Abstract

Although the adhesive and cohesive nature of mussel byssal proteins have long served to inspire the design of materials embodying these properties, their characteristic amino acid compositions suggest that they might also serve to inspire an unrelated material function not yet associated with this class of protein. Herein, we demonstrate that a peptide derived from mussel foot protein-5, a key protein in mussel adhesion, displays antibacterial properties, a yet unreported activity. This cryptic function served as inspiration for the design of a new class of peptide-based antibacterial adhesive hydrogels prepared via self-assembly that are active against drug-resistant gram-positive bacteria. Gels exert two mechanisms of action, surface-contact membrane disruption and oxidative killing affected by material-produced H2O2. Detailed studies relating amino acid composition and sequence to material mechanical adhesion/cohesion and antibacterial activity afforded the MIKA2 adhesive gel, a material with superior activity that was shown to inhibit colonization of titanium implants in mice.

Keywords: Antibacterial, Bioinspired, Hydrogels, Peptides, Self-Assembly

Graphical Abstract

In addition to its role in wet adhesion, we discovered that a peptide (Mfp-529–47) derived from the foot pad of mussels exhibits cryptic antibacterial activity. This discovery inspired the design of antibacterial adhesive hydrogels that kill bacteria by two mechanisms: surface-contact membrane disruption and oxidative killing. The lead material, MIKA2, inhibits bacterial colonization on titanium implants in mice.

Introduction

Nature continues to inspire the development of highly functional new materials having intriguing properties. For instance, the mechanism by which the Nepenthes pitcher plant traps its insect prey inspired the design of slippery, self-healing liquid-infused porous surfaces1. Melanin, pigments responsible for a host of functions in humans inspired the design of polymeric peptide pigments2, and nacre from mollusk shells inspired the design of impact-resistant transparent materials3. Over the last several decades, the remarkable adhesive properties of marine mussels have inspired the design of many synthetic underwater adhesives4. Close inspection of the molecular machinery responsible for mussel adhesion suggests an additional cryptic function that can be exploited in materials design.

Mussels can strongly attach to any organic or inorganic surface in a wet, saline environment, by secreting several byssal proteins that form an adhesive plaque on the surface (Figure 1A). The mussel foot protein-5 (Mfp-5), an interfacial protein distributed along the byssus-substrate interface, is known to be strongly adhesive4,5. The primary sequence of Mfp-5 contains a high content of both lysine as well as non-coded 3,4 dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine (DOPA) amino acids5,6. It is well known that the reduced catechol form of DOPA is mainly responsible for surface adhesion by participating in various physical interactions with substrates including metal complexation, π–π stacking and hydrogen bonding4,6–10. Lysine can play a synergistic role in adhesion, for example, by evicting hydrated cations from mineral surfaces to provide dry patches for DOPA binding8. The oxidized quinone form of DOPA plays an important role in material cohesion undergoing free-radical aryl-aryl couplings and Schiff-base as well as Michael-type reactions with nucleophilic residues such as lysine11. Although, the adhesive and cohesive nature of mussel proteins like Mfp-5 have long served to inspire the design of materials embodying these properties4,12–16, their characteristic amino acid compositions suggest that they might also serve to inspire an unrelated material function not yet associated with this class of mussel protein.

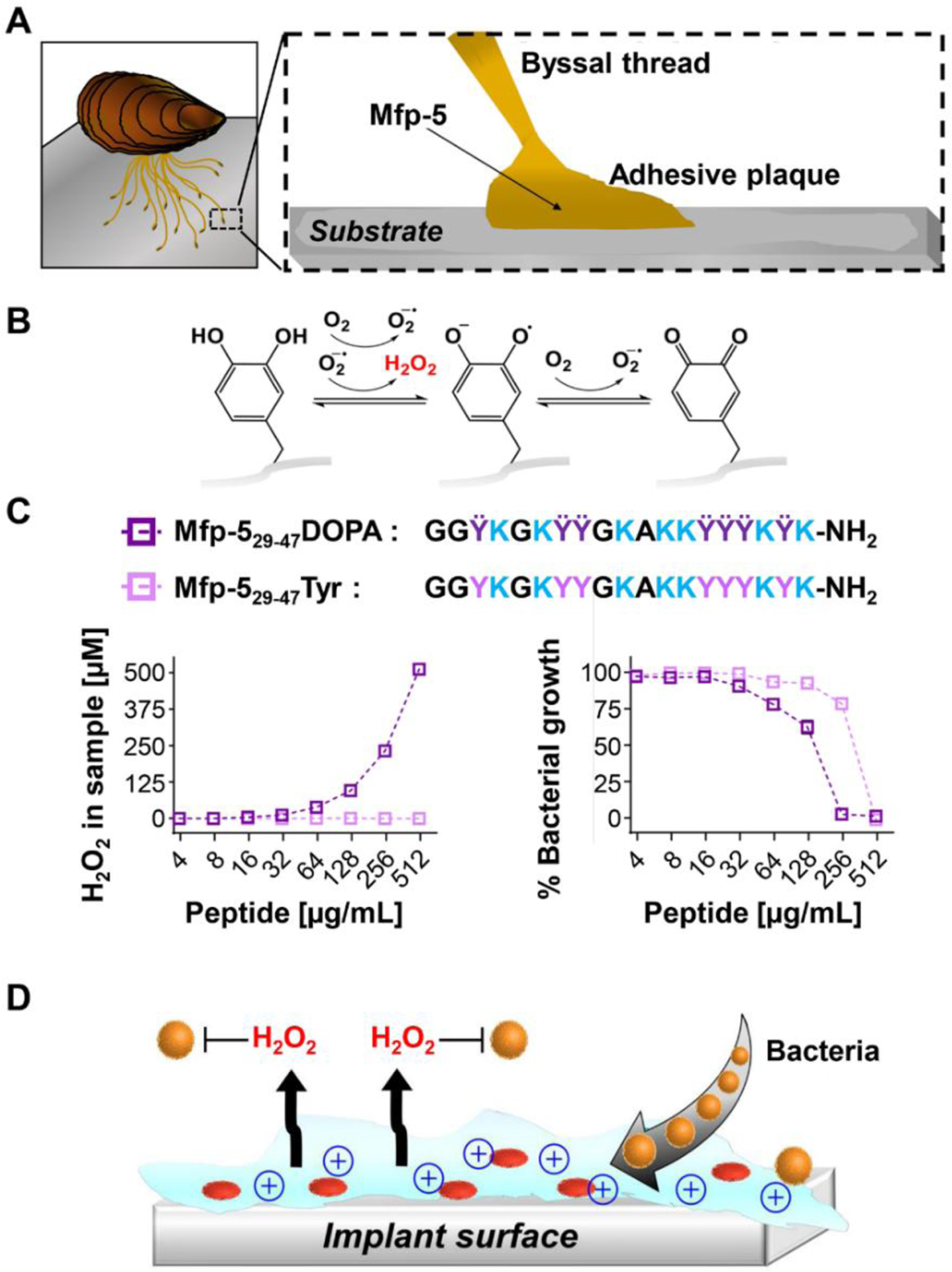

Figure 1. Mussel-derived peptide displays antibacterial activity.

A. An illustration of marine mussel byssus-mediated adhesion to a substrate. Mussel foot protein-5 (Mfp-5), distributed along the adhesive-substrate interface, contains a high content of both lysine and DOPA residues. B. DOPA auto-oxidation generates hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), a known antibacterial agent. C. The sequence of a lysine- and DOPA-rich synthetic peptide derived from Mfp-5 (Mfp-529–47DOPA) and its tyrosine control (Mfp-529–47Tyr). Left panel shows H2O2 generated by each peptide as a function of peptide concentration at 37°C, pH 7.4. Right panel shows percentage of bacterial growth versus peptide concentration, from which the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of the peptides against MRSA bacteria are calculated. All data represent an average of three technical repeats, error bars represent standard deviation and are smaller than the symbols. D. Scheme of a bioinspired antibacterial adhesive gel coating that kills bacteria by two distinctive mechanisms: via a direct contact mechanism between the polycationic gel and the bacterial cell and by DOPA-mediated production of H2O2.

The high lysine content of Mfp-5 is reminiscent of the high occurrence of this residue in antimicrobial peptides, which impart their action by disrupting bacterial membranes17,18. Further, catechols, including DOPA, have been reported to undergo auto-oxidation to produce hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), a potent antibacterial agent (Figure 1B)11,19–22. Thus, the interplay of DOPA and lysine, normally ascribed to mussel adhesion and cohesion, might also affect a cryptic function, namely antibacterial activity. Herein, we show that a lysine- and DOPA- rich peptide derived from Mfp-5 can indeed display antibacterial activity and use this discovery as the basis to develop a new class of peptide-based antibacterial adhesive hydrogel. Such materials could be used as a coating or injected locally into the tissue implant site during surgery to prevent implant related infections. Although devices such as orthopedic prosthetics, dental implants and cardiac devices have revolutionized modern medicine, they represent a major risk of infection23. Implant-related infections are an enormous economic burden to the public health system and can lead to severe clinical complications, for example, implant failure, sepsis and in severe cases even death23–25.

Results and discussion

A peptide derived from Mfp-5 produces peroxide and displays antibacterial activity.

To test the hypothesis that lysine and DOPA (Ÿ) residues within Mfp-5 could impart antibacterial activity, we identified an amino acid sequence within the native protein that is particularly rich in these two residues6. We prepared the peptide fragment, denoted Mfp-529–47DOPA, as well as a control peptide, Mfp-529–47Tyr, where all of the DOPA residues were replaced by tyrosine, Figure 1C. This allows one to evaluate the effects of DOPA separate from lysine. All of the peptides studied herein were synthesized by Fmoc-based solid phase peptide synthesis, purified by reverse phase liquid chromatography (LC), and their primary structure characterized by LC-mass spectroscopy, Figure S1–S10. Gratifyingly, Figure 1C (left panel) shows that the parent peptide can indeed produce H2O2 in a manner that is dependent on peptide concentration, reaching values higher than 0.5 mM. In contrast, no H2O2 was produced by the control Mfp-529–47Tyr peptide indicating that DOPA is necessary for the production of the chemical oxidant. We then examined the antibacterial activity of the peptides against a clinically relevant Gram positive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteria strain with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin26 by broth microdilution27. MRSA, a virulent and difficult-to-treat superbug, is one of the leading causes of commensal and community infections28–30. As seen in Figure 1C (right panel) the Mfp-529–47DOPA peptide is active against this strain with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 250 μg/mL, a peptide concentration capable of producing significant amounts of H2O2 after 24 hours (~250 μM, left panel). It is worth noting that upon direct addition of H2O2, MRSA was completely killed at a concentration that is lower than 250 μM (~ 125 μM, Figure S11). This is because in the assay depicted in Figure S11, H2O2 is added at once, as a bolus, and is immediately available to kill. In contrast, the H2O2 production data in Figure 1C (left panel) represents the amount of H2O2 produced by auto-oxidation of the peptide over 24 hours, time in which the bacteria can proliferate. Thus, it takes more peroxide to kill the increased number of bacteria generated during the assay incubation time. Although H2O2 is capable of killing this strain on its own at μM concentrations (Figure S11), it is not the sole mediator of antibacterial activity for this mussel derived peptide. The control peptide void of DOPA is also active, although to a lesser extent (MIC = 500 μg/mL), suggesting that lysine content also contributes to antibacterial activity. Again, positively charged residues such as lysine are essential for the activity of many cationic antimicrobial peptides that disrupt bacterial membranes en-route to lysing the cell17,31. The mechanism of action for the Tyr-containing peptide was investigated by preparing the mirror image peptide DMfp-529–47Tyr, Figure S3. This peptide also showed activity against MRSA (Figure S12) indicating that the mechanism of action is non-stereospecific and likely membrane-lytic in nature. In fact, as shown with model liposomes, the Mfp-529–47Tyr peptide is capable of selectively disrupting negatively charged vesicles that mimic the bacterial cell wall (Figure S13–S15). Although the Mfp-529–47Tyr peptide is less potent than typical antimicrobial peptides, which can have MIC values lower than 10 μg/mL17, its mechanism of action is similar. Minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) values were also obtained for both Mfp-529–47DOPA and Mfp-529–47Tyr peptides via sub-culturing from the MIC assay to determine the amount of peptide needed to completely kill the bacteria (Figure S16). The MBC values for Mfp-529–47DOPA (250 μg/mL) and Mfp-529–47Tyr (500 μg/mL) are consistent with the MIC values, indicating bactericidal activity. As expected, both peptides were also active against a methicillin-susceptible strain of S. aureus, with the DOPA-containing peptide being more potent than Mfp-529–47Tyr (MBC 125 versus 500 μg/mL, respectively, Figure S17). Taken together, the data show that the native Mfp-5-derived peptide displays antibacterial activity both through the DOPA-mediated production of H2O2 and the lytic potential of its the lysine residues. This observed antibacterial activity and the well-known synergistic roles of DOPA and lysine in mussel wet adhesion8,10 allow the design of adhesive materials that can kill bacteria by two distinctive mechanisms (Figure 1D). First, via a direct contact mechanism between the positively charged lysines of the material and the bacterial cell.32,33 Secondly, by DOPA-mediated production of H2O2, which provides chemical-based oxidative killing20,34, targeting planktonic bacteria proximal to the surface of the material.

Design and biophysical characterization of an adhesive antibacterial hydrogel

We aimed to develop an adhesive hydrogel that could be applied by syringe directly to a device as a bulk coating, as well as to the tissue during the implantation procedure, providing a surgeon the greatest flexibility in dictating the regiolocal antibacterial effect of the adhesive with respect to the surgical site. Thus, the gel needs to demonstrate shear-thin/recovery rheological properties to enable its injection, be an adhesive once placed, and able to kill bacteria. One obvious design strategy would be to ligate the Mfp-529–47DOPA peptide to a polymer scaffold having the mechanical properties described above. Although straight-forward, it would be difficult to control the relative display of DOPA and lysine functionality within the material, which might be important in defining its mechanical and antibacterial properties, as well as to establish molecular design principles. Instead, peptide self-assembly was employed to generate fibrillar gels whose peptide building blocks can be used to regiospecifically display high copy numbers of both lysine and DOPA residues along each fibril constituting the gel.

For the basis scaffold, we used a class of peptides designed by our lab that undergo triggered self-assembly to form fibrillar gels. Solid state NMR shows that each fiber of the gel is comprised of peptides that have assembled into a bilayered cross β-structure and have folded into an amphiphilic β-hairpin conformation35, Figure 2A. Each hairpin contains two β-strands connected by a four-residue reverse turn (-VDPPT-). Within the β-strands, amino acid side chains are projected above and below the hairpin’s main chain backbone. Amino acids located on the hairpin’s hydrophobic face are sequestered away from water and are responsible for bilayer formation. Residue side chains on the hairpin’s hydrophilic face are projected into solvent at known locations along a given fibril. Thus, a structure-based approach can be used to design peptides that display DOPA and lysine side chains regiospecifically along the fibers within the gel material.

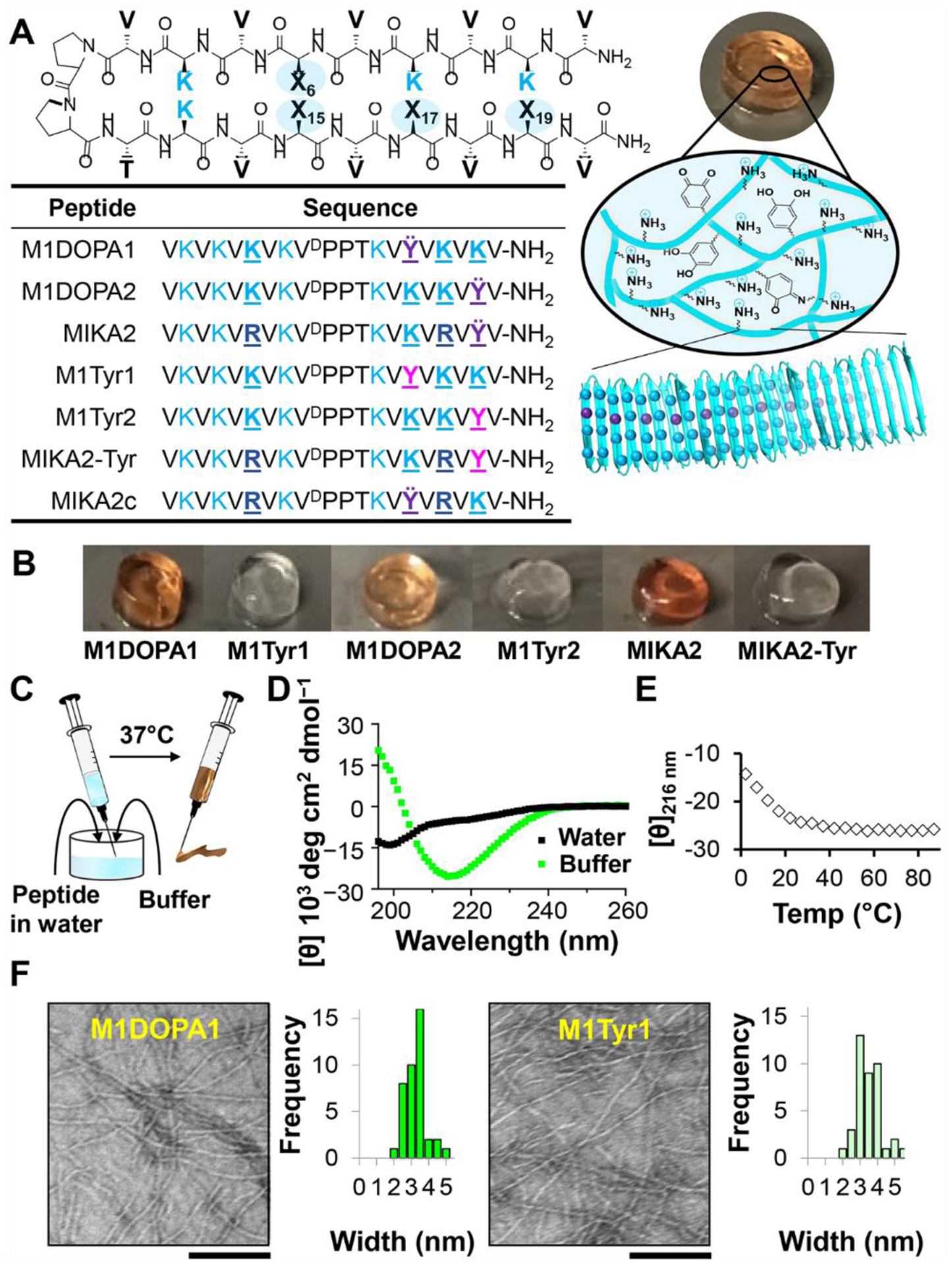

Figure 2. Design of mussel-inspired adhesive gels.

A. Schematic of self-assembling peptide showing sequential positions of DOPA, lysine, arginine and tyrosine residues with corresponding sequences. Peptides assemble into fibrillar networks displaying the side chains of these residues with local fibril regiospecificity as shown for M1DOPA1 B. Images of 0.5wt% gels. C. Gels are prepared by mixing aqueous soluble peptide with buffered saline, drawing into a syringe, and warming to 37°C. Resulting gels can be syringe delivered. D. CD spectra of 0.5wt% M1DOPA1 in water (random coil) and in BTP buffer at 37°C showing a minimum at 216 nm, typical of β-Sheet structure. E. Temperature-dependent CD of M1DOPA1 in buffer monitoring [θ]216. Spectra and temperature-dependence for the other peptides are shown in Figure S19 and S20. F. TEM micrograph of fibrils isolated from 0.5wt% M1DOPA1 or M1Tyr1 gels. Micrographs for the other peptide fibrils are shown in Figure S21. Widths of individual fibrils were determined using ImageJ software, n=40. Scale bar = 100 nm.

Three peptides were designed that all contain the same reverse turn sequence and valine incorporated at each of their hydrophobic β-strand positions. However, peptide M1DOPA1 contains a single DOPA residue on its hydrophilic face at position 15 and lysine residues at each of the remaining positions. When assembled, M1DOPA1 forms fibrils where the DOPA side chains are displayed centrally along both sides of the fibril and entirely surrounded by lysine residues, Figure 2A. The M1DOPA2 peptide contains a single DOPA near the C-terminus (position 19) which places the residue at the edge of the fibril in a more solvent exposed region with fewer surrounding lysine residues. These two peptides help define the positional effects of DOPA and lysine on material cohesion, adhesion, peroxide production and antibacterial activity. The MIKA2 peptide maintains DOPA at position 19 but replaces two of the lysine residues at positions 6 and 17 with arginine. Incorporating arginine into lysine-rich antibacterial peptides is known to increase their potency.17,36–38 Figure S18 shows molecular models outlining the relative positions of the hydrophilic residues for each peptide. Lastly, control peptides were prepared replacing each peptide’s DOPA residue with tyrosine to delineate its effects on material properties.

Figure 2B shows that all the peptides are capable of assembling into self-supporting gels at physiological condition (pH 7.4, 37°C) with the DOPA-containing gels appearing red in color. One of the appealing features of these gels is their facile preparation, Figure 2C. Peptides are first dissolved in water followed by the addition of buffered saline (pH 7.4). The resulting solution is drawn into a syringe which is incubated at 37°C to complete gelation. Gels can be directly administered via syringe injection. Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy shows that the peptides are unstructured when initially dissolved in water, Figure 2D. Inter-peptide charge repulsion due to the protonated lysine/arginine residues keeps the peptides unstructured and soluble. Self-assembly is initiated by adding buffer, which increases the solution pH and ionic strength. However, at room temperature gelation is slow and the solution can be drawn into a syringe. Warming the solution to 37°C hastens peptide assembly by driving the hydrophobic effect, resulting in the formation of a fibrillar network, rich in β-sheet secondary structure, Figure 2D, 2E, S19 and S20. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) shows that the local morphology of fibrils isolated from DOPA- and tyrosine-containing gels are similar having fibril widths of 3–4 nm, which corresponds to the width of a folded β-hairpin peptide, Figure 2F and S21.

Mechanical properties and cytocompatibility of antibacterial adhesive hydrogels

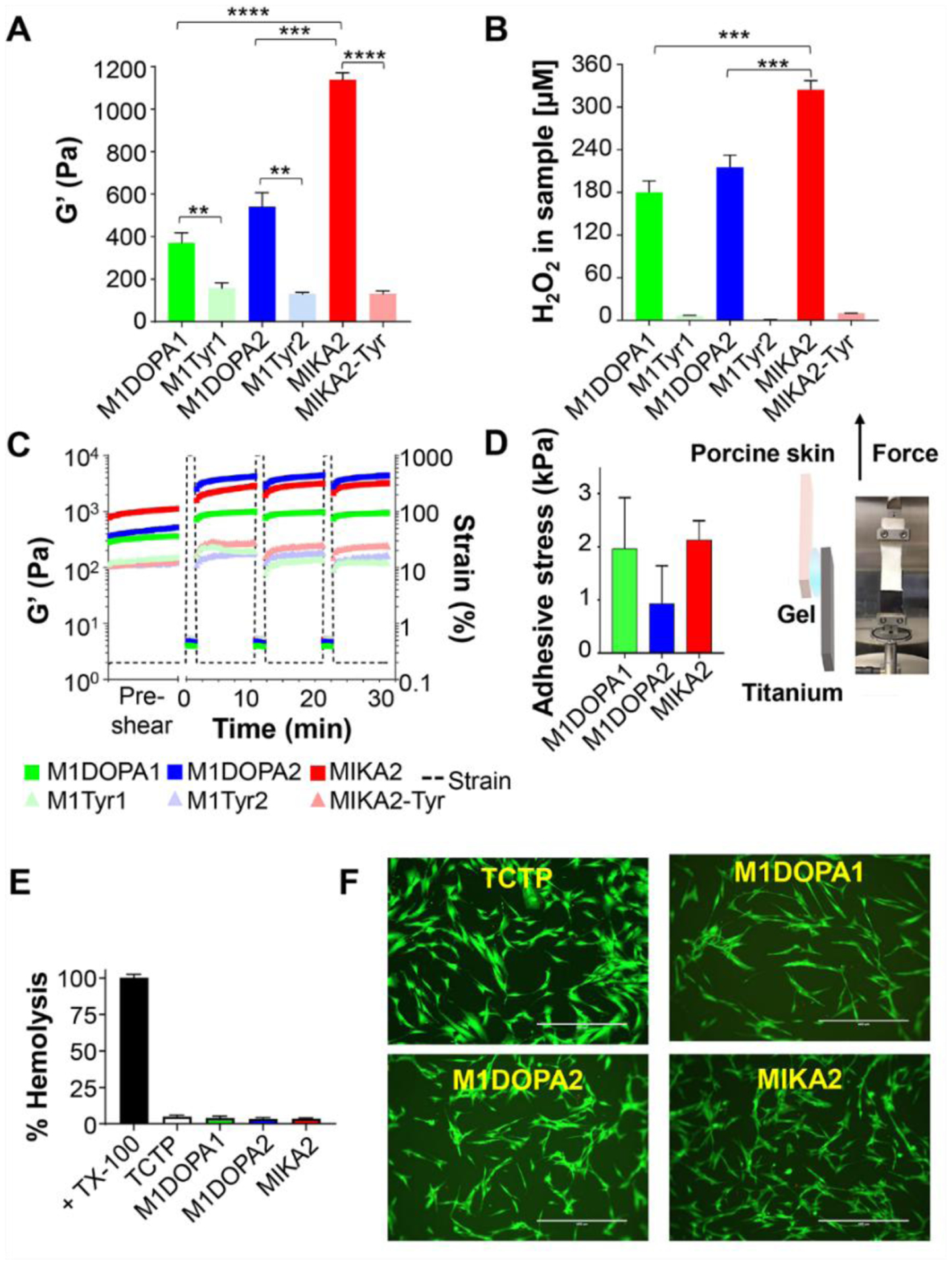

Cohesion and adhesion in mussel byssi are largely mediated by the quinone and catechol forms of DOPA, respectively, along with lysine which plays a role in both.6,7 Materials characterized by stronger cohesive forces exhibit higher mechanical rigidity and the effect of DOPA on the rigidity of our hydrogel system is striking. Figure 3A shows that the average storage modulus (G’) for each of the DOPA-containing hydrogels is at least twice that of its Tyr-control gel (e.g. M1DOPA1 vs. M1Tyr1), and can be up to nine times more rigid (e.g. MIKA2 vs. MIKA2-Tyr). The average storage moduli of the tyrosine control gels (0.5 wt%) were no greater than 158 Pa, whereas the G’ for the DOPA-containing gels range from 370 to more than 1000 Pa (371±47, 542±65 and 1138±33 for M1DOPA1, M1DOPA2 and MIKA2, respectively). Further, the G’ values vary as a function of peptide sequence, indicating that the relative position of DOPA and lysine influences material cohesion. DOPA oxidation leads to the formation of quinone, which can undergo crosslinking reactions with neighboring lysines and other quinones to stiffen the gel network. The data shows that displaying DOPA at the edge of the fibrils, as in the M1DOPA2 and MIKA2 systems, affords stiffer gels. DOPA residues located at an external fibril position could undergo oxidation more readily than DOPA located at an internal position leading to the formation of more quinone, which would be available for subsequent crosslinking. Alternatively, the oxidative potential of the internal and external positions could be similar, but the ability of the resulting quinones to undergo subsequent crosslinking reactions could be different. DOPA oxidation leading to quinone is accompanied by the formation of equimolar H2O2. Figure S22 show changes in the UV spectra for the DOPA-containing systems that accompany catechol oxidation yielding quinone and crosslinked products. Figure 3B shows relative H2O2 production for each of the gels after 24 hours. The relative levels of peroxide production follow the same trend as the G’ values (MIKA2 > M1DOPA2 ≥ M1DOPA1), suggesting that externally located DOPA residues undergo oxidation more readily leading to higher concentrations of quinone. Stoichiometric analysis indicates that the amount of DOPA oxidized to quinone in each of the gels after 24 hours varies from 40 to 80%, depending on peptide sequence. Interestingly, catechol oxidation is known to be pH dependent occurring more slowly under acidic conditions21. The internally located DOPA of M1DOPA1 is surrounded by a high concentration of protonated lysine that might provide an acidic microenvironment disfavoring oxidation. Although the positional dependence of DOPA oxidation is certainly playing a role in determining material cohesion, any positional effects of subsequent quinone crosslinking cannot be ruled out39,40. Lastly, the Tyr-control gels show no H2O2 production as expected. Both the DOPA- and Tyr-containing hydrogels display shear-thin/recovery behavior over multiple cycles (Figure 3C), suggesting they can be delivered by syringe injection. Interestingly, the DOPA-containing gels stiffen in response to the first shear-thin recovery cycle. For example, the storage modulus of the M1DOPA2 gel increases from 542±65 to 5,027 ± 963 Pa, a nine-fold increase. The G’ stays constant after the first recovery cycle. Since this stiffening behavior is not observed with the Tyr-control gels, it’s likely that disrupting the gel network during thinning exposes new opportunities for additional oxidative crosslinking. The adhesive properties of the gels were investigated by performing a lap-shear analysis during uniaxial loading of the materials adhered between porcine skin and titanium, a material commonly used in orthopedic and dental implants. Figure 3D shows that the maximal adhesive stress values vary between 1–2 kPa, which are similar to clinically-used fibrin glue as measured in our lab41 and 2–3 times higher than physiological shear stress of blood flow42. Unlike the cohesive nature of the gels, there is no significant dependence of the adhesion properties on the relative position of DOPA.

Figure 3. Mechanical, chemical, and cyto-characterization of adhesive gels.

A. Rheological characterization of 0.5wt% DOPA- and tyrosine-gels, showing the storage modulus (G’) of the gels. B. H2O2 generated by 0.5wt% gels after 24 hours at 37°C. C. Successive shear-thin/recovery cycles of DOPA- and tyrosine-gels. Time-sweeps were performed within the linear viscoelastic regime (0.2% strain, 6 rad/sec frequency). Shear-thinning was induced at 0, 10, and 20 minutes by applying 1000% strain for 30 seconds (6 rad/sec frequency). Subsequent recovery was allowed by decreasing the strain to 0.2%. D. Lap shear adhesion measurements preformed with DOPA-gels adhered between porcine skin and titanium and the corresponding average maximal adhesive stress values, n=4. Error bar represents standard deviation. E. Hemolytic activity of 0.5wt% gel surfaces. Addition of 1% of Triton X-100 to hRBCs represents 100% hemolysis. All data represent an average of at least three technical repeats, error bar represents standard deviation. F. Cytocompatibility of DOPA-gels towards HDF cells cultured on 0.5wt% peptide gels for 3 days. Live and dead cells were visualized using calcein AM (green) and ethidium homodimer-1 (red) staining, respectively. Scale bar = 400 μm. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.3.8 (GraphPad Software). Differences were calculated using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test with P values being shown. Significance differences of *, **, ***, **** represent P values of P ≤ 0.05, P ≤ 0.01, P ≤ 0.001 and P ≤ 0.0001. Additional statistical analysis can be found in Table S1.

The cytocompatibility of the adhesive gels was assessed with both human red blood cells (hRBCs) and dermal fibroblasts (HDFs). Our gels are designed to kill bacteria via a direct contact mechanism as well as by peroxide-mediated oxidative damage, two mechanisms that can potentially damage mammalian cells. However, Figure 3E shows that the hemolytic potential of the adhesive gels is very low, similar to a tissue-culture treated polystyrene (TCTP) control surface. Thus, the adhesive gel surfaces, though cationic, do not compromised hRBC membranes. Figure 3F shows a live-dead assay where the viability of HDFs added to the gels is assessed after 3 days of 2D culture. Here, live cells fluoresce green and dead cells appear red. Since the assay mainly detects cell death caused by loss of membrane integrity, which may not result from peroxide-mediated killing, cells morphology and spreading were also visualized by phase contrast (Figure S23). Most cells were viable (> 90%, Figure S24), adopting healthy spread-out morphologies similar to the TCTP control surface. Similarly, the control tyrosine-containing gels were also found to be non-hemolytic towards hRBCs as well as cyto-compatible towards HDFs (Figure S25 and S26).

In vitro antibacterial activity of adhesive hydrogels

Initial experiments examined the antibacterial activity of the hydrogels alone as bulk materials. Here, 106 CFU/mL of MRSA were introduced to wells containing 0.5 wt% gels. Viable bacteria were measured after 24 hours by optical density (OD) measurements, where growth on a TCTP surface was defined as 100%. Figure 4A shows that the DOPA-containing gels are extremely potent against MRSA, with no viable bacteria detected. The Tyr-containing control gels were also active but to a lesser extent, characterized by ~ 50 % viability. This data suggests that the lysine/arginine content of the gels imparts some antibacterial activity, which is amplified by the DOPA production of peroxide. We next introduced the gels onto titanium discs forming a coating (~ 3 mm), and in separate experiments introduced MRSA as well as S. epidermidis43, a frequent source of biofilm infection on medical devices24. Bacteria in tryptic soy broth (TSB) were added to wells containing the coated discs, with uncoated discs serving as control. Antibacterial activity was assessed after 24 hours by measuring viable bacteria that had fouled the titanium surface as well as planktonic bacteria in the surrounding solution. Figure 4B shows that the DOPA-containing gels inhibit MRSA growth on the titanium surface affecting more than a 3-log reduction of CFUs, with the MIKA2 gel demonstrating exceptional activity. In contrast, the Tyr-containing gels are largely ineffective. These results were mirrored for the planktonic MRSA, Figure 4C. As a class, the gels were more effective against S. epidermidis. The DOPA-containing gels were very effective at inhibiting surface fouling, and in contrast to their activity towards MRSA, the Tyr-containing gels were also active but to a lesser extent, Figure 4D. Further, both the Tyr- and DOPA-containing gels inhibited planktonic S. epidermidis, Figure 4E. Taken together, the data indicate that both the Tyr- and DOPA-containing gels display antibacterial activity to varying degrees dependent on bacterial type. However, the DOPA-gels are more potent as bulk materials and as barriers to titanium surface fouling with MIKA2 being the most active.

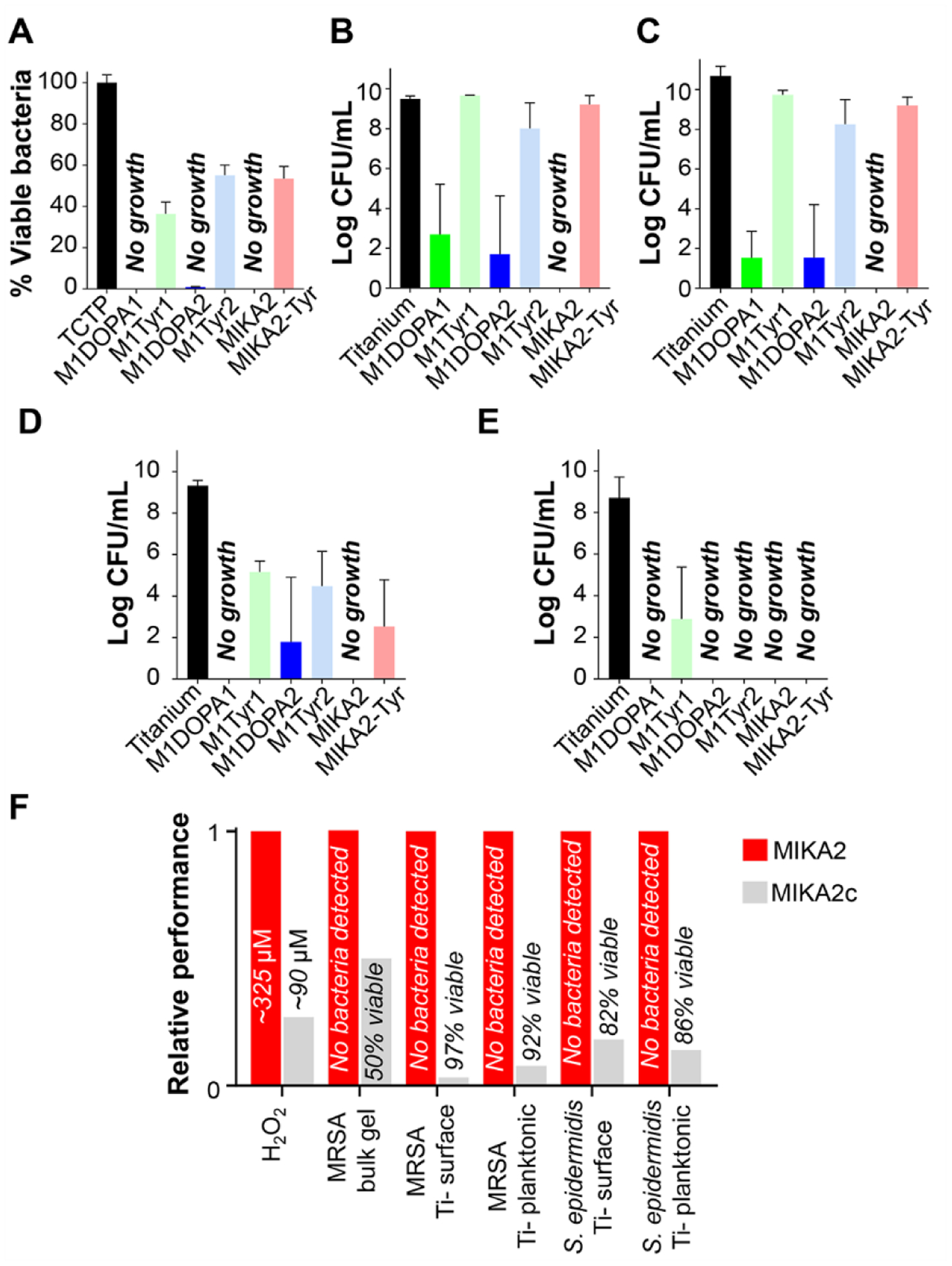

Figure 4. Antibacterial activity of adhesive gels.

A. Activity of bulk gel surfaces challenged with 106 CFU/mL MRSA in TSB for 24 hours at 37°C. Bacterial growth on TCTP represents 100% viable bacteria. B. Proliferation of MRSA isolated from the surface of titanium discs as a function of adhesive coating. C. Proliferation of planktonic MRSA isolated from the solution covering the titanium discs as function of adhesive coating. D and E. Proliferation of S. epidermidis isolated from the surfaces of titanium discs or planktonic bacteria isolated from the solution covering the titanium discs, respectively. F. Relative performance of MIKA2c compared to MIKA2 with respect to peroxide production and antibacterial activity. Statistical analysis can be found in Table S1.

Arginine was included in the sequence of MIKA2 to enhance its antibacterial activity and our data show that the effectiveness of this strategy is context dependent. For example, within the Tyr-containing family of peptide gels, the presence of arginine has little effect (compare MIKA2Tyr with M1Tyr1 and M1Tyr2 in Fig. 4A–E). In contrast, arginine seems to influence the activity of the DOPA-containing gels. Although all the DOPA-containing gels demonstrated potent antibacterial activity, MIKA2 was the only one that contains arginine and was the only gel that killed both MRSA and S. epidermidis to below detection levels in all our assays.

We next studied the positional dependence of DOPA on gel antibacterial activity. An additional control peptide was prepared called MIKA2c. This peptide has identical amino acid composition as MIKA2, but different sequence where the DOPA residue has been moved from position 19 (MIKA2) to position 15 (MIKA2c), Figure 2A. The ramifications of this small change were quite large, Figure 4F. The MIKA2c gel produced significantly less peroxide and thus displayed only moderate antibacterial activity. Interestingly, under the assay conditions used in Figure 4A, we observed no DOPA positional effects on the activity of the all-lysine peptide gels (M1DOPA1 and M1DOPA2). Both effectively killed MRSA. Their antibacterial activity mirrors their ability to produce H2O2 in that there is minimal difference between the amount of H2O2 that each gel produces (Figure 3B), and correspondingly, both gels display similar antibacterial activity. To be able to show any positional effect of DOPA on the antibacterial activity of the lysine-only DOPA-gels, we performed additional antibacterial assays under conditions that reduced the effect of peroxide and accentuated the surface contact mechanism. For that, gels were prepared as before but washed to remove the bolus of peroxide generated in the first 24 hours. Gels were then challenged against a higher number of MRSA bacteria (107 CFU/mL MRSA). As seen in Figure S27, under these conditions, differences can now be seen between these two gels with M1DOPA2 performing better than M1DOPA1. The data also show that MIKA2 performs better than MIKA2c, consistent with the data in Figure 4F. In general, peptide gels having DOPA at position 19 (MIKA2 and M1DOPA2) displayed better antibacterial activity than those peptide gels having DOPA at position 15 (MIKA2c and M1DOPA1). Taken together, the data show that the terminally located DOPA better supports both peroxide-mediated and surface-contact mechanisms of killing. The exact reason why terminally placed DOPA residues facilitate surface-contact killing is not known but could be due to its solvent-accessible location being more capable of interacting with the bacterial cell wall. With respect to design strategy, the data teaches that incorporating both arginine and DOPA into these materials is a beneficial strategy, but dependent on exact sequence.

Exploring the mechanism of antibacterial activity.

The hydrogels are designed to impart two distinct mechanisms of action, namely oxidative killing through the production of peroxide and surface-contact mediated killing where bacteria are lysed when they come in contact with the positively charged surface of the material. We examined the relative contributions of these two mechanisms of action by first studying the effect of material-produced peroxide on bacterial viability in the absence of any surface effects. This was accomplished by treating planktonic MRSA cultured in TSB with the supernatant isolated from gels that had been allowed to produce peroxide for 24 hours. As shown in Figure 5A for the MIKA2 gel, peroxide levels can be modulated by the addition of the peroxide-degrading enzyme catalase, providing a negative control. Figure 5B shows that each of the DOPA-containing gels produce sufficient peroxide to kill all detectable bacteria. Here, bacteria were incubated with supernatant for 24 hours. Separate experiments monitoring bacterial growth curves as a function of gel supernatant show that killing occurs quickly, Figure S28. The addition of catalase eliminates this activity verifying that peroxide is the active species. As expected, supernatants isolated from the Tyr-containing gels are inactive both in the absence and presence of catalase. The maximum production of H2O2 occurs over the first day, and tails off over 3 days, Figure S29. This suggests that when implanted in vivo, the DOPA-gels will provide a burst of H2O2 over several days to thwart initial bacterial attachment and that the surface-mediated killing will be responsible for sustained activity.

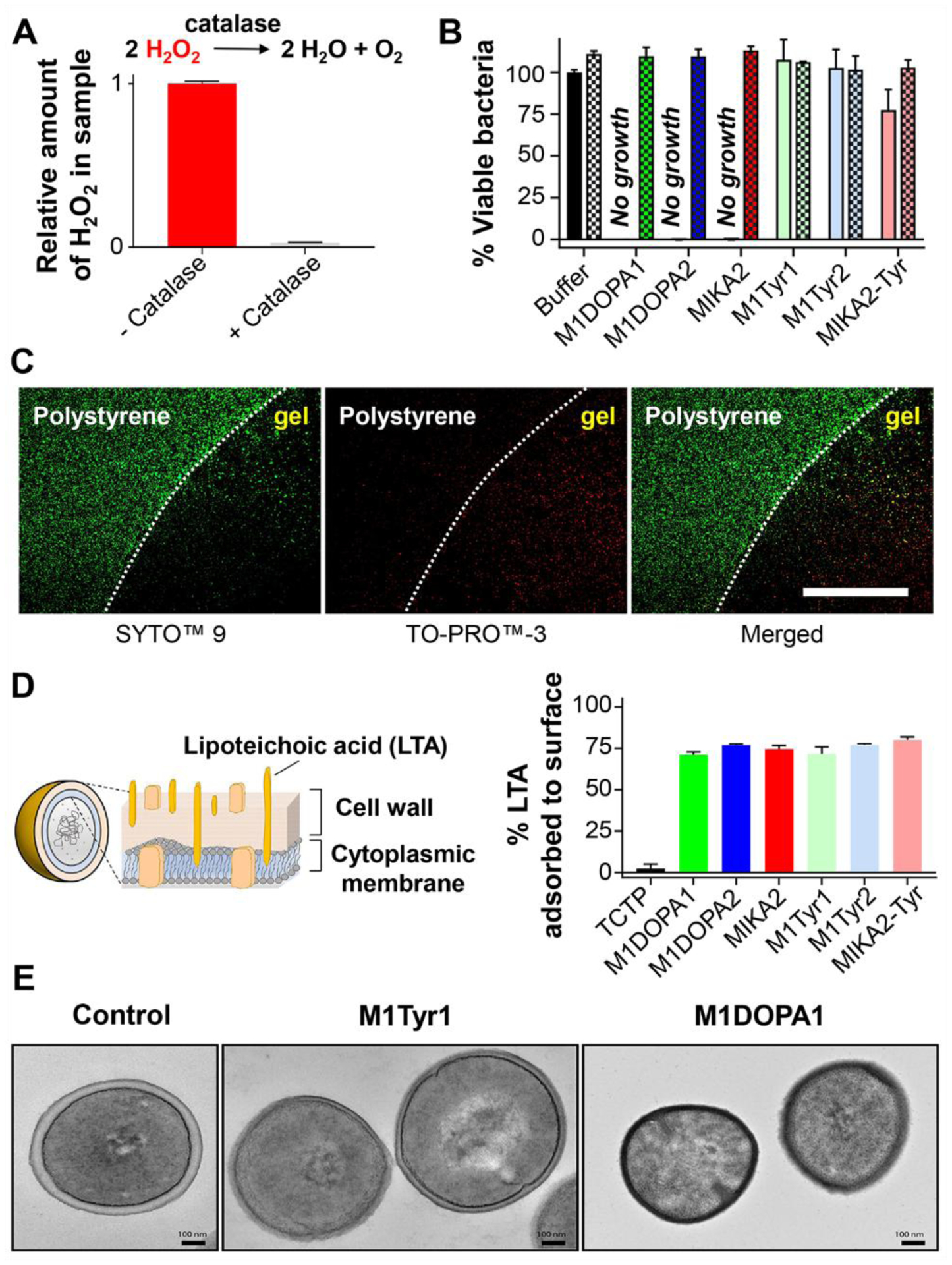

Figure 5. Mechanism of antibacterial activity.

A. Relative amounts of peroxide generated after 24 hours at 37°C from 0.5wt% MIKA2 gel as a function of catalase. B. Supernatant collected above each indicated gel was added to ~106 CFU/mL MRSA with and without catalase (checker pattern versus solid bars, respectively) to assess the contribution of H2O2 to bacterial killing. Percent viable bacteria was measured after 24 hours at 37°C. All data represent an average of at least three technical repeats, error bar represents standard deviation. C. Surface-dependent MRSA killing of MIKA2-Tyr gel. Left panel shows both live and dead bacteria stained (green) with SYTO™ 9. Middle panel shows dead bacteria stained (red) with TO-PRO™-3. Right panel shows the merge image. The dashed white line indicates the boundary between the gel and polystyrene surfaces. Scale bar = 400 μm D. Schematic of Gram-positive bacteria highlighting the lipoteichoic acid (LTA) on its surface and the percent of LTA adsorbed to each gel after 24 hours incubation at 37°C. E. TEM micrographs reveal the differences in the ultrastructure of MRSA grown overnight at 37°C on TCTP (control) or 0.5wt% M1Tyr1 or M1DOPA1 gels. Scale bar = 100 nm. Statistical analysis can be found in Table S1.

Surface-mediated activity was examined using the MIKA2-Tyr gel, which is unable to produce peroxide. Figure 5C shows that cell death can be mediated in a contact-dependent manner. Here, the gel is introduced to a spatially defined portion of a polystyrene surface creating two distinct surfaces (MIKA2-Tyr gel and polystyrene) directly next to each other. MRSA were introduced to the system and viability assessed after 30 min using differential staining. As seen, the bacteria in contact with the polystyrene are viable and the majority of cells on the gel have died with a clear demarcation between the two surfaces. Dead cells are stained with TO-PRO™-3 dye, which only enters cells with compromised membranes, indicated that the material’s surface kills by a mechanism involving membrane destabilization. We next measured the propensity of each of the gel surfaces to bind to lipoteichoic acid (LTA) isolated from S. aureus, a major component of all Gram-positive bacterial cell walls. Figure 5D shows that both the DOPA- and Tyr-containing gels, which are positively charged, bind avidly with anionic LTA, a molecular-level interaction that may represent the first step towards cell death.17,44 Although the data show that peroxide and the material’s surface can act independently to kill bacteria, working together these mechanisms can exert accumulated insult to the cells. Figure 5E and Figure S30 show transmission electron micrographs of MRSA incubated on a TCTP control surface as well as on the surfaces of M1Tyr1 and M1DOPA1 gels. MRSA grown on TCTP are characterized by a well-defined, intact cell wall and inner cytoplasmic membrane. Surface-mediated antibacterial activity (M1Tyr1) results in moderate cell wall damage, especially to the outer wall. Material-generated peroxide further accentuates the damage which penetrates deep into the inner membrane. The data in Figure 4 and 5 also suggest that the DOPA-gels exert their two mechanism with overlapping time regimes. A burst of peroxide is generated in an early time regime (days) capable of killing planktonic bacteria (Figure 5B). Importantly, even after the peroxide has been totally exhausted, the DOPA-gels are still active. For example, gels can still kill MRSA to below detection limits even after removing the bolus of peroxide generated after 24 hours, Figure S31. Further, Figure S32 shows an experiment where catalase is added directly to wells containing each DOPA-gel along with MRSA. The gels are just as active as the Tyr-containing materials presumable now only through the surface-mediated mechanism. Finally, Figure S33 shows that even a 2-month-old gel retains significant activity long after peroxide production has ceased. Although we show here that MRSA is suspectable to surface-mediated killing, the effectiveness of the gel towards other strains may be dependent on a given bacteria’s proclivity towards adhering to surfaces. With respect to the potential of bacteria gaining resistance to the peptide gels, bacteria can engage ROS detoxification enzymes (e.g. catalase) and regulatory mechanisms (e.g. SoxRS, OxyRS, and SOS regulons) that can counteract the damage caused by ROS45,46. However, by employing two general mechanisms of killing, bacteria should be less prone to develop resistance. At any rate, the mechanical and in vitro antibacterial properties suggest that these bioinspired DOPA-gels might be effective coatings to prevent implant fouling in vivo.

In vivo performance of MIKA2 adhesive hydrogel

Although all the DOPA-containing hydrogels showed promising antibacterial properties in vitro, the MIKA2 material was the most effective and was thus studied further along with its control, MIKA2-Tyr. Two mouse models were employed to define the material’s resorption rate after implantation, immune response and efficacy as an antibacterial implant coating. Further, 1.0 wt% gels were used in vivo as opposed to the 0.5 wt % gels used earlier, since peroxide production is dependent on the amount of peptide used to formulate the gel, Figure S34. All animal experiments were approved by the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol 20–049) and performed according to the ACUC and NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

The MIKA2 and control gels were first injected subcutaneously into athymic nude mice and ultrasound imaging was performed to monitor changes in gel volume as a function of time. Figure 6A and B show that the MIKA2 gel gradually degrades with about 40% remaining after one month, the last timepoint monitored. The MIKA2-Tyr control gel was also evaluated and found to degrade more quickly with the bulk of the material resorbed after 3 weeks and only 14% remaining at one month. The basis for the difference in degradation rate is not known but is consistent with MIKA2’s increased mechanical rigidity relative to the control gel, Figure 3A.

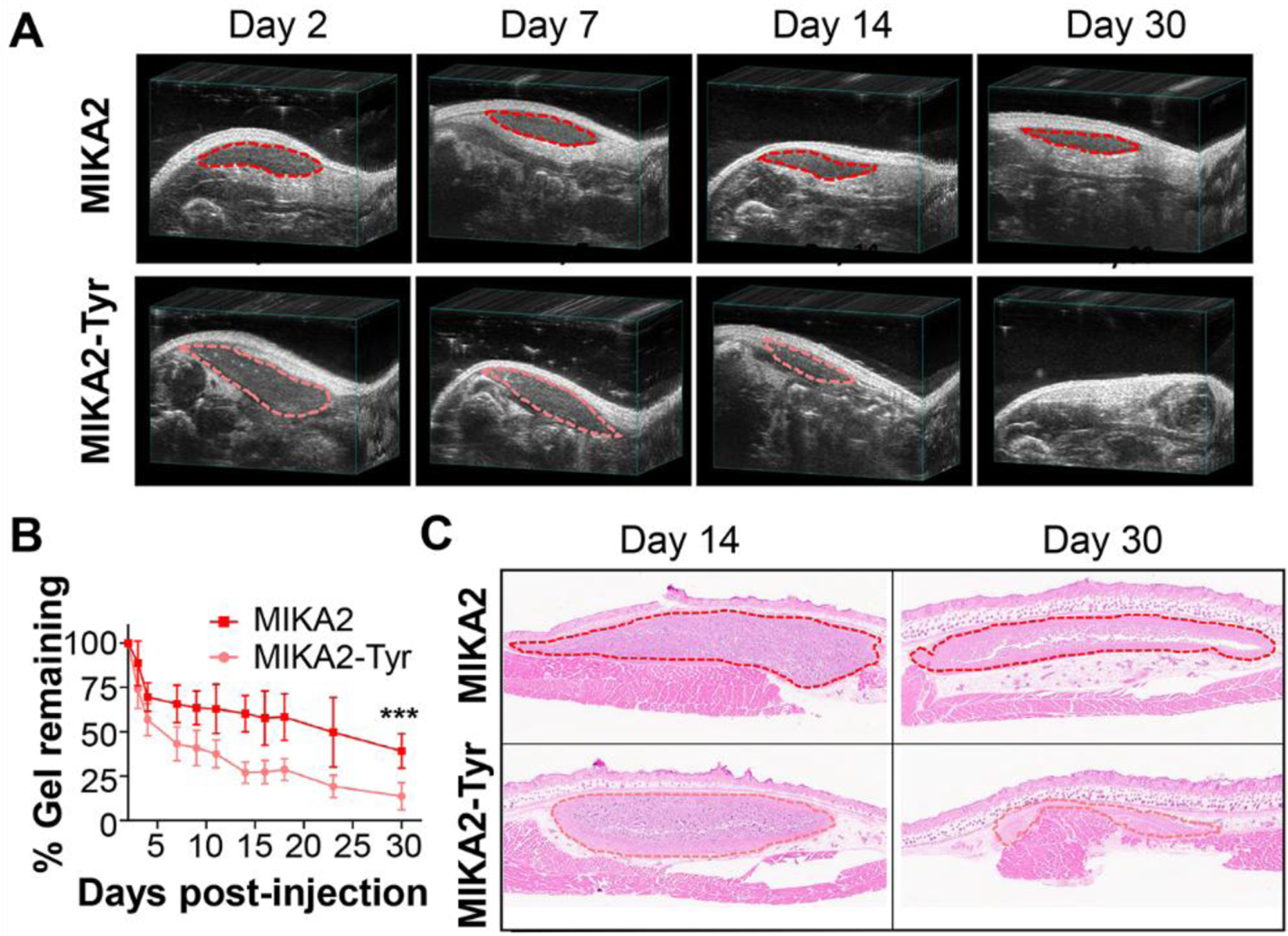

Figure 6. Bioresorption of gels.

A. Bioresorption of subcutaneously injected 1 wt% MIKA2 and MIKA2-Tyr gels, monitored by ultrasound at days 2, 7, 14 and 30 post gel injection. B. Quantitation of echograms taken at different days post gel injection (n = 7). *** indicates statistical significance, p < 0.001. C. H&E staining of tissue sections taken at day 14 and day 30 from athymic nude mice following a single subcutaneous injection of MIKA2 and MIKA2-Tyr gels. The injection sites are outlined by dash lines for reference.

Histological samples were taken from the injection site and surrounding tissue of mice at days 14 and 30 to investigate the immune response to the gels, Figure 6C. High magnification images are provided in Figure S35 and S36. At day 14, the MIKA2 and MIKA2-Tyr gels presented similarly with a small number of neutrophils and a moderate number of macrophages that have infiltrated the gels. A moderate number of macrophages were observed at the periphery of the gels. The surrounding skin, subcutaneous, and mammary tissues appeared normal. At day 30, both gels again had similar appearances now with more macrophages at the periphery of the gels and few neutrophils. Pieces of gel could be seen within some large macrophages having phagocytosed the materials. No foreign body giant cells nor fibrosis of any of the gels was observed. In one of the MIKA2-Tyr mice, most of the gel had been degraded and replaced with neo-tissue. In sum, these materials induce a mild inflammatory response that resolves with material resorption mediated by macrophage phagocytosis.

Lastly, the antibacterial efficacy of the MIKA2 gel was determined using a mouse model of titanium implant infection. Athymic mice were used to mitigate any lymphocyte response which might confound the effects of the adhesive gel. Incisions were made in the backs of mice and medical grade titanium discs were inserted and placed approximately 1 cm superior to the incision. For Group 1 mice, MIKA2 gel was syringe delivered to coat the disc before its implantation. Gel was also administered locally to the tissue surrounding the implant followed by the addition of 50 μL of 106 CFU/mL of bioluminescent S. aureus bacteria proximal to the disc. This is a large amount of bacteria relative to that which might be encountered clinically during surgery but ensures detectable luminescence. Finally, incisions were closed with surgical staples, Figure 7A. Group 2 received phosphate buffered saline (PBS) instead of gel followed by bacteria. Control Groups 3 and 4 received gel or PBS, respectively, but no bacteria and were used to measure background luminescence for Groups 1 and 2. After surgery, the animals were monitored by bioluminescence imaging performed at 1, 6, 24, 48, 72 and 96 hours to assess bacterial proliferation as a function of time.

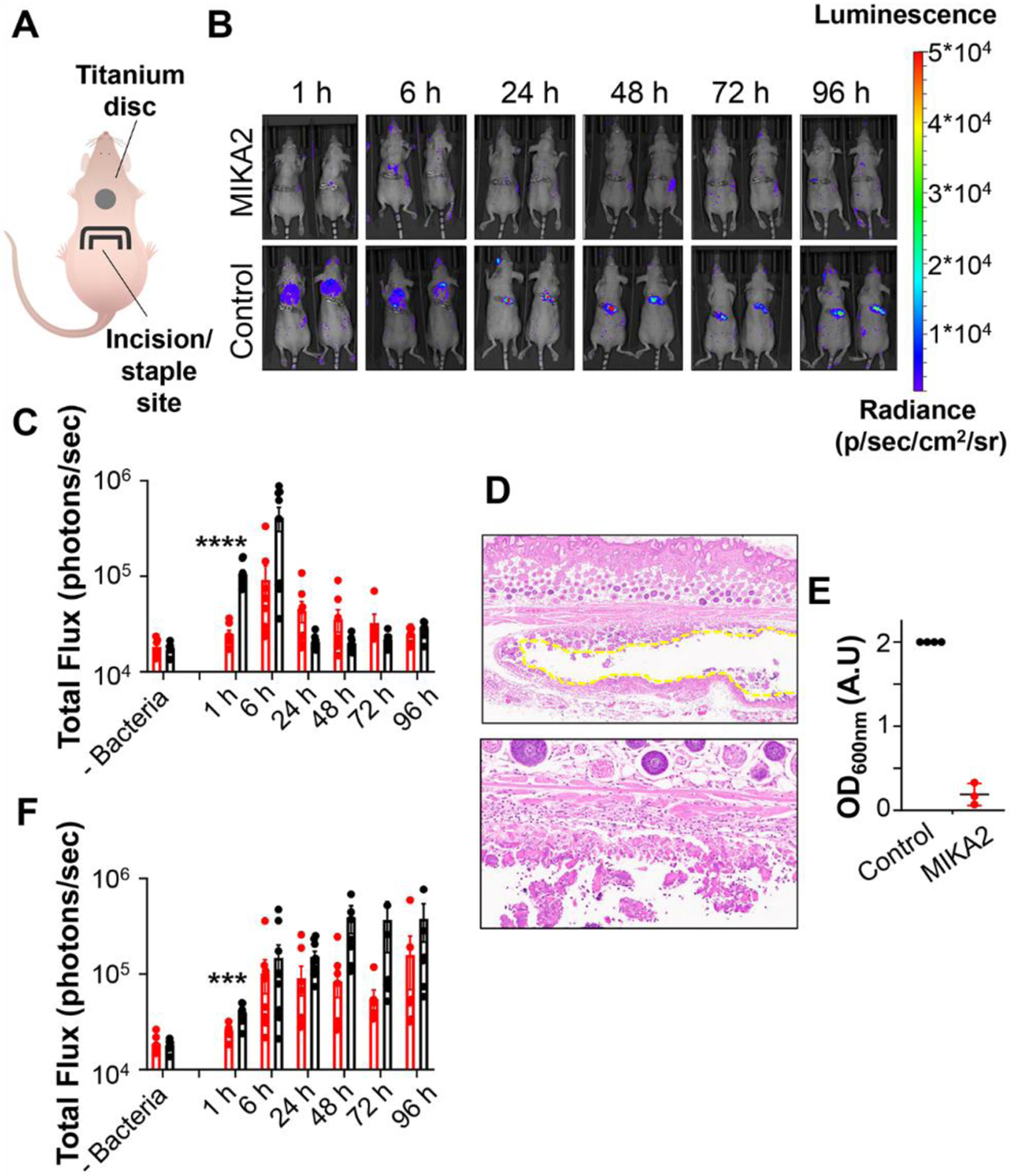

Figure 7. Antibacterial efficacy of gels in vivo.

A. Schematic of titanium disc implant mouse model. A medical grade titanium disc was surgically implanted into a subcutaneous pocket in the shoulder blades of athymic mice through an incision anterior to the disc. MIKA2 gel was syringe delivered to coat the disc prior to implantation and to proximal tissue after implantation. Bioluminescent S. aureus bacteria was introduced proximal to the implanted discs and the incision closed via stapling. For the control, PBS was used instead of adhesive gel. B. Representative bioluminescence images of bacteria in mice as a function of time. C. Quantification of bioluminescence at ROI-disc as a function of time for discs coated with MIKA2 (red) or PBS (black); D. H&E staining of tissue section taken at the end of the experiment from athymic mice containing MIKA2-coated discs. Top panel is 50x magnification. Discs were removed prior to staining leaving a pocket outlined by the dashed line. Bottom panel is 200x magnification showing tissue-implant interface, where the implant pocket is at the bottom of the image and gel fragments can be seen. Hair follicles present as circular structures stained dark purple. E. OD600nm values of cultures resulting from bacteria isolated from disc surfaces retrieved from mice at the end of the experiment, following 24 hours incubation at 37°C. F. Quantification of bioluminescence at ROI-staple as a function of time for discs coated with MIKA2 (red) or PBS (black). In C and F panels data is plotted as individual values with mean ± SEM. *** and **** indicates statistical significance of p < 0.001 and p < 0.0001, respectively.

Figure 7B shows two representative mice from Groups 1 and 2, Figure S37 shows all the mice. The effect of the MIKA2 gel can be seen immediately at the one-hour time point with significant knock down of bacteria compared to the PBS group. Figure 7C quantitates the luminescence observed in a region of interest that includes the disc and tissue directly proximal to the implant (ROI-disc). After the initial knockdown, bacteria show a modest increase in proliferation for the MIKA2 Group at 6 hours, which is ultimately eliminated, reaching background luminescence after about 72 hours. Histological samples were prepared from a sub-set of Group 1 mice isolating tissue from the ROI-disc site at day 3 (Figure S38) and at the end of the experiment, Figure 7D and S39. No bacteria were observed at the disc-tissue interface nor proximal tissue at either time points. As expected, moderate numbers of macrophages are present with some phagocytosing the gel. Tissue isolated from bacteria-free control Groups 3 and 4 were histologically similar except that in Group 4 (+disc; +PBS, −bacteria), the disc was surrounded by a thin layer of admixed fibrin and a few neutrophils, Figure S40 and S41, respectively. Titanium discs isolated from Groups 1 and 2 were also assessed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Figure S42) which showed that no bacteria had fouled implants receiving the MIKA2 gel. In contrast, discs receiving PBS contained a small number of adhered bacteria. Lastly, discs were isolated from an additional subset of Group 1 and 2 mice, washed well to remove any planktonic bacteria and cultured in rich TSB medium to quantitate bacteria that had adhered to the disc surface. Figure 7E shows that all of the discs isolated from Group 2 (PBS) mice grew bacteria as compared to only one disc from the MIKA2 group. Moreover, in the bacteria contaminated MIKA2-coated disc sample, the observed OD600 nm value was only about 0.3 A.U., in comparison to 2 A.U across all contaminated samples of the PBS group.

During the course of the disc implant study, we made an unexpected observation. Namely, bacteria that were introduced proximal to the implanted disc had a propensity to migrate away from the disc towards the surgical staples that were used to close the wound. This is especially evident for the PBS-treated Group 2, Figure 7B. Further, Figure 7C coupled with 7F also shows this migration where after the bacterial population has peaked at 6 hours (Figure 7C, black data), bacteria leave the defined ROI-disc region and migrate towards the incision site. Figure 7F measures the luminescence at the staple site (ROI-staple) as a function of time, showing that a portion of bacteria initially introduced to the disc in the PBS group readily migrate. All of the animals show luminescence at the staple site in Group 2. In contrast, no bacteria were observed after one hour for the MIKA2-treated animals (Group 1) and a third of the mice were void of bacteria at the staple site at extended times with most of the others showing low luminescence compared to Group 2. Taken together, the data show that MIKA2 is an effective coating, inhibiting bacterial colonization at titanium implant surfaces and proximal tissue. Interestingly, the adhesive gel also seems to limit the number of bacteria capable of migrating to other sites of injury.

Conclusion

Marine mussel byssi, long recognized for their superior adhesive qualities, have inspired the development of synthetic glues for decades. We show here that a lysine and DOPA-rich sequence derived from mussel byssal protein (Mfp-529–47), whose amino acid sequence and composition have been historically recognized to endear adhesive properties, also displays antibacterial activity against drug-resistant bacteria. The peptide’s high lysine content is reminiscent of naturally occurring antimicrobial peptides whose mechanism of action involves bacterial membrane perturbation. The peptide’s DOPA residues readily undergo oxidation to produce peroxide, a potent antibacterial oxidant. This discovery inspired the development of a new class of antibacterial adhesive hydrogels formed by lysine- and DOPA-rich self-assembling peptides. Using a self-assembling system allows one to vary the relative sequential positions of these amino acids, which effects the material’s mechanical and biological properties. The mussel-inspired adhesives described here compliment other antibacterial peptide-gels designed from first principles33,44,47 and provoke questions relating to the natural organisms from which they were derived. In addition to using high copy numbers of DOPA and lysine to impart adhesive properties to their byssi, do mussels also use these residues to limit bacterial infiltration into their ecological niche? Beyond the scope of this current study, but an interesting possibility. For example, in our study we derived a peptide from Mfp-5. This protein is located at the byssus-substrate interface and has been shown to remain largely reduced6. Thus, its activity would be largely dependent on a surface-contact based mechanism. Any possible antibacterial activity displayed by Mfp-5 might be important for addressing microbial containments on a surface to which the mussel is trying to adhere, but not microbials from the surrounding sea water. Other byssal proteins rich in DOPA and lysine, such as Mfp-1 which is located at the seawater-byssus interface might be active against sea-borne microbials, Figure S43. The MIKA2 adhesive gel developed here, which contains several arginine residues in addition to lysine and DOPA, was the most potent material, significantly active both in vitro and in vivo as an implant coating. The exact sequence in which MIKA2’s residue are displayed is critical to its activity, underscoring the importance of establishing design principles that can be further refined and exploited to produce materials for targeted clinical applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Center for Cancer Research (CCR), National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The authors acknowledge Dr. Ziqiu Wang (Electron Microscopy Laboratory, Leidos Biomedical Research Inc.) for help with electron microscopy. Dr. Joseph D. Kalen and Lisa Riffle (Small Animal Imaging Program, Laboratory of Animal Sciences Program, Leidos Biomedical Research Inc.) for their help with imaging study planning and ultrasound imaging, respectively. Chelsea Sanders (Animal Research Technical Suppport, Laboratory of Animal Sciences Program, Leidos Biomedical Research Inc.) for performing animal surgeries. Dr. P.H. Nibbering (Leiden University Medical Center, Netherlands) for providing TAN discs for the in vitro antibacterial studies.

References

- 1.Wong TS et al. Bioinspired self-repairing slippery surfaces with pressure-stable omniphobicity. Nature 477, 443–447, doi: 10.1038/nature10447 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lampel A et al. Polymeric peptide pigments with sequence-encoded properties. Science 356, 1064–1068, doi: 10.1126/science.aal5005 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yin Z, Hannard F & Barthelat F Impact-resistant nacre-like transparent materials. Science 364, 1260–1263, doi: 10.1126/science.aaw8988 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee BP, Messersmith PB, Israelachvili JN & Waite JH Mussel-Inspired Adhesives and Coatings. Annu Rev Mater Res 41, 99–132, doi: 10.1146/annurev-matsci-062910-100429 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danner EW, Kan Y, Hammer MU, Israelachvili JN & Waite JH Adhesion of mussel foot protein Mefp-5 to mica: an underwater superglue. Biochemistry 51, 6511–6518, doi: 10.1021/bi3002538 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waite JH Mussel adhesion - essential footwork. J Exp Biol 220, 517–530, doi: 10.1242/jeb.134056 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu ME, Hwang JY & Deming TJ Role of L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine in mussel adhesive proteins. J Am Chem Soc 121, 5825–5826, doi:DOI 10.1021/ja990469y (1999). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maier GP, Rapp MV, Waite JH, Israelachvili JN & Butler A Adaptive synergy between catechol and lysine promotes wet adhesion by surface salt displacement. Science 349, 628–632, doi: 10.1126/science.aab0556 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee H, Dellatore SM, Miller WM & Messersmith PB Mussel-inspired surface chemistry for multifunctional coatings. Science 318, 426–430, doi: 10.1126/science.1147241 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y et al. Molecular design principles of Lysine-DOPA wet adhesion. Nat Commun 11, 3895, doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17597-4 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang J, Cohen Stuart MA & Kamperman M Jack of all trades: versatile catechol crosslinking mechanisms. Chem Soc Rev 43, 8271–8298, doi: 10.1039/c4cs00185k (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee H, Lee BP & Messersmith PB A reversible wet/dry adhesive inspired by mussels and geckos. Nature 448, 338–341, doi: 10.1038/nature05968 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee H, Dellatore SM, Miller WM & Messersmith PB Mussel-inspired surface chemistry for multifunctional coatings. Science 318, 426–430, doi: 10.1126/science.1147241 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofman AH, van Hees IA, Yang J & Kamperman M Bioinspired Underwater Adhesives by Using the Supramolecular Toolbox. Adv Mater 30, doi:ARTN 1704640 10.1002/adma.201704640 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fichman G et al. Seamless metallic coating and surface adhesion of self-assembled bioinspired nanostructures based on di-(3,4-dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine) peptide motif. ACS Nano 8, 7220–7228, doi: 10.1021/nn502240r (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fichman G & Schneider JP Dopamine Self-Polymerization as a Simple and Powerful Tool to Modulate the Viscoelastic Mechanical Properties of Peptide-Based Gels. Molecules 26, doi: 10.3390/molecules26051363 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J et al. Membrane Active Antimicrobial Peptides: Translating Mechanistic Insights to Design. Front Neurosci 11, 73, doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00073 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melo MN, Ferre R & Castanho MARB OPINION Antimicrobial peptides: linking partition, activity and high membrane-bound concentrations. Nat Rev Microbiol 7, 245–250, doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2095 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meng H, Liu Y & Lee BP Model polymer system for investigating the generation of hydrogen peroxide and its biological responses during the crosslinking of mussel adhesive moiety. Acta Biomater 48, 144–156, doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.10.016 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meng H et al. Biomimetic recyclable microgels for on-demand generation of hydrogen peroxide and antipathogenic application. Acta Biomater 83, 109–118, doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.10.037 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mochizuki M, Yamazaki S, Kano K & Ikeda T Kinetic analysis and mechanistic aspects of autoxidation of catechins. Biochim Biophys Acta 1569, 35–44, doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(01)00230-6 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meng H, Li Y, Faust M, Konst S & Lee BP Hydrogen peroxide generation and biocompatibility of hydrogel-bound mussel adhesive moiety. Acta Biomater 17, 160–169, doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.02.002 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arciola CR, Campoccia D & Montanaro L Implant infections: adhesion, biofilm formation and immune evasion. Nat Rev Microbiol 16, 397–409, doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0019-y (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng Y, He L, Asiamah TK & Otto M Colonization of medical devices by staphylococci. Environ Microbiol 20, 3141–3153, doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14129 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ribeiro M, Monteiro FJ & Ferraz MP Infection of orthopedic implants with emphasis on bacterial adhesion process and techniques used in studying bacterial-material interactions. Biomatter 2, 176–194, doi: 10.4161/biom.22905 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rotun SS et al. Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin isolated from a patient with fatal bacteremia. Emerg Infect Dis 5, 147–149, doi: 10.3201/eid0501.990118 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiegand I, Hilpert K & Hancock REW Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nat Protoc 3, 163–175, doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.521 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lakhundi S & Zhang K Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Molecular Characterization, Evolution, and Epidemiology. Clin Microbiol Rev 31, doi: 10.1128/CMR.00020-18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee AS et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nat Rev Dis Primers 4, 18033, doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2018.33 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mookherjee N, Anderson MA, Haagsman HP & Davidson DJ Antimicrobial host defence peptides: functions and clinical potential. Nat Rev Drug Discov 19, 311–332, doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0058-8 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salick DA, Kretsinger JK, Pochan DJ & Schneider JP Inherent antibacterial activity of a peptide-based beta-hairpin hydrogel. J Am Chem Soc 129, 14793–14799, doi: 10.1021/ja076300z (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salick DA, Pochan DJ & Schneider JP Design of an Injectable beta-Hairpin Peptide Hydrogel That Kills Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Adv Mater 21, 4120-+, doi: 10.1002/adma.200900189 (2009). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forooshani PK, Meng H & Lee BP Catechol Redox Reaction: Reactive Oxygen Species Generation, Regulation, and Biomedical Applications. Acs Sym Ser 1252, 179–196 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagy-Smith K, Moore E, Schneider J & Tycko R Molecular structure of monomorphic peptide fibrils within a kinetically trapped hydrogel network. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 9816–9821, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509313112 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chan DI, Prenner EJ & Vogel HJ Tryptophan- and arginine-rich antimicrobial peptides: structures and mechanisms of action. Biochim Biophys Acta 1758, 1184–1202, doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.04.006 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cutrona KJ, Kaufman BA, Figueroa DM & Elmore DE Role of arginine and lysine in the antimicrobial mechanism of histone-derived antimicrobial peptides. FEBS Lett 589, 3915–3920, doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.11.002 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shafer WM, Hubalek F, Huang M & Pohl J Bactericidal activity of a synthetic peptide (CG 117–136) of human lysosomal cathepsin G is dependent on arginine content. Infect Immun 64, 4842–4845, doi:Doi 10.1128/Iai.64.11.4842-4845.1996 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burzio LA & Waite JH Cross-linking in adhesive quinoproteins: studies with model decapeptides. Biochemistry 39, 11147–11153 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fichman G & Schneider JP Utilizing Fremy’s Salt to Increase the Mechanical Rigidity of Supramolecular Peptide-Based Gel Networks. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 8, 594258, doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.594258 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giano MC et al. Injectable bioadhesive hydrogels with innate antibacterial properties. Nat Commun 5, 4095, doi: 10.1038/ncomms5095 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kastrup CJ et al. Painting blood vessels and atherosclerotic plaques with an adhesive drug depot. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 21444–21449, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217972110 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Christensen GD, Simpson WA, Bisno AL & Beachey EH Adherence of slime-producing strains of Staphylococcus epidermidis to smooth surfaces. Infect Immun 37, 318–326 (1982). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu B et al. Supramolecular hydrogels for antimicrobial therapy. Chem Soc Rev 47, 6917–6929, doi: 10.1039/c8cs00128f (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao X & Drlica K Reactive oxygen species and the bacterial response to lethal stress. Curr Opin Microbiol 21, 1–6, doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.06.008 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kashef N & Hamblin MR Can microbial cells develop resistance to oxidative stress in antimicrobial photodynamic inactivation? Drug Resist Updat 31, 31–42, doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2017.07.003 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Veiga AS et al. Arginine-rich self-assembling peptides as potent antibacterial gels. Biomaterials 33, 8907–8916, doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.08.046 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.