Abstract

The purpose of this article is to report the literature review findings of our larger deprescribing initiative, with the goal of developing a competency framework about deprescribing to be incorporated into the future geriatric nursing education curriculum. A literature review was conducted to examine the facilitators and barriers faced by nurses with regard to the process of deprescribing for older adults, and the development of deprescribing competency in nursing education. We adopted the seven steps of the Comprehensive Literature Review Process Model, which is sub-divided into the following three phases (a) Exploration; (b) Interpretation; and (c) Communication. A total of 24 peer-reviewed documents revealed three major facilitating factors: (a) Effective education and training in deprescribing; (b) Need for continuing education and professional development in medication optimization; and (c) Benefits of multi-disciplinary involvement in medication management.

Keywords: Polypharmacy, Deprescribing, Education, Geriatric nursing, Curriculum

Due to the global rise of life expectancies, along with the increased burden of chronic conditions, especially among the older adult population, the prevalence of polypharmacy poses great concern for health care providers (Dagli & Sharma, 2014). On average, global studies have found that the older adult population take between 2 and 9 medications daily, however, up to 62.5% of this medication has been deemed as inappropriate, harmful, or redundant (Dagli & Sharma, 2014). Many of these medications produce unwanted negative effects called adverse drug reactions (ADRs). Among the vulnerable older adult population, these ADRs can cause a variety of impairments including, but not limited to decreased cognition, dizziness, poor coordination, urinary/fecal incontinence, drug interactions, and allergic reactions (Davies & O’Mahony, 2015). The reduction of polypharmacy prevalence rates, along with a decrease in the associated ADRs can be accomplished through the process of deprescribing. Deprescribing refers to the discontinuation or slow tapering of a medication (Thompson & Farrell, 2013), with the ultimate goal of reducing polypharmacy and ADRs, while improving the overall quality of life of the individual (Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada [ISMP], 2018). Current research suggests that the process of deprescribing not only promotes physical health, but also has a positive impact on the mental, social, and financial aspects of the individual, and the society as a whole (Reeve & Wiese, 2013).

Based on the existing guidelines designated to guide the process of deprescribing, there are recommended goals and actions that highlight the need for nurses to collaborate within the multidisciplinary team to support medication optimization (Harriman et al., 2014). These recommended actions include medication reconciliation, the identification of inappropriate medication, creation of goals and/or plan to either halt or taper off medication with the considerations of patient safety and health, and lastly, proper observation and documentation (Reeve et al., 2014). The recommendation to involve a multidisciplinary team throughout the process of deprescribing is of critical importance (Harriman et al., 2014). Not only does the collaboration improve patient outcomes, but it also enhances communication, organization, and overall understanding of work roles and capabilities (Wang et al., 2015). Nurses, as crucial health care providers, are most directly involved in the daily care of vulnerable populations (i.e., older adults) whether that be in the hospitals, retirement homes, home health care, community settings, or any other geriatric settings. They are responsible for the administration of medications; and due to their active role in direct patient care, they are able to observe the burden and ADRs associated with polypharmacy (Naughton & Hayes, 2016; Sun, Tahsin, Lam, et al., 2019). Nurses play a critical role in their multi-disciplinary involvement to develop relevant goals and actions of deprescribing for their patients to optimize medication management. This includes the identification of inappropriate medication, creation of goals and/or plans to either halt or taper off the medication, proper observation, assessment, and patient teaching (Naughton & Hayes, 2016). However, based on past research, nurses often lack the knowledge (Lim et al., 2010), attitudes, and skills required to successfully support deprescribing practices (Hermanowski et al., 2016; Sun, Tahsin, Barakat-Haddad, et al., 2019). Incorporating deprescribing education at the undergraduate level may provide student nurses with the foundational knowledge related to polypharmacy and medication management, which in turn will equip the prospective nurses in developing the competency needed to advocate for and participate in the deprescribing process in their future practice. As a result, our current project initiative began with the aim to develop a nursing deprescribing competency framework to be incorporated into the nursing education curriculum in geriatric care. The initiative is sub-divided into three phases: (a) Phase I: Identification of key domains of nursing deprescribing practices for older adults by performing a thorough literature review; (b) Phase II: Consolidation and review of the key domains found in Phase I by groups of expert reviewers using the Delphi Panel method (Farrell et al., 2015); and (c) Phase III: Cross-provincial validation survey involving approximately 50–100 stakeholders, and the final results will be analyzed and reviewed before reaching a final consensus on the finalized domains for the deprescribing competency framework in geriatric nursing care.

Purpose

The purpose of this article is to report the findings from “Phase I: Literature Review” of our larger deprescribing initiative. The literature review was conducted to examine the facilitators and barriers faced by nurses with regard to the process of deprescribing for older adults, and the development of deprescribing competency in geriatric nursing education.

Methods

The initial phase of our deprescribing competency framework initiative began by identifying the key domains of deprescribing knowledge and skills for gerontological nurses through a literature review. As a result of the limited availability of existing literature related to the study topic, the purpose of this review is to gain an understanding of the existing literature regarding the topic of interest, rather than a critical appraisal of the available evidence. We adopted the seven steps of the Comprehensive Literature Review Process Model, which is sub-divided into the following three phases (a) Exploration; (b) Interpretation; and (c) Communication (Onwuegbuzie & Frels, 2016). During the exploration, the topic of interest was explored; the search was initiated; information was organized and stored; followed by selecting/deselecting information, as well as expanding the search. The interpretation phase involved the analysis and synthesis of information, while the communication phase involved the development of report about the findings of literature review.

Sample

The initial search revealed that there was a lack of existing data and research on the direct role of nurses in the process of deprescribing. Based on this reason, no specific publication cut-off date was used to narrow down the already limited search about the phenomenon of interest. This literature review involved the range of publication dates that covered from 2005 to 2019. From the search, fully accessible, peer-reviewed articles with relevant keywords were chosen to be included in the review. In addition, non-empirical items such as grey literature, were included as the topic of interest is relatively new and under-studied. Furthermore, non-empirical items could provide a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon of interest. The final review literature consisted of peer-reviewed qualitative and quantitative research articles, as well as review articles and scholarly editorial papers. The review was limited to documents published in English only, although there was no limitation placed on the geographical locations, or health care settings of the relevant literature.

Literature Search

The rationale for the search terms is to address the primary purpose of the literature review, which is intended to identify the nursing role and required competency for facilitating deprescribing. The keywords used in the literature search were “nurses,” “deprescribing,” “nursing,” “polypharmacy,” and “education.” Other keywords used during the search included “elderly,” and “multidisciplinary.” These keywords were used to specify the at-risk older adult populations and settings in which this process is likely to take place for the management of polypharmacy. We searched the databases listed below using the following combination of terms: (nurses* OR nursing* OR “nursing education” OR “geriatric nursing”) AND (deprescribe* OR deprescribing* OR “polypharmacy”) AND (elderly* OR older adult*), primarily from the X database, as well as PubMed, Wiley Library, and Google Scholar. All search engines were used consistently, with the same keywords and inclusion/exclusion criteria. With a combination of the keywords, the initial search yielded a total of 1,643 publications across the databases. The reference lists of relevant literature were scanned for other potentially relevant literature.

Data Management

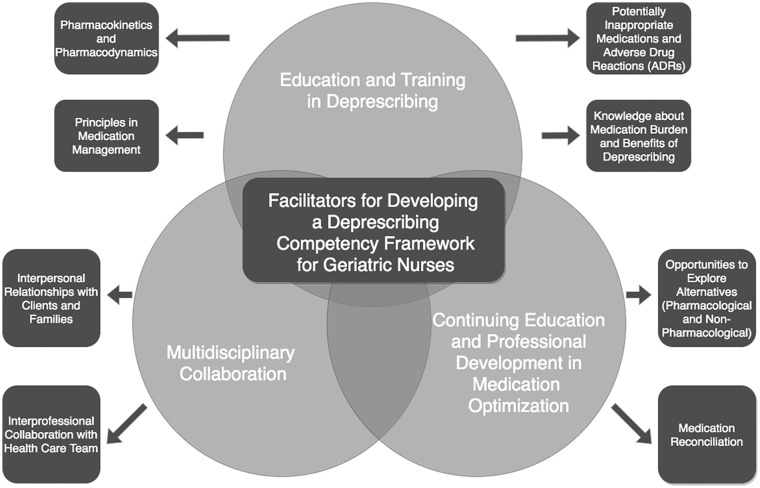

Articles were first screened based on titles and abstracts, and the potentially relevant articles were screened in full. During the Exploration Phase, all search results were reviewed independently by two reviewers, and records were classified as “potentially relevant” or “exclude.” The full text of “potentially relevant” articles are retrieved and the two reviewers independently reviewed the texts to make a final decision about their inclusion in the literature review. After applying the inclusion/exclusion criteria, a total of 24 relevant documents were included in the final literature review (Refer to Online Supplementary Table 1 for a summary of all included literature). During the Interpretation Phase, thematic analysis was conducted to examine the facilitators and barriers faced by nurses with regard to the process of deprescribing for older adult patients, and the development of deprescribing competency in nursing education (Refer to Figure 1 for the thematic diagram). Thematic analysis was carried out by adopting the approaches of Braun and Clarke Thematic Analysis (2006) to identify, analyze, and report patterns in the form of themes generated from the results of literature review. This process included familiarizing with the literature; generating initial codes; searching for themes and reviewing themes, as well as defining and naming themes. Finally, the Communication Phase included the presentation of themes that emerged from the data and the development of the study report for the literature review.

Figure 1.

Facilitators for Developing a Deprescribing Competency Framework for Geriatric Nurses.

Results

Despite the lack of existing evidence related to nursing involvement in deprescribing, thematic analysis of the literature revealed three main domains of deprescribing competencies for geriatric nurses: (a) Education and training in deprescribing (Ailabouni et al., 2017; Hermanowski et al., 2016; Hugtenburg et al., 2013; ISMP, 2018; Jassar, 2016; Lim et al., 2010; Liu, 2014; Maher et al., 2013; McGrath et al., 2017; Midão et al., 2018; Mortazavi et al., 2016; Page et al., 2016; Reeve et al., 2014; Reeve & Wiese, 2013; Salazar et al., 2007; Shah & Hajjar, 2012); (b) Continuing education and professional development in medication optimization (Ailabouni et al., 2017; Frank & Weir, 2014; Hermanowski et al., 2016; Jassar, 2016; Liu & Chi, 2013; Lueras & Lueras, 2017; Maher et al., 2013; McGrath et al., 2017; Page et al., 2016; Reeve et al., 2014; Salazar et al., 2007; Thompson & Farrell, 2013; Wang et al., 2015); (c) Multidisciplinary collaboration in medication management (Ailabouni et al., 2017; Frank & Weir, 2014; Gillis et al., 2016; Harriman et al., 2014; Hugtenburg et al., 2013; ISMP, 2018; Liu & Chi, 2013; Liu, 2014; Lueras & Lueras, 2017; Maher et al., 2013; McGrath et al., 2017; Reeve et al., 2014; Salazar et al., 2007; Turner et al., 2016). Each domain comprises the specific fundamental knowledge, skills, attributes, and values that were found to be integral components of nursing deprescribing. The thematic diagram (Figure 1) outlines the domains and sub-domains that make up the facilitators for developing a deprescribing competency framework for geriatric nurses. This thematic diagram demonstrates the overlapping concepts between the three overarching domains, as well as the inter-connectedness of the major and sub-themes.

Education and Training in Deprescribing

Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics

Findings from the literature review underscored the need for geriatric nurses to acquire the foundational education and training in order to facilitate safe deprescribing practices. A study indicated that nurse’s limited knowledge in both pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics can be a major barrier to their involvement in deprescribing (Lim et al., 2010). Knowledge in pharmacology is especially crucial when it comes to the management of polypharmacy among the older adult populations. Due to the natural process of aging, the phases of pharmacokinetics are impacted and the processes are often less efficient and decline with age (Davies & O’Mahony, 2015). The process of metabolizing and excreting the drug compounds may take longer for an older adult, thus allowing them to remain in their bodies for a longer period of time (Lim et al., 2010). At the same time, higher doses of medications have a greater likelihood of causing damaging ADRs, such as dizziness and poor coordination (Davies & O’Mahony, 2015). Therefore, drug doses should be adjusted to the age of the individual, as well as their renal clearance. Effective medication management involves nurses having knowledge about pharmacodynamics, ADRs, and the risks of drug interactions (Lim et al., 2010). Nurse educators must ensure that nurses at the undergraduate level to become fully knowledgeable about these aspects of pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics considerations among at-risk older adult populations in order to facilitate safe deprescribing of medications.

Principles of Medication Management

Education about the principles of medication management, especially the management of polypharmacy among the older adult population is considered to be an important facilitator to the development of nursing deprescribing competency. With many older adults taking multiple medications, it is possible that one medication alters the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of another (Lim et al., 2010), thus leading to an overall increase in drug dosage, and the likelihood of ADRs. As a result, it is essential to focus on the delivery of nursing education about the principles of medication management, specifically developing the knowledge and skills that address the needs of high-risk populations, such as older adults (Salazar et al., 2007). The understanding of medication management includes acquiring knowledge about both prescription and non-prescription medications which continue to evolve and grow over time with increased utilization. The market for pharmaceuticals constantly introduces different types of medications; whether it is a generic form, or something completely new (Salazar et al., 2007). Nursing education curriculum must be updated and revised on an ongoing basis while being cognizant of the ever-evolving changes, and how the new medications can affect the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of those existing medications, as well as how these medications can change nursing practice and process of medication management, with emphasis on the needs of deprescribing for older adults.

Potentially Inappropriate Medications and Adverse Drug Reactions (ADRs)

Nurses and other health care professionals need to be educated about ADRs and the dangers they pose to the aging population (Lim et al., 2010). ADRs often exist before the commencement of drug deprescribing. In fact, ADRs should be viewed as clear indicators that something needs to be changed, especially if they overpower the intended effects of the medication. However, ADRs can also occur as doses fluctuate. This can be especially apparent in targeted or narcotic medications, such as benzodiazepines or opioids. Nurses must be able to distinguish ADRs from phenomena such as withdrawal effects (Brett & Murnion, 2015). For example, withdrawal symptoms such as palpitations, muscle spasms, and delirium are common, and extremely unpleasant for older adults (Brett & Murnion, 2015). To facilitate effective deprescribing, nurses need to be well-educated at the undergraduate level with the ability to distinguish between ADRs and withdrawal effects to allow for a clearer understanding of the appropriate actions to support medication optimization for older adults in practice (Page et al., 2016).

Knowledge about Medication Burden and Benefits of Deprescribing

In order to competently assess the need for deprescribing, nurses must be properly educated in the nursing programs about the risks of polypharmacy and the benefits of deprescribing. Specifically, knowledge about the benefits of deprescribing should be focused at the individual level, but should also emphasize the impact at the economic level, including the financial implications of medication burden. This knowledge will help solicit the buy-in from older adults to consider the need for deprescribing harmful, inappropriate, or unnecessary medications (McGrath et al., 2017). The literature indicated a variety of facilitating factors that support nurses to promote medication management, including a resolution to ADRs, improved medication knowledge of the patient/caregiver, reduction in medications being taken daily, and a reduction in financial costs (Reeve & Wiese, 2013). For instance, an Australian study found that over 30% of participants stated that knowledge about the reduction of medication burden would encourage them to taper off their current medication regimen (Reeve et al., 2014). Knowledge about the benefits of deprescribing and the impact of medication burden is considered to be an important deprescribing competency for geriatric nurses.

Continuing Education and Professional Development in Medication Optimization

Opportunities to Explore Alternatives (Pharmacological and Non-Pharmacological)

Providing geriatric nurses with continuing education and professional development opportunities is an important facilitator to support the development of deprescribing competency. The literature suggested assessing nursing knowledge using yearly competency checklists, which address best practices, procedures, guidelines, and policies related to deprescribing (Jassar, 2016). Additionally, bi-annual seminars, interactive annual conferences, and webinars should be available to nurses to ensure they are aware of any policy or process changes to medication management (Jassar, 2016). The literature also recommended that nurses should have professional development pertaining to alternative approaches and non-pharmacological measures when dealing with medical problems such as poor sleep hygiene, pain management, symptoms of depression and anxiety, and other mental health concerns (Gillis et al., 2016). Rather than using pharmacological treatment for disease management, nurses should receive continuing education to explore evidence-based treatment alternatives to deal with symptom management with the aim of mitigating the safety risks of older adults (Gillis et al., 2016).

Medication Reconciliation

Out of the 24 reviewed literature, 11 of these articles underscored the need of having regular medication reconciliation with a health care professional, the patient, and patient’s caregiver to facilitate deprescribing, particularly in high-risk settings such as long-term care (LTC) due to the high prevalence of polypharmacy. A research study conducted in LTC settings indicated that nurses in LTC should have ongoing training in performing medication reconciliations on admission, after a transfer back from acute care and when resident status changes (Jassar, 2016). During these medication reviews, nurses are able to apply their pharmacological skills, address the impact of ADRs, and make recommendations for the potential need for deprescribing. Medication reconciliations allow nurses to explore patients’ misconceptions, or beliefs about the medication regimen that may influence their uptake of deprescribing (McGrath et al., 2017). Along with the process of medication reconciliation, it is recommended that nurses in LTC must develop the knowledge and skills to regularly conduct assessments that examine the physical function of adults and the degree of change associated with ADRs and deprescribing, such as the Minimum Data Set Activities of Daily Living (MDS-ADL) (Carpenter et al., 2006; Jassar, 2016). These assessment tools are facilitators to support geriatric nurses in deprescribing by allowing them to make informed decisions on how best to gradually taper off a specific medication based on older adult’s physiological status (Page et al., 2016).

Multidisciplinary Collaboration

Interpersonal Relationships with Clients and Families and Interprofessional Collaboration with Health Care Team

While deprescribing being performed primarily by physicians, the concept of multi-disciplinary collaboration with other health care professionals, including pharmacists, nurses (i.e., Nurse Practitioner, Registered Nurses, and Registered Practical Nurses) is suggested to show great promise in improving deprescribing outcomes (Liu, 2014). Two-thirds of all reviewed literature indicated that a critical facilitator for deprescribing is to build strong interpersonal and interprofessional collaboration with older adults, their caregivers, and all other involved health care professionals. However, a major area of concern identified by nurses is their ability to initiate deprescribing conversations with physicians (Turner et al., 2016). Other barriers identified by nurses include difficulties in soliciting patient’s buy-in about the need for deprescribing; the challenges associated with life expectancy and quality of life discussions with patients (Frank & Weir, 2014); the possibility of damaging relationships if the medication was prescribed by a third-party; and patient’s limited knowledge about medication management (Harriman et al., 2014). Although these barriers may exist, they can be overcome with strong, trustworthy multidisciplinary involvement to promote medication optimization. Providing education and training about interprofessional communication and collaboration within the nursing curriculum will allow geriatric nurses to develop effective communication skills and meaningful partnership to facilitate deprescribing conversations, as well as shared decision-making within the circle of care network involving older adults, caregivers, and health care professionals (Sun, Tahsin, Barakat-Haddad, et al., 2019).

Discussion

As polypharmacy among older adult populations continues to rise, the need for deprescribing has never been greater. Based on the findings of literature review, nursing education plays a critical role in supporting prospective nurses regarding the development of their competency in deprescribing, which will lead to better clinical outcomes for older adults (Sun, Tahsin, Lam, et al., 2019). At the individual level, deprescribing will decrease the number of inappropriate medications an older adult takes, which in turn, will result in the reduction of ADRs, the associated adverse events, as well as achieving greater overall health and well-being (Evans et al., 2011; Liu, 2014). Deprescribing education will prepare a nursing workforce with the relevant knowledge and skills to competently manage the impending polypharmacy crisis seen in the older population. Additionally, deprescribing competency will result in an increase in nurse’s self-efficacy associated with completing regular clinical reviews, as well as a reduction of time spent on daily medication rounds (Ailabouni et al., 2017).

Based on our findings, the successful development of a nursing deprescribing competency framework in geriatric care should include effective education and training, continuing education and professional development, and multidisciplinary collaboration. These findings are consistent with other literature (Wright et al., 2019) which highlighted the critical importance of advancing the nurse’s role in deprescribing. Wright et al. discuss that whether nurses are involved with prescribing medications or not, they are often involved in medication administration, so there should be an effort made to both reactively and proactively deprescribe medications to increase patient safety and promote positive patient outcomes. The role of the nurse in the deprescribing process includes active participation in a patient’s medication management which means a nurse should be able to not only effectively administer and optimize medications, but also recognize medication effects, drug sensitivities, incompatibilities, contraindications, prescribing errors, and polypharmacy impacts. The nurse’s role in the deprescribing could also consist of undertaking medication reviews and encouraging discussions with patients about their medications. In the future, the nurse’s role in deprescribing could hold even greater importance during “prescribing programs” when nurses are able to prescribe medications independently. Prescribing programs for nurses exist in the United Kingdom (Wright et al., 2019), and in Canada, there are similar changes underway to try to implement Registered Nurse prescribing in Ontario, Canada (College of Nurses of Ontario, 2020).

There is a lack of existing literature that involves nurses in the deprescribing process. This topic of interest is relatively new and under-study; however, the findings from this literature review were able to highlight the key facilitating factors to the successful development of nursing deprescribing competencies. This literature review has limitations that need to be acknowledged. Instead of conducting a literature review, the use of systematic review may provide a more thorough, and comprehensive approach to the search of the literature to minimize the potential bias in the study findings. This literature review can also be further strengthened by assessing and appraising the quality of the evidence. Despite its limitations, this literature review achieved its aim to identify gaps in research about the existing facilitators and potential barriers faced by nurses related to the process of deprescribing for older adults. As for the next phase of this project initiative, our future research agenda is to analyze the identified key domains and elements of nursing deprescribing competencies to support the development of a framework in deprescribing for older adults, which could be incorporated into the nursing education curriculum with the goal of promoting safety in medication management across the care continuum.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-wjn-10.1177_01939459211023805 for The Development of a Deprescribing Competency Framework in Geriatric Nursing Education by Winnie Sun, Magda Grabkowski, Ping Zou and Bahar Ashtarieh in Western Journal of Nursing Research

Footnotes

Data Sharing Statement: Additional unpublished data may be available for review upon request made to the primary author.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research received funding from Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council grant number [#211005].

ORCID iDs: Winnie Sun  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7616-5344

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7616-5344

Bahar Ashtarieh  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7412-0078

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7412-0078

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Ailabouni N., Tordoff J., Mangin D., Nishtala P. S. (2017). Do residents need all their medications? A cross-sectional survey of RNs’ views on deprescribing and the role of clinical pharmacists. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 43(10), 13–20. 10.3928/00989134-20170914-05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Brett J., Murnion B. (2015). Management of benzodiazepine misuse and dependence. Australian Prescriber, 38(5), 152–155. 10.18773/austprescr.2015.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter G. I., Hastie C. L., Morris J. N., Fries B. E., Ankri J. (2006). Measuring change in activities of daily living in nursing home residents with moderate to severe cognitive impairment. BMC Geriatrics, 6(1), 7. 10.1186/1471-2318-6-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- College of Nurses of Ontario. (2020, January 24). Journey to RN prescribing. https://www.cno.org/en/trending-topics/journey-to-rn-prescribing/

- Dagli R. J., Sharma A. (2014). Polypharmacy: A global risk factor for elderly people. Journal of International Oral Health, 6(6), i–ii. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4295469/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies E. A., O’Mahony M. S. (2015). Adverse drug reactions in special populations - The elderly. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 80(4), 796–807. 10.1111/bcp.12596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. C., Gerlach A. T., Christy J. M., Jarvis A. M., Lindsey D. E., Whitmill M. L., Eiferman D., Murphy C. V., Cook C. H., Beery P. R., II, Steinberg S. M., Stawicki S. P. (2011). Pre-injury polypharmacy as a predictor of outcomes in trauma patients. International Journal of Critical Illness and Injury Science, 1(2), 104. 10.4103/2229-5151.84793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell B., Tsang C., Raman-Wilms L., Irving H., Conklin J., Pottie K. (2015). What are priorities for deprescribing for elderly patients? Capturing the voice of practitioners: A modified Delphi process. PLoS One, 10(4), e0122246. 10.1371/journal.pone.0122246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank C., Weir E. (2014). Deprescribing for older patients. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 186(18), 1369–1376. 10.1503/cmaj.131873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis K., Steckel S., Laureys S., Lips D. (2016, October 4). Polypharmacy in elderly nursing homes: How nurses can contribute to deprescribing medications [Abstract/presentation/poster]. Wiley. https://limo.libis.be/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=LIRIAS1698990&context=L&vid=Lirias&search_scope=Lirias&tab=default_tab&lang=en_US&fromSitemap=1

- Harriman K., Howard L., McCracken R. K. (2014). Deprescribing medication for frail elderly patients in nursing homes: A survey of Vancouver family physicians. British Columbia Medical Journal, 56(9), 436–441. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267694765_Deprescribing_medication_for_frail_elderly_patients_in_nursing_homes_A_survey_of_Vancouver_family_physicians [Google Scholar]

- Hermanowski J., Levy N., Mills P., Penfold N. (2016). Deprescribing: Implications for the anaesthetist. Anaesthesia, 72(5), 565–569. 10.1111/anae.13783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugtenburg J. G., Vervloet M., van Dijk L., Timmers L., Elders P. J. (2013). Definitions, variants, and causes of nonadherence with medication: A challenge for tailored interventions. Patient Preference and Adherence, 7, 675–682. 10.2147/ppa.s29549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada. (2018). Deprescribing: Managing medications to reduce polypharmacy (Vol.18) [Safety bulletin]. https://www.ismp-canada.org/download/safetyBulletins/2018/ISMPCSB2018-03-Deprescribing.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Jassar S. (2016). The role of the nurse practitioner in promoting a reduction in the cause and outcomes of problematic polypharmacy among nursing home residents in British Columbia (10.24124/2016/1236) [Master’s thesis, University of Victoria]. Arca BC. https://arcabc.ca/islandora/object/unbc%253A17315 [Google Scholar]

- Lim L. M., Chiu L. H., Dohrmann J., Tan K. L. (2010). Registered nurses’ medication management of the elderly in aged care facilities. International Nursing Review, 57(1), 98–106. 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2009.00760.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B. C., Chi I. (2013). The moderating effect of medication review on polypharmacy and loneliness in older Chinese adults in primary care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61(2), 290–292. 10.1111/jgs.12102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L. M. (2014). Deprescribing: An approach to reducing polypharmacy in nursing home residents. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 10(2), 136–139. 10.1016/j.nurpra.2013.09.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lueras P., Lueras P. (2017). Deprescribing in the nursing home: Phase 1 - PRN medications. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 18(3), B13. 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.12.034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maher R. L., Hanlon J., Hajjar E. R. (2013). Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety, 13(1), 57–65. 10.1517/14740338.2013.827660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath K., Hajjar E. R., Kumar C., Hwang C., Salzman B. (2017). Deprescribing: A simple method for reducing polypharmacy. The Journal of Family Practice, 66(7), 436–445. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28700758/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midão L., Giardini A., Menditto E., Kardas P., Costa E. (2018). Polypharmacy prevalence among older adults based on the survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 78, 213–220. 10.1016/j.archger.2018.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi S. S., Shati M., Keshtkar A., Malakouti S. K., Bazargan M., Assari S. (2016). Defining polypharmacy in the elderly: A systematic review protocol. BMJ Open, 6(3), e010989. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naughton C., Hayes N. (2016). Deprescribing in older adults: A new concept for nurses in administering medicines and as prescribers of medicine. European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy, 24(1), 47–50. 10.1136/ejhpharm-2016-000908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onwuegbuzie A., Frels R. (2016). Seven steps to a comprehensive literature review: A multi-modal and cultural approach (1st ed.). SAGE Publications. https://study.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/Onwuegbuzie%20%26%20Frels.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Page A. T., Potter K., Clifford R., Etherton-Beer C. (2016). Deprescribing in older people. Maturitas, 91, 115–134. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeve E., Wiese M. D. (2013). Benefits of deprescribing on patients’ adherence to medications. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 36(1), 26–29. 10.1007/s11096-013-9871-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeve E., Shakib S., Hendrix I., Roberts M. S., Wiese M. D. (2014). Review of deprescribing processes and development of an evidence-based, patient-centred deprescribing process. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 78(4), 738–747. 10.1111/bcp.12386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar J. A., Poon I., Nair M. (2007). Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly: Expect the unexpected, think the unthinkable. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety, 6(6), 695–704. 10.1517/14740338.6.6.695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah B. M., Hajjar E. R. (2012). Polypharmacy, adverse drug reactions, and geriatric syndromes. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 28(2), 173–186. 10.1016/j.cger.2012.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W., Tahsin F., Barakat-Haddad C., Turner J., Haughian C., Abbass-Dick J. (2019). Exploration of home care nurse’s experiences in deprescribing of medications: A qualitative descriptive study. BMJ Open, 9(5), e025606. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W., Tahsin F., Lam A., Pizzacalla A. (2019). Raising awareness about the critical importance of the nursing role in deprescribing medication for older adults. Journal of the Gerontological Nursing Association, 40(4), 17–20. https://www.cgna.net [Google Scholar]

- Thompson W., Farrell B. (2013). Deprescribing: What is it and what does the evidence tell us? The Canadian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy, 66(3), 201–202. 10.4212/cjhp.v66i3.1261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner J. P., Edwards S., Stanners M., Shakib S., Bell J. S. (2016). What factors are important for deprescribing in Australian long-term care facilities? Perspectives of residents and health professionals. BMJ Open, 6(3), e009781. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., Chen L., Fan L., Gao D., Liang Z., He J., Gong W., Gao L. (2015). Incidence and effects of polypharmacy on clinical outcome among patients aged 80+: A five-year follow-up study. PLoS One, 10(11), e0142123. 10.1371/journal.pone.0142123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright D. J., Scott S., Buck J., Bhattacharya D. (2019). Role of nurses in supporting proactive deprescribing. Nursing Standard, 34(3), 44–50. 10.7748/ns.2019.e11249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-wjn-10.1177_01939459211023805 for The Development of a Deprescribing Competency Framework in Geriatric Nursing Education by Winnie Sun, Magda Grabkowski, Ping Zou and Bahar Ashtarieh in Western Journal of Nursing Research