Abstract

A reverse line blot (RLB) assay was developed for the identification of cattle carrying different species of Theileria and Babesia simultaneously. We included Theileria annulata, T. parva, T. mutans, T. taurotragi, and T. velifera in the assay, as well as parasites belonging to the T. sergenti-T. buffeli-T. orientalis group. The Babesia species included were Babesia bovis, B. bigemina, and B. divergens. The assay employs one set of primers for specific amplification of the rRNA gene V4 hypervariable regions of all Theileria and Babesia species. PCR products obtained from blood samples were hybridized to a membrane onto which nine species-specific oligonucleotides were covalently linked. Cross-reactions were not observed between any of the tested species. No DNA sequences from Bos taurus or other hemoparasites (Trypanosoma species, Cowdria ruminantium, Anaplasma marginale, and Ehrlichia species) were amplified. The sensitivity of the assay was determined at 0.000001% parasitemia, enabling detection of the carrier state of most parasites. Mixed DNAs from five different parasites were correctly identified. Moreover, blood samples from cattle experimentally infected with two different parasites reacted only with the corresponding species-specific oligonucleotides. Finally, RLB was used to screen blood samples collected from carrier cattle in two regions of Spain. T. annulata, T. orientalis, and B. bigemina were identified in these samples. In conclusion, the RLB is a versatile technique for simultaneous detection of all bovine tick-borne protozoan parasites. We recommend its use for integrated epidemiological monitoring of tick-borne disease, since RLB can also be used for screening ticks and can easily be expanded to include additional hemoparasite species.

Tick-borne protozoan diseases (e.g., theileriosis and babesiosis) pose important problems for the health and management of domestic cattle in the tropics and subtropics (24). The most widespread and malignant Theileria species is Theileria annulata, causing tropical theileriosis, which occurs around the Mediterranean basin, in the Middle East, and in Southern Asia. The other malignant Theileria species is T. parva, which occurs in East and Southern Africa and causes East Coast fever. Bovine babesiosis is caused by Babesia bovis and B. bigemina, both of which occur worldwide in tropical and subtropical regions. B. divergens occurs in cattle in Europe and extends into North Africa (4). In addition, benign forms of theileriosis are caused by T. mutans, T. velifera, and T. taurotragi, which are mainly located in Africa, whereas parasites of the T. sergenti-T. buffeli-T. orientalis group, referred to below as the T. orientalis group, occur worldwide (45).

Several techniques for detection of these hemoparasites have been developed separately for each species (reviewed in reference 17). For the T. orientalis group, several sensitive PCR assays based on the gene encoding the major piroplasm surface protein have been developed (27, 42). A similar approach using the Tams1 gene was followed for T. annulata (13). PCR detection of T. parva using repetitive DNA sequences or gene-specific primers has also been developed (2). Sensitive PCR methods are available for B. bovis (6) and B. bigemina (15) but not yet for B. divergens. Assays to differentiate Theileria species on the basis of their rRNA genes have been described by Allsopp et al. (1) and Bishop et al. (3), but these assays did not include all Theileria species. Moreover, these assays were developed merely for the differentiation of species rather than for detection in carrier animals. To date, screening for the presence of benign Theileria species, such as T. mutans, T. velifera, and T. taurotragi, occurring in cattle depends on the immunofluorescent antibody test and may give rise to cross-reactions (36). Moreover, since serodiagnosis does not detect the parasite itself, the animal may have already cleared the pathogen but remained seropositive. The first integrated approach to sensitive detection and differentiation of B. bigemina, B. bovis, and Anaplasma marginale in a 16S–18S rRNA gene multiplex PCR was reported by Figueroa et al. (16).

Despite the usefulness of these assays, it would be very practical to have a universal test to simultaneously detect and differentiate all protozoan parasites that could possibly be present in the blood of carrier cattle. A reverse line blot (RLB) technique fulfilling these criteria has recently been developed to detect four different Borrelia species in ticks (39). RLB was initially developed as a reverse dot blot assay for the diagnosis of sickle cell anemia (40), but the essence of both techniques is the hybridization of PCR products to specific probes immobilized on a membrane in order to identify differences in the amplified sequences. In the “line” approach, multiple samples can be analyzed against multiple probes to enable simultaneous detection. This approach was initially developed for the identification of Streptococcus serotypes (26), followed by an RLB for Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain differentiation (25).

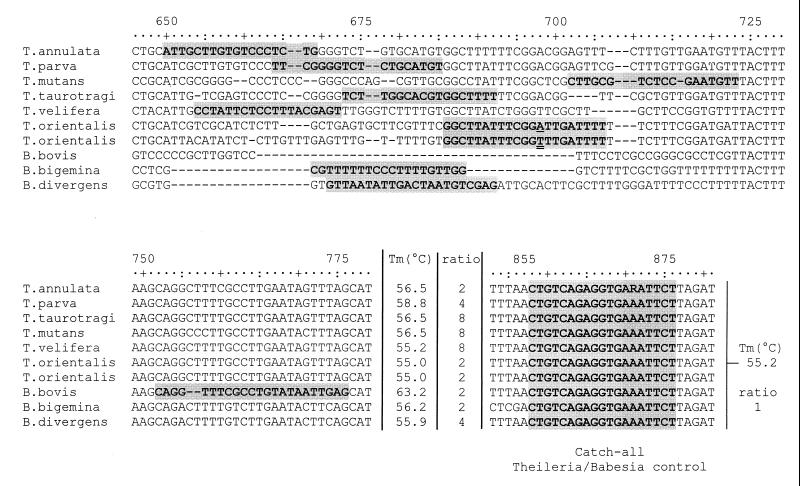

In this study we used RLB to detect and differentiate all known Theileria and Babesia species of importance in cattle in the tropics and subtropics on the basis of their differences in 18S small-subunit (SSU) rRNA gene sequences (Fig. 1). The conserved domains of the 18S rRNA genes of Theileria and Babesia species were used to amplify the hypervariable V4 region by PCR. Within this region, oligonucleotides were deduced for species-specific detection. For most species one or more sequences were available from GenBank, whereas the 18S rRNA gene of T. velifera needed to be cloned and sequenced. Since the 18S rRNA gene is reported to be variable in the T. orientalis group (8) and also in T. mutans (1a), their species-specific oligonucleotides were deduced after cloning and sequencing of the 18S rRNA gene of two isolates of each species. The six Theileria species included in the assay are T. annulata, T. parva, T. mutans, T. taurotragi, T. velifera, and the T. orientalis group. The three Babesia species included are B. bovis, B. bigemina, and B. divergens. A catchall Theileria and Babesia species control oligonucleotide is also included.

FIG. 1.

Locations of species-specific oligonucleotides (shaded) in the 18S rRNA V4 hypervariable region. The first T. orientalis isolate listed is type D (underlined A at position 668), and the second is the T. orientalis isolate described as T. buffeli Warwick (double-underlined T at position 668). A mix of these two oligonucleotides was used on the blot. The melting temperature (Tm) of each oligonucleotide is indicated. The ratio of each oligonucleotide to the catchall Theileria and Babesia oligonucleotide (a ratio of 1 correspond to 200 pmol) is also indicated. The catchall Theileria and Babesia oligonucleotide is identical for all 10 sequences. The R at position 871 in the T. annulata sequence denotes either an A or a G.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

GenBank accession numbers of sequences used.

The GenBank accession numbers of the 18S sequences used for deducing PCR oligonucleotides and specific RLB oligonucleotides are as follows: for T. annulata, M64243; for T. parva, L02366 and AF013418; for T. taurotragi, L19082; for T. orientalis, U97047 (type A), U97048 (type B), U97049 (type B1), U97051 (type C), U97052 (type D), U97053 (type E), U97050 (type H), AB000274 (Medon, Indonesia), AB000273 (Ipoh, Malaysia), AB000272 (Warwick, Australia), AB000271 (Ikeda, Japan), and Z15106 (Marula, Kenya); for B. bigemina, X59604 (gene A), X59605 (gene B), and X59607 (gene C); for B. bovis L31922, L19077, L19078, and M87566; and for B. divergens, U07885, U16370, and Z48751.

Parasite stocks.

Parasite stocks used in this study and previously described are listed in Table 1, whereas those not previously described are given here. Trypanosoma congolense was isolated in Harare, Zimbabwe, from a dog in 1986. B. divergens was isolated from Bos taurus cattle in 1969 in Putten, The Netherlands, and B. major was also isolated in The Netherlands, on the island of Ameland, in 1977 from Haemaphysalis punctata ticks. B. bovis was received from E. Pipano in Israel as vaccine strain C61411. The B. bovis E strain was isolated from cattle in Australia and received in 1988.

TABLE 1.

Origin and nature of parasite stocks

| Genus and species | Stock origin

|

Reference | Material | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Location or name | |||

| Theileria annulata | Turkey | Ankara | 41 | Blood |

| Spain | Cáceres | 11 | Culture | |

| India | Hissar | 18 | Blood | |

| Mauritania | Nouakchott | 21 | Blood | |

| Sudan | Soba | 33 | Culture | |

| Portugal | Évora | 13 | Blood | |

| Bahrain | Bahrain | 49 | Culture | |

| Theileria parva | Kenya | Muguga | 5 | Blood |

| Tanzania | Pugu 1 | 46 | Blood | |

| Theileria taurotragi | Zimbabwe | McIlwaine | 46 | GUTS |

| Theileria velifera | Tanzania | Lugurni | 43 | Blood |

| Theileria mutans | Nigeria | Katsina | 37 | Blood |

| Tanzania | Pugu | 44 | Blood | |

| Theileria orientalis | Australia | Brisbane | 48 | Blood |

| England | Essex | 34 | Blood | |

| Iran | Teheran | 47 | Blood | |

| Japan | Fukushima | 20 | Blood | |

| South Korea | Jeju | 48 | Blood | |

| United States | Texas | 29 | Blood | |

| China | Unknown | 22 | Blood | |

| China | North-West | 38 | Blood | |

| Babesia bigemina | Nigeria | Runka | 31 | Blood |

| Babesia bovis | Israel | C61411 | Culture | |

| Australia | E-strain | Blood | ||

| Babesia divergens | The Netherlands | Putten | Blood | |

| Babesia major | The Netherlands | Ameland | Blood | |

| Trypanosoma vivax | Nigeria | Yakawanda | 30 | Blood |

| Trypanosoma congolense | Zimbabwe | Harare | Blood | |

| Trypanosoma brucei | Ivory Coast | TH114/78E | 14 | Blood |

| Cowdria ruminantium | Senegal | Niaye | 23 | Culture |

| Anaplasma marginale | Nigeria | Zaria | 12 | Blood |

| Ehrlichia canis | United States | Florida | 35 | Blood |

Experimental infections.

Experimental infections with one or more parasite stocks were conducted in female Friesian holstein calves of 8 months of age. Monitoring and blood sample storage were performed essentially as described previously (13). Daily rectal temperatures were recorded, and Giemsa-stained blood smears and lymph node biopsy smears were examined. Serum samples for serodiagnosis and citrate-blood samples for PCR were stored at −20°C. Six animals were initially infected with 1 ml of a ground-up tick supernatant (GUTS) stabilate of T. annulata (India). The animals received a second infection 8 weeks later with 2-ml frozen blood stabilates of either T. mutans (Nigeria), T. orientalis (Japan), T. orientalis (Australia), B. bovis (E strain, Australia), B. bigemina (Nigeria), or B. divergens (The Netherlands). The B. bovis infection was treated with Imidocarb at day 7 postinfection (p.i.).

Processing of samples for PCR.

The DNAs of T. taurotragi, T. parva, T. velifera, T. mutans, B. bovis, B. bigemina, B. divergens, B. major, and all T. orientalis stocks, except the stocks from China, were extracted from EDTA-blood samples that had been stored in liquid nitrogen. Samples of the T. orientalis stocks from China were prepared from purified merozoites. Samples of T. annulata from Turkey, Portugal, Mauritania, and India were prepared from citrate-buffered blood samples collected from experimentally infected calves. Samples were processed as previously described (13). Briefly, 200-μl samples were washed three times with 0.5 ml of lysis mixture (0.22% NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.015% saponin) by centrifugation at maximum speed for 5 min, resuspended in 100 μl of PCR mixture (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 50 mM KCl, 0.5% Tween 20, 100 μg of proteinase K/ml), and incubated overnight at 56°C. Prior to PCR, samples were heated for 10 min at 100°C and centrifuged for 2 min.

Blood samples from cattle in Spain.

Heparin-blood samples were collected in the province of Toledo, central Spain, from 28 Charolais cattle (male and female) ranging in age from 1 month to 7 years. The samples required a proteinase K treatment overnight at 72°C in order to inactivate PCR-inhibiting components. EDTA-blood samples were collected in the province of Càdiz, in the south of Spain, from 17 female Charolais-Retinta crossbred cattle. Their ages ranged from 6 months to 3 years. EDTA-blood samples were processed according to standard procedures as described above.

Cloning and sequencing of 18S genes.

A PCR product of approximately 1,750 bp was amplified with primer A and primer B, amplifying eukaryotic 18S genes, as described previously (32). The product was directly cloned into the pCR2.1 vector according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Leek, The Netherlands). Clones from four independent PCRs were sequenced with a Pharmacia Biotech (Uppsala, Sweden) T7 sequencing kit. The sequences were analyzed by alignment using the Multalin program (10). Only the hypervariable V4 regions of both T. mutans isolates and both Chinese T. orientalis isolates were sequenced on both strands, whereas the full-length sequence of T. velifera was determined.

PCR.

One set of primers was used to amplify a 460- to 520-bp fragment of the 18S SSU rRNA spanning the V4 region. The forward primer, RLB-F (5′-GAGGTAGTGACAAGAAATAACAATA-3′), and the reverse primer, RLB-R (biotin-5′-TCTTCGATCCCCTAACTTTC-3′), hybridized with regions conserved for Theileria and Babesia. RLB-F corresponds to nucleotides 437 to 461, and RLB-R corresponds to nucleotides 920 to 939, of the T. annulata 18S rRNA gene sequence (accession no. M64243). Primers were obtained from Isogen (Maarssen, The Netherlands). Reaction conditions in a 100-μl volume were as follows; 1× PCR buffer (Promega, Madison, Wis.), 1.5 mM MgCl2 (Promega), 200 μM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Pharmacia Biotech), 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (Promega), 100 pmol of each primer, and 20 μl of purified DNA sample. The reactions were performed in an automated DNA thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) for 40 cycles. Each cycle consisted of a denaturing step of 1 min at 94°C, an annealing step of 1 min at 50°C, and an extension step of 1.5 min at 72°C. A final extension step of 10 min at 72°C completed the program.

RLB hybridization.

All the specific oligonucleotides shown in Fig. 1 contained an N-terminal N-(trifluoracetamidohexyl-cyanoethyl,N,N-diisopropyl phosphoramidite [TFA])-C6 amino linker (Isogen). The quality of the TFA linker is crucial and varies among the different oligonucleotide-producing companies. A Biodyne C blotting membrane (Pall Biosupport, Ann Arbor, Mich.) was activated by a 10-min incubation in 10 ml of 16% (wt/vol) 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylamino-propyl)carbodiimide (EDAC) (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) at room temperature. The membrane was washed for 2 min with distilled water and placed in an MN45 miniblotter (Immunetics, Cambridge, Mass.). Specific oligonucleotides were diluted to a 200- to 1,600-pmol/150 μl concentration in 500 mM NaHCO3 (pH 8.4) and were subsequently covalently linked to the membrane with the amino linker by filling the miniblotter slots with the oligonucleotide dilutions; they were then incubated for 1 min at room temperature. The oligonucleotide solutions were aspirated, and the membrane was inactivated by incubation in 100 ml of a 100 mM NaOH solution for 10 min at room temperature. The membrane was washed with shaking in 125 ml of 2× SSPE–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) for 5 min at 60°C (20× SSPE contains 360 mM NaCl, 20 mM NaH2PO4, and 2 mM EDTA [pH 7.4]). Before use, the membrane was washed for 5 min at 42°C with 125 ml of 2× SSPE–0.1% SDS and placed in the miniblotter with the slots perpendicular on the previously applied specific oligonucleotides. A volume of 40 μl of PCR product was diluted to an end volume of 150 μl of 2× SSPE–0.1% SDS, heated for 10 min at 100°C, and cooled on ice immediately. Denatured PCR samples were applied into the slots and incubated for 60 min at 42°C. PCR products were aspirated, and the blot was washed twice in 125 ml of 2× SSPE–0.5% SDS for 10 min at 42°C with shaking. Subsequently the membrane was incubated in 10 ml of 1:4,000-diluted peroxidase-labeled streptavidin (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) in 2× SSPE–0.5% SDS for 30 min at 42°C. The membrane was washed twice in 125 ml of 2× SSPE–0.5% SDS for 10 min at 42°C with shaking. After two rinses in 125 ml of 2× SSPE for 5 min each time at room temperature, an incubation for 1 min in 10 ml of ECL detection fluid (Amersham, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) followed before exposure to an ECL hyperfilm (Amersham) for 10 to 60 min. After use, all PCR products were stripped from the membrane by two washes in 1% SDS for 30 min each time at 80°C. The membrane was rinsed in 20 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) and stored in fresh EDTA solution at 4°C for reuse.

Sensitivity of the RLB assay.

To determine the detection limit of the RLB assay, citrate-buffered blood obtained from an animal infected with T. annulata (India) with a parasitemia of 3.9% was serially diluted with blood of a noninfected animal and processed as described above. In order to establish the exact level of parasitemia in the diluted samples, the packed cell volume of both infected and uninfected blood was measured.

Possible competition between T. annulata and B. bovis in the RLB assay was determined by addition of serial dilutions of T. annulata DNA (0, 0.1, 1.0, 10, 100, 1,000, and 10,000 pg) to a fixed amount of 500 fg of B. bovis DNA. As controls, the same dilutions of T. annulata DNA in the absence of B. bovis DNA were analyzed.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 18S sequences determined in this study for T. velifera and T. orientalis (northwest China) have been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF097993 and AF036336, respectively.

RESULTS

18S sequences.

The 18S rRNA gene of T. velifera was PCR amplified with general 18S primers, cloned, and sequenced, and its relation with the other Theileria species was determined (data not shown). Possible variation of 18S rRNA gene sequences within T. mutans was determined by sequencing the 18S V4 hypervariable regions of two different isolates (see Table 1). Both isolates contained sequences similar to the partial T. mutans 18S sequence previously reported (1). Variation in 18S between different isolates of the T. orientalis group was confirmed by sequencing two isolates from China (see Table 1). The isolate from northwestern China was identical to the formerly described type D, and the other isolate from China, originally named T. sergenti, was identical to the formerly described type A (8).

RLB specific oligonucleotides.

For each species a specific oligonucleotide was deduced in the amplified V4 region, with a melting temperature between 55.0 and 58.8°C, enabling simultaneous hybridization (Fig. 1). The B. bovis oligonucleotide had a slightly higher melting temperature (63.2°C), since an oligonucleotide with a higher melting temperature was required for adequate detection of this parasite. As a control, a catchall Theileria and Babesia species oligonucleotide was also designed in a similar way (Fig. 1). This oligonucleotide was also included in case a PCR product would not hybridize with any of the species included, indicating the presence of an unknown or unexpected species. Since high 18S rRNA gene variation occurs in the T. orientalis group (8), the specific primer for these parasites is a mixture containing either an A or a T at position 13, corresponding with position 658 in the alignment (Fig. 1). The location of the oligonucleotide was conserved in all members of this group and could differentiate them from all the other parasite species (Fig. 2). For each oligonucleotide the relative reaction was optimized by varying the amount of the oligonucleotide applied on the membrane in such a way that all oligonucleotides resulted in equally intense signals relative to the catchall Theileria and Babesia control oligonucleotide. These amounts are indicated in Fig. 1.

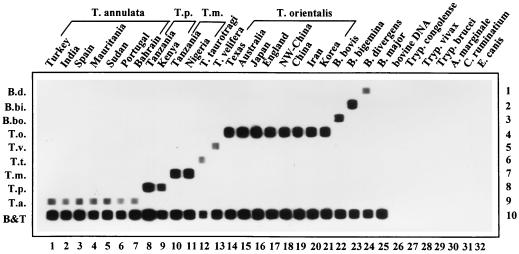

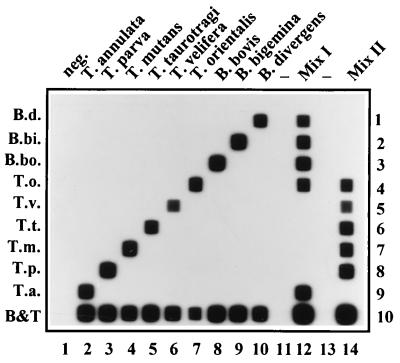

FIG. 2.

RLB of PCR products obtained from Theileria, Babesia, and other bovine hemoparasite samples. PCR products are applied in vertical lanes. Species-specific oligonucleotides are applied in horizontal rows. Lanes 1 to 7, T. annulata isolates from Turkey (lane 1), India (lane 2), Spain (lane 3), Mauritania (lane 4), Sudan (lane 5), Portugal (lane 6), and Bahrain (lane 7); lanes 8 and 9, T. parva isolates from Tanzania and Kenya, respectively; lanes 10 and 11, T. mutans isolates from Tanzania and Nigeria, respectively; lane 12, T. taurotragi; lane 13, T. velifera; lanes 14 to 21, T. orientalis isolates from Texas (lane 14), Australia (lane 15), Japan (lane 16), England (lane 17), northwest China (lane 18), China (lane 19), Iran (lane 20), and Korea (lane 21); lane 22, B. bovis; lane 23, B. bigemina; lane 24, B. divergens; lane 25, B. major; lane 26, bovine DNA; lane 27, Trypanosoma congolense; lane 28, Trypanosoma vivax; lane 29, Trypanosoma brucei; lane 30, A. marginale; lane 31, Cowdria ruminantium; lane 32, Ehrlichia canis. Rows: 1, B. divergens; 2, B. bigemina; 3, B. bovis; 4, T. orientalis; 5, T. velifera; 6, T. taurotragi; 7, T. mutans; 8, T. parva; 9, T. annulata; 10, catchall Theileria and Babesia control oligonucleotide.

RLB.

RLB-PCR was performed on all Theileria and Babesia species listed in Table 1 except the B. bovis E strain from Australia. PCR products were hybridized to the membrane and were shown to bind with the specific oligonucleotides only (Fig. 2). Seven T. annulata isolates, two T. parva isolates, two T. mutans isolates, and eight T. orientalis isolates were detected (Fig. 2). Furthermore, in Fig. 2, row 10, the catchall Theileria and Babesia control oligonucleotide reacted with all parasite isolates. Each species isolate was recognized by its corresponding oligonucleotide only, and cross-reactions between species were not observed.

RLB-PCR performed on DNA from Trypanosoma spp., DNA from Ehrlichia spp., and bovine DNA did not yield detectable products on agarose gels (data not shown). When these PCR products were applied onto the RLB membrane (Fig. 2, lanes 26 to 32), no reaction with any oligonucleotide was observed. However, the presence of DNA in these samples was demonstrated by successful amplification using specific PCR assays for each Trypanosoma species (9) as well as for the ehrlichial organisms (28) (data not shown).

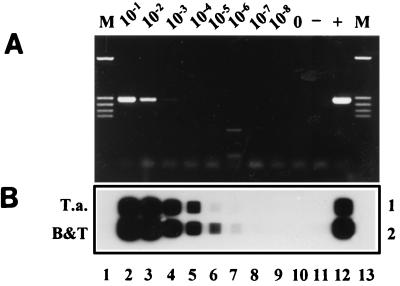

RLB sensitivity.

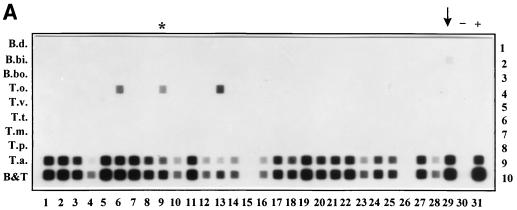

After an acute Theileria or Babesia infection, parasitemias usually drop to a very low level and the animal becomes a carrier. The sensitivity of the RLB assay to detect such carrier animals was determined by using infected blood from an animal with a known level of T. annulata parasitemia serially diluted with blood from a noninfected animal. The resulting PCR is shown in Fig. 3A, wherein a signal can be discerned down to a parasitemia level of 10−3%. The corresponding RLB is shown in Fig. 3B, wherein the lowest detectable parasitemia is 10−6%, corresponding to 3 parasites per μl of blood.

FIG. 3.

Sensitivity of the PCR and the RLB assay. (A) PCR using RLB-F and RLB-R primers on DNA extracted from serial dilutions of T. annulata-infected blood. Lanes 1 and 13, molecular size markers; lanes 2 to 9, PCR products derived from DNA extracted from serial dilutions representing 10−1, 10−2, 10−3, 10−4, 10−5, 10−6, 10−7, and 10−8% parasitemia, respectively; lane 10, 0% parasitemia; lane 11, distilled water control (−); lane 12, PCR positive control of 10 ng of genomic DNA of T. annulata (+). (B) Corresponding RLB of PCR products derived from DNA extracted from serial dilutions of T. annulata-infected blood. Lanes 2 to 12 are identical to lanes 2 to 12 in panel A; lanes 1 and 13 are empty. Rows 1 and 2, T. annulata-specific and catchall Theileria and Babesia control oligonucleotides, respectively.

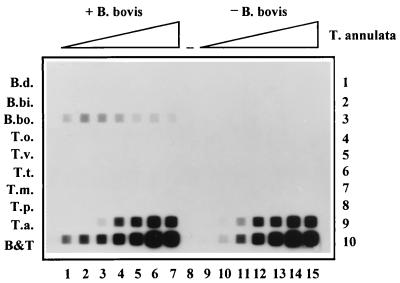

Blood samples containing two parasite species each were also tested. It can be imagined that the predominance of one parasite can influence the results of the RLB-PCR, since both parasites may compete for the available primers in the PCR. An experiment was designed wherein purified genomic T. annulata DNA was added in serial dilution to an amount of purified genomic B. bovis DNA just above the detection limit (Fig. 4). The B. bovis signal was found in all samples (Fig. 4, lanes 1 to 7) and varied slightly, although it was added to the master mix containing all components except the T. annulata DNA. It is, however, clear that the B. bovis signal was not reduced even in the presence of a 500,000-fold excess of T. annulata DNA.

FIG. 4.

Competition between B. bovis and T. annulata DNAs in the RLB-PCR. Lanes 1 to 7 each contain 500 fg of B. bovis DNA, as well as T. annulata DNA in the following amounts: 0 pg (lane 1), 0.1 pg (lane 2), 1.0 pg (lane 3), 10 pg (lane 4), 0.1 ng (lane 5), 1.0 ng (lane 6), and 10 ng (lane 7). Lane 8 is empty (−). Lanes 9 to 15 contain the amounts of T. annulata DNA present in lanes 1 to 7, respectively, but no B. bovis DNA. Rows are identical to those in Fig. 2.

Detection of mixed parasites.

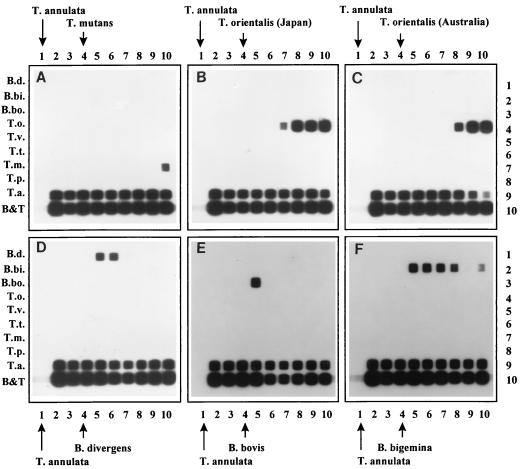

In order to mimic field situations, two mixtures of DNAs from parasites that are known to occur in the same region were prepared and subsequently tested in the RLB. Mixture I contained T. annulata, T. orientalis, B. bovis, B. bigemina, and B. divergens (parasites that occur, for instance, in North Africa, Southern Europe, and the Middle East). Mixture II contained T. parva, T. mutans, T. taurotragi, T. velifera, and T. orientalis (parasites that occur in East and Southern Africa). Figure 5 shows the results of both mixes, together with the signal obtained with each parasite separately. All parasites in both mixtures are detected simultaneously, and no cross-reactions occur (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

RLB of mixed DNA samples from parasites that occur in the same region. Lane 1, distilled water control (neg.); lanes 2 through 10, as labeled; lane 12, mix I, containing T. annulata, T. orientalis, B. bovis, B. bigemina, and B. divergens; lane 14, mix II, containing T. parva, T. mutans, T. taurotragi, T. velifera, and T. orientalis. Lanes 11 and 13 are empty (−). Rows are identical to those in Fig. 2.

Detection of multiple parasites in experimentally infected cattle.

Animals were infected with T. annulata followed by infection with a second Theileria species or a Babesia species. Blood samples were tested before infection, during the clinical manifestation of T. annulata, and during the second infection. Sampling was carried out on a weekly basis until 7 weeks p.i. Reactions in the RLB for these animals are shown in Fig. 6. T. annulata was readily detected at all times. In the coinfection with T. mutans, the T. mutans signal was present only at 7 weeks p.i. (Fig. 6A, lane 10). Coinfection with one of the two T. orientalis isolates resulted in strong T. orientalis signals in all animals from week 3 and week 4 p.i. until week 7 p.i. for the Japanese and the Australian isolate, respectively (Fig. 6B and C). B. divergens coinfection was usually detectable only during the clinical manifestation of this parasite (Fig. 6D). However, additional samples were positive between days 25 and 28 p.i. (data not shown). The secondary B. bovis infection was readily detected before treatment with Imidocarb but disappeared after treatment (Fig. 6E). B. bigemina coinfection was detected from 1 week p.i. until week 6 p.i., although only a very faint signal was found at week 5 p.i. (Fig. 6F).

FIG. 6.

RLB with PCR products derived from DNA extracted from blood samples from animals infected with two different parasites as indicated. Lane 1, preinfection/day of T. annulata infection (marked by arrow); lane 2, 2 weeks post-T. annulata infection; lane 3, 12 weeks post-T. annulata infection/day of infection with second parasite (marked by arrow); lane 4, 1 week post-second infection; lane 5, 2 weeks post-second infection; lane 6, 3 weeks post-second infection; lane 7, 4 weeks post-second infection; lane 8, 5 weeks post-second infection; lane 9, 6 weeks post-second infection; lane 10, 7 weeks post-second infection. Rows are identical to those in Fig. 2.

Detection of parasites in samples collected from cattle in Spain.

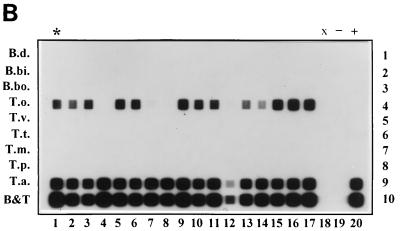

T. annulata was detected in 26 of 28 animals in Toledo (Fig. 7A) and in 17 of 17 animals in Càdiz (Fig. 7B). T. orientalis was detected in 2 of 28 animals in Toledo (Fig. 7A, lanes 6 and 13) and 15 of 17 animals in Càdiz (Fig. 7B, lanes 1 to 6 and 9 to 17), which were all positive for T. annulata as well. One animal in Toledo was positive for both B. bigemina and T. annulata (Fig. 7A; arrow). Two animals in Toledo were completely negative (Fig. 7A, lanes 15 and 26).

FIG. 7.

RLB with PCR products derived from DNA extracted from field samples collected in Spain. (A) Lanes: 1 to 8 and 10 to 29, samples from Toledo; 9, Càdiz sample; 30, PCR distilled water control (−); 31, 10 ng of T. annulata as a positive control (+). The sample positive for both T. annulata and B. bigemina is marked with an arrow. (B) Lanes: 1 to 17, samples from Càdiz; 18, empty (x); 19, distilled water control (−); 20, 10 ng of T. annulata as a positive control (+). The twice-measured Càdiz sample is marked with an asterisk in both blots. Rows are identical to those in Fig. 2.

DISCUSSION

We developed an RLB assay based on the 18S rRNA gene of Theileria and Babesia species infecting cattle mainly in the tropics and subtropics. All species included were detected by a specific oligonucleotide, and no cross-reactions were observed. Neither bovine DNA nor any of the Trypanosoma or Ehrlichia species were detected (although Ehrlichia canis is not a bovine parasite, it was used as a representative, since Ehrlichia bovis was not available). The catchall Theileria and Babesia oligonucleotide control is of importance in case a PCR product is amplified but no specific reaction is seen. This was illustrated by including B. major in the RLB (Fig. 2, lane 25). Similar results could indicate the presence of a novel Babesia or Theileria species or strain or the presence of a known species for which no probe was included. An example of the latter could be B. occultans, which occurs in cattle in Southern Africa (19) but whose 18S rRNA gene sequence is presently unknown. Additional species or strains could be identified by RLB; the PCR product should subsequently be sequenced to identify these organisms, and if necessary, they can be included in the assay.

Although the T. orientalis group is heterogeneous and differences in morphology, pathogenicity, and virulence have been reported (48), we decided to include a catchall T. orientalis oligonucleotide for this group. Recently, heterogeneity was also demonstrated at the 18S rRNA level by Chae et al. (8). Alignments (data not shown) demonstrated that all group members have in common one part of 18S of the V4 region that could differentiate all of them from the other Theileria species. Two representatives of the 13 sequences used for specific oligonucleotide deduction are depicted in Fig. 1. A mix of two oligonucleotides containing either an A or a T at position 668 (Fig. 1) was used to detect all parasites in this group. It was demonstrated that all eight T. orientalis group isolates, of which at least type A (T. orientalis China and Fukushima, Japan; GenBank no. AB016074) and type D (isolate from northwestern China) were tested in our study, hybridized with this oligonucleotide mix.

The sensitivity of the RLB assay was established by testing serial dilutions of T. annulata-infected blood samples; it was determined to be sensitive at 10−6% parasitemia. The corresponding blood sample was 40 μl, which means that the lower detection limit of the assay is approximately 120 parasites. The detection limit of the T. annulata PCR based on the Tams1 gene (13) was 4.8 × 10−5%, which is highly comparable with the sensitivity found for the RLB. For B. bovis, a detection of 10−7 to 10−8% parasitemia was achieved by using 18S PCR and a specific probe followed by very sensitive phosphorimager detection (6). These investigators demonstrated that B. bovis parasitemia fluctuates and sometimes even escapes detection by their assay. Although the RLB assay is less sensitive, detection of B. bovis at time points when the parasitemia rises up to 10−6% is possible.

The DNAs of those parasites that can occur in the same geographical region were mixed and appeared to be equally well amplified (Fig. 5). However, when these parasites are present in very different numbers, another situation arises, since competition for available primers may occur in the PCR. The competition experiment between T. annulata and B. bovis demonstrated that such competition does not occur, at least not between these two parasites (Fig. 4). The absence of competition can be explained by the excess of PCR primers present in the reaction mixture. This was also shown in Fig. 5, wherein parasite DNAs tested separately or mixed resulted in signals of comparable intensity. The effects of competition between multiple parasites present in one sample may therefore not influence the outcome of the RLB, although not all possible combinations were tested.

Furthermore, in experimental animals, T. annulata could be detected simultaneously with T. mutans, T. orientalis, B. divergens, B. bovis, and B. bigemina. After Imidocarb treatment the B. bovis signal was completely lost, confirming the earlier findings of Calder et al. (6). Our B. bigemina results are similar to those obtained with the previously published B. bigemina-specific PCR (15). These authors could detect 10−7% parasitemia, but signals disappeared at some time points in carrier animals. Fluctuating low parasitemia, as was described for B. bovis (6), was probably the reason for the occasional detection of B. divergens (Fig. 6D). Since B. bigemina was readily detected after the acute phase, its level of parasitemia during the carrier state is probably higher than those of B. bovis and B. divergens.

Screening of field samples collected from cattle in two regions in Spain demonstrated the usefulness of the RLB. T. annulata alone or in combination with T. orientalis could be detected in the majority of blood samples. The presence of T. annulata was expected, since this parasite is endemic in Spain (50), but T. orientalis was found for the first time in Spain. T. orientalis does occur elsewhere in Southern Europe, as was recently demonstrated in Italy (7). The presence of B. bigemina in one animal shows that the simultaneous detection of Babesia species is also possible in field samples.

The RLB assay is very practical, since only one PCR is required for simultaneous detection of all Theileria and Babesia parasites. When cattle are screened for their infection status, information can be collected concerning the epidemiology of pathogenic and nonpathogenic parasites, whereby other species-specific PCR assays are superfluous. The membrane with the covalently linked species-specific oligonucleotides can be used at least 20 times, reducing costs for screening animals. Finally, we are now in the process of extending the RLB to include tick-transmitted ehrlichial species such as Cowdria, Anaplasma, and Ehrlichia, which frequently occur simultaneously in the same host animal in the field.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank E. Pipano, Kimron Institute, Beit Dagan, Israel, for providing a strain of Babesia bovis, J. Dawson, CDC, Atlanta, Ga., for the Ehrlichia canis isolate, and Yin Hong and Bai Qi for the T. orientalis isolates from China. A. W. C. A. Cornelissen is thanked for critical reading of the manuscript and for his support for this work.

This work was supported by a grant from the European Community, Directorate General XII, INCO-DC program, contract no. IC18-CT95-0003, entitled “Application of Recombinant DNA Technology to Vaccination, Diagnosis and Epidemiology of Tropical Theileriosis.”

REFERENCES

- 1.Allsopp B A, Bayliss H A, Allsopp M T E P, Cavalier-Smith T, Bishop R P, Carrington D M, Sohanpal B, Spooner P. Discrimination between six species of Theileria using oligonucleotide probes which detect small-subunit ribosomal RNA sequences. Parasitology. 1993;107:157–165. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000067263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1a.Allsopp, P. Unpublished data.

- 2.Bishop R, Sohanpal B, Kariuki D P, Young A S, Nene V, Bayliss H, Allsopp B A, Spooner P R, Dolan T T, Morzaria S P. Detection of a carrier state in Theileria parva-infected cattle by the polymerase chain reaction. Parasitology. 1992;104:215–232. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000061655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bishop R, Allsopp B, Spooner P, Sohanpal B, Morzaria S, Gobright E. Theileria: improved species discrimination using oligonucleotides derived from large-subunit ribosomal RNA sequences. Exp Parasitol. 1995;80:107–115. doi: 10.1006/expr.1995.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouattour A, Darghouth M A. First report of Babesia divergens in Tunisia. Vet Parasitol. 1996;63:161–165. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(95)00880-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brocklesby D W, Barnett S F, Scott G R. Morbidity and mortality rates in East Coast fever (Theileria parva infection) and their application to drug screening procedures. Br Vet J. 1961;117:529–531. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calder J A M, Reddy G M, Chieves L, Courtney C H, Littell R, Livengood J R, Norval R A I, Smith G, Dame J B. Monitoring Babesia bovis infections in cattle by using PCR-based tests. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2748–2755. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.11.2748-2755.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ceci L, Kirvar E, Carelli G, Brown D, Sasanelli M, Sparagano O. Evidence of Theileria buffeli infection in cattle in southern Italy. Vet Rec. 1997;140:581–583. doi: 10.1136/vr.140.22.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chae J, Lee J, Kwon O, Holman P J, Waghela S D, Wagner G G. Nucleotide sequence heterogeneity in the small-subunit ribosomal RNA gene variable (V4) region among and within geographic isolates of Theileria from cattle, elk and white-tailed deer. Vet Parasitol. 1998;75:41–52. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(97)00183-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clausen P-H, Wiemann A, Patzelt R, Kakaire D, Poetzch C, Peregrine A, Mehlitz D. Use of a PCR assay for the specific and sensitive detection of Trypanosoma spp. in naturally infected dairy cattle in peri-urban Kampala, Uganda. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;849:21–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb11029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corpet F. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:10881–10890. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.22.10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Kok J B, d’Oliveira C, Jongejan F. Detection of the protozoan parasite Theileria annulata in Hyalomma ticks by the polymerase chain reaction. Exp Appl Acarol. 1993;17:839–846. doi: 10.1007/BF00225857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Kroon J F, Perié N M, Fransen F F, Uilenberg G. The indirect fluorescent antibody test for bovine anaplasmosis. Vet Q. 1990;12:124–128. doi: 10.1080/01652176.1990.9694255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.d’Oliveira C, van der Weide M, Habela M A, Jacquiet P, Jongejan F. Detection of Theileria annulata in blood samples of carrier cattle by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2665–2669. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2665-2669.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Felgner P, Brinkmann U, Zillmann U, Mehlitz D, Abu-Ishira S. Epidemiological studies on the animal reservoir of gambiense sleeping sickness. Part II. Parasitological and immunodiagnostic examination of the human population. Tropenmed Parasitol. 1981;32:134–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Figueroa J V, Chieves L P, Johnson G S, Buening G M. Detection of Babesia bigemina-infected carriers by polymerase chain reaction amplification. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2576–2582. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.10.2576-2582.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Figueroa J V, Chieves L P, Johnson G S, Buening G M. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction-based assay for the detection of Babesia bigemina, Babesia bovis and Anaplasma marginale DNA in bovine blood. Vet Parasitol. 1993;50:69–81. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(93)90008-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Figueroa J V, Buening G M. Nucleic acid probes as a diagnostic method for tick-borne hemoparasites of veterinary importance. Vet Parasitol. 1995;57:75–92. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(94)03112-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gill B S, Bansal G C, Bhattacharyulu Y, Kaur D, Singh A. Immunological relationship between strains of Theileria annulata Dschunkowsky and Luhs 1904. Res Vet Sci. 1980;29:93–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gray J S, de Vos A J. Studies on a bovine Babesia transmitted by Hyalomma marginatum rufipes Koch, 1844. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1981;48:215–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishihara T, Minami T. Bovine theileriasis and babesiasis in Japan. In: Ishizaki T, Inoki S, Fujita J, editors. Protozoan diseases. Tokyo, Japan: The Japanese-German Association of Protozoan Diseases; 1978. pp. 201–209. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacquiet P, Dia M L, Perié N M, Jongejan F, Uilenberg G, Morel P C. Présence de Theileria annulata en Mauritanie. Revue Elev Méd Vét Pays Trop. 1990;43:489–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jianxum L, Wenshun L. Cattle theileriosis in China. Trop Anim Health Prod. 1997;29:4S–7S. doi: 10.1007/BF02632906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jongejan F, Uilenberg G, Franssen F F J, Gueye A, Nieuwenhuijs J. Antigenic differences between stocks of Cowdria ruminantium. Res Vet Sci. 1988;44:186–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jongejan F, Uilenberg G. Ticks and control methods. Rev Sci Tech Off Int Epizoot. 1994;13:1201–1226. doi: 10.20506/rst.13.4.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamerbeek J, Schouls L, Kolk A, van Agterveld M, Soolingen D, Kuijper S, Bunschoten A, Molhuizen H, Shaw R, Goyal M, van Embden J. Simultaneous detection and strain differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for diagnosis and epidemiology. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:907–914. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.907-914.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaufhold A, Podbieldski A, Baumgarten G, Blokpoel M, Top J, Schouls L. Rapid typing of group A streptococci by the use of DNA amplification and non-radioactive allele-specific oligonucleotide probes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;119:19–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawazu S, Sugimoto C, Kambio T, Fusjiaki K. Analysis of the genes encoding immunodominant piroplasm surface proteins of Theileria sergenti and Theileria buffeli by nucleotide sequencing and polymerase chain reaction. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;56:169–175. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90164-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kock N D, van Vliet A H M, Charlton K, Jongejan F. Detection of Cowdria ruminantium in blood and bone marrow from clinically normal, free-ranging Zimbabwean wild ungulates. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2501–2504. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2501-2504.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuttler K L, Craig T M. Isolation of a bovine Theileria. Am J Vet Res. 1975;36:323–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leeflang P, Buys J, Blotkamp C. Studies on Trypanosoma vivax: infectivity and serial maintenance of natural bovine isolates in mice. Int J Parasitol. 1976;6:413–417. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(76)90027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leeflang P, Ilemobade A A. Tick-borne diseases of domestic animals in Northern Nigeria. II. Research summary, 1966 to 1976. Trop Anim Health Prod. 1977;9:211–218. doi: 10.1007/BF02240342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medlin L, Elwood H J, Stickel S, Sogin M L. The characterisation of enzymatically amplified eukaryotic 16S-like rRNA-coding regions. Gene. 1988;71:491–499. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melrose T R, Brown C G D, Morzaria S P, Ocama J G R, Irvin A D. Glucose phosphate isomerase polymorphism in Theileria annulata and T. parva. Trop Anim Health Prod. 1984;16:239–245. doi: 10.1007/BF02265331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morzaria S P, Barnett S F, Brocklesby D W. Isolation of Theileria mutans from cattle in Essex. Vet Rec. 1974;94:256. doi: 10.1136/vr.94.12.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nyindo M B, Ristic M, Huxsoll D L, Smith A R. Tropical canine pancytopenia: in vitro cultivation of the causative agent Ehrlichia canis. Am J Vet Res. 1971;32:1651–1658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Papadopoulos B, Perié N M, Uilenberg G. Piroplasms of domestic animals in the Macedonia region of Greece. 1. Serological cross-reactions. Vet Parasitol. 1996;63:41–56. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(95)00878-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perié N M, Uilenberg G, Schreuder B E. Theileria mutans in Nigeria. Res Vet Sci. 1979;26:359–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qi B, Guangyuan L, Genfeng H. An unidentified species of Theileria infective for cattle discovered in China. Trop Anim Health Prod. 1997;29:43S–47S. doi: 10.1007/BF02632917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rijpkema S G, Molkenboer M J, Schouls L M, Jongejan F, Schellekens J F. Simultaneous detection and genotyping of three genomic groups of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Dutch Ixodes ricinus ticks by characterization of the amplified intergenic spacer region between 5S and 23S rRNA genes. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3091–3095. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3091-3095.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saiki R K, Chang C-A, Levenson C H, Warren T C, Boehm C D, Kazazian H H, Ehrlich H A. Diagnosis of sickle cell anemia and β-thalassemia with enzymatically amplified DNA and nonradioactive allele-specific oligonucleotide probes. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:537–541. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809013190903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schein E, Büscher G, Friedhoff K T. Lichtmikroskopische Untersuchungen über die Entwicklung von Theileria annulata (Dschunkowsky und Luhs 1904) in Hyalomma anatolicum excavatum (Koch 1844). I. Die Entwicklung im Darm vollgesogener Nymphen. Z Parasitenkd. 1975;48:123–136. doi: 10.1007/BF00389643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanaka M, Onoe S, Matsuba T, Katayama S, Yamanka M, Yonemichi H, Hiramatsu K, Baek B-K, Sugimoto C, Onuma M. Detection of Theileria sergenti infection in cattle by polymerase chain reaction amplification of parasite-specific DNA. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2565–2569. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.10.2565-2569.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uilenberg G, Schreuder B E C. Studies on Theileriidae (Sporozoa) in Tanzania. I. Tick transmission of Haematoxenus veliferus. Tropenmed Parasit. 1976;27:106–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uilenberg G, Schreuder B E C, Mpangala C. Studies on Theileriidae (Sporozoa) in Tanzania. III. Experiments on the transmission of Theileria mutans by Rhipicephalus appendiculatus and Amblyomma variegatum (Acarina, Ixodidae) Tropenmed Parasit. 1976;27:323–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Uilenberg G. Theilerial species of domestic livestock. In: Irvin A D, Cunningham M P, Young A S, editors. Advances in the control of theileriosis. The Hague, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff; 1981. pp. 4–37. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uilenberg G, Perié N M, Lawrence J A, de Vos A J, Paling R W, Spanjer A A M. Causal agents of bovine theileriosis in Southern Africa. Trop Anim Health Prod. 1982;14:127–140. doi: 10.1007/BF02242143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uilenberg G, Hashemi-Fesharki R. Theileria orientalis in Iran. Vet Q. 1984;6:1–4. doi: 10.1080/01652176.1984.9693897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uilenberg G, Perié N M, Spanjer A A M, Franssen F F J. Theileria orientalis, a cosmopolitan blood parasite of cattle: demonstration of the schizont stage. Res Vet Sci. 1985;38:352–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uilenberg G, Franssen F F, Perié N M. Stage-specific antigenicity in Theileria annulata: a case report. Vet Q. 1986;8:73–75. doi: 10.1080/01652176.1986.9694021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Viseras J, García-Fernández P, Adroher F J. Isolation and establishment in in vitro culture of a Theileria annulata-infected cell line from Spain. Parasitol Res. 1997;83:394–396. doi: 10.1007/s004360050270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]