Abstract

Background

Inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] affects all aspects of life, yet little is known about the impact of the condition on intimacy and sexuality and if such concerns should be discussed with health care professionals. This hermeneutical phenomenological study aimed to explore the experiences of people living with inflammatory bowel disease and discussing their sexuality concerns with health care professionals.

Methods

Participants [n = 43] aged 17–64 years were recruited. Data were collected via in depth interviews and anonymous narrative accounts [Google Forms]. Thematic analysis was used to analyse the data.

Results

An overarching theme ‘These discussions aren’t happening’ with four main themes were generated. The main themes were: ‘I can’t image talking about sex’; ‘I am a person, not my IBD’; ‘We need to talk about sex’; and ‘Those who talked about sex, talked badly’. Participants described the lack of conversations with their health care professionals on sexual well-being issues, in spite of the importance they gave to the topic, and identified barriers to having such conversations. They made suggestions for future clinical practice that would better meet their needs. The few who had discussed sexual well-being issues with health care professionals reported negative experiences.

Conclusions

Patients’ needs and preferences, about addressing during clinical appointments concerns related to their sexual well-being, should be addressed routinely and competently by health care professionals. Understanding the implications of inflammatory bowel disease for intimate aspects of the lives of those living with the condition could improve the quality of the care provided.

Keywords: IBD, intimacy, sexuality, well-being, health care professionals, interviews

1. Introduction

Intimate relationships in people living with inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] are challenged by fatigue, bowel symptoms, perianal disease, and having a stoma,1 with 15–30% reporting a negative impact of IBD on their sex life.2,3 Since IBD has a negative effect on intimacy and sexuality, it might be expected that health care professionals [HCPs] would routinely assess and discuss sexual well-being. Current literature showed no evidence that HCPs routinely discuss sexual well-being with those living with IBD, although this has been previously suggested to IBD multidisciplinary teams.4

Sexual well-being refers to ‘the perceived quality of an individual sexuality, sex life and sexual relationships’.5 It does not imply the absence of disease, and should not be confused with sexual health, which refers to preventing or treating sexually transmitted infections. The concept is related to a more holistic approach to sexuality and intimacy. The definition of sexual well-being remains controversial due to the complexity of the concept and the difficulty of measuring it. However, the accepted notion refers to not just what a person wants to do in terms of intimacy and sexuality, but also what is their physical capacity to do what they desire.6

The aim of this study was to explore the experiences of people with IBD discussing sexual well-being issues, or intimacy and sexuality-related concerns, with health care professionals, and patients’ perspectives on how such conversations should take place.

2. Materials and Methods

Hermeneutic phenomenology designs are concerned with interpretation of written text, and van Manen’s7 framework is an established stand-alone methodology used in social and health sciences for interpreting lived experiences.

Participants approached the study team in response to an advertisement on the research webpage of a national IBD charity. Those with a self-reported IBD diagnosis, age 16 years and over, of any sexual orientation, and English-speaking were included. Data were collected either as a single semi-structured interview via telephone or face to face or from narrative accounts submitted anonymously via Google Forms [GF], as participants chose, following written or verbal consent. GF were accessed via a link inserted into the Participant Information Sheet, and contained a few demographic questions followed by a free-text box where they were prompted to describe their experiences. The same questions were used as an interview guide [see Box 1]. Due to the sensitive nature of the study, and in an attempt to encourage participation, GF was used for anonymous data collection.8 This aligned with the aim of letting the participants elaborate on issues that were important to them based on their experiences, rather than investigate researcher-directed concepts. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Box 1. Interview guide.

What is your condition?

How long did you have the condition for?

Can you describe your experience of intimacy and sexuality from your perspective of living with IBD?

Can you tell me about any occasions when you have discussed your sexual well-being with health professionals?

Do you think such conversations should take place at the time of clinical visits?

How would you like such conversations to take place?

Van Manen’s framework for thematic analysis was used.9 NVivo 12 software was used for data organisation and storage. The final themes depicted aspects important to participants and were strictly derived from interview data in an inductive way. The results represent an interpretation of personal experiences of participants and were aimed at both interdisciplinary and patient understanding.

2.1. Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from University of Oxford Ethics Committee [R60900/RE001]. Privacy and anonymity were maintained throughout the study. All participants were allocated a pseudonym and consented to the publication of anonymised excerpts. Direct quotes are presented verbatim, also giving the participant’s pseudonym, age, sex, diagnosis (ulcerative colitis [UC] or Crohn’s disease [CD]). A few participants from the UK were at the time of their interview aged 17, as the legal age for consent to research is 16. The participants from other countries were all over 18, therefore not contravening their own country’s legislation.

3. Results

A total of 43 participants (Table 1) consented to take part in the study between March 2019 and July 2020, 23 opted for interviews that lasted between 20 to 60 min, and 20 sent anonymous narrative accounts [see Box1]. Participants were mainly from UK. Over 75% of participants were in a long-term relationship or married. One participant identified as a gay man, one participant identified as trans man, and two [male and female] identified as bisexual. The full demographic details for those who responded anonymously via GF were not known, neither was their geographical location. Based on their narratives, all but one participant who responded via GF identified themselves as female, although the study was open to all genders and non-binary were not excluded. No direct information about their age was given via GF; however, most of them stated the length of their diagnosis and their approximate age when they were diagnosed, which made possible to establish an age range for all but two the study participants.

Table 1.

Study population.

| Numbers | |

|---|---|

| Age range (years) | 17–64 |

| Crohn’s disease | 31 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 12 |

| Male | 11 |

| Female | 32 |

| Married/partnered | 33 |

| Single | 9 |

| UK participants | 40 |

| Other [Ireland, USA, South Africa] | 3 |

Participants reported various degrees of IBD disease activity, from mild to severe forms. Eleven had previous surgery resulting in permanent stoma formation or an ileo-anal pouch, over a third had surgery for perianal disease, and 3 women had diagnosed vulval Crohn’s disease.

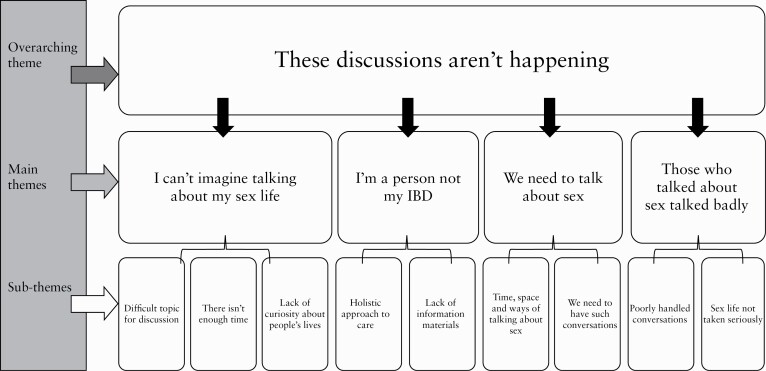

Figure 1 summarises the themes and sub-themes. The dominant narrative from interviews and Google Forms was that in general, conversations about intimacy and sexuality were not taking place. ‘These discussions aren’t happening’ was the overarching theme generated by interpretation of the common thread through the themes, integrating some of the reasons why these conversations were not happening or were avoided, in spite of the topic being important to participants:

Figure 1.

Themes and subthemes.

Before you have surgery you should talk about the impact of surgery. That’s an opportunity to talk about sexual relationships and intimacy post-surgery. But these discussions aren’t happening. [Martha 38 F, CD]

3.1. Theme 1: ‘I can’t imagine talking about my sex life’

This theme includes patient-reported barriers in discussing their concerns with HCPs and the feeling that the sensitive nature of such discussions, lack of time and privacy, and lack of initiative from HCPs contributed to these conversations not taking place.

I can’t imagine talking about my sex life. [Laura 30s F, CD]

3.1.1. Difficult topic for discussion

The sensitive nature of the topic was the greatest barrier from participants’ perspectives; they felt uncomfortable about initiating such conversations with HCPs.

It’s [sex] never been mentioned to me by any consultant or other person. I guess they feel a bit uncomfortable bringing that up. [Emma 36 F, CD]

I would find it very hard to discuss it face to face with my care team. [Emily 42 F, CD]

Some suggested that clinical appointments were not providing an adequate forum for more personal issues, although the need to address these was present.

Of course women don’t bring this stuff up to doctors easily. We are doubly shamed—as women about our sexuality in general, and because we have this disgusting disease that you’re not supposed to talk about. Add being queer to that and it’s pretty much hopeless. [Carina 40 F, CD]

Participants from sexual minorities found it particularly difficult to open up and discuss with HCPs, although most of them had previously disclosed their sexual orientation to the clinical team. Some assumed that HCPs’ awareness of them identifying as a sexual minority added a barrier to discussing sexual well-being.

Maybe it is just because they’re trying so hard to be careful with me as a trans man … nobody asked. It’s like your bowel is in a different body from your sexual organs. [Richard 62 M, CD]

I feel like people in my HCP team either haven’t got the knowledge to discuss with me, the ways that it [IBD] affects it [sex], or haven’t been willing to discuss. And I sensed a certain reluctance among them cos I’m bisexual. [Mark 26 M, CD]

For younger participants, attending clinics with a parent was seen as adding to the difficulties of HCPs in bringing the topic up for discussion

I feel like it may also be because my mum comes to all my appointments with me just because, I mean me and my mum are close, so it’s not a problem for me to talk about intimacy or anything in front of her, but I feel like, perhaps that made the consultant or whoever I was talking to, more reluctant to bring it up because obviously, some people are more awkward in front of their mums talking about stuff like that. [Melania 17 F, UC]

3.1.2. There isn’t enough time

Perceived time constraints were often recognised as barriers to discussing aspects of participants’ sexual well-being. Current pressures in the UK National Health Service to see large numbers of patients in clinics, only allowing appointments of 10 to 20 min, was perceived as a deterrent to discussing anything outside treatment efficacy or symptoms with the HCPs.

There is no time or space to discuss anything else that may seem trivial. [Denise 36 F, CD]

It was also suggested that discussion of sensitive topics required a rapport between patient and HCPs, which involved time as well.

I know they actually there are huge differences in how comfortable people are asking these questions, but sometimes even if you’re comfortable it’s clear that the issues the person is bringing, they need more time. [Ana 40 F, CD]

3.1.3. Lack of curiosity about people’s lives

HCPs’ reticence to initiate discussions on sexual well-being topics was negatively perceived by some:

The lack of curiosity about people and about people’s lives I think goes throughout the multidisciplinary teams. [Martha 38 F, CD]

Furthermore, participants indicated that they were troubled by the lack of initiative from HCPs. This assumption of lack of curiosity was made mainly by participants who had negative experiences of asking HCPs questions related to intimacy and sexuality. Lack of HCP experience and knowledge in discussing these issues, as well as lack of time to do this, could have been wrongly interpreted as lack of curiosity or interest. The absence of questions, other than strictly medical ones, from HCPs involved in the care of the participants was seen as a barrier to any attempt to bring up other topics for discussion during clinical appointments, some concluding that HCPs were uninterested in their patients’ lives.

I sometimes feel that any, even sort of medical, strictly medical questions, are sort of not really encouraged. So … it would never occur to me to talk about more intimate things. [Daniel 31 M, UC]

3.2. Theme 2: ‘I’m a person, not my IBD’

This theme proposed ways of moving forward as participants felt that they were not approached holistically by their HCPs, starting from the feeling that participants did not want to be identified as just their IBD, and this suggested their expectations for future practice.

I just I don’t like to be identified by my condition because I don’t feel like it’s part of me, I just think that it [IBD] is what I have. [Nora 18 F, CD]

3.2.1. A holistic approach to care

The expectation of holistic care was found to be unanimously sought by participants. Whether they described experiences where this was not the case, or they made suggestions for how they wanted to be seen, the concept had an important place in the participants’ narratives.

You don’t necessarily get the sense that they’re thinking of your complete life in all its sort of aspects. It’s: ‘Right! I’m seeing you as a colon, or lack of one, and that is what I’m treating and I’m not really interested in something else. [Daniel 31 M, UC]

People living with IBD expressed a wish to have holistic care that would include routinely addressing sexual well-being concerns.

You treat my sexual health problem, you’re treating my Crohn’s! You treat my eyes; you’re treating my Crohn’s! You treat my anxiety; you’re treating my Crohn’s! You treat my self-esteem, you’re treating my Crohn’s and we’re gonna get to treat me whole. We’re both on the same journey! But they’re only looking at one aspect of it, and they miss it completely. [Martha 38 F, CD]

3.2.2. Lack of information materials

Alongside the main suggestion to treat holistically, participants consistently described their experiences of the absence of sources of information on the topic in clinical settings. Our participants’ information needs varied, depending on age, gender, and severity of symptoms, and they suggested various sources for information. If the possibility to have a discussion with their HCPs was excluded as a result of the participant’s choice, or dictated by clinical circumstances [lack of time or privacy], they still expected HCPs to signpost them to the appropriate support available.

If there was a leaflet particularly about sex that would be helpful, especially for people who really don’t want to talk about it to anyone, and then they can at least pick that up and be left alone in that way… I think charities should be a lot more open about sex as well. I think Crohn’s and Colitis UK have a leaflet about sex, but from what I remember it’s pretty vague it just says you should talk to your partner about sex, you can still have a loving relationship, and I just found that pretty annoying! [Be]cause that does reinforce the feeling that you’re on your own or making up something about nothing I think. [Emma 36 F, CD]

The insufficient or complete lack of information received from HCPs about sexuality, sexual function, or symptoms that may interfere with sex life, was perceived by participants as a poorly handled topic, as their expectations were not met. Information was sought by a number of participants, especially in the early stages after their diagnosis or at the time of surgery. Even those who had been diagnosed many years ago, argued that such information should be offered to all patients newly diagnosed with IBD, or when their circumstances changed, for example undergoing surgical procedures or changing medication.

Those who had been given information on sexual well-being, or those who sought sources of information felt that information found was often insufficient, and they questioned the reliability of potential sources. Gathering information from other patients’ experiences was frequently mentioned in interviews as a way of accessing information.

There’s a lot of forums because people on there will talk about it [sex] and you know they’re quite open about it as well. So it’s, and there’s all sorts of people like different sexualities in there as well, it’s kind of interesting to speak to them. And there’s a wide range, some people have got their colostomy bags. You know they’ll find it difficult just to be like intimate with somebody. I suppose you’ll get a lot of support from them [the forums]. [James 42 M, CD]

3.3. Theme 3: ‘We need to talk about sex’

The message that participants wanted to give to HCPs was that there was a need for breaking the taboos surrounding these discussions, and it was a call for discussions about intimacy and sexuality to take place in the clinical environment, as IBD had a negative impact on their sexual well-being.

Sex is a normal part of life. And if there’s something in your life that is stopping you from doing something that is normal, you go along to a doctor or specialist to try get help with it. And this is absolutely no different. [Sandra 60 F, CD]

Although, as a previous sub-theme highlighted, these are difficult conversations to have with HCPs, a few had no issues in opening such conversations when needed.

I’ve talked about it a lot; I’m not worried about talking about it. I may have been when I was younger, but as I’ve got older and I’ve seen my past relationship break down, and I want to go on and have children again. [Martha 38 F, CD]

3.3.1. ‘We need to have such conversations’

Many participants felt that such conversations should take place, sex is an important part of their lives.

For some people it [sex] might not be such a big issue, but for others it’s going to be… For me, it is an important part of my life. [Ana 40 F, CD]

People claimed that sexual well-being in IBD demands similar attention as sexual well-being in cancer, therefore they argued the importance of talking about it.

Crohn’s affects people’s bodies, and it’s every bit of your body and therefore it’s going to affect your sexuality as well. Your choice of partner, whether you can go out dating or not, how you can go out dating, all of it. And it needs to be brought up. Like I said, they do it with cancer, they talk to you about how you can live your life to the fullest with cancer, but nobody does it with us. And IBD goes on for a hell of a lot longer than cancer. [Orla 41 F, CD]

Moreover, the need to bring up the topic in the clinical environment was advocated as participants felt that HCPs do not fully understand the negative impact IBD has on their sex life.

Doctors need to understand that sex is one of the basic everyday things that gets wrecked by IBD, just like eating or socialising or school or work or exercise. They need to imagine what it would be like for them if they were worried about shitting themselves during intimate moments. [Carina 40 F, CD]

Although the general consensus was that there is a genuine need for such conversations, a deviant finding came from one participant who felt the opposite about such conversations.

Having such a conversation will not help, just expose me more to another person. [Kate 47 F, UC]

It was largely accepted that talking about intimacy and sexuality issues may not necessarily offer a solution, yet participants looked for an acknowledgement from the HCPs of what they experience, and for validation of their feelings by being believed. This was particularly important for those with perianal disease, who disclosed issues related to their sexual well-being but felt they were not listened to, or that their concerns were not fully understood by HCPs.

Awareness should be made about how hard life is with fistulas and how complicated it is living with the pain of setons… If you go in as an emergency surgery, you could end up with a cable tie in your bottom, that makes you cry for the rest of your life until it’s removed. [Sara 46 F, CD]

Moreover, most stated that there was a great need to discuss these issues with someone, and in absence of such opportunity, the present study had offered them a platform to talk.

I saw your study and thought I’d be interested to take part, because it felt like the door that was opened up as a forum to talk about these things… I have not felt [door] has ever been opened conspicuously to me and I haven’t talked to anyone about this. The things I’m saying to you now I haven’t said to anyone before, so clearly I haven’t felt that that door was open. [Daniel 31 M, UC]

3.3.2. Time, space and ways of talking about sex

Finally, participants suggested as a way forward that HCPs should routinely address sexual well-being concerns with those for whom considered it was relevant, and for younger participants possibly alongside family planning.

I would like to have access to a specific clinic/appointment for family planning, sexual health for IBD patients. A place where I know these are the main aspects discussed and where I can ask questions, receive information and feel normal. [Julia 20’s F, CD]

The need to address sexual well-being in IBD was perceived by those living with the condition as an important step forward in providing a good quality of care. Although the need for time and space was acknowledged, the majority expected that HCPs should be more engaged in these conversations, have knowledge of the impact of IBD on their intimacy and sexuality, and to initiate this conversation at least once with each patient. In this way HCPs can identify those who are responding to this invitation for a dialogue and may open up about their sexual well-being concerns.

Health care professionals should be prepared to talk about it… Maybe fill in a small questionnaire before clinical appointment and know who wants to have this conversation. [Richard 62 M, CD]

3.4. Theme 4: Those who talked about sex, talked badly

The few experiences of previous conversations with HCPs about sex-related issues were elements of the last theme. Participants described poorly handled conversations and fear of sexual concerns being trivialised, therefore not considered important, by HCPs.

3.4.1. Poorly handled conversations

From those who had discussed sex with HCPs, some recounted having bad experiences of such conversations.

The only people that talked about it, and really badly I think, was the stoma nurse that I saw. [Ana 40 F, CD]

Negative experiences diminished the potential to raise such topics with their HCPs during subsequent appointments, either because of perceived lack of sensitivity from HCPs or because of disparities between patients’ and HCPs’ views on what is a fulfilling sexual life.

I was 21 and I had my first stoma and a 65-year-old nurse came out to the house. I was having problems with getting bags to stick on. I was sent home over weekend with no understanding of my bags and I said that we haven’t had sex for a long time because I’ve been in hospital for 19 weeks, and he is trying to be intimate. She told me to just give him oral sex, [this] was the nurse advice to me. That is the only piece of advice I’ve had over the 25/26 years and 40 operations, no one has ever discussed sex with me. [Sara 46 F, CD]

3.4.2. ‘My sex life is not taken seriously’

Another perception was that sex life concerns were not seen as important by HCPs. Particularly for those who had experienced delays in their diagnosis, talking about sexual well-being made them fear that the topic would again involve effort in convincing HCPs that their concerns were real:

I’ve talked about pain [during sex] on so many occasions with an IBD specialist, with GPs, with my surgical team, and I’ve never ever once had someone take it seriously. [Martha 38 F, CD]

The struggle to be believed when participants disclosed issues related to sexual well-being was mostly challenging for those with severe perianal disease and vulval Crohn’s; delays in being diagnosed or receiving treatment reinforced the feeling that their sexual well-being warranted less significance for HCPs.

I got to the point where I said: this is my labia going black and falling off, and I’m still not getting any answers. [Catriona 43 F, CD]

4. Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first qualitative study to investigate the experiences of those living with IBD and discussing their sexual well-being with HCPs, and highlighted the absence of such dialogue between patients and HCPs. Most importantly, details on perceived barriers to discussing sexual well-being were present in their narratives. The sensitive nature of the topic, limited time, topic not being considered important, and the perceived lack of interest from HCPs were the most frequently reported barriers to discussion. Additionally, our findings highlighted that those living with IBD felt that aspects of how one’s life is affected by IBD may not be known to HCPs. Experiences of not having a holistic approach to their care, one which would include addressing sexual well-being explicit and implicit, prompted suggestions for future practice from all participants.

There is no doubt that conversations about such as sexual well-being are often difficult. Furthermore, there are no measurement tools available in the context of IBD to assist the HCP; hence it is not clear how they should assess sexual well-being. In the absence of a tool or guidance in IBD, simply asking the patient for their perspective would seem to be a good initial approach. Patient perspectives on discussing intimacy, sexuality, or sexual well-being issues with HCPs remain under-researched generally, not just in IBD. The literature is predominantly based on HCPs’ views and not on patients’ views. Studies have covered views of oncology,10–12 cardiovascular disease,13 rheumatology,14 and dermatology patients,15 but no literature was found on views of those living with IBD.

Although it is hard to estimate the prevalence of sexual and relationship difficulties in IBD, one study showed that up to 90% of women surviving gynaecological cancer encountered such difficulties,16 and 64% of cancer survivors would want HCPs to discuss sexuality issues.17 Our study brings up for the first time the perspective of IBD patients, who have identified barriers to these conversations which could be classified as being personal, HCP, and environmental barriers.

It is accepted that a satisfying sexual relationship enhances quality of life [QoL],18 and sex is an important aspect of QoL.19,20 Sexuality issues are much more than biological concerns, they encompass intimacy and relationships, which warrants a holistic approach from the HCPs, although the participants in our study reported the absence of such an approach. Looking at the age range of IBD diagnosis, it is reasonable to argue that a large number of those who have IBD are either at a stage in their life when sexual identity emerges, or at the peak of their conceiving period, which sets sexuality issues as high priority for those living with IBD. In spite of this, our study showed that older participants, who were likely past fertility, still identified as wanting to be able to engage in sexual expression and activity and further challenged the common stereotype that older people are asexual.21

Personal barriers were directly linked to the participants themselves, as they did not feel comfortable to open the discussion. Participants reported feeling ashamed or embarrassed and having a fear of being negatively judged by HCPs. These fears were more acute in the case of participants who self-identified as belonging to a sexual minority, as it was too much to overcome the fear of being judged. It is, consequently, not surprising that they were reluctant to engage in such dialogues. Young adults from sexual minorities have reported infrequent discussions on sexuality-related issues with their clinicians, in a previous study in the general population.22 HCPs should be aware about information-seeking behaviour in patients, as it changes with age and it is also gender dependent, older men being more likely to engage in such conversations with their HCP.23

HCP barriers point to HCPs not initiating the discussion. Our participants’ perceptions are consistent with those of oncology, rheumatology, heart disease, and dermatology patients.11,12,14,15 Participants in cancer studies wanted to be asked about their sexuality issues and preferred to receive information on the topic from their HCP.17,24 One barrier was the perceived lack of interest from HCPs in discussing sexuality/sexual well-being with the participants. This was similar to the findings from a study among patients after a stroke, which suggested that HCP lack of motivation to discuss sexual well-being was one of the barriers to addressing sexual well-being.25 In the absence of professional advice, participants had explored various sources of information, and a review looking at information needs in the IBD population found existing online resources unreliable.26

Environmental barriers were lack of time to have a discussion and lack of space to ensure confidentiality. Participants feared that time constraints would not allow anything that was not symptom or treatment-related to be discussed during their clinical appointments. Previous cancer studies exploring patients’ and HCPs’ views also found that an appropriate space to maintain privacy had the potential to support sensitive discussions, as well as sufficient time being allocated to clinical appointments.11,12,27

Participants had unmet needs as a result of personal, HCP, and environmental barriers when they sought information, especially those who had undergone surgery or had perianal disease The third British National Survey of Sexual Attributes and Lifestyles has also identified similar unmet needs in the general population, suggesting that less than half of those who reported sexual difficulties have sought help.28 HCPs should acknowledge that patients’ needs stretch further than achieving IBD remission or reduction of symptoms. The sexual well-being of those living with IBD is woven deeply into their relationships, concerning their psycho-emotional balance, not just the absence of physical symptoms of IBD or a remission status.

4.1. Limitations

Since this was a phenomenological study, its aim was to produce an interpretation of participant experiences, which may not be generaliable. It is possible that the participants in this study were more likely to have sexual well-being issues than the wider IBD population: although participants who had mild disease volunteered to take part, they may have been a minority. Participants were recruited outside the clinical environment, and therefore they have self-reported as living with IBD, which is one of the limitations of the study. The study population was predominantly female, aged over 35 years, with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease, and in a long-term heterosexual relationship, therefore potentially not representing a diverse IBD population. Sexual minorities were well represented in our study, as the percentage of participants self-identified as belonging to a sexual minority in the study was higher compared with the percentage found in general population. The findings cannot be extended to those who have mild disease, are single, or are aged 16 to 35, as these groups were also under-represented in our study. No ethnicity data were collected, although the researchers acknowledge that this would have added to the richness of the results.

4.2. Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study providing evidence on what IBD patients want from their HCPs in terms of addressing this sensitive topic. Sexuality and sexual well-being were important to those living with IBD, as they aimed to continue normal living while having IBD. The study highlighted negative patient experiences in raising their sexuality concerns with their HCPs and in their perceptions of HCPs attitudes to their concerns and needs. Similarly, it gives an interpretation of the essence of their experiences on the topic. Although several of the findings are similar to those from cancer, cardiovascular disease, rheumatology, and dermatology studies, we have identified IBD-specific issues, mainly related to perianal disease and vulvar Crohn’s. Patients recognised the influence of several barriers to these conversations with HCPs, and suggested that the topic should be addressed as a component of the holistic care they desire.

4.3. Implications for practice

HCPs should be cognisant of the concerns and needs of those in their care, and actively seek ways of enabling such conversations to take place. It is important for HCPs to recognise that ignoring sexual well-being puts pressure on patients to raise this issue, potentially causing them to feel ashamed and negatively judged. Training needs for HCPs involved in the care of those living with IBD should be identified and addressed. Sexual well-being should form part of routine care for all patients with IBD, and HCPs should facilitate dialogue, particularly with those with perianal disease. As an alternative to verbal discussions, signposting to reliable sources of information was proposed to address specific age, gender, sexual orientation, and disease severity needs.

Further research on tool development to assess sexuality needs of patients should be explored, as well as on the need for setting services to address this specifically. Information materials should be designed with the help of the patients and made available in written form in clinics and online, to cover the unmet needs of those living with IBD. Raising awareness of sexual well-being issues within the wider patient and HCP population should also be considered.

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly, for the privacy of individuals who participated in the study. The data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Crohn’s and Colitis UK for their support to reach their members, by advertising our study on their research page. We are grateful to all participants for their courage to speak openly about their experiences, as some confessed they never shared these details with anyone. We also acknowledge Prof. Alison Simmons for her support.

Funding

No funding was sourced for this project.

Conflict of interest

All authors declared no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

SF: design of the study, data acquisition, and analysis. SF, CN, DJ, WCD: interpretation of data, drafting the article, and final approval of version submitted. Part of this work was presented as a poster abstract at the 15th Congress of ECCO in Vienna, February 2020.

References

- 1. Byron C, Cornally N, Burton A, Savage E. Challenges of living with and managing inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-synthesis of patients’ experiences. J Clin Nurs 2020;29:305–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rivière P, Zallot C, Desobry P, et al. Frequency of and factors associated with sexual dysfunction in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:1347–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bokemeyer B, Hardt J, Hüppe D, et al. Clinical status, psychosocial impairments, medical treatment and health care costs for patients with inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] in Germany: an online IBD registry. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:355–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sanders JN, Gawron LM, Friedman S. Sexual satisfaction and inflammatory bowel diseases: an interdisciplinary clinical challenge. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:58–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Laumann EO, Paik A, Glasser DB, et al. A cross-national study of subjective sexual well-being among older women and men: findings from the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. Arch Sex Behav 2006;35:145–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lorimer K, DeAmicis L, Dalrymple J, et al. A rapid review of sexual wellbeing definitions and measures: should we now include sexual wellbeing freedom? J Sex Res 2019;56:843–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van Manen M. Researching Lived Experience. Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy. 1st edn. Western Education, London, ON: Althouse Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fourie S. Using Google Forms in research on sensitive topics. Int J Qual Methods. 2020;19:66. [Google Scholar]

- 9. van Manen M. Researching Lived Experience. Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy. 2nd edn. New York NY: Routledge; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Traa MJ, De Vries J, Roukema JA, Rutten HJ, Den Oudsten BL. The sexual health care needs after colorectal cancer: the view of patients, partners, and health care professionals. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:763–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leonardi-Warren K, Neff I, Mancuso M, Wenger B, Galbraith M, Fink R. Sexual health: exploring patient needs and health care provider comfort and knowledge. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2016;20:E162–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Traumer L, Jacobsen MH, Laursen BS. Patients’ experiences of sexuality as a taboo subject in the Danish health care system: a qualitative interview study. Scand J Caring Sci 2019;33:57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Byrne M, Doherty S, Murphy AW, McGee HM, Jaarsma T. Communicating about sexual concerns within cardiac health services: do service providers and service users agree? Patient Educ Couns 2013;92:398–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Helland Y, Dagfinrud H, Haugen MI, Kjeken I, Zangi H. Patients’ perspectives on information and communication about sexual and relational issues in rheumatology health care. Musculoskeletal Care 2017;15:131–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Barisone M, Bagnasco A, Hayter M, et al. Dermatological diseases, sexuality and intimate relationships: A qualitative meta-synthesis. J Clin Nurs 2020;29:3136–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alappattu M, Harrington SE, Hill A, Roscow A, Jeffrey A. Oncology section EDGE task force on cancer: a systematic review of patient-reported measures for sexual dysfunction. Rehabil Oncol 2017;35:137–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Albers LF, van Belzen MA, van Batenburg C, et al. Discussing sexuality in cancer care: towards personalized information for cancer patients and survivors. Support Care Cancer 2020;28:4227–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McCann E, Donohue G, de Jager J, et al. Sexuality and intimacy among people with serious mental illness in hospital and community settings: a qualitative systematic review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 2018;16:324–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tierney DK. Sexuality: a quality-of-life issue for cancer survivors. Semin Oncol Nurs 2008;24:71–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davison TE, McCabe MP. Adolescent body image and psychosocial functioning. J Soc Psychol 2006;146:15–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gott M, Hinchliff S. How important is sex in later life? The views of older people. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:1617–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fuzzell L, Fedesco HN, Alexander SC, Fortenberry JD, Shields CG. “I just think that doctors need to ask more questions”: sexual minority and majority adolescents’ experiences talking about sexuality with health care providers. Patient Educ Couns 2016;99:1467–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Whitfield C, Jomeen J, Hayter M, Gardiner E. Sexual health information seeking: a survey of adolescent practices. J Clin Nurs 2013;22:3259–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Southard NZ, Keller J. The importance of assessing sexuality: a patient perspective. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2009;13:213–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mellor R, Bailey S, McManus R, Investigator B, Singh S. A taboo too far? Health care provider’s views on discussing sexual wellbeing with stroke patients. Int J Stroke 2012;7:4–5. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Khan S, Dasrath F, Farghaly S, et al. Unmet communication and information needs for patients with IBD: implications for mobile health technology. Br J Med Med Res 2016;12:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dyer K, das Nair R. Why don’t health care professionals talk about sex? A systematic review of recent qualitative studies conducted in the United Kingdom. J Sex Med 2013;10:2658–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hobbs LJ, Mitchell KR, Graham CA, et al. Help-seeking for sexual difficulties and the potential role of interactive digital interventions: findings from the Third British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles. J Sex Res 2019;56:937–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]