Abstract

Study Objectives:

To characterize the mandibular anterior teeth crown height as a marker of periodontal changes and bone loss as a side effect of an oral appliance worn for a minimum of 4.5 years.

Methods:

This retrospective study conducted in patients with healthy baseline periodontium recruited participants among consecutive sleep apnea patients treated with an oral appliance between 2004 to 2014. Eligible participants were recalled for a follow-up visit at which a periodontal examination was performed and a lateral cephalogram and dental impressions were obtained. Clinical crown height for mandibular anterior teeth and cephalometric variables were measured and compared before and after treatment. A full periodontal evaluation was performed at the follow-up visit.

Results:

Twenty-one patients enrolled with a mean treatment length of 7.9 ± 3.3 years. For the mandibular anterior teeth, clinical crown height did not change over the evaluated period. At follow-up, all the periodontal assessed variables were within normal limits, with the mean probing depth of 1.4 ± 0.5 mm, recession 0.6 ± 1.1 mm, and clinical attachment loss 0.8 ± 1.0 mm. Compared with baseline, there was a significant proclination of mandibular incisors (mean increase of 5.1 degrees) with the continued use of an oral appliance. Gingival levels were maintained with clinically insignificant changes during the observation period.

Conclusions:

Inclination of the mandibular incisors increases significantly with the use of an oral appliance in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Positional changes in these teeth were not associated with any measured evidence of increase in clinical crown height or gingival recession.

Citation:

Heda P, Alalola B, Almeida FR, Kim H, Peres BU, Pliska BT. Long-term periodontal changes associated with oral appliance treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(10):2067–2074.

Keywords: oral appliances, obstructive sleep apnea, periodontal changes

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Long-term oral appliance wear is associated with significant proclination of lower incisors. The question of whether the resulting dental movements lead to bone loss or compromise the periodontium remains unknown. This study was performed to evaluate the long-term changes in clinical crown height of mandibular anterior teeth as an indicator of periodontal change in patients with obstructive sleep apnea.

Study Impact: We found no increase in clinical crown height or signs of periodontal disease after 7.9 years of oral appliance treatment. Clinically significant proclination and protrusion of the mandibular incisors were observed over this same time period and were not correlated with an increased clinical crown height. These are important findings and reassuring for the patient using an oral appliance regularly.

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is the most common respiratory sleep disorder.1 It is characterized by recurrent partial or complete collapse of upper airway, intermittent hypoxia, and sleep fragmentation. OSA results in serious cardiovascular and metabolic consequences2 and has a significant impact on society, as individuals with OSA often present reduced quality of life, excessive daytime sleepiness, and an increased risk of motor vehicle accidents.3,4 It is estimated that OSA affects 711–961 million middle-aged adults globally.5

Periodontitis is a common disease characterized by alveolar bone loss and gingival recession that is evidenced by an increase in dental crown height. It is estimated that 47% of the adult population have some degree of periodontitis.6 It is well known that the prevalence of periodontal disease among patients with cardiovascular disease is high when they share similar factors of OSA such as obesity, increased age, male sex, hypertension, diabetes, and smoking. Similarly to sleep apnea, one of the mechanisms postulated for this association is driven by oxidative stress and inflammation.7 Recent studies have postulated the association of periodontal disease and OSA,8 having shown a higher prevalence of periodontal disease in patients with OSA. In a systematic review,8 clinical attachment loss (CAL) of tooth-supporting structures was assessed in 2 case-control and 3 cross-sectional studies, and 3 of the studies found significant relationship between periodontitis and OSA.

The mechanism of action of an oral appliance (OA) relies on forward posturing of the mandible and associated soft tissues that improves airway patency during sleep. This improves oxygen saturation and reduces the apnea-hypopnea index, thus improving the signs and symptoms of OSA.9 In addition, OA therapy has been shown to improve inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers.10,11 As OSA is a chronic condition, OA use has to continue through the life of an individual with OSA. This treatment modality typically leads to significant dental and occlusal changes that are correlated to the total duration of OA wear and possibly to the extent of mandibular advancement.12 These side effects have been evaluated using cephalometric studies13–15 and dental cast analysis16–18 that revealed significant overjet and overbite reduction,16,17 as the maxillary teeth retrocline and mandibular teeth procline following extended OA use.13,14

The periodontal consequences of proclination, especially of the mandibular anterior teeth, have been a matter of controversy in orthodontics.19 Some studies20,21 have concluded that gingival recession can follow mandibular incisor proclination, whereas others22–24 did not find such a correlation. Studies have shown that orthodontic tooth movement could result in development or worsening of active periodontal disease.25 In addition, periodontal bone dehiscence is a common side effect with orthodontic treatment, especially in a population more than 30 years old.26 Orthodontic movement has some limitations, and it is well known in the field, that if a tooth is moved too far buccally, it can move out of the alveolar process of the jaw, causing loss of bone on the buccal surface of the teeth. A direct comparison of periodontal outcomes between orthodontic treatment and OA therapy might not be appropriate considering the vast difference in treatment duration, but this is unknown.

Currently, there are no published studies evaluating the long-term periodontal effects of OA therapy. As patients using OA see progressive increases in dental movement with continued treatment,13 an investigation of an association between the excessive mandibular incisor proclination resulting from long-term wear of OA and potential gingival recession and bone loss or accentuated periodontal disease in patients with OSA is warranted. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the anterior teeth crown height changes as a marker for gingival recession/ bone loss in patients with OSA treated with an OA over a long-term period. Designing a retrospective study to answer this question presented 2 inherent challenges. First is selection bias, the common fact that only successfully treated patients would be maintained over a long-term follow-up and unsuccessfully treated patients would change their treatment or be lost to follow-up. Second, the fact that patients with poor periodontal health are contraindicated for OA would limit our population to patients with healthy periodontium at baseline. Within these limitations, our study assessed whether patients using OA long-term and who have dental movements presented increased lower anterior teeth crown height or active periodontal disease.

METHODS

This study consisted of clinical follow-up of patients who had been using OA for a minimum of 4.5 years to treat OSA. Patients were recruited from the University of British Columbia sleep apnea dental clinic and an affiliated private practice.

Eligibility criteria included regular OA use (defined as OA wear for minimum 5 nights per week and at least 4 hours per night) and for a minimum of 4.5 years, at least 19 years of age, and able to understand and communicate in English. Exclusion criteria were patients who refused to participate in the study or declined follow-up records, could not be contacted, stopped using OA or switched to other means of OSA treatment (eg, continuous positive airway pressure), missing or lack of good quality records, previous history of any mucogingival surgery in sextant 5 (division of the dentition that includes the lower front teeth, ie, centrals, laterals, and canines), or presence of a dental implant in the same sextant.

Following recruitment and consent to treatment, eligible patients underwent a thorough clinical exam, and alginate impressions for fabrication of orthodontic study casts and a lateral cephalogram were taken. Patient demographic data and dental exam findings were recorded, and patients were also provided with a questionnaire to self-report adherence. Sleep study results were also obtained from the patients’ charts as provided by their physician throughout the observation period.

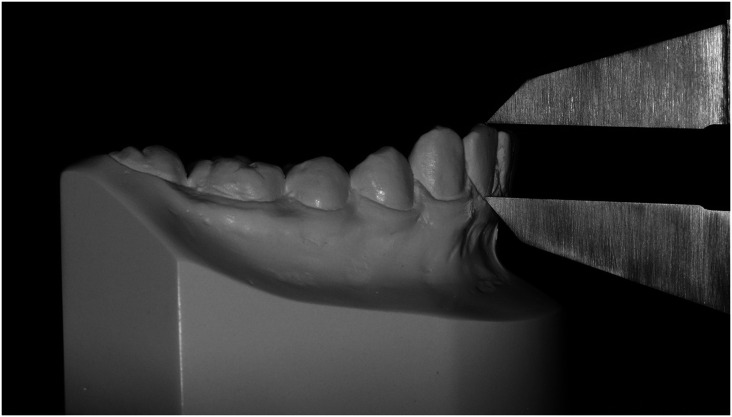

Clinical crown height was measured with a digital caliper (Neiko Tools US) from plaster dental casts at baseline (T1) and follow-up (T2) for all mandibular incisors and canines. The measurement was made at the midbuccal region from the incisal edge or cusp tip for canine to the gingival margin (Figure 1). All measurements were performed by the same operator. Based on the literature of long-term follow-up in a population without any treatment and with normal occlusion,27 the expected increase in clinical crown height of the lower anterior teeth ranges from 1.1 mm on the lower canines to no change on the lower central incisors. Based on these studies and from OA retrospective studies, we expected to recall an average of no more than 20% of patients after 5 years of treatment.

Figure 1. Clinical crown height measurement on study model using digital calipers.

Periodontal health was assessed by a periodontal exam that included measurement of probing pocket depths, recession (including negative recession), CAL, width of attached gingiva, and mobility. Facial gingival margin thickness was evaluated as thick or thin based on visibility of probe when inserted into the gingival sulcus. Gingival color, contour, consistency, and presence of calculus were recorded. Plaque index28 and gingival bleeding index29 were calculated. For probing depths, 3 sites on the facial aspect and 3 on the lingual aspect were measured. Additionally, the periodontal screening and recording system and probe were used to assess the overall periodontal health of the participants and to identify periodontal disease as well as treatment need if any. Periodontal probing and measurements for all the patients were performed by 1 investigator who was trained, and calibrated by a board-certified periodontist.

Lateral cephalograms were obtained in centric occlusion. Baseline (T1) and follow-up (T2) lateral cephalograms were traced digitally (Figure 2) using Dolphin Imaging Software Version 11.7 (Dolphin Imaging and Management Solutions, Chatsworth, CA). Three skeletal and 3 dental variables were measured. Skeletal variables evaluated anteroposterior and vertical skeletal changes and linear and angular dental variables were used to determine the change in mandibular incisor inclination and position from T1 to T2.

Figure 2. Lateral cephalometric tracings of a patient at T1 and T2 with composite analysis.

T1- baseline showing an Sn – GoGn = 36°, FMA of 26°, IMPA = 100°, L1-NB = 31°, L1-NB = 9mm. T2-follow-up visit showing Sn – GoGn = 36°, FMA of 26°, IMPA = 108°, L1-NB = 39°, L1-NB = 11mm, T1 = baseline, T2 = follow-up visit.

The protocol for this retrospective observational study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada (H14-00743).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for demographic data, and normality of clinical characteristics was determined using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Paired t tests were used to compare the means at T1 and T2 for clinical crown height of mandibular incisors and dental cephalometric variables. Skeletal cephalometric data presenting with nonnormal distribution were compared with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

The reproducibility of all cephalometric and dental cast measurements were assessed according to intraclass correlation coefficient by repeating measurements for 11 randomly selected patients 30 days apart. Post-hoc power analysis was done based on the paired t test data from the recruited participants. Correlation among change in clinical crown height, mandibular incisor inclination and position, duration in treatment with OA, and gingival recession used Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Statistical analysis of data was performed with SigmaPlot 14 (Systat Software Inc, San Jose, CA) and SPSS software 22.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

A total of 171 patients who had initiated OA treatment between 2004 and 2014 were screened from 2 centers, resulting in a final sample size of 21 participants who met all eligibility criteria and completed their clinical recall appointment after an average OA treatment duration of 7.9 ± 3.3 years. Patients’ average apnea-hypopnea index at the beginning of the treatment was 16.6. Due to the variability among level 1 to level 4 sleep studies at follow-up, we could not ascertain the efficacy of the OA, other than their physician’s recommendation that the patient continue OA therapy. Reasons for exclusion from the study are summarized in Figure 3. The OAs used in our sample were a mixture of bilateral interlocking and bilateral push designs (15 Klearway, 6 SomnoDent classic at T1; and 5 Klearway, 16 SomnoDent Flex at T2 [Klearway, Vancouver, BC; SomnoMed, Plano, TX]). Average age at T1 and T2 was 49.5 and 57.4 years, respectively, and there was no change in body mass index over the period assessed. The demographic characteristics of the 21 participants before and after OA treatment is summarized in Table 1. Self-reported adherence questionnaires were provided to determine the duration of appliance wear. All patients reported 7 nights per week of OA use except 1 patient who was using the OA for 6 nights per week. Furthermore, all patients reported 7–8 hours of OA wear per night except for one patient who reported 4 hours of OA wear every night. The intraclass correlation coefficient based on 11 randomly selected cases showed excellent reliability for both the cephalometric measurements as well as clinical crown height, ranging from 0.97 to 0.99.

Figure 3. Recruitment flow diagram.

*One patient stopped using the OA due to deterioration of previously compromised periodontal health, while the remaining 38 patients switched to other means of treatment, such as CPAP or surgery independent of the periodontal condition. **Patient had gingival graft before initiating OA therapy. CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure, OA = oral appliance.

Table 1.

Demographic description of the 21 patients at baseline (T1) and after long-term follow-up (T2).

| T1 | T2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 49.5 ± 11.8 | 57.4 ± 12.1 |

| Male (n = 15) (71.4%) | ||

| Female (n = 6) (28.6%) | ||

| Molar/incisor relationship | ||

| Class I | 9 (43%) | 9 (43%) |

| Class II, Division I | 3 (14%) | 1 (4%) |

| Class II, Division II | 9 (43%) | 9 (43%) |

| Class III | None | 2 (10%) |

| Apnea-hypopnea index, events/h | 16.6 | — |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.7 | 26.1 |

On the model measurements, there was negligible change in the clinical crown height between T1 and T2 for lower anterior teeth (–0.02- to 0.17-mm change) with the exception of lower left canine (0.24 mm). The average change in clinical crown height for all mandibular anterior teeth was 0.02 mm, with a standard deviation of 0.57 mm. The mild increase found was not statistically significant and deemed clinically insignificant. Compared to baseline, there was a significant mean decrease in overjet and overbite of 1.24 and 1.02 mm, respectively. All dental cast measurements are further described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Clinical and cephalometric characteristics at baseline (T1) and at follow-up (T2) after an average of 7 years of OA use.

| Mean ± SD | Significance,a P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T2–T1 | ||

| Clinical crown height (mm) | ||||

| Lower left canine | 9.61 ± 1.35 | 9.84 ± 1.54 | 0.24 ± 0.45 | .025 |

| Lower left lateral incisor | 8.24 ± 1.22 | 8.41 ± 1.31 | 0.16 ± 0.47 | .136 |

| Lower left central incisors | 7.86 ± 1.19 | 7.89 ± 1.18 | 0.03 ± 0.58 | .839 |

| Lower right central incisor | 8.14 ± 1.39 | 7.97 ± 1.43 | 0.17 ± 0.60 | .218 |

| Lower right lateral incisor | 8.45 ± 1.06 | 8.49 ± 1.29 | 0.05 ± 0.60 | .730 |

| Lower right canine | 9.95 ± 1.42 | 9.93 ± 1.40 | –0.02 ± 0.42 | .828 |

| Lower incisors onlyb | 8.17 ± 1.21 | 8.19 ± 1.31 | 0.02 ± 0.57 | .781 |

| Overjet (mm) | 3.38 ± 1.65 | 2.14 ± 1.81 | –1.24 ± 1.59 | .001 |

| Overbite (mm) | 3.21 ± 1.40 | 2.19 ± 1.71 | –1.02 ± 0.96 | < .001 |

| Cephalometric variables | ||||

| ANB (degrees) | 4.02 ± 2.50 | 4.46 ± 2.24 | 0.44 ± 0.87 | .032 |

| Sn-GoGn (degrees) | 28.81 ± 6.85 | 29.69 ± 6.72 | 0.88 ± 1.51 | .015 |

| FMA (degrees) | 23.74 ± 5.73 | 24.60 ± 5.60 | 0.85 ± 1.36 | .009 |

| IMPA (degrees) | 95.81 ± 11.26 | 100.95 ± 11.88 | 5.13 ± 3.60 | < .001 |

| L1-NB (mm) | 4.92 ± 2.25 | 6.05 ± 2.42 | 1.13 ± 0.77 | < .001 |

| L1-NB (degrees) | 25.70 ± 7.46 | 31.10 ± 8.73 | 5.41 ± 3.89 | < .001 |

aPaired t test for normally distributed data and Wilcoxon signed-rank test for nonparametric data. bThe mean clinical crown height of the lower incisors only not including the canines n = 83. ANB = angle between point A, nasion, point B; FMA = angle between Frankfort’s horizontal plane and mandibular plane, IMPA = angle between long axis of most proclined mandibular incisor and mandibular plane (Go-Gn), L1-NB = linear measurement from line NB to most labial portion of the crown of mandibular incisor, L1-NB = angle between long axis of mandibular incisor and line from nasion to point B, OA = oral appliance, Sn-GoGn = angle between SN plane and mandibular plane (Go-Gn).

When skeletal cephalometric parameters were compared, mean change from T1 to T2 indicated statistically significant increases in mandibular plane angle and ANB angle (point A, nasion, point B); however, these changes were not considered to be clinically significant in magnitude. Changes for dental variables were highly significant as expected due to increase in the mandibular incisor proclination over time (Table 2).

Pearson’s correlation coefficient showed no significant correlation between change in clinical crown height of mandibular incisors, change in mandibular incisor position and inclination, duration of treatment with the OA, and gingival recession for the mandibular incisors. Duration of treatment was significantly associated with lower incisor proclination (P = .001) and protrusion (P = .002). However, the duration of treatment was not correlated with gingival recession or changes in clinical crown height (r [19] = .04, P > 0.5).

Overall, participants presented excellent oral hygiene. The findings from the periodontal evaluation and periodontal screening and recording method demonstrated that the probing depths ranged from 1 to 3 mm. No patient had periodontal screening and recording scores greater than 2 for any sextant of the mouth. The mean plaque index28 and mean gingival bleeding index29 were within normal ranges for all patients. CAL ranged from 0 to 6 mm descending order with 1 site of 1 patient having CAL of 6 mm (Table 3). This could be interpreted as the long-term OA treatment not causing or increasing bone loss in the lower anterior region or periodontal disease.

Table 3.

Periodontal characteristics for mandibular anterior teeth at follow-up (T2).

| Parameter | Mean | Standard Deviation | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probing depth (mm) | 1.36 | 0.52 | 1–3 |

| Recession (mm) | –0.59 | 0.59 | –3–4 |

| Clinical attachment loss (CAL) (mm) | 0.75 | 1.04 | 0–6 |

| Plaque index (Silness and Loë) | 0.44 | 0.26 | 0.04–1.04 |

| Bleeding index (%) (Ainamo and Bay) | 4.14 | 5.02 | 0–19.13 |

DISCUSSION

Proclination of mandibular incisors is a common side effect of long-term treatment with OA, though the extent to which this may result in an increase in crown height of lower anterior teeth is unknown. We found that in a sample of 21 adult patients with OSA, routine OA use for more than 7 years was not associated with increased crown height or poor periodontal status. Significant increases in mandibular incisor inclination of greater than 5 degrees were observed; however, there was no significant change in the average clinical crown height of mandibular anterior teeth, as would be expected if gingival recession or bone loss had occurred over this same observation period.

It is important to note that, generally, patients with poor periodontal health or active periodontal disease are not eligible for OA treatment. There is a concern that the use of an appliance covering the dental gingival margin and dental movements could make patients more prone to or accelerate periodontal disease. As our study focused on patients with OSA, possibly increased inflammatory markers could have made them more prone to periodontal disease. The patients assessed in the current study all showed good oral hygiene and a lack of periodontal disease despite long-term use of OA. It is interesting to hypothesize the possible mechanisms of why, despite dental movement and continuous overnight coverage of the dental gingival borders, there was no clinical expression of periodontal disease. One could hypothesize that with a successful OSA treatment, there is a decrease in overall systemic inflammation. With the decrease in the inflammation, and despite their ages, patients were protected or less prone to periodontal disease and therefore did not develop any recession and were able to maintain a great oral health status.

Periodontal breakdown can be a result of poor hygiene alone, not necessarily due to change in incisor inclination and position. We believe the selection criteria of patients for OA treatment should include an absence of active periodontal disease, and the importance of adequate oral hygiene reinforced at routine follow-up visits.

The correlation analysis was statistically significant for the length of OA treatment and change in incisor inclination. However, we observed a great deal of individual variation among patients. This is also in agreement with the long-term findings reported by Pliska et al.12 The time-related and progressive dental changes in the form of reduction in overjet and overbite, as well as change in maxillary and mandibular incisor inclination, have also been reported.13,14 Despite the correlation between proclination and length of OA use, these did not correlate with increased clinical crown height as an indicator of periodontal disease.

The periodontal outcomes of lower incisor proclination have been previously discussed in the orthodontic literature.19 Some studies20,21 have concluded that gingival recession can follow mandibular incisor proclination, whereas others did not.22–24 Thin cortical bone on the labial aspect, minimal or absent attached gingiva, and mandibular incisors with labially prominent roots are factors often linked to recession.30 Two systematic reviews19,31 have attempted to answer this question of an association between orthodontic labial movement of mandibular incisors and gingival recession. Both pointed toward the low quality and variable methodology of the included studies and concluded that there is either no association or weak association between orthodontic proclination and gingival recession. However, due to low level of evidence this statement should be interpreted with caution. The dental changes in the present cohort occurred over a long period (> 7 years), whereas changes during orthodontic treatment occur over a shorter period of approximately 24 months. Therefore, direct comparison of the present findings to proclination occurring over the course of orthodontic treatment may not be appropriate. It is important to state that dental movements as a side effect of OA are not predictable, and teeth could be moved out of their bony support of the alveolar process of the jaw. This information is highly important for clinicians: If there is bone loss associated with dental movement, OA therapy should be discontinued.

The design of the OA is often seen as a possible cause of differences in side effects. Although no studies have compared periodontal side effects, there are known studies comparing different OA designs and dental proclination. Based on the current literature, an OA that does not cover the lingual surface of lower incisors may cause an increase in crowding.32 As previously described, an increase in crowding could relate to an increase in periodontal disease. In the current study, we used different appliances that cover all lingual surfaces of lower anterior teeth. In terms of the amount of dental side effects, studies have shown that the amount of proclination of anterior teeth is correlated to the length of OA use and not to the OA design.33

One potential confounder for this study is the natural progression of the periodontium attributed to the effect of periodontal diseases in a typical middle-age population and periodontal changes in healthy individuals over time. None of our patients had any history of periodontal disease and they all presented with healthy periodontal tissues and meticulous oral hygiene. Ship et al34 in a 10-year follow-up of the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging evaluated 95 healthy participants between 29 and 76 years of age. They concluded that the periodontal attachment loss observed was not dependent on a person’s age when no generalized changes were taking place.34 In a longitudinal follow-up spanning over 40 years in individuals with normal occlusion, Massaro et al27 evaluated changes in clinical crown height at 13, 17, and 60 years of age. They found an increase that ranged from 1.1 mm in the lower canines to no change in the lower centrals. They speculated that the clinical crown height for mandibular central incisors did not change significantly (0.02 mm reduction), because the increase in clinical crown height was similar to the extent of incisal wear.27 Our data showing stable clinical crown height, despite progressive labial movement of mandibular anterior teeth, are an important finding and certainly reassuring for patients using OA regularly.

The results of the present study are limited by the retrospective design and the potential for selection bias in the patient sample. Also, as a negative study and with the bias of publications toward negative results, this trial has higher chances of being criticized. Compliant patients were more likely to respond to phone calls, be recruited to studies, use their appliances, and possibly had excellent oral health. Patients who may possibly have experienced periodontal disease were more likely to have discontinued therapy, although only 1 out of the 39 patients who stopped using the OA reported it was due to deterioration of previously compromised periodontal health. The remaining 38 patients switched to other means of treatment such as continuous positive airway pressure or surgery independent of the periodontal condition. Moreover, out of the 23 patients who declined to participate, most reported miscellaneous reasons (eg, too busy, transport issues, poor overall medical condition, lack of interest to participate). None reported as a reason that OA caused them periodontal disease. It is important to note that patients were recruited from 2 sites, 1 university-based and 1 a private practice. There was no difference between the groups, which showed no bias, at routine follow-up, from the academic setting potentially being the source of great oral hygiene. Another drawback was that the periodontal status of patients at T1 was unknown, and the final sample size of 21 patients was relatively small owing to the exclusion of a greater number of patients than we initially anticipated. Although periodontal status was unknown at T1, clinical crown height is a good marker of periodontal health and it was stable over the course of the treatment. Another consideration regarding our finding of no change in clinical crown height from T1 to T2 is that any increase in clinical crown height may have been offset by the attrition of incisal edges of mandibular anterior teeth. This can possibly incorporate methodological error that is difficult to quantify in a retrospective study. We did not find significant gingival recession among the study participants; however, this could have been controlled for by periodic longitudinal follow-up or a prospective study design. Considering all the limitations mentioned, our study presents the best available evidence on periodontal health outcomes with long-term OA therapy in patients with OSA.

Future studies that allow for multiple longitudinal observation periods would also allow for an investigation of the time scale of any periodontal changes. A larger sample size may improve the generalizability of the results, however, due to many variables related to OSA treatment and patient adherence, this will be most challenging. Thin gingival tissue has often been implicated as a risk factor for gingival recession with incisor proclination, and a larger sample may also allow for comparison between groups with different gingival biotypes.

It is concluded that in a cohort of patients with OSA, there was no increase in clinical crown height over a long-term use of OA. There were no signs of periodontal disease or bone loss observed after more than 7.9 years of OA treatment. Clinically significant amounts of proclination and protrusion of the mandibular incisors were observed over this same time period and were not correlated to an increase clinical crown height.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors have seen and approved the manuscript. Work for this study was performed at the University of British Columbia, Faculty of Dentistry. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CAL,

clinical attachment loss

- OA,

oral appliance

- OSA,

obstructive sleep apnea

- T1,

baseline

- T2,

follow-up visit

REFERENCES

- 1. Malhotra A , White DP . Obstructive sleep apnoea . Lancet. 2002. ; 360 ( 9328 ): 237 – 245 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jordan AS , McSharry DG , Malhotra A . Adult obstructive sleep apnoea . Lancet. 2014. ; 383 ( 9918 ): 736 – 747 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Terán-Santos J , Jiménez-Gómez A , Cordero-Guevara J ; Cooperative Group Burgos-Santander . The association between sleep apnea and the risk of traffic accidents . N Engl J Med. 1999. ; 340 ( 11 ): 847 – 851 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kushida CA , Morgenthaler TI , Littner MR , et al . Practice parameters for the treatment of snoring and obstructive sleep pnea with oral appliances: an update for 2005 . Sleep. 2006. ; 29 ( 2 ): 240 – 243 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Benjafield AV , Ayas NT , Eastwood PR , et al . Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: a literature-based analysis . Lancet Respir Med. 2019. ; 7 ( 8 ): 687 – 698 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eke PI , Dye BA , Wei L , Thornton-Evans GO , Genco RJ . Prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010 . J Dent Res. 2012. ; 91 ( 10 ): 914 – 920 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sanders AE , Essick GK , Beck JD , et al . Periodontitis and sleep disordered breathing in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos . Sleep. 2015. ; 38 ( 8 ): 1195 – 1203 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Al-Jewair TS , Al-Jasser R , Almas K . Periodontitis and obstructive sleep apnea’s bidirectional relationship: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Sleep Breath. 2015. ; 19 ( 4 ): 1111 – 1120 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ferguson KA , Cartwright R , Rogers R , Schmidt-Nowara W . Oral appliances for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea: a review . Sleep. 2006. ; 29 ( 2 ): 244 – 262 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fernández-Julián E , Pérez-Carbonell T , Marco R , Pellicer V , Rodriguez-Borja E , Marco J . Impact of an oral appliance on obstructive sleep apnea severity, quality of life, and biomarkers . Laryngoscope. 2018. ; 128 ( 7 ): 1720 – 1726 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baessler A , Nadeem R , Harvey M , et al . Treatment for sleep apnea by continuous positive airway pressure improves levels of inflammatory markers—a meta-analysis . J Inflamm (Lond). 2013. ; 10 ( 1 ): 13 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pliska BT , Nam H , Chen H , Lowe AA , Almeida FR . Obstructive sleep apnea and mandibular advancement splints: occlusal effects and progression of changes associated with a decade of treatment . J Clin Sleep Med. 2014. ; 10 ( 12 ): 1285 – 1291 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hamoda MM , Almeida FR , Pliska BT . Long-term side effects of sleep apnea treatment with oral appliances: nature, magnitude and predictors of long-term changes . Sleep Med. 2019. ; 56 : 184 – 191 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fransson AMC , Benavente-Lundahl C , Isacsson G . A prospective 10-year cephalometric follow-up study of patients with obstructive sleep apnea and snoring who used a mandibular protruding device . Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2020. ; 157 ( 1 ): 91 – 97 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Almeida FR , Lowe AA , Sung JO , Tsuiki S , Otsuka R . Long-term sequellae of oral appliance therapy in obstructive sleep apnea patients: Part 1. Cephalometric analysis . Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006. ; 129 ( 2 ): 195 – 204 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marklund M , Franklin KA , Persson M . Orthodontic side-effects of mandibular advancement devices during treatment of snoring and sleep apnoea . Eur J Orthod. 2001. ; 23 ( 2 ): 135 – 144 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fritsch KM , Iseli A , Russi EW , Bloch KE . Side effects of mandibular advancement devices for sleep apnea treatment . Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001. ; 164 ( 5 ): 813 – 818 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Almeida FR , Lowe AA , Otsuka R , Fastlicht S , Farbood M , Tsuiki S . Long-term sequellae of oral appliance therapy in obstructive sleep apnea patients: Part 2. Study-model analysis . Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006. ; 129 ( 2 ): 205 – 213 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aziz T , Flores-Mir C . A systematic review of the association between appliance-induced labial movement of mandibular incisors and gingival recession . Aust Orthod J. 2011. ; 27 ( 1 ): 33 – 39 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Årtun J , Krogstad O . Periodontal status of mandibular incisors following excessive proclination. A study in adults with surgically treated mandibular prognathism . Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1987. ; 91 ( 3 ): 225 – 232 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yared KFG , Zenobio EG , Pacheco W . Periodontal status of mandibular central incisors after orthodontic proclination in adults . Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006. ; 130 ( 1 ): 6.e1 – 6.e8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Melsen B , Allais D . Factors of importance for the development of dehiscences during labial movement of mandibular incisors: a retrospective study of adult orthodontic patients . Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005. ; 127 ( 5 ): 552 – 561 , quiz 625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Djeu G , Hayes C , Zawaideh S . Correlation between mandibular central incisor proclination and gingival recession during fixed appliance therapy . Angle Orthod. 2002. ; 72 ( 3 ): 238 – 245 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Morris JW , Campbell PM , Tadlock LP , Boley J , Buschang PH . Prevalence of gingival recession after orthodontic tooth movements . Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2017. ; 151 ( 5 ): 851 – 859 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Singh DP . Factors associated with orthodontic tooth movement in periodontally compromised patients . Open J Stomatol. 2015. ; 5 ( 11 ): 268 – 279 . [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jäger F , Mah JK , Bumann A . Peridental bone changes after orthodontic tooth movement with fixed appliances: a cone-beam computed tomographic study . Angle Orthod. 2017. ; 87 ( 5 ): 672 – 680 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Massaro C , Miranda F , Janson G , et al . Maturational changes of the normal occlusion: a 40-year follow-up . Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2018. ; 154 ( 2 ): 188 – 200 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Löe H . The Gingival Index, the Plaque Index and the Retention Index Systems . J Periodontol. 1967. ; 38 ( 6 ): 610 – 616 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ainamo J , Bay I . Problems and proposals for recording gingivitis and plaque . Int Dent J. 1975. ; 25 ( 4 ): 229 – 235 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dorfman HS . Mucogingival changes resulting from mandibular incisor tooth movement . Am J Orthod. 1978. ; 74 ( 3 ): 286 – 297 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Joss-Vassalli I , Grebenstein C , Topouzelis N , Sculean A , Katsaros C . Orthodontic therapy and gingival recession: a systematic review . Orthod Craniofac Res. 2010. ; 13 ( 3 ): 127 – 141 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Norrhem N , Nemeczek H , Marklund M . Changes in lower incisor irregularity during treatment with oral sleep apnea appliances . Sleep Breath. 2017. ; 21 ( 3 ): 607 – 613 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vezina JP , Blumen MB , Buchet I , Hausser-Hauw C , Chabolle F . Does propulsion mechanism influence the long-term side effects of oral appliances in the treatment of sleep-disordered breathing? Chest. 2011. ; 140 ( 5 ): 1184 – 1191 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ship JA , Beck JD . Ten-year longitudinal study of periodontal attachment loss in healthy adults . Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996. ; 81 ( 3 ): 281 – 290 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Alsulaiman AA, Kaye E, Jones J, Cabral H, Leone C, Will L, Garcia R. Incisor malalignment and the risk of periodontal disease progression. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2018 Apr;153(4):512–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]