SYNOPSIS

Objective

Drawing on existing literature concerning the interrelations among toddler fearful temperament, maternal protective parenting, and maternal cognitions, the current study sought to test how mothers’ abilities to predict their children’s distress expressions and behaviors in future novel situations (“maternal accuracy”), may be maintained from toddlerhood to children’s kindergarten year.

Design

A sample of 93 mother-child dyads completed laboratory assessments at child age 2 and were invited back for two laboratory visits during children’s kindergarten year. Fearful temperament, age 2 maternal accuracy, and protective behavior were measured observationally at age 2, and children’s social withdrawal and kindergarten maternal accuracy were measured observationally at the follow-up kindergarten visits.

Results

We tested a moderated serial mediation model. For highly fearful children only, maternal accuracy may be maintained because it relates to protective parenting, which predicts children’s social withdrawal, which feeds back into maternal accuracy.

Conclusions

Maternal accuracy may be maintained across early childhood through the interactions mothers have with their temperamentally fearful children. Given concurrent measurement of some of the variables, the role of maternal cognitions like maternal accuracy should be replicated and then further considered for inclusion in theories and studies of transactional influences between parents and children on development.

Keywords: mother-child relationships, social withdrawal, temperament

INTRODUCTION

Maternal accuracy for their children’s distress responses to novelty captures mothers’ abilities to anticipate their children’s negative, withdrawn responses to new, uncertain situations (Kiel & Buss, 2006). Although similar constructs (e.g., insightfulness, mind-mindedness) are generally associated with children’s positive socioemotional outcomes (Koren-Karie, Oppenheim, Dolev, Sher, & Etzion-Carasso, 2002; McMahon, & Bernier, 2017; Meins, Ferryhough, Fradley, & Tuckey, 2001), accuracy for children’s distress to novelty may operate differently for children exhibiting high, rather than low, levels of fearful temperament (Kiel & Buss, 2010, 2011). Mothers who accurately anticipate that their children will respond with fear in new situations may respond with protective and overly warm parenting to alleviate immediate distress, although these parenting behaviors predict children’s risk for future anxiety (Kiel & Buss, 2011; Kiel & Buss, 2012). Despite the importance of maternal accuracy for children’s distress to novelty for the development of anxiety spectrum problems in fearful children, no research has investigated maternal accuracy longitudinally. Furthermore, maternal cognitions, such as accuracy for children’s distress to novelty, are best understood in the context of dynamic interactions within the parent-child dyad. In this vein, the current study examined whether maternal accuracy in toddlerhood predicts maternal accuracy 3 years later. We examined a moderated mediation model that accounts for protective parenting and children’s social withdrawal as mechanisms contributing to accuracy for children’s distress to novelty, with toddler fearful temperament as a moderator.

Maternal Accuracy for Children’s Distress to Novelty and Fearful Temperament

It is crucial to understand maternal accuracy for children’s distress to novelty in the context of children’s temperament. Fearful (also, inhibited) temperament refers to children’s dispositional and biologically rooted tendencies to react to novelty with fear and distress; fearful temperament places children at increased risk for anxiety spectrum problems throughout the lifespan (Fox, Henderson, Marshall, Nichols, & Ghera, 2005; Kagan, Reznick, Clark, Snidman, & Garcia-Coll, 1984; Rubin, Coplan, & Bowker, 2009). For fearful children, parenting behaviors that allow avoidance and promote withdrawal may increase the likelihood that children will continue to respond with avoidance to future novel experiences (Kiel, Premo, & Buss, 2016; Laurin, Joussement, Tremblay, & Boivin, 2015; Rubin, Hastings, Stewart, Henderson, & Chen, 1997). Such avoidance-promoting parenting behaviors, although potentially well-intentioned, are generally referred to as protective parenting behaviors (also, oversolicitous parenting) and include those behaviors that shield and protect children from new and developmentally appropriate situations while simultaneously providing extensive comfort (Rubin, Burgess, & Hastings, 2002).

Maternal accuracy for children’s distress to novelty may prime these protective parenting behaviors for mothers of temperamentally fearful children. That is, mothers who can accurately predict their children’s fear responses may respond with protective and comforting behaviors to limit their children’s distress in that moment (Kiel & Buss, 2011, 2012). Although mothers who are attuned to their young children’s internal states can respond in a more contingent and sensitive manner (Krink, Muehlhan, Luyten, Romer, & Ramsauer, 2018; Rutherford, Booth, Luyten, Bridgett, & Mayes, 2015), which is generally associated with positive socioemotional development in non-fearful children (Brophy-Herb et al., 2011; Chen, McElwain, Berry & Emery, 2019; Davidov & Grusec, 2006; Spinrad, Stifter, Donelan-McCall, & Turner, 2004), increased accuracy for distress to novelty may be maladaptive for temperamentally fearful children when it contextualizes protective parenting that inadvertently limits their children’s opportunities to develop independent self-regulation skills. Such parenting behaviors could result from particular maternal cognitions about their children’s fearfulness (e.g., fear is inappropriate or embarrassing) or maternal anxiety. However, the relation between accuracy for children’s distress to novelty and parenting is likely also influenced by children’s fearfulness itself.

Children’s Elicitation of Protective Parenting

It is increasingly understood that parent-child interactions are reciprocal. That is, in addition to parenting shaping children’s outcomes, children influence the parenting that they receive by eliciting specific parenting behaviors. Theoretical models, empirical studies, and reviews show that child temperament and parenting behaviors dynamically influence each other (e.g., Bell, 1979; Gallagher, 2002; Kiff, Lengua, & Zalewski, 2011; Klein et al., 2018; Putnam, Sanson, Rothbart, 2002). When considering the emergence of child anxiety specifically, theory suggests that anxiety is exacerbated and maintained in children who display more fearful temperament because they elicit protective parenting responses. These protective parenting behaviors then serve to reduce children’s fear response in the moment, reinforcing both children’s continued reliance on the parent and the parent’s continued engagement in protection (Dadds & Roth, 2001). Indeed, multiple examinations reveal that temperamentally fearful children receive more protective parenting behaviors than less fearful children (Bayer, Sanson, & Hemphill, 2006; Kiel, Premo, & Buss, 2016; Shamir-Essakow, Ungerer, Rapee, & Safier, 2004) and that children’s fear, inhibition, and anxious symptoms predict overprotective parenting behaviors over time (Edwards, Rapee, & Kennedy, 2010; Gouze, Hopkins, Bryant, & Lavigne, 2016).

Maternal accuracy for children’s distress to novelty may play a crucial role in determining whether children successfully elicit protective parenting. In a previous study using the same sample on which we currently focus (Kiel & Buss, 2010), maternal accuracy for children’s distress to novelty interacted with fearful temperament in relation to protective parenting behavior. Specifically, only at high levels of maternal accuracy was there a positive association between fearful temperament and solicited protective parenting; no relation existed at average or low levels of maternal accuracy (Kiel & Buss, 2010). Furthermore, there was not a significant association between fearful temperament and mothers’ spontaneous protective behaviors. This pattern of findings suggests that it is the accurate anticipation of fearfulness in novel situations that facilitates child-elicited protective behavior. Additionally, child-elicited protective parenting (but not unsolicited protective behavior) in toddlerhood indirectly links early toddler fearfulness to maternal protective parenting at kindergarten entry, again only when mothers displayed high degrees of accuracy (Kiel & Buss, 2011). Theory and empirical work therefore suggest that maternal accuracy for children’s distress to novelty uniquely confers risk for children high in fearful temperament, as accuracy may promote more protective parenting responses that maintain children’s withdrawal and risk for anxiety over time. Understanding how maternal accuracy is maintained from toddlerhood to kindergarten entry may point to targeted ways to intervene by reshaping the consequences of maternal accuracy and disrupting dynamic parent-child interactions that maintain children’s anxiety risk.

Maintenance of Maternal Accuracy

Given that children can influence the parenting they receive, it seems probable that their fearful behaviors may also determine whether maternal accuracy for children’s distress to novelty is maintained across childhood. Although it is known that temperamental fear elicits protective parenting behaviors that maintain children’s anxiety risk over time (Dadds & Roth, 2001; Edwards et al., 2010), how the dynamic relation among fearful temperament and parenting relates to subsequent maternal accuracy remains unknown. Perhaps when mothers respond to their inhibited children’s fear displays with protection, protective behaviors serve to maintain children’s fear and withdrawal, which then reinforce mothers’ beliefs that their children are inhibited and fearful. Although the maintenance of maternal beliefs through parenting and children’s behavior has not been studied directly, evidence exists that both maternal characteristics and toddler temperament relate to mothers’ parenting beliefs (Grady & Karraker, 2017). Parents of fearful children report engaging in more protective behaviors, even when controlling for children’s actual behaviors (Hastings & Rubin, 1999). Therefore, accurate parents may fall into a pattern in which they regularly anticipate fear displays and respond proactively with protection, even when the protection is not contingent on children’s actual fearful behavior. Longitudinal investigations are necessary to examine the parenting and child mechanisms that influence the stability of accuracy across time.

The Current Study

The current study is a longitudinal follow-up to a previous study of maternal accuracy for children’s distress to novelty, fearful temperament, and protective parenting, which predicted children’s anxiety risk in toddlerhood (Kiel & Buss, 2010). The previous study established an interaction between fearful temperament and maternal accuracy in relation to protective parenting, which predicted toddlers’ anxious behaviors 1 year later. Because this previous study focused on the role of maternal accuracy for children’s distress to novelty and protective parenting in the link from fearful temperament to children’s outcomes, fearful temperament was conceptualized as the predictor and maternal accuracy as the moderator. Child and parent characteristics are theoretically acknowledged to be mutually influential (Dadds & Roth, 2001; Sameroff, 2010) and therefore would be expected to act in different roles depending if parent or child outcomes are being studied. Examples of interchanging roles arise from empirical studies of child temperament and parent characteristics and behavior, which sometimes assign temperament as the predictor and the parent variable as the moderator, and sometimes assign the parent variable as the predictor and temperament as the moderator (e.g., Degnan & Fox, 2007; Degnan et al., 2008; Hastings & Rubin, 1999; Rubin et al., 2002). Because we currently focus on potential mechanisms of a maternal outcome, we conceptualized maternal accuracy (during toddlerhood) as the predictor and fearful temperament as the moderator in their interaction. Based on the known positive value of this interaction term, we expected that maternal accuracy in toddlerhood would be increasingly strongly associated with maternal protective behavior as toddler fearful temperament increased. Using the previous analysis of the interaction between fearful temperament and maternal accuracy for children’s distress to novelty in relation to protective parenting as a foundation, the current study extends this work to understand the link between maternal accuracy for children’s distress to novelty in toddlerhood and later maternal accuracy at children’s kindergarten entry.

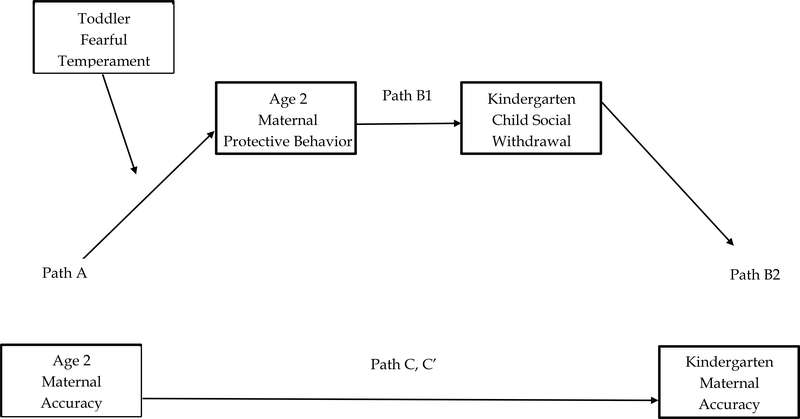

Children’s social withdrawal and maternal accuracy were longitudinally assessed at children’s kindergarten entry due to work suggesting the role of parenting behaviors at the transition to formal schooling (Nathanson, Rimm-Kaufman, & Brock, 2009) and the established implications of elementary school adjustment for long-term academic and socioemotional trajectories (e.g., Gregory & Rimm-Kaufman, 2008; Grover, Ginsburg, & Jalongo, 2007). Kindergarten entry can be a stressful time for parents of anxiety-prone children (Hiebert-Murphy et al., 2011), which may prime their attunement to their children’s distress. The current study hypothesized that accuracy in toddlerhood (at child age 2 years) would relate indirectly to accuracy at children’s kindergarten entry through protective parenting and subsequent child social withdrawal, specifically for children who were high in fearful temperament as toddlers. See Figure 1 for a conceptual model. The results of the current investigation have the potential to reveal the mechanisms underlying accuracy’s maintenance over time and ultimately inform parenting interventions to reduce the longitudinal risk for anxiety development in early childhood.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of a moderated serial mediation linking maternal accuracy between child age 2 and kindergarten.

METHOD

Participants

Participants included 93 mother-toddler dyads who were recruited through locally published birth announcements and participated in a larger longitudinal study of toddler temperament (Buss, 2011; Kiel & Buss, 2010). Inclusion criteria included the toddler being between 23 and 25 months of age and the mother being able to communicate in English. Exclusion criteria included parent-reported developmental delays. Toddlers (42 female) were approximately 2 years of age (M = 24.03 months, SD = 0.42 months) for the first assessment. According to mothers, 85 toddlers (91.4%) were European American, 3 (3.2%) were African American, 2 (2.2%) were Asian American, 1 (1.1%) was American Indian, and 1 (1.1%) was Latin American; 1 mother (1.1%) did not report her child’s ethnicity. The average level of maternal education was a college degree (years of education: M = 16.24, SD = 2.33, Range = 12 to 20+). According to the Hollingshead Four-Factor Index of socioeconomic status (SES), families were, on average, middle class, although a wide range of SES was represented (M = 47.57, SD = 11.86, Range = 13.00 to 66.00). Seventy-two families (77%) participated in a longitudinal follow-up during children’s kindergarten year (child age: M = 6.26 years, SD = 0.30 years). Of these families, 64 families (69% of the original sample) provided longitudinal data relevant to the current study.

Procedures

Upon expressing interest in participating in the study with her toddler, the mother made an appointment for a 2-hour laboratory visit. A primary experimenter (E1) acclimated the mother and toddler, collected written consent, and explained procedures. E1 described the standardized tasks in which the toddler would engage with the mother present. Each of these tasks presented novel objects or people and was designed based on procedures elsewhere in the literature (Buss & Goldsmith, 2000; Nachmias, Gunnar, Mangelsdorf, Parritz, & Buss, 1996).

A Risk Room procedure served as the assessment of fearful temperament. E1 brought the toddler and mother to a room containing five activities that each required an element of risk-taking (expandable tunnel, trampoline, low balance beam, “scary” box, and gorilla mask on a pedestal). E1 told the toddler to play “however you like” for 3 min and instructed the mother to limit spontaneous interactions before leaving the room. E1 then returned and asked the child to engage with each of the activities in a standardized order (i.e., crawl through the tunnel, jump on the trampoline, walk across the balance beam, put a hand inside the cut-out mouth of the scary box, and touch the gorilla mask) with up to three friendly prompts. E1 moved on to the next activity either when the child completed the activity or after the three prompts.

Six novelty episodes were used to assess maternal accuracy for children’s distress to novelty and protective parenting. After describing each task, E1 asked the mother to make several predictions, which are described in further detail in the Measures. In the Clown episode, a secondary experimenter (E2) came into the room, dressed in a clown costume, colorful wig, and red nose. In a friendly tone, she invited the child to play three games (blowing bubbles, catch with beach balls, musical instruments), each lasting approximately 1 min. After the final game, she asked the child to help her pick up her toys, and then she said goodbye and left the room. In Puppet Show, E2 sat behind a small wooden stage with curtain. When the mother and toddler entered the room, she controlled two hand puppets, who introduced themselves and then invited the child to play catch and then a fishing game. Finally, the puppets presented the child with a sticker. E2 then came out from behind the stage and offered the toddler the chance to touch the puppets. In Stranger Approach, the child began the episode by being able to play with a few small toys. After 30 sec, an unfamiliar male adult entered the room and, according to a standardized script, introduced himself and asked the child several simple questions (e.g., “What’s your name?”), pausing after each one to allow the child to respond. After approximately 1 min, the stranger excused himself and left the room. In the Stranger Working episode, the child again started the episode by playing with a few small toys. After 30 sec, E2 entered the room, sat in a desk in the corner of the room, and pretended to work. She did not speak to the child unless the child first spoke to her or approached her very closely. After 2 min, she left the room. In the Robot episode, the mother sat with the child on her lap in one corner of the room, and in the other corner resided a remote-controlled robot. E2 controlled the robot from behind a one-way mirror so that it moved and made noises randomly for 1 min. E1 then entered the room and asked the child to touch the robot with up to three friendly prompts. Finally, in the Spider episode, the mother and child sat in the chair, and in the other corner of the room sat a large plush spider affixed to a remote-controlled truck. From behind the one-way mirror, E2 controlled the spider to approach halfway towards the dyad, return to the corner, approach all the way to the dyad, and then return to the corner, with 10-sec pauses between each movement. E1 then came into the room and asked the child to touch the spider with three friendly prompts.

All tasks were video/audiorecorded for offline coding of toddler and maternal behaviors. All participants completed Risk Room first, followed by one of four randomly assigned orders for the six novelty episodes. As reported previously (Kiel & Buss, 2010), only 1 of 33 toddler behaviors differed according to order, suggesting the single order effect may be a spurious finding. Parent behavior and maternal accuracy did not differ by order. Therefore, order was not considered further.

Laboratory staff contacted mothers for a follow-up assessment comprising two laboratory visits when children entered kindergarten. In the fall of the kindergarten year, children completed a 2-hour laboratory visit resembling the age 2 visit, with episodes updated to be age-appropriate. A primary experimenter (E1) greeted the child and parent, collected consent, and led the child to and from each of the tasks. Prior to the episodes, while the child completed an interview with E1 not used for the current study, a second female experimenter (E2), described each episode and asked the mother to make two to three specific predictions about her child’s behavior (Table 1). The child completed episodes alone but checked in with the parent in between each one.

Table 1.

Maternal predictions and corresponding child behaviors for kindergarten accuracy variable.

| Maternal Prediction (“Will your child…”) | Child Behavior |

|---|---|

| Playing with Lion | |

| Approach the lion? | Lion approach composite |

| Play with the lion? | Lion play composite |

| Be wary of the lion? | Lion fear composite |

| Stranger Working | |

| Approach the stranger? | Stranger Working approach composite |

| Play with the stranger? | Stranger Working play composite |

| Be wary of the stranger? | Stranger Working fear composite |

| Stranger Approach | |

| Approach the stranger? | Stranger Approach approach composite |

| Smile at the stranger? | Stranger Approach facial pleasure composite |

| Be wary of the stranger? | Stranger Approach fear composite |

| Scary Mask | |

| Approach the stranger? | Scary Mask approach composite |

| Try to run away from the stranger? | Scary Mask withdrawal composite |

In Playing with Lion, the child began alone in the observation room. E2 entered the room, dressed in a lion costume that completely covered her body and head. In a friendly tone, the lion greeted the child and asked her or him to engage with her in three 1-min activities (doing the chicken dance along with the song, playing hot potato, and playing Simon Says). The lion then said goodbye and left the room. For Scary Mask, E1 led the child into a room in which E2 stood with her back to the door, dressed in a large gray hoodie and, at first unseen by the child, a Halloween-style mask. E2 then turned around to face the child, took a step towards the child, and introduced herself to the child, with 15 sec of staring at the child in between each of these steps. E2 then took off the mask, explained that she was playing with Halloween costumes, and invited the child to explore the mask while offering debriefing statements (e.g., “It’s just a mask, it can’t hurt you.”). E2 then excused herself and exited the room. For Stranger Working, E1 showed the child into the observation room, which contained a game meant for more than one player. After 30 sec, an unfamiliar female assistant (FA), unique from E2, entered the room with a pen and paper, sat down in a desk, and began working. FA did not look at or speak to the child unless the child initiated interaction. After 2 min, FA left the room. In Stranger Approach, the child began seated in a chair, alone in a room. After 30 sec, an unfamiliar male adult entered the room and greeted the child. Over the course of 1 min, the stranger conversed with the child according to a standardized script and responded to the child’s verbalizations appropriately. He then excused himself under the guise of looking for E1.

In the second kindergarten laboratory visit, children interacted with two to three unfamiliar same-sex peers in a 15-min free play, card sorting task, and speech delivery according to the Play Observation Scale (POS) manual (Rubin, 2001). The current study focuses on the free play, in which children were shown into a room of toys and activities and instructed to “play however you like” while the experimenter was out of the room.

Coding

For both age 2 and kindergarten variables, coders were trained by a master coder. After 10–20 hrs of training, depending on coding type, coders were required to reach adequate reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), kappa, or percent-agreement > .80) prior to coding independently. Approximately 10–20% of cases were double coded by the master coder to prevent coder drift. Percent-agreement was computed for behaviors scored epoch-by-epoch due to the large number of zeros, which can negatively influence other metrics. Reliabilities of codes exhibiting a more continuous scale were assessed with ICC, and categorical and count variables were assessed with kappa. Final reliabilities were computed prior to reconciliation of any scoring differences and are reported under measure descriptions. Different teams of coders scored each of the constructs, and different coders scored age 2 and kindergarten behaviors.

Measures

Age 2 Maternal Accuracy

Accuracy was derived from maternal predictions and toddler behaviors. Prior to children engaging in novelty episodes, mothers were asked to answer five to seven questions per episode (33 total) about their children’s behavior with possible responses of Definitely yes, Probably yes, Probably no, or Definitely no coded as 0, 1, 2, or 3, respectively. Questions inquired about both approach-oriented (e.g., “Will your child approach the clown?”) and fear-oriented (e.g., “Will your child want to stay close to you?”) behaviors; the latter were reverse-coded so that higher scores indicated more fear/less approach. Predictions were internally consistent (α = .88).

Corresponding toddler behaviors (e.g., approach to clown, proximity to mother, respectively, for the above examples) were then scored by trained coders. Final inter-rater reliabilities (percent-agreement) for toddler behaviors ranged from .70 to .98 (average = .84). A full list of maternal predictions and corresponding toddler fear behaviors, as well as detailed coding information for toddler behaviors, has been previously published (Kiel & Buss, 2010). Toddler behaviors were reversed as necessary so that higher scores indicated more fear/less approach and standardized.

The extent to which mothers’ predictions related to toddler behaviors was analyzed using a three-level multilevel model, which accounted for the nesting of predictions and behaviors (Level 1) within episodes (Level 2), and the nesting of episodes within participants (Level 3). Maternal predictions served as the predictor and toddler behaviors served as the dependent variable. Based on significant deviance change tests (Kiel & Buss, 2010), random components of maternal predictions at both Levels 2 and 3 were modeled in addition to the fixed effects. Overall, maternal predictions significantly related to toddler fear behaviors, γ = 0.08, t = 4.22, p < .001. We extracted Empirical Bayesian estimates of the slope associated with maternal predictions, which provided an estimate of how predictions related to toddler behavior for each mother. Thus, each mother’s individual slope represented how her predictions predicted her own toddler’s behavior. Individual slopes comprise the final variable of age 2 maternal accuracy for children’s distress to novelty.

Age 2 Fearful Temperament

Fearful temperament comprised five behaviors scored by trained coders from the Risk Room according to the Lab-TAB manual (Buss & Goldsmith, 2000). The first four behaviors were scored when the experimenter was out of the room. Latency to touch first toy (% agreement = .90) was the number of sec between the start of the episode and the toddler’s first intentional contact with any of the activities (M = 40.52, SD = 125.77, Range = 1 to 615). If the child never touched an activity, they were given a score of 615, which is the longest the episode lasted across the sample, plus 1 sec. Tentativeness of play (the extent to which the toddler hesitated or expressed wariness in their interactions with the activities; % agreement = .83; M = 1.49, SD = 0.75, Range = 0.18 to 3.00), attempt to be held (the intensity with which the toddler signaled to the mother a desire to be picked up; % = .94; M = 0.21, SD = 0.40, Range = 0.00 to 2.45), and approach towards parent (the extent to which toddlers visually, verbally, or physically checked in with the mother while playing; % = .73; M = 1.13, SD = 0.65, Range = 0.11 to 3.00) were each scored on a 0 (none) to 3 (extreme) scale each 10-sec epoch of the episode. Compliance to the experimenter (kappa = .75) was scored as the count of the number of activities children completed following experimenter prompt, ranging from 0 to 5 (M = 2.56, SD = 1.69, Range = 0 to 5). After compliance to experimenter was reversed, the five behaviors were found to be reasonably inter-correlated (rs = .25 to .71, all ps < .05) and found to load (all loadings > .65) on a single component explaining 60.24% of the variance in principal components analysis. Behaviors were therefore standardized and averaged to yield the final measure of age 2 fearful temperament. Eleven toddlers (12%) had scores greater than 1 SD above the mean on the fearful temperament composite, comparable to studies suggesting extreme fearful temperament (e.g., behavioral inhibition) characterizes 10–15% of the population (Fox et al., 2005).

Age 2 Maternal Protective Behavior

Comforting and overtly protective behaviors were scored on a 0 to 3 scale each 10-sec epoch of each episode according to a previous established coding system (Kiel & Buss, 2010). Comforting was scored as 0 (none), 1 (touching), 2 (actively physically soothing), or 3 (embracing). Protection was scored as 0 (none), 1 (slight protection, e.g., distracting child from stimulus), 2 (moderately intense but brief, e.g., turning the child away from the stimulus), or 3 (intense or prolonged, e.g., physically preventing child from approaching stimulus, moving them away from the stimulus, ending episode). The current study focused only on behaviors that were actively elicited by children to be consistent with theory about the reciprocal nature of toddler fear and protective parenting. Examples of elicitation include the toddler reaching their arms out to or leaning into their mothers. Un-elicited maternal behaviors that were not included in scoring were spontaneously enacted without a cue from the toddler, such as mothers’ back-rubs, hugs and kisses, or movement of the child when the child was engaged in the activity and/or not attending to the mother. Inter-rater reliability (ICC, established for coders scoring both the current sample and an independent sample) was found to be adequate for both comforting (.92) and protective (.84) behaviors. Scores for each behavior were averaged across epochs within each episode, and then across episodes (except protective behavior was not used from Stranger Working or Clown because they occurred with near-zero frequency). Composites of comforting and protective behaviors were highly correlated (r = .84, p < .001), so they were averaged to yield age 2 protective behavior.

Kindergarten Social Withdrawal

Social withdrawal was measured from both the Stranger Approach from the individual laboratory visit and from the Free Play of the peer visit. Coders scored Stranger Approach episode for the overall level of shyness displayed by the child across the episode on a 5-point scale (1 = no shyness or inhibition shown, 2 = withdraws once, is fidgety, or shows reduced activity; 3 = tense posture, instances of lowering or hiding face; 4 = strong tension, inactivity, fidgetiness, or freezing, or may ask to leave or ask stranger to leave, or avoidant for most of the episode; 5 = extremely shy, freezes, totally avoidance or resistant of stranger throughout the whole episode), based on Buss (2011). Inter-rater reliability was found to be good (ICC = .71).

Coders used the POS (Rubin, 2001) to code children for their social behavior during the Free Play portion of the peer visit. For each 10-sec epoch, the coder determined the child’s dominant social activity. Following previous studies using POS scoring, reticent behavior was coded when children engaged in either unoccupied (i.e., wandering aimlessly, staring into space) or onlooking (i.e., watching the other children without joining) behavior. Inter-rater reliability was found to be adequate (% agreement = .93, kappa = .61). Reticence represented the proportion of total epochs in which unoccupied or onlooking behavior was dominant.

Shyness and reticence demonstrated a moderately sized correlation (r = .26, p = .043), suggesting both shared and unique variance between them. These scores were standardized and averaged for the final measure of kindergarten social withdrawal so that children with the highest scores would have to score highly on both shyness and reticence.

Kindergarten Maternal Accuracy for Children’s Distress to Novelty

Accuracy for children’s distress to novelty was again derived as the statistical relation between maternal predictions and corresponding child behaviors across each of the novelty episodes from the individual laboratory visit. Maternal responses of Definitely Yes, Probably Yes, Probably No, or Definitely No to E2’s questions were coded on the same 0 to 3 scale, reversed as necessary so that higher scores indicated higher predictions of child fear. Mothers made 11 predictions across the episodes, which were internally consistent (α = .82).

Trained coders scored child behaviors corresponding to each of the maternal predictions. A number of behaviors were scored each sec of each episode, using the coding system from Buss (2011). For these behaviors, a number of parameters were calculated, including the latency (the number of sec from the beginning of the episode to the first instance), frequency (the count of the number of discrete times the behavior occurred), and duration (the total number of sec engaged in behavior). For behaviors scored on an intensity scale, average intensity across all sec and maximum intensity were also calculated. Across the scores below, inter-rater reliabilities were good (average kappa = 90.6, average % agreement = 97.6).

In all episodes, approach was scored on a 0 to 3 scale according to the intensity with which the child intentionally increased proximity to the stimulus (0 = stands/sits in place, 1 = turns/leans towards stimulus, 2 = one or two hesitant steps towards stimulus, 3 = non-hesitant walking towards stranger or otherwise initiates action to get within 2 feet of stimulus). The final approach composite comprised the average of standardized scores of the latency and (reversed) frequency, duration, average intensity, and maximum intensity, so that higher scores indicated less overall approach.

In Lion, Scary Mask, and Stranger Approach, several expressions of fear were coded. Facial fear (brows slightly raised or drawn together, lines or bulging in forehead, eyelids raised and tense, mouth open with corners straight back) was scored on a 0 to 3 scale (0 = none, 1 = one facial region showing movement or ambiguous expression, 2 = two facial regions showing codable movement or one region showing definite expression, 3 = change in all three facial regions or otherwise strong impression of facial fear). Bodily fear was also scored on a 0 to 3 scale (0 = none, 1 = decreased activity, 2 = tensing/freezing, 3 = trembling). Freezing (part of or whole body becomes still or rigid) was scored as present/absent each sec. The fear composite included reversed latency to freeze and durations of facial fear, bodily fear, and freezing.

In Lion and Stranger Working, the play composite included standardized scores of the duration of engagement in the activity (child actively plays with the toys or task provided, scored as present/absent) and average intensity of proximity (scored as 0 = greater than 2 feet away from the stimulus, 1 = within 2 feet of the stimulus, 2 = touching stimulus).

In Stranger Approach only, children’s facial pleasure (cheeks and lip corners raised, eyes may be squinted) was scored on a 0 to 3 scale (0 = no smiling, 1 = small smile with lips slightly upturned and no involvement of cheeks or eyes, 2 = medium smile with lips upturned, perhaps mouth open, slight bulging of cheeks and some crinkling about the eyes, 3 = large smile with lips stretched broadly and quite upturned, perhaps mouth open, definite bulging of cheeks and noticeable crinkling of eyes). The facial pleasure composite included standardized scores of the latency and (reversed) frequency, duration, average intensity and maximum intensity.

Finally, in Scary Mask only, a withdrawal composite was calculated from several behaviors. Withdrawal was scored on a 0 to 3 scale according to whether the child intentionally increased in physical distance from the stranger (0 = none/stands or sits in place, 1 = turns or leans away from the stranger, 2 = one or two steps away from the stranger, 3 = goes to far corner of the room or retreats rapidly). Leave-taking was scored as present/absent as the child’s attempt to leave the room or requests that the stranger leave the room. The composite included standardized scores of the frequency and duration of each score, the average and maximum intensity of withdrawal, and the reversed latency to withdraw.

Similarly to the age 2 accuracy measure, kindergarten accuracy was derived from a three-level multilevel model that accounted for the nesting of child behaviors and maternal predictions (Level 1) within episodes (Level 2), and the nesting of episodes within participants (Level 3). Children’s behaviors (standardized) were the dependent variable, and maternal predictions acted as the predictor variable. Although a deviance-change test provided only marginal evidence that random components improved the fit of the model, χ2(4) = 5.40, p = .067, we included random components to be consistent with the age 2 accuracy measure and to allow for the extraction of participant-level Empirical Bayes (EB) estimates of the slope (each mother’s predictions in relation to her own child’s behaviors). Across the sample, maternal predictions did not significantly relate to children’s behaviors, γ = 0.04, t = 1.21, p = .227, suggesting that, across the sample, maternal accuracy was low. A low mean value does not preclude meaningful individual variation around the overall slope. The EB estimates provided the final variable of kindergarten maternal accuracy.

RESULTS

Preliminary Analyses and Handling of Missing Data

Initial analyses were completed in IBM SPSS version 25. Descriptive statistics were completed on primary study variables (Table 2). All variables reasonably adhered to a normal distribution, skew < |2.00| and kurtosis < |4.00|, except for protective behavior, skew = 2.03 and kurtosis = 5.08. We added a constant and performed a square root transformation, which brought protective behavior into reasonable limits, skew = 1.74, and kurtosis = 3.49. All subsequent analyses use this transformed variable.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlations for primary variables.

| Variable | M (SD) | Range | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age 2 Maternal Accuracy | .08 (.02) | .04 – .14 | .54*** | .35*** | .35** | .03 |

| 2. Maternal Protective Behavior | .16 (.20) | .00 – 1.08 | -- | .29** | .32* | .24 |

| 3. Toddler Fearful Temperament | −.01 (.80) | −1.11 – 3.39 | -- | .13 | .17 | |

| 4. Child Social Withdrawal | −.06 (.74) | −1.07 – 3.18 | -- | .35** | ||

| 5. Kindergarten Maternal Accuracy | .04 (.03) | −0.08 – 0.11 | -- |

Note. Descriptive statistics were computed prior to the transformation of the protective behavior variable. At age 2 and kindergarten, maternal accuracy was the empirical bayes (EB) estimate of the relation between maternal predictions and child behaviors from a multilevel model. Toddler fearful temperament and child social withdrawal were composites of Z-scores. Correlations were computed after protective behavior was submitted to statistical transformation but prior to handling missing values.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

All participants had age 2 measures (maternal accuracy, protective behavior, fearful temperament), but 29 participants (31.2%) did not complete the kindergarten assessment. Attrition resulted in 12.47% of observations of primary study variables missing. Participants with missing data did not differ from participants with complete data either in demographics (child biological sex, SES) or primary age 2 measures, all ts or χ2 < 1.32, ps > .20. Little’s Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test, which included all primary variables (Figure 1) and demographic variables, was non-significant, χ2(15) = 12.25, p = .660, suggesting that data did not statistically differ from the MCAR pattern. No variables differed according to children’s biological sex, ts < |1.90|, ps > .06, or SES, rs < .21, ps > .12, so they were not considered further. We used Full Information Maximum Likelihood in MPlus Version 7.3 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2014) to handle missing values in primary analyses.

Serial Mediation Model

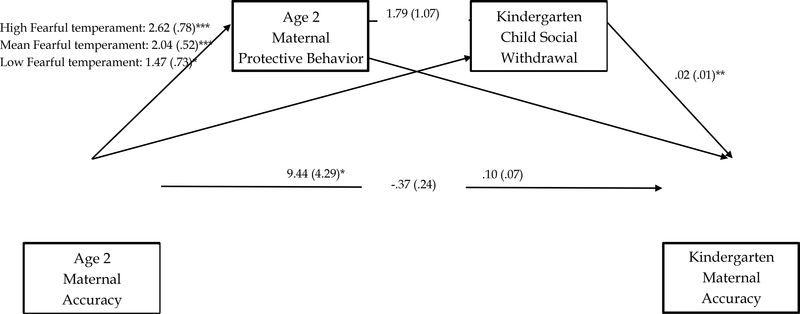

We analyzed the hypothesized serial mediation model (Figure 1) according to guidelines set forth by Hayes and Preacher (2013). The first suggested step is to test and probe hypothesized higher-order effects (i.e., moderated paths). We examined the moderation on Path A using OLS regression given that it was previously published as such (Kiel & Buss, 2010), is explicitly permitted within larger models tested in structural equation modeling software (Hayes & Preacher, 2013), and had no missing values. The regression model examining path A included the predictors of age 2 accuracy and fearful temperament (each centered at its respective mean), as well as their cross product to test the interaction, in relation to protective behavior. The overall model was significant, R2 = .33, F(3,89) = 14.75, p < .001. The interaction term, specifically, was significant, b = 0.72, SE = 0.36, t = 2.01, p = .048, sr2 = .030. Fearful temperament was re-centered at low (−1 SD), mean, and high (+1 SD) values to understand the nature of the interaction. Probing the interaction revealed that maternal accuracy related to protective behavior increasingly strongly across low, b = 1.47, SE = 0.55, t = 2.69, p = .009, sr2 = .054, mean, b = 2.04, SE = 0.41, t = 4.93, p < .001, sr2 = .182, and high, b = 2.62, SE = 0.46, t = 5.72, p < .001, sr2 = .246, values of fearful temperament, with the latter approaching a large effect. Thus, maternal accuracy most strongly related to protective behavior for the most temperamentally fearful children. Given the significant interaction, we proceeded with the moderated serial mediation model.

We quantified conditional indirect effects as the product of paths comprising the indirect effect (A*B1*B2 in Figure 1) occurring at specific values (−1 SD, mean, and +1 SD) of fearful temperament and obtained the bootstrapped 95% confidence interval (CI) for each (Hayes & Preacher, 2013). The 95% CIs of indirect effects conditioned on values of −1 SD, indirect effect = 0.047, 95% CI[−0.007, 0.221], and the mean, indirect effect = 0.065, 95% CI[−.001, 0.255], of fearful temperament contained zero, suggesting they were not statistically significant. The 95% CI surrounding the indirect effect conditioned on +1 SD of fearful temperament did not contain zero, indirect effect = 0.084 95% CI[0.006, 0.353]. The confidence interval suggests that age 2 protective parenting and then kindergarten child social withdrawal provided an indirect path by which age 2 maternal accuracy predicted kindergarten maternal accuracy, but only for highly fearful children. The direct relation between age 2 maternal accuracy and kindergarten maternal accuracy was not significant, b = −0.37, SE = 0.24, t = −1.55, p = .122, 95% CI[−0.900, 0.034].

Individual paths are labeled in Figure 2. Of note, although the regression coefficient for the interaction term on Path A remained the same value, it was not statistically significant in the FIML estimation because it produced a larger standard error. Mirroring the results from probing the interaction in OLS regression, Path A was significant across values of maternal accuracy; the regression coefficients increased as maternal accuracy increased. Remaining paths were tested above and beyond the variable(s) appearing earlier in the model. The relation between age 2 protective behavior and kindergarten social withdrawal was marginally significant. Kindergarten social withdrawal demonstrated a significant relation to kindergarten maternal accuracy. Although the chi-square test was significant, χ2(12) = 63.55, p < .001, other metrics indicated the model adequately fit the data, RMSEA = 0.00 (90% CI [0.00, 0.15]), CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.03, SRMR = 0.053.

Figure 2.

Path analyses for conditional serial mediation model. Paths represent unstandardized regression coefficients (standard errors in parentheses). All paths estimated in Mplus using FIML. The serial indirect effect was significant for high fearful temperament. *p < .05. ***p < .001.

Post-Hoc Analyses

The components of social withdrawal (shyness with an adult, reticence with same-aged peers) were aggregated because of an a priori decision to more holistically cover the construct of social withdrawal across contexts. Given the modest correlation between the two measures, we reran the model twice, with each model substituting in one of the individual components for social withdrawal. The model including peer reticence had a significant chi-square test, χ2(12) = 50.31, p < .001, but other metrics indicated the model adequately fit the data, RMSEA = 0.00 (90% CI [0.00, 0.09]), CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.20, SRMR = 0.026. The serial indirect effect was not significant for peer reticence at any value of fearful temperament (all 95% CIs contained zero).

For shyness with an adult, the chi-square test of the model was significant, χ2(12) = 65.02, p < .001, and the TLI (0.87) fell below the threshold of adequate fit (≥ 0.95). Other indices indicated adequate fit, RMSEA = 0.08 (90% CI [0.00, 0.19]), CFI = 0.96, SRMR = 0.076. The serial indirect effect was significant at mean, indirect effect = 0.068, 95% CI[0.003, 0.261], and high fearful temperament, indirect effect = .087, 95% CI[0.009, 0.350], but not at low fearful temperament, indirect effect = 0.049, 95% CI[−0.003, 0.229]. The difference in indirect effects across the two measures of social withdrawal seems to be driven by relations between age 2 protective behavior and shyness with an adult b = 2.59, SE = 1.36, β = 0.26, t = 1.91, p = .056, versus with peer reticence b = 0.06, SE = 0.21, β = 0.04 t = 0.27, p = .789. Therefore, the primary results may be driven by shyness with an adult, rather than peer reticence, primarily because of their respective prediction from age 2 protective behavior.

DISCUSSION

Although previous work has revealed the integral role of maternal accuracy for children’s distress to novelty for anxiety-spectrum outcomes in children (Cobham & Rapee, 1999; Kiel & Buss, 2011), the results from the current examination are the first to test a possible mechanism underlying maternal accuracy’s maintenance over time. Specifically, the current investigation provides initial evidence for a dynamic, bidirectional process between mothers and their children, involving toddler fearful temperament, maternal protective behavior, and later child social withdrawal, which unfolded to link maternal accuracy for children’s distress to novelty across time.

Maternal accuracy in toddlerhood interacted with toddler fearful temperament to relate to concurrent protective parenting behaviors. For temperamentally fearful children, maternal protective behaviors during toddlerhood and social withdrawal in childhood linked maternal accuracy from age 2 to kindergarten. These results suggest a cyclical process by which maternal cognitions relate to parenting behavior only for highly fearful children, which predicts subsequent child behavior that feeds back into maternal cognitions. Given that this is the first test of this complex model, these results should be considered preliminary and require replication.

It was surprising that protective behavior with toddlers did not more strongly predict children’s social withdrawal at kindergarten. It is possible that protective behavior itself evolves and develops over the course of childhood, so a different form of protection in kindergarten would relate more strongly to social withdrawal concurrently. Perhaps having an additional intermediary variable of protective behavior in later childhood would more robustly connect constructs from toddlerhood to those in the early school years. Methodologically, it is not uncommon for observational measures to relate less strongly to one another than survey measures, which share method variance due to relying on one person’s reporting tendencies. We chose not to use survey measures for these constructs specifically to avoid the confound of shared method variance. Post-hoc analyses revealed that the overall indirect effect through social withdrawal, a composite of peer reticence and shyness with an adult, may have been driven by a stronger relation between protective behavior and adult-oriented shyness than with peer reticence. Both protective behavior and kindergarten shyness involved adults, which may have strengthened their relation. We chose to observe maternal protective behavior around adults during toddlerhood, as mothers may be more accustomed to engaging in protective behavior around adults when their children are toddlers. We did not have a measure of maternal protective behavior during peer interactions in toddlerhood, which may be more relevant to peer reticence at kindergarten entry. Continued investigation into these specific venues for parental intervention and children’s behaviors could elucidate further nuances in longitudinal relations.

Additional instability between age 2 and kindergarten was surprising. For example, age 2 fearful temperament did not predict social withdrawal in bivariate correlations. Foundational work on behavioral inhibition has shown moderate stability in temperament. Some inhibited toddlers would be expected to maintain their high levels of inhibition, whereas others may demonstrate decreases, resulting in change in rank order and low correlations between fearful temperament and social withdrawal over the course of early childhood (Bornstein, Putnick, & Esposito, 2017; Kagan et al., 1984). Thus, there is heterogeneity among toddlers considered high in fearful/inhibited temperament. There has been effort to identify toddlers more homogenous in temperament. Toddlers who show consistent fear across contexts that most other children find engaging (“low threat” contexts) have a dysregulated fear profile (Buss, 2011). Dysregulated fear identifies children who are stable in their fear and inhibition, more so than traditionally measured fearful temperament, which was used in the current study. The current study did not differentiate children who showed consistent fearfulness across contexts from those who did not, which may explain why our measure of fearful temperament did not show a direct association to childhood social withdrawal. Across children, it is natural for shyness, inhibition, and other types of fear to decrease across early development, with top-down control provided by executive functions (inhibitory control, attentional control) facilitating the decline (Brooker, Kiel, & Buss, 2016; Eggum-Wilkens, Reichenberg, Eisenberg, & Spinrad, 2016). These patterns may happen differently depending on children’s level of risk, as inhibitory control may tend to relate to decreased shyness for most children (Eggum-Wilkens et al., 2016), but children who are stable in their social fear may experience inhibitory control as “overcontrol” that maintains anxiety risk (Brooker et al., 2016). An integrative model from Degnan and Fox (2007) suggested that the confluence of intraindividual (including top-down regulatory mechanisms) and contextual factors (especially parenting) may lead to stability versus instability in inhibited temperament and related outcomes. Future work that refines our understanding of how maternal cognitions, such as maternal accuracy for children’s distress to novelty, function dynamically with child temperament would benefit from using measures of fearful temperament that more explicitly address stability.

It was also surprising that maternal accuracy in toddlerhood did not directly predict maternal accuracy at children’s kindergarten entry. Just as children are rapidly developing over early childhood, maternal cognitions about children’s interactions with novelty may also evolve. Perhaps the extent to which children change in their behavioral tendencies disrupts stability (or relates to meaningful change) in maternal cognitions. Given that children who do remain stable in their fearfulness are likely included among those who have high scores in toddlerhood (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2015), it makes sense that the indirect link between maternal accuracy in toddlerhood and maternal accuracy at kindergarten was strongest for mothers of the most temperamentally fearful children.

The current investigation made use of longitudinal and observational data, which strengthen our findings. However, results should be considered with an understanding of the study’s limitations. Aspects of the study were cross-sectional in nature, investigating relations among fearful temperament, maternal accuracy, and protective parenting at age 2, and relations between children’s social withdrawal and maternal accuracy during children’s kindergarten year. The cross-sectional design within each time point limits our conclusions about longitudinal relations. To more robustly test our proposed serial model, it will be important for future work to use more complete longitudinal designs, limiting the reliance on cross-sectional relations. Furthermore, the use of a modestly sized sample for complex analyses warrants consideration of these results as preliminary, requiring replication with larger samples. Replication is particularly important for the longitudinal piece of the design, as the association between age 2 protective behavior and kindergarten social withdrawal yielded a small effect. In addition to increasing sample size, future research may focus on identifying mechanisms in between toddlerhood and kindergarten entry or moderators that strengthen the link between protective parenting and children’s social withdrawal. Because protective parenting, fearful temperament, and child social withdrawal were not also measured at multiple time points, alternative models could not be tested. For example, although we modeled child social withdrawal as the predictor of maternal accuracy at the kindergarten assessment, it is equally plausible that accuracy would predict children’s social withdrawal through protective parenting later in childhood.

Additional measurement considerations are warranted. First, our exclusive focus on maternal parenting behaviors ignores the impact of other parenting behaviors in the home. Fathers can have different cognitions about their children’s behaviors (Bögels & Phares, 2008) and play a fundamental role child development, broadly, and anxiety risk, specifically (Hastings et al., 2008). The other mother in same-sex parent dyads would also undoubtedly influence children’s outcomes, and our results may not be generalizable to same-sex parent dyads of fathers. Second, our sample was relatively homogenous and largely consisted of mother-child dyads from middle-class, European American backgrounds. Cultural background can certainly impact maternal cognitions about parenting and children’s behaviors (Bornstein, 2016; Chen, 2010). Therefore, future work should examine the broader family unit across cultures to better understand how results generalize in different contexts. Additionally, the current investigation’s targeted focus was not able to test the impact of other variables (e.g., family composition, maternal characteristics, preschool enrollment, socialization experience) that may have contributed to change in maternal accuracy and children’s social withdrawal over time. Genetics, in particular, may play a role in linking maternal behavior and cognitions with child temperament and social withdrawal. The same genetic influences on temperamentally fearful children’s vigilance towards novelty may impact their mothers’ vigilance towards their children’s fearful behaviors, such that mothers who are more anxious may be more likely to respond with protection (Bögels & van Melick, 2004). Future studies would benefit from including other maternal characteristics (fearfulness, anxiety) that may be related to maternal accuracy in important ways. Despite these limitations, we still found a significant indirect effect that spans 3 years of maternal protection in toddlerhood and social withdrawal in kindergarten linking maternal accuracy for children’s distress to novelty across early development.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE, APPLICATION, AND THEORY

Results from the current examination enhance existing theories in the literature that detail the bidirectional effects between children and their parents by also considering maternal cognitions. Dadds and Roth (2001) proposed the anxious-coercive cycle, theorizing that anxiety-prone children elicit parenting behaviors that are overly warm and protective (i.e., protective parenting). When parents respond with protection, they can quickly alleviate their children’s distress, which then increases the likelihood that parents will respond protectively in the future. Although not intended, these protective parenting responses maintain withdrawal and anxious behaviors over time, as children learn to rely on their parents in times of stress and are reinforced with parental attention for wary and avoidant responses (Hastings & Rubin, 1999). Mothers who perceive their children as fearful and inhibited may be more inclined to respond with parenting that is protective, which then increases children’s anxiety over time (Dadds & Roth, 2001). Our results are consistent with the idea that protective parenting and children’s social withdrawal act as the dynamic mechanism underlying maternal accuracy across time, as the relation between fearful temperament and protective parenting predicted childhood social withdrawal in kindergarten, which was then associated with mothers’ accurate attunement to their children’s inhibited and withdrawn behavior. Our results therefore suggest a more nuanced understanding of the emergence of social withdrawal and anxiety in children by considering maternal thoughts about their children as a fundamental aspect of dynamic parent-child interactions.

Maternal cognitions about their children are at the root of maternal accuracy for children’s distress to novelty, and such cognitions and attitudes about children’s shy and wary behaviors provide one area of targeted intervention. Previous work demonstrates that maternal attitudes about their children’s shy behaviors moderated the relation between children’s behaviors and parenting responses (Hastings & Rubin, 1999). Indeed, parents who endorse more parent-centered goals (i.e., to obtain compliance and achieve a “quick-fix”) for their children’s distress (Coplan, Hastings, Lagacé-Séguin, & Moulton, 2002) are more likely to respond to their children’s inhibited behaviors with protective parenting (Kiel & Buss, 2012). It is likely that parents may benefit from psychoeducation regarding this pattern and the long-term benefits of gentle encouragement and developmentally appropriate challenges for children at risk for anxiety (Kiel et al., 2016). It would not be suggested that interventionists decrease maternal accuracy, per se. However, by focusing on broadly reshaping maternal cognitions to interpret children’s fear displays as less distressing and problematic, it may decrease mothers’ vigilance towards their children’s dispositional fear (which we suggest may be manifested as maternal accuracy) and assist mothers in inhibiting protection that reinforces children’s anxiety across time. Although our investigation did not explicitly examine these maternal attitudes and goals, future work should investigate maternal cognitions that may link maternal accuracy for children’s distress to novelty and protective parenting behaviors.

Given maternal accuracy’s apparent role in children’s anxiety-spectrum problems, the present investigation suggests that early development is an optimal time to intervene. Parenting responses in the toddlerhood and preschool periods are particularly salient environmental cues that help to form early regulation abilities in children (Calkins, Propper, & Mills-Koonce, 2013). Numerous studies have similarly found that parenting in toddlerhood and preschool is particularly relevant for the emergence of anxiety-related symptoms (e.g., Degnan, Henderson, Fox, & Rubin, 2008; Rubin et al., 2002). Additional intervention work suggests that toddlerhood and preschool, specifically, are ideal for effective interventions to reduce anxiety risk in children (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2015; Rapee, Kennedy, Ingram, Edwards, & Sweeney, 2005).

In conclusion, the present study provides evidence regarding the factors of protective parenting and child social withdrawal that link maternal accuracy for children’s distress to novelty across early development and point to several areas for future investigation.

Acknowledgements

We express our appreciation to the staff of the Emotion Development Lab who assisted with data collection and coding, and the families and toddlers who participated in this project. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors alone, and endorsement by the authors’ institutions or the National Institutes of Health is not intended and should not be inferred.

Funding

This work was supported by grant F31 MH077385 from the National Institute of Mental Health and by grant R01075750 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Elizabeth Kiel was supported by grant 2R15 HD076158 from the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development during the completion of the manuscript.

Role of the Funders

None of the funders or sponsors of this research had any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

Each author signed a form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. No authors reported any financial or other conflicts of interest in relation to the work described.

Ethical Principles

The authors affirm having followed professional ethical guidelines in preparing this work. These guidelines include obtaining informed consent from human participants, maintaining ethical treatment and respect for the rights of human or animal participants, and ensuring the privacy of participants and their data, such as ensuring that individual participants cannot be identified in reported results or from publicly available original or archival data.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth J. Kiel, Miami University

Anne E. Kalomiris, Miami University

Kristin A. Buss, The Pennsylvania State University

REFERENCES

- Bates JE, & Bayles K (1984). Objective and subjective components in mothers’ perceptions of their children from age 6 months to 3 years. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 111–130. [Google Scholar]

- Bayer JK, Sanson AV, & Hemphill SA (2006). Parent influences on early childhood internalizing difficulties. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 27(6), 542–559. 10.1016/j.appdev.2006.08.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RQ (1979). Parent, child, and reciprocal influences. American Psychologist, 34(10), 821–826. [Google Scholar]

- Bögels SM, & van Melick M (2004). The relationship between child-report, parent self-report, and partner report of perceived parental rearing behaviors and anxiety in children and parents. Personality and Individual Differences, 37(8), 1583–1596. 10.1016/j.paid.2004.02.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bögels S, & Phares V (2008). Fathers’ role in the etiology, prevention and treatment of child anxiety: A review and new model. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(4), 539–558. 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH (2016). Determinants of parenting. In Cicchetti D (Ed.), Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 4, Risk, resilience, and intervention (3rd ed., pp. 180–270). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Putnick DL, & Esposito G (2017). Continuity and stability in development. Child Development Perspectives, 11, 113–119. 10.1111/cdep.12221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker RJ, Kiel EJ, & Buss KA (2016). Early social fear predicts kindergarteners’ socially anxious behaviors: Direct associations, moderation by inhibitory control, and differences from nonsocial fear. Emotion, 16(7), 997–1010. 10.1037/emo0000135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brophy-Herb HE, Schiffman RF, Bocknek EL, Dupuis SB, Fitzgerald HE, Horodynski M, … Hillaker B (2011). Toddlers’ social-emotional competence in the contexts of maternal emotion socialization and contingent responsiveness in a low-income sample. Social Development, 20(1), 73–92. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00570.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA (2011). Which fearful toddlers should we worry about? Context, fear regulation, and anxiety risk. Developmental Psychology, 47(3), 804–819. 10.1037/a0023227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, & Goldsmith HH (2000). Manual and normative data for the laboratory temperament assessment battery—toddler version. University of Wisconsin, Madison: Psychology Department Technical Report. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Propper C, & Mills-Koonce WR (2013). A biopsychosocial perspective on parenting and developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 25(4pt2), 1399–1414. 10.1017/S0954579413000680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X (2010). Shyness-inhibition in childhood and adolescence: A cross-cultural perspective. In Rubin KH &Coplan RJ (Eds.), The development of shyness and social withdrawal (pp. 213–235). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, McElwain NL, Berry D, & Emery HT (2019). Within-person fluctuations in maternal sensitivity and child functioning: Moderation by child temperament. Journal of Family Psychology, 33, 857–867. 10.1037/fam0000564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Rubin KH, O’Brien KA, Coplan RJ, Thomas SR, Dougherty LR, …Wimsatt, M. (2015). Preliminary evaluation of a multimodal early intervention program for behaviorally inhibited preschoolers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83, 534–540. 10.1037/a0039043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobham VE, & Rapee RM (1999). Accuracy of predicting a child’s response to potential threat: A comparison of children and their mothers. Australian Journal of Psychology, 51(1), 25–28. 10.1080/00049539908255331 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analyses for the social sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbauni Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Hastings PD, Lagacé-Séguin DG, & Moulton CE (2002). Authoritative and authoritarian mothers’ parenting goals, attributions, and emotions across different childrearing contexts. Parenting, 2(1), 1–26. 10.1207/S15327922PAR0201_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, & Roth JH (2001). Family processes in the development of anxiety problems. In Vasey MW & Dadds MR (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology of anxiety (pp. 278–303). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davidov M, & Grusec JE (2006). Untangling the links of parental responsiveness to distress and warmth to child outcomes. Child Development, 77(1), 44–58. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00855.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, & Fox NA (2007). Behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders: Multiple levels of a resilience process. Development and Psychopathology, 19, 729–746. 10.1017/S0954579407000363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, Henderson HA, Fox NA, & Rubin KH (2008). Predicting social wariness in middle childhood: The moderating roles of childcare history, maternal personality and maternal behavior. Social Development, 17(3), 471–487. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00437.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards SL, Rapee RM, & Kennedy S (2010). Prediction of anxiety symptoms in preschool-aged children: Examination of maternal and paternal perspectives. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(3), 313–321. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02160.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggum-Wilkens ND, Reichenberg RE, Eisenberg N, & Spinrad TL (2016). Components of effortful control and their relations to children’s shyness. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 40, 544–554. 10.1177/0165025415597792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Marshall PJ, Nichols KE, & Ghera MM (2005). Behavioral inhibition: Linking biology and behavior within a developmental framework. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 235–262. 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher KC (2002). Does child temperament moderate the influence of parenting on adjustment?. Developmental Review, 22(4), 623–643. 10.1016/S0273-2297(02)00503-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grady JS, & Karraker K (2017). Mother and child temperament as interacting correlates of parenting sense of competence in toddlerhood. Infant and Child Development, 26, e1997. 10.1002/icd.1997 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW (2009). Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 549–576. 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory A, & Rimm-Kaufman S (2008). Positive mother-child interactions in kindergarten: Predictors of school success in high school. School Psychology Review, 37, 499–515. [Google Scholar]

- Grover RL, Ginsburg GS, & Ialongo N (2007). Psychosocial outcomes of anxious first-graders: A seven-year follow-up. Depression and Anxiety, 24, 410–420. 10.1002/da.20241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouze KR, Hopkins J, Bryant FB, & Lavigne JV (2016). Parenting and anxiety: Bidirectional relations in young children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 45(6), 1169–1180. 10.1007/s10802-016-0223-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD, & Rubin KH (1999). Predicting mothers’ beliefs about preschool-aged children’s social behavior: Evidence for maternal attitudes moderating child effects. Child Development, 70(3), 722–741. 10.1111/1467-8624.00052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD, Sullivan C, McShane KE, Coplan RJ, Utendale WT, & Vyncke JD (2008). Parental socialization, vagal regulation, and preschoolers’ anxious difficulties: Direct mothers and moderated fathers. Child Development, 79(1), 45–64. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01110.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, & Preacher KJ (2013). Conditional process modeling: Using structural equation modeling to examine contingent causal processes. In Hancock GR & Miller RO (Eds.), A second course in structural equation modeling (2nd ed., pp. 219–266). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hiebert-Murphy D, Williams EA, Mills RSL, Walker JR, Feldgaier, Warren, M., …Cox BJ (2011). Listening to parents: The challenges of parenting kindergarten-aged children who are anxious. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17, 384–399. 10.1177/1359104511415495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick JS, Clarke C, Snidman N, & Garcia-Coll C (1984). Behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar. Child Development, 55(6), 2212–2225. [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, & Buss KA (2006). Maternal accuracy in predicting toddlers’ behaviors and associations with toddlers’ fearful temperament. Child Development, 77(2), 355–370. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00875.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, & Buss KA (2010). Maternal accuracy and behavior in anticipating children’s responses to novelty: Relations to fearful temperament and implications for anxiety development. Social Development, 19(2), 304–325. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00538.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, & Buss KA (2011). Prospective relations among fearful temperament, protective parenting, and social withdrawal: The role of maternal accuracy in a moderated mediation framework. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(7), 953–966. 10.1007/s10802-011-9516-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, & Buss KA (2012). Associations among context-specific maternal protective behavior, toddlers’ fearful temperament, and maternal accuracy and goals. Social Development, 21(4), 742–760. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2011.00645.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, Premo JE, & Buss KA (2016). Maternal encouragement to approach novelty: A curvilinear relation to change in anxiety for inhibited toddlers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(3), 433–444. 10.1007/s10802-015-0038-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiff CJ, Lengua LJ, & Zalewski M (2011). Nature and nurturing: Parenting in the context of child temperament. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14(3), 251–301. 10.1007/s10567-011-0093-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein MR, Lengua L, Thompson SF, Moran L, Ruberry EJ, Kiff C, & Zalewski M (2018). Bidirectional relations between temperament and parenting predicting preschool-age children’s adjustment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 47(Supp), S113–S126. 10.1080/15374416.2016.1169537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren-Karie N, Oppenheim D, Dolev S, Sher E, & Etzion-Carasso A (2002). Mothers’ insightfulness regarding their infants’ internal experience: Relations with maternal sensitivity and infant attachment. Developmental Psychology, 38, 534–542. 10.1037/0012-1649.38.4.534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krink S, Muehlhan C, Luyten P, Romer G, & Ramsauer B (2018). Parental reflective functioning affects sensitivity to distress in mothers with postpartum depression. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27, 1671–1681. 10.1007/s10826-017-1000-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laurin JC, Joussemet M, Tremblay RE, & Boivin M (2015). Early forms of controlling parenting and the development of childhood anxiety. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(11), 3279–3292. 10.1007/s10826-015-0131-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EM, & Crockenberg SC (2003). The impact of maternal characteristics and sensitivity on the concordance between maternal reports and laboratory observations of infant negative emotionality. Infancy, 4(4), 517–539. 10.1207/S15327078IN0404_07 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon CA, & Bernier A (2017). Twenty years of research on parental mind-mindedness: Empirical findings, theoretical and methodological challenges, and new directions. Developmental Review, 46, 54–80. 10.1016/j.dr.2017.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meins E, Ferryhough C, Fradley E, & Tuckey M (2001). Rethinking maternal sensitivity: Mothers’ comments on infants’ mental processes predict security of attachment at 12 months. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42, 637–648. 10.1017/S0021963001007302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachmias M, Gunnar M, Mangelsdorf S, Parritz RH, & Buss K (1996). Behavioral inhibition and stress reactivity: The moderating role of attachment security. Child Development, 67(2), 508–522. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01748.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson L, Rimm-Kaufman SE, & Brock LL (2009). Kindergarten adjustment difficulty: The contribution of children’s effortful control and parental control. Early Education and Development, 20, 775–798. 10.1080/10409280802571236 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, Sanson AV, Rothbart MK, (2002). Child temperament and parenting. In Bornstein MH (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Volume I: Children and parenting (pp. 255–278). Abingdon, United Kingdom: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, Kennedy S, Ingram M, Edwards S, & Sweeney L (2005). Prevention and early intervention of anxiety disorders in inhibited preschool children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 488–497. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH (2001). The Play Observation Scale (POS). College Park: University of Maryland, Center for Children, Relationships, and Culture. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Burgess KB, & Hastings PD (2002). Stability and social–behavioral consequences of toddlers’ inhibited temperament and parenting behaviors. Child Development, 73(2), 483–495. 10.1111/1467-8624.00419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Coplan RJ, & Bowker JC (2009). Social withdrawal in childhood. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 141–171. 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Hastings PD, Stewart SL, Henderson HA, & Chen X (1997). The consistency and concomitants of inhibition: Some of the children, all of the time. Child Development, 68(3), 467–483. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01952.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford HJV, Booth CR, Luyten P, Bridgett DJ, & Mayes LC (2015). Investigating the association between parental reflective functioning and distress tolerance in motherhood. Infant Behavior and Development, 40, 54–63. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2015.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A (2010). A unified theory of development: A dialectic integration of nature and nurture. Child Development, 81, 6–22. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01378.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamir-Essakow G, Ungerer JA, Rapee RM, & Safier R (2004). Caregiving representations of mothers of behaviorally inhibited and uninhibited preschool children. Developmental Psychology, 40(6), 899–910. 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinrad TL, Stifter CA, Donelan-McCall N, & Turner L (2004). Mothers’ regulation strategies in response to toddlers’ affect: Links to later emotion self-regulation. Social Development, 13(1), 40–55. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2004.00256.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]