Abstract

Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) is one of the major protein serine/threonine phosphatases (PPPs) with regulatory effects on several cellular processes, but its role and function in Adriamycin (ADR)-treated podocytes injury needs to be further explored. Mice podocytes were treated with ADR and PP2A inhibitor (okadaic acid, OA). After transfection, cell apoptosis was detected by flow cytometry. Expressions of podocytes injury-, apoptosis- and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)- and JNK-interacting protein 4/p38-Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (JIP4/p38-MAPK) pathway-related factors were measured using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and Western blot as needed. Interaction between PP2A and JIP4/MAPK pathway was confirmed using co-immunoprecipitation (Co-Ip) assay. In podocytes, ADR inhibited PP2A, Nephrin and Wilms’ tumor (WT) 1 expressions yet upregulated apoptosis and Desmin expression, and suppressing PP2A expressionenhanced the effects. PP2A overexpression reversed the effects of ADR on PP2A and podocyte injury-related factors expressions and apoptosis of podocytes. JIP4 was the candidate gene interacting with both PP2A and p38-MAPK pathway, and PP2A overexpression alleviated the effects of ADR on p38-MAPK pathway-related factors expressions. Additionally, in ADR-treated podocytes, PP2A suppression enhanced the effects of ADR, yet silencing of JIP4 reversed the effects of PP2A suppression on regulating p38-MAPK pathway-, apoptosis- and EMT-related factors expressions and apoptosis, with upregulations of B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) and E-cadherin and down-regulations of Bcl-2 associated protein X (Bax), cleaved (C)-casapse-3, N-cadherin, Vimentin and Snail. PP2A protects ADR-treated podocytes against injury and EMT by suppressing JIP4/p38-MAPK pathway, showing their interaction in podocytes.

Keywords: Chronic kidney diseases, Protein phosphatase 2A, Podocytes, Adriamycin, JNK-interacting protein 4 (JIP4), p38-Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (p38-MAPK) pathway

Introduction

Defined by abnormal kidney structure or function including glomerular filtration rate (GFR), thresholds of albuminuria and duration on injury, chronic kidney diseases (CKDs) are currently seen as a prevalent progressive and irreversible disorder (Glassock et al. 2017). Adriamycin (ADR) is a commonly used anti-cancer drug in clinic practice (Gao et al. 2018; Li et al. 2021). ADR, also known as Doxorubicin (Dox), is found as a suppressor for DNA topoisomerase II and belongs to a family of anthracycline anti-cancer drugs (Chen et al. 2018). However, the severe toxicity to non-cancerous cells, especially kidney toxicity (Liu et al. 2018; Roomi et al. 2014) and heart toxicity (Taskin et al. 2020) has greatly limited its application. ADR-induced kidney injury, which refers to ADR nephropathy, is a severe clinical complication with high mortality and morbidity. ADR treatment in susceptible rodents, such as the BALB/c mouse, produces damage to the glomerulus, which is similar to human CKDs due to the main focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (Luo et al. 2020) In recent decades, although many studies have been conducted on ADR nephropathy, the therapeutic outcome of this disease is still unsatisfactory due to unclear pathogenic mechanism and a lack of specific therapeutic targets. The podocyte has recently become a research focus, and there are increasing reports showing that ADR exerts toxicity to podocytes, which leads to podocyte injury (Liu et al. 2018; Ni et al. 2018; Yu et al. 2016).

As a member of protein serine/threonine phosphatases (PPPs) family with ubiquitous expression of remarkable conserved enzyme within cell, protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) consists of catalytic C subunit and a structural A subunit that further binds to a regulatory B subunit (Baskaran and Velmurugan 2018; Reynhout and Janssens 2019). Endogenous inhibition of PP2A has been shown to promote malignant development and prognosis of a variety of cancers, and PP2A activity suppression also promotes malignant transformation (Kauko and Westermarck 2018). It has been suggested that PP2A is implicated in the effects on enhancing gastric cancer stemness (Enjoji et al. 2018). Also, PP2A is a key phosphatase during progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) to lung cancer (Nader et al. 2019). In addition, PP2A has a regulatory effect on both estrogen receptor (ER) and androgen receptor (AR) signaling via hormonal receptors in breast cancer (Cristóbal et al. 2017). Furthermore, PP2A is additionally discovered to be implicated in CKDs, in which p38-Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (JIP4/p38-MAPK) pathway is involved (Lee et al. 2019; Tobisawa et al. 2017). However, the interaction between PP2A and p38-MAPK pathway remained inadequately discovered and discussed. Protein phosphatase 2A modulates podocyte maturation and glomerular functional integrity in mice (Zhu et al. 2019).

JIP4, also known as JNK-associated leucine zipper protein (JLP) or SPAG9, is a brand-new biomarker for malignancies (Li et al. 2018). JIP4, as a scaffold protein, plays a pivotal role in regulating MAPK signaling cascades, that is, JIP4 can bind to, promotes the activation, and is phosphorylated by p38-MAPK (Willett et al. 2017). Previous studies have shown the role of JIP4/p38-MAPK in exocyst complex and G2 phase of cell cycle, which points out their interactions (Pinder et al. 2015; Tanaka et al. 2014). However, its interaction with PP2A in ADR-induced kidney injury should be addressed. Therefore, our current study mainly aimed to discover the interaction between PP2A and JIP4/p38-MAPK pathway in podocytes cells in vitro, hoping to develop a strategy for prevention and treatment of ADR-induced kidney injury in the future.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

Conditionally immortalized mice podocyte MPC5 (BNCC337685) used for current study was purchased from BeiNa Bio (Beijing, China) and was cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (R7509, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, F2442, Sigma-Aldrich, USA), 100 U/mL–100 µg/mL penicillin–streptomycin (P4333, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and 10 IU/mL murine interferon-γ (IFN-γ, I4777, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Human embryonic kidney cell line HEK-293 (CRL-1573) was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM, M4655, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) with 10% FBS at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Adriamycin (ADR)-induced cell injury model was constructed as previously described (Liu et al. 2018). For our study, ADR (A183027) was purchased from Aladdin (Shanghai, China). In detail, podocytes were cultured in a culture flask coated with type I collagen (17018-029, Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) at 33 °C with 10% FBS and insulin-transferrin-selenium (ITS-G, 41400-045, Gibco, USA). For differentiation, podocytes were thermoshifted to 37 °C for 10–14 days, followed by the addition with 100 nmol/L ADR for 24 h. PP2A inhibitor okadaic acid (OA, HB0468) was offered by HelloBio (Princeton, NJ, USA) and was added into MPC5 cells at a final concentration of 5 nmol/L for 24 h after MPC5 cells were treated with ADR for 24 h.

For PP2A overexpression and JIP4 silencing, we performed transient transfection according to the manufacturer’s instructions. We monitored gene silencing efficiency by Western blot and selected the cells with the most efficient gene silencing for subsequent experiments. To inhibit p38, we pretreated the cells with 5 μmol/L of p38 MAP kinase-specific inhibitors SB203580 for 1 h before stimulation.

Transfection

PP2A overexpression plasmid and small interfering RNA targeting JIP4 (siJIP4) as well as their negative control (NC) were bought from Gene Pharma (Shanghai, China) and diluted using Opti-MEM (31985-062, Gibco, USA) prior to the transfection procedure.

The 1 × 106 cells/well MPC5 cells were seeded within 6-well plates at room temperature for 24 h. Then, once all cells became 80% confluent, the transfection was performed with Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (11668-500, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at 37 °C in accordance with the protocols provided by the manufacturer. 48 h later, cells were collected and harvested. The sequences used here were 5′-CAGAGCAUGUGUUUACAGAUC-3′, NC: 5′-GAGATATCCGTTACGTGTACA-3′.

Flow cytometry

1 × 105 MPC5 cells were first collected in a 1.5 mL reaction tubes 48 h after transfection, and centrifuged at 500×g at 4 °C for 5 min. Following the removal of the supernatant, all cells were washed using 1 mL phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and co-treated with 5 μL Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) at room temperature avoiding lights for 15 min. The staining buffer was removed via centrifugation at 500×g at 4 °C for 5 min, and cells were resuspended in 100 μL PBS, and cell apoptosis was then detected with both Annexin V-FITC cell apoptosis kit (C1062S, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and flow cytometer (B96622, Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN, USA) based on the manuals of the producers. Data were calculated finally using Kaluza C Analysis software (ver. 2.1.1, Beckman Coulter, USA).

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Trizol (15596-026, Invitrogen, USA) was employed for total RNA extraction in cells in line with the instruction provided by the manufacturer, and the extracted RNA was preserved at − 80 °C. A NanoDrop Lite spectrophotometer (ND-LITE, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was then used for concentration determination. CDNA synthesis was performed with a First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (K4201100, BioChain, Newark, CA, USA), and qRT-PCR was conducted using a kit (K5055400, BioChain, USA) in Touch real-time PCR system (CFX96, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) under these conditions: 95 °C, 10 min, and 95 °C, 15 s and 60 °C, 1 min of 40 cycles of amplification in total. Relative expressions were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method, and GAPDH was used as internal reference (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). Primer sequences used were listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers for qRT-PCR

| Gene | Primers (5′ → 3′) |

|---|---|

| PP2A | |

| Forward | TGTAGCTCTTAAGGTTCGTT |

| Reverse | CTTAAACACTCGTCGTAGAA |

| Bcl-2 | |

| Forward | CATTATAAGCTGTCACAGAGG |

| Reverse | GGAGAAATCAAACAGAGGTC |

| Bax | |

| Forward | TGAACAGATCATGAAGACAG |

| Reverse | TCTTGGATCCAGACAAGC |

| E-cadherin | |

| Forward | CTGTGTACACCGTAGTCAAC |

| Reverse | GTATTCGCCAATCTCTAAGT |

| N-cadherin | |

| Forward | TTTACAGCGCAGTCTTACC |

| Reverse | ATCAGACCTGATTCTGACAA |

| Vimentin | |

| Forward | GAATGGTACAAGTCCAAGTT |

| Reverse | CCAATAGTGTCCTGGTAGTT |

| Snail | |

| Forward | GTAACAAGGAGTACCTCAGC |

| Reverse | GTATCTCTTCACATCCGAGT |

| GAPDH | |

| Forward | GCTTAGGTTCATCAGGTAAA |

| Reverse | TGACAATCTTGAGTGAGTTG |

Western blot

Protein expressions were determined by Western blot based on description before (Ma et al. 2016). Protein lysis and extraction was performed with RIPA lysis buffer (P0013C, Beyotime, China), following cell collection and the determination of concentration of protein with bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein kit (P0012, Beyotime, China). 20 μg protein lysate samples were electrophoresed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (P0012A, Beyotime, China), and were transferred into polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (FFP32, Beyotime, China), which was blocked using 5% fat-free milk for 2 h and incubated in those primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. GAPDH was used as an internal control. After that, the membrane was incubated in horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody at room temperature for an hour and washed by tris-buffer saline tween (TBST, T1085, Solarbio, Beijing, China) for three times. Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit (PC0018S, Beyotime, China) was used for visualization following protein band collection. Data were analyzed with iBright CL750 Imaging System (A44116, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and grey values were calculated using ImageJ (ver. 5.0, Bio-Rad, USA). All antibodies used were listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Antibodies for Western blot

| Host | Dilution ratio | Catalog no. | Brand | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-PP2A antibody | Rabbit | 1:1000 | #2041 | Cell Signaling Technology (CST), Danvers, MA, USA |

| Anti-Nephrin antibody | Rabbit | 1:2000 | ab58968 | Abcam, Cambridge, UK |

| Anti-Desmin antibody | Rabbit | 1:100,000 | ab32362 | Abcam |

| Anti-WT1 antibody | Mouse | 1:200 | sc-7385 | Santa Cruz Biotech, Dallas, TX, USA |

| Anti-Bcl-2 antibody | Rabbit | 1:2000 | ab182858 | Abcam |

| Anti-Bax antibody | Rabbit | 1:10,000 | ab32503 | Abcam |

| Anti-C-caspase-3 antibody | Rabbit | 1:5000 | ab214430 | Abcam |

| Anti-JIP4 antibody | Rabbit | 1:1000 | sc-271492 | Santa Cruz Biotech |

| Anti-p-MKK4 antibody | Rabbit | 1:500 | ab131353 | Abcam |

| Anti-MKK4 antibody | Rabbit | 1:1000 | ab33912 | Abcam |

| Anti-p-p38 antibody | Rabbit | 1:2000 | ab195049 | Abcam |

| Anti-p38 antibody | Rabbit | 1:5000 | ab170099 | Abcam |

| Anti-E-cadherin antibody | Mouse | 1:2000 | ab231303 | Abcam |

| Anti-N-cadherin antibody | Rabbit | 1:2000 | ab18203 | Abcam |

| Anti-Vimentin antibody | Rabbit | 1:5000 | ab92547 | Abcam |

| Anti-Snail antibody | Rabbit | 1:200 | ab82846 | Abcam |

| Anti-GAPDH antibody | Rabbit | 1:2000 | ab181602 | Abcam |

| Goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L | Goat | 1:1000 | A0208 | Beyotime, Shanghai, China |

| Goat anti-mouse IgG H&L | Goat | 1:1000 | A0216 | Beyotime |

PP2A protein phosphatase 2 A, WT1 Wilms’ tumor 1, Bcl-2 B-cell lymphoma 2, Bax Bcl-2 associated X protein, C-caspase-3 cleaved caspase-3, JIP4 JNK-interacting protein 4, p-MKK4 phosphorylated-Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase Kinase 4, p-p38 phosphorylated-p38

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-Ip) assay

All processes with Co-Ip assay were performed following previous studies’ guidance (Tanaka et al. 2014; Tang and Takahashi 2018). A total number of 4.5 × 106 HEK-293 cells were seeded in 10 mL complete medium in a 10 cm culture dish at 37 °C with 5% CO2 overnight. The medium was then removed, and 10 mL of pre-warmed medium was added. 15 μg expression vector was first diluted in 450 μL sterile deionized water in 15 mL tube, followed by being added with 50 μL calcium chloride (CaCl2, C4901, Sigma-Aldrich, USA). 2× HEPES-buffered saline (HeBS, AAJ67505-AE, VWR International, Randor, PA, USA) were added dropwise into the tube, which was vortexed and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. The transfection mixture was added into the cells, and the medium for cell culture was replaced 20 h after transfection.

After 48 h, all cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and harvested on ice with cell scraper, and were pelleted via centrifugation at 1500×g at 4 °C for 5 min. The supernatant was removed, and ice-cold lysis buffer, including 150 mmol/L Sodium chloride (NaCl, S7653, Sigma-Aldrich, USA), 10 mmol/L Tris-hydrochloride (Tris–HCl, T3253, Sigma-Aldrich, USA), 0.5 mmol/L Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, E6758, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and 0.5% NP-40 (85124, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), was added into the pellet until all clumps disappeared. The sample was incubated on ice for 30 min, and centrifuged at 20,000×g at 4 °C for 15 min. The supernatant was transferred into a new tube and the protein concentration and expression was measured. Pre-cleaned Immunoglobin G (IgG)-Resin (786-800, G-Biosciences, St Louis, MO, USA) was transferred to a 1.5 mL tube and centrifuged at 6000×g at 4 °C for 30 s, and the supernatant was aspirated by a 27-gauge needle. The resin was resuspended in 1 mL lysis buffer, and was pelleted at 6000×g at 4 °C for 30 s. Then the resin was also resuspended in ice-cold lysis buffer. 1 mg of total cell lysates was added to a new tube and total volume was adjusted to 0.5 mL, and 20 μL resin was added into the tube, which was incubated on a rotator at 4 °C for 1 h. Finally, the resin was pelleted via centrifuged at 6000×g at 4 °C for 30 s and 0.5 mL supernatant was transferred into a new tube before Co-Ip.

The cell lysates were incubated with anti-green fluorescent protein (GFP) antibody (ab290, Abcam, UK) or anti-Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase Kinase 4 (MKK4) antibody and anti-JIP4 antibody (sc-271492, Santa Cruz Biotech, Dallas, TX, USA) (4 μg for each) at 4 °C for 1 h and 20 μL IgG-resin was added for incubation at 4 °C for 1 h. The resin was centrifuged at 6000×g at 4 °C for 30 s, and 200 μL supernatant was transferred to a new tube. The remaining supernatant was removed using a 27-gauge needle. The pellet was washed within 1 mL ice-cold lysis buffer and centrifuged at 6000×g at 4 °C for 30 s to remove the non-binding proteins. All immunoprecipitated complex was resuspended in 25 μL 2× Laemmli buffer (S3401, Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA), boiled for 10 min within SDS sample buffer (70607, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), electrophoresed by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane and subjected to analysis using Western blot. β-actin was used as an internal control.

Statistical analysis

Every experiment was performed over three times independently. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). GraphPad 8.0 software (GraphPad, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) and SPSS 20.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) were both selected to analyze the statistics. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test and independent t-test. P < 0.05 was considered as a statistical significant difference.

Results

Suppressing PP2A promoted ADR-induced decreases in PP2A expression, injury and apoptosis of MPC5 cells

With the aim to unveil the role of PP2A in podocytes injury in vitro, we first constructed an ADR-induced injury model in MPC5 podocytes in vitro and treated MPC5 podocytes with PP2A suppressor OA, and then measured PP2A expression. It was shown that following model construction, PP2A was downregulated, and PP2A suppressor OA further aggravated the effects on ADR of inhibiting PP2A expression (Fig. 1A, B, P < 0.01).

Fig. 1.

PP2A downregulation aggravated the effects of ADR on regulating PP2A and podocyte injury-related markers expressions and apoptosis of MPC5 cells. A, B Relative PP2A expression in mice podocyte MPC5 cells after ADR and OA treatment was measured by Western blot. GAPDH was used as an internal control. C, D Relative podocyte injury-related markers expressions in mice podocyte MPC5 cells after ADR and OA treatment were measured by Western blot. GAPDH was used as an internal control. E, F Relative apoptosis rate of mice podocyte MPC5 cells after ADR and OA treatment was measured by flow cytometry. All experiments have been performed in triplicate and data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). ***P < 0.001, vs. Blank; ^^P < 0.01, ^^^P < 0.001, vs. Model. PP2A protein phosphatase 2 A; ADR Adriamycin; OA okadaic acid, PP2A suppressor; WT1 Wilms’ tumor 1

As Nephrin, Desmin and Wilms’ tumor 1 (WT1) are podocytes injury-related markers (Zhang et al. 2017), we then measured their expressions after ADR and OA treatment. It was shown that after ADR treatment, Nephrin and WT1 expressions were decreased yet Desmin expression was increased, and OA further aggravated the effects of ADR on suppressing Nephrin and WT1 expressions but promoted Desmin expression in podocytes (Fig. 1C, D, P < 0.001).

By using flow cytometry, the effects of ADR and OA on podocytes apoptosis were determined, and we found that following ADR treatment, apoptosis rate was increased, and OA further enhanced the effects of ADR on promoting apoptosis of podocytes (Fig. 1E, F, P < 0.001). These results suggested that the suppression on PP2A might enhance the effects of ADR on suppressing PP2A expression and aggravating the podocytes injury in vitro.

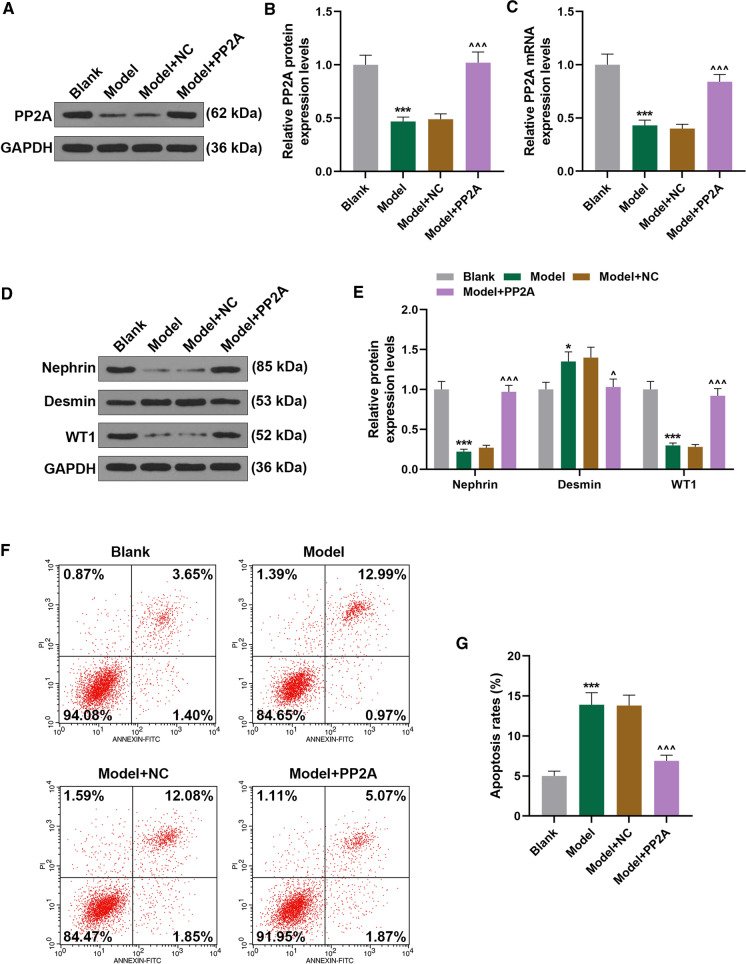

PP2A overexpression reversed the effects of ADR on PP2A and podocyte injury-related markers expressions and apoptosis of MPC5 cells

Then we transfected PP2A overexpression plasmid into ADR-treated podocytes to examine the possible effect of PP2A on podocytes. It was shown that ADR treatment downregulated PP2A expression, whereas PP2A overexpression upregulated PP2A expression in ADR-treated podocytes (Fig. 2A–C, P < 0.001). Also, podocyte injury-related markers expressions were measured, and we discovered that Desmin expression was upregulated yet Nephrin and WT1 expressions were downregulated following ADR treatment, whereas PP2A overexpression downregulated Desmin expression and upregulated Nephrin and WT1 expressions (Fig. 2D, E, P < 0.05). In addition, result from flow cytometry showed that ADR treatment promoted apoptosis of podocytes, while PP2A overexpression decreased apoptosis of ADR-treated podocytes (Fig. 2F, G, P < 0.001). Thus, it could be concluded that PP2A overexpression abolished the effects of ADR on both PP2A and podocytes injury in vitro.

Fig. 2.

PP2A overexpression reversed the effects of ADR on PP2A and podocyte injury-related markers expressions and apoptosis of MPC5 cells. A, B Relative PP2A protein expression in mice podocyte MPC5 cells after ADR treatment and PP2A overexpression was measured by Western blot. GAPDH was used as an internal control. C Relative PP2A mRNA expression in mice podocyte MPC5 cells after ADR treatment and PP2A overexpression was measured by qRT-PCR. GAPDH was used as an internal control. D, E Relative podocyte injury-related markers expressions in mice podocyte MPC5 cells after ADR treatment and PP2A overexpression was measured by Western blot. GAPDH was used as an internal control. F, G Relative apoptosis rate in mice podocyte MPC5 cells after ADR treatment and PP2A overexpression was measured by flow cytometry. All experiments have been performed in independent triplicate and data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, vs. Blank; ^P < 0.05, ^^^P < 0.001, vs. Model. qRT-PCR quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; NC negative control

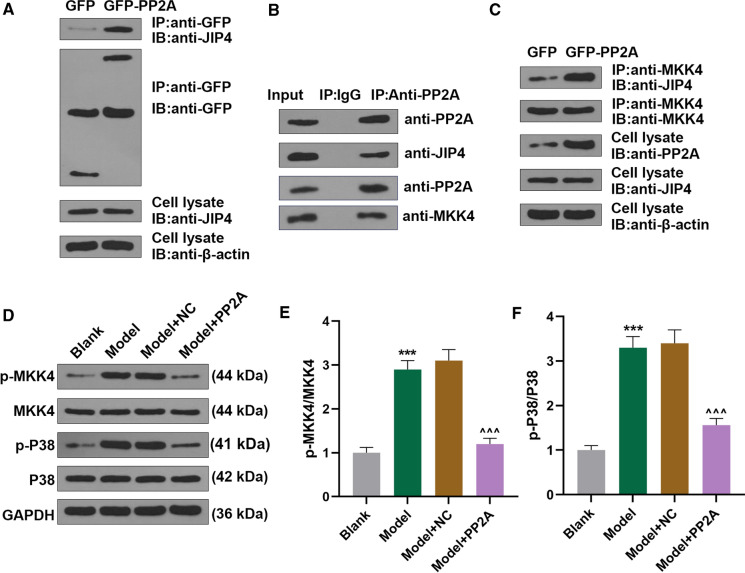

PP2A interacted with JIP4/p38-MAPK pathway in MPC5 cells, and PP2A overexpression reversed the effects of ADR on p38-MAPK pathway-related factors expressions in MPC5 cells

Previous study suggested that JIP4 could interact with p38-MAPK pathway, and MKK4 belongs to p38-MAPK pathway (Brys et al. 2020; Persak and Pitzschke 2013), but the interaction between JIP4 and PP2A needed to be further elucidated. Co-Ip assay was used to determine the interaction of PP2A, JIP4 and p38-MAPK pathway in podocytes. In our study, we found that JIP4 as the candidate could interact with PP2A, and PP2A also interact with MKK4 (Fig. 3A, B). In particular, PP2A overexpression promoted the binding between JIP4 and MKK4 (Fig. 3C).As MKK4 and p38 are two p38-MAPK pathway-related factors (Roy et al. 2018), their expressions in podocytes after ADR treatment and PP2A overexpression were measured. It was uncovered that following ADR treatment, both p-MKK4 and p-p38 expressions and p-MKK4/MKK4 and p-p38/p38 ratios were upregulated (Fig. 3D–F, P < 0.001). However, different effects were discovered after PP2A overexpression in ADR-treated podocytes (Fig. 3D–F, P < 0.001). From the results above, JIP4 could interact with PP2A, and PP2A overexpression reversed the effects of ADR on promoting JIP4/p38-MAPK in podocytes in vitro.

Fig. 3.

PP2A interacted with JIP4/p38-MAPK pathway in MPC5 cells, and PP2A overexpression reversed the effects of ADR on promoting p38-MAPK pathway activation in MPC5 cells. A–C Results from Co-Ip assay suggested that JIP4 as the candidate, which could both interact with PP2A andMKK4. D Relative protein expressions of p38-MAPK-pathway-related factors in mice podocyte MPC5 cells after ADR treatment and PP2A overexpression were detected using Western blot. GAPDH was used as internal control. Ratio of p-MKK4/MKK4 (E) and p-p38/p38 (F) was determined in mice podocyte MPC5 cells after ADR treatment and PP2A overexpression. All experiments have been performed in independent triplicate and data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). ***P < 0.001, vs. Blank; ^^^P < 0.001, vs. Model. Co-Ip co-immunoprecipitation; GFP green fluorescent protein; JIP4 JNK-interacting protein 4; IgG immunoglobin G; p-MKK4 phosphorylated-Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase Kinase 4

Silencing JIP4 reversed the promotive effects of PP2A downregulation on the phosphorylation of MKK4 and p38 in ADR-treated MPC5 cells

Then we transfected siJIP4 into podocytes after ADR and OA treatment, and found that after ADR treatment, both p-MKK4 and p-p38 expressions and p-MKK4/MKK4 and p-p38/p38 ratios were promoted, and that inhibiting PP2A further aggravated the effect of ADR (Fig. 4A–C, P < 0.01). However, silencing of JIP4 downregulated p-MKK4 and p-p38 expressions, reduced p-MKK4/MKK4 and p-p38/p38 ratios in ADR-treated podocytes, and reversed the effects of suppressed PP2A on both p-MKK4 and p-p38 expressions and p-MKK4/MKK4 and p-p38/p38 ratios (Fig. 4A–C, P < 0.01). Besides, PP2A expression was decreased in model group compared to blank group, which was further promoted by OA treatment; however, the effect of OA treatment was reversed by silencing of JIP4 (Fig. 4D, E, P < 0.01). We thus speculated that the inhibitory effects of PP2A on p38-MAPK pathway-related factors expressions in ADR-treated MPC5 cells were achieved via interacting with JIP4.

Fig. 4.

Silencing of JIP4 reversed the effects of PP2A downregulation on p38-MAPK pathway- and apoptosis-related factors expressions and apoptosis in ADR-treated MPC5 cells. A Relative protein expressions of p38-MAPK-pathway-related factors in ADR-treated mice podocyte MPC5 cells after PP2A suppression and silencing of JIP4 were detected using Western blot. GAPDH was used as internal control. B, C Ratio of p-MKK4/MKK4 and p-p38/p38 was determined in ADR-treated mice podocyte MPC5 cells after PP2A suppression and silencing JIP4. D, E The expression of PP2A was detected using Western blot. F, G Relative podocyte injury-related markers expressions in ADR-treated mice podocyte MPC5 cells after PP2A suppression and silencing of JIP4 was measured by Western blot. GAPDH was used as internal control. All experiments have been performed in independent triplicate and data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, vs. Blank; ^^P < 0.01, ^^^P < 0.001, vs. Model; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, vs. NC; ΔP < 0.05, ΔΔP < 0.01, ΔΔΔP < 0.001, vs. OA; ξP < 0.05, ξξP < 0.01, ξξξP < 0.001, vs. siJIP4. siJIP4 small interfering RNA targeting JIP4; Bcl-2 B-cell lymphoma 2; Bax Bcl-2 associated X protein; C-caspase-3 cleaved caspase-3

Silencing of JIP4 reversed the promotive effects of PP2A downregulation on injury and apoptosis of ADR-treated MPC5 cells

We additionally measured podocyte injury-related factors expressions in this phase, and found that following ADR treatment, Nephrin and WT1 expressions were downregulated yet Desmin expression was upregulated, and that PP2A downregulation further aggravated the effects of ADR (Fig. 4F, G, P < 0.01). However, after silencing of JIP4, the opposite results were discovered, and silencing of JIP4 further reversed the effects of PP2A downregulation on podocyte injury-related factors expressions in ADR-treated MPC5 cells (Fig. 4F, G, P < 0.01).

The effects of PP2A and JIP4 on podocyte apoptosis and apoptosis-related factors expressions were also determined using both flow cytometry and Western blot. We found that ADR promoted apoptosis and upregulated Bcl-2 associated X protein (Bax) and Cleaved (C)-caspase-3 expressions yet suppressed that of B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) in podocytes, and PP2A downregulation further aggravated the effects (Fig. 5A–E, P < 0.01). Contrary results were unveiled following silencing JIP4, and silencing of JIP4 additionally reversed the effects of PP2A downregulation in ADR-treated podocytes (Fig. 5A–E, P < 0.05). From the aforementioned results, we assumed that JIP4 might be implicated in the mechanism via which suppression of PP2A elicited its effects on podocyte injury-related factors expressions and apoptosis in ADR-treated MPC5 cells.

Fig. 5.

Silencing of JIP4 reversed the effects of suppressing PP2A on EMT-related factors expression in ADR-treated MPC5 cells. A, B Relative apoptosis rate in ADR-treated mice podocyte MPC5 cells after PP2A suppression and silencing of JIP4 was measured by flow cytometry. C–E Relative expressions of apoptosis-related factors in ADR-treated mice podocyte MPC5 cells after PP2A suppression and silencing JIP4 were measured using qRT-PCR and Western blot. GAPDH was used as internal control. F Relative mRNA expressions of EMT-related factors in ADR-treated mice podocyte MPC5 cells after PP2A suppression and silencing of JIP4 was quantified using qRT-PCR. GAPDH was used as an internal control. G, H Relative protein expressions of EMT-related factors in ADR-treated mice podocyte MPC5 cells after PP2A suppression and silencing of JIP4 was quantified using Western blot. GAPDH was used as internal control. All experiments have been performed in independent triplicate and data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, vs. Blank; ^^P < 0.01, ^^^P < 0.001, vs. Model; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, vs. NC; ΔP < 0.05, ΔΔP < 0.01, ΔΔΔP < 0.001, vs. OA; ξP < 0.05, ξξP < 0.01, ξξξP < 0.001, vs. siJIP4. EMT epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

Silencing JIP4 reversed the promotive effects of PP2A downregulation on epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in ADR-treated MPC5 cells

As EMT was a process related to podocyte injury, we subsequently measured the expressions of EMT-related factors, including E-cadherin, N-cadherin, Vimentin and Snail (Jaca et al. 2017; Li et al. 2015). It was discovered that following ADR treatment, E-cadherin expression was downregulated but N-cadherin, Vimentin and Snail expressions were upregulated (Fig. 5F–H, P < 0.05). PP2A downregulation further aggravated the effects of ADR, whereas silencing of JIP4 was the opposite (Fig. 5F–H, P < 0.01). In addition, in ADR-treated podocytes, silencing JIP4 reversed the effects of PP2A downregulation on EMT-related factors expressions (Fig. 5F–H, P < 0.05). It could be thus summarized from the results above that JIP4 might have an interaction with PP2A in the EMT process of ADR-treated MPC5 cells.

PP2A downregulation influenced injury-related markers and apoptosis of ADR-treated MPC5 cells via p38-MAPK

p38 MAP kinase-specific inhibitors SB203580 not only decreased the level of p-P38/P38, but also reversed the promotive effect of PP2A downrgulation on p-P38/P38 level (Fig. 6A and B, P < 0.001). Besides, SB203580 also reversed the regulatory effect of PP2A downrgulation on the expressions of Nephrin, Desmin, and WT1 (Fig. 6C and D, P < 0.05), as well as apoptosis rate (Fig. 6E and F, P < 0.01).in ADR-treated MPC5 cells.

Fig. 6.

PP2A downregulation influenced injury-related markers and apoptosis of ADR-treated MPC5 cells via p38-MAPK. A–D The protein levels of p-P38 and P38, injury-related markers (Nephrin, Desmin and WT1) were detected by Western blot. GAPDH was used as internal control. E, F Relative apoptosis rate in ADR-treated mice podocyte MPC5 cells after PP2A suppression and SB203580 was measured by flow cytometry. ^^P < 0.01, ^^^P < 0.001, vs. Model; ΔP < 0.05, ΔΔP < 0.01, ΔΔΔP < 0.001, vs. OA; ξξP < 0.01, ξξξP < 0.001, vs. SB203580. SB203580, p38 MAP kinase-specific inhibitors. All experiments have been performed in independent triplicate and data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD)

Discussion

Podocytes are an integral part of the glomerular barrier which prevents proteinuria (Li et al. 2020). Podocytes are key targets of injury in proteinuric glomerular diseases, which cause podocyte loss, progressive focal segmental glomerular sclerosis (FSGS) and even renal failure (Raij et al. 2016). As a member of PPPs family, PP2A have been found in several malignancies (Cristóbal et al. 2017; Enjoji et al. 2018; Nader et al. 2019). In our study, we discovered that PP2A was downregulated in ADR-treated podocytes, and that suppressing PP2A further aggravated the effects of ADR on podocytes.

Previous studies have pointed out the interaction between podocyte injury and ADR-induced nephropathy (Liu et al. 2017; Romoli et al. 2018; Yi et al. 2017). Several markers, including Nephrin, Desmin and WT1, are seen as podocyte injury-related markers (Zhang et al. 2017). Nephrin acts as a urine marker of podocyte dysfunction reflecting the integrity of kidney filtration barrier, and is a central component of formation and maintenance of the slit diaphragm in podocytes (Akankwasa et al. 2018; Martin and Jones 2018). Desmin is another podocyte injury marker upregulated in glomeruli when hyper-uricemic rats exhibited significance on albuminuria increase (Asakawa et al. 2017). WT1, which is a Wilms’ tumor suppressor gene, could encode a zinc finger protein with regulatory effects on podocyte development and is upregulated in mature podocytes, and mutation in WT1 gene is related to renal failure development for scar tissue formation within glomeruli (Asfahani et al. 2018). It has been pointed out that ADR downregulated Nephrin and WT1 expressions yet upregulated Desmin expression in podocytes (Zhang et al. 2017). In our current study, a same result was found, whereas PP2A overexpression exerted opposite effects, showing that ADR can aggravate podocyte injury in vitro, but this was attenuated by PP2A overexpression.

In addition, CKDs are caused by a direct consequence of initial dysfunction and injury to glomerular filtration barrier, which consists of podocytes, along with glomerular basement membrane and endothelial cells (Mallipattu and He 2016). Also, apoptosis of podocytes is a major mechanism resulting in proteinuria in multiple CKDs, and Bcl-2, Bax, and C-caspase-3 are recognized as apoptosis-associated factors (Dolka et al. 2016; Huang et al. 2016). Bcl-2 is an apoptosis-suppressive protein, while Bax could commit cells to its programmed death via permeabilization on outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) and succeeding initiation on caspase cascade (Edlich 2018; Zhang et al. 2020). C-caspase-3, located in both cytoplasm and nuclei of renal glomeruli, is another apoptosis marker (Huang et al. 2017). Prior study showed that ADR can upregulate Bax and C-caspase-3 expressions (Ni et al. 2018). In our study, we additionally found that ADR upregulated Bax and C-caspase-3 expressions, and downregulated Bcl-2 expression in podocytes, with increased number of apoptotic podocytes, while PP2A downregulation further aggravated the effects, showing that PP2A overexpression could alleviate ADR-induced nephropathy through reducing podocyte apoptosis.

According to the severity and duration of factors associated with injury, podocyte may undergo EMT, a process of reverse embryogenesis which occurs under multiple pathological conditions in organs and diseased kidneys (Chen et al. 2019b; Loeffler and Wolf 2014). Several factors are implicated in the process. E-Cadherin and N-Cadherin are two members belonging to the Cadherin family, and EMT is characterized by loss of the epithelial marker E-cadherin and gaining the mesenchymal marker N-cadherin (Pal et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2017). Vimentin is also a positive regulator of EMT and Vimentin upregulation is a prerequisite for EMT (Strouhalova et al. 2020). In addition, Snail promotes EMT promoter via directly inhibiting epithelial morphology (Muqbil et al. 2014). In our study, for the first time, we discovered that ADR possibly promoted EMT of podocytes, with downregulation of E-cadherin and upregulation of N-cadherin, Vimentin and Snail in podocytes, and suppressing PP2A enhanced the effects. Thus, we assumed that PP2A overexpression may alleviate ADR-induced nephropathy through inhibiting EMT.

JIP4 is one of the adaptors required for cargo recruitment via dynein/dynacin and kinesin 1 motors and are dimers stabilized by sections of leucine zipper coiled coils (Vilela et al. 2019). JIP4 and its downstream p38-MAPK pathway have been studied in previous publications (Pinder et al. 2015; Tanaka et al. 2014; Willett et al. 2017). P38 kinases are a group of MAPKs, and MKK4 is one of the upstream MAPK kinases for MAPK activation (Chen et al. 2019a; Su et al. 2017). It has been suggested that p38-MAPK pathway is implicated in CKDs as well (Lee et al. 2019). However, the interaction between PP2A and JIP4/p38-MAPK in ADR-induced nephropathy should be further elucidated. In our study, we confirmed that JIP4 interacted with PP2A, and suppressing PP2A further aggravated the effects of ADR on phosphorylation of MKK4 and p38 in ADR-treated podocytes. In addition, silencing of JIP4 reversed the effects of PP2A suppression in ADR-treated podocytes, showing that the effects of PP2A on ADR-treated podocytes can possibly be achieved via suppressing JIP4/p38-MAPK pathway.

The DNA damage checkpoint is a molecular mechanism that restrains cell cycle progression to avoid the segregation of the duplicated chromosomes until the broken DNA has been restored (Ramos et al. 2019). Thus, DNA damage checkpoint will be activated during DNA damage. Once the DNA damage checkpoint has been activated, PP2A also cooperates in its maintenance by dephosphorylating and inhibiting Polo-like kinase 1, a positive regulator of the G2/M transition, thereby stimulating a G2 arrest (Ramos et al. 2019). Therefore, DNA damage checkpoint do not down-modulates PP2A A subunit expression, because the activation of DNA damage checkpoint lies on PP2A’s function. In addition, the anti-apoptotic effect of PP2A is not limited to DNA-damage-driven apoptosis. For example, PP2A also exerts its anti-apoptotic effect on ROS-damage-driven apoptosis (Wu et al. 2019).

There are some other limitations in our current study that should be noted. We centered on the role of PP2A and its interaction with downstream target JIP4/p38-MAPK pathway in ADR-treated podocytes in vitro, but the effects in vivo needed to be addressed in detail. Future studies are urgently required. Besides, the inherent limitation of the study design wast that we only showed Co-IP data from HEK293 transfectants. Co-IP experiments with MPC5 cells may be helpful to show direct in vivo interactions.

In conclusion, in our current study, we found that PP2A expression was downregulated in ADR-treated podocytes, and PP2A overexpression reversed the effects of ADR on regulating PP2A and podocyte injury-related markers expressions and apoptosis as well as EMT of podocytes, which was achieved via JIP4/p38-MAPK pathway. Our study provides a piece of novel evidence on the role of PP2A in ADR-induced podocytes injury, and we hope that our study can help provide possible therapeutic methods for prevention and treatment of ADR-caused nephropathy in clinical practice in the future.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Research and Development Plan of Zhejiang Province [2019C03028]; the National Natural Foundation of China [81770710].

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Akankwasa G, Jianhua L, Guixue C, Changjuan A, Xiaosong Q. Urine markers of podocyte dysfunction: a review of podocalyxin and nephrin in selected glomerular diseases. Biomark Med. 2018;12:927–935. doi: 10.2217/bmm-2018-0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakawa S, et al. Podocyte injury and albuminuria in experimental hyperuricemic model rats. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:3759153. doi: 10.1155/2017/3759153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asfahani RI, et al. Activation of podocyte Notch mediates early Wt1 glomerulopathy. Kidney Int. 2018;93:903–920. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskaran R, Velmurugan BK. Protein phosphatase 2A as therapeutic targets in various disease models. Life Sci. 2018;210:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2018.08.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brys R, Gibson K, Poljak T, Van Der Plas S, Amantini D. Discovery and development of ASK1 inhibitors. Prog Med Chem. 2020;59:101–179. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmch.2020.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, et al. Autophagy and doxorubicin resistance in cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 2018;29:1–9. doi: 10.1097/cad.0000000000000572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Nelson LJ, Ávila MA, Cubero FJ. Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and cholangiocarcinoma: the missing link. Cells. 2019 doi: 10.3390/cells8101172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Lin L, Tao X, Song Y, Cui J, Wan J. The role of podocyte damage in the etiology of ischemia-reperfusion acute kidney injury and post-injury fibrosis. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20:106. doi: 10.1186/s12882-019-1298-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristóbal I, Torrejón B, Martínez-Useros J, Madoz-Gurpide J, Rojo F, García-Foncillas J. PP2A regulates signaling through hormonal receptors in breast cancer with important therapeutic implications. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017;1868:435–438. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolka I, Król M, Sapierzyński R. Evaluation of apoptosis-associated protein (Bcl-2, Bax, cleaved caspase-3 and p53) expression in canine mammary tumors: an immunohistochemical and prognostic study. Res Vet Sci. 2016;105:124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlich F. BCL-2 proteins and apoptosis: recent insights and unknowns. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;500:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.06.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enjoji S, et al. Stemness is enhanced in gastric cancer by a SET/PP2A/E2F1 axis. Mol Cancer Res MCR. 2018;16:554–563. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.mcr-17-0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Zheng Q, Shao Y, Wang W, Zhao C. CD155 downregulation synergizes with adriamycin to induce breast cancer cell apoptosis. Apoptosis Int J Program Cell Death. 2018;23:512–520. doi: 10.1007/s10495-018-1473-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassock RJ, Warnock DG, Delanaye P. The global burden of chronic kidney disease: estimates, variability and pitfalls. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13:104–114. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2016.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, et al. Cdc42 deficiency induces podocyte apoptosis by inhibiting the Nwasp/stress fibers/YAP pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2142. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SS, et al. Resveratrol protects podocytes against apoptosis via stimulation of autophagy in a mouse model of diabetic nephropathy. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45692. doi: 10.1038/srep45692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaca A, Govender P, Locketz M, Naidoo R. The role of miRNA-21 and epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) process in colorectal cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2017;70:331–356. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2016-204031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauko O, Westermarck J. Non-genomic mechanisms of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) regulation in cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2018;96:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, An JN, Hwang JH, Lee H, Lee JP, Kim SG. p38 MAPK activity is associated with the histological degree of interstitial fibrosis in IgA nephropathy patients. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0213981. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Li CX, Xia M, Ritter JK, Gehr TW, Boini K, Li PL. Enhanced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition associated with lysosome dysfunction in podocytes: role of p62/Sequestosome 1 as a signaling hub. Cell Physiol Biochem Int J Exp Cell Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2015;35:1773–1786. doi: 10.1159/000373989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, et al. JLP-JNK signaling protects cancer cells from reactive oxygen species-induced cell death. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;501:724–730. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Guan XM, Wang RY, Xie YS, Zhou H, Ni WJ, Tang LQ. Berberine mitigates high glucose-induced podocyte apoptosis by modulating autophagy via the mTOR/P70S6K/4EBP1 pathway. Life Sci. 2020;243:117277. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Luo L, Shi W, Yin Y, Gao S. Ursolic acid reduces Adriamycin resistance of human ovarian cancer cells through promoting the HuR translocation from cytoplasm to nucleus. Environ Toxicol. 2021;36:267–275. doi: 10.1002/tox.23032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, et al. Sirt6 deficiency exacerbates podocyte injury and proteinuria through targeting Notch signaling. Nat Commun. 2017;8:413. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00498-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, et al. Leonurine ameliorates adriamycin-induced podocyte injury via suppression of oxidative stress. Free Radic Res. 2018;52:952–960. doi: 10.1080/10715762.2018.1500021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods (San Diego, Calif) 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeffler I, Wolf G. Transforming growth factor-β and the progression of renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transpl Off Publ Eur Dial Transpl Assoc Eur Ren Assoc. 2014;29:i37–i45. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo R, Yang K, Wang F, Xu C, Yang T. (Pro)renin receptor decoy peptide PRO20 protects against adriamycin-induced nephropathy by targeting the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2020;319:F930–F940. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00279.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma F, Wang SH, Cai Q, Zhang MD, Yang Y, Ding J. Overexpression of LncRNA AFAP1-AS1 predicts poor prognosis and promotes cells proliferation and invasion in gallbladder cancer. Biomed Pharmacother = Biomedecine pharmacotherapie. 2016;84:1249–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallipattu SK, He JC. The podocyte as a direct target for treatment of glomerular disease? Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2016;311:F46–F51. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00184.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CE, Jones N. Nephrin signaling in the podocyte: an updated view of signal regulation at the slit diaphragm and beyond. Front Endocrinol. 2018;9:302. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muqbil I, Wu J, Aboukameel A, Mohammad RM, Azmi AS. Snail nuclear transport: the gateways regulating epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition? Semin Cancer Biol. 2014;27:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader CP, Cidem A, Verrills NM, Ammit AJ. Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A): a key phosphatase in the progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) to lung cancer. Respir Res. 2019;20:222. doi: 10.1186/s12931-019-1192-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Y, et al. Plectin protects podocytes from adriamycin-induced apoptosis and F-actin cytoskeletal disruption through the integrin α6β4/FAK/p38 MAPK pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22:5450–5467. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal M, Bhattacharya S, Kalyan G, Hazra S. Cadherin profiling for therapeutic interventions in Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) and tumorigenesis. Exp Cell Res. 2018;368:137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2018.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persak H, Pitzschke A. Tight interconnection and multi-level control of Arabidopsis MYB44 in MAPK cascade signalling. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinder A, Loo D, Harrington B, Oakes V, Hill MM, Gabrielli B. JIP4 is a PLK1 binding protein that regulates p38MAPK activity in G2 phase. Cell Signal. 2015;27:2296–2303. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raij L, Tian R, Wong JS, He JC, Campbell KN. Podocyte injury: the role of proteinuria, urinary plasminogen, and oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2016;311:F1308–F1317. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00162.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos F, Villoria MT, Alonso-Rodríguez E, Clemente-Blanco A. Role of protein phosphatases PP1, PP2A, PP4 and Cdc14 in the DNA damage response. Cell Stress. 2019;3:70–85. doi: 10.15698/cst2019.03.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynhout S, Janssens V. Physiologic functions of PP2A: lessons from genetically modified mice. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2019;1866:31–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2018.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romoli S, et al. CXCL12 blockade preferentially regenerates lost podocytes in cortical nephrons by targeting an intrinsic podocyte-progenitor feedback mechanism. Kidney Int. 2018;94:1111–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roomi MW, Kalinovsky T, Roomi NW, Rath M, Niedzwiecki A. Prevention of Adriamycin-induced hepatic and renal toxicity in male BALB/c mice by a nutrient mixture. Exp Ther Med. 2014;7:1040–1044. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S, Roy S, Rana A, Akhter Y, Hande MP, Banerjee B. The role of p38 MAPK pathway in p53 compromised state and telomere mediated DNA damage response. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen. 2018;836:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2018.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strouhalova K, Přechová M, Gandalovičová A, Brábek J, Gregor M, Rosel D. Vimentin intermediate filaments as potential target for cancer treatment. Cancers. 2020 doi: 10.3390/cancers12010184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su J, et al. Regulation of stomatal immunity by interdependent functions of a pathogen-responsive MPK3/MPK6 cascade and abscisic acid. Plant Cell. 2017;29:526–542. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Iino M, Goto K. Knockdown of Sec8 enhances the binding affinity of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-interacting protein 4 for mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 (MKK4) and suppresses the phosphorylation of MKK4, p38, and JNK, thereby inhibiting apoptosis. FEBS J. 2014;281:5237–5250. doi: 10.1111/febs.13063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Z, Takahashi Y. Analysis of protein–protein interaction by Co-IP in human cells. Methods Mol Biol (Clifton, NJ) 2018;1794:289–296. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7871-7_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taskin E, et al. Silencing HMGB1 expression inhibits adriamycin’s heart toxicity via TLR4 dependent manner through MAPK signal transduction. J BUON Off J Balk Union Oncol. 2020;25:554–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobisawa T, et al. Insufficient activation of Akt upon reperfusion because of its novel modification by reduced PP2A-B55α contributes to enlargement of infarct size by chronic kidney disease. Basic Res Cardiol. 2017;112:31. doi: 10.1007/s00395-017-0621-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilela F, et al. Structural characterization of the RH1-LZI tandem of JIP3/4 highlights RH1 domains as a cytoskeletal motor-binding motif. Sci Rep. 2019;9:16036. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52537-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang DX, et al. Sulforaphane suppresses EMT and metastasis in human lung cancer through miR-616-5p-mediated GSK3beta/beta-catenin signaling pathways. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2017;38:241–251. doi: 10.1038/aps.2016.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett R, Martina JA, Zewe JP, Wills R, Hammond GRV, Puertollano R. TFEB regulates lysosomal positioning by modulating TMEM55B expression and JIP4 recruitment to lysosomes. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1580. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01871-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu SY, et al. Penfluridol triggers cytoprotective autophagy and cellular apoptosis through ROS induction and activation of the PP2A-modulated MAPK pathway in acute myeloid leukemia with different FLT3 statuses. J Biomed Sci. 2019;26:63. doi: 10.1186/s12929-019-0557-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi M, et al. Autophagy is activated to protect against podocyte injury in adriamycin-induced nephropathy. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2017;313:F74–F84. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00114.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, et al. mPGES-1-derived PGE2 contributes to adriamycin-induced podocyte injury. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2016;310:F492–F498. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00499.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Ren R, Du J, Sun T, Wang P, Kang P. AF1q contributes to adriamycin-induced podocyte injury by activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2017;42:794–803. doi: 10.1159/000484329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Fang J, Zhang J, Ding S, Gan D. Curcumin inhibited podocyte cell apoptosis and accelerated cell autophagy in diabetic nephropathy via regulating Beclin1/UVRAG/Bcl2. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes Targets Ther. 2020;13:641–652. doi: 10.2147/dmso.s237451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, et al. Protein phosphatase 2A modulates podocyte maturation and glomerular functional integrity in mice. Cell Commun Signal. 2019;17:91. doi: 10.1186/s12964-019-0402-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]