BACKGROUND:

Research has demonstrated a possible relation between patients’ preoperative lifestyle and postoperative complications.

OBJECTIVE:

This study aimed to assess associations between modifiable preoperative lifestyle factors and postoperative complications in patients undergoing elective surgery for colorectal cancer.

DESIGN:

This is a retrospective study of a prospectively maintained database.

SETTING:

At diagnosis, data on smoking habits, alcohol consumption, BMI, and physical activity were collected by using questionnaires. Postoperative data were gathered from the nationwide database of the Dutch ColoRectal Audit.

PATIENTS:

Patients (n = 1564) with newly diagnosed stage I to IV colorectal cancer from 11 Dutch hospitals were included in a prospective observational cohort study (COLON) between 2010 and 2018.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES:

Multivariable logistic regression models were used to identify which preoperative lifestyle factors were associated with postoperative complications.

RESULTS:

Postoperative complications occurred in 28.5%, resulting in a substantially prolonged hospital stay (12 vs 5 days, p < 0.001). Independently associated with higher postoperative complication rates were ASA class II (OR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.05–2.04; p = 0.03) and III to IV (OR, 3.17; 95% CI, 1.96–5.12; p < 0.001), current smoking (OR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.02–2.56; p = 0.04), and rectal tumors (OR, 1.81; 95%CI, 1.28–2.55; p = 0.001). Body mass index, alcohol consumption, and physical activity did not show an association with postoperative complications. However, in a subgroup analysis of 200 patients with ASA III to IV, preoperative high physical activity was associated with fewer postoperative complications (OR, 0.17; 95% CI, 0.03–0.87; p = 0.04).

LIMITATIONS:

Compared with most studied colorectal cancer populations, this study describes a relatively healthy study population with 87.2% of the included patients classified as ASA I to II.

CONCLUSIONS:

Modifiable lifestyle factors such as current smoking and physical activity are associated with postoperative complications after colorectal cancer surgery. Current smoking is associated with an increased risk of postoperative complications in the overall study population, whereas preoperative high physical activity is only associated with a reduced risk of postoperative complications in patients with ASA III to IV. See Video Abstract at http://links.lww.com/DCR/B632.

LA ASOCIACIÓN ENTRE FACTORES MODIFICABLES DEL ESTILO DE VIDA Y COMPLICACIONES POSOPERATORIAS EN CIRUGÍA ELECTIVA EN PACIENTES CON CÁNCER COLORECTAL

ANTECEDENTES:

Estudios han demostrado una posible relación entre el estilo de vida preoperatorio de los pacientes y las complicaciones posoperatorias.

OBJETIVO:

Evaluar las asociaciones entre los factores de estilo de vida preoperatorios modificables y las complicaciones posoperatorias en pacientes llevados a cirugía electiva por cáncer colorrectal.

DISEÑO:

Estudio retrospectivo de una base de datos continua de forma prospectiva.

ESCENARIO:

En el momento del diagnóstico se recopilaron mediante cuestionarios datos sobre tabaquismo, consumo de alcohol, el IMC y la actividad física. Los datos posoperatorios se obtuvieron de la base de datos nacional de la Auditoría Colorectal Holandesa.

PACIENTES:

Se incluyeron pacientes (n = 1564) de once hospitales holandeses con cáncer colorrectal en estadio I-IV recién diagnosticado incluidos en un estudio de cohorte observacional prospectivo (COLON) entre 2010 y 2018.

PRINCIPALES VARIABLES ANALIZADAS:

Se utilizaron modelos de regresión logística multivariable para identificar qué factores de estilo de vida preoperatorios y se asociaron con complicaciones posoperatorias.

RESULTADOS:

Las complicaciones posoperatorias se presentaron en el 28,5%, lo que resultó en una estancia hospitalaria considerablemente mayor (12 contra 5 días, p <0,001). De manera independiente se asociaron con mayores tasas de complicaciones posoperatorias la clasificación ASA II (OR 1,46; 95% IC 1,05-2,04, p = 0,03) y III-IV (OR 3,17; 95% IC 1,96-5,12, p <0,001), tabaquismo presente (OR 1,62; IC 95% 1,02-2,56, p = 0,04) y tumores rectales (OR 1,81; IC 95% 1,28-2,55, p = 0,001). El IMC, el consumo de alcohol y la actividad física no mostraron asociación con complicaciones posoperatorias. Sin embargo, en un análisis de subgrupos de 200 pacientes ASA III-IV, la actividad física íntensa preoperatoria se asoció con menos complicaciones posoperatorias (OR 0,17; IC del 95%: 0,03-0,87, p = 0,04).

LIMITACIONES:

En comparación con las poblaciones de cáncer colorrectal más estudiadas, este estudio incluyó una población relativamente sana con el 87,2% de los pacientes incluidos clasificados como ASA I-II.

CONCLUSIONES:

Los factores modificables del estilo de vida, como son el encontrarse fumando y la actividad física, se asocian con complicaciones posoperatorias después de la cirugía de cáncer colorrectal. El encontrarse fumando se asocia con un mayor riesgo de complicaciones posoperatorias en la población general del estudio, mientras que la actividad física íntensa preoperatoria se asocia con un menor riesgo de complicaciones posoperatorias únicamente en pacientes ASA III-IV. Consulte Video Resumen en http://links.lww.com/DCR/B632.

Keywords: Colorectal neoplasms, Colorectal surgery, Lifestyle, Postoperative complications

With a global incidence of over 1 million cases, colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer (10.2%) and the second leading cause of cancer death (9.2% of the total cancer deaths).1 Surgery is the cornerstone of the curative treatment of patients with CRC, carrying a substantial postoperative risk of morbidity and mortality.2 Possible complications of colorectal surgery include minor complications such as pneumonia, wound infection, and deep vein thrombosis and major adverse events such as anastomotic leakage and mortality.3 The introduction of early recovery after surgery has, among other improvements in perioperative care, contributed to a significant decrease in postoperative complications after colorectal surgery from approximately 55% to 30%.3

Increasing patients’ functional capacity before surgery would potentially allow them to retain a higher level of functional capacity over their entire surgical admission.4 This has led to the introduction of prehabilitation programs in many centers worldwide to enhance functional exercise capacity in patients with the intent to minimize postoperative morbidity and accelerate postsurgical recovery.4

Several pilot studies have been performed to study the clinical outcome of prehabilitation in CRC surgery.5–7 The results are contradictory, possibly due to the current methodological heterogeneity of the programs, resulting in limited comparability.8 Some prehabilitation programs concentrate on multiple modifiable patient-related factors, such as physical exercise, nutritional status, smoking, and psychological well-being, whereas others focus on only 1 factor. These areas of focus were provided by studies regarding patient-related risk factors for postoperative complications after CRC surgery. The identified risk factors can be divided into unmodifiable patient-related factors, such as higher age, male sex, and comorbidity,9–12 and modifiable factors, including cigarette smoking, impaired functional capacity, alcohol consumption, and impaired nutritional status.13–16 These latter factors could be important factors in prehabilitation programs.

Studies investigating risk factors for postoperative complications are often conducted within a small sample size or do not solely focus on CRC surgery. Therefore, with prospectively collected data from a large cohort of patients with CRC, we aim to determine whether modifiable lifestyle factors are associated with postoperative complications in patients undergoing elective surgery for newly diagnosed CRC. Based on previous studies, we hypothesized that current and former smoking, low BMI, and high alcohol consumption are associated with increased postoperative complications, whereas increased physical activity is associated with fewer postoperative complications.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Population

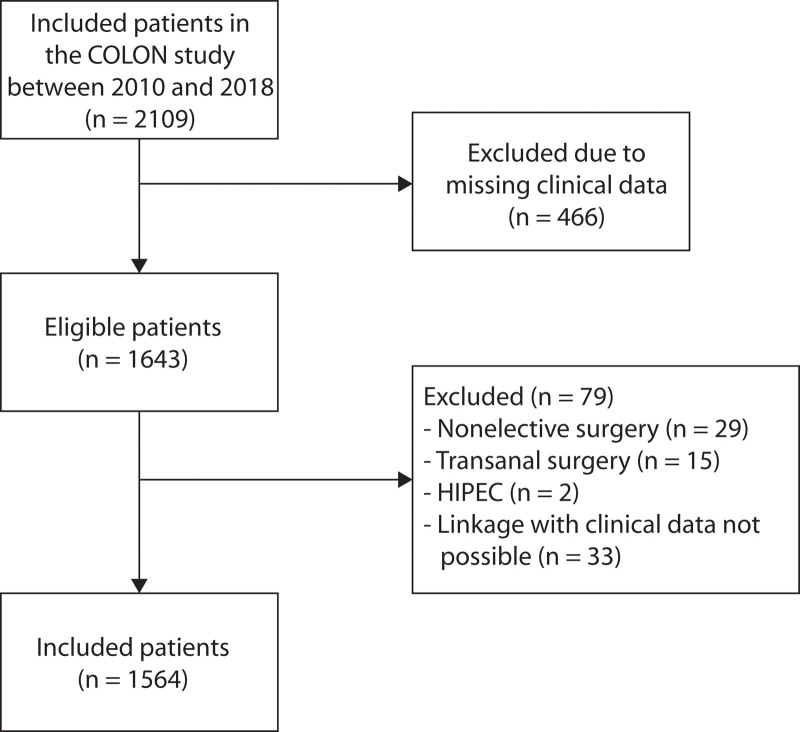

Our study population consists of patients included between August 2010 and December 2018 in the ongoing “Colorectal cancer: Longitudinal, Observational study on Nutritional and lifestyle factors that influence colorectal tumor recurrence, survival and quality of life” (COLON) study.17 In this cohort study, preoperative data were collected from patients with newly diagnosed CRC in 11 hospitals in the Netherlands. Patients were excluded when they had a history of CRC, (partial) bowel resection, chronic IBD, a hereditary CRC syndrome, dementia or another mental condition, or were non-Dutch speaking. In our study, 466 patients had to be excluded because of missing clinical data. Furthermore, nonelective patients (n = 29) and patients undergoing transanal surgery (n = 15) or hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (n = 2) were also excluded. For 33 patients, linkage to clinical data was not possible. Therefore, a total of 1564 patients were available for analysis, as shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram showing the inclusion of patients with colorectal cancer. HIPEC = hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

Data Collection

Preoperative data regarding lifestyle factors were collected from self-administered questionnaires completed by the patients shortly after diagnosis. Smoking status was classified as never, former, and current. Body mass index was calculated with self-reported body weight and height and divided into 4 categories in accordance with clinical guidelines, <20, 20 to 24.99, 25 to 30, and ≥30 kg/m2. Alcohol consumption was categorized as <1, 1 to 14, or >14 units per week, with 1 unit defined as containing 10 g of alcohol, equivalent to 1 glass of beer or wine or 1 measure of spirits.18 Physical activity was assessed with the validated Short QUestionnaire to ASsess Health enhancing physical activity (SQUASH).19 In accordance with the Dutch physical activity guideline, a division was made between <150 and >150 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous activity per week.20 Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity was defined as activities with a metabolic equivalent value ≥3, such as walking, cycling, and sports.21 Extra subgroups were made consisting of 150 to 500, 500 to 1000, and ≥1000 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous activity per week.

Postoperative data were obtained from the Dutch ColoRectal Audit, a nationwide, Web-based database that contains data about the perioperative period of all patients undergoing surgery for CRC in The Netherlands.22 Tumor location was divided into right colon (proximal to the splenic flexure), left colon (distal to and including the splenic flexure), and rectum. The tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification at the time of diagnosis was used for staging.23 Because clinical staging of CRC is relatively unreliable,24 pathological TNM staging took precedence over clinical staging, except in the case of missing pathological data or treatment with neoadjuvant radiotherapy.

Outcome

The primary outcome of this study was the occurrence of postoperative complications after elective CRC surgery. Surgical complications were considered severe when equivalent to Clavien-Dindo classification 3 to 5,25 such as anastomotic leakage or mortality due to a surgical complication. Mild surgical complications were defined as Clavien-Dindo 1 to 2,25 including wound infections opened at bedside, pharmacological treatments, or blood transfusions. Nonsurgical complications included pulmonal, cardiac, neurological, infectious, or thromboembolic complications. Because of a change in data collection at the Dutch ColoRectal Audit, complications before 2018 were registered 30 days postsurgery, whereas complications since 2018 were registered up to 90 days postsurgery. If no complications occurred, patients were analyzed as “no complication.” A secondary outcome measure was duration of postoperative hospital stay, measured in days.

Statistical Analyses

Population characteristics at diagnosis were described for the total study population and stratified by no complications versus complications. To maintain sufficient group sizes, only smoker status regardless of pack-years was used for analyses. Continuous variables were presented as median with their total range and categorical variables as absolute numbers and percentage. Between-group analysis of continuous variables was performed using the Mann-Whitney U test. The Pearson χ2 test and Fisher exact test were used to compare categorical variables. Logistic regression models were used to estimate ORs and corresponding 95% CIs for the univariable relation between each patient- and tumor-related characteristic as independent variable and the occurrence of postoperative complications as dependent variable. Furthermore, multivariable logistic regression was performed including all patient- and tumor-related characteristics, after which manual backward elimination was performed to determine confounders. If the removal of a characteristic resulted in at least a 10% change in the OR of 1 of the 4 lifestyle factors of interest (smoking, alcohol consumption, BMI, or physical activity), that variable was kept in the model. All other variables were removed from the model. We performed these analyses for complications in general, nonsurgical complications, surgical complications, severe surgical complications, and mild surgical complications. Because we expected to find the largest effect in patients with comorbidity, we also performed the logistic regression models for patients with ASA I to II only and patients with ASA III to IV only. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) and p values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Population Characteristics

Median age of the included patients was 66 years (range 31–93), 64% were male, and 87.2% were classified as ASA I or II (Table 1). Of 1564 included patients, 1077 (68.9%) were diagnosed with colon cancer and 487 (31.1%) were diagnosed with rectal cancer. A total of 446 patients (28.5%) experienced 1 or more postoperative complications. Patients who were 70 years of age and older (p = 0.003), male (p < 0.001), or (former) smokers (p = 0.01) developed postoperative complications more frequently than patients who were younger than 70 years, female, and never smokers (Table 1). Furthermore, patients with a higher ASA score (p < 0.001) and with rectal cancer (p < 0.001) more often had a postoperative complication. Patients who experienced a complication had a substantially prolonged hospital stay (12 vs 5 days, p < 0.001). Of the current smokers, the majority (n = 115) had more than 15 pack-years. As shown in Table 2, 271 patients (17.3%) developed surgical postoperative complications and 175 patients (11.2%) developed nonsurgical complications.

TABLE 1.

Population characteristics at diagnosis, overall, and by postoperative complication

| Clinical variables | All patients | No postoperative complication | Postoperative complication | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Total | 1564 | 100 | 1118 | 71.5 | 446 | 28.5 | |

| Patient characteristics | |||||||

| Age | |||||||

| Median (range) | 66.3 (31–93) | 65.9 (31–93) | 67.3 (31–90) | 0.001a | |||

| <70 y | 1029 | 65.8 | 761 | 68.1 | 268 | 60.1 | 0.003b |

| ≥70 y | 535 | 34.2 | 357 | 31.9 | 178 | 39.9 | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 1004 | 64.2 | 684 | 61.2 | 320 | 71.7 | <0.001b |

| Female | 560 | 35.8 | 434 | 38.8 | 126 | 28.3 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||||

| Median (range) | 26.0 (15.9–49.5) | 26.0 (15.9–48.2) | 26.4 (18.1–49.5) | 0.18a | |||

| <20 | 47 | 3.0 | 36 | 3.2 | 11 | 2.5 | 0.83b |

| 20–25 | 563 | 36.0 | 400 | 35.8 | 163 | 36.5 | |

| 25–30 | 674 | 43.1 | 485 | 43.4 | 189 | 42.4 | |

| ≥30 | 280 | 17.9 | 197 | 17.6 | 83 | 18.6 | |

| Smoking habits | |||||||

| Never | 443 | 28.3 | 332 | 29.7 | 111 | 24.9 | 0.01b |

| Former smoker | 769 | 49.1 | 565 | 50.5 | 204 | 45.7 | |

| Current smoker | 157 | 10.1 | 95 | 8.5 | 62 | 13.9 | |

| Unknown | 195 | 12.5 | 126 | 11.3 | 69 | 15.5 | |

| Alcohol units (per week) | |||||||

| Median (range) | 5.8 (0–87.4) | 5.7 (0–73.2) | 6.2 (0–87.4) | 0.18a | |||

| <1 | 411 | 26.3 | 302 | 27.0 | 109 | 24.4 | 0.11b |

| 1–14 | 659 | 42.1 | 487 | 43.6 | 172 | 38.6 | |

| >14 | 380 | 24.3 | 259 | 23.2 | 121 | 27.1 | |

| Unknown | 114 | 7.3 | 70 | 6.3 | 44 | 9.9 | |

| Physical activity (per week)c | |||||||

| Median (range) | 662.5 (0–5220) | 690.0 (0–5220) | 600.0 (0–4500) | 0.06a | |||

| <150 min | 130 | 8.3 | 90 | 8.1 | 40 | 9.0 | 0.41b |

| 150–500 min | 414 | 26.5 | 289 | 25.8 | 125 | 28.0 | |

| 500–1000 min | 396 | 25.3 | 293 | 26.2 | 103 | 23.1 | |

| >1000 min | 438 | 28.0 | 323 | 28.9 | 115 | 25.8 | |

| Unknown | 186 | 11.9 | 123 | 11.0 | 63 | 14.1 | |

| Educationd | |||||||

| Elementary | 71 | 4.5 | 49 | 4.4 | 22 | 4.9 | 0.25b |

| Lower | 808 | 51.7 | 578 | 51.7 | 230 | 51.6 | |

| Intermediate | 102 | 6.5 | 69 | 6.2 | 33 | 7.4 | |

| Higher | 469 | 30.0 | 354 | 31.7 | 115 | 25.8 | |

| Unknown | 114 | 7.3 | 68 | 6.1 | 46 | 10.3 | |

| Comorbidity | |||||||

| Yes | 1058 | 67.6 | 726 | 64.9 | 332 | 74.4 | <0.001b |

| No | 505 | 32.3 | 391 | 35.0 | 114 | 25.6 | |

| Unknown | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| ASA classification | |||||||

| I | 454 | 29.0 | 365 | 32.6 | 89 | 20.0 | <0.001b |

| II | 910 | 58.2 | 644 | 57.6 | 266 | 59.6 | |

| III–IV | 200 | 12.8 | 109 | 9.7 | 91 | 20.4 | |

| Hospital stay | |||||||

| Median (range) | 5 (2–182) | 5 (2–92) | 12 (2–182) | <0.001a | |||

| <14 days | 1334 | 85.3 | 1080 | 96.6 | 254 | 57.0 | <0.001b |

| ≥14 days | 225 | 14.4 | 34 | 3.0 | 191 | 42.8 | |

| Unknown | 5 | 0.3 | 4 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Intensive care unit admittance | |||||||

| Median (range) | 0 (0–88) | 0 (0–7) | 0 (0–88) | <0.001a | |||

| ≤2 days | 1312 | 83.9 | 989 | 88.5 | 323 | 72.4 | <0.001b |

| >2 days | 92 | 5.9 | 7 | 0.6 | 85 | 19.1 | |

| Unknown | 160 | 10.2 | 122 | 10.9 | 38 | 8.5 | |

| Tumor characteristics | |||||||

| Tumor location | |||||||

| Right-sided colon | 492 | 31.5 | 358 | 32.0 | 134 | 30.0 | <0.001b |

| Left-sided colon | 585 | 37.4 | 466 | 41.7 | 119 | 26.7 | |

| Rectum | 487 | 31.1 | 294 | 26.3 | 193 | 43.3 | |

| Tumor stage | |||||||

| 0–I | 349 | 22.3 | 259 | 23.2 | 90 | 20.2 | 0.46b |

| II | 385 | 24.6 | 282 | 25.2 | 103 | 23.1 | |

| III | 575 | 36.8 | 402 | 36.0 | 173 | 38.8 | |

| IV | 86 | 5.5 | 60 | 5.4 | 26 | 5.8 | |

| Unknown | 169 | 10.8 | 115 | 10.3 | 54 | 12.1 | |

| Differentiation | |||||||

| Well/moderately | 1230 | 78.6 | 891 | 79.7 | 339 | 76.0 | 0.06b |

| Poorly | 111 | 7.1 | 71 | 6.4 | 40 | 9.0 | |

| Unknown | 223 | 14.3 | 156 | 14.0 | 67 | 15.0 | |

| Morphology | |||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 1424 | 91.0 | 1013 | 90.6 | 411 | 92.2 | 0.29b |

| Mucinous | 96 | 6.1 | 70 | 6.3 | 26 | 5.8 | |

| Signet ring cell/other | 12 | 0.8 | 11 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Unknown | 32 | 2.0 | 24 | 2.1 | 8 | 1.8 | |

| Treatment characteristics | |||||||

| Surgical resection | |||||||

| Right-sided colectomy | 451 | 28.8 | 332 | 29.7 | 119 | 26.7 | 0.001b |

| Transverse resection | 23 | 1.5 | 16 | 1.4 | 7 | 1.6 | |

| Left-sided colectomy | 119 | 7.6 | 88 | 7.9 | 31 | 7.0 | |

| Subtotal colectomy | 12 | 0.8 | 4 | 0.4 | 8 | 1.8 | |

| Anterior/sigmoid resection | 849 | 54.3 | 614 | 54.9 | 235 | 52.7 | |

| Abdominoperineal resection | 110 | 7.0 | 64 | 5.7 | 46 | 10.3 | |

| Approach | |||||||

| Laparoscopic | 1183 | 75.6 | 856 | 76.6 | 322 | 72.2 | 0.17b |

| Open | 372 | 23.8 | 256 | 22.9 | 116 | 26.0 | |

| Unknown | 9 | 0.6 | 6 | 0.5 | 8 | 1.8 | |

| Conversion | 0.14e | ||||||

| No | 1559 | 99.7 | 1116 | 99.8 | 443 | 99.3 | |

| Yes | 5 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.7 | |

| Anastomotic procedure | |||||||

| Anastomosis | 1128 | 72.1 | 867 | 77.5 | 261 | 58.5 | <0.001b |

| Defunctioning stoma | 250 | 16.0 | 140 | 12.5 | 110 | 24.7 | |

| End-ileostomy | 12 | 0.8 | 4 | 0.4 | 8 | 1.8 | |

| End-colostomy | 159 | 10.2 | 97 | 8.7 | 62 | 13.9 | |

| Unknown | 15 | 1.0 | 10 | 0.9 | 5 | 1.1 | |

Mann Whitney U test.

Pearson χ2 test.

Minutes of moderate-to-vigorous activity per week.

Educational levels were defined as: Elementary school, lower (an equivalent to the Dutch VMBO and MBO), intermediate (an equivalent to the Dutch HAVO and VWO), higher (an equivalent to the Dutch HBO and university).

Fisher exact test, due to expected count less than 5 in at least 20% of the cells.

TABLE 2.

Overview of postoperative complications

| Postoperative complications | All patients (n = 1564) | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Surgicala | 271 | 17.3 |

| Severe | 168 | 10.7 |

| Mild | 103 | 6.6 |

| Nonsurgicalb | 175 | 11.2 |

| Pulmonary | 79 | 5.1 |

| Cardiac | 38 | 2.4 |

| Thromboembolic | 8 | 0.5 |

| Infectious | 55 | 3.5 |

| Neurological | 16 | 1.0 |

| Other | 129 | 8.2 |

Surgical postoperative complications were subdivided into mild and severe. A complication was considered severe in case of a reintervention, anastomotic leakage, or mortality. All other surgical complications were classified as mild.

Nonsurgical postoperative complications were subdivided into several categories.

Separate analysis of surgical complications only (subdivided into severe and mild) and nonsurgical complications only resulted in small groups leading to no significant association with lifestyle factors. Therefore, further analyses were performed with all complications.

Lifestyle Factors and Postoperative Complications

In multivariable logistic regression analyses, current smoking (vs never smoking) was associated with postoperative complications (OR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.02–2.56; p = 0.04; Table 3). Likewise, current smokers also had an increased chance of developing nonsurgical complications (OR, 2.21; 95% CI, 1.08–4.52; p = 0.03) (results not shown). Higher chances of postoperative complications were seen in patients with ASA class II (OR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.05–2.04; p = 0.03) and ASA class III to IV (OR, 3.17; 95% CI, 1.96–5.12; p < 0.001), both compared with ASA class I. Rectal cancer was also associated with an increased risk of complications (OR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.28–2.55; p = 0.001), in comparison with right-sided colon cancer. Independently associated with fewer postoperative complications was left-sided colon cancer (OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.45–0.93; p < 0.02) in contrast to right-sided colon cancer. Other modifiable lifestyle factors such as BMI, alcohol consumption, and physical activity were not independently associated with postoperative complications in general (all p values > 0.05; Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Uni- and multivariable logistic analyses of preoperative risk factors of postoperative complications in general

| Clinical variables | Total, n | No complication vs complication Crude OR (95% CI)a | p value crude | Multivariable analysis, n | No complication vs complication Adjusted OR (95% CI)b | p value adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||||||

| Age | ||||||

| <70 y | 1029 | 1 | 774 | 1 | ||

| ≥70 y | 535 | 1.42 (1.13–1.78) | 0.003 | 378 | 1.19 (0.89–1.59) | 0.24 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 560 | 1 | 413 | 1 | ||

| Male | 1004 | 1.61 (1.27–2.05) | <0.001 | 739 | 1.19 (0.87–1.62) | 0.28 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||

| <20 | 47 | 0.75 (0.37–1.51) | 0.42 | 35 | 0.73 (0.30–1.80) | 0.49 |

| 20–25 | 563 | 1 | 408 | 1 | ||

| 25–30 | 674 | 0.96 (0.75–1.23) | 0.72 | 508 | 1.21 (0.88–1.65) | 0.24 |

| ≥30 | 280 | 1.03 (0.76–1.42) | 0.84 | 201 | 0.98 (0.65–1.48) | 0.94 |

| Smoking habits | ||||||

| Never | 443 | 1 | 352 | 1 | ||

| Former smoker | 769 | 1.09 (0.84–1.42) | 0.53 | 676 | 0.88 (0.64–1.20) | 0.41 |

| Current smoker | 157 | 2.02 (1.37–2.96) | <0.001 | 124 | 1.62 (1.02–2.56) | 0.04 |

| Alcohol units (per week) | ||||||

| <1 | 411 | 1 | 323 | 1 | ||

| 1–14 | 659 | 0.98 (0.74–1.29) | 0.88 | 515 | 0.86 (0.61–1.20) | 0.37 |

| ≥14 | 380 | 1.29 (0.95–1.76) | 0.10 | 314 | 1.12 (0.76–1.64) | 0.57 |

| Physical activity (per week) | ||||||

| < 150 min | 130 | 1 | 102 | 1 | ||

| 150–500 min | 414 | 0.97 (0.64–1.49) | 0.90 | 354 | 1.07 (0.65–1.77) | 0.79 |

| 500–1000 min | 396 | 0.79 (0.51–1.22) | 0.29 | 333 | 0.85 (0.51–1.42) | 0.53 |

| >1000 min | 438 | 0.80 (0.52–1.23) | 0.31 | 363 | 0.88 (0.52–1.46) | 0.61 |

| ASA classification | ||||||

| I | 454 | 1 | 345 | 1 | ||

| II | 910 | 1.69 (1.29–2.22) | <0.001 | 683 | 1.46 (1.05–2.04) | 0.03 |

| III–IV | 200 | 3.42 (2.38–4.92) | <0.001 | 124 | 3.17 (1.96–5.12) | <0.001 |

| Tumor characteristics | ||||||

| Tumor location | ||||||

| Right-sided colon | 492 | 1 | 358 | 1 | ||

| Left-sided colon | 585 | 0.68 (0.51–0.91) | 0.01 | 431 | 0.65 (0.45–0.93) | 0.02 |

| Rectum | 487 | 1.75 (1.34–2.30) | <0.001 | 363 | 1.81 (1.28–2.55) | 0.001 |

Calculated by using univariable logistic regression analysis.

Multiple logistic regression with backwards elimination of all preoperative variables. Adjusted for the variables shown in the table and tumor differentiation.

Subgroup Analyses

Population characteristics of 200 patients with ASA class III to IV are described in Table 4. A total of 91 patients (45.5%) developed 1 or more postoperative complications. Multivariable logistic analyses showed that physical activity >1000 min/wk was independently associated with a reduced risk of postoperative complications (OR, 0.17; 95% CI, 0.03–0.87; p = 0.04) compared with <150 min/wk (Table 5). There were no other statistically significant differences regarding modifiable lifestyle factors between the complication group compared with the noncomplication group.

TABLE 4.

Population characteristics at diagnosis in a subgroup analysis with 200 patients with ASA class III and IV

| Clinical variables | All patients | No postoperative complication | Postoperative complication | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Total | 200 | 100 | 109 | 54.5 | 91 | 45.5 | |

| Patient characteristics | |||||||

| Age | |||||||

| Median (range) | 70.4 (45–92) | 71.3 (53–92) | 70.0 (45–90) | 0.43a | |||

| <70 y | 89 | 44.5 | 45 | 41.3 | 44 | 48.4 | 0.32b |

| ≥70 y | 111 | 55.5 | 64 | 58.7 | 47 | 51.6 | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 150 | 75.0 | 82 | 75.2 | 68 | 74.7 | 0.94b |

| Female | 50 | 25.0 | 27 | 24.8 | 23 | 25.3 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||||

| Median (range) | 26.0 (15.9–49.5) | 26.6 (15.9–48.2) | 26.8 (18.1–49.5) | 0.95a | |||

| <20 | 5 | 34.5 | 1 | 0.9 | 4 | 4.4 | 0.42c |

| 20–25 | 69 | 2.5 | 37 | 33.9 | 32 | 35.2 | |

| 25–30 | 75 | 37.5 | 44 | 40.4 | 31 | 34.1 | |

| ≥30 | 51 | 25.5 | 27 | 24.8 | 24 | 26.4 | |

| Smoking habits | |||||||

| Never | 42 | 21.0 | 22 | 20.2 | 20 | 22.0 | 0.08b |

| Former smoker | 94 | 47.0 | 58 | 53.2 | 36 | 39.6 | |

| Current smoker | 23 | 11.5 | 9 | 8.3 | 14 | 15.4 | |

| Unknown | 41 | 20.5 | 20 | 18.3 | 21 | 23.1 | |

| Alcohol units (per week) | |||||||

| Median (range) | 3.79 (0–60.6) | 4.09 (0–60.6) | 3.46 (0–42.2) | 0.68a | |||

| <1 | 63 | 31.5 | 36 | 33.0 | 27 | 29.7 | 0.47b |

| 1–14 | 66 | 33.0 | 40 | 36.7 | 26 | 28.6 | |

| >14 | 45 | 22.5 | 22 | 20.2 | 23 | 25.3 | |

| Unknown | 26 | 13.0 | 11 | 10.1 | 15 | 16.5 | |

| Physical activity (per week)d | |||||||

| Median (range) | 540.0 (0–2970) | 709.2 (0–2970) | 495.0 (0–2310) | 0.13a | |||

| <150 min | 30 | 15.0 | 15 | 13.8 | 15 | 16.5 | 0.21b |

| 150–500 min | 45 | 22.5 | 24 | 22.0 | 21 | 23.1 | |

| 500–1000 min | 46 | 23.0 | 22 | 20.2 | 24 | 26.4 | |

| >1000 min | 39 | 19.5 | 27 | 24.8 | 12 | 13.2 | |

| Unknown | 40 | 20.0 | 21 | 19.3 | 19 | 20.9 | |

| Educatione | |||||||

| Elementary | 16 | 8.0 | 10 | 9.2 | 6 | 6.6 | 0.69b |

| Lower | 96 | 48.0 | 56 | 51.4 | 40 | 44.0 | |

| Intermediate | 13 | 6.5 | 7 | 6.4 | 6 | 6.6 | |

| Higher | 47 | 23.5 | 23 | 21.1 | 24 | 26.4 | |

| Unknown | 28 | 14.0 | 13 | 11.9 | 15 | 16.5 | |

| Hospital stay | |||||||

| Median (range) | 7.0 (2–93) | 5.0 (2–16) | 12.50 (3–93) | <0.001a | |||

| <14 days | 152 | 76.0 | 104 | 95.4 | 48 | 52.7 | <0.001b |

| ≥14 days | 46 | 23.0 | 4 | 3.7 | 42 | 46.2 | |

| Unknown | 2 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 1.1 | |

| Intensive care unit admittance | |||||||

| Median (range) | 0 (0–88) | 0 (0–4) | 0 (0–88) | <0.001a | |||

| ≤2 days | 156 | 78.0 | 95 | 87.2 | 61 | 67.0 | <0.001b |

| >2 days | 30 | 15.0 | 3 | 2.8 | 27 | 29.7 | |

| Unknown | 14 | 7.0 | 11 | 10.1 | 3 | 3.3 | |

| Tumor characteristics | |||||||

| Tumor Location | |||||||

| Right-sided colon | 71 | 35.5 | 39 | 35.8 | 32 | 35.2 | 0.26b |

| Left-sided colon | 67 | 33.5 | 41 | 37.6 | 26 | 28.6 | |

| Rectum | 62 | 31.0 | 29 | 26.6 | 33 | 36.3 | |

| Tumor stage | |||||||

| 0–I | 38 | 19.0 | 23 | 21.1 | 15 | 16.5 | 0.76b |

| II | 56 | 28.0 | 29 | 26.6 | 27 | 29.7 | |

| III | 62 | 31.0 | 32 | 29.4 | 30 | 33.0 | |

| IV | 13 | 6.5 | 8 | 7.3 | 5 | 5.5 | |

| Unknown | 31 | 15.5 | 17 | 15.6 | 14 | 15.4 | |

| Differentiation | |||||||

| Well/moderately | 147 | 73.5 | 83 | 76.1 | 64 | 70.3 | 0.02b |

| Poorly | 18 | 9.0 | 5 | 4.6 | 13 | 14.3 | |

| Unknown | 35 | 17.5 | 21 | 19.3 | 14 | 15.4 | |

| Morphology | |||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 178 | 89.0 | 96 | 88.1 | 82 | 90.1 | 0.93b |

| Mucinous | 20 | 10.0 | 11 | 10.1 | 9 | 9.9 | |

| Unknown | 2 | 1.0 | 2 | 1.8 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Treatment characteristics | |||||||

| Surgical resection | |||||||

| Right-sided colectomy | 61 | 30.5 | 32 | 29.4 | 29 | 47.5 | 0.31c |

| Transverse resection | 4 | 2.0 | 3 | 2.8 | 1 | 25.0 | |

| Left-sided colectomy | 18 | 9.0 | 14 | 12.8 | 4 | 22.2 | |

| (Sub)total colectomy | 2 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 50.0 | |

| Anterior/sigmoid resection | 97 | 48.5 | 51 | 46.8 | 46 | 47.4 | |

| Abdominoperineal resection | 18 | 9.0 | 8 | 7.3 | 10 | 55.6 | |

| Approach | |||||||

| Laparoscopic | 146 | 73.0 | 78 | 71.6 | 68 | 74.7 | 0.53b |

| Open | 53 | 26.5 | 31 | 28.4 | 22 | 24.2 | |

| Unknown | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.1 | |

| Conversion | 0.59c | ||||||

| No | 197 | 98.5 | 108 | 99.1 | 89 | 97.8 | |

| Yes | 3 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.9 | 2 | 2.2 | |

| Anastomotic procedure | |||||||

| Anastomosis | 131 | 65.5 | 79 | 72.5 | 52 | 57.1 | 0.06c |

| Defunctioning stoma | 32 | 16.0 | 12 | 11.0 | 20 | 22.0 | |

| End-ileostomy | 4 | 2.0 | 1 | 0.9 | 3 | 3.3 | |

| End-colostomy | 31 | 15.5 | 16 | 14.7 | 15 | 16.5 | |

| Unknown | 2 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 1.1 | |

Mann-Whitney U test.

Pearson χ2 test.

Fisher exact test, due to expected count less than 5 in at least 20% of the cells.

Minutes of moderate-to-vigorous activity per week.

Educational levels were defined as: Elementary school, lower (an equivalent to the Dutch VMBO and MBO), intermediate (an equivalent to the Dutch HAVO and VWO), higher (an equivalent to the Dutch HBO and university).

TABLE 5.

Uni- and multivariable logistic analyses of preoperative risk factors of postoperative complications in a subgroup analysis with 200 patients with ASA class III and IV

| Clinical variables | Total, n | No complication vs complication Crude OR (95% CI)a | p value crude | Multivariable analysis, n | No complication vs complication Adjusted OR (95% CI)b | p value adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||||||

| Age | ||||||

| <70 y | 89 | 1 | 52 | 1 | ||

| ≥70 y | 111 | 0.75 (0.43 – 1.32) | 0.32 | 62 | 0.59 (0.22–1.59) | 0.30 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 50 | 1 | 30 | 1 | ||

| Male | 150 | 0.97 (0.51–1.85) | 0.94 | 84 | 0.51 (0.15–1.75) | 0.29 |

| BMI | ||||||

| <20 | 5 | 4.63 (0.49–43.53) | 0.18 | 3 | 0.00 (0.00–∞) | |

| 20–25 | 69 | 1 | 40 | 1 | ||

| 25–30 | 75 | 0.82 (0.42–1.58) | 0.54 | 42 | 0.75 (0.24–2.35) | 0.62 |

| ≥30 | 51 | 1.03 (0.50–2.12) | 0.94 | 29 | 0.33 (0.09–1.25) | 0.10 |

| Smoking habits | ||||||

| Never | 42 | 1 | 30 | 1 | ||

| Former smoker | 94 | 0.68 (0.33–1.40) | 0.30 | 69 | 0.71 (0.21–2.41) | 0.58 |

| Current smoker | 23 | 1.83 (0.66–5.11) | 0.25 | 15 | 1.08 (0.20–5.91) | 0.93 |

| Alcohol units per week | ||||||

| <1 | 63 | 1 | 42 | 1 | ||

| 1–14 | 66 | 0.87 (0.43–1.75) | 0.69 | 44 | 0.71 (0.21–2.35) | 0.57 |

| ≥14 | 45 | 1.39 (0.65–3.01) | 0.40 | 28 | 1.50 (0.34–6.66) | 0.59 |

| Physical activity (per week) | ||||||

| <150 min | 30 | 1 | 23 | 1 | ||

| 150–500 min | 45 | 0.88 (0.35–2.21) | 0.78 | 33 | 0.31 (0.07–1.39) | 0.13 |

| 500–1000 min | 46 | 1.09 (0.44–2.74) | 0.85 | 32 | 0.46 (0.10–2.01) | 0.30 |

| >1000 min | 39 | 0.44 (0.17–1.19) | 0.11 | 26 | 0.17 (0.03–0.87) | 0.03 |

| Tumor characteristics | ||||||

| Tumor location | ||||||

| Right-sided colon | 71 | 1 | 44 | 1 | ||

| Left-sided colon | 67 | 0.77 (0.39–1.52) | 0.46 | 33 | 1.66 (0.07–41.60) | 0.76 |

| Rectum | 62 | 1.39 (0.70–2.75) | 0.35 | 37 | 0.72 (0.02–23.62) | 0.85 |

Calculated by using univariable logistic regression analysis.

Multiple logistic regression with backwards elimination of all preoperative variables. Adjusted for the variables shown in the table, education, tumor differentiation, stage, morphology, surgical resection, and anastomotic procedure.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis in the subgroup of 1364 patients with ASA class I to II resulted in an association of current smoking with higher postoperative complications (OR, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.08–2.97; p = 0.02), similar to the result of the entire study population. Other modifiable lifestyle factors were not associated with postoperative complications in this analysis.

DISCUSSION

This study is based on prospectively collected data and describes the association between lifestyle factors and complications in patients with CRC who underwent elective surgery. Smoking, ASA class ≥II, and rectal cancer were the most important risk factors for postoperative complications after CRC surgery. In contrast, BMI, alcohol consumption, and physical activity were not associated with postoperative complications in general. In a subgroup analysis of 200 patients with ASA class III to IV, preoperative physical activity of >1000 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous activity per week resulted in fewer postoperative complications.

Current smokers had an increased risk of developing postoperative complications in general (OR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.02–2.56), a result similar to previously published studies.14,26,27 Smoking results in decreased tissue oxygenation due to the peripheral vasoconstrictive effects of nicotine, preference of hemoglobin to bind carbon monoxide instead of oxygen, and induced platelet aggregation resulting in microvascular occlusions. These effects, combined with reduced transportation of leukocytes to infected areas due to the impaired blood flow, contribute to the overall decreased resistance to infections.28 However, whether smoking is causative, or a marker for other comorbidities that result from smoking and impact the outcome of surgery, could not be determined with the available data. The finding that former smokers do not have an increased risk of postoperative complications compared with never smokers differs from a study, also based on questionnaires, that showed that former smokers also had an increased postoperative risk.26 However, a systematic review concluded that intensive smoking cessation interventions initiated at least 4 weeks before surgery are potentially beneficial in reducing the incidence of postoperative complications and can even change smoking behavior in the long term.29 Because almost one-fifth (17%) of the total Dutch population is classified as daily smokers, an active preoperative smoking cessation program should be considered for patients undergoing CRC surgery.30

Recent studies focusing on BMI have found that underweight patients are more likely to have postoperative complications after CRC surgery than patients with normal weight.31,32 Remarkably, this was not observed in the present study population and could be explained by the low numbers of patients with underweight (3.0% had a BMI <20) in a relatively healthy study population (87.2% were classified as ASA I–II). This might be explained by the fact that only patients who underwent elective surgery were included in the COLON study, which could have resulted in the exclusion of underweight patients with more advanced disease and worse clinical conditions. Because underweight in cancer is often a sign of more advanced disease, increased postoperative complication rates after CRC surgery might be a result of the advanced character of the disease and not of the low BMI itself.31

In contrast to some earlier findings, we could not demonstrate a relation between alcohol consumption of ≥14 units per week and postoperative complications. In previous studies, alcohol consumption has been associated with increased risk of anastomotic leakage. but the amount of alcohol units per week leading to this increased risk varied. In 1 study with 2237 patients, >14 units per week yielded to an increased postoperative complication risk (OR, 3.7; 95% CI, 1.6–8.3) compared to <14.33 Another study only observed an association when >35 units per week were consumed (relative risk, 7.18; 95% CI, 1.20–43.01) compared with abstainers in a study population of 333 patients.14 A Danish inquiry (n = 3550) found an increased risk with >42 units per week (OR, 2.48; 95% CI, 1.07–5.77) compared to <42 units.26 In our cohort, relatively few patients had an alcohol intake of >14 units per week (n = 380) and therefore we were unable to stratify alcohol consumption into additional groups with increasing units per week. Similarly, patients with severe obesity were not common in our population (n = 280) and, to maintain sufficient group sizes, it was not possible to further subdivide patients with a BMI ≥30.

Our observation that physical activity has a relation with postoperative complications in patients with ASA class III to IV CRC is in line with other studies.26,34,35 This relation was not present for all patients in the present study, which could again be because most patients in our study were in a relatively good clinical condition with already appropriate physical activity. Some studies have shown that physical activity below average is significantly associated with increased risk of postoperative complications in general,26,34 whereas Heldens et al35 reported that increased physical activity resulted in fewer postoperative complications in a population of 75 patients with CRC. On the other hand, a recent randomized study by Carli et al8 in elderly patients with CRC did not show an effect with a prehabilitation program that consists of active physical activity. Because physical activity of >1000 min/wk results in approximately 2.5 hours of activity per day, feasibility should be considered before advising young and elderly patients. Further research evaluating the association of increased physical activity with postoperative complications in patients with CRC needs to be established in future trials.

The present study has several strengths. First, long-term, prospectively collected data in a large population of patients with CRC were analyzed. Second, the extensive questionnaires used in the COLON study provided the opportunity to adjust for many covariates that could potentially confound our associations. Another important strength of this study is the focus on multiple lifestyle factors at the same time, because many studies only focus on 1 variable. However, the current study also has some limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the results. First, the preoperative data provided by the COLON study are based on questionnaires. Therefore, exposure to cigarettes and alcohol consumption was self-reported and thus subject to possible understated reporting and misclassification. Second, because of the relatively small number of patients with complications, subgroup analysis was not possible for only surgical complications or specific complications such as anastomotic leakage. Third, 87.2% of all included patients were classified as ASA class I to II. Because the COLON study is a longitudinal study with multiple questionnaires at several moments in time,17 it is reasonable to assume that healthier patients were more likely to join the study, whereas patients in worse condition could have preferred fewer commitments. Fourth, because several end points, such as length of hospital stay and quality of life, were not included in the present analysis, the studied modifiable risk factors could be associated with these end points.

Because the occurrence of postoperative complications appears to be related to modifiable preoperative lifestyle factors, the introduction of a (multimodal) prehabilitation program may result in fewer postoperative complications. Several studies have been performed investigating the effects of such programs. However, the results are contradicting. In a recent systematic review it was concluded that prehabilitation consisting of inspiratory muscle training, aerobic exercise, and resistance training appears to decrease the incidence of all postoperative complications in patients undergoing intra-abdominal operations.36 However, in another systematic review, the positive effects on patient’s fitness were acknowledged, but no evidence of impact on postoperative clinical outcomes after elective abdominal surgery was shown.37 Although the present study did not measure the impact of lifestyle interventions, the results provide insight into which preoperative modifiable factors could be important factors in prehabilitation programs. Our results suggest that influencing preoperative modifiable lifestyle factors other than current smoking does not reduce postoperative complications in a general population of patients with CRC. Therefore, prehabilitation programs might not be beneficial for all patients with CRC,8 but prehabilitation focused on increasing physical activity for patients with ASA class III to IV could be beneficial in decreasing postoperative complications after CRC surgery.6

CONCLUSION

This study of 1564 patients with CRC shows that current smoking is a significant risk factor for complications after elective CRC surgery. Subgroup analyses of 200 patients with ASA class III to IV found that over 1000 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per week decreases the chance of developing postoperative complications. To establish other possible associations between preoperative modifiable lifestyle factors and postoperative complications in patients with ASA class III to IV after CRC surgery, additional research in a large population is required.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all participants, the involved coworkers at the participating hospitals, and the COLON investigators at Wageningen University & Research.

APPENDIX

COLON Collaborators

Peter van Duijvendijk; Henk K. van Halteren; Bibi M. E. Hansson; Ewout A. Kouwenhoven; Flip M. Kruyt; Paul C. van de Meeberg; Renzo Pieter Veenstra; Evertine Wesselink; Moniek van Zutphen.

Affiliations Collaborators

Peter van Duijvendijk, Gelre Hospital, Apeldoorn, the Netherlands; Henk K. van Halteren, Admiraal de Ruyter Ziekenhuis, Goes, the Netherlands; Bibi M. E. Hansson, Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital, Nijmegen, the Netherlands; Ewout A. Kouwenhoven, Hospital Group Twente (ZGT), Almelo, the Netherlands; Flip M. Kruyt, Hospital Gelderse Vallei, Ede, the Netherlands; Paul C. van de Meeberg, Slingeland Hospital, Doetinchem, the Netherlands; Renzo P. Veenstra, Martini Hospital, Groningen, The Netherlands; Evertine Wesselink, Division of Human Nutrition, Wageningen University & Research, Wageningen, the Netherlands; Moniek van Zutphen, Division of Human Nutrition, Wageningen University & Research, Wageningen, the Netherlands.

Footnotes

Funding/Support: The COLON study is sponsored by Wereld Kanker Onderzoek Fonds (WCRF-NL) and World Cancer Research Fund International (WCRF International) as well as by funds from grant 2014/1179 as part of the WCRF International Regular Grant Programme); Alpe d’Huzes/Dutch Cancer Society (UM 2012-5653, UW 2013-5927, UM 2015-7946); and ERA-NET on Translational Cancer Research (TRANSCAN/Dutch Cancer Society: UW2013-6397, UW2014-6877) and the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw, the Netherlands). Sponsors were not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript.

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Ethical Approval: The COLON study was approved by the Committee on Research involving Human Subjects, region Arnhem-Nijmegen, Netherlands (2009-349).

Poster presentation (virtual) at the meeting of The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, June 8, 2020.

Lisanne Loogman, Lindsey C. F. de Nes, Johannes H. W. de Wilt, and Fränzel J. B. van Duijnhoven contributed equally to this article.

Contributor Information

Peter van Duijvendijk, Gelre Hospital, Apeldoorn, the Netherlands.

Henk K. van Halteren, Admiraal de Ruyter Ziekenhuis, Goes, the Netherlands

Bibi M. E. Hansson, Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital, Nijmegen, the Netherlands

Ewout A. Kouwenhoven, Hospital Group Twente (ZGT), Almelo, the Netherlands

Flip M. Kruyt, Hospital Gelderse Vallei, Ede, the Netherlands

Paul C. van de Meeberg, Slingeland Hospital, Doetinchem, the Netherlands

Renzo P. Veenstra, Martini Hospital, Groningen, The Netherlands

Evertine Wesselink, Division of Human Nutrition, Wageningen University & Research, Wageningen, the Netherlands.

Moniek van Zutphen, Division of Human Nutrition, Wageningen University & Research, Wageningen, the Netherlands..

Collaborators: Peter van Duijvendijk, Henk K. van Halteren, Bibi M. E. Hansson, Ewout A. Kouwenhoven, Flip M. Kruyt, Paul C. van de Meeberg, Renzo Pieter Veenstra, Evertine Wesselink, Moniek van Zutphen, Peter van Duijvendijk, Henk K. van Halteren, Bibi M. E. Hansson, Ewout A. Kouwenhoven, Flip M. Kruyt, Paul C. van de Meeberg, Renzo P. Veenstra, Evertine Wesselink, and Moniek van Zutphen

REFERENCES

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brouwer NPM, Heil TC, Olde Rikkert MGM, et al. The gap in postoperative outcome between older and younger patients with stage I-III colorectal cancer has been bridged; results from the Netherlands cancer registry. Eur J Cancer. 2019;116:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spanjersberg WR, Reurings J, Keus F, van Laarhoven CJ. Fast track surgery versus conventional recovery strategies for colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(2):CD007635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carli F, Zavorsky GS. Optimizing functional exercise capacity in the elderly surgical population. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2005;8:23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li C, Carli F, Lee L, et al. Impact of a trimodal prehabilitation program on functional recovery after colorectal cancer surgery: a pilot study. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1072–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barberan-Garcia A, Ubré M, Roca J, et al. Personalised prehabilitation in high-risk patients undergoing elective major abdominal surgery: a randomized blinded controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2018;267:50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Rooijen SJ, Molenaar CJL, Schep G, et al. Making patients fit for surgery: introducing a four pillar multimodal prehabilitation program in colorectal cancer. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;98:888–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carli F, Bousquet-Dion G, Awasthi R, et al. Effect of multimodal prehabilitation vs postoperative rehabilitation on 30-day postoperative complications for frail patients undergoing resection of colorectal cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:233–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirchhoff P, Dincler S, Buchmann P. A multivariate analysis of potential risk factors for intra- and postoperative complications in 1316 elective laparoscopic colorectal procedures. Ann Surg. 2008;248:259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bokey L, Chapuis PH, Keshava A, Rickard MJ, Stewart P, Dent OF. Complications after resection of colorectal cancer in a public hospital and a private hospital. ANZ J Surg. 2015;85:128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jafari MD, Jafari F, Halabi WJ, et al. Colorectal cancer resections in the aging US population: a trend toward decreasing rates and improved outcomes. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:557–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tekkis PP, Poloniecki JD, Thompson MR, Stamatakis JD. Operative mortality in colorectal cancer: prospective national study. BMJ. 2003;327:1196–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reilly DF, McNeely MJ, Doerner D, et al. Self-reported exercise tolerance and the risk of serious perioperative complications. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2185–2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sørensen LT, Jørgensen T, Kirkeby LT, Skovdal J, Vennits B, Wille-Jørgensen P. Smoking and alcohol abuse are major risk factors for anastomotic leakage in colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 1999;86:927–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burden ST, Hill J, Shaffer JL, Todd C. Nutritional status of preoperative colorectal cancer patients. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2010;23:402–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Rooijen S, Carli F, Dalton SO, et al. Preoperative modifiable risk factors in colorectal surgery: an observational cohort study identifying the possible value of prehabilitation. Acta Oncol. 2017;56:329–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winkels RM, Heine-Bröring RC, van Zutphen M, et al. The COLON study: Colorectal cancer: Longitudinal, Observational study on Nutritional and lifestyle factors that may influence colorectal tumour recurrence, survival and quality of life. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Latt N, Conigrave K, Saunders JB, Marshall J, Nutt D. Addiction Medicine. 2009.New York: Oxford University Press Inc; [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wendel-Vos GC, Schuit AJ, Saris WH, Kromhout D. Reproducibility and relative validity of the short questionnaire to assess health-enhancing physical activity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:1163–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coumans B, Leurs MTW. Richtlijnen gezond bewegen. Sport Geneeskd. 2001;34:142–146. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, et al. 2011 Compendium of physical activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1575–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Leersum NJ, Snijders HS, Henneman D, et al. ; Dutch Surgical Colorectal Cancer Audit Group. The Dutch surgical colorectal audit. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:1063–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wittekind CF, Greene FL, Hutter RVP, Klimfinger M, Sobin L. TNM Atlas: Illustrated Guide to the TNM/pTNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 2004.5 ed. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brouwer NPM, Stijns RCH, Lemmens VEPP, et al. Clinical lymph node staging in colorectal cancer; a flip of the coin? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44:1241–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nickelsen TN, Jørgensen T, Kronborg O. Lifestyle and 30-day complications to surgery for colorectal cancer. Acta Oncol. 2005;44:218–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma A, Deeb AP, Iannuzzi JC, Rickles AS, Monson JR, Fleming FJ. Tobacco smoking and postoperative outcomes after colorectal surgery. Ann Surg. 2013;258:296–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tarakji B, Cil A, Butin RE, Bernhardt M. adverse effects of smoking on musculoskeletal health. Mo Med. 2017;114:268–271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomsen T, Villebro N, Møller AM. Interventions for preoperative smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(3):CD002294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.RIVM Gestandaardiseerde trend roken volwassenen 1990–2017. 2017. Accessed December 11, 2019. https://www.volksgezondheidenzorg.info/onderwerp/roken/cijfers-context/trends#node-trend-roken-volwassenen

- 31.Arkenbosch JHC, van Erning FN, Rutten HJ, Zimmerman D, de Wilt JHW, Beijer S. The association between body mass index and postoperative complications, 30-day mortality and long-term survival in Dutch patients with colorectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2019;45:160–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Healy LA, Ryan AM, Sutton E, et al. Impact of obesity on surgical and oncological outcomes in the management of colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25:1293–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turrentine FE, Denlinger CE, Simpson VB, et al. Morbidity, mortality, cost, and survival estimates of gastrointestinal anastomotic leaks. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Onerup A, Angenete E, Bonfre P, et al. Self-assessed preoperative level of habitual physical activity predicted postoperative complications after colorectal cancer surgery: a prospective observational cohort study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2019;45:2045–2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heldens AFJM, Bongers BC, Lenssen AF, Stassen LPS, Buhre WF, van Meeteren NLU. The association between performance parameters of physical fitness and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing colorectal surgery: an evaluation of care data. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43:2084–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moran J, Guinan E, McCormick P, et al. The ability of prehabilitation to influence postoperative outcome after intra-abdominal operation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgery. 2016;160:1189–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Doherty AF, West M, Jack S, Grocott MP. Preoperative aerobic exercise training in elective intra-cavity surgery: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110:679–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]