Abstract

Objective

This is the third paper in a series that explores the historical events surrounding the Wilk v American Medical Association (AMA) lawsuit in which the plaintiffs argued that the AMA, the American Hospital Association, and other medical specialty societies violated antitrust law by restraining chiropractors' business practices. The purpose of this paper is to provide a brief review of the history of the growth of chiropractic, its public relations campaigns, and infighting that contributed to the events surrounding the Wilk v AMA lawsuit.

Methods

This historical research study used a phenomenological approach to qualitative inquiry into the conflict between regular medicine and chiropractic and the events before, during, and after a legal dispute at the time of modernization of the chiropractic profession. Our methods included obtaining primary and secondary data sources. The final narrative recount was developed into 8 papers following a successive timeline. This paper is the third of the series that explores the growth the chiropractic profession.

Results

By the 1930s, the AMA was already under investigation for violation of antitrust laws and the National Chiropractic Association was suggesting that the AMA was establishing a health care monopoly. Chiropractic schools grew and the number of graduates rose quickly. Public relations campaigns and publications in the popular press attempted to educate the public about chiropractic. Factions within the profession polarized around differing views of how they thought that chiropractic should be practiced and portrayed to the public. The AMA leaders noted the infighting and used it to their advantage to subvert chiropractic.

Conclusion

Chiropractic grew rapidly and established its presence with the American public through public relations campaigns and popular press. However, infighting would give the AMA material to further its efforts to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession.

Keywords: Health Occupations; Chiropractic; Medicine; Humanities; History, 20th Century; Antitrust Laws

INTRODUCTION

Chiropractic grew quickly in the first part of the 20th century despite experiencing many challenges. There were multiple factions and leaders who were passionate about their own views of what the chiropractic profession was and what chiropractic should be. As well, strong opposition from the American Medical Association (AMA) developed substantial hurdles for the fledgling profession. Public perception of chiropractic was important as it was a driving force that helped support chiropractic legislation. Both medicine and chiropractic had public relations campaigns, including publications in the popular press that attempted to sway the thoughts of the American public. The battle for the public's opinion about chiropractic contributed to shaping the direction of the profession.

Since its beginning in 1847, the AMA had declared any health profession that was not “regular medicine” was quackery and endeavored to control its competition. Although medicine's opposition had been consistent and longstanding, events in the 1950s may have tempted the AMA to amplify its attack against chiropractic in the next decade. These events included (1) the growth in the number of chiropractors, (2) the expansion of chiropractic scope of practice, (3) the increasing popularity of chiropractic, and (4) the ever-increasing boldness of chiropractors to speak out against medicine. As a result, the AMA leaders strengthened their efforts and developed increasingly aggressive attacks, which ultimately led chiropractors to file the Wilk v AMA lawsuit.1

The historical events surrounding this lawsuit are important for chiropractors today because they help explain the surge in scientific growth2–21 and the improvement in access to chiropractic care for patients once barriers were removed.22–35 These events clarify chiropractic's previous struggles and how past experiences may influence current events. The obstacles and challenges that chiropractic overcame may help explain the current culture and help to identify issues that the chiropractic profession may need to address in the future.

The purpose of this paper is to provide a brief review of the history of the growth of chiropractic, its public relations campaigns, and infighting that contributed to the events surrounding the Wilk v AMA lawsuit. This paper describes the rise in the numbers of chiropractors in the United States and discusses some of the chiropractic infighting that the AMA would later use as a wedge to undermine chiropractic advancement.

METHODS

This historical study used a phenomenological approach to qualitative inquiry into the conflict between regular (orthodox) medicine and chiropractic and the events before, during, and after a legal dispute at the time of modernization of the chiropractic profession. The metatheoretical assumption that guided our research was a neohumanistic paradigm. As described by Hirschheim and Klein, “The neohumanist paradigm seeks radical change, emancipation, and potentiality, and stresses the role that different social and organizational forces play in understanding change. It focuses on all forms of barriers to emancipation - in particular, ideology (distorted communication), power, and psychological compulsions and social constraints - and seeks ways to overcome them.”36 We used a pragmatic and postmodernist approach to guide our research practices, such that objective reality may be grounded in historical context and personal experiences and interpretation may evolve with changing perspectives.37

We followed techniques described by Lune and Berg.38 These steps included identifying the topic area, conducting a background literature review, and refining the research idea. After this we identified data sources and evaluated the source materials for accuracy. Our methods included obtaining primary data sources: written testimony, oral interviews, public records, legal documents, minutes of meetings, newspapers, letters, and other artifacts. Information was obtained from publicly available collections on the internet, university archives, and privately owned collections. Secondary sources included scholarly materials from textbooks, and journal articles. The materials were reviewed, then we developed a narrative recount of our findings.

The manuscript was reviewed for accuracy, completeness, and content validity by a diverse panel of experts, which included reviewers from various perspectives within the chiropractic profession ranging from broad-scope (mixer) to narrow-scope (straight) viewpoints; chiropractic historians; faculty and administrators from chiropractic degree programs; corporate leaders; participants who delivered testimony in the trials; and laypeople who are chiropractic patients. The manuscript was revised based on the reviewers' feedback and returned for additional rounds of review. The final narrative recount was developed into 8 papers that follow a chronological storyline.39–45 This paper is the third of the series that considered events relating to the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession and explores chiropractic development in the mid-20th century and infighting within the profession.

RESULTS

Early Recognition of AMA Antitrust Actions

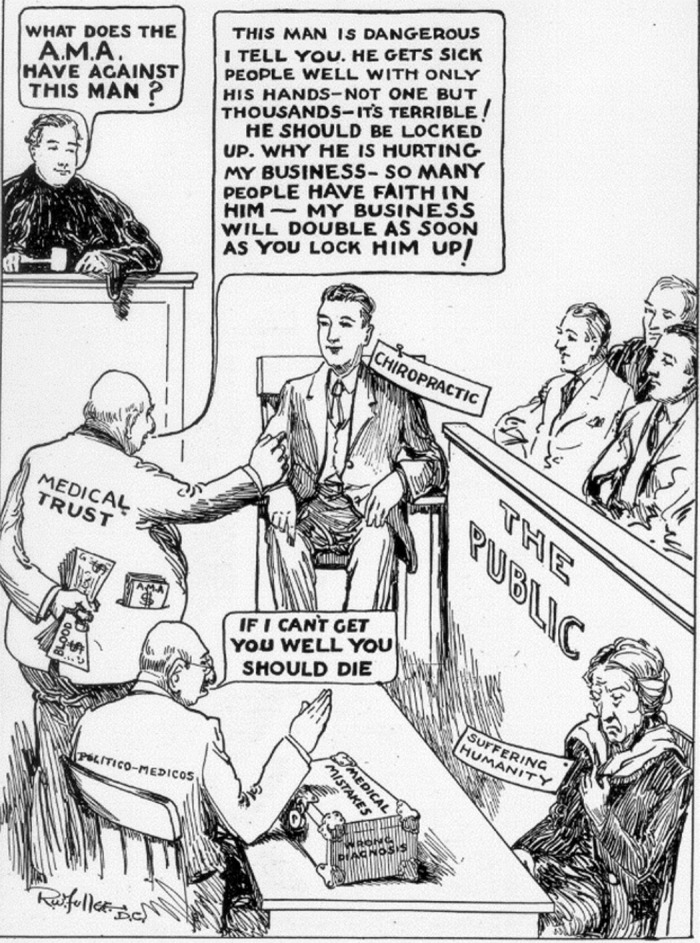

By the 1930s, the actions of organized medicine against other professions had been noticed by the federal government. The US Department of Justice investigated the AMA regarding claims that it was in violation of antitrust laws.46 The national chiropractic associations were aware that organized medicine was gaining control over health care in the United States. As early as 1938, the National Chiropractic Association (NCA) pointed out the concern for AMA dominance. The author of a cartoon claimed that this would be at the expense of the public's health and result in greater suffering of humanity (Fig. 1).47

Figure 1.

- A cartoon from the NCA's The Chiropractic Journal in 1938. “U.S. charges American Medical Association as health trust; AMA prevented patients from having doctors of their own choice; Department of Justice seeks criminal indictment for violation of anti-trust laws” (figure published with permission from ACA).

Chiropractic Growth in the United States

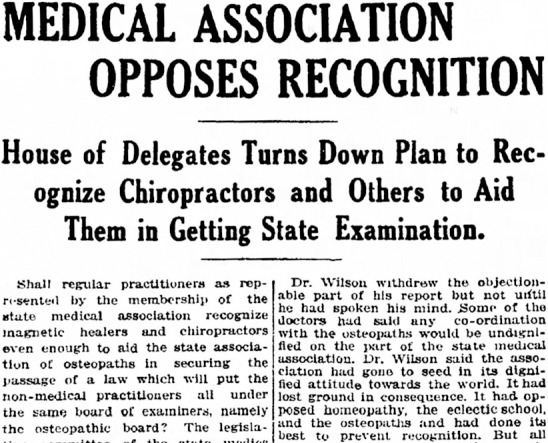

Despite the hostile environment, by midcentury the chiropractic profession continued to grow. The GI bill that followed World War II covered tuition for chiropractic programs for those returning from military service. Thousands of veterans took advantage of these grants to pursue a chiropractic career.48 Increasing numbers of chiropractic graduates spread across the country. At the same time, the quality of chiropractic education improved, and the chiropractic profession made progress on establishing its own professional accrediting agency so that students could receive federal loans. The NCA saw that expanding chiropractic scope allowed chiropractors to provide a wider variety of services to the public and was an opportunity to expand how chiropractic could serve the public. However, political medicine continued its campaign to contain any expansion (Fig. 2).49

Figure 2.

- An example of a battle against chiropractors at the state level. This article describes that regular practitioners (ie, orthodox medical physicians) were opposed to the recognition of chiropractors and fought against chiropractors from having their own licensing board. In this example, the state medical association wanted chiropractors to be required to pass an examination not before a chiropractic board, but instead, before a medical or osteopathic board. By maintaining control over state boards and examinations, orthodox medicine would be in control over the health care workforce and therefore who might enter as competitors.

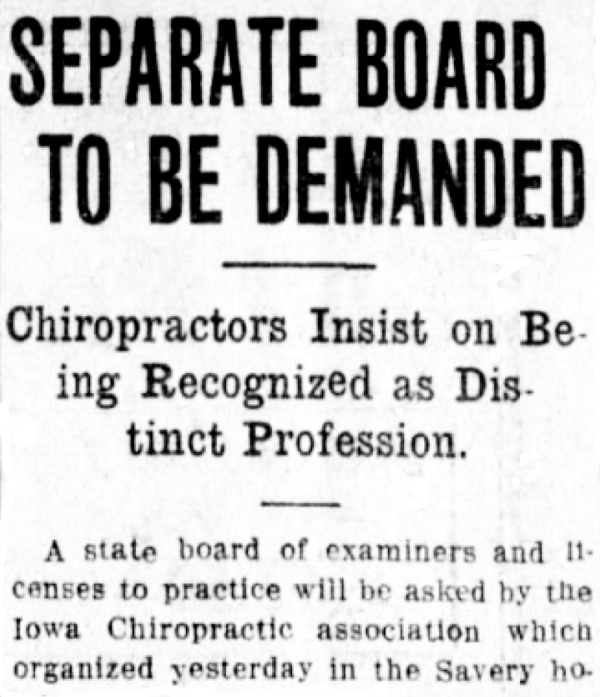

The NCA (which became the present-day American Chiropractic Association [ACA] in 1963) continued to press for legislation to expand the scope of chiropractic practice to include other modalities and practices in addition to adjusting chiropractic vertebral subluxations by hand. This push for expansion of chiropractic scope was seen as threatening to organized medicine. The AMA was paying attention to chiropractic and the subsequent medical discussions became more frequent about what to do about the “chiropractic problem.” The AMA leaders noticed that efforts from state and national chiropractic associations to establish chiropractic as a separate and distinct profession was showing success (Fig. 3).50

Figure 3.

- Mr Fred Hartwell, attorney for the Universal Chiropractors Association, advised chiropractors by saying, “You have got to stand your ground if you want the respect of the public” and recommended a distinct board of chiropractic that was separate from osteopathic or medical boards. When this statement was made (1914), there were an estimated 240 chiropractors in Iowa.

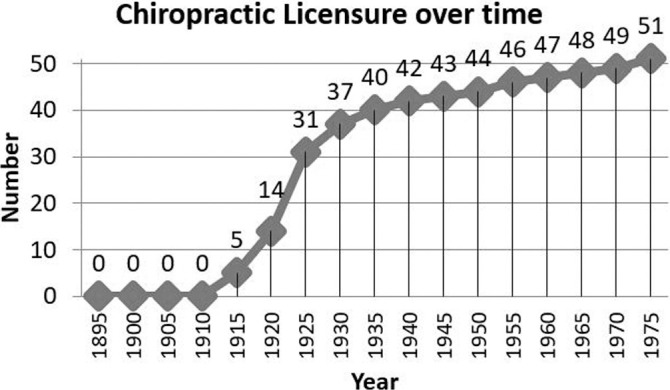

As more states legally recognized the chiropractic profession, chiropractic grew into the territories that organized medicine perceived to be its own. Because chiropractic was becoming a licensed profession, chiropractors practiced in those states without fear of prosecution regarding licensure. The profession that the AMA had earlier considered as a mere nuisance was becoming a more serious concern by the 1950s.51 If elimination was the desired outcome, the AMA seemed to have missed their opportunity to squelch chiropractic prior to the 1920s (Fig. 4) 52 since that was the decade that appeared to have been the pivotal time for chiropractic growth in the United States. Yet even with chiropractic growth, orthodox medicine remained dominant. By 1962, there were only about 12,000 to 14,000 licensed chiropractors compared to 250,000 medical doctors in the United States.

Figure 4.

- This chart shows the increasing number of states adopting chiropractic licensure over time; 51 jurisdictions including the District of Columbia. Between 1920 and 1930 there was an increase in momentum and a sharp increase in the number of states with chiropractic licensure (figure published with permission from Brighthall).

During the 1950s, leaders of both the International Chiropractors Association (ICA) and the NCA were aware of the continued efforts of the AMA to use its anti-quackery campaign to control health care in general. The October 1954 International Review of Chiropractic carried a critical analysis of an article published in The Yale Law Review on medical monopoly practices of the AMA.53

Skirmishes between medicine and chiropractic were becoming more common. Leaders from the NCA criticized the AMA's actions and policies in the Journal of the National Chiropractic Association. The AMA released a pamphlet about quacks in 1955 and the NCA ridiculed the AMA's attempts to root out quacks from the medical profession. The chiropractic article concluded by saying, “The AMA should be congratulated for bringing to the attention of the general public the dire need of a house-cleaning in the medical profession, and it behooves us as interested citizens to help spread this information to innocent people who are being bilked of their money.”54

Chiropractic Public Relations Campaigns

Throughout the 1950s, the AMA continued its attack on chiropractic in the public media. During this time, the chiropractic profession worked diligently to create its own marketing plans to enhance the legitimacy of chiropractic in the eyes of the American public. The ICA, the NCA, and the Canadian Chiropractic Association collaborated by holding joint conferences to enhance public relations for chiropractic.55,56 Chiropractic public relations programs included mass media, meetings with elected officials, and large-scale public education campaigns.57 These efforts included distributing information about how chiropractors could contribute in areas that organized medicine opposed chiropractic involvement. Two such areas were industrial and labor relations and chiropractic inclusion in the care of veterans through the US Department of Veterans Affairs.58

Chiropractic leaders knew that mass media was an effective marketing vehicle. They developed a national television series including celebrity spokespersons designed to raise the prestige of chiropractors in the eyes of the public.59 This series was first broadcast throughout the state of Iowa, the home of the NCA, the ICA, and the Iowa State Medical Society.59 The NCA released a Hollywood-produced movie about chiropractic for television broadcasting and radio recordings.60 Media coverage included broadcasts from CBS, Fox Movietone, and television talk shows.61

The national chiropractic associations encouraged chiropractors to inform local newspapers and radio stations of potential events of intrigue.60,62 They befriended radio, television, and newspaper reporters to disseminate chiropractic materials to the public,62 and local newspaper reporters to get the best coverage of chiropractic events.60 One director of public relations outlined procedures that chiropractors should follow when handling reporters for local and state meetings, including invitation etiquette, making reporters feel welcome at meetings, and other gestures of distinction.62 The NCA had a news service that promoted chiropractors who spoke nationally and that disseminated information about national conventions.

Elected officials were targeted to promote chiropractic. The NCA was successful in promoting an annual National Chiropractic Day on September 18, the day that DD Palmer was said to have performed the first chiropractic adjustment and thereby founding chiropractic (Fig. 5). For this day, the NCA recruited politicians to issue proclamations of National Chiropractic Day. Mayors, senators, and congressmen extolled the benefits of chiropractic in speeches, including in the US House of Representatives, and official proclamations, such as in the Congressional Record.63–65

Figure 5.

- Declaration in the Congressional Record for Chiropractic Day, 1952.

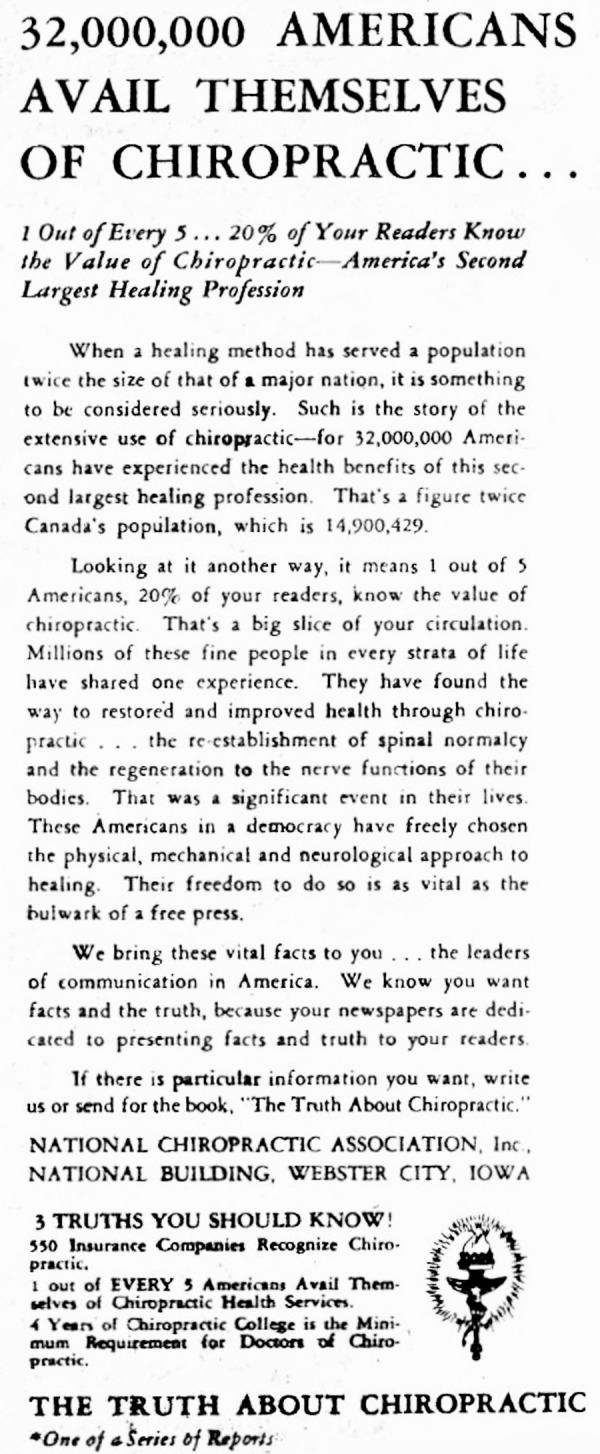

The NCA urged chiropractors to appeal to both old and young Americans to share the benefits of chiropractic.66 In 1955, the NCA distributed a series of educational advertisements called The Truth about Chiropractic, which described the popularity of chiropractic with Americans, the numbers of patients with diseases helped by chiropractic, and the breadth of inclusion of chiropractic in insurance companies and occupational injury programs (Fig. 6).67,68 These publications likely rankled the leadership of the AMA.

Figure 6.

- One of a series of NCA advertisements used to promote chiropractic to the American public (figure published with permission from American Chiropractic Association).

Chiropractic Popular Press

The NCA did their best with their limited resources, which faced the AMA's public relations budget, which was $400,000 in 1958.69 The NCA developed programs to educate through the popular press. For example, an issue of McCall's magazine (October 1959) published “The Case for Chiropractors!”70 that promoted chiropractors as health providers. Other articles represented chiropractors as experts in topics such as slipped disk, nervous tension, and other health-related issues, which challenged the AMA's position.71

In a combined effort, the NCA and ICA attempted to convince the public that a chiropractor was able to take care of all health concerns. A mass-produced book, Your Health and Chiropractic, stated that it contained “The Complete True Story of America's Fastest Growing and Most Controversial Healing Art.” The book was written for the lay public and purposely addressed controversial topics. Issues included explanations for why medicine was opposed to chiropractic and mentioned “organized medicine's private war against chiropractic.” This book also contained pictures of a patient receiving chiropractic adjustments.72

To increase outreach to the public, the NCA published a chiropractic magazine for the layperson, which was similar in concept to the AMA's magazine Hygiea. More than 146,000 copies of Healthways were published each month. Healthways clubs, consisting of laypeople, were formed. Club members could use the magazine to discuss community health issues promoted by the NCA. Each club member would pay $1 in dues and the NCA provided an annual subscription of Healthways through the members' chiropractor, a personalized club membership card that the chiropractor could give to each member, and a club certificate that could be mounted in the chiropractors' office where club meetings were held (Fig. 7).73,74

Figure 7.

- The 1956 September issue of Healthways, a publication created by the NCA to educate the public about chiropractic. This magazine contained articles on a wide range of health-related topics (figure published with permission from American Chiropractic Association).

The NCA Proclaims a New Definition of Chiropractic

In 1958, the NCA had the largest membership of any chiropractic organization, which included nearly 8000 chiropractors and chiropractic students combined.73 Considering that by 1960 there were just over 14,000 chiropractors in the United States,51 the NCA members comprised nearly 60% of the profession. Given this majority, successful implementation of the new NCA plans had the potential to secure substantial social influence in the United States.

The NCA proclaimed 1958 as “The Year of Decision”73 and declared NCA's integrated master plan to broaden the scope of chiropractic practice and to further promote chiropractic to the public. The goals included legislative activities, public relations campaigns, and growing the membership of the NCA. The purpose of this plan was to create a new national definition of chiropractic and scope of practice.69

This program aimed to socially legitimize and publicize the new vision of chiropractic, which included state-by-state lobbying with legislators to change licensure laws to include the NCA definition of chiropractic. The NCA hoped that passing such legislation throughout the United States would create a more uniform definition of chiropractic. The NCA also sought to standardize educational requirements for licensing in all states.69,73 The announcement of the NCA's new definition and aim to increase the scope of practice was not supported by the ICA.

Infighting and Attempts at Unity Between Chiropractic Associations

Disputes between the ICA and the NCA continued. The NCA legal counsel lamented that the lack of uniformity within chiropractic was a primary reason why the public did not understand chiropractic and that such disparity was “symptomatic of professional and organizational immaturity.”75 The NCA lawyer went on to say that chiropractic was part of the health care system:

Thus it is well established from a legal point of view that the practice of medicine includes the practice of allopathy, osteopathy, and chiropractic. Those who insist that chiropractic is not in any sense the practice of medicine have failed to present any substantial or persuasive reasons why this obsolete position should be maintained by the profession. I see no violence done to the profession or its principles by statutory or judicial reference to it as ‘chiropractic medicine' or to its doctors as ‘chiropractic physicians.'75

The ICA expressed different views about how chiropractic should be represented, which were in direct opposition to the NCA. The ICA stance wished to preserve the distinction between the profession of chiropractic and medicine and avoid any real or implied overlap with medical scope of practice.

Despite longstanding disagreements between some ICA and NCA officers, leaders of the ICA and NCA began discussing the possibility of unifying the 2 organizations into a single national chiropractic organization that represented all chiropractors in the United States.76–79 Their plans were widely published in the Journal of the NCA and the International Review of Chiropractic during 1962–1963. The plan was to create a new combined association, which would be named the American Chiropractic Association (ACA).

During these negotiations, the ICA proposed a definition and scope of chiropractic, which stated, “Chiropractic is the science which deals with the relationship between the articulations of the human body (especially the spine) and the nervous system and the role of these relationships in health and disease.” And, “Scope of Practice – The practice of chiropractic consists of the use of accepted scientific procedures for the purpose of locating, analyzing, corrections and adjusting the interference with nerve transmission and expression (especially of the spinal column) without prescribing drugs or performing operative surgery and to work in cooperation with all branches of the healing arts in order to make the best provisions for the benefits of chiropractic to the public.”80 The NCA rejected these proposed statements.

The NCA counterproposed a definition and scope of chiropractic, which the ICA rejected, that stated, “Chiropractic is a science of healing based on the premise that disease is caused by the abnormal functioning of the human nervous system,”73 and also included,

The practice of chiropractic consists of the diagnosing of human ailments by the use of all diagnostic procedures recognized by the various schools of the healing arts; the elimination of the abnormal functioning of the human nervous system by the adjustment of the articulations and adjacent tissue of the human body, particularly of the spinal column; the use, as indicated, of procedures which make the adjustment more effective, including clinical nutrition, psychotherapy and physiotherapy, but excluding the use of drugs and surgery.80

After years of difficult negotiations, the 2 organizations conceded that they were not able to come to a resolution to merge.77 After the debates that led to the dissolution of the NCA–ICA unification, some ICA members defected to the NCA. In late 1963, the NCA, new member recruits, and defectors from the ICA became the ACA.76,81 The new ACA represented the majority of the chiropractors in the early 1960s.76 Members who remained with the ICA became increasingly vocal in their opposition to the new ACA's activities.

The major factions within the chiropractic profession polarized around differing views of how they thought that chiropractic should be portrayed to the public. The AMA noted the infighting within chiropractic and used this information to its advantage to subvert chiropractic, which would later be revealed during the Wilk v AMA lawsuit.

DISCUSSION

The growth of chiropractic continued. By the time the AMA began to recognize that there was what they called a “chiropractic problem,” the number of chiropractors was substantial and a positive public perception of chiropractic as a health care option had already been established. The AMA and local medical societies observed the NCA's push for wider scope of practice and the chiropractic profession's efforts to raise the public's perception of chiropractic, which were perceived as threats.

Chiropractic schools grew and the number of graduates expanded as the GI bill helped to fund the education of service members returning from the war. Since chiropractors were not part of the medical healthcare system, the AMA would not allow them in medical hospitals; therefore, chiropractors had to resort to other means of informing patients about what chiropractic care could do. Increasing efforts to educate the public about what chiropractic care offered resulted in public health campaigns.

The chiropractic profession had various viewpoints of how to apply the art of chiropractic in practice. From the early years of development emerged 2 general views. This division would be used by the AMA to cripple chiropractors' efforts to create a protective stance. The lead attorney for the plaintiffs, Mr George McAndrews, described these 2 views of chiropractic in his opening statements to the jury during the first trial:

The straights have limited their practice by desire to manual manipulation of the spinal column and its related articulations. Those are on or near the spine. Ten finger laws, they call them. Some of the states require that. They use no or very few additional modalities.

A mixer takes that ten fingers and adds to it — the term “mixing,” adds to it this terminology. They utilize the physiotherapeutic modalities. In addition to their hands they will use such additional modalities as heat, hot packs, cold, ice packs, or electrical stimulation and light ... In many states they will give nutritional counseling ... They will perform a broader service than merely hand manipulation.82

Chiropractic was a young profession with a divided house. The ICA and NCA competed for members and thus tried to create their own unique brand of chiropractic. As more chiropractors graduated, the profession grew, which meant that the competing chiropractic factions also grew. Communications and actions from the differing national associations fought against each other attempting to gain a dominant role and competing for members. Chiropractic factions also competed against each other regarding legislation. This lack of unity and differing messages often left those in the US government, policy makers, and the public confused.

The AMA noticed the infighting and considered chiropractors' unwillingness to establish a common front as a weakness. The AMA leadership used this information to attempt more aggressive and clandestine methods to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession in the years ahead.

Limitations

This historical narrative reviews events from the context of the chiropractic profession and the viewpoints are limited by the authors' framework and worldview. Other interpretations of historic events may be perceived differently by other authors. The context of this paper must be considered in light of the authors' biases as licensed chiropractic practitioners, educators, and scientific researchers.

The primary sources of information were written testimony, oral interviews, public records, legal documents, minutes of meetings, newspapers, letters, and other artifacts. These formed the basis for our narrative and timeline. We acknowledge that recall bias is an issue when referencing sources, such letters, where people recount past events. Secondary sources, such as textbooks, trade magazines, and peer-reviewed journal articles, were used to verify and support the narrative. We collected thousands of documents and reconstructed the events relating to the Wilk v AMA lawsuit. Since no electronic databases exist that index many of the publications needed for this research, we conducted page-by-page hand searches of decades of publications. While it is possible that we missed some important details, great care was taken to review every page systematically for information. It is possible that we missed some sources of information and that some details of the trials and surrounding events were lost in time. The aforementioned potential limitations may have affected our interpretation of the history of these events.

Some of our sources were interviews, manuscripts, or letters where the author recalled past events. Recall bias is an issue when referencing interview sources. Surviving documents from the first 80 years of the chiropractic profession, the years leading up to the about the Wilk v AMA lawsuit are scarce. Chiropractic literature existing before the 1990s is difficult to find since most of it was not indexed. Many libraries have divested their holdings of older material, making the acquisition of early chiropractic documents challenging. While we were able to obtain some sources from libraries, we also relied heavily upon material from our own collection and materials from colleagues. Thus, there may be relevant papers or artifacts that were inadvertently missed. Our interpretation of the events related to the trials is limited to the materials available. The information regarding this history is immense and due to space limitations, not all parts of the story could be included in this series.

CONCLUSION

Chiropractic grew rapidly and established a presence with the American public through public relations campaigns and popular press. These activities, the increasing numbers of chiropractors, and scope of chiropractic practice, raised the AMA's concern about chiropractic. However, infighting between chiropractic associations gave the AMA opportunities to further its efforts to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the following people for their detailed reviews and feedback during development of this project: Ms Mariah Branson, Dr Alana Callender, Dr Cindy Chapman, Dr Gerry Clum, Dr Scott Haldeman, Mr Bryan Harding, Mr Patrick McNerney, Dr Louis Sportelli, Mr Glenn Ritchie, Dr Eric Russell, Dr Randy Tripp, Mr Mike Whitmer, Dr James Winterstein, Dr Wayne Wolfson, and Dr Kenneth Young.

FUNDING AND CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

This project was funded, and copyright owned by NCMIC. The views expressed in this article are only those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of NCMIC, National University of Health Sciences, or the Association of Chiropractic Colleges. BNG is the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Chiropractic Education and CDJ is on the NCMIC board and the editorial board of the Journal of Chiropractic Education. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wilk et al v American Medical Association et al Nos. 87-2672, 87–2777 895 F.2d 352 (7th Cir. 1990), (United States Court Of Appeals For The Seventh Circuit 1990)

- 2.Haldeman S, Chapman-Smith D, Petersen DM. Guidelines for Chiropractic Quality Assurance and Practice Parameters proceedings of the Mercy Center Consensus Conference. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishing; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson C. What is the Association of Chiropractic Colleges Educational Conference and Research Agenda Conference? J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30(4):249–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson C, Green B. The Association of Chiropractic Colleges Educational Conference and Research Agenda Conference: 17 years of scholarship and collaboration. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33(3):165–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mootz RD, Hansen DT, Breen A, Killinger LZ, Nelson C. Health services research related to chiropractic: review and recommendations for research prioritization by the chiropractic profession. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(9):707–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haas M, Bronfort G, Evans RL. Chiropractic clinical research: progress and recommendations. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(9):695–706. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mrozek JP, Till H, Taylor-Vaisey AL, Wickes D. Research in chiropractic education: an update. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(9):762–773. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cramer G, Budgell B, Henderson C, Khalsa P, Pickar J. Basic science research related to chiropractic spinal adjusting: the state of the art and recommendations revisited. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(9):726–761. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bigos SJ, Bowyer OR, Braen GR, et al. Acute low back problems in adults. Acute Lower Back Problems in Adults. Clinical Practicei Guidelines No. 14. AHCPR Publication No. 95-0642. Rockville Md US Dept of Health and Human Services Public Health Service Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1994.

- 10.Haldeman S, Carroll L, Cassidy JD, Schubert J, Nygren A. The Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders: executive summary. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(2 Suppl):S7–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson C, Baird R, Dougherty PE, et al. Chiropractic and public health: current state and future vision. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(6):397–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson C, Green BN. Public health, wellness, prevention, and health promotion: considering the role of chiropractic and determinants of health. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(6):405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egan J, Baird R, Killinger L. Chiropractic within the American Public Health Association, 1984–2005: pariah, to participant, to parity. Chiropr Hist. 2006;26:97–117. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haldeman S, Nordin M, Chou R, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: World Spine Care executive summary on reducing spine-related disability in low- and middle-income communities. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(Suppl 6):776–785. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5722-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green BN, Johnson CD, Haldeman S, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: public health and prevention interventions for common spine disorders in low- and middle-income communities. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(Suppl 6):838–850. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5635-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson CD, Haldeman S, Nordin M, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: methodology, contributors, and disclosures. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):786–795. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5723-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haldeman S, Johnson CD, Chou R, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: care pathway for people with spine-related concerns. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):901–914. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5721-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haldeman S, Johnson CD, Chou R, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: classification system for spine-related concerns. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):889–900. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5724-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson CD, Haldeman S, Chou R, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: model of care and implementation. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):925–945. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5720-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green BN, Johnson CD, Haldeman S, et al. A scoping review of biopsychosocial risk factors and co-morbidities for common spinal disorders. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0197987. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keating JC, Jr, Green BN, Johnson CD. “Research” and “science” in the first half of the chiropractic century. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1995;18(6):357–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boon H, Verhoef M, O'Hara D, Findlay B, Majid N. Integrative healthcare: arriving at a working definition. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004;10(5):48–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawk C, Nyiendo J, Lawrence D, Killinger L. The role of chiropractors in the delivery of interdisciplinary health care in rural areas. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1996;19(2):82–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lott CM. Integration of chiropractic in the Armed Forces health care system. Mil Med. 1996;161(12):755–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Branson RA. Hospital-based chiropractic integration within a large private hospital system in Minnesota: a 10-year example. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):740–748. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green BN, Johnson CD, Lisi AJ, Tucker J. Chiropractic practice in military and veterans health care: the state of the literature. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2009;53(3):194–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boon HS, Mior SA, Barnsley J, Ashbury FD, Haig R. The difference between integration and collaboration in patient care: results from key informant interviews working in multiprofessional health care teams. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dunn AS, Green BN, Gilford S. An analysis of the integration of chiropractic services within the United States military and veterans' health care systems. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):749–757. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldberg CK, Green B, Moore J, et al. Integrated musculoskeletal rehabilitation care at a comprehensive combat and complex casualty care program. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):781–791. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lisi AJ, Goertz C, Lawrence DJ, Satyanarayana P. Characteristics of Veterans Health Administration chiropractors and chiropractic clinics. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46(8):997–1002. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2009.01.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hawk C. Integration of chiropractic into the public health system in the new millennium. In: Haneline MT, Meeker WC, editors. Introduction to Public Health for Chiropractors. Boston: Jones and Bartlett; 2010. pp. 375–389. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green BN, Johnson CD, Daniels CJ, Napuli JG, Gliedt JA, Paris DJ. Integration of chiropractic services in military and veteran health care facilities: a systematic review of the literature. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2016;21(2):115–130. doi: 10.1177/2156587215621461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salsbury SA, Goertz CM, Twist EJ, Lisi AJ. Integration of doctors of chiropractic into private sector health care facilities in the United States: a descriptive survey. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018;41(2):149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Green BN, Johnson CD. Interprofessional collaboration in research, education, and clinical practice: working together for a better future. J Chiropr Educ. 2015;29(1):1–10. doi: 10.7899/JCE-14-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson C. Health care transitions: a review of integrated, integrative, and integration concepts. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):703–713. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirschheim R, Klein HK. Four paradigms of information systems development. Commun ACM. 1989;32(10):1199–1216. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Porra J, Hirschheim R, Parks MS. The historical research method and information systems research. J Assoc Info Syst. 2014;15(9):3. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lune H, Berg BL. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. Harlow, UK: Pearson; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 2: Rise of the American Medical Association. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):25–44. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-23. https://doi.org/10.7899/JCE-21-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 1: Origins of the conflict. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):9–24. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-22. https://doi.org/10.7899/JCE-21-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 4: Committee on Quackery. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):55–73. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-25. https://doi.org/10.7899/JCE-21-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 5: Evidence exposed. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):74–84. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-26. https://doi.org/10.7899/JCE-21-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 6: Preparing for the lawsuit. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):85–96. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-27. https://doi.org/10.7899/JCE-21-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession Part 7: Lawsuit and decisions. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;2021(S1):97–116. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-28. https://doi.org/10.7899/JCE-21-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 8: Judgment impact. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):117–131. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-29. https://doi.org/10.7899/JCE-21-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosenheck J. The American Medical Association and the antitrust laws. Fordham Law Review. 1939;8(1):82. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fuller R. Cartoon. The Chiropractic Journal. 1938;7(1):20. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Green BN, Johnson CD, Dunn AS. Chiropractic in veterans' healthcare. In: Miller T, editor. Veterans Health Resource Guide. Santa Barbara, California: Praeger Publishing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Medical association opposes recognition. Lincoln Journal Star. 1914. May 12. 1.

- 50.Separate board to be demanded. QuadCity Times. 1914. April 20. 7.

- 51.Smith-Cunnien SL. A Profession of One's Own Organized Medicine's Opposition to Chiropractic. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Federation of Chiropractic Licensing Boards. Chiropractic Regulatory Boards. 2019 https://www.fclb.org/Boards.aspx Published 2019. Accessed October 6.

- 53.The Yale article: AMA monopoly scored. Int Rev Chiropr. 1954;9(4) [Google Scholar]

- 54.American Medical Association cleans house. J Natl Chiropr Assoc. 1955;25(2):73. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Resolution for unified PR program adopted unanimously by delegates at sixth annual conference. Int Rev Chiropr. 1955;9(10):4–7. 42. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Joint public relations conference. Int Rev Chiropr. 1956;10(7):4. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anderson R, Leone J. Cooperation at the PR level. Int Rev Chiropr. 1955;9(12):10–11. 24. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Joint PR program is continued. Int Rev Chiropr. 1957;11(9):6–10. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mendy P. Producing a TV series for chiropractic. Int Rev Chiropr. 1957;11(10):6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murphy EJ. The needs and purposes of chiropractic public relations III. J Natl Chiropr Assoc. 1955;25(5) [Google Scholar]

- 61.Womer W. Illinois Chiropractic Society sponsors excellent public relations program. J Natl Chiropr Assoc. 1955;25(6) [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murphy EJ. The needs and purposes of chiropractic public relations IV. J Natl Chiropr Assoc. 1955;55(6) [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hopkins WH. Observance of chiropractic day points way to increased practice and prestige. J Natl Chiropr Assoc. 1955;25(9):13–14. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lovre HO. Annual chiropractic day. Congressional Rec. 1955. August 1.

- 65.Johnson CD. Chiropractic Day: a historical review of a day worth celebrating. J Chiropr Humanit. 2020;27:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.echu.2020.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Murphy EJ. The needs and purposes of chiropractic public relations VI. J Natl Chiropr Assoc. 1955;25(10) [Google Scholar]

- 67.The National Chiropractic Association sponsors second series of educational advertisements. J Natl Chiropr Assoc. 1955;25(11):42–43. [Google Scholar]

- 68.32 000000 Americans Avail Themselves of Chiropractic. 1955. Webster City, Iowa: National Chiropractic Association.

- 69.Report on the first national seminar on chiropractic public relations. J Natl Chiropr Assoc. 1958;28(8):9–11. 73. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grafton S. The Case for Chiropractors! McCall's Magazine. 1959. In.

- 71.Throckmorton RB. The Menace of Chiropractic. North Central Medical Conference; November 11, 1962. Minneapolis, MN.

- 72.Your Health and Chiropractic to be released in June. Int Rev Chiropr. 1957;11(12):10. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Achenbach H. High lights of the national chiropractic convention in Miami Beach, Florida. J Natl Chiropr Assoc. 1958;28(8) [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cover of Healthways magazine. Healthways. Sep, 1956. front cover.

- 75.Bunker JE. Chiropractic: an approach to definition. J Natl Chiropr Assoc. 1962;34(2):23–25. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Keating JC. The gestation and difficult birth of the American Chiropractic Association. Chiropr Hist. 2006;26(2):91–126. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Griffin LK. Merger almost: ICA unity efforts and formation of the American Chiropractic Association. Chiropr Hist. 1988;8(2):18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thaxton JQ. Profession finds common ground for unity. Int Rev Chiropr. 1962;17(1):4–5. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thaxton JQ. Unity of principle: the essential step toward progress. Int Rev Chiropr. 1962;16(11):4–5. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Unity talks hit snag. Int Rev Chiropr. 1957;12(6):10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Plamondon RL. Mainstreaming chiropractic: Tracing the American Chiropractic Association. Chiropr Hist. 1993;13(2):30–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Transcript of proceedings, December 1980, First Trial. 1980. In.