Abstract

Background:

Highly performed nowadays, the pterional craniotomy (PC) has several widespread variants. However, these procedures are associated with complications such as temporalis muscle atrophy, facial nerve frontal branch damage, and masticatory difficulties. The postoperative cranial aesthetic is, nonetheless, the main setback according to patients. This review aims to map different pterional approaches focusing on final aesthetics.

Methods:

This review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement. Studies were classified through the Oxford method. We searched PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library from January 1969 to February 2021 for cohorts and randomized clinical trials that met our inclusion criteria.

Results:

1484 articles were initially retrieved from the databases. 1328 articles did not fit the inclusion criteria. 118 duplicates were found. 38 studies were found eligible for the established criteria. 27 (71.05%) were retrospective cohorts, with low evidence level. Only 5 (13.15%) clinical trials were found eligible to the criteria. The majority of the studies (36/38) had the 2B OXFORD evidence level. A limited number of studies addressed cosmetic outcomes and patient satisfaction. The temporal muscle atrophy or temporal hollowing seems to be the patient’s main complaint. Only 17 (44.73%) studies addressed patient satisfaction regarding the aesthetics, and only 10 (26.31%) of the studies reported the cosmetic outcome as a primary outcome. Nevertheless, minimally invasive approaches appear to overcome most cosmetic complaints and should be performed whenever possible.

Conclusion:

There are several variants of the classic PC. The esthetic outcomes are poorly evaluated. The majority of the studies were low evidence articles.

Keywords: Esthetic outcomes, Patient reported outcomes, Pterional craniotomy

INTRODUCTION

Pterional craniotomy (PC) is a classic approach for all anterior circulation aneurysms, suprasellar tumors (i.e., pituitary adenomas and craniopharyngiomas), and neurosurgeries where the opening of the Sylvian fissure is a crucial step.[1] Described for the 1st time by Yasargil et al., PC continues to be one of the most used nowadays.[2,46] PC has several variants such as the orbitozygomatic (OZ) approach, first proposed by Hakuba et al.[18] Nevertheless, complications such as temporalis muscle atrophy, facial nerve frontal branch damage, and masticatory difficulties are not seldomly observed.[14] However, the low patient satisfaction regarding the pterional approach is mainly a result of postoperative cranial esthetic. These drawbacks have challenged neurosurgeons to improve the original technique to minimize such complications. Thus, novel variants that diminish the exposed area named “mini-pterional” and “nano-pterional” draw increasing attention. Although the neurosurgical field is familiar with the different techniques, few studies have thoroughly assessed them, comparing outcomes. This scoping review aims to address the situation, evaluating the varied forms of PC when it comes to final esthetics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy

This scoping review was made using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement extension for scoping reviews.[42] A scoping review was conducted using MEDLINE/PubMed (NLM), EMBASE and Cochrane Library, the selected articles were from 1969 to February 2021. The MeSH and keywords used in the databases were: “pterional” OR “supraorbital” OR “frontolateral” OR “craniotomy” AND “approaches.”

Study selection

This study intended to gather randomized clinical trials and cohort studies that compared different types of PC from the esthetics point of view. Inclusion criteria were: (a) studies that evaluated PC and its variants, in terms of aesthetics outcomes, (b) randomized clinical trial and cohort studies, and (c) articles written in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. Conversely, we excluded review articles, editorials, letters, comments, and articles that had no related theme to this study, case/series reports, or studies that evaluated the reconstructive surgeries for esthetic repair.

Data extraction

Two researchers (D.B.G and M.I.A.S) selected the studies. Divergences among the article selection as well as to the quality assessment were evaluated by the senior author. The following data were extracted from the studies: (1) general details on the study (author, year of publication, country, study type, time of follow-up, number of patients); (2) type of pterional approach; (3) baseline disease; (4) esthetic outcomes; and (5) complications.

Quality assessment

Studies were classified according to the Oxford method. The quality of the only randomized clinical trial that met the final criteria was assessed trough the JADAD score.[21]

RESULTS

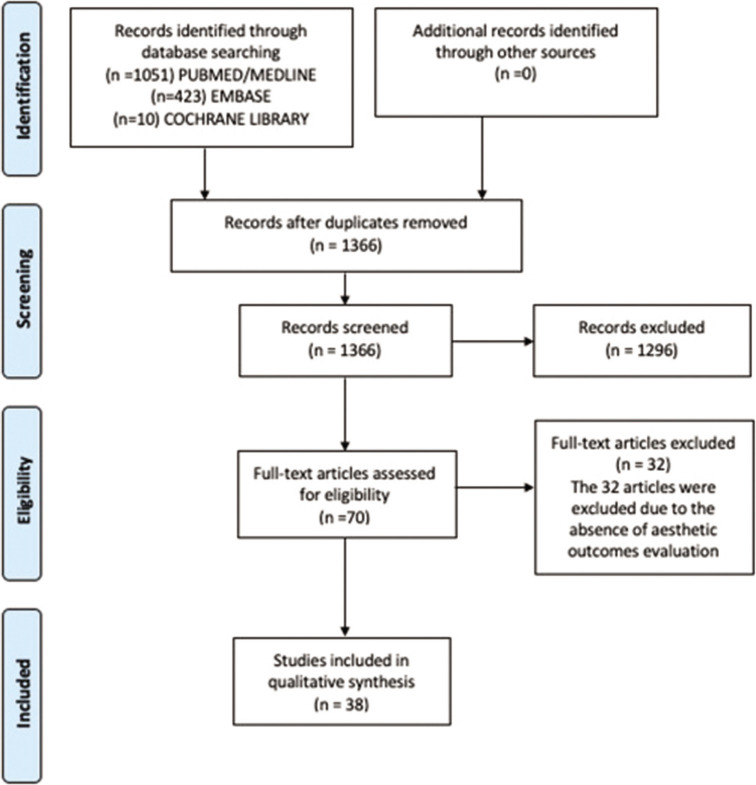

One thousand four hundred and eighty-four articles were retrieved. 38 studies were found eligible for the established criteria (27 retrospective cohort studies, one outcome research, four prospective cohorts, one case–control, and five clinical trials).[1,5-8,10,11,13,17,18,20,21,23-25,28-31,33,34,36-38,41,44,45,48] 118 duplicates were found. 1328 papers were excluded as determined by the exclusion criteria [Figure 1].

Figure 1:

Flowchart of the study.

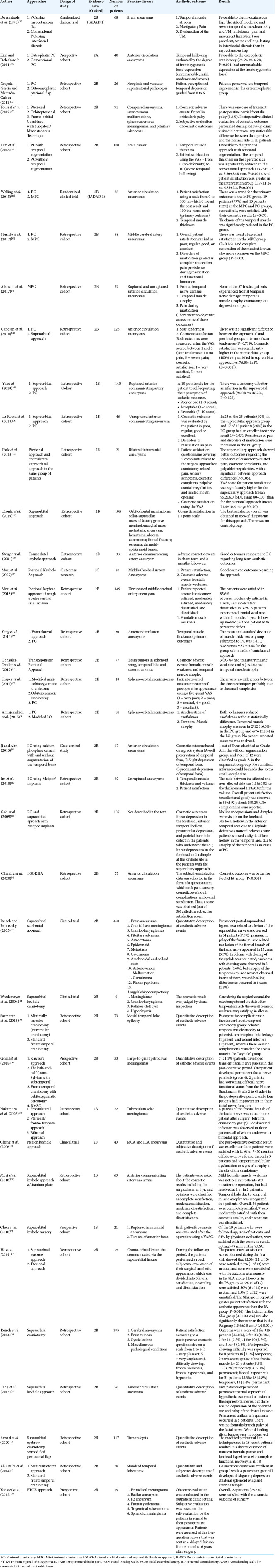

Among the cohorts, four were prospective studies. Most of the articles studied the cosmetic/aesthetic outcomes in intracranial brain aneurysms (27/38). The primary outcomes analyzed were the temporal muscle atrophy (TMA) and frontal nerve palsy, evaluated quantitatively or qualitatively (through patients or health professionals reported outcomes). Over 50% of the studies (31/38) considered aesthetic as a secondary outcome. All main information from each included study are summarized in [Table 1].

Table 1:

Characteristics of the studies assessing different pterional craniotomies.

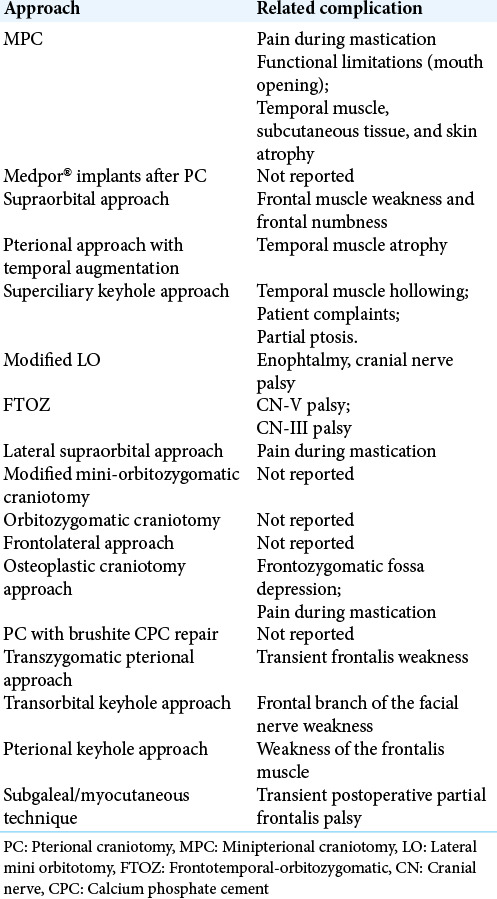

We have identified five studies that compare PC and minimally invasive surgery (MIS) understood as minipterional craniotomy (MPC) and supraorbital variants approach. [26,32,40,43,49] Among these articles, 2 compared PC versus MPC and 3 compared PC versus supraorbital approach. 183 patients were submitted to PC, with 117 (63.93%) good outcomes. 59 patients were submitted to MPC, with 50 (84.74%) good outcomes. 116 patients were submitted to the supraorbital approach, with 109 (93.96%) good outcomes. Main adverse cosmetic events are summarized in [Table 2].

Table 2:

Complications related to different surgical approaches.

DISCUSSION

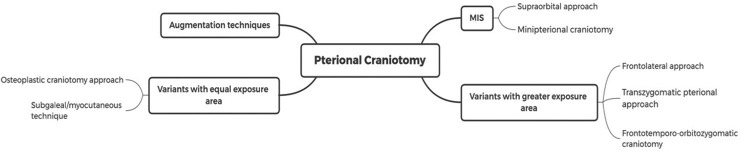

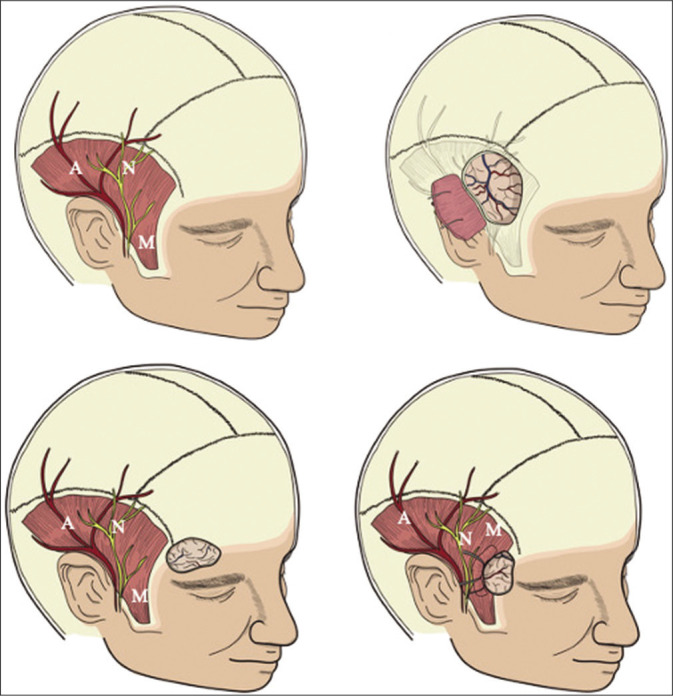

At present, PC is still the most widely used craniotomy to approach vascular and neoplastic diseases in neurosurgical practice.[1,46] Nonetheless, this method is associated with a series of cosmetic and functional issues, such as TMA, facial nerve frontal branch injury, and masticatory difficulties. In light of this, it became of utmost importance to compare different types of PC [Figure 2], from an esthetic point of view. In this scoping review, it was noted that a reduced number of studies addressing cosmetic outcomes and patient satisfaction. Only 10 (26.31%) of the studies addressed patient satisfaction regarding the esthetics, and only 7 (18.42%) of the studies reported the cosmetic outcome as a primary outcome.

Figure 2:

Pterional craniotomy and its variants.

Due to the heterogeneity of the esthetic evaluations carried out among the studies analyzed, we identified that for the purposes of evaluating of aesthetic outcomes, it is important that the evaluation is standardized and that it considers the patient’s evaluation. We identified that the most important aspects to be assessed by the researcher are: temporal hollowing, paresis of the frontal branch of the facial nerve, temporo-mandibular dysfunction, and patient’s visual analogue scale proposed in [Table 3].

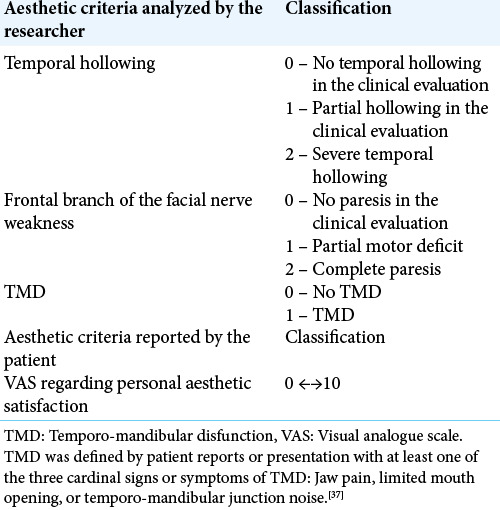

Table 3:

Aesthetic outcomes evaluation proposal regarding the main analyzed variables.

TMA

The TMA or temporal hollowing seems to be the chief complaint of the patients regarding the esthetics issue. Temporal hollowing can cause significant craniomaxillofacial asymmetry, esthetic deformity, and serious cosmetic concern in patients, even when there is an excellent postoperative functional outcome [Figure 3]. Several methods to prevent temporal hollowing have been introduced, all with specific drawbacks. The most straightforward technique to prevent TMA without lesion of the frontalis branch nerve seems to combine subgaleal/myocutaneous technique, described by Youssef et al. (2012).[47] However, a clear description of the methods regarding cosmetic assessment is not described.

Figure 3:

Schematic representation of the minimally invasive approaches compared with standard pterional craniotomy. A – Superficial Temporal Artery; N – Frontal Branch of Facial Nerve; M – Superficial Temporal Muscle. (a) Preoperative illustration of the main affected structures potentially damaged in surgery. (b) Schematic illustration of the standard pterional craniotomy and structures potentially damaged in surgery. (c) Schematic illustration of the supraorbital craniotomy. Note that due to the location of the approach, the main complaints are frontal muscle weakness and frontal numbness. (d) Schematic illustration of the minipterional craniotomy and structures potentially damaged in surgery. This technique aims to minimize temporal hollowing and adverse effects related to the superficial temporal artery and the frontal branch of facial nerve.

Moreover, there was no control group. The “myocutaneous flap,” the “osteoplastic craniotomy” and the “osteomyoplastic craniotomy” are similar techniques that preserve the temporal muscle attached to the bone flap. There was just one randomized control trial and 2 observational studies showing significant differences regarding TMA compared to the conventional PC. However, the operative time may be a drawback of these techniques, which was just explored in one study and favored the conventional PC.[13] Some authors described using autologous bone or cement to “cover” and prevent the temporal hollowing seen postoperatively. Furthermore, the drawback of using the autologous temporal bone is related to the operative time. The mean operative time for temporal augmentation was 45 min in one study. The most cement used is the calcium phosphate cement, but also the use of Medpore is described. The advantage of such techniques is that it probably increases the costs of the surgery.

With the increasing concept of minimally invasive surgeries, techniques such as mini PC, supraorbital, and frontolateral approaches emerged. It seems logical to think that no or less temporal muscle handling, lesser would be the temporal hollowing. The MPC seems to be an excellent option for unruptured anterior circulation aneurysms,[1,39,43] but there are also reports on its use for ruptured aneurysms.[15] These studies showed a decrease in temporal hollowing, pain, and masticatory dysfunctions. The use of a supraciliary incision to perform a supraorbital approach, highly performed and described in the literature by Prof. Romani et al.,[35] may be a matter of discussion regarding the incision esthetics outcome. However, it is non-inferior to the conventional Yasargil et al.[46] incision when it comes to scar tenderness. Moreover, as expected, temporal hollowing is prevented by more conservative approaches.

Temporomandibular dysfunction (TMD)

TMD is one the most described adverse aesthetic event among the studies. However, no adequate quantification of the event was made by the authors. Costa et al.[9] showed a high incidence of muscle pain and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) pain in patients after surgery. This result indicates that the surgery, and most likely the post-operative inflammation, affects the TMJ function of surrounding areas, including the masticatory muscles, which contribute to developing TMD. MIS can possibly minimize the incidence of TMJ related complications.[26,32,49]

Skin incision

Other incisions, such as those to perform the modified miniorbitomy or the pterional keyhole approach, generate concerns since the incision is out of the hairline. However, the patients submitted to the later were overall satisfied with the final esthetic result. As the patients submitted to the miniorbitomy had orbital meningiomas, the central concern was exophthalmos. This study did not evaluate scars.[4]

Patient-reported outcomes (PRO)

PRO are highly relevant. This tool is a regularly used indicator for measuring health care quality.[25] The patient-centered treatment guides the majority of the guidelines today. The esthetic outcomes from the patient’s opinion should be taken into consideration whenever possible. In this scoping review, we found only ten articles evaluating PRO.

Among the 38 articles gathered in this study, 27 (71.05%) were retrospective cohorts, with low evidence levels. Only 5 (13.15%) clinical trials met the criteria with a JADAD score of 1 in 2 studies. The remaining three clinical trials had the JADAD score of 0.4 (10.52%) prospective cohorts were included in the study. These articles had a poor description of the methods used to assess cosmetic outcomes, jeopardizing our analysis. More studies should be performed to properly evaluate PRO and the impacts of the different types of craniotomy in patients’ overall satisfaction.

An important limitation observed in practically all studies is that the analysis of aesthetic aspects in the postoperative period of brain surgery is superficial. This results mainly from the severity of the diseases treated, presenting life-threatening, and risk to functional neurological sequelae. However, components that involve the patient’s quality of life have progressively gained relevance more recently. The use of non-surgical treatments with radiosurgery and embolization of aneurysms requires an improvement in PC techniques.[43] Subjective evaluation of cosmetic outcomes is relevant,[31] but it has a limitation in the evaluation of minimally invasive techniques. The development of scales for esthetics outcomes analysis maybe can bring more precision for comparing surgical techniques. For other surgeries, its possible use of modified Stony Brook Scar Evaluation Scale and Manchester Scar Scale.[25] For PC maybe development of specific cosmetic outcome scale analyzing scar, muscle atrophy and bony deformation can be an interesting idea.

CONCLUSION

This review showed that the prime esthetic outcomes were TMA, frontal branch weakness, and scar. Several alternative techniques to the PC can be adopted to minimize the drawbacks mentioned above, which appear to be successfully overcome by minimally invasive approaches. The use of one procedure over another must consider the baseline disease, area of exposure, and surgeon expertise. Furthermore, temporozygomatic region primary augmentation with bone or other materials safely prevents temporal hollowing. Finally, an adequate evaluation of the various pterional surgeries is still lacking due to the limited prospective high-quality researches.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Gonçalves DB, dos Santos MIA, Cabral LCR, Oliveira LM, Coutinho GCS, Dutra BG, et al. Esthetics outcomes in patients submitted to pterional craniotomy and its variants: A scoping review. Surg Neurol Int 2021;12:461.

Contributor Information

Daniel Buzaglo Gonçalves, Email: danielbuzaglo13@gmail.com.

Maria Izabel Andrade dos Santos, Email: andrademariaizabel05@gmail.com.

Lucas de Cristo Rojas Cabral, Email: lucasdecristorojas@gmail.com.br.

Louise Makarem Oliveira, Email: louisemakarem@gmail.com.

Gabriela Campos da Silva Coutinho, Email: gcscoutinho@hotmail.com.

Bruna Guimarães Dutra, Email: brunagdutraa@gmail.com.

Rodrigo Viana Martins, Email: rodrigovm_pvh@hotmail.com.

Franklin Reis, Email: franklindfreis@gmail.com.

Wellingson Silva Paiva, Email: wellingsonpaiva@icloud.com.

Robson Luis Oliveira de Amorim, Email: amorim.robson@gmail.com.

Study limitations

This article is not a systematic review; therefore it was not submitted in the PROSPERO database. Furthermore, the studies included did not provide a uniform and systemic method to evaluate the aesthetic outcomes when comparing different approaches. This applies also to a viable quantitative analysis since most articles had no specific quantification of the aesthetic adverse events.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alkhalili KA, Hannallah JR, Alshyal GH, Nageeb MM, Abdel Aziz KM. The minipterional approach for ruptured and unruptured anterior circulation aneurysms: Our initial experience. Asian J Neurosurg. 2017;12:466–74. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.180951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almeida da Silva S, Yamaki VN, Fontoura Solla DJ, de Andrade AF, Teixeira MJ, Spetzler RF, et al. Pterional, pretemporal, and orbitozygomatic approaches: Anatomic and comparative study. World Neurosurg. 2018;121:e398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.09.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Otaibi F, Albloushi M, Baeesa S. Minicraniotomy for standard temporal lobectomy: A minimally invasive surgical approach. ISRN Neurol. 2014;2014:532523. doi: 10.1155/2014/532523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amirjamshidi A, Abbasioun K, Amiri RS, Ardalan A, Hashemi SM. Lateral orbitotomy approach for removing hyperostosing en plaque sphenoid wing meningiomas. Description of surgical strategy and analysis of findings in a series of 88 patients with long-term follow up. Surg Neurol Int. 2015;6:79. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.157074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ansari SF, Eisenberg A, Rodriguez A, Barkhoudarian G, Kelly DF. The supraorbital eyebrow craniotomy for intra-and extra-axial brain tumors: A single-center series and technique modification. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2020;19:667–77. doi: 10.1093/ons/opaa217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandra PS, Tej M, Sawarkar D, Agarwal M, Doddamani RS. Fronto-orbital variant of supraorbital keyhole approach for clipping ruptured anterior circulation aneurysms (f-sokha) Neurol India. 2020;68:1019–27. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.294827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen HC, Tzaan WC. Microsurgical supraorbital keyhole approach to the anterior cranial base. J Clin Neurosci. 2010;17:1510–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2010.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng WY, Lee HT, Sun MH, Shen CC. A pterion keyhole approach for the treatment of anterior circulation aneurysms. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2006;49:257–62. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-954575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costa AL, Yasuda CL, França M, Jr, de Freitas CF, Tedeschi H, de Oliveira E, et al. Temporomandibular dysfunction post-craniotomy: Evaluation between pre-and post-operative status. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2014;42:1475–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Andrade FC, Jr, de Andrade FC, de Araujo Filho CM, Filho JC. Dysfunction of the temporalis muscle after pterional craniotomy for intracranial aneurysms. Comparative prospective and randomized study of one flap versus two flaps dieresis. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1998;56:200–5. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x1998000200006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eroglu U, Shah K, Bozkurt M, Kahilogullari G, Yakar F, Dogan İ, et al. Supraorbital keyhole approach: Lessons learned from 106 operative cases. World Neurosurg. 2019;S1878-8750:30060–9. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.12.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Genesan P, Haspani MS, Noor SR. A comparative study between supraorbital keyhole and pterional approaches on anterior circulation aneurysms. Malays J Med Sci. 2018;25:59–67. doi: 10.21315/mjms2018.25.5.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goh DH, Kim GJ, Park J. Medpor craniotomy gap wedge designed to fill small bone defects along cranial bone flap. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2009;46:195–8. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2009.46.3.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez LF, Crawford NR, Horgan MA, Deshmukh P, Zabramski JM, Spetzler RF. Working area and angle of attack in three cranial base approaches: Pterional, orbitozygomatic, and maxillary extension of the orbitozygomatic approach. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:550–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.González-Darder JM, Quilis-Quesada V, Botella-Maciá L. Abordaje pterional transcigomático Parte 2 Experiencia quirúrgica en la patología de base de cráneo [Transzygomatic pterional approach. Part 2: Surgical experience in the management of skull base pathology] Neurocirugia (Astur) 2012;23:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.neucir.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gosal JS, Behari S, Joseph J, Jaiswal AK, Sardhara JC, Iqbal M, et al. Surgical excision of large-to-giant petroclival meningiomas focusing on the middle fossa approaches: The lessons learnt. Neurol India. 2018;66:1434–46. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.241354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grajeda-García FM, Mercado-Caloca F. El colgajo osteomioplástico, una contribución al arte de la neurocirugía [The osteomyoplastic flap, a contribution to neurosurgery] Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2011;49:649–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hakuba A, Liu S, Nishimura S. The orbitozygomatic infratemporal approach: A new surgical technique. Surg Neurol. 1986;26:271–6. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(86)90161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He H, Li W, Cai M, Luo L, Li M, Ling C, et al. Outcomes after pterional and supraorbital eyebrow approach for cranio-orbital lesions communicated via the supraorbital fissure-a retrospective comparison. World Neurosurg. 2019;129:e279–85. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.05.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Im SH, Song J, Park SK, Rha EY, Han YM. Cosmetic reconstruction of frontotemporal depression using polyethylene implant after pterional craniotomy. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:1982726. doi: 10.1155/2018/1982726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji C, Ahn JG. Clinical experience of the brushite calcium phosphate cement for the repair and augmentation of surgically induced cranial defects following the pterional craniotomy. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2010;47:180–4. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2010.47.3.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim E, Delashaw JB., Jr Osteoplastic pterional craniotomy revisited. Neurosurgery. 2011;68(Suppl 1):125–9. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318207b3e3. discussion 129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim JH, Lee R, Shin CH, Kim HK, Han YS. Temporal augmentation with calvarial onlay graft during pterional craniotomy for prevention of temporal hollowing. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2018;19:94–101. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2018.01781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ku D, Koo DH, Bae DS. A prospective randomized control study comparing the effects of dermal staples and intradermal sutures on postoperative scarring after thyroidectomy. J Surg Res. 2020;256:413–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2020.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.La Rocca G, Pepa GM, Sturiale CL, Sabatino G, Auricchio AM, Puca A, et al. Lateral supraorbital versus pterional approach: Analysis of surgical, functional, and patient-oriented outcomes. World Neurosurg. 2018;119:e192–9. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.07.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mori K, Osada H, Yamamoto T, Nakao Y, Maeda M. Pterional keyhole approach to middle cerebral artery aneurysms through an outer canthal skin incision. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2007;50:195–201. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-985837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mori K, Wada K, Otani N, Tomiyama A, Toyooka T, Takeuchi S, et al. Keyhole strategy aiming at minimizing hospital stay for surgical clipping of unruptured middle cerebral artery aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 2018;1:1–8. doi: 10.3171/2017.10.JNS171973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mori K, Wada K, Otani N, Tomiyama A, Toyooka T, Tomura S, et al. Long-term neurological and radiological results of consecutive 63 unruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysms clipped via lateral supraorbital keyhole minicraniotomy. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2018;14:95–103. doi: 10.1093/ons/opx244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakamura M, Roser F, Struck M, Vorkapic P, Samii M. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: Clinical outcome considering different surgical approaches. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:1019–28. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000245600.92322.06. discussion 1028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nassiri F, Price B, Shehab A, Au K, Cusimano MD, Jenkinson MD, et al. life after surgical resection of a meningioma: A prospective cross-sectional study evaluating health-related quality of life. Neuro Oncol. 2019;21(Suppl 1):i32–43. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noy152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park J, Son W, Kwak Y, Ohk B. Pterional versus superciliary keyhole approach: Direct comparison of approach-related complaints and satisfaction in the same patient. J Neurosurg. 2018;130:220–6. doi: 10.3171/2017.8.JNS171167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reisch R, Marcus HJ, Hugelshofer M, Koechlin NO, Stadie A, Kockro RA. Patients’ cosmetic satisfaction, pain, and functional outcomes after supraorbital craniotomy through an eyebrow incision. J Neurosurg. 2014;121:730–4. doi: 10.3171/2014.4.JNS13787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reisch R, Perneczky A. Ten-year experience with the supraorbital subfrontal approach through an eyebrow skin incision. Neurosurgery. 2005;57(Suppl 4):242–55. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000178353.42777.2c. discussion 242-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romani R, Laakso A, Kangasniemi M, Lehecka M, Hernesniemi J. Lateral supraorbital approach applied to anterior clinoidal meningiomas: Experience with 73 consecutive patients. Neurosurgery. 2011;68:1632–47. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318214a840. discussion 1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarmento SA, Rabelo NN, Figueiredo EG. Minimally invasive technique (nummular craniotomy) for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: A comparison of 2 approaches. World Neurosurg. 2020;134:e636–41. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.10.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schiffman EL, Truelove EL, Ohrbach R, Anderson GC, John MT, List T, et al. The research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders. I: Overview and methodology for assessment of validity. J Orofac Pain. 2010;24:7–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shapey J, Jung J, Barkas K, Gullan R, Barazi S, Bentley R, et al. A single centre’s experience of managing spheno-orbital meningiomas: Lessons for recurrent tumour surgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2019;161:1657–67. doi: 10.1007/s00701-019-03977-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steiger HJ, Schmid-Elsaesser R, Stummer W, Uhl E. Transorbital keyhole approach to anterior communicating artery aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:347–52. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200102000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sturiale CL, La Rocca G, Puca A, Fernandez E, Visocchi M, Marchese E, et al. Minipterional craniotomy for treatment of unruptured middle cerebral artery aneurysms. A single-center comparative analysis with standard pterional approach as regard to safety and efficacy of aneurysm clipping and the advantages of reconstruction. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2017;124:93–100. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-39546-3_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang C, Sun J, Xue H, Yu Y, Xu F. Supraorbital keyhole approach for anterior circulation aneurysms. Turk Neurosurg. 2013;23:434–8. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.6160-12.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Welling LC, Figueiredo EG, Wen HT, Gomes MQ, Bor-SengShu E, Casarolli C, Guirado VM, et al. Prospective randomized study comparing clinical, functional, and aesthetic results of minipterional and classic pterional craniotomies. J Neurosurg. 2015;122:1012–9. doi: 10.3171/2014.11.JNS146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wiedemayer H, Sandalcioglu IE, Wiedemayer H, Stolke D. The supraorbital keyhole approach via an eyebrow incision for resection of tumors around the sella and the anterior skull base. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2004;47:221–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-818526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang J, Oh CW, Kwon OK, Hwang G, Kim T, Moon JU, et al. The usefulness of the frontolateral approach as a minimally invasive corridor for clipping of anterior circulation aneurysm. J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg. 2014;16:235–40. doi: 10.7461/jcen.2014.16.3.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yasargil MG, Antic J, Laciga R, Jain KK, Hodosh RM, Smith RD. Microsurgical pterional approach to aneurysms of the basilar bifurcation. Surg Neurol. 1976;6:83–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Youssef AS, Ahmadian A, Ramos E, Vale F, van Loveren HR. Combined subgaleal/myocutaneous technique for temporalis muscle dissection. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2012;73:387–93. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Youssef AS, Willard L, Downes A, Olivera R, Hall K, Agazzi S, et al. The frontotemporal-orbitozygomatic approach: Reconstructive technique and outcome. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2012;154:1275–83. doi: 10.1007/s00701-012-1370-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu LB, Huang Z, Ren ZG, Shao JS, Zhang Y, Wang R, et al. Supraorbital keyhole versus pterional craniotomies for ruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysms: A propensity score-matched analysis. Neurosurg Rev. 2018;43:547–54. doi: 10.1007/s10143-018-1053-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]