Abstract

Educational print materials for young women breast cancer survivors (YBCS) are supplemental tools used in patient teaching. However, the readability of the text coupled with how well YBCS understand or act upon the material are rarely explored. The purpose of this study was to assess the readability, understandability, and actionability of commonly distributed breast cancer survivorship print materials. We used an environmental scan approach to obtain a sample of breast cancer survivorship print materials available in outpatient oncology clinics in the central region of a largely rural Southern state. The readability analyses were completed using the Flesch-Kincaid (F-K), Fry Graph Readability Formula (Fry), and Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG). Understandability and actionability were analyzed using Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool for Printable Materials (PEMAT-P). The environmental scan resulted in a final sample of 14 materials. The mean readability of the majority of survivorship materials was “difficult,” but the majority scored above the recommended 70% in both understandability and actionability. The importance of understandability and actionability may outweigh readability results in cancer education survivorship material. While reading grade level cannot be dismissed all together, we surmise that patient behavior may hinge more on other factors such as understandability and actionability. Personalized teaching accompanying print material may help YBCS comprehend key messages and promote acting upon specific tasks.

Keywords: Breast cancer survivorship, Patient education, Readability, Understandability, Actionability, Print materials

Currently, more than 3.8 million women have a history of breast cancer, and 7% of these women are younger than 50 years of age [1]. While this percentage may seem low, breast cancer is the most common cancer diagnosis for younger women between the ages of 15 and 39 [2]. As many of these women complete active treatment and progress into survivorship, they are faced with additional challenges specific to their age and stage in life. New concerns have emerged regarding the long-term physical side effects of treatment [3], managing fear of cancer recurrence [4], reentering the workforce [5], and addressing potential fertility issues [6]. Additionally, these young women are visiting their oncologists and care team members less frequently than during active treatment, leaving them fewer opportunities to address these critical life issues with their care team.

The reduced interaction time between young women and their providers may affect the breadth and depth of topics covered during follow-up visits in survivorship and lead to a communication breakdown [7]. As a result, young women in survivorship may feel unclear about treatment plans or have unmet expectations of the follow-up visits which could compromise the quality of their care [8–10]. The consequences of communication breakdowns could result in patients’ distress over unmet informational needs [7], medication errors [11], and poor medical outcomes [12]. In an effort to prevent communication breakdowns, educational print materials are often used as supplemental tools to assist oncologists and oncology team members engaging in the patient-centered communication process, particularly during survivorship [13, 14]. Clinicians often provide the print materials to the patient at the initiation of treatment and during follow-up appointments as needed. Young women can use these print materials independently outside of clinical encounters. Importantly, they may refer to the materials to find information about specific survivorship challenges like coping with body image disturbances and managing lymphedema [3, 15, 16].

Oncologists and oncology nurses often rely heavily on their verbal communication skills to teach during the clinical encounter [17], and they also have to consider each patient’s level of health literacy (i.e., how well each patient can comprehend and apply health information [18]), especially when selecting supplementary print materials. Despite the increased efforts to create more understandable cancer education material for patients with a range of health literacy levels [19], many cancer print materials still contain complex conceptual health information in text-heavy formats and can be difficult to understand for the average reader [20]. As a result, oncologists and oncology nurses should evaluate how suitable the cancer print materials are for their patients. However, few are appropriately prepared to evaluate the materials based on three fundamental concepts t of readability, understandability, and actionability.

Readability is most commonly defined as the level of difficulty patients may have in comprehending material and the subsequent level of success patients may obtain in understanding the material [21]. Readability is often expressed as reading grade level and represents only one facet of material evaluation. Understandability is a concept broadly defined as how well patients can process and explain key messages or main points in materials they read [22]. Actionability pertains to how well patients can apply information presented in materials [22]. These three related concepts impact a patient’s ability to comprehend and apply the information.

A robust amount of literature exists regarding readability of breast cancer education materials [20, 23]. Additionally, the two concepts of understandability and actionability are frequently measured in breast cancer education materials [24, 25]. However, to our knowledge, limited research exists that evaluates these three concepts for survivorship material specific to young women. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the readability, understandability, and actionability of commonly available breast cancer survivorship print materials for young women with a history of breast cancer. Determining the suitability of such material, or lack thereof, will assist oncologists and oncology nurses to identify effective material specific to young women and their unique needs.

Methods

In January through March 2020, we conducted an environmental scan to systematically evaluate print breast cancer survivorship materials available in outpatient oncology clinics in the central region of a largely rural Southern state. To identify outpatient oncology clinics, first we consulted with a panel of two oncologists and one oncology nurse who provided the study team with an initial list of five outpatient oncology clinics and patient education sites plus one electronic medical record used at four outpatient oncology clinics. Second, we selected three additional sites where many young women sought treatment as recommended by staff members at the initial outpatient oncology clinics. Overall, we visited eight outpatient oncology clinics and accessed one electronic medical record used at four outpatient oncology clinics to obtain print breast cancer educational survivorship materials.

Selection of Materials

We visited each of the eight outpatient oncology clinics to physically obtain printed breast cancer survivorship materials using specific criteria during the first 3 months of 2020. We selected print materials if they (1) were freely available in central locations such as waiting rooms or lobbies, (2) were specific to breast cancer, (3) provided detailed information about survivorship, and (4) were directly given to patients by oncologists or oncology nurses as reported by the staff.

We also searched the UpToDate clinical education resource [26] information embedded within Epic—an electronic medical record—for any relevant patient education materials [27]. The keywords of “breast cancer” were used to search all of the relevant patient education materials within the UpToDate resource section within the Epic database. We selected any relevant materials using the same selection criteria as described above.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We narrowed our selection of print breast cancer survivorship materials by using a set of inclusion and exclusion criteria. All material specific to breast cancer survivorship for young women was included in the final sample. Any material that was directly given to young women by physicians or nurses was included in the final sample to focus on material that was used during the clinical encounters. Additionally, any material specific to genetic testing for BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations was included as this is especially relevant for young women in survivorship [28].

We excluded print materials if they were not specific to breast cancer survivorship (e.g., general cancer information, communication with family members, palliative care, etc.). We also excluded online material available on websites to focus only on material that was distributed or available in the clinical setting. Furthermore, we chose to exclude materials related to treatment (medical or surgical), diagnosis, and prevention to focus solely on survivorship material for the purposes of this study. All non-informational brochures, drug advertisements, and information for support services (e.g., where to buy a wig and how to attend support groups) were excluded. We did not exclude any materials based on publication date.

Readability Analysis

The readability analysis of the print breast cancer survivorship materials was conducted using three standardized formulas: (1) Flesch-Kincaid scoring (F-K), (2) Fry Graph Readability Formula (Fry), and (3) Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG; [29–31]). For each of the print materials, 1800-word representative samples were used for the readability analyses. Any material that was less than 1800 words was assessed in entirety. All readability assessments were completed by a team of plain language experts using Microsoft Office at the Center for Health Literacy at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS).

Flesch-Kincaid Scoring

The F-K is used to calculate readability of material based on the length of sentences and words [30]. The resulting F-K score corresponds with reading grade level.

Fry Graph Readability Formula

The Fry formula was used to assess the text’s written grade level [29]. The Fry measures sentences and syllables per 100 words. The results are then plotted on a graph resulting in an approximate reading grade level.

SMOG

The SMOG is used to determine readability by taking the square root of the amount of polysyllabic words in 30 sentences [31]. Three points are added to the final score to determine the reading grade level.

Understandability and Actionability Analysis

The understandability and actionability analyses of the print breast cancer survivorship materials were completed using Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool for Printable Materials (PEMAT-P) [32]. The analyses were completed by a team of three plain language experts at the Center for Health Literacy at UAMS. Two experts completed the analyses independently and a third, more seasoned expert, resolved any discrepancies.

PEMAT-P

The PEMAT-P was developed for healthcare professionals to evaluate how easily materials can be read and acted upon [33]. The PEMAT-P tool consists of 26 items with two subscales—understandability and actionability. Understandability was evaluated with the raw percentage of the first 19 items pertaining to items in six areas for content, word choice and style, use of numbers, organization, layout and design, and use of visuals. Actionability was determined with the raw percentage of the last six items which are focused on how well the material directs the reader to take action as described in the material. Each item is rated on a binary scale (yes/no) excluding the items which scored as “not applicable.” The scores of the “yes” responses in the two subscales range from 0 to 100% with the higher the percentage representing greater understandability or actionability. A result of 70% or higher is the recommended score for patient education materials for both understandability and actionability [32].

Overall, the PEMAT-P demonstrates moderate to substantial interrater reliability of the understandability (Kappa = 0.48 – 0.84) and actionability subscales (Kappa = 0.35 – 0.76). Lastly, the PEMAT-P shows strong reliability for understandability (Cronbach’s α = 0.66 - 0.82) and actionability (Cronbach’s α = 0.71 – 0.85) subscales [33].

Results

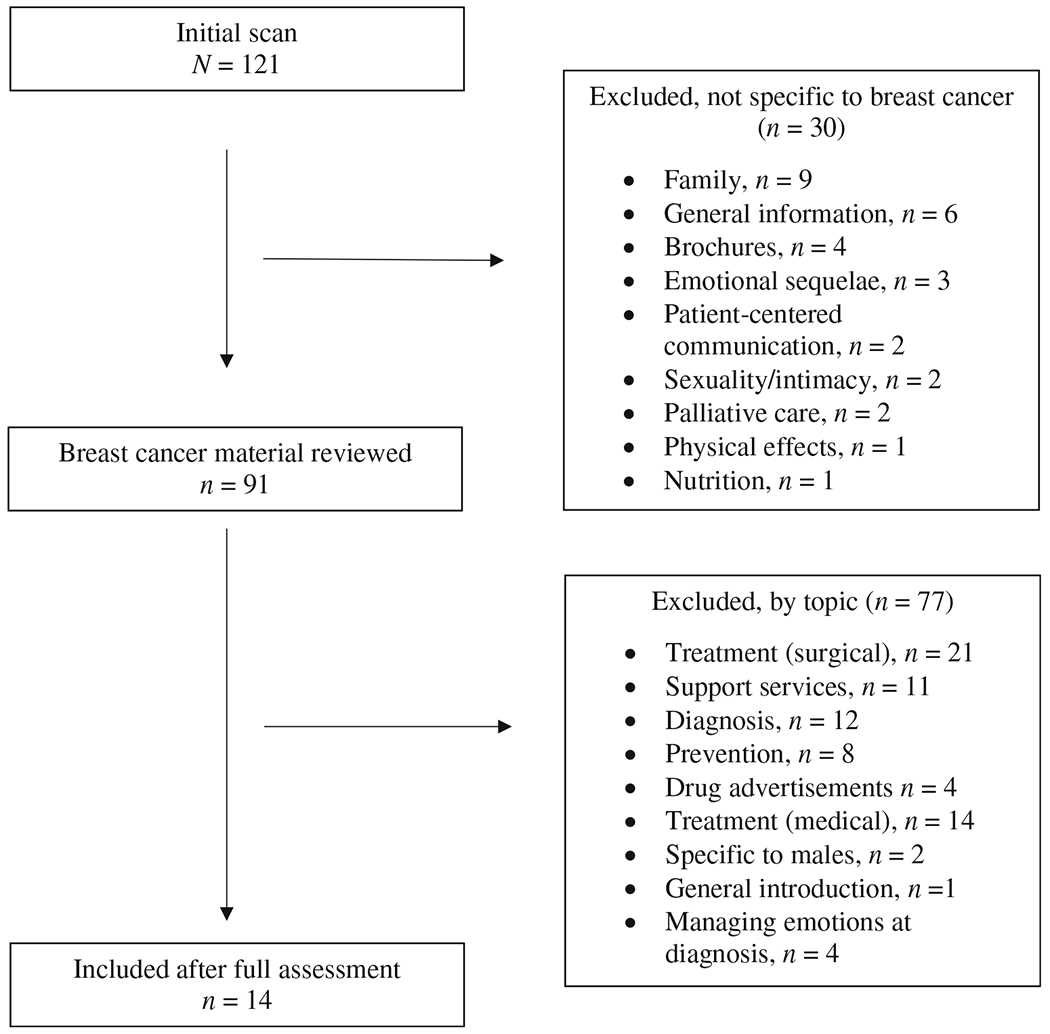

The environmental scan of outpatient oncology clinics initially resulted in 95 individual print materials being identified and which included two books consisting of 22 and 19 chapters, respectively. Searching the patient education materials in Epic resulted in 26 separate print materials. Overall, 121 individual print materials were included in the initial sample. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 14 print breast cancer survivorship materials were used for this analysis. See Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow of selection of sample of print breast cancer educational materials

The final sample included four chapters in each of the two books (Breast Cancer Treatment Handbook [34] and Breast Cancer Survivorship Handbook [35]), two patient education handouts from Epic (Genetic Testing and BRCA Gene Test; [36, 37]), two multi-page booklets on genetic testing (Myriad Risk for Hereditary Cancer and BRACAnalysis: Beyond Risk; [38, 39]), one pamphlet published by American Cancer Society (If You Have Breast Cancer [40]), and one patient resource magazine (Triple Negative Breast Cancer; [41]). We selected four chapters congruent in content in each of the two books pertaining to survivorship issues of fear, body image, fertility, and maintaining healthy lifestyles.

Readability Results

The mean readability of the majority of printed breast cancer survivorship materials ranged from “average” to “difficult” based on the scoring. The reading levels of the two books, two multi-page booklets, and a patient resource magazine were scored as greater than a 9th grade reading level. Reading levels at or above 9th grade are considered “difficult” for the average reader. The two print survivorship materials readability, as identified through Epic, were scored as “average” with the mean reading levels ranging from 7th to 9th grades. Lastly, one print material scored “average” with a reading level of 6th grade.

The chapters of the two books varied somewhat. Three chapters within the Breast Cancer Treatment Handbook scored as “difficult” for the average reader ranging from 9th grade reading level and beyond. Only one chapter was scored as “average” with a reading level of 8th grade. The same readability results were duplicated for the Breast Cancer Survivorship Handbook. Three chapters were scored as “difficult” ranging from 9th grade reading level and beyond, and one was scored as “average” with a reading level of 8th grade. See Table 1 for a detailed description of the readability scores.

Table 1.

Readability scores of final sample of print educational breast cancer survivorship materials. The score is equivalent to reading grade level. Materials ranging from 0 to 7 are considered easy to read, 7–9 average, and greater than 9 difficult

| Print material | F-K | SMOG | FRY | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| If You have Breast Cancer (ACS) | 4.6 | 7.4 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 1.4 |

| Risk for Hereditary Cancer (Myriad) | 10.1 | 12.3 | 17.0 | 13.1 | 3.5 |

| Triple Negative Breast Cancer (Patient Resource Magazine) | 9.5 | 11.5 | 13.0 | 11.3 | 1.8 |

| BRCA Gene Test (Epic) | 5.4 | 8.9 | 7.0 | 7.1 | 1.8 |

| Genetic Testing for Hereditary Cancers (Epic) | 7.5 | 10.6 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 1.6 |

| BRACAnalysis: Beyond Risk to Options | 9.7 | 12.2 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 2.2 |

| Breast Cancer Treatment Handbook | 10.5 | ||||

| Chapter 4 – Calming Fears | 7.0 | 9.6 | 8.0 | 8.2 | 1.3 |

| Chapter 16 – Sexuality after Breast Caner | 11.1 | 13.0 | 16.0 | 13.4 | 2.5 |

| Chapter 17 – Future Fertility | 12.2 | 13.3 | N/A1 | 12.8 | 0.8 |

| Chapter 20 – Diet and Exercise | 7.6 | 10 | 10 | 9.2 | 1.4 |

| Breast Cancer Survivorship Handbook | 10.6 | ||||

| Chapter 2 – Managing Fear of Recurrence | 6.9 | 9.8 | 8.0 | 8.2 | 1.5 |

| Chapter 11 – Dealing with Body Image Issues | 10.2 | 12.3 | 17.0 | 13.1 | 3.5 |

| Chapter 12 – Fertility after Treatment | 10.5 | 11.8 | N/A | 11.2 | 0.9 |

| Chapter 19 – Planning for a healthy lifestyle | 8.0 | 10.3 | 11.0 | 9.8 | 1.6 |

A score of N/A means that the sample was outside the formula’s scope and no score was able to be charted on the graph.

Understandability and Actionability Results

About half of the sample print breast cancer survivorship materials scored above the recommended score of 70% for understandability. Three chapters from the Breast Cancer Survivorship Handbook scored high, ranging from 83 to 92%, while one chapter was scored as 58% understandable. The mean score for understandability of the chapters was 80% [35]. Similarly, three chapters in the Breast Cancer Treatment Handbook scored between 76% and 79%, and one chapter was scored at 62% understandability. The mean score for understandability of the four chapters was 74% [34]. The two print survivorship materials identified through Epic scored above 70%, whereas the BRACAnalysis: Beyond Risk multi-page booklet and Triple Negative Breast Cancer patient resource magazine scored 63% and 60%, respectively [39, 41]. The lowest score for understandability was Risk for Hereditary Cancer, which was 47% [38].

Three of the sample print breast cancer survivorship materials scored 100% for actionability [36, 39, 40], which was well above the recommended 70% score. Two chapters from the Breast Cancer Treatment Handbook scored 100% in actionability and the remaining two chapters scored 83 and 80%. The mean actionability of the book chapters was 91% [34]. One chapter from the Breast Cancer Survivorship Handbook scored 100% in actionability, and three of the remaining chapters scored 80% in actionability. This resulted in a mean actionability of the chapters of 85% [35]. One multi-page booklet scored 67% for actionability [38] and one of the print survivorship materials identified through Epic scored 67% [37]. The Triple Negative Breast Cancer patient resource magazine received the lowest actionability score of 40%, well below the recommended 70% or higher score [41].

Overall, eight individual materials scored above 70% in both understandability and actionability. The American Cancer Society pamphlet and the patient education handout from Epic scored above 70% for both concepts of understandability and actionability [36, 40]. The mean scores for the chapters in both of the books, Breast Cancer Treatment Handbook and Breast Cancer Survivorship Handbook, were above 70%, respectively [34, 35]. Six chapters in the two books scored above 70% in both understandability and actionability (see Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Understandability and actionability scores of final sample of print educational breast cancer survivorship materials. A score of 70% or greater is recommended for patient education materials

| Print material | PEMAT-P understandability | PEMAT-P actionability |

|---|---|---|

| If You have Breast Cancer (ACS) | 73% | 100% |

| Risk for Hereditary Cancer (Myriad) | 47% | 67% |

| Triple Negative Breast Cancer (Patient Resource Magazine) | 60% | 40% |

| BRCA Gene Test (Epic) | 75% | 100% |

| Genetic Testing for Hereditary Cancers (Epic) | 79% | 67% |

| BRACAnalysis: Beyond Risk to Options | 63% | 100% |

| Breast Cancer Treatment Handbook | ||

| Chapter 4 – Calming Fears | 79% | 100% |

| Chapter 16 – Sexuality after Breast Caner | 76% | 100% |

| Chapter 17 – Future Fertility | 77% | 80% |

| Chapter 20 – Diet and Exercise | 62% | 83% |

| Mean, four chapters | 74% | 91% |

| Breast Cancer Survivorship Handbook | ||

| Chapter 2 – Managing Fear of Recurrence | 83% | 100% |

| Chapter 11 – Dealing with Body Image Issues | 58% | 80% |

| Chapter 12 – Fertility after Treatment | 85% | 80% |

| Chapter 19 – Planning for a healthy lifestyle | 92% | 80% |

| Mean, four chapters | 80% | 85% |

Table 3.

Strengths and weaknesses of materials using PEMAT-P

| PEMAT-P Item | Materials n = 14 |

Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Understandability Strengths | ||

| Organization | ||

| The material breaks or “chunks” information into short sections | 14 (100%) | All of the material was separated into paragraphs or shorter sections |

| The material presents information in a logical sequence | 14 (100%) | All of the material was presented in a logical sequence with the most important information presented first |

| Content | ||

| Material does not include information or content that distracts from its purpose | 13 (93%) | Most of the items included content directly related to the purpose |

| Use of Numbers | ||

| The material does not expect the user to perform calculations | 13 (93%) | No calculations required except asking the patient to calculate heart rate1 |

| Weaknesses | ||

| Word Choice & Style | ||

| Material uses common, everyday language | 6 (43%) | Examples of technical, unfamiliar language: |

| - Alleviate - Precautions | ||

| - Ridding - Perspective | ||

| - Incorporate | ||

| - Medical management guidelines | ||

| Use of Visual Aids | ||

| The material’s visual aids reinforce rather than distract from the content2 | 2 (33%) | Overall pictures are more decorative than informative |

| - Visuals such as holding hands not relevant | ||

| - Most pictures not supportive of text | ||

| The material’s visual aids have clear titles or captions2 | 2 (33%) | Minimal use titles or captions for visuals (graphs or pictures) |

| Actionability Strengths | ||

| The material clearly identifies at least one action the user can take | 14 (100%) | All of the material clearly directed the patient to taking at least one action |

| Weaknesses | ||

| The material breaks down any action into manageable, explicit steps | 10 (72%) | Most of the material did not break down action into specific steps |

| - No description of where patients can pursue genetic testing3 | ||

| - No discussion of how to “take steps toward reconstruction”4 |

Note. A score of 70% is recommended for patient education materials.

Breast Cancer Treatment Handbook, Chapter 20: Diet and Exercise.

Sample was out of 6; remaining materials were rated as N/A.

Patient Resource Magazine.

Breast Cancer Survivorship Handbook, Chapter 11 – Dealing with Body Image Issues.

Discussion and Conclusion

The results for the readability of materials and assessment of understandability and actionability provide a thorough assessment of the reading demand of the reviewed material on a patient. However, our readability results are somewhat contradictory with our understandability and actionability results. The readability results indicate that much of the print material is written at a reading grade level that is too difficult for the average reader (or patient) to understand. However, our understandability and actionability results indicate that the average reader can understand and act upon most of the material. Consequently, we have to question the suitability of readability tests for cancer education materials.

The standardized readability formulas do not adjust for cancer-specific terms such as chemotherapy which often have no built-in replacement words to lower the readability score [20]. Furthermore, the readability formulas may be restrictive in measuring reading grade levels based off syllables or words within a passage when much of the cancer education material includes multi-syllable words [42]. After interpreting our results and considering the limitations of the readability formulas, we question whether the degree to which a reader (or patient) can act upon the material (e.g., obtaining BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 genetic testing) supersedes the importance of the reading grade level. While reading grade level cannot be dismissed all together, we surmise that patient behavior may hinge more on other factors such as understandability and actionability.

Examining the understandability and actionability of cancer education materials for young women breast cancer survivors is especially critical given their unique needs. Young women are in survivorship longer and acting upon such material (e.g., monitoring breast changes) is critical to maintain their health and well-being. Thus, oncologists and oncology team members need to consider the domains within understandability and actionability particularly for patients with unique needs. For example, our results indicate a lack of visuals or pictures of younger women. While this imagery reflects the median age of women with breast cancer [43], pictures of young women could positively impact the understandability and actionability of the material. This could have a direct effect on young women survivors’ identification and subsequent actions taken within survivorship. However, the effect of the material on patient behavior is outside of the scope of this study.

Conclusion

Our results show the high reading grade levels across most of the samples range from “average” to “difficult,” but these findings are not a full representation of the level of stress the material has on the reader. The combination of the readability and understandability and actionability allows oncologists and oncology team members to better evaluate the material as a whole. Readability is only one component of the material. The other two concepts of understandability and actionability provide a more direct link to assessing how a patient will respond and act upon educational material. By evaluating and accounting for readability, understandability, and actionability, oncologists and oncology team members are better equipped to select materials most suitable for young women breast cancer survivors.

Limitations

The methodology to conduct the environmental scan is not without limitations. First, we did not visit outpatient clinics throughout the whole state. Instead, we visited outpatient clinics in one centralized region that was primarily urban and suburban. Even though patients living in rural areas may travel to receive treatment in the central area, other facilities may have offered different material. Second, we selected our materials without input from young women breast cancer survivors. We may have inadvertently selected material that was readily available, but young women may seek additional materials from other sources outside of those provided in the clinical encounters. Third, although our sample size may be considered small, these materials were available in a central region which was accessible to patients across the state who travel for annual survivorship visits. Given the reach of these materials, we believe our results are still significant in context.

Practice Implications

Oncologists and oncology team members should continue to assess education material specific to young women in survivorship. They can use standardized tools like readability formulas or the PEMAT-P or may choose to quickly evaluate material based on certain domains (like the use of visual aids). Additionally, oncologists and oncology team members can use the teach-back method to reinforce patient teaching topics to offset any limitations within the material. However, all of these recommendations should be taken in context of the patient preference. The patient’s preference for the material may supersede current evaluation tools. A patient may use and find benefit from educational print materials despite the readability and understandability and actionability scores.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff at the Center for Health Literacy at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences for their assistance with data analysis. The authors would also like to thank Dr. James V. Parker, Jr. for his assistance in editing. Dr. Pearman Parker is currently supported by the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Translational Research Institute (TRI) grants (KL2TR003108; UL1TR003107) through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Arkansas Breast Cancer Research Program.

References

- 1.Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, Alfano CM, Jemal A, Kramer JL, Siegel RL (2019) Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 69(5):363–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson RH, Anders CK, Litton JK, Ruddy KJ, Bleyer A (2018) Breast cancer in adolescents and young adults. Pediatr Blood Cancer 65(12):e27397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lovelace DL, McDaniel LR, Golden D (2019) Long-term effects of breast cancer surgery, treatment, and survivor care. J Midwifery Womens Health 64(6):713–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohee AA, Adams RN, Johns SA, von Ah D, Zoppi K, Fife B, Monahan PO, Stump T, Cella D, Champion VL (2017) Long-term fear of recurrence in young breast cancer survivors and partners. Psychooncology 26(1):22–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenberg SM, Vaz-Luis I, Gong J, Rajagopal PS, Ruddy KJ, Tamimi RM, Schapira L, Come S, Borges V, de Moor JS, Partridge AH (2019) Employment trends in young women following a breast cancer diagnosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 177(1):207–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christian N, Gemignani ML (2019) Issues with fertility in young women with breast cancer. Curr Oncol Rep 21(7):58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Street RL Jr, Spears E, Madrid S, Mazor KM (2019) Cancer survivors’ experiences with breakdowns in patient-centered communication. Psychooncology 28(2):423–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazor KM, Roblin DW, Greene SM, Lemay CA, Firneno CL, Calvi J, Prouty CD, Horner K, Gallagher TH (2012) Toward patient-centered cancer care: patient perceptions of problematic events, impact, and response. J Clin Oncol 30(15):1784–1790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prince-Paul M, Kelley C (2017) Mindful communication: Being present. Semin Oncol Nurs 33(5):475–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazor KM, Street RL Jr, Sue VM, Williams AE, Rabin BA, Arora NK (2016) Assessing patients’ experiences with communication across the cancer care continuum. Patient Educ Couns 99(8):1343–1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kullberg A, Sharp L, Johansson H, Bergenmar M (2015) Information exchange in oncological inpatient care–patient satisfaction, participation, and safety. Eur J Oncol Nurs 19(2):142–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maly RC, Liu Y, Liang LJ, Ganz PA (2015) Quality of life over 5 years after a breast cancer diagnosis among low-income women: Effects of race/ethnicity and patient-physician communication. Cancer 121(6):916–926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Recio-Saucedo A, Gerty S, Foster C, Eccles D, Cutress RI (2016) Information requirements of young women with breast cancer treated with mastectomy or breast conserving surgery: A systematic review. Breast 25:1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lally RM, McNees P, Meneses K (2015) Application of a novel transdisciplinary communication technique to develop an Internet-based psychoeducational program: CaringGuidance After Breast Cancer Diagnosis. Appl Nurs Res 28(1):e7–e11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halbach SM, Ernstmann N, Kowalski C, Pfaff H, Pförtner TK, Wesselmann S, Enders A (2016) Unmet information needs and limited health literacy in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients over the course of cancer treatment. Patient Educ Couns 99(9):1511–1518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paterson CL, Lengacher CA, Donovan KA, Kip KE, Tofthagen CS (2016) Body image in younger breast cancer survivors: A systematic review. Cancer Nurs 39(1):E39–E58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Epstein RM, Street RL (2007) Patient-centered communication in cancer care: Promoting healing and reducing suffering, ed. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ratzan SC, Parker RM (2000) Introduction, in National Library of Medicine current bibliographies in medicine: Health literacy. In: Seldern CR et al. (eds) National Institutes of Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, MD [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simmons RA et al. (2017) Health literacy: Cancer prevention strategies for early adults. Am J Prev Med 53(3 s1):S73–S77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parker PD et al. (2019) The experience of chemotherapy teaching and readability of chemotherapy educational materials for women with breast cancer. J Cancer Educ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flesch R (1948) A new readability yardstick. J Appl Psychol 32(3):221–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality. The Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT) and user’s guide. 2017; Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/prevention-chronic-care/improve/self-mgmt/pemat/index.html.

- 23.Miles RC, Baird GL, Choi P, Falomo E, Dibble EH, Garg M (2019) Readability of online patient educational materials related to breast lesions requiring surgery. Radiol 291(1):112–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kressin NR, Gunn CM, Battaglia TA (2016) Content, readability, and understandability of dense breast notifications by state. J Am Med Assoc 315(16):1786–1788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tran BNN, Ruan QZ, Epstein S, Ricci JA, Rudd RE, Lee BT (2018) Literacy analysis of National Comprehensive Cancer Network patient guidelines for the most common malignancies in the United States. Cancer 124(4):769–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolters Kluwer, UpToDate. 2021: Waltham, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Epic Systems Corporation. About Us. 2020; Available from: https://www.epic.com/about.

- 28.Barcenas CH, Shafaee MN, Sinha AK, Raghavendra A, Saigal B, Murthy RK, Woodson AH, Arun B (2018) Genetic counseling referral rates in long-term survivors of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 16(5):518–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fry E (1968) A readability formula that saves time. J Read 11(7):513–578 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kincaid J et al. (1975) Memphis, TN: Naval Air Station, Millington. Tennessee 40

- 31.McLaughlin GH (1969) SMOG Grading: A new readability formula. J Read 12(8):639–646 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT) and User’s Guide. 2013; Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr/tools/self-mgmt/pemat.html.

- 33.Shoemaker S, Wolf MS, Brach C (2014) Development of the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT): A new measure of understandability and actionability for print and audiovisual patient information. Patient Educ Couns 96(3):395–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kneece JC, Breast Cancer Treatment Handbook. 2nd ed. 2017, North Charleston, SC: EduCare, Inc [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kneece JC, Breast Cancer Survivorship Handbook. 2016, North Charleston, SC: EduCare Inc [Google Scholar]

- 36.UpToDate, BRCA Gene Test. 2019: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- 37.UpToDate, Genetic Testing for Breast, Ovarian, Prostate, and Pancreatic Cancer. 2020: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins [Google Scholar]

- 38.Myriad Genetic Laboratories, myRisk Hereditary Cancer: A patient’s guide to hereditary cancer. n.d, Salt Lake City, UT [Google Scholar]

- 39.Myriad Genetic Laboratories, BRACAnalysis: Beyond Risk to Options. 2003, Salt Lake City, UT [Google Scholar]

- 40.American Cancer Society, If you have breast cancer (2016) Atlanta. American Cancer Society, Inc., GA [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patient Resource, in Patient Resource Cancer Guide: Triple Negative Breast Cancer. 2016, Linette Atwood: Overland Park, KS [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meade CD, Smith CF (1991) Readability formulas: Cautions and criteria. Patient Educ Couns 17(2):153–158 [Google Scholar]

- 43.American Cancer Society, Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2019 - 2020. 2019, Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc [Google Scholar]