Abstract

The 2020 WHO classification is focused on the distinction between HPV-associated and HPV-independent squamous cell carcinoma of the lower female genital organs. Differentiating according to HPV association does not replace the process of grading; however, the WHO classification does not recommend any specific grading system. VIN are also differentiated according to whether they are HPV(p16)-associated. HPV-independent adenocarcinoma (AC) of the cervix uteri has an unfavorable prognosis. Immunohistochemical p16 expression is considered to be a surrogate marker for HPV association. HPV-associated AC of the cervix uteri is determined using the prognostically relevant Silva pattern.

Key words: p16 immunohistochemistry, HPV, Silva pattern

Introduction

The WHO Classification of Female Genital Tumors is the fourth volume in the fifth edition of the WHO series on the classification of human tumors, and was fundamentally revised in 2020 due to new histomorphological data and, in particular, molecular pathology data. In comparison with the 2013 edition, the scope of the work has doubled in length. The WHO classification is now primarily constructed on the basis of new (molecular) pathology data. However, data of therapeutic and diagnostic relevance, insofar as they are available, are certainly also incorporated. The WHO Blue Books represent an important foundation for a globally uniform diagnostic standard. In Germany, the guidelines of the AWMF (Association of the Scientific Medical Societies) recommend using the current WHO classification for the pathological findings report. The obligation to use the diagnostic histopathological standards and terminology according to the current WHO classification is described in all of the guidelines relating to gynecological malignancies with the verb “should”, this being the highest level of recommendation. While the WHO classification sets out terminology and criteria for diagnosis, the TNM classification of malignant tumors as well as the FIGO classification (Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et dʼObstétrique) are used for staging, i.e., determining the extent and spread of the gynecological tumors.

The following article summarizes the significant changes of clinical relevance in the current WHO classification for tumors of the female genitals in a way that is relevant in practice.

Vulvar Tumors

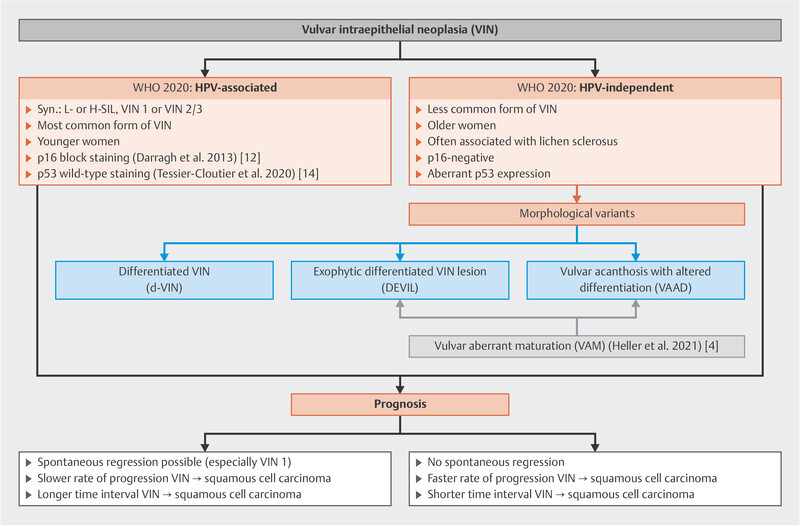

With reference to vulvar intraepithelial neoplasias (VIN), the distinction between HPV-associated and HPV-negative neoplasia has been retained. In terms of nomenclature, HPV-associated VIN corresponds to low (VIN 1) and high-grade SIL (VIN 2 and 3; Figs. 1 and 2 ).

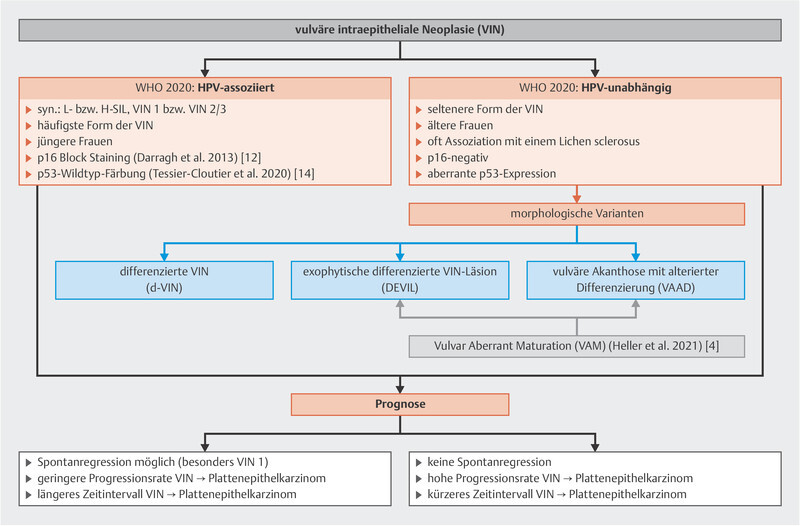

Fig. 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of the 2020 WHO classification of vulvar precancerous lesions 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 12 , 14 .

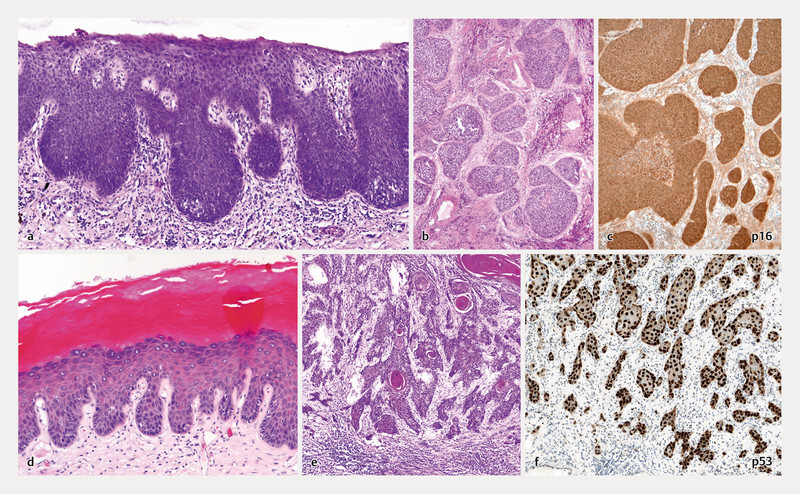

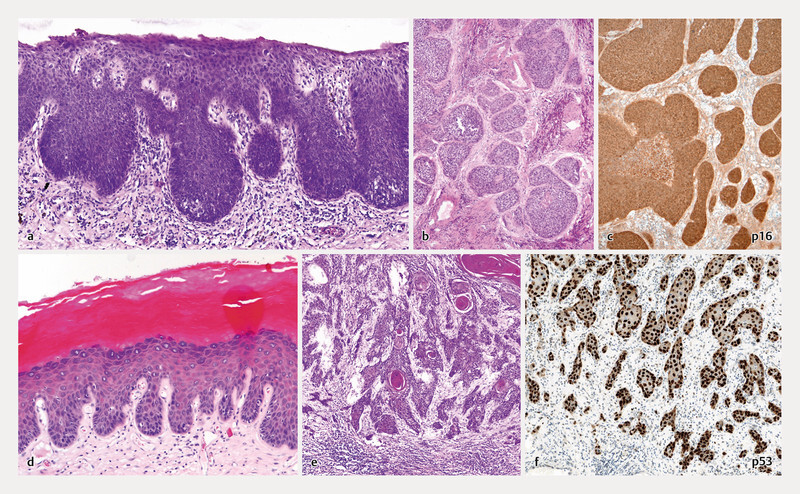

Fig. 2.

Precancerous lesions (VIN) and vulvar carcinoma. a HPV-associated VIN (usual VIN; u-VIN), b and c non-keratinizing, HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva with a plump pattern of invasion and p16 positivity (so-called block staining; see text), d HPV-independent VIN (d-VIN), e and f keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva with a netlike pattern of invasion and aberrant p53 expression (see text).

In cases of VIN where no HPV is detected, the term HPV-independent VIN has been introduced 1 , 2 ; Fig. 1 showing a variable morphology:

The differentiated VIN with its horizontal spread (d-VIN) is a precursor lesion that is allocated to a more aggressive,

the differentiated exophytic VIN lesion (DEVIL) to a less aggressive (keratinizing) squamous cell carcinoma and the

vulvar acanthosis with altered differentiation (VAAD) is allocated to verrucous carcinoma as a precursor/risk lesion 2 , 3 .

Within this context, it is important to note that different types of lesions may coincide with each other 1 , 2 , 4 . Due to morphological similarities or overlaps 3 , DEVIL and VAAD are also covered by the umbrella term of aberrant maturation of the vulvar squamous epithelium (vulvar aberrant maturation; VAM; 4 ) ( Fig. 1 ), a term that is not included in the WHO classification.

Despite the fact that this distinction as yet lacks diagnostic and therapeutic relevance 5 , 6 , the new WHO classification differentiates between HPV-associated and HPV-independent squamous cell carcinoma due to their different pathogenesis ( Figs. 1 and 2 ), and the WHO recommends supplying this information in the findings report. The ratio of HPV-independent to HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma is stated to be between 0.60 and 0.83 7 .

Irrespective of clinicopathological differences ( Table 1 ), the HE-morphology does not allow for reliable differentiation between HPV-associated and HPV-independent (p53-associated) squamous cell carcinoma 2 , 4 , as it has an error rate of 20 – 30% 8 , 9 . The third pathogenetic concept postulated by Nooij et al. 10 (see below; Table 1 ; 5 , 11 ) is not included in the new WHO classification as the current data are still insufficient.

Table 1 Pathogenetically based clinicopathological characteristics of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma 2 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 10 , 11 , 20 , 42 .

| HPV-associated | HPV-independent | Uncertain | |

|---|---|---|---|

| p16 + /p53 − | p16 − /p53 + | p16 − /p53 − | |

| Frequency | 40% | 50 – 60% | 20% |

| Age | 40 – 60 years of age | 50 – 70 years of age | 60 – 70 years of age |

| Precancerous lesion | VIN 2/3 (H-SIL) | HPV-independent VIN (d-VIN,? VAAD,? DEVIL) | ? (d-VIN-/VAAD-like?) |

| Etiopathogenesis | High-risk HPV infection | p53 alteration | ? (NOTCH-1/HRAS/ PIK3CA mutation?) |

| Biomarker expression | p16 positive (block staining) | p53-aberrant staining pattern | p16 negative/p53 wt |

| Histology (Heller et al. 2020) | Non-keratinizing (ca. 66%) | Keratinizing (80 – 90%) | Keratinizing/ non-keratinizing |

| Inguinal lymph node metastases | 30% | 40% | 30% |

| Radio(chemo)sensitivity | Usually sensitive | Less sensitive | Possibly less sensitive |

| Prognosis | Better | Poorer | Intermediate |

|

5.3% | 22.6% | 16.3% |

|

64% | 47% | 60% |

|

89% | 75% | 83% |

|

82% | 70% | 75% |

Immunohistochemistry showing strong nuclear and cytoplasmic p16 reactivity (so-called block staining; 12 ; Fig. 2 c ) points towards HPV association and is defined as a “reliable (although not perfect)” surrogate marker by the WHO (WHO 2020, 4 , 13 ). Analysis using p53 immunohistochemistry may help to more accurately diagnose VIN and vulvar squamous cell carcinoma 4 ( Fig. 2 f ), as staining patterns have been defined that correlate well with underlying mutations 7 , 14 .

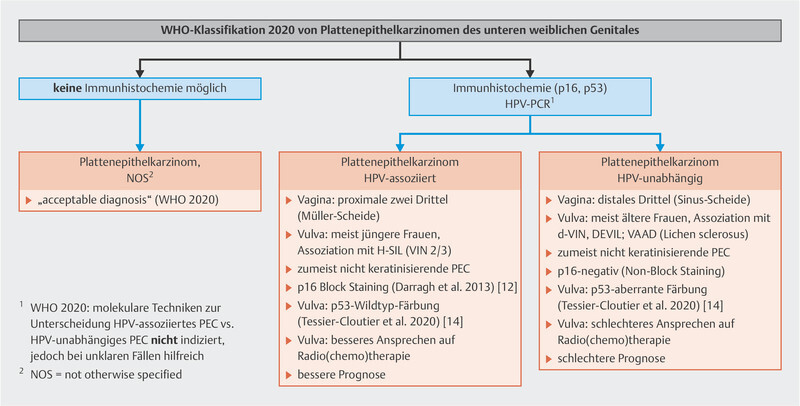

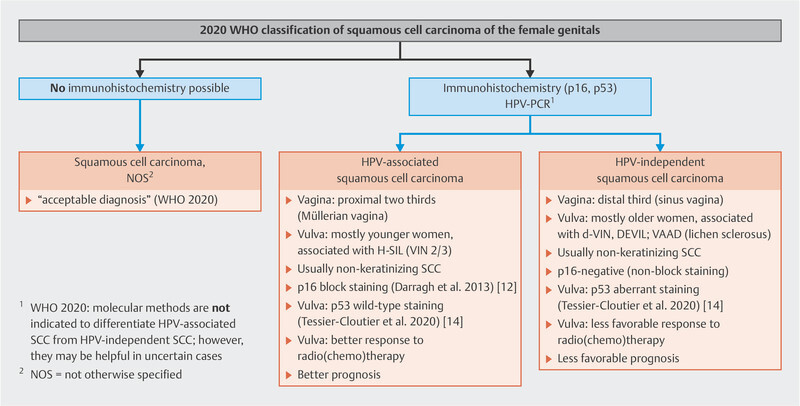

Should it not be possible to classify the tumor based on p16 immunohistochemistry (and/or molecular HPV detection) or the presence of p53, the WHO deems the description squamous cell carcinoma NOS to be “acceptable” ( Fig. 5 ). The WHO explicitly points out that molecular analyses (i.e., HPV detection in situ) are not indicated for diagnostic evaluation.

Fig. 5.

Clinicopathological characteristics of the 2020 WHO classification of squamous cell carcinoma of the female genitals 1 , 5 , 6 , 8 , 9 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 17 , 18 , 20 , 24 , 27 , 44 .

Patients with p16-positive squamous cell carcinoma who have received radio(chemo)therapy show a higher response rate that is statistically significant compared with patients with p53-associated carcinoma 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 .

In these patient groups with very different therapeutic approaches, it has now been acknowledged that p16-positive carcinomas have a better prognosis compared with those that are p53-positive 5 , 6 , 11 , 19 . The study by McAlpine et al. 20 points out that patients with p53-positive tumors benefit from a more radical surgical approach. Initial molecular studies show that vulvar carcinoma with a p53 mutation and an additional PIK3CA comutation have a particularly unfavorable prognosis 7 . There also clearly exists a third pathogenetic group of p16 − /p53 − tumors, which ranks prognostically between the p16-positive and the p53-aberrant vulvar carcinoma 5 , 11 ( Table 1 ). Whether or not the prognostically favorable low-grade squamous cell carcinoma with verrucous morphology represents one morphological end of the p16 − /p53 − tumor spectrum 7 is still unclear.

The WHO classification does not include grading specifications. In the view of the authors, HPV association (i.e., p16 block positivity; 12 ) does not (yet) replace the grading process. Should a grading be necessary for documentation or for the DRG system, this can be done based on the extent of keratinization, analogous to the approach used thus far.

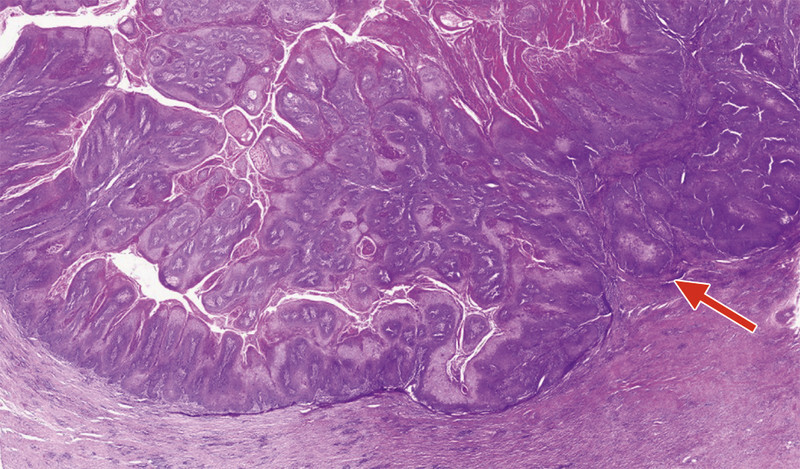

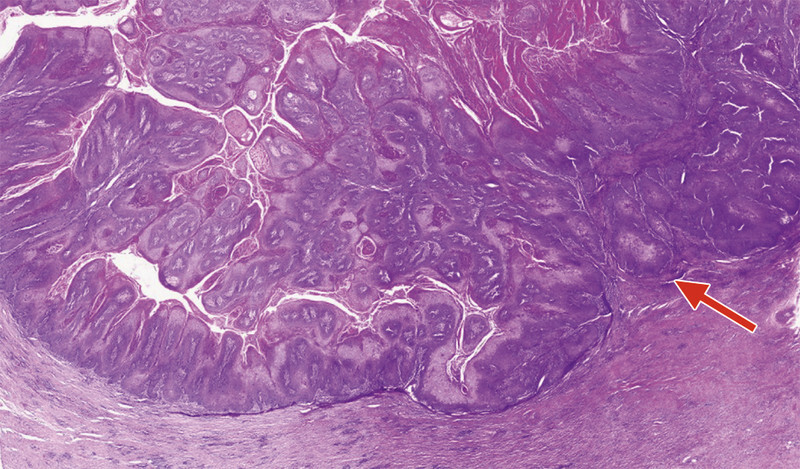

It is unclear why verrucous carcinoma ( Fig. 3 ) is no longer listed in the WHO classification; it is, however, mentioned in more recent reviews 2 , 4 . Molecular analyses also regard this tumor type separately 7 . Based on verified HRAS and PIK3CA mutations, VAAD is thought to be a precursor lesion of verrucous carcinoma 3 .

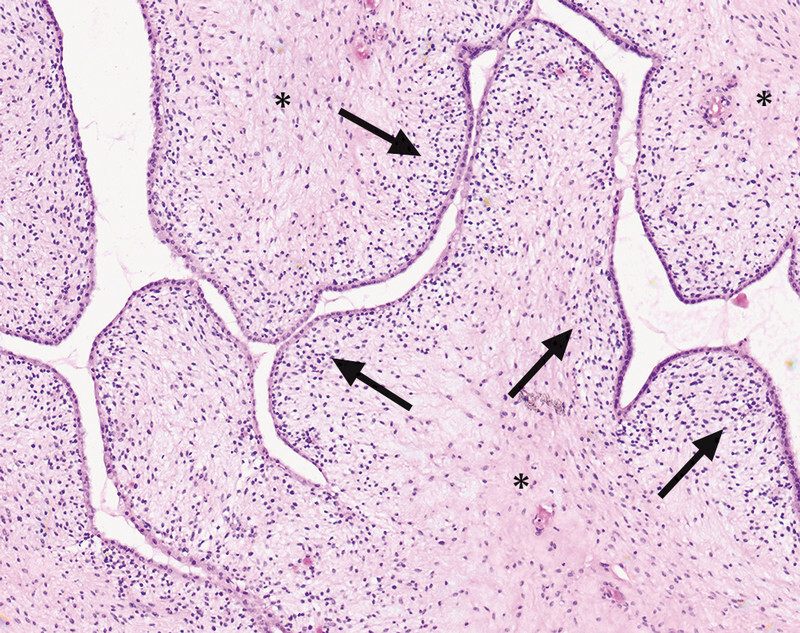

Fig. 3.

Verrucous carcinoma of the vulva: exophytic verrucous growth of well-differentiated squamous cell epithelium with superficial parakeratosis and a sharp demarcation, with only focal infiltration (arrow), from the subjacent stroma.

The WHO classification explicitly mentions the possibility of immunohistochemical HER2 detection for Morbus Paget . A meta-analysis of 713 patients demonstrated that HER2 expression was present in 30% of cases, and steroid hormone receptor positivity for ER, PR and AR was present in 13%, 8% and 40% respectively 21 . These may serve as a basis for possible therapeutic targets.

Vaginal Tumors

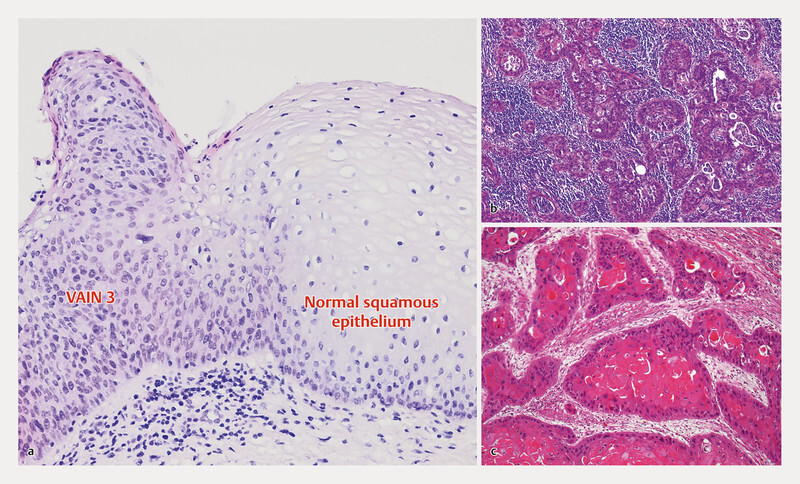

When it comes to the vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VaIN; Fig. 4 a ) and adenocarcinoma , there have been no changes.

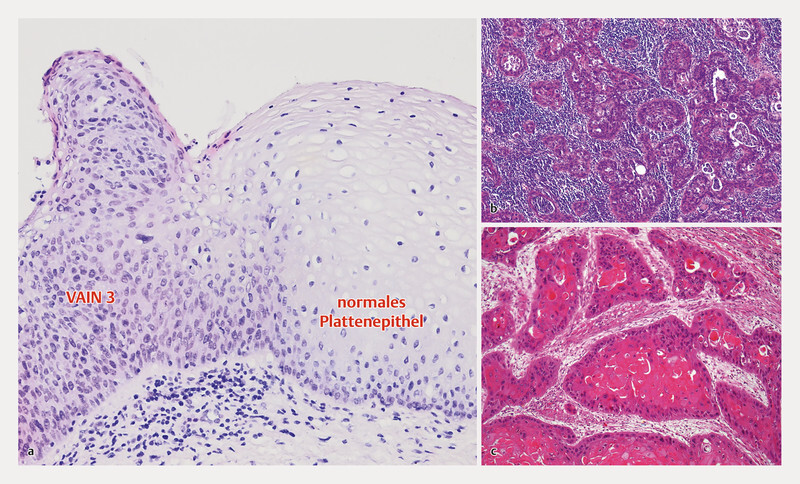

Fig. 4.

Precancerous lesions and carcinoma of the vagina. a HPV-associated precancerous lesion of the vagina (VAIN 3), b keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina with slight peritumoral desmoplasia and absence of peritumoral inflammation, c non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina with a high degree of peritumoral inflammation.

For squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina, the detection of HPV is currently of no therapeutic relevance 22 . Nevertheless, the WHO recommends making this distinction for these tumor types as well ( Fig. 5 ).

In general, the majority of vaginal squamous cell carcinomas are HPV-associated, especially those with a non-keratinizing morphology ( Fig. 4 b ) and tumor location in the upper or intermediate third (so-called Müllerian vagina). Distal squamous cell carcinomas are known as introitus carcinoma and stem from the urogenital sinus (so-called sinus vagina; 23 , 24 ). Lacking HPV association, these are often keratinizing squamous cell carcinomas ( Fig. 4 c ).

For vaginal carcinomas too, the WHO points out that molecular analyses (i.e., HPV detection in situ) are not indicated for the diagnostic evaluation.

The WHO classification does not include grading specifications. In the view of the authors, HPV association (i.e., p16 block positivity; 12 ) does not (yet) replace the grading process. Should a grading be necessary for documentation or for the DRG system, this can be done based on the extent of keratinization, analogous to the approach used thus far.

Tumors of the Cervix Uteri

For squamous cell cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), there have been no changes.

When it comes to adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) , a distinction is made between various HPV-associated variants and the non-HPV-associated gastric AIS (g-AIS). SMILE (stratified mucin-producing intraepithelial lesion) as a subtype of AIS is no longer listed as an independent entity.

Epithelial precancerous lesions and carcinoma of the cervix uteri are predominantly HPV-associated 25 .

To ensure a uniform nomenclature, the WHO has classified these squamous cell carcinomas in a manner analogous to the vulvar and vaginal carcinomas ( Fig. 5 ).

For the very rare HPV-negative squamous cell carcinoma 26 , 27 there is no known precancerous lesion.

Similarly for squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix uteri , the HE-morphology alone does not allow differentiation between the two forms; for this reason the WHO recommends performing p16 immunohistochemistry but also accepts the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma NOS ( Fig. 5 ), as there are no existing therapeutic or prognostic differences. With regard to grading , the WHO classification states that there is no established grading system. In the view of the authors, HPV association (i.e., p16 block positivity; 12 ) does not (yet) replace the grading process. Should a grading be necessary for documentation or for the DRG system, this can be done based on the extent of keratinization, analogous to the approach used thus far.

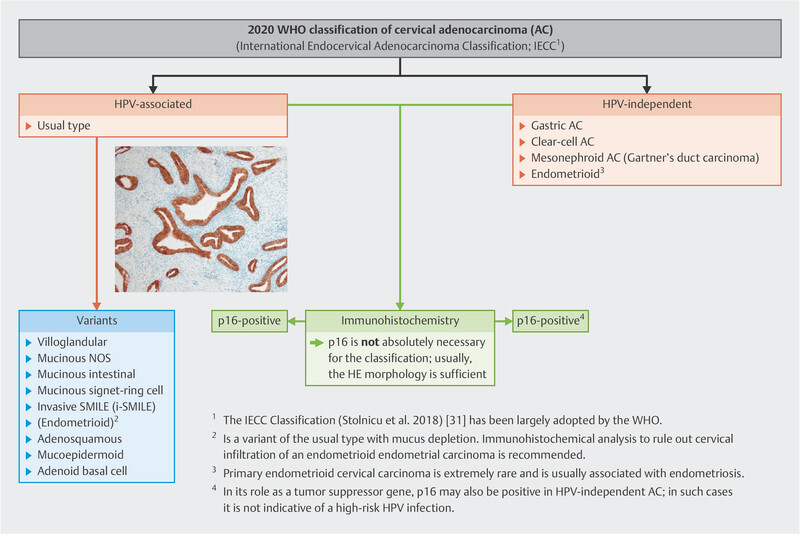

For adenocarcinoma (AC) of the cervix uteri , a similar distinction is made with regard to the high-risk HPV association. HPV-negative AC has a significantly less favorable prognosis 28 , 29 , 30 .

Therefore, the previous diagnostic category of AC-NOS no longer exists in the new edition of the WHO classification.

The same applies for (primary) serous AC of the cervix uteri , which are almost exclusively endometrial or isthmic endometrial carcinomas with cervical involvement 29 , 31 .

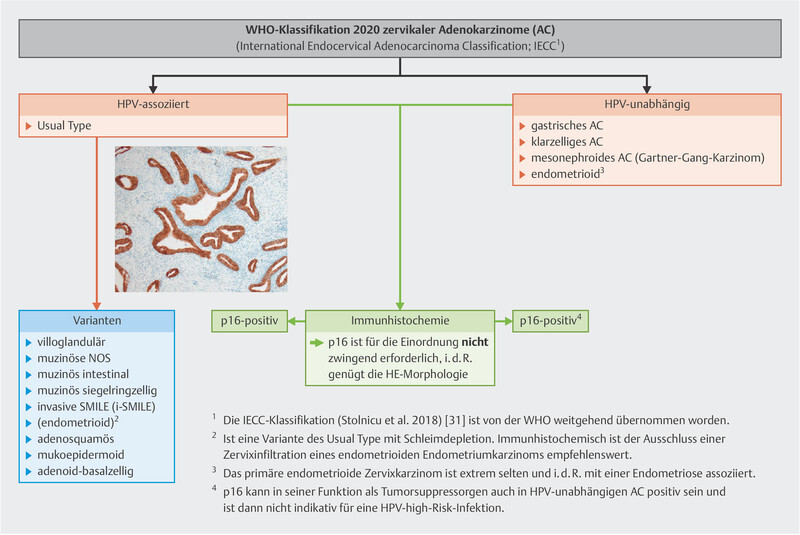

The WHO classification has adopted the “International Endocervical Adenocarcinoma Classification” (IECC; 28 , 29 ) ( Fig. 6 ), which was also included in the S3-Guideline for cervical carcinoma reviewed in 2021 32 .

Fig. 6.

Classification of adenocarcinoma of the cervix uteri in accordance with the 2020 WHO classification 1 , 28 , 29 , 31 , 32 , 37 . Small image: strong p16 positivity of a usual-type AC.

An HPV analysis is not necessary for the diagnosis 1 . If “block-type” reactivity is detected 1 ( Fig. 6 ), p16 is a reliable surrogate marker for HPV association. In very rare cases, p16 hypermethylation may lead to a (false) negative immunohistochemistry 33 , an error that is estimated to occur for CIN 3 in approx. 5% of cases 4 , 34 . The choice of a suitable p16 clone is also very important for the reliable detection of p16 35 . The p16 reactivity in old paraffin blocks or insufficiently fixed tissues is deemed unreliable 31 , 36 . It is also important to note that HPV-independent AC (i.e., gastric AC) may also demonstrate p16 positivity 37 . The p16 immunohistochemistry must be interpreted within the context of the HE morphology.

The so-called Silva pattern , a prognostically relevant classification of (HPV-associated) AC based on architectural criteria, has been newly adopted into WHO classification ( Table 2 ).

Table 2 Frequency and prognostic relevance of the Silva pattern for HPV-associated adenocarcinoma of the cervix uteri 43 .

| Frequency | Pelvic lymph node metastasis | FIGO Stage I | FIGO Stage II – IV | Recurrence rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pattern A

|

20.7% | 0% | 100% | 0% | 0% |

Pattern B

|

25.6% | 4.4% | 100% | 0% | 1.1% |

Pattern C

|

53.7% | 23.8% | 83% | 17% | 23.7% |

It distinguishes between the prognostically more favorable pattern A carcinoma with non-destructive invasion and the pattern B and C carcinoma with destructive invasion. Distinguishing between pattern A-AC and AIS based on HE morphology can be difficult (k = 0.23; 38 ).

In almost all cases, endometrioid AC of the endocervix represents a mucin-depleted variant of HPV-associated AC. Immunohistochemistry should be used to distinguish between benign lesions and endometrioid endometrial carcinoma with cervical infiltration.

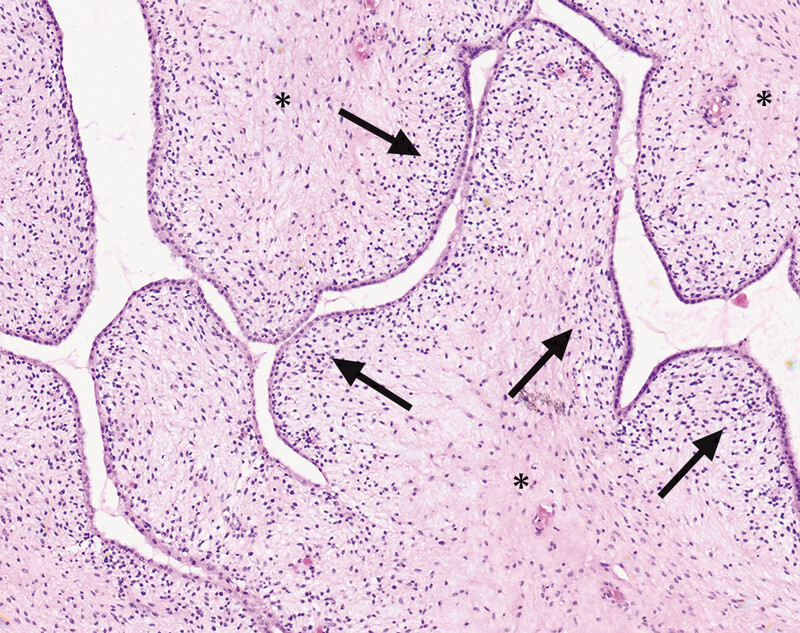

Epithelial-mesenchymal Tumors

Adenofibromas of the cervix uteri that were previously listed in the WHO classification are now considered in fact to be benign endometrial or cervical polyps with an unusual morphology 39 , 40 , or alternatively adenosarcoma with “low-grade stromal morphology” ( Fig. 7 ). Immunohistochemical analyses are helpful for differential diagnosis in these cases 41 .

Fig. 7.

Adenosarcoma of the Uterus: foliaceous tumor growth with very cell-poor stroma (*) showing discrete accentuation of the cell density underneath the superficial epithelium (arrows) with a bland cytology.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest./Die Autorinnen/Autoren geben an, dass kein Interessenkonflikt besteht.

References/Literatur

- 1.Lokuhetty D, White V A, Watanabe R. Lyon: Internal Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2020. Female genital Tumours. 5th ed. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh N, Gilks C B. Vulval squamous cell carcinoma and its precursors. Histopathology. 2020;76:128–138. doi: 10.1111/his.13989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watkins J C. Human Papillomavirus-Independent Squamous Lesions of the Vulva. Surg Pathol Clin. 2019;12:249–261. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heller D S, Day T, Allbritton J I. Diagnostic Criteria for Differentiated Vulvar Intraepithelial Neoplasia and Vulvar Aberrant Maturation. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2021;25:57–70. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barlow E L, Lambie N, Donoghoe M W. The Clinical Relevance of p16 and p53 Status in Patients with Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Vulva. J Oncol. 2020;2020:3.739075E6. doi: 10.1155/2020/3739075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sand F L, Nielsen D MB, Frederiksen M H. The prognostic value of p16 and p53 expression for survival after vulvar cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;152:208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tessier-Cloutier B, Pors J, Thompson E. Molecular characterization of invasive and in situ squamous neoplasia of the vulva and implications for morphologic diagnosis and outcome. Mod Pathol. 2021;34:508–518. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-00651-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng A S, Karnezis A N, Jordan S. p16 Immunostaining Allows for Accurate Subclassification of Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma Into HPV-Associated and HPV-Independent Cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2016;35:385–393. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santos M, Landolfi S, Olivella A. p16 overexpression identifies HPV-positive vulvar squamous cell carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1347–1356. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213251.82940.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nooij L S, Ter Haar N T, Ruano D. Genomic Characterization of Vulvar (Pre)cancers Identifies Distinct Molecular Subtypes with Prognostic Significance. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:6781–6789. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woelber L, Prieske K, Eulenburg C. p53 and p16 expression profiles in vulvar cancer: a translational analysis by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynäkologische Onkologie Chemo and Radiotherapy in Epithelial Vulvar Cancer study group. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:5950–5.95E13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.12.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darragh T M, Colgan T J, Thomas Cox J. The Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology Standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2013;32:76–115. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e31826916c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dasgupta S, Ewing-Graham P C, Swagemakers S MA. Precursor lesions of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma – histology and biomarkers: A systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2020;147:102866. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.102866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tessier-Cloutier B, Kortekaas K E, Thompson E. Major p53 immunohistochemical patterns in in situ and invasive squamous cell carcinomas of the vulva and correlation with TP53 mutation status. Mod Pathol. 2020;33:1595–1605. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-0524-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yap M L, Allo G, Cuartero J. Prognostic Significance of Human Papilloma Virus and p16 Expression in Patients with Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma who Received Radiotherapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2018;30:254–261. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee L J, Howitt B, Catalano P. Prognostic importance of human papillomavirus (HPV) and p16 positivity in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva treated with radiotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;142:293–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Proctor L, Hoang L, Moore J. Association of human papilloma virus status and response to radiotherapy in vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020;30:100–106. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2019-000793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allo G, Yap M L, Cuartero J. HPV-independent Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma is Associated With Significantly Worse Prognosis Compared With HPV-associated Tumors. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2020;39:391–399. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rasmussen C L, Sand F L, Hoffmann Frederiksen M. Does HPV status influence survival after vulvar cancer? Int J Cancer. 2018;142:1158–1165. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McAlpine J N, Leung S CY, Cheng A. Human papillomavirus (HPV)-independent vulvar squamous cell carcinoma has a worse prognosis than HPV-associated disease: a retrospective cohort study. Histopathology. 2017;71:238–246. doi: 10.1111/his.13205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Angelico G, Santoro A, Inzani F. Hormonal Environment and HER2 Status in Extra-Mammary Pagetʼs Disease (eMPD): A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis with Clinical Considerations. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020;10:1040. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10121040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hellman K, Lindquist D, Ranhem C. Human papillomavirus, p16(INK4A), and Ki-67 in relation to clinicopathological variables and survival in primary carcinoma of the vagina. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:1561–1570. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Höckel M, Horn L-C, Illig R. Ontogenetic anatomy of the distal vagina: relevance for local tumor spread and implications for cancer surgery. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122:313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horn L-C, Höhn A K, Hampl M. S2k-Leitlinie Diagnostik und Therapie des Vaginalkarzinoms und seiner Vorstufen – Anforderungen an die Pathologie. Der Pathologe. 2021;42:116–124. doi: 10.1007/s00292-020-00876-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.RIS HPV TT, VVAP and Head and Neck study groups . de Sanjosé S, Serrano B, Tous S. Burden of Human Papillomavirus (HPV)-Related Cancers Attributable to HPVs 6/11/16/18/31/33/45/52 and 58. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019;2:pky045. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pky045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li N, Franceschi S, Howell-Jones R. Human papillomavirus type distribution in 30,848 invasive cervical cancers worldwide: Variation by geographical region, histological type and year of publication. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:927–935. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casey S, Harley I, Jamison J. A rare case of HPV-negative cervical squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2015;34:208–212. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hodgson A, Olkhov-Mitsel E, Howitt B E. International Endocervical Adenocarcinoma Criteria and Classification (IECC): correlation with adverse clinicopathological features and patient outcome. J Clin Pathol. 2019;72:347–353. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2018-205632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stolnicu S, Hoang L, Chiu D. Clinical Outcomes of HPV-associated and Unassociated Endocervical Adenocarcinomas Categorized by the International Endocervical Adenocarcinoma Criteria and Classification (IECC) Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43:466–474. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nicolás I, Saco A, Barnadas E. Prognostic implications of genotyping and p16 immunostaining in HPV-positive tumors of the uterine cervix. Mod Pathol. 2020;33:128–137. doi: 10.1038/s41379-019-0360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stolnicu S, Barsan I, Hoang L. International Endocervical Adenocarcinoma Criteria and Classification (IECC): A New Pathogenetic Classification for Invasive Adenocarcinomas of the Endocervix. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:214–226. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.AWMF S3-Leitlinie zur Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge der Patientin mit Zervixkarzinom, 2021Accessed January 26, 2021 at:https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/032-033OL.html

- 33.Nuovo G J, Plaia T W, Belinsky S A. In situ detection of the hypermethylation-induced inactivation of the p16 gene as an early event in oncogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12754–12759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shain A F, Kwok S, Folkins A K. Utility of p16 Immunohistochemistry in Evaluating Negative Cervical Biopsies Following High-risk Pap Test Results. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:69–75. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shain A F, Wilbur D C, Stoler M H. Test Characteristics of Specific p16 Clones in the Detection of High-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions (HSIL) Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2018;37:82–87. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nuovo A J, Garofalo M, Mikhail A. The effect of aging of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues on the in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry signals in cervical lesions. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2013;22:164–173. doi: 10.1097/PDM.0b013e3182823701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carleton C, Hoang L, Sah S. A Detailed Immunohistochemical Analysis of a Large Series of Cervical and Vaginal Gastric-type Adenocarcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:636–644. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parra-Herran C, Taljaard M, Djordjevic B. Pattern-based classification of invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma, depth of invasion measurement and distinction from adenocarcinoma in situ: interobserver variation among gynecologic pathologists. Mod Pathol. 2016;29:879–892. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ip P P. Benign endometrial proliferations mimicking malignancies: a review of problematic entities in small biopsy specimens. Virchows Arch. 2018;472:907–917. doi: 10.1007/s00428-018-2314-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Howitt B E, Quade B J, Nucci M R. Uterine polyps with features overlapping with those of Müllerian adenosarcoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 29 cases emphasizing their likely benign nature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:116–126. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCluggage W G. A practical approach to the diagnosis of mixed epithelial and mesenchymal tumours of the uterus. Mod Pathol. 2016;29 01:S78–S91. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2015.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knopp S, Bjørge T, Nesland J M. p16INK4a and p21Waf1/Cip1 expression correlates with clinical outcome in vulvar carcinomas. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;95:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roma A A, Mistretta T-A, Diaz De Vivar A. New pattern-based personalized risk stratification system for endocervical adenocarcinoma with important clinical implications and surgical outcome. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;141:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Höckel M, Trott S, Dornhöfer N. Vulvar field resection based on ontogenetic cancer field theory for surgical treatment of vulvar carcinoma: a single-centre, single-group, prospective trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:537–548. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]