Abstract

Background: Primary ovarian large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (POLNEC) is an extremely rare and highly aggressive malignancy. Establishing a definite diagnosis requires histopathologic examination with immunohistochemical demonstration of neuroendocrine differentiation in the tumor cells. The histopathology may overlap with a variety of other ovarian malignancies; however, rendering an accurate diagnosis is essential, owing to the therapeutic and prognostic implications. Case: A 62-year-old, post-menopausal woman presented with complaints of abdominal fullness and dull-aching abdominal pain for the last three months. A pelvic ultrasound revealed the presence of a complex adnexal mass. Serum levels of tumor markers, CA125, carcinoembryonic antigen, alpha-fetoprotein, and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin, were within normal limits. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging showed a heterogeneous lobulated right adnexal mass measuring 6.7×5.8×5.6 cm, which was T2-hyperintense and T1-hypointense. A provisional diagnosis of ovarian carcinoma was made, and a total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was performed. Results: Histopathology showed an organoid and nesting pattern with a focal perivascular arrangement of the tumor cells with large, moderately pleomorphic, round to oval nuclei, granular chromatin, conspicuous nucleoli, and a moderate amount of pale-eosinophilic cytoplasm. Brisk mitosis and lymphovascular space involvement were noted. On immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells showed positivity for chromogranin, synaptophysin, and neuron-specific enolase and were negative for PAX8, WT1, vimentin, and epithelial membrane antigen. p53 showed wild-type, and SMARCB1/INI-1 showed retained nuclear expression. Based on the histopathologic and immunohistochemical features, a final diagnosis of POLNEC was rendered. The patient received 4 cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy and is disease-free, 28 months post-treatment. Conclusions: The present report highlights the characteristic histopathologic and immunohistochemical features of POLCNEC to distinguish it from other clinicopathologic mimics and present a comprehensive review of the published literature of all such cases.

Keywords: Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, primary ovarian large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, non-small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, histopathology, immunohistochemistry

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) involving the female genital tract (FGT) are rare and account for around 2% of all the FGT tumors, with the cervix being the most common site. Ovarian NETs are very rare and include well-differentiated NETs or carcinoids (typical and atypical), as well as high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma, including small cell carcinoma of the ovary (SCCO) and non-small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (NSCNEC) [1]. Small cell carcinoma of the ovary is a highly aggressive malignancy, which has been further categorized into two distinct clinicopathologic subtypes, namely the pulmonary type (SCCOPT) and the hypercalcemic type (SCCOHT). Of these, SCCOPT represents a true neuroendocrine carcinoma, as evidenced by its immunohistochemical profile. At the same time, the hypercalcemic type exhibits a striking etiopathogenesis as well as morphologic resemblance to malignant rhabdoid tumors seen elsewhere in the body and hence is also better known as malignant rhabdoid tumor of the ovary [2-4]. Non-small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ovary is also known as large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC). LCNEC is extremely rare, being the rarest of all ovarian NETs [5]. The majority of the ovarian LCNEC have been reported in association with other ovarian neoplasms, including mucinous and endometrioid neoplasms and mature cystic teratoma. There are only 18 reports of primary pure LCNEC of the ovary [6,7].

Clinical diagnosis of ovarian NSCNEC/LCNEC is challenging as the majority of the patients present with non-specific symptoms, most common being abdominal mass, abdominal pain, or distension. Rarely, clinical manifestations associated with ectopic hormone production may also be noted. Radiologic features are not diagnostic, and these are mostly seen as large, unilateral cystic or heteroechoeic solid-cystic abdominopelvic masses [7]. Establishing a correct diagnosis is essential since these have a significantly poor prognosis compared to other ovarian malignancies. The microscopic features often overlap with other high-grade and undifferentiated ovarian malignancies. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is essential to establish a definitive diagnosis. Owing to the extreme rarity of this malignancy, many surgical pathologists are not aware of the distinctive histopathologic and immunohistochemical features, often leading to misdiagnoses, and poor management of these patients.

Case presentation

Clinical details

A 62-year-old, post-menopausal woman presented with complaints of abdominal fullness, and dull-aching abdominal pain for the last 3 months. There was no history of vaginal bleeding, loss of appetite or loss of weight. A pelvic ultrasound revealed the presence of a complex adnexal mass. Serum levels of tumor markers, CA125, carcinoembryonic antigen, alpha-fetoprotein, and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin, were within normal limits. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging showed a heterogeneous lobulated right adnexal mass measuring 6.7×5.8×5.6 cm, which was T2-hyperintense and T1-hypointense. A provisional diagnosis of ovarian carcinoma was made, and a total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was performed. Intraoperatively, a lobulated right ovarian mass was identified. Simultaneously, surgical exploration of other viscera and peritoneum was done; however, no abnormality was detected. The tumor was clinically staged as International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage Ia.

Gross examination

A surgical specimen of right ovarian mass, uterus, cervix, left ovary with attached fallopian tube, and omentum was received. The right ovarian mass measured 6×6×3 cm. The outer surface was irregular with hemorrhagic areas. The cut-surface was solid, grey-white with areas of hemorrhage. No papillary excrescences were identified.

Histopathologic characteristics

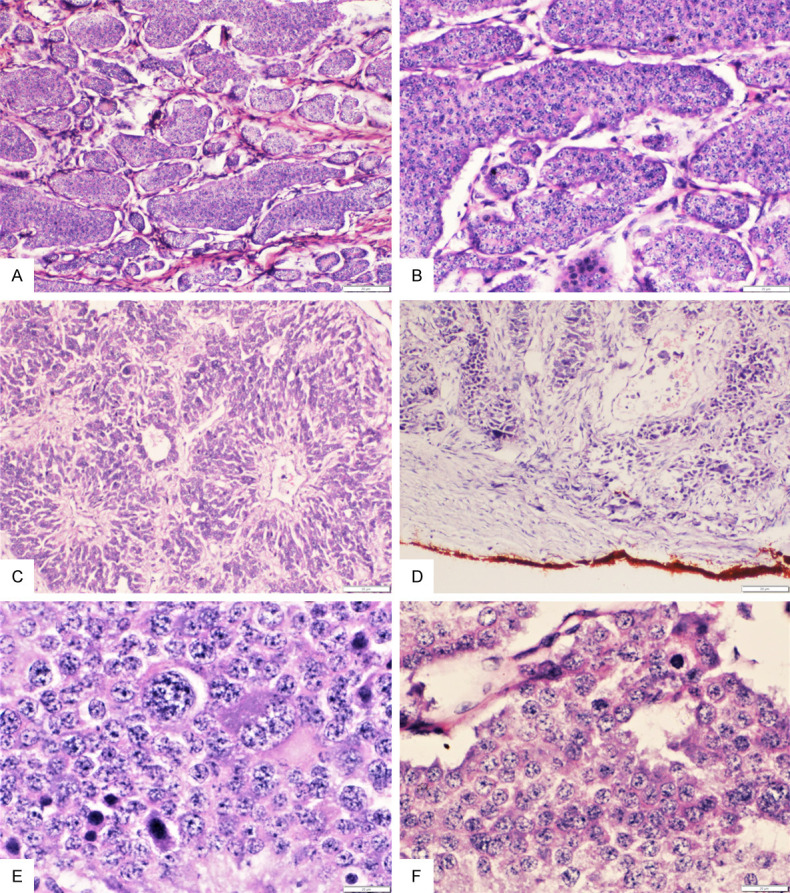

Microscopically, the right ovarian tumor showed a predominant organoid and nesting pattern with a focal perivascular arrangement of the tumor cells. The tumor cells were large, with moderate pleomorphism, round to oval nuclei with granular chromatin, conspicuous nucleoli, and a moderate amount of pale to eosinophilic cytoplasm. Brisk mitosis was noted, with the mitotic count being 6-7/10 high power fields (HPFs). There was no evidence of necrosis. Lymphovascular space involvement was noted [Figure 1]. Based on these histopathologic features, the differential diagnoses included small cell carcinoma of ovary, hypercalcemic type (SCCOHT), high-grade serous carcinoma, and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Sections from the uterus, cervix, bilateral fallopian tubes, left ovary, and omentum were free of tumor.

Figure 1.

A: Section from primary ovarian large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma showing a predominant organoid/nesting architecture (H&E; 10×); B: Higher magnification showing the nesting pattern of arrangement of the large moderately pleomorphic tumor cells (H&E; 20×); C: Section showing focal perivascular tumor cell arrangement (H&E; 10×); D: Section showing lymphovascular involvement by the tumor (H&E; 4×); E, F: Higher magnifications showing the markedly pleomorphic large tumor cells with large round nuclei, prominent nucleoli and scant to moderate amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm and scattered mitotic figures (H&E; 40×).

Immunohistochemical characteristics

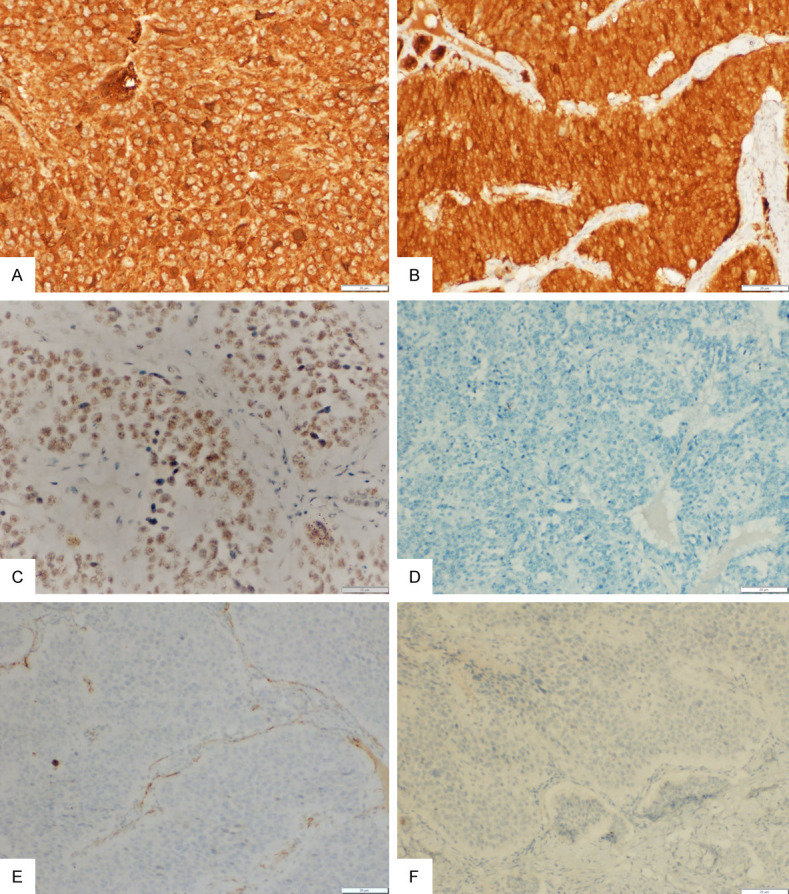

On immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells showed diffuse strong cytoplasmic positivity for the neuroendocrine markers chromogranin, synaptophysin, and neuron-specific enolase (NSE) [Figure 2]. They were negative for PAX8, WT1, vimentin, and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA). p53 was wild-type and SMARCB1/INI-1 showed retained nuclear expression in the tumor cells. Based on the histopathologic and immunohistochemical features, a final diagnosis of large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ovary was rendered.

Figure 2.

(A-F) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for chromogranin showing strong, diffuse, granular cytoplasmic positivity in the tumor cells (A; 20×), neuron specific enolase showing strong, diffuse cytoplasmic positivity (B; 20×), SMARCB1/INI1 showing retained nuclear positivity (C; 20×), while epithelial membrane antigen (D; 10×), WT1 (E; 20×), and inhibin (F; 10×) are negative in the tumor cells.

Patient management

The patient received four cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel and carboplatin. A follow-up positron emission tomography scan revealed no residual disease. The patient is disease-free currently, 28 months post-treatment.

Discussion

According to the latest World Health Organization (WHO) classification, primary ovarian large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (POLCNEC) is synonymous with the undifferentiated variant of the non-small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ovary [7,8]. Primary ovarian LCNEC is an infrequently reported, highly aggressive malignancy with poor prognosis and downhill clinical course. There are fewer than 60 such cases reported to date. More than half of these tumors are seen in association with other ovarian surface epithelial tumors, including mucinous neoplasms (benign, borderline, and malignant), endometrioid adenocarcinoma, and germ cell tumors, with the proportion of neuroendocrine carcinoma components ranging from 10-90% [7,9]. There are 18 cases of primary pure LCNEC of the ovary reported in the literature to date [7,10].

The exact etiopathogenesis of primary ovarian LCNEC is not well elucidated, and cell of origin is not determined as yet. It has been proposed that primary ovarian LCNECs may develop either due to clonal neoplastic transformation of the normal resident neuroendocrine cells in the ovarian surface epithelium or by a neoplastic neuroendocrine transformation of the non-neuroendocrine ovarian cells [11]. Both these theories are supported by the frequent association of LCNECs with ovarian surface epithelial neoplasms. However, others have proposed that these arise from teratomatous cells and the neoplastic transformation of primitive multipotent stem cells [12].

Primary ovarian LCNEC can affect women over a wide age range (18-80 years), with around 40% of patients in the reproductive age group. No case, to date, has been reported in children and adolescents less than 18 years of age. The most common clinical presentation is abdominal mass and/or pain, similar to other ovarian tumors [9,13]. CA125 levels can be variable, ranging from normal to elevated [14]. The index patient had normal CA-125 levels. Markedly elevated serum 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid (5-HIAA) has been reported in a few cases [15]. However, no specific tumor markers are available.

The histopathological features of POLCNECs are characteristic, and the index case corroborates previous reports. Positivity for neuroendocrine markers including synaptophysin, chromogranin, CD56, and NSE establishes the diagnosis, as in the index case [6,8].

The pathologic differential diagnoses include high-grade serous carcinoma, small cell carcinoma of the ovary, undifferentiated carcinoma, sex-cord stromal tumors with neuroendocrine differentiation, metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma, and metastatic melanoma. Focal neuroendocrine differentiation can be seen in a variety of other ovarian malignancies. Appropriate immunohistochemical markers, such as PAX8 and WT1 for serous carcinoma, inhibin for sex-cord stromal tumors, and HMB-45 for melanoma, may help exclude these differential considerations. Before making a diagnosis of POLCNEC, metastases to the ovary from a primary in the lungs or gastrointestinal tract must be ruled out by appropriate imaging studies [16]. Occasionally, non-ovarian primary malignancies otherwise showing no/limited neuroendocrine differentiation in the primary focus can metastasize to the ovaries and demonstrate extensive neuroendocrine differentiation. In such cases with two co-existent tumors, confirmation of the primary or secondary nature of the ovarian tumor can be done by performing molecular analysis of both tumors [16]. The key differentiating features of these histopathologic mimics are presented in Table 1 [2,3,7,16-18].

Table 1.

Characteristic morphologic and immunohistochemical features of histopathologic mimics of primary ovarian large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma [2,3,7,16-18]

| Tumor | Gross features | Microscopic features | Immunohistochemistry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma | Predominantly solid, lobulated, grey-white mass with areas of necrosis | Prominent nesting/organoid or trabecular pattern of arrangement. Tumor cells are large, round to polygonal with large nuclei, prominent nucleoli and scant to moderate amount of pale to eosinophilic cytoplasm. | Positive for chromogranin, synaptophysin, CD56, neuron specific enolase, dot-like positivity for cytokeratin, high Ki-67 index. |

| Negative for inhibin, EMA, WT1, CDX2, S-100, HMB-45, Melan-A, retained nuclear expression for SMARCA4/BRG1 and SMARCB1/INI1. | |||

| High-grade serous carcinoma | Large, complex, solid-cystic mass with numerous soft, friable papillary excrescences, with areas of necrosis and calcification | Complex, hierarchical branching papillae, glands, trabeculae and/or sheets of tumor cells, moderate to marked nuclear pleomorphism, with round to irregular nuclei, coarse chromatin, prominent nucleoli and moderate amount of cytoplasm. | Positive for CK7, PAX8, WT1, p16 and show mutant type positivity for p53, 7-20% may show neuroendocrine marker positivity, high Ki-67 index. |

| Negative for inhibin, CD10, HMB-45, Melan-A, CD10, retained nuclear expression for SMARCA4/BRG1 and SMARCB1/INI1. | |||

| Small cell carcinoma of the ovary, pulmonary type | Large solid-cystic mass with areas of necrosis, no papillary excrescences | Infiltrative tumor with diffuse sheet like arrangement of small hyperchromatic tumor cells with inconspicuous nucleoli and scant cytoplasm. Brisk mitotic activity along with multifocal necrosis is common. | Positive for chromogranin, synaptophysin and CD56 with variable positivity for EMA and TTF1. |

| Negative for vimentin, inhibin, CD10 and retained nuclear expression of SMARCA4/BRG1 and SMARCB1/INI1. | |||

| Small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type | Large solid-cystic mass with areas of necrosis, no papillary excrescences | Infiltrative tumor with diffuse sheet like arrangement of small hyperchromatic tumor cells; focal macrofollicle-like arrangement can also be noted. Scattered tumor cells with rhabdoid morphology with eccentric nuclei and prominent nucleoli also seen. Brisk mitosis and multifocal necrosis is common. | Hallmark is the loss of nuclear expression of SMARCA4/BRG1 and/or SMARCB1/INI1. |

| Generally positive for vimentin, variable expression of EMA, pancytokeratin, WT1, CD99, CD56. | |||

| Negative for chromogranin, synaptophysin, CD10, inhibin. | |||

| Undifferentiated carcinoma | Solid/solid-cystic, large tan-brown mass with necrosis and hemorrhage, mostly showing capsular breach | Infiltrative tumor with pattern less, sheet-like arrangement of tumor cells, no evidence of any particular differentiation, frequent mitosis, apoptosis and vascular invasion. | Tumor cells show focal, strong positivity for AE1/AE3, EMA, CK18, ER and PR, variable staining for vimentin, S-100, CD56, chromogranin, synaptophysin. |

| Negative for inhibin, HMB-45, Melan-A, retained nuclear expression of SMARCA4/BRG1 and SMARCB1/INI1. | |||

| Sex-cord stromal tumors with neuroendocrine differentiation | Predominantly solid, lobulated, pale-yellowish mass | Varied architectural patterns, including hollow/solid tubules, nodules, trabeculae, retiform and diffuse sheet-like arrangement. Tubules may be filled with hyaline material. Variable amount of cytoplasm. Admixed Leydig cells serve as an important diagnostic clue. | Tumor cells are positive for inhibin, calretinin, WT1, CD99, vimentin, ER, PR, with focal expression of chromogranin, synaptophysin and CD56 in areas with neuroendocrine differentiation, variable expression of pan cytokeratin, CK7 and CK8/18. Leydig cells positive for Melan-A. |

| Negative for EMA, HMB45, S-100. | |||

| Metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma | Bilateral small, lobulated/irregular solid/solid-cystic ovarian masses with prominent surface involvement with/without areas of necrosis | Insular/trabecular/cord-like architecture. Round to polygonal, moderately pleomorphic tumour cells with round to oval hyperchromatic nuclei, granular chromatin and moderate amount of granular eosinophilic cytoplasm. Necrosis may be noted. | Tumor cells are positive for chromogranin, synaptophysin, CD56, focally for pan-cytokeratin and TTF1. High Ki-67 index. |

| Negative for S-100, WT1, PAX8, EMA, HMB-45, Melan-A. | |||

| Metastatic melanoma | Unilateral/bilateral predominantly cystic/solid-cystic ovarian masses with large areas of necrosis and rarely blackish discoloration may be noted | Nodular or diffuse or nested architecture with focal follicle-like arrangement. Tumor cells can exhibit epithelioid or spindled morphology with moderate to marked pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, nuclear inclusions and cytoplasmic melanin. Multifocal necrosis is common. | Tumor cells are positive for S100, HMB-45, MART-1 and MiTF. |

| Negative for EMA, WT1, PAX8, chromogranin and synaptophysin. |

A comprehensive review of the published literature revealed a total of only 18 POLCNEC patients, and their clinicopathologic details are compiled in Table 2 [13,14,19-30]. The majority are older women, with 14 of them presenting in advanced disease stage (FIGO stage III/IV) [7]. Although standardized treatment protocols are not available to manage these rare tumors, multimodality treatment regimens involving surgery and adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy regimens are commonly used. More than 50% of these patients present at advanced stages (FIGO stage III or IV) and have poor disease outcomes despite therapy. The reported median overall survival time for these tumors is low, being ten months, even for patients presenting in an early stage of the disease [7]. From Table 2, it is evident that 7 out of 18 cases (39%) died of disease, whereas the rest were disease-free, indicating the appreciable success rate of multimodality management.

Table 2.

Review of literature showing all cases of pure primary ovarian large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma [13,14,19-29]

| S. no. | Authors | Age of patient (years) | Laterality | Size of the tumor (maximum dimension in cm) | FIGO Stage | Treatment received | Follow-up status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Behnam et al. (2004) [19] | 27 | Left ovary | 11 cm | Ia | Surgery: Left salpingo-oophorectomy with right ovarian biopsy with omentectomy, peritoneal biopsy, appendectomy and para-aortic lymphadenectomy | No evidence of disease at 10 months |

| Chemotherapy: paclitaxel + carboplatin | |||||||

| 2. | Agarwal et al. (2016) [20] | 35 | Left ovary | 6 cm | IIIc | Surgery: Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | Alive with disease at 3 months |

| Chemotherapy: None | |||||||

| 3. | Feki et al. (2020) [21] | 38 | Both ovaries | 20 cm pelvic mass (individual sizes not mentioned) | IV | Surgery: Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, appendectomy, splenectomy and pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy | Alive with disease at 50 months |

| Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy: Etoposide + cisplatin; following surgery: paclitaxel + carboplatin followed by cyclophosphamide + doxorubicin + vincristine followed by irinotecan + carboplatin | |||||||

| 4. | Shakuntala et al. (2012) [22] | 40 | Both ovaries | Left: 15 cm | IIIc | Surgery: Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with omentectomy, para-aortic lymphadenectomy, excision of urinary bladder and sigmoid colon deposits | No evidence of disease at 6 months |

| Right: 7 cm | Chemotherapy: etoposide + cisplatin | ||||||

| 5. | Yasuda et al. (2006) [23] | 44 | Right ovary | 9 cm | IIIc | Surgery: Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy | Died of disease at 22 months |

| Chemotherapy: Details not mentioned | |||||||

| 6. | Tsuji et al. (2008) [24] | 46 | Right ovary | 12 cm | III | Surgery: Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy | Died of disease at 4 months |

| Chemotherapy: None | |||||||

| 7. | Lin et al. (2014) [25] | 50 | Left ovary | 25 cm | IV | Surgery: Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy and appendectomy | Died of disease at 3 months |

| Chemotherapy: paclitaxel + carboplatin | |||||||

| 8. | Peng et al. (2020) [26] | 55 | Right ovary | 8 cm | III | Surgery: Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, pelvic lymphadenectomy and appendectomy | No evidence of recurrence at 3 months |

| Chemotherapy: paclitaxel + carboplatin | |||||||

| 8. | Ki et al. (2014) [14] | 58 | Left ovary | Not mentioned | Ia | Surgery: Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy followed by secondary debulking and para-aortic lymphadenectomy | Died of disease at 17 months |

| Chemotherapy: paclitaxel + cisplatin | |||||||

| 9. | Present case, 2020 | 62 | Right ovary | 6 cm | Ia | Surgery: Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | No evidence of disease at 28 months |

| Chemotherapy: paclitaxel + carboplatin | |||||||

| 10. | Oshita et al. (2011) [13] | 64 | Right ovary | 11 cm | IV | Surgery: Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy and peritoneal biopsy | No evidence of disease at 64 months |

| Chemotherapy: paclitaxel + carboplatin | |||||||

| 11. | Lindboe CF. (2007) [27] | 64 | Right ovary | 14 cm | Ia | Surgery: Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy | No evidence of disease at 9 months |

| Chemotherapy: bleomycin + etoposide + cisplatin | |||||||

| 12. | Ki et al. (2014) [14] | 67 | Left ovary | 13 cm | III | Surgery: Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with omentectomy, peritoneal biopsy and pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy | No evidence of disease at 5 months |

| Chemotherapy: paclitaxel + carboplatin | |||||||

| 13. | Feki et al. (2020) [21] | 67 | Both ovaries | 8 cm (individual sizes not mentioned) | IIIb | Surgery: Non-resectable (diagnosed on bilateral ovarian biopsy) | Died of disease post-chemotherapy (6 cycles) |

| Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy: paclitaxel + carboplatin | |||||||

| 14. | Yang et al. (2019) [7] | 70 | Right ovary | 20 cm | IIIc | Surgery: Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy | No evidence of disease at 3 months |

| Chemotherapy: etoposide + cisplatin | |||||||

| 15. | Dundr et al. (2008) [28] | 73 | Left ovary | 9 cm | IV | Surgery: Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, nephrectomy and resection of brain metastasis | No evidence of disease at 12 months |

| Chemotherapy: paclitaxel + carboplatin | |||||||

| 16. | Herold et al. (2018) [29] | 75 | Right ovary | 13 cm | IV | Surgery: Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpino-oophorectomy, omentectomy, peritoneal biopsy, and pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy | No evidence of disease at 36 months |

| Chemotherapy: etoposide + carboplatin; followed by paclitaxel + carboplatin | |||||||

| 17. | Aslam et al. (2009) [30] | 76 | Left ovary | 35 cm | IIb | Surgery: Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy | Died of disease post-surgery |

| Chemotherapy: None | |||||||

| 18. | Ki et al. (2014) [14] | 77 | Probably left ovary (not mentioned clearly) | 15 cm | IV | Surgery: Palliative | Died of disease at 1.5 months |

| Chemotherapy: Etoposide and carboplatin |

Conclusions

Primary pure large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ovary is an extremely infrequent and highly aggressive malignancy with a poor prognosis. Definitive diagnosis is achieved by demonstration of neuroendocrine differentiation on immunohistochemistry in the presence of characteristic histomorphology. Accurate diagnosis is essential for appropriate management and better outcomes in these patients.

Acknowledgements

An informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Vora M, Lacour RA, Black DR, Turbat-Herrera EA, Gu X. Neuroendocrine tumors in the ovary: histogenesis, pathologic differentiation, and clinical presentation. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293:659–665. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3865-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eichhorn JH, Young RH, Scully RE. Primary ovarian small-cell carcinoma of pulmonary type - a clinicopathological, immunohistologic, and flow cytometric analysis of 11 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:926–938. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199210000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young RH, Oliva E, Scully RE. Small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type. A clinicopathological analysis of 150 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:1102–1116. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199411000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta P, Kapatia G, Gupta N, Dey P, Rohilla M, Gupta A, Rai B, Suri V, Rajwanshi A, Srinivasan R. Small cell carcinoma of the ovary: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 7 new cases of a rare malignancy. Int J Surg Pathol. 2021;29:236–245. doi: 10.1177/1066896920947788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gardner GJ, Reidy-Lagunes D, Gehrig PA. Neuroendocrine tumors of the gynecologic tract: a society of gynecologic oncology (SGO) clinical document. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122:190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eichhorn JH, Lawrence WD, Young RH, Scully RE. Ovarian neuroendocrine carcinomas of non-small-cell type associated with surface epithelial adenocarcinomas. A study of five cases and review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1996;15:303–314. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199610000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang X, Chen J, Dong R. Pathological features, clinical presentations and prognostic factors of ovarian large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma: a case report and review of published literature. J Ovarian Res. 2019;12:69. doi: 10.1186/s13048-019-0543-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walker RA. World Health Organization classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of Tumours of the breast and female genital organs. Histopathology. 2005;46:229. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veras E, Deavers MT, Silva EG, Malpica A. Ovarian non small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 11 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:774–782. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213422.53750.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marco V, Guido R, Mauro P. The grey zone between pure (neuro) endocrine and non-(neuro) endocrine tumours: a comment on concepts and classification of mixed exocrine-endocrine neoplasms. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:499–506. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0306-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins RJ, Cheung A, Ngan HY, Wong LC, Chan SY, Ma HK. Primary mixed neuroendocrine and mucinous carcinoma of the ovary. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 1991;248:139–143. doi: 10.1007/BF02390091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yasuoka H. Monoclonality of composite large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and mucinous epithelial tumor of the ovary: a case study. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2009;1:55–58. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e31817fb419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oshita T, Yamazaki T, Akimoto Y, Tanimoto H, Nagai N, Mitao M, Sakatani A, Kaneko M. Clinical features of ovarian large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma: four case reports and review of the literature. Exp Ther Med. 2011;2:1083–1090. doi: 10.3892/etm.2011.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ki EY, Park JS, Lee KH, Bae SN, Hur SY. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ovary: a case report and a brief review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:314. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ngan HY, Collins RJ, Wong LC, Chan SY, Ma HK. The value of tumor markers in a mixed tumor, mucinous and neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 1989;35:272–274. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(89)90059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karpathiou G, Matias-Guiu X, Mobarki M, Vermesch C, Stachowicz ML, Chauleur C, Peoc’h M. Ovarian neuroendocrine carcinoma of metastatic origin: clues for diagnosis. Hum Pathol. 2019;85:309–312. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2018.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta D, Deavers MT, Silva EG, Malpica A. Malignant melanoma involving the ovary: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 23 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:771–780. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000126786.69232.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaspar HG, Crum CP. The utility of immunohistochemistry in the differential diagnosis of gynecologic disorders. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139:39–54. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2014-0057-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Behnam K, Kabus D, Behnam M. Primary ovarian undifferentiated non-small cell carcinoma, neuroendocrine type. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;92:372–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agarwal L, Gupta B, Jain A. Pure large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ovary with metastasis to cervix: a rare case report and review of literature. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:ED01–ED03. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/21639.8554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feki J, Sghaier S, Ennouri S, Mellouli M, Boudawara T, Mzali R, Khanfir A. Clinical and histological features of primary pure large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ovary. Libyan J Med Sci. 2020;4:90–93. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shakuntala PN, Uma Devi K, Shobha K, Bafna UD, Geetashree M. Pure large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of ovary: a rare clinical entity and review of literature. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2012;2012:120727. doi: 10.1155/2012/120727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yasuda M, Kajiwara H, Osamura YR, Hirasawa T, Muramatsu T, Murakami M, Takagi M, Tadokoro M, Kobayashi Y, Inayama Y, Miyagi E, Nakatani Y. Ovarian carcinomas with neuroendocrine differentiation: review of five cases referring to immunohistochemical characterization. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2006;32:387–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2006.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsuji T, Togami S, Shintomo N, Fukamachi N, Douchi T, Taguchi S. Ovarian large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008;34:726–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2008.00916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin CH, Lin YC, Yu MH, Su HY. Primary pure large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ovary. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;53:413–416. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peng X, Wang H. Primary pure large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ovary: a rare case report and review of literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e22474. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000022474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindboe CF. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ovary - case report and review of the literature. APMIS. 2007;115:169–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.apm_570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dundr P, Fischerová D, Povýsil C, Cibula D. Primary pure large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ovary. Pathol Res Pract. 2008;204:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herold N, Wappenschmidt B, Markiefka B, Keupp K, Kröber S, Hahnen E, Schmutzler R, Rhiem K. Non-small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ovary in a BRCA2-germline mutation carrier: a case report and brief review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:4093–4096. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.7836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aslam MF, Choi C, Khulpateea N. Neuroendocrine tumour of the ovary. J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;29:449–451. doi: 10.1080/01443610902946903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]