Abstract

Objective

This is the seventh paper in a series that explores the historical events surrounding the Wilk v American Medical Association (AMA) lawsuit in which the plaintiffs argued that the AMA, the American Hospital Association, and other medical specialty societies violated antitrust law by restraining chiropractors' business practices. The purpose of this paper is to provide a summary of the lawsuit that was first filed in 1976 and concluded with the final denial of appeal in 1990.

Methods

This historical research study used a phenomenological approach to qualitative inquiry into the conflict between regular medicine and chiropractic and the events before, during, and after a legal dispute at the time of modernization of the chiropractic profession. Our methods included obtaining primary and secondary data sources. The final narrative recount was developed into 8 papers following a successive time line. This paper, the seventh of the series, considers the information of the 2 trials and the judge's decision.

Results

By the time the first trial began in 1980, the AMA had already changed its anti-chiropractic stance to allow medical doctors to associate with chiropractors if they wished. In the first trial, the chiropractors were not able to overcome the very stigma that organized medicine worked so hard to create over many decades, which resulted in the jury voting in favor of the AMA and other defendants. The plaintiffs, Drs Patricia Arthur, James Bryden, Michael Pedigo, and Chester Wilk, continued with their pursuit of justice. Their lawyer, Mr George McAndrews, fought for an appeal and was allowed a second trial. The second trial was a bench trial in which Judge Susan Getzendanner declared her final judgment that “the American Medical Association (AMA) and its members participated in a conspiracy against chiropractors in violation of the nation's antitrust laws.” After the AMA's appeal was denied by the Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit in 1990, the decision was declared permanent. The injunction that was ordered by the judge was published in the January 1, 1988, issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Conclusion

The efforts by Mr McAndrews and his legal team and the persistence of the plaintiffs and countless others in the chiropractic profession concluded in Judge Getzendanner's decision, which prevented the AMA from rebuilding barriers or developing another boycott. The chiropractic profession was ready to move into its next century.

Keywords: Health Occupations; Chiropractic; Medicine; Humanities; History, 20th Century; Antitrust Laws

INTRODUCTION

The forces that created the hostile environment for chiropractic in the health care system and American culture began in 1847, at the very start of the American Medical Association (AMA). The impact of the AMA's actions to establish a monopoly of health care by controlling or eliminating its competition was observed by the successful elimination or absorption of other health professions.1,2 Many decades of tireless efforts from political organized medicine resulted in the AMA's views becoming inculcated in American thought and culture and its dominance in health care.3,4

The AMA had already fought many lawsuits and had the resources that were required to survive legal ordeals, including antitrust suits. The AMA's legal defense team was confident, knowing that one of their previous strategies to win lawsuits was to simply outlast the opponent by using their extensive resources. However, with the Wilk v AMA lawsuit,5 the AMA lawyers likely did not realize that they would be facing a battle that would not end in their favor. The core argument in the lawsuit by the chiropractic plaintiffs' lawyers against the medical defendants was based on antitrust law, a law that prohibits agreements in restraint of trade and the abuse of monopoly power.6 The grit of the plaintiffs and the tenacity and strategy of their lawyers would result in a pivotal event for the entire chiropractic profession.

The historical events surrounding this lawsuit are important for chiropractors today because they help explain the surge in scientific growth7–26 and the improvement in access to chiropractic care for patients once barriers were removed.27–40 These events clarify chiropractic's previous struggles and how past experiences may influence current events. The obstacles and challenges that chiropractic overcame may help explain the current culture and to identify issues that the chiropractic profession may need to address into the future.

The purpose of this paper is to provide a summary of the lawsuit that was first filed in 1976 and concluded with the final denial of the AMA's appeal in 1990. This paper provides a brief overview of antitrust law and a summary of the trials and their eventual outcomes.

METHODS

This historical study used a phenomenological approach to qualitative inquiry into the conflict between regular (orthodox) medicine and chiropractic and the events before, during, and after a legal dispute at the time of modernization of the chiropractic profession. The metatheoretical assumption that guided our research was a neohumanistic paradigm. As described by Hirschheim and Klein, “The neohumanist paradigm seeks radical change, emancipation, and potentiality, and stresses the role that different social and organizational forces play in understanding change. It focuses on all forms of barriers to emancipation—in particular, ideology (distorted communication), power, and psychological compulsions and social constraints—and seeks ways to overcome them.”41 We used a pragmatic and postmodernist approach to guide our research practices such that objective reality may be grounded in historical context and personal experiences and interpretation may evolve with changing perspectives.42

We followed techniques described by Lune and Berg.43 These steps included identifying the topic area, conducting a background literature review, and refining the research idea. Following this, we identified data sources and evaluated the source materials for accuracy. Our methods included obtaining primary data sources: written testimony, oral interviews, public records, legal documents, minutes of meetings, newspapers, letters, and other artifacts. Information was obtained from publicly available collections on the Internet, university archives, and privately owned collections. Secondary sources included scholarly materials from textbooks and journal articles. The materials were reviewed, and then we developed a narrative recount of our findings.

The manuscript was reviewed for accuracy, completeness, and content validity by a diverse panel of experts, which included reviewers from various perspectives within the chiropractic profession ranging from broad-scope (mixer) to narrow-scope (straight) viewpoints, chiropractic historians, faculty and administrators from chiropractic degree programs, corporate leaders, participants who delivered testimony in the trials, and laypeople who are chiropractic patients. The manuscript was revised based on the reviewers' feedback and returned for additional rounds of review. The final narrative recount was developed into 8 papers that follow a chronological story line.1–4,44–46 This paper is the seventh of the series that considered events relating to the lawsuit and provides a summary of the trials.

RESULTS

Before the Trials

The plaintiffs were 4 chiropractors who in 1976 put forth a lawsuit not only against the AMA, which would have been formidable on its own, but other organizations, namely, American Hospital Association (AHA), American College of Surgeons (ACS), American College of Physicians (ACP), Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals (JCAH), American College of Radiology (ACR), American Osteopathic Association (AOA), American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (AAPMR), Illinois State Medical Society (ISMS), Chicago Medical Society CMS), Medical Society of Cook County (MSCC), and AMA officers or employees (H. Doyl Taylor, Joseph A. Sabatier Jr, H. Thomas Ballantine, and James H. Sammons). Thus, it appeared as if they were taking on the entire medical establishment in the United States.

Since its filing, more than 4 years had passed by the time the first trial of the Wilk v AMA lawsuit began. During that time, the AMA's leadership made changes to the association's policies and proposed modifying the AMA Principles of Medical Ethics.47

An AMA Board of Trustee member summarized the situation regarding section 3 of the 1957 Principles that was hampering the AMA's defense position in chiropractic lawsuits. He stated, “If we should lose these suits, the damages requested could bankrupt this Association.” He continued, “The Board of Trustees has a fiduciary responsibility to protect the assets of our membership. Legal counsel tells us that we need to change the principles.”47

In 1980, the year that the suit went to trial, the AMA revised its principles. This revision “occurred in the milieu of legal actions ultimately adverse to the AMA, with judgments that its policies and acts in excluding associations between physicians and chiropractors constituted anticompetitive behavior.”48 The AMA's Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs recommended new sections for the 1980 version. These included the following:

V. A physician shall continue to study, apply and advance scientific knowledge, make relevant information available to patients, colleagues, and the public, obtain consultation, and use the talents of other health professionals when indicated.

VI. A physician shall, in the provision of appropriate patient care, except in emergencies, be free to choose whom to serve, with whom to associate, and the environment in which to provide medical services.49

Although these modifications did not name chiropractic specifically, the changes provided medical physicians with the ability to choose what health care providers they wanted to work with. However, the AMA took no assertive actions to clarify to the members of the medical profession, the other health care associations under its influence, or the American public that these changes took place. The United States was still very much under the influence of many previous decades of AMA propaganda against chiropractic.

The First Trial Begins

Antitrust Concepts

Antitrust legal issues are complex.50,51 The cases are often decided through lengthy arguments by counsel with specialization in antitrust law. As one author said, “Much of the Sherman Act's doctrinal chaos is attributable to judicial and scholarly fondness for impossibly broad statements of the per se rule.”52

The Sherman Act of 1890 was the first antitrust act in the United States.53 Section 1 of the Sherman Act states, “Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is declared to be illegal.”49 Thus, it prohibits anticompetitive agreements and conduct that would attempt to control (monopolize) a given market, which would mean that those activities would be considered illegal. However, the Sherman Act is “not to protect businesses from the working of the market; it is to protect the public from the failure of the market. The law directs itself not against conduct which is competitive, even severely so, but against conduct which unfairly tends to destroy competition itself.”54

Prior to the Sherman Act, some industries were controlled by a few businessmen and companies. This created, in part, a disparity between those who were poor and those who were wealthy.55 The Sherman Antitrust Act was an attempt to protect consumers from being harmed by unfair business practices.

The Sherman Act was originally applied to business and industry. For decades, the learned professions (ie, law, medicine, and theology) were considered exempt from antitrust law. At the time of the Wilk v AMA lawsuit, it was not clear if the Sherman Act applied to learned professions, especially the health professions, including medicine. Leaders of health profession associations argued that their activities protected their professions and could not be perceived as if they were creating a monopoly. They stated that to protect their profession was in the public's best interest since only the most qualified health care professional should render services that would impact the safety and well-being of individuals.

During this time, judges ruled that learned professions were not exempt from antitrust law. The most quoted case to support this view is that of Goldfarb, a lawyer who sued the Virginia State Bar Association for price-fixing, which is an antitrust issue.56 Goldfarb won the case in 1975, and this established precedence that the learned professions were not exempt from antitrust law.57 Following this in 1982, the State of Arizona sued the Maricopa County Medical Society for price-fixing. This case demonstrated that when medical staff denies hospital privileges to an applicant, the denial of the application can be perceived as a group boycott against the applicant because the staff competes with the applicant. The same applies when a hospital staff denies privileges to an entire group of nonphysicians.58

The Wilk v AMA lawsuit occurred in the years between Goldfarb v Virginia State Bar and Arizona v Maricopa County Medical Society.56,59 By the time the Wilk v AMA trial started in 1980, the Arizona trial had not yet commenced; therefore, its possible application to medicine was not yet available. Thus, how the Goldfarb decision might be applied to the plaintiffs' complaint of antitrust by the defendants required much interpretation, especially since the Goldfarb ruling was recent.60 The interpretation of this law during the Wilk v AMA trials would be used thereafter in other trials pertaining to antitrust in health care.

Section 1 of the Sherman Antitrust Act prohibits arrangements to restrict trade.55 These arrangements do not need to be formal. They can be contracts or other agreements, written or not, where the parties decide to work together in the restraint of trade. Thus, when a plaintiff alleges that a defendant has broken antitrust law, the plaintiff has the responsibility to show that the defendant worked together to establish a monopoly in an industry or to restrain trade in the market.55

Within Section 1 of the Sherman Act, there are 2 ways to establish an antitrust complaint. The first argument is for per se offenses. The second is for those that fall under the “rule of reason.” A per se violation does not require a demonstration of the effect on the market or of the intentions of those who engaged in the practice. Some anticompetitive behavior encourages competition within the market. Thus, per se analysis looks to see if the practice promoted or suppressed market competition. A rule of reason analysis requires demonstration of intent, motive, and behaviors to show if there was an unreasonable restraint of trade based on economic factors. Rule of reason requires the conditions to be reviewed before and after the restraint was imposed as well as the nature of the restraint and its effect on the market.

When defendants' business behaviors result in trade restraint, whether intentional or not and without the need for there to be an effect on competition, the courts have already determined that it is illegal per se.55,61 For plaintiffs, “[i]f the defendants' conduct falls within the category of a per se offense, the plaintiff need only show the existence of the conduct to establish a Section 1 violation.”55 Summarily, the plaintiffs do not need to prove that that the defendant possessed market advantage, prove that there was damage, or refute the justifications of the defendants.61 The advantage of per se analysis is that it is open to less interpretation and that the case is shorter, less complex, and easier for the jury to understand. Per se analysis proves that the action of the defendants is adequate to show that it will have a damaging effect on the competition. It shows that there is no need to analyze the case for any particular effects because the actions are significant.

However, per se analysis is relatively narrow in its approach and, some offenses fall outside of it or are not clear. For this reason, the Sherman Antitrust Act was modified to include the “rule of reason.”62 With the rule of reason, there is an examination of facts to determine the reasonableness of the effect of the alleged restraint on competition.62 Unlike per se law, the plaintiffs have to prove all elements of the case.61 It would seem that no counsel for a plaintiff would want to start out using the rule of reason, as the burden of proof rests entirely with the plaintiffs.

Section 2 of the Sherman Act prohibits monopolization of markets. In Section 2, it must be shown that the alleged business behavior creates a monopoly or threatens monopolization. This may be done by a collaboration of parties or a single party.55,62 The section states that any person or those that act in concert are guilty of violating the act if they “monopolize, or attempt to monopolize, or combine or conspire with any other person or persons, to monopolize any part of the trade of commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations.”63

Thus, there can be 3 ways of looking at offenses regarding the Sherman Act. One is where there is an actual monopolization. Another is when there are attempts to monopolize, but it does not happen. Finally, there are conspiracies to monopolize. If any of these conditions can be demonstrated, the plaintiffs then show that the monopoly was continued when the defendants willingly maintained the behavior and engaged in exclusionary conduct.63

Thus, as this relates to Wilk v AMA, it was essential that McAndrews show that 1 or more of these conditions existed. It is no coincidence that McAndrews used the word conspiracy throughout his arguments during the trial and that the defense counsel fought so bitterly against this accusation.

The Sherman Antitrust Act was updated with the Clayton Act of 1914.55 The Clayton Act defines the extent of damages that may be requested by plaintiffs if the defendants are found guilty. The Clayton Act allows the plaintiffs to sue for 3 times the damage caused by the activity of the defendants that violates any federal antitrust laws.63 Thus, not only would the lawsuit be costly to the plaintiffs from emotional and financial perspectives, but if they lost the case, there would be no payment for damages. If the plaintiffs won, the financial loss to the defendants would be large, to include the legal costs and damages awarded.

During the first trial of Wilk v AMA, hours of arguments between the plaintiffs' and the defendants' counsels centered on whether the alleged Sherman Act violation should be analyzed under per se or the rule of reason. Given the advantages of the per se approach, McAndrews and his legal team proposed to the court that the AMA and its conspirators' business behaviors should be tried as a per se offense.64 They asked that the jury determine if the conduct of the defendants amounted to a per se violation.62 However, the plaintiff's request to have the case analyzed under per se was denied.

Eventually, the court determined that the boycott was the endpoint that the plaintiffs alleged and the effect that the defendants desired to achieve rather than the means through which they desired to achieve them. The court decided that the rule of reason would therefore be used.62 In this setting, McAndrews and his team would have to not only prove that all 15 defendants were guilty of violating antitrust law but also consider the rebuttals of all of the defendants and reply to each of them. For the defendants with their lawyer teams and extensive resources, this process would be relatively easy; however, for the plaintiffs, this would be a monumental task.

McAndrews knew that the AMA and other defendants were not going to defend themselves against an antitrust suit. Instead, their strategy would put the reputation of the chiropractic profession on trial before the jury. Even though the mounds of evidence clearly showed that antitrust laws were broken, chiropractic had to overcome the very stigma that organized medicine worked so hard to create over many decades.

Plaintiffs' Arguments

On the morning of December 9, 1980, in Chicago, Illinois, opening statements began in front of a jury of 12 people with Judge Nicholas J. Bua presiding. Mr George McAndrews (Fig. 1) and Mr Paul Slater were the attorneys representing the plaintiffs. Before the main part of the first trial could start, the jury had to be selected, and the legal counsel for both the plaintiffs and the defendants presented their opening statements. An entire day was spent on jury selection. The opening statements from the lawyers representing all the defendant organizations and individuals took another day. Early on, it became apparent that this was going to be a long trial.

Figure 1.

- George McAndrews, the lead attorney for the plaintiffs.

During his opening statements, McAndrews described to the jury what chiropractic was, the main chiropractic tenets, how it was different from medicine, and the backgrounds of the plaintiffs. McAndrews stated,

We expect to prove that chiropractic is a profession that originated in the United States in the year 1895. The word ‘chiropractic' comes from two Greek words ‘cheiro praktikos' meaning hand practice. It developed from the use of the hands of an individual by the name of Dr Palmer who learned to adjust the joints of the spine. The joints of the spine are like any other joint. They move or articulate one with the other. The spine is the main weight-bearing member of the body and it is also the source of many aches and pains.65

At the end of his opening arguments, he summarized the main accusations of the plaintiffs against the defendants:

...various defendants conspired among themselves, with each other, to contain and eliminate, to boycott the profession of chiropractic, with the ultimate purpose of eliminating it as a licensed profession in this country. We will ask that you direct your attention to the private activities, not to the activities undertaken in the legislature, not to the activities undertaken under free speech, to talk to the people. We acknowledge those as the proper forum for debate. Our complaint comes about because there was a private combination or conspiracy to utilize private agreements and understanding to undo the work of the legislature.65

In his opening arguments, McAndrews explained that the antitrust suit involved the plaintiffs, who were chiropractors, and the defendants, which were medical organizations and 4 individuals who previously held leadership positions in the AMA. The defendants were charged with conspiring, “among themselves, with each other, to contain and eliminate, to boycott the profession of chiropractic, with the ultimate purpose of eliminating it as a licensed profession in this country.”65

McAndrews provided a brief overview of chiropractic and its origins, including its founder, Daniel David (DD) Palmer. He described chiropractic as the practice of adjusting (manipulating) joints of the spine and emphasized that chiropractic began from clinical observations of DD Palmer. McAndrews described the spine as a series of bones and joints that house the nervous system, which reaches to all areas of the body. He explained to the jury that it was presumed that adjusting spinal joints would stimulate nerves and result in health, whereas if nerves were not stimulated, ill health could result. He also proposed that pain was one of the sensations carried by the nervous system. Further, he explained that sometimes pain or dysfunction in a distant area of the body can be the result of a spinal problem because of nerve interference.

McAndrews provided an overview of the 2 philosophical subsets within the chiropractic profession: the narrow scope (straights) and the broad scope (mixers). He shared that the straight chiropractors limited their practices to adjustments of the spinal column by hand, whereas the mixer chiropractors included adjunct therapies, such as hot packs, ice, or electrical stimulation, in addition to spinal adjustments by hand. He emphasized that regardless of which group a doctor of chiropractic belonged to, chiropractors believed that by manipulating spinal joints, they could “induce or retard a neural or vascular or chemical reaction throughout some other portion of the body.”65

McAndrews pointed out to the jury that chiropractic was a licensed health care profession in all 50 states and that the plaintiffs were practicing within their legal scope of practice and based on their professional training. It was highlighted that at the time of the AMA boycott, there were no laws that would prohibit a chiropractor from referring a patient to a hospital for x-rays or laboratory, nor were there laws that would prevent a medical doctor or radiologist from providing care to these patients. There were no laws that would prevent a chiropractor from receiving x-ray or laboratory results or reports for their patients. Yet the AMA, through its threats to its members and other organizations, created an environment that prevented these services from being available to chiropractors and their patients. By doing this, the AMA and the other defendants conspired to monopolize and engaged in exclusionary conduct, which resulted in suppressed market competition against chiropractors.

Defendants' Arguments

The AMA and its legal team had years of experience fighting and winning similar cases. The goal of the defendants' legal teams was to prove to the jury that chiropractic was a threat to the health of the public and therefore demonstrate that the actions of organized medicine were in the best interest of the public.6,66 They claimed in their arguments the following:

Chiropractors did not diagnose, they overused x-rays and focused on money making, and they used practice building schemes as the basis for health care practices instead of what was in the best interest of the patient.

Chiropractic was not based on science, and there was no scientific evidence that chiropractic “cured” disease.

Chiropractic relied on dogma and therefore was a cult. Chiropractors proclaimed untested hypotheses, included a spiritual approach to treatment, had lower educational standards compared to medicine, and did not have the depth and breadth of medical education.

The defense lawyers argued that because medical doctors took responsibility for a patient under their care, patients could not also be under chiropractic care since they claimed that the 2 health paradigms were incongruent with each other.

This was called the “patient care defense,” in which they argued that the AMA's actions were done primarily out of concern for the lack of scientific basis. The lawyers argued that the public was in danger and that there was no other way to control this risk than to have the AMA eliminate the entire chiropractic profession. They argued that the AMA's actions were justified since the leaders of the associations perceived that they were acting as guardians of the public's health. As stated in one of the defense attorney's opening remarks, “Any procedure, even if it were done by a medical doctor, if it lacked a basis in science and if it wasn't scientific, the AMA strongly opposed it.”65

The sessions were grueling and lasted for more than 2 months. The lawyers argued and offered readings of depositions. Witnesses were summoned to the stand to provide testimonies. There was a tremendous amount of information to review. The AMA brought volumes of materials to the courtroom to discredit the reputation of chiropractic, engaging the judge and jury in a lengthy investigation into what they perceived were the flaws of chiropractic. The final record of the proceedings included over 100 depositions, more than 1200 exhibits, and more than 11,000 pages of transcripts. However, the defendants' lawyers spent little time defending issues surrounding the primary purpose of the trial, which was the alleged antitrust violations.

While the lawsuit was ongoing, the AMA and other defendants continued to enact their plans to suppress chiropractic. According to defense counsel for the Joint Commission, the Joint Commission 1980 standards stated, “The standards do not contemplate the chiropractors be granted membership on a hospital's medical staff unless otherwise provided by law.”65 However, previous documents were clear about the consequences of a hospital's accreditation status should it do business with chiropractors. A question was asked of the AMA: “Would it in any way affect our accreditation status? If the hospital ran laboratory tests or made X-rays on a chiropractor's patients on an outpatient basis.” The response was a reflection of the AMA's campaign: “The Commission [Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals] looks on chiropractors as cultists. A hospital that encourages cultists to use its facilities in any way would very probably be severely criticized and lose its accreditation.”67

The Joint Commission opposed accrediting status if a hospital provided medical staff privileges to a chiropractor. When asked about a bill being considered in the New Mexico legislature that proposed including chiropractors on hospital staff, the director for the Joint Commission's Hospital Accreditation Program replied, “The unfortunate results of this most ill-advised legislation would be that the Joint Commission would withdraw and refuse accreditation of the hospital that had chiropractors on its medical staff.”68 Similar correspondence from the Joint Commission was sent in reply to several other queries about granting medical staff privileges.

The strong influence of the AMA on the Joint Commission and the Association of American Medical Colleges established that federal hospitals, including the Veterans Administration (VA), were not allowed to work with chiropractors.69 In 1979, the executive vice president of the AMA wrote to the chairman of the Veterans Affairs Committee of the House of Representatives imploring him not to provide support to HR 3246, a bill that included language to develop plans to consider the provision of chiropractic care at VA facilities. He urged,

Once this Pandora's box is opened, there would seem no logical basis for refusing to include chiropractic physicians on the medical staff of the VA or the House staff. In summary, the Association of American Medical Colleges strenuously opposes passage of H.R. 3246, because it would result in the delivery of incompetent care to veterans, poor use of the limited healthcare dollar, perpetuation of an unscientific cult and ultimately poor use of precious educational funds.70

In his message, he threatened that if the bill should pass, the American medical schools would likely consider relinquishing the significant resources they had provided to the VA for many years. He said, “Should this happen the medical schools of the nation might well reconsider the propriety of continuation of the mutually beneficial affiliations of the last three decades.”70 Thus, it was clear that their anti-chiropractic stance continued.

By the end of the first trial, the focus of AMA's defense arguments was not on antitrust-related content. They did not defend their stance to eliminate chiropractic competition in the marketplace. Instead, they focused primarily on the lack of published evidence about what chiropractors did. The AMA's defense claimed that the AMA was trying to protect the public.

Closing Arguments

After nearly 3 months in court, during which time jurors had to be present every day and the lawyers, plaintiffs, defendants, court staff, and the judge had grown quite weary, the day for the closing arguments arrived. Both sides had sacrificed years of work, countless hours, and millions of dollars.

McAndrews's closing arguments to the jury focused on the purpose of the case and antitrust laws:

We have alleged and we hope we will have proved that... these defendants in interfering with the freedom of their members to voluntarily associate with the plaintiff and with other chiropractors have violated the antitrust laws.71

McAndrews argued that the AMA knew that the health care that chiropractors provided was helpful, not quackery. He argued that organized medicine had suppressed this knowledge so that they would retain control over all health care in this area. He argued that the AMA was aware that medical training was weak in the area of treating musculoskeletal disorders; thus, the AMA perceived chiropractic as a threat in this area of medical practice.

The purposes involved economics, fundamental economics, hundreds of millions of dollars in Medicare funds. Billions of dollars in insurance payments are involved in the health care world... The category of the dispute was filed under ‘Protect the territory.'71

He reminded the jury that the AMA's Committee on Quackery (CoQ) fought to restrain trade, including undermining the efforts for chiropractic care to be reimbursed through insurance.

Doyl Taylor met with Blue Shield Corporation, if you recall that, let's prevent insurance coverage for chiropractors or the patients of chiropractors.71

McAndrews then summarized that organized medicine perceived that chiropractors were a competitive threat. Quoting from the transcript, McAndrews underscored from AMA notes that “[m]any of our physicians are apathetic toward chiropractors and feel they have a place in the medical care field. This, of course, our committee is in disagreement with.”72

The AMA's hand had been revealed—that the AMA and the other medical associations that they influenced were working together to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession. McAndrews read from medical statements in the court documents that demonstrated organized medicine's intention for market dominance:

Our overall goal, of course, is to eliminate chiropractors from Kentucky. This may not be possible, but we shall attempt to do so. It is unrealistic, I believe, to expect us to be able to do this in one or two years. This will be a gradual evolution and erosion of their position by continued harassment and first through professional contacts, and then hopefully public contacts and gradually as our political skills improve, increasing the restrictive legislation drafted, of course, in the public good, but reducing the chiropractor's activities.72

McAndrews pleaded for the jury to decide in favor of the plaintiffs by finding the defendants guilty.

Judge Bua and the Jury Decision

On January 30, 1981, Judge Bua gave the jury its instructions:

THE COURT: Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, you are further instructed that chiropractors have been given the right by law to carry on their practice and to engage in the treatment of patients, subject to whatever legal limits are placed on their licenses. The question of whether chiropractic poses an impermissible hazard to the health and welfare of the public is one for the Congress and/or the state legislatures to resolve, not the defendants or other private persons or groups. Because those legislative entities alone have the authority to determine whether chiropractors should be permitted to offer their services to the general public, the law will not allow their decision to be overturned.

It is a different question, however, whether members of the medical profession may limit their own relationships with chiropractors for the purpose of practicing their own profession according to standards they consider necessary or desirable for the proper practice of medicine.

As I have already instructed you, reasonable ethical principles having that objective and not aimed at barring the practice of chiropractic within the limits allowed by state licenses may be lawful if they do not, in operation, also have a significant and unnecessarily adverse effect on the chiropractors' ability to carry on their trade. You may, therefore, consider as bearing on the reasonableness of the defendants' purposes what the evidence shows to be the depth and sincerity of their beliefs that the sharing of responsibility by doctors with chiropractors poses substantial hazards to the welfare of patients and the public welfare.73

Judge Bua went on to say,

There are four essential elements which plaintiffs must prove in order to establish their claim that two or more defendants conspired to monopolize within the meaning of Section 2 of the Sherman Act:

1. That there was a conspiracy between two or more defendants to monopolize a relevant market;

2. That if so, those defendants entered into such conspiracy with the specific intent to monopolize that market;

3. That one or more of the acts claimed by plaintiffs in their Section 2 claims was done and was in furtherance of such conspiracy to monopolize;

4. That if so, separately with respect to each plaintiff's claim, the conspiracy so established was the proximate cause of damage to the business or property of that plaintiff.

The burden is on plaintiffs to establish each of these elements by a preponderance of the evidence in this case. As to any plaintiff whom you find has not sustained the burden of proof as to all of the above elements which the court just read to you, you must find in favor of the defendants.

For the plaintiffs to recover damages, it is not enough to show that the defendant or defendants violated the antitrust laws. The plaintiff must also establish by the preponderance of the evidence that the violation of the antitrust laws was the proximate cause of injury or damage to his or her business.73

At the conclusion of the first trial, the judge asked the jury leader to read the statement. The jury read the decisions for each of the defendants. All came back with a not-guilty verdict for violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act by the defendants. The chiropractors had lost the first trial, and it was a heartbreaking defeat not only for them but for the entire chiropractic profession.

On closing, Judge Bua complimented Mr McAndrews:

Mr. McAndrews, I had occasion to indicate to you after your opening statement that that was without a doubt the finest opening statement I have ever heard in my entire career both on the bench and in trial practice. Your final arguments were superb. And I don't know how many cases you have tried or how long you have been out of law school but I do know this: That you have demonstrated one of the finest pieces of representation that I have ever had the pleasure to see. I don't consider this a loss because it is quite obvious that you are not just in the category of a lawyer in this case . . . you were almost evangelistic about it without being evangelistic, if you get the court's meaning. And I would not consider this a loss because you have demonstrated to me that the Bar of Illinois is very professional, and I say that to Mr. Slater and to everyone on your staff. I would not feel too badly. It is a loss to your clients, but as professional pride goes, you should be very proud of what happened.73

Whereas the AMA and other defendants breathed a sigh of relief thinking the battle was over, McAndrews knew that this was merely the eye of the storm. After the first trial was complete, he immediately began to prepare his arguments for an appeal.

The Second Trial

Appeal for the Second Trial

McAndrews brought forward an appeal to the decision of the first trial. His primary concern focused on Judge Bua's jury instructions. McAndrews disagreed with Judge Bua suggesting that a boycott could be lawful if it was due to the “genuine belief by medical doctors that chiropractic is dangerous quackery.”66 McAndrews stated that in spite of his many objections, the jury had incorrectly received materials for consideration that focused on the ills of chiropractic rather than business and economics. He proposed that this clouded the instructions and resulted in a verdict in favor of the defendants.

The defendants argued that they acted in good faith to protect the public and therefore spent most of the trial focusing on trying to prove that chiropractic was quackery. The appeals judge, James Doyle, stated, “The upshot of all this was that much of the trial, and virtually all of the parties' arguments to the jury were a free-for-all between the chiropractors and medical doctors, in which the scientific legitimacy of chiropractic was hotly debated and the comparative intensity of the avarice of the adversaries was explored.”

Judge Doyle offered his corrected instructions:

The jury should be instructed in appropriate language to the following effect: The burden of persuasion is on the plaintiffs to show that the effect of Principle 3 and the implementing conduct has been to restrict competition rather than to promote it. If the plaintiffs have met this burden, the burden of persuasion is on the defendants to show: (1) that they genuinely entertained a concern for what they perceive as scientific method in the care of each person with whom they have entered into a doctor-patient relationship; (2) that this concern is objectively reasonable; (3) that this concern has been the dominant motivating factor in defendants' promulgation of Principle 3 and in the conduct intended to implement it; and (4) that this concern for scientific method in patient care could not have been adequately satisfied in a manner less restrictive of competition.66

These instructions meant that in the second trial, the defendants would need to show that their actions in the 1960s and 1970s were based on a patient care motive and required the application of rule of reason rather than per se rule. So, although the defendants had shown some hostility to chiropractic, they would need to demonstrate that they were acting in good faith to show that their activities were not illegal.

The appeals judge explained that it was not clear how the defendants supported the public interest motive. There was concern over how efforts to influence Congress, legislature, and federal agencies to contain or eliminate the chiropractic profession would be in the public interest, not simply a financial or political motive. Although organized bodies were free to influence legislation, there was “no legal justification for economic measures to diminish competition with some medical doctors by chiropractors.”66 Doyle stated that the decision was for Congress and state legislatures to determine if chiropractic was a health hazard and not the responsibility of the defendants. In his decision, he wrote,

We conclude that the instructions to the jury were prejudicially erroneous in two respects. The overriding question in the case was whether, in applying the rule of reason, the jury was to be allowed to consider any factor whatever beyond the effect of defendants' conduct on competition. The district court elected to permit the jury to go beyond that single test and to consider the defendants' motives. But it failed to confine that consideration sharply to defendants' patient care motive, as contrasted with their generalized public interest motive. And, with respect to the patient care motive, the court failed to convey clearly and understandably the manner in which the jury was to weigh it, particularly as to the least restrictive means requirement.74

Because of these reasons, the plaintiffs were granted a new trial. By this time, it was 1987, and McAndrews had already dedicated many years to the lawsuit. His hope was that the second trial would result in a better outcome and help to alleviate the damage that the boycott continued to place on the chiropractic profession. If conditions were going to change, he knew that the AMA must be found guilty of their illegal actions against the chiropractic profession. He also believed that having another jury trial could result in another negative outcome. Therefore, McAndrews made a strategic decision weeks before the second trial and requested a bench trial instead of a jury trial. Choosing a bench trial meant that a judge would be the sole person to decide the outcome. By choosing this path, the plaintiffs would forfeit any claim to retrieve financial damages from the illegal boycott. Instead of money for the plaintiffs, McAndrews hoped that the court would declare an injunction against organized medicine, primarily the AMA.

Judge Getzendanner Hears the Case

Judge Susan Getzendanner was no ordinary judge (Fig. 2). She had a distinguished career as a trial lawyer before being named to the federal bench. She was known for her sense of humor and was a trailblazer for women in the legal profession, being the first female partner in a large law firm in Chicago and the first woman to be appointed as a judge for the federal Northern District of Illinois.75,76

Figure 2.

- Judge Susan Getzendanner, the first woman to be appointed a judge for the federal Northern District of Illinois.

It was happenstance that Getzendanner became the judge who presided over the second trial. The case was originally assigned to another judge. When asked how she came to watch over the case, she said that she was approaching the end of her time serving as a judge and, because she processed cases quickly, she had time open on her schedule. She approached another judge and asked if he had any cases to give her. A case had been languishing on his desk for some time, so he decided to hand her the Wilk v AMA lawsuit.77 Because this trial was in Chicago, she was already very familiar with the AMA trial lawyers, having met them on various occasions. She began the second trial on April 22, 1987.

In the second trial, the antitrust suit alleged that there was a violation of Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Act (15 USC). The plaintiffs claimed that the defendants organized and participated in a boycott of doctors of chiropractic. They stated that the defendants conspired to unreasonably restrain competition between doctors of chiropractic and medical doctors and conspired and attempted to monopolize certain healthcare markets.

Attorneys McAndrews and Slater argued that the AMA had feared competition from doctors of chiropractic, that the AMA recognized that some chiropractors may achieve their goal of emerging as “medical men” if organized medicine remained apathetic to the problem. The plaintiff's counsel stated that the defendants were using the chiropractic issue to rally national unity for the medical profession since its membership numbers were dropping. As evidence, the AMA's CoQ documents stated, “The Committee believes that the campaign against chiropractic is an effective ‘unity' mechanism for medicine at all levels and physicians at all levels must be made aware of this extremely beneficial side effect, particularly at this time.”78

The AMA had adopted a plan to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession through a boycott.79 The attorneys argued to support this plan,

the AMA manipulated JCAH rules to promote and enforce the boycott,

the AMA Principles of Medical Ethics were used to enforce the boycott,

the AMA stifled chiropractic education programs,

the AMA stifled insurance reimbursement for chiropractic services, and

the AMA tampered with the Department of Health, Education and Welfare study regarding chiropractic services for Medicare.

To succeed in their arguments, McAndrews and his legal team needed to show the judge that the boycott was not over and continued to harm chiropractic. Although the AMA had changed its Principles of Medical Ethics in 1980 before the first trial, they needed to demonstrate that there were lingering effects. They also needed to show that there was a past and present injury to the plaintiffs as a result of the AMA's boycott.

McAndrews and his team outlined the following arguments to address Judge Doyle's statements:79

-

1.

The defendants failed to establish “genuine concern in care of individual patients.”

By not allowing medical doctors to work with chiropractors or to receive chiropractic patients, they were depriving patients of best possible care. Not allowing a chiropractor to send patients with a health concern to a medical doctor leaves patients without medical supervision. The AMA CoQ members were aware of the usefulness of spinal manipulation and that this treatment was beneficial for some patients. Thus, they knowingly deprived patients from accessing this service.

-

2.

The defendants failed to establish objective reasonableness

The AMA did not use scientific methods to investigate chiropractic and assess their findings to see what benefits or harms there might be. Instead, the AMA's CoQ began with the end in mind, which was to eliminate the chiropractic profession. Not only did they fail to apply scientific methods to their investigations, they also suppressed any supporting information they received on the benefits of chiropractic. The information the CoQ had showed not only that patients benefited from chiropractic services but also that, for certain conditions, the results were superior to those offered by medical doctors. The CoQ also ignored that the majority of chiropractors did not believe in the “one cause one cure” theory that adjusting spinal subluxations would cure disease.

-

3.

The defendants failed to demonstrate that their dominant motivating factor was a concern for the scientific method and the patients' best interests.

The evidence showed that the AMA's focus of concern was on the success of the boycott. The primary motivating factors appeared to be fear of competition and the desire to have a common enemy to unify the medical profession. In looking at the documentation and their actions, there was a lack of evidence that showed that the AMA's actions to contain and eliminate chiropractic were out of a true concern for the public's interest.

-

4.

The defendants failed to establish that their alleged concern for the scientific method could not have been adequately satisfied in the manner less restrictive of competition.

The evidence demonstrated that the CoQ members chose not to communicate with chiropractors or to seek out more information for fear that those actions would imply that the AMA was legitimizing chiropractic. And instead of the AMA choosing to assist chiropractic to address the AMA's concerns, they fought to diminish ways for chiropractors to improve education and research. For example, if the AMA's concern was poor education, then they could have assisted and not suppressed improvements in chiropractic education by allowing medical doctors to teach at chiropractic institutions. They chose not to meet with chiropractors or chiropractic leaders to discuss possible solutions. The AMA was not able to demonstrate that they made attempts to address their concerns about chiropractic.

Arguments About Economic Harm and Competition

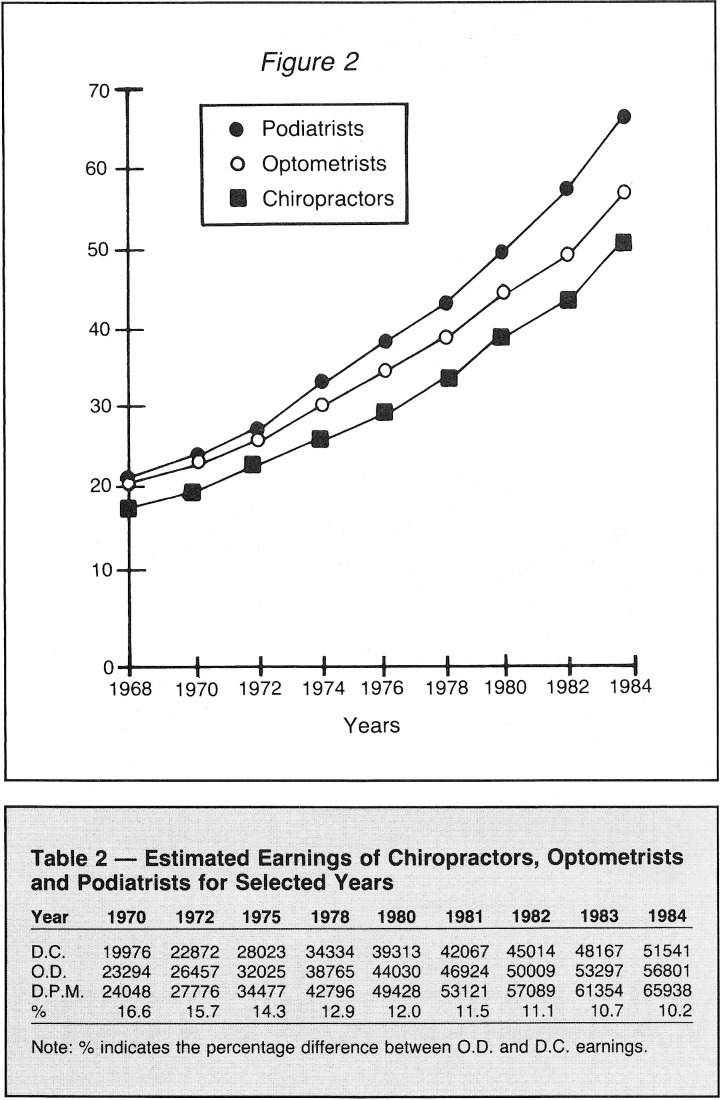

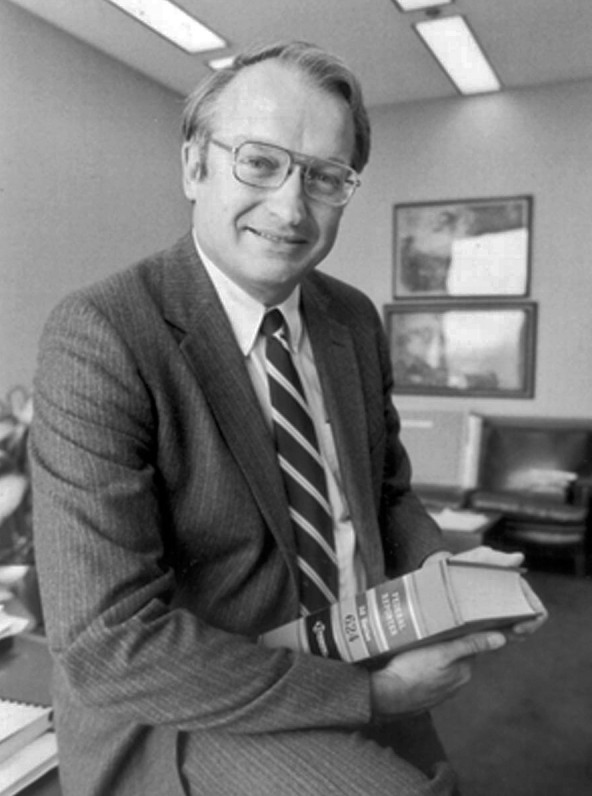

Years had passed by the time the second trial began. Some of the original defendants had already settled with the plaintiffs out of court. One main argument made by the AMA and the remaining defendants was that their policies regarding chiropractors did not affect chiropractors from an economics perspective. McAndrews knew that he would need to present evidence that this argument was false. For that, McAndrews's team consulted with a recognized economist, Miron Stano, PhD. Dr Stano was a professor of economics and management, having obtained his doctorate from Cornell University, specializing in medical economics. At the time that he was involved in the Wilk v AMA case, he was employed in the Department of Economics at Oakland University in Michigan.80

Plaintiff counsel Paul Slater invited Stano to assist him in developing a counterargument to the defendants' stance.81 In preparing for the trial, Stano compared the earnings of chiropractors with optometrists and then observed the actual and forecasted earnings of doctors in each profession over time. Stano obtained the actual earnings of chiropractors and optometrists from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics from 1968 to 1984. Then, using a statistical process called regression, he forecasted what the earnings should be based on the growth trends of the actual data and then cross-checked the forecast with the actual earnings reported for later years. The results showed that for optometrists, the actual earnings and forecast earnings were very close. For the chiropractors, however, there were discrepancies in actual earnings and projected earnings. The actual earnings were significantly lower than the projected earnings during the years 1972–1979, supporting the plaintiffs' point that the AMA's boycott on chiropractic depressed the earnings of chiropractors even after the boycott was claimed to have been lifted.82 Data that were analyzed by Stano showed that during the years of the boycott, chiropractic suffered compared to other professions that were not boycotted (Fig. 3).83 Stano concluded, “The boycott reduced chiropractors' incomes significantly below those of the two most comparable professionals. As the boycott was relaxed, estimated earnings of doctors of chiropractic approached those of optometrists.”83

Figure 3.

- This chart and table represent initial economic analysis by economist Miron Stano, PhD, and were published in 1987. The dip in actual earnings show the effect of the American Medical Association boycott (reproduced with permission from the American Chiropractic Association).

During the second trial, Stano provided several perspectives of how suppression of a profession by another profession not only affected the suppressed group but also had a negative effect on consumers. With Stano on the witness stand, Slater asked him to assume that medical doctors and chiropractors were market competitors for certain human health problems. Slater asked a series of questions of Stano:

Slater: “And I ask you, if medical doctors did something to interfere with the ability of consumers or the ability of referring practitioners to substitute chiropractic services for M.D. services, whether you have an opinion as to what would happen to the demand for chiropractic services in total?”

Stano replied, ‘Based on economic arguments, economic theory, one would predict that the demand for chiropractic services would diminish.'

Slater: ‘Okay. And what would happen to the demand for the medical physician services?'

Stano: ‘One would predict that the demand for other substitutes, including services of medical physicians, would increase.'

Slater, ‘And what would happen to the price charged by medical physicians?'

Stano: ‘Again using standard economic theory, one would expect that the prices would be increasing.'

Slater: ‘Now, would this be an anticompetitive result in your opinion?'

Stano: ‘Yes, it would.'80

Slater then asked Stano to assume that the services by medical doctors were of higher quality than chiropractors and continued with his line of questioning:

Slater: ‘Would it still, in your opinion be an anticompetitive event to interfere with the substitutability?'

Stano: ‘Absolutely. What is important is a range of alternatives produced by the free market. Even if one commodity is regarded as – and I will assume it is a higher quality than another commodity, I think that would be anticompetitive.'80

Stano went on to state that in a suppressive environment, the reduction in choices for consumers would have a detrimental effect on society. If medical care was of higher quality and the availability of chiropractic care was reduced in the free market, then some consumers would not be able to afford the medical care and have no or limited access to chiropractic care. With no or limited access to care, the consumer would effectively have less quality care because of the suppression.80

In support of the plaintiffs' assertion that a boycott against chiropractic by the defendants lasted longer than when it was supposedly lifted, Stano then explained the results of the statistical analysis he had performed in preparation for the trial. He explained that the AMA boycott continued well into the 1970s, based on the lower-than-expected earnings for chiropractors. However, Stano showed that when the boycott lessened around 1978, the average chiropractor's earnings demonstrated a significant increase by 1980 and continued to rise during the 1980s. Essentially, Stano's testimony and data demonstrated that the boycott had not ceased when the defendants said it had and that the effects were harmful to both the public and the chiropractic profession (Fig. 4).81,83

Figure 4.

- This chart and table show the percentage difference in earnings between chiropractors and other similar health professionals (reproduced with permission from the American Chiropractic Association).

Testimony by Per Freitag, MD, PhD, established that the services chiropractors provided benefited patients. Freitag was a professor of orthopedics and anatomy at Northwestern University and conducted a study of 2 similar hospitals: 1 that allowed patients access to chiropractic care and 1 that did not. In his study, he noted that the inpatient stay at the hospital without chiropractic care was an average of 14 days, whereas the stay in the hospital with chiropractic care was about 6 days. It was also estimated that there was a cost savings of appropriately $8000 per patient for those who had access to chiropractic care. During his testimony, Freitag noted the benefits of chiropractic to pregnant women. Instead of offering epidural steroid injections, he suggested that they could have chiropractic adjustments to ease musculoskeletal discomfort. Regarding chiropractic care of pregnant women, he testified that “it seemed to work, at least in the few that I came in contact with.”84

When Freitag was a graduate student at the University of Illinois, he assisted in the Department of Anatomy. He had visited the National College of Chiropractic because he was investigating the possibility of teaching there if he were to continue at the University of Illinois. During his testimony, he was asked for his thoughts about the quality of the chiropractic program at National. Freitag replied, “Yes, I was frankly impressed. The dissections that the chiropractic students had performed looked a lot neater and far better than the medical students had done at the University of Illinois.”85

Freitag's testimony confirmed that some medical doctors referred patients to chiropractors who provided treatment as an alternative to services provided by a medical physician. He suggested that chiropractors could provide care for some musculoskeletal conditions that would result in faster response time. This implied that there were grounds for competition between chiropractic and medicine in the area of musculoskeletal care.

More Defendants Settle

Various defendants had been resolving their issues with the plaintiffs throughout this time. For example, in 1985, the Illinois State Medical Society declared that:

...except as provided by law (statute or final judicial opinion), there are and should be no ethical or collective impediments to full professional association and cooperation between doctors of chiropractic and medical physicians. Individual choice by a medical physician voluntarily to associate professionally or otherwise cooperate with a doctor of chiropractic should be governed only by legal restrictions, if any, and by the individual medical physician's personal judgment as to what is in the best interest of a patient or patients.86

Thus, the Illinois State Medical Society had dropped its barriers to interprofessional cooperation between medical physicians and doctors of chiropractic in private practice and in hospitals. However, the AMA still held fast that their campaign to eliminate chiropractic was justified.

On June 12, 1987, defendant AHA settled out of court with the plaintiffs.87,88 The AHA provided a statement on chiropractic. This agreement was to be maintained for at least 10 years.89

The American Hospital Association specifically disavows any unlawful effort by any private, competitive group to ‘contain,' ‘eliminate' or to undermine the public's confidence in the profession of chiropractic.

The Association has no objection to a hospital granting privileges to doctors of chiropractic, where consistent with law, for the purpose of: (1) administering chiropractic treatment to patients who wish to have such treatment, whether administered in conjunction with or separate from other health care treatment or services administered by medical doctors or other licensed professional health care providers; (2) furthering the clinical education and training of doctors of chiropractic; or (3) having new diagnostic X-rays, clinical laboratory tests and reports thereon, made for doctors of chiropractic and their patients, and/or previously taken diagnostic X-rays, clinical laboratory tests and reports thereon made available to them, by individual pathologists or radiologists employed by or associated with such hospital, upon the request or authorization of the patient involved.47,89

Judge Getzendanner's Decisions

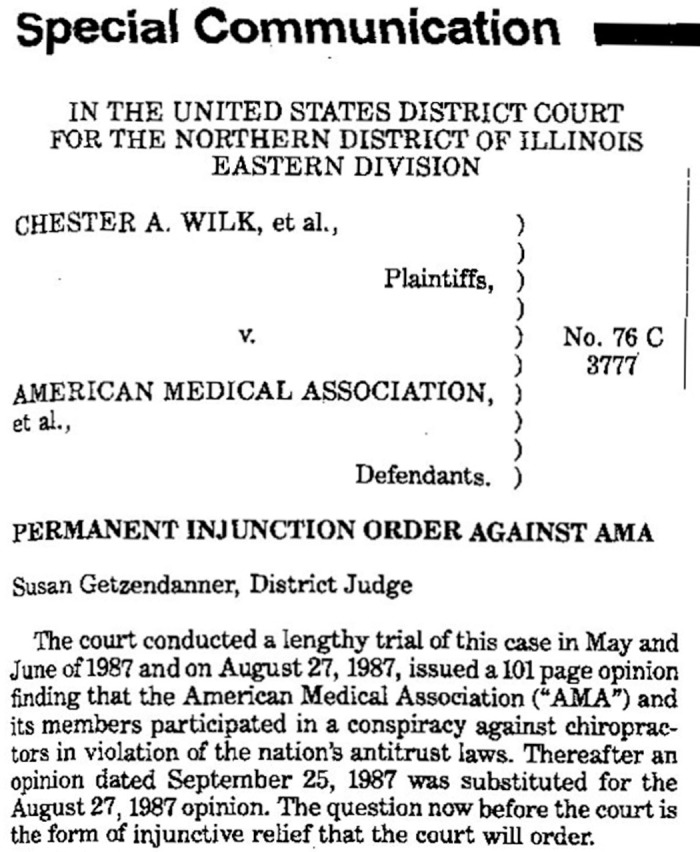

On August 27, 1987, Judge Getzendanner in the US federal court in Chicago declared that the AMA, the ACR, and the ACS had pursued an illegal boycott of the chiropractic profession between 1966 and 1980. The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) was found to have “knowingly joined the conspiracy but to have ceased its participation in 1986 with no likelihood that AAOS would renew any boycott or conspiracy against chiropractors.”90 There was great relief on the side of the plaintiffs (Fig. 5).91

Figure 5.

- A portion of the August 27, 1987, letter from Mr McAndrews to the plaintiffs announcing Judge Getzendanner's decision and that they won the lawsuit.

What remained was Getzendanner's final decision. With the final judgment declaration looming, on September 24, 1987, the ACS settled with the plaintiffs. The provision was that the following Statement on Interprofessional Relations with doctors of chiropractic would be maintained for at least 5 years:

The American College of Surgeons declares that, except as provided by law, there are no ethical or collective impediments to full professional association and cooperation between doctors of chiropractic and medical physicians. Individual choice by a medical physician voluntarily to associate professionally or otherwise cooperate with a doctor of chiropractic should be governed only by legal restrictions, if any, and by the individual medical physician's personal judgment as to what is in the best interest of a patient or patients. Professional association and cooperation, as referred to above, includes, but is not limited to, referrals, consultations, group practice in partnerships, HMOs, PPOs, and other alternative health care delivery systems; the provision of treatment privileges and diagnostic services in or through hospital facilities; working with and cooperating with doctors of chiropractic in hospital settings where the hospital's governing board, acting in accordance with applicable law and that hospital's standards, elects to provide privileges or services to doctors of chiropractic; association and cooperation in hospital training programs for students in chiropractic colleges under suitable guidelines arrived at by the hospital and chiropractic college authorities; participation in student exchange programs between chiropractic and medical colleges; cooperation in research programs and the publication of research material in appropriate journals in accordance with established editorial policy of said journals; participation in health care seminars, health fairs or continuing educations programs; and any association or cooperation designed to foster better health care for patients of medical physicians, doctors of chiropractic, or both.92

The ACS reportedly contributed $200,000 to the Kentuckiana Children's Center, a health care facility for disadvantaged children run by a chiropractor.93

The ACR also settled on September 24, 1987, and paid $200,000 toward legal costs. The ACR modified their ACR Statement of Interprofessional Relations with Doctors of Chiropractic for at least 10 years to read,

ACR declares that, except as provided by law, there are and should be no ethical or collective impediments to interprofessional association and cooperation between doctors of chiropractic and medical radiologists in any setting where such association may occur, such as in a hospital, private practice, research, education, care of a patient or other legal arrangement. Individual choice by a radiologist to voluntarily associate professionally or otherwise cooperate with a doctor of chiropractic should be governed only by legal restrictions, if any, and by the radiologist's personal judgement as to what is in the best interest of a patient or patients.94

Final Decision

Judge Getzendanner noted that for the trial, the “record consists of 3,624 pages of transcript, approximately 1,265 exhibits, and excerpts from 73 depositions,”95 all of which she reviewed. And, once her review and the arguments were completed, she decided swiftly. On September 25, 1987, the final judgment was declared that she ruled against the remaining defendants. She based her decision on whether the AMA violated antitrust laws. She found that “the American Medical Association (‘AMA') and its members participated in a conspiracy against chiropractors in violation of the nation's antitrust laws.”96

In her statement, she explained that there were several questions that needed to be answered for her to come to this decision.95 The first was to determine if there was a boycott. She determined that the AMA and others engaged in a group boycott against chiropractors from 1966 to 1980, the time in which Principle 3 was in effect.

Next, there was a need to determine if the boycott resulted in unreasonable restraint of trade, which would violate Section 1 of the Sherman Act. To determine this, she used the rule of reason analysis. She chose the rule of reason analysis instead of the per se approach because a Seventh Circuit Court had already decided that Principle 3 did not fall under per se treatment. The basis of the reasoning was that professional competitors could not “deprive consumers of information they desired” and that arguing the reason was for the patients' own good was not justifiable.95

Judge Getzendanner analyzed the AMA's arguments from the first trial, which asked if what the AMA was doing was in the best interest of the public. She examined their arguments from a legal point of view. She questioned if it was demonstrated that “the AMA and its members genuinely entertained a concern for scientific method in the care of patients.”95 The AMA made no efforts to do research that would determine if chiropractic was or was not scientific and thus failed to show that they applied the scientific method to their own actions. Even though in the 1960s there were examples of advertisements and publications showing that some chiropractors seemed to reject scientific evidence, there was also evidence that many chiropractors supported science and that chiropractic care was effective for some conditions for some patients.

She considered that the AMA was aware not only that chiropractic was effective for some patient complaints but also that chiropractic care was more effective in some cases than medicine (eg, workers' compensation and back injuries). There was evidence that chiropractors were better trained than medical doctors to address specific types of musculoskeletal conditions. The CoQ had found evidence that there were redeeming values to chiropractic services. However, they suppressed any beneficial information and continued their plan to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession. Had there been a scientific approach, the AMA would have considered some of what chiropractors do as a potentially helpful method and not have labeled everything as quackery. Thus, Judge Getzendanner stated that “the AMA has failed to meet its burden on the issue of whether its concern for the scientific method in support of the boycott of the entire chiropractic profession was objectively reasonable throughout the entire period of the boycott.”90

She questioned the methods used by the AMA with their quest to protect the public, which they used to support their claim of the patient care defense. She wondered if the AMA could have acted in a manner less restrictive of competition to address their concerns about practices that they believed to be quackery. She determined that the AMA did not demonstrate that they tried any other actions or campaigns before deciding to eliminate an entire profession. Thus, Judge Getzendanner concluded that “the AMA has failed to carry its burden of persuasion on the patient care defense.”90

She considered that the American public had several choices for health care when they experienced musculoskeletal problems. Both medical doctors and chiropractors would be in direct competition for these patients. In some cases, this competition was recognized by those in organized medicine. Thus, the AMA's goal was to contain and eliminate a profession that was in direct competition for a portion of the marketplace. At that time, the AMA held a large amount of market power and could use this power to destroy its competition. This resulted in adverse effects on chiropractic. Over many decades, the AMA had indoctrinated medical doctors and the public with their negative view of chiropractic, which seemed to have had a lasting effect.

It was shown that the AMA boycott eventually caused harm to the public. She summarized that the effects reduced a person's freedom of choice to select the health care provider of their choosing. It also raised costs since chiropractors had to purchase their own equipment and therefore pass along costs to the patients. And, by preventing medical doctors from referring patients to chiropractors, there was a loss of potential patients. The boycott prevented medical doctors from teaching in chiropractic programs, thus potentially reducing the quality of chiropractic education and research opportunities. In addition, the actions by the AMA resulted in a negative view of the public for chiropractic and likely reduced the number of patients seeking care. Therefore, she confirmed that the AMA's boycott did not promote competition but unreasonably restricted it.

The next question to answer was if any damage could be demonstrated by the plaintiffs. Stano's calculations demonstrated a negative economic effect. In addition, there was a negative and immeasurable impact on the reputation to chiropractors by calling them “unscientific cultists” and by not allowing them to work with medical doctors. However, Judge Getzendanner made it clear that she recognized the issues that the AMA brought before the court were of concern regarding chiropractic. She also made it clear that her decision was “...not and should not be construed as a judicial endorsement of chiropractic.”95

It was apparent in Judge Getzendanner's statement that based on the evidence, the violation had occurred. In her decision statement, she reported,

In the early 1960s, the AMA decided to contain and eliminate chiropractic as a profession. In 1963 the AMA's Committee on Quackery was formed. The committee worked aggressively—both overtly and covertly—to eliminate chiropractic. One of the principal means used by the AMA to achieve its goal was to make it unethical for medical physicians to professionally associate with chiropractors. Under Principle 3 of the AMA's Principles of Medical Ethics, it was unethical for a physician to associate with an ‘unscientific practitioner,' and in 1966 the AMA's House of Delegates passed a resolution calling chiropractic an unscientific cult. To complete the circle, in 1967 the AMA's Judicial Council issued an opinion under Principle 3 holding that it was unethical for a physician to associate professionally with chiropractors.96,97

Before the first trial, the AMA had already ended the CoQ and removed the statement in AMA documents that it was unethical to collaborate with a chiropractor. However, the AMA never formally announced this fact to the regular medical profession, the health care industry, or the millions of American citizens who had been bombarded for years with anti-chiropractic propaganda. Judge Getzendanner's letter stated, “Although the conspiracy ended in 1980, there are lingering effects of the illegal boycott... Some medical physicians' individual decisions on whether or not to professionally associate with chiropractors are still affected by the boycott.”97

Judge Getzendanner's decision confirmed that the AMA had broken antitrust laws, and she needed to determine the appropriate action. She had to decide whether the plaintiffs were entitled to an injunction. The Clayton Act provided her with the necessary support for her decision. The Clayton Act entitles someone to sue for injunctive relief to prevent future violations of antitrust laws. The AMA had argued that the plaintiffs did not demonstrate injury. They also argued that it would be impossible to distinguish what actions were directly linked to the boycott. For example, “If a medical physician refuses to associate with a chiropractor, who can say that the boycott was a contributing factor?”96 However, Judge Getzendanner's interpretation was that the members of the AMA's CoQ declared that their mission was successful in preventing medical doctors from working with chiropractors. This resulted in damage to the individual plaintiffs. She wrote, “Thus, the individual plaintiffs have been personally harmed, and continue to be personally threatened, by a lack of association with members of the AMA caused by the boycott and the lingering effects of the boycott.”95

In her decision, she considered that the AMA never made it clear to its members or other stakeholders that the boycott was over or that it was acceptable to associate specifically with chiropractors or make any other attempts to repair the damage that was done. So even though the AMA policies were no longer in place, the boycott-like actions seemed to still be in effect. Therefore, Judge Getzendanner decided that an injunction was necessary. However, the type of injunction that the plaintiffs were asking for was not granted. She wrote, “The plaintiffs appear to want a forced marriage between the professions. Certainly no judge should perform that ceremony.”95

She decided that her final declaration was not only to be made public but that it would be published in the AMA's esteemed JAMA, the very journal that had been used as a weapon against chiropractic for nearly a century. The injunction was to be published in the part of the journal that was part of the permanent record, one that could never be expunged.77 In the January 1, 1988, issue of JAMA, the injunction was published (Fig. 6).97

Figure 6.

- A sample from the injunction that was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. The full injunction notice published in the journal was only 2 pages long.

After the AMA's appeal to Judge Getzendanner's decision for an injunction was denied by the Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit in 1990, the decision was declared permanent.6 The lawsuit was one of many transformational events in the chiropractic profession that occurred during the 1970s and 1980s. Its completion in 1990 signaled the conclusion of some of the uncertainty within chiropractic. Although many of today's chiropractors are not aware of the trials, the final decision has shaped what chiropractic has become.

From the organizing of the plaintiffs and securing legal representation by McAndrews in 1975 to the final denial of appeals in 1990, 15 years had elapsed. This time allowed for some transformations in the chiropractic profession to occur that led up to the final decision, of which countless people contributed to substantial improvements over these years. The court decision was essential to remove the barrier for the chiropractic profession to move forward; however, the efforts behind the scenes by scores of people over the years were also important contributors to change. This was the end of one era and the beginning of another.

DISCUSSION

By the time the lawsuit was filed in 1976, the AMA had already ended its CoQ. By the year of the first trial (1980), the AMA had modified its Principles, thereby allowing medical physicians to practice with anyone they chose. Thus, the victory sealed in 1990 was not the action that caused the AMA to change its code of ethics regarding chiropractic.

Instead, these trials and judge's decision brought to light that the AMA was in violation of antitrust law and had been hampering chiropractic for nearly a century. The trials also revealed to what depth the AMA was involved with suppressing the growth of the chiropractic profession. The lawsuit and its successful conclusion demonstrated that organized, political medicine had a strong negative influence on other professions and covertly promoted its influence. The AMA had attempted to contain and eliminate a health profession using the argument that they were trying to protect the public's health. However, it was clear that they had violated antitrust law and that their intentions were not as pure as they had originally suggested.

The first trial by jury resulted in a crushing defeat for the chiropractic profession. Yet the plaintiffs and their lawyers persisted. As a legal strategy crafted by the lead lawyer, the second trial did not engage a jury but relied on the judge's decision. The focus of the case was not if chiropractic was effective and safe, as these were not factors within the court's power to adjudicate. Instead, the decision was about if the AMA violated antitrust law and if the situation would require an injunction.

The injunction could not make reparations and undo the many years of harm; it would only make public the prior AMA actions and ensure that they would not be allowed to continue these actions in the future. This injunction made it clear, at least to those who read or had access to the JAMA, that the AMA's boycott against chiropractic was over and that medical doctors and hospitals could choose to work with chiropractors if they wished to.