Abstract

Discovery of genotypic markers associated with increased transmissibility in Mycobacterium tuberculosis would represent an important step in advancing mycobacterial virulence studies. M. tuberculosis strains may be classified into one of three genotypes on the basis of the presence of specific nucleotide substitutions in codon 463 of the katG gene (katG-463) and codon 95 of the gyrA gene (gyrA-95). It has previously been reported that two of these three genotypes are associated with increased IS6110-based clustering, a potential proxy of virulence. We designed a case-control analysis of U.S.-born patients with tuberculosis in San Francisco, Calif., between 1991 and 1997 to investigate associations between katG-463 and gyrA-95 genotypes and epidemiologically determined measures of strain-specific infectivity and pathogenicity and IS6110-based clustering status. We used a new class of molecular probes called molecular beacons to genotype the isolates rapidly. Infectivity was defined as the propensity of isolates to cause tuberculin skin test conversions among named contacts, and pathogenicity was defined as their propensity to cause active disease among named contacts. The molecular beacon assay was a simple and reproducible method for the detection of known single nucleotide polymorphisms in large numbers of clinical M. tuberculosis isolates. The results showed that no genotype of the katG-463- and gyrA-95-based classification system was associated with increased infectivity and pathogenicity or with increased IS6110-based clustering in San Francisco during the study period. We speculate that molecular epidemiologic studies investigating clinically relevant outcomes may contribute to the knowledge of the significance of laboratory-derived virulence factors in the propagation of tuberculosis in human communities.

The epidemiologic and clinical consequences of infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis are dependent on an interplay of host, environmental, and bacterial factors. In contrast to our understanding of host and environmental influences on infection and disease (1, 3, 6, 9, 11), little is known about the bacterial factors that contribute to these processes. Two bacterial properties that affect transmissibility and virulence can be epidemiologically and clinically measured: (i) infectivity, the capacity of the organism to establish an infection in the human host, and (ii) pathogenicity, the capacity of the bacterium to produce disease.

Recent reports have suggested that certain differences in the epidemiology and the apparent virulence of specific M. tuberculosis strains can be explained by the genetic variability of the organism. For example, an M. tuberculosis strain that was found to be highly transmissible in humans also appears to grow more rapidly than virulent laboratory strains in mice (15). In a study of selected M. tuberculosis isolates from Texas and New York, specific genotypes were associated with increased rates of IS6110-based clustering, a potential measure of increased virulence (12). In this study, M. tuberculosis isolates were classified into three genotypic groups on the basis of the presence of single nucleotide polymorphisms in codon 463 of the katG gene (katG-463) and codon 95 of the gyrA gene (gyrA-95). If confirmed, the discovery of three distinct M. tuberculosis lineages with variable epidemiologic and clinical manifestations would have important implications for public health control strategies, studies of bacterial virulence, and mathematical modeling of tuberculosis epidemiology.

We examined the ability of newly described reporter molecules called molecular beacons (13) to be used in an assay that would rapidly determine the katG-463 and gyrA-95 genotypes of M. tuberculosis isolates. Molecular beacons are detector probes that fluoresce when they hybridize to amplified copies of a target sequence synthesized in real-time PCR assays (10, 14) and that are able to distinguish sequence differences as small as a single nucleotide substitution. In the present study we investigated the associations between the three katG-463 and gyrA-95 genotypes and the epidemiologically and clinically measured properties of infectivity and pathogenicity in a population-based sample of tuberculosis patients in San Francisco, Calif. We also studied the association between katG-463 and gyrA-95 genotypes and IS6110-based clustering.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects.

The study base was all patients with tuberculosis reported in San Francisco from 1991 through 1997 (n = 2,096). Epidemiologic data were collected prospectively on a routine basis as a component of the tuberculosis control program of the Division of Tuberculosis Control, San Francisco Department of Public Health. The information that was collected included age at diagnosis, sex, race or ethnicity, country of birth, date of diagnosis, and sputum smear status. For patients for whom tuberculosis was diagnosed prior to 1993, information on human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serostatus was obtained by linking the tuberculosis registry to records from the San Francisco AIDS Office. HIV infection status data for patients whose tuberculosis was reported after 1993 were obtained from the Report of a Verified Case of Tuberculosis. Individuals for whom HIV serostatus was unknown were considered to be HIV negative because these patients were less likely to have risk factors for HIV infection. Contact investigation data were collected by standard methods by trained disease-control investigators for all patients treated by the Division of Tuberculosis Control. Contact investigations for patients receiving care elsewhere were carried out either by the treating physician or by tuberculosis control personnel. M. tuberculosis isolates were collected from patients, DNA was extracted, and the isolates were fingerprinted by IS6110-based restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis as described previously (16). Additional polymorphic guanine-cytosine-rich repetitive sequence (PGRS) fingerprinting was performed on isolates with fewer than six IS6110-hybridizing bands.

Epidemiologic determination.

Measurement of infectivity and pathogenicity was done by using contact investigation data for each patient and the patient’s corresponding isolate. Infectivity was determined by calculating the proportion of contacts with a positive tuberculin skin test result plus those found to have tuberculosis at the time of contact investigation among contacts who were not lost to follow-up after initial screening. Pathogenicity was determined by calculating the proportion of contacts found to have tuberculosis at the time of contact investigation plus those who subsequently developed tuberculosis during the study period among all screened contacts. Because foreign-born populations have a high prevalence of tuberculin skin test positivity and the contacts of foreign-born patients are also likely to be foreign born (2, 7), there was a high probability that the infecting strain in these contacts was not related to the strain in the case patient. We therefore limited the study to patients who were born in the United States and who had at least one named contact. An IS6110-clustered strain was defined as a strain whose IS6110 RFLP pattern had an identical or a one-band different IS6110 RFLP pattern among isolates from all patients with tuberculosis in San Francisco during the study period. For statistical analyses, each clustered strain was represented only once.

Molecular beacon genotyping.

DNA samples that had previously been extracted and frozen were used for each study subject except for 21 (5.0%) of 419 individuals for whom cultured specimens but not stored DNA were available. For the cultured specimens, DNA was extracted from Lowenstein-Jensen slants. Four molecular beacons were designed. Each contained a 15- to 19-nucleotide probe region that was perfectly complementary to one of the four possible katG-463 or gyrA-95 alleles described previously (12). Molecular beacons were synthesized from modified oligonucleotides. The quencher 4-(4′-dimethylaminophenylazo)-benzoic acid (DABCYL; Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) was co-valently linked to one arm, and either fluorescein or tetrachlorofluorescein was linked to the other arm. A detailed protocol is available on the Internet (7a.). The molecular beacon sequences were fluorescein-5′-CGAGGCCTACGACAcCCTGGTGCGCCTCG-3′-DABCYL (gyrA-95 ACC), tetrachlorofluorescein-5′-CGAGGCCTACGACAgCCTGGTGCGCCTCG-3′-DABCYL (gyrA-95 AGC), fluorescein-5′-CGAGGTCCCGATGCCcGGATCTCCTCG-3′-DABCYL (katG-463 CGG), and tetrachlorofluorescein-5′-CGAGGGATGCCaGGATCTGGCCTCG-3′-DABCYL (katG-463 CTG), where underlines indicate the arm sequences and lowercase letters identify the nucleotide that is complementary to the single nucleotide polymorphism.

PCR assays were performed in sealed 96-well microtiter plates (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.). Each M. tuberculosis DNA sample was aliquoted into paired wells containing 1× PCR buffer and 2.5 U of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer) with 4 mM MgCl2, 0.5 μM each appropriate gyrA (5′-GACCGCAGCCACGCCAAGT-3′ and 5′-CGTCGATTTCCTCAGCATCTCCA-3′) or katG (5′-GCGAGATACCTTGGGCCGCTGGTC-3′ and 5′-CGCCGCCGCGCTTGTCGCTACC-3′) primer, and 0.13 to 0.15 μM each appropriate molecular beacon in a total volume of 50 μl. Each paired well contained molecular beacons for both possible target alleles for one of the two genes being assayed. One contained the molecular beacons gyrA-95 ACC and gyrA-95 AGC and the other contained the molecular beacons katG-463 CGG and katG-463 CTG. Amplifications were performed with a spectrofluorometric thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems 7700 Prism; Perkin-Elmer) for 40 cycles, as follows: denaturation for 30 s at 95°C and then annealing and extension for 60 s at 64°C. The fluorescent signal was measured independently during the 60-s annealing and extension step for each molecular beacon and was automatically plotted for each sample. Because each well was expected to contain one of two possible target alleles, one molecular beacon was expected to hybridize to the amplicon in every PCR. Hybridization resulted in a characteristic increasing fluorescent signal with an emission spectrum that was specific for one of the two molecular beacons present in the reaction tube. Negative and positive controls for each allele were included in every assay.

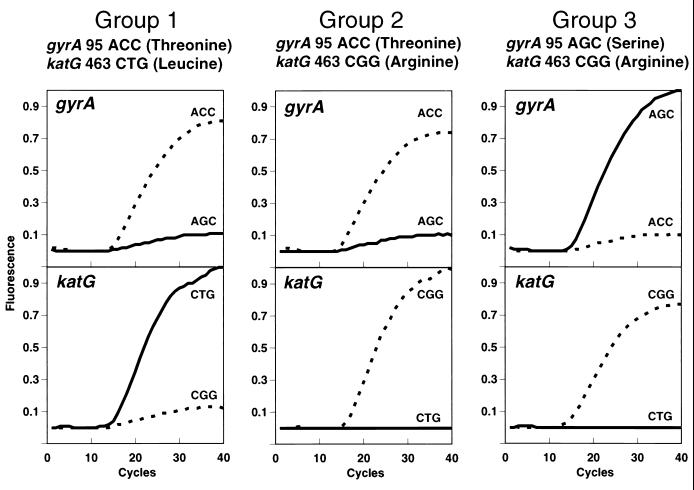

Samples were assigned to one of three genotypes according to which of the katG-463 and which of the gyrA-95 molecular beacons gave a signal (see Fig. 1): group 1 (katG-463 CTG, gyrA-95 ACC), group 2 (katG-463 CGG, gyrA-95 ACC), or group 3 (katG-463 CGG, gyrA-95 AGC). The results for isolates in which fluorescence was observed in only one of the two paired wells were classified as indeterminate. Isolates that reproducibly lacked fluorescence in either well were confirmed to contain insufficient DNA and were excluded from further analysis. Interpretation of results and assignment of each isolate to group 1, group 2, or group 3 were done by investigators blinded to the identities of the samples.

FIG. 1.

Genotyping by molecular beacon sequence analysis. Each PCR well contained two molecular beacons complementary to both possible alleles of either katG-463 or gyrA-95. One molecular beacon for each allele was labeled with fluorescein (broken line), and the other molecular beacon in the pair was labeled with tetrachlorofluorescein (solid line). Characteristic sequence-dependent fluorescent curves are shown for each group. The presence of a specific nucleotide sequence was indicated by an increase in fluorescence of the complementary molecular beacon during a real-time PCR. Group 1 strains were defined by fluorescence of the katG-463 CTG tetrachlorofluorescein and the gyrA-95 ACC fluorescein molecular beacons, group 2 strains were defined by fluorescence of the katG-463 CGG fluorescein and gyrA-95 ACC fluorescein molecular beacons, and group 3 strains were defined by fluorescence of the katG-463 CGG fluorescein and gyrA-95 AGC tetrachlorofluorescein molecular beacons.

Statistical analyses.

Comparison of patient characteristics for differences in proportions or means was done with EpiInfo software (version 6.12). Contingency tables of infectivity, pathogenicity, IS6110-based clustering status, and katG-463 and gyrA-95 genotypes were constructed for analysis. Chi-square tests of an association between the three genotypes and the outcome measures on 2 degrees of freedom and odds ratios with exact 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the respective comparisons were also calculated with EpiInfo software. An α- level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

RESULTS

There were 757 (36.1%) U.S.-born patients, of whom 523 (69.1%) had named at least one contact. These patients comprised the eligible study subjects and were more likely than ineligible patients to be female and Asian (data not shown). Of the eligible patients, 82 (15.7%) were culture-negative patients and 22 (4.2%) were culture-positive patients for whom DNA or culture was no longer available. The eligible patients were younger and were more likely than the remaining 419 patients (528 isolates) to be female, Asian, and HIV negative and to ever have had a positive sputum smear result (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of characteristics of U.S.-born patients in the study sample and eligible study subjects for whom there was no DNA sample

| Characteristic | Study sample (n = 415) | Eligible subjects without DNA (n = 108) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age (yr) | 44.2 (16.3) | 35.1 (22.0) | <0.05a |

| No. (%) of subjects | |||

| Female | 84 (20.2) | 38 (35.2) | <0.05a |

| Male | 331 (79.8) | 70 (64.8) | |

| Asian | 22 (5.3) | 20 (18.5) | <0.05a |

| Black | 164 (39.5) | 34 (31.5) | 0.13 |

| Hispanic | 33 (8.0) | 12 (11.1) | 0.30 |

| White | 193 (46.5) | 42 (38.9) | 0.16 |

| Other | 3 (0.7) | ||

| HIV positive | 188 (45.3) | 25 (23.1) | <0.05a |

| HIV negativeb | 227 (54.7) | 83 (76.9) | |

| Ever smear positive | 227 (54.7) | 26 (24.1) | <0.05a |

| Always smear negative | 68 (16.4) | 49 (45.4) | <0.05a |

| Fewer than three sputum smears | 120 (29.0) | 33 (30.5) | 0.74 |

Denotes a statistically significant difference at an α-level of 0.05.

Includes subjects whose HIV status is unknown.

The katG-463 and gyrA-95 genotypes of all 528 M. tuberculosis isolates were determined by the molecular beacon assay (Fig. 1). Thirteen (2.5%) samples failed to produce a fluorescent signal in the presence of any of the four molecular beacons. Reaction products from these assays did not contain sufficient DNA for visualization with ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels, confirming that these samples either had insufficient DNA for detection by PCR or contained PCR inhibitors. Data for the four study subjects corresponding to these 13 samples were excluded from further analysis. Of the remaining 515 samples, 508 (98.6%) were assigned to one of the three genotypes. Seven (1.4%) samples with indeterminate results gave a fluorescent signal in only one of the two paired wells. A 10% sample of all DNA samples, including all those with indeterminate results plus others selected at random (n = 53), were assayed a second time, and the results for all samples were concordant with those of the first assay. Further evidence of the reproducibility of the molecular beacon assay was the complete internal consistency between genotype and IS6110-based clustering status. The results of automated DNA sequencing of the regions surrounding katG-463 and gyrA-95 in 12 (22.6%) of these strains were in complete agreement with the genotype designations of the molecular beacon assay. Because all of the samples with indeterminate results were from individuals for whom at least one other DNA sample had been extracted from the same culture, the isolates from these individuals were classified into one of the three genotypes by using the nonindeterminate result.

The results of the molecular beacon assays confirmed the presence of three distinct katG-463 and gyrA-95 genotypes and did not indicate the presence of a fourth possible genotype (katG-463 CTG and gyrA-95 AGC). Of the isolates from the 415 individuals, 61 (14.7%; 95% CI = 11.3,18.1) were classified as group 1, 270 (65.1%; 95% CI = 60.5,69.7) were classified as group 2, and 84 (20.2%; 95% CI = 16.3,24.1) were classified as group 3. For 45 (9.2%) individuals there were multiple DNA samples, and the results for 43 (95.6%) of these individuals were concordant, further demonstrating the reproducibility of the molecular beacon assay. For each of the two individuals with discordant results, two isolates had been taken at different times. These patients had serial infections with two different strains, as demonstrated by analysis of the IS6110 patterns for each isolate (data not shown). For these patients the genotype of the initial isolate was used in the analyses.

There were a total of 4,104 named contacts for the study sample. Among these, 3,780 (92.1%) underwent initial screening by tuberculosis control personnel. The remaining 324 (7.9%) either refused treatment or were referred out of jurisdiction. Among those initially screened, 3,611 (95.5%) had complete follow-up. The mean number of contacts who had been screened (9.1 per case patient) and the mean number of contacts who had complete follow-up (8.7 per case patient) were not significantly different. In both instances, there were 1.8 close contacts per case patient and 7.3 or 6.9 not close contacts per case patient, respectively. Because the results did not differ significantly when the analyses were restricted to close contacts, results for all types of contacts were used in this study.

The measures of virulence were categorized a priori into low infectivity (≤30.0%) and high infectivity (>30.0%) and into low pathogenicity (≤10.0%) and high pathogenicity (>10.0%). These threshold levels were selected on the basis of current knowledge of the natural history of tuberculosis (5). There were 38 (9.2%) patients for whom infectivity measures were not calculated because their contacts had incomplete follow-up and 29 (7.0%) patients for whom pathogenicity measures were not calculated because their contacts had not undergone initial screening. The demographic and clinical characteristics of these patients were not significantly different from those of patients who were included in these analyses (data not shown). The results show that neither infectivity nor pathogenicity was significantly associated with the katG-463 and gyrA-95 genotypes (Table 2). These results were not altered in analyses stratified by type of contact (close or not close), sensitivity analyses with various threshold levels for low and high infectivities (50.0 and 70.0%, respectively) and low and high pathogenicities (30.0 and 60.0%, respectively), and analyses that excluded patients with zero and 100.0% measures (data not shown). To assess the potential confounding effects of patient characteristics, we evaluated these variables according to genotype (Table 3) and the outcome measures of infectivity and pathogenicity (Table 4). Patient characteristics were not associated with low and high infectivities or with low and high pathogenicities. Patients infected with group 2 strains were significantly younger than those infected with group 1 strains. Patients infected with group 1 strains were more likely to be of Asian descent than those infected with group 2 or group 3 strains.

TABLE 2.

Infectivity, pathogenicity, and IS6110-based clustering according to katG-463 and gyrA-95 genotypea

| Parameter | No. of patients infected with isolates in group:

|

χ2b (P) | Odds ratio (95% CI) for genotype group comparison

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 vs 2 | 1 vs 3 | 2 vs 3 | ||

| Infectivity | 0.85 (0.65) | 0.88 (0.45,1.68) | 0.73 (0.33,1.57) | 0.83 (0.48,1.44) | |||

| >30.0% | 20 | 99 | 34 | ||||

| ≤30.0% | 34 | 148 | 42 | ||||

| Pathogenicity | 0.16 (0.92) | 0.92 (0.30,2.43) | 0.82 (0.23,2.68) | 0.88 (0.39,2.14) | |||

| >10.0% | 6 | 29 | 10 | ||||

| ≤10.0% | 50 | 223 | 68 | ||||

| IS6110 | |||||||

| ≥2 people | 0.76 (0.68) | 1.09 (0.52,2.28) | 1.43 (0.57,3.61) | 1.31 (0.60,2.90) | |||

| Clustered | 22 | 48 | 16 | ||||

| Unique | 26 | 62 | 27 | ||||

| ≥5 people | 0.08 (0.96) | 1.07 (0.38,2.87) | 1.17 (0.34,4.07) | 1.09 (0.40,3.22) | |||

| Clustered | 9 | 20 | 8 | ||||

| Unique | 26 | 62 | 27 | ||||

| ≥20 people | 0.50 (0.78) | 2.38 (0.03,190.14) | 1.04 (0.01,84.50) | 0.44 (0.01,35.44) | |||

| Clustered | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Unique | 26 | 62 | 27 | ||||

Contingency tables are presented without marginal totals. The total number of patients used for determination of infectivity was 377, which excluded 38 patients for whom follow-up screening of contacts was incomplete. The total number of patients used for the determination of pathogenicity was 386, which excluded 29 patients for whom initial screening of named contacts was incomplete. Analyses of IS6110-based clustering were performed for all unique isolates and clusters of 2 or more people (201 distinct patterns), clusters of 5 or more people (152 distinct patterns), and clusters of 20 or more people (118 distinct patterns).

Two degrees of freedom.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of patient characteristics according to katG-463 and gyrA-95 genotype of corresponding isolate

| Characteristic | Group 1 (n = 61) | Group 2 (n = 270) | Group 3 (n = 84) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age (yr) | 49.8 (16.8) | 42.6 (16.0) | 45.2 (15.9) | <0.05ab |

| No. (%) of subjects | ||||

| Female | 10 (16.4) | 61 (22.6) | 13 (15.5) | 0.26 |

| Male | 51 (83.6) | 209 (77.4) | 71 (84.5) | |

| Asian | 9 (14.8) | 12 (4.4) | 1 (1.2) | <0.05ac |

| Black | 20 (32.8) | 108 (40.0) | 35 (41.7) | 0.51 |

| Hispanic | 4 (6.6) | 22 (8.1) | 7 (8.3) | 0.91 |

| White | 28 (45.9) | 126 (46.7) | 40 (47.6) | 0.98 |

| Other | 2 (0.7) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| HIV positive | 30 (49.2) | 127 (47.0) | 31 (36.9) | 0.21 |

| HIV negatived | 31 (50.8) | 143 (53.0) | 53 (63.1) | |

| Ever smear positive | 38 (62.3) | 146 (54.1) | 43 (51.2) | 0.39 |

| Always smear negative | 7 (11.5) | 46 (17.0) | 15 (17.9) | 0.52 |

| Fewer than three sputum smears | 16 (26.2) | 78 (28.9) | 26 (31.0) | 0.83 |

| Infectivity | ||||

| Mean % (SD) | 29.1 (35.0) | 30.7 (36.9) | 35.6 (38.2) | 0.53 |

| No. (%) of patients highe | 20 (37.0) | 99 (40.1) | 34 (44.7) | 0.65 |

| No. (%) of patients lowf | 34 (63.0) | 148 (59.9) | 42 (55.3) | |

| Pathogenicity | ||||

| Mean % (SD) | 5.4 (19.7) | 5.5 (18.2) | 7.1 (21.8) | 0.80 |

| No. (%) of patients highg | 6 (10.7) | 29 (11.5) | 10 (12.8) | 0.92 |

| No. (%) of patients lowh | 50 (89.3) | 223 (88.5) | 68 (87.2) | |

| Mean no. of contacts | ||||

| Named | 11.9 (27.0) | 8.8 (20.1) | 11.9 (36.2) | 0.50 |

| Screened | 11.2 (26.8) | 8.0 (19.9) | 11.3 (36.2) | 0.50 |

| Followed up | 11.1 (26.5) | 7.5 (18.3) | 10.9 (36.0) | 0.37 |

Denotes a statistically significant difference at an α-level of 0.05.

For group 1 versus group 2, P = 0.002.

For group 1 versus group 2, P = 0.007; for group 1 versus group 3, P = 0.004.

Includes subjects whose HIV status is unknown.

Patients demonstrating high (>30.0%) infectivity.

Patients demonstrating low (≤30.0%) infectivity.

Patients demonstrating high (>10.0%) pathogenicity.

Patients demonstrating low (≤10.0%) pathogenicity.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of patient characteristics according to the outcome measures low and high infectivities and low and high pathogenicities

| Characteristic | Infectivity

|

Pathogenicity

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (n = 224) | High (n = 153) | P value | Low (n = 341) | High (n = 45) | P value | |

| Mean (SD) age (yr) | 45.0 (16.8) | 42.7 (15.7) | 0.18 | 44.6 (16.5) | 39.7 (15.6) | 0.06 |

| No. (%) of subjects | ||||||

| Group 1 | 34 (15.2) | 20 (13.1) | 0.57 | 50 (14.7) | 6 (13.3) | 0.81 |

| Group 2 | 148 (66.1) | 99 (64.7) | 0.78 | 223 (65.4) | 29 (64.4) | 0.90 |

| Group 3 | 42 (18.8) | 34 (22.2) | 0.41 | 68 (19.9) | 10 (22.2) | 0.72 |

| Female | 46 (20.5) | 34 (22.2) | 0.70 | 71 (20.8) | 10 (22.2) | 0.83 |

| Male | 178 (79.5) | 119 (77.8) | 270 (79.2) | 35 (77.8) | ||

| Asian | 12 (5.4) | 9 (5.9) | 0.83 | 19 (5.6) | 2 (4.4) | 0.97 |

| Black | 79 (35.3) | 68 (44.4) | 0.07 | 126 (37.0) | 23 (51.1) | 0.07 |

| Hispanic | 16 (7.1) | 14 (9.2) | 0.48 | 28 (8.2) | 3 (6.7) | 0.95 |

| White | 114 (50.9) | 62 (40.5) | 0.05 | 165 (48.4) | 17 (37.8) | 0.18 |

| Other | 3 (1.3) | 3 (0.9) | ||||

| HIV positive | 107 (47.8) | 62 (40.5) | 0.16 | 161 (47.2) | 15 (33.3) | 0.08 |

| HIV negativea | 117 (52.2) | 91 (59.5) | 180 (52.8) | 30 (66.7) | ||

| Ever smear positive | 120 (53.6) | 93 (60.8) | 0.17 | 192 (56.3) | 25 (55.6) | 0.92 |

| Always smear negative | 40 (17.9) | 19 (12.4) | 0.15 | 50 (14.7) | 10 (22.2) | 0.19 |

| More than three sputum smears | 64 (28.6) | 41 (26.8) | 0.71 | 99 (29.0) | 10 (22.2) | 0.34 |

| Mean no. of contacts (SD) | ||||||

| Named | 11.5 (29.6) | 9.4 (20.5) | 0.45 | 10.9 (27.3) | 6.9 (11.8) | 0.33 |

| Screened | 10.9 (29.5) | 8.6 (20.1) | 0.40 | 10.2 (27.1) | 6.4 (10.8) | 0.35 |

| Followed up | 10.5 (29.0) | 8.2 (18.0) | 0.38 | 9.7 (26.2) | 6.4 (10.9) | 0.40 |

Includes subjects whose HIV status is unknown.

The composition of the contacts may influence the measures of infectivity and pathogenicity. An analysis of characteristics of all the contacts was not possible because this information was not routinely collected during the contact investigation. However, information was available for contacts who were found to have tuberculosis at the time of contact investigation or who subsequently progressed to disease during the study period. Analyses restricted to the subset of contacts with disease demonstrated no highly statistically significant differences in patient characteristics between the low- and high-pathogenicity groups (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Comparison of characteristics of contacts with tuberculosis according to low and high pathogenicities

| Characteristic | Low pathogenicity (n = 28) | High pathogenicity (n = 75) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age (yr) | 43.5 (13.1) | 35.5 (19.1) | 0.13 |

| No. (%) of subjects | |||

| Female | 4 (14.3) | 26 (34.7) | 0.04 |

| Male | 24 (85.7) | 49 (65.3) | |

| Group 1 | 2 (7.1) | 12 (16.0) | 0.40 |

| Group 2 | 18 (64.3) | 51 (68.0) | 0.72 |

| Group 3 | 8 (28.6) | 12 (16.0) | 0.15 |

| Asian | 4 (14.3) | 3 (4.8)a | 0.25 |

| Black | 7 (25.0) | 28 (44.4) | 0.08 |

| Hispanic | 5 (17.9) | 4 (6.3) | 0.19 |

| Whiteb | 12 (42.9) | 28 (44.4) | 0.89 |

| Other | |||

| HIV positive | 10 (35.7) | 33 (52.4)a | 0.15 |

| HIV negativec | 18 (64.9) | 30 (47.6) | |

| Ever smear positive | 12 (42.9) | 23 (36.5)a | 0.57 |

| Always smear negative | 14 (50.0) | 25 (39.7) | 0.36 |

| Fewer than three sputum smears | 2 (7.1) | 15 (23.8) | 0.06 |

| Foreign-born | 7 (25.0) | 6 (9.5)a | 0.10 |

| U.S.-born | 21 (75.0) | 57 (90.5) |

Denominator was 63 due to missing values for 12 patients who had active tuberculosis at the time of contact investigation and who were referred out of jurisdiction after follow-up.

Includes one patient of unknown race or ethnicity.

Includes subjects whose HIV status is unknown.

An earlier study found that group 3 strains were less likely to be present in IS6110-based clusters than group 1 or group 2 strains (12). We performed similar analyses by comparing representative IS6110-based cluster strains and their katG-463 and gyrA-95 genotypes. We found no association between genotype and cluster status, even when the analysis was restricted to clusters of ≥5 individuals and clusters of ≥20 individuals (Table 2). These results held when clustering was determined with the use of the secondary marker PGRS for strains with fewer than six IS6110-hybridizing bands (data not shown). Because the association that we found was negative in contrast to the previous positive finding, we performed power calculations for our study (Table 6). We determined that our study had sufficient statistical power above 90.0% to detect the odds ratios reported previously (12). Furthermore, our study had sufficient power to detect odds ratios as low as 3.5 had they been present.

TABLE 6.

Power calculations for the IS6110-based clustering and katG-463 and gyrA-95 genotype analyses

| Character | Group 1 and group 2 vs group 3 | Group 1 vs group 3 | Group 2 vs group 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 86 | 38 | 64 |

| Control: case ratio | 1.34 | 1.39 | 1.39 |

| % Exposed in controls | 76.5 | 49.1 | 69.7 |

| % Power if: | |||

| ORa = 2.0 | 44.3 | 35.5 | 41.7 |

| OR = 3.0 | 74.8 | 67.6 | 72.6 |

| OR = 4.0 | 87.2 | 83.5 | 85.8 |

| OR = OR of previous studyb | 97.7c | 97.6d | 98.0e |

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that molecular beacon assays are a reproducible and accurate method of detecting known single nucleotide polymorphisms among a large number of bacterial isolates. Amplicon detection was carried out in sealed 96-well plates; this simplified the analysis, eliminated an important source of assay contamination, and permitted simultaneous testing of multiple samples. We have confirmed that the nucleotide polymorphism in codon 463 of the katG gene and codon 95 of the gyrA gene can be used to classify M. tuberculosis strains into three genotypes. However, we did not find an association between this trichotomous classification system and epidemiologically and clinically measured characteristics of infectivity and pathogenicity. We also did not find an association between genotype and increased IS6110-based clustering. These results are in contrast to the results of Sreevatsan and colleagues (12), who found the group 3 genotype to be less associated with IS6110-based clustering, suggesting an attenuation of transmissibility and virulence in these strains.

The differences in our findings may be due to differences in the selection of the respective study samples. It is possible that the katG-463 and gyrA-95 genotype is associated with the geographic origin of M. tuberculosis strains rather than evolutionary attenuation. If so, then the association between genotype and measures of transmissibility and virulence will depend on the composition of the human population in which they are studied and the transmission dynamics in that population. This was suggested by our finding that group 1 strains were significantly associated with individuals of Asian descent and with older individuals. Differences in age, sex, race or ethnicity, and HIV status were also present between our study sample and eligible subjects who were excluded because their isolates could not be cultured or there was no M. tuberculosis DNA available for analysis. It is possible that the differences in our findings are a reflection of the patients selected for the study.

The distribution of genotypes according to the number of IS6110 copies revealed by Southern blotting was similar to that found by Sreevatsan and colleagues (12). Our results substantiate the proposal for an evolutionary scheme in which the pattern of IS6110 insertions diversified after the three katG-463 and gyrA-95 genotypes branched off from a common ancestor.

There are some limitations to this study. First, if culture negativity is the result of infection with less transmissible and less virulent strains, it is possible that the inability to determine the genotypes of these strains generated a selection bias in the low-infectivity and low-pathogenicity groups. Furthermore, it was not possible to calculate infectivity and pathogenicity for patients who were excluded from the study sample because they did not name any contacts. However, it is unlikely that this selection would be related to the katG-463 and gyrA-95 genotype.

Another limitation is that potentially important covariate data that may affect measures of infectivity and pathogenicity were not available for this retrospectively designed study, including information on the contacts of the case patients. Had such data been available, they may have allowed a more complete assessment of the association between the three genotypes and the measures of transmissibility and virulence. For example, if a contact had a history of vaccination with BCG, then a positive tuberculin skin test may not reflect the transmission of M. tuberculosis from the source patient. To minimize this probability, we limited our study to U.S.-born patients on the basis of evidence that U.S.-born patients associate predominately with people who were also born in the United States (2, 7).

Another potential limitation involved the variable numbers of named contacts per case patient, which affected the non-Gaussian distribution of infectivity and pathogenicity measures. It is possible that the categorization of the likely underlying continuous properties of these measures obscured any associations with the katG-463 and gyrA-95 genotype. To analyze the impact of variable numbers of named contacts for each case patient, we compared, for each genotype, infectivity and pathogenicity using all contacts. Accounting for the codependence of contacts, there was no association with the proportion of contacts who were infected or who had disease (data not shown). Furthermore, sensitivity analyses with different threshold levels and with the exclusion of zero and 100% measures did not alter the results, suggesting that such categorization was not an important problem in this study.

Lastly, the true infectivities and pathogenicities of strains may have been obscured by the intervention of chemoprophylaxis for contacts, although adherence to preventive therapy is not likely to be associated with the genotype of the infecting strain. The use of genetic markers in genes that are associated with resistance to antibiotics (8) may have unintentionally skewed the katG-463 and gyrA-95 genotype distribution by antibiotic treatment for tuberculosis or other conditions. However, the katG-463 and gyrA-95 allelic polymorphisms used in this study do not in themselves cause antibiotic resistance and are present in both susceptible and resistant bacteria (12).

In this study we used a molecular beacon assay to rapidly detect small variations in a DNA sequence putatively associated with virulence for an established population-based M. tuberculosis strain collection in San Francisco. A classic epidemiologic study was designed with a unique method of deriving clinically meaningful outcome measures of bacterial virulence, and a postulated association of transmissibility and virulence with a newly identified genetic marker was examined. Given that novel approaches to understanding the molecular basis of bacterial pathogenesis and a renewed interest in M. tuberculosis are beginning to yield a profusion of laboratory-derived virulence factors (4), we speculate that continued investigations of the association between bacterial genotypes and epidemiologically defined phenotypes in natural populations may contribute to our understanding of bacterial factors in the propagation of the tuberculosis epidemic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants AJ-23238 (to J.T.R., S.V.C., and P.M.S.), AI-43268 (to D.A. and A.S.P.), and HL-43521 (to F.R.K.).

We thank the disease control investigators at the Division of Tuberculosis Control in the San Francisco Department of Public Health, Cristina Agasino, and Melvin Javonillo and are grateful for the advice Megan Murray provided in the preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bellamy R, Ruwende C, Corrah T, McAdam K P W J, Whittle H C, Hill A V S. Variations in the NRAMP1 gene and susceptibility to tuberculosis in West Africans. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:640–644. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803053381002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chin D P, DeReimer K, Small P M, Ponce de Leon A, Steinhart R, Schecter G F, Daley C D, Moss A R, Paz E A, Jasmer R M, Agasino C B, Hopewell P C. Interaction of factors contributing to the incidence of tuberculosis in San Francisco. Am J Respir Dis Crit Care Med. 1998;158:1797–1803. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.6.9804029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins F M. Mycobacterial disease, immunosuppression, and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989;2:360–377. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.4.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.George K M, Chatterjee D, Gunawardana G, Welty D, Hayman J, Lee R, Small P L C. Mycolactone: a polyketide toxin from Mycobacterium ulcerans required for virulence. Science. 1999;283:854–857. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5403.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hopewell P C. Mycobacterial diseases. In: Murray J F, Nadel J A, editors. Textbook of respiratory medicine. Philadelphia, Pa: The W. B. Saunders Co.; 1988. pp. 856–915. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Houk V N, Baker J H, Sorensen K, Kent D C. The epidemiology of tuberculosis infection in a closed environment. Arch Environ Health. 1968;16:26–35. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1968.10665011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jasmer R M, Ponce de Leon A, Hopewell P C, Moss A R, Paz E A, Schecter G F, Small P M. Tuberculosis in Mexican-born persons in San Francisco: reactivation, acquired infection, and transmission. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1997;1:536–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7a.Kramer, F. R., S. Tyagi, J. A. M. Vet, and S. A. E. Marras. 1998, posting date. Molecular beacons: hybridization probes for detection of nucleic acids in homogeneous solutions. [Online.] http://www.molecular-beacons.org. [7 April 1999, last date accessed.]

- 8.Musser J M. Antimicrobial agent resistance in mycobacteria: molecular genetic insights. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:496–514. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nardell E A. Tuberculosis in homeless, residential case facilities, prisons, nursing homes, and other close communities. Semin Respir Infect. 1989;4:206–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piatek A S, Tyagi S, Pol A C, Telenti A, Miller L P, Kramer F R, Alland D. Molecular beacon sequence analysis for detecting drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:359–363. doi: 10.1038/nbt0498-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selwyn P A, Hartel D, Lewis V A, Schoenbaum E E, Vermund S H, Klein R S, Walker A T, Friedland G H. A prospective study of the risk of tuberculosis among intravenous drug users with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:545–550. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198903023200901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sreevatsan S, Pan X, Stockbauer K E, Connell N D, Kreiswirth B N, Whittam T S, Musser J M. Restricted structural gene polymorphism in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex indicates evolutionarily recent global dissemination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9869–9874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tyagi S, Kramer F R. Molecular beacons: probes that fluoresce upon hybridization. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:303–308. doi: 10.1038/nbt0396-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tyagi S, Bratu D P, Kramer F R. Multicolor molecular beacons for allele discrimination. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:49–53. doi: 10.1038/nbt0198-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valway S E, Sanchez M P C, Shinnick T F, Orme I, Agerton T, Hoy D, Jones J S, Westmoreland H, Onorato I M. An outbreak involving extensive transmission of a virulent strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:633–639. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803053381001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Embden J D A, Cave M D, Crawford J T, Dale J W, Eisenach K D, Gicquel B, Hermans P, Martin C, McAdam R, Shinnick T M, Small P M. Strain identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by DNA fingerprinting: recommendations for a standardized methodology. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:406–409. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.406-409.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]