Abstract

Theresa Marteau and colleagues argue for rapid, radical changes to the infrastructure and pricing systems that currently support unhealthy unsustainable behaviour

Many major economies, including the US, EU, and UK, have committed to net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 to limit climate change. Immediate action is needed to hit this target and to minimise cumulative emissions. Current commitments are, however, unmatched by action.1 The UK government, for example, though among the first to set a legally binding target of net zero by 2050, has so far fully implemented only 11 of 92 policy recommendations from its climate change committee and is not on track to meet net zero or the medium term carbon budgets.2

The latest International Panel on Climate Change report estimates that if global emissions are halved by 2030 and net zero is reached by 2050, the current rise in temperatures could be halted and possibly reversed.3 The 26th UN climate change conference (COP26) in November 2021 offers a precious opportunity to get back on track.

Behaviour change by individuals, commercial entities, and policy makers is critical to achieving net zero in all domains. Here we focus on behaviour concerning diet and land travel, given their importance for both achieving net zero and improving population health, but the approaches we outline are also applicable to other behaviours.

Diet and land travel contribute an estimated 26%4 and 12% of greenhouse gas emissions, respectively.1 Cutting these emissions would also benefit health by reducing air pollution—now the greatest external threat to human health5—increasing physical activity, and healthier diets, thereby tackling major risk factors for non-communicable disease globally.6 7 8

Changes in demand are going to be critical to achieving net zero, alongside technological innovation.9 Dietary change is likely to deliver far greater environmental benefits than can be achieved by food producers.4 Similarly, for land travel, reducing demand for high emission vehicles would deliver important reductions: sport utility vehicles were responsible for the second largest increase (after power) of global carbon emissions between 2010 and 2018.10 Shifting demand equitably, however, requires structural interventions to drive behaviour change by whole populations.

We consider the behaviour of three groups central to achieving net zero by 2050: the public (both as citizens and consumers), policy makers, and private sector leaders.11

Changing behaviour of the public at scale

Adopting the largely plant based planetary health diet12 and taking most journeys using a combination of walking, cycling, and public transport would substantially reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve our health.

Animal sourced foods (meat, dairy, fish) generally use much more land and water and create more greenhouse gases than plant sourced food.4 Sustainable and healthy diets consist largely of diverse plant foods with low amounts of animal source foods, unsaturated rather than saturated fats, and limited amounts of refined grains, highly processed foods, and added sugars.12 The nature and scale of change required depends on existing dietary patterns and nutritional status of local populations.13 For example, to meet the planetary health diet recommendations, average meat consumption in Africa can slightly increase (2%), whereas in North America and Europe it needs to fall by 79% and 68%, respectively.12 14

Sustainable land travel will involve substantially fewer journeys by car and more journeys taken by foot, bicycle, and public transport, ensuring that all transport is carbon neutral and powered by renewable energy.10 This requires a transformation of the energy sector and transport infrastructure, prioritising active and public transport over road building.10 15 Estimates of the nature and scale of change needed vary. In the UK, for example, a central net zero pathway includes car mileage per driver falling by 10% by 2050,2 whereas other analysis calls for a reduction between 20% and 60% by 2030, depending on the speed of transition to electric vehicles.16

Changing behaviour at scale is difficult, especially when the behaviours to be changed are cued, reinforced, and maintained by the physical, economic, and social environments in which they occur—as is the case for diet and land travel. Multiple interventions will be required in all these contexts to achieve the size of change needed for net zero.

Education alone is not sufficient

People’s knowledge of which behaviours generate the most greenhouse gases is generally poor. For example, only 20% of people in a large international survey identified eating a plant based diet or not owning a car as among the most effective actions.17 Providing information to correct such misperceptions could, importantly, increase public support for government policies for net zero,18 but such information is unlikely to change these behaviours.

Information can be extremely effective at changing behaviour when it concerns serious, immediate threats to life. A sign warning of shark infested waters stops most people from swimming. But when the information concerns less immediate threats it often has minimal effects on behaviour.19 20 For example, information campaigns on the health benefits of consuming more fruit and vegetables successfully increased awareness but did not alter consumption.21 Similarly, conservation scientists were not found to have lower environmental footprints than other professionals despite their greater environmental knowledge.22

Changing physical and economic environments

The interventions with the most potential to change routine or habitual behaviour at scale target whole populations and involve changes to the systems shaping and maintaining the behaviour.23 24 25 26 They can be described as structural, designed to create environments that readily enable sustainable behaviours and make unsustainable behaviours more difficult.27 These interventions also place lower demands on the cognitive, social, and material resources of individuals than those based on providing advice and guidance, thereby having greater potential to achieve change equitably.28 29 For example, increasing the proportion of vegetarian meal choices in UK cafeterias from one in four to two in four increased their selection from 24% to 39%.30 Construction of an urban greenway in the US increased journeys by bike 250% among those living closest.31

Table 1 shows interventions for low carbon diets and land travel, grouped by whether they change the physical or economic environments in which the behaviours occur.23 32 33 34 35How these interventions can best be implemented partly depends on whether they concern public or private sector settings. For public settings, changing procurement standards to include only sustainable healthy options would be a good start. Portugal and Scotland have regulations to increase the availability of sustainable and healthier foods in public sector settings.36 56 In private sector settings regulation is needed since voluntary agreements to improve public health, mainly comprising pledges to interventions of known limited effectiveness such as providing information,57 have been largely ineffective.57

Table 1.

Population level interventions to change behaviour for net zero diets and travel on land23 32 33 34 35

| Intervention type | Diets | Travel on land |

|---|---|---|

| Physical environment—Altering availability, position, presentation, or size of products or objects within stores, cafes, and restaurants (micro) and within villages, towns, and cities (macro) to decrease the opportunities to consume high emission products and activities and to increase the opportunities to consume low emission products and activities | •Increase proportions of plant based food options in food retail outlets and on menus30

36

•Reduce portion and package sizes of energy dense foods, ultra-processed foods, meat, and dairy foods 35 37 •Prominent positioning only for healthy, sustainable foods: place on aisle ends healthier, more sustainable foods,38 39 place meat alternatives with meat,40 place vegetarian options first41 •Reduce density of outlets for ultra-processed foods including meat42 |

•Increase availability of safe and attractive cycling and walking routes, designed around green and blue spaces, linked to good public transport networks.31

32

43

44

•Frequent, reliable, integrated public transport networks (using renewable energy) with provision for wheelchairs, pushchairs, shopping, and bikes45 46 •Restricting availability and attractiveness of car use—eg, car-free zones, limited parking, traffic calming measures, and low speed limits47 |

| Economic environment—Changing prices of goods and services by introducing, modifying, or removing taxes, subsidies, and other material incentives to decrease the affordability of high emission products and activities and to increase the affordability of low emission products and activities | •Remove subsidies on livestock farming48

•Increase prices of carbon intense foods, including processed and red meat, dairy products, and ultra-processed foods49 •Reduce prices of low processed and plant based foods 49 50 |

•Remove subsidies on fossil fuels51

•Increase prices of fossil fuel52 •Road user charging for private vehicles (eg, congestion zone charging and increased parking costs)32 53 54 •Low cost public transport55 |

Interventions that decrease the affordability of unhealthy unsustainable options and increase the affordability of healthier sustainable options would also help change public behaviour, particularly in combination.34 58 These include removing subsidies on high emission products such as livestock and fossil fuels and using taxes and other price based mechanisms to reflect the emissions associated with different products and activities.

The effect of price based interventions will depend on their size (eg, the price at which carbon is set) and the package of measures within which they are implemented. For example, participation in US energy conservation programmes varied by a factor of 10 depending on concomitant strategies and how the programmes were presented to participants.59 It will also vary by region, with more uncertainty about effects of interventions in middle and lower income countries where less evidence has been generated.60 A further layer of uncertainty reflects the difficulty of predicting collective behavioural responses to such interventions.61 Nonetheless, the strongest evidence on achieving changes in behaviour that would reduce emissions is for structural interventions. Given the need to halve emissions in the next decade, planning has to start now to implement all the interventions listed in table 1 and more, with evaluations designed into the rollout phases to enable rapid adjustments to optimise their outcomes.

Fair interventions

Interventions need to be fair and equitable as well as effective to gain public support, which in turn increases their political acceptability.18 62 63 Globally, the wealthiest 10% consume more than 20 times more energy than the poorest 10%.64 Pricing carbon on energy and land use at levels that could achieve net zero by 2050—perhaps reaching more than $560 (£410; €480) per tonne of CO2 equivalent65 66—would increase the price of transport and food, disproportionately affecting the poorest and those living in rural areas. Any such policy would need to be part of a package that, at a minimum, shields poorer households but better, is part of broader sets of policies that tackle poverty and inequality both within and between nations.67

Policy makers and private sector leaders

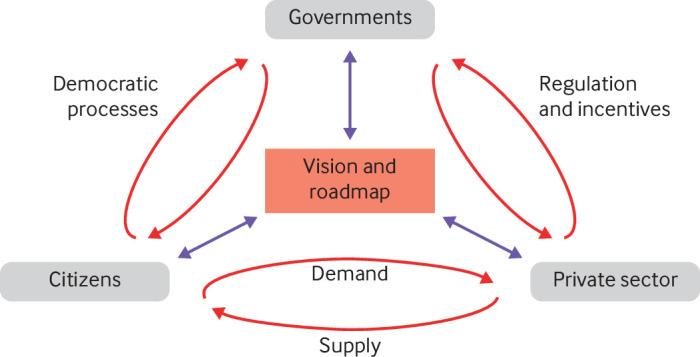

Changing the behaviour of the public at scale requires substantial changes to the behaviour of policy makers, private sector leaders, and citizens. Governments have an obligation to serve public interests, including protection against powerful commercial interests (box 1). It also includes listening and responding to citizens’ views. Behaviours within these three groups that create barriers to implementing effective interventions of the kind shown in table 1 include inadequate political leadership and governance to enact policies, strong opposition by powerful commercial interests, and lack of public demand for policy action.75 Countering these behaviours and enabling positive ones will be crucial to achieving net zero (fig 1).

Box 1. Actions to protect policies for net zero from corporate interference.

Exclude corporations from setting and implementing policies, as exists for the tobacco industry under article 5.3 of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control68 69

Prevent and manage conflicts of interest in policy making by, for example, training policy makers, developing an index assessing impacts of individual corporate organisations, and setting up independent panels to advise on corporate engagement in policy making 70 71

Establish statutory registers of corporations lobbying governments to allow public scrutiny of the nature and scale of their activities, including all donations72

Use regulations, frameworks, and criminal law to prevent corporations from misleading the public and causing environmental and other harms, including destroying ecosystems 73 74

Fig 1.

Interconnected behaviours of government, private sector, and citizens to achieve net zero

Citizens also have an important role in demanding change from industry, through consumer choices and civil society organisations, as well as demanding change from more cautious governments through the ballot box and engagement in deliberative processes. For example, citizen assemblies on climate change consistently recommend more ambitious policies for net zero than those pursued by their governments. The UK Climate Assembly proposed a 20-40% reduction in consumption of all meat and dairy,63 a proposal yet to find favour with the UK government.76 In France, President Macron’s government has not fully enacted the French citizen assembly’s recommendations. For example, its proposal to end all domestic flights for journeys that would take less than four hours by rail was lowered to journeys taking 2.5 hours.77 While legislation to implement recommendations from the Irish citizen’s assembly on climate change was unsuccessful, it seems to have encouraged grassroots climate politics, which may facilitate more radical change longer term.78 Healthcare professionals also have a key role as advocates for change at the levels of government79 and health systems.80

Public support for change is lower when it affects current behaviour and trust in governments is low.81 82 83 Support can be increased by ensuring policies are perceived as both fair and effective.18 62 Support can also increase after an intervention is implemented, reflecting the bidirectional relation between behaviour and attitudes. For example, public support for congestion pricing increased after its introduction in many cities, reflecting both changes in attitudes and acceptance of the status quo.84

Private sector organisations must also make substantial changes to align with net zero, from agricultural and food production, the extractive industries, manufacturing, transport, and the energy sector. As in any transition, there will be winners and losers. The focus for government should be to encourage fast adapting organisations—new and old—that will speed up the transition to net zero.

A major threat comes from some private sector organisations with most to lose. This includes fossil fuel companies that have engaged in activities to deny or cast doubt on human induced climate change and the need for a low carbon transition.85 86 In 2021, an Exxon lobbyist was secretly recorded by Greenpeace stating that the oil company worked with “shadow groups” to undermine climate science and that the company’s key climate commitments were disingenuous.87 Large agribusinesses and parts of the food industry also engage in similar activities to prevent or delay effective policies for dietary change.88 89 An analysis of documents from the meat industry found that they framed the health and environmental effects of red and processed meats to minimise perceptions of harm and to encourage continued consumption.90 Of particular concern, is the influence of vested corporate interests on the activities of the World Health Organization and UN bodies.91 92

While these activities—variously described as corporate political activity and corporate capture of policy—are well documented, effective ways of safeguarding public policy from them are less researched.93 Box 1 lists some actions that could protect policies for net zero from corporate interference.

Towards a fair transitioned future

Complex coordinated behaviour can be mobilised by a shared, positive narrative, reflecting collective goals,94 alongside a clear vision, making vivid the many benefits of a net zero world, with a roadmap and timelines. The development of such a vision—both global and regional—is a priority and requires co-creation by citizens, governments, and industries, informed by scientific expertise and protected from corporate interference.

Activities of high carbon industries pose a major threat to effective policies by deflecting or delaying their implementation. Governments and UN bodies, emboldened by citizens and civil society organisations, can and should safeguard policies for a fair and just transition to net zero. COP26 is an opportunity for international binding commitments that rapidly get us back on track for net zero by 2050. With sufficient daring from the world’s governments, the flexibility, creativity, and social nature of human behaviour can achieve a just transition to net zero thereby protecting the health of current and future generations.

Key messages.

Current government policies globally are insufficient for the rapid decarbonisation needed for net zero by 2050

Changing behaviour across populations is key to achieving this as technological innovation will be insufficient

Changing behaviour at scale requires changing the environments that drive the behaviour

Changes to diet and land travel can be achieved through policies to increase the availability and affordability of healthier and more sustainable options.

Policies for net zero need to be driven by evidence and citizens’ values, safeguarded from corporate interference

Acknowledgments

We thank Eoin Devane, Gareth Hollands, David Joffe, Mark Petticrew, and Harry Rutter for comments on earlier drafts.

Contributors and sources: TMM is a psychologist and behavioural scientist who has researched and written extensively on changing behaviour at scale to improve population health. NC is a cognitive psychologist and behavioural scientist with expertise in reasoning and decision making applied to public policy including climate change. EEG is a researcher with expertise in conservation science and behavioural science. TMM developed the outline for the paper and together with NC prepared the first draft to which EG added salient evidence. All authors edited the manuscript before approving the final version. TMM is guarantor of the article.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare: NC is a member of the UK Climate Change Committee, co-founder of Decision Technology, and a registered speaker with JLA and Speaker’s Corner; EEG is funded by philanthropic donation from Sainsbury’s. The retailer had no role in the article.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.UN Environment Programme. Emissions gap report 2020. 2020. https://www.unep.org/emissions-gap-report-2020

- 2.UK Climate Change Committee. Progress in reducing emissions 2021: Report to parliament. 2021. www.theccc.org.uk/publications

- 3.IPCC. Climate change 2021: the physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the sixth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change . 2021. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/

- 4. Poore J, Nemecek T. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science 2018;360:987-92. 10.1126/science.aaq0216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee K, Greenstone M. The air quality life index. Energy Policy Institute, University of Chicago (EPIC). 2021 https://aqli.epic.uchicago.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/AQLI_2021-Report.EnglishGlobal.pdf

- 6. Haines A. Health co-benefits of climate action. Lancet Planet Health 2017;1:e4-5. 10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30003-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rutter H, Horton R, Marteau TM. The Lancet-Chatham House Commission on improving population health post COVID-19. Lancet 2020;396:152-3. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31184-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. WHO Factsheets: non communicable diseases. 2021 https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases

- 9. Creutzig F, Roy J, Lamb WF, et al. Towards demand-side solutions for mitigating climate change. Nat Clim Chang 2018;8:260-3. 10.1038/s41558-018-0121-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.International Energy Agency. Net zero by 2050. 2021 https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050

- 11. Balmford A, Bradbury RB, Bauer JM, et al. Making more effective use of human behavioural science in conservation interventions. Biol Conserv 2021;261:109256 10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109256 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Willett W, Rockström J, Loken B, et al. Food in the anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019;393:447-92. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Springmann M, Wiebe K, Mason-D’Croz D, Sulser TB, Rayner M, Scarborough P. Health and nutritional aspects of sustainable diet strategies and their association with environmental impacts: a global modelling analysis with country-level detail. Lancet Planet Health 2018;2:e451-61. 10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30206-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Springmann M, Spajic L, Clark MA, et al. The healthiness and sustainability of national and global food based dietary guidelines: modelling study. BMJ 2020;370:m2322. 10.1136/bmj.m2322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mattioli G, Roberts C, Steinberger JK, Brown A. The political economy of car dependence: A systems of provision approach. Energy Res Soc Sci 2020;66:101486. 10.1016/j.erss.2020.101486 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopkinson L, Sloman L. More than electric cars. 2019. https://policy.friendsoftheearth.uk/insight/more-electric-cars

- 17.Bruce-Lockhart C. Clothes dryer vs the car: carbon footprint misconceptions. Financial Times 2021 Apr 17. https://www.ft.com/content/c5e0cdf2-aaef-4812-9d8e-f47dbcded55c

- 18. Reynolds JP, Stautz K, Pilling M, van der Linden S, Marteau TM. Communicating the effectiveness and ineffectiveness of government policies and their impact on public support: a systematic review with meta-analysis. R Soc Open Sci 2020;7:190522. 10.1098/rsos.190522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hollands GJ, French DP, Griffin SJ, et al. The impact of communicating genetic risks of disease on risk-reducing health behaviour: systematic review with meta-analysis. BMJ 2016;352:i1102. https://www.bmj.com/content/352/bmj.i1102. 10.1136/bmj.i1102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hornsey MJ, Harris EA, Bain PG, Fielding KS. Meta-analyses of the determinants and outcomes of belief in climate change. Nat Clim Chang 2016;6:622-6 10.1038/nclimate2943 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wood W, Neal D. Healthy through habit: Interventions for initiating & maintaining health behavior change. Behav Sci Policy 2016;2:71-83 10.1353/bsp.2016.0008 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Balmford A, Cole L, Sandbrook C, Fisher B. The environmental footprints of conservationists, economists and medics compared. Biol Conserv 2017;214:260-9 10.1016/j.biocon.2017.07.035 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marteau TM, White M, Rutter H, et al. Increasing healthy life expectancy equitably in England by 5 years by 2035: could it be achieved? Lancet 2019;393:2571-3. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31510-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hollands GJ, Bignardi G, Johnston M, et al. The TIPPME intervention typology for changing environments to change behaviour. Nat Hum Behav 2017;1:0140. 10.1038/s41562-017-0140 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Whitmarsh L, Poortinga W, Capstick S. Behaviour change to address climate change. Curr Opin Psychol 2021;42:76-81. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marteau TM, Hollands GJ, Fletcher PC. Changing human behavior to prevent disease: the importance of targeting automatic processes. Science 2012;337:1492-5. 10.1126/science.1226918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mazar A, Tomaino G, Carmon Z, Wood W. Habits to save our habitat: Using the psychology of habits to promote sustainability. Behav Sci Policy (forthcoming). [Google Scholar]

- 28. Adams J, Mytton O, White M, Monsivais P. Why are some population interventions for diet and obesity more equitable and effective than others? The role of individual agency. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1001990. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marteau TM, Rutter H, Marmot M. Changing behaviour: an essential component of tackling health inequalities. BMJ 2021;372:n332. 10.1136/bmj.n332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Garnett EE, Balmford A, Sandbrook C, Pilling MA, Marteau TM. Impact of increasing vegetarian availability on meal selection and sales in cafeterias. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:20923-9. 10.1073/pnas.1907207116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Frank LD, Hong A, Ngo VD. Build it and they will cycle: causal evidence from the downtown Vancouver Comox Greenway. Transp Policy 2021;105:1-11 10.1016/j.tranpol.2021.02.003 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mytton O, Aldridge R, McGowan J, et al. Identifying the most promising population preventive interventions to add 5 years to healthy life expectancy by 2035, and reduce the gap between the rich and the poor in England. Behaviour and Health Research Unit, Institute of Public Health, University of Cambridge, 2019. https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/294711

- 33.World Health Organization. Tackling NCDs: “best buys” and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases . 2017. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-NMH-NVI-17.9

- 34. Bloomberg MR, Summers LH, Ahmed M, et al. Health taxes to save lives: employing effective excise taxes on tobacco, alcohol, and sugary beverages. Bloomberg Philanthorpies, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bianchi F, Garnett E, Dorsel C, Aveyard P, Jebb SA. Restructuring physical micro-environments to reduce the demand for meat: a systematic review and qualitative comparative analysis. Lancet Planet Health 2018;2:e384-97. 10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30188-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henriques JG. It’s already law: a vegetarian dish is mandatory in all public canteens. Público 2017 Mar 3. https://www.publico.pt/2017/03/03/sociedade/noticia/ja-e-lei-um-prato-vegetariano-em-todas-as-cantinas-publicas-1763917

- 37. Reynolds JP, Ventsel M, Kosīte D, et al. Impact of decreasing the proportion of higher energy foods and reducing portion sizes on food purchased in worksite cafeterias: A stepped-wedge randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med 2021;18:e1003743. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nakamura R, Pechey R, Suhrcke M, Jebb SA, Marteau TM. Sales impact of displaying alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages in end-of-aisle locations: an observational study. Soc Sci Med 2014;108:68-73. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.02.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vogel C, Crozier S, Penn-Newman D, et al. Altering product placement to create a healthier layout in supermarkets: Outcomes on store sales, customer purchasing, and diet in a prospective matched controlled cluster study. PLoS Med 2021;18:e1003729. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Piernas C, Cook B, Stevens R, et al. Estimating the effect of moving meat-free products to the meat aisle on sales of meat and meat-free products: A non-randomised controlled intervention study in a large UK supermarket chain. PLoS Med 2021;18:e1003715. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Garnett E, Marteau T, Sandbrook C, Pilling M, Balmford A. Order of meals at the counter and distance between options affect student cafeteria vegetarian sales. Nat Food 2020;1:485-8 10.1038/s43016-020-0132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Burgoine T, Sarkar C, Webster CJ, Monsivais P. Examining the interaction of fast-food outlet exposure and income on diet and obesity: evidence from 51,361 UK Biobank participants. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2018;15:71. 10.1186/s12966-018-0699-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ciclovía Recreativa. Ciclovía recreativa implementation and advocacy manual. https://cicloviarecreativa.uniandes.edu.co/english/introduction.html

- 44.C40. Case study: Freiburg. An inspirational city powered by solar, where a third of all journeys are by bike. 2011. https://www.c40.org/case_studies/freiburg-an-inspirational-city-powered-by-solar-where-a-third-of-all-journeys-are-by-bike

- 45.Montgomery J. The 15-minute city. 2020. https://www.thersa.org/comment/2020/10/the-15-minute-city

- 46. Sagaris L. Citizen participation for sustainable transport: lessons for change from Santiago and Temuco, Chile. Res Transp Econ 2018;69:402-10 10.1016/j.retrec.2018.05.001 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Interreg Europe. Promoting active modes of transport: a policy brief from the policy learning platform on low-carbon economy. 2019. https://www.interregeurope.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/plp_uploads/policy_briefs/TO4_PolicyBrief_Active_Modes.pdf

- 48. Jansson T, Nordin I, Wilhelmsson F, et al. Coupled agricultural subsidies in the EU undermine climate efforts. Appl Econ Perspect Policy 2020;00:1-17 10.1002/aepp.13092 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Springmann M, Mason-D’Croz D, Robinson S, et al. Mitigation potential and global health impacts from emissions pricing of food commodities. Nat Clim Chang 2017;7:69-74 10.1038/nclimate3155 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Garnett EE, Balmford A, Marteau TM, Pilling MA, Sandbrook C. Price of change: Does a small alteration to the price of meat and vegetarian options affect their sales? J Environ Psychol 2021;75:101589. 10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101589 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Erickson P, van Asselt H, Koplow D, et al. Why fossil fuel producer subsidies matter. Nature 2020;578:E1-4. 10.1038/s41586-019-1920-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Venturini G, Karlsson K, Münster M. Impact and effectiveness of transport policy measures for a renewable-based energy system. Energy Policy 2019;133:110900. 10.1016/j.enpol.2019.110900 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Arnesen P, Seter H, Tveit Ø, Bjerke MM. Geofencing to enable differentiated road user charging. Transp Res Rec 2021;2676:299-306. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Laverty AA, Vamos EP, Panter J, Millett C. Road user charging: a policy whose time has finally arrived. Lancet Planet Health 2020;4:e499-500. 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30244-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alston P, Khawaja B, Riddell R. Public transport, private profit: The human cost of privatizing buses in the United Kingdom . 2021. https://chrgj.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Report-Public-Transport-Private-Profit.pdf

- 56.Scottish Government. Criteria for the healthcare retail standard. 2016. https://www.gov.scot/publications/criteria-healthcare-retail-standard-1

- 57. Knai C, Petticrew M, Douglas N, et al. The public health responsibility deal: using a systems-level analysis to understand the lack of impact on alcohol, food, physical activity, and workplace health sub-systems. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:E2895. 10.3390/ijerph15122895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Springmann M, Mason-D’Croz D, Robinson S, et al. Health-motivated taxes on red and processed meat: A modelling study on optimal tax levels and associated health impacts. PLoS One 2018;13:e0204139. 10.1371/journal.pone.0204139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Stern PC, Aronson E, Darley JM, et al. The effectiveness of incentives for residential energy conservation. Eval Rev 1986;10:147-76. 10.1177/0193841X8601000201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carmichael R. Behaviour change, public engagement and net zero. A report for the Committee on Climate Change. 2019. https://www.theccc.org.uk/publications/

- 61. Bak-Coleman JB, Alfano M, Barfuss W, et al. Stewardship of global collective behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021;118:e2025764118. 10.1073/pnas.2025764118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carmichael R, Halttunen K, Palazzo Corner S, Rhodes A. Paying for UK net zero: principles for a cost-effective and fair transition . 2021. https://spiral.imperial.ac.uk/handle/10044/1/86323

- 63.Climate Assembly UK. The path to net zero; Climate Assembly UK report. 2020. https://www.climateassembly.uk/report/

- 64. Oswald Y, Owen A, Steinberger JK. Large inequality in international and intranational energy footprints between income groups and across consumption categories. Nat Energy 2020;5:231-9. 10.1038/s41560-020-0579-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. MAgPIE – model of agricultural production and its impact on the environment: description of the global land use allocation model MAgPIE . https://www.pik-potsdam.de/en/institute/departments/activities/land-use-modelling/magpie

- 66.Rogelj J, Shindell D, Jiang K, et al. Mitigation pathways compatible with 1.5°C in the context of sustainable development. In: Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC special report. 2021. https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/

- 67.Burke J, Fankhauser S, Kazaglis A, et al. Distributional impacts of a carbon tax in the UK: report 2–analysis by income decile . 2020. https://www.lse.ac.uk/GranthamInstitute/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Distributional-impacts-of-a-UK-carbon-tax_Report-2_analysis-by-income-decile.pdf

- 68.World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: WHO; 2003. https://www.who.int/fctc/text_download/en/

- 69. Chung-Hall J, Craig L, Gravely S, Sansone N, Fong GT. Impact of the WHO FCTC over the first decade: a global evidence review prepared for the Impact Assessment Expert Group. Tob Control 2019;28(Suppl 2):s119-28. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Marks J. The perils of partnership: industry influence, institutional integrity, and public health. Oxford University Press, 2019. 10.1093/oso/9780190907082.001.0001 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Buse K, Mialon M, Jones A. Thinking politically about UN political declarations: a recipe for healthier commitments—free of commercial interests. Comment on “Competing frames in global health governance: an analysis of stakeholder influence on the political declaration on non-communicable diseases”. Int J Health Policy Manag 2021. https://www.ijhpm.com/article_4094.html [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shone A, Wilkinson P. Corporate political engagement index 2015 . Transparency International UK, 2015. https://www.transparency.org.uk/publications/corporate-political-engagement-index-2015

- 73. Thornton J, Covington H. Climate change before the court. Nat Geosci 2016;9:3-5 10.1038/ngeo2612 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child . 1990. https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx

- 75. Swinburn BA, Kraak VI, Allender S, et al. The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: The Lancet Commission report. Lancet 2019;393:791-846. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32822-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Case P, Clarke P. Meat and dairy intake escapes stricter UK climate goals. Farmers Weekly 2021 Apr 21. https://www.fwi.co.uk/news/environment/meat-and-dairy-targeted-in-tougher-uk-climate-goals

- 77.Farand C. French draft climate law criticised for weakening ambition of citizens’ assembly. Climate Home News 2021 Jan 12. https://www.climatechangenews.com/2021/01/12/french-draft-climate-law-criticised-weakening-ambition-citizens-assembly/

- 78. Fitzgerald LM, Tobin P, Burns C, Eckersley P. The ‘stifling’ of new climate politics in Ireland. Politics Gov 2021;9:41-50. 10.17645/pag.v9i2.3797 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Atwoli L, Baqui AH, Benfield T, et al. Call for emergency action to limit global temperature increases, restore biodiversity, and protect health. BMJ 2021;374:n1734. 10.1136/bmj.n1734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.NHS England. Greener NHS: national ambition. https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/national-ambition/

- 81. Reynolds JP, Archer S, Pilling M, Kenny M, Hollands GJ, Marteau TM. Public acceptability of nudging and taxing to reduce consumption of alcohol, tobacco, and food: A population-based survey experiment. Soc Sci Med 2019;236:112395. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Levi S. Why hate carbon taxes? Machine learning evidence on the roles of personal responsibility, trust, revenue recycling, and other factors across 23 European countries. Energy Res Soc Sci 2021;73:101883. 10.1016/j.erss.2020.101883 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Zhang Y, Abbas M, Iqbal W. Analyzing sentiments and attitudes toward carbon taxation in Europe, USA, South Africa, Canada and Australia. Sustain Prod Consum 2021;28:241-53 10.1016/j.spc.2021.04.010 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Hess S, Börjesson M. Understanding attitudes towards congestion pricing: a latent variable investigation with data from four cities. Transp Lett 2019;11:63-77 10.1080/19427867.2016.1271762 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Mann ME. The new climate war: the fight to take back our planet. Scribe Publications, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 86. Oreskes N. Merchants of doubt: how a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming. Bloomsbury, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Exxon Mobil suspended from the climate leadership council, following secret Greenpeace recording. Washington Post 2021 Aug 6. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/exxon-mobil-suspended-from-the-climate-leadership-council-following-secret-greenpeace-recording/2021/08/06/2db6da3e-f6a6-11eb-9068-bf463c8c74de_story.html

- 88. Mialon M, Swinburn B, Sacks G. A proposed approach to systematically identify and monitor the corporate political activity of the food industry with respect to public health using publicly available information. Obes Rev 2015;16:519-30. 10.1111/obr.12289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Gostin LO. “Big food” is making America sick. Milbank Q 2016;94:480-4. 10.1111/1468-0009.12209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Clare K, Maani N, Milner J. Meat, money and messaging: how the environmental and health harms of red and processed meat consumption are framed by the meat industry. Food Policy (forthcoming) [Google Scholar]

- 91. Lauber K, Rutter H, Gilmore AB. Big food and the World Health Organization: a qualitative study of industry attempts to influence global-level non-communicable disease policy. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e005216. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Joint Civil Society. Ending corporate capture of the United Nations . 2021. https://www.foei.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Statement-on-UN-Corporate-Capture-EN.pdf

- 93. de Lacy-Vawdon C, Livingstone C. Defining the commercial determinants of health: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2020;20:1022. 10.1186/s12889-020-09126-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Misyak JB, Melkonyan T, Zeitoun H, Chater N. Unwritten rules: virtual bargaining underpins social interaction, culture, and society. Trends Cogn Sci 2014;18:512-9. 10.1016/j.tics.2014.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]