Abstract

Objective

This paper is the second in a series that explores the historical events surrounding the Wilk v American Medical Association (AMA) lawsuit in which the plaintiffs argued that the AMA, the American Hospital Association, and other medical specialty societies violated anti-trust law by restraining chiropractors' business practices. The purpose of this paper is to provide a brief review of the history of how the AMA rose to dominate health care in the United States, and within this social context, how the chiropractic profession fought to survive in the first half of the 20th century.

Methods

This historical research study used a phenomenological approach to qualitative inquiry into the conflict between regular medicine and chiropractic and the events before, during, and after a legal dispute at the time of modernization of the chiropractic profession. Our methods included obtaining primary and secondary data sources. The final narrative recount was developed into 8 papers following a successive timeline. This paper is the second of the series that explores the growth of medicine and the chiropractic profession.

Results

The AMA's code of ethics established in 1847 continued to direct organized medicine's actions to exclude other health professions. During the early 1900s, the AMA established itself as “regular medicine.” They labeled other types of medicine and health care professions, such as chiropractic, as “irregulars” claiming that they were cultists and quacks. In addition to the rise in power of the AMA, a report written by Abraham Flexner helped to solidify the AMA's control over health care. Chiropractic as a profession was emerging and developing in practice, education, and science. The few resources available to chiropractors were used to defend their profession against attacks from organized medicine and to secure legislation to legalize the practice of chiropractic. After years of struggle, the last state in the US legalized chiropractic 79 years after the birth of the profession.

Conclusion

In the first part of the 20th century, the AMA was amassing power as chiropractic was just emerging as a profession. Events such as publication of Flexner's report and development of the medical basic science laws helped to entrench the AMA's monopoly on health care. The health care environment shaped how chiropractic grew as a profession. Chiropractic practice, education, and science were challenged by trying to develop outside of the medical establishment. These events added to the tensions between the professions that ultimately resulted in the Wilk v AMA lawsuit.

Keywords: Health Occupations; Chiropractic; Medicine; Humanities; History, 20th Century; Antitrust Laws

INTRODUCTION

There are few professions that can declare the year, let alone the exact day, that their profession started. The chiropractic profession is apparently a rare case. DD Palmer reportedly declared the discovery of chiropractic on September 18, 1895.1,2 Regardless if the date is accurate or figurative, this date marks that chiropractic was an emerging profession during a time in which the self-declared “regular” medical physicians were growing into power in the United States. These early years set the stage for conflict that eventually resulted in the Wilk v American Medical Association (AMA) lawsuit.3,4

The historical events surrounding this lawsuit are important for chiropractors today. This history helps to explain the recent surge in scientific growth5–24 and the improved access to chiropractic care after the barriers that were erected by the AMA were finally removed.25–38 These events clarify chiropractic's previous struggles and how past experiences influence current social constructs. The obstacles and challenges that chiropractic overcame help explain some of the current culture and identify issues that the chiropractic profession may need to address in the future.

The purpose of this paper is to provide a brief review of the history of how the AMA rose to dominate health care in the United States and within this context, how the chiropractic profession fought to survive in the first half of the 20th century. This paper reviews the AMA's rise in power and some of the methods that chiropractors used to survive during a time in which they were battling against basic science laws and fighting for licensure so that they could practice legally. The early years of the development of chiropractic's practice, research, and education are discussed. These issues contribute to a better understanding of the events resulting in the Wilk v AMA lawsuit.

METHODS

This historical study used a phenomenological approach to qualitative inquiry into the conflict between regular (orthodox) medicine and chiropractic and the events before, during, and after a legal dispute at the time of modernization of the chiropractic profession. The metatheoretical assumption that guided our research was a neo-humanistic paradigm. As described by Hirschheim and Klein, “The neohumanist paradigm seeks radical change, emancipation, and potentiality, and stresses the role that different social and organizational forces play in understanding change. It focuses on all forms of barriers to emancipation-in particular, ideology (distorted communication), power, and psychological compulsions and social constraints-and seeks ways to overcome them.”39 We used a pragmatic and postmodernist approach to guide our research practices, such that objective reality may be grounded in historical context and personal experiences and interpretation may evolve with changing perspectives.40

We followed techniques described by Lune and Berg.41 These steps included identifying the topic area, conducting a background literature review, and refining the research idea. After this we identified data sources and evaluated the source materials for accuracy. Our methods included obtaining primary data sources: written testimony, oral interviews, public records, legal documents, minutes of meetings, newspapers, letters, and other artifacts. Information was obtained from publicly available collections on the internet, university archives, and privately owned collections. Secondary sources included scholarly materials from textbooks, and journal articles. The materials were reviewed and then we developed a narrative recount of our findings.

The manuscript was reviewed for accuracy, completeness, and content validity by a diverse panel of experts, which included reviewers from various perspectives within the chiropractic profession ranging from broad-scope (mixer) to narrow-scope (straight) viewpoints, chiropractic historians, faculty and administrators from chiropractic degree programs, corporate leaders, participants who delivered testimony in the trials, and laypeople who are chiropractic patients. The manuscript was revised based on the reviewers' feedback and returned for additional rounds of review. The final narrative recount was developed into 8 papers that follow a chronological storyline.4,42–47 This paper is the second of the series that considered events relating to the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession and explores the AMA's rise in power and how the chiropractic profession continued to develop during the first half of the 20th century.

RESULTS

AMA Gains Power

Since its founding in 1847, the AMA gradually amassed resources and power through its cohesive structure and large membership. In the early 1900s, AMA members relied upon their association to provide legislative initiatives, scientific publications, recommendations for improvements in medical education, protection of regular medical practice from those who wished to encroach upon it, and recommendations for political alliances. The US health care infrastructure was based on the efforts of the AMA. Therefore, to survive in business, physicians became members of the AMA and their local medical societies.48

Dues were collected locally, and each local society member automatically became a member of the AMA. The AMA funds grew, adding to the power of the AMA. Income was generated from local society memberships and from subscriptions to the AMA's journal. If a physician desired to join the AMA, an additional $12 fee was charged for a subscription to the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA).49 Journal subscriptions and advertisements generated a significant cash flow for the AMA that helped to make the AMA a very powerful organization.50

The AMA governing structure included state societies electing their representatives to the AMA House of Delegates, from which were elected the AMA officers and board of trustees.50,51 The board of trustees, comprised of approximately 15 people during the mid-1900s, was responsible for deciding on many policies and for selecting a general manager who supervised the 900 AMA employees.49 The AMA had a significant controlling effect on local societies, the practice of medicine, and political issues that were promoted to be in the interest of AMA officers and members. It was said that, “The formal structure of the American Medical Association provides for the largest measure of direct democratic control in the county medical societies, and increasingly indirect representation at the state and national levels.”51

Most AMA members were busy treating patients and running practices and had no time or desire to engage in AMA political activities.51 Due to the passive membership of most medical physicians, a select cadre of members became the default leaders of the AMA and were referred to as “the active minority.”50 Officers in this elite group advanced in lockstep from lower to higher levels of leadership. Based upon this structure, the leadership was comprised of officers who would have influence over the AMA for many years.50 With an extensive budget, this elite group influenced AMA activities and policies and had a significant ability to influence the direction of medicine on a national scale.51 Over time, the association's rules became more rigid and controlling. With each passing decade, the AMA increased its opposition to anyone not an AMA member being granted privileges in hospitals or involved with hospitals in any way, and especially non-medical providers such as chiropractors.

The AMA's actions were based on one of the AMA's founding principles, which was to define what its leaders established to be science and to equate “science” with regular medicine. Anything that the AMA declared to be not scientific was therefore not approved to be included in regular medicine. The AMA continued its pursuit to prevent irregular practitioners, those who the AMA called “quacks,” from providing care to the American public. In 1924, the House of Delegates dictated “under no circumstances should a regular physician engage in consultation with a cultist of any description.”52 The AMA's tradition of excluding any other providers from practice was a central aim. Labeling other health care providers as “quacks” or “cultists” would continue for many decades and be used in their communications as attacks on chiropractic increased.

The AMA's combined actions of socially denigrating competing health professions, and controlling licensing laws and who could enter medicine resulted in the AMA becoming a policing organization for most activities related to health care in the United States.51 Over time, the US government relinquished many oversight functions to the AMA.48,53 Organized medicine thus gained control over determining what they considered to be acceptable health care practices. Starr describes the AMA's rise to power and authority:

From a relatively weak, traditional profession of minor economic significance, medicine has become a sprawling system of hospitals, clinics, health plans, insurance companies, and myriad other organizations employing a vast labor force. This transformation has not been propelled solely by the advance of science and the satisfaction of human needs. The history of medicine has been written as an epic of progress, but it is also a tale of social and economic conflict over the emergence of new hierarchies of power and authority, new markets, and new conditions of belief and experience.54

As the AMA leadership further developed its policing efforts, the committees and office staff actively scanned publications for any person or health movements that could potentially challenge or invade the practice of regular medicine.55 Over the years they developed an extensive collection of materials that they could use for propaganda and further their campaign.

When chiropractic was first publicized at the turn of the century, the AMA leadership considered chiropractic to be just another bizarre form of irregular practice.55 The first mention of chiropractic in an AMA publication that we are aware of was in the 1902 JAMA, in the Medical News section. The comments about chiropractic were not complimentary. The report states that the chiropractor was said to have been, “...jumping on and otherwise maltreating the patient.”56 Over the years, the notations and attacks on chiropractic grew in number and strength in the AMA's publications.55

Flexner's Report in 1910

In the early 1900s, the AMA leadership continued to advance its control over medical education in America. Medical schools—including eclectic medicine and homeopathic medicine in addition to regular medicine—were in a state of disarray.57 The AMA recognized that many medical programs were proprietary and standards remained low. With the strengthening position of the AMA, its leadership recognized the opportunity to gain further ground by eliminating competing schools and to strengthen the position of their regular medical schools. In 1908, the Council on Medical Education of the AMA proposed a study on medical education “to hasten the elimination of medical schools that failed to adopt the CME's standards.”58 The funder of this project, the Carnegie Foundation, hired Mr Abraham Flexner to review institutions in the United States and Canada. Flexner had no medical degree and only a bachelor's degree.59 While drafting his report, Flexner relied heavily on documents generated by the AMA.60

In 1910, Flexner's report, Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, was published and solidified a transformation of medical education in the United States.61 The report included many of the AMA's prior arguments, including harsh comments criticizing the proprietary nature of medical schools that resulted in an overabundance of ill-educated doctors who put the public's health at risk. “Men get in, not because the country needs the doctors, but because the schools need the money.”61

The report included aims to reduce the number of poorly trained medical doctors, to reduce the number of medical schools by 80%, and to increase prerequisites for medical school.61 The report offered 7 major recommendations:

reduce the number of poorly trained medical physicians;

reduce the number of medical schools;

increase the prerequisites to enter medical training;

train medical physicians to practice in a scientific manner;

engage faculty in research;

have medical schools control clinical instruction in hospitals; and

strengthen state regulation of medical licensure.60

After the report was published, there were dramatic changes in medical education. This was a death sentence for most irregular medical programs, including the eclectic and homeopathic medical schools.62 Within 20 years, the number of American medical schools decreased from 131 to 76. There was an increase in basic sciences and laboratory courses, and increased requirements for students entering medical school. Entrance requirements changed as well. Before the report in 1904, approximately 95% of medical schools required only a high school education. By 1929, 100% of the medical programs required at least 2 years of college education.60

Under AMA's influence, the principles from Flexner's report resulted in curricular changes and modifications to licensing laws to include basic sciences. State licensing board exams focused on basic science topics and resulted in limiting graduates from irregular medical programs and other health professions schools from becoming licensed.63,64 Since the AMA controlled licensing boards either directly or indirectly, boards were used to exclude practitioners not recognized by the AMA, including chiropractors. The AMA's influence on licensure furthered the AMA's control of who entered the health care marketplace.57

Chiropractic's Fight for Licensure

Licensure of health care professions is necessary to regulate and define the scope of practice. Licensure is granted by legislation, establishes a health care profession as legal within a region, and helps legitimize the profession that obtains it.65 When chiropractic was still an emerging profession, chiropractic licensure had not yet been implemented. Thus, chiropractors had no choice but to practice without licenses. In the early years of the profession, chiropractors fought to establish licensing laws and these legal and professional challenges continued to plague the chiropractic profession throughout the century.

In the early 1900s, leaders from the chiropractic schools and associations attempted to define chiropractic. They argued that chiropractors possessed a specialized body of knowledge and sought chiropractic licensure that would allow legal practice.66 These actions were in congruence with the rapidly developing concept of professionalization that emerged in North America in the late 19th century.67

Early efforts focused on establishing the profession and fighting legal and legislative battles. To survive, chiropractic organizations devoted their limited resources to defending chiropractors and establishing licensure in each state. It was essential to implement both licensure and legal defense because without licensure chiropractors could be accused of practicing medicine and without defense, chiropractic would lose its case of being separate and distinct from medicine and therefore cease to exist. These efforts required support and funding from members of the profession. However, resources were scarce since few chiropractors existed.

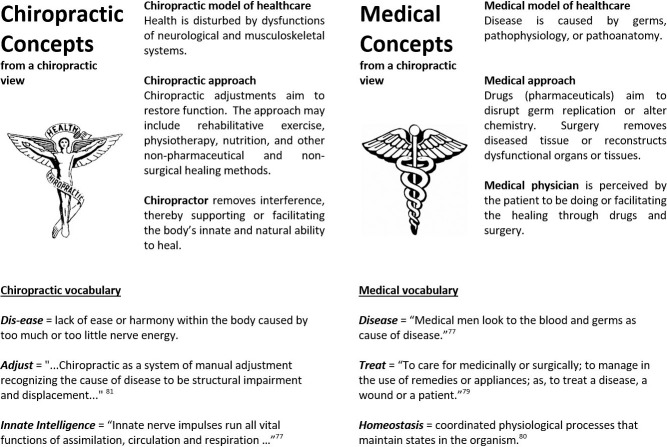

Medicine had been organized for over a half a century and continued to fulfill its mission, which included attempts to eradicate irregular professions. Organized medicine attacked chiropractic through legal persecution, accusing chiropractors of practicing medicine without a license. The earliest cases included DD Palmer in 1900 being accused under the Iowa medical practice act and in 1903, Bartlett Joshua “BJ” Palmer (DD Palmer's son) was accused of practicing medicine without a license.65 In 1906, DD Palmer was found guilty of practicing medicine without a license.68 (Fig. 1) Thus, 11 years after the founding of the profession, DD Palmer was the first chiropractor to go to jail for chiropractic.69

Figure 1.

- A notice from the 1906 Rock Island Argus, showing that DD Palmer was found guilty of practicing without a medical license. Although Chiropractic's founder had been brought to court previously during his quest to legalize chiropractic, he was the first chiropractor known to go to jail for practicing medicine without a license.

Hundreds of chiropractors were indicted for practicing medicine, osteopathy, or another non-chiropractic field without a license.70 Many chiropractors sacrificed themselves in a similar manner by serving jail time. For example in 1932, chiropractors went to jail 450 times in California in just 1 year.71 Of the documented 681 chiropractors incarcerated, many were jailed multiple times. The willingness to go to jail for chiropractic was a form of social protest against laws that chiropractors felt were unfair or oppressive.72 Most chiropractors were determined to serve their time in jail instead of paying their fines, as they were adamant that they were not practicing medicine. In some states, bail money was used to fund the prosecution of more chiropractors, thus by serving their time they protested further persecution (Fig. 2).73

Figure 2.

- Dr Linden D. McCash, a chiropractor who practiced in Berkeley, California, was arrested for practicing medicine without a license.

Scores of chiropractors were arrested, many were acquitted. But practically none of them paid fines. They preferred to go to jail rather than pay a small fine which would ultimately find its way into the coffers of the Medical Assn. to be used in the prosecutions of more chiropractors. Chiropractor McCash served two jail sentences of 60 and 90 days rather than pay a ridiculously small fine of $75. Such a spirit, when on the side of right, cannot be defeated.73

The Universal Chiropractors' Association (UCA) was the first nationwide legal defense system for chiropractors and was created in 1906.74 By then, BJ Palmer had assumed leadership of the Palmer School of Chiropractic and the UCA, which led the narrow-scope, straight chiropractic community. The straight chiropractors argued that only hand adjusting was considered chiropractic, and that chiropractic practice should not include adjunctive therapies. The UCA argued that chiropractic was separate from medicine and offered legal defense to its members if they were accused of practicing without a license.

An example of this defense strategy was used in the landmark chiropractic lawsuit held in Lacrosse, Wisconsin, in 1907. Dr. Shegetaro Morikubo, a graduate from the Palmer School of Chiropractic, was accused of practicing osteopathy without a license. In this case, the defense lawyer argued that chiropractic was a distinct profession and had a unique science, philosophy, and lexicon; therefore, the chiropractic profession should not be judged as if it were osteopathy.74 Their arguments were successful and Dr Morikubo won the case, which resulted in the continued use of the lexicon and arguments to protect chiropractic for many years.

The legal defense was built upon the rationale that the chiropractic profession was separate and distinct from orthodox medicine; therefore, chiropractors deserved to have their own separate licensure. For decades, the lawyers defending chiropractors' rights to practice would use the “separate and distinct” argument to win their cases.75 These early legal defense strategies not only won cases, but they also shaped the chiropractic identity for those in the profession and the public.

Legal defense strategies were successful and the UCA represented an estimated 3300 cases by 1927 in defense of the straight (hands-only adjustment of the spine) philosophy.69,76 The American Chiropractic Association of 1922–1930 (National Chiropractic Association's [NCA] predecessor) offered legal defense in a similar manner to its broad-scope, mixer chiropractic members.77,78 Broad-scope (mixer) practice included chiropractic adjustments of the spine, but also could include additional modalities such as physiotherapies, nutrition, exercise, or other adjunct therapies.

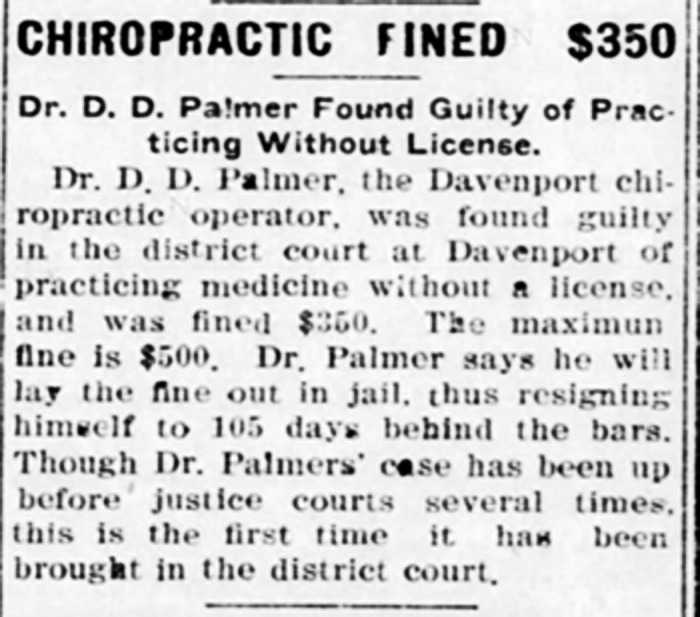

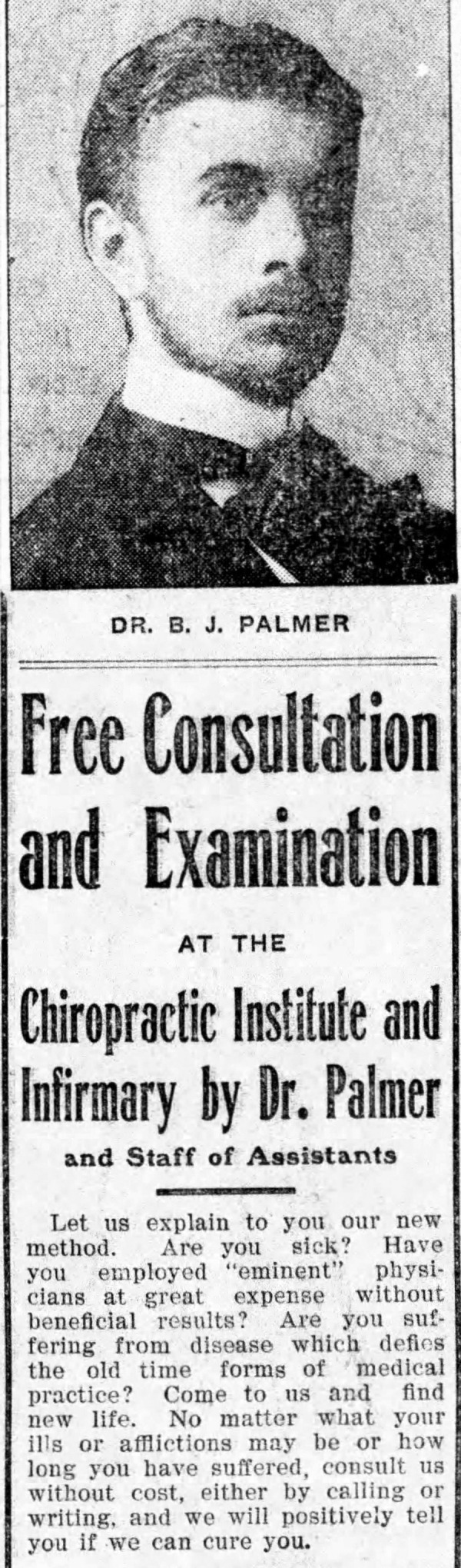

To survive, chiropractors developed a unique lexicon, separate from that of medicine (Fig. 3).79–84 This included chiropractic borrowing or modifying some medical terms, including the term subluxation.85,86 Unique chiropractic terminology was used to advertise, to communicate with patients, and to legally defend practitioners.87 In 1911, the UCA recognized the need to standardize legal terminology “...to decide upon what was and what was not Chiropractic, what the U.C.A. could admit as Chiropractic and could defend.” 88 Included in the UCA report given on the standardization of chiropractic, UCA's legal defense counsel (Tom Morris and Fred Hartwell) were commended for helping to define chiropractic: “Morris & Hartwell... are standardizing Chiropractic. They are telling the local attorney what Chiropractic really is.”88 Chiropractic terminology, concepts, and definitions were being refined for use in the courtroom, which then influenced legislation, advertising, and education.88 Thus, these legal arguments helped to shape the language and perceptions of the chiropractic profession.

Figure 3.

- Chiropractic views of chiropractic vs orthodox medicine. A comparison of terms from a historical chiropractic point of view. These are examples of terminology and concepts, which emphasized that chiropractic was different from medicine and to establish chiropractic as a separate and distinct healing profession, which was often used during legal battles. To protect themselves during legal attacks from organized medicine and osteopathy, chiropractors and their lawyers highlighted the unique chiropractic vocabulary, and their distinct science, philosophy, and practices. This strategy was often successful to win the case in favor of the chiropractor.

While some chiropractors were licensed under drugless practitioner acts, most chiropractic licensing laws were established by battles 1 state at a time. For example, before there was chiropractic legislation in Kansas, the board of medical examiners attempted to block chiropractors from practicing. In language that foreshadowed the AMA's use of the same description of chiropractic, the Kansas medical board described a “chiropractic problem” and their intent to order prosecutions throughout the state.89 However, chiropractors won eventually and in 1913 Kansas became the first state to adopt a chiropractic practice act specifically for chiropractors.65,90

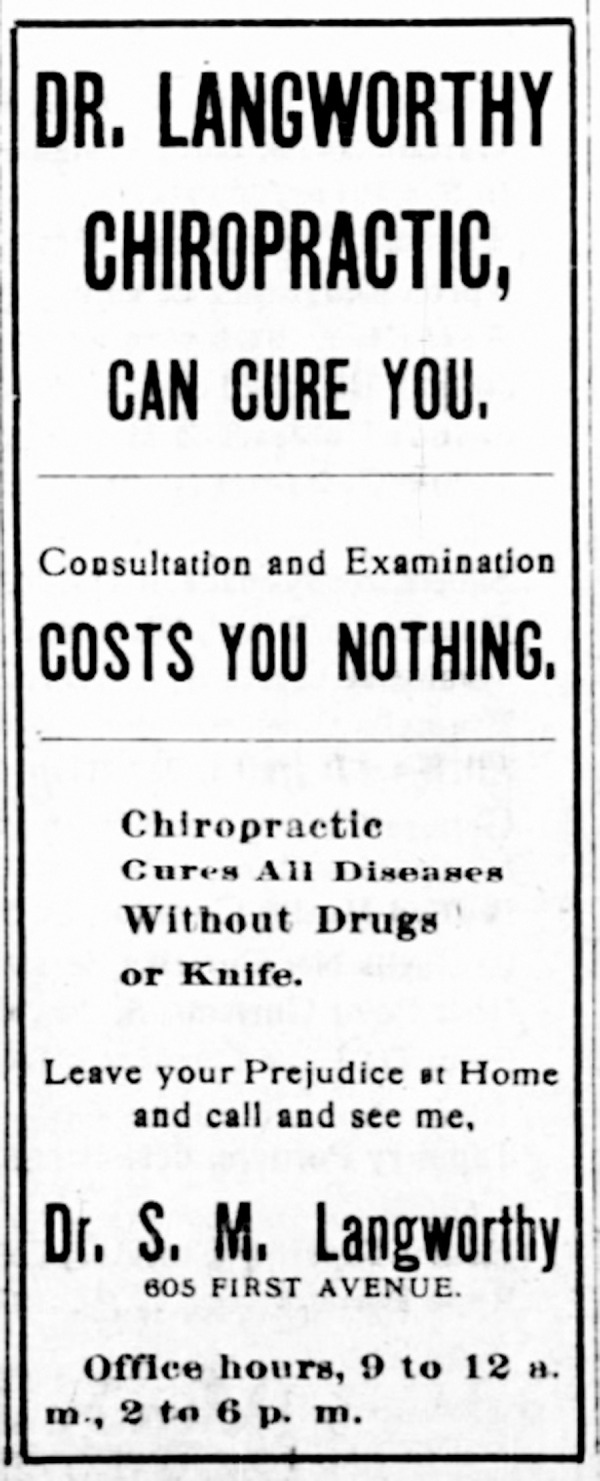

Even though there was a passion for advancing the profession, chiropractic infighting caused sizeable delays in obtaining licensure in some states.90 As an example, DD Palmer was responsible for disrupting the first proposed chiropractic licensing legislation. In 1905, Palmer's nemesis, Dr Solon Langworthy who was one of DD Palmer's early graduates, had proposed a law to the governor of Minnesota that included wording for broad scope chiropractic and a requirement for increased education. DD Palmer argued for a narrower scope and a shorter curriculum. In the end, DD Palmer succeeded in having the chiropractic law vetoed.65,91,92

Chiropractic had to fight in each state to gain legal recognition despite tremendous odds. The AMA had a large membership, excellent legal representation, and extensive financial resources at its disposal to fight legislation. Despite heavily resourced and focused opposition by organized medicine, chiropractic gained legal recognition in 40 states by 193593 and in 46 states by 1961.90 However, the fight for licensure in all states lasted for many more years.

Louisiana was the last state to achieve chiropractic licensure, eventually achieving this in 1974. The last 2 chiropractors in the United States to be sentenced for practicing chiropractic were Dr EJ Nosser and Dr BD Mooring who served time in a Louisiana jail in 1975.94 It is possible that Louisiana was the last state because of the influential leadership of Joseph Sabatier, Jr, MD. Sabatier practiced in Louisiana and his role in Louisiana medical organizations and politics foreshadowed his later involvement with the AMA. He became the chairman of the AMA's Committee on Quackery that in the 1960s organized an effort to further contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession.42 Sabatier would later be named as a defendant in the Wilk v AMA lawsuit.95,96

Basic Science Laws

In addition to licensing laws, chiropractic had to face the basic science laws that were introduced by the AMA.97 Beginning in 1923, the basic science laws required that candidates for licensure in medicine, osteopathy, chiropractic, and naturopathy must pass examinations in preclinical topics common to all health professions, such as chemistry and physiology.93,98 The argument was that if a candidate could successfully complete the basic science examination, he or she would be allowed to take a following examination by a separate professional board to license practitioners in each particular field.90

Some claimed that the basic science laws were an additional attempt by the AMA to keep non-medical practitioners, including chiropractors, from practicing lawfully. The secretary of the Federation of State Medical Boards confirmed this sentiment when he wrote in JAMA in 1948, “The evident original purpose of enacting basic science laws was to exclude chiropractors... from being admitted to licensure.”99 Robert Derbyshire, an expert in medical licensure and medical education and former president of the Federation of State Medical Boards, agreed.100 He wrote,

There was a tendency among chiropractors in the basic science states to feel that they were being persecuted. Many of them correctly thought that the laws were deliberately intended to exclude them from licensure and practice.101

By 1953, basic science laws were enacted in 21 of the states in the United State. It is suggested that the pass rate resulted in a decrease in the number of new chiropractors in those states.90 However, because many chiropractors elected to practice in states without basic science laws to avoid further persecution, it is impossible to draw any conclusions about the number of chiropractors affected by the laws.

Basic science laws continued their restrictive influence until 1980 when they were finally disbanded.63 Some suggest that the examinations elevated educational standards and public safety.65,93 However, others disagreed and suggested “...it is inconceivable that the laws truly contribute to the public health and safety since they require qualified doctors of medicine to negotiate an extra, expensive, time consuming hurdle on the way to licensure in an attempt to exclude a few chiropractors, many of whom can pass the examinations, anyway.”101

Chiropractic Practice

Chiropractic was a distinct profession and chiropractors were independent practitioners who would practice their art and serve the patients in their communities. The AMA did not allow chiropractors to practice within the infrastructure that organized medicine had established. Not only did medical doctors discourage patients from seeing chiropractors; in some cases they were forcibly prevented from doing so. Here is an example from a report posted in the Disabled American Veterans of the World War, Department of California, in 1929:

...here a group of nonmedical men whose work has done wonders for these unfortunates. I refer to chiropractors. There are a great many men who want this kind of treatment and need it. I have been “Behind the bars” as they call it myself, in hospitals. We are given three square meals a day and a place to sleep and you are left there. I know probably fifteen men who have come out of Palo Alto hospital and have gone to chiropractors because they needed that kind of treatment. The medical officers found this out and what was the result? They were forcibly kept in and not allowed to take more treatments. In some cases their clothes were even taken away. That isn't the kind of justice that men like Bill Murphy are working for. I have a service connected disability of the spine. I knew what kind of treatment I needed but the medical officers refused to let me have it.102

Because there was no access through referrals or other means to participate in the medical health care system, such as in hospitals, chiropractors would encourage patients to access chiropractic care in other ways. Chiropractors practiced independently and would post advertisements to let patients know that their services were available.

Regular medical doctors did not believe that health care providers should advertise.103 Although a few medical doctors advertised, advertising and making claims for therapies were contrary to the AMA's code of ethics, which forbade advertising.104 These differing professional viewpoints on advertising fueled the antagonism between chiropractic and medicine. The AMA's Bureau of Investigation included advertising or boasting of one's product in its definition of a “quack.”105 Flexner's report criticized advertising by chiropractors and others: “The chiropractics, the mechano-therapists, and several others are not medical sectarians, though exceedingly desirous of masquerading as such; they are unconscionable quacks, whose printed advertisements are tissues of exaggeration, pretense, and misrepresentation of the most unqualifiedly mercenary character.”61 Thus, the AMA had been labeling chiropractors as quacks since the early 1900s.

However, advertising was a necessity for chiropractors. At the turn of the century, the newly formed chiropractic profession of only several hundred chiropractors competed with more than 110,000 medical doctors, 10,000 homeopaths, and 5000 eclectics for patients.106 BJ Palmer, an early leader of the first chiropractic school, stated that advertising was essential to boost chiropractic (Fig. 4).107

Figure 4.

- BJ Palmer depicted in an advertisement in the local paper The Daily Times (Davenport, Iowa), September 17, 1902. Advertising for chiropractors was essential, whereas for medical physicians, the American Medical Association forbade it.

BJ Palmer built a printing shop at the Palmer School of Chiropractic to produce advertisements, newsletters, books, and other materials.106 As early as 1908, BJ Palmer boasted that the Palmer School printed over 100 different advertising materials that he made available to the Palmer alumni.108

Chiropractic advertising also included direct attacks on organized medicine. BJ Palmer's 1903 advertisement in the Davenport Daily Times condemned medicine and the Iowa Medical Board in the context of defending BJ Palmer's alleged practicing medicine without a license:

Just as long as the people will allow The Medical Board to squeeze the golden eggs out of the Medical Goose by their deceptive manipulation in framing medical laws for the ‘Dear people' and by their misleading, delusive ‘Circular of information,' just so long will this set of poison venders continue the scandalous practice of compelling the people to take their drugs and vaccine poison.109

Similar to other health providers at the time, advertisements seemed to exaggerate the results that patients could expect from treatments. Some chiropractic advertisements included claims that chiropractic adjustments could cure all diseases. An early example of this type of claim was DD Palmer's proclamation of his theory on how to cure cancer through the correction of skeletal misalignments. This appeared 2 years after his discovery of chiropractic in his 1897 advertising publication:110

Having found the cause of cancer, it is an easy thing to relieve the pressure upon the blood vessels and nerves. Arranging the body in a natural condition so that the circulation of blood is free and the pressure is removed from the nerves, the secretion and excretion becomes perfect, and the patient cannot help getting well. In other words, if all the different parts of the machinery of the human body were just right, secretion and excretion would be perfect and all the impurities would be thrown out the back door, instead of finding an outlet elsewhere.110

As well, a 1900 DD Palmer advertisement in The Medical Brief said:

The movements to relieve and adjust those causes are readily understood; e.g., corns and bunions are caused by slipped, luxated, displaced joints, which impinge and press upon the nerves, thereby irritating them, the inflamed enlargements being the surface twig ends of the nerves. Warts on the hand are caused by luxated dorsal vertebra.111

Other chiropractors advertised in a style that was commonly used in this era by those eschewed by the AMA. Solon Langworthy, an early graduate of DD Palmer who opened a competing school of chiropractic in 1904, also advertised that chiropractic could cure (Fig. 5).112

Figure 5.

- An advertisement promising cure from Solon Langworthy in 1901.

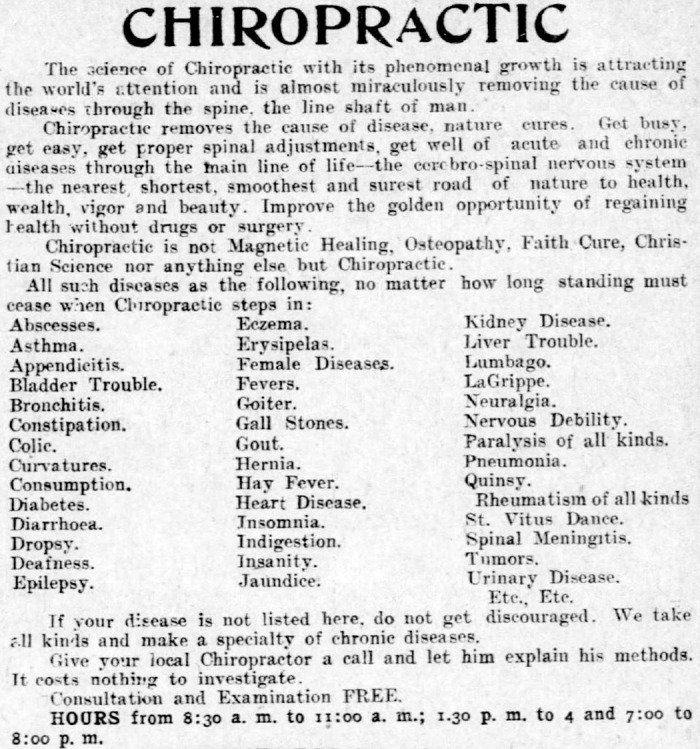

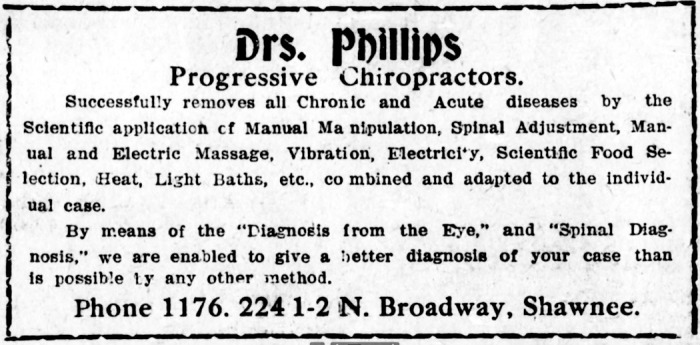

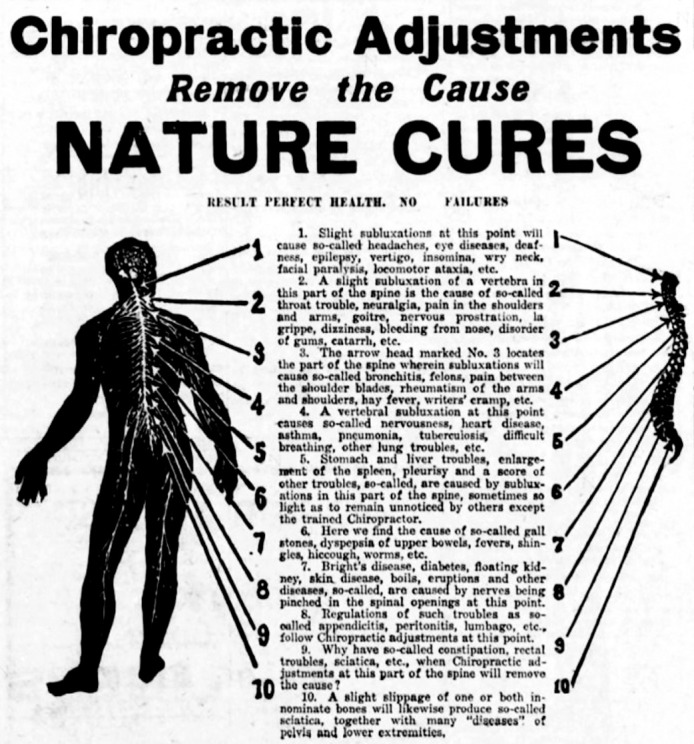

As chiropractors worked to establish chiropractic as a distinct healing profession apart from medicine, they advertised cures for common health disorders that might be typically seen at a medical doctor's office. These included conditions such as the common cold and constipation, as well as diseases that were more serious such as appendicitis, spinal meningitis, pneumonia, and heart disease (Fig. 6).113 Regardless if they had narrow-scope/straight or broad-scope/mixer views, all chiropractors focused on the spine, the nervous system, and the power of the chiropractic adjustment to remove chiropractic vertebral subluxations. And without access to the health care infrastructure offered by organized medicine, all chiropractors (straights and mixers), advertised to entice patients to come in to their offices (Fig. 7).114

Figure 6.

- A chiropractic advertisement from 1911 emphasizing that chiropractic was distinct from other forms of healing. Included was a long list of diseases that typically medical doctors claimed to treat, ranging from abscesses and epilepsy to lumbago and pneumonia.

Figure 7.

- An example of a progressive chiropractor (mixer) offering removal of diseases.

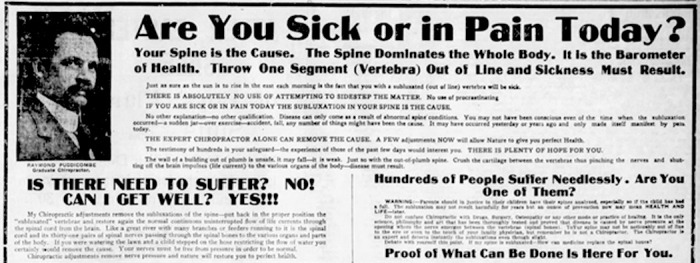

As the chiropractic profession grew, the number and variety of advertisements and claims grew (Fig. 8 and 9).115–117 Some newspaper advertisements included anti-medical messages opposing drugs and surgery. Other advertisements continued to include claims of cure even though rigorous clinical trials were unavailable at that time to support those claims (Fig. 10 and 11).118,119

Figure 8.

- A chiropractic advertisement focusing on the importance of the nervous system in health and suggesting that “Chiropractic adjustments remove nerve pressure and nature will restore you to perfect health.”

Figure 9.

- This chiropractic advertisement includes a diagram depicting that nerves from each level of the spine are associated with tissues, organs, and their associated functions. The advertisement suggests that chiropractic adjustments facilitate the natural healing power within the body.

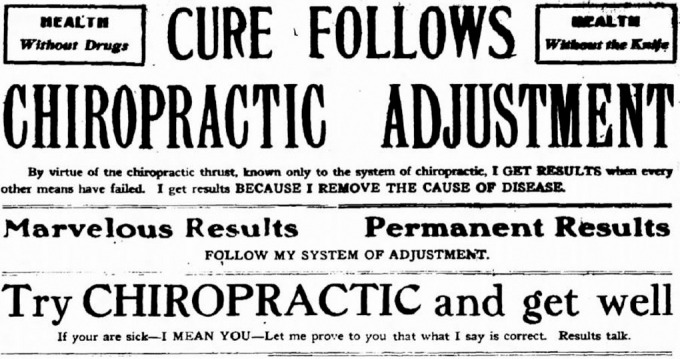

Figure 10.

- A chiropractic advertisement from 1908, pointing out that chiropractic does not use drugs or surgery and suggesting that chiropractic removes the cause of disease.

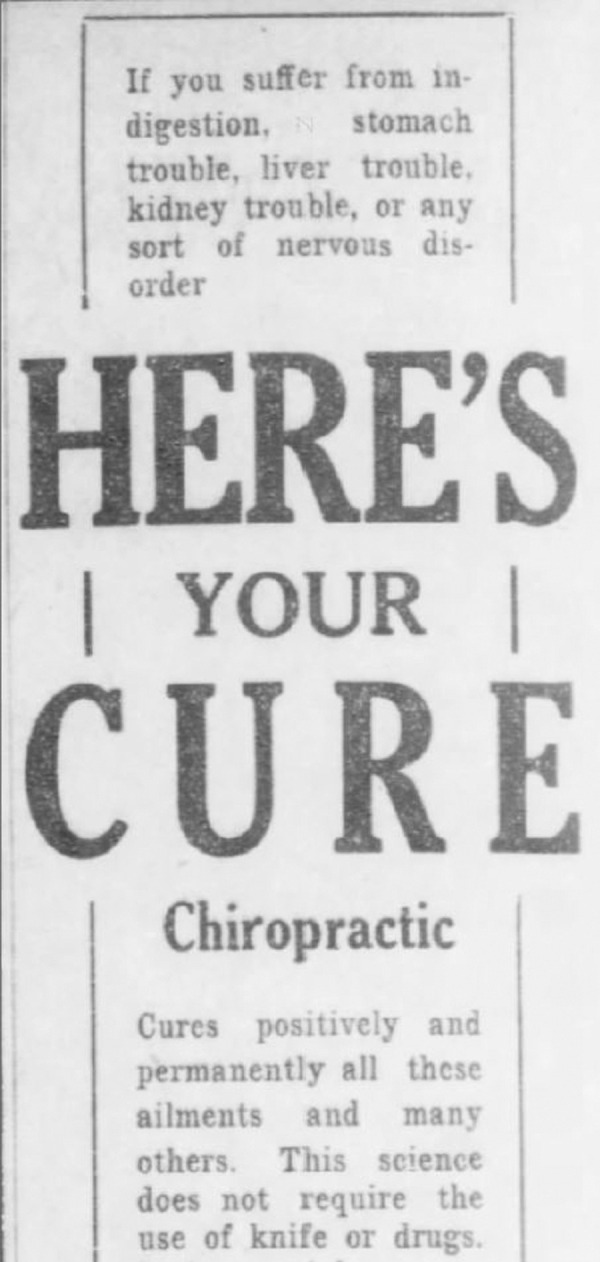

Figure 11.

- A chiropractic advertisement form 1909, pointing out that chiropractic does not use knife (surgery) or drugs and that it can cure “indigestion, stomach trouble, liver trouble, kidney trouble, or any sort of nervous disorder . . . ”.

Over the decades, the AMA gathered advertisements from rival professions and maintained them in their collection. By the 1950s, the AMA had an extensive collection of chiropractic materials and advertisements. These would be included in the AMA's advanced attack on chiropractic and the increased attempt to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession in the 1960s. Many of these would be revealed as evidence during the Wilk v AMA trials.

Chiropractic Education Evolves

Similar to medical education in the mid-1800s, the curricula in the earliest chiropractic schools were several months.120 Curricula were structured similar to trade schools so that graduates possessed the basic knowledge and skills necessary to practice chiropractic.57 DD Palmer's initial chiropractic training program consisted of students watching him care for patients for 3 months for the tuition of $500 (which is approximately $16,000 in 2021). Oakley Smith, one of DD Palmer's earliest graduates and co-founder of one of the earliest broad-scope rival schools, described the training he received from DD Palmer in 1899:121,122

I was taken to Davenport, Iowa, where I took chiropractic treatment for five months. I was convinced of the fact that cures could be made by manipulation. A few days before I was 19 my tuition of $500.00 was paid for a course of instruction in Chiropractic.121

Later on, the students at DD Palmer's institution received 9 months of training.123 The duration of the program, while brief by today's standards, was about the same length as many of the medical schools during the mid-1800s. All chiropractic schools and many medical schools were privately owned and considered a business and, therefore, provided income for the schools' owners.124 The minimal length of education later prompted educational reform efforts in both medical and chiropractic professions.

By 1906, DD Palmer had sold his Davenport school to his son, BJ Palmer, and within 10 years, chiropractic students received basic education in anatomy, physiology, pathology, in addition to the art of diagnosis and chiropractic adjusting technique.123

The growing popularity of chiropractic and the potential business opportunity of training chiropractors resulted in an explosion in the number of chiropractic schools from 1908 through the 1920s.93 By 1920 there were at least 79 chiropractic schools in the United States, as reported by the AMA Council on Medical Education.125 However, this number may be underestimated since more than 390 chiropractic schools have been identified in the United States, with 82 schools present by 1925.126 There was competition to attract students and diverse yet passionate disagreements about chiropractic theory, practice, and education. School leaders and alumni engaged in hostile battles within the profession to set themselves as the preferred school and their rivals as inferior. Chiropractic historian Russell Gibbons said, “Rivalries and intense debate raged, costing many schools support within the profession and further confusion and distrust by the public.”123

At the time when Flexner's report urged for reform in medical education, chiropractors also saw the need for improvements in chiropractic programs. BJ Palmer led early attempts at improving chiropractic educational standards. BJ Palmer campaigned for a minimum of 18 months of instruction and standardization of curricula; however, a number of the school leaders found BJ Palmer's approach overbearing.98 These sentiments were particularly true for the officials of an early broad-scope organization known as the American Chiropractic Association (though having the same name, it is not the same organization as today's American Chiropractic Association). In the 1920s, this group advocated for even higher educational standards than BJ Palmer, the UCA officers, or the schools affiliated with the UCA.77

By the 1940s, a massive transformation of chiropractic education was on the horizon, spearheaded by the broad-scope/mixer organization the National Chiropractic Association (NCA). Changes to chiropractic educational standards were driven by the NCA's desire to achieve federal recognition of chiropractic institutions. They felt that accreditation was needed; otherwise, chiropractic would continue to be attacked by organized medicine, and student enrollments in chiropractic institutions would drop. As a result, chiropractic training programs began to include longer curricula of 4 years, more uniform entrance standards, and the conversion of the schools from for-profit to non-profit institutions.120

John Nugent, DC, was the director of education for the NCA Committee on Education and led a quest to improve chiropractic education in similar fashion as Abraham Flexner had done earlier with medical education.120 Nugent inspected every chiropractic program in the United States and kept records, including ratings and recommendations.127 Among Nugent's goals was the consolidation of the dozens of small proprietary chiropractic schools into larger, financially sound, non-profit colleges and the improvement of chiropractic training programs.120 With each chiropractic school merger, the quality of the curricula, faculty, and facilities improved. By the late 1940s, Nugent had been successful in helping to merge multiple schools in New York and California, thereby strengthening chiropractic.128

Progress toward federal recognition for a chiropractic accrediting agency was not without its problems. Leaders of the Association of Chiropractic Colleges (which is a different organization from today's Association of Chiropractic Colleges) were mainly from chiropractic institutions led by BJ Palmer and were opposed to the reform ideals of the NCA.93 The differences in opinions between the 2 groups about accreditation led to competition between the NCA and the Association of Chiropractic Colleges to achieve recognition by the US Office of Education as the accrediting agency for chiropractic education. When the NCA Committee on Education eventually became the independent Council on Chiropractic Education and submitted an application with the US Office of Education to be listed as the recognized accrediting agency for chiropractic, the Association of Chiropractic Colleges did the same; however, both applications were rejected.129 Eventually after lengthy negotiations, the Council on Chiropractic Education filed an appeal to the US Office of Education and was approved as the single recognized accrediting agency for chiropractic education in 1974.93,129 After 80 years and much infighting, the chiropractic profession ultimately had a federally recognized accrediting body, which meant that chiropractic students were finally eligible for federal student loans.130

Over time, the chiropractic profession established its own qualifying examinations pertinent to the basic sciences. The National Board of Chiropractic Examiners was created in 1963 and became the body that administers a qualifying examination.65,93 This examination also became the licensing examination for many states.131 The results are among the criteria used by state licensing agencies to determine if a chiropractor has satisfied that particular state's minimum qualifications for licensure.132 This helped to fortify the chiropractic profession against the AMA's basic science laws.

Chiropractic educational programs improved despite the lack of federal funding.133 As mentioned by Gibbons, “... in a time when virtually every other aspect of public health training is subsidized by the government, the profession has achieved this without any federal or taxpayer assistance.”123 With the Council on Chiropractic Education's recognition by the US Office of Education, further improvements in chiropractic education were pending, as chiropractic training programs would be required to meet the accreditation requirements. As the profession moved into the late 1970s, chiropractic education had been transformed from its humble origins in DD Palmer's office 80 years earlier.

Chiropractic Research and Science in the Early Years

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, chiropractic science was guided by its preliminary theories. Chiropractors' early attempts to perform scientific observations were supported by the plausible theory and the philosophy of the profession that health comes from within the human body and is influenced or controlled primarily by the nervous system.66 Early chiropractic investigators used descriptions of the human organism, particularly including the nerves, bones, and articulations, to more fully understand its form and function.66 DD Palmer wrote, “Science is knowledge reduced to law and embodied in a system . . . Science is accepted, accumulated knowledge, systematized and formulated . . . ”134 Chiropractors reasoned that chiropractic was scientifically based on deductions from principles of anatomy or physiology and supported by reported improvements in patient symptoms or satisfaction.24 This was an alternative that “represented a coherent vision of science that overlapped with, yet fundamentally differed from, scientific medicine.”135 As medicine advanced and widely publicized its contemporary experimental scientific approaches, chiropractic continued with its systematic organization and observations of human form and function as its science.135

For many years, chiropractic leaders did not have the resources or ability to change their perspectives on science, and there were few voices within the profession advocating for change.24 The fights for licensure, efforts to keep chiropractors out of jail, and the critical upgrades in chiropractic education, also drained the profession of resources that might have been used to advance the science of chiropractic.

While chiropractic was under attack by organized medicine and battled to gain licensure,136 it was impossible for chiropractors to gain admittance to major universities. This reduced chiropractors' access to vital resources that were needed to further develop the science of chiropractic.137,138 Thus, chiropractic was hindered from entering a growth period of science in the early 1900s, when it could have attempted to investigate a wide array of problems, as did medicine and other health care professions.138

With chiropractors being forbidden to work within the medical health care infrastructure, there were no opportunities to attend scientific meetings, little funding for research projects, and infrequent scholarly activities. This resulted in a void in published research for the chiropractic profession for many decades. This would be an argument that the AMA propaganda would continue to use against chiropractic. In other words, organized medicine did not allow chiropractors to participate, then criticized them for not participating.

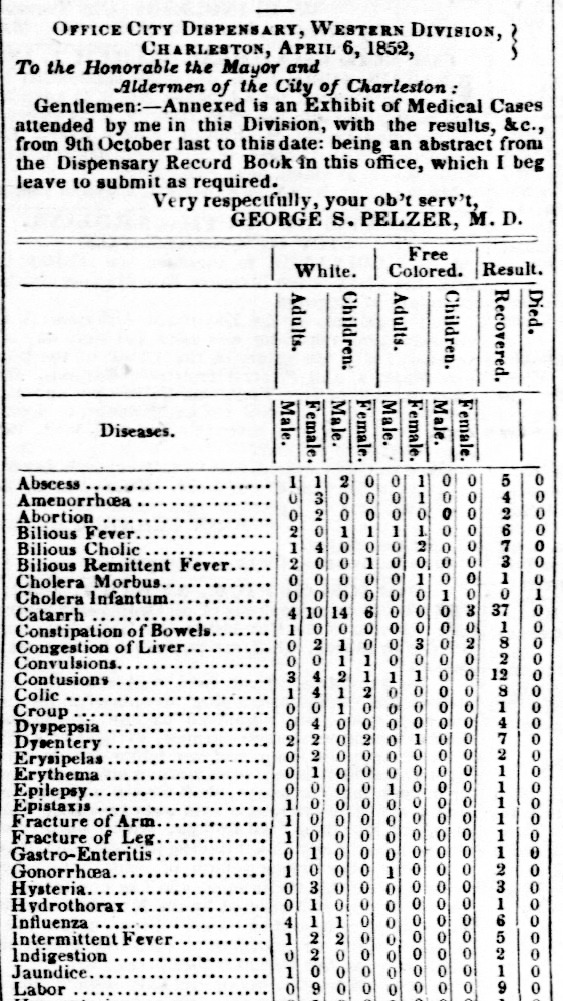

In the early 1900s, chiropractors suggested that when chiropractic patients showed positive responses, this was evidence enough to demonstrate the effectiveness of chiropractic care despite limitations to these observations.135 Chiropractic Statistics, a 1925 booklet, listed an array of outcomes for a multitude of conditions treated by chiropractors. Impressive in its alleged scope, the authors claimed 99,976 cases from 412 chiropractors for 110 conditions. The methodology employed to conduct this study seems similar to those used by medicine many decades earlier when reporting cases publicly (Fig. 12).139 Unfortunately, the methods in the publication were not included and the data were terse, summarized in categories of “recovered or greatly improved”; “unchanged”; or “died,” so the exact methods are unknown.24

Figure 12.

- A portion of a notice in a newspaper. In this report, the medical doctor provides a long list of conditions and the associated the number of people who recovered or died. This reporting style is similar to that used by chiropractors decades later by noting patients who recovered after using chiropractic care.

These data, and their variations, were reprinted for decades in marketing books,140 journal articles,24 and charts141 and touted as evidence for the scientific validity and effectiveness of chiropractic theory and practice (Fig. 13).140 Of particular interest is the “Chiropractic Research Chart” that appears to have been a reorganization of some of the 1925 Chiropractic Statistics data. The data on this research chart did not change between 1967141 and 1979, thereby implying there was little advancement in this area.142 Years later in the Wilk v AMA lawsuit, the AMA's defense lawyer used these old advertisements to criticize chiropractic. He argued that chiropractors did not understand science and that they advertised to help conditions for which they were not trained to diagnose or treat.95

Figure 13.

- The publication What Chiropractic is Doing (1938) was used to promote chiropractic. The cover emphasizes chiropractic as a modern health science “without the use of drugs or needless surgery.”

Medical science had developed into its golden age by the 1950s and 1960s.143 However, due to the social and political constraints during that time, a formal approach to research for chiropractic had not yet begun.135 While the delay may have been due to many factors inside and outside of the profession, it is not surprising that there was little science to demonstrate the effects of chiropractic for nearly half of the first 100 years of its existence. However, demands for a more mature science of chiropractic were growing within the profession. An International Chiropractors Association (ICA) official suggested that the profession should define itself using scientific terms, rather than by scope of practice, philosophy, or art. He wrote,

Definitions orientating chiropractors themselves toward a scientific approach would help the profession attain public and scientific acceptance as a science and specialty. …to define Chiropractic in terms of what it does or believes today, 50 years ago, or 50 years from now, would of necessity place it in some category other than that of science. At worst it would be a cult, which many legitimate scientists today consider it...144

With an increased recognition that chiropractic needed to embrace a more current scientific approach, chiropractors were eventually poised to enter a period of research that set the stage for later acceptance by the government, the public, and major research centers for funding in the 1970s and 1980s. However, any substantial advancement to chiropractic research and science would not be possible until the final judgment of the Wilk v AMA lawsuit.

DISCUSSION

The AMA rose to dominate health care in the United States and within this social context, the chiropractic profession fought to survive in the first half of the 20th century. The health care environment changed substantially when chiropractic was emerging.

Medicine was just beginning to establish its dominance at the turn of the century. The first half of the 20th century witnessed the AMA's rise in power, which was facilitated by amassing membership and resources, whereas chiropractic in its embryonic stage faced legal persecution and infighting combined with attempts by chiropractic leaders to define chiropractic. The AMA's strategic gathering of information about other professions persisted, which helped organized medicine limit or eliminate others thus becoming the dominant health profession.

Flexner's 1910 report, which was stimulated and supported by the AMA, sparked a massive change in medical education. Eventually the elimination of what the AMA saw as substandard medical colleges reduced the number of medical institutions as well as programs of other health professions, which resulted in the AMA gaining even more power.

Chiropractic degree programs were established during this challenging time. Perhaps due to grit and persistence, even without the infrastructure and resources that organized medicine possessed, chiropractic continued to advance.

Chiropractors fought to obtain licensure and defend their ability to practice. Although chiropractic made progress from 1910 to 1920, in the 1920s, there was a surge. With the public's support, legislation would be passed in some areas, despite medical efforts to quash the legalization of chiropractic. By the time medicine perceived chiropractic as a substantive threat, the number of states that legally recognized chiropractors had grown considerably. Not willing to give up, organized medicine continued to fight against legislation and for allowing chiropractic boards.

Attacks on the chiropractic profession seemed to strengthen the determination of chiropractors to persist. Some who were jailed would succumb to arrest repeatedly instead of giving up their chiropractic practice. Patients would support their chiropractors and many patients would fight on the side of chiropractic to help them gain licensure so that they would be allowed to practice legally. Chiropractors would become martyrs by going to jail over the many decades it would take to finally obtain recognition in all of the United States.

Chiropractic terminology was an essential part of chiropractic identity and was successfully used to defend chiropractors during lawsuits throughout the early and mid-20th century. Thus, since it protected chiropractic identity, secured licensure, and allowed chiropractors to practice, it is no surprise that the unique vocabulary has been entrenched within the culture of chiropractic. By having a separate and distinct set of words, such as adjustment (chiropractic) vs manipulation (medicine) or vertebral subluxation (chiropractic) vs spinal joint dysfunction (osteopathy), it would also create confusion or criticism of chiropractic by the public and health care providers over the following decades. These facts may help to explain why there is some confusion or angst regarding differences in vocabulary.

It could be argued that since chiropractic is legally recognized in all fifty United States and territories in the present day, the need to distinguish the chiropractic vernacular from others is no longer necessary. However, others may argue that these unique terms are still necessary to preserve professional identity. Giving up professional identity might be seen as being absorbed into organized medicine, and therefore would in essence eliminate the chiropractic profession. Nonetheless, terminology played an important historical role for chiropractors as they fought for licensure and in legal defense and to establish a place in the health care marketplace.

A criticism of chiropractic that was raised during the Wilk v AMA lawsuit was that there were inconsistencies of chiropractic practice from state to state. The differences in practice and scope confuses health care providers and the public. However, there is a reason for this. Chiropractors had to battle against state and national medical and osteopathic associations for licensure 1 state at a time over decades. The differences in scope of practice were inevitable because of changes in available evidence, social norms, and other factors. Adding the external attacks from the AMA and the internal discord within the chiropractic, it is actually surprising how similar practice scopes are today.145

As chiropractic continued to advance, the AMA saw that they were losing control over preventing legalization for chiropractic. As a result, the AMA created a series of tests (basic science laws) in the hopes that chiropractors would not be able to pass these exams, thereby aiming to keep chiropractors from practicing. However, these efforts eventually failed, in that chiropractic schools responded by expanding their programs to include the additional information so that their graduates would be able to pass the tests.

Another issue raised during the Wilk v AMA lawsuit was the criticism of the science of chiropractic.146,147 Chiropractors considered science as a body of evidence, whereas medicine later promoted the experimental qualities of science. 24 Science has always been recognized as an important component of chiropractic, but science was defined by chiropractors in a more classical way. As Keating et al stated,

However, it does justice neither to chiropractic nor to the history of health care to dismiss all claims to scientific status by early DCs as mere marketing ploys. Early chiropractors' methods often compared favorably to the lingering ‘heroic' medical practices of the previous century. Drugless healers often seemed more rational if only for the lesser risks to patients, and rationality was sometimes considered synonymous with science.24

Medicine had the resources and infrastructure to enact experimental research and most of these methods fit perfectly or were constructed around pharmacological therapeutics (drugs). Chiropractic was rejected by organized medicine and considered a separate and distinct profession apart from medicine. Therefore, chiropractors were not given access to the resources needed to conduct experimental research, such as universities, hospitals, and trained staff (eg, statisticians). Despite the hostile environment that was created by the dominant AMA, chiropractic continued to survive and grow.

Because the AMA considered chiropractors irregular practitioners, those in the medical infrastructure did not allow chiropractors to work in medical hospitals, to access resources from the medical establishment, or to accept or give referrals to medical practitioners. Therefore, advertisements were a necessity for early chiropractors to establish themselves and the chiropractic profession. Some of the early advertising efforts were exuberant and over-reaching with their claims but were consistent with other health care advertising at that time.

The AMA collected and stored advertising and other materials from chiropractic and other professions for decades. These materials would later be used as propaganda against chiropractic and would also be used during the Wilk v AMA trials to claim that chiropractors were practicing outside of their abilities, and to claim that what chiropractors did was unfounded in science.

However, interestingly at the time of the lawsuit, there was little experimental evidence about what chiropractic could or could not do. Since the AMA refused to acknowledge chiropractic, let alone study its effects, there was no evidence against chiropractic either. Chiropractic schools did not have the resources necessary to do extensive research, thus many research questions were left unanswered. Nonetheless, medicine would continue to claim that there was no evidence to support chiropractic and would claim that chiropractic was harmful when the real issue was that chiropractic effectiveness and safety had not yet been studied adequately.

The AMA gained strength in member numbers and created an infrastructure by which the US government relied heavily upon the AMA for health information, advice, and action/support. The AMA was intimately involved in most health-related activities. This included everything from the hospital system to public health efforts. Medical doctors relied on the AMA as the gatekeeper to hospital privileges and practice. By the 1950s, medicine was considered the only viable primary health profession other than those (eg, nursing, physical therapy) that survived in their roles subservient to medicine.48,53,54

This environment left little room for other health models or other health care professions to exist within the US healthcare system. Organized medicine marginalized the other professions, keeping medicine at the center of the health care model. The AMA made various attempts over decades to try to control or eliminate the practice of chiropractic and, as each decade passed, AMA efforts to eliminate chiropractic seemed to intensify.55

Leaders within the chiropractic profession responded as much as they were able to the pressures and threats for professional territory. Attacks from organized medicine likely influenced the direction and growth of the chiropractic profession since these efforts redirected or depleted the limited resources that the chiropractic profession possessed. With most of the resources focused on defense and chiropractors not allowed to collaborate with resource-rich environments such as medical universities or hospitals, it was difficult for the chiropractic profession to grow very much in education or research. Without a sustainable infrastructure and access to funding for education programs or research, the negative cycle continued. The chiropractic profession likely would be more developed today had it not been for these continued pressures and limitations imposed by external forces. The resulting weakened educational and research base would be used in arguments by defense lawyers during the Wilk v AMA lawsuit to claim that chiropractic was a risk to the health of the public, even though the AMA lawyers had no scientific evidence to support their statements.

Limitations

This historical narrative reviews events from the context of the chiropractic profession and the viewpoints are limited by the authors' framework and worldview. Other interpretations of historic events may be perceived differently by other authors. The context of this paper must be considered in light of the authors' biases as licensed chiropractic practitioners, educators, and scientific researchers.

The primary sources of information were written testimony, oral interviews, public records, legal documents, minutes of meetings, newspapers, letters, and other artifacts. These formed the basis for our narrative and timeline. We acknowledge that recall bias is an issue when referencing sources, such as letters, where people recount past events. Secondary sources, such as textbooks, trade magazines, and peer-reviewed journal articles, were used to verify and support the narrative. We collected thousands of documents and reconstructed the events relating to the Wilk v AMA lawsuit. Since no electronic databases exist that index many of the publications needed for this research, we conducted page-by-page hand searches of decades of publications. While it is possible that we missed some important details, great care was taken to review every page systematically for information. It is possible that we missed some sources of information and that some details of the trials and surrounding events were lost in time. The aforementioned potential limitations may have affected our interpretation of the history of these events.

Some of our sources were interviews, manuscripts, or letters where the author recalled past events. Recall bias is an issue when referencing interview sources. Surviving documents from the first 80 years of the chiropractic profession, the years leading up to the about the Wilk v AMA lawsuit, are scarce. Chiropractic literature existing before the 1990s is difficult to find since most of it was not indexed. Many libraries have divested their holdings of older material, making the acquisition of early chiropractic documents challenging. While we were able to obtain some sources from libraries, we also relied heavily upon material from our own collection and materials from colleagues. Thus, there may be relevant papers or artifacts that were inadvertently missed. Our interpretation of the events related to the trials is limited to the materials available. The information regarding this history is immense and due to space limitations, not all parts of the story could be included in this series.

CONCLUSION

In the first part of the 20th century, the AMA amassed power as chiropractic was just emerging as a profession. Events such as the publication of Flexner's report and development of the medical basic science laws helped to entrench the AMA's monopoly on health care. Chiropractic was outside of the medical infrastructure and growth was stifled due to increasing attacks from organized medicine. This environment shaped how chiropractic grew as a profession. These events added to the tensions between the professions that ultimately resulted in the Wilk v AMA lawsuit.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the following people for their detailed reviews and feedback during development of this project: Ms Mariah Branson, Dr Alana Callender, Dr Cindy Chapman, Dr Gerry Clum, Dr Scott Haldeman, Mr Bryan Harding, Mr Patrick McNerney, Dr Louis Sportelli, Mr Glenn Ritchie, Dr Eric Russell, Dr Randy Tripp, Mr Mike Whitmer, Dr James Winterstein, Dr Wayne Wolfson, and Dr Kenneth Young.

FUNDING AND CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

This project was funded and copyright owned by NCMIC. The views expressed in this article are only those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the NCMIC, National University of Health Sciences, or Association of Chiropractic Colleges. BNG is the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Chiropractic Education and CDJ is on the NCMIC board and the editorial board of the Journal of Chiropractic Education. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Troyanovich S, Troyanovich J. Reflections on the birth date of chiropractic. Chiropr Hist. 2013;33(2):20–32. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson CD. Chiropractic Day: a historical review of a day worth celebrating. J Chiropr Humanit. 2020;27:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.echu.2020.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilk v AMA No 872672 and 872777 (F 2d 352 Court of Appeals 7th Circuit April 25. 1990).

- 4.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 1: origins of the conflict. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):9–24. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haldeman S, Chapman-Smith D, Petersen DM. Guidelines for Chiropractic Quality Assurance and Practice Parameters proceedings of the Mercy Center Consensus Conference. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishing; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson C. What is the Association of Chiropractic Colleges Educational Conference and Research Agenda Conference? J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30(4):249–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson C, Green B. The Association of Chiropractic Colleges Educational Conference and Research Agenda Conference: 17 years of scholarship and collaboration. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33(3):165–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mootz RD, Hansen DT, Breen A, Killinger LZ, Nelson C. Health services research related to chiropractic: review and recommendations for research prioritization by the chiropractic profession. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(9):707–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haas M, Bronfort G, Evans RL. Chiropractic clinical research: progress and recommendations. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(9):695–706. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mrozek JP, Till H, Taylor-Vaisey AL, Wickes D. Research in chiropractic education: an update. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(9):762–773. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cramer G, Budgell B, Henderson C, Khalsa P, Pickar J. Basic science research related to chiropractic spinal adjusting: the state of the art and recommendations revisited. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(9):726–761. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bigos SJ, Bowyer OR, Braen GR, et al. Acute low back problems in adults. Acute Lower Back Problems in Adults. Clinical Practice Guidelines No. 14. AHCPR Publication No. 95-0642 Rockville, Md.: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1994.

- 13.Haldeman S, Carroll L, Cassidy JD, Schubert J, Nygren A. The Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders: executive summary. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(2 Suppl):S7–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson C, Baird R, Dougherty PE, et al. Chiropractic and public health: current state and future vision. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(6):397–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson C, Green BN. Public health, wellness, prevention, and health promotion: considering the role of chiropractic and determinants of health. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(6):405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egan J, Baird R, Killinger L. Chiropractic within the American Public Health Association, 1984–2005: pariah, to participant, to parity. Chiropr Hist. 2006;26:97–117. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haldeman S, Nordin M, Chou R, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: World Spine Care executive summary on reducing spine-related disability in low- and middle-income communities. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(Suppl 6):776–785. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5722-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green BN, Johnson CD, Haldeman S, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: public health and prevention interventions for common spine disorders in low- and middle-income communities. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(Suppl 6):838–850. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5635-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson CD, Haldeman S, Nordin M, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: methodology, contributors, and disclosures. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):786–795. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5723-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haldeman S, Johnson CD, Chou R, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: care pathway for people with spine-related concerns. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):901–914. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5721-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haldeman S, Johnson CD, Chou R, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: classification system for spine-related concerns. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):889–900. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5724-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson CD, Haldeman S, Chou R, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: model of care and implementation. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):925–945. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5720-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green BN, Johnson CD, Haldeman S, et al. A scoping review of biopsychosocial risk factors and co-morbidities for common spinal disorders. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0197987. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keating JC, Jr, Green BN, Johnson CD. “Research” and “science” in the first half of the chiropractic century. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1995;18(6):357–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boon H, Verhoef M, O'Hara D, Findlay B, Majid N. Integrative healthcare: arriving at a working definition. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004;10(5):48–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawk C, Nyiendo J, Lawrence D, Killinger L. The role of chiropractors in the delivery of interdisciplinary health care in rural areas. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1996;19(2):82–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lott CM. Integration of chiropractic in the Armed Forces health care system. Mil Med. 1996;161(12):755–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Branson RA. Hospital-based chiropractic integration within a large private hospital system in Minnesota: a 10-year example. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):740–748. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green BN, Johnson CD, Lisi AJ, Tucker J. Chiropractic practice in military and veterans health care: the state of the literature. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2009;53(3):194–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boon HS, Mior SA, Barnsley J, Ashbury FD, Haig R. The difference between integration and collaboration in patient care: results from key informant interviews working in multiprofessional health care teams. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunn AS, Green BN, Gilford S. An analysis of the integration of chiropractic services within the United States military and veterans' health care systems. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):749–757. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldberg CK, Green B, Moore J, et al. Integrated musculoskeletal rehabilitation care at a comprehensive combat and complex casualty care program. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):781–791. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lisi AJ, Goertz C, Lawrence DJ, Satyanarayana P. Characteristics of Veterans Health Administration chiropractors and chiropractic clinics. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46(8):997–1002. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2009.01.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hawk C. Integration of chiropractic into the public health system in the new millennium. In: Haneline MT, Meeker WC, editors. Introduction to Public Health for Chiropractors. Boston: Jones and Bartlett; 2010. pp. 375–389. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Green BN, Johnson CD, Daniels CJ, Napuli JG, Gliedt JA, Paris DJ. Integration of chiropractic services in military and veteran health care facilities: a systematic review of the literature. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2016;21(2):115–130. doi: 10.1177/2156587215621461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salsbury SA, Goertz CM, Twist EJ, Lisi AJ. Integration of doctors of chiropractic into private sector health care facilities in the United States: a descriptive survey. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018;41(2):149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Green BN, Johnson CD. Interprofessional collaboration in research, education, and clinical practice: working together for a better future. J Chiropr Educ. 2015;29(1):1–10. doi: 10.7899/JCE-14-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson C. Health care transitions: a review of integrated, integrative, and integration concepts. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):703–713. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirschheim R, Klein HK. Four paradigms of information systems development. Communications of the ACM. 1989;32(10):1199–1216. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Porra J, Hirschheim R, Parks MS. The historical research method and information systems research. J Assoc Info Syst. 2014;15(9):3. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lune H, Berg BL. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. Harlow, UK: Pearson; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 4: Committee on Quackery. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):55–73. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 5: Evidence exposed. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):74–84. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 6: Preparing for the lawsuit. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):85–96. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession Part 7: Lawsuit and decisions. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;2021(S1):97–116. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-28. https://doi.org/10.7899/JCE-21-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 8: Judgment impact. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):117–131. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-29. https://doi.org/10.7899/JCE-21-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 3: Chiropractic growth. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):45–54. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-24. https://doi.org/10.7899/JCE-21-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ameringer CF. The Health Care Revolution From Medical Monopoly to Market Competition Vol 19. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]