Abstract

BACKGROUND AND AIMS:

Current guidelines recommend surveillance for patients with nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus (NDBE) but do not include a recommended age for discontinuing surveillance. This study aimed to determine the optimal age for last surveillance of NDBE patients stratified by sex and level of comorbidity.

METHODS:

We used 3 independently developed models to simulate patients diagnosed with NDBE, varying in age, sex, and comorbidity level (no, mild, moderate, and severe). All patients had received regular surveillance until their current age. We calculated incremental costs and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained from 1 additional endoscopic surveillance at the current age versus not performing surveillance at that age. We determined the optimal age to end surveillance as the age at which incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of 1 more surveillance was just less than the willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000/QALY.

RESULTS:

The benefit of having 1 more surveillance endoscopy strongly depended on age, sex, and comorbidity. For men with NDBE and severe comorbidity, 1 additional surveillance at age 80 years provided 4 more QALYs per 1000 patients with BE at an additional cost of $1.2 million, whereas for women with severe comorbidity the benefit at that age was 7 QALYs at a cost of $1.3 million. For men with no, mild, moderate, and severe comorbidity, the optimal ages of last surveillance were 81, 80, 77, and 73 years, respectively. For women, these ages were younger: 75, 73, 73, and 69 years, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS:

Our comparative modeling analysis illustrates the importance of considering comorbidity status and sex when deciding on the age to discontinue surveillance in patients with NDBE.

Keywords: EAC, Esophageal Cancer, Stop Age, CEA

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is the only known precursor lesion for esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC).1 Patients with BE have a 10-–55-fold higher risk of developing EAC than the general population. Fortunately, BE surveillance and early detection and treatment of dysplasia may avert EAC development.2 Generally, guidelines in the United States recommend endoscopic eradication therapy (EET) for high-risk patients (ie, patients with low-grade dysplasia [LGD] or high-grade dysplasia [HGD]). Furthermore, they recommend endoscopic surveillance every 3–5 years for nondysplastic BE (NDBE) patients, who are at a lower risk of developing EAC than those with dysplasia. However, there is no recommendation for the age to discontinue surveillance.3–6

The expected benefits of surveillance diminish with advancing age and greater comorbidity due to lower life expectancy. For example, US men without comorbidities at age 68 have a life expectancy of 14.7 years, whereas US men with severe comorbidities at age 80 have a life expectancy of 5.3 years (Table 1).7,8 Therefore, the harms of endoscopic surveillance (eg, complications, false-positive results, and overtreatment) might outweigh the benefits (eg, deaths averted) for some patient populations. Patients with NDBE constitute about 90% of the total BE population.9 Additional surveillance endoscopies, particularly for this population, increase the cost of the surveillance program considerably, and continuation at older ages may, therefore, not be cost-effective.

Table 1.

Overview of Comorbidity Levels, Associated Conditions, and Life Expectancies at Selected Ages 68, 74, and 80 Years in Men

| Comorbidity level | Conditions included | Life expectancy, y |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At age 68 | At age 74 | At age 80 | ||

| No | None of the conditions listed for mild, moderate, or severe | 14.7 | 11.5 | 8.5 |

| Mild | History of myocardial infarction, ulcer, or rheumatologic disease | 13.7 | 11.0 | 8.0 |

| Moderate | Peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, paralysis, diabetes, or combinations of mild conditions | 12.8 | 9.8 | 6.9 |

| Severe | AIDS, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cirrhosis, chronic hepatitis, chronic renal failure, dementia, congestive heart failure, or combinations of at least 1 moderate condition (except diabetes) with any mild or moderate condition | 9.7 | 7.3 | 5.3 |

AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

To the best of our knowledge, no prior studies on BE surveillance have investigated the optimal age to discontinue surveillance of patients with NDBE with regard to the comorbidity level of patients. Evaluating the harms and benefits of many different stop ages in a clinical study would both be very costly and very time consuming. Therefore, modeling studies are required to estimate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different stop ages.

In this study, we aimed to determine the optimal age of last surveillance for patients with NDBE by level of comorbidity using a comparative modeling approach.

Methods

We used 3 independently developed simulation models of EAC screening and surveillance that are part of the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) of the National Cancer Institute.

CISNET-EAC Models

We used the following models: (1) Microsimulation Screening Analysis model for esophageal adenocarcinoma (MISCAN-EAC) from Erasmus MC University Medical Center Rotterdam and the University of Utah; (2) Esophageal AdenoCarcinoma Model (EACMo) from the Columbia University Medical Center and Massachusetts General Hospital; and (3) Multistage Clonal Expansion for EAC model from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (MSCE-EAC). Each model was independently calibrated to common calibration targets based on US Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results cancer registry data until 2014.10

In all 3 models, it was assumed that EAC only develops in patients with BE. Healthy (asymptomatic) individuals and individuals with symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease may develop NDBE, which can progress to LGD and then HGD. Patients with BE with HGD may develop preclinical EAC, which can then progress to clinical EAC as symptoms develop. Individuals with clinical EAC may die of the disease with probabilities dependent on age and stage. More details on the structure and quantifications of the models have been published and are available online.9,11,12

Simulated Population and Intervention

For the base case, we simulated 200 cohorts of US patients diagnosed with NDBE, and followed them until death or age 100 years. Each cohort was defined by a unique combination of starting age (66–90 years), sex (man or woman), and comorbidity level (none, mild, moderate, or severe) (Table 1). EACMo and MSCE-EAC models simulated approximately one million patients in each cohort, and the MISCAN model simulated 265,000 patients. However, the results are reported per 1000 patients diagnosed with NDBE.

We used the cancer-free age, sex, and comorbidity-specific life tables from Lansdorp-Vogelaar et al7,8 and adjusted them to additionally include age and sex-specific mortality due to all cancers except esophageal cancers from CDC Wonder.13 Surveillance for patients with NDBE occurred every 3 years after the initial diagnosis, which was assumed to occur between 60 and 62 years of age.

For each cohort, we simulated an additional surveillance at the current age, or no further surveillance. For example, a 70year-old patient with NDBE with a mild comorbidity level either did or did not receive 1 more surveillance at age 70.

Patients who were diagnosed with LGD received a repeat endoscopy with biopsies after 2 months of treatment with highdose proton pump inhibitor to confirm LGD.14,15 Patients with HGD or confirmed LGD received EET followed by surveillance until death. In case of recurrence, patients received radiofrequency ablation (RFA) touch-ups followed by surveillance. The post-treatment surveillance strategies were simulated according to the outcome of initial EET or RFA touch-ups (Supplementary Table 1). Patients with treatment failure or recurrences more than 3 times did not receive additional RFA touch-ups and underwent surveillance until cancer diagnosis or death. Treatment and surveillance assumptions are presented in detail in Supplementary Table 2.

Costs and Utilities

The costs of endoscopies and EETs in $US were estimated using the 2015 reimbursement rates from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.16 The costs and utilities of cancer care by stage at diagnosis and those of complications due to endoscopy and EET were estimated using published literature (Supplementary Table 2).17–23 All costs and utilities were discounted at an annual rate of 3%.24

Outcomes and Analysis

Using the average results of the 3 models for every cohort, we calculated the number of EAC cases, EAC deaths, life years (LYs), and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) with and without 1 more surveillance. To estimate the total costs, we calculated the cost of cancer care, surveillance endoscopies, EETs, RFA touch-ups, and treatment of complications (ie, bleeding, perforation, and stricture) from a third-party payer perspective.

Subsequently, we calculated incremental costs and QALYs gained from 1 additional endoscopic surveillance at the current age versus not performing surveillance at that age, using the average results. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of performing a last surveillance was calculated for all 25 potential stopping ages (66–90 years), and the age with the highest ICER just less than the willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold of $100,000 per QALY gained was considered the optimal age of last surveillance.

Sensitivity Analysis

Separate results of each model function as an independent sensitivity analysis of underlying assumptions for the natural history of EAC. In addition, we simulated cohorts of patients diagnosed with NDBE at ages 50, 51, and 52 or 70, 71, and 72 years in addition to 60, 61, and 62 to evaluate the robustness of our findings. We also simulated cohorts of patients with NDBE who underwent surveillance every 5 years (instead of 3 years) after the initial diagnosis at ages 60–62 years. Furthermore, we considered EAC survival probabilities, endoscopy and EET complication rates, and disutility scores depending on the comorbidity level of patients. For patients without comorbidity, we considered 50% lower complication rates and disutilities, and 10% higher EAC survival than base case, whereas for patients with mild comorbidity, we considered the same values assumed in the base case. For patients with moderate or severe comorbidity, we considered 50% or 100% higher complication rates and disutilities, and 10% or 20% lower EAC survival than base case, respectively.

All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Results

Results for Men

Table 2 presents lifetime net benefits and costs of 1 additional endoscopic surveillance at selected stopping ages of 68, 74, 80, and 86 years. One more surveillance at age 68 in 1000 patients with NDBE without comorbidity prevented 10 more EAC cases than not performing surveillance at that age. Overall, 56 more QALYs were gained at an incremental cost of more than $1 million, resulting in an ICER of $23,600 per QALY, which was well less than the WTP threshold. The same comparison for patients with NDBE with comorbidities showed that 1 additional surveillance at age 68 years prevented fewer EAC cases and deaths, which led to higher net costs and lower QALYs. Nonetheless, the ICERs remained less than the WTP threshold, and surveillance at age 68 was considered cost-effective for patients with NDBE of all comorbidity levels.

Table 2.

Lifetime Net Benefits and Costs of 1 Additional Endoscopic Surveillance, For Example, at Ages 68, 74, 80, and 86 vs Not Performing Surveillance at That Age Per 1000 Men With NDBE

| Age | Comorbidity levela | EAC prevented | EAC death preventedb | QALYs gained | Endoscopies | EET and touch-ups | Net cost ($) | ICER |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 68 | No | 10 | 11 | 56 | 1952 | 81 | 1,328,609 | 23,620 |

| Mild | 9 | 10 | 49 | 1910 | 79 | 1,343,689 | 27,183 | |

| Moderate | 8 | 9 | 44 | 1875 | 78 | 1,360,570 | 30,927 | |

| Severe | 5 | 7 | 28 | 1732 | 73 | 1,393,730 | 49,673 | |

| 74 | No | 6 | 8 | 31 | 1670 | 70 | 1,269,878 | 41,302 |

| Mild | 6 | 7 | 28 | 1650 | 70 | 1,275,048 | 45,230 | |

| Moderate | 5 | 6 | 22 | 1591 | 68 | 1,290,369 | 59,030 | |

| Severe | 3 | 4 | 13 | 1465 | 64 | 1,296,268 | 101,966 | |

| 80 | No | 3 | 5 | 14 | 1401 | 62 | 1,192,137 | 83,986 |

| Mild | 3 | 4 | 12 | 1381 | 61 | 1,195,159 | 96,407 | |

| Moderate | 2 | 3 | 8 | 1322 | 60 | 1,195,875 | 143,993 | |

| Severe | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1220 | 57 | 1,175,899 | 269,344 | |

| 86 | No | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1128 | 55 | 1,083,739 | 254,074 |

| Mild | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1112 | 54 | 1,081,072 | 295,144 | |

| Moderate | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1068 | 53 | 1,072,173 | 482,703 | |

| Severe | 0 | 1 | 0 | 981 | 51 | 1,033,270 | 2,352,232 |

Overview of comorbidity levels and associated conditions can be found in Table 1.

Surveillance of patients with NDBE can prevent EAC deaths in 2 ways: (1) by finding and treating patients with BE with LGD and HGD, this way preventing both EAC incidence and thus EAC death; and 2) by finding and treating EAC early, and this way preventing death from EAC but not EAC incidence. Therefore, the number of prevented deaths due to EAC can be higher than the number of prevented EAC cases.

By increasing the age of the patients with NDBE, the net benefits of 1 additional surveillance decreased, and the ICERs increased accordingly. The ICERs of 1 additional surveillance versus not performing surveillance at ages 74, 80, or 86 years were higher than at age 68 years irrespective of comorbidity level (Table 2). An additional surveillance at age 74 for patients with NDBE with severe comorbidities was not cost-effective, with an ICER greater than $100,000/QALY. Similarly, an additional surveillance at age 80 was not cost-effective for patients with NDBE with moderate or severe comorbidities. At age 86, 1 more surveillance was not cost-effective for any level of comorbidity.

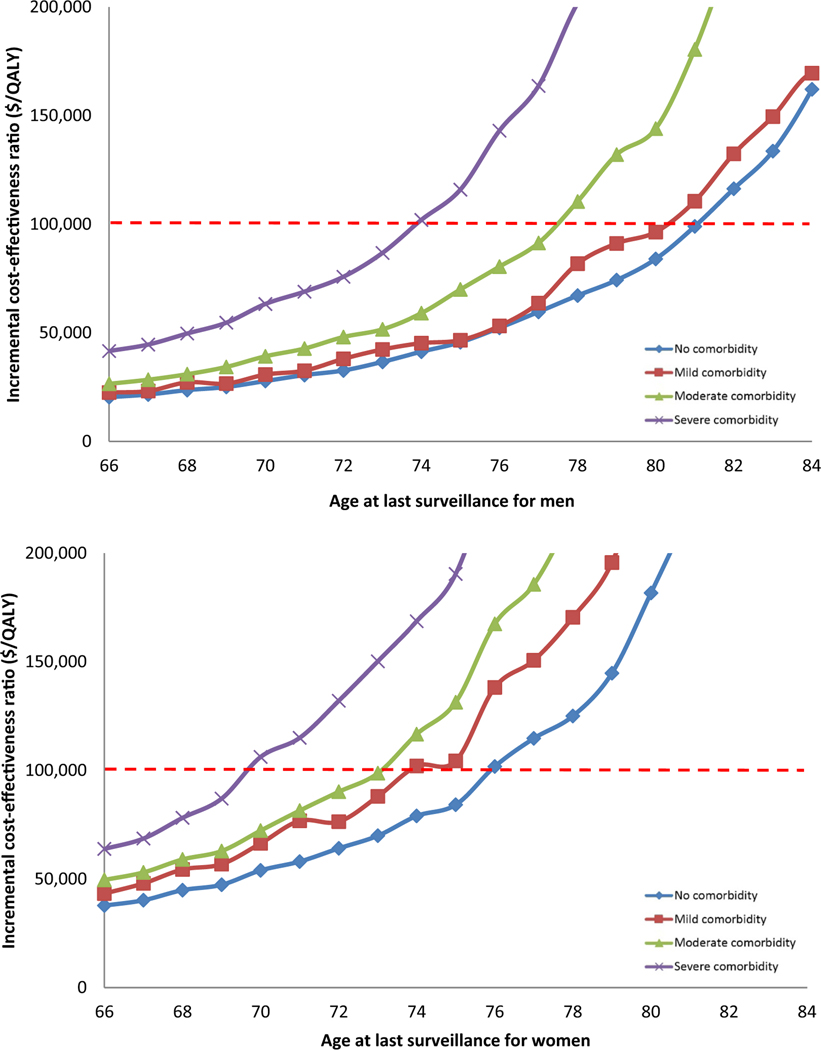

For men without comorbidity, 1 additional surveillance at age 82 years in comparison with not performing surveillance at that age resulted in an ICER of $116,300 per QALY, whereas the same comparison at age 81 years resulted in an ICER of $99,000 per QALY. Therefore, 81 years was considered the optimal age of last surveillance for individuals without comorbidity. For individuals with mild, moderate, and severe comorbidity, the optimal ages of last surveillance using the average results of the 3 models were 80, 77, and 73 years, respectively (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of surveillance of patients with NDBE at different ages by level of comorbidity, men (A) and women (B).

Results for Women

Similar to men, the net benefits of 1 additional surveillance of women with NDBE decreased with increasing age and comorbidity. However, the ICERs of 1 more surveillance in women were generally higher than those for men of similar age and comorbidity status (Supplementary Table 3). For example, surveillance of women aged >75 years was not cost-effective (ICERs >$101,800/QALY) for any level of comorbidity.

Consequently, the optimal ages of last surveillance were lower in women than in men. For women without comorbidity, 75 years was the optimal age of last surveillance with an ICER of $84,200/QALY. Surveillance of patients with higher comorbidity levels resulted in higher ICERs and lower optimal stopping ages. For women with mild and moderate comorbidity, the optimal age of last surveillance was the same: 73 years; however, the ICERs were different ($88,000 vs. $98,700 per QALY, respectively). For women with severe comorbidity, the optimal stopping age was 69 years (Figure 1B).

Sensitivity Analysis

The separate results of each model consistently showed that women had lower optimal ages for last surveillance than men. All 3 models also showed lower optimal stopping ages for patients with higher comorbidity levels. However, the results from the EACMo suggested earlier optimal ages for last surveillance compared with other models, particularly for women with NDBE (Table 3).

Table 3.

The Optimal Age of Last Surveillance Based on Sensitivity Analysis and Comorbidity Level

| Men |

Women |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidity/analysis | No | Mild | Moderate | Severe | No | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

| Base case | 81 | 80 | 77 | 73 | 75 | 73 | 73 | 69 |

| Models | ||||||||

| MISCAN-EAC | 83 | 82 | 79 | 75 | 77 | 74 | 74 | 71 |

| EACMo | 78 | 77 | 74 | 70 | 69 | 66 | ≤65 | ≤65 |

| MSCE-EAC | 81 | 80 | 77 | 75 | 78 | 75 | 74 | 72 |

| NDBE by diagnosis age | ||||||||

| Age 50/51/52 | 81 | 80 | 77 | 74 | 76 | 74 | 73 | 70 |

| Age 70/71/72 | 80 | 79 | 77 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 74 | ≤70 |

| Surveillance every 5 y | 81 | 81 | 78 | 75 | 77 | 75 | 74 | 71 |

| Complicationa rate | 81 | 80 | 77 | 73 | 76 | 73 | 72 | 69 |

| Utility valuesa | 81 | 80 | 77 | 73 | 76 | 73 | 72 | 69 |

| EAC survivala | 80 | 79 | 77 | 74 | 75 | 73 | 73 | 69 |

For patients without comorbidity, we considered 50% less complications and disutilities, and 10% less EAC mortality than base case. For patients with moderate comorbidity, we considered the same as what we assumed in the base case. For patients with moderate or severe comorbidity, we assumed 50% or 100% higher complication rate and disutilities, and 10% or 20% higher EAC mortality rate than base case, respectively.

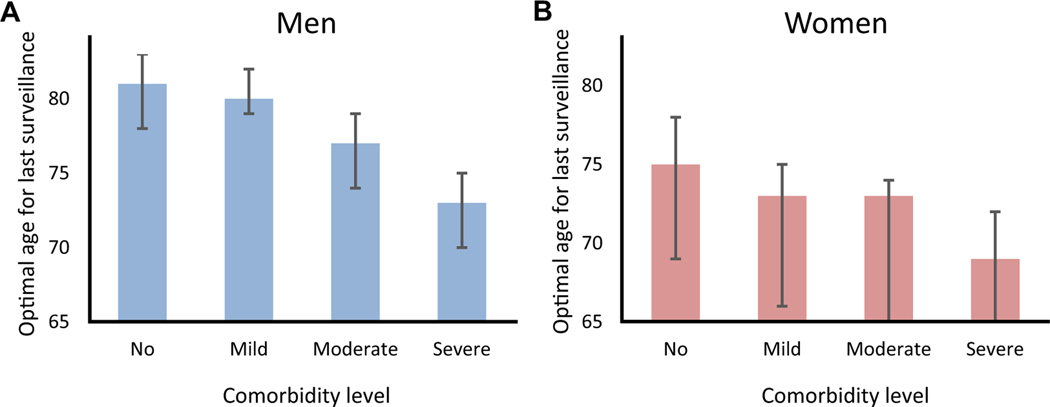

Our results were also robust to surveillance every 5 years, different diagnosis ages, as well as variation in the assumed complication rates, EAC survival probabilities, and utility values by comorbidity level. Only small changes in the optimal age of last surveillance of NDBE patients by these sensitivity analyses were observed (Table 3, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The optimal age of last surveillance for men (A) and women (B) with NDBE. *The error bars present the ranges of surveillance stopping ages between models. The large error bars for women are the result of differences in natural history assumptions between the models. At older ages, the cumulative incidence of EAC in the EACMo is lower than the other 2 models, resulting in an earlier stopping age for women compared with the other 2 models (see Discussion section for more details on model differences).

Discussion

Our comparative modeling analysis indicates that the optimal age for last surveillance of patients with NDBE depends on the sex and the comorbidity level of patients. We found that for men with NDBE without comorbidity, the optimal age for last surveillance is 81 years, whereas it may be up to 8 years earlier for those with comorbidity. For women, we found that without comorbidity, the optimal age for last surveillance of patients with NDBE is 75 years but can be up to 6 years earlier if patients have comorbidities.

Generally, by increasing the age and level of comorbidity of patients, the life expectancy is decreased and consequently, the benefit of surveillance is decreased. Therefore, after a certain age, surveillance of patients with NDBE is no longer cost-effective. Despite having a longer life expectancy, women have a lower optimal age for last surveillance due to a lower lifetime risk of EAC in women than in men. The separate results of each model showed the same patterns. However, the EACMo suggests earlier ages to discontinue surveillance in men and women compared with other models. This discrepancy can be explained by different natural history assumptions between the models. EAC incidence varies by age across the models. At older ages, the cumulative incidence of EAC in the EACMo is lower than the other 2 models. Therefore, patients with NDBE in the EACMo are more likely to die of other causes before progression to EAC occurs. This is the reason that surveillance of patients with NDBE at later ages in the EACMo was not cost-effective, unlike in the other 2 models.

None of the previous analyses examining the cost-effectiveness of surveillance of patients with NDBE evaluated the optimal age to discontinue surveillance.15,25,26 However, we can compare our findings to a previous study evaluating the age of colorectal, prostate, and breast cancer screening cessation based on comorbidity level. This study found that people with higher comorbidity level gained less benefits from cancer screening and suggested to discontinue screening earlier.8 A prior cost-effectiveness analysis also showed that the comorbidity status of individuals undergoing colorectal cancer screening had a large impact on the effectiveness of the screening program. Screening was, therefore, cost-effective up to a lower age for people with comorbidities compared with those without.27

In our base case analysis, we simulated cohorts of patients with NDBE diagnosed at age 60 years, because the mean age of patients with BE at diagnosis has been reported to be older than 60 years.28–30 However, in sensitivity analyses, we assumed a longer interval for surveillance of patients with NDBE, and younger and older ages of diagnosis and varied utility values, complication, and EAC survival probabilities based on the comorbidity status of patients. Our results were quite robust for these external model parameters. However, they depended quite heavily on the model used (ie, on structural model assumptions). The main differences between the models are the time it takes to progress from NDBE to EAC and when BE develops in a patient (ie, how long a patient has lived with BE at the time of diagnosis). Because these patterns are still unknown, future linkage studies with long-term follow-up might help to address these issues. Nevertheless, all 3 models in our study show that surveillance should not continue indefinitely, even in patients without any comorbidity.

Our study has some limitations. We are unaware of life tables for patients younger than 66 years of age with different comorbidity levels and, therefore, we could not determine the optimal age of last surveillance if it was younger than 66 years (for the EACMo, this was the case for women with moderate or severe comorbidity). However, this limitation did not affect our combined results. In addition, due to the limited data, we could not apply the impact of patient comorbidity level on the prognosis of cancer. Furthermore, the utility values used in our analysis are derived from limited available literature that may not accurately represent the value or quality of patients’ lives.

Despite these limitations, our findings have many strengths. The 3 independent models were developed under the auspices of the National Cancer Institute CISNET modeling consortium during the past 10 years with regular meetings lending support to the credibility and prior validation of the models and the comparative modeling process. The largest limitation in simulation modeling is the uncertainty in both model parameter estimates and structure. Our analysis used 3 models, which may provide some reassurance as opposed to the use of 1 model.

In addition, our results have important clinical implications for personalized management of patients with NDBE because none of the gastroenterology scientific societies recommend any stopping age for BE surveillance. For example, our results suggest that performing 1 more surveillance might not be appropriate from a cost-effectiveness perspective for a 76-year-old man with NDBE and severe comorbidity such as congestive heart failure. However, a 76-year-old man without comorbidity may be considered for 1 more surveillance at that age. It is worth mentioning that in addition to monetary costs, surveillance itself can become harmful and preclude increases in QALYs. For example, surveillance of an 85-year-old woman with NDBE and severe comorbidity can result in QALY loss. Empirical evidence has demonstrated that advancing age and more severe comorbidity have very little effect on the decision of whether to perform surveillance endoscopy in Medicare patients with BE.31

Our study was conducted in the US setting, but our findings can be applied to other settings with similarly high incidences of BE and EAC, such as countries in Northern and Western Europe and Oceania, and can inform international guidelines on the optimal age for last surveillance of patients with NDBE.

In conclusion, our comparative modeling approach shows that, in addition to chronological age, sex and the comorbidity status of patients with NDBE are important factors to inform the decision when to discontinue surveillance. Our analysis finds that the optimal age for last surveillance of patients with NDBE without comorbidity for women is 75 years and for men is 81 years. However, it may be up to 6 years earlier for women and up to 8 years earlier for men if patients have severe comorbidities.

Supplementary Material

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW.

BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT

Current guidelines do not specify a recommended age for discontinuing surveillance endoscopy of patients with nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus (NDBE). This study aimed to determine an optimal age for last surveillance of patients with NDBE.

NEW FINDINGS

The optimal age for last surveillance of patients with NDBE without comorbidities for women is 75 years and for men is 81 years. However, it may be up to 6–8 years earlier if patients have severe comorbidities.

LIMITATIONS

Due to limited data, the prognosis of cancer was not varied by patient comorbidity.

IMPACT

Our analysis has important implications for surveillance of patients with NDBE. In addition to chronological age, the comorbidity status and sex of patients are important factors to inform the decision to discontinue surveillance.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr Amy Knudsen, of the Institute for Technology Assessment, Massachusetts General Hospital, for her help on adjustment of life tables.

Funding

This study has been supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (grant numbers U01CA152926 and U01CA199336). The authors also thank the Scientific Computing Infrastructure at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center funded by Office of Research Infrastructure Programs grant S10OD028685.

Conflicts of interest

All authors received funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute for conducting this study.

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- BE

Barrett’s esophagus

- CISNET

Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network

- EAC

esophageal adenocarcinoma

- EACMo

Esophageal AdenoCarcinoma Model

- EET

endoscopic eradication therapy

- HGD

high-grade dysplasia

- ICER

incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

- LGD

low-grade dysplasia

- LY

life year

- MISCAN

Microsimulation Screening Analysis

- MSCE

Multistage Clonal Expansion

- NDBE

nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus

- QALY

quality-adjusted life year

- RFA

radiofrequency ablation

- WTP

willingness-to-pay

Footnotes

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Amir-Houshang Omidvari, MD, PhD (Conceptualization: Equal; Formal analysis: Lead; Project administration: Lead; Validation: Equal; Writing –original draft: Lead).

William D. Hazelton, PhD (Formal analysis: Equal; Validation: Equal; Writing –review & editing: Equal).

Brianna N. Lauren, BS (Formal analysis: Equal; Project administration: Equal; Validation: Equal; Writing –review & editing: Equal).

Steffie K. Naber, PhD (Formal analysis: Supporting; Supervision: Supporting; Visualization: Equal; Writing –review & editing: Equal).

Minyi Lee, BS (Formal analysis: Equal; Writing –review & editing: Equal).

Ayman Ali, BS (Formal analysis: Equal; Writing –review & editing: Equal).

Claudia Seguin, BS (Formal analysis: Equal; Writing –review & editing: Equal).

Chun Yin Kong, PhD (Conceptualization: Equal; Formal analysis: Supporting; Writing –review & editing: Equal).

Ellen Richmond, MS (Formal analysis: Supporting; Resources: Supporting; Writing –review & editing: Equal).

Joel H. Rubenstein, MD, MSc (Conceptualization: Equal; Formal analysis: Supporting; Writing –review & editing: Equal).

Georg E. Luebeck, PhD (Formal analysis: Supporting; Funding acquisition: Equal; Supervision: Equal; Writing –review & editing: Equal).

John M. Inadomi, MD (Conceptualization: Equal; Formal analysis: Supporting; Funding acquisition: Equal; Supervision: Equal; Writing –review & editing: Equal).

Chin Hur, MD, MPH Conceptualization: Equal; Formal analysis: Supporting; Funding acquisition: Equal; Supervision: Equal; Writing –review & editing: Equal).

Iris Lansdorp-Vogelaar, PhD (Conceptualization: Lead; Formal analysis: Supporting; Funding acquisition: Equal; Supervision: Equal; Writing –review & editing: Equal).

Supplementary Material

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at http://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2021.05.003.

References

- 1.Rustgi AK, El-Serag HB. Esophageal carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2014;371:2499–2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thrift AP. Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma: how common are they really? Dig Dis Sci 2018;63:1988–1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Standards of Practice Committee, C, Wani S, Qumseya B, et al. Endoscopic eradication therapy for patients with Barrett’s esophagus-associated dysplasia and intramucosal cancer. Gastrointest Endosc 2018; 87:907–931.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, et al. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:30–50; quiz51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Gastroenterological Association, Spechler SJ, Sharma P, et al. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on the management of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology 2011;140:1084–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, Ragunath K, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut 2014; 63:7–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho H, Klabunde CN, Yabroff KR, et al. Comorbidity-adjusted life expectancy: a new tool to inform recommendations for optimal screening strategies. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:667–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Gulati R, Mariotto AB, et al. Personalizing age of cancer screening cessation based on comorbid conditions: model estimates of harms and benefits. Ann Intern Med 2014;161:104–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kroep S, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Rubenstein JH, et al. An accurate cancer incidence in Barrett’s esophagus: a best estimate using published data and modeling. Gastroenterology 2015;149:577–585.e4; quiz e14–e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NCI. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program population (1969–2013). National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research program, Surveillance Systems branch. Available at: https://seer.cancer.gov/. Accessed June 15, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 11.CISNET esophagus cancer collaborators. EsophagealCancer Model Profiles2018. NIH Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET), 2018. Available at: https://cisnet.cancer.gov/esophagus/profiles.html. Accessed June 15, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kong CY, Kroep S, Curtius K, et al. Exploring the recent trend in esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence and mortalityusing comparative simulation modeling. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014;23:997–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Underlyingcause of death, 1999–2017. Available at: https://wonder.cdc.gov/Deaths-by-Underlying-Cause.html. Accessed June 15, 2021.

- 14.Wani S, Rubenstein JH, Vieth M, et al. Diagnosis and management of low-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: expert review from the Clinical Practice Updates Committee of the American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology 2016;151:822–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Omidvari AH, Ali A, Hazelton WD, et al. Optimizing management of patients with Barrett’s esophagus and low-grade or no dysplasia based on comparative modeling. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;18:1961–1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.2015 GI Endoscopy Coding and Reimbursement Guide. Cook Medical, 2015. Available at: https://www.cookmedical.com/. Accessed June 15, 2021.

- 17.Hur C, Choi SE, Rubenstein JH, et al. The cost effectiveness of radiofrequency ablation for Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology 2012;143:567–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cryer BL, Wilcox CM, Henk HJ, et al. The economics of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a US managed-care setting: a retrospective, claims-based analysis. J Med Econ 2010;13:70–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yabroff KR, Lamont EB, Mariotto A, et al. Cost of care for elderly cancer patients in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:630–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroep S, Heberle CR, Curtius K, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of Barrett’s esophagus reduces esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence and mortality in a comparative modeling analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 15:1471–1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hur C, Nishioka NS, Gazelle GS. Cost-effectiveness of aspirin chemoprevention for Barrett’s esophagus. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004;96:316–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Boer AG, Stalmeier PF, Sprangers MA, et al. Transhiatal vs extended transthoracic resection in oesophageal carcinoma: patients’ utilities and treatment preferences. Br J Cancer 2002;86:851–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garside R, Pitt M, Somerville M, et al. Surveillance of Barrett’s oesophagus: exploring the uncertainty through systematic review, expert workshop and economic modelling. Health Technol Assess 2006;10:1–142; iii–iv. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, et al. Recommendations for conduct, methodological practices, and reporting of cost-effectiveness analyses: second panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. JAMA 2016;316:1093–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gordon LG, Mayne GC, Hirst NG, et al. Cost-effectiveness of endoscopic surveillance of non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc 2014;79:242–256.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kastelein F, van Olphen S, Steyerberg EW, et al. Surveillance in patients with long-segment Barrett’s oesophagus: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Gut 2015; 64:864–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Hees F, Saini SD, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, et al. Personalizing colonoscopy screening for elderly individuals based on screening history, cancer risk, and comorbidity status could increase cost effectiveness. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1425–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Runge TM, Abrams JA, Shaheen NJ. Epidemiology of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2015;44:203–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gatenby P, Caygill C, Wall C, et al. Lifetime risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:9611–9617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rex DK, Cummings OW, Shaw M, et al. Screening for Barrett’s esophagus in colonoscopy patients with and without heartburn. Gastroenterology 2003;125:1670–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rubenstein JH, Noureldin M, Tavakkoli A, et al. Utilization of surveillance endoscopy for Barrett’s esophagus in Medicare enrollees. Gastroenterology 2020;158:773–775.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.