Abstract

Background

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is a neglected tropical disease causing an estimated 1 million new cases annually. While antimonial compounds are the standard of care worldwide, they are associated with significant adverse effects. Miltefosine, an oral medication, is United States (US) Food and Drug Administration approved to treat CL caused by Leishmania braziliensis, Leishmania guyanensis, and Leishmania panamensis. Evidence of efficacy in other species and side-effect profiles in CL has been limited.

Methods

Twenty-six patients with CL were treated with miltefosine at the US National Institutes of Health. Species included L. braziliensis (n = 7), L. panamensis (n = 5), Leishmania mexicana (n = 1), Leishmania infantum (n = 3), Leishmania aethiopica (n = 4), Leishmania tropica (n = 2), Leishmania major (n = 1), and unspeciated (n = 3). Demographic and clinic characteristics of the participants, response to treatment, and associated adverse events were analyzed.

Results

Treatment with miltefosine resulted in cure in 77 % (20/26) of cases, with cures among all species. Common adverse events included nausea/vomiting (97%) and lack of appetite (54%). Clinical management or dose reduction was required in a third of cases. Gout occurred in 3 individuals with a prior history of gout. Most laboratory abnormalities, including elevated creatinine and aminotransferases, were mild and normalized after treatment.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that miltefosine has good but imperfect efficacy to a wide variety of Leishmania species. While side effects were common and mostly mild to moderate, some resulted in discontinuation of therapy. Due to oral administration, broad efficacy, and manageable toxicities, miltefosine is a viable alternative treatment option for CL, though cost and lack of local availability may limit its widespread use.

Keywords: cutaneous leishmaniasis, miltefosine, treatment, efficacy, adverse events

Miltefosine is an oral therapy for cutaneous leishmaniasis with advantages of ease of administration and efficacy for most species based on limited studies. Mild-to-moderate adverse events were common and reversible but led to early discontinuation in some patients.

Leishmaniasis is a neglected tropical disease affecting millions worldwide. Leishmaniasis includes 3 main forms of disease—cutaneous (CL), mucocutaneous (MCL), and visceral (VL)—with the most common form, CL, estimated to cause approximately 1 million new cases annually worldwide [1]. More than 20 species causing infection worldwide are classified as Old World (species found in the Mediterranean, Middle East, Asia, and Africa, including Leishmania tropica, Leishmania major, Leishmania infantum, and Leishmania aethiopica) and New World (species found in Mexico, Central America, and South America, including Leishmania braziliensis, Leishmania guyanensis, Leishmania panamensis, Leishmania amazonensis, and Leishmania mexicana). The disease is acquired in endemic areas by both residents and travelers [2]. The infection manifests most often as painless ulcers found primarily on exposed parts of the body, such as the face or the extremities. The clinical course varies and ranges from self-limited infection to chronic, long-standing ulcers and, in some species, particularly L. braziliensis and L. aethiopica, involvement of the mucosal tissues (mouth, nose, and upper air passages) resulting in destruction of the tissues of the upper airway, scarring, and disfigurement. Treatment of CL is used to promote faster healing and to possibly prevent development of mucosal disease [3].

Miltefosine is an oral agent approved by the United States (US) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of CL due to L. braziliensis, L. guyanensis, and L. panamensis; for mucocutaneous disease due to L. braziliensis; and for VL in adults and adolescents ≥12 years of age weighing ≥30 kg. The mechanism of action of miltefosine, which was initially developed as an anticancer agent, is unknown, but thought to interfere with the leishmanial membrane lipids and mitochondrial function [4, 5]. There is known variability in efficacy to the same species from different geographic regions for most drugs used to treat CL, and evidence of efficacy of miltefosine to many Leishmania species is limited.

Worldwide, the pentavalent antimonials sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam) and meglumine antimoniate are the standard of care for the treatment of CL based on low cost and availability, but these are often poorly tolerated because of common and sometimes severe adverse effects, development of drug resistance, and parenteral administration [3]. Other treatment options include liposomal amphotericin B (L-AmB), pentamidine, paromomycin (parenteral or topical), local therapies (including thermotherapy, cryotherapy, and topical agents), and oral therapies including azoles (ketoconazole, fluconazole, and itraconazole). Topical imiquimod cream, an immune response modulator, has been used in combination with other therapies including parenteral antimony, which may lead to more rapid healing of lesions and less scarring [6].

Here we document the efficacy and safety of miltefosine in CL caused by a variety of Leishmania species from different geographic regions.

METHODS

Case Definition

The study population included all cases of confirmed CL treated with miltefosine between 2007 and 2019 at the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Intramural Program, Laboratory of Parasitic Diseases (Bethesda, Maryland), on a natural history protocol for the diagnosis and treatment of leishmanial infections (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00344188) approved by the NIAID Institutional Review Board. Since the inception of the protocol in 2001, >100 participants have been evaluated, nearly all of whom had CL. Every patient had proven leishmaniasis by characteristic histopathology and any of the following: pan-leishmanial quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detection followed by subsequent sequencing of PCR products and/or culture followed by isoenzyme classification or DNA sequencing. All patients also had a clinical presentation and epidemiological exposure consistent with the disease. Participants with VL were excluded, as were pregnant or breastfeeding women for whom miltefosine is contraindicated due to preclinical animal studies showing potential teratogenicity [4]. Participants of reproductive potential were advised to use contraception during treatment and for at least 5 months after therapy [5]. Choice of drug treatment was determined by clinical providers based on treatment guidelines, known efficacy in particular species, clinical criteria including participant medical history and comorbidities, past treatment, availability of therapeutic options, and participant preference. Treatment failures were reevaluated and retreated with alternative therapies.

Outcome Definitions

Efficacy (cure) was defined as complete epithelialization of lesion(s) after treatment assessed at 3, 6, and 12 months posttreatment. Standard treatment is a 28-day course of miltefosine, with weight-based dosing based on FDA dosing guidelines of 50 mg twice daily (30–44 kg) or 50 mg 3 times daily for ≥45 kg [5], with some early patients in this cohort treated with 50 mg twice daily prior to FDA approval of miltefosine in 2014. Lack of efficacy was defined as treatment failure (lack of epithelization of the entire lesion after a standard course of treatment at 2–3 months posttreatment), relapse after treatment, and early discontinuation (completing <2 weeks of miltefosine) for which an alternative therapy was given. Tolerability assessment included type, frequency, and severity of adverse events (AEs) occurring while on treatment, and ability to complete a standard 28-day course of treatment. Severity of AEs was classified based on Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events grading scales [7] as mild (grade 1, self-limited, requiring no clinical intervention), moderate (grade 2, requiring limited clinical management), or severe (grade 3, leading to discontinuation of treatment).

Data Abstraction

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants included age; sex; weight; geographic exposures; clinical descriptions of skin lesions including number, location and character of lesions; previous treatment for CL; and medical history, including results of skin biopsies with histologic evaluation and PCR for species identification, most done at either the NIH or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Clinical evaluations, including history and physical examinations, safety laboratory testing, clinical photography of lesions, and AEs occurring during treatment with miltefosine, were analyzed. Laboratory testing done at baseline, weekly during treatment, and at posttreatment evaluations included complete blood count with differential and comprehensive metabolic panel including renal and liver function tests, with routine monitoring of lipase, amylase, and uric acid implemented in 2016.

RESULTS

Study Participants

Twenty-six participants with confirmed CL met inclusion criteria and were treated with miltefosine. The subjects ranged in age from 8 to 84 years (median, 43.5 years); 54% (14/26) were females. In all but 3 cases (88.5%), the Leishmania species could be defined; these included L. braziliensis (n = 7), L. panamensis (n = 5), L. mexicana (n = 1), L. infantum (n = 3), L. aethiopica (n = 4), L. tropica (n = 2), and L. major (n = 1). The majority of the participants (81%) were US-based travelers who acquired infections during travel for tourism, work, voluntary service (ie, Peace Corps volunteers), visiting friends and family in endemic areas, or expatriate residency. The remainder were immigrants from endemic areas. Forty percent (10/26) of participants had been treated unsuccessfully with other therapies prior to treatment with miltefosine, including 6 (25%) who received treatment at outside institutions prior to referral and 4 (15%) who had treatment failures with other medications at NIH prior to treatment with miltefosine. Clinical presentations were varied, including single and multiple lesions, types of lesions (ie, ulcers or nodular lesions), and parts of the body affected (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients Treated With Miltefosine

| Leishmania Species | Exposure Location | Age, y | Sex | Lesion(s) | Prior Treatment | Outcome After Miltefosine; Retreatment for Failure |

Imiquimod Use | Days Treated | Cumulative Dosea, mg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

L. aethiopica

|

Ethiopia | 27 | F | Face (cheek) | None | Cure | No | 28 | 2100 |

| Ethiopia | 43 | F | Face (nose) | None | Stopped early (AEs); L-AmB | Yes | 10 | 1500 | |

| Ethiopia | 44 | F | Face (nose) | None | Relapse, MCL; L-AmB/milt | Yes | 56 | 8400b | |

| Ethiopia | 47 | M | Face (lip) | None | Cure | No | 28 | 4200 | |

|

L. braziliensis

|

Honduras | 47 | M | Leg/knee | L-AmB | Relapse; L-AmB/milt | No | 56 | 8400b |

| Honduras | 72 | M | Arm, multiple | ITC, L-AmB | Relapses; L-AmB/milt, PR topical | No | 28 | 4200 | |

| Peru | 30 | F | Flank, multiple | L-AmB | Cure | No | 28 | 3500 | |

| Peru | 21 | M | Hand | None | Failure to respond; L-AmB | No | 28 | 4200 | |

| Peru | 43 | F | Forearm, left | None | Cure | Yes | 28 | 3500 | |

| Belize | 67 | M | Arm, multiple | Surgical excision | Cure | No | 28 | 3850 | |

| Peru | 43 | F | Forearm, right | None | Cure | Yes | 28 | 4200 | |

| L. infantum chagasi | El Salvador | 26 | F | Face (cheek) | L-AmB | Cure | No | 25 | 2500 |

| L. infantum | Spain | 60 | M | Ear | None | Cure | No | 28 | 2800 |

| Italy | 84 | M | Hand | None | Cure | No | 7 | 1050 | |

| L. major | Morocco | 66 | F | Face, extremities | FLC, L-AmB | Cure | No | 28 | 2800 |

| L. mexicana | Ecuador | 60 | F | Face (cheek) | None | Cure | No | 25 | 3750 |

|

L. panamensis

|

Costa Rica | 15 | F | Neck | KTC, topical GEN | Cure | No | 28 | 4200 |

| Costa Rica | 70 | F | Legs, mucosa | L-AmB, FLC, KTC | Cure | No | 56 | 5600b | |

| Costa Rica | 52 | M | Extremities, torso | KTC | Cure | Yes | 28 | 4200 | |

| Costa Rica | 29 | F | Arm, flank | None | Cure | Yes | 28 | 3850 | |

| Costa Rica | 23 | F | Arm | None | Cure | Yes | 28 | 4200 | |

|

L. tropica

|

Pakistan | 33 | F | Face, arms | None | Cure | No | 28 | 4200 |

| Afghanistan | 8 | M | Face (cheek) | SSG, IL-MA | Cure | Yes | 28 | 2125 | |

| Unspeciated |

Suriname | 62 | M | Leg, multiple | SSG | Cure | No | 9 | 1350 |

| Honduras | 40 | M | Face (cheek) | None | Cure | No | 28 | 4200 | |

| Peru | 68 | M | Lower leg/shin | None | Relapse; thermal therapy | Yes | 28 | 4200 |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; F, female; FLC, fluconazole; GEN, gentamicin; IL-MA, intralesional meglumine antimoniate; ITC, itraconazole; KTC, ketoconazole; L-AmB, liposomal amphotericin B; L-AmB/milt, liposomal amphotericin B/miltefosine combination therapy (course of miltefosine given either concurrently with or followed by AmBisome 3 mg/kg/day for 7–10 days); M, male; MCL, mucocutaneous leishmaniasis; PR, paromomycin; SSG, sodium stibogluconate.

aCumulative dose refers to first course of treatment.

bPatient received 2 consecutive courses for partial response to initial course.

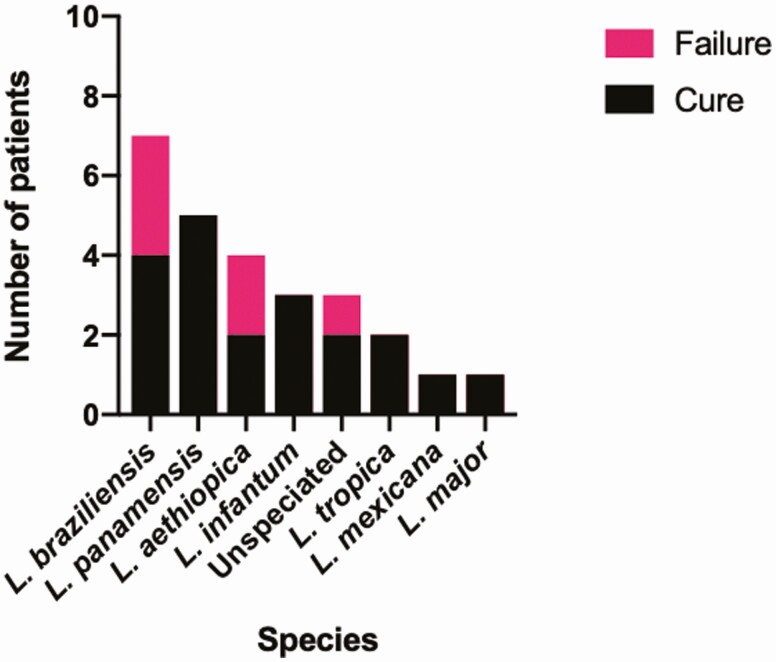

Efficacy of Miltefosine

Overall, 77% (20/26) of patients met criteria for cure, which occurred among each of the species included in this study (Figure 1). Cures occurred in L. panamensis acquired in Costa Rica (n = 5); L. braziliensis acquired in Peru (n = 3) and Belize (n = 1); L. mexicana acquired in Ecuador (n = 1), L. infantum acquired in El Salvador (n = 1), Spain (n = 1), and Italy (n = 1); L. major from Morocco (n = 1); L. tropica from Afghanistan (n = 1) and Pakistan (n = 1); L. aethiopica from Ethiopia (n = 2); an unspeciated case acquired in Honduras (n = 1); and an unspeciated case acquired in Suriname (n = 1). Of the 26 patients treated with miltefosine, 9 received imiquimod concurrently.

Figure 1.

Clinical response to miltefosine by Leishmania species.

Cures were recorded in participants who were treated at doses lower than current weight-based guidelines [8], as well as in patients who required dose reductions due to AEs. This included 2 participants who stopped treatment prematurely at 7 and 9 days after developing gout. Nevertheless, both had epithelialization of lesions at 5 weeks and 2 months posttreatment, respectively.

Six (23%) cases failed to meet criteria for cure, including 4 relapses, 1 failure to respond, and 1 early discontinuation due to adverse effects. These occurred in L. braziliensis acquired in Honduras (n = 2) and Peru (n = 1), L. aethiopica acquired in Ethiopia (n = 2), and an unspeciated case acquired in Peru. Two patients with L. braziliensis acquired in Honduras who had relapsed after initial treatment with L-AmB were treated with miltefosine. After relapsing again after treatment with miltefosine, both were then treated with combination therapy consisting of L-AmB and miltefosine. One has had a prolonged remission following combination therapy, whereas the other experienced multiple relapses and recently has been treated with topical paromomycin [9], with outcome pending. An unspeciated case acquired in Peru with relapse after miltefosine was retreated successfully with thermal therapy. In 1 case of L. aethiopica on immunosuppressive therapy, the cutaneous lesion healed with an extended course of miltefosine, but the patient later developed MCL, which was treated with L-AmB/miltefosine combination therapy. Although the nasal lesions healed after treatment, the patient relapsed again a year later, and responded to a second course of L-AmB/miltefosine combination therapy. Of the remaining cases, 1 case of L. braziliensis acquired in Peru showed no response to a standard course of treatment, and a case of L. aethiopica discontinued miltefosine after 10 days due to adverse effects. Both of these patients were successfully treated with L-AmB.

Tolerability

Adverse events were common, with gastrointestinal symptoms occurring in 97% (24/26), predominantly nausea, lack of appetite, and vomiting (Table 2). The onset of AEs typically occurred within 1–2 weeks of starting treatment. Overall, 8 patients (31%) had mild or self-limited AEs, 15 (58%) had moderate AEs, and 3 (11.5%) suffered severe AEs leading to early discontinuation of the drug.

Table 2.

Adverse Events Associated With Miltefosine

| Event Type and Adverse Event | Affecteda, No. (%) (n = 26) |

|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal | |

| Nausea | 24 (92) |

| Decreased appetite | 14 (54) |

| Vomiting | 12 (46) |

| Abdominal pain | 10 (38) |

| Diarrhea | 6 (23) |

| Genitourinary (n = 12 males) | |

| Testicular pain | 2 (8) |

| Epididymitis | 1 (4) |

| Testicular swelling | 1 (4) |

| Decreased ejaculate | 1 (4) |

| Discoloration of ejaculate | 1 (4) |

| Musculoskeletal | |

| Gout | 3 (12) |

| Back pain | 1 (4) |

| Neurologic | |

| Dizziness | 1 (4) |

| Headache | 1 (4) |

| Distal neuropathy | 1 (4) |

| Depression | 1 (4) |

| Skin | |

| Itching | 2 (8) |

| General | |

| Fatigue/malaise | 8 (31) |

| Fever | 1 (4) |

| Abnormal laboratory values | |

| Creatinine elevated | 8 (31) |

| Liver function tests elevatedb | 8 (31) |

| Amylase elevated | 7 (27) |

| Lipase elevated | 6 (23) |

| Uric acid elevated | 2 (8) |

aNumber affected of n = 26, except genitourinary events, which all occurred in males (n = 12).

bAlanine aminotransferase, 3 (12%); aspartate aminotransferase, 2 (8%); alkaline phosphatase, 2 (8%); indirect bilirubin, 1 (4%).

Overall, 73% of patients who experienced AEs required some form of clinical intervention, with 9 of 26 (31%) prescribed antiemetic therapy (ondansetron) to control nausea and/or vomiting. Five of these also had dose reductions allowing completion of a 28-day course. In 4 cases (15%), treatment was started at a lower dose (ie, 50 twice daily for 1–2 weeks) then advanced to 50 mg 3 times daily if well tolerated. Of the 3 patients who discontinued treatment early, 2 patients with a previous history of gout stopped treatment early after developing gout. The third stopped after developing multiple symptoms including nausea, fatigue, and dizziness. Laboratory test abnormalities associated with treatment returned to baseline levels following completion of treatment.

DISCUSSION

Efficacy of using miltefosine to treat the many species that cause CL is limited. Our experience reported here documents that miltefosine has broad efficacy to a variety of both Old and New World Leishmania species from diverse geographic regions. While our population was both small and varied, close monitoring during treatment and during extended posttreatment intervals (most for >1 year) yielded important safety data allowing comparison of AEs associated with miltefosine vs other standard therapies. Pentostam, available without cost through the CDC Drug Service by an investigational new drug protocol, is administered intravenously for 20 days and is associated with cardiotoxicity (electrocardiographic abnormalities) and other side effects including myalgias, arthralgias, elevated aminotransferases, marked chemical pancreatitis and occasionally symptomatic pancreatitis, and intravenous or peripherally inserted central catheter line complications. AEs commonly associated with L-AmB, used off-label in the US for treatment of CL, include infusion reactions, increased creatinine, hypokalemia, and abnormal liver function tests, among others.

The recommended dosing of miltefosine we used for CL was based on earlier studies for VL; there have been few dose-ranging treatment studies employing lower doses or shorter courses for miltefosine in CL [10]. The long half-life of miltefosine [4] could also help explain healing of some of our patients who stopped the drug prematurely. No standard dosing recommendations exist for use of miltefosine in children, and data on efficacy in children are scarce [11, 12]. Dosing in children is more complicated due to faster metabolism of the drug and higher failure rates with weight-based dosing [4]. Alternative dosing strategies have been proposed in children, with some early clinical evidence supporting this strategy [13].

Treatment efficacy among Leishmania species is frequently variable depending on geographic area. Approval of miltefosine by the FDA was primarily based on its efficacy and safety in the treatment of New World species [10, 14–16]. Data supporting efficacy in New World CL is limited to randomized trials performed in specific geographic locations, and in descriptive series in which the species were either identified diagnostically or assumed based on epidemiologic data [8]. Of the 3 patients with L. braziliensis who had treatment failures with miltefosine in this study (3/7 [43%]), 2 with relapses had acquired CL after traveling together to a remote area of Honduras, while the other patient had acquired CL in the Amazonian area of Peru, highlighting likely geographic variation of species. In addition, the 2 patients with L. braziliensis from Honduras had failed other treatments prior to use of miltefosine, suggesting more treatment-refractory infections. A systematic review of therapeutic interventions for localized Old World CL revealed significant gaps in knowledge due to lack of standardization of research, limited sample sizes, and failure to identify the species of Leishmania [17]. Additionally, there is 1 report of Canadian soldiers who served in Afghanistan [18]. A systematic review of treatment of CL caused by L. aethiopica reported that antimonials were the drugs almost exclusively employed; only a few cases were reported supporting efficacy of miltefosine [19, 20].

While most AEs associated with miltefosine, such as nausea and decreased appetite, are well recognized, the recurrence of gout in 3 participants with prior history of gout represents previously unreported AEs. One patient who received multiple courses of miltefosine developed gout during 2 separate treatment courses, but in later treatment courses with miltefosine received prophylaxis without recurrence of gout. The mechanism is unclear and increases in serum uric acid associated with gout episodes have not been observed. Two other participants with no history of gout had mild uric acid elevations while on treatment, without developing symptoms of gout. All the AEs described in this study resolved following completion of therapy. While ocular complications of leishmaniasis are uncommon [21] and were not found in our cohort, recent case reports have described ocular effects including acute scleritis, corneal ulceration, and keratitis occurring in patients treated with miltefosine for longer treatment courses for post–kala azar dermal leishmaniasis [22–24].

Limitations of the data include a small sample size with diverse clinical manifestations, and changes in clinical practice that occurred during the course of the conduct of the protocol. The proportion of cures on imiquimod is 6 of 9 (66.7%) compared to 14 of 17 (82.4%) for those not who did not receive imiquimod concurrently with miltefosine, but the difference is not significant (difference, −15.7% [95% confidence interval, −54.2% to 23.4%]; P = .42). None of the patients who developed gout had been treated with imiquimod.

Miltefosine received orphan drug designation in 2006, in part due to the unmet need for an oral agent for CL that was effective and well-tolerated [25]. Miltefosine was developed as a public-private partnership to repurpose the drug to treat VL in India. It became registered in various countries for both VL and CL, and was listed as an essential medicine by the World Health Organization in 2011. In the US, it received orphan drug status, was approved by the FDA, and was awarded a tropical disease Priority Review Voucher. Broader use has been limited by lack of efficacy data, availability, potential teratogenicity, and cost [4, 26]. The potential for development of resistance, which has been demonstrated in vitro, is another concern.

CONCLUSIONS

Results from this analysis suggest a potential role for miltefosine as a viable treatment option for both New World and Old World CL species. It is more easily administered, arguably better tolerated, and with efficacy comparable to other standard therapies. Further research is needed to determine the efficacy of miltefosine in CL, particularly in Old World Leishmania species; to ascertain the optimal dosing of miltefosine; and to characterize the range, frequency, and impact of adverse effects in larger population groups. Finally, providing access to treatment of this neglected tropical disease remains a significant challenge.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the staff of the Clinical Parasitology Section, Laboratory of Parasitic Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, and the participants who contributed to this research.

Financial support. This work was supported by the NIAID Intramural Research Program, NIH.

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Leishmaniasis. Available at: https://www.who.int/leishmaniasis/en/. Accessed 15 June 2020.

- 2.Boggild AK, Caumes E, Grobusch MP, et al. Cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis in travellers and migrants: a 20-year GeoSentinel Surveillance Network analysis. J Travel Med 2019; 26:taz055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aronson NE, Joya CA. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: updates in diagnosis and management. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2019; 33:101–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dorlo TP, Balasegaram M, Beijnen JH, de Vries PJ. Miltefosine: a review of its pharmacology and therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of leishmaniasis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012; 67:2576–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Food and Drug Administration. Miltefosine package insert. Silver Spring, MD: FDA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miranda-Verástegui C, Llanos-Cuentas A, Arévalo I, Ward BJ, Matlashewski G. Randomized, double-blind clinical trial of topical imiquimod 5% with parenteral meglumine antimoniate in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Peru. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 40:1395–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Department of Health and Human Services. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) version 5 Published November 27 2017. Available at: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_5x7.

- 8.Ramanathan R, Talaat KR, Fedorko DP, Mahanty S, Nash TE. A species-specific approach to the use of non-antimony treatments for cutaneous leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2011; 84:109–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soto J, Soto P, Ajata A, et al. Topical 15% paromomycin-aquaphilic for bolivian leishmania braziliensis cutaneous leishmaniasis: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 68:844–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soto J, Toledo J, Gutierrez P, et al. Treatment of American cutaneous leishmaniasis with miltefosine, an oral agent. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 33:E57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uribe-Restrepo A, Cossio A, Desai MM, Dávalos D, Castro MDM. Interventions to treat cutaneous leishmaniasis in children: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018; 12:e0006986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castro MDM, Cossio A, Velasco C, Osorio L. Risk factors for therapeutic failure to meglumine antimoniate and miltefosine in adults and children with cutaneous leishmaniasis in Colombia: a cohort study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017; 11:e0005515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mbui J, Olobo J, Omollo R, et al. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of an allometric miltefosine regimen for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in Eastern African children: an open-label, phase II clinical trial. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 68:1530–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soto J, Arana BA, Toledo J, et al. Miltefosine for new world cutaneous leishmaniasis. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 38:1266–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Machado PR, Ampuero J, Guimarães LH, et al. Miltefosine in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania braziliensis in Brazil: a randomized and controlled trial. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2010; 4:e912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burza S, Croft SL, Boelaert M. Leishmaniasis. Lancet 2018; 392:951–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heras-Mosteiro J, Monge-Maillo B, Pinart M, et al. Interventions for Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 12:CD005067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keynan Y, Larios OE, Wiseman MC, Plourde M, Ouellette M, Rubinstein E. Use of oral miltefosine for cutaneous leishmaniasis in Canadian soldiers returning from Afghanistan. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2008; 19:394–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Griensven J, Gadisa E, Aseffa A, Hailu A, Beshah AM, Diro E. Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania aethiopica: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2016; 10:e0004495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fikre H, Mohammed R, Atinafu S, van Griensven J, Diro E. Clinical features and treatment response of cutaneous leishmaniasis in north-west Ethiopia. Trop Med Int Health 2017; 22:1293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Modarreszadeh M, Manshai K, Shaddel M, Oormazdi H. Ocular leishmaniasis. Iran J Ophthalmol 2006; 19:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saurabh S, Mahabir M. Adverse ocular events on miltefosine treatment for post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis in India. Trop Doct 2020; 50:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maruf S, Nath P, Islam MR, et al. Corneal complications following post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis treatment. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018; 12:e0006781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pradhan A, Basak S, Chowdhury T, Mohanta A, Chatterjee A. Keratitis after post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Cornea 2018; 37:113–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berman J. Miltefosine, an FDA-approved drug for the “orphan disease,” leishmaniasis. Expert Opin Orphan Drugs 2015; 3:727–35. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sunyoto T, Potet J, Boelaert M. Why miltefosine—a life-saving drug for leishmaniasis—is unavailable to people who need it the most. BMJ Glob Health 2018; 3:e000709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]