Abstract

Background and Aims

Multi‐stakeholder partnerships offer strategic advantages in addressing multi‐faceted issues in complex, fast‐paced, and rapidly‐evolving community health contexts. Synergistic partnerships mobilize partners' complementary financial and nonfinancial resources, resulting in improved outcomes beyond that achievable through individual efforts. Our objectives were to explore the manifestations of synergy in partnerships involving stakeholders from different organizations with an interest in implementing organizational solutions that enhance access to primary health care (PHC) for vulnerable populations, and to describe structures and processes that facilitated the work of these partnerships.

Methods

This was a longitudinal case study in two Canadian provinces of two collaborative partnerships involving decision makers, academic representatives, clinicians, health system administrators, patient partners, and representatives of health and social service organizations providing services to vulnerable populations. Document review, nonparticipant observation of partnerships' meetings (n = 14) and semi‐structured in‐depth interviews (n = 16) were conducted between 2016 and 2018. Data analysis involved a cross‐case synthesis to compare the cases and framework analysis to identify prominent themes.

Results

Four major themes emerged from the data. Partnership synergy manifested itself in the following: (a) the integration of resources, (b) partnership atmosphere, (c) perceived stakeholder benefits, and (d) capacity for adaptation to context. Synergy developed before the intended PHC access outcomes could be assessed and acted both as a dynamic indicator of the health of the partnership and a source of energy fuelling partnership improvement and vitality. Synergistic action among multiple stakeholders was achieved through enabling processes at interpersonal, operational, and system levels.

Conclusions

The partnership synergy framework is useful in assessing the intermediate outcomes of ongoing partnerships when it is too early to evaluate the achievement of long‐term intended outcomes. Enabling processes require attention as part of routine partnership assessment.

Keywords: health system improvement, organizational transformation, partnership synergy, partnerships, primary health care

1. INTRODUCTION

In the environment of increasing demands and limited resources, rapid technological change, and an aging and progressively complex patient population, partnerships involving multiple stakeholders from different sectors offer a meaningful way of tackling complex health care system problems.1, 2, 3, 4 Multi‐stakeholder partnerships including community members and representatives of academic institutions are prevalent across multiple disciplines and spheres.5 To a certain extent, this can be attributed to the role of governments and funding agencies that mandate partnerships as an essential element of the programs and initiatives that they support.4, 5 For example, the Canadian Government has promoted collaboration as a means of improving the quality of health care provided to the Canadian population.6 The partnership approach to health care system change and service redesign has also enjoyed widespread endorsement in other countries, particularly within the context of health and welfare services.4, 7

Partnership benefits have been studied from a diverse range of perspectives, disciplines, and communities of practice.8, 9 Academic literature outlines what constitutes an effective partnership and describes approaches and strategies to enhance partnership processes and to increase partnership effectiveness.5, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 In theory, effective partnerships can be useful for overcoming organizational fragmentation and traditional divisions of power, improving communication and access to information, optimizing resource utilization, and helping to avoid a wasteful duplication of effort.16 In addition, there is evidence to suggest that effective partnerships contribute to more comprehensive interventions, help to contextualize policy, and support the feasibility and relevance of research through direct involvement of knowledge users.1, 16, 17 In primary health care (PHC), cross‐sector partnerships have been used to ensure integrated service delivery.18 Reported facilitating processes include capitalizing on the diverse perspectives of partners, pooling of resources, promoting a common understanding of issues, forging common action plans, ensuring joint accountability and evaluation of progress, and employing appropriate forms of leadership and coordinating activities to ensure the alignment of efforts.3, 19

In practice, however, partnerships are frequently unable to generate effective collaborative advantage and achieve the intended change in systems and/or health outcomes.19, 20 Many crumble under challenges such as insufficient resources, significant time commitments, conflicting interests, problems with governance and leadership, lack of necessary skills, insufficient recognition, and lack of buy‐in from key stakeholders.2, 5, 19, 21 Considering these challenges, there is a growing need for evidence demonstrating the link between the implementation of processes and approaches that are claimed to enhance partnership effectiveness and the achievement of intended outcomes.

The notion of “partnership synergy” has been proposed as a marker or a “proximal outcome” of partnership functioning.4 (p182) Partnerships are said to be synergistic when they combine resources successfully and mobilize the complementary knowledge and expertise of all the partners.22 Synergy is reached when the combined efforts of partners enhance the outcomes beyond what could be achieved independently by each stakeholder/stakeholder group working toward the same goals,23 namely that the whole becomes greater than the sum of the parts.4 Synergy could manifest itself through creative and holistic ways of thinking, the ability to carry out more comprehensive interventions aimed at target populations, the relationships between partners and relationships of partnerships with the broader community.4 Lasker et al identified a number of elements of partnership functioning that are likely to influence partnership synergy (Table 1) and suggested looking at synergy as a predictor of an effective partnership.4 Subsequent research conceptualized synergy as being both a process and a product of partnership, and highlighted the dynamic and cumulative nature of partnership synergy demonstrating its capacity to build over time and its role as an evolving indicator of effectiveness and sustainability.23, 24, 25

TABLE 1.

Determinants of partnership synergy (adapted from Reference 4)

| Determinants of partnership synergy | Factors likely to influence partnership synergy |

|---|---|

| Resources | Money |

| Space, equipment, goods | |

| Skills and expertise | |

| Information | |

| Connections to people, organizations, groups | |

| Endorsements | |

| Convening power | |

| Partner characteristics | Heterogeneity |

| Level of involvement | |

| Relationships among partners | Trust |

| Respect | |

| Conflict | |

| Power differentials | |

| Partnership characteristics | Leadership |

| Administration and management | |

| Governance | |

| Efficiency | |

| External environment | Community characteristics |

| Public and organizational policies |

This study adopted partnership synergy as an umbrella framework for looking at the functioning of two multi‐stakeholder partnerships in two Canadian provinces involving stakeholders from different organizations and constituent groups with an interest in implementing organizational solutions to enhance access to appropriate PHC for vulnerable populations. The overall aim of our study was to gain an in‐depth understanding of the effectiveness of multi‐stakeholder partnerships in addressing complex issues in PHC. PHC is conceptualized here as an approach to health that encompasses continuous and comprehensive care across diverse curative, preventative, education, and rehabilitation services, with a person (micro), community (meso), and population (macro) orientation.26, 27, 28 For the purposes of this paper, we conceptualize “partnership effectiveness” in relation to both the processes and outcomes of partnerships: the quality of the processes and relationships between partners and the health of the partnership on the one hand, and the realization of intended outcomes on the other. We define a multi‐stakeholder partnership as a complex human system based on voluntary collaborative relationships among stakeholders who agree to work together to achieve a common purpose and to share competencies, resources, responsibilities, risks, and benefits (adapted from Reference 29). We focused on partnerships involving representatives of different organizations—each bringing their unique perspectives, competencies, organizational mandates, interests and weaknesses, working toward a common goal of transforming PHC service delivery. The main research questions that this study attempted to address were as follows: (a) How does partnership synergy manifest itself in multi‐stakeholder partnerships? and (b) What structures and processes are required to build synergistic action among actors from different sectors?

2. METHODS

2.1. Study context

This study was undertaken within a Canada‐Australia research program entitled “Innovative Models Promoting Access‐to‐Care Transformation” (IMPACT) conducted between 2013 and 2018.30 The aim of this program was to design, implement, and evaluate, through a network of local partnerships, organizational interventions to improve access to appropriate PHC for vulnerable populations in three Australian states (Victoria, South Australia, and New South Wales) and three Canadian provinces (Quebec, Ontario, and Alberta).30 Each of the six projects entailed identifying, in consultation with a broader set of local stakeholders, PHC access needs, and selecting, adapting, and implementing coordinated actions to best address these needs, within available resources. This study focused on two of the Canadian IMPACT local partnerships, namely the Primary Care Connection Partnership (PCCP) and the Community Health Resources Partnership (CHRP) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Overview of interventions in two Canadian IMPACT local partnerships (adapted from References 30, 31, 32)

| Partnership title | Primary Care Connection | Community Health Resources |

|---|---|---|

| Target population and access problem | Unattached patients in high deprivation neighborhoods have trouble connecting effectively to newly assigned family physicians from centralized wait list. | Primary care patients with complex health and social needs not receiving available community services (eg, smoking cessation, falls prevention, etc) that would optimize their illness management. |

| Type of vulnerability | Low income, unemployment, low social support. | Socially complex patients, including one of Canada' linguistic minorities. |

| Intervention | Volunteer guides discuss the health and social needs of patients before their first appointment with a family physician. | Lay, bilingual navigators integrated into primary care practices support patients to reach community resources. |

| Tasks | Develop the intervention, in collaboration with regional health organizations that manage a centralized waiting list for family physicians; obtain consent from primary care practices to contact assigned patients; recruit patients; develop relevant materials; recruit and train lay volunteer navigators; lay volunteer navigators reach out by telephone to patients in materially or socially deprived neighborhoods prior to the first visit to a newly assigned family physician; evaluate the intervention. | Develop the intervention; recruit primary care practices and patients; prepare relevant materials; assist practices in making adaptations in the electronic medical record system to allow referral to navigation services; orient providers regarding the availability and potential benefits of community resources; recruit and train a lay navigator in patient‐centered communication and system navigation; lay navigator works with patients to prioritize needs, identify potential barriers to access, and facilitate access to services; evaluate the intervention. |

| Intended consequence | Successful affiliation to a family physician. | Increased referrals to community health resources and improved access to these services. |

Abbreviation: PHC ‐ primary health care.

The stakeholders within each partnership included a mix of decision makers, clinicians, health system administrators, service providers, academic members—composed of academic investigators, including principal investigators and co‐investigators, and research coordinators, and, in some cases, members of vulnerable populations.30 Vulnerable populations were “community members whose demographic, geographic, economic and/or cultural characteristics impeded or compromised their access to PHC.”30 (p4)

2.2. Study design

This longitudinal case study33, 34 involved document review, nonparticipant observation35 of partnerships' meetings, and semi‐structured in‐depth interviews36 with a sample of study stakeholders in two partnerships. The study was conducted between August 2016 and September 2018. The rationale for studying both cases longitudinally was to follow their development over time, to understand the evolution of processes, to trace any changes that affected the partnerships, and identify how the partnerships responded to these changes. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) were used in the reporting of this study.37

2.3. Sampling and recruitment

The PCCP stakeholders represented two administrative jurisdictions covered by two regional health networks, two local general practice divisions, community development organizations serving the two neighborhoods, and two universities. The CHRP included stakeholders from one health authority, a university, community and home care services, social and public health services, community health centers, information resources, primary care, and the community.

Interview candidates were selected using purposive sampling with the aim to achieve maximum variation within the sample.38 The goal of the sampling strategy was to include representatives of each stakeholder group, who varied in seniority in the partnership and nature of engagement. The PCCP interview candidates were identified by the first author based on meeting observations; the CHRP candidates were identified by the CHRP principal investigator.

2.4. Data collection

Preliminary documents reviewed (between August 2016 and May 2017) were minutes of meetings, protocols, and reports produced by the IMPACT program and the two partnerships. The first author subsequently observed (between January 2017 and September 2018) 11 PCCP and three CHRP meetings—all available meetings that took place during this time frame. The document review and observations provided data on the operational elements, contextual factors, participants' roles and responsibilities, the common agenda of each initiative, and how this common agenda and the involvement of different stakeholders evolved since the start of the IMPACT research program in 2013. The first author then conducted (between July 2017 and March 2018) nine interviews with PCCP stakeholders and seven with CHRP stakeholders. Interview candidates were initially invited to participate via e‐mails that were sent by PCCP and CHRP research coordinators. Follow‐up contact by the first author was in person, at the end of partnership meetings, and via e‐mails sent directly to each candidate. The interviews lasted approximately 1 hour, were conducted either in‐person or over the telephone, and were audio‐recorded.

The interview guide (Appendix A) was developed with reference to the literature on partnership synergy.4, 25 Synergy dimensions explored included the organization of partnerships, work sharing, decision‐making/problem‐solving, complementarity of skills, outcomes, and experience. The guide was pilot tested, in both English and French, prior to administration.

2.5. Ethics

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the St Mary's Hospital Centre Research Ethics Committee (No. SMHC‐13‐30C). Authorization to conduct research was obtained from the second participating institution. All participants were provided with written information about the study and consent was obtained prior to data collection.

2.6. Data analysis

Nonparticipant observations (which entailed observing participants without actively participating in their meetings) were recorded as field notes. All interviews were transcribed verbatim, in the original language, with subsequent translation from French into English for quotation purposes. Our analysis of notes and transcripts reflected the dual‐level inquiry of the study: it involved a cross‐case synthesis to describe the cases and generate insights34 and framework analysis.39 The strategy used for data analysis involved a hybrid deductive‐inductive approach,39, 40 involving assigning data into predefined themes based on the partnership synergy framework, revising themes based on nuances within the data, and identifying new themes arising from the data. The data were coded iteratively, going back and forth from text to themes. NVivo 12 software was used to support data management and analysis. The material was analyzed by the first author. Coding was verified with another co‐author. Emerging findings were discussed at regular team meetings. The final codes were grouped along the dimensions of partnership synergy and six categories of factors likely to foster synergy: structure; partner characteristics; partnership characteristics; relationships among partners; resources; and external environment.

3. FINDINGS

The following paragraphs detail the key findings from this study. Section 3.1 presents the characteristics of the sample. Section 3.2 summarizes the key findings and refers to descriptive cross‐case synthesis (presented in Appendix B) that is based on observations and accounts of interview respondents. In Section 3.3 we elaborate on four themes that emerged from our data where partnership synergy was apparent, namely resource integration, partnership atmosphere, reported benefits, and partnership's capacity for adaptation to context. Finally, Section 3.4 describes partnership collaborative processes that enabled stakeholders from different organizations to achieve synergistic action.

3.1. Study participants

Interview participants represented a range of organizational expertise (Table 3). Academic representatives and decision makers constituted the largest two groups (n = 10, 63%). Participants (n = 16) were predominantly female (n = 13, 81%).

TABLE 3.

Study sample characteristics (n = 16)

| Characteristic | Primary Care Connection Partnership (PCCP) | Community Health Resources Partnership (CHRP) |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 9) | (n = 7) | |

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 8 (89%) | 5 (71%) |

| Male | 1 (11%) | 2 (29%) |

| Main role in the partnership | ||

| Academic representative: | ||

| Researcher | 1 (11%) | 1 (14%) |

| Research coordinator | 2 (22%) | 1 (14%) |

| Decision maker | 3 (33%) | 2 (29%) |

| Clinician/practitioner | 2 (22%) | 1 (14%) |

| Organizational representative/patient | 1 (11%) | 2 (29%) |

| Interview language | ||

| English | 0 (0%) | 7 (100%) |

| French | 9 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

3.2. Cross‐case synthesis

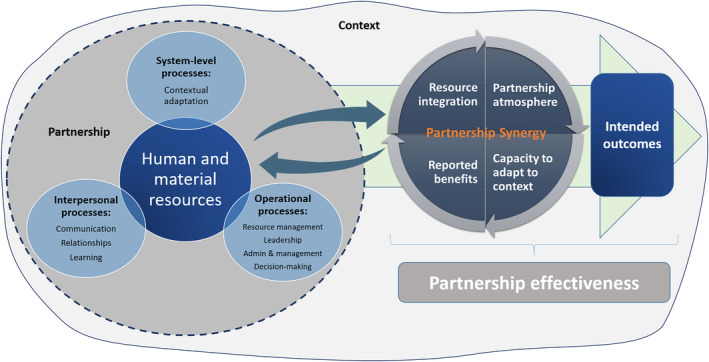

Our key findings are summarized in Figure 1. It portrays human and material resources as the building blocks of partnerships. These resources are then activated via interpersonal, operational, and system‐level processes to produce partnership synergy. Partnership synergy manifests itself in different ways: in the integration of resources, partnership atmosphere, perceived stakeholder benefits, and the capacity for adaptation to context. It acts as both a dynamic indicator of the health of the partnership, highlighting the likelihood of achieving partnership effectiveness, and as the source of energy fuelling partnership improvement and vitality. The boundaries of the partnership are permeable, reflecting the exchange of influence between the partnership and its context. Appendix B displays how the cases align against the partnership synergy framework and describes how the two partnerships were resourced and structured.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of key findings—relationships among partnership synergy, partnership resources, enabling partnership processes and outcomes

3.3. Partnership synergy

3.3.1. Theme 1: Resource integration

There was evidence of partnership synergy in the integration of nonfinancial and financial resources. Nonfinancial resources included the time, knowledge, expertise, and connections that the stakeholders contributed, as well as the relationships and learning that transpired in the course of partnership work. The partnerships demonstrated capacity to recruit stakeholders with a range of perspectives, skills, information, and connections to a broader set of stakeholders and health systems exerting influence over the partnerships. These unique perspectives and insights (Table 4) were deemed to be complementary in that they allowed the group to explore the issues of access from various angles, to obtain timely information from different sectors in order to adapt interventions, and to enhance the relevance of interventions: “I think it's a really good mix of people, and you can hear it in the discussion. The very different points of view and they all complement each other very well.” (016, CHRP).

TABLE 4.

Stakeholder perspectives within two Canadian IMPACT local partnerships

| Stakeholder group | Primary Care Connection Partnership (PCCP) | Community Health Resources Partnership (CHRP) | Perspective |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical practitioners | X | X | Clinical perspective, with one CHRP physician's practice being an incubator for the navigator model. |

| Decision makers and health planners | X | X | Bridge between researchers and policy‐making, ensuring that research activities aligned with and responded to health policy priorities and capabilities and, conversely, that health authorities were aware of research insights relevant to the project. |

| Academic investigators | X | X | Research knowledge and skills, including: organization of the research process; data gathering, analysis, and synthesis of information of relevance to the partnership; interface with funding bodies and larger IMPACT program. |

| Research coordinators | X | X | Coordination of partnership activities, group process facilitation. |

| Anglophone and francophone patient partners | X | The lived experience point of view, including insights regarding specific barriers experienced on the basis of languages spoken. | |

| Community organization representative | X | Insights into the challenges experienced by the target populations. | |

| Community service organizations | X | Information on available community services, ensuring that the research was grounded in reality: that project activities were aligned with the priorities and capabilities of these organizations. |

Abbreviation: IMPACT—Innovative Models Promoting Access‐to‐Care Transformation.

I honestly don't think that there's any other way to do it, because it's in primary care and primary care is incredibly complex, there are so many players involved […]. If we didn't have those other people at the table how would we know what's going on. (013, CHRP).

In both cases, the nucleus of the partnership, including the research team and a number of key nonacademic stakeholders, remained consistent over time, while new members were invited to join based on project evolution and the need to attract additional expertise and resources. This heterogeneity and fluidity in the composition of the partnerships reflected the complexity and scope of the tasks at hand, the dynamic nature of the projects and organizational and policy changes in the external context that took place over the years. These composition dynamics, however, necessitated a significant investment of coordination resources and time on the part of the research teams and ongoing attention to and management of stakeholder engagement dynamics.

The CHRP was larger, reflecting a broader array of stakeholders and language groups. Some CHRP interview participants felt that the size of the partnership (23 stakeholders) was too large, potentially inhibiting contribution from some members. The PCCP was smaller (13 members) but had the complexity of involving two independent health authorities, with different organizational cultures and authority structures, with one interview participant describing the partnership's initiative as “one research project […] with two different speeds” (011, PCCP). Despite the differences between cases in size and diversity, the mix of stakeholders in both was perceived by interviewees to be optimal for achieving project goals. The composition was described by stakeholders as an “excellent mixture of people […] from diverse sectors” (016, CHRP) and as “driven by the research team, but nourished by the practitioners in the field” (014, PCCP).

The partnerships demonstrated the ability to effectively combine their nonfinancial resources. In both cases, the level of engagement was deemed by most interview respondents to be appropriate for the stated project objectives and the function of the partnership. All stakeholders had clarity regarding their own roles and what was expected of them. Several participants referred to the alignment of efforts of partners and the richness and integrative nature of collaboration: “These [partnership] tables are an example of integration. […] We become more integrated and stronger, and there is a certain level of coherence between us.” (020, PCCP); “It is very rich. […] Not everyone has the same reality, and we inspire each other. In understanding the point of view of the other, we advance the discussion.” (014, PCCP).

Partnership synergy was also apparent in the ways partners leveraged financial resources and sustained partnership activities and interventions despite contextual challenges and funding gaps. The IMPACT research grant included funding for the coordinating infrastructure/research support, including the partnership coordinator position in each site, as well as the evaluation of interventions. There was no funding for intervention implementation, and stakeholders other than research coordinators were not remunerated for participation in partnership activities. Consequently, the successful implementation and sustainability of interventions relied entirely on the local players' capacity to commit to them, provide adequate resources, and maintain them beyond the life of the IMPACT research funding. Both partnerships devised low‐cost lay navigator models to address the needs of the target populations. Both worked toward integrating the interventions into existing health system organizational structures, aligning the proposed models with health system priorities. In the process, the CHRP relied on additional research funding that was secured early on in the project to support a randomized controlled trial to test the effectiveness of the developed navigator model.

3.3.2. Theme 2: Partnership atmosphere

Partnership synergy was apparent in the quality of stakeholder relationships, in the perceived value of the initiative, and the general partnership atmosphere, which was described as “positive” (011, 018, CHRP), “dynamic” (017, CHRP), “respectful” (019, CHRP), “open” (013, PCCP), “friendly” (015, CHRP), “collaborative,” “energising” and “engaging” (013, CHRP): “Everybody seems to be happy to be involved.” (018, CHRP); “I usually see it as we all come together, sort of. I don't feel a sense of that there's some difference between anyone […]. I feel like they do treat me as an equal.” (019, CHRP).

The exchanges are very open. That is to say, when we […] put forth a proposal or a possible solution, it is always well received … not necessarily always accepted, but well received. Lots of openness. That, I find that interesting. (013, PCCP).

These positive collaborative relationships benefitted the partnerships by enabling more open conversations, faster and effective decision‐making, and enhanced project ownership: “The commitment to the project is higher when you have built it together. […] When you have done it in collaboration, it is closer to your heart and I think that this is one of the advantages.” (012, PCCP).

The synergy in relationships blossomed with time; as the work progressed, participants felt that they could speak more openly, including voicing concerns and disagreement:

I have the impression that we are less afraid of losing our partners, we walk less on eggshells, we are more open […] the partnership is a little more solid and we are more capable of […] exposing a little, being less artificial in our meetings. (011, PCCP).

Participants highlighted the importance of face‐to‐face meetings and having signed letters of understanding with institutions at the start of the project. Despite the fact that membership fluctuated, these letters underscored the credibility of the project and facilitated trust‐building with new members.

3.3.3. Theme 3: Reported benefits

Members in both cases reported a variety of anticipated and actual benefits stemming from their participation in the project, reflecting a core component of partnership synergy. Participants described more professional than personal benefits. Benefits included, but were not limited to the following: learning about the work of other organizations and sectors; understanding how the services in one's organization complement services and approaches in others; learning about how a well‐organized meeting unfolds; devising more effective ways of addressing an issue that the organization had been grappling with; and ensuring system‐wide benefits if the project can demonstrate that the approach that is pursued works. In addition, respondents highlighted the benefits of the partnership approach to delivery of project goals, stating that “there is no other way to approach it” (013, PCCP). A number of indirect benefits were also reported, including enhanced visibility of one's own organization and opportunities for face‐to‐face exchange with other key stakeholders under the same organizational umbrella. Partnership members who were early career researchers were less positive about the benefits, citing high demands of participation for limited academic outputs. However, some of them remained committed to the partnership due to the strength of relationships with other stakeholders. While for most members participation in the project had been mandated by their respective organizations, the majority participated willingly, looked forward to meetings and saw a direct fit between the project's objectives and the priorities of the entities they represented. According to most interview respondents, the benefits of participation outweighed the drawbacks, effectively demonstrating positive partnership synergy.

The mutually beneficial nature of the partnerships was apparent as participants described mutual and personal learning and satisfaction with their involvement in the projects:

So to be able to be part of the project […] I think that they had a great idea, it's really smart, and I felt really glad to be part of that. You know because I feel like that's a good project […] very helpful, this is a very […] significant issue for people. And to be able to be part of maybe, you know, exploring why it's a problem and offering my insights, I'm very excited to be able to do that. (019, CHRP).

3.3.4. Theme 4: Capacity for adaptation to context

Partnership activities were unfolding within the context of health care system reforms in both provinces. Both partnerships had to make adaptations to the interventions to respond to evolving contextual opportunities and threats, but the extent of contextual impact and adaptation was far greater in the case of the PCCP, which demonstrated synergy in its ability to adapt to its changing context. During the implementation period, the province's health care system underwent a major reform,41, 42 leading to a number of policy changes. In the process, the partnership lost most of its nonacademic members, had to re‐develop relationships with new stakeholders, and had to modify the intervention several times to accommodate new system priorities. Academic partnership participants revealed that the impact of changes was so profound that they feared a complete dissolution of the partnership and termination of the project. These developments reflected weakened partnership synergy. However, the momentum generated through synergy in other areas, namely trust, partnership credibility, and organizational buy‐in, contributed to keeping the project alive:

[…] even though everyone around the table had changed, we have managed to keep representatives roughly the same from each of the organizations that were with us since the beginning. What made it easier was that we had the commitment of people pretty high up in those organizations […] In addition, we managed to establish a climate of trust. So even though the people around the table changed, they knew that the organizations had been there for a while and it was going well. (011, PCCP).

Given that contextual changes were frequent topics of conversation during face‐to‐face PCCP meetings, there were no reported differences in stakeholders' appreciation of the impact of context depending on their roles in the partnership.

The CHRP stakeholders described the context as “chaotic” (018, CHRP), with a well‐integrated hospital and specialist sector, poorly organized community health services, and fragmented primary care. At the time of project activities, the province underwent significant changes in its health care system, with services being integrated sub‐regionally based on geographical utilization patterns, within the framework of tight budgets, contract negotiations, and increasing demands on the system. It was felt that the project was timely in terms of addressing some of these challenges posed by changes in the context. The main concern voiced related to the possibility of the intervention duplicating existing services. The research team proactively addressed this concern by incorporating at the start of some partnership meetings a description of how the navigator model was different from and complementary to other services, and by allocating time for dialogue around it. At a closer, organizational, level the CHRP experienced a gap of 1.5 years between partner meetings due to delays in ethics protocols approvals. However, similar to the PCCP, the partnership synergy generated earlier, evidenced in the quality of stakeholder relationships and the importance attributed to the initiative, contributed to sustained stakeholder participation. Overall, the stakeholders' appreciation of the impact of external context on the project and partnership varied depending on their role in the partnership. Decision makers provided a more in‐depth assessment of the context and how it affected the intervention. Most stakeholders felt that contextual changes were inevitable, and the partnership just had to adapt to them: “[…] coping with the environment, the environment is what it is, it's a changing environment and you have to adapt” (018, CHRP).

Interviewees also noted the influence of the partnerships and the interventions on their organizations and the broader context. Decision makers in particular referred to acquiring and sharing within their respective organizations a deeper understanding of the plight of vulnerable populations in relation to access issues. Members of community‐based service organizations referred to generating insights into how to improve their organizations' services, whereas family physicians became more aware of existing services that patients could be referred to.

3.4. Synergy enabling processes

Both partnerships employed specific processes to facilitate the work of the partnerships. The following main categories of processes emerged from our data: (a) interpersonal processes, (b) operational processes, and (c) system‐level processes (Figure 1).

3.4.1. Interpersonal processes

At the interpersonal level, participants highlighted the importance of communication processes, relationship building and maintenance, and learning loops. Both partnerships had open and multidirectional channels of communication, mostly confined to regular partnership face‐to‐face meetings and electronic means, to communicate internally with stakeholders within the partnership. Learning loops involved soliciting feedback during meetings around issues related to the project and being transparent about how this input was subsequently incorporated. External communication aimed at increasing the support for interventions, recruiting medical practices, and disseminating information about partnership activities and achievements to wider audiences. While some stakeholders had a history of working together, relationships with other stakeholders had to be built and nurtured. Face‐to‐face meetings were identified as being key to developing relationships.

3.4.2. Operational processes

At the operational level, the processes involved resource management, leadership, administration and management, and decision‐making. Both partnerships utilized a variety of ways to engage respective stakeholders. The partnerships organized deliberative fora involving a broad range of stakeholders, to learn about unmet health care needs of vulnerable populations, relevant community organizations, and available resources to support interventions. The PCCP subsequently involved stakeholders in various aspects of the research process, with a number of nonacademic stakeholders fulfilling tasks outside the partnership meetings. Conversely, the CHRP adopted a research advisory approach to working with stakeholders, with limited contribution of nonacademic stakeholders outside face‐to‐face meetings. Both partnerships used regular meetings to discuss project progress and to engage in collaborative learning. Participants emphasized the added value of acquiring relevant knowledge, having space to exchange with other partners, reflect and innovate (which was not always possible within the stakeholders' respective organizational contexts), as well as educational and capacity‐building opportunities.

The partnerships were largely driven by the research teams responsible for the overall management of the projects, providing strategic direction and facilitating the development of interventions at the local level, through continuous dialogue and learning, as well as sharing of information. The research teams capitalized upon the various strengths and perspectives of stakeholders, by providing sufficient time to discuss pressing issues, soliciting input from all stakeholders, offering stakeholders different mechanisms to contribute, and tailoring tasks to stakeholders' availabilities and interest. The PCCP leveraged the power of leadership distributed among academic and nonacademic stakeholders, while in the CHRP, the leadership was centralized within the research team. However, the CHRP interview participants reported that the research team seemed genuinely interested in hearing from all stakeholders and made efforts to check in with various groups around the partnership table.

A number of leadership processes were common to both cases. Both partnerships had formal and informal academic leaders knowledgeable about the context and skilled at mobilizing the various perspectives of partners. The leaders did not possess all of the required partnership‐related knowledge and skills at the outset, but made intentional efforts to learn from experience and best practices in partnership literature and to acquire additional skills through training. Moreover, as the partnerships evolved and the level of trust within teams increased, the leaders were more transparent about their own gaps in knowledge surrounding the interventions and eagerly welcomed input from different stakeholders. This demonstration of vulnerability contributed to creating further trust.

The PCCP stakeholders reported that the decision‐making process was inclusive and transparent, which was particularly useful in relation to adapting the intervention to its evolving context. Conversely, consistent with the advisory nature of the partnership, the CHRP decision‐making power was centralized within the research team.

3.4.3. System‐level processes

At the system level, participants described processes geared toward making ongoing adaptations to the evolving context. In both cases, responsiveness to external stimuli involved adaptations to the interventions' structure, implementation strategy, and personnel resources. Participants reported that processes such as conducting extensive fieldwork to gather information, having around the table a variety of key stakeholders with medium to high level of decision‐making power in their respective organizations, open dialogue about the evolving context, and, in the case of the PCCP, transparent processes of decision‐making, contributed to the ability of the partnerships to adapt interventions to rapidly changing policy contexts. The situational analysis involved leveraging the knowledge of multiple partners. The active engagement in the partnerships of decision makers and health system planners was critical in this respect, as it contributed to an in‐depth understanding of health system priorities.

4. DISCUSSION

This study illustrated the multidimensional, dynamic nature of partnership synergy and its role not only as a proximal outcome of partnership functioning but also as a facilitator of multi‐stakeholder partnerships in two geographical settings, in the context of tackling challenges in the delivery of high‐quality PHC to vulnerable populations. The study also provided insights into the structures and processes to sustain these partnerships. These two key findings are discussed in more detail below. Although there is a substantial number of quantitative and review studies that have incorporated concepts from the partnership synergy framework,10, 22, 23, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47 to our knowledge, empirical studies applying these concepts to frame qualitative research findings are rare, with Brush et al24 and Corbin and Mittelmark48 being two examples of such studies, which also proposed synergy models. Employing the partnership synergy lens allowed us to systematically assess its manifestations and to acquire a deeper understanding of this phenomenon. Taking into consideration that the partnerships were in the implementation stage of their interventions, we could not comprehensively assess the intended partnership outcomes. Our data contained preliminary evidence of the positive impacts of the interventions in both cases. However, the sustainability of interventions and partnerships beyond the life of the IMPACT grant was, according to our interview respondents, questionable.

This study will be followed by a quantitative study involving all six IMPACT partnerships that will attempt to measure whether (and how) the partnerships have achieved partnership synergy and whether certain partnership processes contributed to more strategic advantages. The results pertaining to the outcomes of the developed IMPACT interventions will be reported elsewhere.49

4.1. Partnership synergy

Our first key finding relates to the multidimensional nature of partnership synergy. Our data indicate that partnership synergy manifests itself in different ways. We identified the following four areas where partnership synergy was apparent: (a) the integration of nonfinancial and financial resources, (b) partnership atmosphere, (c) reported benefits, and (d) capacity for adaptation to context. Our analysis revealed the complex interactions among the four areas. The composition that reflected the diversity and complexity of the presenting problem allowed for faster adaptations to contextual stimuli. The generated benefits were critical to the sustained level of stakeholder commitment. The quality of collaborative relationships and positive partnership atmosphere facilitated additional stakeholder recruitment and allowed to maintain momentum. These inter‐connections suggest that synergy components are neither static nor independent; similar to a hologram,50 they allow us to obtain a more intense picture of partnership synergy. Given the highly contingent nature of partnerships, there will arguably be other areas where synergy might manifest itself, depending on a partnership's objectives and internal and external influences. The original Lasker and Weiss's model (2001), viewing partnership synergy as an outcome, for example, placed more emphasis on outcome elements, such as the ability of developed strategies to address the needs of target populations.

Second, our findings highlight the dynamic nature of partnership synergy. As partnerships progressed, partnership synergy in both partnerships fluctuated. Both partnerships evolved from a group of individuals with common interests (low synergy) into entities with a requisite degree of openness, inter‐dependence, and enhanced understanding of presenting issues (higher synergy)—all of which contributed to deeper decision‐making and effective adaptations to intervention models. Conversely, partnership synergy could weaken, as was illustrated with an example of the profound impact on the PCCP of its volatile context. This finding is broadly consistent with prior research that suggested that synergy was a dynamic health indicator of a collaborative process24 and that it was more likely to accrue during the formation stage of the partnership but subsequently decrease during the implementation stage.51

The third characteristic of partnership synergy revealed in our analysis is the contribution of partnership synergy to sustaining partnerships. The composite strength of partnership synergy in the PCCP was sufficient to offset the impact of the destructive contextual circumstances and allowed the partnership to regenerate itself. Analogous to the body's immune system, partnership synergy appeared to provoke a protective response allowing the partnership to persevere in the face of adversity. In addition, partnership synergy contributed to partnership improvement. Given that working in partnership required skills that were different from those employed in the typical running of research studies, the partnerships made strategic financial investments into acquiring these new skills. Instead of outsourcing certain partnership‐related tasks, the partnerships built capacity in‐house through training partnership coordinators in group process facilitation techniques and then providing them with opportunities to facilitate partnership meetings. This investment was not only part of building capacity within the partnership; the coordinators used the training as a springboard for subsequent process improvements and self‐organization that benefitted the partnerships directly, strengthening them and contributing to synergy. The return on this investment was high and contributed to lower effort on the part of academic investigators to facilitate partnership activities.

4.2. Structures and processes

This study adds depth to understanding of partnership resource requirements and demonstrates the centrality of enabling processes at the interpersonal, organizational and system levels to achieve synergistic action among multiple stakeholders. Due to the organizational structure and type of the IMPACT program funding, the two partnerships under investigation were largely driven by the research teams that initiated the partnerships—a finding that is consistent with the literature on collaborative health research partnerships.17 These research teams and a number of key nonacademic stakeholders constituted a relatively consistent continuous core in each partnership, effectively acting as “champions” keeping the collaboration going.52 Other members were selected strategically, to attract specific expertise, perspectives, and additional resources. This was supplemented by more organic selection based on emerging needs as the projects unfolded. The dynamic composition allowed for fluidity, complementarity, and heterogeneity that reflected the critical dimensions of the problem to be addressed and of the changing context. Having stakeholders around the table with medium to high level of authority in their respective organizations allowed for timely adaptations to interventions.

The CHRP was larger than the PCCP, reflected more linguistic diversity, and had more permeable organizational boundaries due to receiving additional funding for the second phase of the research project. This independent funding added complexity by broadening the scope of the project and requiring the involvement of additional expertise. The partnership's size necessitated a higher degree of formalization, which was evidenced in the structured ways of organizing meetings and soliciting input from stakeholders. This finding is consistent with the argument from organizational theory that larger organizations tend to require more formalized behavior and more developed administrative components.53 Different stakeholders were brought in as the needs of the partnership evolved, with relatively consistent representation from the target population. The partnership adopted a research advisory approach, with the decision‐making power centralized with the research team, and a limited contribution of nonacademic stakeholders outside the face‐to‐face meetings. Overall, the project undertaken by the CHRP was deemed by interview respondents to be meaningful and timely.

The PCCP was smaller, with more defined boundaries, but had a higher degree of internal complexity due to working with two local health authorities, each with different organizational cultures and processes. The PCCP exhibited elements of horizontal decentralization53 and holographic organization,50 with the diffusion of leadership and decision‐making power among academic and nonacademic stakeholders. All stakeholders participated actively in the co‐construction of the various aspects of the project, and some nonacademic stakeholders fulfilled tasks outside the partnership meetings. The small size and decentralization of power allowed the PCCP to remain nimble and responsive to change. These findings are aligned with organizational theory that states that more complex and dynamic environments necessitate more organic and decentralized structures and decision‐making power.53

We identified a number of collaborative processes driving the synergy of the two partnerships, at interpersonal, operational, and system levels, each a critical piece of the synergy puzzle, but also a source of potential problems if misaligned with the needs or context. For example, the decentralized form of leadership that contributed to partnership synergy in one partnership may have been counterproductive in the other. In practice, however, the key contributor or threat to partnership synergy cannot be isolated due to the inherent complexity of partnerships within their local contexts. “Because an element in a group can affect other elements, any element or combination of elements could be contributing to the group's ineffectiveness.”54 Our study demonstrated how contextual adaptation in the case of the PCCP necessitated certain decision‐making processes, appropriate forms of communication, and specific actions from the team that fulfilled the “backbone”3 coordinating support to the partnership. This interaction of process variables is not confined to the partnership itself, for partnerships are subject to the influences of their constituent organizations and larger contexts. When partnerships experience decreased synergy, our evolving model of synergy (as depicted in Figure 1) can support the diagnostic task of identifying the sources of the problem and the task of devising solutions to address it, paying particular attention to the interplay of variables.

The optimal configurations of these processes and their interaction with partnership resources and context can be highly variable, depending on the specifics of each partnership.43 Indeed, as the IMPACT program progressed, each of the partnerships under our investigation evolved in different ways, based upon the specific context within which it was developing, the local access need that the partnership tried to address, tailored processes and requirements to meet this need, and the relationships that formed to move the work forward. In participatory research terms, the PCCP stakeholder participation exhibited elements of “co‐construction” or “co‐governance,” whereas in the CHRP it was more aligned with “consultation.”55 Each of these configurations fit the objectives and the needs of the respective partnerships. Our findings support prior research that highlights that partnership as a form of multi‐organizational working relationship is a variable concept and works differently under different circumstances.56, 57

It is important to note that an in‐depth exploration of the challenges of partnering was beyond the scope of this study. The main challenges reported by our study participants included the following: considerable time commitments, insufficient credit for investing energy into the partnership, challenges with bridging organizational divides, and difficulties optimizing the involvement of knowledge users (the people affected by the partnership's work). These obstacles affected some stakeholders' motivation, their level of participation, and, subsequently, partnership synergy. These findings indicate the importance of devoting attention to the balance of costs and benefits and recognizing and responding to perceived and actual disengagement throughout the life of the partnership.

4.3. Implications for practice and future research

The partnership synergy framework4 is useful in assessing the intermediate outcomes of ongoing partnerships when it is too early to evaluate the achievement of long‐term intended outcomes. It should be incorporated into routine partnership evaluation, starting with a baseline assessment. The list of variables offered by the framework allows partnership practitioners and evaluators to select those relevant to a particular partnership, identify the levers of change, and calibrate inputs accordingly in an attempt to increase partnership synergy. Future research should focus on identifying other manifestations of partnership synergy and documenting conditions under which these manifestations emerge. The ultimate objective would be to determine if partnership synergy could indeed become a source of “renewable energy” for a partnership. It would equally be important to document instances of negative partnership synergy or antagony48 and identify “tipping point” scenarios where the composite partnership synergy no longer offers its protective effect.

4.4. Limitations

This section outlines the limitations of this study and how these limitations were mitigated. First, the study of the partnership aspects was largely conducted by one member of the research team (the first author). Individual biases may have affected the coding and interpretation of data. However, the first author is experienced in qualitative data gathering, coding, and analysis. In addition to being exposed to the partnership phenomena over a prolonged period of time, the following strategies were employed to reduce the effect of investigator bias: (a) triangulation from multiple sources of evidence, and (b) keeping an “audit trail” to document decisions made throughout the research process.58 Moreover, the coding frames and analytic plan were developed and validated with other members of the research team. Second, participants may have provided a more favorable assessment of the partnerships, given the voluntary nature of engagement and the stage of the partnerships by which those who did not see value in participating would have resigned. We attempted to minimize this limitation through the use of purposive sampling, which enabled the selection for interviews of a mix of seasoned and new partnership participants and those demonstrating high and low levels of participation. In addition, the semi‐structured interview format allowed the interviewer to explore negative cases. Third, this study analyzed only two of the six IMPACT local partnerships and just some of the partnership manifestations. Some important aspects of partnership functioning may not have been captured. The two partnerships were chosen in light of feasibility considerations, and the partnership dimensions were selected in alignment with the chosen theoretical framework. This study will be followed by a quantitative study involving all six IMPACT partnerships. Finally, the study unfolded within the context of a funded program of research with a targeted scope to improve accessibility to PHC for vulnerable populations. Caution is warranted when transferring these results to different, less resourced contexts. Rich contextual descriptions were provided for each of the two IMPACT local partnerships allowing other scholars and practitioners to determine whether and how the results may be applicable in different contexts.

FUNDING

This research would not have been possible without the support of the IMPACT program's funders. IMPACT—Improving Models Promoting Access‐to‐Care Transformation program was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (TTF‐130729) Signature Initiative in Community‐Based Primary Healthcare, the Fonds de recherche du Québec ‐ Santé and the Australian Primary Health Care Research Institute, which was supported by a grant from the Australian Government Department of Health, under the Primary Health Care Research, Evaluation and Development Strategy. Ekaterina Loban would like to acknowledge funding of a doctoral stipend through the IMPACT research program (2015‐2018). The funding bodies played no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors of this paper have no conflict of interest to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Ekaterina Loban, Catherine Scott, Virginia Lewis, Susan Law, Jeannie Haggerty.

Data Curation: Ekaterina Loban.

Formal Analysis: Ekaterina Loban.

Funding Acquisition: Catherine Scott, Virginia Lewis, Jeannie Haggerty.

Investigation: Ekaterina Loban.

Methodology: Ekaterina Loban.

Project Administration: Ekaterina Loban.

Resources: Catherine Scott, Virginia Lewis, Jeannie Haggerty.

Supervision: Catherine Scott, Jeannie Haggerty.

Validation: Ekaterina Loban, Catherine Scott, Virginia Lewis, Susan Law, Jeannie Haggerty.

Writing–Original Draft Preparation: Ekaterina Loban.

Writing—Review and Editing: Ekaterina Loban, Catherine Scott, Virginia Lewis, Susan Law, Jeannie Haggerty.

All authors agreed on the order in which their names are listed in the article.

I, Ekaterina Loban (the corresponding author), confirm that I had full access to all of the data in the study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

TRANSPARENCY STATEMENT

We confirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research would not have been possible without the support of the IMPACT program research team and all stakeholders who were involved in this study. We also acknowledge the contribution of the following supporting partners: the Department of Family Medicine of McGill University, St. Mary's Research Centre, Université de Sherbrooke, Bruyère Research Institute, PolicyWise for Children & Families, Monash University, La Trobe University, the University of Adelaide, the Bureau of Health Information, and the University of New South Wales.

APPENDIX A. INTERVIEW PROTOCOL

Questions.

General:

As you are aware, each IMPACT site has established a local innovation partnership (LIP)—partenariat d'innovation local (PLI). These look slightly different in each of the six sites. The first couple of questions are just to get an initial picture or overview of “what” it is and how you are involved.

- How would you describe the way your LIP is organized (ie, membership, structure [committees, working groups], resources, frequency of meetings and communication, leadership [eg, distributed]).

- When you say “your LIP” or “the LIP” what are you referring to?

- How have you been involved with your LIP? Please describe.

- How long have you been involved with your LIP?

- Your role

Work sharing:

-

3How would you describe key tasks and activities of your LIP?

- How is the work divided among the different partners?

- How would you describe the roles of members? How do they contribute?

Decision‐making/problem‐solving:

-

4

Can you name 2 to 3 significant decisions that were made in the past year?

-

5

How are decisions made? How are decisions communicated? (prompts: committee process; voting/consensus; transparency).

-

6

How are challenges resolved/ conflict dealt with?

-

7

Can you name 2 to 3 significant problems encountered in the past year? How were they resolved? (if appropriate: What were the consequences of conflict or efforts to resolve problems [benefits, risks]?)

Complementarity of skills:

-

8Describe how the LIP is building on the strengths and resources of its members

- What facilitates member contributions?

- What limits member contributions (barriers)?

-

9

How is the partnership including the views and priorities of the people affected by the partnership's work?

-

10

Has there been any change over time in terms of how team members contribute?

Benefits/value added:

-

11What are the perceived benefits of participating in the activities of the LIP/IMPACT program in general?

- How do you benefit (professionally/personally)?

- How does your organization benefit (policy/practice/service delivery)?

-

12

How do you perceive that others are benefitting from their participation?

-

13

What sorts of benefits do you perceive that are above and beyond what might have been expected as a result of working in this partnership, as opposed to working independently? If yes, could you provide a few examples? If no, are there any limitations that you can think of?

Outcomes:

-

14

What is the LIP trying to achieve?

-

15

Does it seem as if everyone understands and supports these goals (ie, Is everyone headed in the same direction)?

-

16

How would you describe the LIP's progress toward these goals to date?

Experience:

-

17

How would you describe your overall experience of being part of this LIP?

-

18

What has been the most positive aspect of your involvement?

-

19

What has been the most negative aspect of your involvement?

-

20

Do you look forward to the meetings of the LIP? Why or why not?

Energy:

-

21

What words would you use to describe the general atmosphere of the LIP (eg, level of energy surrounding the LIP)

Synergy‐promoting strategies (enablers and barriers to partnership):

-

22

Describe the processes and approaches that have been used to facilitate the work of the LIP.

-

23

What's working well? How do you know (are there any indicators of success)?

-

24

From your perspective, what might be improved? And how? What would make your LIP more effective?

Closing:

-

25

Is there anything else that you would like to mention?

APPENDIX B. CROSS‐CASE SYNTHESIS HIGHLIGHTING FACTORS FOSTERING/HINDERING PARTNERSHIP SYNERGY, INCLUDING ILLUSTRATIVE QUOTATIONS

| Categories of factors likely to influence partnership synergy | Factors fostering or hindering partnership synergy | Primary Care Connection Partnership (PCCP) | Community Health Resources Partnership (CHRP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure |

|

||

| Partner Characteristics | Composition (Lasker et al. model: heterogeneity) |

|

|

| Nature and level of stakeholder engagement (Lasker et al. model: level of involvement) |

|

Well, the meetings it's more […] around discussions, about what they want to do with the project, rather than the actual operational pieces of that. Another part of the team, I believe, has been doing that piece. So it's primarily been more like advisory kind of input. (017, CHRP).

[…] I think, that it changed over time. So certainly at the outset I think it was more information gathering, you know, what's out there, what works, what have you guys tried, who's doing what, that sort of thing, that was at the start. Then I would say there was that phase we have got an idea now but we need some further resources because our grant is not going to cover all this stuff. (015, CHRP).

|

|

| Partnership Characteristics | Leadership |

|

|

|

|

||

| Administration and management |

|

|

|

| Decision‐making (Lasker et al. model: governance) |

The decisions … before being made, there is a study, consultation, a consultation process that is undertaken, and that's really commendable. This is done through email exchange. They ask three questions, four questions, following our last meeting, where we had not necessarily identified the solution to resolve our problem. They ask questions, we analyse the answers when we meet again. At that point you have to decide. They submit the hypotheses to us, a proposal, a decision, we discuss it and we decide. So that it is done in a group, it is during meetings that it is done. (013, PCCP). |

|

|

| Relationships among partners | General atmosphere |

|

|

| Trust |

|

[…] it's positive and everybody seems to think that they have a … they make a difference, yeah. And so they are in there and people are actually taking notes when they speak, the patients aren't used to having people take notes about what they say. Well, this happens at this meeting, and people actually pay attention. (018, CHRP). |

|

| Conflict |

“I did not sense any conflict, but if there were moments where there was misunderstanding regarding certain aspects, […] it was [managed] through conversation.” (020, PCCP).

|

|

|

| Resources | Financial resources |

|

|

|

|||

| Nonfinancial resources |

|

||

| External Context | Community characteristics/ history of prior collaboration |

[…] it was pretty special, because, all the people around the table did not know each other and had never worked together. Worse even we could see that they were not ready to work together, they had never spoken to each other. (011, PCCP). |

|

| Policy context |

“The change is quite major […]it's a transition, it's difficult, and we are right in the middle of it.” (013, PCCP).

|

|

|

Abbreviation: IMPACT ‐ Innovative Models Promoting Access‐to‐Care Transformation.

Loban E, Scott C, Lewis V, Law S, Haggerty J. Improving primary health care through partnerships: Key insights from a cross‐case analysis of multi‐stakeholder partnerships in two Canadian provinces. Health Sci Rep. 2021;4:e397. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.397

Funding information Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Grant/Award Number: TTF‐130729; Fonds de recherche du Québec ‐ Santé; Australian Primary Health Care Research Institute

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The raw data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions given the small sample and the qualitative nature of inquiry.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chircop A, Bassett R, Taylor E. Evidence on how to practice intersectoral collaboration for health equity: a scoping review. Crit Public Health. 2015;25(2):178‐191. 10.1080/09581596.2014.887831 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henderson S, Wagner JL, Gosdin MM, et al. Complexity in partnerships: a qualitative examination of collaborative depression care in primary care clinics and community‐based organisations in California, United States. Health Soc Care Community. 2020;28(4):1199‐1208. 10.1111/hsc.12953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kania J, Kramer M. Collective impact. Stanf Soc Innov Rev. 2011;9(1):36‐41. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lasker RD, Weiss ES, Miller R. Partnership synergy: a practical framework for studying and strengthening the collaborative advantage. Milbank Q. 2001;79(2):179‐205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drahota A, Meza RD, Brikho B, et al. Community‐academic partnerships: a systematic review of the state of the literature and recommendations for future research. Milbank Q. 2016;94(1):163‐214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verma J, Peterson S, Samis S, Akunov N, Graham J. Healthcare priorities in Canada: a backgrounder. Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement. 2014. https://slidelegend.com/queue/healthcare-priorities-in-canada-a-backgrounder-canadian-_5b10306f7f8b9ac1048b458e.html

- 7.El Ansari W, Phillips CJ, Hammick M. Collaboration and partnerships: developing the evidence base. Health Soc Care Community. 2001;9(4):215‐227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dowling B, Powell M, Glendinning C. Conceptualising successful partnerships. Health Soc Care Community. 2004;12(4):309‐317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horton D, Prain G, Thiele G. Perspectives on Partnership: A Literature Review. International Potato Center (CIP), Lima, Peru. Working Paper 2009‐3, 2009.

- 10.Cramm JM, Nieboer AP. Disease‐management partnership functioning, synergy and effectiveness in delivering chronic‐illness care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24(3):279‐285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kegler MC, Steckler A, McLeroy K, Malek SH. Factors that contribute to effective community health promotion coalitions: a study of 10 project ASSIST coalitions in North Carolina. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25(3):338‐353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larkan F, Uduma O, Lawal SA, van Bavel B. Developing a framework for successful research partnerships in global health. Glob Health. 2016;12(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McQuaid RW. Theory of organisational partnerships – partnership advantages, disadvantages and success factors. In: Osborne SP, ed. The New Public Governance: Emerging Perspectives on the Theory and Practice of Public Governance. London: Routledge; 2010:127‐148. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell SM, Shortell SM. The governance and management of effective community health partnerships: a typology for research, policy, and practice. Milbank Q. 2000;78(2):241‐289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramaswamy R, Kallam B, Kopic D, Pujic B, Owen MD. Global health partnerships: building multi‐national collaborations to achieve lasting improvements in maternal and neonatal health. Glob Health. 2016;12(1):22. 10.1186/s12992-016-0159-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McQuaid RW. The theory of partnership: why have partnerships? In: Osborne SP, ed. Public‐Private Partnerships: Theory and Practice in International Perspective. London, England: Taylor & Francis e‐Library; 2005:9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sibbald SL, Kang H, Graham ID. Collaborative health research partnerships: a survey of researcher and knowledge‐user attitudes and perceptions. Health Res Policy Syst. 2019;17(1):92. 10.1186/s12961-019-0485-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keleher H. Partnerships and Collaborative Advantage in Primary Care Reform. In: Deeble Institute. 2015. https://ahha.asn.au/publication/evidence-briefs/partnerships-and-collaborative-advantage-primary-care-reform

- 19.Butterfoss FD, Francisco VT. Evaluating community partnerships and coalitions with practitioners in mind. Health Promot Pract. 2004;5(2):108‐114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kreuter MW, Lezin NA, Young LA. Evaluating community‐based collaborative mechanisms: implications for practitioners. Health Promot Pract. 2000;1(1):49‐63. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bilodeau A, Laurin I, Clavier C, Rose F, Potvin L. Multi‐level issues in intersectoral governance of public action: insights from the field of early childhood in Montreal (Canada). J Innov Econom Manage. 2019;30:163. 10.3917/jie.pr1.0047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones J, Barry MM. Exploring the relationship between synergy and partnership functioning factors in health promotion partnerships. Health Promot Int. 2011a;26(4):408‐420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jagosh J, Macaulay AC, Pluye P, et al. Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: implications of a realist review for health research and practice. Milbank Q. 2012;90(2):311‐346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brush BL, Baiardi JM, Lapides S. Moving toward synergy: lessons learned in developing and sustaining community‐academic partnerships. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2011;5(1):27‐34. 10.1353/cpr.2011.0003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones J, Barry MM. Developing a scale to measure synergy in health promotion partnerships. Glob Health Promot. 2011b;18(2):36‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kringos D, Boerma W, Bourgueil Y, et al. The strength of primary care in Europe: an international comparative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(616):e742–e750. 10.3399/bjgp13X674422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457‐502. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Weel C, Kidd MR. Why strengthening primary health care is essential to achieving universal health coverage. CMAJ: Can Med Assoc J. 2018;190(15):E463–E466. 10.1503/cmaj.170784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.United Nations General Assembly . Enhanced cooperation between the United Nations and all relevant partners, in particular the private sector: Report of the Secretary‐General. 2003. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/501843?ln=en

- 30.Russell G, Kunin M, Harris M, et al. Improving access to primary healthcare for vulnerable populations in Australia and Canada: protocol for a mixed‐method evaluation of six complex interventions. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7):e027869. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dahrouge S, Gauthier A, Chiocchio F, et al. Access to resources in the community through navigation: protocol for a mixed‐methods feasibility study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2019;8(1):e11022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scott C, Miller W, Lewis V, Descôteaux S. IMPACT intervention implementation guide: A workbook for developing primary health care interventions for vulnerable populations. 2020. https://impactinterventionimplementation.pressbooks.com/

- 33.Siggelkow N. Persuasion with case studies. Acad Manag J. 2007;50(1):20‐24. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods. 5th ed.Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. 4th ed.London: Sage; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dicicco‐Bloom B, Crabtree BF. The qualitative research interview. Med Educ. 2006;40(4):314‐321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32‐item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349‐357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patton MQ. Qualitative research. In: Everitt BS, Howell DC, eds. Encyclopedia of Statistics in Behavioral Science. Vol 3. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2005:1633‐1636. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi‐disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):1‐8. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pluye P, Hong QN. Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35(1):29‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee G, Quesnel‐Vallée A. Improving access to family medicine in Québec through quotas and numerical targets. Health Reform Observer. 2019;7(4):2. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quesnel‐Vallée A, Carter R. Improving accessibility to services and increasing efficiency through merger and centralization in Québec. Health Reform Observer. 2018;6(1):2. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Corbin JH, Jones J, Barry MM. What makes intersectoral partnerships for health promotion work? A review of the international literature. Health Promot Int. 2018;33(1):4‐26. 10.1093/heapro/daw061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cramm JM, Phaff S, Nieboer AP. The role of partnership functioning and synergy in achieving sustainability of innovative programmes in community care. Health Soc Care Community. 2013;21(2):209‐215. 10.1111/hsc.12008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hermens N, Verkooijen KT, Koelen MA. Associations between partnership characteristics and perceived success in Dutch sport‐for‐health partnerships. Sport Manage Rev. 2019;22(1):142‐152. [Google Scholar]