Abstract

Evidence from literature reveals that good governance practices influence citizens' attitudes and behaviours towards the government. Therefore, grounded on the good governance theory, the current study aimed to empirically examine how good governance practices promote public trust with the underlying mechanism of perceived government response on COVID-19 (PGRC) and moderating role of government agency's provision of quality information on social media (GQS). The data was collected from 491 followers of the Facebook account, Instagram, and Twitter pages of a government news agency, i.e., Associated Press of Pakistan and were analyzed using measurement and structural model by employing SmartPls 3.3.0. The results revealed a direct and indirect association of good governance practices with the public's trust in government via PGRC as mediator. Likewise, results showed that GQS interacts with PGRC and augments public trust in government. This study tried to contribute to the body of knowledge while addressing the gap related to the dearth of literature regarding government use of ICT during the COVID-19 pandemic to harvest benefits from social media while communicating with citizens on a larger scale. Moreover, the current study offers valuable practical and strategical recommendations to agencies and policymakers.

Keywords: Perceived government response on COVID-19, Responsiveness, Accountability, Transparency, Government Agency's provision of quality information on social media, Trust in government, Good governance theory

1. Introduction

In the contemporary world, the vibrant nature of the government role and the process of governance is among the most prominent and important concerns (Beshi & Kaur, 2020). People always seek their government to be responsible for each action taken to ensure that the public's interests are prioritized (Farazmand & Carter, 2004). Therefore, with time, the state's historical and traditional role is transformed, and the majority's interest became the key concern of the democratic governments (Grimmelikhuijsen, Porumbescu, Hong, & Im, 2013). Besides, the success of the democratic system depends upon the citizens' trust in government. Therefore, governments focus on enhancing public trust by efficiently executing policies and strategies (Houston & Harding, 2013). In connection to that, good governance practices, mainly comprised of responsiveness, accountability, and transparency, are important to satisfy the citizens at large (Beshi & Kaur, 2020). In comparison to good governance, sound governance is considered more comprehensive as it includes normative, technical, and rational features of good governance with superior quality (Farazmand, 2017). However, like many other nations, in Pakistan, the sound governance concept is not so popular yet; therefore, to overcome the prevailing challenges, good governance has been applied as a resolution, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Besides, the unexpected outburst of the COVID-19 pandemic made many governments apprehensive about the precautionary measure to curtail the virus's spread (Fetzer et al., 2020). Also, the response of the citizens towards those measures was one of the major concerns. As it was evident from many sources that at the beginning and hastening of the Coronavirus, people across 58 nations showed dissatisfaction for government response towards COVID-19; they perceived that the governments' necessary measures are insufficient (Hale, Petherick, Phillips, & Webster, 2020). This perception was further found to be affecting the citizens' trust level in government as they were worried about the fact that their government was not doing enough. Over time, a positive shift in citizens' trust level in governments was reported after the government announced the various measures in the public's best interests (Galle, Abts, Swyngedouw, & Meuleman, 2020). Likewise, the government of Pakistan has witnessed the enhanced public trust in government during the pandemic because of the various decision taken on an emergency basis, i.e., smart lockdowns, free health facilities, and financial help for the needy people.

Besides, social media is one of the rapidly advancing digital channels with 2.62 billion monthly active users worldwide in 2018 (Jackson et al., 2018; Statista, 2018). The number is grown to 4.3 billion in 2021 as per the global social media research summary 2021 based on its numerous unique features and fortes, including communication, openness, engagement and involvement (Tang, Miller, Zhou, & Warkentin, 2021; Warren, Sulaiman, & Jaafar, 2014). This is why social media is progressively gaining notoriety and grabbing the interest of administrations of developed countries that already started to exploit social media's collective dominance (Mossberger, Wu, & Crawford, 2013). Conversely, in developing countries, social media use at the governmental level is still at an informational stage (Ali, Jan, & Iqbal, 2013) as they mostly use the platforms of social media for news updates or important announcements. In contrast, the public uses social media more frequently and regularly.

Particularly in Pakistan, being a developing country, it is found that the number of monthly active users of social media reached 35 million (Arshad & Khurram, 2020). In the last few years, in Pakistan, government entities and pollical parties started using social media platforms to broadcast important information regarding decisions made at the state level (Ali et al., 2013). Although the use of social media is at the informational stage, the government gradually started to realize its important role (Memon, Mahar, Dhomeja, & Pirzado, 2015). Especially after the outbreak of COVID-19, the Prime minister of Pakistan appeared many times on social media platforms to announce various important decisions and make citizens aware of the government's timely measures and important decisions during the pandemic. as.

Moreover, to the best of the author's knowledge, no study to date has investigated the impact of the interactive effect of GQS and PGRC on building citizens' trust in government. Similarly, although past research reveals the impact of perceived responsiveness (Gil de Zúñiga, Diehl, & Ardévol-Abreu, 2017), perceived accountability (Farwell, Shier, & Handy, 2019; Yang & Northcott, 2019) and perceived transparency (Farwell et al., 2019; Porumbescu, 2015), on citizens' trust in government. However, still, there is a dearth of literature regarding the influence of all stated good governance elements in enhancing the citizens' trust in government in a single comprehensive framework generally and in developing nation context specifically. Hence, to fill these gap and, in the light of the paramount importance of good governance, it is substantial to examine the level of the public's trust in government and the ways it can be restored and improved (Arshad & Khurram, 2020), particularly in the COVID-19 pandemic situation.

Besides, the current study is established on good governance theory, which advocates the responsible, accountable and transparent management of human, financial, economic, and natural resources for sustainable and equitable development in political and government institutions (Beshi & Kaur, 2020). This requires the government to be accountable for its actions by implying transparency and citizens' access to information. Besides, governments also need to be responsive to their people's needs by exhibiting responsiveness and safeguarding human rights to gain public trust. Hence, grounded on the good governance theory, this study aims to examine the direct and indirect association of perceived responsiveness (PR), perceived accountability (PA), and perceived transparency (PT) with public trust in government (TIG) in the presence of perceived government response on COVID-19. In addition, the current study also investigates the interactive effect of GQS and PGRC on citizens' trust in government. To achieve these objectives, the current study is established on a quantitative methodology by conducting an online survey among the followers of a government news agency, i.e., Associated Press of Pakistan (APP). The study results will further provide valuable insights for practitioners and future researchers to explore more facts about the study area.

2. Literature review ND theoretical foundation

According to Houston and Harding (2013, p. 55), “trust refers to a willingness to rely on others to act on our behalf based on the belief that they possess the capacity to make effective decisions and take our interests into account”. Besides, trust is considered by many scholars as a complex, multifaceted and ambiguous concept and is viewed as being difficult to conceptualized and examine (Cheema, 2011; Van der Meer, 2010). Consequently, the impression of trust may have numerous shades and significance (Grimmelikhuijsen et al., 2013). More substantially, Barnes and Gill (2000) defined trust in government as the confidence that citizens have in authorities to do the right thing. The public expects the government entities to be upright, provide them with justice, safeguard their fundamental rights of food, health, shelter, and safety. Therefore, trust in government refers to the public's expectations regarding their political leaders and government agency's performance regarding how they commit, behave, and fulfil their responsibilities (Cheema, 2011). Hence, evaluation of government performance is based on trust that people instil in the government to run a state's functions (Yang & Holzer, 2006).

Governance is a border term used for government functions at all stages while reacting to citizens' joint or shared problems by fulfilling their needs in the best possible way (Griffin, 2010). According to (Kaufmann, Kraay, & Mastruzzi, 2010), “governance is a custom, practice, values, and organizations through which power in a state is executed involving the government selection procedure, replacement of government and accountability, honour and rights for citizens and ability of the state to devise and employ its policies”. Previous literature shows that it is difficult to agree upon a single perfect model for good governance fitting into all possible conditions (Jameel, Asif, & Hussain, 2019) as it is a complex structure comprised of multiple features and elements like responsiveness, accountability and transparency (Qudrat‐I Elahi, 2009). Accountability is conceptualized as the extent to which government is answerable for its decisions and actions to the public (Shafritz, Russell, & Borick, 2015). Transparency is termed as the clarity and accessibility of information provided by the government while keeping the public's interest into consideration (Mimicopoulos, Kyj, Sormani, Bertucci, & Qian, 2007). Perceived responsiveness is “the belief that government officials listen to and care about what citizens have to say” (Anderson, 2010, p. 64). At the same time, perceived government response on COVID-19 is defined as the government's prompt response to the pandemic situation to device the laws, regulations, and welfare decision-making in the public's best interest (Conway III, Woodard, & Zubrod, 2020). In the current study, the GPRC has been taken as how the government responded during pandemic times; when there was a dire need to respond quickly and effectively to control the spread of the virus and save the lives of the people and consider the well-being of the people on priority.

2.1. Good governance (PR, PA, and PT) and Citizens' Trust in government

Good governance needs to be implemented to attain the maximum level of public trust in the government (Jameel et al., 2019) as it advocates the government's idea to be inclusive and interactive with the public to compete at the national and international level (Speer, 2012). Simultaneously, perceived responsiveness relates to governments' response to the public's demands (Bratton, 2012) and is measured in terms of the government's willingness to respond to citizens' requests and complaints (Linde & Peters, 2020). Moreover, the responsive government is linked to attention, interaction, and provision of efficient feedback and measured by how well the public perceives that the government listens to them and respond to their queries (Qiaoan & Teets, 2020). According to Yousaf, Ihsan, and Ellahi (2016), the government's responsive decisions in the citizens' best interests significantly impact the citizens' TIG. A study conducted by Beshi and Kaur (2020) revealed a positive relationship between citizens' PR and TIG. Similarly, Lee and Porumbescu (2019) demonstrated the important role played by responsive governance in shaping public trusts in government while using e-government channels by disseminating valuable information to the public timely. Similarly, according to Wang (2002), responsive administration can enhance citizens' trust in government for a substantial period (Wang, 2002).

In good governance, PA is an imperative aspect to be considered by the government to create trust among the citizens (Rahaman, 2008). Russell (2019, p. 198) defined accountability as “the extent to which one should be answerable to their higher authority, officials or public for his actions”. Yang and Northcott (2019) explained the government's accountability as a substantial source of building trust. As trust is based on competence, benevolence, and honesty, hence by increasing people's knowledge about governments' policy-making, providing them open access to data as to where resources and funds are being used and how authorities are functioning, can give the perception of accountability (Porumbescu, 2017). Moreover, Wang, Medaglia, and Zheng (2018) stated that citizens rely more on governments that fairly communicate financial and non-financial matters with the general public.

Discloser of all the factors and figures related to important matters is called transparency (Farwell et al., 2019). It relates to providing information about major decision processes, functioning and performance (Sridhar, Gadgil, & Dhingra, 2020). Also, open access to information from governmental entities reflects transparency and creates a notion that the government is acting legally, leading to increased public trust (Nedal & Alcoriza, 2018). In recent years, many international laws, press and media freedom have emphasized access to information by the people from governing authorities (Moreno-Albarracín, Licerán-Gutierrez, Ortega-Rodríguez, Labella, & Rodríguez, 2020). Many governments are applying various digital means to become more transparent (Matheus, Janssen, & Janowski, 2021). Certain countries have enforced NPM (new public management) style, which advocates proactive transparency for gaining public trust (Song & Lee, 2016). Moreover, transparency is considered as a fundamental solution to the issues linked with democratic government; being transparent in decision-making and displaying information to the public governments win citizens' trust (Grimmelikhuijsen, Piotrowski, & Van Ryzin, 2020). Therefore, to create administrative transparency, several efforts are made at the government level that further enhance citizens' trust in government (Attiya & Welch, 2004; da Cruz, Tavares, Marques, Jorge, & De Sousa, 2016; Grimmelikhuijsen, 2012; Porumbescu, 2015). In connection to that, scholars stated that social media is a great platform that government can utilize to be fair and transparent in democratic matters to further build trust among the citizens (Bertot, Jaeger, & Grimes, 2010; Mergel, 2013). Likewise, Lee, Lee-Geiller, and Lee (2020) stated that one of the hallmarks of government services is their transparent nature and openness using various official websites to communicate with citizens. Thus, based on the above literature and good governance theory, which advocates that the government must respond to the public concerns in time to establish good governance with a fact that; PR, PA and PT facilitate the citizens to have a better insight of the work done by the government in utmost interests of the citizens to further strengthen their trust level on government. Hence, it is hypothesized that:

H1 a, b, and c

Citizens' perception of good governance (perceived responsiveness, perceived accountability, and perceived transparency) is positively associated with their trust in government.

2.2. Good governance (PR, PA, and PT) and perceived government response on COVID-19

The rapid spread of COVID-19 has resulted in a wide range of government responses all over the world. According to past researchers like Karp and Banducci (2008), citizens' perception of government response towards uncertain situations or natural disasters depends on good governance practices. After the coronavirus outburst in 2019, Liao et al. (2020) conducted a study and found a positive association between the perception of government responsiveness among the citizens and PGRC. Similarly, Sjoberg, Mellon, and Peixoto (2017) revealed that the public is more interested in participating in different activities if it perceives that the government will respond timely and in the best interest of the citizens is purely dependent ant upon the practices of good governance. Further, Shvetsova et al. (2020) asserted that good governance practices are positively associated with the government response to the COVID-19. Besides, Ojiagu, Nzewi, and Arachie (2020) examined the association of the PA and PT with nation-building, utilizing the COVID-19 pandemic as a yardstick and found their significant impact on government response in uncertain situations making decisions in the best interest of the public. Due to the sudden eruption of Coronavirus and multiple uncertain situations, very few scholars researched the PGRC specifically its association with good governance elements. Thus, to fill the gap in the literature and to find some more insights about the intensity of this relationship it is hypothesized that:

H2 a, b, and c

Citizens' perception of good governance (perceived responsiveness, perceived accountability, and perceived transparency) is positively associated with perceived government response on COVID-19.

2.3. Perceived government response on COVID-19 and trust in government

In response to the COVID-19 outbreak, the different course of actions has been witnessed from different nations both in terms of time taken to respond and types of measures adopted to sustain during pandemic (Hale et al., 2020), resulting in a debate among citizens and policymakers. “The Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT)” analyzed in detail the organized cross-national measure to access the response of the government during the pandemic, and it further illustrates that this response affected the citizens' trust in government directly (Hale et al., 2020). In a study conducted in health and medical science, Henderson et al. (2020) observed the important role of PGRC in shaping public opinion on government decisions. Similarly, Gates (2020) specified the importance of prompt and accurate government response during crises, specifically to ensure the best health facilities in the country to gain the citizens' trust in such circumstances. Houston and Harding (2013) stated that trust is a prerequisite for the overall system's smooth working. Therefore, governments should respond timely to overcome the anxiety, stress, behavioural and emotional difficulties among the public (Germani, Buratta, Delvecchio, & Mazzeschi, 2020). Adding to that, the perceived government response on COVID-19 has been directly linked with effective virus control (Pabbajah, Said, & Faisal, 2020). The citizens who presume that their government often interacted with them on various platforms, enforced SOP's to combat the spread of the virus and provided the best health care facilities possess greater trust in the government (Pabbajah et al., 2020). Similarly, lower death rates and the number of cases have also been associated positively with government response on the COVID-19 (Khemani, 2020). Finally, based on the available literature and on the fact that providing valid and timely response on various situations the government nurtures publics' trust in their government, it is proposed:

H3

Perceived government response on the COVID-19 is positively associated with citizens' trust in the government.

2.4. Mediation

2.4.1. Mediation of the perceived government response on COVID-19

Responsive governance plays a vital role in building trust in government (Porumbescu, 2017). Perceived responsiveness refers to government officials' willingness and ability to listen to the public’ opinion and make decisions accordingly (Bratton, 2012). The government entities' responsiveness is critical because failure to comply with people's demands or issues on time can lead to uncertainty and lack of trust, which have further consequences such as riots and rebellions among the masses (Miller, 2015). Especially in today's era of electronic and social media, government attention and responsiveness to meet their demands and expectations become crucial; therefore, government entities need to be responsible in their decision making to gain the trust of the masses (Qiaoan & Teets, 2020). The government entities use various electronic media to disseminate information to the citizens depicting accountability and transparency towards the public (Beshi & Kaur, 2020). Besides, modern technologies help citizens to understand the importance and accuracy of the various decisions taken by government entities based on prompt access to such information (Purwanto, Zuiderwijk, & Janssen, 2020).

Moreover, accountability deals with how the government uses resources, takes important policy decisions and communicates the same with citizens (Wang et al., 2018). The government entities making decisions based on the understanding that they have to justify those in front of the whole nation are considered more trustworthy (Yousaf et al., 2016). Transparent governments aim to create confidence among the public regarding the governments' decision-making process (Porumbescu, 2015), leading to a higher level of citizens' trust in governments (Yang and Northcott (2019). Besides, it is citizens' right to have access to the available information regarding all the important issues based on assumptions that the government which follows an open culture regarding sharing information with people has less room for cover-ups, lies, and malpractices (Grimmelikhuijsen et al., 2020).

Furthermore, some studies revealed the impact of citizens' perception of government responsiveness on the ways government entities responded to natural disasters (Sjoberg et al., 2017) and the COVID-19 (Ryan & El Ayadi, 2020). Besides, Ojiagu et al. (2020) reported the impact of perceived transparency and perceived accountability on PGRC. Simultaneously Liao et al. (2020) and Shvetsova et al. (2020) demonstrated the importance of PGRC to predict citizens TIG. But based on its novel nature, a gap exists in the literature regarding the underlying mechanism of PGRC in between the good governance elements and citizens' TIG. On the other hand, it is of immense importance to examine how the public perception of the government's transparency, accountability and responsiveness leads to an enhanced public trust in government through an interplay of the way government entities responded to the COVID-19 situation. Thus, to fill the gap in the literature, and based on good governance theory, which advocates that the government must respond to the public concerns in time to establish good governance, it is hypothesized that;

H4, b, and c

Perceived government response on COVID-19 will mediate the association between citizens' perception of good governance (perceived responsiveness, perceived accountability, and perceived transparency) and their trust in government.

2.5. Moderation

2.5.1. The moderating role of government Agency's provision of quality information on social media

The citizens' easier access to the information provided by the government agencies via social media platforms is an authentic source of gaining public trust for a longer period (Song & Lee, 2016; Tangi, Janssen, Benedetti, & Noci, 2021). The government's timely and effective response to uncertain situations using e-government platforms results in a higher level of trust among the citizens (Warren et al., 2014). Further, Arshad and Khurram (2020) revealed that the information provided by the government agencies regarding important decisions through social media is considered an authentic source of information and further enhances the trust level of the audience while coupled with the response of the government on different matters. Similarly, Tang et al. (2021) asserted that when government agencies disseminate valuable information on e-government websites, the public gets a clearer picture of the actions taken by the government in the best interest of their citizens, resulting in a higher level of trust among them on government. Moreover, Porumbescu (2017) examined the two channels of providing information by the government, i.e. e-government websites and social media and their association with citizens trust level on government and found positive results.

Besides, COVID-19 has by and large paralyzed global socio-economic activities, and it has severely affected the livelihood of society; experiences vary from country to country. In Pakistan, the government response to combat this pandemic was fairly good, keeping in view the resource constraints. The government has quickly recognized the pandemic's disastrous effect and established a main National Command and Operation Centre and COVID-19 Health Advisory Platform by the Ministry of National Health. An important step was that districts and tehsil level administrative and health staff were mobilized, and necessary resources were provided at the grass-root level. Moreover, the disaster management authority has been mobilized. Even though these departments were present, but the readiness and preparedness for the calamity were lacking. Therefore, with the establishment of the coordinating bodies, free and fair interactions have emerged, and for the first time, all the tiers of governance (federal, provincial, district and tehsil) get involved daily. This interaction provided many opportunities to manage the country affairs and promote social distancing with a clear and firm message, “stay home stay safe”, supported by the district administration to implement the SOPs for COVID-19 all over the country fully. In all these efforts, social media played an important role in providing the necessary input to respond to the challenges (Anser et al., 2020). Simultaneously, senior administrators, the chief ministers of all provinces and health authorities, have taken on the board to control the uncertain situation daily. Their decisions were regularly communicated to the public via government news agency APP and different media channels to synchronize communication. This helped streamline implementing better health practices and restoring the public trust in government in hard times. Thus, keeping into consideration the arguments mentioned above, initiatives taken by the government and the gap regarding the impact of the interaction effect of GQS and PGRS on citizens' trust in government, it is posited that:

H5

Government agency's provision of quality information on social media will moderate the association between perceived government response on COVID-19 and citizen’ trust in government such that the relationship will be stronger in case of higher values of government agency's provision of quality information on social media.

2.6. The theoretical framework of the study

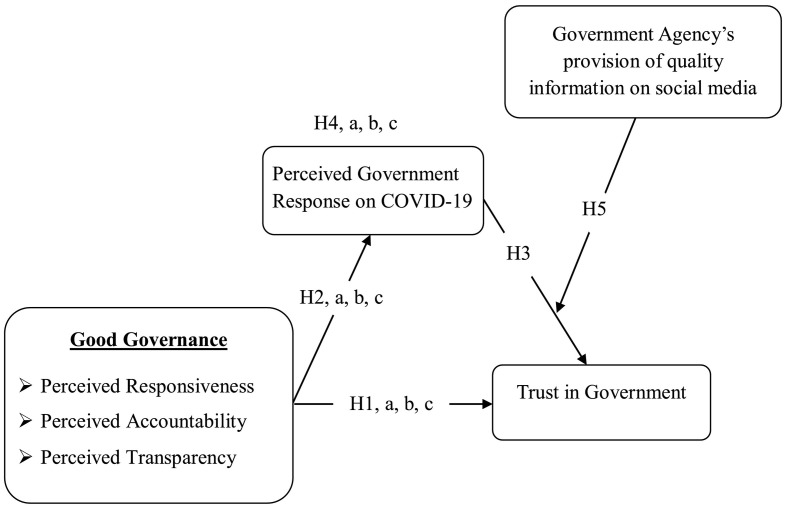

The theoretical framework of the current study (Fig. 1 ) is formulated based on the good governance theory, evidence and gaps found in the literature, especially in the context of Pakistan. The study proposed that good governance elements, including perceived responsiveness, perceived accountability, and perceived transparency, develop citizens' perception regarding government entities' proper functioning and decision-making, thus, enhancing their trust in government. Moreover, the perceived government response on COVID-19 has been studied as an underlying mechanism between the good governance elements and the public's trust in government. It is postulated that because of the mediating influence of the perceived government response on COVID-19, citizens' trust in government increases since they perceive that government entities are active to respond promptly and effectively in crises situations keeping the welfare of the masses on priority. Furthermore, when the official government agencies and entities communicate this response of the government to the public via social media channels within no time, this positive perception of government response during crises enhances and results in a higher level of trust. Therefore, the moderating role of the government agency's provision of quality information on social media has been studied between the association of perceived government response on COVID-19 and the public's trust in government. Fig. 1 illustrates the theoretical framework.

Fig. 1.

Theoretical framework of the study.

3. Research methods

3.1. Sampling and data collection

The theoretical framework of the study was empirically examined by selecting a case study of an agency, i.e. Associated Press of Pakistan (APP), by using quantitative research design as an appropriate survey methodology to acquire data based on public opinion, attitudes and behaviours about a subject matter with no intervention, biases or manipulation at researchers end (Kelley, Clark, Brown, & Sitzia, 2003). The required data set was gathered via survey from the followers of official Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook accounts of the Associated Press of Pakistan, a government-operated national news agency of Pakistan. The Associated Press of Pakistan's social media platforms is used to disseminate official, political and district news. The main aim of sharing content on social media is to spread the government's messages regarding multiple decisions taken at the state level to the maximum audience. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, the Associated Press of Pakistan remains active throughout to disseminate the government message to the public regarding multiple important aspects in the best interest of the public, whether those are related to smart local down, the closer of educational institutions and recreational places or limiting the direct contact of banking staff with customers etc.

The APP case was chosen based on its relevance with the good governance elements by providing relevant and transparent information to the citizens, and the government's response to COVID-19 first reached the citizens via APP. To approach the APP's followers was thought to be relevant and appropriate as they are directly exposed to the contents posted on social media platforms by the agency and are likely to have feelings of trust or lack of trust in the information provided to them. On the other hand, the rationale behind selecting only three social media sites, i.e., Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook, was that government agencies and citizens of Pakistan use these platforms most frequently and commonly. Until 15th July 2020, the total number of APP Instagram page followers was 479,100; Twitter account followers were 45, 900 and Facebook account followers were 57,590. During pandemic on each social media site of APP, one message can be seen #satyhomesavelives, representing government concern for its citizens at large. Social media active users following the APP were identified, and a message was sent to them with a cover letter. The letter had all the important details regarding the reason for conducting the research. The respondents have also been ensured that their details would be kept anonymous, and there are no bad intentions of the researcher to contact them and gather their valuable views, opinions and behavioural responses.

A total of 690 followers of the APP was approached via social media channels, i.e., Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook, by sending them messages regarding the author's intention to survey with a brief note regarding the nature of the study. Out of which 503 showed a willingness to participate in the survey. After the consent of the respondents, a questionnaire was sent to them containing four main parts, i.e., questions related to demographic information of the respondent, two general questions regarding the intensity of use of social media platforms by the respondents and the number of years they are following APP, and lastly questions regarding all study constructs measured on 5-point Likert scale. Additionally, to avoid bias, a written note was sent to the respondents and the main questionnaire. That was “Please fill out the following questionnaire. Keeping the Instagram page/Twitter account / Facebook page/ of APP in mind, indicate your level of agreement or disagreement with the following statements by selecting one of the options. The information provided will be used for research purposes only, and the respondents' confidentiality will be ensured. Please provide an accurate response; your opinions are valuable to us”. In addition, to ensure that the respondents fill the questioner completely, all the questions were marked as “required” that hold the compulsion to fill the complete questionnaire at the respondents' end, thus avoiding the chance of missing value. Still, after receiving 503 questionnaires when screening was done, 32 unengaged responses were excluded from the analysis. Finally, a total of 471 respondent's data was considered for further analysis, thus generating a response rate of 68.26%.

3.2. Measures of study

A survey consisting of 37 items was used to collect data from the study respondents (Appendix A). “Five-point Likert scale” was used to assess all items. Trust in government was measured with a five-item scale adapted from Grimmelikhuijsen (2012). This scale includes statements regarding the effective performance of the duties and sincerity of the government towards citizens to check the trustworthiness of the public towards the government. Perceived government response on COVID-19 (PGRC) was measured with a twelve-item scale adapted from Conway III et al. (2020). The scale includes statements that reflect the citizens' support for government decisions related to smart lockdowns while restricting the citizens' movements in public places. Also, respondents were asked about their support for government officials who were active in strictly ensuring SOPs in the country. Moreover, keeping in view the government efforts to utilize resources in vaccine discovery, respondents were also asked about their support for this cause. A statement regarding the government initiative for relief fund (Ahsaas program) for needy citizens to check the citizens' response was also included in the scale. The scale also has four reverse coded statements to ensure the respondents' engagement in filling the questionnaire. “Government agency's provision of quality information on social media” was measured with a seven-item scale adapted from Park, Kang, Rho, and Lee (2016) with statements related to providing accurate, sufficient timely and diverse information by the agency. A five items scale adapted from Vigoda-Gadot and Yuval (2003) was used to assess the perceived responsiveness of the respondents. The scale included statements related to the government's sensitivity towards citizens and the timely provision of information. To measure perceived accountability, a four-item scale adapted from Said, Alam, and Aziz (2015), containing statements regarding following rules and regulations by the government to take actions in the public's best interest, was used. Finally, to measure the perceived transparency, a four-item scale was adapted from Park and Blenkinsopp (2011), where respondents were inquired about the delivery of clear and transparent information by the government.

3.3. Demographic characteristics of the respondents

The respondents' demographic statistics indicated that most of them (63.6%) were males than females (36.4%). The ratio of participants was higher with two different age brackets, i.e., 31.6% were 20–30 years old, and 36.8% were 31–40-year-old, 21.2% of participants were between the age of 41–50 years. In contrast, only 10.5% of respondents were above 50 years old, representing that in Pakistan young generation is more active on social media platforms and take more interest in the news coming from government agencies. In qualification criteria, most of the respondents were well educated, having either bachelor's degree (41.1%) or master's degree (31.6%) in different fields, and 26.4% of participants had high school education upon further investigation via boxplot it was observed that most of these were students (19%). On the other side, 33.3% were employed, 19% were self-employed, and 14.3% were unemployed. A certain percentage (9.5%) of retired persons who use to follow the government agencies page/ account regularly and a certain number (4.9%) of homemakers also participated in the survey. The diverse demographic characteristics reflect that the selected sample for this research is highly representative of the public.

Moreover, in response to a question related to the number of years respondents using social media networks, it was surprising to see that most of the respondents (41.7%) replied for lowest tenure (1–3 years) in their reply, followed by 37.5% responses who reported to be the users of social media for 4–6 years. On the contrary, 16.7% of respondents were long-term users (7–10 years), and only 8.3% of respondents reported using social media networks for more than 10 years. These responses depict a change of trend among the public of Pakistan as they are getting more involved in online activities with time, and this can also be related to the uncertain situations arouse in-country due to COVID-19 and resultant smart lockdown measures taken by the government. This can further be related to the results of another question specifically asked about the respondents' intensity of visiting the pages/accounts of Associated Press of Pakistan (APP), which reflected that about half of the participants (47.8%) visit the APP pages/accounts on hourly bases, 30.4% respondents visit the APP pages/accounts on a daily basis followed by 21.7% who reported to visit APP pages/accounts twice a week respectively to know about the important announcements made by the government through this official news agency.

4. Results of the study

4.1. Data analysis

The SmartPLS version 3.3.0 was used to analyze the data and assess the hypothesized paths. For this purpose, measurement and structural models were used (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, 2006; Mansoor, Fatima, & Ahmed, 2020).

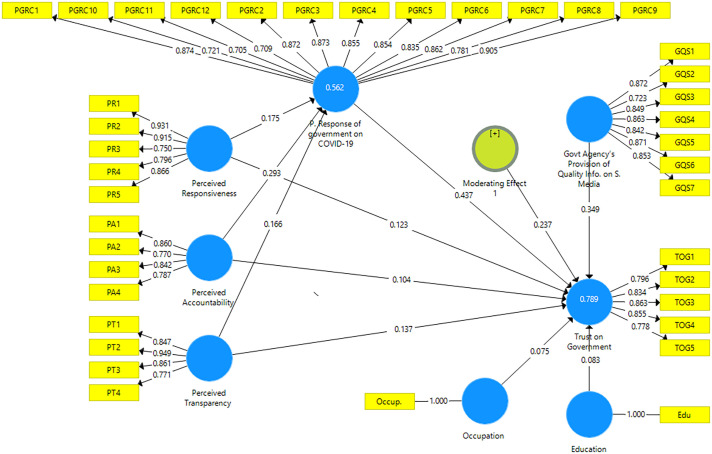

4.2. Assessing the measurement model

To assess the psychometric properties of the measures, confirmatory factor analysis was performed in SmartPLS 3.3.0. The reliability of the measures was assessed using “composite reliability (CR)” and “Cronbach's α” following the guidelines of Henseler, Ringle, and Sarstedt (2015). Table 1 depicts the reliability of all the reflective measures based on the values of CR and “Cronbach's α” (≥0.70). “Convergent and discriminant validity” was also assessed. Results revealed that all indicator variables' factor loadings were ≥0.70 with significant loading of each item (p < 0.001) onto its underlying construct (Fig. 2 ). Also, for all the study variables, the “Average Variance Extracted” AVE of the latent constructs was ≥0.50; therefore, “convergent validity “was established (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2010; Noor, Mansoor, & Rabbani, 2021).

Table 1.

Factor loadings, reliability, and validity.

| Constructs/indicators |

Factor Loadings |

AVE |

CR |

Cronbach's α |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||||

| Trust in Government | 0.682 | 0.915 | 0.891 | ||||||

| TIG1 | 0.796 | ||||||||

| TIG2 | 0.834 | ||||||||

| TIG3 | 0.863 | ||||||||

| TIG4 | 0.855 | ||||||||

| TIG5 | 0.778 | ||||||||

| Government Agency's Provision of Quality Information on Social Media | 0.706 | 0.944 | 0.887 | ||||||

| GQS1 | 0.872 | ||||||||

| GQS2 | 0.723 | ||||||||

| GQS3 | 0.849 | ||||||||

| GQS4 | 0.863 | ||||||||

| GQS5 | 0.842 | ||||||||

| GQS6 | 0.871 | ||||||||

| GQS7 | 0.853 | 0.704 | 0.950 | 0.872 | |||||

| P. Government Response on COVID-19 | |||||||||

| PGRC1 | 0.874 | ||||||||

| PGRC2 | 0.782 | ||||||||

| PGRC3 | 0.873 | ||||||||

| PGRC4 | 0.855 | ||||||||

| PGRC5 | 0.854 | ||||||||

| PGRC6 | 0.835 | ||||||||

| PGRC7 | 0.852 | ||||||||

| PGRC8 | 0.781 | ||||||||

| PGRC9 | 0.905 | ||||||||

| PGRC10 | 0.721 | ||||||||

| PGRC11 | 0.705 | ||||||||

| PGRC12 | 0.709 | ||||||||

| Perceived Responsiveness | 0.730 | 0.931 | 0.840 | ||||||

| PR1 | 0.931 | ||||||||

| PR2 | 0.915 | ||||||||

| PR3 | 0.750 | ||||||||

| PR4 | 0.796 | ||||||||

| PR5 | 0.866 | ||||||||

| Perceived Accountability | 0.665 | 0.888 | 0.821 | ||||||

| PA1 | 0.860 | ||||||||

| PA2 | 0.770 | ||||||||

| PA3 | 0.842 | ||||||||

| PA4 | 0.787 | ||||||||

| Perceived Transparency | 0.738 | 0.918 | 0.842 | ||||||

| PT1 | 0.847 | ||||||||

| PT2 | 0.949 | ||||||||

| PT3 | 0.861 | ||||||||

| PR4 | 0.771 | ||||||||

Fig. 2.

Full Measurement Model depicting the ß values (impact size) and factor loadings of all the study constructs' respective items as per the guidelines provided by Hair et al. (2006).

“CR, composite reliability; AVE, average variance extracted.”

4.3. Discriminant validity

Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio was assessed being an accurate measure of discriminant validity, as suggested by Henseler, Ringle, and Sinkovics (2009). Table 2 depicts that all the HTMT values were less than 0.9, as recommended by the scholars (Hair et al., 2010; Henseler et al., 2009).

Table 2.

Heterotrait-monotrait ratio.

| Constructs | Mean | STD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIG | 4.12 | 0.55 | 0.825 | |||||

| GQS | 4.07 | 0.67 | 0.731 | 0.840 | ||||

| PGRC | 3.91 | 0.76 | 0.500 | 0.511 | 0.839 | |||

| PR | 3.84 | 0.67 | 0.449 | 0.470 | 0.690 | 0.854 | ||

| PA | 4.22 | 0.43 | 0.619 | 0.562 | 0.543 | 0.565 | 0.815 | |

| PT | 4.04 | 0.55 | 0.601 | 0.667 | 0.654 | 0.418 | 0.412 | 0.859 |

“The square roots of AVEs of the constructs are shown in bold in diagonal.”

Where: TIG = Trust in Government; GQS = Government Agency's Provision of Quality Information on Social Media; PGRC = Perceived Government Response on COVID-19; PR = Perceived Responsiveness; PA = Perceived Accountability; PT = Perceived Transparency.

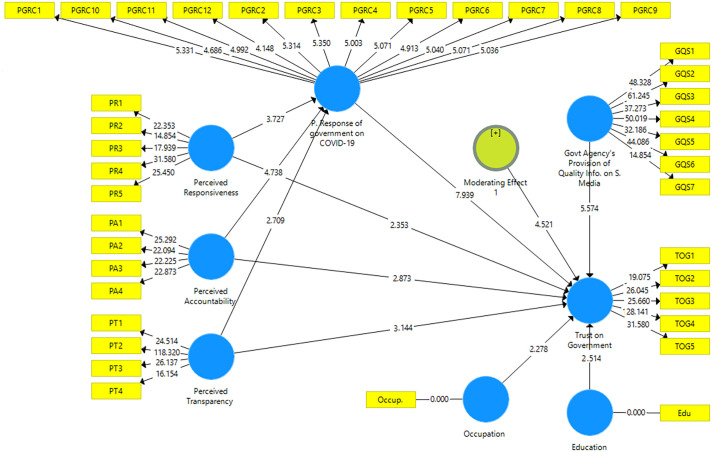

4.4. Assessing the structural model

Bootstrapping technique was employed to assess the structural paths as a nonparametric procedure. It allows testing the statistical significance of various PLS-SEM results and uses the sample data to estimate relevant characteristics of the population; therefore, to test the hypotheses, 5000 subsamples were used. Moreover, to confirm the hypothesized association ß-coefficient, p-values and t-values were assessed. Simultaneously, the Coefficient of Determination (R2) was utilized to check the model fitness.

4.4.1. Direct hypothesis

In Table 3 the results presented show a positive and significant relationship of citizen's TIG with PR (ß = 0.123**, t = 2.353), PA (ß = 0.104**, t = 2.873) and PT (ß = 0.137***, t = 3.144). Similarly, a positive significant association of PGRC was found with PR (ß = 0.175***, t = 3.727), PA (ß = 0.293**, t = 4.738) and PT (ß = 0.166***, t = 2.709**). Results further revealed that the PGRC positively and significantly affects the citizens' TIG (ß = 0.437***, t = 7.939). Therefore, H1 (a, b, c), H2 (a, b, c) and H3 are fully supported by the results. The R2 for the direct effect of perceived responsiveness, perceived accountability, and perceived transparency, on perceived government response on Covid19, was 0.562. Whereas the R2 for the main effect model on the citizens' trust in government was 0.610.

Table 3.

Hypothesis testing results

| Hypothesized relationships | Std. Beta | t-value | P-value | Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | PR ➔ TIG | 0.123 | 2.353 | 0.010 | Supported |

| H1b | PA ➔ TIG | 0.104 | 2.873 | 0.010 | Supported |

| H1c | PT ➔ TIG | 0.137 | 3.144 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H2a | PR ➔ PGRC | 0.175 | 3.727 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2b | PA ➔ PGRC | 0.293 | 4.738 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2c | PT ➔ PGRC | 0.166 | 2.709 | 0.010 | Supported |

| H3 | PGRC ➔ TIG | 0.437 | 7.939 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H4a | PR ➔ PGRC ➔ TIG | 0.201 | 4.128 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H4b | PA ➔ PGRC ➔ TIG | 0.122 | 3.247 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H4c | PT ➔ PGRC ➔ TIG | 0.163 | 3.938 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5 | PGRC * GQS ➔ TIG | 0.237 | 4.521 | 0.000 | Supported |

4.4.2. Mediating hypothesis

As shown in Table 3, the study's findings support the mediation hypotheses H4 (a, b, c). An indirect and positive effect of PR (ß = 0.201***, t = 4.128), PA (ß = 0.122***, t = 3.247), and PT (ß = 0.163***, t = 3.938) on citizens' TIG were found in the presence of PGRC as an underlying mechanism. As the total effect of the good governance elements (PR, PA, and PT) on citizens trust in government was 0.850*** out of which 0.364*** was the direct effect, and 0.486*** was indirect effect via the PGRC. These results signify the acceptance of mediation hypothesis 4a, 4b and 4c.

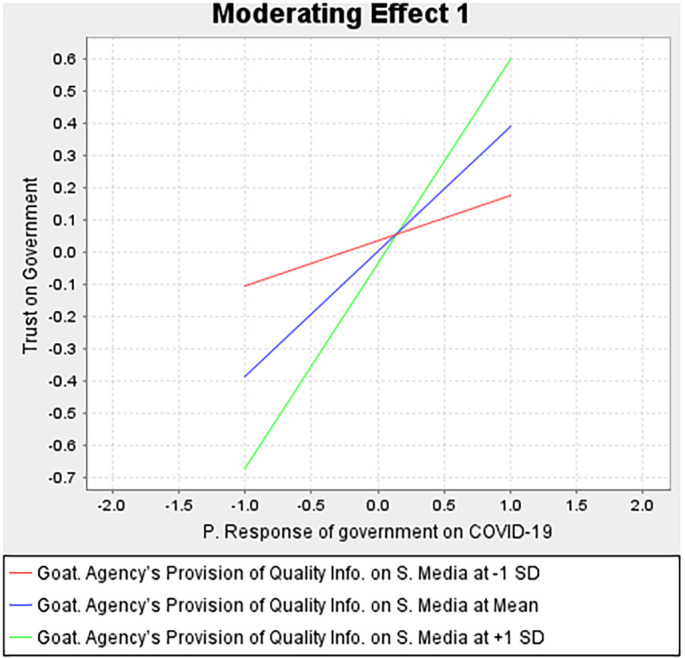

4.4.3. Moderating hypothesis

To assess the moderating effect of a construct in PLS-SEM, using the indicator approach and interaction terms between the moderator GQS and the predicting variable PGRC was created (Chin, Marcolin, & Newsted, 2003). The results supported the moderation hypothesis. Specifically, the results indicated significant interaction terms, GQS*PGRC (β =0.237, t-value = 4.521, p < 0.000), on the relationship of the PGRC and citizens' TIG. Following the moderation result, the R2 change between the main effect model and the moderation effect model was also examined. The R2 for the main effect for trust in government was 0.610, whereas its R2 with a coupled effect of the GQS and PGRC increased to 0.789. The R2 change suggested that the inclusion of an interaction term increased the explanation power of trust in Government by 17.9%. This enhanced explanatory power in trust in government will further result in strengthening the association between public and government for a sustainable period.

Based on the significant moderation effect, the interaction plot was used to interpret the nature of interaction following the guidelines of Dawson (2014). Fig. 3 shows that the line labelled for a higher level of GQS has a steeper gradient compared to the lower level of GQS for the association of PGRC with the trust of citizens' TIG. Thus, hypothesis 5 was also supported. Table 3 depicts the results for all hypothesized paths. Also, detailed results are shown in Fig. 4 .

Fig. 3.

Interaction plots for moderating effects.

Fig. 4.

Full structural model depicting the significance of the hypothesized paths as per the guidelines provided by Hair et al. (2006).

5. Discussion, implications limitations and future directions

5.1. Findings of the study

The current study applied good governance theory to empirically investigate the association of good governance practices with citizens trust in government directly as well as via underlying mechanism of perceived government response on COVID-19 and moderating role of government agency's provision of quality information on social media in between the relationship of perceived government response on COVID-19 and citizens' trust in government. The specific agency chosen for the current study was the Associated Press of Pakistan. Two demographic variables, i.e., education and occupation, were controlled during the analysis as their significant influence on the dependent variable was found. This is because more educated people squared the responsiveness, accountability, and transparency of the decisions taken by the government carefully while considering the dynamic nature of news coming from government agencies on social media from multiple perspectives. Thus, their understanding of government response on COVID-19 is established after analyzing the rationale behind those responses, ultimately in the public's best interest. Similarly, people in different occupations have different criteria to analyze and interpret the good governance practices and the perceived government response on COVID-19 based on multiple reasons. These reasons can be citizens' social media involvement and maturity level (students versus professionals), financial stability (varied between unemployed, employed and business people etc.), the dynamic nature of their roles in society (either retired and staying at home or simply homemakers) etc.

Besides, the respondents' demographic information revealed that most of the respondents were male (63.6%); the presence of this skewness is in line with the existing literature in the area of the study. For example, Ahmad, Ibrahim, and Bakar (2018) and Arshad and Khurram (2020) stated that in developing countries like Pakistan, women tend to use less internet specifically for social media platforms than men as compared to developed countries like the USA, where females are reported to be more regular social media users. Additionally, it is also evident from past trends and literature that usually women are less interested and expressive regarding their online views on social or political issues and generally use social media platforms for entertainment or communication objectives (Ahmad et al., 2018; Vicente & Novo, 2014). The same may be the case for a smaller number of females who participated in the survey being followers of the APP agency. It was also found that most of the participants (64.4%) of the study were young, ranging from 20 to 40 years of age. This might be because all over the globe, including Pakistan, the most frequent users of social media are young people (Arshad & Khurram, 2020; Vicente & Novo, 2014).

Moreover, all the study hypothesis was supported, which shows that good governance elements, i.e., PR, PA and PT are significant predictors of citizens' trust in the government. Also, the results revealed a positive and significant relationship of the perceived responsiveness with citizens' trust in government, as noticed by (Arshad & Khurram, 2020; Yousaf et al., 2016), reflecting the importance of government responsiveness in decision making in the best interest of the public. This further results in achieving a higher level of citizens' trust. The findings suggest that governments' representatives need to deal with the people's issues responsively and timely through various platforms to make them feel like an essential part of the government decision-making process.

Likewise, the findings related to the relationship of perceived accountability with trust in government are in line with the results of (Cheema, 2011; Farwell et al., 2019; Russell, 2019; Yousaf et al., 2016), who depicted the importance of accountability element in good governance for building and sustaining the trust of citizens on local governments. In context to that, during COVID-19, everyone has been allowed to visit any hospital testing centers so that the public has free access to the best health facilities without any discrimination of class and creed. Similarly, the results linked with the association of the citizens' perceived transparency with their trust in government are consistent with the outcomes of (Grimmelikhuijsen et al., 2020; Matheus et al., 2021; Porumbescu, 2015), who asserted the significance of transparent information dispersed by the government in achieving a higher level of citizens' trust in government. Moreover, in Pakistan, it has been observed during pandemic times that the government has launched a monetary fund to distribute loans among the needy and provide healthcare and medical staff resources where and when needed without any discrimination on a fair and transparent basis.

Besides, the findings related to the association of perceived (responsiveness, accountability, and transparency) with perceived government response on COVID-19 was in line with the outcomes of (Ojiagu et al., 2020; Shvetsova et al., 2020); like the transparent, responsive and accountable governments respond more quickly to the uncertain situations as for those the welfare of their people is the priority. The results depicting the association of perceived government response on COVID-19 and trust in government were similar to (Germani et al., 2020; Hale et al., 2020; Henderson et al., 2020). They demonstrated the significance of the timely response of the government to uncertain situations and natural disasters to achieve a higher level of citizens' trust.

Also, perceived government response on COVID-19 was found to be positively associated with public trust in government. This reflects the people of Pakistan appreciated the initiatives taken by the Pakistani government during the pandemic. That further resulted in an enhanced level of trust in the government. In connection to that, there are many initiatives that the government of Pakistan has taken during COVID-19; for instance, the federal government was very concerned that complete lockdown likely to damage the most vulnerable class, which is approximately 50% of the total population. The majority of them were daily workers. Due to economic slowdown and lockdown, they were kept back at homes. Therefore, the government initiated providing food and other monetary and health services to that deprived part of the country, resulting in voluntarism. The local community also started to help the needy ones.

Furthermore, the second wave of pandemic government has used ICT and coordination with the districts and tehsils by introducing smart lockdown. Precisely identifying the areas and location with diagnosed disease prevalence and that area was completely sealed, and mobility was shut down. Whereas the areas with satisfactory situation were allowed to carry out their socio-economic activities while ensuring that the public must observe social distancing, mask-wearing and healthy practices while they outside at work. The current study also proved the mediatory role of Perceived government response on COVID-19 among the association of good governance elements and trust in government, proving that response of the governments is the key to overcome the unseen damages because of sudden uncertain situations.

Finally, the findings also revealed that the agency's provision of quality information on social media positively and significantly interacts with the perceived government response on COVID-19 and enhanced the trust among citizens in government. This result is consistent with the findings of existing studies, which proved that “agency's provision of quality information on social media” impact the public's trust in government (Arshad & Khurram, 2020; Bertot et al., 2010; Bonsón, Torres, Royo, & Flores, 2012; Tang & Lee, 2013). As the disclosure of information by the agencies of government results in a reduction in fallacies of the public by making them understand the motives behind decisions made by the government, resulting in a higher level of trust among residents in government (Grimmelikhuijsen et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2020; Pittaway & Montazemi, 2020). Thus, the provision of quality information by APP on social media in Pakistan expressively boosts their followers' acuity regarding the agency's responsiveness. It resulted in a higher level of trust among citizens in government, providing two-way communication on social media, i.e., empowering the public to have an insight into the relevant information provided by the agency and connecting the public directly with the government while providing their feedback.

5.2. Theoretical implications

The current study's theoretical contributions are manifold. First, it has uniquely considered the validation of good governance theory, which has been used for years to deal with different societies' concerns regarding political and social perspectives, with PGRC and citizens' TIG in a single comprehensive framework. This research also helped answer the questions from past literature about declining trends of public trust in local governments, especially in developing nations. Another significant advancement of this research is a developing country context that provides insights for all developing nations striving for good governance to retain public trust. Besides, this study is unique in the context of Pakistan, given that no empirical evidence has been found for the mediatory role of the perceived response of government on COVID-19 in between good governance practices and trust in government. The current study also revealed that free and fair interaction and engagement among the different stakeholders' offload misperception, apprehension, inhibitions and fatalistic ideas. In context to Pakistan, several incidents during the COVID-19 took place that had initially reflected a sort of confusion had been compounded in responding to challenges of COVID-19. But at the later stage, the establishment of multiple bodies, i.e., National Command and Operation Centre and COVID-19 Health Advisory Platform by Ministry of National Health etc., people started responding to the challenges in a befitting manner.

Moreover, in a developing country like Pakistan, social media platforms are still at their early stages. Developing countries are incorporating it with a continuous increase in demand to scrutinize the innovative ways to utilize these tools by the government (Memon et al., 2015). The current study attempts to shed some light on the inherent benefits of using social media platforms that allow citizens to access the valuable information available on these platforms. Similarly, no study up to date has investigated the interactive effect of quality information provided by government agencies on social media generally and specifically in the context of Pakistan, resulting in a higher level of public trust in government. At large current study contributes to the body of knowledge about the benefits of fair governance practices, governments' timely response on COVID-19 in unpredictable circumstances and the use of social media platforms to disseminate the important news on time in the best interest of the public. It also creates awareness among government bodies towards their responsibilities to encourage citizens to take an interest in democratic matters for valuable feedback and suggestions for constructive input that can help gain legitimacy of current practices by citizens. Also, government agencies need to understand that interactive participation is only possible by continuously taking citizens views related to strategies in the decision-making process instead of imposing their decisions on citizens.

5.3. Practical implications

The current study was conducted to investigate the underlying mechanism of factors leading to public trust in government; hence it can be highly insightful for policymakers, politicians, public administrators, and government officials in multiple ways. The governments' prime responsibility is to formulate strategies in the public's best interest that depict the elements of responsiveness, accountability, and transparency in their decisions. Along with wise decision-making regarding critical matters, government entities must communicate the same in a timely and effective manner with the public to trust the government entities. This trustworthiness further results in good law and order situation in a country as satisfied citizens display decent behaviour and follow the rules and regulations, perceiving them beneficial for society. Moreover, the public's investment rate can be increased by increasing their confidence in the government's decision-making process to further enhance economic development, resulting in sustainable prosperity.

The recent experience of the COVID-19 has empirically substantiated that the federal and provincial government's real task is to empower district and tehsil level governance. It could be instrumental in reinforcing socio-economic progress prosperity and strengthening social institutions to enhance economic and social wellbeing at the grass-root level. Moreover, the administration has to recognize that reforming attitude and behaviour with the public will likely enhance their capacity to manage such crises and develop a cordial relationship. The social perceptibility of the public till the second wave remarkably improved. It is, however, observed that there is a withdrawal effect from prosocial behaviour. This aspect could only be prevented and consistent with adhering to SOPs if social institutions like education and health are effectively mobilized at the lower administrative level.

Adding to that, the government should synchronize communication among all the administrative and public services layers. Establishing a single portal has become imperative for governments and public service organizations to take decisive actions using modern management techniques and resolve the public problem without any rhymes and reasons. Furthermore, synchronizing all four tiers (federal, province, district and tehsil level) through effective communication resource could be better managed and engaged in developing countries like Pakistan having many economic constraints. Besides, trust is established when people experience the good value of public services; in the current pandemic situation, when the basic health services and basic facilities are adequately provided to the people. As in Pakistan, there are 33 million households, and the financial vulnerability of one third is very week. At the same time, COVID-19 has further undermined their lives and livelihood. Therefore, every country must develop “coordinating corona control and relief cells” for comprehensive policy frameworks that create job opportunities among this vulnerable class.

Moreover, this study can provide valuable insight to the APP and other government agencies by apprehending that their provision of quality information on social media vintages many constructive results. For instance, the enhanced trust among their followers regarding responsive functioning of the agency. Further, the APP and other government agencies may inspire their followers to provide their suggestions and opinions and express their views to participate more in state functions by implementing various social media strategies. It can further ensure citizens that their valuable participation is vital for the accurate decision-making process of the government agencies and the smooth functioning of the country at large. Furthermore, the APP case can be considered a sample by other government agencies in Pakistan and other developing countries where there is still room for effectively utilizing the social media platforms to approach the public. In this way, citizens' lost trust in governments in different developing countries can be restored and enhanced, resulting in an environment of happiness and prosperity.

Furthermore, the governments of all developing countries should understand the need for the development of proper IT infrastructure all over the country to provide internet facilities to all citizens, especially to those living in remote areas. This way, many citizens will have access to e-government channels to express their views at a higher level. Likewise, it is the citizens' responsibility to realize that various benefits can be extracted for the countries' overall smooth functioning from their active participation and cooperation with government agencies. Finally, it is a peak time during the COVID-19 pandemic that developing countries' governments and the public recognize their respective role in evolving a comprehensive society by systematically moving ahead for the prosperity of the whole nation.

5.4. Limitations and future directions

Despite the several significances, there are also few limitations of the study. First, the current study focused on collecting data by gathering the opinions of social media followers of a single agency (APP), limiting the generalizability of the results. However, future researchers can broadly examine the other agencies' opinions based on their social media usage intensity. They can compare the data collected from different agencies in terms of the authenticity of the information provided by them and the development of the variable trust level of citizens on different agencies. The researchers may also conduct studies with active social media users who do not follow the pages/accounts of government news agencies and explore its reason. A study can also be conducted about the citizens' political participation on social media and traditional platforms other than social media. A comparison can be made between the social media users and non-users who want their political participation in state matters and vice versa. Secondly, as the current study is based on a convenience sampling technique, most of the respondents who participated in the survey were young males, limiting the generalizability of the results to both age and gender. The futures research can be conducted on quota-based sampling technique in which a certain equal percentage of age groups can be fixed along with a 50% division of total sample among males and female participants to overcome this limitation. Further, a longitudinal research design facilitates researchers to understand better the association among the study variable. Thirdly, the small sample size (N = 491) may not truly represent the whole population. In contrast, future researchers can overcome this limitation with extensive data set. Finally, a modern statistical tool, i.e., SmartPLS 3.3.0, was used to investigate the hypothesized relationships and assess the instrument's validity and reliability. This constitutes the quantitative testing of the phenomenon under study. In contrast, a mixed-method approach in which, along with the quantitative examination of the respondents' opinions, in-depth interviews can be conducted to deepen the results and identify the other possible constructs involved in the trust-building process of citizens on government.

6. Conclusion

While fighting with COVID-19, the most critical role was played by governments who had to enforce SOP's and devise strategies to control the spread and decrease the death rate to a minimum along with the fulfilment of all the basic needs of the citizens (Al-Hasan, Yim, & Khuntia, 2020). The most important factor in this scenario is the trust that the public places in the government. Established on good governance theory, the conjecture of this study presumed that good governance practices, i.e., perceived responsiveness, perceived transparency and perceived accountability, are positively associated with the trust in government directly and via the underlying mechanism of perceived government response on COVID-19. The interactive effect of government agency's provision of quality information on social media and perceived government response on COVID-19 has also been analyzed to check the enhanced level of trust among the public of Pakistan by adopting a quantitative survey design and conducting a survey of 491 followers of official Twitter, Instagram and Facebook pages of Associated Press of Pakistan. The results support the hypothesis and theoretical framework of the study. The COVID-19 experience also revealed that Pakistan's governance structure evolved as a function of continuous interaction and engagement of all the government tires. This interaction and engagement provided a unique opportunity for public service providers, professionals, and frontline workers to view the situation in their locality and community and take initiatives without compromising broad guidelines and key adherence parameters. Besides, during COVID-19 in Pakistan, government officials freely and fairly interacted with the public without any apprehension and inhibition. Operational people were given a fair amount of opportunity to share their experience that served as valuable input. They started associating their identity with the cause as a function of engagement and interaction besides acknowledging their hard work. Moreover, this study contributes to the body of knowledge about the benefits of the government's ICT usage by providing empirical evidence; if the interaction and communication continue regularly, it will create a culture of healthy practices resulting in a sound and sustainable society.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Biography

Mahnaz Mansoor holds an MS degree (2018) with gold medal and distinction certificate in management Sciences from International Islamic University Islamabad (IIUI), Pakistan. She is a PhD. Scholar at Comsats University Pakistan and a faculty member at Hamdard University Islamabad Campus (HUIC). Her current research interest includes e-governance, social media, Sustainable Development goals and organizational studies etc. Email: mahnaz.mansoor@hamdard.edu. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0954-2482

Appendix A. Measurement items used for data collection

| Variable | Statement | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Trust on Government | 1. Public authorities in the government are acting in the interest of the public. Public authorities in the government are capable. 3. Public authorities in the government carry out their duties effectively. 4. Public authorities in the government are sincere. 5. Public authorities in the government are honest. |

Grimmelikhuijsen (2012) |

| Perceived Responsiveness | 1. The government is sensitive to public opinions. 2. The government responds to public requests quickly. 3. The government is making a sincere effort to support those residents who need help. 4. The government is efficient in providing quality solutions for public needs. 5. Citizen's appeals to the government are treated properly within a reasonable period of time. |

Vigoda-Gadot and Yuval (2003) |

| Perceived Accountability | 1. The government has a regular reporting system on the achievements and results of the program against its objectives. 2. The government recognizes its responsibility towards the public. 3. The government follows treasury rules and regulations in all circumstances. 4. The government ensures proper usage of its budget in an authorized manner. |

Said et al. (2015) |

| Perceived Transparency | 1. The government plan and program are implemented transparently. 2. The entire process of the government is transparently disclosed. 3. The public can clearly see the progress and situations of the government administration. 4. The government discloses sufficient information to the public about its performance. |

Park and Blenkinsopp (2011) |

| Government agency's provision of quality information on social media | 1. (I feel that) the agency's Instagram page/Facebook page/Twitter account provides sufficient contents of news & information for me to understand and get necessary facts. 2. The agency's Instagram page/Facebook page/Twitter account provides accurate information to me to understand the government & policy news correctly. 3. The agency's Instagram page/Facebook page/Twitter account provides diverse and various information to me. 4. The agency's Instagram page/Facebook page/Twitter account provides the news & information timely. 5. The agency's Instagram page/Facebook page/Twitter account provides access to other information sources to me (e.g. links to useful government websites) ⁎. 6. The agency's Instagram page/Facebook page/Twitter account provides additional access to other information channels to me (e.g. link to agency's website, contact information) ⁎. 7. The agency's Instagram page/Facebook page/Twitter account provides appropriate information to me. |

Park et al. (2016) |

| Perceived Government Response on COVID-19 | 1. I support government measures to restrict the movement of Pakistani citizens to curb the spread of Coronavirus (COVID-19). 2. We have strong government officials right now to take action to stop the spread of disease. 3. I want my country's government to severely punish those who violate orders to stay home. 4. It is vital right now that the government strongly enforces social distancing measures. 5. I am upset at the thought that government would force people to stay home against their will. ® 6. It makes me angry that the government would tell me where I can go and what I can do, even when there is a crisis such as Coronavirus (COVID-19). ® 7. I think we should spend most of our government resources right now towards finding a vaccine (or other medical cure) for Coronavirus (COVID-19). 8. I support government research on Coronavirus (COVID-19) because I think that is the best way to stop it. 9. I think it is the government's good idea to give individual citizens money back during these difficult times to increase spending and keep business going. 10. I think my country's government “Ahsaas Program” package during the virus spread is a good idea. 11. I distrust the information I receive about the Coronavirus (COVID-19) from the government. ® 12. I think the government has an agenda that is causing them not to give the whole story to the populace. ® |

Conway III et al. (2020). |

References

- Ahmad A., Ibrahim R., Bakar A. Factors influencing job performance among police personnel: An empirical study in Selangor. Management Science Letters. 2018;8(9):939–950. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hasan A., Yim D., Khuntia J. Citizens’ adherence to COVID-19 mitigation recommendations by the government: A 3-country comparative evaluation using web-based cross-sectional survey data. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2020;22(8) doi: 10.2196/20634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali Z., Jan M., Iqbal A. Social media implication on politics of Pakistan. Measuring the impact of Facebook. The International Asian Research Journal. 2013;1(1):13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M.R. Community psychology, political efficacy, and trust. Political Psychology. 2010;31(1):59–84. [Google Scholar]

- Anser M.K., Yousaf Z., Khan M.A., Nassani A.A., Abro M.M.Q., Vo X.H., Zaman K. Social and administrative issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic in Pakistan: Better late than never. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2020;27(27):34567–34573. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-10008-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arshad S., Khurram S. Can government’s presence on social media stimulate citizens’ online political participation? Investigating the influence of transparency, trust, and responsiveness. Government Information Quarterly. 2020;37(3):101486. [Google Scholar]

- Attiya H., Welch J. Vol. 19. John Wiley & Sons; 2004. Distributed computing: Fundamentals, simulations, and advanced topics. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes C., Gill D. State Services Commission; New Zealand: 2000. Declining government performance? Why citizens don't trust government. [Google Scholar]

- Bertot J.C., Jaeger P.T., Grimes J.M. Using ICTs to create a culture of transparency: E-government and social media as openness and anti-corruption tools for societies. Government Information Quarterly. 2010;27(3):264–271. [Google Scholar]

- Beshi T.D., Kaur R. Public trust in local government: Explaining the role of good governance practices. Public Organization Review. 2020;20(2):337–350. [Google Scholar]

- Bonsón E., Torres L., Royo S., Flores F. Local e-government 2.0: Social media and corporate transparency in municipalities. Government Information Quarterly. 2012;29(2):123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Bratton M. Citizen perceptions of local government responsiveness in. Sub-Saharan Africa. 2012;40(3):516–527. [Google Scholar]

- Cheema G.S. Swedish International Centre for local Democracy. 2011. Engaging civil society to promote democratic local governance: Emerging trends and policy implications in Asia.http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download [Google Scholar]

- Chin W.W., Marcolin B.L., Newsted P.R. A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Information Systems Research. 2003;14(2):189–217. [Google Scholar]

- Conway L.G., III, Woodard S.R., Zubrod A. 2020. Social psychological measurements of COVID-19: Coronavirus perceived threat, government response, impacts, and experiences questionnaires. [Google Scholar]

- da Cruz N.F., Tavares A.F., Marques R.C., Jorge S., De Sousa L. Measuring local government transparency. Public Management Review. 2016;18(6):866–893. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson J.F. Moderation in management research: What, why, when, and how. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2014;29(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Qudrat‐I Elahi K. UNDP on good governance. International Journal of Social Economics. 2009;36(12):1167–1180. [Google Scholar]

- Farazmand A. Governance reforms: The good, the bad, and the ugly; and the sound: Examining the past and exploring the future of public organizations. Public Organization Review. 2017;17(4):595–617. [Google Scholar]

- Farazmand A., Carter R. Greenwood Publishing Group; 2004. Sound governance: Policy and administrative innovations. [Google Scholar]

- Farwell M.M., Shier M.L., Handy F. Explaining trust in Canadian charities: The influence of public perceptions of accountability, transparency, familiarity and institutional trust. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations. 2019;30(4):768–782. [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer T., Witte M., Hensel L., Jachimowicz J., Haushofer J., Ivchenko A.…Fiorin S. 2020. Global behaviors and perceptions in the COVID-19 pandemic. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]