Abstract

Although considered a sporadic type of skin cancer, malignant melanoma has regularly increased internationally and is a major cause of cancer-associated death worldwide. The treatment options for malignant melanoma are very limited. Accumulating data suggest that the natural compound, capsaicin, exhibits preferential anticancer properties to act as a nutraceutical agent. Here, we explored the underlying molecular events involved in the inhibitory effect of capsaicin on melanoma growth. The cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA), isothermal dose-response fingerprint curves (ITDRFCETSA), and CETSA-pulse proteolysis were utilized to confirm the direct binding of capsaicin with the tumor-associated NADH oxidase, tNOX (ENOX2) in melanoma cells. We also assessed the cellular impact of capsaicin-targeting of tNOX on A375 cells by flow cytometry and protein analysis. The essential role of tNOX in tumor- and melanoma-growth limiting abilities of capsaicin was evaluated in C57BL/6 mice. Our data show that capsaicin directly engaged with cellular tNOX to inhibit its enzymatic activity and enhance protein degradation capacity. The inhibition of tNOX by capsaicin was accompanied by the attenuation of SIRT1, a NAD+-dependent deacetylase. The suppression of tNOX and SIRT1 then enhanced ULK1 acetylation and induced ROS-dependent autophagy in melanoma cells. Capsaicin treatment of mice implanted with melanoma cancer cells suppressed tumor growth by down-regulating tNOX and SIRT1, which was also seen in an in vivo xenograft study with tNOX-depleted melanoma cells. Taken together, our findings suggest that tNOX expression is important for the growth of melanoma cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo, and that inhibition of the tNOX-SIRT1 axis contributes to inducting ROS-dependent autophagy in melanoma cells.

Keywords: Autophagy, cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA), CETSA-pulse proteolysis, melanoma, reactive oxygen species (ROS), sirtuin 1 (silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog 1 or SIRT1), tumor-associated NADH oxidase (tNOX or ENOX2)

Introduction

Malignant melanoma accounts for approximately 5% of skin cancers; however, its high metastatic potential means that it accounts for the vast majority of all skin cancer deaths in the United States, with particularly high mortality seen in those diagnosed at a later stage [1,2]. Unfortunately, acquired drug resistance largely restricts the efficacy of chemotherapy in melanoma, resulting in disease progression and a poor long-term survival rate [3-5]. Accumulated evidence demonstrates that phytochemicals, such as capsaicin (8-methyl-N-vanillyl-6-nonenamide; the functional ingredient in chili peppers), can exhibit superior toxicity toward cancer cells over non-cancerous cells and may offer benefits as nutraceutical agents [6-11]. Indeed, capsaicin has long been known to diminish the growth of human and mouse melanoma cells [12-17]. However, we current lack direct and physical evidence linking the specific target(s) of capsaicin to its superior cytotoxicity. Thus, it is worth investigating novel cellular target(s) for capsaicin that have therapeutic potential, and assessing the relevant mechanism(s) of action in melanoma.

In previous work, we explored the distinct cellular impacts of capsaicin in different systems and identified a tumor-associated NADH oxidase (tNOX; ENOX2) that is hormone- and growth factor-stimulated in non-cancerous cells but constitutively activated in transformed/cancer cells [6,18]. Given that tNOX is commonly expressed in cancer/transformed but not non-cancerous cells, its downregulation has become an important premise to explain the preferential cytotoxicity of capsaicin toward cancerous cells, including those of human and mouse melanoma, breast, stomach, colon, lung, and bladder cancer [6,12,19-23]. Importantly, by utilizing cell lines from human lung tissues, we learned that capsaicin suppresses tNOX activity/expression to reduce intracellular NAD+ concentration and a NAD+-dependent SIRT1 deacetylase activity, resulting in augmented p53 acetylation as well as apoptosis in lung cancer cells [22]. We also showed that, conversely, capsaicin increased the intracellular NAD+/NADH ratio and SIRT1 deacetylase activity, decreasing Atg5 acetylation to trigger protective autophagy in MRC-5 cells lacking tNOX expression [22]. In addition to programmed cell death, it appears that capsaicin also acts on cell migration, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and cell cycle progression through modulation of the tNOX-SIRT1 axis [23,24].

The basis for determining the affinity of a ligand to its protein target is to examine the changes in protein stability because ligand binding enhances global stability of a protein. In this present study, to demonstrate that capsaicin directly targets tNOX in melanoma cancer cells, we performed a cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA) and obtained isothermal dose-response fingerprint (ITDRFCETSA) curves. The foundation for CETSA-based techniques relies on the concept that a target protein will be heat-stable in the presence of its ligand compound [25-30]. Moreover, an energy-based CETSA-pulse proteolysis was used for the target identification. Given that ligand binding enhances stability of target protein, pulse proteolysis assay empowers for quantitative determination of protein stability by exploiting the fact that folded and unfolded proteins are very different proteolysis susceptibilities [31,32]. Utilization of an excess of thermolysin to digest only unfolded tNOX proteins in equilibrium mixtures of folded and unfolded forms, we observed that the presence of capsaicin increased resistance to proteolysis of tNOX as its undigested/folded form was visualized by Western blot analysis. All of these various lines of evidence presented herein suggest that the direct interaction between capsaicin and tNOX resulted in tNOX degradation, which in turn triggered ROS-dependent autophagy in melanoma cells through enhanced ULK1 acetylation.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and reagents

Capsaicin (purity >95%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corporation (St. Louis, MO, USA). The anti-SIRT1, anti-phosphorylated Akt, anti-Atg5, anti-Bak, anti-Bax, anti-caspase 8, anti-caspase 9, anti-caspase 3, anti-acetylated Lysine, anti-mTOR, anti-phosphorylated mTOR, anti-PARP, anti-p53, anti-acetyl-p53, anti-phosphorylated-p53, and anti ULK1 antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Beverly, MA, USA). The anti-β-actin antibody was purchased from Millipore Corp. (Temecula, CA, USA). The anti-Akt antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The anti-Beclin 1, anti-Atg7, and anti-LC3 antibodies were obtained from Novus biologicals (Centennial, CO, USA). The commercially available anti-COVA1 (a.k.a. tNOX, ENOX2) antibody from Proteintech (Rosemont, IL, USA) was used for immunoprecipitation. The antisera to tNOX used for immunoblotting were produced as described previously [33]. If not otherwise specified, the anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG antibodies and other chemicals were purchased from the Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO, USA), unless otherwise specified.

B16F10 (mouse melanoma) and A375 (human melanoma) cells grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), were obtained from the Bioresource Collection and Research Center (BCRC, Hsinchu, Taiwan). Media were fortified with 10% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin and 50 µg/ml streptomycin. Cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air, with replacing media every 2-3 days. Cells were exposed to different concentrations of capsaicin (ethanol as vehicle), as described in the text, or with the same volume of ethanol (vehicle control).

tNOX short hairpin RNA was produced in the pCDNA-HU6 plasmid, a generous gift from Dr. J.T. Chang (Chung Shan Medical University) [34]. Two oligonucleotides targeting tNOX (shRNA-F: GATCCGAGGAAATTCGCAACATTCATTTCAAGAGAA and shRNA-R: AGCTTAAAAAGAGGAAATTCGCAACATTCATTCTCTTGAAA) were synthesized, treated with T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) and ligated to a pCDNA-HU6 vector. For the negative control, a set of random-sequence oligonucleotides was utilized. A375 cells were cultured in 10-cm dishes for 12-16 h, and then transfected with tNOX shRNA or control shRNA using the jet PEI transfection reagent (Polyplus-transfection SA, Illkirch Cedex, France), based on the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Alternatively, ON-TARGETplus tNOX (ENOX2) siRNA and negative control siRNA were purchased Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Briefly, A375 cells were seeded in 10-cm dishes, allowed attaching overnight, and then transfected with tNOX siRNA or control siRNA using the Lipofectamin RNAiMAX Reagent (Gibco/BRL Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Constant monitoring of cell growth by cell impedance measurements

In order to constantly observe changes in cell growth, cells (104 cells/well) were cultured onto E-plates and waited for 30 min at room temperature, after which E-plates were settled into the xCELLigence System (Roche, Mannhein, Germany). Cells were cultured for one day before exposed to capsaicin or ethanol and impedance was evaluated every hour, as previously described [22]. Cell impedance is defined by the cell index (CI) = (Zi-Z0) [Ohm]/15 [Ohm], where Z0 is background resistance and Zi is the resistance at an individual time point. The definition of a normalized cell index is calculated as the cell index at a certain time point (CIti) divided by the cell index at the normalization time point (CInml_time).

Cell viability assay

Cells (5 × 103) were cultured in 96-well culture plates and allowed to adhere for 12-16 h at 37°C in growth medium containing 10% FBS. Cells were exposed to different concentrations of capsaicin for 24, 48, 72 hours, and at the end of each experiment, cell viability was evaluated using a rapid, MTS-based colorimetric assay (CellTiter 96 cell proliferation assay kit; Promega, Madison, WI, USA) based on the instructions from the manufacturer. All experiments were conducted in no less than triplicate on three separate occasions. Data are presented as means ± SDs.

Clonogenic assay

Onto each 6-cm dish, two hundred cells were cultured in growth medium with various concentrations of capsaicin at least 10 days. At the end of experiment, colonies were fixed in 1.25% glutaraldehyde at room temperature for 30 minutes, washed with distilled water and colored with a 0.05% methylene blue mixture. The number of colonies was determined and documented.

Apoptosis determination

An Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA) was utilized for the measurement of apoptosis. Cells cultured in 6-cm culture dishes were trypsinized and harvested by centrifugation. After centrifugation, the cell pellet was rinsed with PBS, resuspended in 1 × binding buffer and colored with annexin V-FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate), based on the instructions from the manufacturer. Additionally, cells were colored with propidium iodide (PI) to determine necrotic or late apoptotic cells. The percent of viable (FITC-negative and PI-negative), early apoptotic (FITC-positive and PI-negative), late apoptotic (FITC-positive and PI-positive) and necrotic (FITC-negative and PI-positive) cells was evaluated by a Beckman Coulter FC500 flow cytometer. The results are expressed as a percentage of total cells.

Autophagy determination

Autophagosomes-acidic intracellular compartments that mediate the degradation of cytoplasmic materials during autophagy-were seen by coloring with Acridine Orange (AO; Sigma Chemical Co.). At the end of each experiment, cells were centrifuged, rinsed with PBS, and colored with 2 mg/ml AO for 10 min at 37°C. After incubation, the AO-stained cells were rinsed with PBS, trypsinized, and examined using a Beckman Coulter FC500 flow cytometer. The results are recorded as a percentage of total cells.

Visualization of autophagosome formation using EGFP-LC3

For autophagy experiments, A375 cells were transfected with a pEGFP-LC3 construct (a generous gift from Dr. Tamotsu Yoshimori, Osaka University, Japan) using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent according to the instructions from the manufacturer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) [35]. A375-EGFP-LC3 cells were either starved or exposed to capsaicin or ethanol and autophagosomes formation was visualized.

Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA from melanoma cancer cells was purified using the TRIzol reagent (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA). First strand cDNA was made from 1 μg of total RNA by Superscript II (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD, USA). The following primers sets were utilized for PCR amplifications: tNOX, 5’-GCTGTGCTTCTAGGCTGTGT-3’ (sense) and 5’-TTATCAAGACGGTGCAAGTAGGA-3’ (antisense); SIRT1, 5’-GCCAGTGGATTCGCTCTTT-3’ (sense) and 5’-GCTCTATCCTCCTCATCACTTTCAC-3’ (antisense); and β-actin, 5’-ACTCACCTTGGTGGTGCATA-3’ (sense) and 5’-ACACCTTGATGGGAAAGGTGG-3’ (antisense). The experimental conditions for PCR were: 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by a final extension of 5 min at 72°C. The generated PCR products were analyzed by 1.4% agarose gels electrophoresis and seen by ethidium bromide staining.

Determination of oxidative stress (also reactive oxygen species, ROS)

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) was examined by determining the generation of intracellular of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), utilizing 5-(6)-carboxy-2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (carboxy-H2DCFDA) staining. The non-ionic and nonpolar cell-penetrating H2-DCFDA fluorescent dye is hydrolyzed to nonfluorescent H2-DCF by esterases in the cells. H2-DCF is quickly oxidized to DCF with high fluorescent in the existence of peroxide. In short, after exposure to capsaicin, cells (2 × 105) were rinsed with PBS and treated with 5 μM H2DCFDA in binding buffer for 30 min. The cells were then harvested by trypsinization and centrifugation, rinsed with PBS, centrifuged at 200 × g for 5 min and examined promptly by a Beckman Coulter FC500 flow cytometer.

SIRT1 activity measurement

The cellular SIRT1 activity was determined by a SIRT1 Activity Assay Kit (Fluorometric) (Abcam Inc. Cambridge, MA, USA). Briefly, 1 × 105 cells (either untreated or capsaicin-treated for 24 h) were washed, harvested and resuspended in 1 mL of lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM NaCl, 15 mM MgCl2, 250 mM sucrose, 0.5% NP-40, 0.1 mM EGTA). Cell lysates were sonicated 4 times for 5 seconds each on ice, and were centrifuged for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was then used for the measurement of SIRT1 activity based on the instructions from the manufacturer.

Cellular target identification of capsaicin by cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA)

Intracellular tNOX as cellular target of capsaicin was established by CETSA. Two sets of samples were processed from capsaicin-exposed and control groups. For each set, 2 × 107 cells were cultured in a 10-cm dish for a day and then were pretreated with 10 μM MG132 for 1 h to inhibit proteasomal activity, rinsed with PBS, digested with trypsin, and harvested by centrifugation. The centrifugation was set to 12,000 rpm for 3 min at room temperature. After centrifugation, cell pellets were lightly resuspended with 1 mL of PBS, and the samples were centrifuged again at 7,500 rpm for 3 min at room temperature. The pellets were resuspended with 1 mL of PBS containing 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 10 ng/ml leupeptin, and 10 μg/ml aprotinin. The cell pallets were then moved to new tubes and subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles; for each cycle, samples were immersed in liquid nitrogen for 3 min, heated in a dry heating block to 37°C for 3 min, and vortexed shortly. Capsaicin was added to the tested sample set with a final concentration of 2 mM; on the other hand, the same volume of vesicle solvent was added in the control sample set. The samples were warmed at 37°C for 1 h and allocated to 100 μl aliquots. Pairs comprising one control tube and one tested tube were heated at 40°C, 43°C, 46°C, 49°C, 52°C, 55°C, 58°C, or 61°C for 3 min. Centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C was then used to separate insoluble proteins, and the supernatants with soluble proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE and protein analysis using antisera to tNOX [33,36]. β-actin was used as the control.

We also performed an isothermal dose-response fingerprint (ITDRFCETSA) comparable to that of the CETSA melting curve experiments as described above. Cells were seeded in 60 mm cultured dishes. After 24 h of culture, the cells were pretreated with 10 μM MG132 and exposed to different final concentrations of 0.001, 0.01, 0.05, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 10, 100, 200 μM capsaicin for 1 h. After the treatment, samples were rinsed with PBS, digested with trypsin, and harvested with centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 2 min at room temperature. The samples were lightly resuspended with 1 mL of PBS, and then centrifuged at 7,500 rpm for 3 min at room temperature, and resuspended with PBS containing 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 10 ng/ml leupeptin, and 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and then subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles. For each cycle, samples were immersed in liquid nitrogen for 3 min, warmed in a dry heater block to 25°C for 3 min, and vortexed shortly. The samples were then heated at 54°C for 3 min and cooled for 3 min at room temperature. Insoluble proteins were separated by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C, and the supernatants with soluble proteins were used for SDS-PAGE and protein analysis using antisera to tNOX. β-actin was used as the internal loading control.

CETSA-pulse proteolysis

Two sets of samples were processed from capsaicin-exposed and control groups and prepared as described above in the cellular thermal shift assay experiments to the point of heating samples at different temperature for 3 min and placed on ice. Proteolysis was started by adding selected protease, thermolysin to reach the final concentration of 0.2 mg/mL. After 1 min of reaction to digest the unfolded fraction of proteins, EDTA was added to the sample to be 20 mM for quenching thermolysin activity. Samples were then centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C was then used to separate insoluble proteins, and the supernatants with soluble proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using antisera to tNOX [33,36]. β-actin was used as the control.

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation

Cell extracts were handled in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 10 ng/ml leupeptin, 10 µg/ml aprotinin). Volumes of cell extract comprising equivalent weights of proteins (40 µg/lane) were subjected to SDS-PAGE gels, and separated proteins were then transferred to PVDF membranes (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% of non-fat milk, rinsed with washing buffer, and probed with primary antibody overnight. The membranes were then washed to eliminate unbound primary antibody, incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 2 hours. After incubation, the blots were washed again and developed using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents, based on the protocol from the manufacturer (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

For immunoprecipitation, protein extracts from 100 mm dishes were incubated with 60 μl of Protein G Agarose Beads (for rabbit antibodies) for 1 h at 4°C in rotation for pre-clearing. The ULK1 antibody or control IgG was incubated onto beads in 500 μl of lysis buffer for overnight in rotation at 4°C. Beads were precipitated by centrifugation at 3000 rpm, 2 min at 4°C and 80 μl of supernatants were collected for input total lysates. Beads were washed three times with lysis buffer and samples were prepared for Western blotting analysis.

In vivo xenograft studies

Specific pathogen free (SPF) female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the National Laboratory Animal Center (Taipei, Taiwan). The animal use protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of National Chung Hsing University (Taichung, Taiwan). Mice were subcutaneously inoculated with 100 μl of a B16F10 cell mixture containing 2 × 105 live cells in PBS. In accordance with the 3R’s, the tumor-bearing animals were causally divided into two groups (n=4 per group) when the tumor mass reached an average diameter of 0.5-1 cm. Group 1 mice were intratumorally injected with vehicle buffer (1.12% ethanol in 1X PBS) as untreated control (VC group). Group 2 mice were intratumorally treated with 200 μg capsaicin in vehicle buffer (Cap group). Intratumoral therapy was performed two times at an interval of one week. The tumor size was recorded every 2-3 days and the tumor volume was calculated using the formula: length × width2 × 0.5. Mice were euthanized at 4 days after the final treatment. The significance of differences in tumor size was determined by one-tailed Student’s t test.

To confirm the contribution of tNOX to tumor growth, 1 × 106 B16F10 mouse melanoma cells transfected with either control (control-i) or tNOX (tNOX-i) shRNA were used for inoculation. Eight-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were causally divided into two groups and subcutaneously inoculated with tumor cells at the right flank: Group-1 mice (n=3) were injected with control-i cells as a control group and group-2 mice (n=3) were injected with tNOX-i cells. Fourteen days after tumor cell injection, mice were euthanized, the tumor mass was quickly removed, and the mass was weighed.

Statistical analysis

All in vitro experiments were performed no less than three times and all in vivo experiments were conducted with at least three animals. The results of each experiment are expressed as the means ± SEs. Between-group comparisons were calculated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by an appropriate post-hoc test. A statistically significant difference was defined as P value <0.05.

Results

Capsaicin suppresses the growth of mouse and human melanoma cells

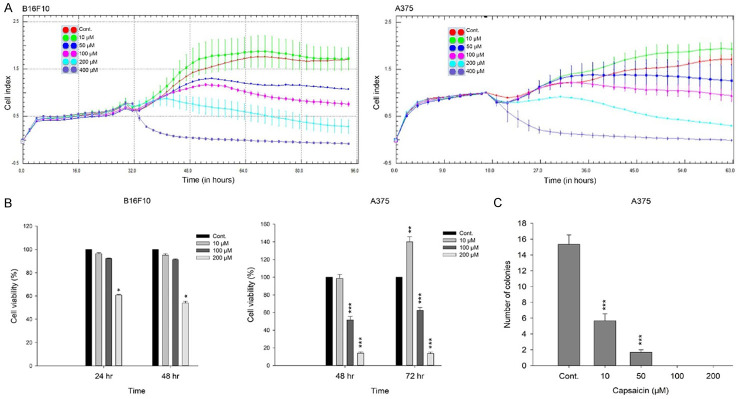

We first set out to determine the effect of capsaicin on the growth of melanoma cells, utilizing both mouse (B16F10) and human (A375) cells by dynamically monitoring cell impedance, and displayed the results as cell index (CI) values [37,38]. Our results suggested that capsaicin attenuated the growth of these two cell lines with comparable degrees of cytotoxicity at concentrations above 10 μM (Figure 1A). We observed a slight rise in the proliferation of these cancer cell lines when exposed to 10 μM capsaicin, which was similar to a previous reported finding [21]. Consistent results were also obtained with a cell viability assay, which indicated that capsaicin induced dose- and time-dependent decreases in melanoma cell viability, except at 10 μM for the A375 cells (Figure 1B). However, when we used a colony-forming assay to examine the longer-term effect, we found that capsaicin markedly diminished A375 cell proliferation at 10 and 50 μM, and completely blocked cell proliferation at 100 and 200 μM (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Capsaicin attenuates the growth of melanoma cells. A. Capsaicin-mediated cell proliferation was dynamically monitoring by impedance measurements in B16F10 and A375 cells, as described in the Materials and Methods. Shown are normalized cell index values measured. B. Cells were treated with various concentrations of capsaicin for 24, 48, or 72 h and cell viability was determined by MTS-based assays. Values (means ± SDs) are from no less than three independent experiments. There was a significant difference observed in cell viability in experimental groups as opposed to the controls (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001). C. A375 cells were treated with various concentrations of capsaicin and allowed to form colonies. Colony numbers were determined and documented. Values (means ± SDs) are from three independent experiments. There was a significant reduction in cells treated with capsaicin compared to the controls (***P<0.001).

Capsaicin induces ROS-dependent autophagy but not apoptosis

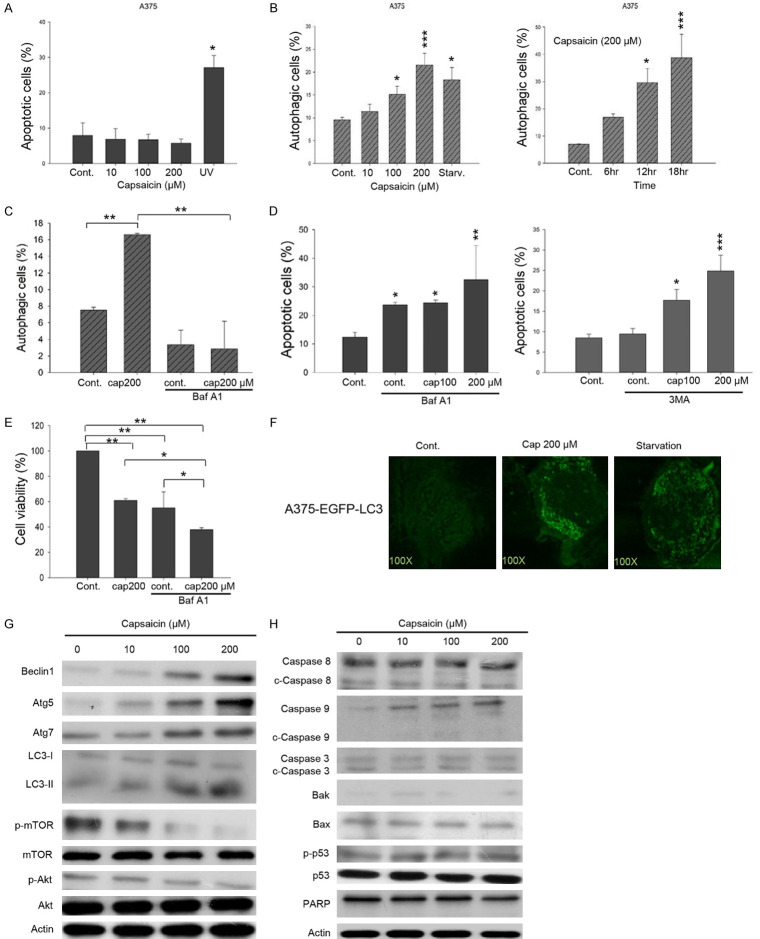

Given that capsaicin has long been recognized as a nutraceutical agent for its apoptotic activity, we next validated the cellular outcomes in melanoma cells exposed to capsaicin. However, our results suggested that capsaicin was unable to induce apoptosis in A375 cells even at 200 μM (Figure 2A). Instead, it appeared to induce autophagy in a concentration- and time-dependent fashion (Figure 2B). Pretreatment with the autophagy inhibitor bafilomycin A1 (Baf A1), markedly reduced the capsaicin-induced autophagy (Figure 2C). Furthermore, the pretreatment with Baf A1 effectively sensitized A375 cells to apoptosis in the control group and the combination of 200 μM capsaicin and Baf A1 further enhanced apoptosis significantly (Figure 2D, left panel). Similar results were also observed with pretreatment with 3-methyladenine (3-MA), an inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase involved in the regulation of autophagy (Figure 2D, right panel). Consistent with Figure 2D, autophagy inhibition by Baf A1 also markedly reduced cell viability in the controls, conceivably through apoptosis induction (Figure 2E). Another possibility is that spontaneous autophagy could promote cell survival and the inhibition of autophagy thus decreases cell viability, as also evidenced by others [39,40]. In this regard, unsurprisingly, the combination of Baf A1 and 200 μM capsaicin provoked more apoptosis to further diminish cell viability (Figure 2E). To investigate autophagy induced by capsaicin, we exogenously expressed a fusion protein of enhanced green fluorescent protein and the autophagy marker microtubule associated light chain 3 protein (EGFP-LC3) in A375 cells. Our data illustrated that capsaicin treatment promoted autophagosomes formation as green punctuate dots, similar to those seen in cells with starvation (Figure 2F). Protein analysis showed that capsaicin-induced autophagy involved the up-regulation of the autophagy-related proteins Beclin 1, Atg5, Atg7, and the level of cleaved LC-3 II, and that this was accompanied by a decrease in the activation/phosphorylation of mTOR and Akt (Figure 2G). On the contrary, apoptosis markers were unchanged by capsaicin exposure, including cleaved/activated caspases, the levels of the pro-apoptotic proteins Bak, Bax, p53, and the cleavage of PARP (Figure 2H).

Figure 2.

Capsaicin favorably triggers autophagy but not apoptosis in A375 melanoma cells. A. Cells were treated with capsaicin or ethanol for 24 hours. The percentage of apoptotic cells was evaluated by flow-cytometry, and the results are presented as the percentage of apoptotic cells. Values (means ± SDs) are from at least three independent experiments (*P<0.05). B. Cells were exposed to various concentrations of capsaicin/ethanol for 15 hours or 200 μM of capsaicin for different time length. Autophagy was determined by AO staining using flow cytometry, analysis and the results are expressed as a percentage of autophagic cells. Values (means ± SDs) are from at least three independent experiments (*P<0.05, ***P<0.001). C. Cells were pre-treated with 10 nM Baf A1 for 1 h before exposed to capsaicin for 15 h. Autophagy was determined by AO staining using flow cytometry, analysis and the results are expressed as a percentage of autophagic cells. Values (means ± SDs) are from at least three independent experiments (**P<0.01). D. Cells were pretreated with 10 nM Baf A1 (left panel) or 10 μM 3-MA (right panel) for 1 h before treated with capsaicin or ethanol for 24 hours. The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by flow cytometry, and the results are expressed as a percentage of apoptotic cells. Values (means ± SDs) are from at least three independent experiments (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001). E. Cells were pre-treated with 10 nM Baf A1 for 1 h before exposed to various concentrations of capsaicin for 24 h and cell viability was determined by MTS-based assays. Values (means ± SDs) are from no less than three independent experiments. There was a significant difference observed in cell viability in experimental groups as opposed to the controls (*P<0.05, **P<0.01). F. A375-EGFP-LC3 cells were serum starved or treated with capsaicin or ethanol for 15 hours. EGFP fluorescence was observed under a fluorescence microscopy. G, H. A375 cells were exposed to capsaicin or ethanol for various concentrations and aliquots of cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed for protein expression by Western blotting. β-actin was used as an internal loading control to monitor for equal loading. Representative images are provided from at least three independent experiments.

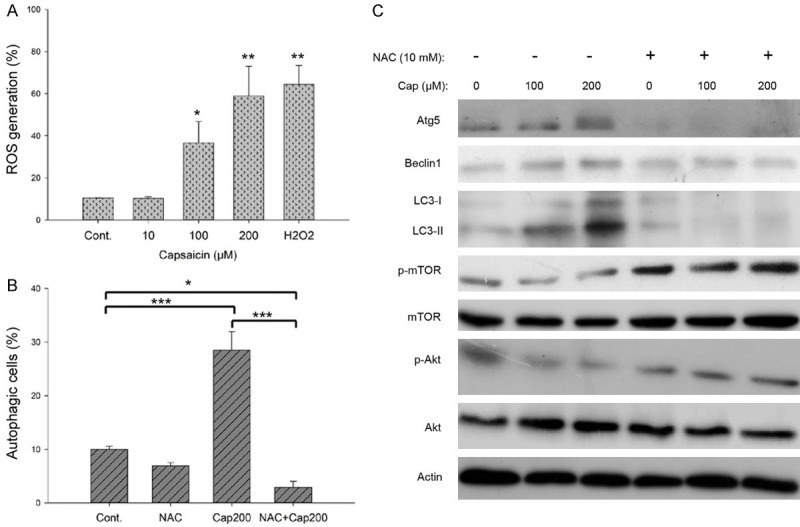

Using the fluorescent dye, H2DCFDA, we observed that capsaicin markedly provoked the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) at 100 and 200 μM (Figure 3A), as proposed by many other studies [41-43]. Pretreatment with the ROS scavenger, N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), effectively attenuated capsaicin-mediated autophagy at 200 μM (Figure 3B). Furthermore, our protein analysis validated that the capsaicin-mediated changes in autophagy-related proteins were reversed by pretreatment with NAC, suggesting that capsaicin-induced autophagy was dependent of ROS signaling (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Capsaicin-induced autophagy is dependent of ROS signaling in A375 cells. A. The percent change in intracellular ROS generation was evaluated after cells were treated with various concentrations of capsaicin for 1 h. Values (means ± SDs) are from no less than three independent experiments (*P<0.05, ***P<0.001). B. Cells were pretreated with or without 10 mM NAC for 1 h before exposure to 200 μM capsaicin or ethanol for 18 hours. The percentage of autophagic cells was assessed by flow cytometry, and the results are expressed as a percentage of autophagic cells. Values (means ± SDs) are from at least three independent experiments (*P<0.05, ***P<0.001). C. Cells were pretreated with or without 10 mM NAC for 1 h before exposure to capsaicin or ethanol for 24 hours. Aliquots of cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed for protein expression by Western blotting. β-actin was used as an internal loading control to monitor for equal loading. Representative images are shown from at least three independent experiments.

Capsaicin directly binds to tNOX, as indicated by cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) and CETSA-pulse proteolysis

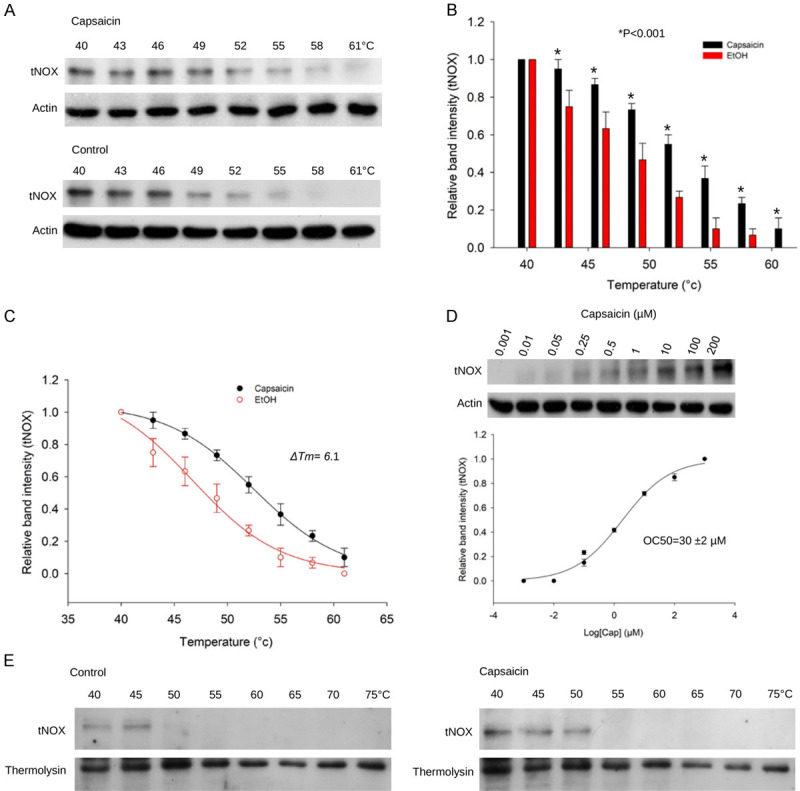

Capsaicin has long been known to suppress plasma membrane NADH oxidase (a.k.a tNOX; ENOX2) and the growth of human and mouse melanoma cells [12]. The previous study mainly correlated the inhibition of NADH oxidase activity with attenuation of cancer cell growth, but did not reveal the molecular events contributing to this capsaicin-mediated suppression. To shed light on the action mechanism of capsaicin, we next examined whether there is a direct interaction between capsaicin and tNOX to regulate autophagy in melanoma cells. The basis for determining the affinity of a ligand to its protein target is to examine the changes in protein stability because ligand binding enhances global stability of a protein. Given that the interaction between a ligand and its target protein enhances its heat resistance, a cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA) was conducted to examine the direct targeting between capsaicin and target proteins. Interestingly, in the presence of capsaicin, tNOX apparently precipitated at higher temperatures compared with that seen in control A375 cells (Figure 4A). The relative tNOX intensity observed at all temperatures tested was significantly higher in capsaicin-exposed cells compared to controls (Figure 4B). Moreover, the melting temperature values (T m; the temperature at which 50% of proteins become unfolded and quickly precipitated by heat) derived from the plot of thermal melting curves showed that the addition of capsaicin increased the parameter by 6.1 degrees, from 46.5°C (control) to 52.6°C (exposed to capsaicin) (Figure 4C), suggesting that there is direct binding between capsaicin and tNOX. Furthermore, using isothermal dose-response fingerprint curves (ITDRFCETSA), we examined the dose-response relationship between capsaicin and the heat stability of tNOX; this experiment was performed at 54°C, as most tNOX proteins would be denatured and precipitated unless they were thermally stabilized by binding to the ligand, capsaicin. Indeed, capsaicin dose-dependently increased the stability of tNOX, with an OC50 value of 30 μM for A375 melanoma cells (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

CETSA-based validation of direct binding between capsaicin and tNOX protein. A. The immunoblot intensity of tNOX in A375 cells in the presence and absence of capsaicin in the CETSA experiments as described in the Material and Methods. Aliquots of cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed for protein expression by Western blotting. β-actin was used as an internal loading control to monitor for equal loading. Representative images are shown. B. The quantification of relative intensity of tNOX protein in the presence and absence of capsaicin versus increased temperature from three independent experiments (*P<0.05). C. CETSA-melting curves of tNOX in the presence and absence of capsaicin as described in the Material and Methods in A375 cells. The immunoblot intensity was normalized to the intensity of the 40°C sample. D. A375 cells were incubated with various concentrations of capsaicin at 54°C as described in the Material and Methods. Dose-dependent thermal stability change of tNOX upon capsaicin treatment was evaluated after heating samples at 54°C for 3 min. The band intensities of tNOX were normalized with respect to the intensity of actin. Representative images are shown. E. The immunoblot intensity of tNOX in A375 cells in the presence and absence of capsaicin in the CETSA-pulse proteolysis experiments as described in the Material and Methods. Aliquots of cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed for protein expression by Western blotting. Thermolysin was used as a negative control. Representative images are shown.

In addition to CETSA-based assays, we also incorporated an energy-based pulse proteolysis assay to further validate the direct targeting of tNOX and capsaicin. Given that ligand binding enhances stability of target protein, pulse proteolysis assay empowers for quantitative determination of protein stability by exploiting the fact that the protein should not be markedly digested in folded configuration compared to its unfolded form [31,32]. Utilization of an excess of thermolysin to digest only unfolded tNOX proteins in equilibrium mixtures of folded and unfolded configurations, we observed that capsaicin binding enhanced resistance to proteolysis of tNOX as its undigested/folded form was visualized by Western blot analysis (Figure 4E).

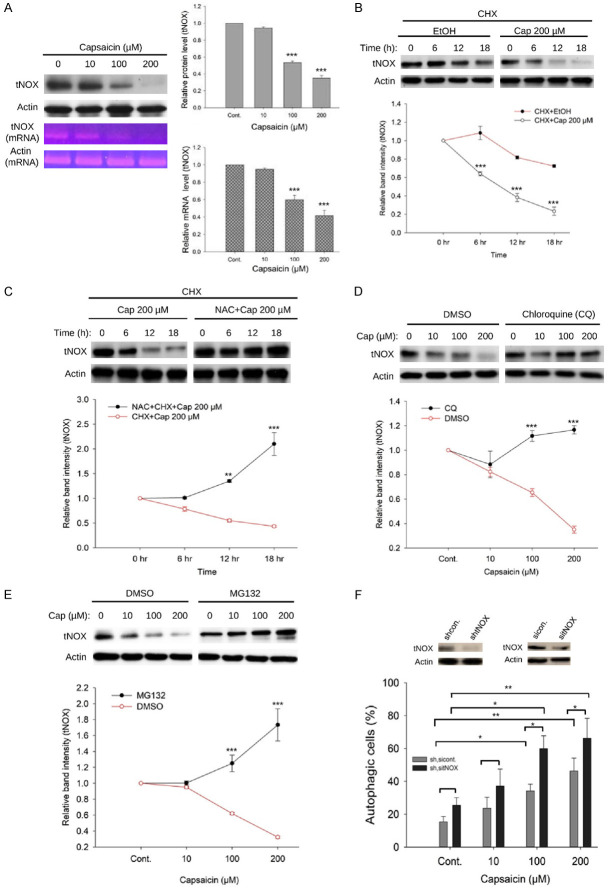

Capsaicin reduces tNOX expression at the protein and transcriptional levels

Based on our observation that capsaicin can directly bind to cellular tNOX protein in melanoma cells, we next examined the cellular impact of this interaction. We found that capsaicin concentration-dependently downregulated tNOX in A375 cells, and that this was seen at both protein and transcriptional levels (Figure 5A). Given that the POU domain transcription factor, POU3F2, was shown to positively regulate tNOX expression in gastric cancer cells and, through suppression of POU3F2, capsaicin attenuated tNOX expression in bladder cancer cells [44], we decided not to launch an in-depth investigation into the regulatory mechanism at transcriptional level. Instead, pretreatment with the protein-synthesis inhibitor, revealed that the half-life of tNOX in A375 cells was significantly reduced by 200 μM capsaicin starting at 6 h (Figure 5B). ROS signaling seemed to play a key role in capsaicin-inhibited tNOX expression as evidenced by the marked enhancement of tNOX stability seen in cultures pretreated with NAC (Figure 5C). Pretreatment with the lysosome inhibitor, chloroquine (CQ), profoundly enhanced tNOX expression in A375 cells exposed to capsaicin (Figure 5D), indicating that lysosomal degradation might be involved in capsaicin-induced tNOX downregulation. Pretreatment with the proteasome inhibitor, MG132, markedly reversed tNOX expression in A375 cells exposed to capsaicin (Figure 5E), indicating that capsaicin-induced tNOX downregulation might also be through proteasomal degradation. We further examined the effect of tNOX depletion in A375 cells subjected to RNA interference, including small interfering RNA (siRNA) and short hairpin RNA (shRNA), and found that tNOX knockdown significantly enhanced the autophagy induced by 100 and 200 μM capsaicin, but did not induce spontaneous autophagy in the absence of capsaicin (Figure 5F).

Figure 5.

Capsaicin-induced tNOX downregulation is associated with proteasomal and lysosomal degradation in A375 cells. A. Capsaicin significantly reduced tNOX expression at translational level analyzed by Western blotting and at transcriptional level determined by RT-PCR. B. Capsaicin (200 μM) decreased tNOX stability determined by a cycloheximide-chase assay in a time-dependent fashion. C. Capsaicin-mediated tNOX downregulation was restored by the ROS scavenger, NAC. D. Capsaicin-induced tNOX downregulation was reverted by chloroquine (CQ), the lysosome inhibitor. E. Capsaicin-mediated tNOX downregulation was reinstated by the proteasome inhibitor, MG132. Aliquots of cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting. β-Actin was detected as an internal control. Representative images are shown. Values (means ± SDs) are from at least three independent experiments (**P<0.01, ***P<0.001). F. Two types of RNA interference-mediated tNOX depletion were conducted in A375 cells, including siRNA and shRNA. These cells were exposed to different concentrations of capsaicin or ethanol for 24 h, and the percentage of autophagic cells was examined by flow cytometry. The presented values (mean ± SDs) represent at least five independent experiments (*P<0.05 or **P<0.01 for tNOX-depleted cells vs. controls or capsaicin-treated vs. controls).

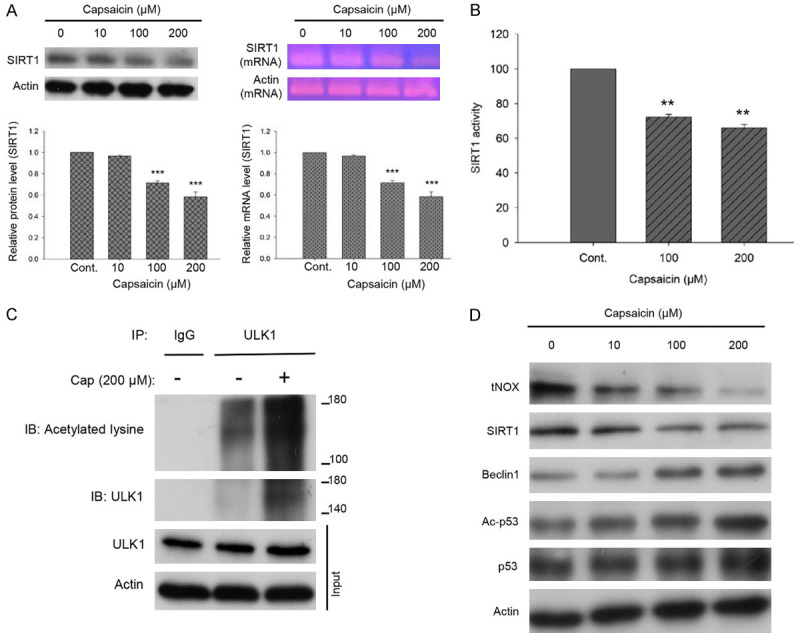

Capsaicin induces autophagy by suppressing tNOX-SIRT1 deacetylase activity to enhance ULK1 acetylation

Previous studies linked the suppression of tNOX activity with the cancer cell growth-attenuating activity of capsaicin [6,12], and repression of tNOX activity was reported to reduce the intracellular NAD+ concentration [22]. We next questioned whether a NAD+-dependent SIRT1 deacetylase could act as a tNOX-mediated NAD+ generation-regulated switch for autophagy. We found that capsaicin attenuated SIRT1 expression at both transcriptional and translational levels in A375 cells (Figure 6A). Furthermore, 100 and 200 μM capsaicin significantly inhibited cellular SIRT1 deacetylase activity in A375 cells, as assessed using a fluorometric SIRT1 activity assay (Figure 6B). We next focused on the autophagy-related pathway, using immunoprecipitation to reveal that ULK1 acetylation was augmented in our system, possibly through capsaicin-inhibited SIRT1 activity/expression (Figure 6C). Interestingly, our data suggested that the capsaicin-induced suppression of tNOX expression was accompanied by a decrease in SIRT1 expression in A375 cells (Figure 6D), as reported previously in other cancer cell types [22,23]. Other cell death regulation-related downstream targets of SIRT1 were also examined: We found that p53 acetylation was increased, providing further evidence that capsaicin induced autophagy, not apoptosis, in our system (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Capsaicin inhibits SIRT1 expression and enzymatic activity in A375 cells. A. Capsaicin significantly induced SIRT1 downregulation at the translational level analyzed by Western blotting and at the transcriptional level determined by RT-PCR. B. Capsaicin suppressed cellular SIRT1 activity analyzed by a SIRT1 Activity Assay Kit (Fluorometric) with control or capsaicin-exposed A375 cell lysates. Values (mean ± SDs) are from three independent experiments (***P<0.001). C. The lysates of A375 cells were immunoprecipitated with nonimmune IgG or an antibody against ULK1, and the bound proteins were detected by Western blotting with pan-acetylated lysine or ULK1 antibodies. D. A375 cells were exposed to different concentrations of capsaicin or ethanol for 24 hours. Aliquots of cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed for protein expression by Western blotting. β-actin was used as an internal loading control to monitor for equal loading. Representative images are shown from at least three independent experiments.

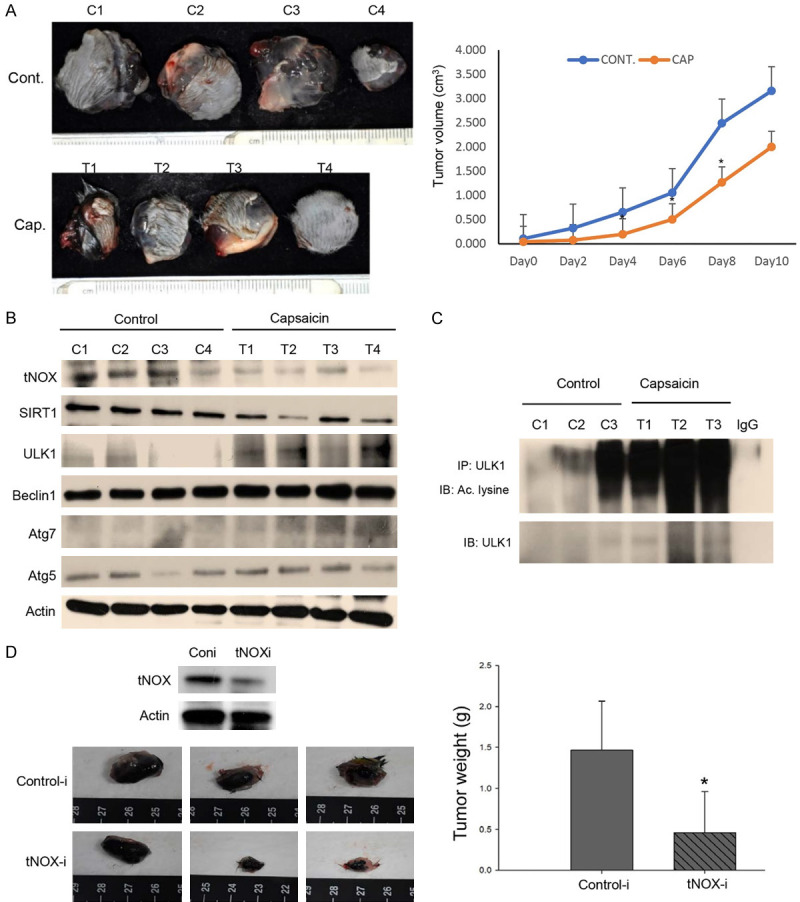

Capsaicin-induced inhibition of tNOX or depletion of tNOX limit tumor growth in vivo

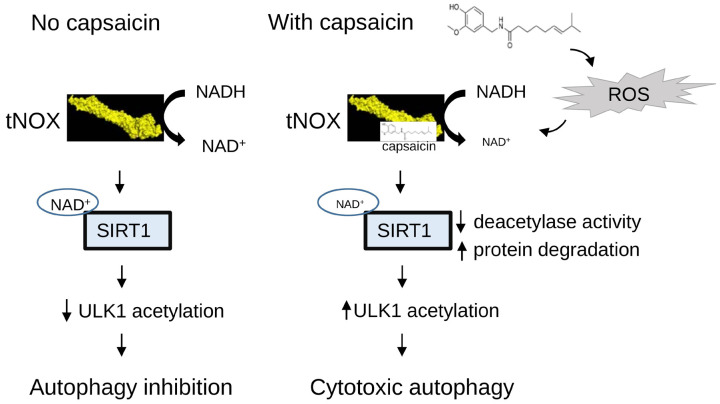

To determine whether capsaicin exerts an inhibitory activity on melanoma cancer in vivo, mice were inoculated with B16F10 cells. Tumor-bearing mice with average tumor diameters of around 0.5-1 cm were causally split into two groups and intratumorally injected with either 200 μg capsaicin in vehicle buffer or buffer only. Mice were terminated at Day 10 and we found that capsaicin effectively lessened the tumor size (Figure 7A). Furthermore, protein analysis of the tumor tissues from the control and capsaicin-treated groups revealed that capsaicin treatment effectively reduced the expression of tNOX/SIRT1 expression (Figure 7B). Consistent with the data from the in vitro studies, we also observed that the ULK1 acetylation level was enhanced in the tissues of animals treated with capsaicin compared with those from control animals (Figure 7C). We next explored the involvement of tNOX in melanoma xenograft experiments utilizing RNA interference (RNAi) technology in B16F10 cells. tNOX-specific shRNA effectively attenuated tNOX expression in B16F10 cells compared to the controls (Figure 7D). The shRNA-transfected melanoma cells were injected into randomized C57BL/6 mice for an in vivo study. At the end of experiments, we found that average tumor mass grown in mice with tNOX-specific shRNA-transfected cells was markedly reduced compared to that of the control group, suggesting that tNOX depletion decreased the ability of melanoma cells to induce tumor growth in vivo (Figure 7D). Together, our findings suggest that capsaicin exerts its anticancer properties by directly targeting and enhancing the degradation of tNOX to inhibit NADH oxidation and SIRT1 deacetylase activity. In melanoma cells, through enhancement of ULK acetylation, capsaicin triggers autophagy dependent of ROS signaling (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

In vivo verification for capsaicin-reduced tNOX and tNOX-depletion suppresses melanoma tumor growth. A. In a tumor-bearing mouse xenograft model, control mice were intratumorally injected with vehicle buffer and treatment group mice were intratumorally treated with 200 μg capsaicin as described in Materials and Methods. The morphology of the tumor tissues excised from tumor-bearing mice (top panel) and quantitative analysis of xenografted tumor volume during the treatment period (bottom panel) are shown. B. Tissues from two sets of tumor-bearing mice were grounded and prepared for Western blotting analysis. β-actin was used as an internal loading control to monitor for equal loading. C. The lysates of tumor tissues were immunoprecipitated with nonimmune IgG or an antibody against ULK1, and the bound proteins were detected by Western blotting with pan-acetylated lysine. D. In another mouse xenograft model, B16F10 cells transfected with either control (control-i) or tNOX (tNOX-i) shRNA were subcutaneously injected into mice. The morphology of the tumor tissues excised from tumor-bearing mice (top panel) and quantitative analysis of xenografted tumor weights from two sets of mice are shown.

Figure 8.

The graphical illustration of the pathway associated with cytotoxic response of melanoma cells toward capsaicin is shown.

Discussion

Capsaicin can be considered a nutraceutical, which is defined as any food component that has medical benefit, such as in the prevention and treatment of disease [45,46]. An emerging body of evidence suggests that capsaicin suppresses the growth of melanoma cells. This has been reported to act through induction of both apoptosis and autophagy [10], downregulation of Bcl-2 with enhanced apoptosis [15], downregulation of IL-8 with reduced cell proliferation [13], and suppression of B16F10 cell migration via PI3K/Akt/Rac1 pathway [16]. Unsurprisingly, capsaicin has been used as a prototype for the design and synthesis of analogs aimed at inducing selective apoptosis in melanoma cells [47]. Capsaicin has also been shown to have a synergistic effect when combined with other drugs: It has been shown to further delay tumor growth in a dose-dependent fashion in mice with lung (LLC), bladder (MBT-2), and melanoma (B16F10) cancers [48]. Consistent with the previous reports, we herein demonstrate that capsaicin reduces the growth of melanoma cells in vitro and in vivo and further show for the first time that this occur via inhibition of the tNOX-SIRT1 axis and the subsequent induction of cytotoxic autophagy. The therapeutic efficiency of capsaicin was not ideal in our animal studies, but our further experiments revealed that a NAD+-dependent SIRT1 deacetylase activity appears to act as an orchestrated switch under regulation of tNOX-mediated NAD+ generation to trigger cytotoxic autophagy via enhanced ULK1 acetylation. Thus, capsaicin can be considered as a unique candidate drug with specific intercellular protein targets (tNOX and SIRT1) for melanoma treatment.

Recent efforts to quantify the engagement between an unlabeled drug and a cellular protein target have shed lights on the action mechanisms of drugs. An example of such a technique is CETSA, which relies on the observation that ligand binding strengthens the thermal stability of a target protein [26,27]. The preferential cytotoxicity of capsaicin had been long linked with tNOX in melanoma cells [12], but we previously lacked any direct physical evidence supporting their undeviating engagement. Using CETSA, we show that intracellular tNOX engages directly with capsaicin in T24 bladder cancer cells [24]. With the advantage of ITDRFCETSA, we provide extended evidence of capsaicin-tNOX binding in oral cancer cells [49]. Here, together with CETSA and ITDRFCETSA, we also incorporate an energy-based CETSA-pulse proteolysis assay to furthermore validate the direct target of capsaicin to tNOX and this direct binding in melanoma cells influenced the degradation of tNOX and its function as a NADH oxidase to suppress SIRT1 deacetylase, which increased the acetylation of ULK1 to activate autophagy. Similar to our findings, other studies have reported that capsaicin exhibits autophagic activity that coexists or cooperates with apoptosis to enhance cell death [50,51].

Generally, the knockdown approach should highlight the essential role of a protein in the signaling pathway. However, in the scenario of tNOX, it is somehow more complicated for the following reasons. We propose that the anticancer properties of capsaicin are due to its targeting to tNOX, leading to enzymatic activity inhibition and protein degradation. However, tNOX deficiency itself has long being established to be apoptotic and cytotoxic in cancer cells, possibly due to less NAD+ production and greater oxidative stress [20,22,23,52,53]. In this regard, it is not surprising that tNOX deficiency triggers stress-induced apoptosis leading to attenuate growth of cancer cells. In other words, effect of capsaicin targeting to tNOX would be comparable to the effect of tNOX knockdown, although they might exhibit different degree of cytotoxicity. By revealing tNOX as a direct target for capsaicin, we now provide a reasoning to clarify the unequal cytotoxicity of capsaicin in cancer and non-cancerous cells as well shed light on the distinct cellular responses elicited upon exposure to capsaicin.

An array of diverse signaling pathways has been linked to the apoptotic/autophagic activity of capsaicin. Among them, oxidative stress signaling has often being highlighted. Given that ROS are generated mainly through the electron transport chain in mitochondria, many reports have emphasized the correlation between mitochondrial disruption and capsaicin-induced apoptosis in cancer cells [54-57]. Compared to the ROS-dependent apoptotic activity of capsaicin, however, the ability of capsaicin to induce autophagy is relatively less common in the literature. Mostly, capsaicin-mediated has been proposed to promote survival and/or inhibit apoptosis under stressful conditions, regardless of the cancer status of the cells [22,41,58,59]. Very recently, we investigated the interplay between apoptosis and autophagy in capsaicin-treated oral cancer cells with either functional or mutant p53 and found that capsaicin induced significant cytotoxicity via autophagy but not apoptosis in p53-functional oral cancer cells [49]. Similarly, in this present study, we demonstrated that capsaicin triggers cytotoxic autophagy in A375 cells, which bears wild-type p53 gene status. Interestingly, capsaicin treatment of p53-mutated cells triggered both autophagy and apoptosis, with autophagy occurring first. In that case, capsaicin-induced autophagy suppressed apoptosis in the early stage, but thereafter facilitated apoptosis at a later stage, suggesting a complicated crosstalk between these two pathways mediated by capsaicin [49].

Taken together, in this study, we herein used CETSA and CETSA-pulse proteolysis to demonstrate that tNOX directly binds capsaicin to mediate a pathway that leads to cytotoxic autophagy of melanoma cells through enhanced ULK1 acetylation. Our experimental evidence and the data from animal studies collectedly suggest that tNOX can be a promising therapeutic drug target, and that capsaicin could be further developed as an anticancer therapeutic.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant from the Ministry of Sciences and Technology, Taiwan (NSC 102-2320-B-005-008 to PJC).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Abbreviations

- AO

Acridine orange

- CETSA

Cellular thermal shift assay

- ITDRF

Isothermal dose response fingerprint

- NAC

N-acetyl-L-cysteine

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- RNAi

RNA interference

- tNOX or ENOX2

Tumor-associated NADH oxidase

- SIRT1

Sirtuin 1

References

- 1.Gershenwald JE, Guy GP Jr. Stemming the rising incidence of melanoma: calling prevention to action. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108:djv381. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garbe C, Eigentler TK, Keilholz U, Hauschild A, Kirkwood JM. Systematic review of medical treatment in melanoma: current status and future prospects. Oncologist. 2011;16:5–24. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi HB, Hugo W, Kong XJ, Hong A, Koya RC, Moriceau G, Chodon T, Guo RQ, Johnson DB, Dahlman KB, Kelley MC, Kefford RF, Chmielowski B, Glaspy JA, Sosman JA, van Baren N, Long GV, Ribas A, Lo RS. Acquired resistance and clonal evolution in melanoma during BRAF inhibitor therapy. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:80–93. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, Jouary T, Gutzmer R, Millward M, Rutkowski P, Blank CU, Miller WH, Kaempgen E, Martin-Algarra S, Karaszewska B, Mauch C, Chiarion-Sileni V, Mirakhur B, Guckert ME, Swann RS, Haney P, Goodman VL, Chapman PB. An update on BREAK-3, a phase III, randomized trial: dabrafenib (DAB) versus dacarbazine (DTIC) in patients with BRAF V600E-positive mutation metastatic melanoma (MM) J. Clin. Oncol. 2013;31 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Larkin JMG, Haanen JBAG, Ribas A, Hogg D, Hamid O, Ascierto PA, Testori A, Lorigan P, Dummer R, Sosman JA, Garbe C, Maio M, Nolop KB, Nelson BJ, Joe AK, Flaherty KT, McArthur GA. Updated overall survival (OS) results for BRIM-3, a phase III randomized, open-label, multicenter trial comparing BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib (vem) with dacarbazine (DTIC) in previously untreated patients with BRAF (V600E)-mutated melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morre DJ, Chueh PJ, Morre DM. Capsaicin inhibits preferentially the NADH oxidase and growth of transformed cells in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:1831–1835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JD, Kim JM, Pyo JO, Kim SY, Kim BS, Yu R, Han IS. Capsaicin can alter the expression of tumor forming-related genes which might be followed by induction of apoptosis of a Korean stomach cancer cell line, SNU-1. Cancer Lett. 1997;120:235–241. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)00321-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta SC, Kim JH, Prasad S, Aggarwal BB. Regulation of survival, proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis, and metastasis of tumor cells through modulation of inflammatory pathways by nutraceuticals. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29:405–434. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9235-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho SC, Lee H, Choi BY. An updated review on molecular mechanisms underlying the anticancer effects of capsaicin. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2017;26:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10068-017-0001-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chu H, Li M, Wang X. Capsaicin induces apoptosis and autophagy in human melanoma cells. Oncol Lett. 2019;17:4827–4834. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.10206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang SP, Wang DA, Huang JY, Hu YM, Xu YF. Application of capsaicin as a potential new therapeutic drug in human cancers. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2020;45:16–28. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.13039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morre DJ, Sun E, Geilen C, Wu LY, de Cabo R, Krasagakis K, Orfanos CE, Morre DM. Capsaicin inhibits plasma membrane NADH oxidase and growth of human and mouse melanoma lines. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:1995–2003. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(96)00234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel PS, Varney ML, Dave BJ, Singh RK. Regulation of constitutive and induced NF-kappa B activation in malignant melanoma cells by capsaicin modulates interleukin-8 production and cell proliferation. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002;22:427–435. doi: 10.1089/10799900252952217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel PS, Yang S, Li AH, Varney ML, Singh RK. Capsaicin regulates vascular endothelial cell growth factor expression by modulation of hypoxia inducing factor-l alpha in human malignant melanoma cells. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2002;128:461–468. doi: 10.1007/s00432-002-0368-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jun HS, Park T, Lee CK, Kang MK, Park MS, Kang HI, Surh YJ, Kim OH. Capsaicin induced apoptosis of B16-F10 melanoma cells through down-regulation of Bcl-2. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45:708–715. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shin DH, Kim OH, Jun HS, Kang MK. Inhibitory effect of capsaicin on B16-F10 melanoma cell migration via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/Rac1 signal pathway. Exp Mol Med. 2008;40:486–494. doi: 10.3858/emm.2008.40.5.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pal HC, Hunt KM, Diamond A, Elmets CA, Afaq F. Phytochemicals for the management of melanoma. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2016;16:953–979. doi: 10.2174/1389557516666160211120157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morré DJ. NADH oxidase: a multifunctional ectoprotein of the eukaryotic cell surface. In: Asard H, Bérczi A, Caubergs R, editors. Plasma membrane redox systems and their role in biological stress and disease. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998. pp. 121–1561. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang HM, Chueh PJ, Chang SP, Yang CL, Shao KN. Effect of Ccapsaicin on tNOX (ENOX2) protein expression in stomach cancer cells. Biofactors. 2008;34:209–217. doi: 10.3233/BIO-2009-1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang HM, Chuang SM, Su YC, Li YH, Chueh PJ. Down-regulation of tumor-associated NADH oxidase, tNOX (ENOX2), enhances capsaicin-induced inhibition of gastric cancer cell growth. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2011;61:355–366. doi: 10.1007/s12013-011-9218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu NC, Hsieh PF, Hsieh MK, Zeng ZM, Cheng HL, Liao JW, Chueh PJ. Capsaicin-mediated tNOX (ENOX2) up-regulation enhances cell proliferation and migration in vitro and in vivo. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:2758–2765. doi: 10.1021/jf204869w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee YH, Chen HY, Su LJ, Chueh PJ. Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) deacetylase activity and NAD(+)/NADH ratio are imperative for capsaicin-mediated programmed cell death. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63:7361–7370. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b02876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin MH, Lee YH, Cheng HL, Chen HY, Jhuang FH, Chueh PJ. Capsaicin inhibits multiple bladder cancer cell phenotypes by inhibiting tumor-associated NADH oxidase (tNOX) and sirtuin1 (SIRT1) Molecules. 2016;21:849. doi: 10.3390/molecules21070849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Islam A, Su AJ, Zeng ZM, Chueh PJ, Lin MH. Capsaicin targets tNOX (ENOX2) to inhibit G1 cyclin/CDK complex, as assessed by the cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA) Cells. 2019;8:1275. doi: 10.3390/cells8101275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dziekan JM, Wirjanata G, Dai L, Go KD, Yu H, Lim YT, Chen L, Wang LC, Puspita B, Prabhu N, Sobota RM, Nordlund P, Bozdech Z. Cellular thermal shift assay for the identification of drug-target interactions in the Plasmodium falciparum proteome. Nat Protoc. 2020;15:1881–1921. doi: 10.1038/s41596-020-0310-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez Molina D, Jafari R, Ignatushchenko M, Seki T, Larsson EA, Dan C, Sreekumar L, Cao Y, Nordlund P. Monitoring drug target engagement in cells and tissues using the cellular thermal shift assay. Science. 2013;341:84–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1233606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez Molina D, Nordlund P. The cellular thermal shift assay: a novel biophysical assay for in situ drug target engagement and mechanistic biomarker studies. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016;56:141–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010715-103715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simon GM, Niphakis MJ, Cravatt BF. Determining target engagement in living systems. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:200–205. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lim YT, Prabhu N, Dai L, Go KD, Chen D, Sreekumar L, Egeblad L, Eriksson S, Chen L, Veerappan S, Teo HL, Tan CSH, Lengqvist J, Larsson A, Sobota RM, Nordlund P. An efficient proteome-wide strategy for discovery and characterization of cellular nucleotide-protein interactions. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0208273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prabhu N, Dai L, Nordlund P. CETSA in integrated proteomics studies of cellular processes. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2020;54:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2019.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park CW, Marqusee S. Pulse proteolysis: a simple method for quantitative determination of protein stability and ligand binding. Nat Methods. 2005;2:207–212. doi: 10.1038/nmeth740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park C, Marqusee S. Quantitative determination of protein stability and ligand binding by pulse proteolysis. Curr Protoc Protein Sci. 2006 doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps2011s46. Chapter 20: Unit 20.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen CF, Huang S, Liu SC, Chueh PJ. Effect of polyclonal antisera to recombinant tNOX protein on the growth of transformed cells. Biofactors. 2006;28:119–133. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520280206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang JT. An economic and efficient method of RNAi vector constructions. Anal Biochem. 2004;334:199–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu D, Wu J, Xu LF, Zhang RB, Chen LP. A method for the establishment of a cell line with stable expression of the GFP-LC3 reporter protein. Mol Med Rep. 2012;6:783–786. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu SC, Yang JJ, Shao KN, Chueh PJ. RNA interference targeting tNOX attenuates cell migration via a mechanism that involves membrane association of Rac. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;365:672–677. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ke N, Wang X, Xu X, Abassi YA. The xCELLigence system for real-time and label-free monitoring of cell viability. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;740:33–43. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-108-6_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moela P, Choene MM, Motadi LR. Silencing RBBP6 (Retinoblastoma Binding Protein 6) sensitises breast cancer cells MCF7 to staurosporine and camptothecin-induced cell death. Immunobiology. 2014;219:593–601. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meijer AJ, Codogno P. Autophagy: regulation and role in disease. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2009;46:210–240. doi: 10.1080/10408360903044068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marino ML, Pellegrini P, Di Lernia G, Djavaheri-Mergny M, Brnjic S, Zhang XN, Hagg M, Linder S, Fais S, Codogno P, De Milito A. Autophagy is a protective mechanism for human melanoma cells under acidic stress. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:30664–30676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.339127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen X, Tan M, Xie Z, Feng B, Zhao Z, Yang K, Hu C, Liao N, Wang T, Chen D, Xie F, Tang C. Inhibiting ROS-STAT3-dependent autophagy enhanced capsaicin-induced apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Free Radic Res. 2016;50:744–755. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2016.1173689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bu HQ, Cai K, Shen F, Bao XD, Xu Y, Yu F, Pan HQ, Chen CH, Du ZJ, Cui JH. Induction of apoptosis by capsaicin in hepatocellular cancer cell line SMMC-7721 is mediated through ROS generation and activation of JNK and p38 MAPK pathways. Neoplasma. 2015;62:582–591. doi: 10.4149/neo_2015_070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qian K, Wang G, Cao R, Liu T, Qian G, Guan X, Guo Z, Xiao Y, Wang X. Capsaicin suppresses cell proliferation, induces cell cycle arrest and ROS production in bladder cancer cells through FOXO3a-mediated pathways. Molecules. 2016;21:1406. doi: 10.3390/molecules21101406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen HY, Lee YH, Chen HY, Yeh CA, Chueh PJ, Lin YM. Capsaicin inhibited aggressive phenotypes through downregulation of tumor-associated NADH oxidase (tNOX) by POU domain transcription factor POU3F2. Molecules. 2016;21:733. doi: 10.3390/molecules21060733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kalra EK. Nutraceutical-definition and introduction. AAPS PharmSci. 2003;5:E25. doi: 10.1208/ps050325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hardy G. Nutraceuticals and functional foods: introduction and meaning. Nutrition. 2000;16:688–689. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(00)00332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pereira GJV, Tavares MT, Azevedo RA, Martins BB, Cunha MR, Bhardwaj R, Cury Y, Zambelli VO, Barbosa EG, Hediger MA, Parise R. Capsaicin-like analogue induced selective apoptosis in A2058 melanoma cells: design, synthesis and molecular modeling. Bioorg Med Chem. 2019;27:2893–2904. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2019.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwartz L, Guais A, Israel M, Junod B, Steyaert JM, Crespi E, Baronzio G, Abolhassani M. Tumor regression with a combination of drugs interfering with the tumor metabolism: efficacy of hydroxycitrate, lipoic acid and capsaicin. Invest New Drugs. 2013;31:256–264. doi: 10.1007/s10637-012-9849-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chang CF, Islam A, Liu PF, Zhan JH, Chueh PJ. Capsaicin acts through tNOX (ENOX2) to induce autophagic apoptosis in p53-mutated HSC-3 cells but autophagy in p53-functional SAS oral cancer cells. Am J Cancer Res. 2020;10:3230–3247. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin YT, Wang HC, Hsu YC, Cho CL, Yang MY, Chien CY. Capsaicin induces autophagy and apoptosis in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells by downregulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1343. doi: 10.3390/ijms18071343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Y, Deng X, Yu C, Zhao G, Zhou J, Zhang G, Li M, Jiang D, Quan Z, Zhang Y. Synergistic inhibitory effects of capsaicin combined with cisplatin on human osteosarcoma in culture and in xenografts. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:251. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0922-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen HY, Islam A, Yuan TM, Chen SW, Liu PF, Chueh PJ. Regulation of tNOX expression through the ROS-p53-POU3F2 axis contributes to cellular responses against oxaliplatin in human colon cancer cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:161. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0837-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen HY, Cheng HL, Lee YH, Yuan TM, Chen SW, Lin YY, Chueh PJ. Tumor-associated NADH oxidase (tNOX)-NAD+-sirtuin 1 axis contributes to oxaliplatin-induced apoptosis of gastric cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:15338–15348. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu SC, Cheng X, Wu LY, Zheng JX, Wang XW, Wu J, Yu HX, Bao JD, Zhang L. Capsaicin induces mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma cells via TRPV1-mediated mitochondrial calcium overload. Cell Signal. 2020;75:109733. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2020.109733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xie L, Xiang GH, Tang T, Tang Y, Zhao LY, Liu D, Zhang YR, Tang JT, Zhou S, Wu DH. Capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin induce apoptosis in human glioma cells via ROS and Ca2+-mediated mitochondrial pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14:4198–4208. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pramanik KC, Boreddy SR, Srivastava SK. Role of mitochondrial electron transport chain complexes in capsaicin mediated oxidative stress leading to apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang ZH, Wang XH, Wang HP, Hu LQ, Zheng XM, Li SW. Capsaicin mediates cell death in bladder cancer T24 cells through reactive oxygen species production and mitochondrial depolarization. Urology. 2010;75:735–741. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oh SH, Lim SC. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated autophagy/apoptosis induced by capsaicin (8-methyl-N-vanillyl-6-nonenamide) and dihydrocapsaicin is regulated by the extent of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation in WI38 lung epithelial fibroblast cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:112–122. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.144113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ramos-Torres A, Bort A, Morell C, Rodriguez-Henche N, Diaz-Laviada I. The pepper’s natural ingredient capsaicin induces autophagy blockage in prostate cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7:1569–1583. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]