ABSTRACT

Mobile phones (MPs) have become an important work tool around the world including in hospitals. We evaluated whether SARS-CoV-2 can remain on the surface of MPs of first-line healthcare workers (HCW) and also the knowledge of HCWs about SARS-CoV-2 cross-transmission and conceptions on the virus survival on the MPs of HCWs. A cross-sectional study was conducted in the COVID-19 Intensive Care Unit of a teaching hospital. An educational campaign was carried out on cross-transmission of SARS-CoV-2, and its permanence in fomites, in addition to the proper use and disinfection of MPs. Herewith an electronic questionnaire was applied including queried conceptions about hand hygiene and care with MP before and after the pandemic. The MPs were swabbed with a nylon FLOQ Swab™, in an attempt to increase the recovery of SARS-CoV-2. All MP swab samples were subjected to SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR; RT-PCR positive samples were subjected to viral culture in Vero cells (ATCC® CCL-81™). Fifty-one MPs were swabbed and a questionnaire on hand hygiene and the use and disinfection of MP was applied after an educational campaign. Most HCWs increased adherence to hand hygiene and MP disinfection during the pandemic. Fifty-one MP swabs were collected and two were positive by RT-PCR (4%), with Cycle threshold (Ct ) values of 34-36, however, the cultures of these samples were negative. Although most HCWs believed in the importance of cross-transmission and increased adherence to hand hygiene and disinfection of MP during the pandemic, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in MPs. Our results suggest the need for a universal policy in infection control guidelines on how to care for electronic devices in hospital settings.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2 hospital cross-contamination, Healthcare workers’ mobile phones, SARS-CoV-2 on surfaces

BACKGROUND

Mobile phones (MPs) have become an important work tool around the world including in hospitals. However, to date, there are no official policies from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on their use or disinfection in healthcare facilities. The permanence of SARS-CoV-2 in inert hospital surfaces surrounding COVID-19 patients has been described1 raising the concern on cross transmission2. Even though SARS-CoV-2 has been found in MPs of symptomatic COVID-19 patients3, they have not been reported as source of transmission in the hospital.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

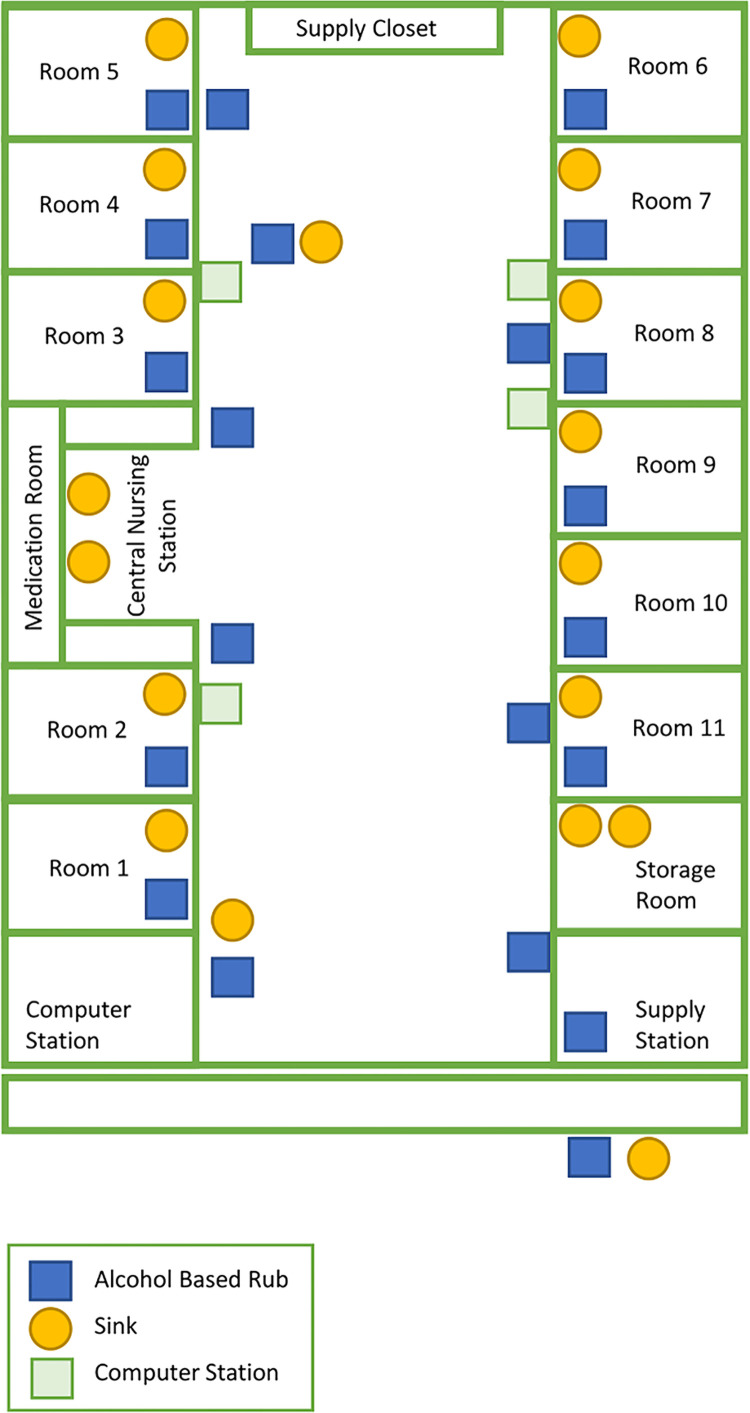

This is a cross-sectional study performed in an adult Intensive Care Unit (ICU) of a university hospital in Sao Paulo, Brazil. The unit belongs to a 1,000-bed facility established as a COVID-19 reference center. The ICU has 11 separate patient-rooms (Figure 1). Healthcare workers (HCWs) wear laboratory coats, N95 face masks and surgical caps inside the unit and add a surgical gown, face shield and gloves when entering the patient room. An educational campaign on SARS-CoV-2 cross transmission, its permanence on fomites, and the proper use and disinfection of MPs was performed at the beginning of the pandemic. Informative posters were placed in the unit containing a QR code with access to a video of the campaign advising the use of swabs with 70% isopropyl alcohol for the disinfection of MPs, carefully avoiding the openings of the device and placing a screen protector to protect the oleophobic coating of the MP. We suggest doing this procedure before, during and after the shifts. It was also recommended to avoid the use of MPs during patient care and in the restroom.

Figure 1. Layout of the COVID-19 Intensive Care Unit showing the distribution of hand rub dispensers and handwashing sinks in the unit.

Ten days after the campaign we collected samples of MPs from the HCW’s And an electronic questionnaire was applied, including conceptions of hand hygiene and MP care before and after the pandemic. The MPs were swabbed with a nylon FLOQ Swab™ (Copan Italia SPA, Italy), in an attempt to increase the recovery of SARS-CoV-2. MPs were swabbed starting from the front screen and without removing their cases. After sampling, the swabs were placed in universal transport medium (UTM™ Copan Italia SPA, Italy) and stored at -80 ºC.

All of the MPs swab samples were submitted to SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR. Positive reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) samples were submitted to viral culture. The RNA extraction was performed using the QIAmp viral RNA mini kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For the RT-PCR assay, the commercial RealStar® SARS-CoV-2 Kit 1.0 (Altona-Diagnostics, Hamburg, Germany) was used, which qualitatively detects the presence of SARS-CoV-2 by amplifying the genes S and E of the virus. The amplification was carried out using the Roche Light Cycler® 96 System (Roche Molecular Systems, Basel, Switzerland) and the sample was considered positive when at least one of the target genes was detected.

The culture was performed by inoculating an aliquot of the sample collected from the MPs into Vero cells (ATCC® CCL-81™), as previously described4,5, in Dulbecco minimal essential medium supplemented with fetal bovine serum (5%), antibiotics and antimycotics (Cultilab, Campinas, SP, Brazil) at 37 °C in an atmosphere with 5%CO2. Every day Vero cells were examined for cytopathic effect (CE), and new RT-PCRs were performed from the culture supernatant on the third, seventh and fourteenth days of culture.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research was approved by the Institucional Ethics Committee and Plataforma Brasil, process Nº 4.315.435. All the participants signed an informed consent to participate and the personal information of the participants is confidential.

RESULTS

During the educational campaign, the HCWs were interested and concerned on how to properly disinfect MPs to avoid unintentionally taking the virus home. The video of the campaign had 98 visualizations.

Fifty-one of the fifty-three HCWs of the unit participated in the survey [attending physicians (n=7), cleaning staff (n=5), nurses (n=7), nursing assistants (n=17), physiotherapists (n=5), resident doctors/fellows (n=10)] and responded the questionnaire. Nine (17.6%) had covered their MPs with plastic kitchen wrap in an attempt to facilitate disinfection. Eleven (21.6%) did not remember the educational campaign and three (5.9%) answered that the campaign did not change their behaviour. Only four (7.8%) did not believe that the virus could remain on MPs and one (2%) did not believe that the virus could remain on the hands; 98% reported washing their hands more often since the beginning of the pandemic (Table 1). Twenty-two COVID-19 patients were hospitalized in the unit during the study period, 11 (55%) had positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR in nasopharynx and oropharynx secretions and 20 (91%) had lung computed-tomography suggestive of COVID-19.

Table 1. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) on mobile phones (MPs), and healthcare workers’ ideas on hand hygiene and the use of mobile phones during the pandemic.

| RT-PCR result / Answer to the questionnaire | Attending physician (n=7) | Cleaning staff (n=5) | Nurse (n=7) | Nursing assistant (n=17) | Physiotherapist (n=5) | Resident/ fellow (n=10) | Total (n=51) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive RT-PCR on mobile phones | 0 | 0 | 1 (14.3%) | 1 (5.9%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (3.9%) |

| Believes SARS-CoV-2 can stay on hands | 7 (100%) | 4 (80%) | 7 (100%) | 16 (94.1%) | 5 (100%) | 10 (100%) | 49 (96%) |

| Increased hand-hygiene after COVID-19 | 6 (85.7%) | 5 (100%) | 7 (100%) | 17 (100%) | 5 (100%) | 10 (100%) | 50 (98%) |

| Believes SARS-CoV-2 can remain on MPs | 7 (100%) | 4 (80%) | 7 (100%) | 14 (82.3%) | 5 (100%) | 10 (100%) | 47 (92.1%) |

| Increased cleaning of MP after COVID-19 | 6 (85.7%) | 5 (100%) | 7 (100%) | 16 (94.1%) | 5 (100%) | 9 (90%) | 48 (94.1%) |

Fifty-one MP swabs were collected, two were positive by RT-PCR (3.9%), with Cycle threshold (Ct ) values of 34 and 36, and in both cases the E-gene was detected. The two RT-PCR-positive samples were isolated in viral cultures. The sample with Ct 34 showed CE on the third day, but the subsequent RT-PCR of this isolate was negative. The isolate with Ct 36 did not show CE, and the subsequent RT-PCR of this isolate was negative, as well. The supernatant from both cultures was monitored for 14 days without observing any other CE. The swabs that had a positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR corresponded to HCWs with high exposure to patients with COVID-19 (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

In this study, although most HCWs believed on the importance of cross transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and they increased the adherence to hand hygiene and MP disinfection during the pandemic, we identified SARS-CoV-2 on two MPs. Our findings suggest the need for a universal policy in the infection control guidelines on how to care for electronic devices in the hospital. Little is known about the permanence of viruses on MPs or their potential for cross-contamination. A study of MPs from HCWs of a pediatric unit6 found RNA viruses in 38.5% of the cases (42∕109); predominantly of norovirus (n=39).

In addition, two samples taken from continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) helmets that were worn by patients with confirmed COVID-19, presenting with 10 or more days of symptoms and who tested positive by RT-PCR despite the fact that the surfaces be cleaned twice a day1. Pre-symptomatic patients with COVID-19 can also contaminate their surroundings. A study of quarantined asymptomatic student bedrooms showed that 8/22 (36%) of the surfaces, including bedding, were positive. The students developed COVID-19 later7. Another study has recently shown that under controlled conditions, SARS-CoV-2 may persist on glass surfaces for 28 days and this is exactly the type of material used on the MPs touchscreens8.

This study has limitations. It is unclear what is the best method to collect the SARS-CoV-2 from MPs. Furthermore, the Cts found are high, corresponding to low viral loads9, even though the late amplification may have been caused by freezing and thawing the samples10.

CONCLUSIONS

Although most HCWs believed in the importance of cross-transmission and increased adherence to hand hygiene and disinfection of MPs during the pandemic, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in two MPs. Our results suggest the need for a universal policy in infection control guidelines on how to care for electronic devices in the hospital.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank all the health workers and scientists fighting anonymously every day during the pandemic.

Footnotes

FUNDING: This work was this project was partially supported by a Medical Research Council-Sao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) CADDE partnership award (MR/S0195/1 and FAPESP 18/14389-0). Also it was supported by using materials from LIM-49 Bacteriology Laboratory from the Universidade de Sao Paulo.

REFERENCES

- 1.Colaneri M, Seminari E, Novati S, Asperges E, Biscarini S, Piralla A, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 RNA contamination of inanimate surfaces and virus viability in a health care emergency unit. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:1094.e1–1094.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panigrahi SK, Pathak VK, Kumar MM, Raj U, Priya PK. Covid-19 and mobile phone hygiene in healthcare settings. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5:e002505. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lei H, Ye F, Liu X, Huang Z, Ling S, Jiang Z, et al. SARS-CoV-2 environmental contamination associated with persistently infected COVID-19 patients. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2020;14:688–699. doi: 10.1111/irv.12783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park WB, Kwon NJ, Choi SJ, Kang CK, Choe PG, Kim JY, et al. Virus isolation from the first patient with SARS-CoV-2 in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e84. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pillet S, Berthelot P, Gagneux-Brunon A, Mory O, Gay C, Viallon A, et al. Contamination of healthcare workers’ mobile phones by epidemic viruses. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:456.e1–456.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang FC, Jiang XL, Wang ZG, Meng ZH, Shao SF, Anderson BD, et al. Detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 RNA on surfaces in quarantine rooms. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:2162–2164. doi: 10.3201/eid2609.201435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riddell S, Goldie S, Hill A, Eagles D, Drew TW. The effect of temperature on persistence of SARS-CoV-2 on common surfaces. 145Virol J. 2020;17 doi: 10.1186/s12985-020-01418-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bullard J, Dust K, Funk D, Strong JE, Alexander D, Garnett L, Boodman C, et al. Predicting infectious SARS-CoV-2 from diagnostic samples. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2663–2666. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization Laboratory testing for 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in suspected human cases. [cited 2021 Aug 23]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/10665-331501.