Abstract

Background:

The rapid growth of consumer sleep technology demonstrates the population’s interest in measuring sleep. However, the extent to which these devices can be used in the delivery behavioral sleep interventions is currently unknown. The objectives of this systematic review was to evaluate the use of consumer sleep technology (wearable and mobile) in behavioral sleep medicine interventions, identify gaps in the literature and potential future directions.

Methods:

We completed a scoping review of studies conducted in adult populations that used consumer sleep tracking technology to deliver sleep-related interventions.

Results:

Our initial search returned 4,538 articles and 14 articles met our inclusion/exclusion criteria. Results demonstrated that wearable devices are being used for 2 main purposes: 1. To deliver treatment for insomnia and 2. Sleep monitoring as part of overall wellness programs. Half of the articles reviewed (n=7) used consumer sleep technology in a cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. The majority of the studies reviewed (n=10) were fully digital, without human intervention and only two small studies evaluated interventions delivered with and without a sleep tracking device.

Conclusions:

These studies demonstrate opportunities to utilize consumer sleep trackers in insomnia treatment and wellness programs, but most new and innovative interventions are in the early, feasibility stages. Future research is needed to determine how to leverage wearables to improve existing behavioral sleep treatments and determine how this technology can engage patients and reduce barriers to behavioral sleep medicine interventions.

Keywords: consumer sleep technology, insomnia, sleep, wearable devices

Introduction

Use of consumer sleep technology is rapidly growing and is substantially changing the field of behavioral sleep medicine. It is estimated that nearly 57 million adults in the US own a fitness tracker and the market is continuing to expand among all age groups, including adults >55 (eMarketer, 2018). Therefore sleep technology is relevant across the lifespan. Sleep tracking apps are consistently in the top selling fitness apps (Analytics, 2018). Therefore, based on consumer trends, the public is intently interested in their sleep. Indeed, according to our survey data of individuals with short sleep duration, nearly all of the respondents (85%) were interested in a wearable sleep tracker to improve their sleep (Adkins et al., 2019).

The increase in the use of consumer sleep technology provides opportunity to engage patients and the public in evaluating and improving their sleep. Considering that tracking sleep using sleep logs is one of the foundational tools in behavioral sleep medicine, these devices have the potential to provide an accessible way for individuals to self-monitor their sleep and even perhaps share this data with their medical team. However, it is currently unknown how the use of consumer sleep technology can be used for delivering behavioral sleep interventions.

In our prior review of consumer sleep technology, entitled “Feeling validated yet?”(2018), we explored how consumer sleep technologies were being used in the research literature. Although we had set out to specifically review behavioral interventions, this review demonstrated that the majority of studies focused validation of devices (23 out of 43 studies), including comparisons to polysomnography, actigraphy or other consumer targeted sleep tracking devices. At the time, too few studies evaluated the use of these devices for sleep interventions (n=5) to allow for a substantial review of the methods of these studies. The number of behavioral sleep medicine interventions using consumer sleep technology has substantially increased since our original review. Therefore, in this paper, we update and extend our previous paper by focusing specifically on the current landscape of how consumer sleep technologies are being used to provide behavioral sleep interventions. Our objective is to present a current state of the literature, identify gaps for research and practice and define opportunities for future research using consumer sleep technologies.

Methods

Overview

As in the previous review, we used the framework for conducting scoping reviews proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) and, consistent with the evolving standards for scoping reviews, initiated the review process by developing a protocol that defined our objectives and mapped out our methods (Peters et al., 2015). The steps of the review included the following: 1. Defining the research question, 2. Identifying relevant studies, 3 Study selection, 4. Charting the data and 5. Collating, summarizing, and reporting results. This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.(Shamseer et al., 2015)

Research question

The research question was: How are wearable and mobile consumer sleep technologies being used in behavior sleep interventions? We sought to identify relevant details including: how the devices were being used, the populations studied, theoretical orientations of the interventions (if present), and whether the intervention was delivered by technology alone or with a human coach.

Identifying relevant studies

An experienced information specialist (MB) developed the database search strategies using subject headings and title/abstract keywords related to sleep, wearable devices, smartphones, and mobile applications. We searched the following databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Science Citation Index Expanded, and Compendex (an engineering database). We ran our original searches in March 29, 2016 and updated the search in all databases on June 13, 2017, January and August 9, 2019. We developed the initial search strategy in MEDLINE using appropriate medical subject headings (MeSH) and title/abstract keywords and translated the MEDLINE search to the appropriate syntax for use in the other databases. Where possible, we limited search retrieval to articles published in English. Detailed search strategies, including all search terms, database platforms and dates of searches are available in Appendix 1. We exported records from each database into a master EndNote library and removed duplicates. (Thomson Reuters, 2016) We also reviewed the reference lists of included studies to attempt to locate additional relevant papers that may have been missed in the database searches.

Study selection

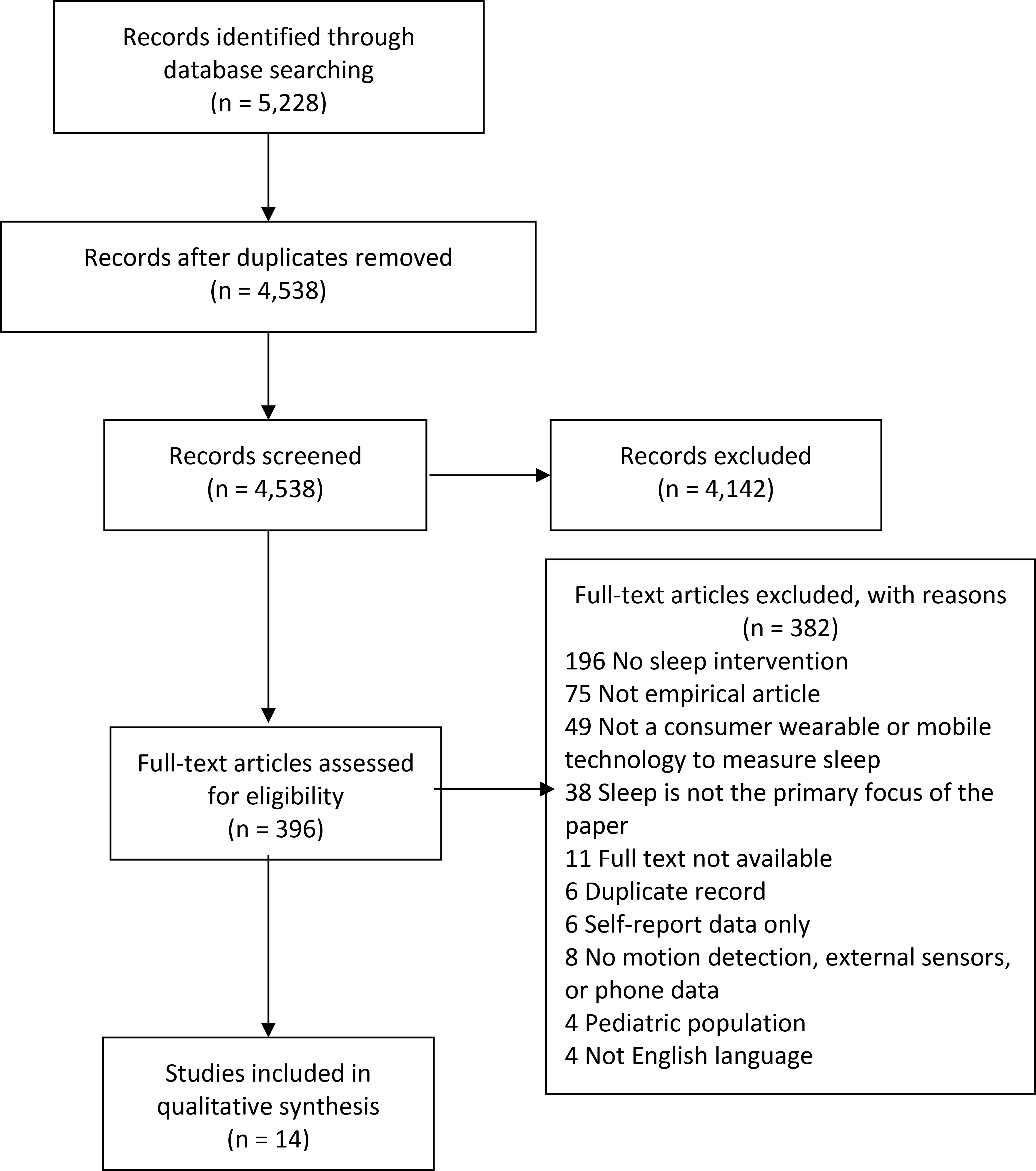

Our database searches retrieved a total of 5,228 records. After de-duplication, a total of 4,538 records remained. We uploaded the de-duplicated records to the Covidence systematic review platform to facilitate the title/abstract screening and full-text review processes (Veritas Health Innovation). Two reviewers independently screened the title and abstract of each record to determine whether full-text review was warranted. Inclusion criteria included: Studies that examined the use of consumer sleep technologies that included wearable devices or mobile applications to estimate sleep used to deliver a sleep-related intervention, were published in English, with adult participants. Exclusion criteria included: studies that used only self-reported sleep diaries or questionnaires. A total of 4,142 records were excluded on the basis of title/abstract screening, leaving 396 records eligible for full-text review. After retrieving the full-text articles identified in the title/abstract screening, two authors independently reviewed each paper and applied the agreed-upon inclusion criteria. We included 14 studies. We contacted the corresponding authors and attempted to complete any missing data (e.g. sample size, theoretical orientation). We resolved disagreements among reviewers at both the title/abstract screening and full-text review steps through arbitration by a third reviewer. See Figure 1 for a diagram detailing the flow of studies into the review.

Figure 1—

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Charting the data

The data extraction fields were determined through an iterative process. The study team identified the main areas of interest (study date, location, authors and title) as well as relevant study characteristics (type of technology, study aim, sample size, study outcome). After the team extracted a few test articles, additional fields were added for thematic analysis. Information recorded in the final extraction form included the following: Publication year, study location, type of device, population studied, number of participants, study objective, how the device was used, key findings, intervention description. The authors identified themes in the articles through discussion. All included studies were extracted by two individuals. Disagreements were resolved by discussion among the co-authors.

Results

Study characteristics

The details of the 14 studies included in our review are listed in Table 1. Study locations included 6 studies conducted in the US (Baron, Duffecy, Reid, et al., 2018; Berryhill et al., 2019; Crowley et al., 2016; Melton et al., 2016; Pulantara et al., 2018; Sano et al., 2015), four conducted in Israel (Baharav & Eyal, 2016; Baharav et al., 2018; Baharav & Niejadlik, 2018; Eyal & Baharav, 2017), One study conducted in Australia (Liang et al., 2016), Republic of Korea (Kang et al., 2017), Taiwan (Chu et al., 2018) and UK (Luik et al., 2018). The studies included a variety of populations: 7 studies included insomnia or poor sleep quality (Baharav & Eyal, 2016; Baharav et al., 2018; Berryhill et al., 2019; Eyal & Baharav, 2017; Kang et al., 2017; Luik et al., 2018; Pulantara et al., 2018), two were conducted in general samples of adults (Liang et al., 2016; Sano et al., 2015) two studies of employees (Baharav & Niejadlik, 2018; Crowley et al., 2016), two studies in undergraduate students (Chu et al., 2018; Melton et al., 2016), and one study of adults with short sleep duration (Baron, Duffecy, Reid, et al., 2018). The most commonly used consumer sleep technology was Fitbit, used in four studies (Baron, Duffecy, Reid, et al., 2018; Crowley et al., 2016; Kang et al., 2017; Pulantara et al., 2018). Four studies tested an app-based intervention that allowed participants to connect data to the application using several types of devices, no specific device used (Baharav et al., 2018; Baharav & Niejadlik, 2018; Luik et al., 2018; Sano et al., 2015). There were two studies that used a heartrate monitor (Baharav & Eyal, 2016; Eyal & Baharav, 2017) and two that used a Jawbone up device (Luik et al., 2018; Melton et al., 2016). One study used the Whoop device (Berryhill et al., 2019).

Table 1.

Articles by Theme

|

Insomnia (n=9)

| ||||||||

| Year | Author | Title | Location | Population | N | Device | How was it used | Intervention Description |

|

| ||||||||

| 2016 | Baharav et al. | Self-help for insomnia in the mobile area | Israel | Insomnia | 130 | HR monitor and smartphone app | Data were used along with self-report data in an automated digital insomnia treatment using a smartphone app that used wearable device data in the CBT-I protocol. | CBT-I |

| 2017 | Eyal et al. | Sleep deficits can be efficiently treated using e-therapy and a smartphone | Israel | Insomnia | 297 | HR monitor and smartphone app | Data were used to in an automated digital insomnia treatment using a smartphone app that used wearable device data in the CBT-I protocol. | CBT-I |

| 2017 | Kang et al. | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Using a Mobile Application Synchronizable With Wearable Devices for Insomnia Treatment: A Pilot Study | Korea | Insomnia | 19 | Fitbit | CBT-I was provided using a mobile application. The wearable device was synchronized with the application. Wearable device was integrated in the app as a digital sleep diary and sleep restriction recommendations were based on the mobile application and coach input. | CBT-I |

| 2017 | Luik et al. | Delivering Digital Cognitive-behavioral Therapy for Insomnia at Scale: Does Using a Wearable Device to Estimate Sleep Influence Therapy? | UK | Insomnia | 3551 | Fitbit device or Jawbone Up | Participants were able to link wearable device to an online CBT-I program. Wearable device was integrated to provide sleep diary data and used to adjust sleep restriction. | CBT-I |

| 2018 | Baharav et al. | Smartphones may serve as efficient sleep therapists | Israel | Insomnia | 250 | Multiple devices | Data were used along with self-report data in an automated digital insomnia treatment using a smartphone app. Wearable data were used to adjust sleep restriction. | CBT-I |

| 2018 | Baharav et al. | Impact of digital monitoring, assessment, and cognitive behavioral therapy on subjective sleep quality, workplace productivity and health related quality of life | Israel | Employees | 500 | Multiple devices | Data were used along with self-report data in an automated digital insomnia treatment using a smartphone app. Wearable data were used according to the CBT-I protocol. | CBT-I |

| 2018 | Chu et al. | A Mobile Sleep-Management Learning System for Improving Students’ Sleeping Habits by Integrating a Self-Regulated Learning Strategy: Randomized Controlled Trial | Taiwan | Undergrads | 18 | Not listed | Data were used to guide intervention delivered via smartphone application based intervention but no description was provided about how wearable data were used. | Self-regulated learning and CBT |

| 2018 | Pulantarna et al. | Development of a Just-in-time Adaptive mHealth Intervention for Insomnia: Usability Study | USA | Insomnia | 19 | Fitbit | This is an intervention development study. Data from the wearable device were integrated with a Just in Time Adaptive Intervention that includes information, 2-way communication, sensor integration, database and logical infrastructure. Wearable data were used to deliver a variety of sleep interventions to address problems such as nightmares or insomnia. | Brief behavioral intervention for insomnia (BBTI) |

| 2019 | Berryhill et al. | Cloud-based evaluation of wearable-derived sleep data in insomnia trials | USA | Insomnia | 8 | Whoop | Proof of concept (for feasibility) not used to deliver treatment. Treatment was delivered via face to face or telehealth platform. Wearable data was used as digital sleep diaries in a CBT-I program. | CBT-I |

|

Wellness (n=4) | ||||||||

| Year | Author | Title | Location | Population | N | Device | How was it used | Intervention description |

|

| ||||||||

| 2015 | Sano et al. | HealthAware: An Advice System for Stress, Sleep, Diet and Exercise | USA | Adults | 30 | Multiple | Application provided advices on sleep, diet or exercise based on wearable data. Wearable data were used to inform the automated advice on the app. | Not reported |

| 2016 | Crowley et al. | The Impact of Wearable Device Enabled Health Initiative on Physical Activity and Sleep | USA | Employees | 565 | Jawbone Up | Participants were provided with the wearable device as part of a wellness initiative to improve sleep and physical activity. Wearable device data were used for participant self-management, not specifically used in delivering intervention components. | Not reported |

| 2016 | Liang et al. | Sleep explorer: a visualization tool to make sense of correlations between personal sleep data and contextual factors | Australia | Adults | 12 | Fitbit | Application collected data on multiple contextual factors (e.g. caffeine use, alcohol, weight, stress) and graphically linked these factors to sleep. Wearable device data were used in graphs. | Not reported |

| 2016 | Melton et al. | Wearable devices to improve physical activity and sleep: A randomized controlled trial of college-aged African American women | USA | Students | 69 | Jawbone Up | Participants were provided with the wearable device, standardized training and weekly calls to encourage engagement. No information from wearable device data were used to deliver treatment beyond the tips provided device application itself. | Theory of planned behavior |

|

Other (n=1) | ||||||||

| Year | Author | Title | Location | Population | N | Device | How was it used | Intervention Description |

|

| ||||||||

| 2018 | Baron et al., | Development and user testing of a technology assisted intervention to extend sleep duration | USA | Short sleepers, Adults | 10 | Fitbit | Participants received a smartphone application with educational content and feedback from a wearable device. Weekly coaching was used to increase accountability and facilitate adherence to sleep related goals. Wearable device data were used by the coaches to provide feedback on progress toward sleep extension goals. | CBT, motivational interviewing |

Intervention description

Seven studies reported using the device to monitor sleep during cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) or brief behavioral therapy for insomnia (BBTI) programs (Baharav & Eyal, 2016; Baharav et al., 2018; Baharav & Niejadlik, 2018; Berryhill et al., 2019; Kang et al., 2017; Luik et al., 2018; Pulantara et al., 2018). These programs are the standardized treatments for insomnia that are recommended in the American Academy of Sleep Medicine Practice Guidelines (Edinger et al., 2020). Other models or frameworks that were mentioned were self-regulation theory (Bandura, 2005; Chu et al., 2018), theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Melton et al., 2016) and motivational interviewing (Baron, Duffecy, Reid, et al., 2018; Rollnick & Allison, 2004), which are theoretical models and techniques focused on engaging individuals in behavior change. Three studies did not report an intervention description used to guide their intervention (Crowley et al., 2016; Liang et al., 2016; Sano et al., 2015). For intervention delivery (computerized versus human), the 10 studies used a web or smartphone application to deliver the treatment program (Baharav et al., 2018; Baharav & Niejadlik, 2018; Chu et al., 2018; Crowley et al., 2016; Eyal & Baharav, 2017; Liang et al., 2016; Luik et al., 2018; Melton et al., 2016; Sano et al., 2015; Shin et al., 2017). Four studies used human delivered treatment (face to face, telehealth or telephone) in intervention delivery or coaching (Baron, Duffecy, Reid, et al., 2018; Berryhill et al., 2019; Crowley et al., 2016; Kang et al., 2017). One study provided the device without behavior change coaching (Melton et al., 2016). However, this study did include emails aimed at increasing use of the device.

Themes

We identified two main uses of consumer sleep technologies: 1. Insomnia interventions and 2. Wellness interventions.

Insomnia interventions

Half of the studies included in our review used consumer sleep tracking to provide objective sleep data for during a program of CBT-I (Baharav & Eyal, 2016; Baharav et al., 2018; Baharav & Niejadlik, 2018; Berryhill et al., 2019; Kang et al., 2017; Pulantara et al., 2018). Several studies used consumer sleep technology to inform treatment provided by a commercially available insomnia treatment program (My Sleep Rate or Sleepio, an online insomnia treatment program) and reported improvements with digital therapy (Baharav et al., 2018; Luik et al., 2018). In all of these studies, the wearable device was used as a digital sleep diary, to inform the patient, automated program or therapist about sleep in the past week, in order to adjust sleep restriction recommendations. One study compared outcomes among patients who participated in a group CBT-I program that had both human and digital elements (three in-person sessions, 2 telephone sessions and a mobile application) who were randomized to use a Fitbit or no Fitbit (Kang et al., 2017). Results indicated that the outcomes were similar between groups and participants found the device to be acceptable and feasible. Luik and colleagues (2018) evaluated the treatment outcomes for participants who connected their device (Fitbit or Jawbone) to the online treatment program Sleepio and also found that participants had similar outcomes regardless of their device use.

There were also studies demonstrating innovative approaches to insomnia using consumer sleep technology. One small pilot study used the Whoop device as part of a CBT-I program for newly discharged hospital inpatients (Berryhill et al., 2019). In this study, the wearable was used to engage a population that is traditionally difficult to engage in CBT-I due to poor health. Pulantara and colleagues (2018) presented a feasibility study of iREST, a an innovative Just in Time Adaptive Intervention that uses participant questionnaires and sleep diaries, two-way messaging between patient and clinician and Fitbit to adapt treatment to changing conditions (e.g. work hours, response to intervention) and provide a greater variety of treatment recommendations (e.g. insomnia, nightmares). These two studies were both in early/preliminary stages but demonstrate the beginning of new possibilities of consumer sleep technology in insomnia treatment. Taken together, the studies demonstrate that among this small group of studies, using consumer sleep technologies are possible but not enough data are available to determine their efficacy compared with standard insomnia treatments.

Wellness interventions

The other main group of studies looked at the use of consumer sleep technologies as part of wellness interventions or programs (Chu et al., 2018; Crowley et al., 2016; Kang et al., 2017; Liang et al., 2016; Melton et al., 2016; Sano et al., 2015). The devices were used in different ways and outcomes were variable. Crowley and colleagues reported on use of the Jawbone Up device in an employee wellness program at a pharmaceutical company (Crowley et al., 2016). The intervention included the device as well as education and incentives for participation. The intervention components were not based on wearable device data. Results demonstrated that although steps did not change with the program, the average sleep duration was higher at the end of the program compared with the beginning. Melton and colleagues randomized college students to receive a Jawbone Up device or no device and did not observe a change in sleep or steps with this intervention (Melton et al., 2016). Participants received emails to remind them to engage with the device but did not receive any sleep related intervention or feedback related to the device. Finally, two programs used the data from the wearable device combined with other user input on diet, stress etc. to help develop insight or provide customized advice (Liang et al., 2016; Sano et al., 2015). Data from these studies focused on the usability rather than the outcome. These studies demonstrate that the use of wearable devices in wellness interventions is relatively underdeveloped compared to CBT-I programs.

Other interventions

A study, completed by our lab, used wearable devices, combined with educational content and brief telephone coaching to increase sleep duration among individuals with short sleep duration (Baron, Duffecy, Reid, et al., 2018). This study was different from the other two categories, because the device was used in a non-insomnia sleep intervention. Results demonstrated this intervention was feasible and viewed favorably by participants, but the paper was focused on development and initial testing rather than outcomes.

Discussion

The goal of this systematic review was to determine how consumer sleep technologies are being used to deliver sleep-related interventions. Results of this study demonstrated that despite the growth in this area since our previous review, there are still relatively few interventions using consumer sleep technologies. Given the popularity of consumer sleep tracking devices, this review demonstrates the opportunity for behavioral sleep medicine to leverage consumer interest in these devices to advance the usability of our treatments. One of our questions was whether having objective data enhanced the delivery of behavioral sleep interventions. Data from studies that reported on use of consumer sleep technologies as part of commercial insomnia treatment programs demonstrated that devices are being used in effective treatments, due to the small number of participants (often a subset of a small randomized trial), it is unclear if the objective data is more effective at delivering the intervention. Only two studies randomized participants to a wearable device versus no device and found similar outcomes and treatment feasibility ratings in both groups, albeit in very small samples. One potential benefit of using wearable devices is reducing burden of completing sleep logs. These data seem to suggest that the automated nature of wearable devices did not interfere with treatment outcomes. For example, individuals who completed an online CBT-I program with and without a wearable device had similar outcomes of treatment (Luik et al., 2018). Therefore, using a wearable device may reduce barriers to treatment for patients who prefer automated tracking rather than keeping a sleep log.

It is important to point out that there was no evidence in our review that use of consumer sleep technology led to poorer outcomes in participants. Using technology may also have negative effects in some circumstances or for some patients. For example, use of a wearable device in a group weight management treatment led to lower long term weight loss outcomes compared to participants that did not receive a device (Polzien et al., 2007). We also previously reported a case series of patients who were overly focused on their devices (Baron et al., 2017), which we called “orthosomnia” and this fixation interefered with treatment. Using technology also has the potential to expose patients to blue light, if they are using their smartphone applications at night (Chang et al., 2015). These studies suggest there may be some unintended effects of tracking in some situations but overall none of the studies in our review negative impacts on sleep as a result of sleep tracking.

Another goal of this review was to identify new and innovative uses of consumer sleep technology in the delivery of behavioral interventions. This review identified novel applications of these devices including Just in Time Adaptive Interventions, new ways to deliver information to patients regarding their behavioral patterns/provide health advice and interventions to extend sleep. Our study of a sleep extension intervention was the only one in that area. It was not included in this review due to being published after our final search, but our sleep intervention that demonstrated efficacy at extending sleep and potential to reduce 24h ambulatory blood pressure (Baron et al., 2019). There are now multiple studies demonstrating potential benefits to sleep extension (Henst et al., 2019), therefore further research is needed to determine how consumer sleep technologies can be used in delivering these interventions.

As behavioral scientists, it is important to identify relevant theory behind interventions, in order to identify the effective components of change. All of the insomnia interventions in our review listed CBT-I as the foundation for their intervention techniques. This theory is well-described and numerous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of digital interventions using these techniques. However, among the wellness interventions, several studies in our review did not report a clear intervention description of how the device would be used. This result is consistent with other reviews of mobile sleep application and other health behavior apps (Grigsby-Toussaint et al., 2017). Zhao (2016) conducted a review of the effectiveness of health behavior change apps for a variety of health conditions (e.g. alcohol use, weight loss, physical activity). Results of this review pointed to – less than half of apps described an underlying theory (self-monitoring being the most common) and also identified aspects of the apps that predicted better outcomes (i.e., goal setting, self-monitoring, feedback as well as lower burden of self-monitoring and having health professional involvement).

Limitations of our review are that it is descriptive only, includes many preliminary studies that are mostly non-randomized and with small sample sizes. As a whole, this review could not determine if using devices is helpful to the delivery of behavioral sleep medicine interventions. Rather, this review provides a view of emerging behavioral sleep research of consumer sleep technologies area but cannot yet answer quantitative questions regarding their use. We also focused on wearable devices with sleep tracking and therefore did not review applications that assessed sleep using self-report only, contactless sensors or other devices (e.g. mattress sleep trackers). In another review, Shin and colleagues (2017) evaluated mobile phones for a variety of sleep disorders and included traditional therapies using mobile phone support (n=9) and app-based interventions (n=7). This review reported support for the capability and efficacy of mobile phones to deliver CBT-I and support for CPAP that was equal or enhanced the capability of traditional treatments (e.g. mobile support for CPAP vs. treatment as usual). Taken together, there is insufficient research on whether the objective data matters for outcomes, but there are a number of studies that support the use of mobile technology. Further research understanding the impacts of age, sex, education and other differences will also be helpful for determining which populations could enjoy and benefit from wearable devices in sleep interventions.

Conclusions and recommendations future research

Our review demonstrates that consumer sleep technologies with objective sleep tracking are being used both in traditional CBT-I interventions and in new intervention methodologies (combined face to face and digital CBT-I, just in time interventions). These new applications of consumer sleep technologies may provide opportunities for patients to develop new insights from their data, engage with providers in more flexible ways of providing interventions and also connect with difficult to reach populations that are more challenging to engage in traditional treatment models. The ability to use these devices in overall wellness interventions and for sleep extension is less developed and has demonstrated opportunities for improving sleep and potentially health outcomes. Overall, there is a tremendous opportunity to use wearables to engage patients in treatment, increase patient/therapist communication and reduce barriers to treatment. Further research is needed to progress beyond development/validation of behavioral sleep interventions using these devices and to test whether objective data enhances or detracts from behavioral sleep outcomes.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Shawn Steidinger for her assistance in updating our search strategy prior to this submission.

Appendix 1—Database Search Strategies

The searches of all databases were run on March 29, 2016, June 13, 2017 and August 9, 2019.

Ovid MEDLINE(R) In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1946 to Present>

(sleep* and (apple watch* or beddit or fitbit or fuelband* or fuel band* or garmin or jawbone or mondaine or moov or motorola or sleeprate or withings or xiaomi or zeo)).tw,kw. (19)

(sleep* and (wearable* or app or apps)).tw,kw. (164)

((consumer* adj25 sleep) and (track* or monitor*)).tw,kw. (13)

wearable*.tw,kw. (3263)

Mobile Applications/ (884)

(mobile application* or mobile app or mobile apps).tw,kw. (845)

exp Cell Phones/ (6805)

((cell* or smart or mobile) adj phone*).tw,kw. (6427)

(smartphone* or cellphone* or mobilephone* or smartwatch* or smart watch*).tw,kw. (2616)

(iphone* or ipod* or ipad* or android* or blackberr*).tw,kw. (2939)

ehealth.tw,kw. (1219)

e-health.tw,kw. (1453)

mobile health*.tw,kw. (1234)

mhealth.tw,kw. (808)

m-health.tw,kw. (165)

or/4–15 (20435)

exp Sleep/ (65519)

sleep*.tw,kw. (131450)

exp Sleep Wake Disorders/ (68276)

insomnia.tw,kw. (14214)

exp Sleep Apnea Syndromes/ (26730)

sleep apnea.tw,kw. (21112)

or/17–22 (165324)

16 and 23 (426)

or/1–3 (184)

24 or 25 (485)

exp animals/ not humans.sh. (4205567)

26 not 27 (471)

limit 28 to english language (451)

***************************

EMBASE (Embase.com)

(Includes Embase 1974-present; Embase Classic 1947–1973; Medline 1966-present)

Embase Session Results (29 Mar 2016)

| No. | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

| #24 | #23 AND [english]/lim | 932 |

| #23 | #21 NOT #22 | 952 |

| #22 | ‘animal’/exp OR ’nonhuman’/exp NOT ’human’/exp | 6085938 |

| #21 | #19 OR #20 | 984 |

| #20 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 | 352 |

| #19 | #12 AND #18 | 827 |

| #18 | #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 | 318234 |

| #17 | ‘sleep apnea’:ab,ti | 33336 |

| #16 | insomnia:ab,ti | 24743 |

| #15 | ‘sleep disorder’/exp | 191384 |

| #14 | sleep*:ab,ti | 197428 |

| #13 | ‘sleep’/exp | 187991 |

| #12 | #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 | 26644 |

| #11 | ehealth:ab,ti OR ’e-health’:ab,ti OR ’mobile health*’:ab,ti OR mhealth:ab,ti OR ’m-health’:ab,ti | 4337 |

| #10 | iphone*:ab,ti OR ipod*:ab,ti OR ipad*:ab,ti OR android*:ab,ti OR blackberr*:ab,ti | 4895 |

| #9 | smartphone*:ab,ti OR cellphone*:ab,ti OR mobilephone*:ab,ti OR smartwatch*:ab,ti OR ’smart watch*’:ab,ti | 3455 |

| #8 | ((cell* OR smart OR mobile) NEXT/1 phone*):ab,ti | 8432 |

| #7 | ‘mobile phone’/exp | 11197 |

| #6 | ‘mobile application*’:ab,ti OR ’mobile app’:ab,ti OR ’mobile apps’:ab,ti | 897 |

| #5 | ‘mobile application’/de | 1810 |

| #4 | wearable*:ab,ti | 3535 |

| #3 | consumer* NEAR/25 sleep AND (track* OR monitor*) | 26 |

| #2 | sleep*:ab,ti AND (wearable*:ab,ti OR app:ab,ti OR apps:ab,ti) | 259 |

| #1 | sleep* AND (‘apple watch*’ OR beddit OR fitbit OR fuelband* OR ’fuel band*’ OR garmin OR jawboneOR mondaine OR moov OR motorola OR sleeprate OR withings OR xiaomi OR zeo) | 84 |

PsycINFO (EBSCOhost)

S19 S4 OR S18

S18 S12 AND S17

S17 S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16

S16 TI “sleep apnea” OR AB “sleep apnea” OR TI “insomnia” OR AB “insomnia”

S15 DE “Sleep Disorders” OR DE “Hypersomnia” OR DE “Insomnia” OR DE “Kleine Levin Syndrome”

OR DE “Narcolepsy” OR DE “Parasomnias” OR DE “Sleepwalking” OR DE “Sleep Apnea”

S14 TI sleep* OR AB sleep*

S13 DE “Sleep” OR DE “Napping” OR DE “NREM Sleep” OR DE “REM Sleep”

S12 S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11

S11 TI ( ehealth or “e-health” or “mobile health*” or mhealth or “m-health” ) OR AB ( ehealth or “e-health” or “mobile health*” or mhealth or “m-health” )

S10 TI ( iphone* or ipod* or ipad* or android* or blackberr* ) OR AB ( iphone* or ipod* or ipad* or android* or blackberr* )

S9 TI ( smartphone* or cellphone* or mobilephone* or smartwatch* or “smart watch*” ) OR AB ( smartphone* or cellphone* or mobilephone* or smartwatch* or “smart watch*” )

S8 TI ( ((cell* or smart or mobile) N1 phone*) ) OR AB ( ((cell* or smart or mobile) N1 phone*) )

S7 TI ( “mobile application*” or “mobile app” or “mobile apps” ) OR AB ( “mobile application*” or “mobile app” or “mobile apps” )

S6 DE “Mobile Devices” OR DE “Cellular Phones”

S5 TI wearable* OR AB wearable*

S4 S1 OR S2 OR S3

S3 TI ( ((consumer* N25 sleep) and (track* or monitor*)) ) OR AB ( ((consumer* N25 sleep) and (track* or monitor*)) )

S2 TI ( (sleep* and (wearable* or app or apps)) ) OR AB ( (sleep* and (wearable* or app or apps)) )

S1 TI ( (sleep* and (“apple watch*” or beddit or fitbit or fuelband* or “fuel band*” or garmin or jawbone or mondaine or moov or motorola or sleeprate or withings or xiaomi or zeo)) ) OR AB ( (sleep* and (“apple watch*” or beddit or fitbit or fuelband* or “fuel band*” or garmin or jawbone or mondaine or moov or motorola or sleeprate or withings or xiaomi or zeo)) )

CINAHL with Full Text (EBSCOHost)

S21 S4 OR S20

S20 S13 AND S19

S19 S14 OR S15 OR S16 OR S17 OR S18

S18 TI “sleep apnea” OR AB “sleep apnea”

S17 TI insomnia OR AB insomnia

S16 (MH “Sleep Disorders”)

S15 TI sleep* OR AB sleep*

S14 (MH “Sleep+”)

S13 S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12

S12 TI ( ehealth or “e-health” or “mobile health*” or mhealth or “m-health” ) OR AB ( ehealth or “e-health” or “mobile health*” or mhealth or “m-health” )

S11 TI ( iphone* or ipod* or ipad* or android* or blackberr* ) OR AB ( iphone* or ipod* or ipad* or android* or blackberr* )

S10 TI ( smartphone* or cellphone* or mobilephone* or smartwatch* or “smart watch*” ) OR AB ( smartphone* or cellphone* or mobilephone* or smartwatch* or “smart watch*” )

S9 TI ( ((cell* or smart or mobile) N1 phone*) ) OR AB ( ((cell* or smart or mobile) N1 phone*) )

S8 TI ( “mobile application*” or “mobile app” or “mobile apps” ) OR AB ( “mobile application*” or “mobile app” or “mobile apps” )

S7 (MH “Mobile Applications”)

S6 (MH “Cellular Phone+”) OR (MH “Smartphone+”)

S5 TI wearable* OR AB wearable*

S4 S1 OR S2 OR S3

S3 TI ( ((consumer* N25 sleep) and (track* or monitor*)) ) OR AB ( ((consumer* N25 sleep) and (track* or monitor*)) )

S2 TI ( (sleep* and (wearable* or app or apps)) ) OR AB ( (sleep* and (wearable* or app or apps)) )

S1 TI ( (sleep* and (“apple watch*” or beddit or fitbit or fuelband* or “fuel band*” or garmin or jawbone or mondaine or moov or motorola or sleeprate or withings or xiaomi or zeo)) ) OR AB ( (sleep* and (“apple watch*” or beddit or fitbit or fuelband* or “fuel band*” or garmin or jawbone or mondaine or moov or motorola or sleeprate or withings or xiaomi or zeo)) )

Science Citation Index Expanded (Web of Science)

#11 #10 OR #9

#10 TS=((consumer* NEAR/25 sleep) and (track* or monitor*))

#9 #8 AND #1

#8 #7 OR #6 OR #5 OR #4 OR #3 OR #2

#7 TS=(ehealth or “e-health” or “mobile health*” or mhealth or “m-health”)

#6 TS=(iphone* or ipod* or ipad* or android* or blackberr*)

#5 TS=(smartphone* or cellphone* or mobilephone* or smartwatch* or “smart watch*”)

#4 TS=((cell* or smart or mobile) NEAR/1 phone*)

#3 TS=(wearable* or app or apps or “mobile application*” or “mobile app” or “mobile apps”)

#2 TS=(“apple watch*” or beddit or fitbit or fuelband* or “fuel band*” or garmin or jawbone or mondaine or moov or motorola or sleeprate or withings or xiaomi or zeo)

#1 TS=(sleep* or insomnia)

Compendex (Engineering Village-Elsevier)

( (((consumer* NEAR/25 $sleep) WN TI) OR ((consumer* NEAR/25 $sleep) WN AB)) AND (1884–2016 WN YR)) OR ( ((((((($ehealth OR {e-health} OR {mobile health*} OR $mhealth OR {m-health}) WN TI) OR (($ehealth OR {e-health} OR {mobile health*} OR $mhealth OR {m-health}) WN AB)) AND (1884–2016 WN YR)) OR ((((iphone* OR ipod* OR ipad* OR android* OR blackberr*) WN TI) OR ((iphone* OR ipod* OR ipad* OR android* OR blackberr*) WN AB)) AND (1884–2016 WN YR)) OR ((((smartphone* OR cellphone* OR mobilephone* OR smartwatch* OR {smart watch} OR {smart watches}) WN TI) OR ((smartphone* OR cellphone* OR mobilephone* OR smartwatch* OR {smart watch} OR {smart watches}) WN AB)) AND (1884–2016 WN YR)) OR (((({cellular phone} OR {cellular phones} OR {smart phone} OR {smart phones} OR {mobile phone} OR {mobile phones}) WN TI) OR (({cellular phone} OR {cellular phones} OR {smart phone} OR {smart phones} OR {mobile phone} OR {mobile phones}) WN AB)) AND (1884–2016 WN YR)) OR ((((wearable* OR $app OR $apps OR {mobile application} OR {mobile applications} OR {mobile app} OR {mobile apps}) WN TI) OR ((wearable* OR $app OR $apps OR {mobile application} OR {mobile applications} OR {mobile app} OR {mobile apps}) WN AB)) AND (1884–2016 WN YR)) OR ((((apple ONENEAR/1 watch*) OR beddit OR fitbit OR fuelband* OR (fuel ONENEAR/1 band*) OR garmin OR jawbone OR mondaine OR moov OR motorola OR sleeprate OR withings OR xiaomi OR zeo) WN AB OR ((apple ONENEAR/1 watch*) OR beddit OR fitbit OR fuelband* OR (fuel ONENEAR/1 band*) OR garmin OR jawbone OR mondaine OR moov OR motorola OR sleeprate OR withings OR xiaomi OR zeo) WN TI) AND (1884–2016 WN YR)))) AND ((((((({Human engineering--Sleep studies*} WN CV) OR ({Sleep research} WN CV)))) AND (1884–2016 WN YR)) OR ((((sleep*) WN AB) OR ((sleep*) WN TI)) AND (1884–2016 WN YR))))))

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data availability:

Data will be made available upon request.

References

- Adkins EC, DeYonker O, Duffecy J, Hooker SA, & Baron KG (2019). Predictors of Intervention Interest Among Individuals With Short Sleep Duration. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 15(8), 1143–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Analytics V (2018). Verto Index: Health and Fitness. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H, & O’Malley L (2005). Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Baharav A, & Eyal S (2016). Self-help for insomnia in the mobile era. J Sleep Res, [Google Scholar]

- Baharav A, Eyal S, & Niejadlik K (2018). Smartphones may serve as efficient sleep therapists. J Sleep Res, [Google Scholar]

- Baharav A, & Niejadlik K (2018). 0410 Impact of Digital Monitoring, Assessment, and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Subjective Sleep Quality, Workplace Productivity and Health Related Quality of Life. Sleep, 41, A156. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (2005). The primacy of self‐regulation in health promotion. Applied Psychology, 54(2), 245–254. [Google Scholar]

- Baron KG, Abbott S, Jao N, Manalo N, & Mullen R (2017). Orthosomnia: Are some patients taking the quantified self too far? Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 13(02), 351–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron KG, Duffecy J, Berendsen MA, Cheung Mason I, Lattie EG, & Manalo NC (2018). Feeling validated yet? A scoping review of the use of consumer-targeted wearable and mobile technology to measure and improve sleep. Sleep Med Rev, 40, 151–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron KG, Duffecy J, Reid K, Begale M, & Caccamo L (2018). Technology-Assisted Behavioral Intervention to Extend Sleep Duration: Development and Design of the Sleep Bunny Mobile App. JMIR Ment Health, 5(1), e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron KG, Duffecy J, Richardson D, Avery E, Rothschild S, & Lane J (2019). Technology Assisted Behavior Intervention to Extend Sleep among Adults with Short Sleep Duration and Prehypertension/Stage 1 Hypertension: A Randomized Pilot Feasibility Study. Sleep, 42, A408–A408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berryhill S, Patel SI, Provencio N, Combs D, Havens C, & Parthasarathy S (2019). Cloud-based evaluation of wearable-derived sleep data in insomnia trials. Sleep, [Google Scholar]

- Chang A-M, Aeschbach D, Duffy JF, & Czeisler CA (2015). Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(4), 1232–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu H-C, Liu Y-M, & Kuo F-R (2018). A mobile sleep-management learning system for improving students’ sleeping habits by integrating a self-regulated learning strategy: randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 6(10), e11557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley O, Pugliese L, & Kachnowski S (2016). The impact of wearable device enabled health initiative on physical activity and sleep. Cureus, 8(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edinger JD, Arnedt JT, Bertisch SM, Carney CE, Harrington JJ, Lichstein KL, Sateia MJ, Troxel WM, Zhou ES, & Kazmi U (2020). Behavioral and psychological treatments for chronic insomnia disorder in adults: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine systematic review, meta-analysis and GRADE assessment. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, jcsm. 8988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- eMarketer. (2018). US Adult Wearable Users and Penetration 2018–2022.

- Eyal S, & Baharav A (2017). Sleep deficits can be efficiently treated using e-therapy and a smartphone. Sleep, 40, A142–A143. [Google Scholar]

- Grigsby-Toussaint DS, Shin JC, Reeves DM, Beattie A, Auguste E, & Jean-Louis G (2017). Sleep apps and behavioral constructs: A content analysis. Preventive medicine reports, 6, 126–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henst RH, Pienaar PR, Roden LC, & Rae DE (2019). The effects of sleep extension on cardiometabolic risk factors: A systematic review. J Sleep Res, 28(6), e12865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S-G, Kang JM, Cho S-J, Ko K-P, Lee YJ, Lee H-J, Kim L, & Winkelman JW (2017). Cognitive behavioral therapy using a mobile application synchronizable with wearable devices for insomnia treatment: a pilot study. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 13(04), 633–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z, Ploderer B, L’iu W, Nagata Y, Bailey J, Kulik L, & Li Y (2016). Sleep explorer: a visualization tool to make sense of correlatioins between personal sleep data and contextual factors. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 20, 985–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Luik AI, Machado PF, & Espie CA (2018). Delivering digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia at scale: does using a wearable device to estimate sleep influence therapy? NPJ digital medicine, 1(1), 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melton BF, Buman MP, Vogel RL, Harris BS, & Bigham LE (2016). Wearable devices to improve physical activity and sleep: A randomized controlled trial of college-aged African American women. Journal of Black Studies, 47(6), 610–625. [Google Scholar]

- Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, & Soares CB (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc, 13(3), 141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polzien KM, Jakicic JM, Tate DF, & Otto AD (2007). The efficacy of a technology‐based system in a short‐term behavioral weight loss intervention. Obesity, 15(4), 825–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulantara IW, Parmanto B, & Germain A (2018). Development of a Just-in-Time adaptive mHealth intervention for insomnia: usability study. JMIR human factors, 5(2), e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, & Allison J (2004). Motivational interviewing. The essential handbook of treatment and prevention of alcohol problems, 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Sano A, Johns P, & Czerwinski M (2015). HealthAware: An advice system for stress, sleep, diet and exercise. 2015 International Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction (ACII), [Google Scholar]

- Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA, & Group P-P (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ, 350, g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin JC, Kim J, & Grigsby-Toussaint D (2017). Mobile phone interventions for sleep disorders and sleep quality: systematic review. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 5(9), e131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson Reuters. (2016). EndNote. In (Version X7)

- Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review software. In Veritas Health Innovation. https://www.covidence.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Freeman B, & Li M (2016). Can mobile phone apps influence people’s health behavior change? An evidence review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(11), e287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.