Abstract

Objective

This paper is the eighth in a series that explores the historical events surrounding the Wilk v American Medical Association (AMA) lawsuit in which the plaintiffs argued that the AMA, the American Hospital Association, and other medical specialty societies violated antitrust law by restraining chiropractors' business practices. The purpose of this paper is to discuss the possible impact that the final decision in favor of the plaintiffs may have had on the chiropractic profession.

Methods

This historical research study used a phenomenological approach to qualitative inquiry into the conflict between regular medicine and chiropractic and the events before, during, and after a legal dispute at the time of modernization of the chiropractic profession. Our methods included obtaining primary and secondary data sources. The final narrative recount was developed into 8 papers following a successive timeline. This paper is the eighth of the series that discusses how the trial decision may have influenced the chiropractic that we know today in the United States.

Results

Chiropractic practice, education, and research have changed since before the lawsuit was filed. There are several areas in which we propose that the trial decision may have had an impact on the chiropractic profession.

Conclusion

The lawsuit removed the barriers that were implemented by organized medicine against the chiropractic profession. The quality of chiropractic practice, education, and research continues to improve and the profession continues to meet its most fundamental mission: to improve the lives of patients. Chiropractors practicing in the United States today are allowed to collaborate freely with other health professionals. Today, patients have the option to access chiropractic care because of the dedicated efforts of many people to reduce the previous barriers. It is up to the present-day members of the medical and chiropractic professions to look back and to remember what happened. By recalling the events surrounding the lawsuit, we may have a better understanding about our professions today. This information may help to facilitate interactions between medicine and chiropractic and to develop more respectful partnerships focused on creating a better future for the health of the public. The future of the chiropractic profession rests in the heads, hearts, and hands of its current members to do what is right.

Keywords: Health Occupations; Chiropractic; Medicine; Humanities; History, 20th Century; Antitrust Laws

INTRODUCTION

Much has transpired since the initial filing of the Wilk v AMA lawsuit in 1976, Judge Susan Getzendanner's decision in 1987, and final denial of the last appeal in 1990.1 It is impossible to know with any certainty what effects this lawsuit may have had on the chiropractic profession, the medical profession, or the public. Some may claim that the lawsuit was essential to the survival of the chiropractic profession, whereas others may claim that it was not of much consequence since most of the improvements in chiropractic had already been underway and the outcomes may have happened notwithstanding the trial decisions.

Regardless of the perceived or real associations, the events surrounding this lawsuit are important for chiropractors, chiropractic students, other health professionals, and the public to understand. These events facilitated the removal of barriers that were once imposed by the American Medical Association (AMA) and other associated organizations. Events surrounding the lawsuit resulted in chiropractors being able to further develop the chiropractic profession's foundation on scientific grounds in the best interest of the public.2 These activities included, but were not limited to, events such as the Mercy Center Consensus Conference, which produced guidelines for chiropractic quality assurance, and the Research Agenda Conferences, which brought together basic science, clinical, and educational researchers throughout the profession. Through cooperation with other professional groups, the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research guidelines have been established and interprofessional collaboration has led to the Neck Pain Task Force and the Global Spine Care Initiative.3–21

A reduction in the number of obstacles to access chiropractic care may also have occurred due to the judge's decision. The injunction made clear what happened and that AMA members were allowed to collaborate with chiropractors. This widened the doorway to interprofessional relationships and referrals. The language from the injunction also pertained to hospitals and medical clinics that may have opened new opportunities for chiropractors on interprofessional care teams in integrated care settings.22–35

Before the final decision on the lawsuit, there had been various internal and external forces that had shaped the chiropractic profession for 95 years. It should not be expected that 1 decision would be able to erase decades of persecution and discrimination. However, some outcomes could possibly be associated with the occurrence of Judge Getzendanner's decision.

Collaborative relationships that are currently developing between medicine and chiropractic may be happening because of, or at least were influenced by, the outcome of the lawsuit. We propose that these events likely would not have occurred without the successful conclusion of the Wilk v AMA lawsuit.

Understanding these historical struggles may help us better comprehend chiropractic in its current evolution and the lingering effects of the AMA boycott against chiropractic. Remnants of previous events may continue in today's culture and could affect what the chiropractic profession needs to address at present and in the future.

Chiropractic practice, education, and research were topics central to the arguments exposed during the trials. The purpose of this paper is to describe improvements in these areas and discuss how the judgment in favor of the chiropractic profession may have been associated with or influenced these changes. This paper discusses possible impact of the judgment in favor of the chiropractic profession and considers hypotheses about the results on the current state of the chiropractic profession.

METHODS

This historical study used a phenomenological approach to qualitative inquiry into the conflict between regular (orthodox) medicine and chiropractic and the events before, during, and after a legal dispute at the time of modernization of the chiropractic profession. The metatheoretical assumption that guided our research was a neohumanistic paradigm. As described by Hirschheim and Klein, “The neohumanist paradigm seeks radical change, emancipation, and potentiality, and stresses the role that different social and organizational forces play in understanding change. It focuses on all forms of barriers to emancipation-in particular, ideology (distorted communication), power, and psychological compulsions and social constraints-and seeks ways to overcome them.”36 We used a pragmatic and postmodernist approach to guide our research practices, such that objective reality may be grounded in historical context and personal experiences and interpretation may evolve with changing perspectives.37

We followed techniques described by Lune and Berg.38 These steps included identifying the topic area, conducting a background literature review, and refining the research idea. After this we identified data sources and evaluated the source materials for accuracy. Our methods included obtaining primary data sources: written testimony, oral interviews, public records, legal documents, minutes of meetings, newspapers, letters, and other artifacts. Information was obtained from publicly available collections on the internet, university archives, and privately owned collections. Secondary sources included scholarly materials from textbooks and journal articles. The materials were reviewed and then we developed a narrative recount of our findings.

The manuscript was reviewed for accuracy, completeness, and content validity by a diverse panel of experts, which included reviewers from various perspectives within the chiropractic profession ranging from broad-scope (mixer) to narrow-scope (straight) viewpoints, chiropractic historians, faculty and administrators from chiropractic degree programs, corporate leaders, participants who delivered testimony in the trials, and laypeople who are chiropractic patients. The manuscript was revised based on the reviewers' feedback and returned for additional rounds of review. The final narrative recount was developed into 8 papers that follow a chronological storyline.39–45 This paper is the eighth of the series that considers events relating to the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession and explores the current state of the chiropractic profession.

RESULTS

Practice

Decades of boycotting that prevented the collaboration of medical doctors with chiropractors established an expectation that it was not acceptable for medical physicians to work with chiropractors. Without any further clarification from the AMA, the social norm of avoiding chiropractors was part of the medical ethos.

Judge Getzendanner's injunction provided clear language that it was acceptable for hospitals to work with chiropractors, to allow chiropractors on staff, and for medical doctors to work with chiropractors. This language helped eliminate 1 of many barriers to including chiropractic care in the Military Health System and Veterans Health Administration, a benefit that had been requested by military service members and veterans for decades.46,47 Hospitals that previously would have risked their accreditation under prior AMA rules could now provide the chiropractic care that their patients had been requesting.

Over time, chiropractic services have become available in a wide array of hospitals and interprofessional clinics throughout the United States. In 1984, there were no chiropractors with hospital privileges in the United States.48 By 1987, 15 hospitals in the United States allowed hospital privileges for chiropractors.49 Within a few years, the number of hospital-based chiropractors grew. As stated by chiropractor-attorney Karl Kranz, “The Wilk v AMA antitrust suit opened hospital doors for chiropractors.”48

When discussing how medical doctors interacted with chiropractors and what impact the trial may have on clinical practice, Judge Getzendanner shared with us:

And I'm sure there were doctors at the time of the trial who were willing to deal with chiropractors. But there was, I think, a genuine fear about the ethical implications of dealing with chiropractors, caused by the conspiracy. And I was certainly not aware of any general practice of chiropractors working with doctors, during the time of the trial. And then I began to see doctors associating with chiropractors. These various sports doctors would offer chiropractic in their offices. So, they did clearly associate with chiropractors after my decision. So, my decision was very stark for a chiropractor. It was a big thing. It was a big deal. They won!50

In 1980 before the first trial concluded, the AMA revised its ethical principles, which removed the statement prohibiting AMA members from interacting with “unscientific” practitioners but allowed members to make their own judgment. The change in principles removed the threat of revocation of membership to AMA members, which would have likely resulted in loss of hospital privileges. Secondly, the American Hospital Association settled out of court with the plaintiffs in June 1987. The settlement presented the Association's position on hospitals working with chiropractors, which was that it disavowed any effort to contain, eliminate, or undermine the chiropractic profession and that the Association had no objection to hospitals working with chiropractors.51 Finally, the September 1987 injunction issued by Judge Getzendanner against the AMA had clear language that it was acceptable for hospitals to work with chiropractors and have chiropractors on staff and for medical doctors to work with chiropractors.52 These 3 events were key facilitators that advanced the interprofessional collaboration between chiropractors and medical doctors that would allow them to work together to provide services to patients.

Education

Because the plaintiffs were successful in winning the case, the chiropractic profession made advancements in chiropractic education. Judge Getzendanner's injunction was key in restraining the AMA's attempts to thwart chiropractic education any further.52 Chiropractic schools benefitted from more professional diversity among their faculty and the injunction opened interprofessional opportunities for post-graduate training for chiropractors.

Chiropractic education had been criticized by organized medicine for lacking faculty members with graduate degrees in basic sciences to teach related courses and medical doctors to teach diagnosis, pathology, and other topics. Yet during its boycott, the AMA declared it unethical for a medical doctor to teach at a chiropractic institution. With the boycott, chiropractic college administrators were hard-pressed to hire the faculty members they needed. The court ruling in favor of the plaintiffs removed these barriers thereby improving chiropractic training programs.53 As Judge Getzendanner stated, “Finally, the AMA confirmed that a physician may teach at a chiropractic college or seminar.”52 Chiropractic colleges were now more attractive job prospects for non-chiropractors and the number of interprofessional faculty members increased at chiropractic colleges.

The end of the boycott likely allowed chiropractors to obtain graduate-level training after their chiropractic training. Chiropractors were able to apply for master's degrees and PhD programs without the discrimination against their chiropractic degrees that they previously experienced. Many chiropractors then brought their new skills back to chiropractic training programs, which enhanced their programs. After the judgment of the second trial, chiropractors were able to obtain graduate degrees from medical schools and universities in education, epidemiology, anatomy, chemistry, preventive medicine, and other fields. Before the injunction, such advances would have been very arduous, if not impossible.

The post-trial changes in chiropractic education were important for the public. The improved professional diversity of the faculty provided an educational environment where chiropractic students would learn to work with other health professionals. This training, even if it was implicit, enhanced the potential for chiropractors to work with medical doctors and other healthcare providers, making them better prepared to communicate with each other in the health care environment.

Patients benefit since excellent communication between providers enhances patient safety and improves health outcomes.20,54,55 Also, the increased quality of faculty meant that more thorough instruction was likely to be provided in courses important to the health of patients. This brought a higher level of patient care and safety to clinical practice, making graduates better equipped to serve the public.

The injunction also meant that chiropractors could become faculty members at universities and medical schools and contribute to health care in a broader manner than ever before. An early example is that of chiropractic radiologist Terry Yochum, DC, who was appointed to the faculty of the University of Colorado Medical School in 1991.53 He co-authored a textbook in skeletal radiology used by students, residents, and field doctors in multiple health care disciplines.56 Another example is Alan Adams, DC, MS, who was appointed to faculty positions at the University of Southern California and the University of California Irvine School of Medicine. It would have been unlikely for such a position to be filled by a chiropractor in the years during the AMA boycott.

Confirming the end of the boycott also meant that chiropractic educators could work more openly with educators from other disciplines, co-author educational research, and have such works cited by researchers in all fields. Interprofessional education is one part of a process that leads to better patient and public health outcomes.34,57 Chiropractic educators are now participating in the development of interprofessional education.58–61 Thus, chiropractic educators now make contributions that add to the betterment of health professions education and patient care everywhere.

Research

Research and science were core arguments during the trials. During the first trial, the AMA attacked the lack of a scientific basis for chiropractic. Before the lawsuit, minimal research activity occurred at chiropractic institutions and few indexed publications existed. Due to these criticisms about the lack of science and scientific approaches to practice, more chiropractic leaders began to seek out the inclusion of science in the chiropractic armamentarium.

Research and science were the new grounds on which the chiropractic profession could improve its practices and substantiate its claims. The profession stood to lose its identity and further alienate itself from the health sciences and the public if it was not assertive in encouraging significant improvements in research infrastructure and output of scientific papers.62 Therefore, there were increased efforts to develop a more mature chiropractic science.

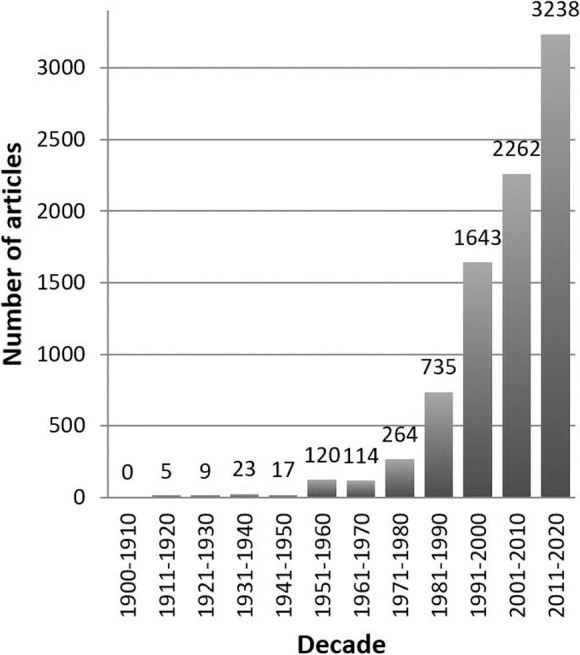

The research performed prior to the conclusion of the lawsuit was due to the steadfast commitment of a few members of the chiropractic profession. After the plaintiffs emerged victorious, there was phenomenal growth in chiropractic publications. For example, in a search of PubMed, the publicly accessible online database of research and scholarly articles, there were only 907 papers published that mention the word “chiropractic” from the beginning of the profession (1895) to the end of the trial (1987). Of these, most were negative propaganda as part of the effort to eliminate chiropractic. Distinct growth has been seen since that time. The number of citations including the term chiropractic/chiropractor has increased to more than 9000 as of 2021. This was also during a time of increased interest by organized medicine and the American public in complementary and alternative therapies. Thus, caution is needed to attribute too much association between the rise in publications and the lawsuit.

When asked about the policies of the AMA before the trials, Scott Haldeman, DC, MD, PhD, recounted:

The impact of these policies was that non-medically trained health care practitioners and scientists who were attempting to study what they were doing were unable to attend scientific medical meetings, obtain funding for research or even subscribe to medical journals, provide care in any medically controlled hospital or clinic, coordinate care, ask for help for their patients or even refer patients directly to a medical physician. This attitude was adopted throughout much of the so-called “modern or advanced” countries around the globe. In addition, by denying any research funding for, and ostracizing anyone involved in what is now known as integrative health care, organized medicine could continue to define these interventions as unscientific.63

After the lawsuit, chiropractors made substantive contributions to research and science in the field of musculoskeletal care (Fig. 1). This work has been used by all fields that care for patients with musculoskeletal problems, particularly the spine. Chiropractors have published research in major science journals and work collaboratively with professionals from nearly every health care discipline. Chiropractors have also contributed to health care in general by serving as officers and committee chairs in major organizations, such as the American Public Health Association, the North American Spine Society, and World Congress on Low Back Pain. Chiropractors can now be found presenting research at nearly every major spine-themed conference. Recently, chiropractors were a major force for the development and completion of the Global Spine Care Initiative, a research collaborative to reduce the global burden of disease and disability by bringing together leading healthcare scientists and specialists, government agencies, and other stakeholders to transform the delivery of spine care in underserved and low-income communities worldwide.15

Figure 1.

- The increasing number of published papers including the term “chiropractic” over time (figure used with permission from Brighthall).

It is possible that some of this remarkable progress was associated with the lawsuit. Three major stimuli that came from the lawsuit were: (1) funding for research from the settlement; (2) interdisciplinary collaboration in research; and (3) the increased likelihood to obtain federal research grants. These continue to show growth and promise not only for the chiropractic profession, but for other professions as well. Ultimately, such collaboration leads to scientific evidence to support best practices in quality patient care.

Dr Haldeman recalled the changes that he observed over time:

It took time for attitudes that had dominated the medical world to change. The official change in ethics and rules that governed health care opened doors and chiropractors and members of the other non-medical professions took advantage of these changes. Young chiropractors began going to graduate school and obtaining Ph.D. degrees in a variety of disciplines. Original research by these scientists, often in collaboration with mainstream medical scientists and clinicians, eventually began to appear in mainstream medical professions. As this research began showing a beneficial impact on an increasing list of health issues the value of these interventions began to be recognized.63

The England v Louisiana State Board of Medical Examiners trial of 1959 sought to establish the rights of chiropractors to practice in Louisiana; however, it was a heavy loss for the chiropractors.64 Dr Joseph Janse was the president of the National College of Chiropractic at that time and was provoked by his experience with that trial to establish the Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, a scientific journal indexed in PubMed.65 In a similar manner, the Wilk trial stimulated Dr James Winterstein, the following president of the National College (today's National University of Health Sciences) to support scientific publications and research for the chiropractic profession. Winterstein participated in the first Wilk trial, providing his deposition and testimony in court. His reflections on the trial included the following:

In 1987, I was called to be the expert witness on behalf of the chiropractic profession in the Wilk v American Medical Association trial. ... What I discovered during the second Wilk trial was that the issue of the “philosophical” basis of the chiropractic profession was at the foundation of the AMA's defense argument against chiropractic medicine as a way of claiming the AMA was protecting patients. I faced numerous questions that related directly to the philosophical component of the profession. Questions from the AMA lawyers revolved around the philosophical ideas that many in the chiropractic profession had proffered as a basis for human health and disease as it was understood by the members of the profession. At the center of these constructs was the theory of the effect of the vertebral subluxation, a theoretical entity that was purported by chiropractors to be the very foundation of human health and disease. As I responded to the AMA lawyers' questions related to this conundrum and the ways in which chiropractic doctors addressed human health and disease, it became clear to me that our profession needed a vehicle that would provide a venue for discussions related to the entire concept of “philosophy of chiropractic.” After the Wilk v American Medical Association trial was over, I reflected on the publications of our profession and was happy that we had a vehicle for publication of scientific research articles, but I felt that we lacked any kind of publication necessary for recording the ongoing thought processes expressed by members of the profession related to who we are and why we do what we do for our patients.65

After the trial was over, Winterstein was inspired to create 2 more scientific journals, one that would eventually become the Journal of Chiropractic Humanities, and another the Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, which are also indexed in PubMed.65,66

Chiropractic Today

Despite considerable obstacles, chiropractic not only survived, but now thrives. The chiropractic profession is one of the large licensed professions in the United States and continues to expand around the globe.67 Chiropractic is an American original, with a rich history dating back to 1895.68,69

Chiropractic is a licensed and regulated health care profession in all states and territories of the United States. Chiropractic provides conservative health care and focuses primarily on the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of musculoskeletal disorders and their effects on general health. Doctors of chiropractic are trained in assessment, diagnostic procedures, and in the monitoring of physical functions.70

In the United States, doctors of chiropractic practice as portal of entry providers and are qualified to serve as the first point of contact within the health care system without requiring a referral from other health providers. This means that patients have direct access to chiropractic care. Within the health care system, the majority of chiropractors work at a primary care level; however, some work at secondary or tertiary care levels. Chiropractors are trained to perform tasks typically associated with health care: history taking, physical examinations, ordering necessary diagnostic tests, and determining a diagnosis and management plan. Typical procedures include spinal manipulation, manipulation, and mobilization of peripheral joints and soft tissues, physiotherapeutic and rehabilitation techniques, lifestyle advice (eg, diet and exercise), and patient education.71 Chiropractors work in independent clinical practices or as part of health care teams in group or hospital settings.25,26,28,29,32,33

Chiropractic is considered to be “the largest alternate or ‘unorthodox' health profession in the United States.”72 According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Chiropractors care for patients with health problems of the neuromusculoskeletal system, which includes nerves, bones, muscles, ligaments, and tendons. They use spinal adjustments and manipulation, as well as other clinical interventions, to manage patients' health concerns, such as back and neck pain. Chiropractors focus on patients' overall health.”70

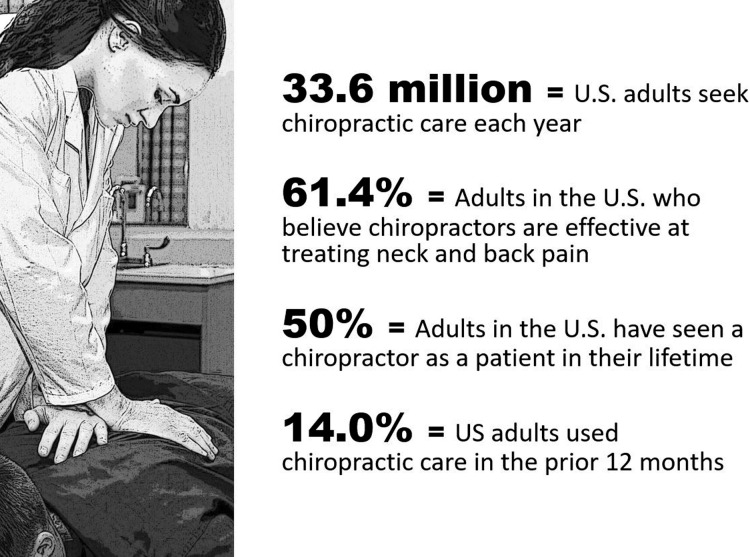

Chiropractic provides health care services to the public (Fig. 2).73–75 It is estimated that as of 2019, the majority of chiropractors in the world are located in the United States 77,000/103,469 (74.4%), followed by Canada 8500 (8.2%) and Australia 5277 (5.1%). The remaining 12,692 (12.2%) are spread across 87 other countries.67,76 Chiropractic is a licensed or registered profession in 68 countries67,77 and may be the only form of health care available in areas with limited resources.78 As of 2017, there are between 72,000 and 77,000 chiropractors in the United States.77 American chiropractors provide about 190,000,000 office visits annually79 and serve approximately 9%–15% of the American population.74,80

Figure 2.

- Findings from a Gallup poll about American adults' perceptions and use of chiropractors (figure used with permission from Brighthall).73

Chiropractic has been shaped by both internal and external forces. Legislation, culture, world events, and relationships with other health professions each have made their mark. Because chiropractic developed as an alternative to the medical practices of the late 1800s, its current approach to health and disease has been strikingly different from the approach of orthodox medicine. Chiropractic has evolved with a unique philosophy of health care that has focused its procedures on the healing of human ills mainly through manual means.53,81

From the beginning, chiropractors were concerned about the potential harmful effects of drugs and surgery. Central to the philosophy of chiropractic is the belief that the body is a self-regulating organism capable of healing itself if barriers are removed. Thus, chiropractors use natural methods, which aligns with the ideals and preferences of many people.82

A distinction of chiropractic care is that it provides mainstream health care with a drug-free/surgery-free option to include in the management of patients for certain conditions. This is particularly important in the management of chronic non-cancer pain since chiropractic can help to reduce the need for some medications by reducing pain naturally, which may help lower patients' dependence on opioid medications.83,84 In a dramatic difference to the previous exclusion of chiropractic in accredited hospitals before the trial, the Joint Commission recently included chiropractic as one non-pharmacologic strategy recommended for the management of pain in its new standard.85 The Joint Commission (formerly the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations) accredits more than 21,000 US health care organizations and programs.86

Chiropractors are appreciated by their patients and have demonstrated high patient satisfaction rates for decades.79,87–92 When surveyed, most people say that they feel that chiropractors approach their patients from a holistic perspective, considering not just the body part of concern, but many facets of a patient's overall health that affect wellness, which represents a biopsychosocial view. In general, chiropractors encourage healthy lifestyles and health promotion as part of their practice. Chiropractors involve patients in making choices about their health care (ie, patient-centered care), and provide an alternative choice for people with regard to their health, as described in the 9th Amendment of the US Constitution.93 Most chiropractors work in partnership with their patients, treating patients with respect. Chiropractors tend to avoid the subservient doctor–patient relationship, which is a style that has traditionally been found in the more paternalistic biomedical approaches of orthodox medicine until recent times.94

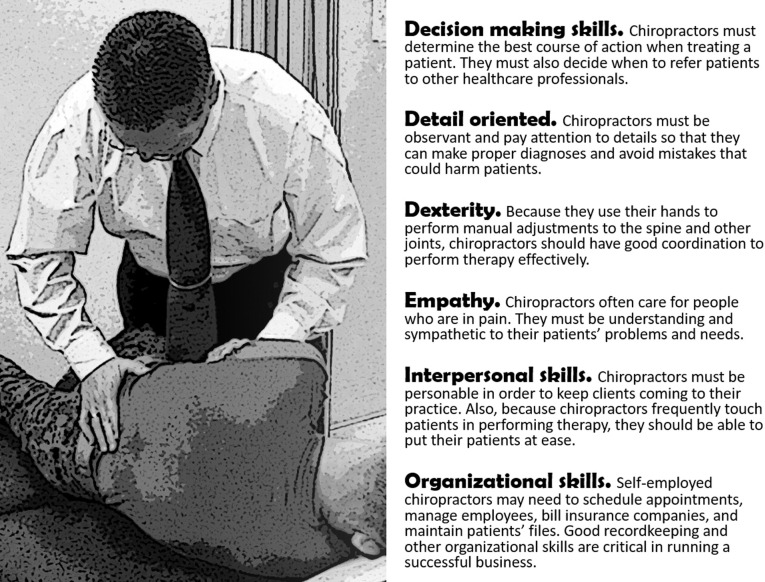

Given that the primary treatment used in chiropractic practice requires touching the patient, building trust with people is essential for chiropractors. Although trust and communication are favored by patients, appropriate time is required to create such a therapeutic alliance and is more than merely performing a procedure. This is beneficial not only to private practitioners but to interprofessional health care environments. A leading indicator of satisfaction with health care is the amount of time a doctor spends with his or her patients.95,96 When chiropractors work in interprofessional environments, their holistic and cooperative methods can enhance patient satisfaction with an entire clinic or hospital, which helps the team (Fig. 3).70

Figure 3.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics list of important qualities for doctors of chiropractic (figure used with permission from Brighthall).70

Patients may benefit from access to chiropractic care in many health care environments. Most chiropractors work in private offices and clinics.77 At present, chiropractors also work with other health care providers such as medical doctors, osteopaths, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, physical therapists, and acupuncturists to provide the best possible health care to patients. Demonstrating the demand for chiropractic services by the public and the ability of chiropractors to work collaboratively with other health care providers in complex settings, a rapidly growing number of chiropractors have been recruited to work in interprofessional environments.29,30,32 Chiropractors in the United States can be found in private and public hospitals and clinics,25,97 the Military Health System,28,32 the Veterans' Administration,26,98,99 corporate health clinics,100,101 and charity clinics.102,103

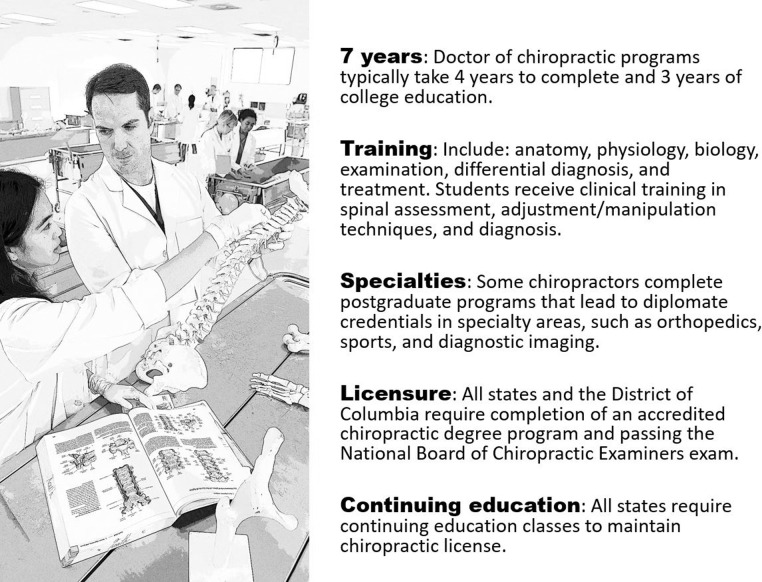

Evidence shows that spinal manipulation is one of the first treatments that should be considered in the management of back pain.16,104–107 A common treatment used by chiropractors, joint manipulation (in chiropractic vernacular, “adjustment”), is often sought out by patients for its pain-relieving factors, calming effects, and ability to restore function. Chiropractors have the most training in manipulation of any health care provider and provide more than 90% of manipulative care in the United States (Fig. 4).70,108,109 Chiropractors provide unique and effective care for musculoskeletal conditions, especially spine dysfunction and pain.

Figure 4.

- Facts on Chiropractic. US Bureau of Labor Statistics information about education and licensure for doctors of chiropractic in the US (figure used with permission from Brighthall).70

Other benefits of chiropractic care have shown cost-effectiveness for the treatment of chronic low back pain. 110 Another consideration is that chiropractic care offers a drug-free alternative, and therefore may reduce the risk for opioid or other drug addiction for managing certain musculoskeletal conditions.111–113

In the United States, doctors of chiropractic give and receive referrals from medical doctors and other health care providers, order diagnostic services at hospitals, and join hospital medical staffs. There have been collaborations between doctors of chiropractic and doctors of medicine and osteopathy in education and research, and chiropractic institutions have received federal research funding. Chiropractors within integrated health care settings have demonstrated high levels of collaboration and cooperation in health care delivery to patients. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, chiropractic continues to grow. “Employment of chiropractors is projected to grow 12 percent from 2016 to 2026, faster than the average for all occupations.”70

DISCUSSION

This historical report of chiropractic and the lawsuit helps us better understand how chiropractic became what it is today and how the remnants of the boycott from decades ago may affect current events.

One may wonder if chiropractic would be different today without the successful outcome of the Wilk v AMA lawsuit and to what extent the judge's decision made a difference. However, it is impossible to say with any certainty. Chiropractic has continued to improve since its beginning in 1895, despite the many internal and external challenges it has faced. Yet how and why chiropractic has grown after 1990 could be associated with a variety of factors and not necessarily connected with any certitude to a trial decision or other lawsuit-related event.

What we do know is that after the trial decision, chiropractors slowly began to participate in activities that were typically expected of health professionals and these activities might be associated with chiropractic growth. Based on the findings presented in this paper, there seems to be a temporal association between the judge's final decision in favor of the plaintiffs and what was likely a positive impact on the chiropractic profession, especially in the areas of clinical practice, education, and research. However, we must be careful not to over-attribute these changes to this singular trial. There were other profession-wide efforts, campaigns, and legal events, including other lawsuits such as the England v Louisiana trial and others, that contributed to the transformation.43,64,65,114,115

We must be pragmatic when considering the social and cultural environment in which chiropractic was struggling to be established. Over the past century, the AMA had built the infrastructure of the American health care system that placed medical doctors at the center of that paradigm. The hospital system, medical education, research, public health, and reimbursement were all developed and controlled either directly or indirectly by the AMA. Organized medicine created health care in the US in its own image and therefore controlled what types of providers were allowed to practice in to “their” house. It is therefore logical that leaders in orthodox medicine felt justified when denying a non-medical professional admission to the medical structure that they had developed. Meanwhile, the non-medical professionals who were trying to participate likely felt indignation and discrimination when they were not allowed into the medical structure.

Health care in America has changed since that time through various social, economic, and political forces. The old rules no longer apply. Thus, while organized medicine is still in a position of power, it no longer has the absolute control over healthcare as it once did.116 The benefits of multi-professional care and providing patients options has shown promise. We can provide better health care with a collaborative approach to helping patients.54,55

The lawsuit revealed a concerted effort to eradicate chiropractic in the United States over the past century. This hostile environment created challenges that we still face today. It is not surprising that we continue to see lingering effects from the boycott. As explained by Gerard Clum, DC:

Just as racism in the United States did not cease to exist because the Civil Rights Act was enacted into law, the decision of Judge Getzendanner did not change the hearts and minds of opponents of the profession. The present-day senior leadership of organized medicine was trained in an era that was hostile to the chiropractic profession. The subconscious remnants of this time remain a part of the reality of today's chiropractic profession. This institutionalized bias may only be displaced over time if we continue to try to improve the quality of chiropractic education and the amount of research needed to practice using scientific evidence.117

Thus, the remnants of the earlier conflict still exist like a ghost trapped in the beliefs and values of the American public. It is not clear the amount of damage that nearly a century of persecution by organized medicine may have exacted on the chiropractic profession and the public or how long this might last.

These battles created entrenched beliefs and bitter memories for many in both professions. Medical doctors who were indoctrinated by the AMA during that era likely retained old biases, especially if they were not informed otherwise. Chiropractors who were trained or practiced before the 1990s were exposed to the harsh effects of the boycott and likely developed a sense of mistrust or aversion to organized medicine. To survive, chiropractors had to learn how to fight back to defend themselves, and the rebel mindset may still exist even if the danger may no longer be present.

The American public was largely unaware that they had been exposed to nearly a century of anti-chiropractic propaganda. This has left the public without a clear understanding about the benefits, safety, or effectiveness of chiropractic care. Because orthodox medicine had indoctrinated the public that non-medical health professions, including chiropractic, were unfit, people seeking alternative care may have had to rely on their “beliefs” and to have “faith that chiropractic works” to navigate these conflicting views.118 As time marches on and the American population diversifies, perhaps the still palpable tensions will eventually wane. It may be many more years before respect, inclusion, and equity are fulfilled among the professions.

The stigma that surrounded chiropractic was not caused by a singular source either; instead, it was created by a combination of factors. How chiropractors advertised and defended themselves against attacks contributed, in part, to their stigmatization. Undoubtedly, part of the stigma was crafted by organized medicine in their propaganda campaigns and attempts to reach the prime directive of the AMA, to “contain and eliminate chiropractic.”

We must also be mindful about keeping history in its proper perspective. Orthodox medicine's practices had evolved from bloodletting and purging and medical physicians earning their degrees after only 6 months to improved education and more developed methods ruled by science. Similarly, chiropractic has also advanced in its methods and quality of education. However, US medicine had a head start and more resources, so if comparing within any given decade, it is expected that the medical profession would be more advanced compared to chiropractic as it had more time to develop. And, despite the suppression and the organized boycott by the AMA, chiropractic remained separate and distinct as its own profession and has greatly improved in a relatively short amount of time of its comparative existence. And, as medicine does within its own ranks, chiropractic works to address unethical practice behaviors, unsubstantiated claims, and to improve its science and practice for the public's health.12,13,119,120

Those both internal and external to chiropractic should avoid making the same mistakes that the AMA Committee on Quackery made. They did not collect all the facts and had a predetermined outcome that their limited view of chiropractic was correct, when in fact, it was not. It is the authors' observation that there are some who may be working with inaccurate or outdated information and have not yet been properly informed about what modern chiropractic is or what the majority of chiropractors do. One should avoid describing the chiropractic of today using inaccurate information from decades ago. In a similar fashion, it would be incorrect to describe medical practices from the mid-1900s as if they were current. As well, all professions have their fringe elements, thus it is important not to paint an entire profession using exceptions as if they were the rule. More efforts should be made to provide accurate information about the current training, certification, and scope of practice for chiropractors.109 For example, practice analysis data as of 2020 show that the overwhelming majority of chiropractors in the United States support scientific and evidence-based practices.109 So to claim that all of chiropractic is unscientific would be inaccurate and archaic.

Chiropractic also has a unique approach to health care that needs to be better valued and appreciated. People both internal and external to chiropractic have made claims about what the profession does but may not have taken the time to understand the full value of the unique terminology and approaches that chiropractic offers. The vernacular of the chiropractic profession was developed, in part, to protect its existence and to establish that it was distinct from medicine. Some of these chiropractic concepts have been used by chiropractors beginning as early as 1895, such as focusing on the whole person, mind–body connections, patient-centeredness, biopsychosocial interactions, and the body's innate ability to heal, have tremendous value and have yet to be explored fully through qualitative and quantitative research. However, it now seems as if other health professions are discovering these concepts for the first time. And yet, these concepts have been with chiropractors all along having been core components of chiropractic principles for over 100 years. Medicine borrows these concepts and incorporates them into their curricula under the term “integrated medicine.”27,35 However, we propose that credit should be given where credit is due. Further education of historical events and improved dialogue between the health professions may provide greater clarity and offer some solutions to this conundrum. Our authors' experience has been that with better communications and greater understanding comes greater respect.

As stated when we started this historical review, “Looking back at the path that we have traveled provides insight into our present and gives us the wisdom to navigate our future. Although it may seem paradoxical, to move ahead, we must start by looking back.”121 By sharing the history surrounding this lawsuit, we are given insight into what chiropractic is and perhaps where this profession needs to go. As is shown in this paper, the quality of chiropractic education continues to improve, and the scientific evidence steadily builds for chiropractic care. It is imperative for the chiropractic profession to continue to improve to meet its most fundamental mission, which is to improve the lives of people.

We also honor those who have made sacrifices for the chiropractic profession, ranging from patients to chiropractors including the plaintiffs Drs Patricia Arthur, James Bryden, Michael Pedigo, and Chester Wilk, and those from other professions including Mr George McAndrews and Judge Susan Getzendanner. (Figs. 5, 6, and 7)122,123 To continue to respect those who have come before us, we must continue to uphold the public's trust. The Wilk v AMA lawsuit removed a barrier. It is now the responsibility of the present-day members of the chiropractic profession to remember these events, learn from the past, and to make a better tomorrow.

Figure 5.

- The plaintiffs (from left to right) Michael Pedigo James Bryden, Chester Wilk, and Patricia Arthur.

Figure 6.

- George McAndrews, the lead attorney for the plaintiffs.

Figure 7.

- Judge Susan Getzendanner, presided over the second trial.

It is our hope that decades from now, when others are looking back at the interactions between medicine and chiropractic, that they will see respectful partners focused on creating a better future for the health of the public. Chiropractors practicing in the United States today are indebted to those who engaged in the trial and all those who persisted in supporting their profession. Patients receiving chiropractic care today benefit from this care because of the dedicated efforts of many people. Now the future of the chiropractic profession rests in the heads, hearts, and hands of its current members to do what is right.

Limitations

This historical narrative reviews events from the context of the chiropractic profession and the viewpoints are limited by the authors' framework and worldview. Other interpretations of historic events may be perceived differently by other authors. The context of this paper must be considered in light of the authors' biases as licensed chiropractic practitioners, educators, and scientific researchers.

The primary sources of information were written testimony, oral interviews, public records, legal documents, minutes of meetings, newspapers, letters, and other artifacts. These formed the basis for our narrative and timeline. We acknowledge that recall bias is an issue when referencing sources, such letters where people recount past events. Secondary sources, such as textbooks, trade magazines, and peer-reviewed journal articles, were used to verify and support the narrative. We collected thousands of documents and reconstructed the events relating to the Wilk v AMA lawsuit. Since no electronic databases exist that index many of the publications needed for this research, we conducted page-by-page hand searches of decades of publications. Although it is possible that we missed some important details, great care was taken to review every page systematically for information. It is possible that we missed some sources of information and that some details of the trials and surrounding events were lost in time. The aforementioned potential limitations may have affected our interpretation of the history of these events.

Some of our sources were interviews, manuscripts, or letters where the author recalled past events. Recall bias is an issue when referencing interview sources. Surviving documents from the first 80 years of the chiropractic profession, the years leading up to the Wilk v AMA lawsuit, are scarce. Chiropractic literature existing before the 1990s is difficult to find since most of it was not indexed. Many libraries have divested their holdings of older material, making the acquisition of early chiropractic documents challenging. While we were able to obtain some sources from libraries, we also relied heavily upon material from our own collection and materials from colleagues. Thus, there may be relevant papers or artifacts that were inadvertently missed. Our interpretation of the events related to the trials is limited to the materials available. The information regarding this history is immense and due to space limitations, not all parts of the story could be included in this series.

CONCLUSION

The quality of chiropractic practice, education, and the research continues to grow. It is imperative for the chiropractic profession to continue to improve to meet its most fundamental mission: to improve the lives of patients. The lawsuit removed some barriers that were implemented by organized medicine against the chiropractic profession.

It is up to the present-day members of the medical and chiropractic professions to look back and to remember what happened. By recalling the events leading up to and resulting from the lawsuit, we can have improved insight into our professions today. It is our hope that in the future, when others are looking back at the interactions between medicine and chiropractic, they see respectful partners focused on creating a better future for the health of the public.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the following people for their detailed reviews and feedback during development of this project: Ms Mariah Branson, Dr Alana Callender, Dr Cindy Chapman, Dr Gerry Clum, Dr Scott Haldeman, Mr Bryan Harding, Mr Patrick McNerney, Dr Louis Sportelli, Mr Glenn Ritchie, Dr Eric Russell, Dr Randy Tripp, Mr Mike Whitmer, Dr James Winterstein, Dr Wayne Wolfson, and Dr Kenneth Young.

FUNDING AND CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

This project was funded, and copyright owned by NCMIC. The views expressed in this article are only those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the NCMIC, National University of Health Sciences, or the Association of Chiropractic Colleges. BNG is the editor in chief of the Journal of Chiropractic Education and CDJ is on the NCMIC board and the editorial board of the Journal of Chiropractic Education. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wilk v AMA No. 87-2672 and 87-2777 (F. 2d 352 Court of Appeals 7th Circuit April 25. 1990).

- 2.Keating JC, Jr, Green BN, Johnson CD. “Research” and “science” in the first half of the chiropractic century. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1995;18(6):357–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haldeman S, Chapman-Smith D, Petersen DM. Guidelines for Chiropractic Quality Assurance and Practice Parameters proceedings of the Mercy Center Consensus Conference. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishing; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson C. What is the Association of Chiropractic Colleges Educational Conference and Research Agenda Conference? J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2007;30(4):249–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson C, Green B. The Association of Chiropractic Colleges Educational Conference and Research Agenda Conference: 17 years of scholarship and collaboration. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33(3):165–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mootz RD, Hansen DT, Breen A, Killinger LZ, Nelson C. Health services research related to chiropractic: review and recommendations for research prioritization by the chiropractic profession. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(9):707–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haas M, Bronfort G, Evans RL. Chiropractic clinical research: progress and recommendations. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(9):695–706. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mrozek JP, Till H, Taylor-Vaisey AL, Wickes D. Research in chiropractic education: an update. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(9):762–773. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cramer G, Budgell B, Henderson C, Khalsa P, Pickar J. Basic science research related to chiropractic spinal adjusting: the state of the art and recommendations revisited. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(9):726–761. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bigos SJ, Bowyer OR, Braen GR, et al. Acute low back problems in adults. Acute Lower Back Problems in Adults. Clinical Practicei Guidelines No. 14. AHCPR Publication No. 95-0642. Rockville Md US Dept of Health and Human Services Public Health Service Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1994.

- 11.Haldeman S, Carroll L, Cassidy JD, Schubert J, Nygren A. The Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders: executive summary. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(2 Suppl):S7–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson C, Baird R, Dougherty PE, et al. Chiropractic and public health: current state and future vision. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(6):397–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson C, Green BN. Public health, wellness, prevention, and health promotion: considering the role of chiropractic and determinants of health. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(6):405–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Egan J, Baird R, Killinger L. Chiropractic within the American Public Health Association, 1984–2005: pariah, to participant, to parity. Chiropr Hist. 2006;26:97–117. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haldeman S, Nordin M, Chou R, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: World Spine Care executive summary on reducing spine-related disability in low- and middle-income communities. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(Suppl 6):776–785. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5722-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green BN, Johnson CD, Haldeman S, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: public health and prevention interventions for common spine disorders in low- and middle-income communities. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(Suppl 6):838–850. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5635-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson CD, Haldeman S, Nordin M, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: methodology, contributors, and disclosures. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):786–795. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5723-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haldeman S, Johnson CD, Chou R, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: care pathway for people with spine-related concerns. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):901–914. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5721-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haldeman S, Johnson CD, Chou R, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: classification system for spine-related concerns. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):889–900. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5724-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson CD, Haldeman S, Chou R, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: model of care and implementation. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(6):925–945. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5720-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green BN, Johnson CD, Haldeman S, et al. A scoping review of biopsychosocial risk factors and co-morbidities for common spinal disorders. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0197987. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boon H, Verhoef M, O'Hara D, Findlay B, Majid N. Integrative healthcare: arriving at a working definition. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004;10(5):48–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawk C, Nyiendo J, Lawrence D, Killinger L. The role of chiropractors in the delivery of interdisciplinary health care in rural areas. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1996;19(2):82–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lott CM. Integration of chiropractic in the Armed Forces health care system. Mil Med. 1996;161(12):755–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Branson RA. Hospital-based chiropractic integration within a large private hospital system in Minnesota: a 10-year example. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):740–748. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green BN, Johnson CD, Lisi AJ, Tucker J. Chiropractic practice in military and veterans health care: the state of the literature. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2009;53(3):194–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boon HS, Mior SA, Barnsley J, Ashbury FD, Haig R. The difference between integration and collaboration in patient care: results from key informant interviews working in multiprofessional health care teams. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dunn AS, Green BN, Gilford S. An analysis of the integration of chiropractic services within the United States military and veterans' health care systems. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):749–757. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldberg CK, Green B, Moore J, et al. Integrated musculoskeletal rehabilitation care at a comprehensive combat and complex casualty care program. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):781–791. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lisi AJ, Goertz C, Lawrence DJ, Satyanarayana P. Characteristics of Veterans Health Administration chiropractors and chiropractic clinics. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46(8):997–1002. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2009.01.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hawk C. Integration of chiropractic into the public health system in the new millenium. In: Haneline MT, Meeker WC, editors. Introduction to Public Health for Chiropractors. Boston: Jones and Bartlett; 2010. pp. 375–389. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green BN, Johnson CD, Daniels CJ, Napuli JG, Gliedt JA, Paris DJ. Integration of chiropractic services in military and veteran health care facilities: a systematic review of the literature. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2016;21(2):115–130. doi: 10.1177/2156587215621461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salsbury SA, Goertz CM, Twist EJ, Lisi AJ. Integration of doctors of chiropractic into private sector health care facilities in the United States: a descriptive survey. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018;41(2):149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Green BN, Johnson CD. Interprofessional collaboration in research, education, and clinical practice: working together for a better future. J Chiropr Educ. 2015;29(1):1–10. doi: 10.7899/JCE-14-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson C. Health care transitions: a review of integrated, integrative, and integration concepts. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(9):703–713. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirschheim R, Klein HK. Four paradigms of information systems development. Communications of the ACM. 1989;32(10):1199–1216. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Porra J, Hirschheim R, Parks MS. The historical research method and information systems research. J Assoc Info Syst. 2014;15(9):3. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lune H, Berg BL. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. Harlow, UK: Pearson; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 2: Rise of the American Medical Association. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):25–44. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 3: Chiropractic growth. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):45–54. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 4: Committee on Quackery. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S):55–73. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 5: Evidence exposed. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):74–84. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 6: Preparing for the lawsuit. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):85–96. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession Part 7: Lawsuit and decisions. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;2021(S1):97–116. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession part 1: Origins of the conflict. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):9–24. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.The Herald Statesman. 1936. Legionnaires Urge Chiropractors For Veterans' Hospitals. September 23, 1936.

- 47.US Congress. Appointment of Doctors of Chiropractic in the Veterans' Administration Hearing Eightyfirst Congress Second Session on HR 1512. 1950. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- 48.Kranz K. Hospital access. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 1988;32(2):65–69. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kranz KC. Chiropractic and Hospital Privileges Protocol. Washington, DC: International Chiropractors Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johnson C, Green B. Interview of Susan Getzendanner. 2016. November 20.

- 51.Statement of the American Hospital Association with respect to the profession of chiropractic and hospitals. Hospitals. 1987;61:80. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Getzendanner S. Permanent injunction order against AMA. JAMA. 1988;259(1):81–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wardwell WI. Chiropractic History and Evolution of a New Profession. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 54.American Medical Association. Collaborative Care: Code of Medical Ethics Opinion 10.8. 2021 https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/collaborative-care Published 2021. Accessed March 7.

- 55.Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson MS. To err is human building a safer health system. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yochum TR, Rowe LJ. Essentials of Skeletal Radiology. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 57.World Health Organization. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kadar GE, Vosko A, Sackett M, Thompson HG. Perceptions of interprofessional education and practice within a complementary and alternative medicine institution. J Interprof Care. 2015;29(4):377–379. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2014.967337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goldblatt E, Wiles M, Schwartz J, Weeks J. Competencies for optimal practice in integrated environments: examining attributes of a consensus interprofessional practice document from the licensed integrative health disciplines. Explore. 2013;9(5):285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Karim R. Building interprofessional frameworks through educational reform. J Chiropr Educ. 2011;25(1):38–43. doi: 10.7899/1042-5055-25.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bednarz EM, Lisi AJ. A survey of interprofessional education in chiropractic continuing education in the United States. J Chiropr Educ. 2014;28(2):152–156. doi: 10.7899/JCE-13-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Goldstein M. N.I.H. What it is, how it works, and how its programs can benefit the chiropractic profession. Int Rev Chiropr. 1980;34(3):34–37. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Haldeman S. Johnson C, editor. E-mail correspondence. 2018. In. ed.

- 64.England v Louisiana State Board of Medical Examiners 263 F2d 661 (US Circ. 1959).

- 65.Winterstein J. Journal of Chiropractic Humanities: a Celebration of 25 Volumes. J Chiropr Humanit. 2018;25:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.echu.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Winterstein J. Expanding our vision. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine. 2002;1(1):1. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60020-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stochkendahl MJ, Rezai M, Torres P, et al. The chiropractic workforce: a global review. Chiropr Man Therap. 2019;27:36. doi: 10.1186/s12998-019-0255-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Keating JC, Cleveland CS, Menke M. Chiropractic History A Primer. Davenport, Iowa: Association for the History of Chiropractic; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Johnson CD. Chiropractic Day: a historical review of a day worth celebrating. J Chiropr Humanit. 2020;27:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.echu.2020.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Outlook Handbook: Chiropractors. 2021 https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/chiropractors.htm Published 2020. Updated September 1, 2020. Accessed February 14.

- 71.Green BN, Johnson CD, Dunn AS. Chiropractic in veterans' healthcare. In: Miller T, editor. Veterans Health Resource Guide. Santa Barbara: Praeger Publishing; 2012. pp. 135–156. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Coulehan JL. Adjustment, the hands and healing. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1985;9(4):353–382. doi: 10.1007/BF00049230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gallup Inc. Gallup–Palmer College of Chiropractic Inaugural Report Americans' Perceptions of Chiropractic. 2016. Washington, DC: Gallup Inc.

- 74.Weeks WB, Goertz CM, Meeker WC, Marchiori DM. Characteristics of US adults who have positive and negative perceptions of doctors of chiropractic and chiropractic care. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(3):150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Weeks WB, Goertz CM, Meeker WC, Marchiori DM. Public perceptions of doctors of chiropractic: results of a national survey and examination of variation according to respondents' likelihood to use chiropractic, experience with chiropractic, and chiropractic supply in local health care markets. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015;38(8):533–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Johnson CD, Green BN, Konarski-Hart KK, et al. Response of practicing chiropractors during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: a descriptive report. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2020;43(5):e401–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Christensen MG, Hyland JK, Goertz CM, Kollasch MW. Practice Analysis of Chiropractic 2015 A Project Report Survey Analysis and Summary of Chiropractic Practice in the United States. Greeley, Colorado: National Board of Chiropractic Examiners; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Johnson CD, Green BN. Overview of chiropractic health care. In: Hawk C, editor. The Praeger Handbook of Chiropractic Health. Santa Barbara: Praeger; 2017. pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Meeker W, Haldeman S. Chiropractic: a profession at the crossroads of mainstream and alternative medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:216–227. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Peregoy JA, Clarke TC, Jones LI, Stussman BJ, Nahin RL. Regional variation in use of complementary health approaches by U.S. adults. NCHS Data Brief. 2014;(146):1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Coulter ID. Chiropractic A Philosophy for Alternative Health Care. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Johnson CD, Green BN. Chiropractic care. In: Lavretsky H, Sajatovic M, Reynolds C, editors. Complementary Alternative and Integrative Interventions in Mental Health and Aging. New York: Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kazis LE, Ameli O, Rothendler J, et al. Observational retrospective study of the association of initial healthcare provider for new-onset low back pain with early and long-term opioid use. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):e028633. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Weeks WB, Goertz CM, Long CR, Meeker WC, Marchiori DM. Association among opioid use, treatment preferences, and perceptions of physician treatment recommendations in patients with neck and back pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018;41(3):175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.The Joint Commission. Clarification of the pain management standard. Joint Commission Perspect. 2014;34(11):11. [Google Scholar]

- 86.The Joint Commission. History of The Joint Commission. 2019 https://www.jointcommission.org/about_us/history.aspx Published 2019. Accessed October 6.

- 87.Leininger BD, Evans R, Bronfort G. Exploring patient satisfaction: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial of spinal manipulation, home exercise, and medication for acute and subacute neck pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014;37(8):593–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sawyer CE, Kassak K. Patient satisfaction with chiropractic care. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1993;16(1):25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Weigel PA, Hockenberry JM, Wolinsky FD. Chiropractic use in the Medicare population: prevalence, patterns, and associations with 1-year changes in health and satisfaction with care. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2014;37(8):542–551. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gemmell HA, Hayes BM. Patient satisfaction with chiropractic physicians in an independent physicians' association. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24(9):556–559. doi: 10.1067/mmt.2001.118980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Solomon DH, Bates DW, Panush RS, Katz JN. Costs, outcomes, and patient satisfaction by provider type for patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal conditions: a critical review of the literature and proposed methodologic standards. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(1):52–60. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-1-199707010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Johnson MR, Schultz MK, Ferguson AC. A comparison of chiropractic, medical and osteopathic care for work-related sprains and strains. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1989;12(5):335–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.US Constitution Amendment IX

- 94.Häyry H. The Limits of Medical Paternalism. London; New York: Routledge; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Maiers M, Hondras MA, Salsbury SA, Bronfort G, Evans R. What do patients value about spinal manipulation and home exercise for back-related leg pain? A qualitative study within a controlled clinical trial. Man Ther. 2016;26:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Etier BE, Jr, Orr SP, Antonetti J, Thomas SB, Theiss SM. Factors impacting Press Ganey patient satisfaction scores in orthopedic surgery spine clinic. Spine J. 2016;16(11):1285–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bronston LJ, Austin-McClellan LE, Lisi AJ, Donovan KC, Engle WW. A survey of American Chiropractic Association members' experiences, attitudes, and perceptions of practice in integrated health care settings. J Chiropr Med. 2015;14(4):227–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Green BN, Johnson CD, Lisi AJ. Chiropractic in U.S. military and veterans' health care. Mil Med. 2009;174(6):vi–vii. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-01-9908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lisi AJ, Brandt CA. Trends in the use and characteristics of chiropractic services in the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2016;39(5):381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Foundation for Chiropractic Progress. The Growing Role of Doctors of Chiropractic in Onsite Corporate Health Clinics. Georgetown: Foundation for Chiropractic Progress; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kindermann SL, Hou Q, Miller RM. Impact of chiropractic services at an on-site health center. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(9):990–992. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Brady O, Nordin M, Hondras M, et al. Global forum: Spine research and training in underserved, low and middle-income, culturally unique communities: The World Spine Care charity research program's challenges and facilitators. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(24):e110. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.00723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kaeser MA, Hawk C, Anderson ML, Reinhardt R. Community-based free clinics: opportunities for interprofessional collaboration, health promotion, and complex care management. J Chiropr Educ. 2016;30(1):25–29. doi: 10.7899/JCE-15-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Paige NM, Miake-Lye IM, Booth MS, et al. Association of spinal manipulative therapy with clinical benefit and harm for acute low back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2017;317(14):1451–1460. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.3086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chou R. Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(8):606–607. doi: 10.7326/L17-0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chou R, Cote P, Randhawa K, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: applying evidence-based guidelines on the non-invasive management of back and neck pain to low- and middle-income communities. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(Suppl 6):851–860. doi: 10.1007/s00586-017-5433-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Johnson CD, Haldeman S, Chou R, et al. The Global Spine Care Initiative: model of care and implementation. Eur Spine J. 2018. pp. 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 108.Shekelle PG, Adams AH, Chassin MR, Hurwitz EL, Brook RH. Spinal manipulation for low-back pain. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117(7):590–598. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-7-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Himelfarb I, Hyland J, Ouzts N. Practice Analysis of Chiropractic 2020. 2020 https://www.nbce.org/practice-analysis-of-chiropractic-2020/ Published 2020. Accessed September 18.

- 110.Haas M, Sharma R, Stano M. Cost-effectiveness of medical and chiropractic care for acute and chronic low back pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28(8):555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Whedon JM, Toler AW, Goehl JM, Kazal LA. Association between utilization of chiropractic services for treatment of low back pain and risk of adverse drug events. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018;41(5):383–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Corcoran KL, Bastian LA, Gunderson CG, Steffens C, Brackett A, Lisi AJ. Association between chiropractic use and opioid receipt among patients with spinal pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Medicine. 2020;21(2):e139–e145. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnz219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Whedon JM, Toler AW, Kazal LA, Bezdjian S, Goehl JM, Greenstein J. Impact of chiropractic care on use of prescription opioids in patients with spinal pain. Pain Med. 2020;21(12):3567–3573. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnaa014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.NJ Chiropractic Soc v. Radiological Soc 383 1182 (NJ: Superior Court, Chancery Div. 1978).

- 115.Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation. In re chiropractic antitrust litigation. 1980;483 F(Supp. 402):811–812. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ameringer CF. The Health Care Revolution From Medical Monopoly to Market Competition Vol 19. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Clum G. Personal communication with Claire Johnson July 14. 2019.

- 118.Robinson A, McGrail MR. Disclosure of CAM use to medical practitioners: a review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Complement Ther Med. 2004;12(3–4):90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Johnson C. Keeping a critical eye on chiropractic. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(8):559–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Johnson C, Rubinstein SM, Cote P, et al. Chiropractic care and public health: Answering difficult questions about safety, care through the lifespan, and community action. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2012;35(7):493–513. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Johnson CD, Green BN. Looking Back at the lawsuit that transformed the chiropractic profession: Authors' introduction. J Chiropr Educ. 2021;35(S1):5–8. doi: 10.7899/JCE-21-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Quade V. Women in the law: twelve success stories. Am Bar Assoc J. 1983;69(10):1400–1412. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Picture of George McAndrews. ACA J Chiropr. 1987;24(11) front cover. [Google Scholar]