Abstract

Introduction:

Emotional eating in bariatric surgery patients is inconsistently linked with poor post-operative weight loss and eating behaviors, and much research to date is atheoretical. To examine theory-informed correlates of pre-operative emotional eating, the present cross-sectional analysis examined paths through which experienced weight bias and internalized weight bias (IWB) may associate with emotional eating among individuals seeking bariatric surgery.

Method:

We examined associations of experienced weight bias, IWB, shame, self-compassion, and emotional eating in patients from a surgical weight loss clinic (N= 229, 82.1% Female, M. BMI: 48±9). Participants completed a survey of validated self-report measures that were linked to BMI from the patient medical record. Multiple regression models tested associations between study constructs while PROCESS bootstrapping estimates tested the following hypothesized mediation model: IWB ⟶internalized shame⟶self-compassion⟶emotional eating. Primary analyses controlled for Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE), a common confound in weight bias research. Secondary analyses controlled for depressive/anxiety symptoms from patient medical record (n=196).

Results:

After covariates and ACE, each construct accounted for significant unique variance in emotional eating. However, experienced weight bias was no longer significant, and internalized shame marginal, after controlling for depressive/anxiety symptoms. In a mediation model, IWB was linked to greater emotional eating through heightened internalized shame and low self-compassion, including after controlling for depressive/anxiety symptoms.

Conclusion:

Pre-bariatric surgery, IWB may signal risk of emotional eating, with potential implications for post-operative trajectories. Self-compassion may be a useful treatment target to reduce IWB, internalized shame, and related emotional eating in bariatric surgery patients. Further longitudinal research is needed.

Keywords: Emotional eating, weight stigma, bariatric surgery, psychosocial, self-compassion

Introduction

Experiences of weight bias (i.e., weight-based stigmatization, discrimination, or prejudice) and weight bias internalization (i.e., internalization of weight bias as negative weight-related self-appraisals) are psychosocial risk factors associated with negative affect, poor dietary adherence, and less weight loss in pre- and post-operative bariatric surgery patients [1–4]. Increasing research in non-bariatric samples suggests internalized weight bias (I WB) may account for the adverse associations of experienced weight bias with poor behavioral health, including poor eating behaviors [5]. Moreover, body shame (i.e., shame regarding one’s body) may account for the associations of expeienced weight bias and IWB with poor eating behaviors [6], although no research has yet tested these relationships in bariatric surgery patients.

Additionally, emerging evidence suggests internalized shame (i.e., generalized, global shameabout oneself) may be prevalent in bariatric surgery patients [7] and is associated with negative affectand poor behavioral health [8–10]. Internalized shame develops following adverse interpersonal experiences [11–14] and has been theorized to associate with worse psychiatric outcomes than body shame [15,16]. To our knowledge, only three studies have assessed internalized shame in bariatric surgery populations. Among individuals seeking bariatric surgery, the first study observed elevated internalized shame among women characterized as having probable depression [7], while the second found internalized shame to account for greater variance in anxiety than did body shame after accounting for experienced and internalized weight bias [10]. Two publications drawing from the same study observed pre-surgical internalized shame inversely associated with physical activity one year after surgery, and predictive of maintained psychiatric disorders [8,9].

Given this preliminary evidence, internalized shame may also account for greater variance in weight bias-related emotional eating than body shame. Up to 40% of people seeking bariatric surgery report emotional eating (i.e., eating to soothe negative affect) [17–19], and the related factors of dietary disinhibition [4] and emotion dysregulation [20] have been shown to mediate the links between IWB and binge eating and emotional eating, respectively, in individuals seeking bariatric surgery. Pre-operative emotional eating has been implicated in problematic post-operative eating behaviors, including grazing and snacking [21–24], although its relation to post-operative weight loss remains equivocal (e.g., [25–28]).

Examining protective factors is critical given these harmful sequelae, which can help inform interventions and strategies to support bariatric surgery patients who are vulnerable to weight stigma and its harmful health consequences. Self-compassion (i.e., treating oneself kindly when experiencing emotional pain) is a novel affect regulation protective factor that is linked to less emotional eating and may buffer against the effects of weight stigma [6,29–31] and shame [32] on health. However, it is unknown whether the protective effects of self-compassion extend to emotional eating in this population.

Furthermore, adverse childhood experiences (i.e., childhood trauma, victimization; ACE) share associations with obesity and psychopathology, including affect-related binge eating, in people with extreme obesity [33–35]. ACE may be a confound in weight bias research, although little research has controlled for this factor, and it remains unknown whether weight bias-related sequelae predict emotional eating after accounting for ACE. Additionally, no research has yet examined whether weight bias remains associated with emotional eating after accounting for depressive and anxiety symptoms, despite these factors’ shared ties to both weight bias and emotional eating in bariatric surgery patients [10,19,36,37].

Understanding the risk and protective mechanisms associated with pre-operative emotional eating will shape our understanding of factors contributing to poor behavioral health in bariatric surgery patients. Using a sample of bariatric surgery-seeking patients, the present cross-sectional study examined the following novel research questions: 1) whether experienced weight bias and IWB remain associated with emotional eating after accounting for ACE, 2) whether internalized shame is more strongly associated with emotional eating than body shame after accounting for ACE, experienced weight bias, and IWB, and 3) if self-compassion remains associated with less emotional eating after accounting for all prior modeled factors. Additionally, we examined 4) whether internalized shame accounted for the relationship between IWB and emotional eating, and if greater self-compassion attenuated this association. Last, in a subset of participants for whom both anxiety and depressive symptom data were available, we tested whether findings held after controlling for these factors.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Procedure

Individuals seeking bariatric surgery (N = 229) were recruited for this study as part of a prospective trial from an American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Center of Excellence in Eastern CT from June 2015 to 2019. Patients presenting for all types of bariatric surgery were eligible to participate. Exclusion criteria included (a) those presenting for revisional operations (i.e., operations to revise an earlier surgical weight loss procedure), (b) non-English reading/speaking individuals, and (c) those under age 18. As compensation, participants were provided $10 Amazon gift cards for study participation. Recruitment materials advertised the study as examining “Adverse interpersonal experiences and health in bariatric surgery patients.” Participants were recruited through mailings containing study advertisements, bariatric support group meetings, and information provided by their surgical weight loss medical providers. The study protocol was approved by the Hartford Healthcare and University of Connecticut institutional review boards. A subset of data from this project have been published that examine a different research question [10]. Eligible patients met with IRB-approved study personnel to provide informed consent for research staff to access medical records pertinent to their bariatric surgery work-up; informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Patients were given the option to complete a hard-copy of the survey onsite, or they could complete it at home through a weblink hosted through Qualtrics (Qualtrics International, Inc., Provo, Utah). Of 370 participants confirmed eligible through prescreening, 306 were enrolled in the study and 229 completed the questionnaire, comprising the present sample.

Measures

Demographic indices, objectively-measured body mass index (BMI; kg/m2, extracted from patient medical record at the date closest to the date that surveys were completed), and anxiety and depressive symptom severity assessments were extracted from patients’ medical records. All psychosocial measures were collected via the study survey. See Table 1 for all measures.

Table 1.

Description of survey measures. All measures assessed via online survey with the exception of depressive symptoms, extracted from the patient medical chart.

| Survey description | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Emotional Eating | Three item Emotional Eating subscale of the 18-item Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire-Revised (TFEQ-R18) [53]. On a scale from 1 (definitely false) to 4 (definitely true), participants indicated “When I feel anxious, I find myself eating”; “When I feel blue, I often overeat”; “When I feel lonely, I console myself by eating.” The TFEQ-R18 has been used in a bariatrics surgery sample [54]. Cronbach’s α=0.92. |

| Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) | The ACE Checklist [55] assessed ten categories of childhood maltreatment (yes/no): Emotional, physical, or sexual abuse; emotional or physical neglect; domestic violence; household substance abuse; mental illness in household; parental separation or divorce; or having a criminal household member. The ACE has been used in bariatric surgery samples [56]. Good test-retest reliability (≥0.65) for the ACE checklist is observed in prior research (preferred method for establishing reliability of self-report traumatic experiences) [57]. |

| Experienced Weight Bias | The Stigmatizing Situations Inventory-Brief (SSI-B) [58]. Ten items rated from 1 (never) to 10 (several times per week), assessing physical barriers, relational difficulties, weight-related comments by doctors and children, and assumptions that one binges or has emotional issues because of one’s weight. In the present study, the first 172 participants were administered the original SSI-B Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 9 (several times per week) [58]. The remaining participants (n=57) were administered an 8-item Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 7 (several times per week), a modification used in prior research [59] to avoid relatively low mean values and SDs observed following use of the SSI in a bariatric surgery patient sample [60]. To create a single scale for analysis, anchors for each scale were converted to percentage frequencies on a 0–100 scale and combined into one variable [61]. The SSI-B is strongly associated with the original 50-item SSI [58,60], used previously with bariatric surgery patients [60]. α=0.92. |

| Internalized Weight Bias | The Weight Bias Internalization Scale-Modified (WBIS-M) [62]. A ten-item version was used based on recent research indicating improved reliability including within the bariatric population [63]. Items rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The WBIS-M is highly correlated with the original 11-item WBIS [64], used previously with bariatric surgery patients [20]. α=0.80. |

| Body Shame | Three-item subset from the eight-item Body Shame subscale of the Objectified Body Consciousness Scale (OBCS) [65]. Items were rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The body shame subscale of the OBCS has been widely used in clinical samples [66], although it has not yet been used in samples of bariatric surgery patients. α=0.87. |

| Internalized Shame | The Internalized Shame Scale (ISS) [67]. Twenty-four items rated from 1 (never) to 4 (almost always), excluding the 6 item self-esteem subscale. The ISS has been used with bariatric surgery patients [8,9]. α=0.98. |

| Self-Compassion | The Self-Compassion Scale-Short-Form (SCS-SF) [68]. Items were rated from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The SCS-SF is highly correlated with the original 26-item SCS [69], used previously in samples with overweight and obesity [32]. α=0.85. |

| Anxiety Symptoms 1 | The Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) [70]. Seven items rated from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). The GAD-7 has been used in bariatric surgery patients and demonstrated good internal consistency (α=0.90) [71]. |

| Depressive Symptoms 1 | The Beck Depression Inventory-II [72]. Twenty-one items rated from 0 (e.g., “I do not feel sad”) to 3 (e.g., “I am so sad or unhappy that I can’t stand it”). The BDI-II has been used in bariatric surgery patients and demonstrated good internal consistency (α=0.89) [73]. |

Cronbach’s α unavailable for anxiety/depressive symptom severity assessments due to data extraction procedures, which pulled total scores from patient medical chart. Available n for anxiety (n=206) and depression (n=203) assessments were simultaneously covaried in the secondary analyses; n=196 had both measures in the medical chart and were analyzed.

Analyses

Data were examined for missing values and outliers. All available cases were analyzed using SPSS 25.0. Skewness and kurtosis were within recommended parameters for regression analysis (i.e., skewness < 2.1 and kurtosis < 7.1; 48).

Multiple regressions were used to test whether 1) experienced weight bias and IWB remained associated with emotional eating after accounting for ACE, 2) internalized shame accounted for greater variance in emotional eating than body shame after accounting for all constructs excluding self-compassion, and 3) self-compassion accounted for variance in emotional eating after accounting for all prior modeled constructs. The SPSS PROCESS serial mediation macro, model 6 was used to test whether 4) the effects of IWB on emotional eating were accounted for through indirect effects of internalized shame and self-compassion [39]. This approach employs non-parametric bootstrap resampling procedures to generate estimates of indirect effects interpretable via their significance and magnitude, and does not require the sampling distribution to be normally distributed [38,40]. For each model, 10,000 bootstrap samples were generated to create 95% bias- corrected and accelerated confidence intervals (BCa) to test the significance of indirect effects. Such effects are considered significant at p<.05 if the 95% CI excludes zero. All models controlled for age, BMI, gender, ethnicity, race, insurance status (as a proxy of SES), and ACE. Additionally, following all analyses (multiple regression and serial mediation), analyses were repeated in the subset of participants with both anxiety and depression data available (n=196) to test whether findings held.

Results

Participant sociodemographic and covariate characteristics are reported in Table 2. Survey completers (n=229) did not differ significantly from those enrolled in the study but who did not complete surveys (n=85) on age, gender, or Medicaid status (SES; p>.05). Compared to survey completers, non-completers were more likely to self-identify as Hispanic/Latino/a or Unknown (X2 [2, n=306]=8.10; p=.017) and marginally more likely as BlackAfrican American (X2 [2, n=306]=6.01; p=050).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and covariate (ACE, anxiety and depressive symptom) characteristics

| Characteristics | Valid n | M (SD) or percentage |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| ACE score | 229 | 2.35 (2.1) |

| Age | 229 | 42.28 (11.95) |

| Body Mass Index (BMI; kg/m2) | 229 | 47.64 (8.7) |

| Class I or II (BMI≥30) | 37 | 16.2 |

| Class III (BMI≥40) | 192 | 83.8 |

| Experienced Weight Bias* (SSI-B > 0) | 220 | 96.1 |

| Female | 188 | 82.1 |

| Hispanic/Latino/a | 43 | 18.8 |

| Race | 229 | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 | 1 |

| Asian | 2 | 1 |

| Black or African American | 42 | 18.3 |

| Multiracial | 15 | 6.6 |

| Other/undisclosed | 19 | 8.3 |

| White | 149 | 65.1 |

| Medicaid insurance (SES proxy) | 70 | 30.6 |

| Anxiety symptoms | 196 | 4.07 (4.5) |

| Depressive symptoms | 196 | 8.80 (8.2) |

Note. ACE (Adverse Childhood Experiences), SSI-B (Stigmatizing Situations Inventory-Brief). Age, BMI, ACE, and anxiety and depressive symptoms are mean (standard deviation). All other data are n (%).

at least once in life on average.

Study participants did not differ by gender or race on experienced weight bias, IWB, body shame, internalized shame, or self-compassion on t-tests or ANOVAs (p>.05). Those with Class III obesity reported more experienced weight bias than did those with Classes I/II (mean difference −0.09, t(227)=−2.68, p<.001). Those of Hispanic/Latino/a ethnicity reported lower IWB (mean difference −0.67±0.23, t(227)=−2.91, p=0.004), body shame (mean difference −0.90±0.29, t(227)=−3.07, p=.002), and emotional eating (mean difference −14.23±5.40, t(227)=−2.64, p=.009), and greater self-compassion (mean difference 3.90±1.62, t(227)=2.42, p=.017). Using ANOVA, compared to private insurance, Medicaid coverage was associated with lower IWB (mean difference 0.52±0.03, F(2,226)=3.37, p=−0.036), body shame (mean difference −0.964±0.25, F(2,226)=22.11, p=.001), and emotional eating (mean difference −17.72±4.56, (2,226)=7.64, p=.001).

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations for main study constructs are presented in Table 3; all constructs were significantly associated in hypothesized directions. Age was associated only with Experienced-WB (r=−0.142, p=.035). ACE were associated with experienced weight bias (r=.258, p<.001), IWB (r=.243, p<.001), internalized shame (r=.261, p<.001), body shame (r=.247, p<.001), and lower self-compassion (r=−.185, p=.005). BMI was associated with experienced weight bias (r=.501, p<.001) and internalized shame (r=.142, p=.032).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations for main study variables.

| Measure | EWB | IWB | B-Shame | I-Shame | SC | EE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| EWB | — | |||||

| IWB | 0.383 ** | — | ||||

| B-Shame | 0.395 ** | 0.755 ** | — | |||

| I-Shame | 0.439 ** | 0.730 ** | 0.663 ** | — | ||

| SC | −0.190 * | −0.579 ** | −0.473 ** | −0.672 ** | — | |

| EE | 0.175 * | 0.469 ** | 0.396 ** | 0.445 ** | −0.453 ** | — |

| M | 0.26 1 | 3.85 | 4.85 | 31.91 | 37.90 | 39.98 |

| SD | 0.19 | 1.39 | 1.76 | 24.26 | 9.65 | 32.30 |

| N | 229 | 229 | 229 | 229 | 229 | 229 |

p < .05

p < .01.

Mean percentage frequency on 0–100 scale ranging from never to weekly (Table 2).

EWB (Experienced Weight Bias); IWB (Internalized Weight Bias); B-Shame (Body Shame); I-Shame (Internalized Shame); SC (Self-Compassion); EE (Emotional Eating). Across scales, higher scores are indicative of more extreme responding in the directionality of the measured construct.

Multiple Regression Models

Table 4 presents multiple regression model results characterizing whether 1) experienced weight bias and IWB accounted for variance in emotional eating after controlling for ACE; 2) internalized shame or body shame accounted for greater variance in emotional eating after accounting for covariates, experienced weight bias, and IWB; and 3) self-compassion accounted for variance in emotional eating accounted after all cited antecedent factors in the model. Significant covariates for step one are reported in-text, with remaining steps for the primary analysis presented in Table 4. The overall model accounted for 31.3% of variance in emotional eating (F[12,216]=8.18; p<.001). After accounting for significant covariates in step one (SES and ACE, p=.010 and p=.028, respectively), experienced weight bias accounted for added variance in step two (2.1%, p=.024). With the exception of body shame in step four (0.1%, p=.508), each subsequent construct accounted for added variance in emotional eating, including IWB in step three (15.7%, p<.001), internalized shame in step five (2.2%, p=.010), and self-compassion in step six (2.8%, p=.004).

Table 4.

Regression models reporting unstandardized (B) and standardized beta's (β) and standard errors (SE) for predictors of emotional eating.

| Emotional Eating (outcome) | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Age | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.27 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.27 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.17 | 0.11† |

| BMI | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.05 | −0.15 | 0.29 | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.27 | 0.004 | 0.02 | 0.27 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.26 | −0.003 |

| Ethnicity | 7.31 | 6.22 | 0.09 | 5.69 | 6.20 | 0.07 | −0.96 | 5.73 | −0.01 | −1.19 | 5.75 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 5.69 | 0.001 | −1.57 | 5.62 | −0.02 |

| Race | −6.42 | 4.10 | −0.12 | −7.56 | 4.09 | −0.14† | 7.47 | 3.72 | −0.14* | −7.45 | 3.73 | −0.14* | −7.17 | 3.68 | −0.13† | −6.99 | 3.62 | −0.13† |

| SES (Medicaid status) | −9.87 | 3.82 | −0.18* | −9.15 | 3.79 | −0.17* | −5.59 | 3.49 | −0.10 | −5.28 | 3.53 | −0.10 | −5.21 | 3.48 | −0.10 | −4.87 | 3.42 | −0.09 |

| Sex | −0.57 | 5.61 | −0.01 | −0.77 | 5.55 | −0.01 | 1.38 | 5.07 | 0.02 | 1.15 | 5.08 | 0.01 | 1.83 | 5.03 | 0.02 | 3.04 | 4.96 | 0.04 |

| ACE | 2.20 | 1.00 | 0.15* | 1.55 | 1.03 | 0.10 | 0.36 | 0.95 | 0.02 | 0.30 | 0.96 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.95 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.93 | −0.001 |

| EWB | 30.74 | 13.49 | 0.18* | 3.13 | 12.93 | 0.02 | 1.74 | 13.11 | 0.01 | −4.71 | 13.18 | −0.03 | 2.81 | 13.20 | 0.02 | |||

| IWB | 10.48 | 1.54 | 0.45 | 9.53 | 2.11 | 0.41*** | 6.84 | 2.32 | 0.30** | 5.71 | 2.32 | 0.25* | ||||||

| Body Shame | 1.12 | 1.69 | 0.06 | 0.17 | 1.71 | 0.01 | 0.36 | 1.68 | 0.02 | |||||||||

| Internalized Shame | 0.31 | 0.12 | 0.23* | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.09 | ||||||||||||

| Self-Compassion | −0.79 | 0.27 | −0.24** | |||||||||||||||

| R Squared | 0.08** | 0.10 | 0.26*** | 0.26 | 0.29** | 0.31** | ||||||||||||

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

p < .10.

Note: All VIFs below 2.0.

ACE (Adverse Childhood Experiences); EWB (Experienced Weight Bias); IWB (Internalized Weight Bias).

In the secondary analysis, controlling for anxiety and depressive symptoms in a participant subset, Medicaid status (p=.047) and depressive symptoms (p=.010) were the only predictors of emotional eating in step one (16%, p<.001), EWB no longer accounted for variance in step two (0.5%, p=.241), and internalized shame became marginally significant (step five; 1.5%, p=.052). Remaining findings held. IWB (step three; 12%, p<.001) and self-compassion (step six; 2.6%, p=.008) accounted for significant variance in emotional eating, while body shame (step four; 0.3%, p=.469) remained a non-significant predictor, model R2=.333, F(14,181)=6.45, p<.001.

Serial mediation model testing the indirect effect of IWB on emotional eating

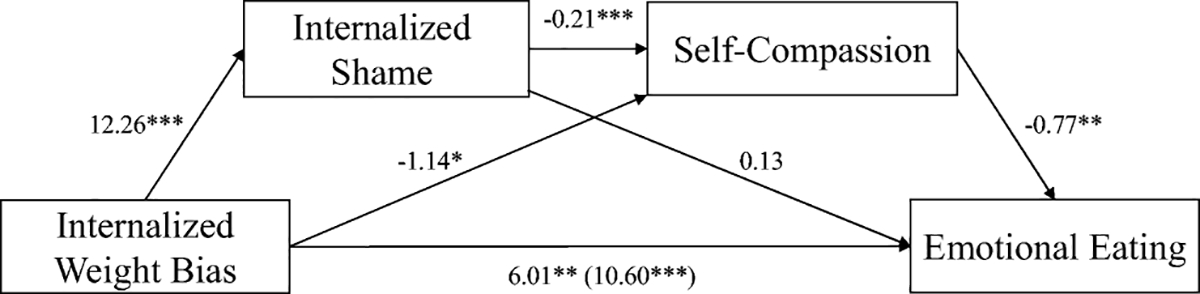

Given the respective non-significant associations of experienced weight bias and body shame with emotional eating after accounting for antecedent factors, we created a more parsimonious mediation model by testing the indirect link of IWB with emotional eating through internalized shame, and then self-compassion. Figure 1 presents the serial mediation model diagram with total effects, significance levels, and unstandardized coefficients for direct paths. Total and individual indirect effects of IWB on emotional eating and model statistics are presented in Table 5. The overall model accounted for 31.5% of the variance in emotional eating. The total effect of IWB on emotional eating was partially attenuated with the addition of mediators to the model. Two paths associated IWB with less emotional eating through greater self-compassion alone, and through greater internalized shame followed by greater self-compassion that in turn associated with less emotional eating. In the final secondary analysis controlling for anxiety and depressive symptoms in a participant subset, only the latter path retained significance (indirect effect B=1.55±0.76, BCa[0.46, 3.55], F(12,183)=7.56, p<..001).

Figure 1.

Emotional eating PROCESS path model summary and unstandardized indirect effects. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Table 5.

Summary of serial mediation model predicting emotional eating (significant paths bolded), controlling for Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) and standard covariates. Unstandardized coefficients reported. Greyed path no longer significant after controlling for anxiety/depressive symptoms in participant subset.

| Outcome | Effect | b (SE) | 95% CI | n | Model R2 | F (df) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Emotional Eating (EE) | Total indirect effect | 4.58 (1.54) | [1.61, 7.70] | 229 | 0.312 | 9.90 (10,218)*** |

| IWB -> int. shame -> EE | 1.67 (1.63) | [−1.64, 4.68] | ||||

| IWB -> int. shame -> self-compassion -> EE | 2.03 (0.88) | [0.63, 4.15] | ||||

| IWB -> self-compassion -> EE | 0.88 (0.54) | [0.04, 2.28] | ||||

p < .001. IWB (Internalized Weight Bias); Int. Shame (Internalized Shame); Emotional Eating (EE).

Discussion

The present study implicates internalized weight bias (IWB) and internalized shame as together accounting for significant variance in emotional eating among individuals seeking bariatric surgery, and suggests that self-compassion may confer some protection against these factors. Although experienced weight bias remained associated with emotional eating after accounting for adverse childhood experiences (ACE), it was no longer significant after adjusting for depressive and anxiety symptoms, consistent with evidence that both ACE and experienced weight stigma may indirectly contribute to emotional eating. This finding also aligns with prior work suggesting that internalization of weight bias has stronger and more direct implications for behavioral and physical health, including emotional eating, than the extent of stigma a person has experienced [5]. Experienced weight bias and ACE are external experiences, whereas IWB, shame, and self-compassion comprise internal appraisals of these experiences that may more proximally impact health. Indeed, a strong theoretical rationale indirectly links experienced weight bias to emotional eating via IWB and intervening mechanisms [6].

Internalized shame was a stronger predictor of emotional eating than body shame, after accounting for all other modeled factors other than self-compassion, aligning with evidence implicating internalized shame as a mechanism underlying the maintenance of eating pathology [41]. Yet, this finding was only marginal after controlling for depressive/anxiety symptoms. These findings support continued research to better understand whether, for whom, and under what conditions internalized shame may contribute to poor post-operative eating behaviors among subsets of patients [21–24].

Moreover, IWB remained associated with emotional eating after accounting for covariates, internalized shame and self-compassion, as well as anxiety and depressive symptoms, underscoring the need for more research to elucidate the proximal risk and protective mechanisms of its effects. For instance, some evidence suggests IWB may disrupt intuitive eating (i.e., eating based on endogenous hunger and satiety mechanisms) [42], which has been conceived as a protective strategy against unhealthy dieting, eating pathology, and weight gain [43]. IWB has been indirectly linked to lower intuitive eating through less self-compassion in prior research [44], although these relationships have not yet been examined in bariatric surgery patients, an interesting direction for future research.

Self-compassion remained negatively associated with emotional eating after accounting for all other factors, supporting evidence that this factor may protect against associations between stigma, shame, negative affect, and eating to cope with negative affect (i.e., disordered eating, which frequently includes an element of emotional eating) [26,27]. This finding is also consistent with recent research in adults with obesity that showed gains in self-compassion to mediate reductions in emotional eating during a healthy lifestyle intervention [29].

Interestingly, mediation analyses revealed that IWB was not associated with emotional eating through internalized shame alone. Instead, people who reported IWB accompanied by internalized shame and self-compassion indicated lower emotional eating. Self-compassion’s proximal associations with emotional eating implicate it as a key intervention target. Consistent with prior findings that affect dysregulation mediates the link between IWB and emotional eating in patients seeking bariatric surgery [20], self-compassion is an adaptive affect regulation strategy that can protect against myriad forms of negative affect, including those originating from both external (e.g., experienced discrimination) and internal-external (e.g., shame) sources [45–47].

Furthermore, these findings suggest the hypothesis that self-compassion may offer some protection against the association between IWB-related psychiatric symptoms and emotional eating, as well as other risk behaviors that serve an affect regulation function in this population post-operatively, such as alcohol misuse and self-harm. This may be particularly the case given our finding that self-compassion remained a significant predictor after accounting for anxiety and depressive symptoms in a participant subset. Importantly, due to the cross-sectional design, our findings can also be interpreted as low self-compassion facilitating the links between IWB, internalized shame, and emotional eating – a conceptualization that implicates low self-compassion as a potential risk factor and target for intervention.

Several limitations of the study should be noted. First, cross-sectional mediation models should be viewed as an exploratory method to test possible causal mechanisms prior to designing resource-intensive longitudinal and/or intervention studies. While causality cannot be inferred from such studies, analyses can confirm whether a given causal chain is possible [39]. As such, the directionality of the observed findings remains to be empirically verified because these analyses do not draw from longitudinal data and the temporal ordering of variables has not been causally demonstrated [48,49]. Nonetheless, we intentionally modeled the theorized constructs based on prior theory and quantitative and qualitative research that implicates a) increased shame as a consequence of internalizing weight bias [6,31,50], and b) self-compassion as protective against the effects of stigma and shame [30,32,51]. Yet, it is equally plausible that greater internalized shame may predict increased likelihood of internalizing weight bias over time and/or that self-compassion could confer protection against both factors. Indeed, low self-compassion could prove an exogenous risk factor for internalizing both weight bias and shame. Future longitudinal studies are needed to examine the temporal ordering of the internalized weight bias-emotional eating relationship and potential mediators and moderators of this association across time so that the causal process by which weight bias is internalized and affects emotional eating behavior may be elucidated.

Additionally, we assessed self-reported emotional eating, the validity of which is uncertain [52]. Future work would benefit from more objective and ecologically valid assessments of eating behavior, such as Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA). We also utilized a subset of items from the Body Shame subscale of the OBCS, potentially excluding key variance from this construct. A complete body shame measure should be utilized in future research. Additionally, generalizability of the sample is limited due to our recruitment of those with “adverse interpersonal experiences.” Finally, it will be important for future work to replicate study findings in samples with greater gender and racial/ethnic diversity. Despite these limitations, our study offers novel insights on previously unstudied relationships between weight stigma and emotional eating in individuals seeking bariatric surgery, with important implications for the role of self-compassion in understanding health behaviors and informing therapeutic interventions with this population.

Conclusion

Moving beyond previous evidence of an association between IWB and emotional eating in bariatric surgery patients, our findings in individuals seeking bariatric surgery suggest that this association may be partially facilitated through internalized shame and interrupted through greater self-compassion. Further, these associations persist after controlling for the effects of adverse childhood experiences (ACE), a common contributor to poor eating behaviors, as well as depressive symptoms in a subset of participants. Given implications of emotional eating for post-operative grazing, surgical complications secondary to dietary non-compliance, and weight regain, continued research utilizing longitudinal designs is warranted to better understand the role of IWB, internalized shame, and self-compassion in relation to these sequelae.

While our findings implicate self-compassion as a protective factor and/or intervention target that may disrupt the effects of IWB and shame, research is needed to determine the feasibility and effectiveness of self-compassion-based training programs in this population. Additionally, given the strong direct effect of IWB on emotional eating in our sample of bariatric surgery-seeking patients after accounting for shame and self-compassion, continued research on other potential risk/protective factors remains an important focus. Moreover, individually-focused interventions need to be accompanied by structural- and interpersonal-level efforts to reduce weight-based prejudice towards persons with overweight and obesity, the source of IWB and related sequelae.

Key Points:

Weight bias (WB), shame, & self-compassion associate with emotional eating

Indirect effect of internalized WB on emotional eating via shame, self-compassion

Most findings held after accounting for adverse childhood experiences & distress

Funding:

This work was supported through a National Institutes of Health Cardiovascular Behavioral and Preventive Medicine Training Grant awarded to the Miriam Hospital, Providence, RI (T32 HL076134).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: Dr. Braun, Dr. Gorin, Dr. Puhl, Ms. Stone, Dr. Quinn, Dr. Ferrand, Dr. Abrantes, Dr. Unick, and Dr. Papasavas report no conflict of interest. Dr. Tishler reports personal fees from Medtronic, personal fees from Olympus, personal fees from Conmed, outside the submitted work.

COI Statement:

Dr. Braun has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Gorin has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Puhl has nothing to disclose.

Ms. Stone has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Quinn has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Ferrand has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Abrantes has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Unick has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Tishler reports personal fees from Medtronic, personal fees from Olympus, personal fees from Conmed, outside the submitted work

Dr. Papasavas has nothing to disclose.

Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Lent MR, Napolitano MA, Wood GC, Argyropoulos G, Gerhard GS, Hayes S, et al. Internalized weight bias in weight-loss surgery patients: Psychosocial correlates and weight loss outcomes. Obes Surg. 2014;24:2195–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raves DM, Brewis A, Trainer S, Han SY, Wutich A. Bariatric surgery patients’ perceptions of weight-related stigma in healthcare settings impair post-surgery dietary adherence. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feig EH, Amonoo HL, Onyeaka HK, Romero PM, Kim S, Huffman JC. Weight bias internalization and its association with health behaviour adherence after bariatric surgery. Clin Obes. 2020;1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soulliard ZA, Brode C, Tabone LE, Szoka N, Abunnaja S, Cox S. Disinhibition and subjective hunger as mediators between weight bias internalization and binge eating among pre-surgical bariatric patients. Obes Surg. Obesity Surgery; 2020;797–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearl RL, Puhl RM. Weight bias internalization and health: A systematic review. Obes Rev. 2018;19:1141–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tylka TL, Annunziato RA, Burgard D, Danielsdottir S, Shuman E, Davis C, et al. The weight inclusive versus the weight normative approach to health: Evaluating the evidence for prioritising wellbeing over weight loss. J Obes. 2014;18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ivezaj V, Barnes RD, Grilo CM. Validity and clinical utility of subtyping by the Beck Depression Inventory in women seeking gastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg. 2016;26:2068–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lier H∅, Biringer E, Bjørkvik J, Rosenvinge JH, Stubhaug B, Tangen T. Shame, psychiatric disorders and health promoting life style after bariatric surgery. Obes Weight Loss Ther. 2011;2:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lier H∅, Biringer E, Stubhaug B, Tangen T. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders before and 1 year after bariatric surgery: The role of shame in maintenance of psychiatric disorders in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Nord J Psychiatry. 2012;67:89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braun TD, Quinn DM, Stone A, Gorin AA, Ferrand J, Puhl RM, et al. Weight bias, shame, and self-compassion: Risk/protective mechanisms of depression and anxiety in prebariatric surgery patients. Obesity. 2020;28:1974–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 11.Webb M, Heisler D, Call S, Chickering SA, Colburn TA. Shame, guilt, symptoms of depression, and reported history of psychological maltreatment. Child Abus Negl. 2007;31:1143–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Claesson K, Sohlberg S. Internalized shame and early interactions characterized by indifference, abandonment and rejection: Replicated findings. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2002;9:277–84. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy B, Celen-Demirtas S, Surguladze T, Sweeney KK. Stigma and discrimination: A sociocultural etiology of mental illness. Humanist Psychol. 2014;42:199–214. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stuewig J, McCloskey LA. The relation of child maltreatment to shame and guilt among adolescents: Psychological routes to depression and delinquency. Child Maltreat. 2005;10:324–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goss K, Gilbert P. Eating disorders, shame, and pride: A cognitive-behavioural functional analysis. In: Gilbert P, Miles J, editors. Body Shame. New York, NY: Routledge; 2007. p. 219–55. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilbert P Body shame: A biopsychosocial conceptualisation and overview with treatment implications. In: Gilbert P, Miles J, editors. Body Shame. New York, NY: Routledge; 2007. p. 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitchell JE, Crosby R, De Zwaan M, Engel S, Roerig J. Possible risk factors for increased suicide following bariatric surgery. Obesity. 2013;21:665–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guerdjikova AI, West-Smith L, McElroy SL, Sonnanstine T, Stanford K, Keck Jr. PE. Emotional eating and emotional eating alternatives in subjects undergoing bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2007;17:1091–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walfish S Self-assessed emotional factors contributing to increased weight gain in pre-surgical bariatric patients. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1402–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baldofski S, Rudolph A, Tigges W, Herbig B, Jurowich C, Kaiser S, et al. Weight bias internalization, emotion dysregulation, and non-normative eating behaviors in prebariatric patients. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;49:744–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saunders R “Grazing”: A high-risk behavior. Obes Surg. 2004;14:98–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colles SL, Dixon JB, O’Brien PE. Grazing and loss of control related to eating: Two high-risk factors following bariatric surgery. Obesity. 2008;16:615–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poole NA, Atar A Al, Kuhanendran D, Bidlake L, Fiennes A, McCluskey S, et al. Compliance with surgical after-care following bariatric surgery for morbid obesity: A retrospective study. Obes Surg. 2005;15:261–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rusch MD, Andris D. Maladaptive eating patterns after weight-loss surgery. Nutr Clin Pract. 2007;22:41–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wedin S, Madan A, Correll J, Crowley N, Malcolm R, Byrne TK, et al. Emotional eating, marital status and history of physical abuse predict 2-year weight loss in weight loss surgery patients. Eat Behav. 2014;15:619–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Busetto L, Segato G, De Marchi F, Foletto M, De Luca M, Caniato D, et al. Outcome predictors in morbidly obese recipients of an adjustable gastric band. Obes Surg. 2002;12:83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canetti L, Berry EM, Elizur Y. Psychosocial predictors of weight loss and psychological adjustment following bariatric surgery and a weight-loss program: The mediating role of emotional eating. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:109–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chesler BE. Emotional eating: A virtually untreated risk factor for outcome following bariatric surgery. Sci World J. 2012;2012:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palmeira L, Cunha M, Pinto-Gouveia J. Processes of change in quality of life, weight self-stigma, body mass index and emotional eating after an acceptance-, mindfulness- and compassion-based group intervention (Kg-Free) for women with overweight and obesity. J Health Psychol. 2017;24:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong CCY, Knee CR, Neighbors C, Zvolensky MJ. Hacking stigma by loving yourself: A mediated-moderation model of self-compassion and stigma. Mindfulness (N Y). Mindfulness; 2019;10:415–33. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salas XR, Forhan M, Caulfield T, Sharma AM, Raine KD. Addressing internalized weight bias and changing damaged social identities for people living with obesity. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braun TD, Park CL, Gorin A. Self-compassion, body image, and disordered eating: A review of the literature. Body Image. 2016;17:117–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brewerton TD, Neil PMO, Dansky BS, Kilpatrick DG. Extreme obesity and its associations with victimization, PTSD, Major Depression and eating disorders in a national sample of women. J Obes Eat Disord. 2015;1:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fuemmeler BF, Dedert E, McClernon JF, Beckham JC. Adverse childhood events are associated with obesity and disordered eating: Results from a U.S. population-based survey of young adults. J Trauma Stress. 2010;22:329–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palmisano GL, Innamorati M, Vanderlinden J. Life adverse experiences in relation with obesity and binge eating disorder: A systematic review. J Behav Addict. 2016;5:11–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenberger PH, Henderson KE, Bell RL, Grilo CM. Associations of weight-based teasing history and current eating disorder features and psychological functioning in bariatric surgery patients. Obes Surg. 2007;17:470–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geller S, Levy S, Goldzweig G, Hamdan S, Manor A, Dahan S, et al. Psychological distress among bariatric surgery candidates: The roles of body image and emotional eating. Clin Obes. 2019;9:e12298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.West SG, Finch JF, Curran PJ. Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Struct Equ Model Concepts, Issues Appl. Newbery Park, CA: Sage; 1995. p. 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40:879–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chao YH, Yang CC, Chiou W Bin. Food as ego-protective remedy for people experiencing shame. Experimental evidence for a new perspective on weight-related shame. Appetite. Elsevier Ltd; 2012;59:570–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mensinger JL, Calogero RM, Tylka TL. Internalized weight stigma moderates eating behavior outcomes in women with high BMI participating in a healthy living program. Appetite. Elsevier Ltd; 2016;102:32–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bruce LJ, Ricciardelli LA. A systematic review of the psychosocial correlates of intuitive eating among adult women. Appetite. Elsevier Ltd; 2016;96:454–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schoenefeld SJ, Webb JB. Self-compassion and intuitive eating in college women: Examining the contributions of distress tolerance and body image acceptance and action. Eat Behav. Elsevier Ltd; 2013;14:493–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Finlay-Jones AL. The relevance of self-compassion as an intervention target in mood and anxiety disorders: A narrative review based on an emotion regulation framework. Clin Psychol. 2017;21:90–103. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trompetter HR, de Kleine E, Bohlmeijer ET. Why does positive mental health buffer against psychopathology? An exploratory study on self-compassion as a resilience mechanism and adaptive emotion regulation strategy. Cognit Ther Res. Springer US; 2017;41:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson EA, O’Brien KA. Self-compassion soothes the savage ego-threat system: Effects on negative affect, shame, rumination, and depressive symptoms. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2013;32:939–63. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Judd CM, Kenny DA. Process analysis: Estimating mediation in treatment evaluations. Eval Rev. 1981;5:602–19. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mensinger JL, Tylka TL, Calamari ME. Mechanisms underlying weight status and healthcare avoidance in women: A study of weight stigma, body-related shame and guilt, and healthcare stress. Body Image. Elsevier Ltd; 2018;25:139–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vigna AJ, Poehlmann-Tynan J, Koenig BW. Is self-compassion protective among sexual- and gender-minority adolescents across racial groups? Mindfulness (N Y). 2020;11:800–15. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bongers P, Jansen A. Emotional eating is not what you think it is and emotional eating scales do not measure what you think they measure. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anglé S, Engblom J, Eriksson T, Kautiainen S, Saha M-T, Lindfors P, et al. Three Factor Eating Questionnaire-R18 as a measure of cognitive restraint, uncontrolled eating and emotional eating in a sample of young Finnish females. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2009;6:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pratt KJ, Balk EK, Ferriby M, Wallace L, Noria S, Needleman B. Bariatric surgery candidates’ peer and romantic relationships and associations with health behaviors. Obes Surg [Internet]. Obesity Surgery; 2016;26:2764–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dong M, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Williamson DF, Thompson TJ, et al. The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abus Negl. 2004;28:771–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lodhia NA, Rosas US, Moore M, Glaseroff A, Azagury D, Rivas H, et al. Do adverse childhood experiences affect surgical weight loss outcomes? J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:993–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pinto R, Correia L, Maia Â. Assessing the reliability of retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences among adolescents with documented childhood maltreatmen. J Fam Violence. 2014;29:431–8. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vartanian LR. Development and validation of a brief version of the Stigmatizing Situations Inventory. Obes Sci Pract. 2015;1:119–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sattler KM, Deane FP, Tapsell L, Kelly PJ. Gender differences in the relationship of weight- based stigmatisation with motivation to exercise and physical activity in overweight individuals. Heal Psychol Open. 2018;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Myers A, Rosen JC. Obesity stigmatization and coping: Relation to mental health symptoms, body image, and self-esteem. Int J Obes. 1999;23:221–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cohen P, Cohen J, Aiken LS, West SG. The problem of units and the circumstance for POMP. Multivariate Behav Res. 1999;34:315–46. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pearl RL, Puhl RM. Measuring internalized weight attitudes across body weight categories: Validation of the modified weight bias internalization scale. Body Image. Elsevier Ltd; 2014;11:89–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hübner C, Baldofski S, Zenger M, Tigges W, Herbig B, Jurowich C, et al. Influences of general self-efficacy and weight bias internalization on physical activity in bariatric surgery candidates. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11:1371–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Durso LE, Latner JD. Understanding self-directed stigma: Development of the Weight Bias Internalization Scale. Obesity. 2008;16 Suppl 2:S80–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McKinley NM, Hyde JS. The Objectified Body Consciousness Scale: Development and validation. Psychol Women Q. 1996;20:181–215. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dakanalis A, Timko AC, Clerici M, Riva G, Carrà G. Objectified Body Consciousness (OBC) in eating psychopathology: Construct validity, reliability, and measurement invariance of the 24-Item OBC Scale in clinical and nonclinical adolescent samples. Assessment. 2017;24:252–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cook DR. Measuring shame: The Internalized Shame Scale. Alcohol Treat Q. Taylor & Francis Group; 1988;4:197–215. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Raes F, Pommier E, Neff KD, Van Gucht D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2011;18:250–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity. 2003;2:223–50. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.de Zwaan M, Georgiadou E, Stroh CE, Teufel M, Köhler H, Tengler M, et al. Body image and quality of life in patients with and without body contouring surgery following bariatric surgery: A comparison of pre- and post-surgery groups. Front Psychol. 2014;5:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1996;67:588–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hayden MJ, Brown WA, Brennan L, O’Brien PE. Validity of the Beck Depression Inventory as a screening tool for a clinical mood disorder in bariatric surgery candidates. Obes Surg. Springer-Verlag; 2018;22:1666–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]