Abstract

Background

COVID-19 has exacerbated material hardship among grandparent-headed kinship families. Grandparent-headed kinship families receive financial assistance, which may mitigate material hardship and reduce child neglect risk.

Objective

This study aims to examine (1) the association between material hardship and child neglect risk; and (2) whether financial assistance moderates this association in a sample of kinship grandparent-headed families during COVID-19.

Participants and setting

Cross-sectional survey data were collected from a convenience sample of grandparent-headed kinship families (not necessarily child welfare involved) (N = 362) in the United States via Qualtrics Panels online survey.

Methods

Descriptive, bivariate, and negative binomial regression were conducted using STATA 15.0.

Results

Experiencing material hardship was found to be associated with an increased risk of child neglect, and receiving financial assistance was associated with a decreased risk of child neglect in the full sample and a subsample with household income > $30,000. Receiving financial assistance buffered the negative effect of material hardship on child neglect risk across analytic samples, and receiving SNAP was a significant moderator in the full sample. Among families with a household income ≤ $30,000, receiving SNAP and foster care payments was associated with a decreased risk of child neglect, while receiving TANF and unemployment insurance was associated with an increased risk of child neglect. Among families with household income > $30,000, only receiving SNAP was associated with a decreased risk of child neglect.

Conclusions

This study suggests the potential importance of providing concrete financial assistance, particularly SNAP and foster care payments, to grandparent-headed kinship families in efforts to decrease child neglect risk during COVID-19.

Keywords: Material hardship, Child neglect, Kinship care, Grandparents, COVID-19, Financial assistance, SNAP, Foster care payment, TANF

1. Introduction

In the United States, >2.6 million children are raised by their relatives, predominantly by their grandparents (Kids Count Data Center, 2019). Becoming kinship grandparents with the responsibility to provide full-time care is associated with a myriad of challenges (Lee et al., 2016), including parenting stress, financial hardship, complex intergenerational relationships, and dealing with children's trauma and behavioral problems (Lee et al., 2016), which are superimposed on preexisting declined physical and mental health conditions (Hayslip Jr & Goodman, 2008). Given the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a wide range of social, economic, and health-related consequences on individuals and communities (World Health Organization, 2020), it is likely that it has also impacted the caregiving of kinship grandparent caregivers for children in their care. Research has found that COVID-19 has particularly impacted vulnerable groups, including older adults, visible minorities, people with pre-existing health conditions, and low-income populations (Bowleg, 2020). Many grandparents raising their grandchildren fit into this vulnerable profile as they are likely to be older (Bavier, 2011) and of low economic status (Baker & Mutchler, 2010). Moreover, both characteristics are associated with a high risk of experiencing material hardship in the time of COVID-19 (Xu et al., 2020c). Of note, material hardship has been one of the most significant challenges facing grandparent-headed kinship families, and their needs for financial assistance have been a longstanding issue prior to COVID-19 (Berrick & Boyd, 2016). Material hardship and other stressors, such as parental stress and mental distress, have been associated with an elevated risk of child neglect (Slack et al., 2011). To assist kinship families regardless of their involvement with the child welfare system, the government provides financial assistance to meet children's needs (Xu, Bright, et al., 2020a). Providing financial assistance may be a promising strategy to reduce child neglect risk (Duva & Metzger, 2010). The current study aims to (1) examine the association between material hardship and child neglect risk, and (2) test whether receiving financial assistance moderates this association in a sample of grandparent-headed kinship families during COVID-19.

1.1. Theoretical framework: economic stress model of child maltreatment

This study is guided by the economic stress model of child maltreatment (Slack & Berger, 2017). This model illustrates the associations between economic hardship and stress and child maltreatment risk and identifies pathways (e.g., parenting stress, mental health) from economic hardship to child neglect risk. We use this model to examine the association between material hardship and child neglect risk and adapt it to investigate the role of financial assistance as a moderator in the association between material hardship and child neglect risk.

1.2. Material hardship and child neglect risk

Material well-being is a multidimensional concept that measures basic needs that are essential to a family's well-being. The primary metrics of lack of material well-being, or material hardship, are food insecurity, housing instability, bill-paying difficulty, and medical hardship (Baker & Mutchler, 2010). One of the most significant challenges facing grandparent kinship families is material hardship (Ehrle & Geen, 2002; McLaughlin et al., 2016). One-third of children living with grandparents live below the poverty line (Pac et al., 2017). However, using income or poverty line is often not an adequate indicator to measure family hardship as families living above the poverty line also experience material hardship (Rose et al., 2009). Therefore, it is important to examine other indicators of material hardship, in addition to an income-based measurement of poverty (Baker & Mutchler, 2010). A prior study by the study authors found material hardship to be associated with increased mental distress and parenting stress for kinship caregivers (Xu et al., 2020b, Xu et al., 2020c), both of which have been identified as risk factors for child neglect (Slack et al., 2011).

Child neglect is the most common type of child maltreatment in the U.S. (Department of Health and Human Services, 2020) and is strongly associated with poverty (Jonson-Reid et al., 2012; Slack et al., 2011). Children from families struggling with meeting basic material needs are more likely to experience neglect (Lefebvre et al., 2017). Yang's (2015) study on 1135 families found that housing and food hardships are associated with neglect, rather than other types of maltreatment. Material hardship (e.g., housing hardship) has been associated with neglect due to the economic stress placed on caregivers and the family (Lefebvre et al., 2017). A lack of basic and essential needs has been found to increase parental anger, hostile response, and impatience towards children, leading to changes in caregiver behaviors, family dynamics and parental mental health (Berger, 2007; Cancian et al., 2013). These findings suggest that combating material hardship via the provision of financial assistance may decrease parenting stress and mental distress and further prevent child neglect.

1.3. Financial assistance for kinship families

Kinship families are primarily eligible for two types of financial assistance related to foster care, such as foster care payments and kinship guardianship assistance payments (Berrick & Boyd, 2016). These payments generally require kinship caregivers to become licensed foster parents (Berrick & Boyd, 2016). Families may qualify for other forms of financial assistance based on need or employment status, such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and unemployment insurance (Murray, Ehrle, Geen, 2004). A more detailed description of financial assistance for kinship families is presented below.

1.3.1. Foster care payments

Foster care payments, provided to facilitate foster caregivers' ability to meet the needs of children in their care (Social Security Administration, 2014), range from $555 to $655 on average per month in the United States, depending on the child's age (Ahn et al., 2018). If kinship caregivers meet certain criteria (e.g., home study, background check) for being a licensed foster parent, they are eligible to receive it (Park, 2005). Despite eligibility, studies have found that only between 33% and 50% of kinship families receive foster care payments (Murray, Ehrle, Geen, 2004; Xu, Bright, et al., 2020a). Some potential reasons for not receiving foster care payments include caregivers' hesitation to be involved with the child welfare system and lack of awareness of the availability of foster care payments (Ehrle et al., 2001).

1.3.2. Kinship guardianship assistance payments

Kinship guardianship assistance payments are subsidies for children who are placed with a legal relative guardian (Stoltzfus, 2012). In other words, kinship guardianship assistance payments are only available to kinship caregivers caring for children who are in foster care (Children's Bureau, 2013). Most kinship caregivers receive these payments as a part of kinship children's permanency plan, when it is impossible for them to reunify with their biological parents (Park, 2005). The amount of guardianship assistance payments is less than or equal to foster care payments (Park, 2005). The Kinship Caregiver Support Act has permitted some states to use federal foster care funding to establish or expand a subsidized guardianship program since 2006 (Goelitz, 2007), but this program is not available across all states.

1.3.3. TANF

In addition to kinship foster care-related financial assistance, some kinship families are eligible for financial assistance through TANF, a federal program to help low-income families to achieve self-sufficiency (Office of Family Assistance, 2017). TANF replaced Aid to Families with Dependent Children (ADFC) in 1996 (Burek, 2006). Under AFDC, the federal government started to provide financial support for kinship caregivers (Anderson, 2006). Although the current TANF program is not designated to assist kinship families, many TANF funds have been used for kinship families (Children's Defense Fund, 2004). TANF grants include TANF family grants and child-only grants. TANF family grants, a means-tested program, are only available to families that meet certain income criteria, while TANF-child only grants assess the child's income and needs, and almost all kinship families are eligible (Children's Defense Fund, 2004). Among kinship families involved in the child welfare system, Xu, Bright, et al. (2020a) found that almost 14% of kinship families received TANF family or child-only grants, with about 13% of these families receiving TANF and foster care payments simultaneously at the national level. Similarly, about 12.0% to 23.8% of kinship foster families in California receive TANF family or child-only grants (Berrick & Boyd, 2016).

1.3.4. SNAP

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many families have lost their jobs and experienced food insecurity (Laborde et al., 2020; Lawson et al., 2020). Kinship families are no exception. Households with children are facing especially higher food hardship than households without children (Schanzenbach & Pitts, 2020). SNAP is a type of food assistance that helps low-income people buy food to reduce food insecurity (Department of Agriculture, 2019). Eligibility criteria include: working for low wages, part-time, unemployed; receiving welfare or other public assistance payments; elderly or disabled; and low-income or homeless (Department of Agriculture, 2019). The gross monthly income limits were $ 28,236/year (130% of poverty) in a household with three family members in 2020 (Department of Agriculture, 2020a). In the face of COVID-19, the federal and state governments have waived some SNAP criteria and provided extensions of emergency allotment (Department of Agriculture, 2020b).

1.3.5. Unemployment insurance

The federal unemployment insurance system is designed to help those who have lost their jobs by temporarily replacing part of their wages (Department of Labor, n.d.). For kinship families that are still active in the labor force, individuals may have lost jobs as a consequence of the COVID-19 related economy shut down. Because the federal government has issued unemployment insurance relief during this crisis, some kinship families could also be eligible for unemployment insurance benefits during COVID-19 (Department of Labor, n.d.).

1.4. Financial assistance and child neglect

Child neglect is positively linked with material hardship (Yang, 2015), and the role of financial assistance has been examined in some studies (e.g.,Lee & Mackey-Bilaver, 2007; Slack et al., 2011). Although the association between financial assistance and child neglect has been mixed (Lee & Mackey-Bilaver, 2007; Slack et al., 2011), increased efforts have been made to provide more financial assistance to low-income families to meet children's basic needs and prevent child maltreatment (Martin & Citrin, 2014).

Several studies have examined the association between the type of financial assistance and the risk of maltreatment. While TANF has the potential to improve family income, and consequently, to increase the family's ability to meet children's basic needs and decrease child neglect risk, most studies have found that receiving TANF did not reduce maltreatment (Latzman et al., 2019; Slack et al., 2011). In fact, Latzman et al. (2019) found that receiving TANF was associated with an increased rate of child maltreatment, and particularly neglect in the subsequent year. A potential reason offered was due to the high correlation between enrollment in TANF and living in poverty.

The SNAP program has been found to both mitigate family food insecurity (Ratcliffe et al., 2011) and also to reduce the risk of child abuse and neglect (Lee & Mackey-Bilaver, 2007). Regarding the association between SNAP and child maltreatment, Lee and Mackey-Bilaver (2007) found that families who received SNAP had fewer reports of child abuse and neglect than families who did not receive it. This finding points out the potential importance of financial assistance in reducing child maltreatment, especially neglect (Drake & Jonson-Reid, 2014; Sedlak et al., 2010). It is believed that receiving financial assistance may decrease parental stress and mental health issues, which are primary risk factors for child maltreatment (Stith et al., 2009). Differently, a recent study found children receiving SNAP were at higher risk for neglect over time compared to those who did not receive SNAP benefits (Morris et al., 2019). The explanation for this counter-intuitive finding was that regions with a higher maltreatment risk are more likely to enroll in the SNAP program (Morris et al., 2019).

To the best of our knowledge, there is a lack of studies regarding the impact of receiving unemployment insurance on child maltreatment. However, the association between job loss and child maltreatment has been examined (Sedlak et al., 2010). One study found that parental job loss during COVID-19 was associated with an increased parenting stress, mental distress, and child abuse risk (Lawson et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2021). Similarly, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have examined the association between foster care payments and kinship guardianship subsidies with neglect risk or child safety in care.

1.5. The present study

In the context of COVID-19, many grandparent-headed kinship families have experienced material hardship (Xu, Wu, Jedwab, & Levkoff, 2020b). But the associations between material hardship, different types of financial assistance and child neglect risk during the pandemic have yet to be explored. Thus, the current study aimed to examine (1) the association between material hardship and child neglect risk, and (2) whether financial assistance, including a combination of all types of financial assistance as well as individual types of financial assistance, moderates this association among grandparent-headed kinship families in the time of COVID-19. Particularly, we examined these associations in three analytic samples: the full sample, a subsample with household income > $30,000, and a subsample with household income ≤ $30,000, respectively. We hypothesized that experiencing material hardship would be positively associated with increased child neglect risk. Given mixed findings in the literature regarding the association between receiving financial assistance and child neglect risk, we had no directional hypothesis for the second research aim.

The results of our study potentially have implications for providing concrete financial assistance to kinship caregivers when they face material hardship, rather than punishing them by removing vulnerable children from home or placing into non-kin foster care. Also, results may shed light on the importance of providing financial assistance outside of the child welfare system to prevent low-income families from entering the child welfare system.

2. Methods

2.1. Data collection

We conducted a cross-sectional online survey among grandparent kinship caregivers (N = 362) via Qualtrics Panels, a research panel that selects participants to take part in survey research (Qualtrics, n.d.-b). The online survey was launched in early June and closed by late June 2020 (about four weeks). Survey participants were recruited by Qualtrics via various sources, including website intercept recruitment, member referrals, targeted email lists, permission-based networks, social media and so on (Qualtrics, n.d.-a). Before we launched the full scale of the survey, we collected pilot data (n = 40) from Qualtrics Panels and made some adjustments after the pilot test. We did not include these 40 participants in our analytic sample. These 362 participants were from 42 states in the U.S., and the most representative states were Colorado (n = 31), Florida (n = 30), California (n = 28), Illinois (n = 27), New York (n = 25), and Washington (n = 25). Caregivers were selected using a convenience sampling strategy. We used five inclusion criteria to select grandparent kinship caregivers in the U.S., including the following: (1) identification as a primary caregiver of one or more grandchildren; (2) did not co-reside with the child's biological parents most of the time; (3) was born before 1985; (4) had at least one grandchild living in the household; and (5) currently lived in the United States. A total of 1908 participants responded to the survey, but only 19% of them met our inclusion criteria. Of note, the majority of these families were not necessarily child welfare involved families. If more than one grandchild lived in the household, respondents were asked to reply based on their oldest grandchild. All participants provided informed consent about study procedures, risks, benefits, and voluntary participation in the survey. Because participants were recruited from different sources, each participant was compensated differently, and the rate was determined by Qualtrics. In general, those who completed surveys were compensated by Qualtrics with a rate of under $14, but the range of incentives varied depending on recruitment sources. Prior to launching the survey, we determined that a sample size of 362 would enable us to have sufficient power to detect a medium to large effect size with 21–26 predictors, at an α of 0.05, with a power of 0.08 as calculated by G*Power (Buchner et al., 1996). This study was determined as exempt for human subjects by the University Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Dependent variable

The dependent variable, child neglect risk, was measured by a 5-item subscale of Conflict Tactics Scales Parent-Child (CTS-PC; Straus et al., 1998). Example items included “I had to leave my child home alone, even when I thought some adult should be with him/her,” and “I was not able to make sure my child got the food he/she needed.” Grandparents were asked about the frequency of these behaviors during the past month. The response options included “never,” “1 time,” “2 times,” “3–5 times,” “6–10 times,” “11–20 times,” “>20 times,” and “not during COVID-19, but it has happened.” The response “not during the pandemic but it happened” was recoded as 0. A summative score of midpoints of the rest of the responses was used to count the total numbers of neglectful behaviors towards grandchildren with higher scores indicating higher child neglect risk (Straus et al., 1998).

2.2.2. Independent variables

The two key independent variables are (1) material hardship and (2) financial assistance. Material hardship was measured by seven dichotomous questions (1 = Yes and 0 = No) from an existing measure, including: grandparents' food insecurity, housing instability, inability to pay the mortgage or rent, disconnected telephone services, disconnected internet services, gas/electricity shut off, and difficulty visiting a doctor during the pandemic (Bendheim-Thoman Center for Research on Child Wellbeing, 2018). We conducted descriptive and bivariate analyses of these seven indicators, and included the summative score, indicating more material hardships, in the regression analyses. The reliability of this variable was 0.74 in this sample.

In terms of financial assistance, we developed a measure that included a combination of multiple possible forms of financial assistance, including foster care payment, kinship guardianship assistance payment, TANF, SNAP, and unemployment insurance. We relied on two ways of measuring financial assistance. If grandparents indicated that they had received any of the 5 types of financial assistance during the last month, this was coded this as 1, with a code of 0 indicating no financial assistance. In addition to using this combined financial assistance variable, we also examined the relationship of individual measures of financial assistance, with 1 indicating receiving the particular type of benefit and 0 indicating not receiving the particular type of benefit.

2.2.3. Covariates

Demographics of grandparents and grandchildren and other covariates were included in the study as potential confounders. The following dummy variables (1 = Yes and 0 = No) were created to indicate the possible trigger events for grandparents becoming primary caregivers: (1) child maltreatment, (2) parental incarceration, (3) mental illness, (4) death, (5) substance abuse, (6) intimate partner violence, (7) economic needs, and (8) other reason. Other reasons included military deployment and parental abandonment. Demographic variables included grandparents' race (1 = Non-Hispanic Black, 2 = Hispanic, 3 = Other, and 0 = Non-Hispanic White), gender (1 = Female and 0 = Male), marital status (1 = Not married and 0 = Married), household income (1 ≥ $ 30,000 and 0 = ≤ $ 30,000), education (1 = Below college and 0 = College and above), number of children in the household (1 = More than one child and 0 = One child), years of care (1 = >1 year and 0 = <1 year or 1 year), licensed caregiver (1 = Yes and 0 = No), and labor force status (1 = Work and 0 = Not work). For the household income variable, we used $30,000 as a cutoff point because $30,000 was a rough estimate for a household with 3–4 household members that would be eligible for SNAP benefits (Department of Agriculture, 2020a). In addition, grandparents' age measured by year and physical health using a 5-point scale (1 = Poor and 5 = Excellent) were identified as confounders.

Other potential confounding variables (e.g., parenting stress, caregivers' mental health, and social support) that may affect parenting behaviors were included. Parenting stress was measured by four items of the Parent Stress Index using a 4-point scale (1 = Strongly disagree and 4 = Strongly agree; Abidin, 1995). Sample items included “I feel trapped by my responsibilities as a grandparent” and “I find that taking care of my grandchild/ren is much more work than pleasure.” This was treated as a continuous variable by taking the average score of these items, with higher scores indicating more grandparenting stress. In this study, the reliability of this scale was 0.85. The Mental Health Inventory-5 (MHI-5; Stewart et al., 1988) was used to measure mental health of grandparents. Examples of these questions included, “how much of the time during the last month have you (1) been a very nervous person?; (2) felt downhearted and blue?; (3) felt calm and peaceful?; (4) felt so down in the dumps that nothing could cheer you up?; and (5) been a happy person?” with 1 = None of the time and 6 = All of the time. A continuous variable was used with higher scores indicating better mental health. The reliability of this scale was 0.59 in this sample, although it has reliability (α = 0.78) in other studies (Trainor et al., 2013). Social support was measured by eight questions with a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = I get much less than I would like and 5 = I get as much as I like) using the Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire (Broadhead et al., 1989). To determine whether grandparents received high social support, a cutoff score of 4 or 80% (4/5) of the total theoretical range was used (1 = High social support if ≥4 and 0 = Low social support if <4). We further controlled for the grandchild's age (continuous variable), grandchild's gender (1 = Female and 0 = Male), and grandchild's physical and mental health (1 = Poor and 5 = Excellent).

2.3. Data analysis

Descriptive, bivariate (i.e., t-tests and chi-square tests), and negative binominal analyses were conducted using STATA 15 (StataCorp, 2017). We ran these models in three samples: (1) the full sample (n = 362), (2) a subsample with families' household income ≤ $ 30,000 (n = 106), and (3) a subsample with families' household income > $ 30,000 (n = 256). To understand the moderating effect of financial assistance on the association between material hardship and child neglect risk, an interaction between material hardship and financial assistance was added into regression models. To examine the moderating effects of each type of financial assistance on this association, we further included five interaction terms (Material hardship × foster care payment; material hardship × kinship guardianship; material hardship × TANF; material hardship × SNAP; material hardship × unemployment insurance) into models. Only models with significant key variables of interest were reported in the results and tables. Missing data ranged from 0.28% to 1.66%.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive and bivariate results

Descriptive and bivariate results are presented in Table 1 . The top three trigger events for grandparents caring for grandchildren in this study were due to parental economic needs (33.7%), parental substance abuse (17.1%), and parental death (9.4%). Most of the grandparents were White (n = 246; 68.7%), female (n = 226; 62.4%), married (n = 252; 69.6%), had received an education below college (n = 218; 60.2%), with a mean age of 57 years (SD = 7.75). On average, grandparents reported that the total number of neglectful behaviors towards grandchildren occurred eight times (M = 8.05, SD = 19.39) since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Among the seven possible material hardships, participating households experienced on average 1.62 (SD = 1.82) types of material hardships during the COVID-19 pandemic. The most prevalent material hardship grandparents experienced was medical hardship (36.2%), followed by mortgage/rent hardship (28.2%), and disconnected internet services (21.6%).

Table 1.

Descriptive and bivariate results.

| Full sample (N = 362) |

Subsample: Household income ≤ 30,000 (N = 106) |

Subsample: Household income > 30,000 (N = 256) |

χ 2 /t-test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | %/Mean (SD) | N | %/Mean (SD) | N | %/Mean (SD) | ||

| Key variables | |||||||

| Child neglect risk | 362 | 8.05 (19.39) | 106 | 5.76 (14.38) | 256 | 8.99 (21.08) | −1.44 |

| Material hardship | 362 | 1.62 (1.82) | 106 | 1.58 (1.85) | 256 | 1.63 (1.81) | −0.27 |

| Mortgage/rent hardship | |||||||

| Yes | 102 | 28.18% | 32 | 30.19% | 70 | 27.34% | 0.30 |

| No | 260 | 71.0.82% | 74 | 69.81% | 186 | 72.66% | |

| Gas/electricity shut off | |||||||

| Yes | 64 | 17.68% | 19 | 17.92% | 45 | 17.58% | 0.01 |

| No | 298 | 82.32% | 87 | 82.08% | 211 | 82.42% | |

| Disconnected telephone services | |||||||

| Yes | 73 | 20.17% | 18 | 16.98% | 55 | 21.48% | 0.94 |

| No | 289 | 79.83% | 88 | 83.02% | 201 | 78.52% | |

| Disconnected internet services | |||||||

| Yes | 78 | 21.55% | 26 | 24.53% | 52 | 20.31% | 0.79 |

| No | 284 | 78.45% | 80 | 75.47% | 204 | 79.69% | |

| Medical hardship | |||||||

| Yes | 131 | 36.19% | 35 | 33.02% | 96 | 37.50% | 0.65 |

| No | 231 | 63.81% | 71 | 66.98% | 160 | 62.50% | |

| Food insecurity | |||||||

| Yes | 75 | 20.72% | 23 | 21.70% | 52 | 20.31% | 0.09 |

| No | 287 | 79.28% | 83 | 78.30% | 204 | 79.69% | |

| Housing instability | |||||||

| Yes | 62 | 17.13% | 14 | 13.21% | 48 | 18.75% | 1.62 |

| No | 300 | 82.87% | 92 | 86.79% | 208 | 81.25% | |

| A combination of all financial assistance | 361 | ||||||

| Yes | 245 | 67.87% | 88 | 83.81% | 157 | 61.33% | 17.26⁎⁎⁎ |

| No | 116 | 32.13% | 17 | 16.19% | 99 | 38.67% | |

| Foster care payment | |||||||

| Yes | 77 | 21.33% | 25 | 23.81% | 52 | 20.31% | 0.54 |

| No | 284 | 78.67% | 80 | 76.19% | 204 | 76.69% | |

| Kinship guardianship | |||||||

| Yes | 82 | 22.65% | 23 | 21.70% | 59 | 23.05% | 0.08 |

| No | 280 | 77.35% | 83 | 78.30% | 197 | 76.95% | |

| TANF | |||||||

| Yes | 116 | 32.04% | 38 | 35.85% | 78 | 30.47% | 1.00 |

| No | 246 | 67.96% | 68 | 64.15% | 178 | 69.53% | |

| SNAP | |||||||

| Yes | 161 | 44.48% | 68 | 64.15% | 93 | 36.33% | 23.50⁎⁎⁎ |

| No | 201 | 55.52% | 38 | 35.85% | 163 | 63.67% | |

| Unemployment insurance | |||||||

| Yes | 88 | 24.38% | 25 | 23.58% | 63 | 24.71% | 0.05 |

| No | 273 | 75.62% | 81 | 76.42% | 192 | 75.29% | |

| Covariates | |||||||

| Trigger event | 11.85 | ||||||

| Child abuse and neglect | 26 | 7.18% | 8 | 7.55% | 18 | 7.03% | |

| Parental incarceration | 18 | 4.97% | 7 | 6.60% | 11 | 4.30% | |

| Parental mental illness | 29 | 8.01% | 12 | 11.32% | 17 | 6.64% | |

| Parental death | 34 | 9.39% | 14 | 13.21% | 20 | 7.81% | |

| Parental substance abuse | 62 | 17.13% | 12 | 11.32% | 50 | 19.53% | |

| Parental intimate partner violence | 20 | 5.52% | 4 | 3.77% | 16 | 6.25% | |

| Parental economic needs | 122 | 33.70% | 30 | 28.30% | 92 | 35.94% | |

| Other | 51 | 14.09% | 19 | 17.92% | 32 | 12.50% | |

| Grandparent race | 2.04 | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 246 | 68.72% | 69 | 65.09% | 177 | 70.24% | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 34 | 9.50% | 12 | 11.32% | 22 | 8.73% | |

| Hispanic | 72 | 20.11% | 22 | 20.75% | 50 | 19.84% | |

| Other | 6 | 1.68% | 3 | 2.83% | 3 | 1.19% | |

| Grandparent gender | 2.65 | ||||||

| Male | 136 | 37.57% | 33 | 103 | |||

| Female | 226 | 62.43% | 73 | 153 | |||

| Grandparent age | 362 | 56.5 (7.75) | 106 | 56.92 (7.43) | 256 | 56.33 (7.88) | 0.66 |

| Grandparent marital status | 35.69⁎⁎⁎ | ||||||

| Married | 252 | 69.61% | 50 | 47.17% | 202 | 78.91% | |

| Other | 110 | 30.39% | 56 | 52.83% | 54 | 21.09% | |

| Grandparent household income | |||||||

| ≤$ 30,000 | 103 | 29.28% | – | – | – | – | – |

| >$ 30,000 | 256 | 70.72% | – | – | – | – | – |

| Grandparent education | |||||||

| Below college | 218 | 60.22% | 81 | 76.42% | 137 | 53.52% | 16.41⁎⁎⁎ |

| College and above | 144 | 39.78% | 25 | 23.58% | 119 | 46.48% | |

| Grandparent physical health | 361 | 3.48 (1.01) | 105 | 3.23 (1.17) | 256 | 3.58 (1.02) | −2.86⁎⁎ |

| Number of children in the household | |||||||

| One child | 64 | 17.68% | 55 | 51.89% | 136 | 53.13% | 0.05 |

| More than one child | 298 | 82.32% | 51 | 48.11% | 120 | 46.88% | |

| Years of care | |||||||

| One year or less than one year | 77 | 19.15% | 22 | 20.75% | 42 | 16.41% | 0.97 |

| More than one year | 325 | 80.85% | 84 | 79.25% | 214 | 83.59% | |

| Licensed kinship caregivers | |||||||

| Yes | 143 | 39.61% | 41 | 38.68% | 102 | 40.00% | 0.05 |

| No | 218 | 60.39% | 65 | 61.32% | 153 | 60.00% | |

| Labor force status | |||||||

| Work | 240 | 66.30% | 51 | 49.04% | 189 | 75% | 22.59⁎⁎⁎ |

| Don't work | 122 | 33.70% | 53 | 50.96% | 63 | 25% | |

| Parenting stress | 362 | 2.30 (0.82) | 106 | 2.28 (0.86) | 256 | 2.30 (0.82) | −0.21 |

| Mental health | 362 | 3.97 (1.01) | 106 | 3.97 (1.00) | 256 | 3.97 (1.01) | 0.05 |

| Social support | |||||||

| High | 130 | 35.91% | 38 | 35.85% | 92 | 35.94% | 0.01 |

| Low | 232 | 64.09% | 68 | 64.15% | 164 | 64.06% | |

| Child age | 358 | 9.53 (4.68) | 105 | 9.47 (4.54) | 253 | 9.55 (4.74) | −0.16 |

| Child gender | 5.10⁎ | ||||||

| Male | 195 | 54.02% | 67 | 63.21% | 128 | 50.20% | |

| Female | 166 | 45.98% | 39 | 36.79% | 127 | 49.80% | |

| Child physical health | 362 | 4.45 (0.74) | 106 | 4.30 (0.83) | 256 | 4.51 (0.70) | −2.46⁎ |

| Child mental health | 362 | 4.25 (0.96) | 106 | 4.10 (1.15) | 256 | 4.31 (0.86) | −1.86 |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Significant differences regarding marital status (χ2 = 35.69, p < 0.001), education (χ2 = 16.41, p < 0.001) and labor force status (χ2 = 22.59, p < 0.001) were found between families with a household income of $30,000 or less (n = 106; 29.3%) and household income of more than $30,000 (n = 256; 70.7%). Grandparents with a household income above $30,000 had significantly better physical health conditions (3.58 out of 5) compared to caregivers with a household income of $30,000 or below (3.23 out of 5; t = −2.86, p < 0.01).

Moreover, children residing in a household with an income of $30,000 or more on average had significantly better physical health (4.51 on a 5-point scale) than their counterparts (4.30 out of 5; t = −2.46, p < 0.05); however, there was no significant difference in child mental health. Most children residing in a household with an income of $30,000 or below were male (63.2%) compared to those residing in a household with an income above $30,000 (male: 50.20%; χ2 = 5.10, p < 0.05). In addition, results show that grandparents experienced a mean of 2.30 (SD = 0.82) out of 4 and 3.97 (SD = 1.01) out of 6 on scales of parenting stress and mental distress, respectively. These numbers indicate moderate levels of parenting stress and mental distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Approximately 36% of kinship grandparents received high social support.

In the full sample (n = 362), most grandparents had received at least one type of financial assistance (67.9%), which varied by household income (χ 2 = 17.26, p < 0.001). As expected, the majority (83.8%) of those with a household income ≤ $30,000 received at least one financial assistance compared to those (61.3%) with a household income > $30,000. Only a small proportion of grandparents received TANF (32.04%), foster care payment (21.3%), kinship guardianship (22.7%), or unemployment insurance (24.4%), while about half of them received SNAP benefits (44.5%). Most grandparents with a household income ≤ $30,000 significantly received more SNAP benefits (64.2%) compared to those with a household income > $30,000 (36.3%; χ2 = 23.50, p < 0.001).

3.2. Negative binomial regression results

3.2.1. Main effects of material hardship and financial assistance on child neglect risk

Table 2 shows regression models predicting child neglect risk in the full sample, the subsample with household income ≤ $ 30,000 and the subsample with household income > $ 30,000, respectively. The first model regressed child neglect risk on material hardship and a combination of all financial assistance, controlling for other covariates. The results of Model 1 show that material hardship (b = 0.31, p < 0.001) was associated with an increased child neglect risk, while receiving any financial assistance (b = −0.88, p < 0.05) was associated with a lower child neglect risk. This indicates that the combination of all financial assistance was protective against child neglect risk in the full sample. Other significant covariates associated with child neglect risk included all parental trigger events except for parental death, being a licensed kinship caregiver (b = 2.04, p < 0.001), high parenting stress (b = 0.94, p < 0.001), better caregiver's mental health (b = −0.48, p < 0.05), high social support (b = −0.99, p < 0.01), and child's age (b = −0.12, p < 0.01). Similar results were found in Model 8 for the subsample of grandparents with household income > $30,000. Both material hardship (b = 0.33, p < 0.05) and a combination of all financial assistance (b = −1.31, p < 0.05) were significantly associated with child neglect risk. Some trigger events were negatively correlated with child neglect risk, such as parental incarceration (b = −3.75, p < 0.01), parental substance abuse (b = −2.21, p < 0.01), and parental intimate partner violence (b = −2.77, p < 0.01). In the subsample of kinship families with household income ≤ $ 30,000/year (Model 5), material hardship and any financial assistance were not significantly associated with child neglect risk, but the directions of associations were the same as in Models 1 and 8.

Table 2.

Negative binomial regression results.

| Full sample (N = 362) |

Subsample: Household income ≤ 30,000 (N = 106) |

Subsample: Household income > 30,000 (N = 256) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: A combination of financial assistance |

Model 2: Financial assistance as a moderator |

Model 3: Different types of financial assistance |

Model 4: SNAP as a moderator |

Model 5: A combination of financial assistance |

Model 6: Financial assistance as a moderator |

Model 7: Different types of financial assistance |

Model 8: A combination of financial assistance |

Model 9: Financial assistance as a moderator |

Model 10: Different types of financial assistance |

|

| b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | |

| Key variables | ||||||||||

| Material hardship | 0.31⁎⁎ | 0.91⁎ | 0.31⁎ | 0.53⁎⁎ | 0.12 | 1.79⁎ | 0.70⁎⁎⁎ | 0.33⁎ | 0.99⁎⁎ | 0.43⁎ |

| A combination of all financial assistance | −0.88⁎ | −0.36 | – | – | −1.07 | −0.28 | – | −1.31⁎ | −0.63 | – |

| Foster care payment | – | – | −0.49 | −0.73 | – | – | −2.66⁎⁎⁎ | – | – | −0.23 |

| Kinship guardianship | – | – | −0.48 | −0.39 | – | – | −0.27 | – | – | −0.90 |

| TANF | – | – | 0.64 | 0.53 | – | – | 2.73⁎⁎⁎ | – | – | −0.10 |

| SNAP | – | – | −0.77⁎ | 0.10 | – | – | −1.53⁎⁎⁎ | – | – | −0.89⁎ |

| Unemployment insurance | – | – | 0.28 | 0.41 | – | – | 0.55⁎ | – | – | −0.26 |

| Material hardship × Financial assistance | −0.72⁎ | – | – | – | −1.70⁎ | – | – | −0.81⁎ | – | |

| Material hardship × SNAP | – | – | – | −0.42⁎ | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Control variables | ||||||||||

| Trigger event (Ref. child maltreatment) | ||||||||||

| Parental incarceration | −1.88⁎ | −2.19⁎⁎ | −2.22⁎ | −2.28⁎ | −2.23 | −1.42 | −3.51⁎⁎⁎ | −3.75⁎⁎ | −3.93⁎⁎ | −3.34⁎⁎ |

| Parental mental illness | −2.04⁎⁎ | −2.15⁎⁎ | −2.02⁎⁎ | −2.28⁎⁎ | −1.55 | −0.78 | −1.21 | −1.43 | −1.71 | −0.48 |

| Parental death | −1.11 | −1.23 | −0.80 | −1.06 | −3.19⁎ | −2.28 | −1.36 | −0.51 | −0.90 | −0.25 |

| Parental substance abuse | −2.15⁎⁎ | −2.23⁎⁎⁎ | −2.40⁎⁎⁎ | −2.39⁎⁎⁎ | −3.48⁎⁎ | −2.24⁎ | −3.37⁎⁎⁎ | −2.21⁎⁎ | −2.57⁎⁎ | −2.11⁎⁎ |

| Parental intimate partner violence | −2.35⁎⁎ | −2.44⁎⁎ | −2.18⁎⁎ | −2.08⁎⁎ | −0.64 | 0.53 | 0.79 | −2.77⁎⁎ | −3.06⁎⁎ | −2.33⁎ |

| Parental economic needs | −1.24⁎ | −1.58⁎⁎ | −0.97 | −0.97 | −0.60 | 0.02 | −0.51 | −1.30 | −1.90⁎ | −0.86 |

| Other | −1.87⁎ | −1.88⁎⁎ | −1.56⁎ | −1.56⁎ | −1.53 | −0.98 | −1.43 | −2.36⁎ | −2.52⁎⁎ | −1.95⁎ |

| Grandparent race/ethnicity (ref. White, non-Hispanic) | ||||||||||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 0.29 | 0.48 | −0.01 | −0.43 | −17.53 | −18.89 | −25.98 | 0.98 | 1.27 | 0.33 |

| Hispanic | −0.13 | 0.08 | −0.09 | 0.02 | −0.44 | −0.16 | −1.35⁎⁎⁎ | −0.21 | −0.05 | −0.33 |

| Other | 0.80 | −0.69 | −0.30 | −0.13 | 1.25 | 1.64 | 4.56⁎⁎⁎ | −21.14 | −20.16 | −17.31 |

| Grandparent gender: Female (Ref. Male) | −0.12 | −0.12 | 0.05 | −0.08 | −1.42 | −1.08 | 0.43 | −0.13 | −0.08 | 0.01 |

| Grandparent age | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.24 |

| Grandparent marital status (Ref. Married) | −0.11 | −0.08 | 1.21 | 0.09 | −0.58 | −1.22 | −1.23⁎ | −0.12 | −0.07 | −0.24 |

| Grandparent household income in 2019 > 30,000 (Ref. ≤30,000) | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.42 | 0.39 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Grandparent education: Below college (ref. College and above) | −0.44 | −0.19 | −0.56 | −0.66 | 1.25 | 1.40⁎ | 0.18 | −0.51 | −0.29 | −0.57 |

| Grandparent physical health | 0.03 | 0.13 | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.38 | −0.38 | −0.44⁎ | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.21 |

| Number of children in the household: More than one child (ref. One child) | −0.35 | −0.31 | −0.36 | −0.39 | 0.49 | 0.58 | 0.47 | −0.83 | −0.80 | −0.72 |

| Years of care: More than one year (ref. ≤1 year) | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.59 | 0.81 | 0.58 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.24 |

| Licensed kinship caregivers | 2.04⁎⁎⁎ | 2.25⁎⁎⁎ | 1.95⁎⁎⁎ | 2.08⁎⁎⁎ | 3.13⁎⁎⁎ | 3.13⁎⁎⁎ | 3.36⁎⁎⁎ | 1.62⁎⁎ | 1.98⁎⁎⁎ | 1.90⁎⁎ |

| Labor force status (ref. don't work) | −0.21 | −0.27 | −0.39 | −0.44 | 0.05 | −0.10 | −1.72⁎⁎ | 0.08 | −0.11 | 0.07 |

| Parenting stress | 0.94⁎⁎⁎ | 0.94⁎⁎⁎ | 1.16⁎⁎⁎ | 1.26⁎⁎⁎ | 1.01⁎ | 0.87⁎ | 1.67⁎⁎⁎ | 0.88⁎⁎ | −0.82 | 1.09⁎⁎⁎ |

| Mental health | −0.48⁎ | −0.41 | −0.46⁎ | −0.52⁎ | 0.06 | 0.40 | 0.03 | −0.96⁎⁎ | 0.91⁎⁎ | −0.95⁎⁎ |

| Social support: High (ref. low) | −0.99⁎⁎ | −1.04⁎⁎ | −0.87⁎ | −0.64 | −2.14⁎⁎ | −2.20⁎⁎⁎ | −1.80⁎⁎⁎ | −0.79 | −0.89⁎⁎ | −0.57 |

| Child age | −0.12⁎⁎ | −0.12⁎⁎ | −0.13⁎⁎ | −0.12⁎⁎ | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.17⁎⁎ | −0.17⁎⁎ | −0.17⁎⁎ |

| Child gender (ref. Male) | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.35 | 0.84 | 0.58 | 0.11 | −0.38 | −0.42 | −0.48 |

| Child physical health | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.15 | −0.31 | −0.27 | −0.53⁎ | −0.21 | −0.08 | −0.20 |

| Child mental health | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.01 | −0.05 | −0.07 | 0.05 | 0.06 | −0.01 | −0.10 |

b = unstandardized coefficients; interactions between each type of financial assistance and material hardship were not significant in two subsamples (Household income ≤ 30,000 and Household income > 30,000); thus, results were not reported.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

3.2.2. Interaction between material hardship and financial assistance

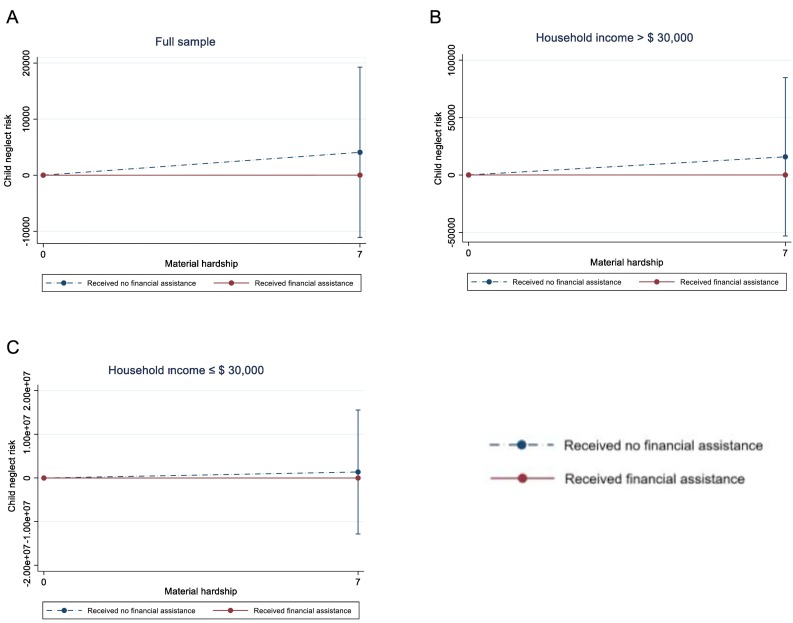

Model 2 and Fig. 1 a show that any financial assistance was a moderator between material hardship and child neglect risk in the full sample (b = −0.72, p < 0.05) as well as in each of the disaggregated samples (Model 6: b = −1.70, p < 0.05; Model 9: b = −0.81, p < 0.05; see Fig. 1b and c). These data indicate that receiving any financial assistance buffered the negative effects of material hardship on child neglect risk, controlling for covariates.

Fig. 1.

Financial assistance moderates the relationship between material hardship and child neglect risk in the full sample, the subsample with household income > $ 30,000, and the subsample with household income ≤ $ 30,000 a. Financial assistance moderates the relationship between material hardship and child neglect risk in the full sample b. Financial assistance moderates the relationship between material hardship and child neglect risk in the subsample with household income > $ 30,000 c. Financial assistance moderates the relationship between material hardship and child neglect risk in the subsample with household income ≤ $ 30,000.

3.2.3. Main effects of each type of financial assistance on child neglect risk

Model 3 presents the association between different types of financial assistance on child neglect risk without interactions. Interestingly, only SNAP was found to be protective against child neglect risk in both the full sample (Model 3: b = −0.77, p < 0.05) as well as the two subsamples (Model 7: b = −1.53, p < 0.001; Model 10: B = −0.89, p < 0.05). In Model 7, receiving foster care payment (b = −2.66, p < 0.001) was associated with lower child neglect risk among families with household income ≤ $ 30,000/year. However, receiving TANF (b = 2.73, p < 0.001) and unemployment insurance (b = 0.55, p < 0.05) were associated with higher levels of child neglect risk in Model 7.

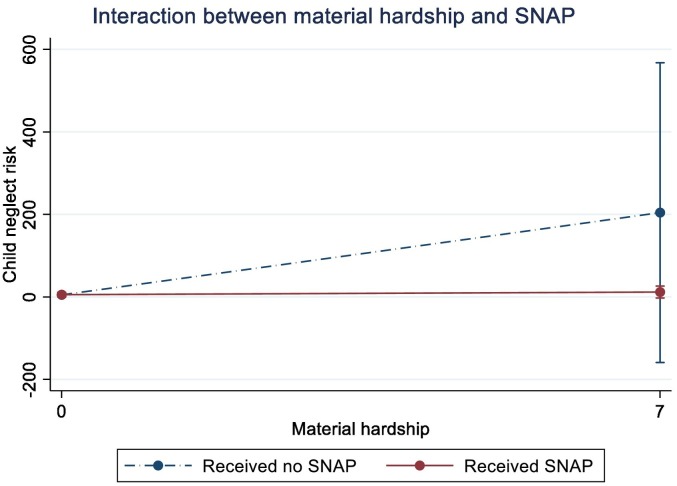

3.2.4. Interaction between material hardship and SNAP

In Model 4, only the interaction between material hardship and SNAP benefits was significant. SNAP buffered the negative effect of material hardship on child neglect risk (b = −0.42, p < 0.05; Model 4 and Fig. 2 ) in the full sample; however, interactions between each type of financial assistance and material hardship were not significant in the two subsamples (Household income ≤ 30,000 and Household income > 30,000). Thus, we did not present the results in Table 2.

Fig. 2.

SNAP moderates the relationship between material hardship and child neglect risk in the full sample.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we examined the association between material hardship and child neglect risk and further tested the moderating role of financial assistance on this association among grandparent-headed kinship families in the time of COVID-19. We used two measures of financial assistance as predictor variables, a combination of all types of financial assistance, as well as individual types of financial assistance in the full sample, the sample with household income ≤ $30,000/year, and the sample with household income > $30,000/year, respectively. Results partially support research hypotheses. Material hardship was positively associated with an increased child neglect risk, and receiving any type of financial assistance was protective against child neglect in both the full sample and the subsample with household income > $30,000/year. Regarding the moderating role of financial assistance on this association, results indicate that receiving a combination of financial assistance buffers the negative effects of material hardship on child neglect across all three analytic samples. Regarding the effects of a specific type of financial assistance, SNAP has a significant buffering effect on the association between material hardship and child neglect in the full sample only. In terms of other types of financial assistance among grandparent-headed kinship families with household income ≤ $ 30,000/year, receiving TANF and unemployment insurance is associated with an increased child neglect risk, while receiving foster care payments and SNAP is associated with a decreased risk of child neglect risk.

The results confirming the positive association between material hardship and child neglect risk among grandparent kinship caregivers in the full sample and the subsample with household income > $ 30,000/year are aligned with findings in biological parent-headed households (Slack et al., 2011; Yang, 2015). Surprisingly, this association is not significant in the subsample with household income ≤ $ 30,000/year. A potential explanation is that material hardship is not a significant contributor to child neglect if families are at the low-income level, where other factors, such as parenting stress and low social support, may be more important factors contributing to child neglect (Maguire-Jack & Wang, 2016; Xu, Wu, Jedwab, & Levkoff, 2020b). These results suggest that only addressing material needs is not enough to prevent child neglect, particularly among low-income grandparent-headed families. More efforts should be provided to meet grandparents' parenting and psychological needs and improve families' social support at the family and community levels.

Additionally, our findings suggest that we should tackle child neglect by addressing the material needs of grandparent-headed kinship families via the provision of concrete financial assistance. Of note, our results indicate that not all types of financial assistance have the same associations with the outcome. Only certain types of financial assistance (e.g., SNAP, foster care payment) may have protective associations with reducing child neglect risk. Similar to a previous study (Lee & Mackey-Bilaver, 2007), our results confirm that SNAP is associated with decreased child neglect risk. But the effect of SNAP on child neglect is inconclusive across the literature. Some prior studies indicate that receiving SNAP increases child neglect risk (Morris et al., 2019). This apparent increased risk might be due to the fact that families living in counties with a higher child maltreatment risk are more likely to receive SNAP (Morris et al., 2019).

Among households with an income ≤ $30,000/year, we further found receiving foster care payments was associated with decreased child neglect risk. While no previous studies have examined the association between foster care payments and child safety outcomes, Xu, Bright, et al. (2020a) found that only about 53% of kinship families involved in the child welfare system receive foster care payments in the United States. Becoming licensed kinship foster parents is a premise for receiving foster care payments, which is not applicable to many unlicensed kinship caregivers (Berrick & Boyd, 2016). Thus, our current finding on the protective effects of foster care payments highlights the importance of expanding foster care payments to kinship caregivers by lessening kinship licensing criteria and providing more financial supports to kinship caregivers.

Our results also suggest that receiving TANF is associated with increased child neglect risk in household income ≤ $30,000, which is aligned with Slack et al. (2011) findings. Families who received TANF may have poor parenting skills and worse mental health, which may further contribute to child neglect risk (Slack et al., 2011). We should note that this does not imply that receiving TANF leads to child neglect but more likely indicates that families who are eligible for TANF are also at a high risk of experiencing poverty (Xu, Bright, et al., 2020a), and poverty is associated with increased child neglect risk (Kobulsky et al., 2019). More research is needed to explore the potential role of TANF in preventing child neglect. Furthermore, we found that receiving unemployment insurance was associated with an increased risk for child neglect in the subsample where kinship families had an annual household income ≤ $ 30,000. But this association was not significant among households with an annual income > $30,000/year. Among caregivers with household > $30,000/year, 24% of them received unemployment insurance, and there were no significant differences compared to the sample with a household income ≤ $ 30,000/year. It is possible that the loss of a job among more affluent families might not immediately increase parenting stress or mental distress or affect parenting behaviors as these families might have savings to survive for a few months without employment. Another possible explanation is that positive parental perceptions towards job loss may decrease parental stress and mitigate child maltreatment risk (Lawson et al., 2020; Wu & Xu, 2020).

In addition to material hardship and financial assistance and their association with child neglect risk, some other variables increased the likelihood of neglect. We found that high parenting stress, caregivers' mental health, and low social support significantly contributed to child neglect risk in grandparent-headed kinship families. These findings are aligned with previous studies conducted among biological families (Lee et al., 2012; Maguire-Jack & Wang, 2016). Our results revealed that for caregivers who stepped up to care for children in kinship care due to child welfare involvement, child neglect risk was higher. This may indicate the high likelihood of intergenerational transmission of risky parenting styles (Madigan et al., 2019). This suggests that a child's biological parents' harsh, aggressive, and/or neglectful parenting behaviors may be transmitted from grandparents' similar parenting style via some pathways, such as the parent's mental distress (Morelli et al., 2020). In terms of other significant predictors, we found that children living in households with licensed kinship caregivers were at a higher risk of neglect, and this might be because licensed kinship families were more economically vulnerable. It is also important to note that some factors unmeasured in this study may also increase child neglect risk, such as children's disabilities, lack of access to mental health and therapeutic services for children and caregivers, and caregivers' alcohol use (Musser et al., 2021).

4.1. Strengths and limitations

This study is one of the first to examine financial assistance in decreasing child neglect risk among grandparent-headed kinship families in the face of COVID-19. Particularly, this study fills gaps in the literature by examining both the effects of any financial assistance as well as the effect of individual types of economic supports on mitigating child neglect risk in kinship families. Despite the strengths of this study, several limitations are worth noting. First, the generalizability of this study is limited, which is related to the use of convenience sampling methods. For instance, grandparents without access to the internet might not have participated in this study. Relatedly, there was dependence in error terms due to convenience sampling methods, and potential bias may exist in estimates and inferences of our significant tests. Thus, interpreting these findings should be made with caution. Second, this survey data was collected across the country, and each state might have different policies and amounts of financial assistance provided to kinship families, particularly foster care payments and kinship guardianship subsidies. However, we did not control for these differences. Third, we did not collect information about these families' financial assistance status prior to COVID-19, and thus, we do not know if there was any change in the rate of assistance during the COVID period or what was the length of time for which they received financial assistance. Furthermore, some kinds of financial assistance were not included in this survey, such as grandparents' social security benefits and child support benefits. Additionally, subsample analyses with the 106 kinship caregivers were underpowered statistically. Lastly, this study was limited by its cross-sectional design, which limits the possibility of making a causal inference on the effect of financial assistance on child neglect risk. The directionality of associations cannot be inferred in the current study.

4.2. Implications for future research

These limitations point to certain directions for future studies. First, future research could quantify both the amount of financial assistance and the length of financial assistance to better understand its impact on neglect and other types of maltreatment. In addition, longitudinal tracking of kinship families' material hardship and financial assistance over time would provide a deeper and much needed understanding of the impact of these programs on child neglect risk. Second, future research should examine the effects of different types of financial assistance on comprehensive indicators of the well-being of children, including educational, physical, and mental health outcomes. As this study was conducted amid the pandemic, it would also be beneficial to understand the effects of financial assistance on kinship families post pandemic. Last but not least, conducting qualitative research could gain a deeper understanding of both caregiver and the child needs, and the role of financial assistance in grandparent-headed kinship families.

4.3. Implications for practice

Our results suggest the importance of concrete financial assistance, particularly SNAP and foster care payments in reducing child neglect risk, to grandparent kinship caregivers in the context of COVID-19. Many kinship families are eligible for financial assistance but not receiving benefits due to a lack of knowledge about their eligibility or burdensome and inaccessible application processes (Department of Agriculture, n.d.; Murray, Ehrle, Geen, 2004). The protective role of foster care payments highlights the necessity to expand foster care payments to kinship families.

Moreover, our results indicate that SNAP mitigates child neglect risk, but some grandparent kinship caregivers are not eligible to receive SNAP due to a lack of child custody (Llobrera, 2020). In addition to this, grandparents faced other challenges such as lack of transportation, long waiting time, complicated application forms, limited mobility and other issues, many associated with aging, in applying for financial assistance (Department of Agriculture, n.d.). Although the federal and state governments have loosened financial assistance criteria, expanded the length of financial assistance, and simplified the application process during COVID-19, there are still substantial barriers for accessing and making full use of financial assistance. In terms of SNAP during COVID-19, states are allowed to issue pandemic electronic meal replacement benefits (P-EBT) for households with children eligible to receive free or reduced-price school meals with $114 per child a month (Rosenbaum et al., 2020). For states with available online purchasing, grandparent-headed kinship families may not know how to use online food purchasing platforms due to low digital literacy, which further increases barriers to access affordable food. Therefore, providing user-friendly instructions or technical assistance might be beneficial to these families. Moreover, food hardship among children and their families remained high even after P-EBT benefits were issued (Kinsey et al., 2020). This shows the severity of food insecurity and that extending P-EBT alone is not enough. Thus, understanding and eliminating barriers for kinship caregivers receiving financial assistance during and post COVID-19 is important.

Our findings also call for changes to improve grandparent kinship caregivers' accessibility to concrete financial assistance. It is important to provide financial resources to families outside of child welfare systems, as grandparent heated kinship families might prefer to abstain from financial assistance, if it means they are required to involve the child welfare system. To screen material hardship during and post the pandemic, developing and implementing clinical screening tools could be helpful. Fallon et al. (2020) developed a clinical tool to screen risk factors for child maltreatment during the pandemic in Canada. This tool includes 12 dichotomous questions asking families' material hardship (utilities, food, housing, medication), families' physical and mental health concerns, and access to social support (Fallon et al., 2020). This tool may be feasible to implement widely, including for grandparent-headed kinship families with some adaptation during and post the pandemic. Meanwhile, training social workers, mental health professionals, teachers, and pediatricians on how to screen for family material hardship and how to connect caregivers to essential financial assistance to meet their material needs is necessary. Providing these professionals with sufficient understanding of eligibility and procedures to apply for financial assistance will further help caregivers be aware of economic support services available and how to navigate the application process. Also, financial support services should go beyond food, and include clothing, utilities, furniture, diapers, emergency cash, transportation (Conrad et al., 2020). As research indicates that specific financial assistance improves certain outcomes more than others (Conrad et al., 2020), child welfare workers may consider providing target and tailored financial assistance to families accordingly. In addition to providing services to meet families' material needs, it is of importance to provide a comprehensive service package to support kinship families. The service package should include tailored financial assistance services with additional parenting training, mental health services, and services strengthening social support. In summary, broadening the safety net to increase financial stability and building kinship family capability, including financial capability, along with providing other family-centered services, will benefit children and grandparent caregivers in kinship care during and post COVID-19. Last but not least, as children in kinship care experience various types of trauma (e.g., maltreatment, household dysfunction, removal from home, living in poverty), it is vital to integrate trauma-informed care in the financial assistance system for kinship families.

Funding

This work was supported by the University of South Carolina College of Social Work.

References

- Abidin R.R. Psychological Assessment Resources; 1995. Parenting stress index. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn H., DePanfilis D., Frick K., Barth R.P. Estimating minimum adequate foster care costs for children in the United States. Children and Youth Services Review. 2018;84:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.10.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S.G. The impact of state TANF policy decisions on kinship care providers. Child Welfare. 2006;85(4):715–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker L.A., Mutchler J.E. Poverty and material hardship in grandparent-headed households. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72(4):947–962. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00741.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavier R. Children residing with no parent present. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33(10):1891–1901. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.05.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bendheim-Thoman Center for Research on Child Wellbeing 9.4. Scale material hardship. 2018. https://fragilefamilies.princeton.edu/sites/fragilefamilies/files/year_1_guide.pdf#page=22

- Berger L.M. Socioeconomic factors and substandard parenting. Social Service Review. 2007;81(3):485–522. doi: 10.1086/520963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berrick J.D., Boyd R. Financial well-being in family-based foster care: Exploring variation in income supports for kin and non-kin caregivers in California. Children and Youth Services Review. 2016;69:166–173. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.08.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. We’re not all in this together: On COVID-19, intersectionality, and structural inequality. American Journal of Public Health. 2020;110(7):e1–917. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead W.E., Gehlbach S.H., DeGruy F.V., Kaplan B.H. Functional versus structural social support and health care utilization in a family medicine outpatient practice. Medical Care. 1989:221–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchner A., Erdfelder E., Faul F. In: Handbuch quantitative methoden. Erdfelder E., Mausfeld R., Meiser T., Rudinger G., editors. Psychologie Verlags Union; Weinheim, Germany: 1996. Teststärkeanalysen [power analyses] pp. 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Burek M.W. AFDC to TANF: The effects of welfare reform on instrumental and expressive crimes. Criminal Justice Studies. 2006;19(3):241–256. doi: 10.1080/14786010600764542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cancian M., Yang M.Y., Slack K.S. The effect of additional child support income on the risk of child maltreatment. Social Service Review. 2013;87(3):417–437. doi: 10.1086/671929. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Children'’s Bureau Title IV-E guardianship assistance. 2013. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/grant-funding/title-iv-e-guardianship-assistance#:~:text=The%20title%20IV%2DE%20Guardianship,guardianship%20of%20eligible%20children%20for Retrieved from.

- Children'’s Defense Fund Financial assistance for grandparents and other relatives raising children. 2004. http://cdf.convio.net/site/DocServer/financialassistance0805.pdf Retrieved from.

- Conrad A., Gamboni C., Johnson V., Wojciak A.S., Ronnenberg M. Has the U.S. child welfare system become an informal income maintenance programme? A literature review. Child Abuse Review. 2020 doi: 10.1002/car.2607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Agriculture Facts about SNAP. 2019. https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/facts

- Department of Agriculture SNAP eligibility. 2020. https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/recipient/eligibility

- Department of Agriculture SNAP COVID-19 emergency allotments guidance. 2020. https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/covid-19-emergency-allotments-guidance

- Department of Agriculture. (n.d.). Addressing barriers & challenges. https://www.budget.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Addressing%20Barriers%20and%20Challenges%20-%20Seniors.pdf.

- Department of Labor. (n.d.). Unemployment insurance relief during covid-19 outbreak. https://www.dol.gov/coronavirus/unemployment-insurance.

- Drake B., Jonson-Reid M. In: Handbook of child maltreatment. Korbin J.E., Krugman R.D., editors. Springer; Netherlands: 2014. Poverty and child maltreatment; pp. 131–148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duva J., Metzger S. Addressing poverty as a major risk factor in child neglect: Promising policy and practice. Protecting Children. 2010;25(1):63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrle J., Geen R. Kin and non-kin foster care—Findings from a national survey. Children and Youth Services Review. 2002;24(1–2):15–35. doi: 10.1016/S0190-7409(01)00166-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrle, J., Geen, R., & Clark, R. (2001). Children cared for by relatives: Who are they and how are they faring? Washington, DC: Urban Institute. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED452287.pdf.

- Fallon B., Lefebvre R., Collin-Vézina D., Houston E., Joh-Carnella N., Malti T.…Cash S. Screening for economic hardship for child welfare-involved families during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid partnership response. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goelitz J.C. Answering the call to support elderly kinship caregivers. Elder LJ. 2007;15:1–31. http://publish.illinois.edu/elderlawjournal/files/2015/02/Goelitz.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hayslip B., Jr., Goodman C.C. Grandparents raising grandchildren: Benefits and drawbacks? Journal of Intergenerational Relationships. 2008;5(4):117–119. doi: 10.1300/J194v05n04_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonson-Reid M., Drake B., Zhou P. Neglect subtypes, race, and poverty. Child Maltreatment. 2012;18(1):30–41. doi: 10.1177/1077559512462452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kids Count Data Center . Annie E. Casey Foundation; Baltimore: 2019. Children in kinship care.https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/10455-children-in-kinship-care?loc=1&loct=1#detailed/1/any/false/1757/any/20160,20161 [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey E.W., Kinsey D., Rundle A.G. COVID-19 and food insecurity: An uneven patchwork of responses. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2020:332–335. doi: 10.1007/s11524-020-00455-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobulsky J.M., Dubowitz H., Xu Y. The global challenge of the neglect of children. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laborde D., Martin W., Vos R. International food policy research institute (IFPRI), Washington, DC. 2020. Poverty and food insecurity could grow dramatically as COVID-19 spreads. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Latzman N.E., Lokey C., Lesesne C.A., Klevens J., Cheung K., Condron S., Garraza L.G. An evaluation of welfare and child welfare system integration on rates of child maltreatment in Colorado. Children and Youth Services Review. 2019;96:386–395. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson M., Piel M.H., Simon M. Child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: Consequences of parental job loss on psychological and physical abuse towards children. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B.J., Mackey-Bilaver L. Effects of WIC and Food Stamp Program participation on child outcomes. Children and Youth Services Review. 2007;29(4):501–517. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2006.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E., Clarkson-Hendrix M., Lee Y. Parenting stress of grandparents and other kin as informal kinship caregivers: A mixed methods study. Children and Youth Services Review. 2016;69:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.J., Taylor C.A., Bellamy J.L. Paternal depression and risk for child neglect in father-involved families of young children. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2012;36(5):461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre R., Fallon B., Van Wert M., Filippelli J. Examining the relationship between economic hardship and child maltreatment using data from the Ontario incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect-2013 (OIS-2013) Behavioral Sciences. 2017;7(4):6–18. doi: 10.3390/bs7010006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llobrera J. Child support cooperation requirements in SNAP are unproven, costly, and put families at risk. 2020. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/child-support-cooperation-requirements-in-snap-are-unproven-costly-and-put#_ftn36

- Madigan S., Cyr C., Eirich R., Fearon R.P., Ly A., Rash C.…Alink L.R. Testing the cycle of maltreatment hypothesis: Meta-analytic evidence of the intergenerational transmission of child maltreatment. Development and Psychopathology. 2019;31(1):23–51. doi: 10.1017/S0954579418001700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire-Jack K., Wang X. Pathways from neighborhood to neglect: The mediating effects of social support and parenting stress. Children and Youth Services Review. 2016;66:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.04.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M., Citrin A. Center for the Study of Social Policy; 2014. Prevent, Protect & Provide: How child welfare can better support low-income families. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin B., Ryder D., Taylor M.F. Effectiveness of interventions for grandparent caregivers: A systematic review. Marriage & Family Review. 2016;53(6):509–531. doi: 10.1080/01494929.2016.1177631. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morelli N.M., Duong J., Evans M.C., Hong K., Garcia J., Ogbonnaya I.N., Villodas M.T. Intergenerational transmission of abusive parenting: Role of prospective maternal distress and family violence. Child Maltreatment. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1077559520947816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris M.C., Marco M., Maguire-Jack K., Kouros C.D., Im W., White C.…Garber J. County-level socioeconomic and crime risk factors for substantiated child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2019;90:127–138. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray J., Ehrle J., Geen R. Assessing the new federalism. Urban Institute; Washington, DC: 2004. Estimating financial support for kinship caregivers. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Musser E.D., Riopelle C., Latham R. Child maltreatment in the time of COVID-19: Changes in the Florida foster care system surrounding the COVID-19 safer-at-home order. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.104945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Family Assistance About TANF. 2017. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/programs/tanf/about retrieved from.

- Pac J., Waldfogel J., Wimer C. Poverty among foster children: Estimates using the supplemental poverty measure. Social Service Review. 2017;91(1):8–40. doi: 10.1086/691148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H. Grandmothers raising grandchildren: Family well-being and economic assistance. Focus. 2005;24(1):19–27. https://www.irp.wisc.edu/publications/focus/pdfs/foc241d.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Qualtrics. (n.d.-a). Everything you need to know when working with your IRB. Internal Qualtrics report: Unpublished.

- Qualtrics. (n.d.-b). What is a research panel (and should we have one)? Retrieved from https://www.qualtrics.com/experience-management/research/research-panels-samples/.

- Ratcliffe C., McKernan S.M., Zhang S. How much does the supplemental nutrition assistance program reduce food insecurity? American Journal of Agricultural Economics Review. 2011;93(4):1082–1098. doi: 10.1093/ajae/aar026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose R.A., Parish S.L., Yoo J.P. Measuring material hardship among the US population of women with disabilities using latent class analysis. Social Indicators Research. 2009;94(3):391–415. doi: 10.1007/s11205-008-9428-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum D., Bolen E., Neuberger Z., Dean S. States must act swiftly to deliver food assistance allowed by families first act. 2020. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/usda-states-must-act-swiftly-to-deliver-food-assistance-allowed-by-families

- Schanzenbach D., Pitts A. Food insecurity in the census household pulse survey data tables. 2020. https://www.ipr.northwestern.edu/documents/reports/ipr-rapid-research-reports-pulse-hh-data-1-june-2020.pdf

- Sedlak A.J., Mettenburg J., Basena M., Peta I., McPherson K., Greene A. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2010. Fourth national incidence study of child abuse and neglect (NIS-4) [Google Scholar]

- Slack K.S., Berger L.M. University of Wisconsin-Madison, School of Social Work and Institute for Research on Poverty; 2017. An economic stress model of child maltreatment and child protection system (CPS) involvement.https://www.prof2prof.com/resource/economic-stress-model-child-maltreatment-and-child-protection-system-involvement [Google Scholar]

- Slack K.S., Berger L.M., DuMont K., Yang M.Y., Kim B., Ehrhard-Dietzel S., Holl J.L. Risk and protective factors for child neglect during early childhood: A cross-study comparison. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33(8):1354–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.04.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Social Security Administration SI 00830.410 foster care payments. 2014. https://secure.ssa.gov/poms.nsf/lnx/0500830410 Retrieved from.

- StataCorp . StataCorp LP; College Station, TX: 2017. Stata statistical software: Release 15. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart A.L., Hays R.D., Ware J.E. The MOS short-form general health survey: Reliability and validity in a patient population. Medical Care. 1988;26:724–735. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stith S.M., Liu T., Davies L.C., Boykin E.L., Alder M.C., Harris J.M.…Dees J.E.M.E.G. Risk factors in child maltreatment: A meta-analytic review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2009;14(1):13–29. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2006.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltzfus E. Congressional Research Service; Washington, DC: 2012. Child welfare: A detailed overview of program eligibility and funding for foster care, adoption assistance and kinship guardianship assistance under title IV-E of the social security act. [Google Scholar]

- Straus M.A., Hamby S.L., Finkelhor D., Moore D.W., Runyan D. Identification of child maltreatment with the parent-child conflict tactics scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1998;22(4):249–270. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trainor K., Mallett J., Rushe T. Age related differences in mental health scale scores and depression diagnosis: Adult responses to the CIDI-SF and MHI-5. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;151(2):639–645. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2020. Child maltreatment 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Mental health and COVID-19. 2020. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/technical-guidance/mental-health-and-covid-19

- Wu Q., Xu Y. Parenting stress and risk of child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: A family stress theory-informed perspective. Developmental Child Welfare. 2020:1–17. doi: 10.1177/2516103220967937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q., Xu Y., Jedwab M. Custodial grandparent’s job loss during the COVID-19 pandemic and its relationship with parenting stress and mental health. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2021:1–11. doi: 10.1177/07334648211006222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Bright C., Ahn H., Huang H., Shaw T. A new kinship typology and factors associated with receiving financial assistance in kinship care. Children and Youth Services Review. 2020;110:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104822. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Wu Q., Jedwab M., Levkoff S.E. Understanding the relationships between parenting stress and mental health with grandparent kinship caregivers’ risky parenting behaviors in the time of COVID-19. Journal of Family Violence. 2020:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10896-020-00228-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Wu Q., Levkoff S., Jedwab M. Material hardship and parenting stress among grandparent kinship providers during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating role of grandparents’ mental health. Child Abuse &Neglect. 2020:104700. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M.Y. The effect of material hardship on child protective service involvement. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2015;41:113–125. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]