Abstract

The physical and functional properties of gelatin-based films enriched with organic extracts from Lepidium sativum seeds were studied. Gelatin was extracted from the skin of dogfish (Squalus acanthias) and the functional gelatin-based films were used to preserve cheese during chilled storage. Ethanol extract (LSE3) and gelatin-based film enriched with LSE3 at 20 μg/mL showed high antioxidant potential using various complementary methods. No significant difference was measured in the mechanical parameters of the enriched films in terms of thickness, tensile strength and elongation at break. LSE3 incorporation at the highest level slighltly decreased the film L∗ value from 90.30 ± 0.10 to 88.10 ± 0.12, while the b∗ value increased from 0.91 ± 0.07 to 8.89 ± 0.12. Wrapping the cheese with gelatin-based film enriched with 20 μg LSE3/mL reduced the syneresis by 40% and stabilized the color, peroxidation and bacteria growth as compared to the unwrapped sample after 6 days of storage. In addition, cheese wrapped with the active gelatin-based film showed the lowest changes in texture parameters. Overall results suggest the use of the enriched gelatin film as active packaging material to preserve cheese quality.

Keywords: Fish gelatin, Lepidium sativum, Antioxydant activities, Wrapping, Cheese preservation

Fish gelatin; Lepidium sativum; Antioxydant activities; Wrapping; Cheese preservation.

1. Introduction

Cheeses are popular dairy products, derived from milk after coagulation by lactic bacteria and presenting particular characteristics, such as the white color and acidity (Rinaldoni et al., 2014). However, the high moisture content increased their sensibility to microbial and molds developments, which caused sensory damage and led to reduce their shelf life (Afzaal et al., 2020). Therefore, many works studied the improvement of the shelf life of the milk-derived products, such as the use of modified atmosphere packaging (Khoshgozaran et al., 2012; Mastromatteo et al., 2015). The storage in an atmosphere containing high concentration of CO2 could stop the development of certain bacterial strains of dairy products. However, this method depends on the type of cheese, the used starter cultures and the storage conditions (Khoshgozaran et al., 2012). Vacuum packaging was also used to reduce spoilage caused by the aerobic bacteria and molds, but it is still not suitable for all types of cheese and could affect its sensory properties (Costa et al., 2016).

Food preservation needs to use various physical and chemical methods to reduce the microbial development (Medeiros et al., 2014). The packaging materials could be made from biological sources, such as biodegradable and sustainable biopolymers, as an alternative to classic synthetic materials that could affect the consumer's health (Costa et al., 2018; Jridi et al., 2020; Mirzapour-Kouhdasht and Moosavi-Nasab, 2020; Homayounpour et al., 2021). Biological materials used for food packaging showed an excellent barrier to water vapor and oxygen, which improved protection against microbiological spoilage (Etxabide et al., 2017). Fish gelatin, characterized by its film-forming capacity and transparency, could be used for packaging materials making to preserve fruits (Khan et al., 2014) and meat (Jridi et al., 2018). In addition, the enrichment of gelatin films with plant extracts serving as an antioxidant agent were reported in the literature review. Rangaraj et al. (2021) studied the effect of incorporation of date fruite waste extract as an antioxidant on the properties of gelatin films. Also, Riahi et al. (2021) performed the addition of grap fruit seed extract on gelatin films used for food packaging applications.

The combination between gelatin and other biopolymers, such as pectin or chitosan, was used to improve the film properties (Jridi et al., 2014a; Bermúdez-Oria et al., 2017). Bioactive compounds could be also incorporated into gelatin films to give more protection of food against oxidation and microbial spoilage. In fact, extracts rich in phenolics from tea, mango or orange peel, and turmeric were used to improve the films functional properties (Liu et al., 2015; Feng et al., 2016; Adilah et al., 2018; Jridi et al., 2019; Bojorges et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2020).

Lepidium sativum L., commonly known as garden cress, is an edible herb from the cruciferous family. This plant is usually used as leaf vegetable and herbal medicine in many countries. In addition, different organs of this plant showed interesting biological activities, such as antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, laxative and antidiarrheal activities (Manohar et al., 2009; Mehmood et al., 2011; Alqahtani et al., 2019; Rafińska et al., 2019; Getahun et al., 2020). To the best of our knowledge, no reports on the industrial application of this interesting medicinal plant. The use of edible coatings and antioxidant agents obtained from medicinal plants would be a natural and sustainable strategy to improve the quality of food products. Thus, the present work described a food application of marine gelatin enriched with L. sativum seeds extracts. The mechanical, color and optical properties of the dogfish skin gelatin films enriched with plant extracts were studied. Then, they were used as a packaging material to preserve cheese (Ricotta) during its refrigerated storage. The physicochemical changes of wrapped cheese during chilling storage were determined.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Extraction of gelatin from dogfish

Dogfish (Squalus acanthias) by-product generated after fish processing was obtained from Sfax market (Sfax, Tunisia). Gelatin was extracted from the fish skin as previously described by Salem et al. (2020). The obtained gelatin was dried using a spray dryer (y productBüchi, Flawil, Switzerland) with inlet temperature of 170 °C, outlet temperature of 88 °C and 12% pump aspiration. The gelatin used in this work contained 84.29% of proteins, 7.06% of moisture content and 3.25% of ash content as reported by Salem et al. (2020).

2.2. Preparation of L. sativum seeds extracts (LSE)

L. sativum seeds were purchased from a local market of (Gabes, Tunisia) at July 2020 and stored at 4 °C, 50% HR. The seeds were collected during the month of April from central eastern Tunisia. Six grams of seed powder were soaked in 100 ml of solvent: (i) 100% distilled water; (ii) distilled water/ethanol (50/50, v/v) or (iii) 100% ethanol. Each mixture was incubated for 24 h at 37 °C under continuous stirring. After that, the mixtures were centrifuged at 6000×g for 30 min (Gyrozen, yuseong-gu, South Korea) and the clear supernatants were recovered. Then, the extracts containing ethanol were evaporated using rotary evaporator (Büchi). After that, the different extracts of L. sativum seeds (LSE1: water extract, LSE2: water/ethanol (50/50, v/v) extract and LSE3: ethanol extract) were lyophilized (−50 °C, 0.001 mbar) and stored at −20 °C until use.

2.3. Film preparation and characterization

2.3.1. Film preparation

Film forming solutions were prepared by dissolving separately gelatin at 3% (m/v) concentration in distilled water at 60 °C. For the preparation of the active gelatin solutions, L. sativum extracts were dissolved in the gelatin solution at a concentration of 5, 10 or 20 μg/mL. Glycerol was used as a plasticizer to all solutions at a concentration of 15% (m/m biopolymer powder). The solutions were maintained under stirring for 30 min. Subsequently, a volume of 25 mL of each film forming solution was cast in polystyrene Petri dishes (13.5 cm diameter) and dried in a ventilated climatic chamber (Binder, Tuttlingen, Allemagne) at 25 °C and 50% relative humidity (RH) for 48 h. Eventually, 4 types of gelatin-based films were obtained: CF: control gelatin films without added LSE; F-LSE1, F-LSE2 and F-LSE3 represent gelatin-based films containing water, water/ethanol (50/50, v/v) and ethanol extracts at different concentrations, respectively.

2.3.2. Film characterization

2.3.2.1. Film thickness

Digital thickness gauge (PosiTector 6000, DeFelsko Corporation, USA) was used to measure the films thickness. Four measurements at different positions were taken from each film sample. The mean value was used in calculation and taken into account for mechanical properties.

2.3.2.2. Mechanical properties

Tensile strength (TS, MPa) and elongation at break (EAB, %) of film samples were determined using a texture analyzer (Stable Micro Systems, Godalming, UK) according to the standard method ISO 527-3 (equivalent to ASTM D882 method). Rectangular film samples (2.5 × 8 cm) were sized using a standardized precision cutter (Thwing-Albert JD, NJ, USA) in order to get tensile test piece with an accurate and parallel sides throughout the entire length. Film samples were then placed in the extension grips of the testing machine and stretched uniaxially with a cross-head speed of 50 mm/min until breaking. The maximum load and the final extension at break were determined from the corresponding stress-strain curves and used for calculation of TS and EAB. Measurements were carried out at room temperature and RH of 40 ± 5%. Five samples for each formulation were tested.

2.3.2.3. Color measurement

Color development was studied using a CIE colorimeter (Konica Minolta, Osaka, Japan) with D65 illuminant type and measurement geometry with di = 0°/de = 0°. Films color was expressed as L∗ (lightness/brightness), a∗ (redness/greenness) and b∗ (yellowness/blueness) values.

The difference (ΔE) and the saturation (C∗) in color of the incorporated gelatin films were determined referred to the control films (100% gelatin films) using Eqs. (1) and (2).

| (1) |

| (2) |

L∗, a∗ and b∗ are the color parameters of films incorporated with LSE3; L∗c, a∗c and b∗c are the color parameters of their control films (100% gelatin films).

2.3.2.4. Water vapor permeability (WVP)

WVP was determined following the method described by Sobral and Habitante (2001). Films were fixed onto the opening of cells (permeation area = 15.9 cm2) containing silica gel and the cells placed in desiccators with distilled water at 22 °C. It was then weighed at 1 h intervals over a period of 8 h. Three films were used for WVP testing. WVP of the film was calculated using Eq. (3).

| WVP (g m−1s−1Pa−1) = w × l × A−1 × t−1 × (P2– P1)−1 | (3) |

where w is the weight gain of the cup (g); l is the film thickness (m); A is the exposed area of film (m2); t is the time of gain (s); (P2– P1) is the vapor pressure difference across the film (Pa).

2.4. Evaluation of antioxidant activities

2.4.1. Ferric (Fe3+) reducing power

The ability of samples to reduce ferric iron was determined according to the method of Yildirim et al., 2001. A volume of 0.5 mL of each seed extract (from 100 to 400 μg/ml) or 10 mg of each film were mixed with 1.25 mL 0.2 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.6) and 1.25 mL of 1% potassium ferricyanide solution. This mixture was kept at 50 °C in water bath for 20 min. After cooling, 0.5 mL of 10% trichloro acetic acid was added and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min whenever necessary. The upper layer of solution (1.25 mL) was mixed with distilled water (1.25 mL) and a freshly prepared 0.1% ferric chloride solution (0.25 mL). The absorbance of the resulting solutions was measured at 700 nm after 10 min of incubation using a spectrophotometer (Jenway, Stone, UK). In the reducing power assay, the presence of antioxidants in the L. sativum seed extracts would result in the reducing of Fe3+ to Fe2+, which can be monitored by measuring the formation of Perl's Prussian blue (Fe4 [Fe(CN)6]3) at 700 nm. Three replicates were done for each sample.

2.4.2. β-carotene bleaching assay

The prevention of β-carotene from bleaching was determined according to the method of Koleva et al. (2002). First, a β-carotene/linoleic acid emulsion was prepared by dissolving 0.5 mg β-carotene, 25 μL linoleic acid and 200 μL tween 40 in 1 mL chloroform. The chloroform was then totally evaporated under vacuum using a rotatory evaporator at 50 °C. A volume of 100 mL of distilled water was added and the resulting emulsion was vigorously stirred. Thereafter, 2.5 mL β–carotene/linoleic acid emulsion were mixed with 0.5 mL of each seed extract (from 100 to 400 μg/ml) or 10 mg of each film. The absorbance was measured at 470 nm before and after incubation at 50 °C for 2 h and the β-carotene bleaching activity was determined using Eq. (4).

| β-carotene bleaching activity (%) = [1− (OD0 − ODt)/(OD0’− ODt’)] × 100 | (4) |

where OD0 and ODt are the absorbances of the test sample measured before and after incubation, respectively; and OD0'and ODt’ are the absorbances of the control measured before and after incubation, respectively. Tests were carried out in triplicate.

2.4.3. Radical scavenging activity on 1, 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH•)

The DPPH•-radical scavenging activity was determined as previously described by Bersuder et al. (1998). Firstly, 0.5 mL of each seed extract (from 100 to 400 μg/ml) or 10 mg of each film were allowed to react with 375 μL ethanol solution and 125 μL 0.02% DPPH• solution. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 60 min in the dark at room temperature (25 ± 2 °C) and the reduction of DPPH•-radical was measured at 517 nm. The test was carried out in triplicate and the DPPH•-radical scavenging activity was calculated using Eq. (5).

| DPPH•-radical scavenging activity (%) = [(ODC − ODS)/ODC] × 100 | (5) |

where ODC, and ODS represent the absorbances of the control and the sample reaction tubes, respectively. Tests were carried out in triplicate.

2.4.4. Ferrous (Fe2+) chelating activity

The iron chelating was measured as previously described by Decker and Welch (1990) with slight modifications. Firstly, 0.5 mL of each seed extract (from 100 to 400 μg/ml) or 10 mg of each film were immersed in 50 μL 2 mM FeCl2–4H2O and 450 μL distilled water. The mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 3 min. The reactions were initiated by the addition of 200 μL 5 mM 3-(2-Pyridyl)-5,6-diphenyl-1,2,4-triazine-p, p’-disulfonic acid monosodium salt hydrate (ferrozine solution). The mixtures were then vigorously shaken and left to stand at room temperature for 10 min. Control tube was prepared in the same way by replacing the film with water. Blank tubes were prepared in the same way with substituting the ferrozine solution by water. The absorbance of the solutions was measured at 562 nm and the inhibition percentage of ferrozine-Fe2+ complex formation was calculated using Eq. (6).

| Ferrous (Fe2+) chelating activity (%) = [(ODC + ODB + ODS)/ODC] × 100 | (6) |

Where ODC, ODB and ODS represent the absorbances of the control, blank and sample reactions tubes, respectively. Tests were carried out in triplicate.

2.5. Antibacterial activity

2.5.1. Microbial strains

The antibacterial activities were realized against four bacterial strains: Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922), Salmonella Typhimurium (ATCC, 19430), Bacillus cereus (ATCC 11778) and Micrococcus luteus (ATCC 4698).

2.5.2. Agar diffusion method

The antibacterial activities of the L. sativum seeds extracts was performed referring to the method described by Valgas et al. (2007). Microorganism's culture suspensions (200 μL), containing 106 colony forming units (CFU/mL) of bacteria cells, were spread on the surface of Luria-Bertani (LB) agar medium. Then, 60 μL LSE at a concentration of 2 mg/mL were loaded into wells (6 mm in diameter) already punched in the agar layer. The Petri dishes were kept at 4 °C for 1 h to favorise the extract diffusion and then incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. At the end of the incubation time, the diameter of growth inhibition zones (expressed in mm) present around the wells were measured.

2.5.3. Determination of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values, which represent the lowest extract concentration that completely inhibits the microorganisms growth, were determined by a micro-well dilution method of Wade et al. (2001). The inoculum of each bacterium was prepared and the suspensions were adjusted to 106 CFU/mL. All the extracts were dissolved in 100% ethanol and then dilutions series were prepared in a 96-well plate. Each well of the microplate included 40 μL of the growth medium, 10 μL of inoculum and 50 μL of the diluted sample extract. The plates were then covered with the sterile plate and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After that, 40 μL of 3-(4, 5-dimethyl-thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) at a final concentration 2 mg/mL freshly prepared in water was added to each well and incubated for 30 min. The change to red colour indicated that the bacteria were biologically active. The MIC was determined from the well where no change of MTT colour was observed. The MIC values were done in triplicate.

2.6. Cheese preparation and preservation

2.6.1. Cheese preparation

Traditional Tunisian cheese (Ricotta) was purchased from a local market (Sfax, Tunisia) in July 2020. Cheese was placed into food plastic boxes, covered with ice and transported to the laboratory. Then, the cheese was cut into 2 × 2 × 2 cm cubes and divided into three groups:

-

(i)

U: unwrapped cheese;

-

(ii)

CF: cheese wrapped with the control gelatin film;

-

(iii)

F-LSE3: cheese wrapped with gelatin-based film enriched with LSE3 at 20 μg/mL.

Samples were placed into sterile bags and stored under refrigeration at 4 °C for 6 days. The chemical composition, texture and microbiological analysis of cheese samples were realized during the storage period.

2.6.2. Evaluation of weight loss

The weight loss of the cheese samples at days 2, 4 and 6 were calculated by using Eq. (7).

| Weight loss (%) = (W0− Wt)/W0×100 | (7) |

Where W0 is the initial sample weight and Wt is the sample weight at 2, 4 and 6 days of refrigerated storage.

2.6.3. Evolution of water activity (aw) and pH

The pH and aw were measured by a pH meter (Metrohom, Metrohm, Switzerland) and a aw apparatus (Sprint TH-500, Novasina, Switzerland) during refrigerated storage.

2.6.4. Evolution of color property

The color of cheese samples was determined using a CIE colorimeter (Konica Minolta, Osaka, Japan). The instrument was standardized using standard white plates. An average value was determined by taking observations from three different cheese samples during refrigerated storage. Lightness (L∗) and redness (a∗) were recorded and the saturation (C∗) and the difference in color ΔE was calculated using the equations previously mentioned.

Were L∗, a∗ and b∗ are the color parameters of the wrapped cheese samples; L∗c, a∗c and b∗c are the color parameters of the untreated cheese pieces.

2.6.5. Microbial analysis

The microbiological analysis was determined according to the method described by Vanden Berghe and Vlietinck (1991). Cheese (1 g) from the different groups was homogenized with 9 mL 1% NaCl solution. Ten-fold serial dilutions of these homogenates were performed and used in bacterial enumeration. The total mesophilic bacteria count was determined using plate count agar (PCA) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) after incubation at 37 ± 1 °C for 24 h. The total psychrophilic bacteria of samples at days 1 and 6 were counted on PCA after incubation at 4 ± 1 °C for 7 days. Bacterial counts were presented as logarithms of colony-forming units per gram of cheese (log CFU/g).

2.6.6. Lipid peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation of samples throughout the storage period was evaluated according to the method reported by Buege and Aust (1978). The formation of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) were estimated on the basis of their reactivity with 2-thiobarbituric acid (TBA) under acidic conditions. Cheese sample (0.5 g) was homogenized with 525 μL TBS buffer (150 mM NaCl; 50 mM Tris-HCl; pH 7.4) and 375 μL TCA-BHT (20% TCA; 1% butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT)) to precipitate proteins, and then centrifuged (1000×g, 15 min, 4 °C). A volume of 400 μL of the supernatant was mixed with 80 μL 0.6 M HCl and 320 μL Tris-TBA (26 mM Tris; 120 mM TBA). The mixture was then incubated for 10 min at 90 °C. After cooling, the absorbance was recorded on a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (SAFAS UVmc, Monaco, France) at 530 nm. The TBARS values were calculated based on a standard curve of malondialdehyde (MDA) (expressed as mg MDA/kg cheese) with concentrations ranging from 0.2 to 1.2 mg of MDA.

2.6.7. Textural properties analyses (TPA)

The TPA parameters (strength, elasticity, chewiness and cohesiveness) were determined according to the method previously described by Jridi et al. (2015) using a Texture analyzer (Lloyd Instruments Ltd, West Sussex, UK). The samples were cut into small cubes of 2 × 2 cm in sides. TPA profile was determined as per the program: pre-test speed: 0.5 mm/s; test speed: 5 mm/s and trigger force: 0.05 N. The cheese samples were subjected to two cycle's compression to 30% of its original height using a cylindrical probe with 12 mm of diameter. The measurement was performed in triplicate.

2.7. Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS ver. 18.0, professional edition using ANOVA analysis. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05, using the Duncun test. All tests were carried out in triplicate.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Antioxidant potential of L. sativum extracts

3.1.1. DPPH•-radical scavenging activity

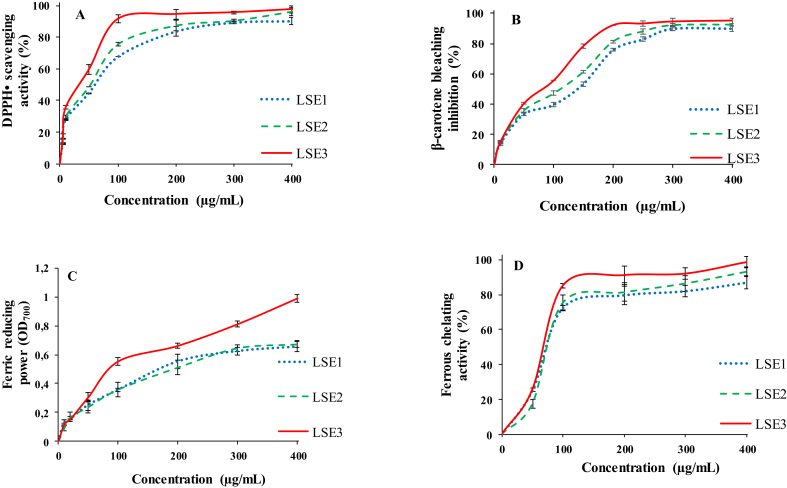

Free radical scavenging activity was thought to be one of the main antioxidant mechanisms. The results of DPPH•-radical scavenging of the different extracts were shown in Figure 1A. All curves shows that radical scavenging activity increased significantly with the increase of the extract concentration (p < 0.05). The ethanol extract (LSE3) showed the highest scavenging activity reaching 97.65% at 400 μg/mL. Many studies reported that ethanol extracts from L. sativum seeds or other plants show a higher antioxidant potential than that of aqueous extracts (Zia-Ul-Haq et al., 2012; Rafińska et al., 2019).

Figure 1.

Antioxidant activities of L. sativum seeds extracts. (A) DPPH• scavenging activity (%); (B) β-carotene bleaching inhibition (%); (C) Ferric reducing power (OD700); (D) Ferrous chelating activity (%). LSE1, LSE2 and LSE3 represent water, water/ethanol (50/50, v/v) and ethanol extracts, respectively.

3.1.2. β-Carotene bleaching inhibition

In the β-carotene/linoleic acid emulsion, the loss of yellow color of β-carotene was due to its reaction with conjugated diene hydroperoxides resulting from linoleic acid oxidation (Ksouda et al., 2019). Figure 1B shows that the extracts were capable to inhibit the β-carotene bleaching by scavenging linoleate-derived free radicals. The β-carotene bleaching inhibition activity increased significantly with increasing extract concentration (p < 0.05). The highest activity was also measured for LSE3 (94.75%), while the lowest value was measured for the LSE1 (87.25% at 400 μg/mL). Ait-Yahia et al. (2018) reported that water and ethanol extracts of L. sativum seeds showed higher β-carotene bleaching inhibition activity than that of n-butanol extract.

3.1.3. Ferric (Fe3+) reducing power

The reducing power measured the ability of compounds to give an electron to Fe3+, which was an important mechanism of phenolic antioxidant mechanism (Khantaphant and Benjakul, 2008). The ability of L. sativum seed extracts to reduce Fe3+ to Fe2+ was measured (Figure 1C). The obtained results showed a significant increase of absorbance in a dose dependent relationship (p < 0.05), which indicated an increase in reductive ability of the extracts. LSE3 showed an important ability to reduce ferric ion as compared to the other extracts. The significant reducing power of L. sativum extracts could be explained by the presence of certain secondary metabolites, which can act in the same way as reductones by donating electrons to free radicals to convert them into more stable products (Jayanthi and Lalitha, 2011).

3.1.4. Ferrous (Fe2+) chelating effect

The Fe2+ chelating effect of the different extracts were presented in Figure 1D. The obtained results also showed a significant increase of chelating effect in a dose dependent relationship (p < 0.05) and the LSE3 showed the highest activity reaching 96.54% at 400 μg/mL. In this context, Aydemir and Becerik (2011) reported that chelating effect of methanol extract of L. sativum seeds was higher than ethanol and water extracts with IC50 value of 137.19 μg/mL. Many studies reported that flavonoids not only have radical scavenging activities but also able to chelate transition metal ions, which may provide better protection against lipid peroxidation (Olennikov et al., 2014).

3.2. Antibacterial activities of L. sativum extracts

The antibacterial properties evaluated by growth inhibition zones (mm) and minimal inhibitory concentrations (μg/mL) were determined for the L. sativum extracts against Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium, Bacillus cereus and Micrococcus luteus. Table 1 shows the possibility of formation of inhibition zones resulting from exposure of bacteria to different extracts. The highest bacteriostatic activity was observed against B. cereus (MIC = 75 μg/mL) using LSE3 extract. Many works studied the antimicrobial activity of L. sativum extracts that showed a broad spectrum antimicrobial activity against Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria (El-Maati et al., 2016). The obtained results encourage the preparation of natural biomaterials for food products packaging containing LSE, which could potentially promote the shelf-life extension of wrapped food products.

Table 1.

Antibacterial activities of L. sativum seed extracts.

| Bacteria | LSE1 |

LSE2 |

LSE3 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IZ (mm) | MIC (μg/mL) | IZ (mm) | MIC (μg/mL) | IZ (mm) | MIC (μg/mL) | |

| Escherichia coli | 9.15 ± 0.56a | 250 | 7.89 ± 0.48b | 500 | 8.47 ± 0.12a | 500 |

| Salmonella typhimurium | 11.42 ± 0.18a | 125 | 9.75 ± 0.22b | 250 | 10.75 ± 0.35a | 125 |

| Bacillus cereus | 10.75 ± 0.16a | 125 | 8.72 ± 0.17b | 250 | 10.12 ± 0.21a | 75 |

| Micrococcus luteus | 7.05 ± 0.16a | 500 | 5.12 ± 0.16a | 500 | 6.57 ± 0.16a | 125 |

LSE1, LSE2 and LSE3 represent water, water/ethanol (50/50, v/v) and ethanol extracts, respectively. IZ: Inhibition zone diameter; MIC: minimal inhibitory concentration. a,b Different lower case letters in the same line indicate significant differences between the different films (p < 0.05).

3.3. Antioxidant capacity and physical properties of gelatin films

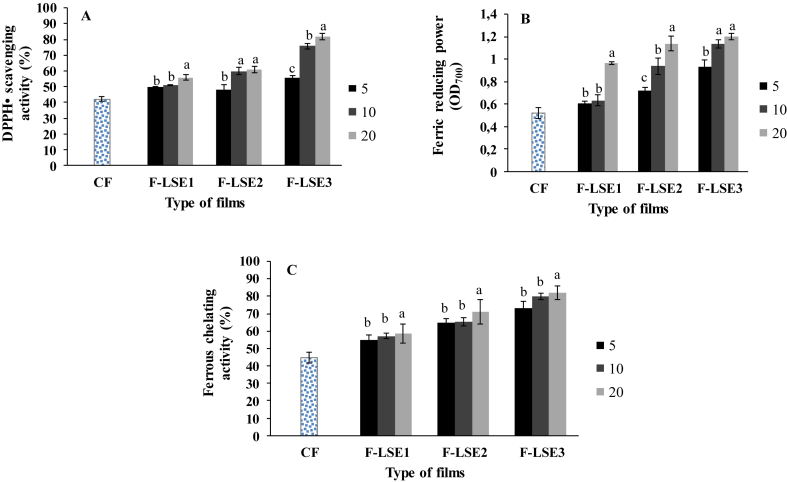

3.3.1. Antioxidant capacity

The antioxidant activities of gelatin-based films enriched with different LSE concentrations were also measured using three complementary tests (Figure 2). The obtained results showed that the gelatin-based film without added extract (control film) showed a relatively low antioxidant capacity. Interestingly, LSE incorporation into the dogfish gelatin films significantly increased (p < 0.05) their antioxidant potential in a dose-dependent manner. The gelatin film enriched with 20 μg LSE3/mL gelatin solution showed the highest DPPH•-radical scavenging activity (82%), ferric (Fe3+) reducing power (1.2) and ferrous (Fe2+) chelating activity (82%). These results could affirm the higher antioxidant activities measured for LSE3 (Figure 1). The antioxidant activities of films confirm the obtained results for L. sativum extracts and explained the highest antioxidant activity obtained for the film enriched with LSE3. From the other hand, L. sativum extracts contained different active compounds such as kaempferol di-hexoside rhamnose and quercetin di-hexoside rhamnose known to possess important antioxidant potential (Ait-Yahia et al., 2018). The antioxidant capacity of gelatin-based films enriched with bioactive compounds was reported in the literature. Films based on (i) silver carp skin gelatin enriched with green tea extract (Wu et al., 2013); (ii) tuna-skin gelatin enriched with methanol extracts of brown algae (Haddar et al., 2012) and (iii) gelatin supplemented with curcuma ethanol extract (Bitencourt et al., 2014) showed enhanced antioxidant capacities. In fact, the phenolic compounds of plant extracts conferred antioxidant capacity to the gelatin-based films (Li et al., 2014).

Figure 2.

Antioxidant activities of gelatin-based films enriched with different concentrations (5, 10 and 20 μg/ml) of L. sativum extracts. (A) DPPH• scavenging activity (%); (B) Ferric reducing power (OD700); (C) Ferrous chelating activity (%). CF: control films; F-LSE1, F-LSE2 and F-LSE3 represent gelatin-based films containing water, water/ethanol (50/50, v/v) and ethanol extracts, respectively. a, b, c Different letter indices indicate significant differences for the gelatin-based films within different extract concentrations (p < 0.05).

3.3.2. Mechanical properties and water vapor permeability (WVP)

Mechanical properties were among the important characteristics of a packaging film that must provide the integrity of the product from external stresses (Hosseini et al., 2016). Table 2 shows the results of thickness, tensile strength (TS), and elongation at break (EAB) of gelatin-based films enriched with different LSE concentrations. No significant difference was recorded in the mechanical parameters of the enriched films (p > 0.05). However, Li et al. (2014) reported that incorporation of natural antioxidants into film caused a significant decrease of its TS. These authors suggested that polyphenolic compounds could form covalent and hydrogen bonds with amino and hydroxyl groups of polypeptide in gelatin, which would weaken the protein–protein interactions that stabilize the protein network. On the other hand, it was reported that incorporation of some plant extracts increased the EAB values of gelatin-based films, which was explained by specific interactions between poly-peptides and phenolic compounds. In fact, covalent cross-links could be established that may lead to the formation of more cohesive and flexible matrices (Bitencourt et al., 2014; Bonilla and Sobral, 2016; Jridi et al., 2019).

Table 2.

Mechanical properties of gelatin-based films enriched with different concentrations of L. sativum extracts.

| Films | Extract enrichment (μg/mL) | Thickness (μm) | TS (MPa) | EAB (%) | WVP (×10−11 g m−1 s−1 Pa−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CF | 0 | 60.56 ± 1.25a | 4.26 ± 0.85a | 204.53 ± 0.43a | 4.72 ± 0.88a |

| F-LSE1 | 5 | 60.25 ± 1.05a | 4.12 ± 1.25a | 203.12 ± 1.42a | 4.22 ± 0.85a |

| 10 | 60.57 ± 0.86a | 4.22 ± 1.35a | 207.14 ± 1.13a | 4.12 ± 0.96a | |

| 20 | 61.02 ± 1.42a | 4.27 ± 1.04a | 205.75 ± 1.18a | 3.98 ± 0.36a | |

| F-LSE2 | 5 | 60.63 ± 1.15a | 4.29 ± 1.42a | 202.74 ± 1.30a | 3.92 ± 0.75a |

| 10 | 61.23 ± 1.45a | 4.25 ± 1.12a | 204.72 ± 1.12a | 3.78 ± 0.45a | |

| 20 | 61.29 ± 0.75a | 4.78 ± 0.75a | 206.55 ± 1.96a | 3.57 ± 0.72a | |

| F-LSE3 | 5 | 60.13 ± 0.48a | 4.43 ± 0.72a | 208.12 ± 1.75a | 3.46 ± 0.86a |

| 10 | 59.97 ± 1.28a | 4.24 ± 1.11a | 207.48 ± 1.04a | 3.33 ± 0.75a | |

| 20 | 60.47 ± 1.48a | 4.38 ± 1.21a | 207.22 ± 1.23a | 3.23 ± 0.53a |

CF: control gelatin films without added LSE; F-LSE1, F-LSE2 and F-LSE3 represent gelatin-based films containing water, water/ethanol (50/50, v/v) and ethanol extracts, respectively. Control represent gelatin-based film without added extract.

The water vapor permeability (WVP) gave information about the expiration date of packaging materials for food and medicine. Thus, films made for food packaging must stop as much as possible the moisture transfer into food products from the surrounding atmosphere. The highest WVP value was obtained for CF film (4.72 × 10−11 g m−1 s−1 Pa−1). The addition of LSE extract lead to the decrease of WVP and the lowest values were obtained for F-LSE3 (3.46, 3.33 and 3.23 (×10−11 g m−1 s−1 Pa−1) for films contained 5, 10 and 20 μg/mL of LSE3 extract, respectively. These results were in accordance with those reported by Wu et al. (2013). Furthermore, the phenolic compounds of the extract and the gelatin molecules could form covalent bonds leading to a decrease in the WVP values of the enriched films (Lee et al., 2016). From the other hand, Nie et al. (2015) illustrated that the dense network can reduce the free volume of the film matrix, which reduced the diffusion rate of water molecules.

3.3.3. Color measurement

The edible films color was measured since it was related to the overall appearance of food products and consumer acceptance (Kakaei and Shahbazi, 2016). In addition, in this case the prepared edible films should also showed the cheese color. The color parameters (L∗, a∗, b∗, ΔE, chroma) of the prepared gelatin-based fims were measured and presented in Table 3. The added extracts of L. sativum decreased the L∗ and a∗ values, on the other hand they increased the b∗ values. These changes were more marked with LSE3. Indeed, the incorporation of LSE3 at 20 μg/mL reduced the film lightness value from 90.30 ± 0.10 to 88.10 ± 0.12 and the a∗ value from 0.92 ± 0.05 to −2.75 ± 0.14. In addition, LSE3 addition resulted in an increase of the film yellowness value from 0.91 ± 0.07 to 8.89 ± 0.12, which indicated that extract incorporation gave them a slight yellowish tone. The color saturation (chroma), which refers to the dominance of hue in the color, of the gelatin-based films enriched with extracts showed values less than 10 (Table 3). The obtained results were in accordance with those reported by Jridi et al. (2019) and Adilah et al. (2018), who noted an increase of yellowness after plant extract incorporation into gelatin-based films. In fact, the observed changes of film's color might be due to the natural colored pigments present in the L. sativum extract. Table 3 also shows that the total color difference (ΔE) increased with extract concentration and the highest value (9.05 ± 0.53) was measured for the gelatin-based film enriched with LSE3 at 20 μg/mL. The ΔE measurement quantified the difference between the displayed color and the original color standard of the input content. Lower ΔE figures indicated greater accuracy, while high ΔE levels represented a significant mismatch. Thus, the measured ΔE values were lower than 10, which showed that the color of gelatin-based films enriched with L. sativum extracts was perceptible at a glance (Kocaoğlu and Olguntürk, 2019).

Table 3.

Color properties of gelatin-based films enriched with different concentrations of L. sativum extracts.

| Films | Extract enrichment (μg/mL) | L∗ | a∗ | b∗ | ΔE | Chroma |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CF | 0 | 90.30 ± 0.10a | 0.92 ± 0.05a | 0.91 ± 0.07d | - | - |

| F-LSE1 | 5 | 90.12 ± 0.19a | 0.75 ± 0.12a | 1.45 ± 0.15c | 0.59 ± 0.07e | 0.57 ± 0.03e |

| 10 | 90.07 ± 0.14a | 0.39 ± 0.10a | 2.15 ± 0.12c | 1.37 ± 0.13d | 1.35 ± 0.11d | |

| 20 | 90.01 ± 0.15a | 0.12 ± 0.04a | 2.89 ± 0.06c | 2.16 ± 0.15c | 2.14 ± 0.42c | |

| F-LSE2 | 5 | 89.45 ± 0.17b | −0.13 ± 0.02b | 4.15 ± 0.16b | 3.51 ± 0.42c | 3.41 ± 0.13c |

| 10 | 89.13 ± 0.05b | −0.45 ± 0.07b | 4.98 ± 0.11b | 4.45 ± 0.75b | 4.29 ± 0.77b | |

| 20 | 89.01 ± 0.04b | −0.89 ± 0.12b | 5.78 ± 0.10a | 5.35 ± 0.14b | 5.20 ± 0.56b | |

| F-LSE3 | 5 | 88.78 ± 0.48b | −1.48 ± 0.15c | 6.75 ± 0.23a | 6.49 ± 0.22b | 6.31 ± 0.86a |

| 10 | 88.26 ± 0.10b | −1.99 ± 0.23c | 7.15 ± 0.21a | 7.18 ± 0.75a | 6.89 ± 0.53a | |

| 20 | 88.10 ± 0.12c | −2.75 ± 0.14c | 8.89 ± 0.12a | 9.05 ± 0.53a | 8.78 ± 0.86a |

CF: control gelatin films without added LSE; F-LSE1, F-LSE2 and F-LSE3 represent gelatin-based films containing water, water/ethanol (50/50, v/v) and ethanol extracts, respectively. Control represent gelatin-based film without added extract. a,b,c,d,e Different lower case letters in the same column indicate significant differences between the different films (p < 0.05).

3.4. Cheese preservation

The analyzed cheese samples were the unwrapped cheese, cheese wrapped with gelatin-based film and cheese wrapped with gelatin-based film containing LSE3 at 20 μg/mL, which were stored at 4 °C during 6 days. The LSE3 was chosen to be added to the gelatin film, since it showed the highest antioxidant and antibacterial activities.

3.4.1. Evolution of physico-chemical parameters of cheeses during storage

Table 4 shows the evolution of water activity (aw), weight loss (%) and pH and of cheese samples during the storage period. The obtained results showed that the studied cheese offered excellent conditions for survival and growth of bacteria, because of high aw (0.89–0.92), pH above 5.78 ± 0.17, in addition to the low salt content and absence of preservatives. In fact, the unwrapped cheese (control) showed a slight and not significant (p > 0.05) decrease in values of aw during storage (Table 4). In addition, the wrapped cheese samples showed stable aw values over 6 days of storage, which were slighltly higher than those of the control sample.

Table 4.

Changes in pH, water activity (aw) and weight loss (%) of the different trials of cheese studied during refrigerated storage.

| Storage time (day) | U | CF | F-LSE3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aw | 1 | 0.913 ± 0.27a | - | - |

| 2 | 0.907 ± 0.17aB | 0.918 ± 0.07aA | 0.920 ± 0.16aA | |

| 4 | 0.902 ± 0.12aB | 0.920 ± 0.13aA | 0.922 ± 0.15aA | |

| 6 | 0.890 ± 0.13aB | 0.923 ± 0.04aA | 0.923 ± 0.07aA | |

| Weight loss (%) | 2 | 8.95 ± 0.52cA | 4.59 ± 0.44cB | 2.36 ± 0.54cC |

| 4 | 16.91 ± 0.54bA | 11.08 ± 1.48bB | 9.23 ± 0.91bB | |

| 6 | 24.98 ± 0.54aA | 17.68 ± 1.10aB | 15.12 ± 0.77aB | |

| pH | 1 | 6.59 ± 0.01a | - | - |

| 2 | 6.46 ± 0.05aA | 6.39 ± 0.01aA | 6.39 ± 0.02aA | |

| 4 | 6.12 ± 0.08aA | 6.25 ± 0.18aA | 6.26 ± 0.18aA | |

| 6 | 5.78 ± 0.17bB | 6.03 ± 0.37bA | 6.24 ± 0.22aA |

U: unwrapped cheese; CF: cheese wrapped with the control gelatin-based film; F-LSE3: cheese wrapped with gelatin-based film enriched with LSE3 at 20 μg/mL. a,b,c Different lower case letters in the same column indicate significant differences for the same sample within different days of storage (p < 0.05).A,B,C Different capital letters indicate significant differences between samples in the same storage day (p < 0.05).

Table 4 shows that syneresis, evaluated by weight loss measurement, significantly increased (p < 0.05) during storage for the three trials of cheese. Syneresis was more marked for unwrapped cheese, which was in accordance with the aw results. However, it was reduced by wrapping with the gelatin film and especially the one enriched with LSE3 at 20 μg/mL. The weight loss was related to the water permeability of the packaging films. In fact, Ksouda et al. (2019) reported similar results, where coatings based on natural polymers helped to reduce the water loss, which ensured good cheese quality. Jridi et al. (2020), who performed cheese wrapping using gelatin film containing pectin, suggested that the decrease of weight loss may be due to the reduction of film wettability controlled by the attraction forces between the casein network and the gelatin-based film.

The initial pH of all samples were near to neutrality and then gradually decreased. Indeed, this decrease was more marked for the unwrapped sample reaching 5.78 at day 6. Interestingly, gelatin-based film enriched with LSE3 at 20 μg/mL reduced the cheese acidification and maintained the pH approximately at its initial value. The obtained results were similar to those reported by Ksouda et al. (2019). The pH decrease could be due to the lactose fermentation caused by lactic bacteria leading to the cheese acidification. The antibacterial activity of the gelatin-based film enriched with LSE3 at 20 μg/mL could slow down the development of lactic bacteria, and consequently reduced the cheese acidification.

3.4.2. Textural and color properties of cheeses during storage

Evolution of texture properties, in terms of strength, cohesiveness, springiness and chewiness, of cheeses during storage was shown in Table 5. After 6 days of storage at 4 °C, the unwrapped cheese sample presented significantly (p < 0.05) higher strength value than those of wrapped cheeses. Unwrapped cheese also showed significant decrease (p < 0.05) in springiness, chewiness and cohesiveness as compared to wrapped cheeses. Interestingly, cheese wrapped with gelatin-based film enriched with LSE3 at 20 μg/mL showed the lowest changes in texture parameters. The obtained results were similar to those reported by Costa et al. (2016). In fact, the intense acidification and syneresis observed in unwrapped cheese induced alterations in its strength, springiness and chewiness at the end of the storage period, which led to the brittle texture observed for this cheese. The water vapor barrier property of gelatin-based films enriched with LSE3 at 20 μg/mL could improve cheese texture.

Table 5.

Changes in texture profile analysis of the different trials of cheese studied during refrigerated storage.

| Storage time (day) | U | CF | F-LSE3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strength (N) | 1 | 1.40 ± 0.25bA | 1.49 ± 0.27bA | 1.42 ± 0.29bA |

| 6 | 2.40 ± 0.35aA | 2.11 ± 0.45aB | 1.85 ± 0.14aC | |

| Cohesiveness | 1 | 0.26 ± 0.02aA | 0.32 ± 0.07aA | 0.27 ± 0.05aA |

| 6 | 0.18 ± 0.01bB | 0.21 ± 0.06aA | 0.25 ± 0.01aA | |

| Springiness (%) | 1 | 27.5 ± 0.24aA | 30.2 ± 0.37aA | 27.2 ± 0.15aA |

| 6 | 8.8 ± 0.02bB | 10.5 ± 0.13bB | 18.9 ± 0.14bA | |

| Chewiness (N × mm) | 1 | 1.35 ± 0.15aA | 1.78 ± 0.21aA | 1.35 ± 0.48aA |

| 6 | 0.45 ± 0.04bB | 1.11 ± 0.14bA | 1.20 ± 0.12bA |

U: unwrapped cheese; CF: cheese wrapped with the control gelatin-based film; F-LSE3: cheese wrapped with gelatin-based film enriched with LSE3 at 20 μg/mL. a,b Different lower case letters in the same column indicate significant differences for the same sample within different days of storage (p < 0.05).A,B,C Different capital letters indicate significant differences between samples in the same storage day (p < 0.05).

Color is an important parameter in food quality control that influences consumers’ demand. Table 6 shows the changes in color parameters of different cheese samples wrapped or not with gelatin films. A significant (p < 0.05) decrease was measured in L∗ value of unwrapped cheese at 6 days of storage. Interestingly, cheese wrapping by gelatin films allowed the stabilisation of its lightness at the end of the storage period. The decrease in L∗ values could be the result of microbial growth on the cheese surface (Bermúdez-Aguirre and Barbosa-Cánovas, 2010). In addition, a∗ and b∗ values of unwrapped cheese increased significantly (p < 0.05), indicating the color change from white to yellow after 6 days of storage. The a∗ and b∗ values of cheese samples wrapped by gelatin-based films remained lower than those of unwrapped samples at the end of the experimental period. The obtained results were in agreement with previous studies dealing with cheese coating (Ksouda et al., 2019) and sliced cheddar cheese wrapping (De Moraes et al., 2020). Interestingly, cheese wrapped with gelatin film enriched with LSE3 at 20 μg/mL showed the lowest changes in color parameters, allowing to preserve the initial cheese color.

Table 6.

Changes in color parameters of the different trials of cheese studied during refrigerated storage.

| Day 1 |

Day 2 |

Day 4 |

Day 6 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U | CF | F-LSE3 | U | CF | F-LSE3 | U | CF | F-LSE3 | U | CF | F-LSE3 | |

| L∗ | 88.62 ± 0.52aB | 88.99 ± 0.48aA | 90.12 ± 0.57aA | 88.01 ± 0.48aA | 88.15 ± 0.18aA | 89.45 ± 1.25aA | 86.36 ± 0.42bB | 87.85 ± 2.33aA | 89.12 ± 0.50aA | 85.13 ± 0.97bB | 87.94 ± 2.41bB | 89.79 ± 0.46aA |

| a∗ | −2.71 ± 0.07aA | −2.42 ± 0.15aA | −2.89 ± 0.56aA | −2.01 ± 0.14aA | −2.15 ± 0.42aA | −2.75 ± 0.08aA | −1.43 ± 0.07bA | −1.99 ± 0.21aA | −2.45 ± 0.07aB | −1.07 ± 0.05bA | −1.87 ± 0.19bA | −1.99 ± 0.25bB |

| b∗ | 9.75 ± 0.07bA | 9.57 ± 0.82bA | 9.48 ± 0.12bA | 10.78 ± 0.58bA | 10.25 ± 0.75aA | 9.67 ± 0.86aB | 11.59 ± 0.67aA | 10.86 ± 0.01aA | 10.08 ± 0.69aB | 12.98 ± 1.04aA | 11.05 ± 0.03aA | 10.45 ± 0.89aB |

| C∗ | - | 7.15 ± 0.11bA | 6.59 ± 1.23aA | - | 8.10 ± 0.45bA | 6.92 ± 0.55bB | - | 8.87 ± 0.74aA | 7.63 ± 0.73aB | - | 2.08 ± 0.48aA | 2.69 ± 0.13aA |

| ΔE | - | 0.59 ± 0.02bB | 1.53 ± 0.16aA | - | 0.56 ± 0.04bB | 1.96 ± 0.19aA | - | 1.75 ± 0.16aB | 3.30 ± 0.23aA | - | 3.50 ± 0.17aB | 5.38 ± 0.77aA |

U: unwrapped cheese; CF: cheese wrapped with the control gelatin-based film; F-LSE3: cheese wrapped with gelatin-based film enriched with LSE3 at 20 μg/mL. a,b Different lower case letters in the same column indicate significant differences for the same sample within different days of storage (p < 0.05). A,B Different capital letters indicate significant differences between samples in the same storage day (p < 0.05).

3.4.3. Microbiological analysis

The total viable count of bacteria was an important microbiology indicator for the sanitary cheese quality. Thus, enumeration of mesophilic and psychrophilic flora in cheese samples was assessed during refrigerated storage and the results were shown in Table 7. During the experimental period, the mesophilic and psychrophilic bacteria of unwrapped cheese increased significantly (p < 0.05) after 6 days of storage. However, the wrapped cheese samples showed lower mesophilic and psychrophilic bacteria counts than those of the unwrapped cheese. Likewise, Ramos et al. (2016) reported that cheese wrapping using biodegradable edible films reduced bacteria growth and bring several advantages as compared to conventional coatings. It seems that gelatin-based films reduced the microorganisms growth due to its barrier property against oxygen diffusion. Interesting fact, the incorporation of LSE3 in gelatin films significantly (p < 0.05) restricted the bacteria growth as compared to other cheese samples. These findings were in accordance with the physico-chemical properties measured for wrapped cheese using F-LSE3.

Table 7.

Evolution of mesophilic and psychrophilic bacteria (log CFU/g cheese) during refrigerated storage.

| Storage time (day) | U | CF | F-LSE3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesophilic bacteria | 1 | 2.34 ± 0.15bA | 2.24 ± 0.01bA | 2.05 ± 0.02bB |

| 6 | 4.49 ± 0.17aA | 3.96 ± 0.14aA | 2.59 ± 0.11aA | |

| Psychrophilic bacteria | 1 | 1.02 ± 0.05bA | 0.95 ± 0.01bA | 0.90 ± 0.02bB |

| 6 | 2.27 ± 0.05aA | 1.86 ± 0.07aB | 1.29 ± 0.02aB |

U: unwrapped cheese; CF: cheese wrapped with the control gelatin-based film; F-LSE3: cheese wrapped with gelatin-based film enriched with LSE3 at 20 μg/mL. a,b Different lower case letters in the same column indicate significant differences for the same sample within different days of storage (p < 0.05). A,B Different capital letters indicate significant differences between samples in the same storage day (p < 0.05).

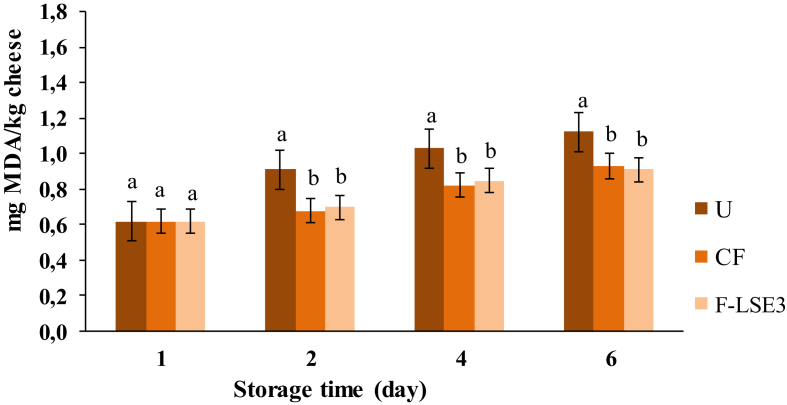

3.4.4. Lipid peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation was measured in terms of thiobarbituric reactive substances (TBARS) (mg of malondialdehyde (MDA)/kg of cheese) during cheese storage at 4 °C (Figure 3). After 6 days of storage, the highest lipid peroxidation level was measured for unwrapped cheese as compared to those wrapped by gelatin-based films. Cheese wrapped with gelatin film enriched with LSE3 at 20 μg/mL showed the lowest MDA level, which could be explained by the antioxidant properties of the film evidenced previously. In the same context, LSE3 could reduce oxygen, which would contribute to the barrier role of the film to oxygen that was one of the most important factors of peroxidation. Similarly, it was reported that gelatin hydrolysate, with high antioxidant potential, used in food coating improved its oxidative stability (Jridi et al., 2014b).

Figure 3.

Lipid peroxidation (mg MDA/kg cheese) of the different trials of cheese studied during refrigerated storage. U: unwrapped cheese; CF: cheese wrapped with the control gelatin-based film; F-LSE3: cheese wrapped with gelatin-based film enriched with LSE3 at 20 μg/mL. a, b Different letters indices indicate significant differences for the same sample in the same storage day (p < 0.05).

4. Conclusions

The dogfish gelatin-based film enriched with L. sativum extract was used in order to improve the cheese quality and to reduce the microbial proliferation during storage at 4 °C. The plant extract showed interesting antioxidant and antibacterial properties and its incorporation into gelatin-based film was effective in preserving the physico-chemical and microbiological quality of cheese during chilled storage. Therefore, it can be concluded that dogfish gelatin-based films, as an edible wrapping material, improved the quality and shelf-life of cheese products especially when enriched with bioactive compounds. However, new bioactive molecules and gelatin sources are required to develope active packaging as interesting alternative to traditional one.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Ali Salem: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Mourad Jridi: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Ola Abdelhedi, Nahed Fakhfakh, Moncef Nasri: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Frederic Debeaufort, Nacim Zouari: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research-Tunisia.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- Adilah A.N., Jamilah B., Noranizan M.A., Hanani Z.N. Utilization of mango peel extracts on the biodegradable films for active packaging. Food Packag. Shelf Life. 2018;16:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Afzaal M., Saeed F., Ateeq H., Ahmed A., Ahmad A., Tufail T., Ismail Z., Anjum F.M. Encapsulation of Bifidobacterium bifidum by internal gelation method to access the viability in cheddar cheese and under simulated gastrointestinal conditions. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020;8(6):2739–2747. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ait-Yahia O., Perreau F., Bouzroura S.A., Benmalek Y., Dob T., Belkebir A. Chemical composition and biological activities of n-butanol extract of Lepidium sativum L. (Brassicaceae) seed. Trop. J. Pharmaceut. Res. 2018;17(5):891–896. [Google Scholar]

- Alqahtani F.Y., Aleanizy F.S., Mahmoud A.Z., Farshori N.N., Alfaraj R., Al-Sheddi E.S., Alsarra I.A. Chemical composition and antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities of Lepidium sativum seed oil. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019;26(5):1089–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2018.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydemir T., Becerik S. Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of different extracts from Ocimum basilicum, Apium graveolens and Lepidium sativum seeds. J. Food Biochem. 2011;35(1):62–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez-Aguirre D., Barbosa-Cánovas G.V. Processing of soft hispanic cheese (“Queso Fresco”) using thermo-sonicated milk: a study of physicochemical characteristics and storage life. J. Food Sci. 2010;75(9):548–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.01850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez-Oria A., Rodríguez-Gutiérrez G., Vioque B., Rubio-Senent F., Fernández-Bolãnos J. Physical and functional properties of pectin-fish gelatin films containing the olive phenols hydroxytyrosol and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycol. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017;178:368–377. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bersuder P., Hole M., Smith G. Antioxidants from a heated histidine-glucose model system. I: investigation of the antioxidant role of histidine and isolation of antioxidants by high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1998;75(2):181–187. [Google Scholar]

- Bitencourt C.M., Fávaro-Trindade C.S., Sobral P.J.A., Carvalho R.A. Gelatin-based films additivated with curcuma ethanol extract: antioxidant activity and physical properties of films. Food Hydrocolloids. 2014;40:145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla J., Sobral P.J.A. Investigation of the physicochemical, antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of gelatin-chitosan edible film mixed with plant ethanolic extracts. Food Biosci. 2016;16:17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bojorges H., Ríos-Corripio M.A., Hernández-Cázares A.S., Hidalgo-Contreras J.V., Contreras-Oliva A. Effect of the application of an edible film with turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) on the oxidative stability of meat. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020;8(8):4308–4319. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buege J.A., Aust S.D. Microsomal lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1978;52:302–310. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)52032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa C., Lucera A., Lacivita V., Saccotelli M.A., Conte A., Del Nobile M.A. Packaging optimisation for portioned Canestrato di Moliterno cheese. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2016;69(3):401–409. [Google Scholar]

- Costa M.J., Maciel L.C., Teixeira J.A., Vicente A.A., Cerqueira M.A. Use of edible films and coatings in cheese preservation: opportunities and challenges. Food Res. Int. 2018;107:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Moraes J.O., Hilton S.T., Moraru C.I. The effect of pulsed light and starch films with antimicrobials on Listeria innocua and the quality of sliced cheddar cheese during refrigerated storage. Food Contr. 2020;112:107134. [Google Scholar]

- Decker E.A., Welch B. Role of ferritin as a lipid oxidation catalyst in muscle food. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1990;38(3):674–677. [Google Scholar]

- El-Maati M.F., Labib S.M., Al-Gaby A.M.A., Ramadan M.F. Antioxidant and antibacterial properties of different extracts of garden cress (Lepidium sativum L.) Zagazig J. Agric. Biochem. Appl. 2016;43(5):1685–1697. [Google Scholar]

- Etxabide A., Uranga J., Guerrero P., de la Caba K. Development of active gelatin films by means of valorisation of food processing waste: a review. Food Hydrocolloids. 2017;68:192–198. [Google Scholar]

- Feng X., Bansal N., Yang H. Fish gelatin combined with chitosan coating inhibits myofibril degradation of golden pomfret (Trachinotus blochii) fillet during cold storage. Food Chem. 2016;200:283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getahun T., Sharma V., Gupta N. Chemical composition, antibacterial and antioxidant activities of oils obtained by different extraction methods from Lepidium sativum L. seeds. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2020;156:112876. [Google Scholar]

- Haddar A., Sellimi S., Ghannouchi R., Alvarez O.M., Nasri M., Bougatef A. Functional, antioxidant and film-forming properties of tuna-skin gelatin with a brown algae extract. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2012;51(4):477–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homayounpour P., Shariatifar N., Alizadeh-Sani M. Development of nanochitosan-based active packaging films containing free and nanoliposome caraway (Carum carvi. L) seed extract. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021;9(1):553–563. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini S.F., Rezaei M., Zandi M., Farahmandghavi F. Development of bioactive fish gelatin/chitosan nanoparticles composite films with antimicrobial properties. Food Chem. 2016;194:1266–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T., Fang Z., Zhao H., Xu D., Yang W., Yu W., Zhang J. Physical properties and release kinetics of electron beam irradiated fish gelatin films with antioxidants of bamboo leaves. Food Biosci. 2020;36:100597. [Google Scholar]

- Jayanthi P., Lalitha P. Determination of the invitro reducing power of the aqueous extract of Eichhornia crassipes (Mart.) Solms. J. Pharm. Res. 2011;4(11):4003–4005. [Google Scholar]

- Jridi M., Abdelhedi O., Salem A., Kechaou H., Nasri M., Menchari Y. Physicochemical, antioxidant and antibacterial properties of fish gelatin-based edible films enriched with orange peel pectin: wrapping application. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020;103:105688. [Google Scholar]

- Jridi M., Bardaa S., Moalla D., Rebaii T., Souissi N., Sahnoun Z., Nasri M. Microstructure, rheological and wound healing properties of collagen-based gel from cuttlefish skin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015;77:369–374. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jridi M., Boughriba S., Abdelhedi O., Nciri H., Nasri R., Kchaou H., Kaya M., Sebai H., Zouari N., Nasri M. Investigation of physicochemical and antioxidant properties of gelatin edible film mixed with blood orange (Citrus sinensis) peel extract. Food Packag. Shelf Life. 2019;21:100342. [Google Scholar]

- Jridi M., Hajji S., Ayed H.B., Lassoued I., Mbarek A., Kammoun M. Physical, structural, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of gelatin-chitosan composite edible films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014;67:373–379. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jridi M., Lassoued I., Nasri R., Ayadi M.A., Nasri M., Souissi N. Characterization and potential use of cuttlefish skin gelatin hydrolysates prepared by different microbial proteases. BioMed Res. Int. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/461728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jridi M., Mora L., Souissi N., Aristoy M.-C., Nasri M., Toldrá F. Effects of active gelatin coated with henna (L. inermis) extract on beef meat quality during chilled storage. Food Contr. 2018;84:238–245. [Google Scholar]

- Kakaei S., Shahbazi Y. Effect of chitosan-gelatin film incorporated with ethanolic red grape seed extract and Ziziphora clinopodioides essential oil on survival of Listeria monocytogenes and chemical, microbial and sensory properties of minced trout fillet. LWT – Food Sci. Technol. 2016;72:432–438. [Google Scholar]

- Khan M.K., Zill-E-Huma, Dangles O. A comprehensive review on flavanones, the major citrus polyphenols. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2014;33(1):85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Khantaphant S., Benjakul S. Comparative study on the proteases from fish pyloric caeca and the use for production of gelatin hydrolysate with antioxidative activity. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 2008;151:410–419. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoshgozaran S., Azizi M.H., Bagheripoor-Fallah N. Evaluating the effect of modified atmosphere packaging on cheese characteristics: a review. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2012;9:21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kocaoğlu Aslanoğlu R., Olguntürk N. Color and visual complexity in abstract images: Part II. Color Res. Appl. 2019;44(6):941–947. [Google Scholar]

- Koleva I.I., Van Beek T.A., Linssen J.P., Groot A.D., Evstatieva L.N. Screening of plant extracts for antioxidant activity: a comparative study on three testing methods. Phytochem. Anal.: Int. J. Plant Chem. Biochem. Tech. 2002;13(1):8–17. doi: 10.1002/pca.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ksouda G., Sellimi S., Merlier F., Falcimaigne-Cordin A., Thomasset B., Nasri M., Hajji M. Composition, antibacterial and antioxidant activities of Pimpinella saxifraga essential oil and application to cheese preservation as coating additive. Food Chem. 2019;288:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.02.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.Y., Yang H.J., Song K.B. Application of a puffer fish skin gelatin film containing Moringa oleifera Lam. leaf extract to the packaging of Gouda cheese. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016;53(11):3876–3883. doi: 10.1007/s13197-016-2367-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.H., Miao J., Wu J.L., Chen S.F., Zhang Q.Q. Preparation and characterization of active gelatin-based films incorporated with natural antioxidants. Food Hydrocolloids. 2014;37:166–173. [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Antoniou J., Li Y., Yi J., Yokoyama W., Ma J. Preparation of gelatin films incorporated with tea polyphenol nanoparticles for enhancing controlled- release antioxidant properties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015;63:3987–3995. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manohar D., Shylaja H., Viswanatha G.L., Rajesh S. Antidiarrheal activity of methanolic extracts of Lepidium sativum in rodent. J. Nat. Remedies. 2009;9:197–201. [Google Scholar]

- Mastromatteo M., Lucera A., Esposto D., Conte A., Faccia M., Zambrini A.V., Del Nobile M.A. Packaging optimisation to prolong the shelf life of fiordilatte cheese. J. Dairy Res. 2015;1:43–51. doi: 10.1017/S0022029914000740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros B.G.D.S., Souza M.P., Carneiro-da-cunha M.G. Physical characterisation of an alginate/lysozyme nano-laminate coating and its evaluation on “Coalho” cheese shelf life. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2014;7(4):1088–1098. [Google Scholar]

- Mehmood M.H., Alkharfy K.M., Gilani A.H. Prokinetic and laxative activities of Lepidium sativum seed extract with species and tissue selective gut stimulatory actions. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;134(3):878–883. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzapour-Kouhdasht A., Moosavi-Nasab M. Shelf-life extension of whole shrimp using an active coating containing fish skin gelatin hydrolysates produced by a natural protease. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020;8(1):214–223. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie X., Gong Y., Wang N., Meng X. Preparation and characterization of edible myofibrillar protein-based film incorporated with grape seed procyanidins and green tea polyphenol. LWT – Food Sci. Technol. 2015;64(2):1042–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Olennikov D.N., Kashchenko N.I., Chirikova N.K. A novel HPLC-assisted method for investigation of the Fe2+-chelating activity of flavonoids and plant extracts. Molecules. 2014;19:18296–18316. doi: 10.3390/molecules191118296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafińska K., Pomastowski P., Rudnicka J., Krakowska A., Maruśka A., Narkute M., Buszewski B. Effect of solvent and extraction technique on composition and biological activity of Lepidium sativum extracts. Food Chem. 2019;289:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos M., Valdes A., Beltran A., Garrigós M.C. Gelatin-based films and coatings for food packaging applications. Coatings. 2016;6(4):41. [Google Scholar]

- Rangaraj V.M., Rambabu K., Banat F., Mittal V. Effect of date fruit waste extract as an antioxidant additive on the properties of active gelatin films. Food Chem. 2021;355:129631. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riahi Z., Priyadarshi R., Rhim J.W., Bagheri R. Gelatin-based functional films integrated with grapefruit seed extract and TiO2 for active food packaging applications. Food Hydrocolloids. 2021;112:106314. [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldoni A.N., Palatnik D.R., Zaritzky N., Campderrós M.E. Soft cheese-like product development enriched with soy protein concentrates. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2014;55:139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Salem A., Fakhfakh N., Jridi M., Abdelhedi O., Nasri M., Debeaufort F., Zouari N. Microstructure and characteristic properties of dogfish skin gelatin gels prepared by freeze/spray-drying methods. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;162:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobral P.J.A., Habitante A.M.Q.B. Phase transitions of pigskin gelatin. Food Hydrocolloids. 2001;15(4-6):377–382. [Google Scholar]

- Valgas C., de Souza S.M., Smânia E.F.A., Smânia A., Jr. Screening methods to determine antibacterial activity of natural products. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2007;38(2):369–380. [Google Scholar]

- Vanden Berghe D.A., Vlietinck A.J. In: Methods in Plant Biochemistry. Dey P.M., Harborne J.B., editors. Academic Press; London: 1991. Screening methods for antibacterial and antiviral agents from higher plants; pp. 47–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wade D., Silveira A., Rollins-Smith L., Bergman T., Silberring J., Lankinen H. Hematological and antifungal properties of temporin A and a cecropin A-temporin A hybrid. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2001;48:1185–1189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Chen S., Ge S., Miao J., Li J., Zhang Q. Preparation, properties and antioxidant activity of an active film from silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) skin gelatin incorporated with green tea extract. Food Hydrocolloids. 2013;32(1):42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim A., Mavi A., Kara A.A. Determination of antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Rumex crispus L. extracts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001;49(8):4083–4089. doi: 10.1021/jf0103572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zia-Ul-Haq M., Ahmad S., Calani L., Mazzeo T., Del Rio D., Pellegrini N., De Feo V. Compositional study and antioxidant potential of Ipomoea hederacea Jacq. And Lepidium sativum L. Seeds. Molecules. 2012;17(9):10306–10321. doi: 10.3390/molecules170910306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.