Abstract

For many decades, the standard procedure to treat breast cancer included complete dissection of the axillary lymph nodes. The aim was to determine histological node status, which was then used as the basis for adjuvant therapy, and to ensure locoregional tumour control. In addition to the debate on how to optimise the therapeutic strategies of systemic treatment and radiotherapy, the current discussion focuses on improving surgical procedures to treat breast cancer. As neoadjuvant chemotherapy is becoming increasingly important, the surgical procedures used to treat breast cancer, whether they are breast surgery or axillary dissection, are changing. Based on the currently available data, carrying out SLNE prior to neoadjuvant chemotherapy is not recommended. In contrast, surgical axillary management after neoadjuvant chemotherapy is considered the procedure of choice for axillary staging and can range from SLNE to TAD and ALND. To reduce the rate of false negatives during surgical staging of the axilla in pN+ CNB stage before NACT and ycN0 after NACT, targeted axillary dissection (TAD), the removal of > 2 SLNs (SLNE, no untargeted axillary sampling), immunohistochemistry to detect isolated tumour cells and micro-metastases, and marking positive lymph nodes before NACT should be the standard approach. This most recent update on surgical axillary management describes the significance of isolated tumour cells and micro-metastasis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and the clinical consequences of low volume residual disease diagnosed using SLNE and TAD and provides an overview of this yearʼs AGO recommendations for surgical management of the axilla during primary surgery and in relation to neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Key words: breast cancer, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, sentinel LNE, targeted axillary dissection

Introduction

Every year, the Breast Committee of the German Gynaecological Oncology Working Group (AGO) updates its recommendations on the prevention, diagnosis and therapy of breast cancer (Breast Care, 2021, in press; https://www.ago-online.de/ago-kommissionen/kommission-mamma ).

For the first time, the current update on surgical axillary management is going into more detail about the significance of isolated tumour cells and micro-metastasis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) and the clinical consequences of low volume residual disease diagnosed based on SLNE und TAD. This article provides an overview of this yearʼs AGO recommendations ( Tables 1 to 3 ) on surgical management of the axilla in primary surgery and in relation to neoadjuvant chemotherapy 1 .

Table 1 Oxford Levels of Evidence (LoE).

| LOE | Therapy/prevention, aetiology/harm | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|

| 1a | Systematic review (with homogeneity) of randomised controlled trials | Systematic review (with homogeneity) of inception cohort studies; clinical decision rule validated in different populations |

| 1b | Individual randomised controlled trials (with narrow confidence interval) | Individual inception cohort study with ≥ 80% follow-up; clinical decision rule validated in a single population |

| 1c | All or none | All or none case-series |

| 2a | Systematic review (with homogeneity) of cohort studies | Systematic review (with homogeneity) of either retrospective cohort studies or untreated control groups in randomised controlled trials |

| 2b | Individual cohort study (including low quality randomised controlled trials; e.g., < 80% follow-up) | Retrospective cohort study or follow-up of untreated control patients in a randomised controlled trial; derivation of clinical decision rule or validated on split-sample only |

| 2c | “Outcomes” research; ecological studies | “Outcomes” research |

| 3a | Systematic review (with homogeneity) of case-control studies | |

| 3b | Individual case-control study | |

| 4 | Case series (and poor-quality cohort and case-control studies) | Case series (and poor-quality prognostic cohort studies) |

| 5 | Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, or based on physiology, bench research or “first principles” | Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, or based on physiology, bench research or “first principles” |

Table 3 AGO Levels of Recommendation.

| ++ | This examination or therapeutic intervention is of great benefit to the patient, can be unreservedly recommended and should be carried out. |

| + | This examination or therapeutic intervention is of limited benefit to the patient and may be carried out . |

| +/− | This examination or therapeutic intervention has not shown any benefits to date and may be carried out in individual cases . It is not possible to give a clear recommendation based on the current data. |

| − | This examination or therapeutic intervention may be detrimental to the patient and should rather not be carried out . |

| − − | This examination or therapeutic intervention is detrimental and should be avoided or omitted in all cases . |

Table 2 Oxford Grades of Recommendation (GR).

| A | Consistent level 1 studies |

| B | Consistent level 2 or 3 studies or extrapolations from level 1 studies |

| C | Level 4 studies or extrapolations from level 2 or 3 studies |

| D | Level 5 evidence or troublingly inconsistent or inconclusive studies of any level |

Surgical Management of the Axilla in Primary Surgery

For many decades, complete dissection of the ipsilateral axillary lymph nodes (ALND – axillary lymph node dissection) in addition to breast surgery was considered the standard procedure to treat breast cancer. The aim of lymph node dissection was to determine the histological node status (pN stage) as one of the most important parameters determining the appropriate adjuvant therapeutic approach. Moreover, ensuring locoregional tumour control by removing the tumour burden was considered an important objective of the procedure. However, ALND is associated with high morbidity rates, which have a sustained negative impact on the long-term quality of life of affected women 2 .

In women who underwent primary surgery with no suspicion of axillary lymph node involvement, the use of ALND for staging has been replaced by sentinel lymph node excision (SLNE), which has a lower morbidity without compromising disease-free survival (DFS) or overall survival (OS) (NSABP B 32 3 ).

In women with a clinically normal lymph node status and limited SLN involvement, randomised studies showed that in certain cases it is possible to avoid ALND (ACOSOG Z0011, AMAROS) 4 , 5 . According to the updated recommendations of the AGO Breast Committee, the German S3 guideline (registry number 032 – 045OL), and the NCCN and ESMO guidelines, ALND can be avoided in selected patients with 1 – 2 affected lymph nodes 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 .

Surgical Management of the Axilla After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy

Sentinel lymphadenectomy and axillary dissection

When SLNE became the standard procedure, the aim was to combine the smallest possible surgical intervention with a precise diagnostic workup and the lowest side effect profile. Although the data on SLNE performed during primary surgery showed good results, for a long time the feasibility and safety of SLNE after neoadjuvant chemotherapy was considered to be controversial, particularly in cases with a positive axillary lymph node status before the start of therapy and conversion to clinically undetectable lymph node involvement after NACT (cN+ → ycN0 stage). Two large prospective multicentre studies reported a false-negative rate (FNR) of 12% and 14% respectively for this patient population, although the FNR decreased when increasing numbers of lymph nodes were removed 10 , 11 . This figure exceeds the generally accepted (but arbitrarily selected) cut-off value of 10%. However, the clinical impact of an FNR of > 10% on oncological endpoints (DFS, OS) is still unclear. For this reason, numerous national guidelines still recommend carrying out ALND in this patient population 5 , 6 .

Targeted axillary dissection (TAD)

In recent years, the question of how the FNR can be improved in patients with primary lymph node involvement (cN+) has been intensively discussed. In 2016, Caudle et al. published a report of a new procedure, TAD (targeted axillary dissection), in which both the SLN and one (or even several) lymph node(s) found to be affected prior to treatment are dissected after being marked with a clip before the start of therapy 12 . The initially biopsied and investigated lymph node is marked and is referred to as the target lymph node (TLN). When TAD (SLNE + TLNE) was used, the FNR was only 2.0% (95% CI: 0.05 – 10.7; p = 0.13), a figure that was significantly superior to a FNR of 10.1% with SLNE and a FNR of 4.2% when only the target lymph node was resected. These retrospectively evaluated data from a prospective database support the hypothesis that TAD could be a suitable procedure to improve the limited success rate of SLNE and additionally reduce the morbidity associated with ALND using a gentler form of surgery. A number of validation studies have been published in recent years which address the question of whether target lymph nodes need to be marked and which method should be used to mark them to ensure a reliably low FNR for TAD procedures. The studies did not just investigate the reproducibility of TAD, they also examined the clinical benefit of different marking techniques (carbon dye, clip, radioactive seed) 13 , 14 ( Table 4 )

Table 4 Trials evaluating different marking techniques.

| Study | Country | Marking technique | Case numbers (n) | Detection rate | FNR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SENTA 15 (NCT 03012307) | D | clip placement | 473 | 77.3% | 4.30% (95% CI: 0.5 – 14.8 ) |

| RISAS 16 , 17 (NCT 02800317) | NL | radioactive seed placement | 227 | 98.0% | 3.47% (95% CI:1.38 – 7.16) |

| TATTOO 18 (DRKS 00013169) | D, S | dye (carbon tattooing) | 110 | 93.6% | 9.10% |

In the report on the SENTA trial by Kümmel et al., the detection rate for the target lymph node was 77.3% and the FNR for TAD was 4.3% (95% CI: 0.5 – 14.8) 15 . In the RISAS trial, the reported FNR was 3.47% (95% CI:1.38 – 7.16) with a relatively small confidence interval, and the detection rate was 98% 16 , 17 . In contrast, Hartmann et al. reported a lower detection rate of 93.6% and a higher FNR of 9.1% for the TATTOO trial 18 .

None of the above-mentioned studies collected data on oncological endpoints such as disease-free survival and overall survival, quality of life, or effort and expense, so that it still remains unclear to what extent the different FNRs of the various methods affect the clinical outcome. Recommendations on TAD are therefore based on the reported FNRs and their perceived clinical relevance. The continuous improvement of local therapies and the use of individualised systemic therapy have led to continuously increasing rates of complete histopathological remission (pCR). In some groups, the rate may be as high as 70% 19 . Even in women with an initially positive lymph node status, the lymph node conversion rate may be as high as 50% 11 , 20 . This means that the percentage of patients who have a negative node status (ypN0) after NACT and are then overtreated by undergoing ALND is continually increasing. For this reason, limiting the extent of radical surgery required to determine node status is a matter of urgency, especially as the removal of clinically unremarkable axillary lymph nodes is increasingly viewed as being done for the purposes of staging alone.

According to verified data on the reduction of surgical radicality, the data on the long-term oncological outcome of minimally-invasive staging methods (SLNE, TAD) after conversion from cN1 to ycN0 has not yet been validated. For this reason, various surgical axillary procedures (ALND, TAD, SLNE, TLNE) are still carried out after NACT in Europe and worldwide (based on the assessment of the respective national professional societies and surgeons).

Recommendation of the AGO Breast Committee to reduce the rate of false negatives during the surgical staging of biopsy-confirmed axillary lymph node metastasis (pN+ CNB ) before NACT and ycN0

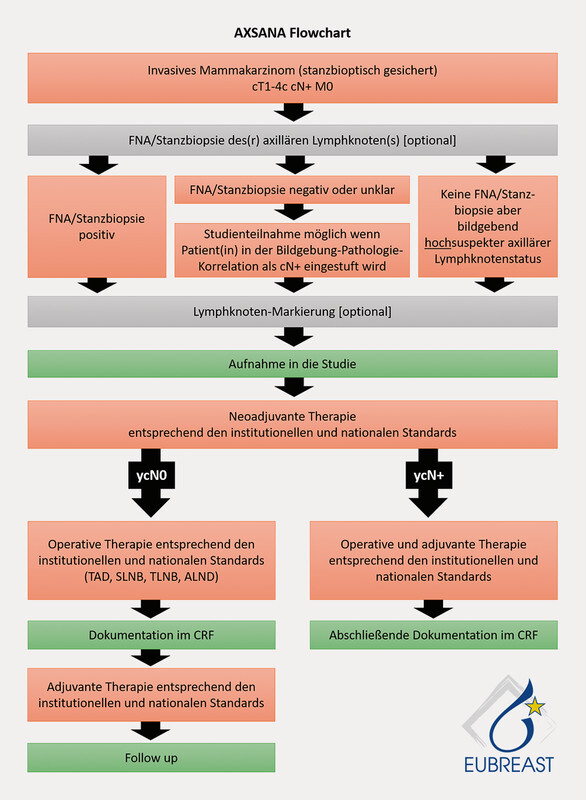

Using currently available data 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , the AGO has evaluated the following procedures to reduce false negative rates during the surgical staging of cases who are pN+ CNB before NACT and ycN0 after NACT with AGO + ( Fig. 1 ):

Fig. 1.

Algorithm of axillary surgical procedures before and after NACT. [rerif]

Targeted axillary dissection (TAD) (LoE 2b, GR: B, AGO +)

Dissection of > 2 SLNs (SLNE, no untargeted axillary sampling) (LoE 2a, GR: B, AGO +)

Immunohistochemical evaluation to detect isolated tumour cells or micro-metastasis (LoE 2b, GR: B, AGO +)

In principle, the AGO classified performing SLNE before neoadjuvant chemotherapy as a minus (LoE 2b, GR: B, AGO −), which means it is no longer recommended ( Table 5 ). The prime reason for this is that pCR assessment is no longer possible when SLNE is performed prior to NACT, and the patient is additionally subjected to an unnecessary surgical procedure.

Table 5 Surgical axillary interventions and NACT.

| Oxford | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LoE | GR | AGO | ||||||

| * Participation in AXSANA trial recommended; ** only radiotherapy for ypN1 (sn), ypN+ not recommended; ***recommendation grade is referred to staging for cN0 and cN+ ypN0. | ||||||||

| SLNE after NACT SLNE before NACT |

2b 2b |

B B |

++ – |

|||||

| cN status (before NACT) | pN status (before NACT) | cN status (after NACT) | Surgical axillary intervention (after NACT) | pN status (after NACT and surgery) | Surgical consequences of histological findings | |||

| cN0 | – | ycN0 | SLNE alone | ypN0 (sn) | – | 2b | B | ++*** |

| ypN0 (i+) ypN1 mic (sn) |

ALND | 2b | C | + (+/– with i+) | ||||

| none** | 5 | D | +/− | |||||

| ypN1 (sn) | ALND | 2b | C | ++ | ||||

| none** | 5 | D | +/− | |||||

| cN+ | pN+ CNB | ycN0 | SLNE alone* TAD (TLNE + SLNE)* ALND* |

ypN0 ypN0 ypN0 |

– | 2b 2b 2b |

B B B |

+/−*** +*** +*** |

| SLNE alone* TAD (TLNE + SLNE)* |

ypN+ incl. ypN0 (i+) | ALND | 2b | B | + (+/– with i+) | |||

| ALND | ypN+ | – | 2b | B | ++ | |||

| none | n. d. | none** | 5 | D | – | |||

| cN+ | pN+ CNB | ycN+ | ALND | ypN+ incl. ypN0 (i+) | – | 2b | B | ++ |

| None | n. d. | none** | 5 | D | – | |||

In contrast, carrying out axillary staging after systemic NACT therapy is recommended.

In this case, it is important to differentiate between two baseline situations ( Fig. 1 and Table 5 ):

Patients who are node-negative on clinical and ultrasound examination before NACT

Patients who are node-positive on clinical and ultrasound examination before NACT

Patients who are node-negative on clinical and ultrasound examination before NACT

In clinically node-negative patients, SLNE should be carried out after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. If the histomorphological findings for SLN are normal, i.e., ypN0(sn), then no further axillary procedures are necessary.

If macro-metastasis is present in the SLN after NACT, then axillary dissection is indicated and classified as ++ (LOE 2b, GR: C, AGO +).

If micro-metastasis is present in the SLN after NACT, then ALND is an option and is classified as + (LOE 2b, GR: C, AGO +), as additional LN metastases outside the SLN tend to be present in this setting in around 60% of cases 45 .

If isolated tumour cells are detected in SLN after NACT, the AGO classifies ALND as +/− (LOE 2b, GR: C, AGO +/−) and ALND may be considered in selected cases. Based on the currently available data, additional LN metastases may be present in around 17% of cases 45 .

Patients who are node-positive on clinical and ultrasound examination before NACT

If there is a primary suspicion of axillary lymph node involvement, a punch biopsy (pN+ CNB ) carried out prior to NACT for histopathological verification is recommended, with marking of the suspicious axillary lymph node (LOE 2b, GR: B, AGO +) to permit TAD after NACT.

If the axilla are normal on clinical and ultrasound examination after NACT (ycN0) , ALND and TAD are considered to be equivalent treatment options (LOE 2b, GR: B, AGO +), although TAD is a less invasive procedure with a low false-negative rate 12 . Lymph nodes which are found to be histomorphologically normal with TAD (ypN0) require no further surgical axillary intervention. Therapeutic ALND is recommended in cases with histologically verified lymph node involvement after TAD (ypN1), and the AGO classifies this as + (LOE 2b, GR: B, AGO +). ALND may be considered in selected cases with evidence of isolated tumour cells in LNs after TAD (ypN0[i+]); the AGO classifies this as +/− (LOE 2b, GR: B, AGO +/−).

ALND is indicated in cases with axillary involvement ( ycN+ ) detected on clinical or ultrasound examination (LOE 2b, GR: B, AGO ++). Further axillary procedures such as radiotherapy of the operated area are not indicated after complete ALND.

Because of its high false-negative rate of almost 17%, caution should be used with regard to SLNE alone after NACT in cases with conversion from cN+ → ycN0 45 . The AGO therefore classifies this option as +/− (LOE 2b, GR: B, AGO +/−).

A lot of questions with regard to currently used surgical procedures still remain unsolved. Because of the lack of data, recommendations for patient populations which are ycN0 after NACT [conversion from pN+ CNB (after punch biopsy) ] vary greatly across the world. The current ESMO guideline permits SLNE alone; if the findings are negative, no further lymph nodes need to be removed in selected cases. However, the ESMO guideline emphasises that the FNR of SLNE alone can be improved by marking the lymph nodes which were positive on the initial biopsy, followed by targeted dissection. The guideline recommendations in Germany also vary. After its last revision in 02/2020, the S3 guideline still recommends ALND as the preferred procedure for primary node-positive patients after NACT. In contrast, the AGO amended its recommendations in 2019 to the effect that it now classes TAD an equivalent procedure. However, ALND is still the only accepted standard procedure in a number of European countries, (Sweden, Norway, Finland). In other countries (Italy), SLNE is carried out as a routine procedure without additional marking of a TLN. The American NCCN guidelines recommend carrying out TAD as an optional procedure. A prospective comparison of the different techniques with regard to their feasibility, safety, morbidity and surgical cost is urgently required. Because of the complexity and costs involved and the very different guideline recommendations, carrying out a randomised comparison would not be useful to generate the necessary data which could resolve the many outstanding issues within a short space of time.

The therapeutic axillary approach in cases where the initial node status on clinical examination is normal but lymph node metastasis is detected following histopathological examination after NACT (cN0 → ycN0 → ypN1) is not yet been investigated much, meaning that ALND continues to be the standard recommended approach in most guidelines. Although the AMAROS trial proved that radiotherapy was equivalent to ALND in patients with a clinically occult nodal status who underwent primary surgery and the ACOSOG Z0011 trial has shown that axillary interventions can successfully be dispensed with in patients with positive SLNs, it is not clear whether these data can be transferred to cases with chemotherapy-resistant lymph node involvement (after NACT) 4 , 5 . The Alliance A011202 trial should provide important answers to this question 60 .

There is even less evidence available on the appropriate approach for small metastases (micro-metastasis, isolated tumour cells) after NACT (ypN1mi or ypN0i+). Although minimal lymph node involvement in patients who underwent primary surgery has no impact on adjuvant therapy planning, it is not clear whether ALND might be necessary for diagnostic purposes (because of the high rate of downstream non-SLNs which might lead to an upgrade of patientsʼ nodal status) or for therapeutic reasons (tumour cells resistant to systemic therapy) in cases with limited lymph node involvement after NACT.

Innovative methods have reduced the radicality of axillary surgery, but this reduced radicality should always be considered in the context of other therapeutic modalities. Even though studies have demonstrated the local efficacy of radiotherapy, with much of the data extrapolated from the adjuvant setting, carrying out the smallest possible axillary intervention and avoiding ALND should not be used as a justification for expanding radiotherapy measures, which have their own specific side effect profile.

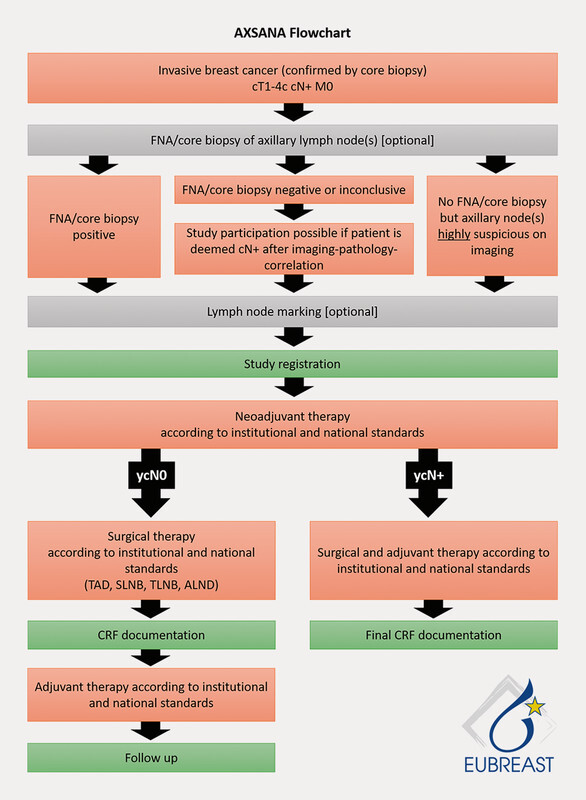

Prospective studies are urgently required to close the existing knowledge gaps. The AXSANA/EUBREAST-0 3 trial ( Fig. 2 ), which is supported by the AGO-B, is an international project which currently includes 20 participating countries. The aim is to investigate the impact of different axillary staging measures on invasive disease-free survival, axillary rate of recurrence and quality of life 13 . The trial will also be analysing different therapeutic procedures in patients with ypN1 status and studying the importance of micro-metastasis and isolated tumour cells after NACT.

Fig. 2.

AXSANA trial flowchart. [rerif]

Correction.

AGO Recommendations for the Surgical Therapy of the Axilla After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy: 2021 Update Michael Friedrich, Thorsten Kühn, Wolfgang Janni et al. Geburtsh Frauenheilk 2021; 81(10): 1112–1120. doi:10.1055/a-1499-8431

In the above article, the name of the co-author was given incorrectly. Correct is: Maggie Banys-Paluchowski.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt PD DR Banys-Paluchowski: Honoraria for lectures and advisory role from Lilly, Pfizer, Roche, Amgen, Eisai, Astra Zeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Novartis, GSK and study support from Endomag, Merit Medical and Mammotome. Prof. Dr. V. Müller: VM received speaker honoraria from Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, GSK, Pfizer, MSD, Novartis, Roche, Teva, Seagen and consultancy honoraria from Genomic Health, Hexal, Roche, Pierre Fabre, Amgen, ClinSol, Novartis, MSD, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Lilly, Seagen. Institutional research support from Novartis, Roche, Seagen, Genentech. Travel grants: Roche, Pfizer, Daiichi Sankyo./ Vortragshonorare: Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Pfizer, MSD, Novartis, Roche, Teva, Seattle Genetics, GSK, Seagen. Beratertätigkeit: Genomic Health, Hexal, Roche, Pierre Fabre, Amgen, ClinSol, Novartis, MSD, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Lilly, GSK, Tesaro, Seagen und Nektar. Forschungsuntersützung an den Arbeitgeber: Novartis, Roche, Seattle Genetics, Genentech. Reisekosten: Roche, Pfizer, Daiichi Sankyo.

References/Literatur

- 1.Ditsch N, Kolberg-Liedtke C, Friedrich M. AGO Recommendations for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients with Early Breast Cancer: Update 2021. Breast Care (Basel) 2021;16:214–227. doi: 10.1159/000516419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kühn T, Klauss W, Darsow M. Long-term morbidity following axillary dissection in breast cancer patients – clinical assessment, significance for life quality and the impact of demographic, oncologic and therapeutic factors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000;64:275–286. doi: 10.1023/a:1026564723698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krag D N, Anderson S J, Julian T B. Sentinel-lymph-node resection compared with conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in clinically node-negative patients with breast cancer: overall survival findings from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:927–933. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70207-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giuliano A E, Ballman K V, McCall L. Effect of Axillary Dissection vs. No Axillary Dissection on 10-Year Overall Survival Among Women With Invasive Breast Cancer and Sentinel Node Metastasis: The ACOSOG Z0011 (Alliance) Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;318:918–926. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donker M, van Tienhoven G, Straver M E. Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive sentinel node in breast cancer (EORTC 10981–22023 AMAROS): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1303–1310. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70460-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ditsch N, Untch M, Kolberg-Liedtke C. AGO Recommendations for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients with Locally Advanced and Metastatic Breast Cancer: Update 2020. Breast Care (Basel) 2020;15:294–309. doi: 10.1159/000508736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF) S3-Leitlinie Früherkennung, Diagnose, Therapie und Nachsorge des Mammakarzinoms, Version 4.3, 2020 AWMF Registernummer: 032–045OLOnline (Stand: 04.04.2021):http://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/mammakarzinom/

- 8.NCCN National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) Breast Cancer, Version 3.2021 – March 29, 2021Online (Stand: 04.04.2021):https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1419

- 9.Cardoso F, Kyriakides S, Ohno S. Early breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:1194–1220. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boughey J, Suman V, Mittendorf E. Sentinel lymph node surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-positive breast cancer: the ACOSOG Z1071 (Alliance) clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:1455–1461. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuehn T, Bauerfeind I, Fehm T. Sentinel-node biopsy in patients with breast cancer before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (SENTINA): a prospective, multicenter cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:609–618. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70166-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caudle A S, Wang W T, Krishnamurthy S. Improved Axillary Evaluation after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Patients with Node-Positive Breast Cancer using Selective Evaluation of Clipped Nodes: Implementation of Targeted Axillary Dissection. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1072–1078. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banys-Paluchowski M, Gasparri M L, Boniface J. Surgical Management of the Axilla in Clinically Node-Positive Breast Cancer Patients Converting to Clinical Node Negativity through Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy: Current Status, Knowledge Gaps, and Rationale for the EUBREAST-03. Cancers. 2021;13:1565. doi: 10.3390/cancers13071565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banys-Paluchowski M, Gruber I V, Hartkopf A. Axillary ultrasound for prediction of response to neoadjuvant therapy in the context of surgical strategies to axillary dissection in primary breast cancer: a systematic review of the current literature. Arch Gyn Obstet. 2020;301:341–353. doi: 10.1007/s00404-019-05428-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kümmel S, Heil J, Rueland A. Prospective, Multicenter Registry Study to Evaluate the Clinical Feasibility of Targeted Axillary Dissection (TAD) in Node-Positive Breast Cancer Patients. Ann Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Nijnatten T JA, Simons J M, Smidt M L. A Novel Less-invasive Approach for Axillary Staging After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Patients With Axillary Node-positive Breast Cancer by Combining Radioactive Iodine Seed Localization in the Axilla With the Sentinel Node Procedure (RISAS): A Dutch Prospective Multicenter Validation Study. Clin Breast Cancer. 2017;17:399–402. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simons J, Nijnatten T JV, Koppert L B. Radioactive Iodine Seed placement in the Axilla with Sentinel lymph node biopsy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: Results of the prospective multicenter RISAS trial. Gen Sess Abstr. 2021;81:GS1-10. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartmann S, Kühn T, de Boniface J. Carbon tattooing for targeted lymph node biopsy after primary systemic therapy in breast cancer: prospective multicentre TATTOO trial. Br J Surg. 2021 doi: 10.1093/bjs/znaa083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Untch M, Jackisch C, Schneeweiss A. NAB – Paclitaxel Improves Disease Free Survival in Early Breast Cancer: GBG 69 – GeparSepto. J Clin Oncol. 2019 doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.01842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boughey J, McCall L, Ballman K. Tumor biology correlates with rates of breast-conserving surgery and pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: findings from ACOSOG Z1071 (Alliance) Prospective Multicenter Clinical Trial. Ann Surg. 2014;260:608–614. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong S M, Weiss A, Mittendorf E A. Surgical Management of the Axilla in Clinically Node-Positive Patients Receiving Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy: A National Cancer Database Analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019 doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartmann S, Reimer T, Gerber B. Wire localization of clip-marked axillary lymph nodes in breast cancer patients treated with primary systemic treatment. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;34:1072–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siso C, de Torres J, Esgueva-Colmenarejo A. Intraoperative Ultrasound-Guided Excision of Axillary Clip in Patients with Node-Positive Breast Cancer Treated with Neoadjuvant Therapy (ILINA Trial): A New Tool to Guide the Excision of the Clipped Node After Neoadjuvant Treatment. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:784–791. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-6270-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanna T P, King W D, Thibodeau S. Mortality due to cancer treatment delay: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;371:m4087. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cone E B, Marchese M, Paciotti M. Assessment of Time-to-Treatment Initiation and Survival in a Cohort of Patients With Common Cancers. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2030072. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.30072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reimer T, Gerber B. Quality-of-life considerations in the treatment of early-stage breast cancer in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2010;27:791–800. doi: 10.2165/11584700-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tuttle T M, Shamliyan T, Virnig B A. The impact of sentinel lymph node biopsy and magnetic resonance imaging on important outcomes among patients with ductal carcinoma in situ. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;2010:117–120. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerber B, Heintze K, Stubert J. Axillary lymph node dissection in early-stage invasive breast cancer: is it still standard today? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;128:613–624. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1532-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DʼAngelo-Donovan D D, Dickson-Witmer D, Petrelli N J. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer: A history and current clinical recommendations. Surg Oncol. 2012;21:196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galimberti V, Cole B F, Zurrida S. International Breast Cancer Study Group Trial 23-01 investigators. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in patients with sentinel-node micrometastases (IBCSG 23-01): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:297–305. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70035-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giuliano A E, Ballman K V, McCall L. Effect of Axillary Dissection vs. No Axillary Dissection on 10-Year Overall Survival Among Women With Invasive Breast Cancer and Sentinel Node Metastasis: The ACOSOG Z0011 (Alliance) Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;318:918–926. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu J F, Chen H L, Yang J. Feasibility and accuracy of sentinel lymph node biopsy in clinically node-positive breast cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee H D, Ahn S G, Lee S A. Prospective Evaluation of the Feasibility of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Breast Cancer Patients with Negative Axillary Conversion after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Cancer Res Treat. 2014 doi: 10.4143/crt.2013.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boileau J F, Poirier B, Basik M. Sentinel Node Biopsy After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Biopsy-Proven Node-Positive Breast Cancer: The SN FNAC Study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:258–264. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.7827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boughey J C, Ballman K V, Le-Petross H T. Identification and Resection of Clipped Node Decreases the False-negative Rate of Sentinel Lymph Node Surgery in Patients Presenting With Node-positive Breast Cancer (T0–T4, N1–N2) Who Receive Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy: Results From ACOSOG Z1071 (Alliance) Ann Surg. 2016;263:802–807. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryu J M, Lee S K, Kim J Y. Predictive Factors for Nonsentinel Lymph Node Metastasis in Patients With Positive Sentinel Lymph Nodes After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy: Nomogram for Predicting Nonsentinel Lymph Node Metastasis. Clin Breast Cancer. 2017;17:550–555. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2017.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galimberti V, Ribeiro Fontana S K, Maisonneuve P. Sentinel node biopsy after neoadjuvant treatment in breast cancer: five-year follow-up of patients with clinically node-negative or node-positive disease before treatment. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martelli G, Miceli R, Folli S. Sentinel node biopsy after primary chemotherapy in cT2 N0/1 breast cancer patients: Long-term results of a retrospective study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43:2012–2020. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2017.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palmer J AV, Flippo-Morton T, Walsh K K. Application of ACOSOG Z1071: Effect of Results on Patient Care and Surgical Decision-Making. Clin Breast Cancer. 2018;18:270–275. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fernandez-Gonzalez S, Falo C, Pla M J. The Shift From Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy Performed Either Before or After Neoadjuvant Systemic Therapy in the Clinical Negative Nodes of Breast Cancer Patients. Results, and the Advantages and Disadvantages of Both Procedures. Clin Breast Cancer. 2018;18:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kahler-Ribeiro-Fontana S, Pagan E, Magnoni F. Long-term standard sentinel node biopsy after neoadjuvant treatment in breast cancer: a single institution ten-year follow-up. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47:804–812. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2020.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tee S R, Devane L A, Evoy D. Meta-analysis of sentinel lymph node biopsy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with initial biopsy-proven node-positive breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2018;105:1541–1552. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Balic M, Thomssen C, Würstlein R. St. Gallen/Vienna 2019: A Brief Summary of the Consensus Discussion on the Optimal Primary Breast Cancer Treatment. Breast Care (Basel) 2019;14:103–110. doi: 10.1159/000499931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Classe J M, Loaec C, Gimbergues P. Sentinel lymph node biopsy without axillary lymphadenectomy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy is accurate and safe for selected patients: the GANEA 2 study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;173:343–352. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-5004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moo T A, Edelweiss M, Hajiyeva S.Is Low-Volume Disease in the Sentinel Node After Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy an Indication for Axillary Dissection? Ann Surg Oncol 2018251488–1494.Erratum in: Ann Surg Oncol 2020; 27 (Suppl. 3): 966 Erratum in: Ann Surg Oncol 2020; 27 (Suppl. 3): 966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Allweis T M, Menes T, Rotbart N. Ultrasound guided tattooing of axillary lymph nodes in breast cancer patients prior to neoadjuvant therapy, and identification of tattooed nodes at the time of surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;46:1041–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2019.11.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Balasubramian R, Morgan C, Shaari E. Wire guided localisation for targeted axillary node dissection is accurate in axillary staging in node positive breast cancer following neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;46:1028–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2019.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coufal O, Zapletal O, Gabrielová L. Targeted axillary dissection and sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer patients after neoadjuvant chemotherapy – a retrospective study. Rozhl Chir Winter. 2018;97:551–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ditsch N, Rubio I T, Gasparri M L. Breast and axillary surgery in malignant breast disease: a review focused on literature of 2018 and 2019. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2020;32:91–99. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flores-Funes D, Aguilar-Jiménez J, Martínez-Gálvez M. Validation of the targeted axillary dissection technique in the axillary staging of breast cancer after neoadjuvant therapy: Preliminary results. Surg Oncol. 2019;30:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2019.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gandhi A, Coles C, Makris A. Axillary Surgery Following Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy – Multidisciplinary Guidance From the Association of Breast Surgery, Faculty of Clinical Oncology of the Royal College of Radiologists, UK Breast Cancer Group, National Coordinating Committee for Breast Pathology and British Society of Breast Radiology. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2019;31:664–668. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2019.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.García-Moreno J L, Benjumeda-Gonzalez A M, Amerigo-Góngora M. Targeted axillary dissection in breast cancer by marking lymph node metastasis with a magnetic seed before starting neoadjuvant treatment. J Surg Case Rep. 2019;2019:rjz344. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjz344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greenwood H I, Wong J M, Mukhtar R A. Feasibility of Magnetic Seeds for Preoperative Localization of Axillary Lymph Nodes in Breast Cancer Treatment. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2019;213:953–957. doi: 10.2214/AJR.19.21378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hellingman D, Donswijk M L, Winter-Warnars G AO. Feasibility of radioguided occult lesion localization of clip-marked lymph nodes for tailored axillary treatment in breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant systemic therapy. EJNMMI Res. 2019;9:94. doi: 10.1186/s13550-019-0560-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kanesalingam K, Sriram N, Heilat G. Targeted axillary dissection after neoadjuvant systemic therapy in patients with node-positive breast cancer. ANZ J Surg. 2020;90:332–338. doi: 10.1111/ans.15604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Natsiopoulos I, Intzes S, Liappis T. Axillary Lymph Node Tattooing and Targeted Axillary Dissection in Breast Cancer Patients Who Presented as cN+ Before Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and Became cN0 After Treatment. Clin Breast Cancer. 2019;19:208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2019.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Simons J M, van Nijnatten T JA, van der Pol C C. Diagnostic Accuracy of Different Surgical Procedures for Axillary Staging After Neoadjuvant Systemic Therapy in Node-positive Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2019;269:432–442. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simons J M, van Pelt M LMA, Marinelli A WKS. Excision of both pretreatment marked positive nodes and sentinel nodes improves axillary staging after neoadjuvant systemic therapy in breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2019;106:1632–1639. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee J, Jung J H, Kim W W. 5-year oncological outcomes of targeted axillary sampling in pT1-2N1 breast cancer. Asian J Surg. 2019;42:681–687. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.National Cancer Institute Comparison of axillary lymph node dissection with axillary radiation for patients with node-positive breast cancer reated with chemotherapyOnline (Stand: 09.05.2015):http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/search/view?cdrid=751211&version=HealthProfessional