Abstract

Ophthalmic vascular occlusion is an infrequent but devastating complication following cosmetic facial filler injection. We report a case of developing retinal artery occlusion after poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) injection. A 49-year-old woman with multiple chronic diseases experienced sudden central visual loss and severe ocular pain in the right eye immediately after PLLA injection in the temporal region. Her best-corrected visual acuity in the right eye dropped from 20/20 to 20/200. Fundus photography showed marked optic disc edema and localized retinal whitening in the territory of the blocked vessels. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography revealed localized hyperreflectivity of the inner retina and retinal edema. Fluorescein angiography showed delayed filling of the retinal arteries and absence of retinal perfusion in the affected areas. Despite prompt aggressive management of the condition with ocular massage, topical brimonidine eyedrops, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy, the patient suffered permanent visual loss due to optic atrophy. Among all the subcutaneous filler materials, PLLA has not been a common cause of vascular complications, especially when injected in the temporal region, as this area has not been considered dangerous in the previous literature. Practitioners should be aware of the risk of visual loss, and extra care should be given on those who originally have a higher risk for vascular complications.

Keywords: Cosmetic filler injection, poly-L-lactic acid, retinal artery occlusion

Introduction

With the rising popularity of cosmetic filler injections for facial rejuvenation, there were increasing reports of the complications in the last decade. Visual loss is one of the devastating complications resulting from ophthalmic vascular occlusion. We report a case who presented with sudden central visual loss after the subcutaneous filler injections of poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) in the temporal region. The occurrence and mechanism of retinal artery occlusion after subcutaneous injection of PLLA are discussed.

Case Report

A 49-year-old woman was referred to our emergency department due to sudden onset of a central visual defect in her right eye after subcutaneous injection of PLLA (Sculptra®, Valeant Aesthetics, Bridgewater, New Jersey, USA) in the right temporal region for soft-tissue augmentation by a beautician approximately an hour ago. She also experienced severe ocular pain, dizziness, nausea, and photopsia immediately after the injection.

She had a history of hypertension and diabetes mellitus and was on regular medications for more than 10 years. In addition, she underwent percutaneous coronary intervention with stent placement 5 months ago and was on dual-antiplatelet therapy for coronary artery disease. Moreover, she had received pan-retinal photocoagulation and intravitreal injections of ranibizumab for her bilateral diabetic macular edema at our branch hospital. According to the latest chart record before the episode, her best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/20 in both eyes.

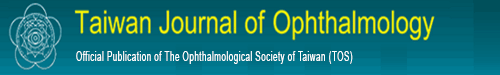

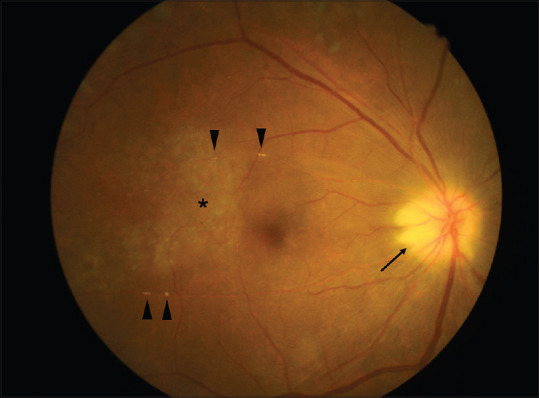

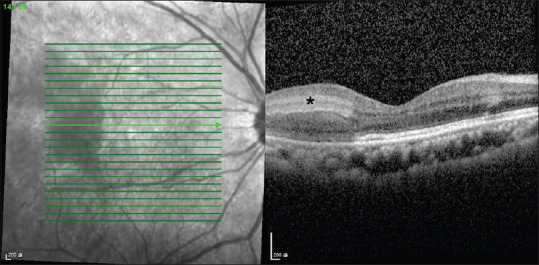

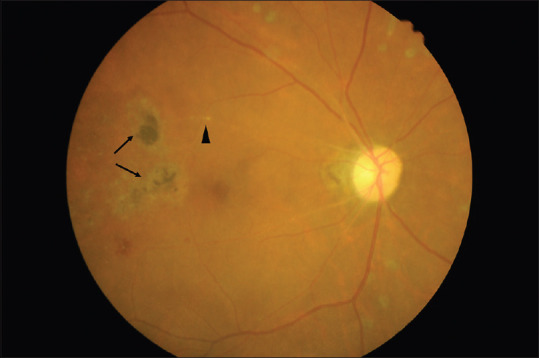

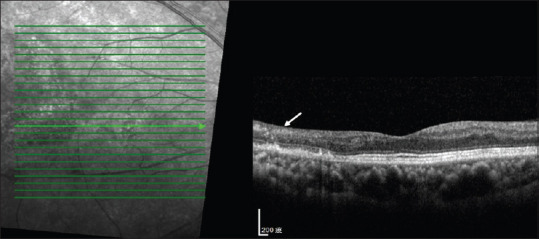

On examination in the emergency room, her BCVA was 20/200 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye. The intraocular pressure measured by noncontact tonometer was 22 mmHg in the right eye and 24 mmHg in the left eye. There was a relative afferent pupillary defect in the right eye, and the pupil was mid-dilated. No neurogenic signs such as ptosis or ophthalmoplegia were observed. Dilated fundoscopy showed marked optic disc edema and localized retinal whitening in the territory of the blocked vessels [Figure 1]. The scattered dot retinal hemorrhage had been observed in the previous fundus image as a sign of diabetic retinopathy. Refractive plaques were seen within the arterioles superior and inferior to the right macula. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) revealed localized hyperreflectivity of the inner retina and retinal edema [Figure 2]. Fluorescein angiography showed delayed filling of the retinal arteries [Figure 3a] and absence of retinal perfusion in the affected areas in the late phase [Figure 3b].

Figure 1.

Fundus image of the right eye at presentation. Marked disc edema (arrow), retinal artery occlusion with multiple emboli (arrowhead), and localized retinal whitening (asterisk) are seen

Figure 2.

Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography of the right eye at presentation. Localized retinal edema and hyperreflective foci in the inner retinal layers (asterisk) temporal to the right macula are demonstrated

Figure 3.

Fluorescein angiography of the right eye showed (a) delayed filling of the occluded retinal arteries and (b) absence of retinal perfusion in the affected areas in the late phase (asterisk)

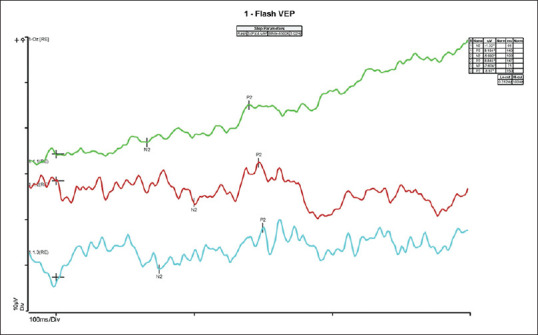

She was immediately administered ocular massage and topical brimonidine eyedrops in the emergency room under the impression of retinal artery occlusion. During admission, she received hyperbaric oxygen therapy twice daily for 5 days. Systemic steroid pulse therapy was not adopted considering the adverse effects of uncontrollable hyperglycemia in the diabetic patients. Dual-antiplatelet treatment was maintained for poststent implantation status. However, her vision did not improve upon discharge. Flash visual-evoked potential was arranged 3 months later for her progressive visual loss after discharge, which showed decreased amplitude and delayed P100 latency [Figure 4]. There was no light perception in the right eye after 1 year due to optic atrophy [Figure 5], even though relatively preserved foveal structures were shown in the SD-OCT [Figure 6].

Figure 4.

Flash visual-evoked potential of the right eye after 3 months showed decreased amplitude and delayed P100 latency

Figure 5.

Fundus image of the right eye after 1 year. Pale disc and retinal arteriolar attenuation are seen with residual emboli (arrowhead) and paramacular retinal scar (arrow)

Figure 6.

Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography of the right eye after 1 year. Retinal inner layer atrophy is seen temporal to the macula (arrow) and the foveal structure is relatively preserved

Discussion

Visual loss after cosmetic facial filler injection is a rare but unacceptable complication. A study reviewed 100 cases of visual loss associated with facial filler injection and revealed that the ophthalmic artery occlusion was the most common pattern, followed by central retinal artery occlusion and branch retinal artery occlusion.[1]

The most commonly accepted mechanism for iatrogenic ophthalmic vascular occlusion is accidental intra-arterial injection followed by subsequent retrograde of the material from the injection site to the ophthalmic artery through the distal anastomosis between the branches.[2] Among all the subcutaneous filler materials, autologous fat was most likely to cause vascular complications because of its larger particle size, followed by hyaluronic acid, and then other fillers such as calcium hydroxyl apatite and PLLA.[1,3] PLLA is a synthetic biodegradable polymer that provides soft-tissue augmentation by stimulating an inflammatory tissue response with subsequent collagen deposition.[4] Comparing to autologous fat (>400 µm) and hyaluronic acid (~400 µm), PLLA has a smaller particle size (40–63 µm).[1,5] However, few cases of vascular complications after PLLA injection have been reported. Park et al. reported the two cases of posterior ciliary artery occlusion; one case had an injection in the eyelid and the other in the glabella.[3] Roberts and Arthurs reported another case of ocular and orbital ischemia after periorbital injection.[6] In addition, Ragam et al. reported ipsilateral ophthalmic and cerebral infarctions after a forehead injection.[7] However, retinal artery occlusion after PLLA injections in the temporal region has not been reported.

According to the previous literature, injection of filler virtually at any location on the face predisposes to blindness because the vascular supply of the face is highly variable and anastomotic.[1] The glabella, nose, nasolabial fold, and forehead are usually considered as the high-risk areas for blindness complications.[1,3] In the presented case, the patient received injections in the temporal region, which is not known to be a common site for visual loss.

Previous studies have reported that loss of vision is irreversible in most cases of ophthalmic vascular occlusion, and to date, no effective treatments have been developed.[8] Conventional treatments for spontaneous central retinal artery occlusion have been applied in the iatrogenic retinal artery occlusion. However, none of them showed favorable results.[1] In our case, despite the prompt and aggressive management of the condition, a good visual outcome was not obtained.

Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and coronary artery disease are known to be risk factors for retinal artery occlusion.[9] As far as we know, no study has compared the incidence of ophthalmic vascular occlusion after cosmetic facial filler injection between patients with and without the aforementioned comorbidities. We consider that patients with the aforementioned comorbidities are more vulnerable to the vascular complications owing to an embolic mechanism. Hence, cosmetic injections should be administered to these patients with extra care and strict patient assessment performed beforehand.

To the best of our knowledge, the retinal artery occlusion after PLLA injection in the temporal region has not been reported previously. Regardless of the type of filler or the injected facial region, practitioners should be cautious of the possible complication of visual loss, especially in patients with a higher risk of vascular complications.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient has given her consent for her images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests of this paper.

References

- 1.Lee JS, Kim JY, Jung C, Woo SJ. Iatrogenic ophthalmic artery occlusion and retinal artery occlusion. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2020:100848. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2020.100848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park SW, Woo SJ, Park KH, Huh JW, Jung C, Kwon OK. Iatrogenic retinal artery occlusion caused by cosmetic facial filler injections. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154:653–62.e651. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park KH, Kim YK, Woo SJ, Kang SW, Lee WK, Choi KS, et al. Iatrogenic occlusion of the ophthalmic artery after cosmetic facial filler injections: A national survey by the Korean Retina Society. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132:714–23. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.8204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schierle CF, Casas LA. Nonsurgical rejuvenation of the aging face with injectable poly-L-lactic acid for restoration of soft tissue volume. Aesthet Surg J. 2011;31:95–109. doi: 10.1177/1090820X10391213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzgerald R, Bass LM, Goldberg DJ, Graivier MH, Lorenc ZP. Physiochemical characteristics of poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) Aesthet Surg J. 2018;38:S13–7. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjy012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts SA, Arthurs BP. Severe visual loss and orbital infarction following periorbital aesthetic poly-(L)-lactic acid (PLLA) injection. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28:e68–70. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3182288e4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ragam A, Agemy SA, Dave SB, Khorsandi AS, Banik R. Ipsilateral ophthalmic and cerebral infarctions after cosmetic polylactic acid injection into the forehead. J Neuroophthalmol. 2017;37:77–80. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Lacerda D. Prevention and management of iatrogenic blindness associated with aesthetical filler injections. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31:e12722. doi: 10.1111/dth.12722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayreh SS, Podhajsky PA, Zimmerman MB. Retinal artery occlusion: Associated systemic and ophthalmic abnormalities. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1928–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]