Abstract

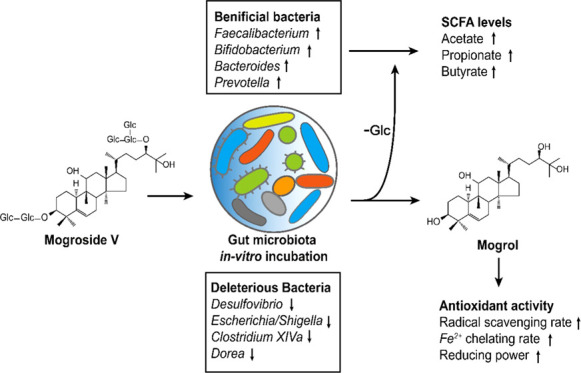

Mogroside V (MV), a sweetener, is one of the major components inSiraitia grosvenorii. In our research, after in vitro incubation with MV for 24 h, the human gut microbiota diversity changed, with an enrichment of the genera Bacteroides, Lactobacillus, Prevotella, Megasphaera, and Olsenella and the inhibition of Clostridium XlVa, Dorea, and Desulfovibrio. Moreover, the synthesis of short-chain fatty acids, such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate, was increased by gut microbiota. According to ultraperformance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS) analysis, MV was decomposed into secondary mogrosides, such as mogroside II/I and mogrol, by gut microbiota. Enhanced antioxidant abilities of the metabolites were found in the broth. The results suggested that MV, as a potential prebiotic, could benefit human health through its interaction with gut microbiota.

Introduction

Siraitia grosvenorii, called Luohanguo in southern China, is the fruit of lianas belonging to Cucurbitaceae and genus of Siraitia. The dried fruit is widely used for daily drinking and as traditional Chinese medicine. It contains various functional components, such as triterpenoids and flavonoids, among which the triterpene glycoside mogroside V (MV) is one of the major bioactive components, which is constructed by linking mogrol with five glucopyranosides.1 As an important sweetener source and food additive that is approximately 300 times sweeter than sucrose and low in calories, MV has been applied to food processes in China, Japan, and the United States.2,3 MV is considered to be a health-promoting functional component based on present in vitro research studies and animal experiments, it has been reported to decrease blood glucose level in HepG2 cells,4 lower blood lipid in diabetic mice,5 and exhibit antioxidative in vitro(5,6) and inhibitory effect of skin tumors in peroxynitrite- and 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-induced mouse.6 Recently, purified mogrosides (e.g., MV) derived from monk fruit extracts were reported to be metabolized in vitro by the gut microbiota to form a common and terminal deglycosylated metabolite, mogrol.7 Nevertheless, the effects of the interactions between MV and gut microbiota on human health are still unclear.

To date, the prebiotic functions of polysaccharides derived from plants and fungi have received wide attention.8,9 These components cannot be metabolized by the host directly; as a result, the gut microbiota helps to digest the nutrients to improve their bioavailabilities and functions.10 Past studies have reported the differences in the secondary metabolites produced from S. grosvenorii extract by gut microbiota of healthy and diabetic donors.11 However, the effects of MV on gut microbiota have received little attention. In the past few years, active plant components, such as hesperetin, have been confirmed to modulate gut microbiota diversity and affect host health by releasing multifarious metabolites or short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs),12 which are a series of products from gut microbial fermentation and possible signaling molecules that regulate host immunoreactions.13 For instance, dietary fiber supplementation with fermentable prebiotics in diabetic patients altered multiple bacterial metabolites and enriched SCFA-producing bacteria,14 which are known as potential probiotics. Polysaccharides from Dendrobium officinale were reported to relieve dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis, modulate SCFA levels, and contribute to microbiota abundance, such as Bacteroides, Lactobacillus, and Ruminococcaceae.15 Understandably, gut microbial diversity is closely connected with the metabolic diversity of xenobiotic compounds, since the microbial digestion of carbohydrates and their derivatives represents one of the most important forms of metabolism.16 There are thousands of glucoside hydrolases encoded in the gut microbial genome, especially in Bacteroides and Firmicutes, which account for 86% of the total amount of genes.17,18 These intestinal bacteria could help hydrolyze these polysaccharides into monosaccharides, the latter being an available substrate for fermentation by intestinal bacteria to produce SCFAs.

In our research, MV, a mogroside purified from S. grosvenorii, was digested by incubation with the gut microbiota in vitro to examine the effects of microbial composition with absolute copies of each bacterial taxon and SCFA production and formed metabolites that were detected by ultraperformance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS) to investigate the transformational significance of MV. The results provided an understanding of the potential prebiotic functions of MV.

Results and Discussion

Metabolism of MV by In Vitro Incubation with Gut Microbiota

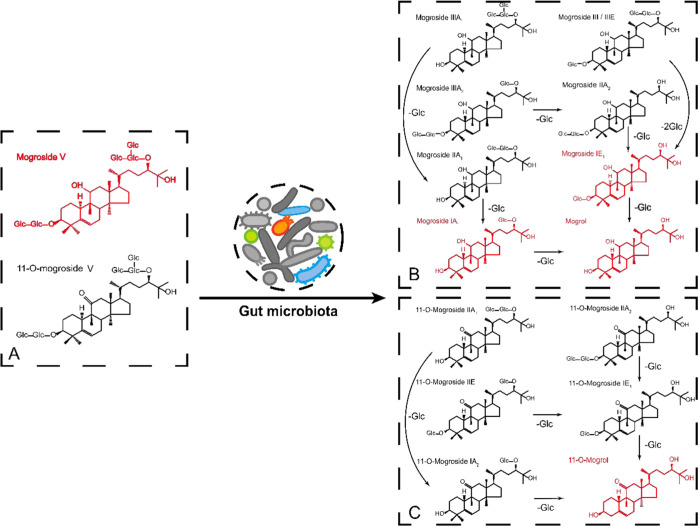

MV purified from S. grosvenorii, in which the purity of the MV powder was 90.08 ± 1.09%, was incubated in vitro with gut microbiota for 24 h. To observe the metabolism of MV, UPLC coupled with ultrahigh-resolution MS was used to detect the metabolites in the supernatant and sediment of the broth. As shown in Figure 1, MV was mainly identified in the broth before incubation. Then, the amount of MV dramatically decreased after incubation for 24 h, while some secondary metabolites appeared in the sediment, such as mogroside III, mogroside II, mogroside I, and mogrol. 11-O-Mogroside V, which had a low content, has a similar metabolic pathway to produce 11-O-mogrosides II and I and 11-O-mogrol. The MS response values of the other mogrosides are listed in Table S1. As a result, these metabolites gradually separated from the supernatant into the sediment of the broth over 24 h of incubation due to their reduced solubility. The results showed that deglycosylation of MV dominated the in vitro incubation by the gut microbiota. Interestingly, secondary mogrosides, such as mogroside IV, appeared in the broth during the first 6 h, but its content decreased afterward (Figure S1D), indicating that the microbial deglycosylation was a step-by-step process. Oxidization and dehydrogenation reactions were not found to occur, which verified that these metabolites of MV were more common in healthy donors.11 Similarly, in recent research, MV cultured with intestinal bacteria also produced these metabolites, among which 11-oxo-mogrol was identified to protect cultured neurons against MK801 treatment in vitro;19 however, 11-oxo-mogrol was not a major metabolite of MV in our research according to Table S1.

Figure 1.

Transformation of MV and 11-O-mogroside V by the gut microbiota. (A) Components in 0 h incubation broth. (B) Metabolites of MV after 24 h of incubation. (C) Metabolites of 11-O-mogroside V after 24 h of incubation. Compounds marked in red reflect the major components in the broth.

Previous studies have also reported that triterpene glycosides such as ginsenoside Rb1 could be hydrolyzed to 20(S)-protopanaxadiol and compound K, which can be well absorbed by gut epithelial cells and play a role with higher functional efficiency.20 Similar results were obtained in our study; metabolites containing mogroside III, II, and I showed available antihyperglycemic and antihyperlipidemic effects on T2DM rats. Moreover, mogrol, the most abundant component in the broth, helped alleviate colitis through the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and NF-κB pathways,21 suggesting that MV might be digested by the gut microbiota to generate metabolites that benefit human health.

Additionally, simulated digestion in saliva, gastric juice, and small intestinal juice was conducted to examine the stability of MV. The results suggested that MV could stably pass through saliva and simulated gastric and small intestinal conditions (Figure S1A–C). Humans lack β-glucoside hydrolase, which is encoded in the gut microbiota genome;22 therefore, it was speculated that MV might be metabolized not by the human digestive enzymes in vivo but commensal bacteria in the gut tract. However, due to the lack of bioavailability information of MV, the metabolic mechanism still needs to be verified by further pharmacokinetics research in vivo.

Modulation of Gut Microbiota Diversity by MV

The gut microbiota of the fecal slurry was anaerobically incubated in a basic nutrient growth medium (BNM) with MV and fructooligosaccharide (FOS), and a sample without any additive was set as a control. After 24 h of incubation, each sample was independently harvested to extract genomic DNA for 16S rRNA sequencing of the V3–V4 region. The rarefaction curve and Shannon curve indicated that the sequencing depth covered nearly all of the microorganisms, and principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) analysis reflected the significant difference between all treatment groups (Figure S2). Optimized sequences were clustered according to the similarity of 97% and blasted with the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) database to identify the taxa. The alpha diversity results are shown in Table 1. The Chao1, ACE, and Shannon indexes in the MV and FOS groups were significantly lower than those of the control group, while the Simpson index was higher in the FOS group. It was therefore suggested that the advantageous bacteria were enriched by the addition of MV.

Table 1. Alpha Diversity Parameters of Different Treatment Groupsa.

| groups | Chao1 | ACE | Shannon | Simpson |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 419.52 ± 12.15 a | 420.09 ± 12.50 a | 4.30 ± 0.02 a | (5.82 ± 0.35) × 10–2 a |

| FOS | 235.93 ± 34.67 b | 236.35 ± 34.78 b | 3.56 ± 0.04 c | (6.05 ± 0.13) × 10–2 a |

| MV | 259.62 ± 10.20 b | 260.04 ± 10.04 b | 3.74 ± 0.01 b | (5.03 ± 0.05) × 10–2 b |

Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) among different groups.

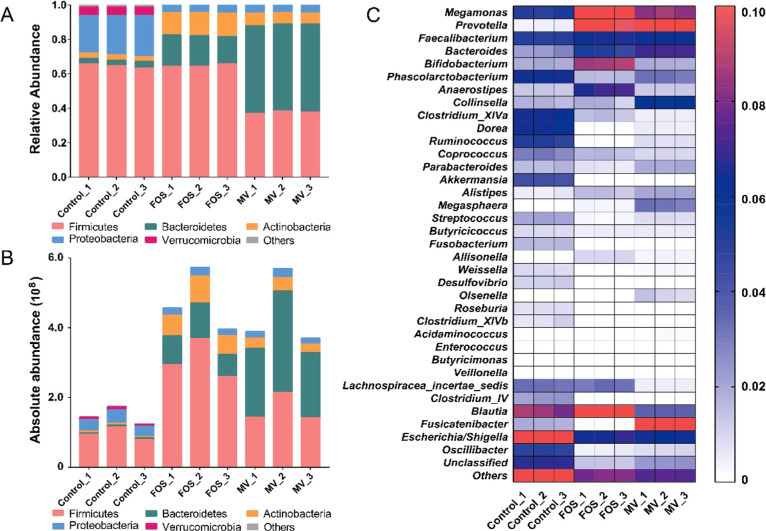

The relative differences in the gut microbiota after incubation with various media are presented in Figure 2A, and a bar plot was drawn from the data with microbes with an abundance greater than 1%. At the phylum level, the predominant taxa were Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, and Actinomycetes. In particular, the relative abundances of Actinomycetes and Bacteroidetes increased after MV addition, whereas those of Proteobacteria and Firmicutes decreased in the MV and FOS groups. By comparing the relative and absolute abundance results, however, a discrepant conclusion could be drawn due to the differences in absolute abundance among the MV, FOS, and control samples. For instance, as shown in Figure 2B, the absolute copies of total bacteria from both samples were significantly higher than that in the control, although the relative abundance of Firmicutes decreased in the sample with added MV. Therefore, the number of OTUs from Firmicutes increased in the sample with added MV, which presented the advantage of revealing actual microbial changes by absolute quantification of amplicon sequencing. Furthermore, we found that the addition of MV increased the abundance of Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Actinomycetes, while FOS only increased the abundance of Actinomycetes and Bacteroidetes. On the other hand, Proteobacteria was notably reduced in the samples with added MV. Similar results were also investigated in the latest study, additive of monk fruit extract in yogurt increased the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes and reduced Firmicutes and regulated blood glucose in rats with T2DM.23 Recently, a large-scale population study of gut microbiota showed that the majority of Proteobacteria were positively correlated to the occurrence of metabolic syndrome while most Bacteroidetes were more prevalent in healthy individuals,24 indicating the potential health functions of MV through the modulation of the gut microbiota composition.

Figure 2.

(A) Relative abundance of gut microbiota at the phylum level. (B) Absolute abundance (copy number) of gut microbiota at the phylum level. (C) Heat map of gut microbiota at the genus level. FOS.

At the genus level (Figure 2C), the taxa were mainly Bacteroides, Megamonas, Bifidobacterium, Prevotella, Blautia, and so on. Clearly, compared with the control, the relative abundances of Prevotella, Megamonas, Bacteroides, Olsenella, and Faecalibacterium were enriched in the MV-added sample. There were a few differences in the added FOS sample, in which Bifidobacterium, Anaerostipes, and Blautia were specifically enriched.

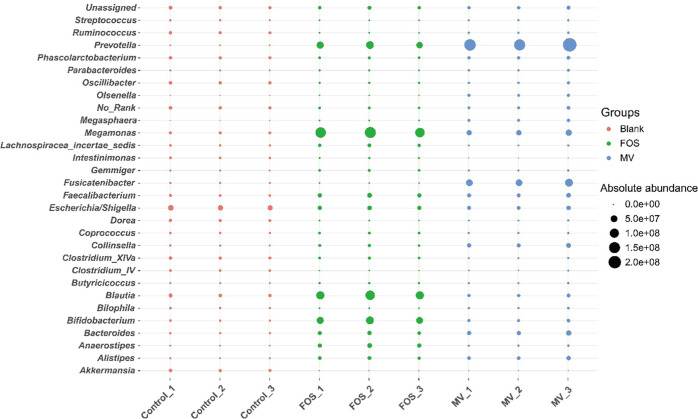

To illustrate the absolute copy differences in specific bacteria among samples, Figure 3 lists the top 30 significantly changed genera. The MV group obviously contributed to 12 taxa, mainly Megamonas, Faecalibacterium, Bacteroides, Megasphaera, Prevotella, Olsenella, and others. The integrated enriched bacteria were as follows: Bacteroides (10.31-fold), Lactobacillus (19.47-fold), Faecalibacterium (3.81-fold), Prevotella (421.90-fold), Megamonas (6.29-fold), Olsenella (243.76-fold), Megasphaera (3693.62-fold), Collinsella (10.07-fold), Fusicatenibacter (36.33-fold), Parabacteroides (3.51-fold), Alistipes (11.57-fold), and Allisonella (2564.42-fold). The bacteria whose relative abundances dramatically decreased were Clostridium XIVa, Dorea, Shigella, Desulfovibrio, and Fusobacterium. As reported by a previous survey,25 FOS could obviously enrich bacteria, including Prevotella and Bacteroides, as was observed in our study, which helped to hydrolyze and utilize the indigestible polysaccharides and simultaneously promote the growth of probiotics such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium in return. Similar results were also found in our study. MV significantly improved the amount of Faecalibacterium, Prevotella, and Bacteroides and slightly increased the abundance of Lactobacillus, which were identified to contain next-generation probiotic species and are positively connected with gut health.26Fucatenibacer was also found to be highly enriched in the MV group, but few studies have been done on this genus.

Figure 3.

Differences of absolute abundance of gut microbiota at genus level between MV, FOS, and control.

The high enrichment of B. uniformis from Bacteroides might be related to the hydrolysis of MV due to the β-glycosidase encoded in its bacterial genome.27 Another enriched species, B. vulgatus, was reported to reduce the production of lipopolysaccharide in the gut and suppress proinflammatory immune responses.28 In addition, supplementation with Faecalibacterium prausnitzii was confirmed to improve liver health and reduce inflammation in mice fed a high-fat diet.29 Although other enriched genera was reported to be connected with the fermentation of carbohydrates and known as SCFA-producing bacteria, such as Megasphaera and Megamonas,30,31 their probiotic function still remains to be confirmed. As for the reducing taxa, some species from Clostridium XIVa have been considered to contain opportunistic pathogens and are inhibited by fucosylated chondroitin sulfate.32Dorea and Desulfovibrio are considered proinflammatory genera,33,34 and the latter is a producer of H2S, which regulates inflammatory processes. Overall, the above results indicate that MV has potential prebiotic functions to improve health through interactions with the gut microbiota.

Enhancement of Short-Chain Fatty Acid Synthesis in the Gut Microbiota after the Addition of MV

As reported, bacteria from Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes contain the most glucoside hydrolases, which hydrolyze typical glucosides, such as xylan and arabinoxylan, and produce metabolites to enhance the growth of Bifidobacterium.35 This mechanism might explain the coenrichment of Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, and other genera. In addition, hydrolyzed glucosides act as an available substrate for bacteria, such as Faecalibacterium, Bacteroides, and Megasphaera, to produce SCFAs during anaerobic fermentation, mainly acetate, propionate, and butyrate.

To investigate the correlation between the metabolism of glucosides and the production of SCFAs in the gut microbiota, the contents of acetate, propionate, butyrate, isobutyrate, valerate, and isovalerate were determined in the above-mentioned three groups. As presented in Table 2, the contents of SCFAs significantly increased in the MV and FOS samples during 24 h of incubation. However, a difference in SCFAs was observed between the MV and FOS samples. The increase in acetate in the sample with added MV was significantly higher than that in the FOS sample after 24 h of incubation. The concentration of acetate in the FOS sample increased to 9.47 ± 0.34 mM, while that in MV increased to 15.34 ± 0.68 mM. For propionate, the FOS-added sample displayed an increase to 10.53 ± 0.79 mM, showing a significant difference from the sample with added MV. Moreover, butyrate in the MV sample obviously increased compared with the FOS sample during the last 12 h of incubation, reaching 6.98 ± 0.13 mM. In the latest research, a high dose of monk fruit extract in yogurt reinstated the concentration of acetate, propionate, and butyrate in T2DM rats, reflecting the potential correlation between mogrosides and host diseases since SCFAs were considered as health-related signaling molecules. For instance, acetate and butyrate possibly regulate the immune system through G-protein-coupled receptors 43 and 109A and modulate insulin sensitivity through fatty acid receptors FFAR2 and FFAR3.36,37 In addition, butyrate can be utilized as an energy source by epithelial cells.38 Propionate was thought to reduce lipogenesis and cholesterol levels.39 Other SCFAs, such as isobutyrate, valerate, and isovalerate, were inhibited in the FOS group but improved in the MV group after 24 h of incubation, suggesting that MV significantly promoted the yield of branched-chain fatty acids (BCFAs), a series of protein fermentation products produced by the gut microbiota. SCFAs in the intestinal tract also contributed to inhibiting the growth of pathogenic bacteria; for example, adding valerate could restrain the development of Clostridioides difficile.40 Nevertheless, the healthy function of BCFAs remains unknown. Consequently, MV contributed to the number of SCFA-producing bacteria and supplied an available substrate for microbial fermentation. The ability to increase SCFA levels provided a new understanding of MV to improve gut health.

Table 2. Concentrations of SCFAs in Incubation Solutions at Different Time Pointsa.

| anaerobic

incubation time (h) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCFAs (mM) | samples | 0 | 3 | 6 | 12 | 24 |

| acetate | control | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 1.02 ± 0.04 a | 2.14 ± 0.08 a | 2.89 ± 0.10 a | 4.16 ± 1.19 a |

| FOS | 1.89 ± 0.04 b | 4.22 ± 0.20 b | 7.78 ± 0.29 b | 9.47 ± 0.34 b | ||

| MV | 2.18 ± 0.50 b | 6.30 ± 0.28 c | 11.66 ± 0.56 c | 15.34 ± 0.68 c | ||

| propionate | control | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 0.84 ± 0.01 a | 1.61 ± 0.03 a | 2.98 ± 0.11 a | 2.68 ± 0.53 a |

| FOS | 3.78 ± 0.09 c | 11.11 ± 0.29 c | 10.18 ± 0.33 c | 10.53 ± 0.79 c | ||

| MV | 1.46 ± 0.08 b | 3.73 ± 0.10 b | 6.41 ± 0.22 b | 8.43 ± 0.28 b | ||

| butyrate | control | 0.33 ± 0.01 | 1.01 ± 0.01 a | 1.82 ± 0.02 a | 2.51 ± 0.05 a | 2.33 ± 0.06 a |

| FOS | 1.56 ± 0.01 b | 4.49 ± 0.07 c | 4.94 ± 0.08 b | 3.35 ± 0.12 b | ||

| MV | 1.53 ± 0.19 b | 3.42 ± 0.06 b | 5.63 ± 0.13 c | 6.98 ± 0.13 c | ||

| isobutyrate | control | M | nd | 0.04 ± 0.01 a | 0.95 ± 0.02 b | 1.01 ± 0.02 b |

| FOS | nd | nd | nd | nd | ||

| MV | nd | 0.08 ± 0.01 b | 0.16 ± 0.01 a | 0.15 ± 0.01 a | ||

| valerate | control | nd | nd | 0.10 ± 0.01 a | 0.39 ± 0.05 c | 0.22 ± 0.03 b |

| FOS | 0.05 ± 0.01 a | 0.09 ± 0.01 a | 0.10 ± 0.01 a | 0.06 ± 0.01 a | ||

| MV | nd | 0.11 ± 0.01 a | 0.22 ± 0.01 b | 0.31 ± 0.01 c | ||

| isovalerate | control | nd | nd | 0.29 ± 0.01 b | 2.17 ± 0.03 c | 2.24 ± 0.01 c |

| FOS | nd | 0.05 ± 0.01 a | 0.06 ± 0.01 a | 0.08 ± 0.05 a | ||

| MV | nd | 0.30 ± 0.01 b | 0.53 ± 0.01 b | 0.58 ± 0.01 b | ||

Different lowercase letters indicate significances (P < 0.05) among groups; nd, not detected.

Enhancement of MV Antioxidation after In Vitro Incubation with Gut Microbiota

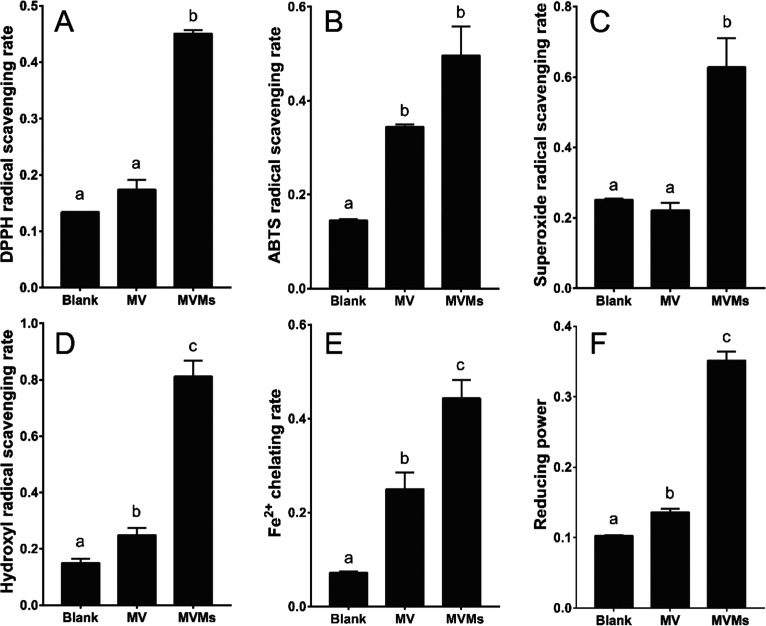

Free radicals are a general product of biochemical reactions in the body. However, superfluous radicals are likely to induce tissue damage or the development of host diseases.41 Plant active components, such as ginsenosides, have been verified to protect the host from an oxidative stress injury.42 Similarly, triterpenes have been reported to have potential antioxidant activity.43 Here, the antioxidant activity of MV and its metabolites mogroside V metabolite (MVMs) after in vitro incubation with gut microbiota were examined by 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity, hydroxyl radical scavenging activity, superoxide radical scavenging activity, [2,2-azinobis-(3-ethyl-benzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)] diammonium salt (ABTS) radical scavenging activity, Fe2+ chelating activity, and total reducing power.

After in vitro incubation of the gut microbiota for 24 h, there was a dramatic rise in metabolites, as described in Table S1, and the antioxidant index, as presented in Figure 4A–F. The DPPH radical scavenging rate increased from 17.38 ± 1.75 to 45.11 ± 0.57% (P < 0.05), the hydroxyl radical scavenging rate increased from 24.88 ± 2.52 to 81.18 ± 5.60% (P < 0.05), the superoxide radical scavenging rate increased from 22.12 ± 2.14 to 62.82 ± 8.18% (P < 0.05), the ABTS radical scavenging rate increased from 34.42 ± 0.53 to 49.66 ± 6.11% (P < 0.05), the Fe2+ chelating rate increased from 25.01 ± 3.58 to 44.35 ± 3.85% (P < 0.05), and the total reducing power improved from 13.62 ± 0.52 to 35.16 ± 1.26% (P < 0.05). In recent decades, free radicals have been considered to be able to react with biological macromolecules such as DNA, membrane lipids, and proteins, causing oxidative modifications and loss of function.44 For MVMs, the scavenging rate of hydroxyl radicals, known as one of the most reactive free radicals, was nearly 3.3-fold higher than that of MV. Scavenging of DPPH, ABTS, and superoxide radicals also improved by 2.6-, 1.4-, and 2.8-fold, respectively, suggesting a promotion in the radical scavenging functions of MVMs. Fe2+ was active in the oxidation bioreaction and connected with radicals produced through the Fenton reaction. As presented in Figure 4E,F, the MVMs also showed stronger ferrous ion chelating activity and total reducing power than MV. Furthermore, 0.02 M mogrol and MV were compared to confirm the increased antioxidant activity of major metabolites. The data from Figure S3A–F suggest that the scavenging of DPPH, ABTS, superoxide, and hydroxyl radicals by mogrol are 1.3-, 1.3-, 6.0-, and 1.4-fold than that by MV, respectively, the Fe2+ chelating rate and the reducing power of mogrol were 1.8- and 1.4-fold than that of MV, respectively, indicating that the enhanced antioxidant activity was related to the improved concentration of mogrol after 24 h of microbial incubation. However, the improved antioxidant activity seems not completely resulted from the production of mogrol. For instance, the DPPH and hydroxy radical scavenging rates of MVMs were higher than that of mogrol. A similar result was also found for the reducing power. These differences might be caused by the multiple antioxidant components in MVMs such as mogroside I and 11-O-mogrol, since the antioxidant activity was related to the position and numbers of hydroxy, steric effects, and molecular properties.45 The above results suggested that MVMs likely possess stronger bioactivities to protect gut homeostasis after degradation by the gut microbiota, for example, MV and 11-oxo-mogrol (one of the MV metabolites) prevented from the neuronal damages induced by dizocilpine maleate (MK801);19 nevertheless, the in vivo therapeutic effect of MV and its metabolites should be further revealed. Structurally, because most metabolites resulted from the deglycosylation of MV with the action of β-glucosaccharase encoded in the gut microbiota genome, it was possible that the increase in antioxidant ability might be connected to the positions of the hydroxy groups and their bond dissociation enthalpy.46 In summary, the production of stronger antioxidative metabolites from gut microbiota was investigated from a novel perspective to illustrate the healthy functions of MV.

Figure 4.

Differences between the antioxidant activities of MV and MVMs in (A) DPPH radical scavenging rate, (B) ABTS radical scavenging rate, (C) superoxide radical scavenging rate, (D) hydroxyl radical scavenging rate, (E) Fe2+ chelating rate, and (F) reducing power.

Conclusions

MV could be metabolized by gut microbiota into secondary mogrosides that have stronger antioxidant abilities for gut health but cannot be digested by saliva, simulated gastric juice, or small intestinal juice. During gut microbial fermentation, the glucosides released from the deglycosylation of MV promoted the growth of Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides, Prevotella, Lactobacillus, Mitsuokella, Selenomonas, Megasphaera, and so on and reduced the potential pathogenic genera Dorea and Clostridium XIVa. Additionally, these glucosides serve as substrates to produce SCFAs, especially acetate, propionate, and butyrate. It was speculated that MV could safely reach the large intestine in vivo and modulate the gut microecosystem to produce SCFAs. MV has potential benefits to human health through interactions with gut microbiota and shows promise for development as a prebiotic food.

Materials and Methods

Materials and Chemicals

The MV in this study was provided by Guilin Sanling Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (Guangxi Province, China) and was extracted and purified from S. grosvenorii (the purity of MV was further identified in the next section). The MV standard was purchased from DeSiTe Biological Technology Co. Ltd. (Chengdu, China). Fructooligosaccharide was purchased from Qiyun Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). Pepsin and trypsin were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., Ltd. (St. Louis, MO). Pancreatin and lipase were obtained from Yuanye Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). [2,2-Azinobis-(3-ethyl-benzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)] diammonium salt (ABTS), 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), phenazine methosulfate (PMS), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT), and salicylic acid were purchased from Newprobe Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Standards of SCFAs (acetic, propionic, butyric, isobutyric, valeric, and isovaleric acids) and all other chemicals were obtained from Aladdin Industrial Inc. (Shanghai, China).

MV Quantification

A Waters high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Waters, Milford, MA) was used to quantitatively detect MV. A Shimadzu Inertsil ODS-3 C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm2, 5 μm) and an ultraviolet detector were used in this study. Other parameters were as follows: The column oven was 35 °C, the mobile phases were water with 0.1% phosphoric acid (A) and acetonitrile (B), and the flow rate was 1 mL/min. The linear gradient conditions were 15–40% B (0–30 min) and 40% B (30–40 min). The injection volume was 10 μL. The detector wavelength was set to 210 nm.

Simulated Saliva Digestion

Simulated saliva digestion followed the method reported in a previous study with a slight adjustment.47 Fresh saliva was collected from four healthy participants who did not take any antibiotics in the 3 months prior. They were required to rinse their mouths and discard the first minute of saliva. After collection, the saliva was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min to collect the supernatant. An MV solution was prepared at 10 mg/mL. Three groups were set for the experiment: (1) 4 mL of saliva was mixed with 4 mL of MV; (2) 4 mL of saliva was mixed with 4 mL of deionized water; and (3) 4 mL of MV was mixed with 4 mL of deionized water. All reaction tubes were kept in a water bath at 37 °C. After 0, 0.5, 1, and 2 h, the samples were collected to measure the consumption of MV by HPLC.

Simulated Gastric Digestion

The simulated gastric digestion method was assembled according to a previous study with a slight adjustment.48 The gastric electrolyte solution (GES; 200 mL) contained 0.62 g of NaCl, 0.22 g of KCl, 0.05 g of CaCl2, and 0.12 g of NaHCO3. Then, 1.0 mL of CH3COONa (1.0 mol/L, pH 5), 23.6 mg of gastric pepsin, and 25 mg of gastric lipase were added to 100 mL of GES, and the pH of the mixture was adjusted to 3.0 with a 0.1 M HCl solution to obtain the gastric juice. Three groups were set for the experiment: (1) 8 mL of gastric juice was mixed with 8 mL of MV; (2) 8 mL of gastric juice was mixed with 8 mL of deionized water; and (3) 8 mL of MV was mixed with 8 mL of deionized water. The reaction tubes were kept in a water bath at 37 °C. After 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 6 h, the samples were collected to measure the consumption of MV by HPLC.

Simulated Small Intestinal Digestion

The simulated small intestinal digestion method was conducted according to a previous study with a slight adjustment.47 The intestinal electrolyte solution (IES; 100 mL) contained 0.54 g of NaCl, 0.065 g of KCl, and 0.033 g of CaCl2, and the pH of the IES was adjusted to 7.0 with a 0.1 M NaOH solution. Then, 200 mL of bile salt solution (4%, w/v), 50 mL of pancreatin solution (7%, w/v), and 6.5 mg of trypsin were mixed with 50 mL of IES, and the mixture was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was collected, and the pH was adjusted to 7.5 with a 0.1 M NaOH solution to obtain the intestinal juice. The reaction systems were set at a ratio of 10:3 (v/v), and the mixture composition, sampling, and detection of MV were carried out as described in section 2.3.

In Vitro MV Incubation with the Gut Microbiota

Fecal sample collection methods were approved by the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (Guangzhou, China). Fecal samples were obtained from four healthy participants (two males and two females) aged 20–26 years, and none of them had a history of antibiotic use within the 3 months prior to this research. The fecal samples were premixed and evenly resuspended in 10 volumes (w/v) phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (0.1 M, pH 7.0) to obtain a mixed fecal slurry. The in vitro incubation of MV by the gut microbiota followed the method reported in a previous study, with a slight adjustment.32 In brief, the microbial community incubation was based on a basic nutrient growth medium (BNM): 2.0 g/L yeast extract, 2.0 g/L peptone, 0.1 g/L NaCl, 0.04 g/L KH2PO4, 0.04 g/L K2HPO4, 0.01 g/L MgSO4·7H2O, 0.01 g/L CaCl2, 2 g/L NaHCO3, 0.02 g/L hemin, 0.5 g/L cysteine-HCl, 0.5 g/L bile salts, 2.0 mL/L Tween 80, 1.0 mL/L 1% resazurin solution, and 10 μL/L vitamin K solution. Then, MV and fructooligosaccharide (FOS; positive control) were added to the BNM medium at final concentrations of 10 mg/mL, and the group with neither MV nor FOS was set as the control. One milliliter of the mixed fecal slurry was inoculated in an airtight serum bottle with 25 mL of BNM broth each group was inoculated in triplicate as parallel experiments. Incubation was carried out under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C, and at 0, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h, the samples were collected for further study. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

UPLC-MS Detection of MV Metabolites

Mass spectrometry analysis was carried out with a high-resolution Q Exactive Plus Orbitrap MS system connected to a Dionex Ultimate 3000 UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). MV and its metabolites were separated on the UPLC system equipped with a Hypersil GOLD C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm2, 1.9 μm; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The mobile phase was 0.1% formic acid (v/v, solvent A) and methanol (solvent B) with an injection volume of 5 μL, and the flow rate was 0.35 mL/min. The gradient process was as follows: 0–1 min, 2% solvent B (held for 1 min); 1–9 min, from 2 to 98% solvent B; and 9–12 min, 98% solvent B (held for 3 min). The column oven was set to 35 °C. The electrospray ionization (ESI) parameters were set as follows: spray voltage, 3 kV; capillary temperature, 320 °C; sheath gas flow rate, 40 L/h; aux gas flow rate, 10 L/h; and scan range, m/z 133.4 to 2000. Ionization was conducted in the negative-ion mode. All data obtained were analyzed by Compound Discovery software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and the results were compared with those of a previous data set.49

Detection of Antioxidant Activities of MV Metabolites In Vitro

Detection of Radical Scavenging Activity

The scavenging rates of DPPH, ABTS+, hydroxyl, and superoxide radicals were measured according to the previous research.50 MV and its 24 h metabolites were dissolved in methanol to afford 10 mg/mL solutions. The antioxidant activities are expressed as the percent scavenging rate calculated by the following formula

where abs0 is the abs of the control, abs1 is the abs of the samples, and abs2 is the abs under the same conditions as those of abs1 after replacing the radical solution with the control.

Detection of Fe2+ Chelating Activity

The Fe2+ chelating rate was measured by a reported assay with a slight adjustment.50 Briefly, 50 μL of the sample, 2.5 μL of FeCl2 (3.0 mM), and 10 μL of ferrozine (5.0 mM) were mixed with 137 μL of distilled water and incubated for 10 min at 25 °C. The Abs was then measured at 562 nm.

where abs0 is the abs of diluted water (instead of the sample), abs1 is the abs of the sample, and abs2 is the abs of the identical conditions as those of abs1 after replacing FeCl2 with distilled water.

Detection of Reducing Power

The reducing power was measured according to past research with minor modifications.51 In brief, 50 μL of the sample, 50 μL of K3Fe(CN)6 (1%, w/v), and 50 μL of PBS (0.2 M, pH = 6.6) were mixed in a 96-well plate and incubated for 20 min at 50 °C. Then, 50 μL of ferric trichloride and 30 μL of FeCl3 (0.1%, w/v) were added for termination and coloration, and the Abs was measured at 700 nm.

where abs1 is the abs of the sample and abs2 is the abs of the identical conditions as those of abs1 after replacing FeCl3 with distilled water.

Absolute Quantity Sequencing of 16S rRNA Amplicons

Absolute quantification of 16S rRNA and basic data quality control were performed with a commercial kit from Genesky Biotechnologies Inc. (Shanghai, China). Briefly, total genomic DNA was extracted using the PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (MoBio, Carlsbad). Bacterial genomic DNA was used as a template to amplify the V3–V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene with the forward primer (5′-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′) and the reverse primer (5′-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′). For absolute quantification, multiple spike-ins with conserved regions identical to the 16S rDNA and variable regions replaced by random sequences with ∼40% gas chromatography (GC) content were artificially synthesized, and an appropriate mixture with known gradient copy numbers of spike-ins was added to the sample DNA pools. All OTUs were then annotated based on the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP). Rarefaction analysis, alpha diversities (including the Shannon, Simpson, Chao1, and ACE indexes), and beta diversities were analyzed by R Project (Vegan package, V3.3.1).

SCFA Detection by Gas Chromatography (GC)

An Agilent 7820A GC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) was equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID), and a DB-FFAP capillary column (Agilent, 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) was used for component separation. The operating temperature conditions of the GC system were as follows: initial column temperature was 80 °C (held for 1 min), then increased from 80 to 160 °C at a rate of 3 °C/min, and finally increased from 160 to 230 °C, which was held for 1 min. Other parameters were set as follows: injection port temperature, 300 °C; FID temperature, 320 °C; and injection volume, 1 μL. The flow rates of dry air, hydrogen, and nitrogen were 300, 30, and 20 mL/min, respectively. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Statistical Analysis

The experimental data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of triplicate measurements. All data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 7.0 software, and the significance level of multiple comparisons was calculated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. P < 0.05 was regarded as a statistically significant difference.

Acknowledgments

All of the authors are thankful for the financial support of the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2017YFD0400300) and the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2018B020205002).

Glossary

Abbreviations Used

- MV

mogroside V

- FOS

fructooligosaccharide

- BNM

basic nutrition growth medium

- SCFAs

short-chain fatty acids

- MVMs

mogroside V metabolites

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c03485.

High-performance liquid chromatography of MV after digestion of saliva, simulated gastric, and intestinal juice; UPLC-MS response value of MV and MVMs after in vitro incubation; and rarefaction curves, Shannon curves, and PCoA analysis of each treatment group (PDF)

Author Contributions

R.X. (first author) carried out and designed most of the experiments, analyzed microbiome and metabolic data, and composed the manuscript. W.L. helped organized data and carried out GC analysis of the short-chain fatty acids of incubation samples. G.L. helped collect the feces samples and organized the ethical review document and instructed the first author to conducted UPLC-MS. Z.Q. helped plot and incubation. Y.L. and S.H. were supervisors to design the project and revised the manuscript for publication.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Xia Y.; Riverohuguet M.; Hughes B.; Marshall W. Isolation of the sweet components from Siraitia grosvenorii. Food Chem. 2008, 107, 1022–1028. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.09.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pawar R. S.; Krynitsky A. J.; Rader J. I. Sweeteners from plants–with emphasis on Stevia rebaudiana (Bertoni) and Siraitia grosvenorii (Swingle). Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2013, 405, 4397–407. 10.1007/s00216-012-6693-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Additives E. P. oF.; Flavourings; Younes M.; Aquilina G.; Engel K. H.; Fowler P.; Frutos Fernandez M. J.; Furst P.; Gurtler R.; Gundert-Remy U.; Husoy T.; Mennes W.; Moldeus P.; Oskarsson A.; Shah R.; Waalkens-Berendsen I.; Wolfle D.; Degen G.; Herman L.; Gott D.; Leblanc J. C.; Giarola A.; Rincon A. M.; Tard A.; Castle L. Safety of use of Monk fruit extract as a food additive in different food categories. EFSA J. 2019, 17, e05921 10.2903/j.efsa.2019.5921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.; Zhang J.; Li Y.; Sun L.; Xiao Y.; Gao W.; Zhang Z. Mogroside derivatives exert hypoglycemics effects by decreasing blood glucose level in HepG2 cells and alleviates insulin resistance in T2DM rats. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 63, 103566 10.1016/j.jff.2019.103566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qi X. Y.; Chen W. J.; Zhang L. Q.; Xie B. J. Mogrosides extract from Siraitia grosvenori scavenges free radicals in vitro and lowers oxidative stress, serum glucose, and lipid levels in alloxan-induced diabetic mice. Nutr. Res. 2008, 28, 278–284. 10.1016/j.nutres.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takasaki M.; Konoshima T.; Murata Y.; Sugiura M.; Nishino H.; Tokuda H.; Matsumoto K.; Kasai R.; Yamasaki K. Anticarcinogenic activity of natural sweeteners, cucurbitane glycosides, from Momordica grosvenori. Cancer Lett. 2003, 198, 37–42. 10.1016/S0304-3835(03)00285-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.; Dai L.; Liu Y.; Dou D.; Sun Y.; Ma L. Pharmacological activities of mogrosides. Future Med. Chem. 2018, 10, 845–850. 10.4155/fmc-2017-0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng M.; Tabashsum Z.; Anderson M.; Truong A.; Houser A. K.; Padilla J.; Akmel A.; Bhatti J.; Rahaman S. O.; Biswas D. Effectiveness of probiotics, prebiotics, and prebiotic-like components in common functional foods. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 1908–1933. 10.1111/1541-4337.12565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales D.; Shetty S. A.; Lopez-Plaza B.; Gomez-Candela C.; Smidt H.; Marin F. R.; Soler-Rivas C. Modulation of human intestinal microbiota in a clinical trial by consumption of a beta-D-glucan-enriched extract obtained from Lentinula edodes. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 3249–3265. 10.1007/s00394-021-02504-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J.; Chen H. B.; Li S. L. Understanding the Molecular Mechanisms of the Interplay Between Herbal Medicines and Gut Microbiota. Med. Res. Rev. 2017, 37, 1140–1185. 10.1002/med.21431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G.; Peng Y.; Zhao L.; Wang M.; Li X. Biotransformation of Total Saponins in Siraitia Fructus by Human Intestinal Microbiota of Normal and Type 2 Diabetic Patients: Comprehensive Metabolite Identification and Metabolic Profile Elucidation Using LC-Q-TOF/MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 1518–1524. 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b04498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unno T.; Hisada T.; Takahashi S. Hesperetin Modifies the Composition of Fecal Microbiota and Increases Cecal Levels of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 7952–7. 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b02649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh A.; De Vadder F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary P.; Backhed F. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L.; Zhang F.; Ding X.; Wu G.; Lam Y. Y.; Wang X.; Fu H.; Xue X.; Lu C.; Ma J.; Yu L.; Xu C.; Ren Z.; Xu Y.; Xu S.; Shen H.; Zhu X.; Shi Y.; Shen Q.; Dong W.; Liu R.; Ling Y.; Zeng Y.; Wang X.; Zhang Q.; Wang J.; Wang L.; Wu Y.; Zeng B.; Wei H.; Zhang M.; Peng Y.; Zhang C. Gut bacteria selectively promoted by dietary fibers alleviate type 2 diabetes. Science 2018, 359, 1151–1156. 10.1126/science.aao5774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Wu Z.; Liu J.; Zheng Z.; Li Q.; Wang H.; Chen Z.; Wang K. Identification of the core active structure of a Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide and its protective effect against dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis via alleviating gut microbiota dysbiosis. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109641 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppel N.; Maini Rekdal V.; Balskus E. P. Chemical transformation of xenobiotics by the human gut microbiota. Science 2017, 356, eaag2770 10.1126/science.aag2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Kaoutari A.; Armougom F.; Gordon J. I.; Raoult D.; Henrissat B. The abundance and variety of carbohydrate-active enzymes in the human gut microbiota. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 497–504. 10.1038/nrmicro3050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwalm N. D. 3rd; Groisman E. A. Navigating the Gut Buffet: Control of Polysaccharide Utilization in Bacteroides spp. Trends Microbiol. 2017, 25, 1005–1015. 10.1016/j.tim.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju P.; Ding W.; Chen J.; Cheng Y.; Yang B.; Huang L.; Zhou Q.; Zhu C.; Li X.; Wang M.; Chen J. The protective effects of Mogroside V and its metabolite 11-oxo-mogrol of intestinal microbiota against MK801-induced neuronal damages. Psychopharmacology 2020, 237, 1011–1026. 10.1007/s00213-019-05431-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H.; Gao X. J.; Li T.; Jing W. H.; Han B. L.; Jia Y. M.; Hu N.; Yan Z. X.; Li S. L.; Yan R. Ginseng polysaccharides enhanced ginsenoside Rb1 and microbial metabolites exposure through enhancing intestinal absorption and affecting gut microbial metabolism. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 216, 47–56. 10.1016/j.jep.2018.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H.; Cheng R.; Wang J.; Xie H.; Li R.; Shimizu K.; Zhang C. Mogrol, an aglycone of mogrosides, attenuates ulcerative colitis by promoting AMPK activation. Phytomedicine 2021, 81, 153427 10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabek M.; McCrae S. I.; Stevens V. J.; Duncan S. H.; Louis P. Distribution of beta-glucosidase and beta-glucuronidase activity and of beta-glucuronidase gene gus in human colonic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2008, 66, 487–495. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban Q.; Cheng J.; Sun X.; Jiang Y.; Zhao S.; Song X.; Guo M. Effects of a synbiotic yogurt using monk fruit extract as sweetener on glucose regulation and gut microbiota in rats with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 2956–2968. 10.3168/jds.2019-17700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y.; Wu W.; Wu S.; Zheng H. M.; Li P.; Sheng H. F.; Chen M. X.; Chen Z. H.; Ji G. Y.; Zheng Z. D.; Mujagond P.; Chen X. J.; Rong Z. H.; Chen P.; Lyu L. Y.; Wang X.; Xu J. B.; Wu C. B.; Yu N.; Xu Y. J.; Yin J.; Raes J.; Ma W. J.; Zhou H. W. Linking gut microbiota, metabolic syndrome and economic status based on a population-level analysis. Microbiome 2018, 6, 172 10.1186/s40168-018-0557-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarino M.; Altomare A.; Emerenziani S.; Di Rosa C.; Ribolsi M.; Balestrieri P.; Iovino P.; Rocchi G.; Cicala M. Mechanisms of Action of Prebiotics and Their Effects on Gastro-Intestinal Disorders in Adults. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1037 10.3390/nu12041037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole P. W.; Marchesi J. R.; Hill C. Next-generation probiotics: the spectrum from probiotics to live biotherapeutics. Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 2, 17057 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellock S. J.; Walton W. G.; Biernat K. A.; Torres-Rivera D.; Creekmore B. C.; Xu Y.; Liu J.; Tripathy A.; Stewart L. J.; Redinbo M. R. Three structurally and functionally distinct beta-glucuronidases from the human gut microbe Bacteroides uniformis. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 18559–18573. 10.1074/jbc.RA118.005414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida N.; M T E M. D.; Tomoya Yamashita M. D.; Watanabe H.; Hayashi T.; Tabata T.; Hoshi N.; Hatano N.; Ozawa G.; Sasaki N.; Mizoguchi T.; Amin H. Z.; Hirota Y.; Ogawa W.; Yamada T.; Hirata K.-i. Bacteroides vulgatus and Bacteroides dorei Reduce Gut Microbial Lipopolysaccharide Production and Inhibit Atherosclerosis. Circulation 2018, 138, 2486–2498. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.033714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munukka E.; Rintala A.; Toivonen R.; Nylund M.; Yang B.; Takanen A.; Hanninen A.; Vuopio J.; Huovinen P.; Jalkanen S.; Pekkala S. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii treatment improves hepatic health and reduces adipose tissue inflammation in high-fat fed mice. ISME J 2017, 11, 1667–1679. 10.1038/ismej.2017.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang D.; Li N.; Dai X.; Zhang H.; Hu H. Effects of different types of potato resistant starches on intestinal microbiota and short-chain fatty acids under in vitro fermentation. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 2432–2442. 10.1111/ijfs.14873. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Metzler-Zebeli B. U.; Newman M. A.; Ladinig A.; Kandler W.; Grull D.; Zebeli Q. Transglycosylated starch accelerated intestinal transit and enhanced bacterial fermentation in the large intestine using a pig model. Br. J. Nutr. 2019, 122, 1–13. 10.1017/S0007114519000849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mou J.; Li Q.; Shi W.; Qi X.; Song W.; Yang J. Chain conformation, physicochemical properties of fucosylated chondroitin sulfate from sea cucumber Stichopus chloronotus and its in vitro fermentation by human gut microbiota. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 228, 115359 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan P. D.; Shanahan F.; Marchesi J. R. Culture-independent analysis of desulfovibrios in the human distal colon of healthy, colorectal cancer and polypectomized individuals. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2009, 69, 213–221. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Q.; Jiang H.; Cai C.; Hao J.; Li G.; Yu G. Gut microbiota fermentation of marine polysaccharides and its effects on intestinal ecology: An overview. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 179, 173–185. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogowski A.; Briggs J. A.; Mortimer J. C.; Tryfona T.; Terrapon N.; Lowe E. C.; Basle A.; Morland C.; Day A. M.; Zheng H.; Rogers T. E.; Thompson P.; Hawkins A. R.; Yadav M. P.; Henrissat B.; Martens E. C.; Dupree P.; Gilbert H. J.; Bolam D. N. Glycan complexity dictates microbial resource allocation in the large intestine. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7481 10.1038/ncomms8481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macia L.; Tan J.; Vieira A. T.; Leach K.; Stanley D.; Luong S.; Maruya M.; Ian McKenzie C.; Hijikata A.; Wong C.; Binge L.; Thorburn A. N.; Chevalier N.; Ang C.; Marino E.; Robert R.; Offermanns S.; Teixeira M. M.; Moore R. J.; Flavell R. A.; Fagarasan S.; Mackay C. R. Metabolite-sensing receptors GPR43 and GPR109A facilitate dietary fibre-induced gut homeostasis through regulation of the inflammasome. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6734 10.1038/ncomms7734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vadder F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary P.; Goncalves D.; Vinera J.; Zitoun C.; Duchampt A.; Backhed F.; Mithieux G. Microbiota-generated metabolites promote metabolic benefits via gut-brain neural circuits. Cell 2014, 156, 84–96. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford A.; Gong J. Implications of butyrate and its derivatives for gut health and animal production. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 4, 151–159. 10.1016/j.aninu.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini E.; Grootaert C.; Verstraete W.; Van de Wiele T. Propionate as a health-promoting microbial metabolite in the human gut. Nutr. Rev. 2011, 69, 245–258. 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald J. A. K.; Mullish B. H.; Pechlivanis A.; Liu Z.; Brignardello J.; Kao D.; Holmes E.; Li J. V.; Clarke T. B.; Thursz M. R.; Marchesi J. R. Inhibiting Growth of Clostridioides difficile by Restoring Valerate, Produced by the Intestinal Microbiota. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 1495–1507.e15. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young I. S.; Woodside J. V. Antioxidants in health and disease. J. Clin. Pathol. 2001, 54, 176–186. 10.1136/jcp.54.3.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G. D.; Zhong X. F.; Deng Z. Y.; Zeng R. Proteomic analysis of ginsenoside Re attenuates hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 2451–2461. 10.1039/C6FO00123H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W. J.; Wang J.; Qi X. Y.; Xie B. J. The antioxidant activities of natural sweeteners, mogrosides, from fruits of Siraitia grosvenori. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2007, 58, 548–556. 10.1080/09637480701336360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Meo S.; Venditti P. Evolution of the Knowledge of Free Radicals and Other Oxidants. Oxid. Med. Cell Longevity 2020, 2020, 1–32. 10.1155/2020/9829176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos S. C.; Fortes G. A. C.; Camargo L. T. F. M.; Camargo A. J.; Ferri P. H. Antioxidant effects of polyphenolic compounds and structure-activity relationship predicted by multivariate regression tree. LWT 2021, 137, 110366 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.110366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y. Z.; Deng G.; Liang Q.; Chen D. F.; Guo R.; Lai R. C. Antioxidant Activity of Quercetin and Its Glucosides from Propolis: A Theoretical Study. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7543 10.1038/s41598-017-08024-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G.; Xie M.; Wan P.; Chen D.; Ye H.; Chen L.; Zeng X.; Liu Z. Digestion under saliva, simulated gastric and small intestinal conditions and fermentation in vitro by human intestinal microbiota of polysaccharides from Fuzhuan brick tea. Food Chem. 2018, 244, 331–339. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.10.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith F.; Pan X.; Bellido V.; Toole G. A.; Gates F. K.; Wickham M. S.; Shewry P. R.; Bakalis S.; Padfield P.; Mills E. N. Digestibility of gluten proteins is reduced by baking and enhanced by starch digestion. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015, 59, 2034–2043. 10.1002/mnfr.201500262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G.; Wang M.; Li Y.; Xu R.; Li X. Comprehensive analysis of 61 characteristic constituents from Siraitiae fructus using ultrahigh-pressure liquid chromatography with time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2016, 125, 1–14. 10.1016/j.jpba.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Q.; Xie Y.; Wang W.; Yan Y.; Ye H.; Jabbar S.; Zeng X. Extraction optimization, characterization and antioxidant activity in vitro of polysaccharides from mulberry (Morus alba L.) leaves. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 128, 52–62. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Y.; Wang C. Y.; Wang S. T.; Li Y. Q.; Mo H. Z.; He J. X. Physicochemical properties and antioxidant activities of tree peony (Paeonia suffruticosa Andr.) seed protein hydrolysates obtained with different proteases. Food Chem. 2021, 345, 128765 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.