Abstract

Introduction

Diabetes is the most common of comorbidity in patients with SARS-COV-2 pneumonia. Coagulation abnormalities with D-dimer levels are increased in this disease.

Objectifs

We aimed to compare the levels of D-dimer in diabetic and non-diabetic patients with COVID 19. A link between D-dimer and mortality has also been established.

Materials

A retrospective study was carried out at the University Hospital Center of Oujda (Morocco) from November 01st to December 01st, 2020. Our study population was divided into two groups: a diabetic group and a second group without diabetes to compare clinical and biological characteristics between the two groups. In addition, the receiver operator characteristic curve was used to assess the optimal D-dimer cut-off point for predicting mortality in diabetics.

Results

201 confirmed-COVID-19-patients were included in the final analysis. The median age was 64 (IQR 56-73), and 56% were male. Our study found that D-dimer levels were statistically higher in diabetic patients compared to non-diabetic patients. (1745 vs 845 respectively, P = 0001). D-dimer level > 2885 ng/mL was a significant predictor of mortality in diabetic patients with a sensitivity of 71,4% and a specificity of 70,7%.

Conclusion

Our study found that diabetics with COVID-19 are likely to develop hypercoagulation with a poor prognosis.

Keywords: Diabetes, D-dimer, C-reactive protein, COVID-19, Coagulopathy, Inflammation

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). 1 The number of infected cases is increasing exponentially worldwide, and the World Health Organization declared it a pandemic on March 11th, 2020. More than 120 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 had been recorded worldwide, with more than 2,7 million deaths as of March 21st. 2

People with diabetes have a higher risk of getting various infections. So far, studies have shown that diabetes has been one of the serious comorbidities in patients with COVID-19, which may be due to other risk factors, such as age, hypertension and obesity, associated with diabetes. It may also due to the fact that there are intrinsic factors in people with diabetes that make them more vulnerable to the cytokine storm. And as a consequence, this condition may result from an imbalance between coagulation factors and fibrinolysis which may be responsible for higher risk of thrombotic events, which can lead to death. 3

D-dimer, a fibrin degradation product, is commonly used as a biomarker of thromboembolism for critical patients and as a prognostic marker. Therefore, as a biomarker to predict the seriousness of the disease, D-dimer has been studied because COVID-19 is a procoagulant state.

Since COVID-19 has established diabetes as a predictor of the seriousness of the disease, it remains to be seen why D-dimer values differ from those without diabetes and those with diabetes until they can conclude that this was one of the causes of the extreme COVID-19 disease that indicates increased vulnerability to diabetes to the thromboembolic disease. Therefore, this study aimed to study the levels of D-dimers in diabetic patients relative to those non-diabetics in patients with infection with COVID 19. Also, the determining an optimal cut-off to predict the risk of mortality in diabetics has been established.

Materials and Methods

This is a retrospective descriptive and analytical study carried out at the level of the COVID service of the Mohammed VI hospital in Oujda in Morocco from November 01st to December 01st, 2020, and all these cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed in the laboratory by Real-Time Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RTPCR). Exclusion criteria were age <18 years, patients were on anticoagulants or had a history of venous thromboembolism and pregnancy, and only patients who received a D-dimer assay were included in this study. The collection of anamnestic, clinical, paraclinical, therapeutic and evolutionary data for each patient was carried out from electronic medical records. Based on their medical records, cases were classified into diabetic and non-diabetic classes.

The data were entered and analyzed on to SPSS 20 software by first performing a descriptive analysis of the various data; Quantitative variables were described by means, and counts and percentages described qualitative variables. For univariate analysis, we used Student's T-test to compare two quantitative variables when a normal distribution and Mann-Whitney test were skewed. We used the Chi2 test and Fisher's exact test to compare the qualitative variables depending on whether the distribution is symmetric or not, respectively. In patients with COVID-19, we used X-tile tools to find cut-off points for assessing possible mortality risk factors. The subdistribution hazards ratio (SDHR) was determined with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The Kaplan-Meier method was used to measure overall survival (OS), and the log-rank test was used to compare outcomes. The difference is considered to be statistically significant when P < 0.05. The Institutional Ethics Committee gave its approval to this report.

Results

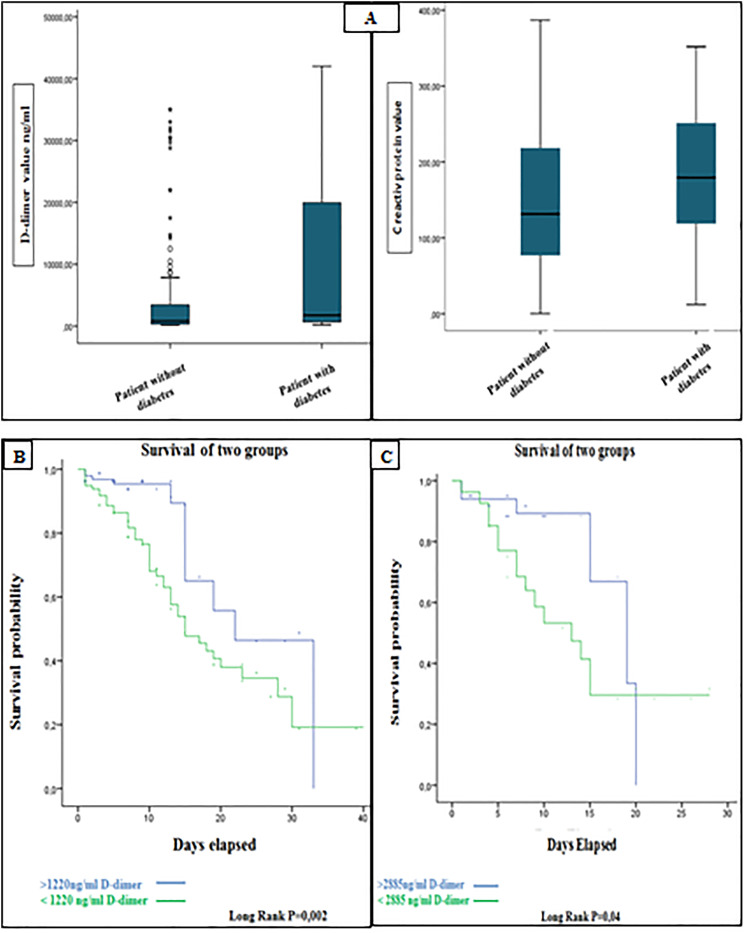

Of 201 hospitalized patients with COVID-19, the median age was 64 years (interquartile range, 56-73), and 113 (56%) were men. Chronic diseases, such as diabetes (36.6%) and hypertension (25,2%), were the most common underlying comorbidities. Patients with diabetes had more hypertension (42,9% vs 17,4%) and an elevated heart rate than patients without diabetes, but there were no major differences in gender and age (shown in Table 1). Additionally, the saturation of oxygen was low in the groups with diabetes mellitus but was not significantly statistically. We also found a significant difference between D-dimer and C reactive protein levels in COVID-19 in diabetic groups (Table 1), and the box plots of peak D-dimer levels and C reactive protein in patients with diabétes and without diabetes are shown in Figure (1A). We also found that COVID-19 patients with diabetes were initially hospitalized in the intensive care unit more than non-diabetic patients with a significant difference (P = 0,03).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients Infected with COVID-19.

| Characteristic | All

patients (n = 201) |

Diabetic

patients (n = 63) |

No-diabetic

patients (n = 138) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Median; IQR (years) | 64(56-73) | 68(61-76) | 63(54-72) | 0,10 |

| Genre male; no (%) | 113 (56%) | 35 (58,3%) | 78 (56,5%) | 0,46 |

| Hypertension; no (%) | 51 (25%) | 27 (42,9%) | 24 (17,4%) | <0001 |

| Underlying heart disease; no (%) | 18 (8,9%) | 8 (12,7%) | 10 (7,2%) | 0,16 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmhg) | 135 (145-122) | 140 (150-125) | 131 (143-120) | 0,09 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmhg) | 75 (80-70) | 75 (80-70) | 752(80-66,5) | 0,46 |

| Heart rate Mean (bpm) | 87 ± 12 | 92 ± 14,75 | 85 ± 11,56 | 0,02 |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | 77,50 (87%-66%) | 75 (88-65) | 80 (86-68) | 0,52 |

| Hospitalization in; no (%)intensive care unit | 130 (64,4%) | 47 (74,6%) | 83(60,1%) | 0,03 |

| Died; no (%) | 58 (28,7%) | 22 (34,9%) | 36 (26,1%) | 0,13 |

| D-dimer Median (ng/mL) | 1165 | 1745 | 845 | 0001 |

| D-dimer interquartile range (ng/mL) | 4037-430 | 20212-690 | 3460-320 | |

| CRP Mean (mg/L) | 157 ± 92 | 178 ± 87,91 | 147 ± 93,09 | 0029 |

| CRP Median (mg/L) | 145 | 179 | 131 | |

| CRP Interquartile range (mg/L) | 228-82 | 251-118 | 218-77 | |

| Ferritin median (ng/mL) | 850(1859-370) | 596 (1922-247) | 1149 (1841-406) | 0,35 |

| Fibrinogen Mean (g/L) | 6,37 ± 1,68 | 6,24 ± 1,64 | 6,43 ± 1,70 | 0,46 |

| Troponin Median (ng/L) | 24,90(78-6,6) | 39,80 (111-12) | 20,25 (69,05-5,95) | 0,09 |

Figure 1.

(A) Box and whisker plots of serum D-dimer and CRP peak concentrations measured in the patient with diabetes and patients without diabetes with COVID-19. (B) Survival curve for D-dimer levels in all patients with SARS-CoV-2. (C) Survival curve for D-dimer levels in diabetic patients with SARS-CoV-2.

Using the ROC curve, the optimal cut-off value at admission for D-dimer in all patients was 1220 ng/mL, with a sensitivity of 78% and a specificity of 62%. The region under the ROC curve (C-index) was 0.745. D-dimer levels of 1220 ng/mL were a significant indicator of subsequent mortality, according to Kaplan-Meier survival curves (Figure 1B). For D-dimer and diabetes, the cut-off value for predicting mortality was 2885 ng/mL, with a sensitivity of 71,4% and a specificity of 70,7%. The area under the ROC curve (C-index) was 0746 (Figure 1C).

Discussion

From the start of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic, diabetes emerged as one of the main comorbidities encountered in severe forms of COVID-19. A meta-analysis by Zhou et al., on 1527 COVID-19 patients showed that the prevalence of diabetes was 9.7%, and the incidence of diabetes in severe cases was about twice that of non-severe patients. 4

Our study discovered that D-dimer levels were significantly higher in diabetic patients, suggesting that they were more likely than patients without diabetes to have a hypercoagulable state. This can explain that hyperglycemia can cause a pro-thrombotic status, 5 according to two distinct pathways: the first path is oxidative stress, which improves thrombin production during acute hyperglycemia, the second path is non-glycation. Furthermore, enzymatic reduces the function of antithrombin III and heparin co-factor II;6,7 thus, persistent hyperglycemia may contribute to inflammation and endothelial dysfunction, leading to thrombus formation. In conclusion, hyperglycemia can lead to the formation of thrombi due to an imbalance between pro coagulation, anticoagulation and fibrinolysis.5,8,9 Furthermore, infection with pathogens elicits complex systemic inflammatory responses as part of innate immunity. Then activation of host defense systems results in subsequent activation of coagulation during the immune response to infection, overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines leading to multi-organ damage and generation of thrombin as components critical communication pathways between humoral and cellular amplification pathways. Severe hypoxia can directly activate thrombin and the activation of monocytes - macrophages, resulting in the secretion of tissue factors. This balance predisposes to the development of micro thrombosis; the disseminated intravascular coagulation demonstrated in severe COVID-19 pneumonia with high concentrations of d-dimers. 10

We further determined the D-dimer cut-off points to make this prognostic factor specific and then verified it using the Kaplan-Meier process. The results showed that D-dimer >2885 ng/mL was correlated with an increased risk of death in diabetic COVID-19 patients. However, studies have revealed that a higher D-dimer value upon admission indicated disease severity and the risk of mortality in the hospital for all patients. And the risk of developing a serious form of COVID-19-type pneumonia in diabetics is more severe since they tend to be at higher risk of an adverse outcome (multi-organ involvement, hypercoagulability and inflammatory). According to the Boli et al. report, the prevalence of diabetes in intensive care units was twice as high in COVID-19 patients. 11 In this study, we found that 74,6% of patients with diabetes were hospitalized in ICU admission. And another study conducted by Guan et al. in Wuhan found that 22% of patients with diabetes had an increased risk of death, admission to intensive care, and being on mechanical ventilation, in contrast to 6% in no-diabetic patients. 12 Overall, diabetes and high d-dimer are indicators of a poor prognosis. Still, the combination of the two will worsen the prognosis with progression to severe complications and death, which requires strict supervision and proper therapeutic treatment.

In addition, compared to people without diabetes, it is observed that some inflammation-related biomarkers are much higher in diabetic patients; this can also be attributed to people with diabetes already have baseline low-grade chronic inflammation, and their innate and adaptive immune systems are deregulated, making them more vulnerable to the cytokine storm, responsible for the poor prognosis and rapid deterioration of COVID-19, in agreement with our study, we found that CRP levels in diabetic patients were significantly higher than those in the patient without diabetes. 3

In the context of a single centre sample, our research was limited. Furthermore, our patients consisted of only moderate to severe COVID-19 patients. To confirm and analyze the clinical significance of these results, further studies will be required.

Conclusion

Diabetes is the most common comorbidity in patients with COVID-19, D-dimer and the inflammatory assessment have reliable parameters for evaluating the prognosis; and in addition D-dimers have an accurate and practical coagulation parameter for predicting mortality.

In our research we found a significant association of D-dimere and CRP levels with diabetes so a D-dimere value > 2885 ng/mL was found to be a predictor of mortality in diabetics with COVID-19. Finally, coagulopathy is a serious complication, particularly in diabetic patients.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Falmata Laouan Brem https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5742-0781

Chaymae Miri https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3752-0953

References

- 1.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727‐733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moyou E. Le coronavirus (COVID-19) - Faits et chiffres. Publié 15 mars 2021.

- 3.Apicella M, Campopiano MC, Mantuano M, et al. COVID-19 in people with diabetes: understanding the reasons for worse outcomes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol [Internet]. 2020;8(9):782e92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou W, Ye S, Wang W, et al. Clinical features of COVID-19 patients with diabetes and secondary hyperglycemia. J Diabetes Res. 2020;2020:1‐9. doi: 10.1155/2020/3918723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lemkes BA, Hermanides J, Devries JH, et al. Hyperglycemia: a prothrombotic factor? J Thromb Haemostasis. 2010;8(8):1663e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ceriello A, Giugliano D, Quatraro A, et al. Induced hyperglycemia alters antithrombin III activity but not its plasma concentration in healthy normal subjects. Diabetes. 1987;36(3):320e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ceriello A, Marchi E, Barbanti M, et al. Non-enzymatic glycation reduces heparin cofactor II anti-thrombin activity. Diabetologia.1990;33(4):205e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ceriello A, Quatraro A, Marchi E, et al. Impaired fibrinolytic response to increased thrombin activation in type 1 diabetes mellitus: effects of the glycosaminoglycan sulodexide. Diabete Metab. 1993;19(2):225e9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ceriello A. Diabetes, D-dimer and COVID-19: the possible role of glucose control. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews. 2020;14(6). doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo W, Li M, Dong Y, et al. Diabetes is a risk factor for the progression and prognosis of COVID-19 2020-07-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Li B, Yang J, Zhao F, et al. Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular metabolic diseases on COVID-19 in China. Clin Res Cardiol. 2020;109(5):531e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]