Abstract

Purpose

The Covid-19 pandemic has significantly burdened healthcare systems worldwide and substantially affected the psychological state. The objective of this narrative review was to summarize the psychological outcome of the “Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic” on healthcare workers in kingdom of Saudi Arabia to assess their mental health outcome that can aid in development of guidelines and psychological interventions that can improve healthcare workers' quality of life, work and decision-making capability toward patient treatment during the pandemic.

Materials and Methods

A comprehensive research was done to overview current available literature on psychological and mental health issues observed among healthcare workers “HCW” in Saudi Arabia. The search included all articles published since the beginning of the pandemic from January 2020 till February 2021 relevant to the subject of the review. In this review, a total of 10 primary research articles were included following a cross-sectional survey method to analyze the impact of various psychological variables.

Results

Anxiety symptoms were reported by between 33.3% and 68.5% of HCWs. Between 27.9% and 55.2% of HCWs reported depressive symptoms. HCWs reported anxiety, depression, sleep disturbances and distress with a range comprised between 27.9% and 68.5%.

Conclusion

The Covid-19 pandemic has certainly led to multifaceted and vigorous psychological and mental impact on healthcare providers, it is now both an opportunity and challenge to design further studies that can lead to development of guidelines in Saudi Arabia and worldwide to improve mental health infrastructure that strengthen patient oriented treatment of care plan during this pandemic.

Keywords: anxiety, depression, stress, insomnia

Introduction

In the year 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the coronavirus outbreak as a global emergency. A year has been passed to this pandemic and the prevalence of psychological issues is rising day by day as the pandemic progresses. It has come across as an unprecedented dispute for healthcare systems. Generally, pandemics require immediate and efficient response from healthcare systems, with many healthcare workers (HCWs), either involved directly such as doctors and nurses or indirectly like laboratory and radiology technicians providing patients with care, fighting at the frontline and addressing challenges that threaten healthcare systems.1

History has showed that dynamic stress is experienced by HCWs during outbreaks. In a Chinese study among HCWs during the Ebola outbreak, extreme anxiety, depression, somatization and obsession-compulsions were reported.2 Also, in a study in Saudi Arabia, almost two thirds of HCWs reported feeling at risk of getting Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection and felt unsafe working during the MERS outbreak.3

In Saudi Arabia, since the beginning of the pandemic until the 1st of December, 2020, there were 347,157 confirmed (Covid-19) cases, with 5907 deaths.4 Until this date, there is no cure or approved vaccine for Covid-19. On top of that, an increase in depression, stress and anxiety symptoms has been reported in the general population and, especially, in HCWs. Increased working duties and the need to make difficult decisions on prioritizing care of patients may have strong effects on HCWs’ physical and mental health. Their resilience can be further affected by isolation and loss of social support, risk of infections or infecting family and friends as well as desperate, often unsettling changes in their work responsibilities.5

Thus, HCWs especially frontline staff face critical conditions which increase their risk of disturbing their mental health after dealing with unfavorable situations that can range from psychological distress to psychological symptoms more than the general population.6,7 Fighting against a new virus with an unknown nature for a prolonged time is a crisis that affects the sustainability of healthcare systems. Maintaining the maximum possible care provided fully relies on protecting the health of those responding to such crisis. Yet, the published findings of psychological distress among HCWs might indicate that healthcare systems are currently unable to effectively protect the helpers.8

Psychological impacts and fear or hesitancy in HCWs may affect the efficiency, and quality of work as well as willingness to report to work which can have a dramatic effect on healthcare systems especially during pandemics.9 Reported physicians committing suicide with the psychological impacts reported worldwide, led me to review the current literature of this pandemic on HCWs in Saudi Arabia and the latest recommendation regarding their mental health.10,11

The objective of this narrative review is to summarize the psychological outcome of the “Coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic” on healthcare workers in kingdom of Saudi Arabia to assess their mental health outcome that can aid in development of guidelines and psychological interventions that can improve healthcare workers' quality of life, work and decision-making capability toward patient treatment during pandemic.

Materials and Methods

A comprehensive research was done to overview current available primary literature on psychological and mental health issues observed among healthcare workers “HCW” in Saudi Arabia. Literature search was conducted in “PubMed (MEDLINE)”, “ProQuest” and “Web of Science” database. Data were retrieved using the following search terms (“medical staff” OR “healthcare” OR “healthcare professionals” OR “Physicians”) AND (“coronavirus” OR “COVID-19”) AND (“anxiety” OR “depression” OR “insomnia” OR “psychological” OR “mental health” OR “Stress”) AND (in “Saudi Arabia” OR “KSA”) in our search engines.

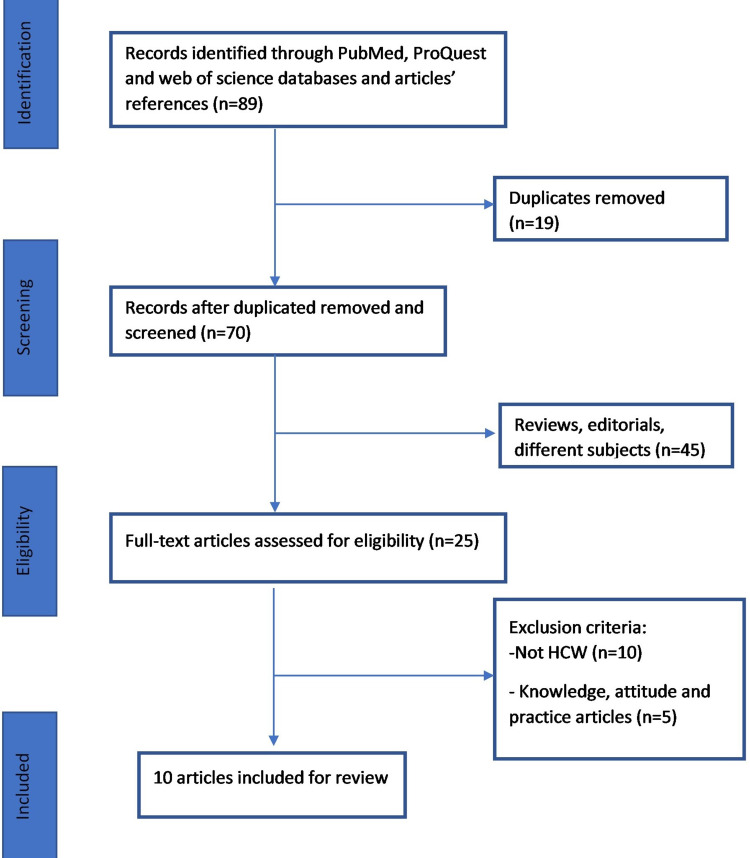

Our search included all primary articles published in peer reviewed journals since the beginning of pandemic from January 2020 till February 2021 relevant to the subject of the review catering original research. Review articles, correspondence, case reports and non-English articles were excluded. A final total of 89 citations were identified through search terms collectively from all databases. During initial screening 19 citations were removed as duplicate. Out of 70 after removing duplicate articles, 45 articles including review articles, correspondence and case reports were removed. Out of 25, a further 15 articles were removed as they were not conducted on HCW and assessed knowledge, attitude and practices. A total of final 10 full texts, primary articles were included. Results of the potential 10 articles were summarized in the form of Table 1 and health variables including anxiety, stress, sleep and depression are assessed in all studies (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Description of Study Methodology, Number of HCWs, Anxiety, Stress, Sleep, Depression Variables and Assessment Tools Used in Selected Studies

| Study No | Author | Year | Methodology | Total No of Saudi HCW | Anxiety | Stress | Sleep | Depression | Assessment Tools Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Arafa et al12 | 2021 | Cross sectional survey | 151 | 58.90% | 55.90% | 37.30% | 69% | Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) |

| 2 | Almater et al13 | 2020 | Online survey | 107 | 46.70% | Low 28%, moderate 68.2%, High 3.7% | 44.90% | 50.50% | Nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7), seven-item Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) |

| 3 | AlAteeq et al14 | 2020 | Cross sectional survey | 502 | 51.40% | 55.20% | Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) | ||

| 4 | Alenazi et al16 | 2020 | Online survey | 4920 | 68.50% | Likert scale | |||

| 5 | Alzaid et al22 | 2020 | Cross sectional survey | 441 | 33.30% | Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) | |||

| 6 | Al-Hanawi et al17 | 2020 | Cross sectional survey | 950 | 40.00% | Five scaled responses to construct a CPDI | |||

| 7 | Alqutub et al18 | 2021 | Cross sectional survey | 2094 | 27.60% | 27.60% | The Kessler psychological distress scale (k10) | ||

| 8 | Al Sulais et al19 | 2020 | Cross sectional survey | 529 | Worry 67.5%, Isolation 56.9%, fear 49.7% | Likert scale | |||

| 9 | Al Ammari et al20 | 2020 | Cross sectional survey | 1130 | 78.88% | 85.83% | 76.93% | 9-item patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9), the 7-item generalized anxiety disorder scale (GAD-7), and 7-item insomnia severity index (ISI) | |

| 10 | Ajwa et al15 | 2020 | Cross sectional survey | 577 | 14% | 7% | General Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) and Patient’s Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) |

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus; SARS, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome; HCWs, healthcare workers; MERS-CoV, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus; WHO, World Health Organization; GAD-7, General Anxiety Disorder; PHQ-9, Patient’s Health Questionnaire; DASS-21, Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21; PDI, Peritraumatic Distress Index.

Figure 1.

Eligibility criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies in the review.

Results

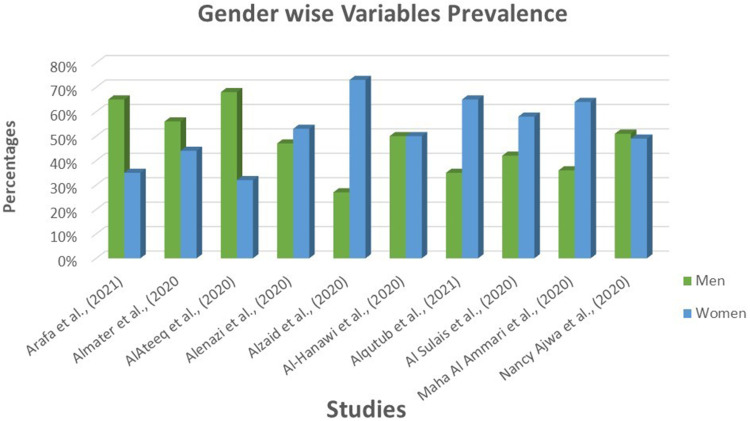

In this review, a total of 10 citations were included following a cross-sectional survey method to analyze the impact of various psychological variables including anxiety, stress, sleep and depression among Saudi healthcare workers during the Covid-19 pandemic. All 10 studies were evaluated to assess psychological symptom prevalence in both males and females. The psychological symptom prevalence was profoundly observed in females (6 studies) in comparison to males (4 studies) (Figure 2). The most frequently used assessment tools were General Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) and Patient’s Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) respectively. However, other tools including Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) and the psychological distress using the COVID-19 Peritraumatic Distress Index (CPDI) were also used.

Figure 2.

Gender-wise psychological variable prevalence.

In this study, Arafa et al12 reported highest progression of depression symptoms 69% in comparison to anxiety 58.90%, stress 55.9% and inadequate sleep 37.3% respectively among healthcare providers. He further graded depression as 29.6% with severe depressive symptoms and 39.4% with mild to moderate depression. Another study by Almater et al13 had further explained grading of stress among healthcare practitioners with stress low levels (28%), moderate levels (68.2%) and high levels (3.7%).

Two studies by AlAteeq et al14 and Nancy Ajwa et al15 explained both anxiety and depression among healthcare professionals and observed more depressive and anxious symptoms were observed in professionals deputed in medical wards as compared to dental ward. The largest study was done in a nation-level cross-sectional study of participants from all the 13 administrative regions in Saudi Arabia with a sample of 4920 HCWs. They divided them into three groups according to anxiety level on the Dispositional cancer worry scale, 1552 (31.5%) low, 1778 (36.1%) medium, and 1590 (32.3%) high anxiety.16

In Al-Hanawi et al17 the study sample was 950 and (28.9%) showed normal, (33.7%) mild and (39.9%) severe distress using the COVID-19 Peritraumatic Distress Index which is a self-reported questionnaire that was originally used by a study in China to assess peritraumatic psychological distress during the pandemic. Another study by Alqutub et al18 used the Kessler psychological distress scale (k10) question, and found that 27.6% healthcare workers were in psychological distress.

Al Sulais et al19 used a questionnaire designed by Reynolds et al and observed that the most common feelings reported by the physicians during the pandemic were: worry (67.5%), isolation (56.9%) and fear (49.7%) through using a Likert scale. Similarly, Al Ammari et al20 with participation of 1130 participants from the healthcare sector showed 78.88% symptoms of work induced psychological anxiety, 85.83% disturbance in sleep cycle or inability to sleep properly which ultimately led to 76.93% symptoms of depression.

Discussion

This review provided the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers in Saudi Arabia. Overall, 60% of the studies reviewed in this article found out that more than 50% of the healthcare workers had psychological impact in terms of depression, anxiety and stress during the global emergency.

The studies included in our review reflected females as predominant participants in 6 studies (64.40–72.80%). Similarly, Lai et al7 in their study reflected professional women showed moderate to severe depression, anxiety and stress. Arafa et al12 in their study stated that mostly allied healthcare providers missed family emotional support and indulged in watching covid news that increased likelihood of stress, disturbed sleep, anxiety and depression among patients. In correlation to it, to improve overall HCW mental health status, Banerjee21 emphasized on psychiatrist significance in terms of education on pandemic psychological impact on public, motivation to develop and adopt strategies to prevent the spread of novel virus through basic practices and its integration in available healthcare setups. It also suggested how to adopt a problem solving approach and empowering both caregivers and patients through provision of quality mental healthcare services to care providers.

In a study conducted in China, prevalence distress symptoms were highest (71.5%), followed by depression (50.4%), anxiety (44.6%) and insomnia (34.0%) respectively.7 Overall, our studies have showed more prevalence of depression and anxiety in comparison to stress and insomnia symptoms. In another study by Almater et al13 impact of Covid-19 was observed in ophthalmologist setup. During earlier pandemics healthcare professionals felt unprotected and lethargic, stressed during working in high-risk areas, however no significant previous work was identified regarding safety and psychological counseling of ophthalmologists during exposure with patients during work. Ophthalmologists are also at higher risk of virus transmission because of increased exposure to droplet or contact routes while performing slit lamp examination.

Longitudinal research studies are important to follow up on HCWs' mental health and develop intervention strategies that are evidence-based. Routine mental health screening is encouraged especially during pandemics.16,17,22 The World Health Organization’s mental health department published strategies to decrease the negative psychological impact of the COVID‑19 pandemic to the general population and HCWs. A well-balanced lifestyle including regular exercise, healthy diet and enough sleep is advised. Staying connected with families and friends is also encouraged with the different virtual applications.23

This study provided the review of merely 10 original articles as limited primary data were available relevant to our objective. We could not apply the quality assessment tool in this review yet we performed a detailed assessment of every included article. Regarding the type of the study, as this pandemic was started in 2020 and a short time span has passed, primary data were scarce and most of the studies were cross sectional and none of the longitudinal studies could be reviewed. The response variability might occur as studies were conducted in different medical institutes and different stress, anxiety and depression scales were used.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has certainly led multifaceted and vigorous psychological and mental impact on healthcare providers, it is now both an opportunity and challenge to design further studies that can lead to development of guidelines in Saudi Arabia and worldwide to improve mental health infrastructure that strengthen patient oriented treatment of care plan during this pandemic through development of mental health interventions that can overall improve productivity of healthcare provider.

Acknowledgments

The author is thankful to all the associated personnel, who contributed to this study by any means.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Preti E, Di Mattei V, Perego G, et al. The psychological impact of epidemic and pandemic outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review of the evidence. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22:1–22. doi: 10.1007/s11920-020-01166-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ji D, Ji YJ, Duan XZ, et al. Prevalence of psychological symptoms among Ebola survivors and healthcare workers during the 2014–2015 Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone: a cross-sectional study. Oncotarget. 2017;8:12784. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abolfotouh MA, AlQarni AA, Al-Ghamdi SM, Salam M, Al-Assiri MH, Balkhy HH. An assessment of the level of concern among hospital-based health-care workers regarding MERS outbreaks in Saudi Arabia. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:1. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-2096-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saudi Ministry of Health; 2020. Available from: https://covid19.moh.gov.sa/. Accessed December1, 2020.

- 5.Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou Y, Wang W, Sun Y, et al. The prevalence and risk factors of psychological disturbances of frontline medical staff in China under the COVID-19 epidemic: workload should be concerned. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:510–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muller RA, Stensland RS, van de Velde RS. The mental health impact of the covid-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, and interventions to help them: a rapid systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113441. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Almaghrabi RH, Huda A, Al HW, Albaadani MM. Healthcare workers experience in dealing with Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Saudi Med J. 2020;41:657–660. doi: 10.15537/smj.2020.6.25101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NBC New York. NYC emergency room doctor dies by suicide after treating COVID-19 patients; 2020. Available from: https://www.nbcnewyork.com/news/coronavirus/nyc-emergency-room-doctordies-from-suicide-after-treating-covid-19-patients/2391978/. Accessed December1, 2020.

- 11.NST Online. French doctor commits suicide after Covid-19 diagnosis. New Straits Times; 2020. Available from: https://www.nst.com.my/world/world/2020/04/581620/french-doctor-commits-suicide-after-covid-19-diagnosis. Accessed December1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arafa A, Mohammed Z, Mahmoud O, Elshazley M, Ewis A. Depressed, anxious, and stressed: what have healthcare workers on the frontlines in Egypt and Saudi Arabia experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic? J Affect Disord. 2021;278:365–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Almater AI, Tobaigy MF, Younis AS, Alaqeel MK, Abouammoh MA. Effect of 2019 coronavirus pandemic on ophthalmologists practicing in Saudi Arabia: a psychological health assessment. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2020;27:79. doi: 10.4103/meajo.meajo_220_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.AlAteeq DA, Aljhani S, Althiyabi I, Majzoub S. Mental health among healthcare providers during coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13:1432–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ajwa N, Al Rafee A, Al Rafie H, et al. Psychological status assessment of medical and dental staff during the covid-19 outbreak in Saudi Arabia. Med Sci. 2020;24:4790–4797. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alenazi TH, BinDhim NF, Alenazi MH, et al. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety among healthcare workers in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13:1645–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Hanawi MK, Mwale ML, Alshareef N, et al. Psychological distress amongst health workers and the general public during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2020;13:733. doi: 10.2147/rmhp.s264037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alqutub S, Mahmoud M, Baksh T. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on frontline healthcare workers in Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2021;13(5):e15300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al Sulais E, Mosli M, AlAmeel T. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on physicians in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:249. doi: 10.4103/sjg.sjg_174_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al Ammari M, Sultana K, Thomas A, Al Swaidan L, Al Harthi N. Mental health outcomes amongst health care workers during COVID 19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.619540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banerjee D. The COVID-19 outbreak: crucial role the psychiatrists can play. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;50:102014. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alzaid EH, Alsaad SS, Alshakhis N, Albagshi D, Albesher R, Aloqaili M. Prevalence of COVID-19-related anxiety among healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2020;9:4904. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_674_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Who.int; 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations. Accessed December1, 2020.