Abstract

Biobanks are instrumental for accelerating research. Early in SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the Argentinean Biobank of Infectious Diseases (BBEI) initiated the COVID19 collection and started its characterization.

Blood samples from subjects with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection either admitted to health institutions or outpatients, were enrolled. Highly exposed seronegative individuals, were also enrolled. Longitudinal samples were obtained in a subset of donors, including persons who donated plasma for therapeutic purposes (plasma donors). SARS-CoV-2-specific IgM and IgG levels, IgG titers and IgG viral neutralization capacity were determined.

Out of 825 donors, 57.1% were females and median age was 41 years (IQR 32–53 years). Donors were segregated as acute or convalescent donors, and mild versus moderate/severe disease donors. Seventy-eight percent showed seroconversion to SARS-CoV-2 specific antibodies. Specific IgM and IgG showed comparable positivity rates in acute donors. IgM detectability rate declined in convalescent donors while IgG detectability remained elevated in early (74,8%) and late (83%) convalescent donors. Among donors with follow-up samples, IgG levels seemed to decline more rapidly in plasma donors. IgG levels were higher with age, disease severity, number of symptoms, and more durable in moderate/severe disease donors. Levels and titers of anti-spike/RBD IgG strongly correlated with neutralization activity against WT virus.

The BBEI-COVID19 collection serves a dual role in this SARS-CoV-2 global crisis. First, it feeds researchers and developers transferring samples and data to fuel research projects. Second, it generates highly needed local data to understand and frame the regional dynamics of the infection.

Keywords: Biobank, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Antibody response, Convalescent plasma

Biobank, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Antibody response, Convalescent plasma.

1. Introduction

In December 2019, a cluster of cases of atypical interstitial pneumonia caused by an unknown agent was reported in China [1]. Afterwards, it was described that this new disease (termed COVID-19) was caused by a novel human coronavirus which was isolated, characterized and named Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [2]. Since then, the number of global cases has increased rapidly, with the WHO declaring COVID-19 a pandemic in March 2020. By April 21st, 2021, more than 140 million cases have been confirmed worldwide, with more than 3 million associated deaths [3]. In Argentina, the first case was confirmed on March 3rd, 2020 in a 43-year-old male returning from a trip around Spain and Italy. This report was followed by other imported cases and soon local circulation was established. The number of cases has reached 2.7 million (including 60,083 deaths) by April 21st, 2021 [4].

SARS-CoV-2 can be transmitted from human to human by respiratory droplets and aerosols, and close contact with infected people and contaminated objects. The infection can be symptomatic or asymptomatic. In most cases, symptoms appear within 48–72 hr after exposure and may include fever, cough, runny nose, odynophagia, headache, asthenia, myalgia, anosmia, ageusia, skin manifestations among others [5]. Although most subjects recover after experiencing a mild disease, a minority of individuals progress to a severe disease with symptoms and signs associated with viral pneumonia and pulmonary involvement, which may lead to the need of mechanical ventilation and death. Less frequently, neurological manifestations may present [6]. People with comorbidities such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, hypertension, obesity, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are overrepresented among those with severe COVID-19 and those who died. Indeed, the fatality rate is particularly high in older patients, in whom comorbidities are common [7].

The COVID-19 pandemic brought a great challenge to society and, more specifically, to the health and scientific systems. Social containment measures have been adopted worldwide to stop virus dissemination. As it occurred in most countries around the globe, the Argentinean health-care system quickly adapted to cope with an overwhelming number of acutely ill patients, and the scientific community redirected their research to provide responses to the emergency, guided by the Ministry of Science.

Although tremendous advances have been made, our understanding regarding the dynamics of the disease is not complete, slowing the processes of developing proper diagnostic algorithms, efficacious treatments, and preventive vaccines. We have established the first national Biobank of Infectious Diseases in Argentina in 2017, the BBEI (BBEI, Biobanco de Enfermedades Infecciosas). A biobank is a key tool in biomedical research, connecting basic and translational sciences. The proper and secure storage of large amounts of human biological samples from patients with specific conditions or healthy donors allows exploration and discovery of markers for pathological conditions, as well as identification and validation of new therapies [8]. For instance, emerging technologies, such as nanotechnology, have the potential to develop unprecedented solutions to the challenges imposed by the pandemic and biobanks play a key role in these process by securing sample accessibility [9, 10]. At the same time, a biobank guarantees adherence to ethical and legal requirements in order to protect citizen rights [11]. Upon SARS-CoV-2 emergence, the BBEI rapidly initiated the collection of blood samples from confirmed or highly suspected COVID-19 subjects. At the same time, the Argentinean Ministry of Science and Technology promoted the development of basic research projects focused on SARS-CoV-2 infection [12]. Among these projects, the BBEI COVID19 collection was selected to receive funding. This prompted the completion of our first aim which was to create a biobank of biological samples of over 1,000 individuals with COVID19 diagnosis (in acute and convalescence phase) to fuel research projects within the country by transferring samples and their clinical data. As a secondary aim we performed an in-depth clinical, immune and genetic characterization of this population. This allowed to foster research by contributing additional laboratory data associated with these samples. Here, we present demographic, diagnostic, clinical and humoral response data of the initial 825 enrolled individuals. While the majority of donors with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by molecular diagnosis seroconverted, a small proportion remained IgM and IgG negative. SARS-CoV-2 IgG response could be detected even at 5 months following symptoms onset with signs of waning by that time, particularly in the mild disease group. Finally, a steeper decay in IgG levels was observed in participants recovered that donated plasma for therapeutic purposes.

2. Results

2.1. Cohort description

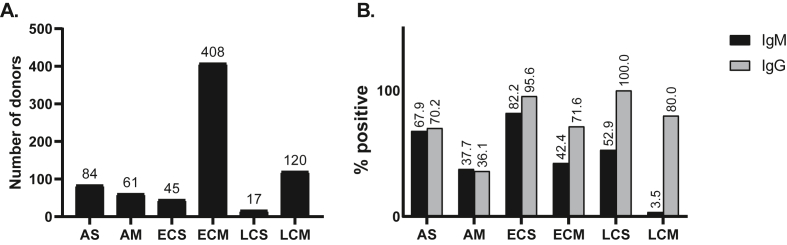

Administrative tasks to start the COVID-19 collection within the BBEI began on March 27th, 2020. Confirmed or highly suspected COVID-19 subjects were summoned by social networks advertisements to be part of the COVID19 collection. From April 9th to October 9th, samples from 825 donors were enrolled, at a rate of 6.65 samples per working day. Moreover, longitudinal samples were obtained from 37 donors. Out of these initial 825 donors, 5596 vials of plasma, 2287 vials of serum, 1616 vials of cell pellets and 4347 vials of cryopreserved PBMCs were generated and this material became available to those researchers who might request it. Overall, 57.1% donors were females (n = 471) and median age was 41 years (IQR 32–53 years); 6.6% were between 16 and 25 years old, and 16.8% were older than 60. Within the first donations, imported cases were overrepresented; but the local/imported ratio was rapidly reverted as regional circulation increased over the weeks. Donors were segregated as acute donors (those whose samples were obtained within 15 days from symptom onset), early convalescent donors (those whose samples were obtained within 60 days from symptom onset) and late convalescent donors (those whose samples were obtained later than 60 days from symptom onset). In turn, donors included within these groups were segregated into those with mild or moderate/severe disease. The latter was defined by the presence of related complication such as pneumonia, hypoxemia or need of oxygen. Thus, six groups were defined: acute severe (AS, N = 84), acute mild (AM, N = 61), early convalescent severe (ECS, N = 45), early convalescent mild (ECM, N = 408), late convalescent severe (LCS, N = 17), late convalescent mild (LCM, N = 120) (Table 1, Figure 1A). We could also define a seventh group composed of highly exposed SARS-CoV-2 seronegative contacts (ES, N = 45), identified as persons who lived together with confirmed COVID-19 cases while they were symptomatic, but presented no evidence of infection themselves (no symptoms and negative SARS-CoV-2 serology after 21 days of exposure). Since it is known that a proportion of recovered subjects from SARS-CoV-2 infection do not seroconvert, it is worth noting here that it cannot be categorically excluded that infection had indeed occurred in ES. Moreover, it cannot be affirmed that they are resistant to the infection as the possibility that they acquired the infection after sample donation to BBEI cannot be excluded. Finally, 45 donors could not be segregated into any of these groups so they were excluded from further analysis. This group included donors who resulted negative in antibody testing, had no record of molecular diagnostic and had no history of extremely close contact with a confirmed COVID-19 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Subject characteristics.

| Groups: |

AS N = 84 (10.2%) |

AM N = 61 (7.4%) |

ECS N = 45 (5.5%) |

ECM N = 408 (49.5%) |

LCS N = 17 (2.1%) |

LCM N = 120 (14.5) |

ES N = 45 (5.5%) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics: | ||||||||

| Age (years) Median (IQR) | 57.5 (47.5–67.2) | 36.5 (29.5–48.5) | 49 (39.25–57.5) | 37 (31–47.7) | 57 (50.5–63) | 36 (29–49) | 37 (31–51) | 0.000 |

| Female sex (N, %) | 33 (39.3%) | 29 (47.5%) | 19 (42.2%) | 252 (61.8%) | 9 (52.9%) | 80 (66.7%) | 23 (51.1%) | 0.001 |

| Days since symptoms onset Median (IQR) | 10 (7–13) | 8 (5–12) | 36 (21–48) | 38 (28–45) | 72 (64.5–88) | 80 (68–96) | 41 (24–66) | <0.0001 |

| Comorbidities (N, %) | ||||||||

| HTN | 32 (38.1%) | 5 (8.2%) | 10 (22.2%) | 30 (7.4%) | 4 (23.5%) | 6 (5%) | 4 (8.9%) | 0.000 |

| DBT | 10 (19.2%) | 2 (5%) | 5 (13.9%) | 7 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.2%) | 3 (7.7%) | 0.000 |

| Obesity | 19 (22.6%) | 5 (8.2%) | 6 (13.3%) | 19 (4.7%) | 2 (11.8%) | 7 (5.9%) | 2 (4.4%) | 0.002 |

| DLP | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (4.4%) | 3 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.2%) | 0.141 |

| ASTHMA | 8 (9.5%) | 2 (3.3%) | 4 (8.9%) | 12 (2.9%) | 2 (11.8%) | 3 (2.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.10 |

| HIV infection | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.6%) | 1 (2.2%) | 7 (1.7%) | 2 (11.8%) | 5 (4.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.01 |

| COVID TREATMENT (N, %) | 16 (20%) | 1 (1.7%) | 16 (37.2%) | 8 (2%) | 6 (40%) | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.000 |

| POSITIVE SARS CoV2 PCR (N, %) | 84 (100.0%) | 61 (100.0%) | 40 (88.9%) | 356 (86.7%) | 16 (94.1%) | 63 (52.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.000 |

| IgG anti SARSCoV2 + (N, %) | 59 (70.2%) | 22 (36.1%) | 43 (95.6%) | 292 (71.6%) | 17 (100.0%) | 96 (80.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.000 |

| IgM anti SARSCoV2 + (N, %) | 57 (67.9%) | 23 (37.7%) | 37 (82.2%) | 173 (42.4%) | 9 (52.9%) | 45 (37.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.000 |

AS: acute severe, AM: acute mild, ECS: early convalescent severe, ECM: early convalescent mild, LCS: late convalescent severe, LCM: late convalescent mild, ES: highly exposed SARS-CoV-2 seronegative contacts, HTN: arterial hypertension, DBT: diabetes, DLP: dyslipidemia.

Figure 1.

A. Distribution of donors with past or present confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection per group (Total N = 735). Infection was confirmed either by molecular diagnostic, serology or both. B. SARS-CoV-2-specific IgM and IgG positivity rate per group. Antibodies were evaluated in plama samples by ELISA using the COVIDAR kit. AS: acute severe, AM: acute mild, ECS: early convalescent severe, ECM: early convalescent mild, LCS: late convalescent severe, LCM: late convalescent mild.

Seventy-five percent of donors had confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by molecular diagnosis (PCR). For donors who had not been tested by PCR (because they did not accomplish the criteria of suspected case at the time of diagnosis), infection was confirmed by serology. Most frequent comorbidities included arterial hypertension, diabetes, obesity, dyslipidemia, asthma and HIV infection. Comorbidities were overrepresented in donors who were experiencing or had experienced severe disease. Moreover, 48 donors received treatment, mostly consisting in azithromycin or plasma from recovered subjects.

2.2. Dynamics of antibody responses

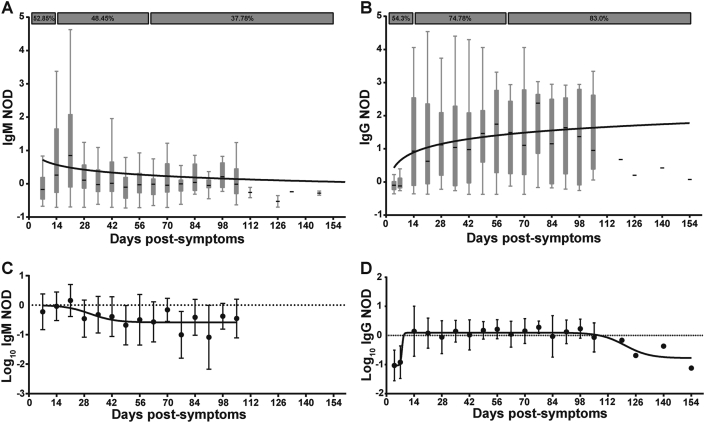

In order to evaluate the levels of SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG and IgM responses across all groups, these antibodies were qualitatively measured by COVIDAR ELISA. Normalized ODs (NOD) were calculated in order to compare data from different assays. Out of 825 donors, 579 (78,7% of the cohort excluding ES) showed SARS-CoV-2 specific antibodies, either IgM, IgG or both. Furthermore, we identified donors with positive molecular diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection (positive PCR, N = 620) and no detectable antibody levels (N = 152/620; 24,5%). Within this group, 34 were sampled during the very first days (2–7 days) after symptom onset so it is likely that sampling occurred too early to detect specific antibodies. Figure 2 shows the levels of IgM and IgG specific responses following symptoms onset. SARS-CoV-2-specific IgM was detected within the first days following symptoms onset; 52.85% of acutely infected donors had detectable plasma IgM (Figure 2A). IgM NOD started to increase between day 14 and 21 and then it showed a downward curve with a detectability rate of 48.45% between days 14 and 60 post-symptom onset. However, it is worth noting that IgM remained detectable in a significant proportion of donors (37.78%) between day 60 and 105 after symptom onset. IgM was undetectable in samples obtained after day 106 following symptoms onset. SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG showed an ascendant slope within the first two weeks from symptom onset, reaching a plateau between days 14 and 21, and it was detectable in samples obtained up to 154 days after symptom onset (Figure 2B). Positivity rate was 54.3% within acutely ill donors, a proportion comparable to that of IgM. The proportion of IgG detectability remained elevated in early and late convalescent donors (74.8% and 83.0%, respectively). Figures 2C and D show log10 transformation of IgM and IgG NOD respectively. This transformation eliminates negative responses. Again, it can be observed that IgM response climbed early and showed a slightly descending curve becoming undetectable in donors whose samples were obtained at very late convalescent stages. On the other hand, IgG could be detected in samples obtained up to 120 days following symptom onset and then a decay phase began, suggesting that IgG levels might decrease over time following this period. However, it must be noted that data from late time-points after symptom onset are represented by a low number of donors so these conclusions should be further confirmed by increasing sample size.

Figure 2.

Dynamics of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG antibodies. A) Normalized optical density (NOD) measures for IgM, and B) IgG antibodies, were plotted by days post-symptoms onset. Positivity rates for acute, as well as early and late convalescent infection are indicated in both cases. C) Log10 of NOD values for IgM, and D) IgG antibodies were also obtained. Median and 25th and 75th percentiles are shown in A and B, while mean and standard errors are indicated in C and D. Longitudinal data was modeled by using a semi-log (A, B) and a sigmoidal 4PL non-linear regression model (C, D); best fitted curves are depicted in the plots.

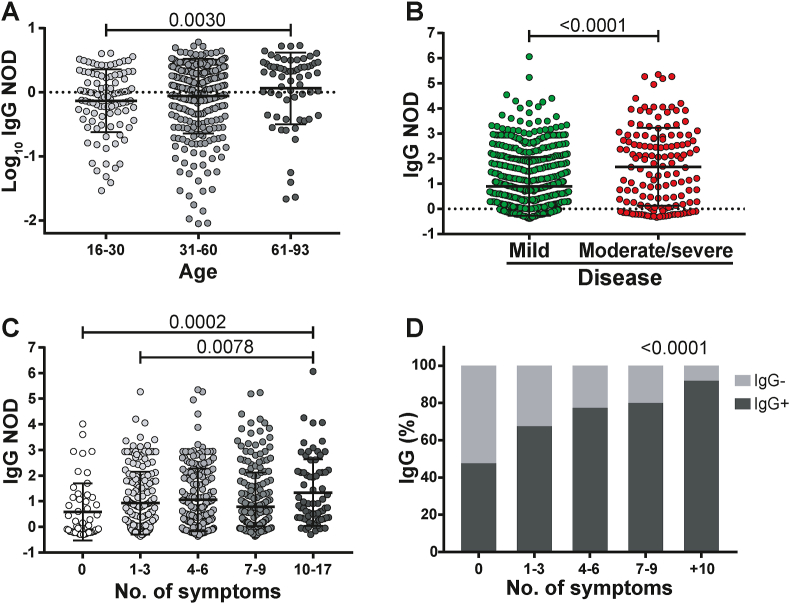

Globally, no differences were observed in SARS-specific IgM or IgG responses between genders (not shown). SARS-specific IgM or IgG positive rates across groups are shown in Figure 1B. IgM and IgG rates are similar in the acute group. IgG rates were the highest in convalescent donors (both early and late) while IgM was the lowest in late convalescents. Of note, within each group (acute, early convalescent or late convalescent), higher positivity rates were observed in donors with severe/moderate disease compared to the mild disease group (donors who received plasma treatment were excluded from all analyses). When analyzing detectable IgG responses, older donors had higher levels of SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG (Figure 3A). In turn, IgG NOD was higher in donors with moderate/severe versus mild disease (Figure 3B, p < 0.0001). It also augmented with an increasing number of symptoms, being statistically higher in donors with ten or more symptoms compared with asymptomatic donors (p = 0.0002) or donors reporting few symptoms (p = 0.0078) (Figure 3C). Moreover, the probability of a positive IgG result increased as the number of symptoms augmented (p < 0.0001, Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Characterization of IgG response in COVID-19 patients. A) Log10 of normalized optical density (NOD) IgG values from patients within separate age groups. B) NOD IgG levels from individuals with mild or moderate/severe disease. C) NOD IgG values from individuals displaying different number of symptoms. D) Positivity rate for IgG antibodies versus number of symptoms. Individual values, mean and standard deviation are shown. Statistical comparisons were made by using Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's post-test (A, D), two-sided Mann-Whitney test (B) and chi squared test for trend (D). p values are indicated in each panel.

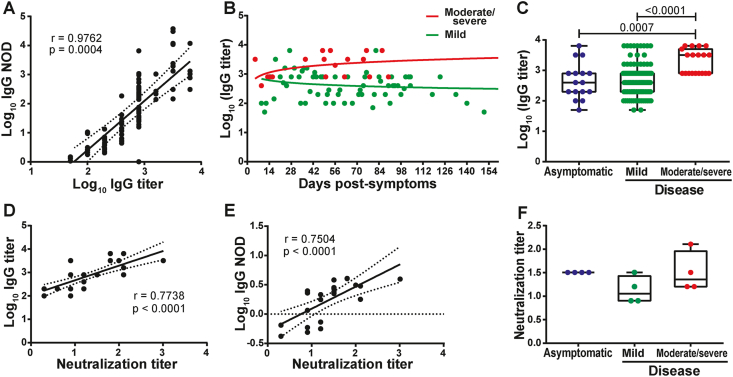

2.3. IgG titers and neutralization capacity

SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG titers were measured in a subset of donors (N = 119). Logarithmic IgG titers showed a strong direct correlation with Log10(IgG NOD) (Linear regression R2 = 0,9486, Spearman's correlation r = 0.9762, p = 0.0004), indicating that Log10(IgG NOD) stands as a good surrogate for IgG response quantitation (Figure 4A). Analysis of IgG titers along time (in samples from different donors) revealed that this parameter, albeit showing a great heterogeneity among donors, remained rather stable during convalescent stage and up to 105 days after symptom onset (Figure 4B). Donors who experienced a severe disease tended to show elevated and stable antibody titers after recovery compared to the mild disease group, which in turn showed a slight decrease in antibody titers over time. Indeed, statistical modeling of data showed that antibody titers remained steadily high long after the onset of symptoms in moderate/severe patients, while in the mild disease group, a slightly decrease in antibody titer was observed, confirming both groups behaved differently (p = 0.0227, Figure S1A). Moreover, when comparing IgG titers from convalescent donors (samples obtained after 15 days from symptom onset) with mild or moderate/severe disease, the latter group showed statistically higher titers (p < 0.0001; Figure 4C). Furthermore, IgG titers were measured in asymptomatic subjects. This group showed similar titers to the mild disease group and statistically lower titers than the severe disease group (p = 0.0007, Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Relationship between optical density, titer, and neutralizing capacity of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies. A) Correlation analysis between Log10 of normalized optical density (NOD) and Log10 of IgG titers. B) Log10 of IgG titers corresponding to individuals who experienced moderate/severe (red dots) or mild disease (green dots) were plotted by day post-symptoms onset. C) Log10 of IgG titers from asymptomatic, and symptomatic individuals. D) Correlation analysis between Log10 IgG titers and IgG neutralizing titers and E) Log10 of NOD IgG values versus and IgG neutralizing titers. F) IgG neutralizing titers from asymptomatic, and symptomatic individuals. Individual measures, median and 25th and 75th percentiles are shown. Correlation studies were performed by using the Spearman rank test. In B, longitudinal data were studied by multiple linear regression, with disease severity and days post symptoms as independent predictors. Coefficients as wells as linear prediction equations are shown in Figure S1A. Statistical comparisons between groups in C and F, were made by using Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's post-test. p values are indicated in each panel.

A subset of samples (N = 34) were then tested for their capacity to neutralize WT SARS-CoV-2 virus. Neutralization titers showed moderate to strong direct correlations with Log10 (IgG titers) (Spearman's correlation r = 0.7738, p < 0.0001; Figure 4D) and Log10 (IgG NOD) (Spearman's correlation r = 0.7504, p < 0.0001; Figure 4E). The data support the use of anti-spike and anti-RBD IgG levels as a surrogate of IgG titers and, most important, SARS-CoV-2 neutralization titers.

In order to provide a deeper insight into the characteristics of the antibody response in asymptomatic donors and in those who experienced a mild or moderate/severe disease, 4 donors from each group with equal IgG titer (i.e. 800) were selected and used to evaluate viral neutralization capacity. Results indicated that, within a given IgG titer, asymptomatic donors develop neutralizing antibodies to the same extent as severe disease donors (Figure 4F).

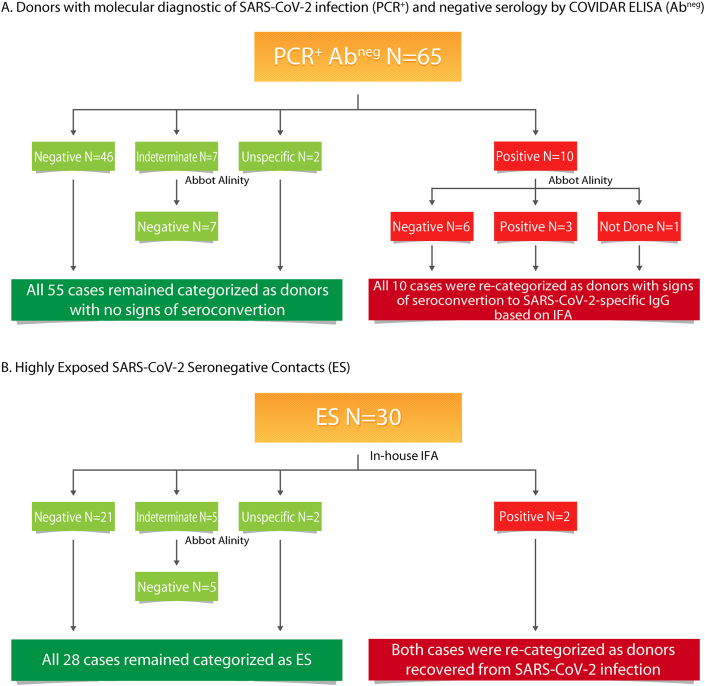

2.4. Complementary analysis in donors with discordant diagnostic results (positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR and non-detectable antibodies) and highly exposed SARS-CoV-2 seronegative contacts (ES)

In order to rule out the possibility that PCR+/abneg donors as well as donors consigned as ES donors had antibody responses but not detected by the COVIDAR ELISA, we used two additional assays in selected samples to solve discordant diagnostic results, to discard false negative results and to properly categorize donors within the cohort. First, we used an in-house IF assay to detect SARS-CoV-2 specific IgG. Out of 65 selected samples from PCR+/abneg donors, 46 were negative in the IFA, 7 were indeterminate (did not reach positive criteria), and 2 resulted in an unspecific reaction (signal was observed both in infected cells and in the uninfected control) (Figure 5A). The 7 samples with indeterminate results were also tested using the Abbot Alinity assay and resulted IgG negative. Thus, in all these 55 cases, the COVIAR result was confirmed and donors remained categorized as donors with molecular diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection but no evidence of IgG seroconversion. On the other hand, 10 samples had detectable SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG by IFA. Out of these, 3 were also positive in the Abbot Alinity assay, 6 were negative and 1 was not tested. These 10 cases were re-categorized as donors with signs of seroconvertion to SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG based on IFA (Figure 5A). In the case of one of these donors (whose initial sample was obtained 35 days after symptom onset and whose results were COVIDAR not detectable, IFA positive and Alinity not detectable), we could obtain a follow-up sample (at day 90 after symptom onset) that now had a detectable result in the COVIDAR kit, confirming that the IFA result was correct. Probably, the broader IFA antigenic configuration helped detect IgG antibodies earlier in this case.

Figure 5.

Flowchart indicating serology results obtained using different methodologies to evaluate SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG. A) Analysis in a subgroup of donors with molecular diagnostic of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PCR+) and undetected SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG by the COVIDAR kit (Abneg). B) Analysis in a subgroup of suspected highly exposed uninfected donors.

On the other hand, 30 arbitrary selected EU were also tested by IFA. Twenty-one tested negative, 5 were indeterminate, 2 resulted positive and in other 2 unspecific reactions were observed. Out of the 5 indeterminate, none had a detectable result at the Abbot Alinity assay. Thus, 28 EU remained categorized as such. Conversely, 2 donors had detectable SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG by IFA, so they were recategorized as infected recovered donors (Figure 5B).

Additionally, the biobank had a set of 4 particular donors. None of them had molecular diagnostic done, all were antibody negative by COVIDAR but had positive antibody results by other commercially available ELISA kits that had been performed in other settings (private laboratories). One of them was positive by IFA and Abbot Alinity, one was indeterminate by IFA and positive by Abbot Alinity, one was positive by IFA and negative by Abbot Alinity and one was negative by IFA (Abbot Alinity was not performed in this case). Moreover, plasma from these donors were evaluated for neutralization activity. Two of them showed clear inhibition of viral replication with neutralization titers of 8, and >32, respectively, confirming the presence of SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies in these samples. Thus, three donors were categorized as confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases based on the criteria of having at least one detectable serological test. The fourth donor was also categorized as confirmed SARS-CoV-2 case based on the external serology result and an incident was added to its records in order to denote this issue.

Overall, the use of multiple assays with different configurations helped rule out the discordant diagnostic results, allowed to confirm the infection in these cases, and permitted the re-categorization of at least 16 cases. It is worth noting that these results were accounted for the final segregation of donors into the corresponding category presented at the initial section of this work.

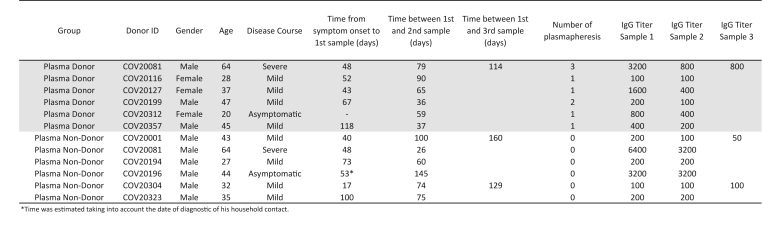

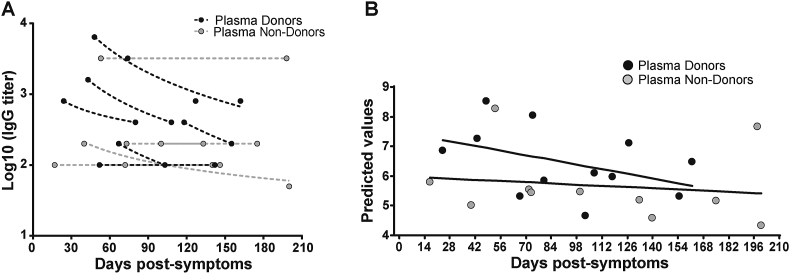

2.5. Changes in SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG titers after plasma donation

A group of donors belonging to the collection also donated plasma for treatment at different health institutions from Buenos Aires. Six of them returned at different times after plasma donation, so we were able to measure IgG titers before and after donation (plasma donors). For comparison, IgG titers were also evaluated in longitudinal samples from individuals who did not donate plasma (plasma non-donors) (Figure 6). Figure 7A shows the IgG titers at different time-points evaluated in the 6 plasma donors and in 5 plasma non-donors. At first sight, it can be observed that plasma donors show a steeper decay in IgG titer than plasma non-donors. This is also true if we compare these curves with the titer curve of the whole group (Figure 4B). When IgG antibody titers were analyzed in function of time elapsed from day of symptoms onset using a repeated measures lineal regression model, plasma donors showed indeed a stepper decay than plasma non-donors (p = 0.0006, Figure 7B, Figure S1B). Although the sample size in this analysis is small, this observation deserves further analysis as administration of convalescent plasma is one possible treatment available to prevent disease worsening in at-risk individuals [13]. It is important to highlight that SARS CoV-2 specific cellular response did not change over time in these individuals when Spike- and RBD-specific IFN-γ secreting cells were evaluated by ELISPOT (Figure S2). Thus, it is important to identify factors affecting antibody levels in plasma units to be used for treatment.

Figure 6.

Characteristic of plasma donors and non-donors included in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Fluctuations in IgG titers due to convalescent plasma donation. A) Antibody titers from samples obtained both before and after convalescent plasma donation were quantified, and plotted by days post-symptom onset (black dots, plasma-donors). Time-matched samples from plasma non-donors were analyzed as controls (grey dots, plasma non-donors). B) A repeated measures lineal regression analysis was applied to model data. Plasma donation, days since the onset of symptoms, as well as the interaction between them were set as fixed predictors, and subjects as random effects. Fitted lines are shown. Fixed effects estimates as well as linear prediction equations are shown in Figure S1B.

3. Discussion

Biobanks are key entities to accelerate basic, preclinical, translational, and clinical research. As SARS-CoV-2 spread worldwide, there was, and still is, an urgent need to learn more about this virus, to understand and treat the spectrum of clinical manifestations it produces, as well as to stop its spreading in the human population. As a result, the demand from the research community for samples from infected or recovered patients, as well as its related clinical data, has increased dramatically. In this context, the BBEI rapidly rearranged its procedures in order to cope with this need and started to collect process and store COVID-19 samples and data, very early after SARS-CoV-2 landing in Argentina. Concomitantly, an in-depth clinical, immune and genetic characterization of this collection is being performed. This adds an extra value to the collection since all the data generated will be available upon request which represents a tool to accelerate basic and translational research projects. In this initial report (encompassing data from 825 donors), the dynamics, magnitude and quality of humoral response within a period of 5 months after symptom onset is described, and also changes in IgG dynamics in recovered participants that donated plasma for therapeutic purposes.

In the first place, it was observed that there exists an extraordinary heterogeneity in the level of SARS-CoV-2 spike- and RBD-specific IgM and IgG antibodies among individuals. As others reported, specific IgM and IgG appeared early and simultaneously [14]. IgM levels did not achieve a plateau, instead they showed a slight decrease. Nevertheless, a significant proportion of donors had detectable specific IgM up to 100 days after symptom onset. This limits IgM utility as a marker of acute or “active” infection and also opens the question regarding its usefulness in identifying possible reinfections since a detectable result could occur due to carry-over from the first episode. On the contrary, specific IgG seems to be more stable over time with a high positivity rate even in samples obtained after 120 days following symptom onset. Early short-term longitudinal studies following SARS-CoV-2-specific antibody dynamics are in line with our observation that IgG levels appear to be maintained for 4–5 months. After 5 months, the magnitude of the humoral response wanes, however, the detectability rate remains high [15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22]. Then, the longevity of the response is influenced by a number of factors such as age, number of symptoms, the severity of the disease, the magnitude of the peak IgG response, among others, as shown here and in other reports [23, 24, 25, 26, 27]. More recent reports, involving longer follow-up, indicates that specific antibodies can be detected up to 11 months post-symptoms onset and, more importantly, that the infection induces a robust long-lived B-cell memory response [16, 18, 25, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32]. Thus, despite antibody declining, this memory response could confer long-term protection to subsequent exposures, disease progression after a re-infection and it could determine vaccine efficacy. Indeed, anti-SARS-CoV-2 humoral responses are boosted by vaccination in COVID19 convalescent individuals indicating that memory humoral responses are functional [31, 33].

One noteworthy finding in our cohort is the high percentage of individuals who had molecular diagnostic of infection but no evidence of seroconversion after 21 days of symptoms onset. The analysis with different methodologies to detect SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies, within this subset of donors, and the study of follow-up samples, allowed evidence, at least in a minor proportion of these donors, the presence of SARS-CoV-2 specific antibodies. Several reports in the literature indicate that combined antibody detection through multiple assays with different specificities helps to increase the sensitivity and specificity in serological diagnostics [34, 35, 36, 37]. Still, specific antibodies remained undetectable in a considerable high proportion of donors (15.2% of the whole cohort), compared to other reports that describe only 5–10% or even less [38, 39, 40]. One possible reason to explain this discrepancy could be associated with false positive results of the molecular diagnostic, which was proven not so infrequent in the context of mass testing [41, 42]. Second, the highest rates of antibody detectability are shown in studies involving persons who were or had been hospitalized while our study might be biased due to the inclusion of a number of asymptomatic donors, mainly represented by health workers screened during routine surveillance at their hospitals. In turn, this leads to a third hypothesis, which is the possibility of SARS-CoV-2 carriage without infection, as has already been described for other respiratory viruses (including common coronaviruses) [43] and that can even be overcome with a protective innate immune response leading to an abortive infection [44, 45]. Finally, SARS-CoV-2-specific memory T-cells have been widely detected in seronegative individuals who had COVID19 diagnostic and even in exposed contacts [46, 47, 48, 49]. One particular study revealed that 17% of convalescent potential plasma donors participating in their study had borderline or negative antibody testing while most of them had T-cell immunity against SARS-CoV-2 [50]. Altogether, antibody testing alone may underestimate the true prevalence of the infection or population immunity [51]. Evaluation of SARS-CoV-2-specific T-cell responses in our cohort is ongoing.

Besides antibody binding capacity, determining neutralization capacity is key to understand the role of humoral response in the natural course of the disease. There is wide consensus that a robust neutralizing antibody response rises early following infection and that this response is mostly determined by the magnitude of anti-spike and anti-RBD IgGs [17, 20, 21, 35, 52, 53, 54, 55]. Measuring neutralization activity against WT SARS-CoV-2 can be labor intensive and is restricted to institutions with BSL-3 facilities and properly trained personnel. Alternative protocols have been developed using pseudotyped viruses but still infrastructure limitations apply. Here, we confirm that the level of S-specific and RBD-specific IgG antibodies measured by the COVIDAR kit (either as IgG NOD or IgG end-point titer) can function as surrogate markers of neutralization activity against WT SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 4E). This has also been previously demonstrated in an independent work using SARS-CoV-2 pseudotyped VSV particles [20].

The use of plasma from persons recovered from COVID-19 was one of the first treatments administered. There is growing evidence that early infusion is effective in preventing disease worsening but its success relies on the use of plasma units with high titers of SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies and early administration [13, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61]. Limitations for this treatment include donor eligibility (exclusion criteria apply), willingness of recovered persons to donate (probably more than once), early administration, logistic issues, among others [62, 63, 64, 65, 66]. Other antibody-based therapies have been developed to replace the use of convalescent plasma, such as monoclonal antibodies and hyperimmune equine serum, but at higher costs [67, 68]. Thus, it is worth investing efforts to improve the scope of this treatment. Here, we observed that SARS-CoV-2 IgG titers decay rate would be more rapid after plasma donation. Even though it has not been described previously, this observation was not completely unexpected. Plasmapheresis has been used to treat humoral rejection in kidney transplant by reducing antibody levels [69]. Although our observation still needs to be confirmed in a larger cohort and in a specially designed work, it still deserves attention since it might be a factor to be mitigated in order to maximize the benefit in plasma recipients. In this regard, concern has already been raised highlighting the need of antibody measurement at the time of plasmapheresis based on the spontaneous decay in IgG titer [70]. Moreover, optimum timing from symptom onset to plasma donation has been proposed [71, 72]. Perreault et al evaluated anti-RBD IgG in plasma donors who donated multiple times [73]. They found that the anti-RBD antibody levels waned over time as a consequence of time and not of the number of donations. However, they did not have a non-donor group to compare the declining rate as in our study. More recently, Jain et al did not found differences in SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence rate in a group of plasma donors along sequential plasma donations. However, the quantity of antibodies was not evaluated [74]. On the other hand, Korper et al observed different (stable, decreasing, increasing) patterns of SARS-CoV-2-specific neutralizing antibodies after repeated plasmapheresis sessions [75]. Thus, antibody levels should be unavoidable measured before each plasmapheresis, even for individuals who donate multiple times within a few days, in order to guarantee the quality, in terms of specific IgG titers, of the plasma to be used. At the individual level, it is unlikely that protective immunity could be affected in sequential plasma donors. So far, there is no evidence that plasma donors are more susceptible to re-exposures [74]. Indeed, the magnitude of SARS-CoV-2-specific T-cell responses seems to be unchanged pre- and pos-donation thus protection would be conferred by cellular memory responses.

SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has driven the world to an unprecedented crisis, not only in terms of public health but also social, financial and productive. However, it has highlighted the role of basic and translational science in the society. In this context, biobanks have gained visibility within research community but also in the community as a whole, mostly driven by the ability to widely and immediately share samples and data from COVID-19 patients with warranted quality thus accelerating research, and by engaging community to promote sample donation. Moreover, the BBEI-COVID19 collection served a dual role in this emergency situation. First, it accomplished the main aim of creating a tool to boost researchers and developers transferring samples upon request for approved projects. By the date this manuscript was initially submitted, 1029 donors were included in the collection and 927 biological specimens were transferred to 9 biomedical research projects, while other 335 samples have been requested, and are awaiting for committee approval. At the same time, it generated highly needed local data of extreme importance to understand and frame the regional dynamics of the infection. Part of this data was included in this manuscript which aimed to describe the characteristics and main findings of this group of donors, as well as to provide relevant data in this emergency context. Nevertheless, results should be interpreted cautiously considering that the study has some limitations. First, the sample consisted of volunteers which affects the findings in many ways: i) there is an effect of the willingness to participate; ii) the access to the medias where the invitation to participate was announced restrained the volunteers that could donate their samples; iii) the area where they live was also limited and has specific and particular demographic and social characteristics, and in that sense does not cover the adult population which creates some representativeness bias. Second, most of the data were self-reported, which may lead to some bias (recall, declaration, etc.). Third, even if the number of individuals could satisfy the main objective, it could be not enough to have the statistical power for calculate risk factors and other associations. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of the study jeopardizes the possibility to establish temporal relationships among variables of interest.

As we can expect that this pandemic will continue to be of paramount concern for months to come, work at biobanks will continue filling in the gaps of existing knowledge as well as dissecting future challenges such as the effect of vaccines on the pandemic dynamics or the potential of reinfections.

3.1. Resource availability

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Natalia Laufer (nlaufer@fmed.uba.ar). All the information included in the manuscript is available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author and prior approval of the biobank directory board.

4. Methods

4.1. BBEI COVID-19 cohort

The BBEI receives blood donations from subjects with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by Real Time PCR or antibody testing. Donors can be inpatient, admitted to health institutions (4 institutions from Buenos Aires city) or outpatient individuals (who were invited to donate blood samples to the Biobank through social networks, radio and television). Donors must provide written consent for the donation and are interviewed by the researchers (outpatients) or physicians (donors admitted at health institutions) to complete a case report form (CRF) with clinical and demographic data (see “Data and sample collection” below). Additionally, medical records were used to obtain data when available. Additionally, highly exposed SARS-CoV-2 negative contacts (ES), defined as: persons who lived together with confirmed cases while they were symptomatic, but presented no evidence of infection, were enrolled [76]. Data corresponding to the initial 825 donors to the BBEI were included in the report. No formal sample size calculation was performed. Enrollment continued until December 2020 with a final number of 1060 donors having being enrolled. Donors included in this study were enrolled between April 9th, 2020 to October 9th, 2020. No momentary or gift compensation was offered to the donors.

4.2. Ethics

The SARS CoV-2 collection within the BBEI was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the non-for-profit research organization Fundación Huésped (Comité de Bioética Humana, Fundación Huésped, Buenos Aires, Argentina).

4.3. Data and sample collection

After signing the consent, 30 ml of whole blood were collected from donors in EDTA containing tubes (BD Vacutainer), and 10 ml in tubes containing no anticoagulants (SST tubes, BD Vacutainer). Following this, donors provided information regarding: gender, age, place of residence, whether they acquired the infection in Argentina or overseas, date of symptoms onset, date of diagnostics, comorbidities, treatments and complications. Regarding symptoms, donors were asked if they had experienced fever, headache, cough, expectoration, runny nose, dyspnea, odynophagia, asthenia, myalgia, anosmia, ageusia, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and/or skin manifestations. Every other relevant clinical data such as laboratory and image findings, hypoxemia, need of oxygen therapy and ventilation, were recorded.

4.4. Sample processing

Blood samples were processed within 4 h from withdrawal. Tubes were centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 10 min. Serum was separated from tubes without anticoagulants, aliquoted and stored at -80 °C. Plasma was separated from EDTA-containing tubes, aliquoted and stored at -80 °C. Then, blood was diluted and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation (GE Healthcare, Sweden). Two pellets of 1 million cells were stored at -80 °C for nucleic acid extraction and the remaining cells were preserved in a solution of fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) supplemented with 10% DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) and stored in liquid nitrogen.

4.5. Antibody assessment

The presence of SARS-CoV-2-specific IgM and IgG antibodies was evaluated in plasma samples from all donors enrolled in the biobank by ELISA using the COVIDAR kit. This kit was developed by Argentinean researchers from CONICET, Fundación Instituto Leloir and UNSAM, together with Laboratorio Lemos S.R.L. The validation process determined that sensitivity to detect specific IgG raises to 90% after 3 weeks of symptoms onset while specificity is 100% [20]. Briefly, samples were loaded in wells pre-coated with recombinant SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein and RBD. After incubation, wells were washed and HRP-conjugated anti-human IgG (or IgM) was added. Finally, the plates were developed using TMB substrate. Cut-off was calculated as the mean of the negative controls +0.2 (IgG) or +0.3 (IgM). Normalized optical density (NOD) values were calculated by subtracting the cut-off value to each donor sample OD value, and the resulting value was divided by the mean positive control OD value. In a selected subset of donors, SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG was titrated by making 2-fold serial dilutions of plasma.

Additionally, a subset of selected samples were also evaluated using an in-house indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) and by the commercially available kit Abbott Alinity i SARS-CoV-2 IgG. IFA was carried out by the InViV working group. Briefly, Vero Clon76 cells (ATCC CRL-587) were inoculated with SARS-CoV-2 strain (hCoV-19/Argentina/PAIS-G0001/2020, GISAID, ID: EPI_ISL_499083) at a multiplicity of infection (moi) = 0.1. Twenty-four-hour post-infection, cells were harvested, seeded into slides (10.000 cells/well) and then fixed using cold (4 °C) acetone for 30 min. Slides seeded with uninfected cells were also prepared as negative controls. Donor sera were diluted 1:5 in 1X PBS and added onto slides containing infected or uninfected cells. Slides were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min, washed, and then stained with FITC-labelled anti-human IgG for 30 min. After incubation, slides were washed and observed in a fluorescence microscope (Olympus Motorized Inverted Research, Model IX81, Imaging Software: Cell M). Samples were considered positive for SARS-COV-2 IgG antibodies when the specific apple-green fluorescence was located in the cytoplasm or on the plasma membrane in approximately 80% of the cells and no fluorescence staining was observed in the corresponding uninfected control.

Abbott Alinity i SARS-CoV-2 IgG kit, which captures SARS-CoV-2 N-specific antibodies, was used following manufacturer's instructions.

4.6. Virus neutralization

Vero-E6 cells were maintained in DMEM medium (Sigma-Aldrich) plus 2 mM L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 U/ml penicillin (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 10% FBS (Gibco BRL, USA). SARS-CoV-2 strain (hCoV-19/Argentina/PAIS-G0001/2020, GISAID Accession ID: EPI_ISL_499083) was kindly provided by Dr. Sandra Gallego (InViV working group). Serial 2-fold dilutions of decomplemented plasma were incubated with 200 plaque-forming units (PFU) of SARS-CoV-2 for 1 h at room temperature, in triplicate. Then, mixtures were added to 80% confluent Vero-E6 cell monolayers in 96-well plates and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Then, cells were washed and culture medium with 2% FBS was added. After 72 h, plates were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature and stained using a 0.5% crystal violet dye solution in acetone and methanol. Neutralization titer was calculated as the inverse of the highest plasma dilution that showed 80% cytopathic effect inhibition.

4.7. Data analysis and statistics

All data (clinical, demographics and laboratory data) associated with each donor was kept at the Noraybanks software database (Noraybio, Spain). Upon admission to the biobank, each donor was provided with a code (de-identification) and kept anonymous for subsequent processes. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software), InfoStat [77], R project (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and SPSS software v.19.0 (SPSS Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Antibody titer fluctuations after plasma donation were analyzed by using the lmer package. Univariate analyses were performed to determine the relation of SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG (NOD, titer, neutralization capacity) with age, disease severity, and number of symptoms. Mann-Whitney test was used to compare two groups. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's post-test was used to compare more than 2 groups. Chi-squared test was used to compare proportions. Bivariate correlations were performed by using the non-parametric Spearman's rank test. To study changes in IgG levels vs. time (in both mild and moderate/severe cases), a multiple linear regression, with disease severity and days post symptoms as independent predictors, was used (outcomes are shown in Figure S1A). In order to determine if plasma donation had an effect on longitudinal SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG levels, a repeated measures lineal regression analysis was applied to model data. Plasma donation, days since the onset of symptoms, as well as the interaction between them were set as fixed predictors, and subjects as random effects. Fixed effects estimates, as well as linear prediction equations are shown in Figure S1B. All tests were two-tailed and were considered statistically significant when the p-values were <0.05.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Yesica Longueira, Natalia Laufer and Gabriela Turk: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

María Laura Polo: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Funding statement

This work was supported by Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (Proyecto COVID N° 11, IP 285).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We profoundly thank COVIDAR working group for kits supply, technical advice and data interpretation and discussion. We particularly thank Andrea Gamarnik for insightful inputs into the manuscript. COVIDAR working group: Diego OJEDA, María Mora GONZALES LEDESMA, Guadalupe S. COSTA NAVARRO, Horacio M. PALLARES, Lautaro N. SANCHEZ, Sergio M. VILLORDO, Diego E. ALVAREZ, Julio J. CARAMELO, Jorge J. CARRADORI, Marcelo J. YANOVSKI y Andrea V. GAMARNIK (Fundación Instituto Leloir-CONICET, Buenos Aires, Argentina).

Authors specially acknowledge to BBEI donors for agreeing to collaborate with the biobank and to provide blood samples.

We also thank Mr. Fernando Montesano for his invaluable help with donor admission and data entry; and Mr. Sergio Mazzini for language editing.

Appendix B

Biobanco de Enfermedades Infecciosas Colección COVID19 working group: Sabrina AZZOLINA1, 2, Silvia BALINOTTI4, Cinthia CASTRO4, Alejandro CZERNIKIER1, 2, Yanina GHIGLIONE1, 2, Denise Anabella GIANNONE2, 9, Virginia GONZALAZ POLO1, 2, Verónica LACAL4, Natalia LAUFER2, 3, Yesica LONGUEIRA1, 2, Marcelo H. LOSSO8, Laura MORENO MACIAS8, Andrea PEÑA MALAVERA7, Claudio PICCARDO1, 2, María Laura POLO1, 2, María Florencia QUIROGA2, 3, Maximiliano MARTINEZ4, Jimena NUÑEZ4, Sebastián NUÑEZ4, Carla PASCUALE1, 2, María REY4, Claudia SALGUEIRA5, Horacio SALOMON2, 3, Melina SALVATORI1, 2, Gabriela SIGNES6, Luciana SPADACCINI5, Melisa TATTA5, César TRIFONE1, 2, Gabriela TURK2, 3, María Belén VECCHIONE2, 10

1Universidad de Buenos Aires. Facultad de Medicina. Buenos Aires. Argentina. 2CONICET – Universidad de Buenos Aires. Instituto de Investigaciones Biomédicas en Retrovirus y SIDA (INBIRS). Buenos Aires. Argentina. 3Universidad de Buenos Aires. Facultad de Medicina. Departamento de Microbiología, Parasitología e Inmunología. Buenos Aires. Argentina. 4Sanatorio Güemes, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina. 5Sanatorio Anchorena, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina. 6Servicio Penitenciario Federal, Argentina. 7CONICET – Instituto de Tecnología Agroindustrial del Noroeste Argentino, Estación Experimental Agroindustrial Obispo Colombres, Tucumán, Argentina. 8Hospital General de Agudos José María Ramos Mejía, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina. 9Universidad de Buenos Aires. Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales. Departamento de Química Biológica. Buenos Aires. Argentina. 10Universidad de Buenos Aires. Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales. Departamento de Fisiología, Biología Molecular y Celular. Buenos Aires. Argentina.

∗ InViV Working Group: Sandra GALLEGO1,2, Lorena SPINSANTI1, Brenda KONIGHEIM1,2, Sebastián BLANCO1, Adrián DIAZ1,2, Juan Javier AGUILAR1, Claudia BOSSA1, María Elisa RIVAROLA1, Mauricio BERANEK1,2.

1Instituto de Virología “Dr. J. M. Vanella” (INVIV), Facultad de Ciencias Médicas, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Córdoba, Argentina.

2Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas CONICET, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Appendix A Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

Figure S1: Results from the multiple linear regression applied in Figure 4.b (A) and the mixed effect model applied in Figure 7.b (B).

Figure S2: Spike- and RBD-specific IFN--secreting cells measured by ELISPOT in samples obtained from plasma donors pre- and pos-donation.

References

- 1.Zhu N. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou P. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . 2021. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Situation Reports.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministerio de Salud de la Republica Argentina . 2021. COVID19 Daily Report.https://www.argentina.gob.ar/coronavirus/informes-diarios/reportes/abril2021 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macera M. Clinical presentation of COVID-19: case series and review of the literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17(14) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17145062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellul M.A. Neurological associations of COVID-19. Lancet Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30221-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Apicella M. COVID-19 in people with diabetes: understanding the reasons for worse outcomes. Lancet Diab. Endocrinol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30238-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malsagova K. Biobanks-A platform for scientific and biomedical research. Diagnostics. 2020;10(7):E485. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10070485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdelhamid H.N., Badr G. Nanobiotechnology as a platform for the diagnosis of COVID-19: a review. Nanotechnol. Environ. Eng. 2021;6(1):19. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaudhary V. Advancements in research and development to combat COVID-19 using nanotechnology. Nanotechnol. Environ. Eng. 2021;6(1):8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doménech García N., Cal Purrinos N. Biobancos y su importancia en el ámbito clínico y científico en relación con la investigación biomédica en Espãna. Reumatol. Clínica. 2014;10(5):304–308. doi: 10.1016/j.reuma.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rabinovich G.A., Geffner J. Facing up to the COVID-19 pandemic in Argentina. Nat. Immunol. 2021;22(3):264–265. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-00873-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Libster R. Early high-titer plasma therapy to prevent severe covid-19 in older adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2033700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiang F. Antibody detection and dynamic characteristics in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71(8):1930–1934. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolke E., Matuschek C., Fischer J.C. Loss of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in mild covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383(17):1694–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2027051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y. Quick COVID-19 healers sustain anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody production. Cell. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crawford K.H.D. Dynamics of neutralizing antibody titers in the months after SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaebler C. Evolution of antibody immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2021;591(7851):639–644. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03207-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maine G.N. Longitudinal characterization of the IgM and IgG humoral response in symptomatic COVID-19 patients using the Abbott Architect. J. Clin. Virol. 2020;133:104663. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ojeda D.S. Emergency response for evaluating SARS-CoV-2 immune status, seroprevalence and convalescent plasma in Argentina. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wajnberg A. Robust neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 infection persist for months. Science. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.abd7728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou W. The dynamic changes of serum IgM and IgG against SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.26353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takahashi T. Sex differences in immune responses that underlie COVID-19 disease outcomes. Nature. 2020;588(7837):315–320. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2700-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li K. Dynamic changes in anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies during SARS-CoV-2 infection and recovery from COVID-19. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):6044. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19943-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xia W. Longitudinal analysis of antibody decay in convalescent COVID-19 patients. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):16796. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-96171-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vogelzang E.H. Development of a SARS-CoV-2 total antibody assay and the dynamics of antibody response over time in hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients with COVID-19. J. Immunol. 2020;205(12):3491–3499. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.2000767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shrock E. Viral epitope profiling of COVID-19 patients reveals cross-reactivity and correlates of severity. Science. 2020;(6520):370. doi: 10.1126/science.abd4250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Breathnach A.S. Prior COVID-19 protects against reinfection, even in the absence of detectable antibodies. J. Infect. 2021;83(2):237–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogega C.O. Durable SARS-CoV-2 B cell immunity after mild or severe disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2021;131(7) doi: 10.1172/JCI145516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi D. Dynamic characteristic analysis of antibodies in patients with COVID-19: a 13-month study. Front. Immunol. 2021;12:708184. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.708184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Z. Naturally enhanced neutralizing breadth against SARS-CoV-2 one year after infection. Nature. 2021;595(7867):426–431. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03696-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dan J.M. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science. 2021;(6529):371. doi: 10.1126/science.abf4063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rossi A.H. Sputnik V vaccine elicits seroconversion and neutralizing capacity to SARS-CoV-2 after a single dose. Cell Rep. Med. 2021;2(8):100359. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Elslande J. Antibody response against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and nucleoprotein evaluated by four automated immunoassays and three ELISAs. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020;26(11):1557.e1–1557.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lamikanra A. 2021. Comparability of Six Different Immunoassays Measuring SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies with Neutralizing Antibody Levels in Convalescent Plasma: from Utility to Prediction. Transfusion. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li L. Molecular and serological characterization of SARS-CoV-2 infection among COVID-19 patients. Virology. 2020;551:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2020.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun B. Kinetics of SARS-CoV-2 specific IgM and IgG responses in COVID-19 patients. Emerg. Microb. Infect. 2020;9(1):940–948. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1762515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang J. COVID-19 confirmed patients with negative antibodies results. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020;20(1):698. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05419-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou F. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Y. Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of COVID-19. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20(6):656–657. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30232-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim A.Y., Gandhi R.T. Re-infection with SARS-CoV-2: what goes around may come back around. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Surkova E., Nikolayevskyy V., Drobniewski F. False-positive COVID-19 results: hidden problems and costs. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8(12):1167–1168. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30453-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jansen R.R. Frequent detection of respiratory viruses without symptoms: toward defining clinically relevant cutoff values. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011;49(7):2631–2636. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02094-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Angka L. Is innate immunity our best weapon for flattening the curve? J. Clin. Invest. 2020;130(8):3954–3956. doi: 10.1172/JCI140530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Newton A.H., Cardani A., Braciale T.J. The host immune response in respiratory virus infection: balancing virus clearance and immunopathology. Semin. Immunopathol. 2016;38(4):471–482. doi: 10.1007/s00281-016-0558-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cox R.J., Brokstad K.A. Not just antibodies: B cells and T cells mediate immunity to COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20(10):581–582. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00436-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sekine T. Robust T cell immunity in convalescent individuals with asymptomatic or mild COVID-19. Cell. 2020;183(1):158–168 e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodda L.B. Functional SARS-CoV-2-specific immune memory persists after mild COVID-19. Cell. 2021;184(1):169–183 e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gallais F. Intrafamilial exposure to SARS-CoV-2 associated with cellular immune response without seroconversion, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;27(1) doi: 10.3201/eid2701.203611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwarzkopf S. Cellular immunity in COVID-19 convalescents with PCR-confirmed infection but with undetectable SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;27(1) doi: 10.3201/2701.203772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Canete P.F., Vinuesa C.G. COVID-19 makes B cells forget, but T cells remember. Cell. 2020;183(1):13–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iyer A.S. Dynamics and significance of the antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 infection. medRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muecksch F. Longitudinal analysis of serology and neutralizing antibody levels in COVID19 convalescents. J. Infect. Dis. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suthar M.S. Rapid generation of neutralizing antibody responses in COVID-19 patients. Cell Rep. Med. 2020;1(3):100040. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2020.100040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang X. Neutralizing antibodies responses to SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19 inpatients and convalescent patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rejeki M.S. Convalescent plasma therapy in patients with moderate-to-severe COVID-19: a study from Indonesia for clinical research in low- and middle-income countries. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;36:100931. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cho Y. Effectiveness of convalescent plasma therapy in severe or critically ill COVID-19 patients: a retrospective cohort study. Yonsei Med. J. 2021;62(9):799–805. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2021.62.9.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simonovich V.A. A randomized trial of convalescent plasma in covid-19 severe pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2031304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xia X. Improved clinical symptoms and mortality among patients with severe or critical COVID-19 after convalescent plasma transfusion. Blood. 2020;136(6):755–759. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020007079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pau A.K. Convalescent plasma for the treatment of COVID-19: perspectives of the national institutes of health COVID-19 treatment guidelines panel. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Joyner M.J. Effect of convalescent plasma on mortality among hospitalized patients with COVID-19: initial three-month experience. medRxiv. 2020 p. 2020.08.12.20169359. [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Silvestro G. Preparedness and activities of the anti-SARS-CoV-2 convalescent plasma bank in the Veneto region (Italy): an organizational model for future emergencies. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2021;60(4):103154. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2021.103154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Terada M. How we secured a COVID-19 convalescent plasma procurement scheme in Japan. Transfusion. 2021;61(7):1998–2007. doi: 10.1111/trf.16541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Izak M. Vox Sang; 2021. Qualifying Coronavirus Disease 2019 Convalescent Plasma Donors in Israel. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Muttamba W. Feasibility of collecting and processing of COVID-19 convalescent plasma for treatment of COVID-19 in Uganda. PLoS One. 2021;16(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nagoba B. Positive aspects, negative aspects and limitations of plasma therapy with special reference to COVID-19. J. Infect Publ. Health. 2020;13(12):1818–1822. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Esmaeilzadeh A. Recent advances in antibody-based immunotherapy strategies for COVID-19. J. Cell. Biochem. 2021 doi: 10.1002/jcb.30017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lopardo G. RBD-specific polyclonal F(ab)2 fragments of equine antibodies in patients with moderate to severe COVID-19 disease: a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, adaptive phase 2/3 clinical trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;34:100843. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Montgomery R.A. Plasmapheresis and intravenous immune globulin provides effective rescue therapy for refractory humoral rejection and allows kidneys to be successfully transplanted into cross-match-positive recipients. Transplantation. 2000;70(6):887–895. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200009270-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Terpos E., Mentis A., Dimopoulos M.A. Loss of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in mild covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383(17):1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2027051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li L. Characteristics and serological patterns of COVID-19 convalescent plasma donors: optimal donors and timing of donation. Transfusion. 2020;60(8):1765–1772. doi: 10.1111/trf.15918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gontu A. Limited window for donation of convalescent plasma with high live-virus neutralizing antibody titers for COVID-19 immunotherapy. Commun. Biol. 2021;4(1):267. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-01813-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Perreault J. Waning of SARS-CoV-2 RBD antibodies in longitudinal convalescent plasma samples within 4 months after symptom onset. Blood. 2020;136(22):2588–2591. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020008367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jain R. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 among potential convalescent plasma donors and analysis of their deferral pattern: experience from tertiary care hospital in western India. Transfus. Clin. Biol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.tracli.2021.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Korper S. Donors for SARS-CoV-2 convalescent plasma for a controlled clinical trial: donor characteristics, content and time course of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies. Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2021;48(3):137–147. doi: 10.1159/000515610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ng O.T. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence and transmission risk factors among high-risk close contacts: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30833-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Di Rienzo J.A. Centro de Transferencia InfoStat, FCA, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba; Argentina: 2020. InfoStat Versión 2020.http://www.infostat.com URL. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Results from the multiple linear regression applied in Figure 4.b (A) and the mixed effect model applied in Figure 7.b (B).

Figure S2: Spike- and RBD-specific IFN--secreting cells measured by ELISPOT in samples obtained from plasma donors pre- and pos-donation.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.