Abstract

Assessing the cost of vaccine preventable diseases (VPD) surveillance is becoming more important in the context of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) funding transition, since GPEI support to polio surveillance helped the incremental building of VPD surveillance systems in many countries, including low income countries such as Nepal. However, there is limited knowledge on the cost of conducting VPD surveillance, especially the national cost for surveillance of multiple vaccine-preventable diseases. The current study sought to calculate the economic and financial costs of Nepal’s comprehensive VPD surveillance systems from July 2016 to July 2017. At thecentral level, all surveillance units were included in the sample. At sub-national level, a purposive sampling strategy was used to select a representative sample from locations involved in conducting surveillance. The sub-national sample costs were extrapolated to the nationwide VPD surveillance system. Nepal’s total annual economic cost of VPD surveillance was USD 4.81 million or USD 0.18 per capita, while the total financial cost was USD 4.38 million or USD 0.16 per capita. Government expenditures accounted for 56% of the total economic cost, and World Health Organization accounting for 44%. The biggest cost driver was personnel accounting for 51% of the total economic cost. WHO supported trained surveillance personnel through donor funding, mainly from Global Polio Eradication Initiative. As a polio transition priority country, Nepal will need to make strategic choices to fully self-finance or seek full donor support or a mixed-financing model as polio program funding diminishes.

Keywords: Vaccine preventable diseases, Surveillance, Cost, Polio transition, Nepal, Country study

1. Introduction

Surveillance for vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs) provides continuous, long-term evidence-based information that allows for the timely detection and response to VPD and the monitoring of impact of national immunization programs. In many developing countries, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) funds an extensive polio surveillance program through a cadre of trained personnel and a global laboratory network. These GPEI-funded polio networks have also often supported surveillance for VPDs other than polio, although the extent and continuity of such support has varied across countries [1]. With wild poliovirus getting closer to eradication and having been eliminated in five of six WHO regions, this VPD surveillance network is at risk of losing its primary funding stream (i.e., GPEI) and may suffer an attrition of performance quality if funding is not replaced [2]. In some countries where GPEI has already stopped funding, national governments and/or other donors (e.g. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance) have stepped up, but one challenge is that due to different funding streams for different diseases and the use of shared resources across different VPD surveillance systems, it is unknown how much a comprehensive VPD surveillance system costs at country-level [3].

With the primary funding for VPD surveillance disappearing in polio priority countries, there is an urgency to advocate for resources to maintain VPD surveillance to inform the immunization program. The literature contains limited evidence on the cost to a country to run VPD surveillance systems. One review found only 11 articles; it found that human resources were the biggest cost driver in a majority of the studies, though many of these studies looked at the cost of only one or a few diseases and not surveillance for all VPDs in the country [4]. One study analyzed 63 Comprehensive Multi-Year Plans (cMYPs) from low and middle-income countries and found countries spent a median of USD 406,158 (range USD 1098–21,644,770) on VPD surveillance. However, this analysis was unable to capture all VPD surveillance expenditures as no country included costs for all components of surveillance, and it is unclear what data is gathered to fill in the cMYP in each country [5]. In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) held a meeting of experts to discuss how to help countries cost VPD surveillance; it was recommended that more country case studies calculating the cost of a more comprehensive set of VPDs be conducted to inform development of global guidance and a tool to help countries cost VPD surveillance [5].

In Nepal, active case-based surveillance was initially built to conduct Acute Flaccid Paralysis (AFP) surveillance in 1998. Other diseases, including measles, Japanese encephalitis, and neonatal tetanus were incrementally added onto this surveillance system. This system has received considerable financial support from Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) since inception. With GPEI funding being shifted to the remaining polio endemic or high-risk countries, Nepal faces a challenge to the sustainability of this surveillance system, on which the country relies to ensure complete case detection, case investigations and timely response measures.

Nepal has generally maintained VPD surveillance indicators above global performance standards set by WHO [6], [7]. This study aimed to produce a country-level estimate of the economic and financial costs for conducting VPD surveillance. It analyzed the costs by inputs and administrative levels to identify the key cost drivers. This would provide critical information on resource needs to decision makers when developing strategy to sustain VPD surveillance in Nepal, and could instruct other countries too, facing similar challenges.

2. Method and assumptions

2.1. Background on Nepal’s VPD surveillance structure

Nepal’s VPD surveillance systems are composed of three parts, with some functional overlap. (1) Integrated Health Management Information Section (iHMIS). This includes the aggregated surveillance reports for a group of VPDs and non-VPDs. VPDs that are included are diseases targeted for eradication or elimination (poliovirus/ AFP), neonatal tetanus, measles and rubella) as well as others like Japanese encephalitis, diphtheria, pertussis, hepatitis B, mumps, typhoid etc. Suspected cases of a disease syndrome are detected by health workers at any of the health facilities nation-wide, reported to the relevant district health officer, and then to the iHMIS system monthly. There are no laboratory testing components integrated into this system. It is led by the Department of Health Services (DoHS) in the Ministry of Health and Population (MOHP).

(2) Early Warning Report System (EWARS). This is a hospital-based passive aggregate reporting system in 81 of the 308 hospitals in Nepal. Routine reporting is weekly, with immediate reporting for outbreaks. The purpose is to complement iHMIS by quickly identifying an increase in outbreak-prone diseases. While EWARS tests for influenza virus through its sentinel sites, it does not perform case-based epidemiologic investigations or systematic laboratory testing for confirming reported cases of other VPDs for which vaccines have been deployed in the national immunization program. It is run by the Epidemiology and Disease Control Division (EDCD) of DOHS/MOHP.

(3) Active VPD surveillance system. This is case-based and laboratory supported for selected VPDs for which vaccines have been deployed through the national immunization program. It targets a specific set of VPDs and accompanying syndromes based on the global and regional VPD elimination/eradication/control goals and new vaccine introduction needs including poliovirus/AFP, measles, rubella, congenital rubella syndrome (CRS), neonatal tetanus, Japanese encephalitis, invasive bacterial diseases or IBD (e.g. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Hemophilus influenzae, Neisseria meningitidis) and rotavirus. This system is managed by the Child Health and Immunization Services (CHIS) Section of DOHS/MOHP, and the Nepal WHO Country Office through the Immunization Preventable Disease (WHO-IPD) program.

2.2. Key VPD surveillance activities

On the side of HIMS and EWARS, VPD surveillance activities mainly consisted of aggregated case reporting through national disease surveillance system. On the active VPD surveillance system side, healthcare workers at surveillance sites (selected health service delivery points in public and private sectors) report suspected cases to surveillance medical officers (SMOs) at WHO field office and officers at district public health offices. SMOs visit health facilities periodically. During their visit, they undertake active surveillance for VPDs, investigate cases, ensure collection of specimens for laboratory testing, ship specimens and conduct capacity building workshops. Laboratories test the sample to confirm the cases and provide feedback on the laboratory results. Data on investigated individual cases, are entered into an electronic information system, linked up with laboratory results and analyzed. This information is used by CHIS to take further public health action as needed.

The SMOs are part of a WHO-built polio-funded network, coordinated by WHO - IPD at Kathmandu. Together, they support the country’s VPD case-based surveillance system. The SMO network (15 SMOs in 11 field offices) is embedded in the provinces and districts, and the SMOs provide technical support for vaccine preventable disease surveillance, immunization, emergency response, and various other activities as needed, to their government counterparts. The WHO-IPD central office oversees general coordination, technical assistance and management of the WHO-supported surveillance network in collaboration with the government. It also leads on generating and disseminating surveillance data products as well as monitoring and evaluation of the system.

2.3. Cost estimation methods

To analyze the total economic and financial costs for the VPD surveillance system, one needs to account for the components of an effective surveillance system. Activities of an effective system can include case detection (passive and active surveillance), reporting; investigation and confirmation of case; specimen collection and handling; laboratory confirmation including quality assurance of laboratory procedures, data management and analysis; and communication [8].

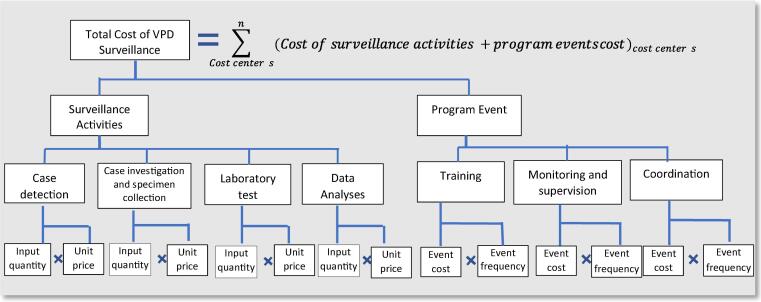

The costing exercise uses the ingredient approach to estimate the value of resources (Fig. 1). Input here means the resources that are used to implement activities. The ingredient approach uses formula 1:

| (1) |

Fig. 1.

Costing structure.

where i is a specific input. One of the challenges in estimating the cost by input is that some inputs are shared by activities that are not relevant to VPD surveillance. This is called shared resource. A typical shared resource is personnel. To extract the usage of shared resources for VPD surveillance activities, interviewees were asked to estimate the share of the workload for a VPD activity for the resource in question. This is used as the distribution key to extract the cost for VPD surveillance (formula 1a).

| (1a) |

A cost center is a unit to which the costs are charged. Each surveillance unit was considered a cost center. For a specific cost center n, the total cost of surveillance activities is the total value of surveillance activities conducted by that cost center for all VPDs covered by that cost center (formula 2). j represents a VPD.

| (2) |

The total surveillance activity cost is the sum of the surveillance activity cost for each cost center in the country (formula 3)

| (3) |

To improve the effectiveness and efficiency of surveillance, resources are needed to conduct programmatic activities, such as training, monitoring and supervision, coordination, and data dissemination. These activities often take the form of an event. Events were defined as meetings, such as surveillance quality control meetings, surveillance management meetings, and trainings. Given the assumption that the programmatic activities are carried out in an integrated way through specific missions, the programmatic activity cost is calculated by in formula 4. Missions include activities such as active surveillance visits for case searching, participation in meetings and trainings; case investigation and sample collection.

| (4) |

The total cost of VPD surveillance system is then calculated by formula 5.

| (5) |

Table 1 lists the resource needs for each category of activities. When a resource is shared among several functions or activities, a distribution key was estimated and calculated based on the share of that resource used for surveillance activities.

Table 1.

Resources needed by surveillance activity.

| Recurrent costs Activities |

Personnel | Travel | Vehicle maintenance | Office supplies | Information technology maintenance | Building overhead | Specimen shipment | Lab supplies/test kits | Lab equipment maintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case detection, registration and reporting | X | X | X | ||||||

| Case investigation | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Specimen collection and handling | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Laboratory test | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Data management and analysis | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Communication | X | X | |||||||

| Active case research | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Capital costs Activities |

Building construction | Vehicle purchase | Lab equipment purchase | ||||||

| Case detection, registration and reporting | X | ||||||||

| Case investigation | X | ||||||||

| Specimen collection and handling | X | ||||||||

| Laboratory testing | X | ||||||||

| Data management and analysis | X | ||||||||

| Communication | |||||||||

| Active case search | |||||||||

Note: the content of this table was developed based on the Global Strategy on Comprehensive Vaccine-Preventable Disease Surveillance [8] and discussions with Nepal VPD surveillance experts.

2.4. Data collection

This was a retrospective costing study of VPD surveillance with primary data collection on surveillance resource utilization and costs over one year. The study took the perspective of the public health sector, and included costs related to the VPD portion of the three surveillance systems mentioned above.

The field data collection was done between March-August 2018. The reference year for the costing period was set from 15 July 2016 to 14 July 2017 in accordance with the country’s last completed fiscal year cycle. Data was collected through a series of questionnaires tailored to the activities conducted at the central, region/province, district, and health facility levels. The questionnaires were translated into Nepalese, pilot tested, and independent data collectors were trained on the standard operating procedure.

2.5. Sampling

Units that participated in VPD surveillance were grouped at central and subnational levels for which different sampling strategies were applied.

Central level: all relevant costing centers were included in the study: i.e.: the WHO-IPD central office in Kathmandu; the federal central unit (FU) composed of the CHIS , EDCD, and iHMIS; and all four VPD surveillance laboratories that were functioning in the country during the costing period. Two of these laboratories supported measles, rubella and Japanese encephalitis testing. Two other laboratories are for rotavirus and IBD surveillance respectively. Laboratories outside of Nepal, such as the ones in Thailand for poliovirus testing and molecular testing for measles and rubella, are not included in this study.

Subnational level: the surveillance sites included WHO-IPD field offices (FOs), government district health offices (DHOs) and surveillance sites (SS) at health service delivery points (health facilities (HF) and hospitals). SS are further divided in to two types: reporting units (RU) and informing units (IU). An RU is expected to send weekly reports irrespective of a VPD case occurrence and an immediate report when a case is detected. An IU only reports the suspected cases when detected but are not expected to send in weekly reports when no case is detected. Both RU and IU work with a SMO for case investigation, sample collection and shipment. SMOs validate the data collected as part of the case investigation and facilitate sample shipment with quality checks on documentation and reverse cold chain maintenance. SMOs visit all SS for active search of cases periodically, with the frequency of active search depending on the expected case load.

For sample selection, the subnational sites were stratified by province and ecological zones (hill, plains (Terai regions), mountain) with all seven provinces having at least one district included in the sample and all ecologic zones being represented. WHO-IPD has 1–2 FOs per province and one FO in Kathmandu, with each FO covering an average of 5–7 districts (except for the Kathmandu SMO who covers 3 districts). We chose one FO per province plus the FO in Kathmandu, resulting in the selection of 8 of 11 FOs (Fig. 2). Within each selected FO’s catchment area, we chose one DHO purposively to diversify ecological zones. In the final sample, there were three DHOs for hill, three for terai, and two for mountain zone. Within each district, we randomly selected three SS - two RU and one IU each. The selected SS had to satisfy two criteria: (a) administrative and financial records for last fiscal year would be available in the health facility, and (b) the health facility in-charge or the surveillance focal point has been in the position since at least the last financial year. This was done to ensure availability of records and institutional memory of surveillance related information. If a selected SS did not satisfy these conditions, another SS was randomly chosen to replace it.

Fig. 2.

Location and districts covered by WHO field offices. (Note: The boundaries shown in the map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the authors concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. SMO – surveillance medical officer.

In total, 48 units were included in this study (100% participation rate). The final sample is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Total number of VPD surveillance related units vs. sample size.

| System | Cost centres | Total number | Sample number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central | FU (CHISS, EDCD, iHMIS) | 3 | 3 |

| WHO IPD | 1 | 1 | |

| Laboratories doing VPD surveillance | 4 | 4 | |

| Sub-national | FO | 11 | 8 |

| DHO | 77 | 8 | |

| HF included as surveillance sites | IU: 581 | IU: 3 | |

| RU: 551 | RU: 9 | ||

| Hospitals included as surveillance sites | IU: 167 | IU: 4 | |

| RU: 141 | RU: 8 | ||

Notes: DoHS – Department of Health Service; HF – Health Facility; DHO- District Health Office; FU – Federal Units ; CHISS – Child Health and Immunization Service Section; EDCD - Epidemiology and Disease Control Division; iHMIS- Integrated Health Management Information Section; WHO – World Health Organization; Lab – Laboratory; FO- WHO field office; MO – Main office; IU – Informing unit; RU – Reporting unit.

Extrapolation strategy. At the central level, as all main units were costed, there was no need to extrapolate. At the sub-national level, different extrapolation strategies were used for different cost centers. For the WHO-IPD FO, for the provinces with two FOs, the cost for the selected one was used as proxy for the unselected one in the same province. For DHOs, selected DHOs were grouped by ecological zones. Nepal has 21 terai districts, 41 hill districts, and 15 mountain districts. In our sample, there were 3 terai districts, 3 hill districts, and 2 mountain districts. The VPD surveillance cost of the selected DHOs was averaged by ecological zone and applied to all remaining DHOs in the same ecological zone. At the health service delivery level, there are 1440 surveillance sites that participate in VPD surveillance, composed of 692 RUs and 748 IUs. The study sample included 24 SS (17 RUs, 7 IUs). As the activity cost for hospitals could be different than that for other health facilities, the average cost for VPD surveillance activities was calculated for IU and RU by hospitals and these other health facilities. These average costs were multiplied by the total number of units in their respective categories to obtain the nationwide cost at the health service delivery level.

Annualization of capital assets cost. We assumed that capital equipment depreciates over its lifetime. The straight–line depreciation approach was used to calculate the annual cost of capital equipment (formula 6).

| (6) |

When a capital equipment was still on service beyond its useful life years (ULY), the annual depreciation cost of the exceeding years was recorded as zero. When the purchasing price was missing for an asset, the average cost of similar assets (i.e. same category, same brand) in other cost centers was used.

For WHO-IPD assets (equipment and vehicles), the information on ULY was based on the information provided by WHO’s Global Management System when data were available. When data were not available, WHO’s country officers’ recommendations were used. For government assets, the information on ULY was based on government’s officers’ recommendation.

Economic and Financial Costs. Economic costs measure the opportunity cost of all resources used to conduct surveillance activities in a given period. Financial costs measure the financial outlays in a given period. The components of economic and financial costs by input are listed in Table 3. All costs presented in the result section are economic costs, unless specified as a financial cost.

Table 3.

Components of economic and financial costs.

| Cost category | Inputs | Economic | Financial |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrent | Equipment Maintenance | √ | √ |

| Event | √ | √ | |

| Personnel: Salary | √ | √ | |

| Laboratory supplies | √ | √ | |

| Maintenance of vehicle | √ | √ | |

| Mission expense | √ | √ | |

| Office functioning | √ | √ | |

| Sample shipment | √ | √ | |

| Capital | Vehicle asset | √ | √* |

| Laboratory equipment | √ | √* | |

| Office equipment | √ | √* | |

| Office space | √ | ||

Note: * only if the asset was purchased between July 2016 and July 2017.

Exchange rate. All cost information was collected in Nepalese Rupee (NRP). According to World Bank data, NRP varied between 104 and 107 NRP for one USD in 2016–2017 period [9]. We took the median of 105 NRP for one USD as the currency conversion rate.

Ethics. This study was approved by Nepal Health Research Council; written informed consent was obtained from all interviewees.

3. Results

Nepal’s total cost of VPD surveillance from July 2016 to July 2017 was approximately USD 4.81 million, or USD 0.18 per capita. The total financial cost was USD 4.38 million for the same period, or USD 0.16 per capita (Table 4). WHO’s cost contribution was USD 2.13 million (44%), and the government’s cost contribution was USD 2.69 million (56%). By administrative level, the central level’s cost for VPD surveillance was USD 1.25 million (26%), while at subnational level, it was USD 3.56 million (74%).

Table 4.

Total VPD surveillance economic and financial costs by surveillance units and by inputs.

| Unit type | Economic cost |

Financial cost |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost in USD | In % of total cost | Cost in USD | In % of total cost | |

| Central-Laboratory | 187,574 | 4% | 175,074 | 4% |

| Central – Federal unit | 210,251 | 4% | 200,407 | 5% |

| Central – WHO IPD cenral office | 855,385 | 18% | 719,802 | 16% |

| Subnational – District health office | 1,103,633 | 23% | 912,185 | 21% |

| Subnational – Field office | 1,271,918 | 26% | 1,188,267 | 27% |

| Subnational – Health facilities and hospitals | 1,184,155 | 25% | 1,184,155 | 27% |

| Total | 4,812,915 | 100% | 4,379,891 | 100% |

| Total population in 2016–2017 | 27,448,057 | |||

| Total cost per capita | 0.18 | 0.16 | ||

| Input | Economic cost |

Financing cost |

||

| Cost in USD | In % of total cost | Cost in USD | In % of total cost | |

| Personnel: salary | 2,469, 858 | 51.3% | 2,469, 858 | 56.4% |

| Mission | 882,877 | 18.3% | 882,877 | 20.2% |

| Event organisation | 772,402 | 16.0% | 772,402 | 17.6% |

| Office space | 168,701 | 3.5% | – | – |

| Office equipment | 148,818 | 3.1% | – | – |

| Office functioning | 117,969 | 2.5% | 117,969 | 2.7% |

| Vehicle assets | 99,458 | 2.1% | – | – |

| Laboratory supplies | 65,626 | 1.4% | 65,626 | 1.5% |

| Maintenance of vehicle | 52,717 | 1.1% | 52,717 | 1.2% |

| Sample shipment | 17,080 | 0.4% | 17,080 | 0.3% |

| Laboratory equipment | 11,520 | 0.2% | – | – |

| Equipment maintenance | 5,890 | 0.1% | 5,890 | 0.1% |

| Grand Total | 4,812,915 | 100.0% | 4,379,891 | 100% |

As different units oversee different activities, the cost distribution varies. The WHO-IPD central office bore the biggest share of the cost of surveillance (USD 855,385). Among the three FU units (iHMIS, CHISS, and EDCD), iHMIS had the highest cost for VPD surveillance at USD 129,510, mainly due to the relatively high event organization cost (USD 81,762).

At the subnational level, WHO-IPD FOs on average had a cost of USD 121,365 per FO compared with USD 13,805 for each government DHO. The average hospitals’ cost (USD 2,021) which were mostly RUs, was approximately five times higher than that of average cost of surveillance at other health facilities (USD 546) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Annual costs per work unit for VPD surveillance activities.

| Type of work unit | Economic cost per work unit |

Financial cost per work unit |

|---|---|---|

| In USD | In USD | |

| Central - FU | ||

| CHISS, Kathmandu | 24,290 | 16,048 |

| EDCD, Teku | 56,451 | 54,970 |

| iHIMS | 129,510 | 129,389 |

| Subnat. - DHO | ||

| DHO | 13,805 | 12,448 |

| WHO IPD | ||

| MO | 855,385 | 719,802 |

| FO | 121,365 | 113,316 |

| Laboratory | ||

| Population based laboratory 1 | 9,685 | 9,428 |

| Population based laboratory 2 | 43,895 | 38,425 |

| Sentinel laboratory 1 | 103,265 | 98,316 |

| Sentinel surveillance laboratory 2 | 30,729 | 28,905 |

| Reporting units | ||

| Hospital | 2,021 | 2,021 |

| HF | 546 | 546 |

Notes: FU – Federal Units ; CHISS – Child Health and Immunization Service Section; EDCD - Epidemiology and Disease Control Division; iHIMS - Integrated Health Information Management Section; DHO- District Health Office; WHO IPO– World Health Organization Immunization Preventable Diseases Department; FO- WHO field office; MO – Main office; Lab – Laboratory; HF – Health Facility.

Personnel was the biggest cost driver at 51%, followed by mission and event costs, at 18% and 16% respectively (Table 4). Personnel had a cost of USD 2.47 million, with the government staff accounting for 1.30 million (53%). WHO-IPD central office staff included in this study spent 66% of their time on surveillance, compared to WHO-IPD FO staff who spent 83% of their time on VPD surveillance. On the government side, VPD surveillance represented a smaller apportioned workload; at the central level, VPD surveillance accounted for 10% of the staff’s workload while at the district level it accounted for 19%.

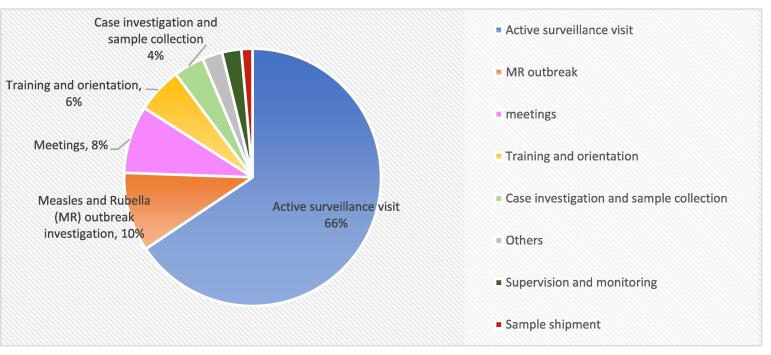

Missions were the second biggest cost driver at USD 882,877 with 52% of this being attributed to WHO’s costs. In mission costs, active surveillance visits were the biggest cost component (Graph 3).

Graph. 3.

Main categories of missions and their shares in total cost for mission.

Event organization had a total cost of USD 772,402, most of which were incurred at the subnational level. DHOs bore the highest cost for event organization (USD 516,000 (67%)), followed by WHO-IPD FOs (USD 142,000 (28%)).

4. Discussion

Every immunization program needs a strong VPD surveillance system to inform policy and to guide and course correct immunization program interventions based on surveillance information [ 1]. However, despite its being a necessity, very little is known about the cost of VPD surveillance [4], [5]. On the other hand, as VPD surveillance is an integral part of WHO Immunization Agenda 2030 (IA-2030), cost estimates specific to VPD surveillance and with disaggregation by costs shared between government and development partner agencies are needed to inform financial resource requirements (FRR) for VPD surveillance for IA-2030. [1], [9] This study could help fill in such an information gap.

Our results are consistent with the cost estimation provided by Nepal’s comprehensive multiyear plan for immunization (cMYP) in 2017, which costed vaccination monitoring and disease surveillance about USD 5.5 million for 2017 (versus USD 4.8 million in this study) [10]. This accounts for around 8% of Nepal’s USD $66.62 million immunization expenditures estimated in the same cMYP, making surveillance a relatively small but critical investment.

Nepal has relied heavily on GPEI funding routed mainly through the WHO Nepal country office to conduct VPD surveillance through its active VPD surveillance system. While this system started with supporting poliovirus surveillance only, it has since integrated other VPDs onto the same platform. Case-based surveillance data informed expert committees of the WHO South East Asia Region to declare that Nepal achieved polio elimination in 2014 and rubella control in 2018 [11], [12]. Similarly, sentinel surveillance for IBD and rotavirus diarrhea informed decisions of the national technical advisory group to introduce new vaccines in the national immunization program.[13]

On the other side, with the elimination of polio, GPEI funding has been reducing rapidly, by 63%, from USD 1.2 million to USD 450 000. [14], [15] This represents a big sustainability risk, as WHO will be challenged to continue the support for VPD surveillance and for the government to take over the specific tasks that WHO has been performing. While other donors (e.g. Gavi, United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) have stepped in to fill this gap, no long-term funding commitment is available at this moment,

Although GPEI has been a significant funding source for Nepal VPD surveillance system, the government of Nepal is also committing substantial resources to support VPD surveillance. This study found that the government bore more than half of the total VPD surveillance cost, around USD 2.7 million. This estimate seems high compared to Nepal National Health Account report, which recorded that between 2012/13 and 2015/16, the overall costs for epidemiological surveillance and disease control programs varied from USD 4.6 to 22.6 million per year with VPDs being a small part of the diseases on the list. [16] One of the reasons could be that the challenges in accurately estimating the value of shared resources for the disease specific programmes comparing to an estimation for the whole system.

In polio transition priority countries, such as Nepal, it may be necessary for governments to quantify the value of their own investments in surveillance as well as the total FRR needed to conduct VPD surveillance. By collecting the evidence on resource needs, health ministries can make a reasonable business case to secure internal budgets for continued support for VPD surveillance, as well as to donors for extending support for various components of an integrated VPD surveillance system in conjunction with the government. Polio transition in these priority countries can thus be considered as a process where financial ownership of varying proportions is gradually transferred to national governments over time as per country context.

Personnel are vital for a successful VPD surveillance system and were the largest cost driver in this study. Trained staff are an asset, and it takes time to build a high-quality workforce. GPEI funding had financed approximately 70–80% of the surveillance personnel cost in 2017. However, with GPEI funding declining, and if it is not replaced, there is a risk of reducing the number of experienced personnel and/or decreases in quality, which expose Nepal to the risk of -sub-optimal VPD surveillance, potentially delaying detection of outbreaks and program response.

Furthermore, while the government bore more than half the share of the expenditure of VPD surveillance through its extensive network of health facilities, interviewed government staff mentioned contributing 10% to 19% of their time to VPD surveillance. In contrast, WHO-IPD personnel dedicated 66% to 83% of their time to VPD surveillance. While not much information is available from other countries on staff time dedicated to surveillance, maintaining a sensitive surveillance system is time intensive and needs a dedicated team of well-trained public health personnel to maintain high surveillance standards. Such a dedicated team can keep surveillance site focal persons engaged in surveillance through professional interactions, facilitate timely response in investigating suspected cases, sustain interest in reporting through data dissemination and feedback to reporting clinicians, and build capacity through refresher trainings.

Understanding the current cost of VPD surveillance and its components will also allow Nepal to project the cost of changes to surveillance.

This study is subject to several limitations. This study collected data from a small number of cost centers. At the subnational level, the cost of sampled units was used to represent the average cost of the surveillance units in the same category. The surveillance units were grouped by province, ecological zones and surveillance function. The assumption is that inside each category, the cost per unit is not substantially different as surveillance workload is similar. This is a strong assumption as we assumed these cost centers that were selected sub-nationally have similar costs to cost centers at the same level. We tried to mitigate this by selecting surveillance sites across all seven provinces, three ecological zones and from the private and public sectors. Second, in general, WHO’s assets were given relatively shorter ULY than government assets of a similar type, which in turn increased the annual depreciation value of WHO assets. The capital cost was mainly composed of the annual depreciation value of the fixed assets, such as vehicle, laboratory equipment, and office equipment. The study set the rule based on the current assets’ values without investigating the need to upgrade or replace the assets. Many assets exceeded their expected useful life years (ULYs), and their depreciation value was considered to be zero. A national inventory is needed to better understand the capital investment needs for the government to upgrade or replace the current assets Thus, this approach underestimated the real need for investment in assets. There is no standardized definition on which shared resources are used for surveillance and how to attribute the proper percentage. Additionally, within the government’s accounting systems it was sometimes difficult to separate out money spent exclusively for VPD surveillance from those spent for other disease surveillance due to the accounting system structure, but also because many government resources are shared among several programs. Finally, the current study addressed the resource used for routine (non-outbreak) VPD surveillance. We evaluated the cost of surveillance in 2016–2017, which was a time when measles burden was lower than in 2018–2019. As the costs for outbreak response were not analyzed, it would not be possible to project costs for a medium or large sized outbreak surveillance needs from this study.

The allocation of the proportion of staff time spent on surveillance was collected through interviews which may be subject to recall bias. The cost of polio laboratory testing has not been included, as the laboratory is outside the country and not a cost incurred by the government or WHO country office, and there is no plan to shift these costs to the country.

This study undertook an ingredient-based approach with extensive field work to obtain the costs of VPD surveillance. This work, along with other country case studies on the cost of VPD surveillance that are ongoing, can be used to develop a simple tool to cost VPD surveillance accounting for the biggest cost drivers, which can help countries to more accurately budget for VPD surveillance. Although somewhat difficult to implement, such an ingredient-based approach as described here, can enable countries to choose core and add-on components of surveillance that can be supported. As more such country level estimates from polio priority countries become available, such estimates may help national governments and development partner agencies to jointly secure appropriate resources that are rightsized to sustain and improve VPD surveillance.

Author contribution

Huang XX and Patel M led on the conception and design of the study. Bose A, Rai P and Gupta B led on the acquisition of data. Huang XX, Patel M, and Bose A co-worked on the analysis and interpretation of data. Huang XX, Bose A and Patel M. led on the article drafting. Cohen A, Joshi S, and Vandelaer J revised critically the draft for important intellectual content. All co-authors reviewed the manuscript and gave final approval of the version to be submitted.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the authors’ and do not represent the views and opinions of the organizations they are affiliated with.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Thanks Claudio Politi from World Health Organization, Taiwo Abimbola and Sarah Pallas from United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for their technical support during the project and detailed review of the final report, Bishwa Adhikari from United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for his support on country mission and data collection. Dr Rahul Pradhan and Dr Dipesh Shrestha from WHO Nepal country office and Dr Bhim Singh Tinkari, government of Nepal for their support in the implementation of the whole project. Dr Sameer Dixit of Center for Molecular dynamics for the diligent field and data work for this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Contributor Information

Xiao Xian Huang, Email: xhuang@who.int.

Anindya Sekhar Bose, Email: bosea@who.int, guptab@who.int.

Pasang Rai, Email: Raip@who.int.

Sudhir Joshi, Email: joshisu@who.int.

Jos Vandelaer, Email: vandelaerjo@who.int.

Adam L. Cohen, Email: dvj1@cdc.gov.

Minal K. Patel, Email: patelm@who.int.

References

- 1.World Health Organization, Immunization Agenda 2030: Global Strategy on Comprehensive Vaccine-Preventable Disease Surveillance. 2020: Geneva, Switzerland.

- 2.Transition Independent Monitoring Board of the Polio Programme, The End of the Beginning: First Report of the Transition Independent Monitoring Board of the Polio Programme. 2017. Available from https://polioeradication.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/TIMB_Report-no1_Jul2017_EN.pdf

- 3.Polio Transition Planning: Report by the Director General. EB142/11. 2018, World Health Organization,: Geneva, Switzerland. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/EB142-11

- 4.Erondu N.A., Ferland L., Haile B.H., Abimbola T. A systematic review of vaccine preventable disease surveillance cost studies. Vaccine. 2019;37(17):2311–2321. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization, Conference Report: Technical Meeting on Expanded Programme on Immunization Vaccine-preventable disease Surveillance Costing, Geneva, Switzerland, 7-8 December 2016, V. Immunization, and Biologicals, Editor. 2016: Geneva, Switzerland.

- 6.World Health Organization. AFP/Polio data. September 4, 2020]; Available from: https://extranet.who.int/polis/public/CaseCount.aspx.

- 7.World Health Organization. Reported measles and rubella cases and incidence rates by Member States. 2020 September 4, 2020; Available from: https://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/burden/vpd/surveillance_type/measlesreportedcasesbycountry.xls?ua=1.

- 8.World health Organization. Global Strategy on Comprehensive Vaccine-Preventable Disease Surveillance, World Health Organization: Geneva. Avialable from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/global-strategy-for-comprehensive-vaccine-prevatble-disease-(vpd)-surveillance

- 9.World Health Organization, IMMUNIZATION AGENDA 2030: A global strategy to leave no one behind 2020: Geneva. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Child Health Division, Department of Health Services, Ministry of Health, 2016. National Immunization Programme, Nepal - Comprehensive Multi-Year Plan 2073-2077 B.S. (2017-2021), Nepal Ministry of Health: Kathemandou.

- 11.Bahl S. Polio-Free Certification and Lessons Learned — South-East Asia Region. MMWR. 2014;2014:941–946. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization, Nepal rubella control, 2018, available from https://www.who.int/southeastasia/news.

- 13.Sherchand J. Hospital based surveillance and molecular characterization of rotavirus in children less than 5 years of age with acute gastroenteritis in Nepal. Vaccine. 2018:7841–7845. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization, GPEI Budget 2017, online interactive report available from https://polioeradication.org/financing/financial-needs/financial-resource-requirements-frr/gpei-budget-2017/.

- 15.World Health Organization, GPEI Budget 2020, online interactive report available from https://polioeradication.org/financing/financial-needs/financial-resource-requirements-frr/gpei-budget-2020/.

- 16.Ministry of Health and Population, G.o.N., Nepal National Health Accounts 2012/13 – 2015/2018.