Abstract

Over 40% of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) experience difficulty in using speech to meet their daily communication needs. Although augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) can be of benefit, the AAC intervention must support beginning communicators in the early social interactions that provide the foundation for more sophisticated communication skills. An AAC video visual scene display approach uses an AAC app (provided on a tablet computer), including videos based on the interests of the child and infused with AAC supports, to provide opportunities for social interaction and communication between the child and the communication partner. The purpose of this study was to investigate the impact of video visual scene display technology on the communicative turns taken by three preschoolers with ASD and complex communication needs during a high-interest, shared activity (i.e., watching videos). All three participants demonstrated a large increase in the number of communicative turns taken with their partner (Tau-U of 1.00) following the introduction of the video VSD app. The results provide evidence that a video VSD approach may be a promising intervention to increase participation in communication opportunities for young children with ASD.

Keywords: preschoolers, autism spectrum disorder, augmentative and alternative communication, social interaction

Many children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have complex communication needs, meaning speech alone does not meet their daily communication needs (Beukelman & Light, 2020). By age nine, 48% of children with ASD either have no or few spoken words, or speak using words but not sentences (Anderson et al., 2007). In part because of these communication challenges, children with ASD typically do not respond to or initiate social interaction at the same rate as their typically developing peers, and have only limited participation in key educational and social opportunities (Ganz, 2015). Without effective intervention, these individuals will enter adulthood without an effective means of communication, and face poor outcomes in social interaction, employment, and community participation (Light, McNaughton, Beukelman et al., 2019).

Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC)

There is evidence that use of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) technologies, such as the use of low tech AAC displays and high tech AAC speech generating devices, can support the communication of children with ASD and complex communication needs (Ganz, 2015; Tan & Alant, 2018). To date, however, most interventions for children with ASD have emphasized the use of AAC to request desired items (Iacono, Trembath, & Erickson, 2016; Logan, Iacono, & Trembath, 2017; Morin et al., 2018), despite the severe difficulty in social interaction demonstrated by many children with ASD (Ganz, 2015).

Social Communication, ASD, & AAC

Although the fulfillment of needs and wants is an important aspect of communication, participation in social interaction routines (e.g., communicating while reading a book with a partner, or playing a game) is critical to early communication and language development. It is through these social interactions that foundational communication skills such as turn-taking (i.e., recognizing that there is an opportunity to take a communicative turn) and joint attention (i.e., coordinating attention with partner and shared activity) are learned. Young children with ASD often demonstrate limited participation in social interaction routines (Mundy & Sigman, 2015); these critical early communication skills are often delayed or absent (Ganz, 2015; Rowland & Fried-Oken, 2010).

Children with ASD may struggle to communicate within social interaction routines for at least four reasons (Light, McNaughton, & Caron, 2019; Caron, Holyfield, Light, & McNaughton, 2018). First, young children with ASD may not attend to or recognize interaction cues from communication partners (Mundy & Sigman, 2015). Failure to take turns not only results in a missed opportunity to practice the use of a communication skill, but also can lead to communication breakdown and the end of the social interaction if the communication partner does not “repair” the interaction.

Second, although traditional aided AAC systems can be used to engage in social interaction activities (Holyfield, Drager, Kremkow, & Light, 2017), the use of these AAC systems by beginning communicators requires the child to attend to three different elements: the shared activity (e.g., the picture book or game), the communication partner, and the aided AAC system. The challenge for the child to allocate and coordinate attention between these three different elements often leads to communication breakdowns (McCarthy, Broach, & Benigno, 2016), including a failure to recognize and take communicative turns during interactions (Light & Drager, 2007).

Third, the AAC representational system (e.g., the symbols used) may pose another barrier to communication. For example, there is research evidence that beginning communicators struggle to learn the decontextualized images commonly used in aided AAC systems, and that the vocabulary representations provided by many picture symbol systems may be a poor match for how children conceptualize the target word (Drager et al., 2004; Light & McNaughton, 2012; McCarthy, Benigno, Broach, Boster, & Wright, 2018).

Finally, the AAC system may lack personally relevant vocabulary to promote social interaction. Often AAC systems for beginning communicators offer vocabulary concepts focusing on the expression of wants and needs and only a small number of vocabulary concepts focusing on motivating and relevant messages for the person relying on AAC (Beukelman & Light, 2020; Iacono et al., 2016; Logan et al., 2017). In contrast, Laubscher and Light (2020) suggested that AAC systems should support children in learning a wide variety of vocabulary concepts, driven (as in typical language development) by the interests of the child. A reliance on generic vocabulary may fail to assist children with complex communication needs in communicating about their specific areas of interest, thus impacting the child’s motivation to communicate.

Visual Scene Display Technology

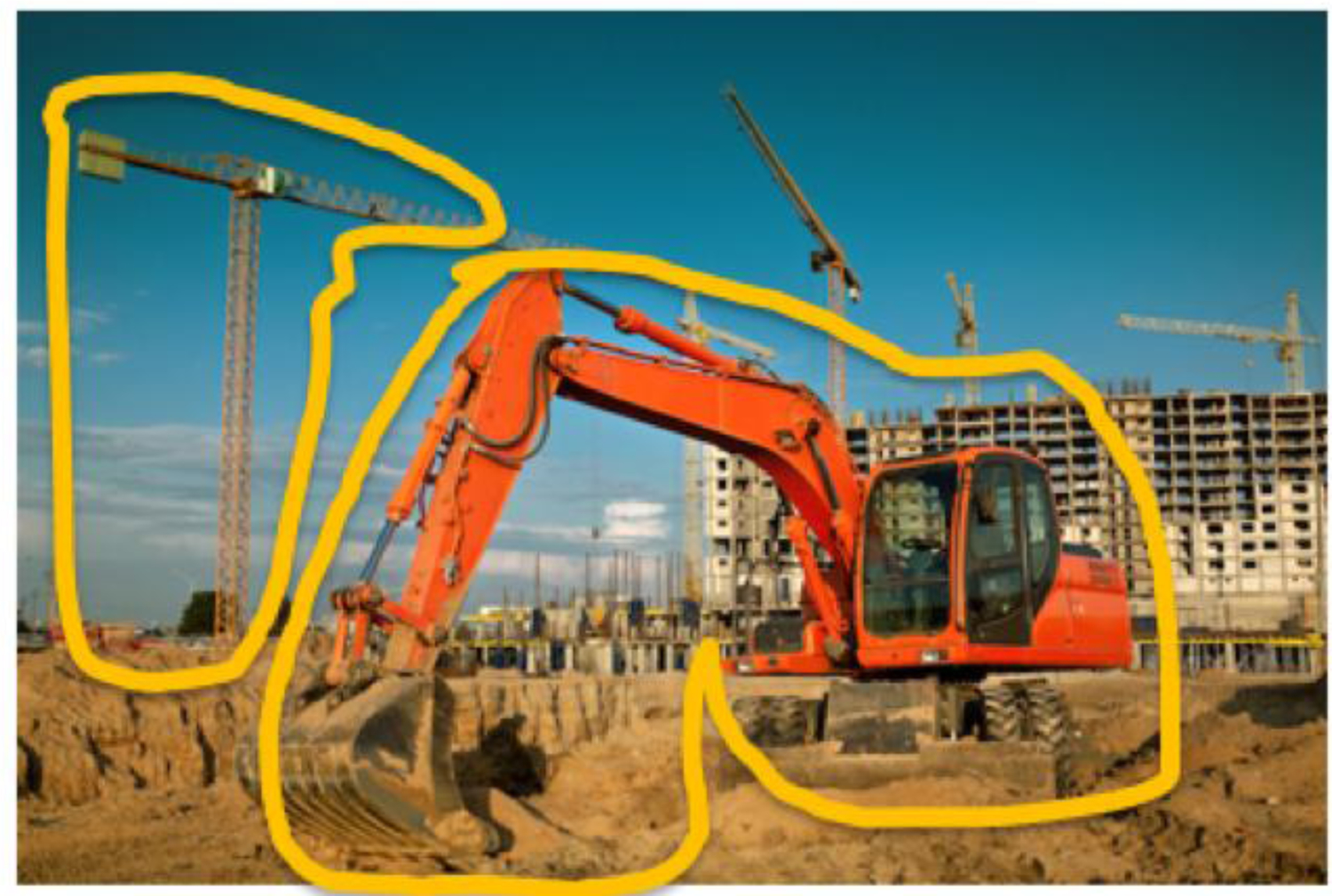

As an alternative to traditional AAC approaches with beginning communicators, the use of visual scene displays (VSDs) has been suggested (Light & McNaughton, 2012). In a VSD approach, images (typically photos) of a meaningful event on a tablet computer are programmed with vocabulary hotspots; when touched, the hotspot produces speech output. Figure 1 shows an example of a VSD using an image of a construction site.

Figure 1.

Example of visual scene display (VSD) with hotspots for Crane and Digger.

The video in the VSD app shows a clip of the construction vehicles digging and moving at the construction site. When the clip pauses, the still image (VSD) with hotspots appears. After hotspot activation, (e.g. the child touches the image of the crane), and speech output (i.e., the spoken word crane), the viewer can press play to continue the video or take additional communication turns using the VSD to share messages.

The use of VSDs has been observed to result in positive changes in both the number of turns taken and the number of different vocabulary items used by children and adults with developmental disabilities during social interaction routines (Holyfield, Caron, Drager, & Light, 2019; Drager et al., 2019). The contextual support provided by the photographic image preserves the functional and proportional relationships experienced in society (Light et al., 2019), and appears to play an important role in supporting the effective use of the AAC system (Caron et al., 2018).

Video VSD Technology

As an extension of a VSD approach, Light, McNaughton, and Jakobs (2014) proposed the use of video visual scene displays (video VSDs). In a video VSD intervention, the communication partner captures videos of preferred activities, including authentic real-life experiences (e.g., the child at a birthday party) or interests (e.g., a YouTube video of a construction site); pauses the video at key junctures to automatically create a VSD (Figure 1); and adds vocabulary as hotspots (with speech and/or text output when activated) to support communication (Light, McNaughton, & Caron, 2019). As Light et al. (2014) hypothesized,

VSDs embedded within a video will be even more effective at facilitating participation and communication than static photo VSDs because video VSDs capture both the spatial and temporal contexts of activities and communication opportunities, thereby preserving the dynamic relationships and engagement cues found in real world interactions…Automatic pausing of the video at key segues in the event marks the appropriate opportunity for participation and communication, and provides the necessary vocabulary within the VSD for the individual who uses AAC to fulfill the communication demands at that point.

Video VSDs to Support Children with ASD

A video VSD approach not only provides strong contextual support for communication – it also allows the use of preferred videos for the child with ASD. Children with ASD engage with electronic screen media, including videos, more often than all other leisure activities (Mazurek & Wenstrup, 2013). In fact, over 30% of children with a diagnosis of severe ASD spend more than four hours per day watching television or videos (Menear & Ernest, 2020), typically by themselves (Shane & Albert, 2008). The use of video VSDs introduces communication and social interaction into what is typically a solitary activity for the child.

To date, a series of studies have examined the impact of a video VSD approach on social interaction and communication. Caron et al. (2020) investigated the use of video VSDs as a means to increase social interaction and communication for five school-age children and adolescents (aged 10–18 yrs. old) with moderate-to-severe ASD and limited speech. The video VSD intervention, implemented using preferred videos of the participants, resulted in increases in communicative turns for all participants (Tau-U of .93–1.00). Caron, Holyfield, Light, and McNaughton (2018) also reported an increase in the number of communicative turns (Tau-U of 1) taken by a 9-year old child with ASD following the introduction of a video VSD intervention. The videos used were captured from the child’s daily experiences (e.g., riding a bike). More recently, Babb, McNaughton, Light, and Caron (2020) described the use of a video VSD approach to assist four adolescents with ASD in interacting with peers while watching videos of preferred activities. Following the introduction of the video VSDs, all four participants demonstrated an increase in communicative turns (Tau-U of 1.0).

Goals of the Present Study

To date, the use of a video VSD approach to support social interaction has only been investigated with school-aged children, adolescents, and young adults with ASD or other developmental disabilities. A video VSD approach, however, may be especially appropriate for very young beginning communicators with ASD who demonstrate a limited understanding of interaction routines and symbolic communication. The ability to participate successfully in communicative exchanges develops from early daily experiences in meaningful and motivating activities (Goldman & DeNigris, 2015). These early social experiences shape the way adult and child initiate and maintain shared interests. In a video VSD approach, videos provide a powerful tool to encourage joint attention, while the pauses and communication hotspots provide support for early experiences with turn-taking and vocabulary development (Light, McNaughton, & Caron, 2019). The purpose of this study, therefore, was to investigate the question: What is the effect of AAC video VSD technology with preferred YouTube videos on the frequency of communicative turns taken by young children (aged 3–5) with ASD and complex communication needs?

Method

Research Design

This study used a multiple-probe design (Horner & Baer, 1978) across three participants. The independent variable was the use of the video VSD application while viewing a preferred video on a tablet computer; the dependent variable was the number of communicative turns taken by the child while viewing the video on the tablet.

The participants remained in the baseline condition until there was a stable baseline (with at least 5 baseline probes) for each participant. The independent variable was then introduced to the first participant who demonstrated a stable baseline (Kratochwill et al., 2010). The independent variable was subsequently introduced to the second participant when the first participant demonstrated a treatment effect. A treatment effect was defined as an increase (from the highest number of turns observed at baseline) of at least two communicative turns for two consecutive intervention sessions. A multiple-probe research design was chosen to minimize the boredom and fatigue that may occur with a multiple baseline design (McReynolds & Kearns, 1983) while still ensuring experimental control.

Participants

The study took place at an early childhood education program that provided services to both children with and without disabilities. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Pennsylvania State University’s Office for Research Protections. Informed written consent was obtained from the parents of all participants.

Participants met the following selection criteria: (a) were between the ages of 3;0 and 5;11; (b) had a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder provided by a licensed psychologist; (c) had minimal speech and did not demonstrate speech skills adequate to meet their daily communication needs, as reported by teacher and parent and through researcher observation; (d) were identified by parents as showing high interest in watching shows on television or computer at home; (e) demonstrated the ability to follow simple one-step directions in context (e.g. “sit in your chair”); (f) demonstrated hearing and vision within or corrected to be within normal limits); and (g) lived in homes in which English was the first language.

Three young children with ASD and complex communication needs met the selection criteria and participated in this study. Matthew, Bella, and Noah (all names are pseudonyms) were 3 years 11 months, 4 years 11 months, and 5 years 6 months at the beginning of the study. All three participants received early childhood special education services within specialized classrooms for children with ASD, developmental delays, and other disabilities.

Matthew received a diagnosis of ASD when he was 2 years 3 months old. According to parent report, Matthew spent approximately 3–5 hours a day watching television, or playing games on a computer. Matthew’s teacher reported that he did not use natural speech to communicate, although he did use vocalizations (with appropriate prosody) and facial expressions to indicate when he was happy or angry. Matthew made use of gestures (e.g. pointing at/towards or leading a grown-up to desired activity/item), and a sign approximation for “more”; and he was learning to use the Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS; Frost & Bondy, 2002) to request desired items. According to reports from Matthew’s speech-language pathologist, Matthew was not able to complete standardized receptive or expressive language tasks, and his speech articulation could not be assessed. Matthew’s speech-language pathologist stated that based on observations conducted with the Communication Matrix (Rowland, 2013), Matthew had mastered Level 3 (unconventional communicator) and was identified to be an emerging conventional communicator (Level 4). His total score was 58 (out of a total of 160). Matthew mostly communicated to express his wants and needs.

Bella received a diagnosis of ASD when she was 2 years old. Bella’s parents reported that she spent approximately 3–4 hours a day watching television or playing games on a computer. Bella’s natural speech, as reported by her teacher, was limited to one-word phrases. Bella used natural speech to imitate (echo) what was said to her. Bella also used gestures (e.g., pointing or guiding an adult to a desired item/activity) and imitated sign language (e.g. colors, animals, food, morning circle words) during the day at school. Bella’s speech-language pathologist reported that Bella was not able to complete standardized receptive or expressive language tasks, and her speech articulation could not be assessed. Based on observations by her speech language pathologist, conducted with the Communication Matrix (Rowland, 2013), Bella had mastered Level 3 (unconventional communicator) and was identified to be an emerging conventional communicator (Level 4). Her total score was 56 (out of a total of 160).

Noah received a diagnosis of ASD when he was 2 years 10 months old. According to parent report, Noah spent approximately 3–5 hours a day watching television or playing games on a computer. The methods of communication most commonly used by Noah at the early childhood center included smiling when happy or excited, touching a teacher’s arm or hand to express wants and needs, gestures (e.g., touching item desired, holding adult’s hand and guiding their hand to want/need), and crying/loud vocalizations when frustrated. Noah’s speech-language pathologist reported that he would not participate in tasks designed to assess receptive language, expressive language assessment or speech articulation. The speech-language pathologist completed the Communication Matrix (Rowland, 2013) for Noah, and reported that Noah had mastered Level 2 (intentional communicator) and was identified to be an emerging unconventional communicator (Level 3). His total score was 29 (out of a total of 160).

Materials

A Samsung Pro Tablet, Model SM-T900 (Samsung, https://www.samsung.com) was used in this research study. The researcher developed an individualized set of eight videos for each child to view during the study based on the child’s interests. The eight videos were from television shows identified as favorites by the child’s parents, and edited to have a run time of five minutes per video.

Interactive video VSD application.

The EasyVSD software app (InvoTek, http://www.invotek.org/) was used to program the videos with embedded hotspots; upon hotspot activation, speech output occurred to provide the message programmed for the hotspot.

The video was paused every 30 seconds automatically creating a VSD, so each 5-minute video contained 10 VSDs. The researcher added two to four hotspots to each VSD, depending on the number of salient images in the VSD. To identify hotspots (and in keeping with the types of words children learn early in language development, Fenson et al., 1994), the researcher selected a character or person (e.g. Happy Dog), place (e.g. bathtub), thing (e.g. crane), an action (e.g. vroom), or social word (e.g. hello) in the VSD that could be labeled with one or two words. Each video contained an average of 30 vocabulary items (range = 20 – 40). Some vocabulary items (e.g., character names) were used more than once in a single video. Some vocabulary items also were repeated across videos (e.g., more than one video used the vocabulary item “bulldozer”). In summary, Bella and Matthew were exposed to 240 hotspots (vocabulary items) across eight videos in intervention, while Noah was exposed to 150 hotspots (vocabulary items) across five videos in intervention. Although eight videos had been created for Noah, Noah viewed fewer videos due to time constraints related to program attendance, and the ending of the school program.

Dependent Variable

The primary dependent variable in this study was the number of communicative turns (e.g., Drager at al., 2019; Light, Collier, & Parnes, 1985; Binger & Light, 2007; Therrien & Light, 2018) taken by the child with ASD during interactions around a 5-minute long video with the researcher (or generalization partner). To be coded as a communicative turn, the child’s behavior needed to meet both of the following conditions: (a) the participant needed to use recognizable speech or speech approximations, speech output from the AAC app, or conventional signs (to be coded as recognizable, the speech or sign had to be understood by two raters when viewing the videotape); and (b) the participant needed to attend to the communication partner as demonstrated by eye contact, body orientation, or movement towards the communication partner.

Procedure

The participants in this study met with the researcher two to three times a week. The researcher (first author) was a certified special education teacher with 4 years’ experience in providing early childhood special education instruction to young children with ASD. The generalization partner was also a certified special education teacher, with seven years of experience with children with ASD and a doctoral candidate in special education.

Each of the eight videos was randomly assigned to each session in the baseline, intervention, and generalization phases, with the provision that no single video would be used more than once in a phase unless all other videos had already been viewed. The hotspots and VSDs were not viewable during the baseline phase, the hotspots and VSDs were available during the intervention and generalization conditions.

Baseline.

Each child participated in at least five sessions with the researcher during baseline. During baseline sessions, the child sat in a child-sized chair with the researcher sitting directly in front of the child, on the floor. The researcher held the Samsung tablet within 5 inches of her face (either beside her cheek or under her chin) and within arm’s length of the child. The researcher also wore one earbud with a timer countdown playing continuously during the session to indicate every 30 seconds of video. The videos were played using the video player app on the Samsung tablet (i.e., without EasyVSD technology). Upon every 30-second interval, the researcher pointed to an image within the video (on the screen of the tablet), and stated, “I see a _. What do you see?”. As in past research, this phrase was used consistently to provide a clear opportunity for the child to take a turn (Caron et al., 2020). The researcher then looked at the child and provided an expectant pause for 5 seconds to allow an opportunity for the child to respond. If the child took a communicative turn, the researcher responded with a brief expansion based upon the child’s message. For example, if the child pointed to the image of the bulldozer and said “digger”, the researcher would say, “The digger is noisy.” The video played without pausing, with the researcher pointing and commenting at 30-second intervals.

Intervention.

Intervention followed the same procedures as baseline except that the VSDs with hotspots were available in the video VSD app and appeared every 30 seconds. Upon a VSD appearing within the video (every 30 seconds), the researcher stated “I see a _ (activated hotspot). What do you see?” while activating one hotspot on the screen of the tablet. Following the same procedures as used in baseline, the researcher then looked at the child, and provided an expectant pause of at least 5 seconds to allow for an opportunity for the child to take a communicative turn. If the child did not take a turn, the researcher said, “Let’s watch” and pressed play to continue the video clip. If the child did take a communicative turn, the researcher provided an expansion to comment on the child’s communicative behavior (e.g., child activates “glasses” and researcher comments “The glasses are green”). The researcher waited 5 seconds to allow the child a second opportunity to take a communicative turn. If the child took a turn, the researcher expanded on the child’s message; if the child did not take a turn after 5 seconds, the researcher stated, “Let’s watch” and played the video.

Generalization.

Generalization probes occurred during baseline and intervention sessions to investigate the participants’ use of the video VSD technology with a new communication partner. The generalization partner was trained in the baseline and intervention procedures through role-play scenarios, direct instruction (model, guided practice, independent practice), and use of a visual checklist of procedures provided by the researcher. Before participating in generalization sessions with the children, the generalization partner demonstrated 100% fidelity of implementation of procedures across two role-play scenarios.

Social validity.

At the end of the study, after the intervention was completed, four early childhood special education (ECSE) professionals, (i.e., two specialized classroom teachers, one classroom paraeducator, one occupational therapist who worked daily with the participants), viewed short video clips (1 minute each) of a participant during a baseline session and during an intervention session. The clips were randomly selected from the pool of both baseline and intervention sessions per participant, and played in random order without being labeled. Then, each ECSE professional completed a brief Social Validity questionnaire to record their perceptions of the intervention on the communication of the children with ASD and the perceived acceptability of the intervention within the ECSE setting.

Data Analysis

All sessions were videotaped to ensure both procedural integrity and data reliability. A research assistant (a graduate student in the special education program) was trained to perform both procedural integrity and data coding across all phases of the research study. To calculate procedural integrity, both the researcher and the trained research assistant used an integrity checklist that provided a summary of the steps in each phase of the study to check randomly selected sessions, including 20% of baseline and intervention sessions, and 50% of generalization sessions per participant. The percentage of baseline steps, intervention steps, and generalization steps completed correctly equaled 100%, 97%, and 94% respectively.

To calculate inter-observer agreement for coding of the dependent variable, a point-by-point agreement ratio was used (the number of agreements was divided by the total number of agreements and disagreements and multiplied by 100). Inter-observer agreement averaged 90.8% across all phases of the study, including baseline (average= 100%), intervention (average= 86.4%), and generalization (average=86.1%) sessions.

Dependent variable data were graphed and analyzed visually for trend, level, variability and slope (McReynolds & Kearns, 1983) to determine the effect of the intervention on the number of communicative turns taken by the children with ASD. Data were also analyzed using Tau-U (Lee & Cherney, 2018; Parker, Vannest, Davis, & Sauber, 2011). Tau-U provides a quantitative approach for analyzing single-case experimental design data, and is a measure of data nonoverlap between baseline and intervention phases, not including generalization data. Tau-U effect sizes can be interpreted as follows: weak effects, 0–.65; medium effects, 0.66–0.92; and large effects, 0.93–1.0 (Parker, & Vannest, 2009; Rakap, 2015).

Results

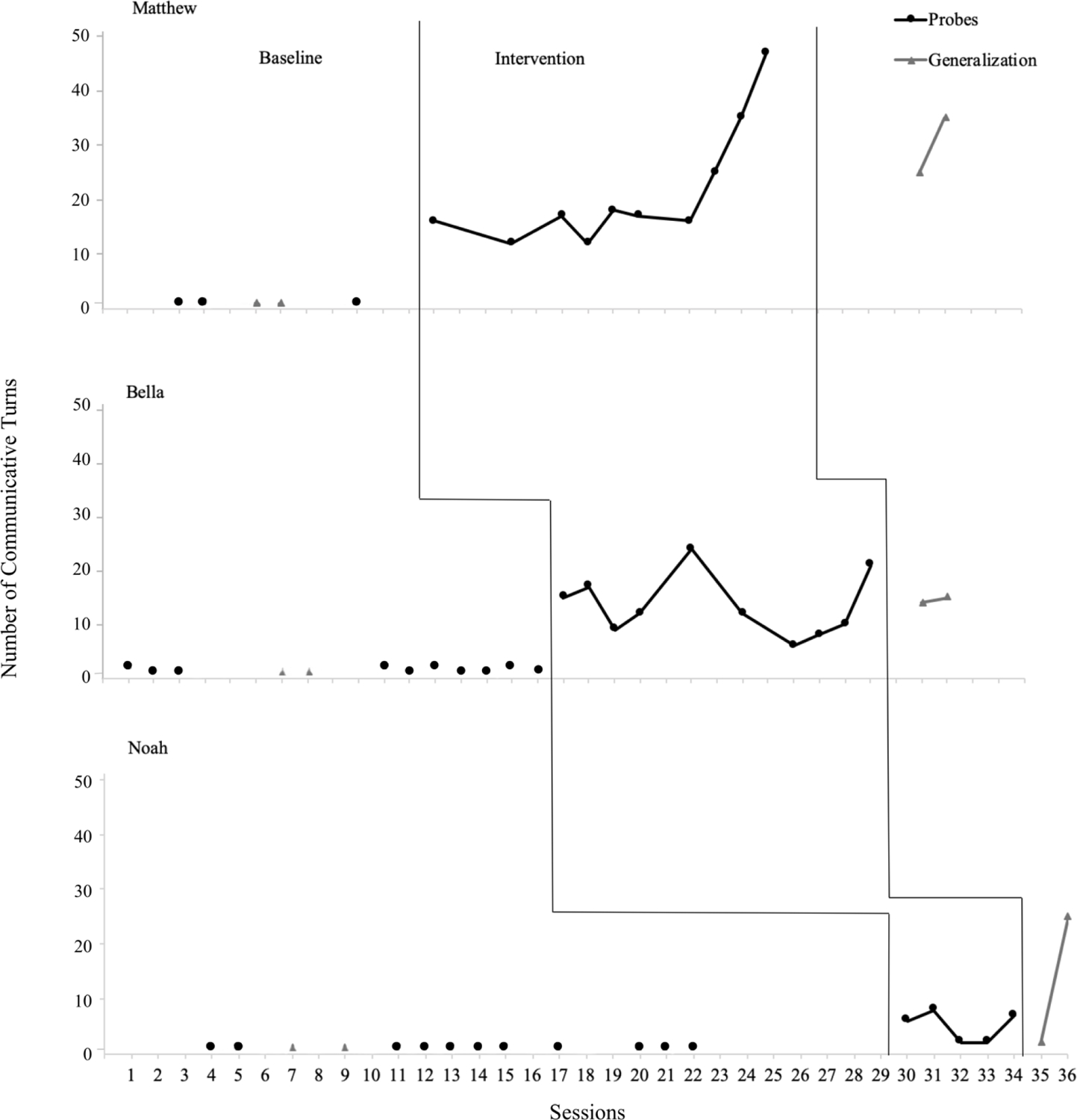

All three participants demonstrated an increase in the number of communicative turns (Tau-U of 1.00 for all three participants, a large effect) taken with the researcher as a result of the use of video VSD technology (Figure 2). During the baseline session, the three participants took very few turns (range = 0–1); in fact, two of the participants took no turns at all. During intervention, all three participants demonstrated an increase (range = 1– 46) in the number of communicative turns taken while viewing a preferred 5-minute video clip with the video VSD technology.

Figure 2.

Number of Communicative Turns Taken by Participants

For all three participants, all intervention data points were above the highest point seen in baseline. Due to time limitations associated with the early childhood special education program, the three children varied in the number of intervention sessions received (range = 5–10). All children participated in two generalization sessions within intervention, and all generalization data points were above the highest level seen in the baseline generalization for all three of the participants.

Matthew

Matthew participated in five baseline sessions, 10 intervention sessions, and a total of four generalization sessions (two baseline and two intervention) over 3 months. Matthew engaged in zero communicative turns during baseline and pre-intervention generalization sessions. Matthew demonstrated a sharp increase in performance in the first intervention session, and all intervention sessions were higher than baseline performance. A second sharp increase was observed in intervention session eight, and Matthew took an average of 34.6 turns (range = 24–46) in his final three sessions. Using Tau-U, a strong intervention effect of 1.0 was calculated for Matthew. A strong intervention effect also was observed for the generalization condition (i.e., a new communication partner): Matthew took zero turns on the two baseline generalization probes, and took 24 and 34 turns (respectively) on the two intervention generalization probes. All of Matthew’s turns (across all intervention sessions) were taken using the video VSD app – he did not make use of any speech or conventional signs in any sessions.

Bella

Bella participated in 10 baseline, 10 intervention, and a total of four generalization sessions (two baseline and two intervention) over a period of 3 months. Bella took zero or one communicative turns during baseline and pre-intervention generalization sessions. Bella demonstrated a sharp increase in performance in the first intervention session. All intervention sessions were higher than baseline performance, although performance was variable. Bella took an average of 12 turns (range = 7–20) in her final three sessions. Using Tau-U, a strong intervention effect of 1.0 was calculated for Bella. A strong intervention effect also was observed for the generalization condition for Bella. She took zero turns on the two baseline generalization probes, and took 13 and 14 turns (respectively) on the two intervention generalization probes. Bella made no use of conventional signs at any time, and her use of speech also was very low in both the baseline and intervention phases (less than one spoken word per session, on average). All other turns (in intervention) were taken using the video VSD app.

Noah

Noah participated in 11 baseline, five intervention, and a total of four generalization sessions (two baseline and two intervention) over a period of four months. Noah took zero communicative turns during both baseline and pre-intervention generalization sessions. Noah demonstrated a sharp increase in performance in the first intervention session. All intervention sessions were higher than baseline, although performance was variable. In his final three intervention sessions, Noah took an average of 2.7 turns (range =1–6). Using Tau-U, a strong intervention effect of 1.0 was calculated for Noah. Noah also demonstrated a strong intervention effect for the generalization condition. He took zero turns on the two generalization probes during baseline, and took 1 and 24 turns (respectively) on the two generalization probes during intervention. All of Noah’s turns (across all intervention sessions) were taken using the video VSD app – he did not make use of any speech or conventional signs in any sessions.

The results for Noah must be interpreted with some caution, as there was a pause of 27 days between the collection of the last point in baseline for Noah, and the beginning of intervention. During this time, Noah was absent from the school program due to a family vacation. In a multiple-probe design, intervention should begin immediately after the collection of the last baseline data point (Horner & Baer, 1978). A decision was made to begin intervention without additional baseline data (i.e., in spite of the pause in data collection) because of Noah’s frequent absences from the program, and a concern that data collection for intervention would not be completed by the end of the school program. It should also be noted that Noah had demonstrated consistently low levels of performance at baseline, with a score of zero for all 13 baseline probes over a 70 day period, providing strong evidence of low levels of social interaction (i.e., no turns) prior to intervention.

Social Validity

The four ECSE professionals (two teachers, an occupational therapist, and a para-educator) who provided information on social validity reported a positive view of the intervention. Three of the four professionals agreed (n=2) or strongly agreed (n=1) with the statement “The intervention could be implemented in the ECSE classroom or natural environment by a teacher/therapist” (one professional neither agreed/nor disagreed with this statement). All four agreed (n=1) or strongly agreed (n=3) with the statement “The activity would be beneficial for other children with autism.” All four strongly agreed with the statement “The child enjoyed participating in the intervention study.” Finally, two professionals agreed, and two professionals strongly agreed with the statement “The child’s communication skills improved as a result of this intervention.”

Discussion

This study adds to the growing research base documenting the positive impact of a video VSD approach on communication outcomes for individuals with complex communication needs. Past research has demonstrated increases in communication for school-age children and young adults with ASD (Babb et al., 2020; Caron et al., 2018, 2020). The current study provides evidence that the use of video VSD technology with very young children with ASD and complex communication needs can produce similar positive results, with strong increases in the number of communication turns (Tau-U of 1.00) seen for all three of the participants. These results are especially promising because young children with ASD frequently spend more than 4 hours per day watching TV or videos (Menear & Ernest, 2020). Video VSDs provide a promising strategy for the development of social interaction and communication skills during what is frequently an isolated activity. The positive results could be due to one or more of the following unique qualities of video VSD technology (Caron et al., 2018; Light, McNaughton, & Caron, 2019).

Implicit Prompts

In typical development, young children learn language concepts within the contexts of their daily interactions during meaningful and motivating activities. Young children with ASD, however, often fail to recognize social cues and miss opportunities to engage in social routines (Mundy & Sigman, 2015). The appearance of a VSD within a video (as in a video VSD approach) provides an implicit prompt to communicate because the motion of the video is interrupted by the appearance of the VSD (i.e., a still image and a pause in the video). The appearance of the highlighted hotspot in the VSD also provides a cue for the child to take a turn, and a tool (i.e., touching the hotspot) by which to do so. By responding to the child’s behavior, the partner can maintain the interaction and help to support the development of joint attention and intentional communication acts (Rowland & Fried-Oken, 2010).

Reduction of Attention Shifting and Communication Demands

Young children with ASD are at risk for delayed development of joint attention, social, and communication skills, making it especially critical to identify AAC supports that do not impose additional attention demands (Light & Drager, 2007). The results of the current study provide evidence that the integration of AAC supports within a preferred video (i.e., video VSD) is effective at supporting communication and social interaction for young children with ASD and complex communication needs. Because the AAC supports are integrated seamlessly into a highly preferred activity (i.e., the video), there is no need for the child to divide attention between the activity and the aided AAC system (Light, McNaughton, & Caron, 2019). As a result, the child can use the communication supports while remaining engaged with the activity and the partner, and can also more easily attend to models of system use (e.g., activation of hotspots) provided by the partner.

The ease of system use may be one explanation for why the great majority of turns for the participants were taken with aided AAC rather than unaided modes such as gestures or speech. The aided AAC (i.e., the video VSD app) had minimal motor demands, as it required only a touch, rather than more challenging physical movements such as gestures or speech approximations. The video VSD app also had limited cognitive demands, as the vocabulary was presented with strong contextual support (i.e., integrated into the shared video activity). In addition to these reduced learning demands, the video VSD app also may have provided greater communication power, as the taking of a turn (by activating a hotspot) produced a clear auditory signal that was easily recognized and responded to by the partner. It is not surprising, therefore, that there was strong uptake of a communication mode that provided a quick and easy method to take turns in interaction. It should be noted, however, there is strong clinical and research evidence that the introduction of aided AAC is often followed by increases in the use of speech, as the child learns new language and motor skills in the context of supported communication interactions (Fäldt et al., 2020; Light, Caron, et al., 2016; Millar, Light, & Schlosser, 2006).

Contextual Support for Vocabulary

Young children often struggle to recognize the abstract symbols used to represent vocabulary in AAC systems (Worah et al., 2015). McCarthy et al. (2018) provides evidence that young children with ASD may benefit from the use of entire scenes (as opposed to isolated images) for the representation of vocabulary. In this study, the contextual support provided by the surrounding video may have assisted the children in recognizing and using the hotspots which appeared in the videos (Light, McNaughton & Caron, 2019), thereby supporting their active participation.

Access to Personally Relevant Vocabulary

Often AAC interventions for beginning communicators focus primarily on teaching requests for objects or activities (e.g. snack items) to the neglect of social closeness and commenting/exchanging information (Ganz, 2015). In addition, many young children with ASD demonstrate limited speech development, and a strong preference for solitary activities, including personally preferred video/media content (Mazurek & Wenstrup, 2013; Shane & Albert, 2008). Video VSD technology serves as an effective context to support social interaction and communication for young children with ASD because of the use of high-interest videos for the child, as well as hotspots that are selected and programmed with vocabulary based on the unique interests of the child. Providing access to communication through motivating vocabulary programmed into hotspots encourages high levels of engagement for watching the video, but also for attending to the communication partner as the partner models the use of hotspot vocabulary within the video.

Clinical Implications

The results described here offer a promising approach to early communication intervention for young children with ASD and other disabilities. Beukelman and Light (2020) described the importance of teaching beginning communicators to take turns, and to demonstrate joint attention (shift attention between the partner and the shared activity), during social interaction. As seen in this study, a video VSD approach provides a motivating shared context for learning and strengthening these early communication skills. The pausing of the video provides an implicit cue to the child to communicate, and the presentation of vocabulary as hotspots in a familiar video scene provides strong contextual support for language learning and use (Light, McNaughton, & Caron, 2019; McCarthy et al., 2018). These supports for the development of early symbolic communication skills can also be integrated into other motivating interaction opportunities, including the use of video VSDs and VSDs to support participation and communication during play with peers (Laubscher, Light, & McNaughton, 2019; Laubscher, Raulston, & Ousley, 2020); action songs (e.g., “The Wheels on the Bus”) and interactive play routines (Beukelman & Light, 2020); and book-reading activities (Therrien & Light, 2018). These activities provide rich opportunities to address key goals for beginning and early symbolic communicators: a wide variety of interaction opportunities throughout the day, and access to a robust vocabulary to support language and cognitive growth (Beukelman & Light, 2020; Laubscher & Light, 2020).

Limitations and Future Research Directions

There were a number of study limitations, including the small number of participants, as well as the limited number of intervention sessions. In addition, the study lacked maintenance data due to time constraints related to the summer session schedule. The overall results of this study suggest that video VSD technology has a positive impact as a communication support for children with ASD, however due to gaps in data collection because of participant attendance and program scheduling, the results should be interpreted with caution. For example, although Noah demonstrated a stable baseline, and took no turns during the collection of baseline data, confidence in the relationship between the intervention (i.e., the introduction of the video VSD) and his change in performance would have been increased if additional baseline data had been collected immediately prior to intervention.

In addition, although the behavior of the participants met the criteria for a “communicative turn” as traditionally defined in the literature (Binger & Light, 2007; Drager et al., 2019; Therrien & Light, 2018), it should be emphasized that these are beginning communicators, and by definition are at the beginning stages of learning to communicate a symbolic message to their communication partner. As is the case with aided AAC use, it is not possible to conclude that every activation of a hotspot represented an intentional effort to communicate a specific concept (Carter & Iacono, 2002; Holyfield, 2019). It is clear, however, that the children were more frequently taking turns in an interaction using clearly recognizable communication signals - this increased use of communicative turns is an important first step to more advanced communication behavior (Ganz & Hong, 2013; Holyfield, 2019).

Finally, future research is needed to explore the impact of the use of video VSD technology within early childhood education program routines and activities, and including ECSE staff and family members (parents, siblings) as communication partners. For example, although there is growing evidence that VSDs can be efficiently created and used in clinical settings (Caron, Light, Davidoff, & Drager, 2017; Holyfield et al., 2019), there is limited information on the creation and use of video VSDs by educational staff and family members. Although this intervention project did take place in an ECSE setting, future research should investigate the use of a video VSD approach over an extended period of time with a larger number of participants, the use of a variety of methods to analyze the interaction, and the creation and use of the video VSD intervention in naturalistic contexts with familiar communication partners. Although the study reported here made use of a video VSD app designed for research purposes (EasyVSD), the same video VSD functionality is now available in a commercially available app, GoVisual™1.

Conclusion

The results of this study offer initial evidence that the introduction of video VSD technology can serve to increase the number of communicative turns taken by young children with ASD and complex communication needs during a high-interest shared activity (i.e., watching videos). Effective AAC intervention for this population must address the social communication difficulties associated with ASD, and result in increases both in joint attention, and in the effectiveness and frequency of communication for social interaction purposes (Caron et al., 2018; Ganz, 2015; Logan et al., 2017). The use of video VSDs, which provide embedded communication supports during video watching (a highly preferred activity for many children with ASD), is a promising approach to supporting social interaction and communication for beginning communicators with ASD.

Acknowledgments

The contents of this paper were developed under a grant to the Rehabilitation Engineering Research Center on Augmentative and Alternative Communication (The RERC on AAC) from the US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant # 90RE5017). The first author was also supported by a grant from the U.S. Department of Education (# H325D090042). The contents do not necessarily represent the policies of these agencies, and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

Notes

GoVisual™ is available from Attainment Company, 504 Commerce Parkway, Verona, WI 53593, USA. www.attainmentcompany.com/govisual

This article is based on the dissertation completed by Chapin (2019). A portion of this study was presented at the Student Scientific Paper Competition Showcase (Finalist) of the Annual Conference of the Rehabilitation Engineering and Assistive Technology Society of North America, Arlington, Va.

References

- Anderson D, Lord C, Risi S, DiLavore P, Shulman C, Thurm A….Pickles A (2007). Patterns of growth in verbal abilities among children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75, 594–604. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babb S, McNaughton D, Light J, & Caron J (2020). “Two friends spending time together”: The impact of video visual scene displays on peer social interaction for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Beukelman D & Light P (2020). Augmentative and alternative communication: Supporting children and adults with complex communication needs. Baltimore MD: Brookes Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Binger C & Light J (2007). The effect of aided AAC modeling on the expression of multi-symbol messages by preschoolers who use AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 23, 30–43. doi: 10.1080/07434610600807470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron J, Holyfield C, Light J, & McNaughton D (2018). “What have you been doing?” Supporting displaced talk through augmentative and alternative communication video visual scene display technology. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups 3, 123–135. doi: 10.1044/persp3.SIG12.123 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caron J, Laubscher E, Light J, & McNaughton D (2020). Effect of video VSDs in an AAC app on communicative turns by individuals with ASD and CCN. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Caron J, Light J, Davidoff BE, & Drager KD (2017). Comparison of the effects of mobile technology AAC apps on programming visual scene displays. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 33, 239–248. doi: 10.1080/07434618.2017.1388836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter M, & Iacono T (2002). Professional judgments of the intentionality of communicative acts. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 18, 177–191. doi: 10.1080/07434610212331281261 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drager KD, Light J, Currall J, Muttiah N, Smith V, Kreis D & Wiscount J (2019). AAC technologies with visual scene displays and “just in time” programming and symbolic communication turns expressed by students with severe disability. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 44, 321–336. doi: 10.3109/13668250.2017.1326585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drager KD, Light JC, Carlson R, D’Silva K, Larsson B, Pitkin L, & Stopper G (2004). Learning of dynamic display AAC technologies by typically developing 3-year-olds. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 47, 1133–1148. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/084) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fäldt A, Fabian H, Thunberg G, & Lucas S (2020). “All of a sudden we noticed a difference at home too”: Parents’ perception of a parent-focused early communication and AAC intervention for toddlers. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 36, 143–154. doi.org/ 10.1080/07434618.2020.1811757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Dale PS, Reznick JS, Bates E, Thal DJ, Pethick SJ, … Stiles J (1994). Variability in early communicative development. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59(5), i–185. doi: 10.2307/1166093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost L & Bondy A (2002). The Picture Exchange Communication System training manual (2nd ed). Cherry Hill, NJ: Pyramid Educational Consultants. [Google Scholar]

- Ganz J (2015). AAC interventions for individuals with autism spectrum disorders: State of the science and future research directions. Augmentative and Alternative Communication 31, 203–214. doi: 10.3109/07434618.2015.1047532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz JB, & Hong ER (2014). AAC intervention mediated by natural communication partners. In Ganz JB (Ed.), Aided augmentative and alternative communication for people with ASD (pp. 77–93). In Matson J (Series Ed.), Autism and child psychopathology series. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Holyfield C (2019). Preliminary investigation of the effects of a prelinguistic AAC intervention on social gaze behaviors from school-age children with multiple disabilities. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 35, 285–298. doi: 10.1080/07434618.2019.1704866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holyfield C, Caron JG, Drager K, & Light J (2019). Effect of mobile technology featuring visual scene displays and just-in-time programming on communication turns by preadolescent and adolescent beginning communicators. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 21, 201–211. doi: 10.1080/17549507.2018.1441440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holyfield C, Drager K, Kremkow J, & Light J (2017). Systematic review of AAC intervention research for adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 33, 201–212. doi: 10.1080/07434618.2017.1370495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner R & Baer D (1978). Multiple-probe technique: A variation of the multiple baseline. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 11, 189–196. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1978.11-189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono T, Trembath D, & Erickson S (2016). The role of augmentative and alternative communication for children with autism: Current status and future trends. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12, 2349–2361. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S95967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratochwill T, Hitchcock J, Horner R, Levin J, Odom S, Rindskopf D, & Shadish W (2010). Single-case designs technical documentation. Retrieved from What Works Clearinghouse website: http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/pdf/wwc_scd.pdf.

- Laubscher E, & Light J (2020). Core vocabulary lists for young children and considerations for early language development: a narrative review. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 36, 43–53. doi: 10.1080/07434618.2020.1737964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laubscher E, Light J, & McNaughton D (2019). Effect of an application with video visual scene displays on communication during play: Pilot study of a child with autism spectrum disorder and a peer. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 35, 299–308. doi: 10.1080/07434618.2019.1699160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laubscher E, Raulston TJ, & Ousley C (2020). Supporting peer interactions in the inclusive preschool classroom using visual scene displays. Journal of Special Education Technology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/0162643420981561 [DOI]

- Lee J & Cherney L (2018). Tau-U: A quantitative approach for analysis of single-case experimental data in aphasia. American Journal of Speech-language Pathology, 27, 495–503. doi: 10.1044/2017_AJSLP-16-0197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light J, Caron J, Currall J, Knudtson C, Ekman M, Holyfield C, …Drager K (2016, August). Just-in-time programming of AAC apps for children with complex communication needs. Seminar presented at the biennial conference of the International Society for Augmentative and Alternative Communication, Toronto, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Light J, Collier B, & Parnes P (1985). Communication interaction between young nonspeaking physically disabled children and their caretakers: Part 1: Discourse patterns. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 1, 63–74. doi: 10.1080/07434618512331273561 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Light J & Drager K (2007). AAC technologies for young children with complex communication needs: State of the science and future research directions. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 23, 204–216. doi: 10.1080/07434610701553635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light J & McNaughton D (2012). Supporting the communication, language, and literacy development of children with complex communication needs: State of the science and future research priorities. Assistive Technology, 24, 34–44. doi: 10.1080/10400435.2011.648717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light J, McNaughton D, Beukelman D, Fager SK, Fried-Oken M, Jakobs T, & Jakobs E (2019). Challenges and opportunities in augmentative and alternative communication: Research and technology development to enhance communication and participation for individuals with complex communication needs. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 35, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/07434618.2018.1556732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light J, McNaughton D, & Caron J (2019). New and emerging AAC technology supports for children with complex communication needs and their communication partners: State of the science and future research directions. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 35, 26–41. doi: 10.1080/07434618.2018.1557251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light J, McNaughton D, & Jakobs T (2014). Developing AAC technology to support interactive video visual scene displays. RERC on AAC: Rehabilitation Engineering Research Center on Augmentative and Alternative Communication. Retrieved from https://rerc-aac.psu.edu/development/d2-developing-aac-technology-to-support-interactive-video-visual-scene-displays/

- Light J, Wilkinson K, Thiessen A, Beukelman D, & Fager S (2019). Designing effective AAC displays for individuals with developmental or acquired disabilities: State of the science and future research directions. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 35, 42–55. doi: 10.1080/07434618.2018.1558283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan K, Iacono T, & Trembath D (2017). A systematic review of research into aided AAC to increase social-communication functions in children with autism spectrum disorder. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 33, 51–64. doi: 10.1080/07434618.2016.1267795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek M, & Wenstrup C (2013). Television, video game and social media use among children with ASD and their typically developing siblings. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 1258–1271. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1659-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy J, Broach J, & Benigno J (2016). Joint attention profiles for children with autism in interactions with augmentative and alternative communication systems. Clinical Archives of Communication Disorders, 1, 69–76. doi: 10.21849/cacd.2016.00024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy JW, Benigno JP, Broach J, Boster JB, & Wright BM (2018). Identification and drawing of early concepts in children with autism spectrum disorder and children without disability. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 34, 155–165. doi: 10.1080/07434618.2018.1457716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McReynolds L & Kearns K (1983). Single-subject experimental designs in communicative disorders. Baltimore, MD; University Park Press. [Google Scholar]

- Menear KS, & Ernest JM (2020). Comparison of physical activity, TV/video watching/gaming, and usage of a portable electronic devices by children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10995-020-03013-2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Millar DC, Light JC, & Schlosser RW (2006). The impact of augmentative and alternative communication intervention on the speech production of individuals with developmental disabilities: A research review. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 49, 248. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin K, Ganz J, Gregori E, Foster M, Gerow S, Genç-Tosun D, & Hong E (2018). A systematic quality review of high-tech AAC interventions as an evidence-based practice. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 34, 104–117. doi: 10.1080/07434618.2018.1458900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy P & Sigman M (2015). Joint attention, social competence, and developmental psychopathology. In Theory and Method (Vol. 1, pp. 293–332). John Wiley and Sons Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Parker RI, & Vannest K (2009). An improved effect size for single-case research: Nonoverlap of all pairs. Behavior Therapy, 40, 357–367. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2008.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker R, Vannest K, Davis J, & Sauber S (2011). Combining nonoverlap and trend for single-case research: Tau-U. Behavior Therapy, 42, 284–299. doi:S0005789411000153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rispoli M, Lang R, Neely L, Camargo S, Hutchins N, Davenport K, & Goodwyn F (2013). A comparison of within-and across-activity choices for reducing challenging behavior in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Behavioral Education, 22, 66–83. doi: 10.1007/s10864-012-9164-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland C (2013). Online Communication Matrix [Web site]. Portland, OR: Oregon Health & Science University, Design to Learn Projects Website: http://communicationmatrix.org [Google Scholar]

- Rowland C, & Fried-Oken M (2010). Communication Matrix: A clinical and research assessment tool targeting children with severe communication disorders. Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine, 3, 319–329. doi: 10.3233/PRM-2010-0144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shane H & Albert P (2008). Electronic screen media for persons with autism spectrum disorders: Results of a survey. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1499–1508. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0527-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan P & Alant E (2018). Using peer-mediated instruction to support communication involving a student with autism during mathematics activities: A case study. Assistive Technology, 30, 9–15. doi: 10.1080/10400435.2016.1223209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therrien M & Light J (2018). Promoting peer interaction for preschool children with complex communication needs and autism spectrum disorder. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 27, 207–221. doi: 10.1044/2017_AJSLP-17-0104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worah S, McNaughton D, Light J, & Benedek-Wood E (2015). A comparison of two approaches for representing AAC vocabulary for young children. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17, 460–469. doi: 10.3109/17549507.2014.987817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]