Abstract

Purpose:

Gliomas are the most common primary tumor of the brain and are classified into grades I-IV of the World Health Organization (WHO), based on their invasively histological appearance. Gliomas grading plays an important role to determine the treatment plan and prognosis prediction. In this study we propose two novel methods for automatic, non-invasively distinguishing low-grade (Grades II and III) glioma (LGG) and high-grade (grade IV) glioma (HGG) on conventional MRI images by using deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs).

Methods:

All MRI images have been preprocessed first by rigid image registration and intensity inhomogeneity correction. Both proposed methods consist of two steps: (a) three-dimensional (3D) brain tumor segmentation based on a modification of the popular U-Net model; (b) tumor classification on segmented brain tumor. In the first method, the slice with largest area of tumor is determined and the state-of-the-art mask R-CNN model is employed for tumor grading. To improve the perfor-mance of the grading model, a two-dimensional (2D) data augmentation has been implemented to increase both the amount and the diversity of the training images. In the second method, denoted as 3DConvNet, a 3D volumetric CNNs is applied directly on bounding image regions of segmented tumor for classification, which can fully leverage the 3D spatial contextual information of volumetric image data.

Results:

The proposed schemes were evaluated on The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA) low grade glioma (LGG) data, and the Multimodal Brain Tumor Image Segmentation (BraTS) Benchmark 2018 training datasets with fivefold cross validation. All data are divided into training, validation, and test sets. Based on biopsy-proven ground truth, the performance metrics of sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy are measured on the test sets. The results are 0.935 (sensitivity), 0.972 (specificity), and 0.963 (accuracy) for the 2D Mask R-CNN based method, and 0.947 (sensitivity), 0.968 (specificity), and 0.971 (accuracy) for the 3DConvNet method, respectively. In regard to efficiency, for 3D brain tumor segmentation, the program takes around ten and a half hours for training with 300 epochs on BraTS 2018 dataset and takes only around 50 s for testing of a typical image with a size of 160 × 216 × 176. For 2D Mask R-CNN based tumor grading, the program takes around 4 h for training with around 60 000 iterations, and around 1 s for testing of a 2D slice image with size of 128 × 128. For 3DConvNet based tumor grading, the program takes around 2 h for training with 10 000 iterations, and 0.25 s for testing of a 3D cropped image with size of 64 × 64 × 64, using a DELL PRECISION Tower T7910, with two NVIDIA Titan Xp GPUs.

Conclusions:

Two effective glioma grading methods on conventional MRI images using deep convolutional neural networks have been developed. Our methods are fully automated without manual specification of region-of-interests and selection of slices for model training, which are common in traditional machine learning based brain tumor grading methods. This methodology may play a crucial role in selecting effective treatment options and survival predictions without the need for surgical biopsy.

Keywords: brain tumor, convolutional neural networks, deep learning, Glioma grading, MRI image

1. INTRODUCTION

Gliomas are the most common primary tumor of the brain, which are rapidly progressive and neurologically devastating.1,2 According the World Health Organization (WHO) grading system, gliomas are classified into grades I-IV based on the histopathologic appearance obtained from surgical biopsy or resection,3 which represent whether the tumor is benign or malignant and what the malignancy scale the tumor has. Accurate classification of low-grade (WHO grade II) and intermediate-grate (WHO grade III) gliomas (LGG), and high-grade gliomas (HGG) or glioblastoma (WHO grade IV) plays an essential role in determining treatment option and in prognosis prediction.2,4

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a widely used technique that has been employed in the non-invasively diagnosing, management and follow-up of gliomas in clinical practice.5,6 Conventional MRI modalities including T1-weighted (T1), post-contrast enhanced T1-weighted (T1-Gd), T2-weighted and T2-FLAIR images are used for tumor evaluation. These MRI images provide anatomical characteristics of brain tumors. In addition, advanced MRI modalities like perfusion weighted, diffusion-weighted, diffusion tensor-weighted, and MR spectroscopic imaging etc. provide further microvascular, microstructural, and biochemical information.4,7,8

Currently, the standard procedure for tumor grading is based on histopathological analysis, which has three major limitations (a) biopsy is an invasive procedure with the potential risks outweighing the benefits; (b) biopsy may have an inherent sampling error due to the heterogeneous signals of the tumor on MRI images; (c) It may delay the diagnosis since histopathological analysis is typical time consuming.4,9 To overcome these drawbacks, computer assisted analysis on MRI images for tumor grading has been studied extensively.4,6–16 Traditional pattern classification and machine learning methods, such as linear discriminant analysis,4,10 independent component analysis,11 k-mean clustering,12 early artificial neural network,13 decision trees,14 and support vector machines (SVM)9,15 have been applied on either separate MRI sequence images, or various combination of conventional and advanced MRI modalities, and have achieved satisfying performance for glioma grading. These methods typically require manual definition of region of interests (ROIs). Explicit features including shape and statistical characteristics of tumor, image intensity characteristics on different image modalities, and image texture feature are then extracted on these ROIs for grade image classification. Those ROIs need to be carefully placed on contrast enhancing neoplastic, non-enhancing neoplastic, necrotic region, and edematous region, respectively.

In 2012, Krizhevsky et al. published their milestone paper about image classification with deep convolutional neural networks (CNN) AlexNet,17 which won the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge with large margin to other methods. Since then, deep learning-based methods have dominated various applications in computer vision as well as in medical image analysis. Deep learning methods have the advantage of implicitly learning very deep hierarchical features of image data, compared to traditional machine learning methods that take use of classical hand-crafted image features. As for gliomas classification, Yang et al. presented a deep learning-based method with transfer learning for glioma grading on conventional MRI images.18 AlexNet17 and GoogleNet19 with fine-turning pretrained model from the ImageNet dataset20 have been evaluated for LGG and HGG classification and have achieved improved performance. However, in their method, image slices containing tumor tissue need to be manually picked by neuroradiologists, and tumors are segmented from the ROIs which also need to be manually defined to cover around 80% tumor area. Akkus et al. presented a method predicting the 1p/19q chromosomal arms status in LGG data using a multiscale CNN architecture.21 But, their method depends on a semi-automatic tumor segmentation. The user needs to select the slice with largest tumor area, and to place a ROI to completely cover the tumor and some adjacent normal tissue. Brain atlas and geodesic active contours are applied for final tumor segmentation. Segmentation results are then feed into the deep CNN for model training and testing. Recently, Chen et al.22 developed an automatic computer-aided diagnosis system for gliomas grading. A multiscale 3D CNNs based on DeepMedic is trained to segment whole tumor regions. The method requires explicit extraction of radiomic features, including first-order features, shape and texture features on the segmented tumor regions. These features are further selected by using SVM. Finally, an extreme gradient boosting classifier is trained for gliomas grading. Banerjee et al. investigated the power of deep CNN for predicting brain tumor grade in MR images by following the determination of the 1p/19q status in LGG data.23 Three CNN architectures are developed for tumor detection and grade prediction based on MRI patches, MRI slices, and multiplanar volumetric MR images, respectively. The VolumeNet model based on multiplanar volumetric MR images is essentially a 2.5D CNNs, not a truly 3D CNNs. The 3D spatial contextual information of volumetric MR images has not been fully exploited in the CNN architecture. In addition, their models are trained on the TCIA data and tested using MICCAI BraTS 2017 data. Unfortunately, part of BraTS 2017 data is from TCIA which means there is an overlap between training and testing data. Furthermore, in the architecture, the SliceNet, all testing MRI slices containing the brain tumors are from the ground truth rather than from results of any segmentation method.

The purpose of this study is to investigate fully automated methods for classifying gliomas into LGG and HGG by using a deep CNN scheme. Two methods have been developed for glioma grading on conventional MRI images. They are fully automated without any manual intervention of ROIs definition and specific slice selection. All MRI images have been preprocessed first by rigid image registration and intensity inhomogeneity correction. The proposed methods consist of two steps: (a) 3D brain tumor segmentation based on a modification of the popular U-Net model;24,25 (b) grade classification on segmented brain tumor. Due to the success of the Multimodal Brain Tumor Segmentation (BraTS) Benchmark challenges26 in recent years, CNN-based methods have achieved better improvement than traditional methods for brain tumor segmentation, even though results are not perfect. In the first method, denoted as 2D Mask R-CNN, the slice with largest area of tumor is determined and the state-of-the-art mask R-CNN model27 is employed for tumor grading. ResNet architecture28 with feature pyramid network (FPN)29 is utilized, which combines both high resolution fine detail image features and low resolution high semantic features. To improve the performance of the grading model, a 2D data augmentation30 has been implemented to increase both the amount and the diversity of the training images. In the second method, denoted as 3DConvNet, a 3D volumetric CNNs is applied directly on bounding image regions of segmented tumor for grade classification, which can fully leverage the 3D spatial contextual information of volumetric image data.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

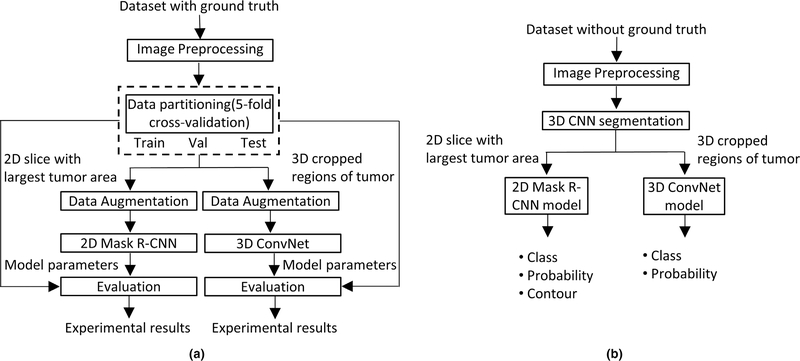

The flowchart of proposed methods for glioma grading on conventional MRI images is shown in Fig. 1. Three major steps: (a) image preprocessing; (b) 3D brain tumor segmentation; (c) tumor grading, as well as the datasets utilized in this study are described in detail in the subsequent sections. Note that in Fig. 1(a), 3D brain tumor segmentation has been utilized to create ground truth segmentation.

FIG. 1.

Flowchart of the proposed methods for gliomas grading. (a) Training and evaluation on dataset with ground truth; (b) testing on data without ground truth.

2.A. Data

Three publicly available datasets have been used in the study. All these data are preoperative. The first one, denoted as Dataset1, is the BraTS 2018 data, which includes 210 HGG GBM and 75 LGG patients.26,31 All BraTS multimodal images are provided as NIfTI files with T1, T1-Gd, T2, and T2-FLAIR weighted volumes and were acquired with different clinical protocols and various scanners from different institutions. All images in BraTS dataset have been segmented manually, by one to four raters, following the same annotation protocol, and their annotations were approved by experienced neuro-radiologists. These annotations were taken as the ground truths for models training and testing. Annotations comprise the post-contrast enhancing tumor, the peritumoral edema, and the necrotic and non-enhancing tumor core. All images have been co-registered to the same anatomical reference using a rigid transform based program implemented in ITK.32 In addition, all images have been skull-stripped and interpolated to 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 voxel resolution.

The second dataset, denoted as Dataset2, is from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) LGG collection,33 publicly available in The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA), which includes 108 subjects of pre-operative, skull-stripped and co-registered multimodal (i.e., T1, T1-Gd, T2, T2-FLAIR) MRI volumes. Only 65 subjects are distributed with ground truth segmentations. These 65 subject data have been discarded in our experiments, as they are overlapped with the LGG data in Dataset1. Thirty subjects were chosen from the remaining 43 subjects without ground truth segmentations provided (The other 13 subjects data were discarded either due to poor image quality or with missing specific modality of MRI image). These 30 subjects were first segmented by the U-Net based 3D CNN method,25 and then were manually corrected by an expert radiation oncologist in our group. The result segmentations were taken as the ground truth segmentations in our experiments. Note that this dataset is initially provided by TCGA for imaging features extraction, which is then integrated with molecular characterization offered by TCGA to build up associations with molecular markers, clinical outcomes, treatment responses, and other endpoints.33

2.B. Image preprocessing

Two steps of image data preprocessing are performed to reduce two common artifacts in MRI images, which are the background intensity inhomogeneity and the non-standardized MRI intensity values. The first artifact presents a slowly varying background component of image inhomogeneity in an MRI image. This inhomogeneity issue has been handled extensively in the literature and many effective methods have been developed.34,35 The latter problem implies the lack of a tissue-specific absolute intensity numeric meaning of the MRI pixels. The importance of handling such MRI intensity non-standardization and solutions to overcome its effect have been addressed in the literature.36–38 In the first step of our image preprocessing, the background intensity inhomogeneity in MRI images were corrected using the well-known N4ITK method.35 Then, the intensity of each MRI image was normalized using a very simple but effective method. Each modality image of each subject is normalized independently by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation of the brain region. Resulting images are then clipped at [−5, 5] to remove outliers and subsequently rescale to [0, 1].

2.C. 3D brain tumor segmentation

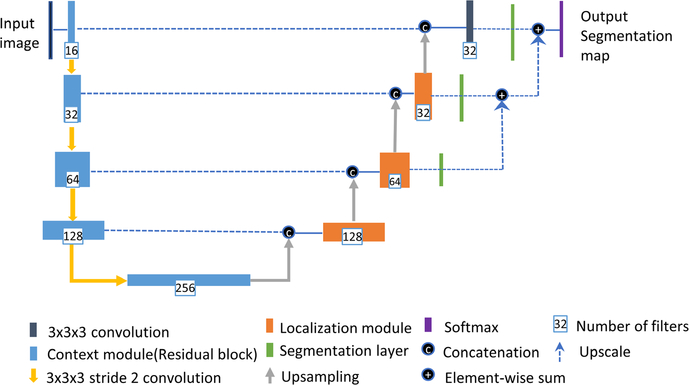

U-Net is one the most popular neural net architectures used in image segmentation.24 In this study, we employed a variant of the U-Net architecture implemented by Isensee et al.25 The network architecture is shown in Fig. 2, which employs a couple of changes to the original U-net including an equally weighted dice coefficient, residual weight, and deep supervision.

FIG. 2.

The network architecture for three-dimensional tumor segmentation.

The U-Net based methods have the strength to intrinsically combine features from different scales throughout the entire network. As stated in the reference paper,25 the network used in this study consists of a context (contracting) pathway at left side and a localization (expanding) pathway at right side. The context (contracting) pathway encodes increasingly abstract feature representations of the input image as we progress deeper into the network via the 3 × 3 × 3 convolutions with stride of 2 for down-sampling. The number of feature filters is doubled while descending the contracting pathway, and the image has lower spatial resolution. The context modules in the contracting pathway are implemented via residual learning to solve the degradation problem when the depth of a neural network increases. At right side of the network architecture is the localization (expansive) pathway. The idea is to propagate the rich contextual features at deeper levels of the network with low spatial resolution to high resolution layers. It is achieved by up-sampling the feature maps via a simple upscale operator, and then followed by a 3×3×3 convolution that halves the number of feature maps. The up-sampled features from the lower spatial resolution maps are then combined with features of high spatial resolutions from context (contracting) pathway via concatenation. After concatenation operation, a localization module recombines these features together, which consists of a 3×3×3 convolution and 1×1×1 convolution to further halves the number of feature maps. Segmentation maps from different level of the networks in the expanding pathway are created for deep supervision, which are used to reduce the coarseness of the final segmentation. The segmentation map at low resolution level is brought to a higher resolution level via upscale deconvolution operation and combined via element-wise summation. It has been proven that the final segmentation can be refined in this manner.39,40 A multiclass adaptation of the dice loss has been integrated into deep learning framework to overcome the class imbalance problem since the enhanced tumor in the brain typically has small size.

2.D. Tumor classification in 2D

The slice with largest area of segmented tumor from Section 2.C. is determined and the state-of-the-art mask R-CNN model27 is employed on the 2D slice for tumor grading.

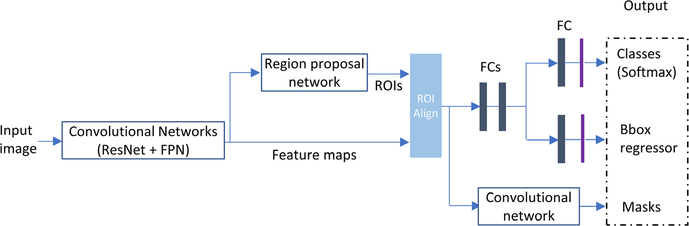

Mask R-CNN (regional convolutional neural network) has been extensively used for object detection, classification, and segmentation.27 In this study, we employ this method for brain tumor classification. A brief introduction about the Mask R-CNN is given in this section, but the reference paper provides detailed description. The architecture of the Mask R-CNN is shown below in Fig. 3. Mask R-CNN is an extension of previously successful Faster R-CNN, which generates bounding boxes of objects and classifies region proposals (regions likely to contain an object). Mask R-CNN essentially adds one more branch to generate masks within top region proposals. In general, Mask R-CNN consists of four main components:

Backbone module. This is a convolutional neural network which serves as a feature extractor. In this study, ResNet and feature pyramid network (FPN) are used as the backbone. ResNet is employed to construct bottom-up pathway for feature extraction. As the pathway goes up, spatial resolution decreases, more high-level (semantic) feature extracted. FPN provides a top-down pathway to construct higher resolution layers from a semantic rich layer. Lateral connections between reconstructed layers (from top-down pathway) and corresponding feature maps (from bottom-up pathway) improve prediction of locations. By doing so, it generates multiple feature layers (multiscale feature maps) with better quality information than the regular feature pyramid for object detection.

RPN. RPN is a lightweight neural network that scans over the backbone feature maps through using a slide-window manner and predicts if the proposed region of interest (ROI) contains any object. Based on RPN prediction, top ROIs that are likely to contain objects are picked and their corresponding locations and sizes are further refined. The final proposals (region of interest) are passed to the next stage.

ROI Classifier and Bounding Box Regressor. In this step, the algorithm takes the regions of interests proposed by the RPN as inputs and outputs a classification (softmax) and a bounding box (regressor). Mask R-CNN uses a method called ROI Align to crop a part of the feature map and resize it to a fixed size. Bilinear interpolation is applied for feature value calculation. ROI pooling is refined in this manner.

Segmentation Masks. The mask branch (bottom right on the architecture shown in Fig. 3) is a convolutional network that takes the positive regions selected by the ROI Align and generates masks for objects contained in ROIs.

FIG. 3.

Architecture of the mask R-convolutional neural networks.

In deep learning-based applications, particularly, in the field of medical image analysis, it is a common problem that there are not enough training data to overcome the overfitting of the large number of neural network parameters. A typical approach to address this problem is to augment datasets artificially with label-preserved transformations, such as random image translation, rotation, shearing, horizontal/vertical flipping, and cropping parts out of images.17 A random combination of these transformations can be applied further on datasets to enlarge the number of training data by several fold which is helpful to minimize the parameter overfitting problem. Recently, Google Brain team released a tool called AutoAugment30 to search for improved data augmentation policies for images. By applying for the optimized data augmentation policies, state-of-the-art accuracy on public data of CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, SVHN, and ImageNet has been achieved. CIFAR-10 dataset contains 60 000 color images in 10 different classes. CIFAR-100 dataset is similar to CIFAR-10, but with 100 classes and 600 color images each. While ImageNet dataset contains one million color images in 1000 classes, and SVHN has approximately 600 000 images of 10 classes with digits 0–9 only. In our experiments, a variant of the policies learned from SVHN data has been used since the geometric transformations are picked more often by AutoAugment on SVHN. The best policies found on CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100 and ImageNet mainly focused on color-based transformations. Twenty-three sub-policies expanded the training dataset to 23-fold larger.

2.E. Tumor classification in 3D

The architecture of the 3DConvNet model for tumor grading is shown below in Fig. 4, which defines an image-level classification application. The multimodal 3D bounding image regions of segmented tumor from Section 2.C. are taken as input for grade classification. ResNet is also used as the 3DCNN backbone. Unlike in the Mask R-CNN method, region proposal network is not required here since the 3D tumor segmentation already defines the bounding region. Segmentation mask is not required either. The only output is an image-level tumor classification (softmax). To fully leverage the 3D spatial contextual information in volumetric medical image, all layers in ResNet backbone, including convolutional and pooling layers, are implemented in a 3D manner.

FIG. 4.

Architecture of the 3DConvNet for tumor classification.

3. EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

In this section, the performance of the proposed methods for brain tumor grading in conventional MRI images were evaluated. In Dataset1 and Dataset2, in total we have 210 HGG subject data and 105 LGG subject with all four modalities (T1, T1-Gd, T2, and FLAIR). All models are trained in a 5-fold cross validation, each fold with two-third of HGG subject and one-third of LGG subject, and data was divided into training (60%), validation (20%) and test (20%) sets.

For 3D brain tumor segmentation, the implementation of Isensee’s model25 on Keras (https://github.com/ellisdg/3DUnetCNN) has been utilized in this study. The performance of Isensee’s model has been demonstrated on BraTS 2017 validation set (dice scores of 0.896, 0.797 and 0.732 for whole tumor, tumor core, and enhancing tumor, respectively). The network architecture was trained from scratch in an image-to-image fashion rather than patches based. All images were resampled to size of 128 × 128 × 128 voxels due to the limitations of GPU memory and training time. Batch size was set as 1 and total training epochs 300. Training is started with an initial learning rate of 5 × 10−4. Learning rate is reduced by half after 10 epochs if the validation loss did not improve.

For 2D Mask R-CNN based tumor grading, the official implementation of Mask R-CNN within the Detectron system from Facebook Research (https://github.com/facebookresearch/Detectron) was employed. The slice with largest tumor area from 3D brain tumor segmentation was chosen. Slices from three MRI modalities (T1-Gd, T2, and Flair) are set as three RGB channels and combined as a JPG file. Corresponding ground truth segmentation in the slice is saved as a PNG file. Three annotation files (one for each of training, validation, and test datasets) in COCO json format were generated and fed into the Detectron system to run the Mask R-CNN. The network architecture is trained based on fine-tuning of a pretrained model (ResNet) on ImageNet dataset, which takes less time to achieve optimized network parameters. The base learning rate is set as 0.0025, and weight decay 0.0001. Learning rate can be decreased by a factor of 10 depending on the preset steps.

The 3DConvNet tumor grading was implemented based on the NiftyNet,41 a deep-learning platform particularly for medical imaging (https://github.com/NifTK/NiftyNet). For each subject data, the 3D bounding regions of segmented brain tumor were cropped from four MRI modalities and were resized as 64 × 64 × 64. A single label file with NIfTI format was created with size of 1 × 1 × 1. Its value was set as 0 for LGG class, and 1 for HGG class. For model training, data was augmented with random rotation between angle (−20°, 20°), random scaling between (−0.2, 0.2), and random axes flipping on x (Left-Right) and y (Anterior-Posterior) directions. Cross entropy loss function was utilized, and learning rate was set as 0.0001.

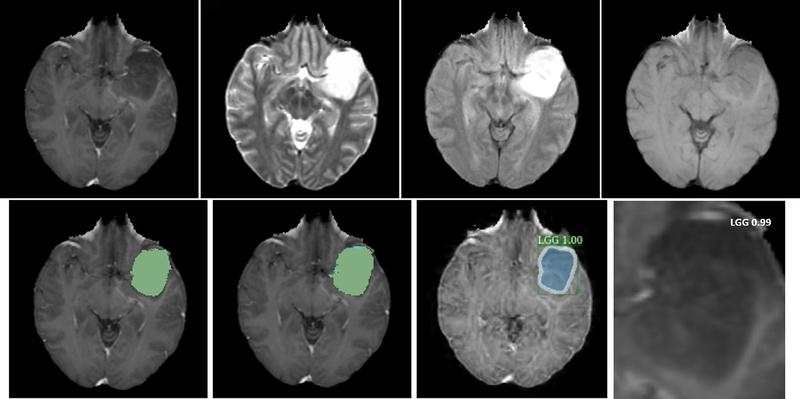

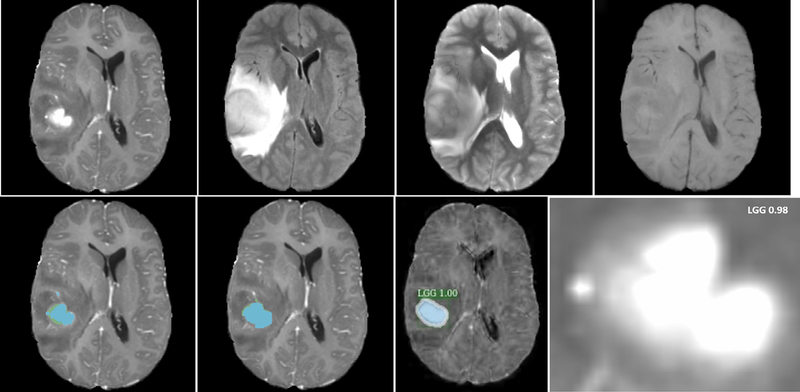

An example of glioma grading of one HGG subject from Dataset1 is illustrated in Fig. 5. In the result of tumor grade classification from 2D Mask R-CNN, additional estimation probability is also provided, and the segmentation mask and contour are shown to qualitatively compare the segmentation result from the mask R-CNN method with that from the U-Net based segmentation method. For tumor grade from the 3DConvNet, only class with prediction probability are produced. Neither bounding box nor segmentation mask is necessary. Figures 6 and 7 show examples of two glioma grading of LGG patient from Dataset1 and Dataset2, respectively.

FIG. 5.

Illustration of glioma grading of one high-grade (grade IV) glioma patient from Dataset1. (a) T1-Gd; (b) T1; (c) T2; (d) T2-Flair; (e) brain tumor segmentation result (green color on nectotic and non-enhancing tumor core, blue color on Gd-enhancing tumor); (f) segmentation ground truth; (g) tumor grade with estimation probability and tumor contour by using two-dimensional Mask R-convolutional neural networks; (h) tumor grade with prediction probability by using 3DConvNet.

FIG. 6.

Illustration of glioma grading of one low-grade (Grades II and III) glioma patient from Dataset1/Dataset2. (a) T1-Gd; (b) T1; (c) T2; (d) T2-Flair; (e) brain tumor segmentation result (green color on nectotic and non-enhancing tumor core, blue color on Gd-enhancing tumor); (f) segmentation ground truth; (g) tumor grade with estimation probability and tumor contour by using two-dimensional Mask R-convolutional neural networks; (h) tumor grade with prediction probability by using 3DConvNet.

FIG. 7.

Illustration of glioma grading of another low-grade (Grades II and III) glioma patient from Dataset1/Dataset2. (a) T1c; (b) T1; (c) T2; (d) T2-Flair; (e) brain tumor segmentation result (green color on nectotic and non-enhancing tumor core, blue color on Gd-enhancing tumor); (f) segmentation ground truth; (g) tumor grade with estimation probability and tumor contour by using two-dimensional Mask R-convolutional neural networks; (h) tumor grade with prediction probability by using 3DConvNet.

The performance of two brain tumor grading methods were evaluated by the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy.

Sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of both 2D Mask R-CNN (with and without data augmentation) and 3DConvNet methods for tumor classification are shown in Table I. In general, the 3DConvNet method performs slightly better than the 2D Mask R-CNN method with data augmentation, and which is better than that of method without data augmentation. There is still a room for improvement of the sensitivity of 3DConvNet method in the future. The proposed methods are also compared with two other reported studies. Chen et al.22 achieved an accuracy of 0.913 on BraTS 2015 Data, which contains 220 HGG subjects and 54 LGG subjects. The method requires explicit feature extraction on segmented whole tumor including edema region. Tradition machine learning techniques such as SVM and extreme gradient boosting classifier are employed for final tumor classification. Yang et al.18 achieved an accuracy of 0.945 from a pretrained 2D GoogLeNet on a private dataset, which contained 61 HGG data and 52 LGG data. Note that the method depends on tumor segmentation on manually specified ROIs.

Table I.

Tumor classification performance of two proposed methods: two-dimensional (2D) Mask R-convolutional neural network (CNN) (with and without data augmentation) and 3DConvNet. Sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of each method are listed.

| Method | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 2D mask R-CNN (w/o) | 0.864 | 0.917 | 0.891 |

| 2D mask R-CNN (w) | 0.935 | 0.972 | 0.963 |

| 3DConvNet | 0.947 | 0.968 | 0.971 |

The proposed methods are executed on a DELL PRECISION TOWER T7910 with a 20-core 2.20 GHZ Xeon CPU, with 64 GB memory under the Ubuntu 18.04 Linux operating system. Two GPU NVIDIA Titan Xp with 12 GB device memory were used. For 3D brain tumor segmentation, the program takes around ten and a half hours for training with 300 epochs on BraTS 2018 dataset and takes only around 50 s for testing of a typical image with a size of 160 × 216 × 176. For 2D Mask R-CNN based tumor grading, the program takes around 4 h for training with around 60 000 iterations, and around 1 s for testing of a 2D slice image with size of 128 × 128. For 3DConvNet based tumor grading, the program takes around 2 h for training with 10 000 iterations, and 0.25 s for testing of a 3D cropped image with size of 64 × 64 × 64.

4. DISCUSSION

Deep CNNs are powerful algorithms that typically work well when trained on a large amount of data. One of the major difficulties that limit the application of deep CNNs in the field of medical image analysis is the shortage of labelled training data. Data augmentation and transferred learning are commonly used to partially solve the problem. Google’s AutoAugment provided the best augmentation policies for a given dataset using reinforcement learning strategy. In this paper, a subset of policies generated by the AutoAugment, which are optimal on the ImageNet dataset, have been used to improve the performance of our gliomas grading task. To achieve the optimal data augmentation policies on this training dataset through AutoAugment, many powerful computational resources are required. A fast and flexible data augmentation solution based on Bayesian optimization instead of reinforcement learning is under investigation.42

In gliomas grade modelling, a pretrained ResNet50 model on ImageNet has been used for fine-turning of network architecture parameters. The network architecture is based on 2D CNNs, which is used mostly in natural RGB images to extract spatial features in two dimensions. 3D volumetric Medical images provide more spatial context information. The benefit of 3D CNNs to incorporate the volumetric spatial information has been reported to produce a better performance in 3D medical image classification.43 A 3D CNNs named 3DConvNet has been implemented on the NiftyNet platform,41 and the model is trained from scratch for glioma grading. Its performance is slight better than that of the state-of-the-art 2D Mask R-CNN model from our experimental results.

The proposed method focused on the image analysis of conventional MRI images to grade gliomas. Our studies in tumor grade modelling indicated good performances with high sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy. Several methods in the literature have reported high accuracy in glioma grading between HGG and LGG,18,23 but further classification of grade II and grade III in LGG is still a challenging problem.44 Some referenced studies take advantage of multiparametric MRI images to differentiate glioma grades.4 The relatively new MRI imaging techniques can provide more quantitative information for accessing tumor vascularity, cellularity, morphology, and tumor metabolic information. Wang et al. developed machine learning models for automated grading gliomas into grades II, III, and IV from digital pathology images.44 They combined imaging features from Whole Slide images and the proliferation marker Ki-67 PI information for brain tumor grading. Traditional machine learning technique SVM was utilized for the classifier. High classification accuracies for grade II, III, and IV have been achieved. The combination of conventional MRI images with advanced MRI modalities, as well as digital pathology images may lead to a better understanding of tumor characteristics. In future study, it will be worth investigating the application of deep CNNs on the combination of images using conventional, advanced MRI modalities and digital pathology images for more accurate glioma grading.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Effective brain tumor grading methods on conventional MRI images based on deep convolutional neural networks have been developed. Unlike a traditional machine learning based tumor grading methods, our methods are fully automated without manual specification of region-of-interests and manual selection of slices for model training. This methodology may play a crucial role in selecting effective treatment options and survival predictions without the need for surgical biopsy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, NIH.

Contributor Information

Ying Zhuge, Radiation Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Holly Ning, Radiation Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Peter Mathen, Radiation Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Jason Y. Cheng, Radiation Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA

Andra V. Krauze, Division of Radiation Oncology and Developmental Radiotherapeutics, BC Cancer, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Kevin Camphausen, Radiation Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA.

Robert W. Miller, Radiation Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA

REFERENCES

- 1.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 world health organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:803–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeAngelis LM. Brain tumors. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:114–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ostrom QT, Bauchet L, Davis FG, et al. The epidemiology of glioma in adults: a “state of the science” review. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16:896–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caulo M, Panara V, Tortora D, et al. Data-driven grading of brain gliomas: a multiparametric MR imaging study. Radiology. 2014;272:494–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cha S Update on brain tumor imaging: from anatomy to physiology. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:475–487. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer S, Wiest R, Nolte LP, Reyes M. A survey of MRI-based medical image analysis for brain tumor studies. Phys Med Biol. 2013;58:R97–R129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inano R, Oishi N, Kunieda T, et al. Voxel-based clustered imaging by multiparameter diffusion tensor images for glioma grading. Neuroimage Clin. 2014;5:396–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arvinda HR, Kesavadas C, Sarma PS, et al. Glioma grading: sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values of diffusion and perfusion imaging. J Neurooncol. 2009;94:87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zacharaki EI, Wang S, Chawla S, et al. Classification of brain tumor type and grade using MRI texture and shape in a machine learning scheme. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62:1609–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tate AR, Majos C, Moreno A, Howe FA, Griffiths JR, Arus C. Automated classification of short echo time in in vivo 1H brain tumor spectra: a multicenter study. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang Y, Lisboa PJG, El1-Deredy W,. Tumour grading from magnetic resonance spectroscopy: a comparison of feature extraction with variable selection. Statist Med. 2003;22:147–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mouthuy N, Cosnard G, Abarca-Quinones J, Michoux N. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging to differentiate high-grade gliomas and brain metastases. J Neuroradiol. 2012;39:301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sachdeva J, Kumar V, Gupta I, Khandelwal N, Ahuja CK. A dual neural network ensemble approach for multiclass brain tumor classification. Int J Numer Method Biomed Eng. 2012;28:1107–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zacharaki EI, Morita N, Bhatt P, O’Rourke DM, Melhem ER, Davatzikos C. Survival analysis of patients with high-grade gliomas based on data mining of imaging variables. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33:1065–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emblem KE, Zoellner FG, Tennoe B, et al. Predictive modeling in glioma grading from MR perfusion images using support vector machines. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:945–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohan G, Subashini MM. MRI based medical image analysis: survey on brain tumor grade classification. Biomed Sign Proces. 2018;39:139–161. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Hinton GE. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2012;1:1097–1115. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Y, Yan LF, Zhang X, et al. Glioma grading on conventional MR images: a deep learning study with transfer learning. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szegedy C, Liu W, Jia Y, et al. Going deeper with convolutions. In: 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2015:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng J, Dong W, Socher R, Li LJ, Li K, Li FF. ImageNet: a large-scale hierarchical image database. Proc CVPR IEEE. 2009:248–255. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akkus Z, Ali I, Sedlar J, et al. Predicting deletion of chromosomal arms 1p/19q in low-grade gliomas from MR images using machine intelligence. J Digit Imaging. 2017;30:469–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen W, Liu B, Peng S, Sun J, Qiao X. Computer-aided grading of gliomas combining automatic segmentation and radiomics. Int J Biomed Imaging. 2018;2018:2512037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Banerjee S, Mitra S, Masulli F, Rovetta S. Deep radiomics for brain tumor detection and classification from multi-sequence MRI; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ronneberger O, Fischer P, Brox T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In: Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2015 (Springer International Publishing, Cham; 2015: 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Isensee F, Kickingereder P, Wick W, Bendszus M, Maier-Hein KH. Brain tumor segmentation and radiomics survival prediction: contribution to the BRATS 2017 challenge. In: MICCAI Multi modal Brain Tumor Segmentation Challenge (BraTS). Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018:287–297. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menze BH, Jakab A, Bauer S, et al. The multimodal brain tumor image segmentation benchmark (BRATS). IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2015;34:1993–2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He K, Gkioxari G, Dollár P, Girshick R. Mask R-CNN. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) (2017), pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- 28.He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (IEEE, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2016): 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin T, Dollár P, Girshick R, He K, Hariharan B, Belongie S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017;936–944. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cubuk ED, Zoph B, Mane D, Vasudevan V, Le QV. AutoAugment: Learning Augmentation Policies from Data;2018. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bakas S, Akbari H, Sotiras A, et al. Advancing the cancer genome atlas glioma MRI collections with expert segmentation labels and radiomic features. Sci Data. 2017;4:170117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luis Ibanez WS. The ITK Software Guide 2.4. Clifton Park, NY: Kitware, Inc.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bakas S, Akbari H, Sotiras A, et al. Segmentation labels and radiomic features for the pre-operative scans of the TCGA-LGG collection; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guillemaud R, Brady M. Estimating the bias field of MR images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1997;16:238–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tustison NJ, Avants BB, Cook PA, et al. N4ITK: improved N3 bias correction. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2010;29:1310–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nyul LG, Udupa JK, Zhang X. New variants of a method of MRI scale standardization. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2000;19:143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhuge Y, Udupa JK. Intensity standardization simplifies brain MR image segmentation. Comput Vis Image Understand. 2009;113:1095–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pereira S, Pinto A, Alves V, Silva CA. Brain tumor segmentation using convolutional neural networks in MRI images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2016;35:1240–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kayalıbay B, Jensen G, van der Smagt P. CNN-based Segmentation of. Medical Imaging Data; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen H, Dou Q, Yu L, Qin J, Heng PA. VoxResNet: deep voxelwise residual networks for brain segmentation from 3D MR images. NeuroImage. 2018;170:446–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gibson E, Li W, Sudre C, et al. NiftyNet: a deep-learning platform for medical imaging. Comput Methods Progr Biomed. 2018;158:113–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tran T, Pham T, Carneiro G, Palmer L, Reid I. A Bayesian Data Augmentation Approach for Learning Deep Models; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang C, Rangarajan A, Ranka S. Visual explanations from deep 3D convolutional neural networks for alzheimer’s disease classification. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2018;2018:1571–1580. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang X, Wang D, Yao Z, et al. Machine learning models for multiparametric glioma grading with quantitative result interpretations. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]