Abstract

IgA vasculitis (IgAV) is the most frequent form of vasculitis in childhood which classically presents with purpura of the lower extremities, joint pain or swelling and abdominal pain. Though it is a self-limiting disease, and its prognosis is generally good, glomerulonephritis is one of the most important complications. IgAV is classified as a small vessel vasculitis, and though glomerulonephritis develops in IgAV, necrotizing arteritis is rarely seen. Here, we present a case of a 13-year-old girl with IgAV, glomerulonephritis, and necrotizing arteritis in the small renal arteries. There have been only a few reports of adult cases of IgAV with necrotizing arteritis in the kidneys, but there have been no pediatric cases. Some previous reports showed a high mortality rate and implied the possibility of overlap with other vasculitides. In the current report, a rare case of IgAV is described which exhibited necrotizing arteritis rather than overlap with another vasculitis, with a relatively typical clinical course for IgAV and laboratory tests.

Keywords: IgA vasculitis, Glomerulonephritis, Necrotizing arteritis, Small vessel vasculitis

Introduction

IgA vasculitis (IgAV), formerly referred to as Henoch-Schonlein purpura, is the most common vasculitis in children; it is classically characterized by purpura, joint pain, abdominal pain, and renal symptoms. It is usually self-limiting with a good prognosis in children. The prevalence of renal involvement ranges from 20 to 60% [1, 2], and the majority develop within 1 month of onset. Histologically, crescent formation and mesangial proliferation, where IgA deposits are found on immunofluorescence examination, are characteristic. Its severity depends on the proportion of crescent formation. While the tubules and interstitium may show changes, arterioles remain normal, and vascular changes are rare. A rare case of IgAV that showed necrotizing arteritis in two interlobular renal arteries in a 13-year-old girl is presented. The differential diagnosis when necrotizing arteritis is found in a patient with IgAV is also presented, raising awareness of the need for close observation.

Case report

A previously healthy 13-year-old girl was admitted to the hospital due to abdominal pain and purpura of both lower extremities that had started a week earlier. Her medical history included an episode of pharyngitis that had occurred 3 weeks before admission. Otherwise, she had no relevant medical or family history.

At presentation, her blood pressure was 112/62 mmHg. No other abnormalities in the vital signs were observed. Multiple, non-tender, palpable areas of purpura were seen from the buttocks to the dorsal sides of the lower extremities. The abdomen was soft and mildly tender. The fecal occult blood test was positive. The history of purpura along with abdominal pain seemed typical for IgA vasculitis.

Results of laboratory tests on admission are shown in Table 1. On admission, full blood counts were unremarkable (white blood cell count 13,700/μL, hemoglobin 15.1 g/dL, platelet count 33.0 × 104/μL), and inflammatory markers were normal (CRP0.17 mg/dL). D-dimer (2.5 μg/dL) and FDP (6.7 μg/mL) were slightly elevated. Activity of coagulation factor XIII was low (57%). Renal function and serum complement levels were normal (serum creatinine 0.54 mg/dL, cystatin C 0.61 mg/L, CH50 56.4 U/mL, C3 126 mg/dL, and C4 34 mg/dL). Urinalysis showed proteinuria (2 +) and hematuria (2 +), and the red blood cells in the urine were 50–99 per high power field. The red blood cells in the urine were dysmorphic, and granular casts and hyaline casts were also observed. The urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCR) was 1.3 g/gCre, and serum protein and albumin remained normal (TP 7.7 g/dL, Alb 4.5 g/dL). A skin biopsy was performed on the first day of hospitalization. The specimen taken from an area of purpura showed early-stage leukocytoclastic vasculitis. IgA staining was negative. Intravenous prednisolone (1 mg/kg/day) was administered for 4 days for the gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. The therapy was effective and the patient was discharged on Day 8. Unfortunately, the proteinuria continued to increase (UPCR 2.1 g/gCre) and the serum albumin level decreased to 3.7 g/dL, renal biopsy was performed on Day 17. At the time of biopsy, the serum level of creatinine remained normal (0.52 mg/dL, Table 2).

Table 1.

Laboratory test results (on admission)

| Urinary findings | |||||||

| WBC | 13,700 | /μL | AST | 23 | IU/L | pH | 6.0 |

| Neu | 79.2 | % | ALT | 16 | IU/L | Gravity | 1.016 |

| Lympho | 13.1 | % | LDH | 180 | IU/L | Blood | 2 + |

| Hb | 15.1 | g/dL | CK | 54 | IU/L | Protein | 2 + |

| Hct | 45.3% | % | TP | 7.7 | g/dL | Red blood cells | 50–99/HPF |

| Plt | 33.0 × 104 | /μL | Alb | 4.5 | g/dL | White blood cells | 0–19/HPF |

| BUN | 11.4 | mg/dL | Hyaline casts | 30–49/HPF | |||

| PT/INR | 1.21 | Cre | 0.54 | mg/dL | Granular casts | 5–9/WF | |

| APTT | 28.0 | s | Na | 139 | mEq/L | Urinary protein | 136 mg/dL |

| d-dimer | 2.5 | μg/dL | K | 4.6 | mEq/L | Urinary creatinine | 117 mg/dL |

| FDP | 6.7 | μg/mL | Cl | 102 | mEq/L | ||

| Factor XIII | 57 | % | CRP | 0.17 | mg/dL | ||

| ESR | 4 | mm | |||||

| cystatin C | 0.61 | mg/L | |||||

| C3 | 126 | mg/dL | |||||

| C4 | 34 | mg/dL | |||||

| CH50 | 56.4 | U/mL | |||||

Table 2.

Laboratory test results (at biopsy)

| Urinary findings | ||||||||||

| WBC | 11,600 | /μL | AST | 29 | IU/L | ANA | × 40 | pH | 7.0 | |

| Neu | 70.0 | % | ALT | 19 | IU/L | ASO | 5 IU/mL | Gravity | 1.013 | |

| Lympho | 21.0 | % | LDH | 154 | IU/L | ASK | < × 40 | Blood | 2 + | |

| Hb | 13.5 | g/dL | CK | 206 | IU/L | PR3-ANCA | Negative | Protein | 2 + | |

| Hct | 39.8% | % | TP | 6.4 | g/dL | MPO-ANCA | Negative | Red blood cells | 50–99/HPF | |

| Plt | 29.6 × 104 | /μL | Alb | 3.7 | g/dL | RF | 3 IU/mL | White blood cells | 5–9/HPF | |

| BUN | 15.4 | mg/dL | C1q | 5.9 μg/mL | Hyaline casts | 10–19/WF | ||||

| Cre | 0.52 | mg/dL | cryoglobulin | Positive | Granular casts | 1–4/WF | ||||

| Na | 140 | mEq/L | Anti-GBM Ab | Negative | Urinary protein | 110 mg/dL | ||||

| K | 4.1 | mEq/L | Urinary creatinin | 50.1 mg/dL | ||||||

| Cl | 103 | mEq/L | ||||||||

| CRP | 0.08 | mg/dL | ||||||||

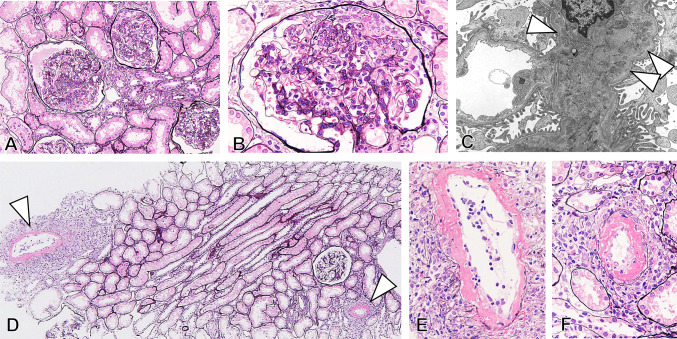

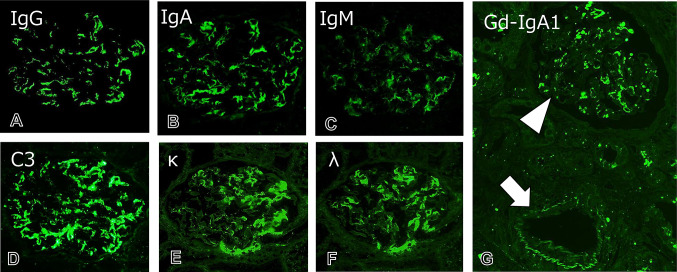

Renal biopsy specimens included a total of 23–26 glomeruli showing mild diffuse segmental proliferative glomerulonephritis (Fig. 1). Three glomeruli showed endocapillary proliferative lesions with cellular crescent formation in one glomerulus. Atrophy of renal tubules and interstitial inflammation and fibrosis were unremarkable. Notably, two renal arteries of interlobular size showed necrotizing arteritis with fibrin exudation and both neutrophil and lymphocyte infiltration. On immunofluorescence, granular mesangial deposition of IgA and galactose-deficient IgA1 (Gd-IgA1) accompanied by C3, IgM, and IgG was found (Fig. 2). The deposition of IgA and Gd-IgA1 could not be detected in the small arteries even in the ones without vasculitis. On electron microscopy, electron-dense deposits without organized structures were found in mesangial areas (Fig. 1C). The patient was diagnosed with IgAV with glomerulonephritis, and histological severity was scored as grade IIIb according to the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children.

Fig. 1.

Kidney biopsy findings. A Light microscopy shows mild to moderate diffuse segmental proliferative glomerulonephritis (silver stain; original magnification, × 200). B An endocapillary proliferative lesion is seen with inflammatory cell infiltration, fibrin exudation, and cellular crescents (silver stain; original magnification, × 400). Electron microscopy shows mesangial electron-dense deposits (arrowheads) in glomeruli without sub-endothelial and sub-epithelial deposits (E original magnification, × 2000). D–F In the two interlobular arteries, necrotizing arteritis (arrowheads) with inflammatory cell infiltration is noted (silver stain, original magnification, D × 100, E, F × 400)

Fig. 2.

Immunofluorescence findings. A–D Immunofluorescence study shows the granular mesangial deposition of IgA, IgG, IgM, and complement C3 in glomeruli (original magnification, × 600). E, F Both κ and λ light chains are noted as a mesangial granular pattern (original magnification, × 600). G The deposition of galactose-deficient IgA1 (Gd-IgA1) is evident in mesangial areas in glomeruli (arrowhead), compatible with IgAV. A small arteriole without necrotizing arteritis is negative for Gd-IgA1 (arrow) (original magnification, × 200)

Additional tests showed that cryoglobulin was positive, but rheumatoid factor, serum complement levels, anti-GBM antibody, antinuclear antibodies (ANA), PR3-, MPO-antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies(ANCA), and antibodies against hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV were all negative or within normal range.

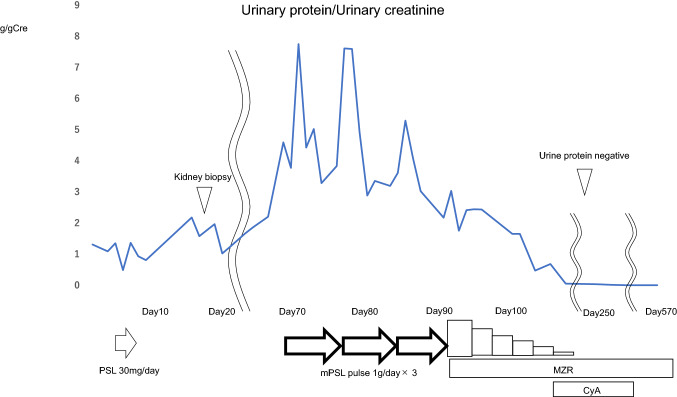

Since the proteinuria gradually increased up to 4.6 g/day, she underwent three pulses of intravenous methylprednisolone (1 g/day), followed by oral prednisone (60 mg/day), mizoribine (150 mg/day), and warfarin (1 mg/day). After three courses, urinary protein decreased to around 2 g/day, but unfortunately, the proteinuria (2+) and hematuria (1+) still remained. As an additional treatment, cyclosporine was introduced. After cyclosporine was added to the medication, the proteinuria disappeared within 4 months. The steroids and immunosuppressive agents were gradually reduced, and about 1 year and 7 months after the onset of nephritis, all steroids and immunosuppressive agents were discontinued, and only antiplatelet agents were administered. The antiplatelet medication was subsequently discontinued, but there have been no abnormalities in the urinalysis and remission is being maintained (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Clinical course. After 4 days of administration of PSL (30 mg/day), the patient was once discharged due to improvement in GI symptoms. The proteinuria kept increasing and renal biopsy was performed on Day 17. After 3 courses of mPSL pulse therapy (1 g/day), proteinuria gradually decreased but still remained at a relatively high level. After cyclosporine was introduced, the proteinuria disappeared within 4 months and about 1 year and 7 months after the onset of nephritis, all steroids and immunosuppressive agents were discontinued but remission has been maintained

Discussion

IgAV is the most common vasculitis in children which classically presents with purpura of the lower extremities, joint pain or swelling and abdominal pain. The prevalence of renal involvement varies from 20 to 60% [1, 2], and the short-term prognosis is mostly favorable in children. However, in older children and in adults, renal involvement is more likely to occur, and it tends to be more severe.

Though the diagnosis of IgAV is primarily based on clinical manifestations, confirmation of the diagnosis is done by biopsy of the involved organ. On light microscopy, IgAV with nephritis shows mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis and crescent formation with a wide range of abnormalities. The arterioles remain normal while tubulointerstitial changes may occur reflecting the severity. On immunofluorescence microscopy, diffuse granular deposits which always contain IgA predominantly are found in the mesangium. Galactose-deficient IgA1(Gd-IgA1) is an essential molecule which is a poor O-galactosylation form of IgA1. It specifically stains in the mesangium of IgAN and IgAV. Recently, these diseases have been described to share a similar pathogenesis. The overproduced Gd-IgA1 form immune complexes which deposit in the mesangium and induce mesangial cell activation which leads to glomerulonephritis [3]. Although the knowledge about the difference between IgAN and IgAV remains limited, glomerular staining of Gd-IgA1 is specific to these two diseases [4]. Whether the mesangial IgA or Gd-IgA1 deposition has been demonstrated is important, because few cases which were reported to have IgAV with necrotizing arteritis lacked this immunofluorescence feature, and the diagnosis of polyarteritis nodosa(PN) would have been more appropriate [5]. In the presented case, the diagnosis of IgAV with glomerulonephritis was based on both clinical manifestations and the renal biopsy findings.

Only few cases of IgAV patients exhibiting necrotizing arteritis in the kidneys have been reported, with, to the best of our knowledge, no pediatric cases. Pillebout et al. reported 250 adults with IgAV with nephritis [6]. Two patients showed necrotizing and granulomatous angiitis of the interlobular arteries. Yokose et al. [7] reported a case who was diagnosed with IgAV and later died of diffuse intrapulmonary hemorrhage and renal failure. The skin biopsy showed leukocytoclastic vasculitis and IgA deposits in the capillary walls. On autopsy, diffuse mesangial cell proliferation and crescent formation with IgA deposition in the mesangium and capillary walls of glomeruli were seen, suggestive of IgAV. However, small- and medium-sized arteries in the kidneys showed fibroid necrosis typical of PN. Yokose et al. reported that this case may be diagnosed as polyangiitis overlap syndrome (POS). POS was first mentioned by Leavitt et al. [8], who reported cases with several feature of systemic vasculitis. One patient who was diagnosed with IgAV confirmed by biopsy showed necrotizing vasculitis of medium-sized arteries. This patient had progressive renal failure, and cyclophosphamide was added. Nagasaka et al. [9] reported a case of a 74-year-old man who had both the features of microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) and IgAV. This patient presented with a skin rash, intracranial bleeding, acute renal failure, and pulmonary hemorrhage. The skin biopsy showed both leukocytoclastic vasculitis and small-sized arteritis. On the other hand, IgA deposits on the walls of capillaries of the skin and glomeruli taken at autopsy were seen. This case showed elevated MPO-ANCA levels, and overlap of MPA and IgAV was suggested.

As described, cases with more than one characteristics of vasculitis have been reported. Whether the patients had pre-existing vasculitis superimposed on or overlapped by another vasculitis remains unclear. Havill et al. [10] pointed out three possibilities: (1) truly coincidental; (2) the two different vasculitides represented another disease that cannot be classified by the current classification; and (3) as one autoimmune disease more likely to develop another autoimmune disease, the two different diseases could be related at a molecular and genetic level. In either case, it is important to make a prompt diagnosis and consider aggressive therapy given the rapid exacerbations in recent reports.

In the present case, laboratory examination showed positive serum cryoglobulin. Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis (CV) is another systemic disease included in the category of small vessel vasculitis. It is caused by cryoglobulins that presents with symptoms, such as skin lesion, muscle weakness, peripheral neuropathy, and arthralgia. CV is classified into three subgroups depending on its immunoglobulin composition [11]. Type I CV is composed of monoclonal IgG or IgM, type II and type III CV are called mixed CV, in which type II CV is composed of a mixture of monoclonal IgM (or IgG or IgA) with rheumatoid factor activity and polyclonal IgG. Type III CV is composed of a mixture of polyclonal IgM (or IgG or IgA) and polyclonal IgG. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) is seen in more than 80% of CV patients. Other histological findings of CV include intraluminal thrombi composed of cryoglobulins and vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis [12]. In the present case, however, the clinical course showed a relatively typical clinical course of IgAV and the systemic manifestations of CV were not evident. On renal biopsy findings, the deposition of polyclonal IgA, especially Gd-IgA1, on mesangial areas was noted in glomeruli lacking C1q deposition. In addition, MPGN was not seen on light microscopy, and sub-endothelial deposits with organized structure were not detected on electron microscopy. In terms of laboratory data, Garcia-fuentes et al. reported that 47% of the IgAVN patients in the acute phase (within 30 days of the onset of purpura) and 64% of the nephritis phase (2 months after the onset of purpura) showed raised concentration of cryoglobulins [13]. Though it is difficult to confirm whether the positive cryoglobulin had a role in this case, we considered that CV did not develop and the necrotizing vasculitis lesion was considered as part of IgAV.

Since necrotizing arteritis is not common in IgAV, further assessment was performed. The necrotizing artery was discovered by chance, and unfortunately, the obtained specimen had been cut too deep to be reevaluated. We could not find the necrotizing artery in either frozen or paraffin-embedded biopsy tissues. The deposition of IgA, Gd-IgA1, and electron-dense deposits on small arteries with necrotizing vasculitis could not be found. In the other renal arteries which did not show necrotizing arteritis, neither IgA, Gd-IgA1, electron-dense deposits were detected. In the present case, together with the clinical manifestation and laboratory tests and the small size of the vasculitis, we concluded that the case was compatible with IgAV nephritis as a whole.

To our knowledge, no cases of IgAV with nephritis and necrotizing arteritis have been reported in children. Similar reports in adults have been published, and they had a relatively severe course [5, 6]. It is important to differentiate IgAV and IgAV with necrotizing arteritis, since the prognosis may change dramatically.

In summary, a pediatric case of IgAV with glomerulonephritis and necrotizing arteritis was presented. IgAV is classified as a small vessel vasculitis, and both glomerulonephritis and necrotizing arteritis may develop in IgAV. Further studies will be needed to clarify the presence of IgAV with both glomerulonephritis and necrotizing arteritis and their clinical and pathological characteristics.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Trapani S, Micheli A, Grisolia F, Resti M, Chiappini E, Falcini F, De Martino M. Henoch Schonlein purpura in childhood: epidemiological and clinical analysis of 150 cases over a 5-year period and review of literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;35(3):143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang WL, Yang YH, Wang LC, Lin YT, Chiang BL. Renal manifestations in Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a 10-year clinical study. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20(9):1269–1272. doi: 10.1007/s00467-005-1903-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suzuki H, Kiryluk K, Novak J, Moldoveanu Z, Herr AB, Benfrow MB, Wyatt RJ, Scolari F, Mestecky J, Gharavi AG, Julian BA. The pathophysiology of IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(10):1795–1803. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011050464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki H, Yasutake J, Makita Y, Tanbo Y, Yamasaki K, Sofue T, Kano T, Suzuki Y. IgA nephropathy and IgA vasculitis with nephritis have a shared feature involving galactose-deficient IgA1-oriented pathogenesis. Kidney Int. 2018;93(3):700–705. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Habib R. Renal involvement in Schönlein-Henoch purpura. In: Tisher CC, Brenner BM, editors. Renal pathology with clinical and functional correlations. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 2011. pp. 409–433. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pillebout E, Thervet E, Hill G, Alberti C, Vanhille P, Nochy D. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adults: outcome and prognostic factors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(5):1271–1278. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000013883.99976.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yokose T, Aida J, Ito Y, Ogura M, Nakagawa S, Nagai T. A case of pulmonary hemorrhage in Henoch-Schönlein purpura accompanied by polyarteritis nodosa in an elderly man. Respiration. 1993;60(5):307–310. doi: 10.1159/000196224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leavitt RY, Fauci AS. Polyangitis overlap syndrome. Classification and prospective clinical experience. Am J Med. 1986;81(1):79–85. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90186-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagasaka T, Miyamoto J, Ishibashi M, Chen KR. MPO-ANCA and IgA-positive systemic vasculitis: a possibly overlapping syndrome of microscopic polyangitis and Henoch-Schoenlein purpura. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36(8):871–877. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2008.01145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Havill JP, Levine SM, Kuperman M, Hellmann DB, Geetha D. Falling through the cracks of vasculitis classification—a report of three patients. NDT Plus. 2011;4(5):327–330. doi: 10.1093/ndtplus/sfr054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brouet JC, Clauvel JP, Danon F, Klein M, Seligmann M. Biologic and clinical significance of cryoglobulins: a report of 86 cases. Am J Med. 1974;57(5):775–788. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(74)90852-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaidan M, Terrier B, Pozdzik A, Frouget T, Rioux-Leclercq N, Combe C, Lepreux S, Hummel A, Noël LH, Marie I, Legallicier B, François A, Huart A, Launay D, Kaplanski G, Bridoux F, Vanhille P, Makdassi R, Augusto JF, Rouvier P, Karras A, Jouanneau C, Verpont MC, Callard P, Carrat F, Hermine O, Léger JM, Mariette X, Senet P, Saadoun D, Ronco P, Brochériou I, Cacoub P, Plaisier E. Spectrum and prognosis of noninfectious renal mixed cryoglobulinemic GN. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(4):1213–1224. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015020114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Fuentes M, Chantler C, Williams DG. Cryoglobulinaemia in Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Br Med J. 1977;2(6080):163–165. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6080.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]