Abstract

Objective

This is the fourth article in a series that explores the historical events surrounding the Wilk v American Medical Association (AMA) lawsuit, in which the plaintiffs argued that the AMA, the American Hospital Association, and other medical specialty societies violated antitrust law by restraining chiropractors' business practices. The purpose of this article is to provide a brief review of the history of the origins of AMA's increased efforts to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession and the development of the Chiropractic Committee, which would later become the AMA Committee on Quackery.

Methods

This historical research study used a phenomenological approach to qualitative inquiry into the conflict between regular medicine and chiropractic and the events before, during, and after a legal dispute at the time of modernization of the chiropractic profession. Our methods included obtaining primary and secondary data sources. The final narrative recount was developed into 8 articles following a successive timeline. This article is the fourth of the series that explores the origins of AMA's increased efforts to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession.

Results

In the 1950s, the number of chiropractors grew in Iowa, and chiropractors were seeking equity with other health professions through legislation. In response, the Iowa State Medical Society created a Chiropractic Committee to contain chiropractic and prompted the creation of the “Iowa Plan” to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession. The AMA leadership was enticed by the plan and hired the Iowa State Medical Society's legislative counsel, who structured the operation. The AMA adopted the Iowa Plan for nationwide implementation to eradicate chiropractic. The formation of the AMA's Committee on Chiropractic, which was later renamed the Committee on Quackery (CoQ), led overt and covert campaigns against chiropractic. Both national chiropractic associations were fully aware of many, but not all, of organized medicine's plans to restrain chiropractic.

Conclusion

By the 1960s, organized medicine heightened its efforts to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession. The intensified campaign began in Iowa and was adopted by the AMA as a national campaign. Although the meetings of the AMA committees were not public, the war against chiropractic was distributed widely in lay publications, medical sources, and even chiropractic journals. Details about events would eventually be more fully revealed during the Wilk v AMA trials.

Keywords: Health Occupations; Chiropractic; Medicine; Humanities; History, 20th Century; Antitrust Laws

INTRODUCTION

By the 1950s, the number of chiropractors in the United States continued to increase. Of special historical importance, it was estimated that there was 1 chiropractor to every 4 medical doctors in Iowa. The national headquarters for both the National Chiropractic Association (NCA) and the International Chiropractors Association (ICA) were in Iowa, making chiropractic political activity and fighting between these associations highly visible in that state. The Iowa State Medical Society (ISMS) and others in organized medicine were aware of the NCA's master plan that proposed legislative activities, expansion of the scope of chiropractic practice, public relations campaigns, and efforts to grow its membership.

The leadership of the American Medical Association (AMA) was becoming increasingly concerned about the drop in AMA membership. There were also complaints that some medical doctors were openly working with chiropractors, despite the AMA code that forbade this activity. With the increasing pressure from chiropractic associations to either expand the scope of practice or have parity with medical doctors, medical associations' leadership reacted to these activities as perceived threats into medical territory and took aggressive action against chiropractors.1

These historical events surrounding this lawsuit are important for chiropractors today, because they help explain the surge in scientific growth2–21 and the improvement in access to chiropractic care for patients once barriers implemented by the AMA were removed.22–35 These events clarify chiropractic's previous struggles and how past experiences may be influencing current events. The obstacles and challenges that chiropractic overcame may help explain the current culture and help to identify issues that the chiropractic profession may need to address into the future.

The purpose of this article is to explore the origins of AMA's increased efforts in the 1950s and 1960s to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession, which were revealed in the Wilk v AMA lawsuit.36 This article discusses organized medicine's increasing efforts to suppress chiropractic and the AMA's plan to eradicate chiropractic by establishing the AMA's CoQ.

METHODS

This historical study used a phenomenological approach to qualitative inquiry into the conflict between regular (orthodox) medicine and chiropractic and the events before, during, and after a legal dispute at the time of modernization of the chiropractic profession. The meta-theoretical assumption that guided our research was a neohumanistic paradigm. As described by Hirschheim and Klein, “The neohumanist paradigm seeks radical change, emancipation, and potentiality, and stresses the role that different social and organizational forces play in understanding change. It focuses on all forms of barriers to emancipation-in particular, ideology (distorted communication), power, and psychological compulsions and social constraints-and seeks ways to overcome them.”37 We used a pragmatic and postmodernist approach to guide our research practices, such that objective reality may be grounded in historical context and personal experiences, and interpretation may evolve with changing perspectives.38

We followed techniques described by Lune and Berg.39 These steps included identifying the topic area, conducting a background literature review, and refining the research idea. Following this, we identified data sources and evaluated the source materials for accuracy. Our methods included obtaining primary data sources: written testimony, oral interviews, public records, legal documents, minutes of meetings, newspapers, letters, and other artifacts. Information was obtained from publicly available collections on the internet, university archives, and privately owned collections. Secondary sources included scholarly materials from textbooks and journal articles. The materials were reviewed, and then we developed a narrative recount of our findings.

The article was reviewed for accuracy, completeness, and content validity by a diverse panel of experts, which included reviewers from various perspectives within the chiropractic profession ranging from broad-scope (mixer) to narrow-scope (straight) viewpoints, chiropractic historians, faculty and administrators from chiropractic degree programs, corporate leaders, participants who delivered testimony in the trials, and laypeople who are chiropractic patients. It was revised based on the reviewers' feedback and returned for additional rounds of review. The final narrative recount was developed into 8 articles that follow a chronological storyline.1,40–45 This article is the fourth of the series that considers events relating to the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession and explores the origins of AMA's increased efforts to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession.

RESULTS

ISMS Creates a Chiropractic Committee

To address the increasing threat of chiropractic expansion, in 1955 the ISMS formed a Chiropractic Committee to contain chiropractic. The first attendees of the Chiropractic Committee meetings included Mr Doyl Taylor (ISMS executive secretary) and Mr Robert Throckmorton (ISMS legislative counsel). The Journal of the ISMS (JISMS) reported that “the Committee's chief aim is to obtain facts and to recommend policies regarding the two groups of chiropractors in the state.”46 The ISMS Chiropractic Committee members had concerns about chiropractors expanding their privileges and making “inroads into the practice of medicine.”47 They were also concerned that the legislation proposed by the NCA would revise the chiropractic scope of practice in Iowa and would allow chiropractors to use modalities. Because of these fears, Throckmorton was assigned to work with the ISMS Chiropractic Committee to “control the chiropractic problem.”47

In 1955, a law was proposed that would have allowed chiropractors to have similar rights, duties, and obligations as medical physicians. The proposal included the expansion of chiropractic scope beyond limiting chiropractors to only spinal adjustments by hand by including the use of physiotherapeutic modalities but without including drugs or surgery. The ISMS successfully lobbied and defeated this proposal in the Iowa state legislature.48

Following this defeat, in 1956, the Iowa Chiropractors' Association sought a legal solution by filing a lawsuit that aimed to recognize chiropractors as equals with medical doctors (MDs) and doctors of osteopathy within the State Department of Health.48,49 The lawsuit was described in an Iowan paper in the following manner:

To the “straights”, chiropractic involves the hand manipulation of the spinal column and nothing more. “Mixers” would adopt “quasi-medical” methods of diagnosis and treatment and believe that present Iowa law (which conforms to the “straight” position) unfairly hamstrings the profession. In the 1955 general assembly, the “mixers” waged an unsuccessful fight, in the face of opposition from the “straights” and the state medical society, to liberalize the chiropractic act. Now the chiropractors association and six of its members have petitioned the Polk county district court to declare that, in certain respects, a chiropractor is a “physician” in the same sense as an osteopath or a medical doctor. If the “mixers” should win an affirmative judgment, the chiropractors could, among other things, participate in public health programs now barred to them and a chiropractor could be appointed state commissioner of health.50

The ISMS also intervened in this lawsuit. In response to chiropractic efforts for parity, the ISMS president warned, “Certainly every physician should be alert and should do all he can to prevent any inroad by that cult.”51

The 1957 report from the ISMS's Chiropractic Committee showed that the ISMS members had concerns about chiropractic not only at a local level but also at a national level, including in its parent organization, the AMA. The Chiropractic Committee report stated,

Information on the scope of the cult, on its background and growth, and on the effectiveness of the efforts made to combat its rise elsewhere in the nation have been secured from nearly every state, and voluminous materials has been secured from the AMA Council on Medical Service. In addition, the members were able individually to secure a great deal of literature, particularly from various ones of the chiropractic schools around the country.47

The ISMS focused its efforts on suppressing and controlling chiropractic's scope of practice and the chiropractic profession's identity in Iowa. The ISMS members were concerned that the public would become confused about which type of health care provider they were visiting:

...there are places where the public has become so confused that it fails to distinguish a ‘doctor' of chiropractic from a doctor of medicine. Furthermore, the Committee is alarmed over the fact that many M.D.'s in Iowa apparently are unaware of the seriousness of the situation and of the increasingly numerous attempts that chiropractors are making to gain power not only at the state level but nationally.47

The 1958 ISMS report described their increasing concerns about how chiropractic was a threat to medicine's territory:

Chiropractic Problem. There is a continuing effort on the part of chiropractors to expand their activities and their scope of practice. Recently an effort was made by a chiropractic nursing home to obtain a license as a hospital for the purpose of taking care of patients with psychiatric illness. Additional efforts like this one and further attempts to expand their present scope of practice are anticipated during the coming session of the Legislature.52

The ISMS Chiropractic Committee members recommended several actions. The committee report noted that other states had “stringent laws curtailing or prohibiting chiropractic procedures and healing cults.”53 The committee was concerned that if the proposed bill were to be adopted through the legislature, the ISMS would be “negligent in our responsibility to the health and welfare of the citizens of this state.”53 The Chiropractic Committee began a campaign to oppose the chiropractors through lobbying state legislators. They also recommended an ISMS public relations program to spread information “as to cults, quacks and chiropractors.”53

The ISMS Chiropractic Committee developed a pamphlet of the collected information to be used in “a public relations program against the chiropractors on a state-wide basis” and to have the ISMS attorneys vigorously combat all efforts of chiropractors in legislation and in the courts when trying to expand chiropractic scope of practice.53 The ISMS increased its surveillance of and recommendations to halt the progress of chiropractic in Iowa. The ISMS deployed Throckmorton to liaison with state legislators on potential chiropractic legislation.47 By 1957, ISMS leadership decided that chiropractic activity was so threatening that the ISMS stated the situation was “an emergency” and raised its dues to account for the increased costs associated with its increasingly expensive offensive against chiropractic.54

ISMS Plans to Contain and Eliminate Chiropractic

In 1959, the ISMS made its first proclamation of its plan to contain and then eliminate chiropractic in Iowa. The ISMS considered that if the 2 national chiropractic associations were to work in unison, they would be a considerable opponent. The ISMS also feared that the NCA and ICA would merge, thereby creating a stronger chiropractic force in Iowa to expand chiropractic into the field of medicine. The chair of the ISMS chiropractic committee wrote, “The ISMS in the past has followed a policy of containment toward chiropractic and has made no attempt to eradicate it.” He recommended that the ISMS follow 2 more aggressive courses of action aimed at controlling chiropractic:

If the policy of containment is not successful a more aggressive policy be pursued.

That the ISMS be authorized to take whatever steps may become necessary, on a legislative and public relations front, to protect the interest of the public against any group or groups of untrained, unqualified cultists, quacks, and chiropractors who are seeking to enhance and broaden their scope of practice into the practice of medicine.55

The ISMS was determined to fight all expansion of chiropractic in Iowa and issued a special section written for the layperson in its September 1960 JISMS titled “In the Public Interest.” This ISMS propaganda argued that if chiropractors were allowed to expand their scope “into medicine,” it would be bad for the health of the public. The document was aimed at swaying voters in the direction of the ISMS position on chiropractic. It further alleged that chiropractic education was inferior in Iowa and that chiropractors had no training to allow such an expansion of chiropractic scope. The document concluded that chiropractic should be “kept out of medicine's basement.”56

In 1961, the ISMS changed its name to the Iowa Medical Society (IMS). Although it continued to publish its strategies to contain chiropractic, these notices dwindled as the plans were becoming more covert. Only 2 reports of the IMS chiropractic committee appeared in the society's journal, now known as the Journal of the Iowa Medical Society (JIMS). By 1962, it seemed that the IMS had become even more concerned and moved to more aggressive action.57 The committee reported, “During the past few years the present committee has felt justified in recommending a policy of containment and watchful waiting, but chiropractic activities in the past eight or nine months force us to reconsider our previous thinking and conclusions.”58 The society minutes included a foreboding message about the chiropractic profession. The committee report continued,

It is predictable that merger of the two chiropractic groups (mixers and straights) is inevitable. Unification of chiropractors will result in a stronger organization with a louder voice demanding further recognition and a broadening of the sphere of their activities. Evidence as of now points toward this conclusion on state, national and even Canadian levels.58

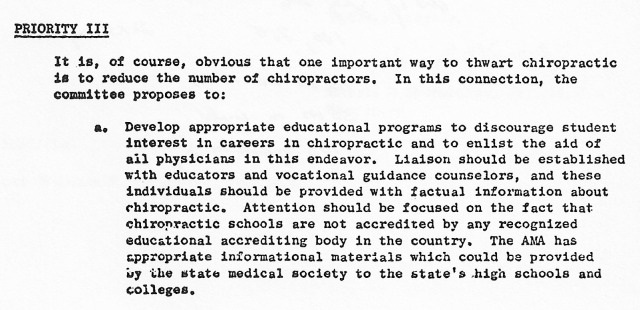

Following this, the IMS attempted to further contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession. The IMS activities were published in the JISMS and JIMS, thereby making the society's agenda readily available. The chiropractic profession was fully aware of what was going on with the IMS; both the ICA and NCA had been notified of the IMS plan. The ICA reproduced in the January 1958 issue of the International Review of Chiropractic the full IMS announcement of its new Chiropractic Committee. The authors of the brief in the ICA's Review stated, “Iowa MDs read the riot act.”59 The IMS continued to monitor chiropractic activities through its Chiropractic Committee. By 1962, their report in the journal suggested that they would be seeking more aggressive actions (Fig. 1).57

Figure 1.

- The Iowa Medical Society's journal included a “Chiropractic Committee” report that foreshadowed future actions that would be taken against chiropractors, not only in the state of Iowa but across the nation. They were concerned that the chiropractic profession wanted to be “an accepted scientific branch of the healing arts.”

AMA's Increasing Concern About Chiropractic

While these events were happening in Iowa, the AMA leaders were becoming increasingly concerned about the encroachment of chiropractic into the national field of medicine. By the late 1950s, chiropractors had improved their education, expanded their scope of practice, launched a successful mass media public relations campaign, and showed a consistent increase in the number of licensed doctors of chiropractic. By 1961, the AMA represented 179,000 of the 249,000 licensed physicians in the United States,60 and its income was reaching $15 million per year based on dues and advertising revenue from the AMA publications. These numbers would be threatened if chiropractic continued to grow. The AMA leadership noted that activities by some medical doctors, such as referring patients to chiropractors despite the AMA code of ethics, were undermining efforts to maintain the medical monopoly of health care services.61 In the early 1960s, the AMA became more assertive in collecting information about the chiropractic profession in order to contain its growth.

Chiropractic leaders and chiropractic practitioners were fully aware of the intentions of the AMA to increase its battle against chiropractic and to label chiropractors as “quacks.” Volleys between the leadership of the NCA and AMA increased in intensity in the early 1960s. The AMA and the Food and Drug Administration held the First National Congress on Medical Quackery in 1961. Although they included many forms of questionable health practices such as gadgets and nostrums from nonchiropractic sources, the AMA broadcast a decidedly negative image of chiropractic to the conference attendees and to the public. The presentation was released to media services, including newspapers, television, and radio.62 The AMA announced that it was beginning an extensive program of public education against the chiropractic profession through all communications media. Oliver Field, a member of the AMA's Bureau of Investigation, stated publicly his intention to discourage potential students from enrolling in chiropractic colleges and to dissuade patients from seeing chiropractors.62,63

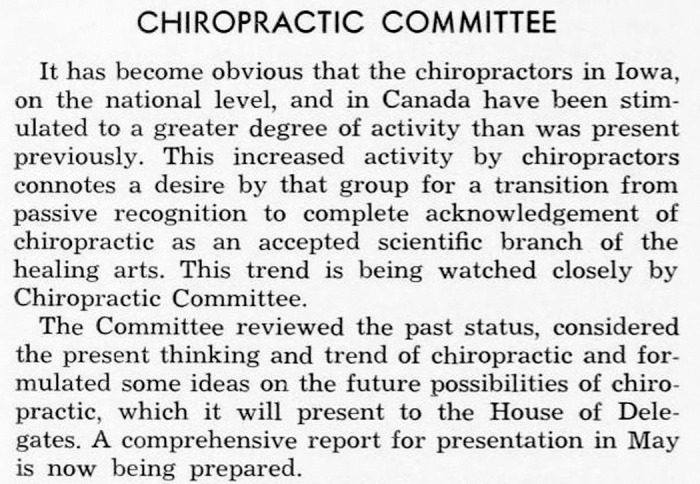

The NCA was fully aware of the AMA activities. Two leaders of the NCA attended the First National Congress on Medical Quackery and reported that 2 AMA representatives presented chiropractic as a form of “legalized quackery and inferred that it should be eliminated.”62,63 Aggressive volleys between the AMA and NCA continued to intensify in the early months of 1962. FJL Blasingame, MD, the executive vice-president of the AMA, distributed a 9-question survey to officers of state and county medical societies to collect adverse information about chiropractic from medical doctors (Fig. 2).64

Figure 2.

- The NCA's journal reproduced a letter that Dr Blasingame distributed to all medical associations in 1961. The aim of the letter was to gather information that the American Medical Association could use to eliminate chiropractors. Since this was included in a chiropractic publication, chiropractors were fully aware of these measures that the American Medical Association was using to attack chiropractic.

The NCA leadership obtained a copy of the AMA survey and reprinted it in its entirety in the January 1962 issue of the Journal of the NCA. Following this, the NCA unleashed a full-scale counterattack against the AMA. The Journal of the NCA editor stated:

Since the AMA is attempting to determine the extent of quack practices in the chiropractic profession by contacting the medical profession, the NCA will attempt to determine the extent of quack practices in the medical profession by contacting the chiropractic profession.62

The NCA counterattack included a much lengthier 38-question survey of the chiropractic profession that attacked medicine and asked chiropractors to send the completed survey to the NCA's Department of Investigation. The author concluded, “We regret the necessity of engaging in a battle of statistics with the AMA, but they have left us no other alternative in self-protection.”65 The NCA survey was printed in its entirety in the Journal of the NCA immediately following Blasingame's survey.66 This retort amplified the conflict between the 2 professions, as did a series of editorials published in the Journal of the NCA during 1962 that strongly criticized the AMA.67–69 This information would be later used by the AMA's CoQ in their efforts to attack chiropractic.

The Iowa Plan: Origins of the AMA CoQ

The AMA's CoQ was primarily based on the work that began in Iowa in the 1950s. Officials of the IMS had committed themselves to prevent the progress of chiropractic. They asked their general legal counsel, Robert Throckmorton, to develop a plan to address “the chiropractic issue.”46 The resulting strategy was the called “The Iowa Plan,” which was aimed to contain the growth of chiropractic in the State of Iowa.70 State medical officials and leaders at the AMA were optimistic about the plan.

In 1962, Throckmorton presented a speech titled “The Menace of Chiropractic” at the North Central Medical Conference in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He described actions that chiropractors were taking to thwart medicine. He emphasized, “Chiropractors think, act, and speak in a frame of reference that is entirely foreign to the typical doctor of medicine. This is readily apparent from Chiropractic publications.”70

Throckmorton stated,

In all but a few states organized medicine has ignored Chiropractic and its effort to create a favorable ‘image' through its public relations program. This is an unwholesome situation as the public is exposed only to the Chiropractic claims of excellence and accomplishment without having the opportunity to know of the strict legal limitations imposed on Chiropractic practice, the unscientific premise on which Chiropractic is founded and the grossly inferior quality of Chiropractic training and experience.70

Throckmorton argued that chiropractors were pretending to be on the same level as medical doctors, and they used the term doctor, which confused the public. He said that medical doctors typically ignored chiropractors because they did not see themselves in “competition” with them, whereas chiropractors saw doctors of medicine as a threat. Throckmorton suggested that because of this, chiropractors “find occasion to deride or belittle scientific standards, principles and practices in order to raise their own esteem.”70 He emphasized that by attacking medicine through their promotional campaigns, chiropractic was harming scientific medicine and misleading the public.

He called chiropractic the “foremost cult in the country”70 and declared that its presence should be concerning to all members of the medical profession. Throckmorton suggested a solution to the “chiropractic menace.”70 He described the vulnerabilities of the chiropractic profession and outlined how organized medicine could use these to further weaken chiropractic.

The medical association and legal counsel perceived that chiropractors posed a threat to medicine and therefore called for a concerted effort to prevent the 2 chiropractic associations from joining into a single group and expanding their scope of practice in health care. Throckmorton recommended educating the medical profession and the public to contain the chiropractic profession and to stifle the chiropractic schools. These actions required caveats, which included that their actions needed to be:

Behind the scenes whenever possible

In attacking “cultism” in general, organized medicine need not be reticent in proclaiming the fact that chiropractic is the primary target

Never give professional recognition to chiropractors

Action should be directed against chiropractic as a cult not against chiropractors as persons: “Hate the sin but love the sinner.”70

His speech was well received by his audience. Afterward, Throckmorton was approached by leaders of the AMA, and they recruited him to join their team and lead a national effort against chiropractic. The IMS had called upon its parent organization, the AMA, and the IMS promised to “cooperate fully with the division of investigation of the AMA.”58

The AMA Adopts IMS Plans to Eradicate Chiropractic

On May 3, 1963, the AMA leaders announced that Throckmorton would be their new legal counsel. He immediately recommended that the AMA form a special group to address the chiropractic problem, thereby founding the CoQ. The committee proposed that the Iowa Plan be adopted by the AMA. The AMA hired Doyl Taylor, former executive secretary of the ISMS and founding participant of the ISMS Chiropractic Committee, to implement the plan for the AMA.

By 1963, the Iowa plan was fully covert. The IMS Chiropractic Committee chairman met with Throckmorton to discuss future plans of action, which included traveling to county medical societies to provide programs on how to contain chiropractic. The IMS continued its affirmation to work closely with the AMA.71 Through its speakers bureau, the IMS dispatched representatives to several county medical societies to educate the local physicians on “legislative and other matters of public interest pertaining to the practice of chiropractic.”72 By 1964, the IMS had relinquished all chiropractic containment activities to the AMA.

The JIMS announced a conference on quackery offered by the Iowa Interprofessional Association using its “In the Public Interest” fact sheet within the JIMS. The 1st item on the program was a speech on the AMA's campaign against medical quackery by Oliver Field, the director of the AMA's Department of Investigation. The ISMS Chiropractic Committee and current chairman of the AMA Committee on Medical Quackery delivered the presentation titled “A Look at Chiropractic.”73 It was out of these efforts that the AMA's CoQ was born.74

Collecting information From Chiropractic Colleges

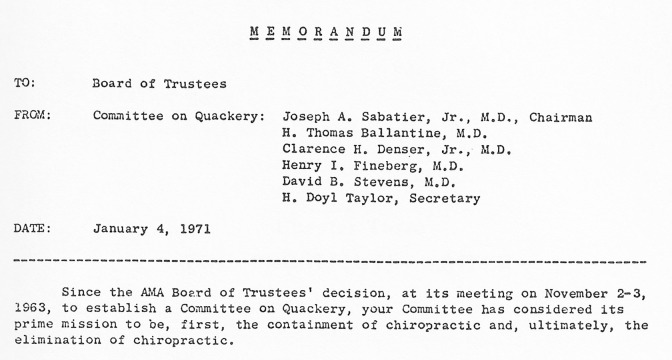

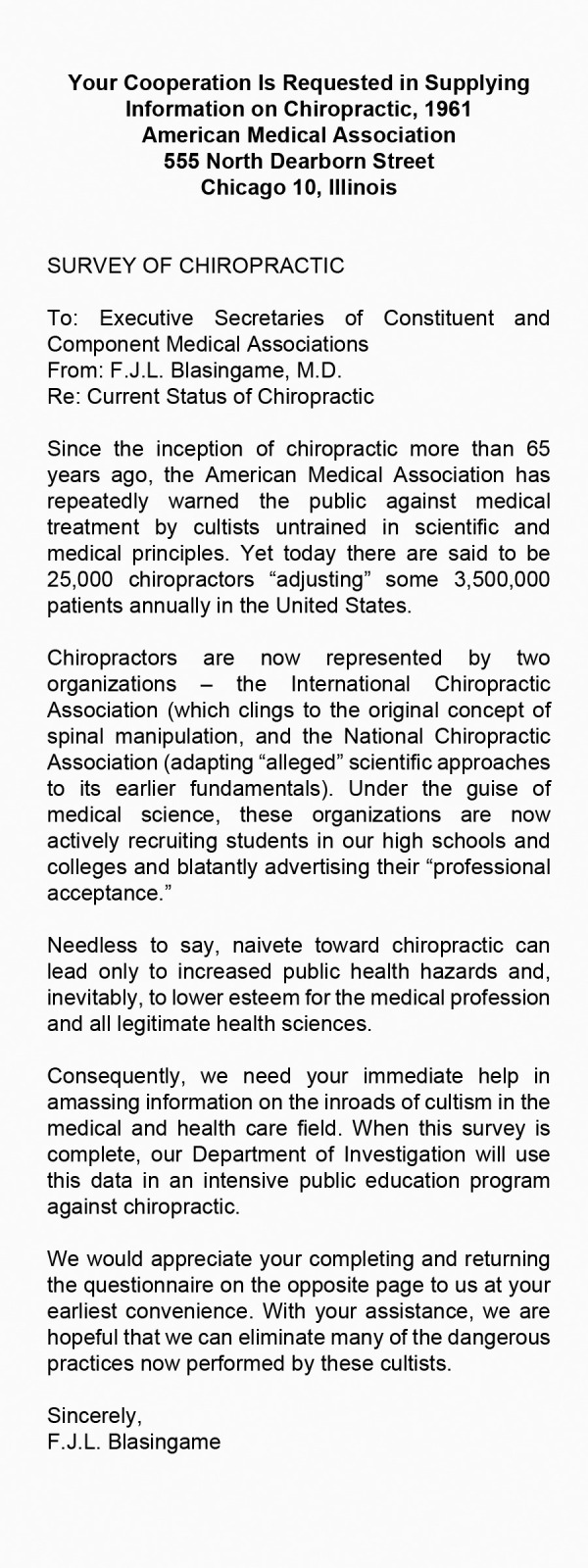

According to the minutes, the CoQ's mission was to “contain and eliminate” the chiropractic profession (Fig. 3).75 Most of the CoQ members had no experience working with chiropractors and knew nothing about chiropractic. Some of their first actions were to obtain current information from the chiropractic programs, which included obtaining copies of the schools' literature. To secretly obtain this information, the CoQ members submitted fictitious applications to see what type of students the chiropractic schools would be willing to enroll. They sent letters of inquiry to the colleges by posing as interested prospective students and gathered the response letters from the chiropractic colleges.

Figure 3.

- A memorandum from the American Medical Association's Committee on Quackery outlining that its prime mission included “the containment of chiropractic and, ultimately, the elimination of chiropractic.”

They proposed that the results of their study should be published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). However, they wanted to make sure that the clandestine plans of the CoQ were not revealed and “suggested that the report should be identified with a source other than the CoQ. The Committee agreed that the report should be from the Department of Investigation.”75 Once they published their report that disparaged chiropractic, they distributed it to physicians, medical schools, and the public. They also collected any available materials that criticized chiropractic, such as articles from county medical societies.

CoQ Plan

The CoQ members were concerned that chiropractors would eventually achieve their goal of parity with medical doctors “if organized medicine remains apathetic to this problem.”76 Over a 10-year period, the CoQ focused on addressing chiropractic in the same manner that was originally described in the Iowa Plan.

Encourage chiropractic disunity

Undertake a positive program of containment

Encourage ethical complaints against doctors of chiropractic

Oppose chiropractic inroads in health insurance

Oppose chiropractic inroads in workman's compensation

Oppose chiropractic inroads into labor unions

Oppose chiropractic inroads into hospitals

Contain chiropractic schools. ‘Any successful policy of “containment” of chiropractic, must necessarily be directed at the schools. To the extent that these financial problems continue to multiply and to the extent that the schools are unsuccessful in their recruiting programs, the chiropractic menace of the future will be reduced and possibly eliminated.'76

The CoQ Goal and Objectives were presented by Dr Joseph A. Sabatier Jr. The committee adopted the following statement:

OVERALL GOAL To contain and eventually eliminate the cult of chiropractic as a health hazard in the United States.

OBJECTIVES

Maintain a fund of updated information (clinical and political) regarding chiropractic.

Maintain contact with agencies which have no official connection with AMA and which represent national constituencies.

Maintain contact with federal departments and agencies regarding chiropractic.

Maintain contact with state medical associations.

Develop model strategies which can be used by state associations in containing chiropractic at the state and local levels.

Stimulate activity at the state and local level.

Serve as a forum for state and local medical organizations to mutually inform each other and the AMA committee regarding the current status of chiropractic.

To utilize all possible means to inform the public about the health hazard posed by the cult of chiropractic.75

During one of the early CoQ meetings, a discussion was held to determine if AMA representatives or committee members should meet with chiropractors to discuss matters. Throckmorton had experience in working with osteopaths and podiatrists and shared that meetings with representatives from those professions were helpful. He also had witnessed what could happen if no meetings were held, such as with the optometrists who were suing the AMA because there were “no lines of communication.”77

Even though AMA legal counsel was in support of meeting with chiropractors to gain more information, there were others on the committee who were opposed to this idea. According to their minutes, committee members discussed how they wanted to avoid meeting as this might give chiropractors “status and recognition,” which the CoQ wanted to avoid. It was noted that prior experiences in meeting with other groups (eg, osteopaths) resulted in frustration. Others worried that a meeting would give an appearance of “official sanction” by the AMA. Dr Sabatier said that “the medical profession has always been very careful in Louisiana not to have formalized meetings, but whenever they ask the chiropractors for information on what chiropractic is, they never received an answer because the chiropractors know that they have nothing to offer.”75 With so many committee members opposed to meeting with chiropractors, it was decided that they would not meet to gather information but instead obtain information through indirect methods.

The meeting minutes showed that even before they collected and reviewed any information about chiropractic, the committee had already concluded that chiropractic was harmful and needed to be eliminated. As would be revealed later during the Wilk v AMA trial, their actions were not based on evidence, and they had no plans to assess if what chiropractors did was in any way helpful to the public.

The committee members met several times each year to share information and update each other on their progress. Several themes repeated throughout their meetings. The committee felt that chiropractic lacked the scientific underpinnings to support what it claimed to do and did not have the research to back up these claims. By documenting these weaknesses and then distributing this information, the CoQ members hoped to convince policy makers and AMA members that they should not interact with the chiropractic profession. An example was a speech by Doyl Taylor called “Health Quackery,” which was given at a meeting in Indiana. His speech also included other concerns of the day, including unproven drugs for cancer, arthritis, and obesity. However, the last and most emphatic portion of his presentation focused on chiropractic:

Since the birth of chiropractic in 1895, the AMA has considered chiropractic an unscientific cult whose practitioners are not qualified to diagnose and treat human illness. That chiropractic is an unscientific cult is an established fact. Chiropractic is unscientific because, despite all the years of its questionable existence, it has not furnished a single shred of scientific proof for the hypothesis on which chiropractic is based – that human disease is caused by a spinal subluxation and cured by a spinal adjustment.78

AMA Propaganda

The AMA provided consistent messages to the public that it represented organized medicine and that the AMA opposed chiropractic since the early 1900s. Newspapers and AMA publications made organized medicine's distaste for chiropractic clear with the publications of various exposés and news articles.

For example, as included in the pages of JAMA in 1914 and reported in The Ottawa Daily Republic,79

An Estimate of Chiropractic by the Journal of the A.M.A.

Chiropractic is a freak offshoot from osteopathy. Its followers assert that disease is caused by pressure on the spinal nerves and can be eradicated by ‘adjusting' the vertebrae. It is the sheerest kind of quackery, practiced largely by men whose general education is as limited as their knowledge of anatomy, and who are profoundly ignorant of the fundamental science on which the treatment of disease in the human body depends. ... Chiropractic is in no sense a profession. It is a scheme by which sharpers induce men generally of little education and with a dwarfed sense of moral obligation, to learn the tricks of a disreputable trade – quackery.80

The AMA was consistent in its attacks against chiropractic. The following criticisms about chiropractic were included in JAMA in 1918.

A more dangerous type of quackery, however, is represented by the various pseudomedical cults—more dangerous because they are built on fallacies, misrepresentations and extravagant claims in regard to the cure of diseases. Most flagrant is ‘chiropractic.' Followers of this cult are sending circulars through the mails and publishing advertisements in newspapers—sometimes utilizing whole pages—claiming that by a simple manipulation of a portion of the spine they can cure all diseases from toothache and felons to apoplexy, locomotor ataxia, nephritis and epilepsy. The menace of their pretensions is shown in their claim to cure infantile paralysis—a serious disease even in the hands of the most skilled and thoroughly trained physician. The utter absurdity of their claims is indicated by the fact that they are not trained in the simplest rudiments of medical knowledge, and avowedly turn their backs on all modern scientific methods.81

The AMA had been gathering information on various health professions for decades, and they had an extensive collection of chiropractic propaganda by the 1960s. The AMA's Department of Investigation developed pamphlets titled “Chiropractic: The Unscientific Cult.” The pamphlet described how the AMA CoQ collected information for the booklet. “In its quest for objective, accurate information on chiropractic, the AMA CoQ sought out textbooks presently used in chiropractic schools, literature presently dispensed by chiropractic leaders in current chiropractic journals and reports and in the official records of the courts.”82

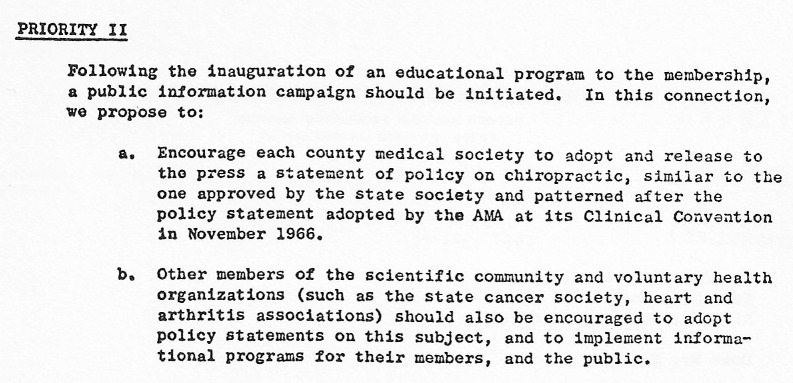

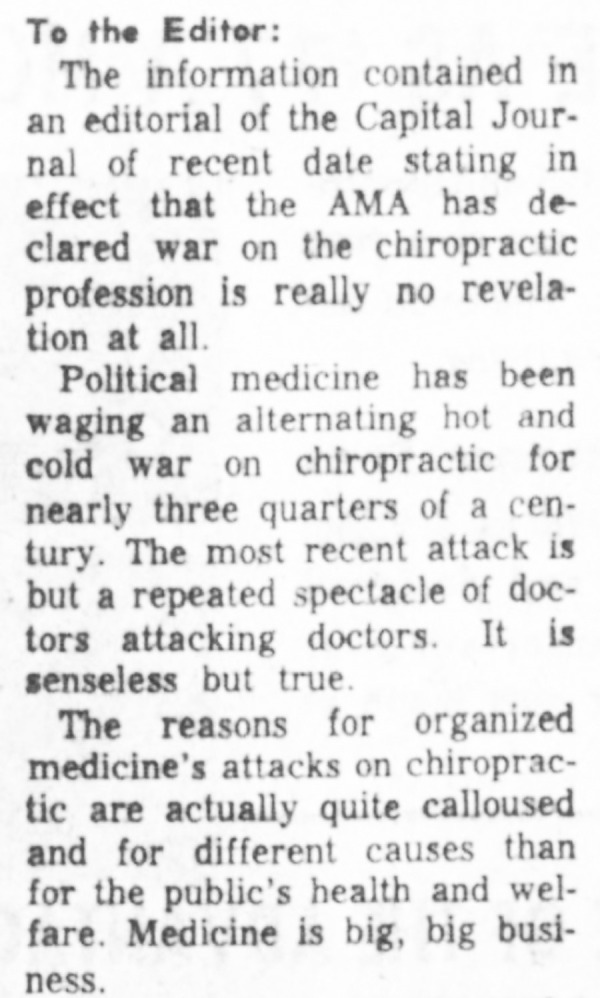

The AMA's influence was far reaching. By engaging the state and local medical associations, a coordinated propaganda was developed and distributed. By having the AMA's message distributed through other entities, it would appear as if different organizations were delivering the same viewpoint (Fig. 4).74

Figure 4.

- Priority II, a portion of the CoQ plan containing a public information campaign, outlines directives for various entities that were under American Medical Association control to distribute propaganda about chiropractic. These actions showed that the American Medical Association was planning to collude with other organizations to restrain trade, the practices performed by chiropractors.

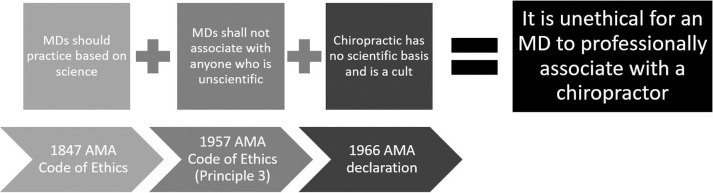

Changes in the AMA Code of Ethics and Principle 3

Although the attacks on chiropractic were not new, the AMA decided to take more aggressive action to contain and eliminate chiropractic. In 1957, the AMA changed its Principles of Medical Ethics to be more prescriptive. This included the principle that had the largest impact on the Wilk et al v AMA et al lawsuit, which was Principle 3:83

Section 3. A physician should practice a method of healing founded on a scientific basis; and he should not voluntarily associate professionally with anyone who violates this principle.

Section 4. The medical professional should safeguard the public and itself against physicians deficient in moral character or professional competence. Physicians should observe all laws, uphold the dignity and honor of the profession and accept its self-imposed disciplines. They should expose, without hesitation, illegal or unethical conduct of fellow members of the profession.84

This change would facilitate the efforts of the AMA to gain greater control over American health care and eventually influence events leading up to the lawsuit. In 1961, the AMA House of Delegates passed a resolution stating that it was unethical for a medical doctor to associate with a cultist. However, they could not apply this ethical rule to chiropractors since the AMA had not yet explicitly stated in their declarations that chiropractors were cultists.

Therefore, to prevent medical doctors from working with chiropractors, a clear statement from the AMA that chiropractors were cultists needed to be drafted. To accomplish this, they tied the necessary wording to the AMA Principles of Medical Ethics. Principle 3 stated that a medical doctor could not associate with another doctor who did not practice health care that was based on science. Thus, anyone deemed to be unscientific by the AMA would be considered an outcast. In December 1966, the AMA passed a resolution stating,

It is the position of the medical profession that chiropractic is an unscientific cult whose practitioners lack the necessary training and background to diagnose and treat human disease. Chiropractic constitutes a hazard to rational healthcare in the United States because of the substandard and unscientific education of its practitioners and their rigid adherence to an irrational, unscientific approach to disease causation.85

Due to this resolution and its combination with the additional declarations, the AMA solidified their stance that it was considered unethical for a medical doctor to receive a patient from a chiropractor or to send a patient to a chiropractor (Fig. 5). This action declared publicly that any medical doctor who interacted with a chiropractor would be breaking the code of ethics and therefore be at risk for sanctions.

Figure 5.

- Steps that the CoQ used to establish an environment that prevented medical doctors from working with chiropractors and prevented chiropractors from being allowed to work in hospitals. (Permission to reproduce figure granted by Brighthall.)

For a doctor of medicine to practice successfully in the United States, he needed to adhere to the AMA Code of Ethics. If he did not, he would risk his livelihood by losing his hospital privileges and licensure. The combination of resolutions demonstrated that the AMA furthered the distance between organized medicine and chiropractic and was evidence that the 2 professions were competing for the same patients. The AMA's policies directed medical doctors that they were not allowed to interact with chiropractors, and chiropractors were not allowed in hospitals.

The AMA had openly declared war on chiropractic. By April 1966, The Los Angeles Times published an article with the headline, “Chiropractors Will Be AMA Campaign Target.”

The American Medical Assn. is making chiropractors its primary target in a national campaign against medical quackery, the association's chief investigator said Saturday. In the past the AMA has been somewhat reserved in its pronouncements about chiropractors, but investigator Doyl Taylor assailed them as “cultists who deny the very premises of scientific medicine.” Chiropractors in general have little scientific medical education, he said, and the nation's schools for chiropractors are staffed mostly be persons who have no degrees from accredited institutions.

Taylor told a Conference on Health Education of the Public that the AMA's committee on quackery considers the chiropractic problem the biggest it faces in an education drive on medical quacks. He said the AMA will see revisions of licensing requirements in the 47 states that license the practice. They will also seek legislation requiring stiffer educational standards for chiropractors.86

The Pittsburgh Press in early October 1966 published the following AMA announcement describing the presentation made by the leadership of the AMA's CoQ that would attack chiropractic:

AMA Calls Open Season on Quacks. The American Medical Assn. today launched its third national conference on medical quackery - turning its critical eye on the pills, powders, potions, philtres and fraudulent electrical gadgets on which gullible Americans spend more than one billion dollars a year. But the AMA investigators saved their biggest guns for tomorrow, when three doctors will deliver papers on one subject on which the AMA has hitherto remained silent - the chiropractors. Dr Joseph A. Sabatier Jr., of the AMA's committee on quackery, will wind up the session with a slide-film documentary on chiropractic.87

The few published communications from the chiropractic profession were chiropractic reactive responses to attacks by the AMA. The AMA's funding, staff, and legal team had extensive resources and continued to show chiropractic to the public in the worst possible light:

Chiropractic Called Cult by A.M.A. Chief The president of the American Medical Assn. told a meeting on health quackery that chiropractic is ‘an unscientific cult' which, ‘despite all its years of existence, has not furnished a single shred to scientific proof for the hypothesis upon which' it is based.88

AMA Influence on Mainstream Media

The CoQ arranged to have various other sources use and distribute their AMA propaganda so that the AMA would not be implicated in the attacks against chiropractic. Exemplary was this quote from the trial transcript: “the AMA's hand must not show in these debates. We must utilize sources other than the AMA to obviate the quality time or fairness that the press associations are showing to the chiropractors in allowing them to respond.”89

Beyond its own publications, the AMA used clandestine measures to influence and manipulate the popular press. An example was the AMA's connection with Ann Landers, a newspaper columnist who gave advice to the lovelorn and curious in her syndicated column and was trusted by the American public. She had a tremendous amount of influence on public perceptions.

Ann Landers was closely involved with the AMA as an invited member of the AMA's Advisory Committee on Health Care of the American People. The Advisory Committee was created by the AMA to “further open the door to communication between physicians and leaders in other fields. The AMA wants to obtain through this committee the advice and suggestions of respected representatives of business, education, religion, law, government, women's organizations, labor, minority groups, publishing and other social and professional elements.”90 Ann Landers was publicly announced as a member in 1968,91 and the AMA used its relationship with her to influence responses in her column. For example, the following letter was published in 1971.

Dear Ann Landers:

A few days ago a fellow my husband works with got sick on the job. He refused to go to the company doctor and said he had his own specialist - a chiropractor.

Today the man was back at the mill feeling fine. He told my husband if more people went to chiropractors instead of to society doctors they'd be better off. He claims all ailments are tied up with the nerves of the spine and the chiropractor knows which nerves to press to get the person well.

He says it's much cheaper than fancy medical care, because the doctors are in cahoots with the drug manufacturers and all they are interested in is money.

We have been reading your column for years and we believe in what you say. What are your views on chiropractors?

Pittsburgh People

Dear People:

Chiropractors are wonderful - if you have a tired back, and nothing else. But if you are sick I hope you will go to a physician who has been licensed by his state's Board of Medical Examiners.

Many illnesses are self-limiting. This means they disappear without treatment. A person who has been massaged by a chiropractor and gets well often credits the chiropractor with having cured him. The truth is, he'd probably have been cured if he had fanned himself with goofus feathers. This is why most chiropractors do such a thriving business. Massaging the spine will not cure a brain tumor, cancer, diabetes or gallstones. Nor will it cure a skin disease or a throat infection. The following testimony was given to a Congressional committee considering the question, ‘Should chiropractors be included in Medicare?'

It is the universal opinion of health experts that chiropractors lack the proper training and background to diagnoses and treat human disease. The education of chiropractors is substandard and unscientific and the theory on which treatment is based is medically unsound.92

The AMA's influence can be seen when comparing the wording in Ann Lander's reply to the AMA's statement from the 1966 House of Delegates meeting:

It is the position of the medical profession that chiropractic is an unscientific cult whose practitioners lack the necessary training and background to diagnose and treat human disease. Chiropractic constitutes a hazard to rational health care in the United States because of the substandard and unscientific education of its practitioners and their rigid adherence to an irrational, unscientific approach to disease causation.82

Millions of Americans read her column. With the increased propaganda being published by the AMA, and similar messages in advice columns that were supposedly from unrelated sources, the public was directly or indirectly receiving messages from the AMA that there was something wrong with chiropractic. Another column included the following response from Ann Landers:

Dear Annette: Aches and pains sometimes respond to the chiropractor's heat lamp or manual massages but I do not recommend chiropractors as diagnosticians because they lack the training to diagnose properly.

Every year millions of dollars are spent on chiropractors before the patient gets smart and switches to a physician or an osteopath. Unfortunately, too many people keep going to chiropractors until their illness becomes so advanced that an M.D. or a D.O. can't help them.

The basic concept of chiropractic is that most illnesses are caused by spinal misalignments (i.e., chiropractic vertebral subluxations) and can be cured by spinal adjustments. This theory has been thoroughly discredited, yet millions of people continue to believe in it and they shell out a great deal of money on this poppycock.93

The American Chiropractic Association (ACA) president criticized Landers's column in the following response.

Since this is not the first time Miss Landers has used her column to make disparaging remarks about chiropractic, we have good reason to believe that political medicine is using Miss Landers to plant slander-oriented information against the profession. The vigor and frequency with which the AMA is using media has increased since chiropractic's inclusion in Medicare last year. Obviously, the AMA views broader Medicare benefits as a threat to its monopolistic strangle hold on the America Health scene.94

By using other people and organizations that seemed unconnected with the AMA, it appeared as if there were many different voices with the same view as the AMA. However, as the CoQ had planned, these articles were prepared, ghostwritten, or heavily edited by AMA staff. These materials entered mainstream media through newspapers or magazine articles, and the public was unaware of the extent of control that the AMA had over the contents.

AMA Influence on the US Senate

The AMA also influenced the US Senate. In a statement to the US Senate from the AMA, Robert Throckmorton stated,

“One of our primary purposes, announced at the time of the founding of the AMA in 1847, was the combating of quackery in all its forms. Since that time, the AMA has had an unceasing interest in this problem and has continuously devoted its efforts to the eradication of this menace.”95

And later he stated,

“the board of trustees of the AMA, in November 1963, authorized the appointment of an AMA Committee on Quackery. This will be the first time that the AMA has had a specific committee to deal with this problem. It is composed of five eminent physicians from around the country who are knowledgeable and authoritative in this field. Such a committee will provide guidance to the work of the AMA staff and add prestige and impetus to our present efforts. Most of the work that I have mentioned is directed against the quack outside of medicine.”95

Department of Health, Education and Welfare

From 1965 to 1970, chiropractors lobbied to be included in Medicare coverage. However, the leadership in the AMA countered these attempts.

The efforts of the chiropractors to broaden the scope of their activities continue and their latest strategy is to try to obtain approval for the treatment of patients under the Medicare program. This and all future attempts must be vigorously opposed by the medical profession as was emphasized by Dr Sabatier, chairman of the AMA Committee on Quackery, in his letter to the editor in the August BULLETIN.96

Chiropractors brought their plea to Congress, which then ordered a study be performed by the Secretary of the US Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW). The purpose of the study was to report to Congress whether coverage for chiropractic services under Medicare was needed.

The AMA CoQ worked from behind the scenes to influence the HEW study to condemn chiropractic by placing selected members on the study panel who were favorable to the AMA plan and made sure that no panelists were chiropractors. The CoQ developed a list of potential committee members and systematically planned how they would influence each panelist. The CoQ leaders put pressure on the committee members so that the HEW report would have the outcome that the AMA wanted. Those who were AMA members were easily reached through friends and associates. Dr John McMillan Mennell, a medical orthopedist, was 1 of the 8 on the committee. Mennell recalled the interactions:

I was disturbed in the past four weeks to receive two telephone calls indirectly from, but quite clearly inspired by, the American Medical Association implicitly suggesting what the tenor of my paper should be. I can only assure the consultant group that my conclusions are arrived at through my independent research, thinking and experience unaffected by extraneous pressure.97

Walter Wardwell, PhD, a sociologist who had been studying the health professions, including chiropractic, for many years, was invited to be a part of the panel. Dr Wardwell reported that he had received communications that attempted to influence the direction of the HEW study. The correspondence showed that the AMA had already determined what the outcome of the committee's deliberations should be, months before the committee first met.98 When the day came for the committee to decide by vote if they would or would not recommend chiropractic, the vote was tied 4 to 4. Then, without any explanation, 2 votes changed, and the final recommendation was to deny the inclusion of chiropractic. They submitted their report in November 1968, and chiropractic was denied inclusion in Medicare.98

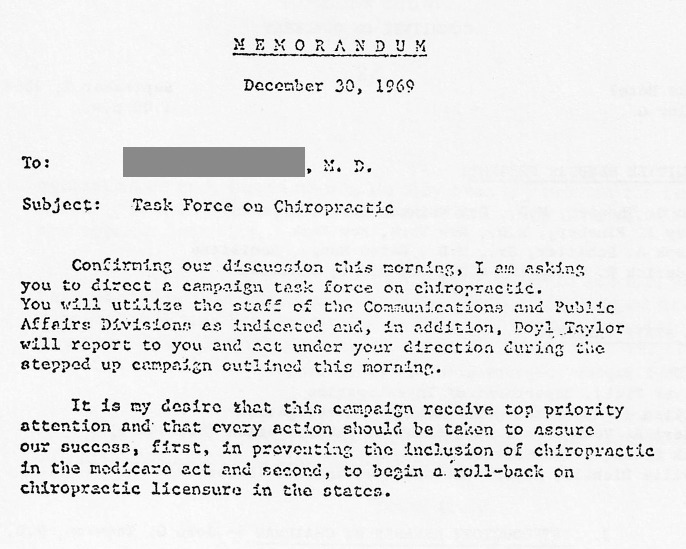

After the HEW report was released, the ACA and ICA responded with an informational document that exposed the AMA involvement. The views in the chiropractic white paper rebutted each of the arguments in the HEW report. Although there were concerns about AMA tampering, these were never thoroughly investigated or rectified. The AMA used the information from what they called an “unbiased” HEW report as evidence for their continued actions against chiropractic.98 These actions were part of the CoQ plan (Fig. 6).74

Figure 6.

- A memo with instructions to use American Medical Association resources and “that every action should be taken to assure our success” to prevent chiropractic inclusion in the Medicare act and to roll back chiropractic licensure. This communication showed the forceful tone of the American Medical Association's efforts to eliminate the chiropractic profession.

AMA Attempts to Undermine Chiropractic Education

The AMA forbade medical doctors from teaching at chiropractic colleges or lecturing to chiropractic groups, and chiropractors were not allowed to present lectures at medical conferences or to publish scientific papers in medical journals. The CoQ's prevention of collaboration of academics of the 2 professions curtailed the intellectual growth of the chiropractic profession.74

The AMA fought against chiropractic schools receiving US Office of Education recognition for accreditation and federal funding for student loans. If the AMA kept the quality of education as low as possible, by not allowing medical faculty members to teach core subjects such as the basic sciences and diagnosis, then accreditation would be much more difficult for the chiropractic programs to attain. The CoQ reasoned that if chiropractic schools could be shut down, then there would be no production of chiropractors, which would then eliminate the “chiropractic problem” (Fig. 7).74

Figure 7.

- The American Medical Association efforts to harm chiropractic were systemically embedded in the US educational system. The AMA extended great effort to influence vocational guidance counselors and to send propaganda to discourage high school and colleges students from considering chiropractic careers. Of note, this American Medical Association Committee on Quackery document was written during the time that chiropractors were fighting for chiropractic program accreditation. The Council on Chiropractic Education began in 1974 and is recognized by the United States Department of Education to accredit programs offering the doctor of chiropractic degree.

AMA Sponsored a Book Attacking Chiropractic

In 1969, the AMA clandestinely sponsored Mr Ralph Lee Smith to write a exposé on chiropractic called At Your Own Risk: The Case Against Chiropractic.99 The AMA used this book to further promote its agenda. Sabatier published a review of the book in JAMA:

The rapidly growing accumulation of compelling evidence that chiropractic is a public health hazard has been documented again in a newly published book, entitled At Your Own Risk: The Case Against Chiropractic.

After 11 chapters of documentation, Smith proposes two steps which must be taken by the legislatures of the 48 states that license chiropractors. The immediate first step is to prohibit further use of X-ray by chiropractors. Second, each state must create an orderly program for withdrawing chiropractic licenses.

Only by public exposure can any unscientific cult such as chiropractic be placed in the proper perspective and thereby fulfill the obligation shared by all who bear the burden of protecting the public's health. This book provides documented evidence upon which the scientific community, the general public—and most important of all—legislative bodies can reach a proper conclusion.100

Initially, the book was presented as if it were an unbiased work by an independent reporter. However, it was confirmed later that the AMA provided the material, office space, and funding for Smith's work.89 Smith used the archives in AMA headquarters to develop his drafts. Mr Youngerman (an AMA attorney) and Doyl Taylor influenced the book by working with Smith on writing drafts and the revisions.89

AMA Influence on Other Associations and Societies

Around 1967, the CoQ accelerated its implementation plan to contain and eliminate chiropractic. They approached medical specialty, state, and other societies, encouraging them to use the AMA's Principles of Medical Ethics in their local bylaws. Influencing these bylaws reinforced the behaviors at the local, state, and national level that it would be unethical for any medical doctor to interact with a chiropractor. The AMA staff drafted anti-chiropractic statements for state medical societies, which were adopted.75

AMA Influence on Hospital Access

The AMA had a substantial influence on the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals. The Commission was the lead organization that accredited hospitals for Medicare and Medicaid.101 The AMA and its sister organizations controlled the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals. The Joint Commission was directed by a Board of Commissioners, including 7 commissioners appointed by the AMA, 7 by the American Hospital Association, 3 by the American College of Physicians, and 3 by the American College of Surgeons.101

With many of the Commission board members being representatives of the AMA, the Commission was pressed to include the Principles of Medical Ethics as part of its standards. The adoption of the principles by the Commission resulted in a policy that any hospital or medical doctor associated with a Joint Commission–accredited hospital had to abide by the AMA Principles of Medical Ethics. Thus, if a person or the hospital violated the principles, the hospital accreditation would have been in jeopardy of not receiving federal funding. The AMA created the environment so that if a medical doctor worked with a chiropractor, he would risk his practice and his hospital's federal funding if he continued to do so. This put immense pressure on medical doctors and hospitals to follow the AMA's directives to avoid working with chiropractors.

In 1965, when Congress passed the Medicare Act, the Joint Commission became the organization that determined if hospitals met quality and eligibility standards for Medicare and Medicaid.101 Thus, if a hospital desired to gain accreditation to be eligible for federal funds for the care of patients, it had to undergo either a certification inspection by a state agency or accreditation by the Joint Commission.101 If a hospital had gained Joint Commission accreditation but then lost it through a deficient Joint Commission survey, the hospital would lose its federal funding.

The Joint Commission was using the 1957 version of the AMA Principles of Medical Ethics. The Joint Commission's accrediting manual warned that the physicians, staff, and governing bodies of hospitals were to adhere to the AMA Principles of Medical Ethics or the hospital would face nonaccreditation.98 The manual stated, “A hospital for accreditation, in effect, will require all medical physicians to comply with ‘The Principles of Medical Ethics.'”89 Sections 3 and 4 of the principles warned physicians against associating with nonscientific practitioners, which chiropractors were considered by the AMA, and the policing of this principle.98 Thus, if a person or the hospital violated principle sections 3 or 4, the hospital accreditation was in jeopardy.98

In its effort to contain and eliminate chiropractic, the JAMA published, “A hospital, whether public or private, has not only a right, but also a duty to refuse to grant staff privileges to a chiropractor. This duty is based on the duty of the hospital, acting on the recommendation of its medical staff, to protect its patients from unqualified and incompetent practitioners. Cultist practitioners, such as chiropractors, are medically unqualified and incompetent practitioners.”102 Thus through this process, the AMA pressured hospital staff and administrators to prevent the inclusion of chiropractic care in hospitals. These above actions by the AMA would later be recognized during the Wilk v American Medical Association lawsuit as restraint of chiropractors' business practices.

DISCUSSION

By the 1950s, American medicine was in its golden age and was dominant in the US health care system.103,104 Popular press and television shows reinforced the messaging to the public, where it was perceived by many that medical doctors were the center of the health care system, and they could do no wrong.

The AMA was a powerful organization that had a far-reaching network and infrastructure throughout the United States.105 Influence over medical doctors' licensure, hospital privileges, referrals, and consultations resulted in AMA control over members' actions and with whom they could affiliate. If the AMA deemed a certain medical physician or other professional unworthy, medical doctors would comply with that determination for fear of being ostracized. Hyde described the power and politics of the AMA in the 1950s and stated,

It is the practitioner who is expelled or denied membership who finds the punitive tactics of organized medicine employed to their fullest against him. In these cases non-membership amounts to a partial revocation of licensure to practice medicine. It is only the established physician with guaranteed tenure on hospital staffs and specialty boards, or one who has the security of a faculty or governmental position who can afford to challenge the ethical standards of the AMA. Few doctors enjoy such a status, and defiance of AMA authority means professional suicide for the majority.105

The increasing confidence within the AMA leadership may have emboldened the AMA to further secure their grip on the American health care system. The AMA leadership was aware that some chiropractors were attempting to expand their scopes of practice. The England, et al v the Louisiana State Board of Medical Examiners trial was filed by 120 chiropractors, led by Jerry England, DC, in an attempt to establish the rights of chiropractors to practice in Louisiana.106 The CoQ members discussed the legal case during their November 1964 meeting. They were concerned that “if the chiropractors are successful in this suit, the result will be to allow them to do anything an M.D. can do.”75

The AMA also observed that some MDs were collaborating with doctors of chiropractic. This meant that some AMA members were becoming complacent and ignoring the AMA code of ethics, which stated that medical doctors should not professionally recognize or work with health professions that the AMA deemed to be irregular. The AMA used this information as a lever to take more aggressive action against the chiropractic profession. These efforts also seemed to be an attempt to rally the AMA members by designating chiropractors as their enemy. Further efforts were made by hiring a legal team that would craft a plan that aimed to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession.

The AMA's CoQ set about its work to systematically eliminate the chiropractic profession without any foundation of scientific evidence for their actions. Nowhere in the CoQ minutes was there a description of them trying to gather information to find out the facts about chiropractic or to assist the chiropractic profession in improving its education or science. Their choice to disregard investigation meant that they overlooked that some forms of chiropractic treatment were effective. These actions would eventually contribute to the final trial judgment decades later showing that “the AMA's concern for scientific method in patient care could have been adequately satisfied in a manner less restrictive of competition and that a nationwide conspiracy to eliminate a licensed profession was not justified by the concern for scientific method.”107

Consistent with decades prior, organized medicine continued to attack and label chiropractic a “cult” throughout its communications. The AMA had been watching and fighting against chiropractic since it first became aware of the profession in the early 1900s. Thus, the AMA fight against chiropractic in the 1960s was not new. The AMA adopting the Iowa Plan and implementing it through the AMA CoQ was simply a more concentrated effort.

Despite the efforts of the chiropractic professional organizations trying to shine a positive light on chiropractic through advertising and the popular press, the AMA juggernaut had superior resources. AMA campaigns, either overt or clandestine, influenced the public's view. Reading the newspaper headlines made it clear that the AMA was directly attacking chiropractic. However, it was not clear how subversive the actions were. Ghost writing for popular press and heavily influencing reports to Congress were actions that would not be visualized until this evidence was later revealed during the Wilk v AMA trials.

Although the AMA was working secretly to implement its plan, claims that chiropractors were unaware of the AMA attacks against the chiropractic profession are not founded. Much of the actions by the AMA were made publicly available either in medical publications, public statements, or newspapers and were well known throughout the chiropractic profession (Fig. 8).108 The fact was that medicine had never stopped trying to eliminate other health professions and that these efforts were simply intensifying as chiropractors grew in numbers and the profession expanded.

Figure 8.

- A 1965 letter to a newspaper editor from Dr G. D. Parrott, editor of the Journal of the Oregon Association of Chiropractic Physicians, pointing out that the American Medical Association war against chiropractic had been going on since the beginning of chiropractic.

By reading the newspaper headlines, it was clear that political medicine had a war going with chiropractic (Fig. 9).109 Unfortunately, even though the chiropractic national association leaders were aware, they continued to fight among themselves and did not join together to fight back against the AMA. They had only a fraction of the resources for public relations compared with the AMA. Thus, aside from chiropractic advertising propaganda, there was very little available to show what chiropractic was capable of during this time.

Figure 9.

- This headline in the Chicago Tribune declares war. There was no mystery that the American Medical Association was attacking the chiropractic profession. The American Medical Association's headquarters is in Chicago, Illinois.

The AMA's CoQ created a hall of mirrors by prompting others to replicate their message. Although each point of criticism of chiropractic seemed to be generated from different sources, in reality, these messages were being generated under the AMA's direct or indirect influence. The selection of popular figures such as the advice columnist Ann Landers brought the subtle yet damaging opinions about chiropractic into the homes of Americans.

Not all medical doctors were opposed to chiropractors. Most medical doctors in the United States were likely unaware of the CoQ's efforts, and some were happy to work with their chiropractic colleagues. However, the AMA controlled the means by which medical doctors could practice. This control included licensure, hospital accreditation, medical associations, and sources for payment. Therefore, any medical doctors who may have been willing to collaborate outside of the AMA rules were eventually forced to bend to the will of the AMA.

Because the AMA strongly influenced medical education, it was able to indoctrinate medical students to perceive that all chiropractors were the enemy of medical practice and harmful to the public. Thus, the AMA created generations of medical doctors who, even when given evidence that chiropractic could be helpful to patients, closed their minds to the possibilities of collaboration.

For decades, the AMA continued to build a mass of anti-chiropractic propaganda that would sway the medical profession and the public to believe that chiropractors were ineffective or harmful, even though there was no scientific evidence to support these statements. This created generations of people who were indoctrinated with anti-chiropractic messages. This environment influenced decisions made by the public, legislators, health care providers, and policy makers, all of which resulted in a negative impact on the chiropractic profession's ability to practice and do business. Although the AMA efforts against chiropractic persisted, patients continued to seek care from their local neighborhood chiropractors. As chiropractors felt the increasing oppression and criticism, a few felt compelled to take action.

Limitations

This historical narrative reviews events from the context of the chiropractic profession, and the viewpoints are limited by the authors' framework and worldview. Other interpretations of historic events may be perceived differently by other authors. The context of this article must be considered in light of the authors' biases as licensed chiropractic practitioners, educators, and scientific researchers.

The primary sources of information were written testimony, oral interviews, public records, legal documents, minutes of meetings, newspapers, letters, and other artifacts. These formed the basis for our narrative and timeline. We acknowledge that recall bias is an issue when referencing sources, such as letters, in which people recount past events. Secondary sources, such as textbooks, trade magazines, and peer-reviewed journal articles, were used to verify and support the narrative. We collected thousands of documents and reconstructed the events relating to the Wilk v AMA lawsuit. Since no electronic databases exist that index many of the publications needed for this research, we conducted page-by-page hand searches of decades of publications. While it is possible that we missed some important details, great care was taken to review every page systematically for information. It is possible that we missed some sources of information and that some details of the trials and surrounding events were lost in time. The above potential limitations may have affected our interpretation of the history of these events.

Some of our sources were interviews, manuscripts, or letters in which the author recalled past events. Recall bias is an issue when referencing interview sources. Surviving documents from the first 80 years of the chiropractic profession, the years leading up to the Wilk v AMA lawsuit, are scarce. Chiropractic literature existing before the 1990s is difficult to find, since most of it was not indexed. Many libraries have divested their holdings of older material, making the acquisition of early chiropractic documents challenging. While we were able to obtain some sources from libraries, we also relied heavily on material from our own collection and materials from colleagues. Thus, there may be relevant papers or artifacts that were inadvertently missed. Our interpretation of the events related to the trials is limited to the materials available. The information regarding this history is immense, and because of space limitations, not all parts of the story could be included in this series.

CONCLUSION

Throughout the 20th century, the AMA developed its power over hospitals, insurance companies, and multiple forms of health care. Their strong lobbying force and media communications facilitated their ability to control the public's and government's view of chiropractic. By the 1960s, organized medicine heightened its efforts to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession. The intensified campaign to eliminate chiropractic began in Iowa and was later adopted by the AMA as a national campaign. Although the meetings of the AMA committees responsible for organizing the campaign were not public, the war against chiropractic was distributed widely in lay publications, medical sources, and even chiropractic journals. Details about events would eventually be more fully revealed as evidence during the Wilk v AMA trials.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the following people for their detailed reviews and feedback during development of this project: Ms Mariah Branson, Dr Alana Callender, Dr Cindy Chapman, Dr Gerry Clum, Dr Scott Haldeman, Mr Bryan Harding, Mr Patrick McNerney, Dr Louis Sportelli, Mr Glenn Ritchie, Dr Eric Russell, Dr Randy Tripp, Mr Mike Whitmer, Dr James Winterstein, Dr Wayne Wolfson, and Dr Kenneth Young.

FUNDING AND CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

This project was funded and the copyright owned by NCMIC. The views expressed in this article are only those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of NCMIC, National University of Health Sciences, or the Association of Chiropractic Colleges. BNG is the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Chiropractic Education, and CDJ is on the NCMIC board and the editorial board of the Journal of Chiropractic Education. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 3: chiropractic growth. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):45–54. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haldeman S, Chapman-Smith D, Petersen DM. Guidelines for Chiropractic Quality Assurance and Practice Parameters Proceedings of the Mercy Center Consensus Conference. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishing; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson C. What is the Association of Chiropractic Colleges Educational Conference and Research Agenda Conference? J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30(4):249–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson C, Green B. The Association of Chiropractic Colleges Educational Conference and Research Agenda Conference: 17 years of scholarship and collaboration. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33(3):165–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mootz RD, Hansen DT, Breen A, Killinger LZ, Nelson C. Health services research related to chiropractic: review and recommendations for research prioritization by the chiropractic profession. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(9):707–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haas M, Bronfort G, Evans RL. Chiropractic clinical research: progress and recommendations. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(9):695–706. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mrozek JP, Till H, Taylor-Vaisey AL, Wickes D. Research in chiropractic education: an update. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(9):762–773. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cramer G, Budgell B, Henderson C, Khalsa P, Pickar J. Basic science research related to chiropractic spinal adjusting: the state of the art and recommendations revisited. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(9):726–761. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bigos SJ, Bowyer OR, Braen GR, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines No 14 AHCPR Publication No 950642. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1994. Acute low back problems in adults. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haldeman S, Carroll L, Cassidy JD, Schubert J, Nygren A. The Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders: executive summary. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(2 suppl):S7–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson C, Baird R, Dougherty PE, et al. Chiropractic and public health: current state and future vision. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(6):397–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson C, Green BN. Public health, wellness, prevention, and health promotion: considering the role of chiropractic and determinants of health. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(6):405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]