Abstract

Objective

This is the fifth article in a series that explores the historical events surrounding the Wilk v American Medical Association (AMA) lawsuit in which the plaintiffs argued that the AMA, the American Hospital Association, and other medical specialty societies violated antitrust law by restraining chiropractors' business practices. The purpose of this article is to provide a brief review of events surrounding the eventual end of the AMA's Committee on Quackery and the exposure of evidence of the AMA's efforts to boycott the chiropractic profession.

Methods

This historical research study used a phenomenological approach to qualitative inquiry into the conflict between regular medicine and chiropractic and the events before, during, and after a legal dispute at the time of modernization of the chiropractic profession. Our methods included obtaining primary and secondary data sources. The final narrative recount was developed into 8 articles following a successive timeline. This article, the fifth of the series, explores the exposure of what the AMA had been doing, which provided evidence that was eventually used in the Wilk v AMA antitrust lawsuit.

Results

The prime mission of the AMA's Committee on Quackery was “first, the containment of chiropractic and, ultimately, the elimination of chiropractic.” However, the committee did not complete its mission and quietly disbanded in 1974. This was the same year that the chiropractic profession finally gained licensure in all 50 of the United States; received recognition from the US Commissioner of Education, Department of Health, Education and Welfare; and was successfully included in Medicare. In 1975, documents reportedly obtained by the Church of Scientology covert operatives under Operation AMA Doom revealed the extent to which the AMA and its Committee on Quackery had been working to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession. The AMA actions included influencing mainstream media, decisions made by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals, and the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Other actions included publishing propaganda against chiropractic and implementing an anti-chiropractic program aimed at medical students, medical societies, and the American public.

Conclusion

After more than a decade of overt and covert actions, the AMA chose to end its Committee on Quackery. The following year, documents exposed the extent of AMA's efforts to enact its boycott of chiropractic.

Keywords: Health Occupations; Chiropractic; Medicine; Humanities; History, 20th Century; Antitrust Laws

INTRODUCTION

The Wilk v American Medical Association (AMA) lawsuit1 almost did not take place. For a lawsuit to be successful, substantive evidence is required. However, before 1975, there was not much evidence that would verify the depths of what were suspected to be the AMA's clandestine efforts to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession.

Beginning in the early 1900s, the AMA had fought to suppress chiropractic licensure and professional recognition. However, as chiropractic grew and chiropractors became more outspoken in the 1950s, the efforts to contain chiropractic increased. By 1963, the AMA established a Committee on Quackery (CoQ) that organized activities against chiropractic. In a 1963 correspondence to Mr. Throckmorton (AMA legal counsel), the message stated, “It would seem from certain declarations of the House of Delegates and the Judicial Council, that the ultimate objective of the AMA theoretically, is the complete elimination of the chiropractic ‘profession.'”2

The AMA's plan focused on disrupting the key components of the chiropractic profession. The AMA CoQ encouraged chiropractic disunity by attempting to keep the 2 national associations from joining and creating a unified front. The AMA undertook a program of containment by preventing chiropractic growth and licensure. They encouraged ethical complaints against doctors of chiropractic by other health professionals. They opposed chiropractic inroads in health insurance, workman's compensation, labor unions, and hospitals, thereby limiting chiropractors' ability to be reimbursed. They aimed to undermine chiropractic schools to prevent improvement in education and research, in an attempt to cripple the profession.2–4

These actions were well known by chiropractors and the 2 chiropractic associations; however, they did not have enough evidence to prove these illegal activities. What they needed was evidence to fight against these attacks in the legal arena. But in 1974, the CoQ was disbanded. Thus, it seemed unlikely that any new evidence would be discovered.

However, unknown to the chiropractic profession at the time, another group was collecting information that would be necessary, not only to file an antitrust lawsuit, but bring such a lawsuit to a successful conclusion. The AMA information that was eventually exposed from this unlikely source would be used as evidence during the trial to reveal the AMA's persistent and clandestine efforts.5

The historical events surrounding this lawsuit are important for chiropractors today, because they help explain the surge in scientific growth6–25 and the improvement in access to chiropractic care for patients once barriers were removed.26–39 These events clarify chiropractic's previous struggles and how past experiences can influence current events. The obstacles and challenges that chiropractic overcame may help explain the current culture and help to identify issues that the chiropractic profession may need to address into the future.

The purpose of this article is to provide a brief review of events surrounding the eventual end of the AMA's CoQ and the exposed evidence of the AMA boycott against the chiropractic profession. This article describes the exposure of what the AMA had been doing clandestinely in the prior decades, which provided evidence that was eventually used in the Wilk v AMA antitrust lawsuit.

METHODS

This historical study used a phenomenological approach to qualitative inquiry into the conflict between regular (orthodox) medicine and chiropractic and the events before, during, and after a legal dispute at the time of modernization of the chiropractic profession. The meta-theoretical assumption that guided our research was a neohumanistic paradigm. As described by Hirschheim and Klein, “The neohumanist paradigm seeks radical change, emancipation, and potentiality, and stresses the role that different social and organizational forces play in understanding change. It focuses on all forms of barriers to emancipation-in particular, ideology (distorted communication), power, and psychological compulsions and social constraints-and seeks ways to overcome them.”40 We used a pragmatic and postmodernist approach to guide our research practices, such that objective reality may be grounded in historical context and personal experiences and interpretation may evolve with changing perspectives.41

We followed techniques described by Lune and Berg.42 These steps included identifying the topic area, conducting a background literature review, and refining the research idea. Following this, we identified data sources and evaluated the source materials for accuracy. Our methods included obtaining primary data sources: written testimony, oral interviews, public records, legal documents, minutes of meetings, newspapers, letters, and other artifacts. Information was obtained from publicly available collections on the internet, university archives, and privately owned collections. Secondary sources included scholarly materials from textbooks and journal articles. The materials were reviewed, and then we developed a narrative recount of our findings.

The article was reviewed for accuracy, completeness, and content validity by a diverse panel of experts, which included reviewers from various perspectives within the chiropractic profession ranging from broad-scope (mixer) to narrow-scope (straight) viewpoints, chiropractic historians, faculty and administrators from chiropractic degree programs, corporate leaders, participants who delivered testimony in the trials, and laypeople who are chiropractic patients. The article was revised based on the reviewers' feedback and returned for additional rounds of review. The final narrative recount was developed into 8 articles that follow a chronological storyline.3,43–48 This article is the fifth of the series that considered events relating to the lawsuit and discusses the end of the American Medical Association's (AMA's) Committee on Quackery (CoQ) and exposure of evidence showing there was a concerted effort to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession.

RESULTS

AMA's Longstanding Fight for Control of American Health Care

Starting in 1847, the AMA forbade its members (ie, “regular” medical doctors) from collaborating with “irregular” medical practitioners.48 The earliest of AMA documents forbade providers who were not regular medical doctors: “no preceptor shall be received who is avowedly and notoriously an irregular practitioner, whether he shall possess the degree of M.D. or not.”48 Not only was AMA membership forbidden to any providers whom the AMA did not endorse, but collaboration was forbidden as well.

After chiropractic began in 1895, the AMA clearly stated that chiropractors were not welcomed by organized medicine. The 1923 AMA Bulletin stated, “There are those who believe and who insist that the medical profession, through its societies, as individuals, and in all possible ways consistent with honor, should fight chiropractors and other cultists and seek to prevent them from practicing their methods and devices.”49

During its growth, the AMA was successful in eliminating or absorbing competing professions. For example, the AMA labeled osteopathy a cult since it began in the 1870s. However, by the 1950s, because of various pressures by organized medicine, osteopathy had adopted many of the practices of medicine, including the use of drugs and surgery. Because of these changes in the osteopathic profession, the AMA encouraged osteopaths to become AMA members.50 Organized medicine continued to work to absorb osteopathy, and eventually, it no longer competed as an alternative health system.51 With osteopathy no longer posing a substantial threat and having been nearly absorbed or annexed into regular medicine, chiropractic was one of the last remaining substantial professions in the 1950s.

Originating from the Iowa State Medical Society's Chiropractic Committee in the 1950s,3 the AMA's CoQ began in the early 1960s, and its purpose was to be “involved almost exclusively with the chiropractic problem.”2 As stated by one of its members, the CoQ's “goal was to contain and hopefully eventually eliminate chiropractic as a licensed health discipline.”52

Despite the AMA's rule that made working collaboratively with chiropractors unethical, there were some medical doctors who supported interprofessional relationships. For example, in 1971, an author in the New England Journal of Medicine suggested that organized medicine's recent recognition of the value of optometry, podiatry, and osteopathy posed an opportune time to consider doing the same for chiropractic. The author challenged medical beliefs by stating, “For too long, organized medicine has been fruitlessly attempting to eliminate chiropractors through charges of charlatanism. Instead, it would seem to be in the best interests of the public and in the best scientific traditions of our profession for medicine to involve chiropractic in a dispassionate evaluation of that profession.”53 He went on to criticize the Health, Education and Welfare report for not including chiropractors on the investigation teams. The article concluded by saying that if medicine and chiropractic could come to an agreement on a place that chiropractic might fit into the established health care system, “that will be maximally beneficial to patients.”53

Suggestions that medical doctors should collaborate with chiropractors or that the medical and chiropractic professions should begin a dialog was met with fierce criticism from within organized medicine. Dr Joseph Sabatier Jr, a leader of the AMA's CoQ, criticized chiropractic for not having “one shred of objective evidence” and for not being accredited by an agency recognized by the US Office of Education. However, one of the reasons that chiropractic programs were not accredited was because the AMA fought to prevent the changes necessary for accreditation. And, although chiropractors had begun to generate small amounts of research and tried to establish relationships with research universities, these efforts were blocked on multiple occasions by the policy of the AMA to prevent the accreditation of chiropractic programs.3,43,44,48 Therefore, the CoQ implemented plans that prevented chiropractors from improving in education and research, and at the same time, the AMA criticized chiropractic for the lack of improvement in these areas.

During the early 1970s, the AMA, which was the largest and most powerful health care organization in America, was slowly going broke.54 The AMA was facing financial crisis, reportedly having lost $3.5 million in 1974 and had a $2.6 million deficit in 1975.55 It had lost $8.5 million between 1970 and 1975, reportedly because the organization failed “to raise dues and keep its expenses under control.”56 The AMA leaders were concerned about controlling costs. Additional lawsuits would contribute to their continuing financial drain.

With malpractice issues, membership decreasing, and other financial strains, the AMA had to cut back operations, which included the CoQ.57 To contain costs, the AMA closed field offices and dismissed staff.56 The CoQ was disbanded in 1974, and the AMA Department of Investigation ended the following year in 1975.

Even though the AMA terminated the CoQ, their efforts had been building for many years. Their propaganda was embedded not only in policies and legislation throughout the nation but also in the psyche of medical physicians and the American public. These effects would be long lasting.

Chiropractic in the 1970s

The political push for chiropractic scope of practice between the 2 national US chiropractic associations was often in different directions; however, the core concepts of chiropractic were generally agreed upon. In 1966, educational leaders with diverse views ranging from straight/narrow scope to mixer/broad scope joined together to create a white paper that described chiropractic. They jointly published the statement in 1973 to help clarify what chiropractic was at that time (Fig. 1).58 The document included the following:

Figure 1.

- Cover of the 1973 The ACA Journal of Chiropractic and the introductory statement that was prepared in 1966. The 8-page supplement titled “Chiropractic of Today” addressed chiropractic as a profession and a science, the nature of disease, the subluxation as a clinical entity, infectious diseases, public health, chiropractic education, and the duties and rights of a profession.

Chiropractic, in contrast with medicine and the osteopathy of today, does not employ drugs or surgery. In its approach it endeavors to establish and maintain optimal physiological activity by correcting abnormal structural relationships. Its goal is to organize the body in such a manner as to enable it to utilize its own biological resources for a return to normal function. Its focal point of concern is with the integrity of the nervous system, because the nervous system integrates and coordinates all function in the body in response to internal and external environmental change. Any mechanical, chemical, and/or psychological irritation of the neurological component is capable of producing dysfunction and thus initiating disease in the susceptible individual... The chiropractor is concerned with the integrity of the entire body, the spinal column remaining his primary interest.58

This group represented the spectrum of chiropractic, including the broad scope/mixer and narrow scope/straight views, and clarified chiropractic of their current time. Their points addressed many of the errors or outdated materials that the AMA was using to attack chiropractic. Myths that were used in AMA propaganda included that all chiropractors believed in “one cause, one cure” (ie, that adjustments cured everything) or that chiropractors did not believe in the germ theory. To address these misconceptions, the authors clarified the profession's stance by stating,

It is a widespread misconception that “chiropractors do not believe in germs.” Nothing can be further from the truth, since it is the chiropractic concept that environmental factors (and “germs” constitute an inescapable component of the environment) determine health and disease. Furthermore, this is not a matter of belief or disbelief but a realistic scientific appraisal of the germ theory... Freedom from infectious disease is not dependent upon the absence of microorganisms (a condition never realizable because, as previously stated, bacteria are ubiquitous), but upon maintenance of normal physiological activity despite their presence... The chiropractic profession makes no claim to a panacea, nor does it seek to encroach upon the specialized methods of others.58

The campaigns from the 1950s and 1960s to improve chiropractic education, be included in Medicare, and gain licensure were finally showing results in the 1970s. After arduous battles against organized medicine spanning over 70 years that required addressing 1 state at a time, chiropractic had successfully obtained licensure for all 50 US states by 1974.43 In that same year, the Council on Chiropractic Education received recognition from the US Commissioner of Education, Department of Health, Education and Welfare to be included on the list of Nationally Recognized Accrediting Agencies and Associations.43 The year 1974 was also when chiropractic was successfully included in Medicare.59 Thus, despite the extensive efforts by the CoQ, the chiropractic profession was still able to progress.

Yet, even though the CoQ had been shuttered, damage had been done to chiropractic. The AMA leaders recognized that the CoQ had accomplished many of its goals. “The AMA believed that chiropractic would have achieved greater growth if it had not been for the Committee's activities.”60

In 1974, the American Chiropractic Association's (ACA's) president may have been prophetic that the AMA was losing its war on chiropractic. The publication of his address coincided with the end of the CoQ:

The American Medical Association appears to be losing credibility with its own membership. It is also losing the battle against chiropractic. AMA thinking must change and become attuned to the times if it is going to retain credibility with its own people.

We have said for years and will continue to say – chiropractic is not a panacea or a cure-all, but we are a very necessary part of the health-care delivery system. This is why we have survived against tremendous odds, the AMA's wealthy treasury and the political muscle that AMA flexes, but so often to its embarrassment.61

The CoQ Plan Is Exposed

The CoQ worked successfully in private for more than a decade, and it was likely that the AMA assumed that their secrets would remain hidden. However, the AMA had developed enemies through their various campaigns, and their veil of secrecy would eventually be torn open.

Previous AMA anti-quackery efforts included targeting scientology. The Church of Scientology stated that the AMA “during the 1950s and ‘60s, campaigned to discredit scientology and that the AMA is responsible for much of what is wrong with American health care.”62

The AMA had branded Dianetics (the practice of scientology) as quackery.63 Ralph Lee Smith, the same person hired to write the AMA's anti-chiropractic propaganda book, At Your Own Risk: The Case Against Chiropractic, wrote an article in the AMA publication, Today's Health, denouncing scientology as a cult. Smith wrote,

Couched in pseudoscientific terms and rites, this dangerous cult claims to help mentally or emotionally disturbed persons – for sizable fees. Scientology has grown into a very profitable worldwide enterprise... and a serious threat to health... Scientology is a cult which thrives on glowing promises that are heady stuff for the lonely, the weak, the confused, the ineffectual, and the mentally or emotionally ill.64

This publication by Smith and other AMA efforts added impetus for the leaders within the Church of Scientology to develop ways to make a counterattack. The church leaders devised a plan to address the issue at the core—from within the AMA headquarters.

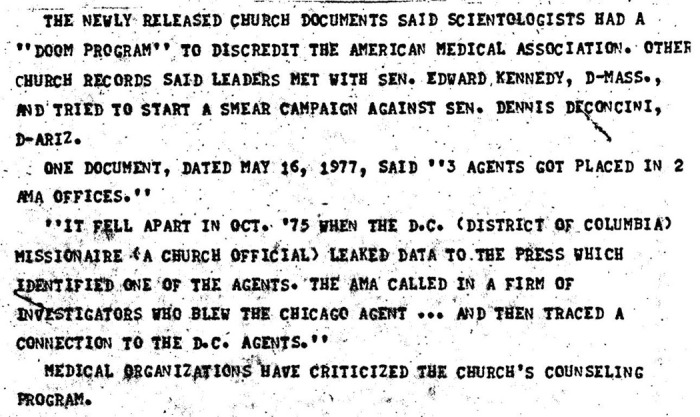

Scientology and the Book “In the Public Interest”

Scientology leaders planned to strike back at the AMA with what they called “Operation AMA Doom” (Fig. 2).65 In this plan, scientology leader L. Ron Hubbard issued an order to infiltrate AMA headquarters. Michael Meisner, a high-ranking church official,66 and Peter Joseph Lisa, Assistant Guardian for Information for the Church of Scientology, reportedly helped to implement the project and, using themselves and others, gained access to information at the AMA headquarters located in Chicago.67 Lisa reported that he went undercover by presenting himself as a journalist who was writing about quackery. Several female scientology agents reportedly secured positions as secretaries in AMA offices. These spies worked in departments that handled sensitive documents. Between 1969 and 1972, they photocopied or removed thousands of documents from the AMA building.

Figure 2.

- This is a section of notes describing the Church of Scientology's “Doom Program,” which was created to discredit the AMA. Included is the mention that multiple people were involved in the covert plan.

Scientology ‘Doom Program' Infiltrated Medical Group. Leaders of the Church of Scientology considered the American Medical Association and the National Institute of Mental Health enemies and infiltrated the AMA as part of an effort to discredit it, according to documents made public Thursday.68

Some of the AMA documents retrieved in the early part of Operation AMA Doom focused on chiropractic. A selection of these documents was later included in a book titled In the Public Interest. So as to not reveal the authors' true identities, a fake author name, “William Trever,” was assigned to the book.69 It is suspected that Michael Meisner, Peter Joseph Lisa, and likely a combination of other scientologists were the organizers or involved with this publication.

The book In the Public Interest included reproductions of stolen documents from AMA headquarters and had commentary embedded throughout. The language in the book aimed to incite an emotional response from chiropractors. “Behind the closed, guarded doors of the AMA headquarters there is an elite and secretive group of men who have worked with the diligence, tenacity, shrewdness and deceit of the KGB, Gestapo and the CIA combined.”69 The authors encouraged the reader to envision the AMA as an evil entity, using terms such as “Nazi intelligence agency,” “Machiavellian Think Tank,” and “satanic deceptive disciples” (Fig. 3).69 Although the book has a bibliography, no proper citations were included. Much of the text goes beyond the contents of the stolen documents, suggesting that those assembling the document were familiar with AMA and other publications on the topic of chiropractic.69

Figure 3.

- Cover of the book, In the Public Interest, published in 1972. A swastika was printed behind the medical symbol, the rod of Aesculapius. This imagery may have been included to suggest the sinister intentions of the American Medical Association.

The Church of Scientology leaders avoided association with the stolen AMA documents and the publication of the book. They arranged to distribute copies with the hopes that leaders within the chiropractic profession would take action against the AMA. However, because of the pervasive internal strife within the chiropractic profession, their desired response for action against the AMA did not occur immediately. Following the distribution of the book, the Church of Scientology distributed other AMA documents. Packages were sent to entities such as The Washington Post, Congressional committees, and the Internal Revenue Service. These packages contained materials, in addition to chiropractic topics, with the intent to undermine the AMA.70

Other packages included documents suggesting that

...the A.M.A.'s efforts to assure that doctors who shared its political philosophy were appointed to federal advisory panels. Another set revealed how the A.M.A.—which publicly asserts its independence of the nation's $8.4 billion-a-year pharmaceutical industry—decided to permit representatives of drug companies in its scientific policymaking body. A third packet told how the A.M.A. and the drug companies, which had earlier contributed $851,000 to AMPAC, joined forces to help kill 1970 legislation designed to provide patients with less expensive medicines. Other papers have linked the A.M.A. with the Nixon Administration's lobbying efforts...71

Federal Investigation

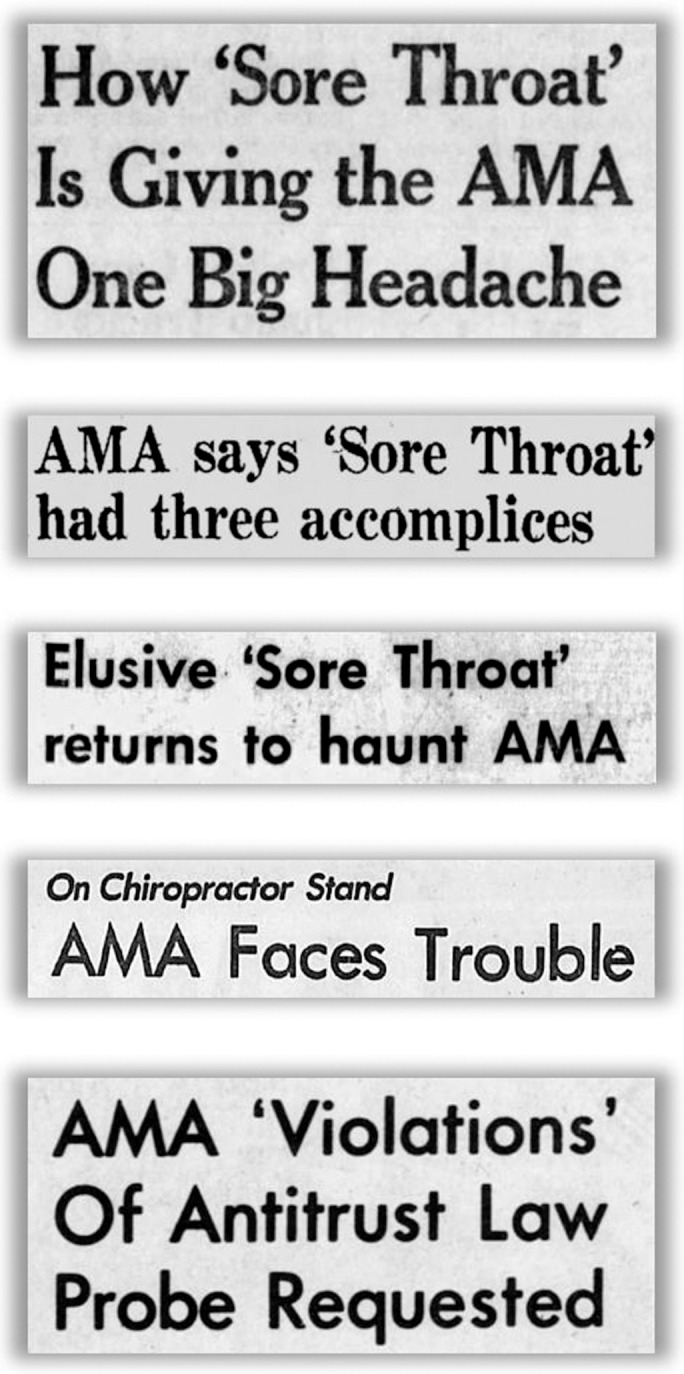

Because it was unknown at the time who was distributing the revealing AMA documents, the moniker “Sore Throat” was given to name the source. Articles about the AMA activities from the documents leaked by Sore Throat appeared in newspapers across the United States, such as this one from Pittsburgh:

Embattled American Medical Association (AMA) gets another headache: possibility of full-scale probe of its non-medical activities by Senate permanent investigations subcommittee. Poring over two-foot stack of confidential AMA memos dumped in their lap by disgruntled ex-AMA employee (who has been dubbed ‘Sore Throat'), Senate investigators zero in on issue of why AMA paid no taxes on so-called unrelated business income, including millions of dollars' worth of ads in AMA publications. Internal Revenue Service already is investigating AMA tax status while Postal Service ponders yanking AMA's special mail rates because of political activities of AMA's fund-raising arm. Meanwhile, officials in AMA's Chicago headquarters have hired security agent, changed locks, stopped writing ‘confidential memos,' started giving lie detector tests to employees in frantic effort to uncover the identity of ‘Sore Throat.'72

The leaked materials prompted a federal investigation. Representative John E. Moss, chairman of the House Oversight and Investigation subcommittee, was concerned that the AMA was potentially violating antitrust law. It was reported that Moss said,

these documents may raise the issue of possible antitrust violations by the A.M.A.' He said that attention should focus on those of the documents, ‘wherein there was either a stated intent by the A.M.A. to eliminate the chiropractic profession or plans were outlined to carry out that intent via harassment, delicensing and inducement of the boycotting of chiropractic services.73

The information within the documents seemed to demonstrate an antitrust violation. Thus, the materials were sent to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).

On the morning of October 29, 1975, news broke that “the staff of the House Oversight, and Investigation subcommittee has concluded that the campaign of the AMA to eliminate chiropractic service in the United States may violate the antitrust laws.”73 The subcommittee forwarded the documents on to the FTC for review “wherein there was either a stated intent by the AMA to eliminate the chiropractic profession or plans were outlined to carry out that intent via harassment, delicensing and inducement of the boycotting of chiropractic services.” Newspaper headlines of the uncovered activities crossed the nation: the AMA CoQ activities were no longer a secret (Fig. 4).74–78

Figure 4.

- Sample headlines as the result of Operation AMA Doom and the informant with the code name Sore Throat.74–78

The International Chiropractors Association (ICA) issued a press release confirming its awareness of the new information.79 Within a week of the FTC receiving the AMA documents, both the ACA and ICA received requests as to whether legal action was pending against the AMA. The ICA had hoped that the FTC would conclude in favor of the chiropractic profession, thus making any legal action from the ICA unnecessary. Jerome McAndrews wrote, “Let's hope that the FTC vigorously pursues the information given it by the Subcommittee. It could save all of us... a great deal of effort and perhaps heartache.”80 However, pursuit by the FTC of the AMA's activities pertaining to chiropractic never materialized.

A series of anonymously sent packages, purportedly sent by Sore Throat, were also received by chiropractic association leaders and chiropractic institutions. The packages included the documents that were allegedly smuggled from AMA headquarters. The chiropractic leaders recognized that these documents could possibly lead to an antitrust lawsuit against the AMA. However, the chiropractic associations were reluctant to take any steps, either alone or in collaboration, to pursue a lawsuit. Meanwhile, a few chiropractors had been considering whether they would be able to file an antitrust suit against the AMA. The newly revealed documents had given them hope to finally take action.

DISCUSSION

In the 1960s and 1970s, American consumer attitudes were changing, and regular medicine's paternalistic approach to health care was no longer favored.81 Consumer advocates were questioning authority and were demanding more transparency and control over what care they were receiving.82 Thus, the time seemed ripe for action against a medical monopoly in health care.

The AMA's arguments against chiropractic were not new. Since its beginning in 1847, the AMA had developed a culture of exclusivity and exclusion of other health professions that proposed they were equal or an alternate. Thus, the AMA had influenced the culture of America for more than a century. Despite its declining numbers and popularity, it was still the authoritative organization as it related to health care. Thus, the American population continued to view the information distributed from AMA headquarters as factual, without knowing that some of the information may have been used for political purposes.

The AMA continued to exert its authority by guiding state medical associations about what to do regarding the control of chiropractic. As an example, according to records from 1973, “Resolved, that the Michigan State Medical Society inform its membership that it is considered unethical by the American Medical Association and henceforth by the Michigan State Medical Society for a doctor of medicine to refer a patient to a chiropractor for any reason.”83 Thus, the AMA controlled regions throughout the United States.

In the early 1970s, the AMA leadership recognized that their lawsuits were taking a toll on the financial health of the association and that there were diminishing returns on the fight to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession. Within their financial crisis, the AMA disbanded the CoQ before the Wilk v AMA lawsuit was filed and long before it went to trial in 1980. Thus, the lawsuit was not the cause of the AMA's decision to disband the committee.

Yet, the CoQ had been working covertly for many years. It is unknown how much direct or indirect damage the AMA campaign inflicted on the reputation or clinical practices of the chiropractic profession during the decade that the CoQ was in existence. The damage to chiropractors remained, and the AMA made no efforts for reparations.

The amount of evidence that was revealed from Operation Doom showed a systematic and concerted effort by the AMA and other medical associations to discredit and eliminate the chiropractic profession. The AMA was continuing its tradition to exclude all other health professions from participating in health care for the American public. Because the association developed its own health care infrastructure, it is not surprising that it forbade chiropractors from being allowed into hospitals or medical clinics. This helps to explain some of the friction between the 2 professions. Even if some medical doctors in the 1960s and 1970s wanted to collaborate with chiropractors in the best interest of their patients, the medical doctors' political body (the AMA) forbade interprofessional interaction at that time.

For decades, American medical students and medical physicians were indoctrinated in an anti-chiropractic paradigm without fully knowing the facts. Because the AMA distributed “quack packs” to medical students that besmirched chiropractic, young medical doctors went into practice thinking that it would be unethical to work with chiropractors. After graduating, medical doctors continued to receive reinforcing AMA messages that to interact with a chiropractor would put their license or hospital privileges in jeopardy. Even after the CoQ was terminated, its anti-chiropractic propaganda continued to influence health care practices. Thus, some patients continued to hear from their medical doctor to stop seeing their chiropractor and were threatened that, if they did not, they would be dropped from their medical care.

Patients who were happy with their chiropractic care were often left with a choice, either not tell their medical doctor and continue to see their chiropractor or risk repercussions from their medical doctors. It is likely that patients learned to compartmentalize their health care activities, not informing their medical doctors of their chiropractic care, and vice versa, to reduce conflict or emotional distress when confronted.84 In practice, we, the authors, have heard our patients state that they “believe in chiropractic”—as if chiropractic was taboo or a religion to be believed in. Patients may do this as a way of negotiating their situation within what they perceive to be conflicting views of medicine against chiropractic.

The AMA boycott suppressed formalized referral relationships between medical doctors and chiropractors. Because of this information void, many medical doctors were unaware of the amount of training that chiropractors must complete before licensure, the scope of chiropractic practice, or even what chiropractors do in practice. Under these circumstances, it was not surprising that researchers later discovered that there was “little information communicated,” and poor referral relationships were the norm between medical doctors and chiropractors.85,86

The AMA made no effort in the 1970s to reverse its position on chiropractic to the public. The public continued to believe that chiropractors were potentially ineffective and unsafe, even though there were no scientific studies to support the AMA's claim.

There were an estimated 20,000 chiropractors in the United States in 1975,78 and the chiropractic profession continued to improve its education programs and gain its legal status. Yet, even with this growth, the anti-chiropractic environment established by the AMA continued to have a negative impact on chiropractic practice. Some chiropractors felt that the tensions in the health care work environment were becoming unbearable, and they began to seek a solution.

Limitations

This historical narrative reviews events from the context of the chiropractic profession, and the viewpoints are limited by the authors' framework and worldview. Other interpretations of historic events may be perceived differently by other authors. The context of this article must be considered in light of the authors' biases as licensed chiropractic practitioners, educators, and scientific researchers.

The primary sources of information were written testimony, oral interviews, public records, legal documents, minutes of meetings, newspapers, letters, and other artifacts. These formed the basis for our narrative and timeline. We acknowledge that recall bias is an issue when referencing sources, such as letters, in which people recount past events. Secondary sources, such as textbooks, trade magazines, and peer-reviewed journal articles, were used to verify and support the narrative. We collected thousands of documents and reconstructed the events relating to the Wilk v AMA lawsuit. Since no electronic databases exist that index many of the publications needed for this research, we conducted page-by-page hand searches of decades of publications. While it is possible that we missed some important details, great care was taken to review every page systematically for information. It is possible that we missed some sources of information and that some details of the trials and surrounding events were lost in time. The above potential limitations may have affected our interpretation of the history of these events.

Some of our sources were interviews, manuscripts, or letters in which the author recalled past events. Recall bias is an issue when referencing interview sources. Surviving documents from the first 80 years of the chiropractic profession, the years leading up to the Wilk v AMA lawsuit, are scarce. Chiropractic literature existing before the 1990s is difficult to find, since most of it was not indexed. Many libraries have divested their holdings of older material, making the acquisition of early chiropractic documents challenging. While we were able to obtain some sources from libraries, we also relied heavily on material from our own collection and materials from colleagues. Thus, there may be relevant papers or artifacts that were inadvertently missed. Our interpretation of the events related to the trials is limited to the materials available. The information regarding this history is immense, and because of space limitations, not all parts of the story could be included in this series.

CONCLUSION

After more than a decade of overt and covert actions, the AMA chose to end its Committee on Quackery, whose primary mission was to “contain and eliminate” the chiropractic profession. The following year, documents exposed the extent of the efforts that the AMA had implemented to enact its boycott of chiropractic. These documents would later be considered and used as evidence in the Wilk v AMA lawsuit.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the following people for their detailed reviews and feedback during development of this project: Ms Mariah Branson, Dr Alana Callender, Dr Cindy Chapman, Dr Gerry Clum, Dr Scott Haldeman, Mr Bryan Harding, Mr Patrick McNerney, Dr Louis Sportelli, Mr Glenn Ritchie, Dr Eric Russell, Dr Randy Tripp, Mr Mike Whitmer, Dr James Winterstein, Dr Wayne Wolfson, and Dr Kenneth Young.

FUNDING AND CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

This project was funded and the copyright owned by NCMIC. The views expressed in this article are only those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of NCMIC, National University of Health Sciences, or the Association of Chiropractic Colleges. BNG is the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Chiropractic Education, and CDJ is on the NCMIC board and the editorial board of the Journal of Chiropractic Education. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wilk et al v American Medical Association et al Nos. 1990;87-2672:87–2777. 895 F.2d 352 (7th Cir. 1990), United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McAndrews GP, Malloy TJ, Shifley CW, Ryan RC, Horton A, Resis RH. Plaintiffs' Summary of Proof as an Aid to the Court Civil Actlon No 76 C 3 777. Chicago, IL: Allegretti, Newltt, Witcoff & McAndrews, Ltd; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 4: committee on Quackery. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):55–73. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Committee on Quackery Minutes 1964-1974. Chicago IL American Medical Association; 1964–1974.

- 5.Wilk v AMA No. 87-2672 and 87-2777 (F. 2d 352 Court of Appeals 7th Circuit April 25, 1990)

- 6.Haldeman S, Chapman-Smith D, Petersen DM. Guidelines for Chiropractic Quality Assurance and Practice Parameters Proceedings of the Mercy Center Consensus Conference. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishing; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson C. What is the Association of Chiropractic Colleges Educational Conference and Research Agenda Conference? J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30(4):249–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson C, Green B. The Association of Chiropractic Colleges Educational Conference and Research Agenda Conference: 17 years of scholarship and collaboration. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33(3):165–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mootz RD, Hansen DT, Breen A, Killinger LZ, Nelson C. Health services research related to chiropractic: review and recommendations for research prioritization by the chiropractic profession. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(9):707–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haas M, Bronfort G, Evans RL. Chiropractic clinical research: progress and recommendations. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(9):695–706. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mrozek JP, Till H, Taylor-Vaisey AL, Wickes D. Research in chiropractic education: an update. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(9):762–773. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cramer G, Budgell B, Henderson C, Khalsa P, Pickar J. Basic science research related to chiropractic spinal adjusting: the state of the art and recommendations revisited. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(9):726–761. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bigos SJ, Bowyer OR, Braen GR, et al. Acute low back problems in adults. Acute Lower Back Problems in Adults. 1994. In. Clinical Practice Guidelines No. 14. AHCPR Publication No. 95-0642. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research.

- 14.Haldeman S, Carroll L, Cassidy JD, Schubert J, Nygren A. The Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders: executive summary. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(2 suppl):S7–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson C, Baird R, Dougherty PE, et al. Chiropractic and public health: current state and future vision. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(6):397–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson C, Green BN. Public health, wellness, prevention, and health promotion: considering the role of chiropractic and determinants of health. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(6):405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egan J, Baird R, Killinger L. Chiropractic within the American Public Health Association, 1984–2005: pariah, to participant, to parity. Chiropr Hist. 2006;26:97–117. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haldeman S, Nordin M, Chou R, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: World Spine Care executive summary on reducing spine-related disability in low- and middle-income communities. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(suppl 6):776–785. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5722-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green BN, Johnson CD, Haldeman S, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: public health and prevention interventions for common spine disorders in low- and middle-income communities. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(suppl 6):838–850. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5635-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson CD, Haldeman S, Nordin M, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: methodology, contributors, and disclosures. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):786–795. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5723-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haldeman S, Johnson CD, Chou R, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: care pathway for people with spine-related concerns. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):901–914. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5721-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haldeman S, Johnson CD, Chou R, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: classification system for spine-related concerns. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):889–900. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5724-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson CD, Haldeman S, Chou R, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: model of care and implementation. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):925–945. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5720-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green BN, Johnson CD, Haldeman S, et al. A scoping review of biopsychosocial risk factors and co-morbidities for common spinal disorders. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0197987. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keating JC, Jr, Green BN, Johnson CD. “Research” and “science”: in the first half of the chiropractic century. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1995;18(6):357–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boon H, Verhoef M, O'Hara D, Findlay B, Majid N. Integrative healthcare: arriving at a working definition. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004;10(5):48–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hawk C, Nyiendo J, Lawrence D, Killinger L. The role of chiropractors in the delivery of interdisciplinary health care in rural areas. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1996;19(2):82–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lott CM. Integration of chiropractic in the Armed Forces health care system. Mil Med. 1996;161(12):755–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Branson RA. Hospital-based chiropractic integration within a large private hospital system in Minnesota: a 10-year example. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):740–748. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Green BN, Johnson CD, Lisi AJ, Tucker J. Chiropractic practice in military and veterans health care: the state of the literature. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2009;53(3):194–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boon HS, Mior SA, Barnsley J, Ashbury FD, Haig R. The difference between integration and collaboration in patient care: results from key informant interviews working in multiprofessional health care teams. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunn AS, Green BN, Gilford S. An analysis of the integration of chiropractic services within the United States military and veterans' health care systems. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):749–757. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldberg CK, Green B, Moore J, et al. Integrated musculoskeletal rehabilitation care at a comprehensive combat and complex casualty care program. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):781–791. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lisi AJ, Goertz C, Lawrence DJ, Satyanarayana P. Characteristics of Veterans Health Administration chiropractors and chiropractic clinics. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46(8):997–1002. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2009.01.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hawk C. Integration of chiropractic into the public health system in the new millennium. In: Haneline MT, Meeker WC, editors. Introduction to Public Health for Chiropractors. Boston, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2010. pp. 375–389. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green BN, Johnson CD, Daniels CJ, Napuli JG, Gliedt JA, Paris DJ. Integration of chiropractic services in military and veteran health care facilities: a systematic review of the literature. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2016;21(2):115–130. doi: 10.1177/2156587215621461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salsbury SA, Goertz CM, Twist EJ, Lisi AJ. Integration of doctors of chiropractic into private sector health care facilities in the United States: a descriptive survey. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018;41(2):149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Green BN, Johnson CD. Interprofessional collaboration in research, education, and clinical practice: working together for a better future. J Chiropr Educ. 2015;29(1):1–10. doi: 10.7899/JCE-14-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson C. Health care transitions: a review of integrated, integrative, and integration concepts. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):703–713. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hirschheim R, Klein HK. Four paradigms of information systems development. Communications of the ACM. 1989;32(10):1199–1216. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Porra J, Hirschheim R, Parks MS. The historical research method and information systems research. J Assoc Info Syst. 2014;15(9):3. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lune H, Berg BL. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. Harlow, UK: Pearson; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 2: rise of the American Medical Association. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):25–44. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 3: chiropractic growth. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):45–54. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 6: preparing for the lawsuit. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):85–96. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 7: lawsuit and decisions. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):97–116. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 8: Judgment impact. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):117–131. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 1: origins of the conflict. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):9–24. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.To fight or not to fight. Am Med Assoc Bull. 1923;17(2):283. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blackstone EA. The AMA and the osteopaths: a study of the power of organized medicine. Antitrust Bull. 1977;22:405. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baer HA. The organizational rejuvenation of osteopathy: a reflection of the decline of professional dominance in medicine. Soc Sci Med Part A Med Psychol Med Sociol. 1981;15(5):701–711. doi: 10.1016/0271-7123(81)90093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilk v AMA No. 76 C 3777 (ND IM June 1 1987)

- 53.Nadel AT. Different look at chiropractic. N Engl J Med. 1971;285(12):692. doi: 10.1056/nejm197109162851224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smothers D. AMA undergoing changes—future status pondered. Valley Morning Star. 1975. April 27. 66.

- 55.AMA money crisis: medical group cuts operations. TimesAdvocate. 1975. June 16. 3.

- 56.AMA going broke. The Town Talk. 1975. June 15. 5.

- 57.Parachini A. AMA losing money, members - and power. Des Moines Tribune. 1975. June 14. 1.

- 58.Bittner H, Harper W, Homewood A, Janse J, Weiant C. Chiropractic of today. ACA J Chiropr. 1973;10(11) [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wardwell WI. Chiropractic History and Evolution of a New Profession St Louis. MO: Mosby-Year Book; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wilk vAmerican Medical Ass'n 671 1465(Dist. Court, ND Illinois 1987)

- 61.Bromley W. AMA—is political honesty finally emerging? Am Chiropr Assoc J Chiropr. 1974;11(9):12. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rawitch R, Gillette R. Church wages propaganda on a world scale. Los Angeles Times. 1978. August 27. 1.

- 63.United States of America v Jane Kember and Morris Budlong. United States District Court for the District of Columbia No. 78-401(2) and (3) Dec 16 1980)

- 64.Smith RL. Scientology—menace to mental health. Today's Health. Dec, 1968. 34.

- 65.Margasak L. Scientologists. Church of Scientology/L Ron Hubbard 62117658A. 1979. pp. 231–232. In. Washington, DC: Federal Bureau of Investigation.

- 66.Kiernan LA. Harsh penalties urged in scientology case. Washington Post. 1979 December 4. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1979/1912/1904/harsh-penalties-urged-in-scientology-case/1977c1916f1976e1978-1521f-4332-b1364-5479f1925a1938b/

- 67.Lisa PJ. The Assault on Medical Freedom. Newburyport, MA: Hampton Roads; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Scientology ‘Doom Program' infiltrated medical group. Albuquerque Journal. 1979. November 2. 3.

- 69.Trever W. In the Public Interest. Los Angeles, CA: Scriptures Unlimited; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Auerbach S. Drug firms' AMA gifts revealed. CourierNews. 1975. July 1.

- 71.Medicine: Sore Throat attacks. Time. 1975;106 August 18:52. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Embattled American Medical Association. Pittsburgh Press. 1975. August 10. 29.

- 73.Burnham D. AMA criticized on chiropractic. New York Times. 1975. October 29. 60.

- 74.Hines W. How “Sore Throat” is giving the AMA one big headache. Des Moines Tribune. 1975. August 13. 1.

- 75.AMA says “Sore Throat” had three accomplices. Des Moines Register. 1975. October 18. 5.

- 76.Elusive “Sore Throat” returns to haunt AMA. Miami News. 1975. October 24. 3.

- 77.On chiropractor stand AMA faces trouble. Honolulu StarBulletin. 1975. October 29. 24.

- 78.AMA “violations” of antitrustlaw probe requested. Statesman Journal. 1975. October 29. 41.

- 79.For immediate release [press release]. Davenport: International Chiropractors Association, October 29, 1975

- 80.McAndrews JF. Letter to Louis Sportelli November 6, 1975

- 81.Chin JJ. Doctor-patient relationship: from medical paternalism to enhanced autonomy. Singapore Medical Journal. 2002;43(3):152–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ameringer CF. The Health Care Revolution From Medical Monopoly to Market Competition Vol 19. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wilk v AMA No. 76 C 3777 (ND IM December 9 1980)

- 84.Robinson A, McGrail MR. Disclosure of CAM use to medical practitioners: a review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Complement Ther Med. 2004;12(2–3):90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mainous AG, III, Gill JM, Zoller JS, Wolman MG. Fragmentation of patient care between chiropractors and family physicians. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(5):446–450. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.5.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Greene BR, Smith M, Allareddy V, Haas M. Referral patterns and attitudes of primary care physicians towards chiropractors. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2006;6(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]