devoted to keeping ClinRegs up to date. All country profiles are reviewed and updated thoroughly at least once yearly (at the very minimum), but interim updates are made frequently in response to substantive new or changed requirements. Automated weekly webpage scraping of regulatory sources alerts us to changes to country regulations, allowing us to assess the nature and extent of changes and make updates if warranted. ClinRegs also uses an automated monthly link scanner to check the more than 1700 hyperlinks on the site and identify those in need of correction. As examples, between September 2019 and August 2020, we did a complete review and update of each of the 21 countries in the database; we also made 15 interim updates, and replaced 375 unique links, together ensuring the accuracy and functionality of ClinRegs.

ClinRegs VALUE TO USERS

To gauge the level of interest in ClinRegs and how it may be useful to clinical researchers, the ClinRegs team tracks and analyzes a number of website analytics, among them, numbers of visits to the site and the content (countries, topics) viewed.

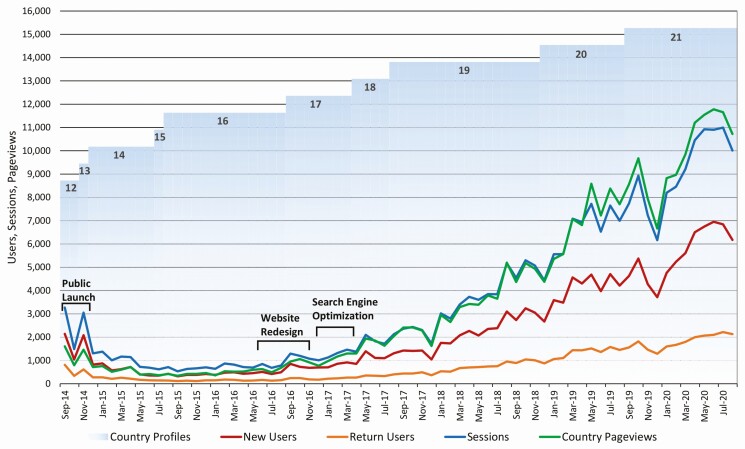

ClinRegs Usage Over Time

As shown in Figure 3, an initial surge in viewership (when ClinRegs first went public, September 2014) gave way to a reduced, but steady approximately 500–1000 user sessions per month for the following 2 years. In September 2016, ClinRegs underwent a substantial redesign to optimize the user experience and a search engine optimization effort. Shortly thereafter, usage (as measured by both new and return users) began growing steadily, doubling each year from September 2016 through August 2019. The numbers of user sessions and country page views also doubled during this period. For the most recent complete year (September 2019 through August 2020), a monthly average of 6363 users generated a mean 9783 monthly country page views, with both users and page views rising by approximately 50% over the previous year. Although continuing to grow, this smaller rise may point to a tapering of the growth rate going forward.

Figure 3.

ClinRegs monthly usage. New users (red), return users (orange), user sessions (blue), country pageviews (green). Number of country profiles available in ClinRegs (columnar numbers) and website initiatives (black brackets), September 2014 through August 2020.

ClinRegs User Countries

Analytics indicate that ClinRegs has a global reach with users from 173 countries on 6 continents, attesting to the broad-based usage of ClinRegs. While the largest share of traffic on the site comes from the United States, 60% of users come from other countries, with India greatest among them. (A global map of ClinRegs user locations is provided in Supplementary Figure 1.)

Most Frequently Viewed Countries

The top 10 countries viewed, in rank order, are as follows: United States, China, Canada, India, United Kingdom, Brazil, Australia, South Africa, Mexico, and Thailand. Together, these were viewed a total of 132 799 times from September 2019 through August 2020, accounting for 87% of total country views (Supplementary Table 1).

The vast majority of US views (87%) occur in comparisons with other countries (vs when the United States is viewed singly). The same is true, albeit to a lesser extent, for Canada (60%) and the United Kingdom (62%), likely relating to the prevalence of these countries as sponsors of global clinical research. Usage of the country comparison function has grown steadily from 12% (2015–2016) to 30% of country views in 2019–2020.

Most Frequently Viewed Topics

ClinRegs top 10 most-viewed topics in (in rank order starting with the most viewed) are as follows: Regulatory Authority, Scope of Assessment, Ethics Committee, Regulatory Fees, Submission Process, Submission Content, Ethics Committee Scope of Review, Ethics Committee Authorizing Body, Timeline of Review, and Trial Initiation (Supplementary Table 2).

The rank order of topic viewing closely matches the topics’ ordinal listing in the table of contents (Figure 1). While this could reflect a simple order effect, the topics selected and the order in which they appear were informed by user input. As such, their frequent selection likely also reflects users’ informational interests.

ClinRegs User Feedback

Although less than 1% of ClinRegs users provide feedback through the user experience survey, 90% of them consider the site a reliable source of information they would recommend to colleagues, an indicator of trust. Over 80% of respondents indicate that they believe the site helps ensure quality and safety in clinical trials, has saved them time, or that they found the information they were seeking. For respondents who did not find what they were looking for, the reason most often cited was that the specific country or topic of interest was not included in ClinRegs (Supplementary Table 3).

Discussion

NIAID’s ClinRegs website was developed to provide a trustworthy source of international clinical research regulatory information to promote efficiency, safety, and quality of NIAID global clinical research. By providing free public access and a user interface tailored to the information needs of clinical researchers, ClinRegs’ goal is to make it easy to obtain the information needed to understand country requirements, inform feasibility and implementation planning, and help ensure compliance.

ClinRegs was designed to support the full range of NIAID clinical research; as such, its content is “disease agnostic,” and not specifically targeted towards infectious disease research. That said, there can hardly be better examples of the need for a resource like ClinRegs than in considering the challenges of both recent and longstanding global infectious disease threats (eg, coronavirus disease 2019 [COVID-19], severe acute respiratory syndrome [SARS] 2002–2004, Ebola, Nipa, Middle East respiratory syndrome [MERS], Zika, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], tuberculosis, malaria, polio, influenza, plague, etc). Time and again NIAID investigators are called upon to collaborate to conduct clinical research during these epidemics, often in countries that are evolving not just their clinical research capacity but also their regulatory and ethical frameworks. In such settings, health and regulatory agencies may have limited availability, resources, or authority to develop or share regulations, policies, or procedures for clinical research that must be undertaken expeditiously. Language and cultural barriers can also impede access to and understanding of country requirements. And, because regulatory information is often obtained on an individual study basis (ie, rarely shared beyond a single study team), the effort can get repeated many times over with costly and time-consuming inefficiency, not to mention the likelihood of inconsistent understandings.

Because ClinRegs was developed principally to support NIAID research, its design and content prioritizes the information needs of its investigator community and may not serve all users. Selection of countries for inclusion is driven by NIAID’s research priorities. The 37 topics chosen for inclusion lean heavily towards safety and ethics (vs requirements for product approval), consistent with the needs of NIAID researchers who largely come from government, academic, and not-for-profit institutions. These, and other limitations, such as ClinRegs’ ostensible emphasis on therapeutics (vs biologics, diagnostics, devices), derive less from indifference to other topics than from the determination not to stretch beyond our ability to consistently provide highly detailed, well-documented, and up-to-date information on select countries and topics linked closely to NIAID research.

It has been challenging to assess ClinRegs’ trustworthiness and contributions to research quality and efficiency. Site analytics indicate that ClinRegs has a broad international user base, which continues to attract new users while retaining a substantial proportion of return users. Although it seems reasonable to infer from those measures that the site is useful and reliable, direct evidence of this is limited by the small number of responses to the voluntary user experience survey. Efforts are underway to implement simpler, less burdensome approaches to obtaining user feedback that can inform and guide ClinRegs continued evolution, which could possibly include greater emphasis on particular areas/types of clinical research, in alignment with NIAID research priorities.

Looking forward, ClinRegs may be helpful in revealing country differences that might be amenable to harmonization, especially in the context of regional clinical research collaborations. Additionally, as novel areas of medical research evolve, so will regulation and ethical oversight. Keeping ClinRegs useful will likely require modifications to both scope and content. And although ClinRegs will retain its NIAID focus, NIAID remains committed to helping the larger investigator community stay up to date with clinical research regulations. In this regard, the ClinRegs team aims to encourage regulatory authorities to make better use of electronic media to rapidly share their updates and to consider modifications to their websites (eg, greater conformity of topic naming and information organization, more explanatory narrative summaries) that could make regulations easier to find and understand. NIAID also hopes to encourage our biomedical research partners in the pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and diagnostics industries; contract research organizations; and other sector entities to be more forthcoming in sharing their extensive knowledge of international clinical research regulation with the investigator community, for the betterment and efficiency of clinical research overall, and ultimately, improved global health.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors gratefully acknowledge the individuals and organizations that have provided and continue to provide country-specific regulatory information and/or confirmations of accuracy for the country content provided in ClinRegs.

Disclaimer. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US government.

Financial support. This work was supported by the US government with funds from the National Institutes of Health, under contract number 75N91019D00024, Task Order TO04 (subcontract to General Dynamics Information Technology, from the Clinical Monitoring Research Program Directorate, Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, Frederick, MD, USA).

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.National Institutes of Health. Trends, charts, and maps. Available at: clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/resources/trends#RegisteredStudiesOverTime. Accessed 12 March 2020.

- 2.Duley L, Antman K, Arena J, et al. . Specific barriers to the conduct of randomized trials. Clin Trials 2008; 5:40–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Califf RM. Clinical trials bureaucracy: unintended consequences of well-intentioned policy. Clin Trials 2006; 3:496–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neaton JD, Babiker A, Bohnhorst M, et al. . Regulatory impediments jeopardizing the conduct of clinical trials in Europe funded by the National Institutes of Health. Clin Trials 2010; 7:705–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Shahi Salman R, Beller E, Kagan J, et al. . Increasing value and reducing waste in biomedical research regulation and management. Lancet 2014; 383: 176– 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Getz K. Characterizing the real cost of site regulatory compliance. Appl Clin Trials 2015; 6:18– 20. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenberg R. Regulatory compliance an increasing burden on sites. The CenterWatch Monthly 2015; 22:04. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quality Metrics for Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Excellence. Business wire 2003. Available at: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20031113005021/en/Quality-Metrics-Pharmaceutical-Manufacturing-Excellence. Accessed 12 March 2020.

- 9.Arling ER, Dillon R, Noferi J. Creating effective biopharmaceutical QA/QC organizations. BioPharm 2002; 24:40– 6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haleem R, Salem M, Fatahallah FA, et al. . Quality in the pharmaceutical industry—a literature review. Saudi Pharm J 2015; 23:463– 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.